1. Introduction

Initial reports about audiovestibular symptoms in patients with Chiari I malformation (CMI) date back to 1971 when Rydell and Pulec [

1] decribed a series of 29 patients presenting otoneurological symptoms in a population of 130 subjects with CMI explored at the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minn.). The most frequent symptoms were hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo and imbalance. Imbalance was reported as the chief clinical complain in 30% of adult CMI patients in another paper published soon after by the same group [

2]. Since that time otolaryngologists have maintained their interest in exploring audiovestibular involvement in CMI, stressing the importance of this relationship.

Chiari I malformation (CM1) is a structural abnormality characterized by cerebellar tonsillar descent of at least 5 mm below the level of the foramen magnum[

3] or of Mc Rae’s line, into the vertebral canal. Once classified as rare disease, it is increasingly diagnosed due to the improvements in cerebral imaging. Although the true prevalence in the general population is difficult to establish, the imaging incidence in children younger than 18 years has been reported from 0.4 to 3.6% [

4,

5].

Symptoms related to CMI have been classically divided in four categories [

2,

3,

6,

7]:

1) exertional nuchal pain and headaches;

2) symptoms related to brainstem and lower cranial nerve dysfunction;

3) symptoms related to syringomyelia, occurring in 45-75% of CMI patients[

2,

8];

4) cerebellar symptoms. A clinical differences between adults and children is the increased occurrence in children of central sleep apnea syndrome (CSAS). Feeding problems and oropharyngeal symptoms are also more frequent in children under 3 years of age[

4]. Traditionally, the decision about surgical management of CMI being necessary was made by the presence of syrinx, central apnea syndrome, or symptoms believed to be characteristic for CMI, such as exertion headache, exertional neck pain, pyramidal signs and tetraparesis.

Although from an anatomical point of view it is possible that audiovestibular disorders might be arising from in a crowded posterior cranial fossa, where the brainstem, the flocculonodular lobe of the cerebellum and cranial nerves may be compressed or distorted, rarely are these symptoms alone sufficient to justify surgical intervention. It is the presence of nystagmus, particularly downbeat nystagmus (DBN), which has largely been associated with CMI [

1,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Although many neurosurgeons accept DBN as a presenting symptom of CMI[

6,

7], ENT evaluation is not systematically required prior to occipito-cervical decompression, and surgical intervention does not rely on it. In the literature, there is no consensus about precise anatomical substrate of audiovestibular signs and symptoms seen in CMI patients, as these symptoms are classified as cerebellar in some studies[

6,

15], or as originating from brainstem compression or lower cranial nerves in others[

3,

7]. Recognition of the relationship between audiovestibular symptoms or signs and CMI become fundamental in the process of selection of surgical candidates in patients who do not have other criteria for intervention (i.e., syringomyelia or CSAS) but have atypical headaches or in some cases are defined as “asymptomatic”.

Given the fact that nystagmus has already been largely described in the literature, we decided to focus our attention on imbalance; another frequently reported, but less studied symptom. The term “imbalance”, also known as disequilibrium or gait ataxia, suggests a lack of movement coordination in movements of voluntary muscles. In the literature, it is often included as part of the general and more widely term “dizziness”, referring to a sense of disorientation in space. “Vertigo” is a more specific term, which is defined as a sensation of rotation of oneself or of surrounding objects, [

23,

24,

25]. There are different types of ataxia that are described[

26], depending on the site of lesion.

Balance disorders in CMI patients manifest with gait ataxia. To assess the real etiology of gait instability in CMI patients it is necessary to perform more precise investigation, as the clinical picture is often poor, and might not provide answers. One of the most quantitative and reliable methods of assessing postural control is dynamic posturography[

27]. At our institution, Computerized Dynamic Posturography (Equitest

®, NeuroCom, Clackamas, OR) (CDP) at the Laboratory for the Analysis of Posture, Equilibrium and Motor Function (LAPEM), can be performed after ENT examination.

The aims of the study were

- ▪

to define the presence of imbalance in children with diagnosis of CMI;

- ▪

to explore the etiologic mechanisms underlying imbalance in these patients;

- ▪

to determine a correlation between imbalance and surgery; to explore the usefulness of ENT examination and the use of CDP in the surgical management of CMI children.

Details of our study’s protocol have been already published [

28], and will be summarized in this manuscript.

To the best of our knowledge, there are only few studies in the literature describing balance control patterns in CMI patients [

29,

30] and this is the first study about balance control analysis in a paediatric CMI cohort using Equitest

® (Computerized Dynamic Posturography, or CDP).

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Patients

Between September 2019 and September 2023, 48 children with a diagnosis of CMI were seen at our institution. Radiologic criteria for diagnosis of CMI was the presence of a caudal displacement of cerebellar tonsils of at least 5 mm under McRae’s line[

3]. Inclusion criteria for the study were the following: children aged from 6 to 18 years with radiologically confirmed CMI, presenting clinical features suggesting ENT involvement (dizziness, nystagmus, gait impairment, motion sickness, malaise and atypical migraine which could not be directly attributed to the CMI).

Patients with tonsillar ectopia secondary to other complex pathology (e.g., craniostenosis, craniocervical malformation, intracranial hypertension, posterior fossa tumour) were not included in the study, as tonsillar ectopia in these cases might not fall into the diagnosis of CMI. Children with pre-existing vestibular pathology, children unable to stand on the platform (due to cerebral palsy, severe behavioural troubles, severe visual impairment, or associated orthopedic pathologies) and children and/or parents who refused to participate in the study were also excluded. In our population of 48 patients,

- ▪

8 patients were excluded from the study because they did not meet the inclusion criteria,

- ▪

2 patients were less than 6 years of age,

- ▪

1 patient had severe visual impairment,

- ▪

2 patients had cognitive impairment,

- ▪

2 patients were operated for craniocervical decompression for cerebellar ptosis secondary to craniostenosis,

- ▪

1 patient had already been operated on in the past for Chiari I malformation

- ▪

5 patients refused to be enrolled

The 35 remaining patients, who all agreed to be included in the study, were allocated into two groups, independent of the ongoing results of the study. The first group included 21 patients for whom there was no indication for surgery, and the second one was a group of 14 patients who would have benefited from surgical intervention. The criteria which lead the neurosurgeon to decide on surgical intervention are represented by the presence of at least one of the following aspects: characteristic symptomatology (most of all, exertional headaches, usually occipito-cervical, but also of frontal location; presence of symptoms of brainstem compression); syringomyelia, central sleep apnea syndrome. One operated girl missed her definitive postoperative posturographic assessment, in two cases results could not be analyzed and, at the time of this paper, data are not available for 4 children yet. In total, data is available for 28 patients, 18 non-operated and 10 operated ones.

2.2. Methods

All patients benefited from a complete clinical evaluation and in-depth history taking, recorded in a survey, a medullary MRI, to check for syringomyelia, and a polysomnographic recording, to look for sleep apnea syndrome.

The patients enrolled in the study were all referred for ENT assessment, including neuro-otological examination and CDP by Equitest®. This evaluation was conducted in a blind fashion, as the ENT specialist (PhP) did not know whether or not patients were surgical candidates.

The ENT assessment consisted of a neuro-otological examination and clinical vestibular assessment, if deemed necessary. The aims of the neuro-otological examination were to detect and differentiate cerebellar from vestibular signs, identify segmental or axial deviations, and rule out confounding associated factors. Other evaluated factors included vergence insufficiency, refraction disorders, or other visual correction. Vertigo or dizziness were accurately assessed, as well as complaints of tinnitus. Otoscopic examination was also carried out, with tympanometry and acoustic reflex test recordings (Interacoustics, Middelfart, Denmark) and determining hearing thresholds (pure-tone air and bone-conduction thresholds) in tone audiometry (from 250 Hz to 8000 Hz) and intelligibility in speech tests (Interacoustics).

After that, CDP (Computerized Dynamic Posturography) was carried out to determine balance control performances.

CDP assesses global balance performance and relative weight of sensory information (visual, vestibular, and somatosensory) involved in balance control. The Equitest

® balance system consists of a dual platform with two footplates connected by a pin joint. The footplates are supported by five force transducers. The computer calculates the center of foot pressure (CoP) and the vertical component of the centre of gravity (CoG), using the subject’s height entered by the operator. When a subject stands with ankles centred over the stripe on the dual platform, with feet an equal distance laterally from the centre line, this position is called the “electrical zero position”, and serves as a reference point for the calculation of sway angles. The sensory organization test (SOT) consists of three 20-second trials under six different sensory conditions in which the surface and/or visual surround (i.e., sensory inputs) are systematically manipulated (so-called “sway referencing”)[

27,

31,

32,

33]. (

Table 1).

To protect against falls, patients wear a safety harness connected to the ceiling and an operator stands within reaching distance. The equilibrium score (ES) is calculated by comparing the subject’s anterior-posterior sway during each 20 s SOT trial to the maximal theoretical sway limits of stability, which is based on the individual’s height and size of the base of support. It represents an angle (8.0 anteriorly and 4.5 posteriorly) at which the subject can lean in any direction before the centre of gravity would move beyond a point that allows him/her to remain upright (i.e., point of falling). The following formula is used to calculate the ES:

where Θmax indicates the greatest antero-posterior CoG sway angle, Θmin indicates the lowest antero-posterior CoG sway angle. Lower sways lead to a higher ES, indicating a better balance control performance (a score of 100 represents no sway, while 0 indicates sway that exceeds the limit of stability, resulting in a fall).

Table 2 shows CES and sensory ratios calculation’s method.

The platform is also designed to register medio-lateral sways, i.e., to appreciate body movements in the coronal plane (“lateral deviation”). When the patient shifts the centre of the body medio-laterally from the “zero position”, it is possible to state that the quality of his postural control is not optimal due to a deficit of the ipsilateral vestibular system. Even though is suggested that CDP cannot definitively define site of lesion[

27,

34], in gait ataxia, some authors have attempted at distinguish a cerebellar lesion from a vestibular lesion depending on the posturographic sway pattern [

35,

36,

37], relying primarily on the direction of sway. Maki et al.[

35] reported that lateral deviation is predictive of falls in the elderly population. Given this, we decided to also analyze lateral deviation in our population.

CDP also allows us to analyze the strategy adopted by a patient to maintain postural control. The rapid reflex response which allows the human body to stand up and move with respect to gravity consists of a muscular reaction in the trunk and legs. In response to an event of equilibrium perturbation, integration of the three sensorineural afferences produces an organized trunk and legs’ agonist and antagonist muscles contraction which maintain the stand-up position[

38]. Trunk’s and legs’ muscles enable movement of rigid segments around ankle, knee and hip joints. The most ergonomic muscular schema is selected by healthy human body, and it is preferably driven in an “ascendant direction”, which implicate first activation of ankle contractions, followed by knee’s and hip’s ones. We consider this strategy as “appropriate”, in contrast with “descending strategy”, involving first hip’s jerk than ankle control.

Equitest has been validated as a useful tool to explore balance in children, with a good test-retest reliability[

39]. Six years of age is a cut off that has been already identified [

40] for the reliability of posturographic examination in paediatric population.

2.3. Statistics

Data analysis was presented as the median with 25th and 75th percentiles (median (interquartile range)) for continuous variables, whereas categorical variables as numbers and percentages. Comparisons of baseline characteristics according to the surgery performed were conducted by using Wilcoxon or Kruskal–Wallis tests for continuous variables and the Fisher exact test or χ2 test for categorical variables. Statistical analyses were performed using R, version 4.3.1 (2023-06-16) (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and Jamovi version 2.4 with a critical level for statistical significance was set at 5%. Significance was expressed on figures as follows *= p <0.05; **=p <0.01; ***= p <0.001 ; NS = p >0.05.

3. Results

Twenty-eight children (18 boys and 10 girls) aged 6 to 17 years (mean age 11 y) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were recruited in our study. There were 18 children (5 girls and 13 boys) in Group 1 (non-operated patients) aged between 6 and 17 years. There were 10 children (5 girls and 5 boys) in group 2 (operated patients) aged between 6 and 16 years. No significant differences were found in age (p = 0.904) and sex distribution (p = 0.412).

Table 3 reports epidemiological data of the enrolled patients.

Only one patient in the Group 2 was born prematurely (i.e., before 37 gestational weeks) and none had a serious prenatal history; 16 patients (58%) had associated medical pathology unrelated to their CMI which did not impact posturographic results.

Twenty-two patients (79%) attended regular school. Fifteen children (56%) had history of speech difficulty, necessitating specific therapy; 14 (50%) wore corrective lenses and 5 (18%) had a previous history of strabismus. Only 1 child presented with scoliosis; however, no specific radiologic exam has been systematically realized to check for Cobb’s angles. As shown in

Table 3, no significant difference between the two groups was been found in any of their histories, aside from the ability to ride a bicycle. All the children in the Group 1 were able to ride a bicycle, but 70% of Group 2 patients reported difficulties doing so. This was independent of age (p = 0,04).

Three patients (11%) reported a Chiari I malformation history in relatives; however, we did not explore heredity nor genetic aspects.

In 7 patients (25%) CMI was discovered serendipitously at a CT scan ordered for minor head trauma. In 2 patients (7%) it was discovered after an (7%) at cerebral MRI for developmental delay. In 2 other patients (7%) it was discovered after MRI ordered for episodic faintness. Twelve 12 children (43%) underwent cerebral imaging for recurrent headaches and 2 (7%) for nuchal pain. Two children (7%) were investigated for oculomotor trouble and one (4%) for neurological deficit (sensory motor impairment).

Dizziness and scoliosis were not reported as presenting symptoms or signs in any of our cases; however, one patient with headaches reported vertigo as a main presenting symptom, and two patients (7%) had scoliosis found at initial examination. No patients needed to be treated for scoliosis and none of the aforementioned presenting aspects were found to be significantly different between the two groups (see

Table 4).

All but 5 children complained of headaches, with only one patient describing exertional pain. In 9/28 children (32%), pain was localized to the occipito-cervical region, while all other patients described frontal, fronto-temporal or holocranial pain. All operated children complained of headache, but none described exertional ones. Frequency was mostly weekly, without significant difference for any parameter. Nineteen children (68%) had a family history of migraine.

In Group 2, postoperatively only 3 children were completely relieved of headaches in everyday life, but frequency reduced significantly (p=0.02).

Twelve patients (43%) described having vertigo with different frequencies and characteristics. Interestingly, we found a significant result (p=0.013) comparing the presence of vertigo in operated versus non operated patients (respectively 50% and 6%), with occasional vertigo being more common in operated patients. These aspects are shown in

Table 5.

Evolution of headaches and vertigo in Group 2 patients was evaluated at postoperative follow up; three patients declared a complete resolution of headaches after intervention, with very low p-value (=0.052), even if not significant. It was the number of patients who had “non-nuchal” headaches which better improved, with low p-value as well. Two patients had persisting vertigo at postoperative follow up, compared to 6 before the intervention; even if any of the results is statistically significant, it is interesting to notice that positional vertigo disappeared completely after the operation (

Table 6).

In

Table 7, we reported data concerning degrees of cerebral ptosis and polysomnographic results. At cerebral MRI, 12 patients (42%) had more than a 10 mm cerebellar ptosis, one patient (3,5%) had ventriculomegaly and 3 patients (10,5%) had syringomyelia at diagnosis. Seven group 2 patients (70%) had greater than one centimeter tonsillar ptosis. This difference is significant. However, one can suggest that the greater the ptosis, the greater the possibility of having a CSF circulation problem at the craniocervical junction. The 4 children in the series (15% of total population) presenting with central sleep apnea syndrome were operated on, as respiratory problems related to brainstem compression is an absolute criterion for decompressive surgery. For this reason, comparison between the 2 groups is not useful. Two of them presented a central apnea index superior to 5/h. Fifteen children (56%) presented with obstructive apnea syndrome (OSAS), which is significantly higher than the prevalence in paediatric age previously reported by Rydel et al. (10,3% in a population of 399 infants and adolescent from 2 to 18 years of age)[

41]. However, further consideration about these two topics is beyond the scope of our paper.

All operated children declared headaches, but none had exertional headache. Frequency was mostly weekly, without significant difference for any parameter. Nineteen children (68%) had a family history of migraine.

In group 2, post-operatively only 3 children were completely relieved of headaches in everyday life, but frequency reduced significantly (p=0.02).

Twelve patients (43%) described having vertigo with different frequencies and characteristics. Interestingly, we found a significant result (p=0.013) comparing the presence of vertigo in operated versus non operated patient (respectively 50% and 6%), with occasional vertigo being more common in patients who will be operated. These aspects are shown in

Table 5.

Given the frequent association of audiovestibular symptoms in CMI patients, as discussed above, ENT assessment was carried out in all children.

Clinical evaluation made by the first author, a neurosurgeon (IS) revealed normal neurological status in 13 (72%) group 2 patients, and in 3 (30%) group 2 patients. This difference is significant (p=0.049); however, we found that these results may be related to the fact that symptomatology is one of the criteria for surgical intervention. Two children (10%) in group 2, but none in group 1 presented with disorders of coordination (ataxia in the upper limb). Balance disorders were diagnosed by widening of the support polygon, inferior limb ataxia, a positive Romberg’s test or a history of frequent falls. They were found in 2 group 1 patients (11%) and in 2 (10%) group 2 patients (not significant). Pyramidal signs were slightly less frequent in group 1 (18%) than in group 2 (22%).

Table 8.

neurologic and audiovestibular findings in the enrolled patients. In the group of operated patients, data is lacking for one patient. Neurological examination was carried out by the first author (IS) while ENT assessment was realized by the second author (PhP). A significant difference was found when comparing the two groups with regard to the presence of sensory disorders, and low p-value was shown when comparing the presence of dizziness between the two groups. (Fisher’s exact test).

Table 8.

neurologic and audiovestibular findings in the enrolled patients. In the group of operated patients, data is lacking for one patient. Neurological examination was carried out by the first author (IS) while ENT assessment was realized by the second author (PhP). A significant difference was found when comparing the two groups with regard to the presence of sensory disorders, and low p-value was shown when comparing the presence of dizziness between the two groups. (Fisher’s exact test).

| |

Variable |

Total population (n=28/27) |

Group 1 (n=18/17) |

Group 2 (before operation) (n=10) |

P

value |

| Neurological |

Normal |

16/28 (57 %) |

13/18 (72 %) |

3/10 (30 %) |

0.049 |

| Coordination disorders |

2/28 (7 %) |

0/18 (0 %) |

2/10 (20 %) |

0.12 |

| Balance disorders (ataxia) |

4/28 (14 %) |

2/18 (11 %) |

2/10 (20 %) |

0.60 |

| OTR anomalies |

6/28 (21 %) |

4/18 (22 %) |

2/10 (20 %) |

1.00 |

| Sensitive disorders |

4/28 (14 %) |

0/18 (0 %) |

4/10 (40 %) |

0.010 |

| Oculomotor trouble |

1/28 (4 %) |

0/18 (0 %) |

1/10 (10 %) |

0.36 |

| ENT |

Normal |

12/27 (44 %) |

10/18 (56 %) |

2/9 (22 %) |

0.22 |

| Vestibular deficit |

1/27 (4 %) |

1/18 (6 %) |

0/9 (0 %) |

1.00 |

| Nystagmus |

1/27 (4 %) |

0/18 (0 %) |

1/9 (11 %) |

0.33 |

| Saccadic eye mouvements |

7/27 (26 %) |

3/18 (17 %) |

4/9 (44 %) |

0.18 |

| Dizziness |

4/27 (15 %) |

1/18 (6 %) |

3/9 (33 %) |

0.093 |

| Hearing loss |

7/27 (26 %) |

4/18 (22 %) |

3/9 (33 %) |

0.65 |

| Tinnitus |

3/27 (11 %) |

1/18 (6 %) |

2/9 (22 %) |

0.25 |

From the ENT point of view, 10 patients (56%) in Group 1 and 2 patients in the Group 2 (22%) had normal oto-neurological examination. Data is lacking for one operated patient (n° 9), as shown in

Table 7, which shows neuro-otological findings. Only one patient in Group 1 presented with clinical vestibular disease. Nystagmus was found in only 1 patient (11%) in group 2, while saccadic pursuit was observed in 3 group 1 patients (17%) and 4 group 2 patients (44%). Although not technically significant, a slightly low p-value (0.093) was found comparing the presence of dizziness (33%). In 4 group 1 patients (22%) Subnormal thresholds in pure-tone conventional audiometry were noted in 4 patients in group 1 (22%) and 2 patients in group 2 (33%). These results are not statistically different.

Conventional Equitest

® dynamic posturographic evaluation has been utilized as a complement to ENT investigations. Mean SOT in the whole population was 65.6 (range 65.3 - 76.5); when the 2 groups are separately evaluated, mean SOT in group 1 was 66 (64.0 - 76.0), in the group 2 was 62.3 (66.0 - 77.5), without statistical differences (p=0,655), as shown in

Table 9.

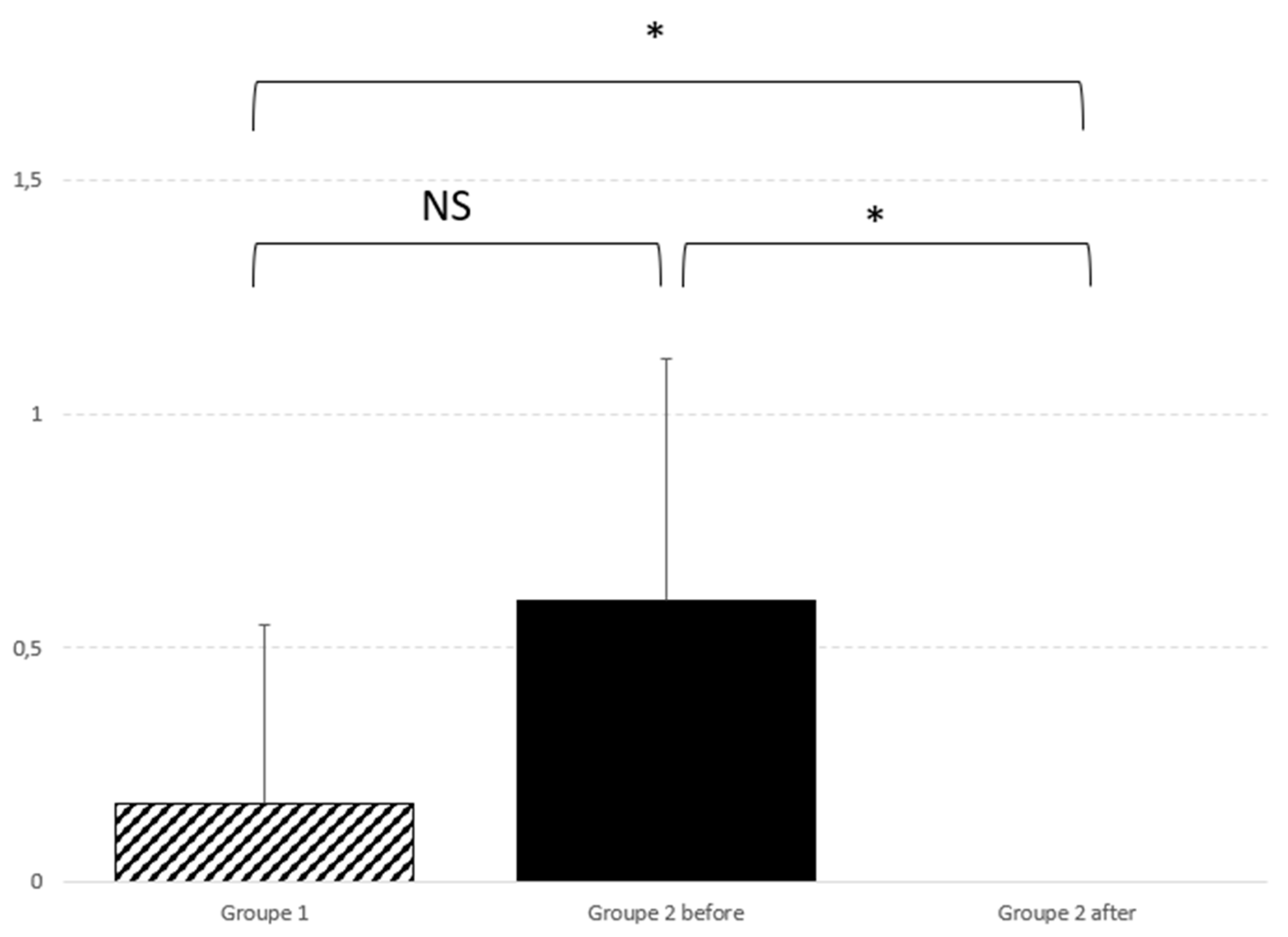

Interestingly, we found significant results comparing lateral deviation attitude during posturography, with 17% of abnormal lateral CoG deviation in group 1, versus 60% in group 2.

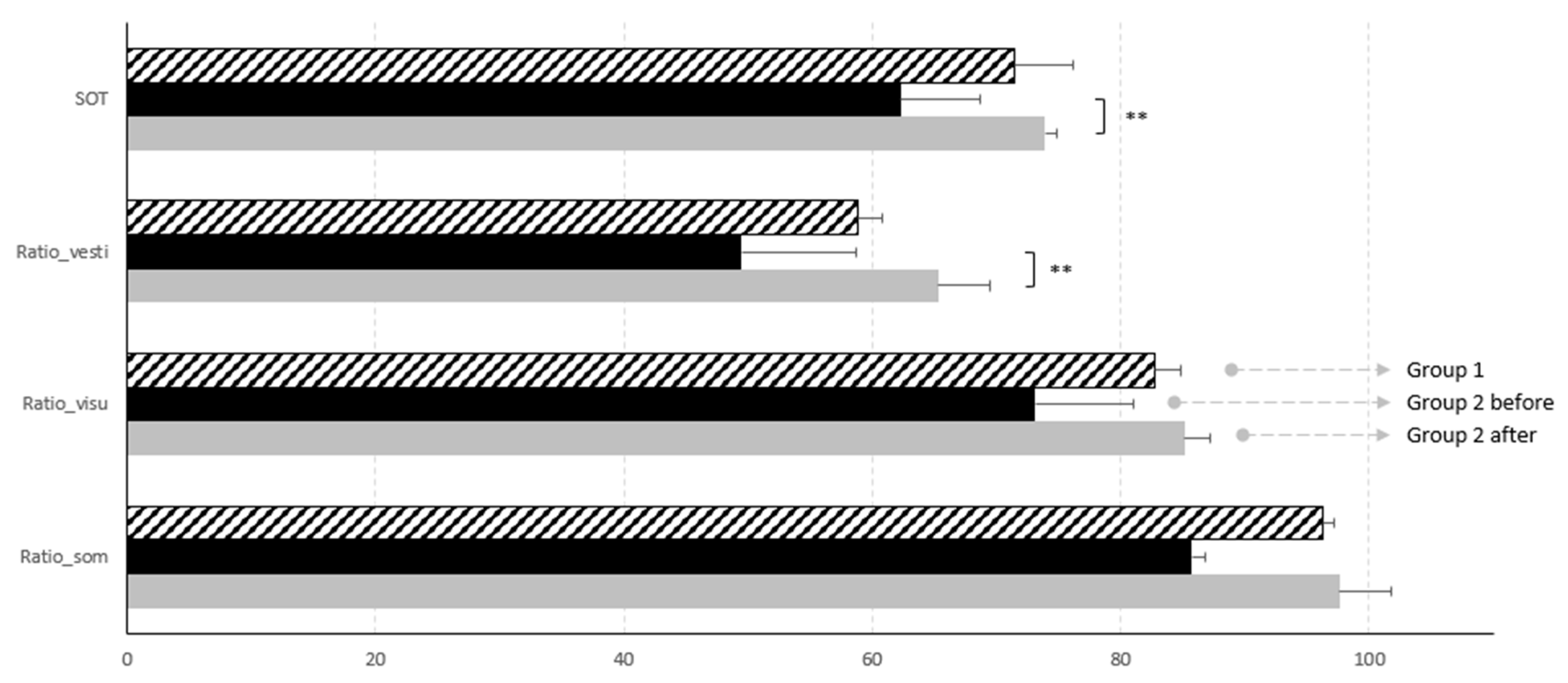

When the same parameters were studied in Group 2, comparing pre and post surgery, a significant difference was seen in the global SOT results (p=0.007). In particular, we found that the sensorineural component of postural control which improved the most was the vestibular one, with a p=0,007 (see

Table 10). Low p-values are found comparing somesthetic and visual ratios.

Graphic representation of such results are reported in

Figure 1.

Also lateral deviation improve significantly after surgery (p=0.01), as graphically reported in

Figure 2.

Lateral deviation also improved significantly after surgery (p=0.01), as illustrated in

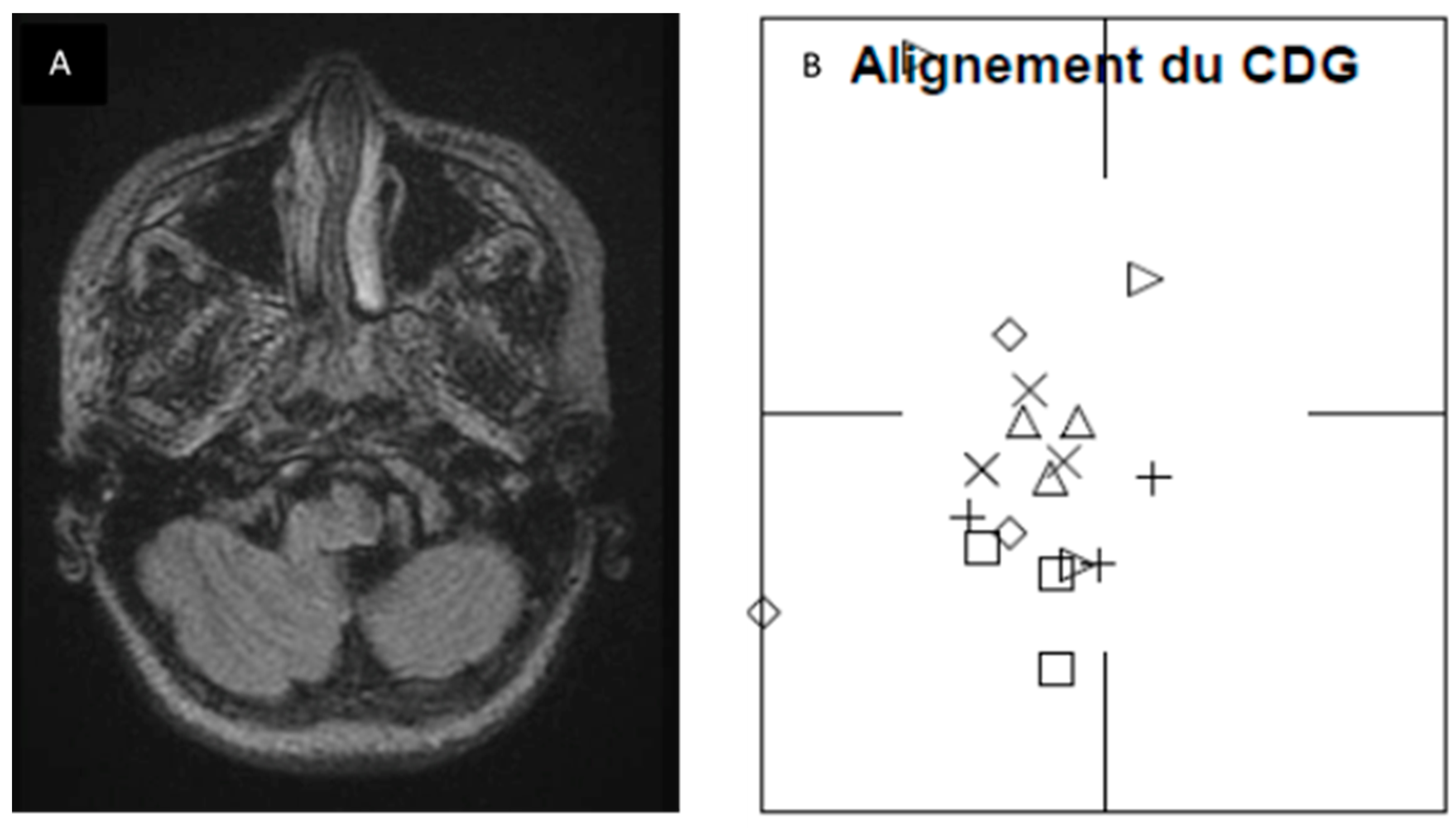

Figure 2. In order to further our knowledge about this finding, we retrospectively checked preoperative MRI and surgical reports of operated patients. Although we cannot establish any significant correlation, we found that in 4 patients, there was a perfect correspondence between side of posturography lateralisation, MRI 3D FLAIR signal tonsillar anomaly and side of tonsillectomy (which normally corresponds to the greater descending tonsil on MRI).

Figure 3 shows pre and postoperative results of one of the patients Two other patients, who presented little MRI FLAIR bilateral tonsillar anomaly, had a normal CoG without any lateralisation, and one of them benefited from minimal bilateral tonsillar coagulation.

However, the small number of patients included in our series did not allow us to perform statistical analysis for this aspect. We are increasing the number of patients in our study to try and confirm our speculations.

4. Discussion

Results showed a significant improvement of global SOT after intervention (p=0.007), leading us to believe that surgical treatment of Chiari malformation improves postural control in the paediatric population. When the three sensorial afferences determining postural control were independently considered, comparison between pre and post intervention showed low p values for somaesthetic and visual ratios, but a significant difference (p=0.005) for vestibular one. These data suggest that the most impacted system in CMI children is the vestibular system.

Interestingly, we also observed lateral deviation on the preoperative CDP in the Group 2 patients, which significantly differed from Group 1. This lateral deviation reduced significantly after intervention in Group 2 patients, increasing the value of our findings. This finding may be of particular importance, as it suggests that there is a correspondence between the direction of lateral deviation and the side of tonsillar signal anomaly on 3D FLAIR sequences. If such a correspondence can be confirmed, axial 3D FLAIR images and CDP could be included in the standardized workup of CMI patients, as it would be of help in making a surgical decision. Further work is needed to corroborate this finding, as our numbers are too low to show significance.

From a neurosurgical point of view, it is fundamental to know what might be related to CMI, in order to assure the best care for our patients. In CMI patients who manifest signs or symptoms clearly related to the malformation (i.e., central sleep apnoea syndrome, syryngomyelia, effort headaches and tetra paresis), the need for surgical treatment is rapidly established. However vestibular assessment may become an essential assessment in a category of CMI patients called “asymptomatic” or “oligo symptomatic”, because of the absence of typical CMI symptoms. Many papers have been published on this subject but the cause and effect relationship between otoneurological signs and symptoms and CMI still remains a source of debate the in neurosurgical community[

42], and this can create controversy regarding surgical management, as these symptoms and signs are not historically directly attributed to the presence of CMI [

43], and do not provide sufficient information for the neurosurgeon to make a decision about for surgical intervention. However, in a recent special journal issue, these ENT symptoms have been reported as possible CMI manifestations, and have been defined as ‘atypical’ symptoms by Novegno et al. [

44]. For this reason, ENT assessment should be required for all CMI patients.

In the literature, we found only two papers [

29,

30] which studied the relationship between CMI and posturographic assessment; however, neither study reported information about lateral sway pattern, which suggests that our study is the first one to look at lateral deviation in children with CMI.

Famili [

29] studied Equitest

® results in a cohort of 24 CMI adults (21/24 females, aged from 20 to 61 years) who complained about dizziness symptoms. The data suggested a significantly lower use of somatosensory information, but a peripheral vestibular lesion was found in only 8% of patients, suggesting a central origin of dizziness in this population.

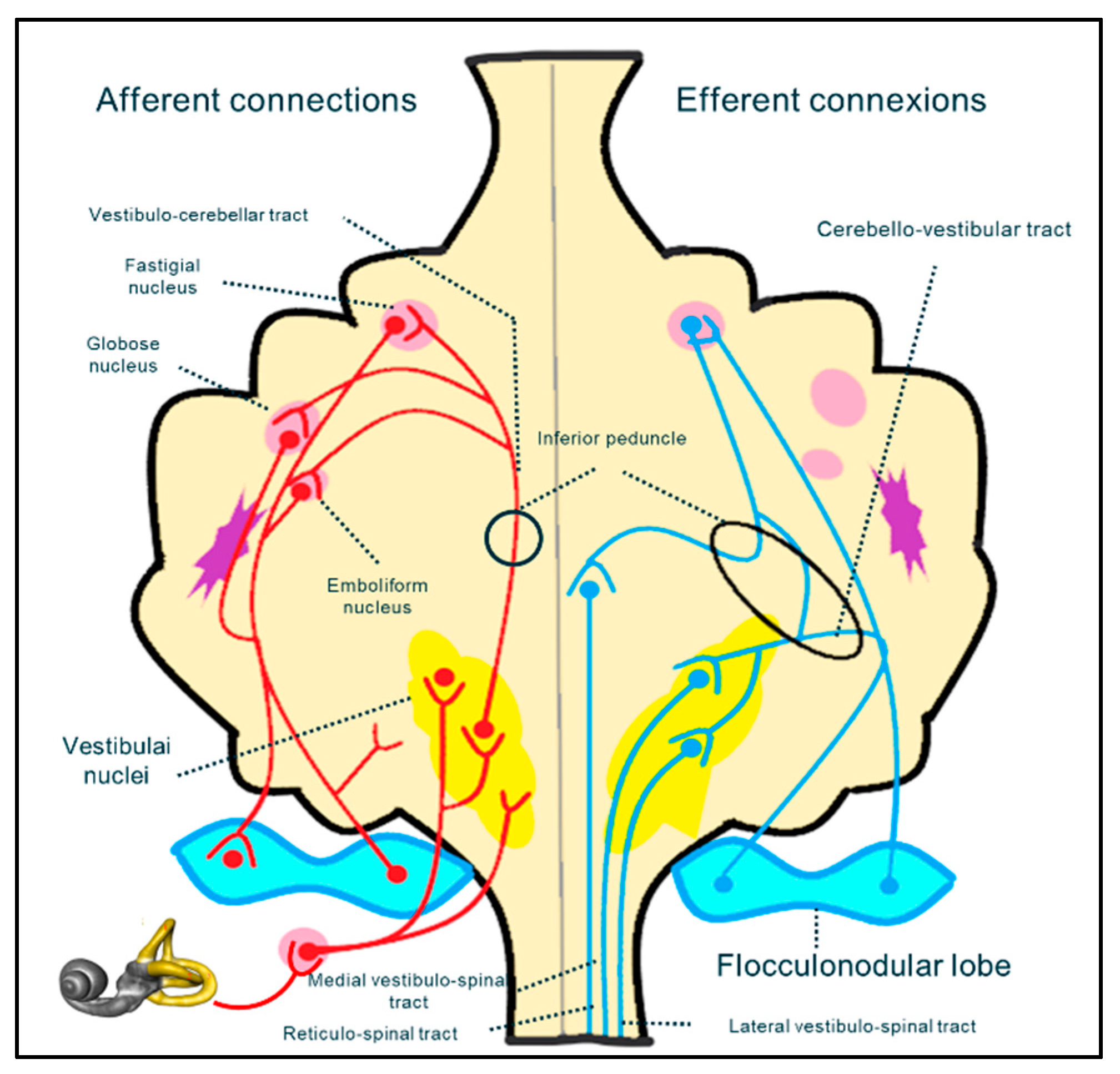

It is difficult to determine (especially in a paediatric population) whether the vestibular impairment in CMI results from damage to afferent fibres of spinocerebellar bundle, from cranial nerve dysfunction (in the central or peripheral portion), or from the cerebellar vestibular nuclei. The vestibular system is a complex neuronal pathway whose central component is situated mostly in the posterior fossa, at the level of the craniocervical junction (

Figure 4). It includes the cerebellar nuclei and cranial nerve nuclei in the brainstem. The peripheral portion of the vestibular system includes the VIIth cranial nerve which leaves the brainstem to reach its destination through the acoustic pore.

Direct compression on the flocculo-nodular lobe, spino-cerebellar and cerebello-vestibular tracts or vestibular nuclei, or again, or distortion of vestibular nerves could produce balance problems and ataxia. in addition, at the same level, olivary nuclei are interlaced in the pretectal flocculo-nodular pathway, which is implicated in the modulation of visual information that is essential for balance control (eg. optokinetic nystagmus and ocular pursuit) [

45].

A hypothesis has been proposed [

9] that a central origin of vestibular impairment in CMI patients is most likely. This is consistent with other reports [

29,

46]. Moncho et al. [

42,

47], showed an abnormal brainstem auditory evoked potential (BAEP) in a cohort of 200 CMI adult patients, mainly at the retrocochlear level, suggesting implication of CMI-related brainstem distortion, (i.e a central origin). A recent study in patients with endolymphatic hydrops (i.e., a peripheral vestibulopathy) showed problems with perilymph-CSF dynamics due to CSF hydrodynamic alterations at the foramen magnum level, and suggested that this may be a possible mechanism of ENT-related symptoms in CMI patients[

20].

In our study, a complete neuro-otological examination accompanied by audiometry and further management, if deemed necessary, was carried out in all children. However, given the limited cooperation of children, we did not include systematic complex instrumental ENT examination, even though that would have helped us delineate brainstem involvement from peripheral vestibular involvement[

17].

In our study, none of the operated children showed clinical vestibular impairment before intervention, thus reinforcing the idea that postoperative vestibular improvement detected on CPD is really linked to cranio-vertebral junction decompression rather than from other confounding factors.

A lack of cooperation is one of the most important limiting factors in a clinical study in children of this age, as it narrows the wide spectrum of available tests for the study of the vestibular system, and this reduces the precision of assessment in such a population. In addition, we feel it is important in this discussion to outline the specificity of the development of vestibular system in the paediatric population. This will also help us come to some conclusions regarding our results.

Sensory inputs utilized by the balance system (somaesthetic, visual and proprioceptive inputs) change progressively during development[

40,

48,

49,

50,

51]. Sinno et al. [

51] recently studied 120 healthy children utilizing Equitest

®, reported SOT normative data throughout childhood and adolescence, and outlined how postural abilities change during development. Compared to adults, younger children utilize more somatosensory inputs; even if the vestibular system is the first system to develop and is morphologically complete at birth, vestibular maturity is reached later, as it entails a higher processing centre of neurosensory inputs utilized for postural control. In addition, balance performance declines not only between the young and the elderly, but also from decade to decade, as demonstrated by the Polish team of Pierchala et al. [

52].

Sensory inputs utilized by the balance system (somaesthetic, visual and proprioceptive inputs) change progressively during development[

40,

48,

49,

50,

51]. Sinno et al. [

51] recently studied 120 healthy children utilizing Equitest

®, reported SOT normative data throughout childhood and adolescence, and outlined how postural abilities change during development. Compared to adults, younger children utilize more somatosensory inputs; even if the vestibular system is the first system to develop and is morphologically complete at birth, vestibular maturity is reached later, as it entails a higher processing centre of neurosensory inputs utilized for postural control. In addition, balance performance declines not only between the young and the elderly, but also from decade to decade, as demonstrated by the Polish team of Pierchala et al. [

52].

The age difference may be one of the reasons of the fact that our results are in contrast with the posturographic results in adults reported by Famili [

29]. In addition that study was characterized by a high prevalence of females (90%), and one might suggest that this gender distribution imbalance might have influenced their results. In our study, gender distribution was equal in group 2, although there was a slight female prevalence (66%) in the overall population. There are few papers directly addressing gender influence on CDP results [

53], but some studies [

48,

49,

50,

54] have also reported this information while focusing primarily on aged-related modifications. It is generally assumed that with increasing age, scores worsen in both males and females in more difficult CDP conditions (conditions 5 and 6) [

55,

56]. In a study conducted by Faraldo-Garcia et al. [

53], females seemed to be better at integrating sensory vestibular information than males, and at dealing with visual conflict.

One may also ask if learning phenomena or age-related bias might influence our results. Given the structure of our study [

28], age-related improvement is not a factor, as posturography was performed 3 to 4 months after surgical intervention, which is not enough time to improve complex sensory integration ability. In addition, SOT improvement cannot be explained by learning phenomena, as the time period between preoperative and postoperative CDP assessment is too long to significantly impact memory.

5. Conclusion

The surgical indication for CMI patients may be obvious when concerning symptoms and signs, such as syringomyelia or sleep apnoea syndrome, are present. However decisions made regarding surgical management may be more controversial when patients are asymptomatic, or when they present with “atypical” symptoms and signs, such as vestibular and postural complaints. Due to the increasing awareness about the existence of these atypical symptoms in CMI, a specific ENT evaluation is highly recommended as part of a preoperative work up. This is particularly important in children, as it is even more difficult to determine the presence of symptoms linked to CMI, and also more difficult to take an accurate history to clarify their signs and symptoms .

Computerized Dynamic Posturography may be a good solution to examine ataxia and postural pattern in children with CMI over 6 years of age, as it is a safe and sensitive measuring tool. However, further studies with a greater number of patients are necessary to better elucidate the role of CDP in the workup of CMI patients.

Ethics and dissemination

Our data treatment was in accordance with the Methodology of reference MR-004 specification for data policy. The protocol has been registered on Clinicaltrials with the following registration number: NCT04679792 (17/12/2020). The study findings will be disseminated via peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations, especially to the Neurosphynx’s rare disease health care network.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: IS, OK and PP; methodology: IS, MC; validation, PP, OK; formal analysis, MC; investigation, IS, PP; resources, IS, OK, AJ; data curation, IS; writing—original draft preparation, IS; writing—review and editing, IS, PP and AM; visualization, OK, AJ, MC and AM; supervision, PP, OK; funding acquisition, IS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript have conceived and designed the study.

Funding

The project won a financial award from Neurosphynx rare diseases healthcare network, who nationally coordinates the Reference Center for Chiari malformation and Rare vertebro-medullary diseases.

Institutional Review Board Statement

this protocol received ethical approval from the Clinical Research Delegation of Nancy University Hospital, in accordance with the National Commission on Informatics and Liberties (Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés) (protocol number 2019PI256-107).

Informed Consent Statement

“Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.”.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on Nancy Regional Hospital Center database, and are only known by the principal investigator due to CNIL privacy policy. .

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Arnaud Wiedeman-Fode (Pediatric Intensive Care Unit – University Hospital of Nancy) for contribution to statistical analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” “The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

References

- Rydell, R.E.; Pulec, J.L. Arnold-Chiari Malformation: Neuro-otologic Symptoms. Arch. Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 1971, 94, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saez, R.J.; Onofrio, B.M.; Yanagihara, T. Experience with Arnold-Chiari malformation, 1960 to 1970. J. Neurosurg. 1976, 45, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- C. Raybaud and G. I. Jallo, ‘Chiari 1 deformity in children: etiopathogenesis and radiologic diagnosis’, Handb. Clin. Neurol., vol. 155, pp. 25–48, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Chatrath, A.; Marino, A.; Taylor, D.; Elsarrag, M.; Soldozy, S.; Jane, J.A. Chiari I malformation in children—the natural history. Child's Nerv. Syst. 2019, 35, 1793–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meadows, J.; Kraut, M.; Guarnieri, M.; Haroun, R.I.; Carson, B.S. Asymptomatic Chiari Type I malformations identified on magnetic resonance imaging. J. Neurosurg. 2000, 92, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciaramitaro, P.; Ferraris, M.; Massaro, F.; Garbossa, D. Clinical diagnosis—part I: what is really caused by Chiari I. Child's Nerv. Syst. 2019, 35, 1673–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbok, P. Clinical features of Chiari I malformations. Child's Nerv. Syst. 2004, 20, 329–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piper, R.J.; Pike, M.; Harrington, R.; A Magdum, S. Chiari malformations: principles of diagnosis and management. BMJ 2019, 365, l1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmmed, A.U.; Mackenzie, I.; Das, V.K.; Chatterjee, S.; Lye, R.H. Audio-vestibular manifestations of Chiari malformation and outcome of surgical decompression: A case report. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1996, 110, 1060–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Awami, A.; Flanders, M.E.; Andermann, F.; Polomeno, R.C. Resolution of periodic alternating nystagmus after decompression for Chiari malformation. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2005, 40, 778–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, F.W.J.; Ingels, K.J.A.O. Otoneurological manifestations in Chiari-I malformation. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1993, 107, 441–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloh, R.W.; Spooner, J.W. Downbeat nystagmus: A type of central vestibular nystagmus. Neurology 1981, 31, 304–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronstein, A.; Miller, D.; Rudge, P.; Kendall, B. Down beating nystagmus: Magnetic resonance imaging and neuro-otological findings. J. Neurol. Sci. 1987, 81, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresty, M.; Barratt, H.; Rudge, P.; Page, N. Analysis of Downbeat Nystagmus. Arch. Neurol. 1986, 43, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, G.G.; Gutiérrez, M.; de Lucas, E.M.; Román, N.V.S.; Laez, R.M.; Angulo, C.M. Manifestaciones audiovestibulares en la malformación de Chiari tipo i. Serie de casos y revisión bibliográfica. Acta Otorrinolaringol. espanola 2015, 66, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korres, S.; Balatsouras, D.G.; Zournas, C.; Economou, C.; Gatsonis, S.D.; Adamopoulos, G. Periodic alternating nystagmus associated with Arnold-Chiari malformation. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2001, 115, 1001–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longridge, N.S.; Mallinson, A.I. Arnold-chiari malformation and the otolaryngologist: Place of magnetic resonance imaging and electronystagmography. Laryngoscope 1985, 95, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossman, S.S.; Bronstein, A.M.; Gresty, M.A.; Kendall, B.; Rudge, P. Convergence Nystagmus Associated With Arnold-Chiari Malformation. Arch. Neurol. 1990, 47, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieh, C.; Gottlob, I. Arnold-Chiari malformation and nystagmus of skew. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2000, 69, 124–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, N.M.; Franco, R.A.; Milhorat, T.H. Otologic Manifestations of Chiari I Malformation. Otol. Neurotol. 2001, 22, 678–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spooner, J.W.; Baloh, R.W. ‘Arnold-Chiari malformation: improvement in eye movements after surgical treatment. Brain 1981, 104, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, C.F.; Roach, E.S.; Troost, B.T. See-saw Nystagmus Associated With Chiari Malformation. Arch. Neurol. 1986, 43, 299–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muncie, H.L.; Sirmans, S.M.; James, E. Dizziness: Approach to Evaluation and Management. Am. Fam. Physician 2017, 95, 154–162. [Google Scholar]

- E Post, R.; Dickerson, L.M. Dizziness: a diagnostic approach. Am. Fam. Physician 2010, 82, 361–369. [Google Scholar]

- P.P. Perrin, D. Vibert, C. Van Nechel in E. Masson, ‘Étiologie des vertiges’, EM-Consulte. Accessed: May 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.em-consulte.com/article/660116/etiologie-des-vertiges.

- Ashizawa, T.; Xia, G. Ataxia. Contin. Lifelong Learn. Neurol. 2016, 22, 1208–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingma, H.; Gauchard, G.C.; de Waele, C.; van Nechel, C.; Bisdorff, A.; Yelnik, A.; Magnusson, M.; Perrin, P.P. Stocktaking on the development of posturography for clinical use. J. Vestib. Res. 2011, 21, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stella, I.; Remen, T.; Petel, A.; Joud, A.; Klein, O.; Perrin, P. Postural control in Chiari I malformation: protocol for a paediatric prospective, observational cohort – potential role of posturography for surgical indication. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famili, H.P.; Zalewski, C.K.; Ibrahimy, A.; Mack, J.; Cantor, F.; Heiss, J.D.; Brewer, C.C. Audiovestibular Findings in a Cohort of Patients with Chiari Malformation Type I and Dizziness. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palamar, D. Posturographic examination of body balance in patients with Chiari type I malformation and correlation with the presence of syringomyelia and degree of cerebellar ectopia. Turk. J. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2019, 65, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. P. Jacobson, C. W. Newman, and J. M. Kartush, Handbook of Balance Function Testing. Mosby Year Book, 1993.

- Lion, A.; Bosser, G.; Gauchard, G.C.; Djaballah, K.; Mallié, J.-P.; Perrin, P.P. Exercise and dehydration: A possible role of inner ear in balance control disorder. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2010, 20, 1196–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. P. Perrin, ‘Équilibration, proprioception et sport’, Elsevier-Masson, 2013. Accessed: May 16, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://hal.univ-lorraine.fr/hal-01957765.

- Baloh, R.W.; Jacobson, K.M.; Beykirch, K.; Honrubia, V. Static and Dynamic Posturography in Patients With Vestibular and Cerebellar Lesions. Arch. Neurol. 1998, 55, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, B.E.; Holliday, P.J.; Topper, A.K. A Prospective Study of Postural Balance and Risk of Falling in An Ambulatory and Independent Elderly Population. J. Gerontol. 1994, 49, M72–M84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauritz, K.H.; Dichgans, J.; Hufschmidt, A. Quantitative analysis of stance in late cortical cerebellar atrophy of the anterior lobe and other forms of cerebellar ataxia. Brain 1979, 102, 461–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirka, A.; Black, F.O. Clinical Application of Dynamic Posturography for Evaluating Sensory Integration and Vestibular Dysfunction. Neurol. Clin. 1990, 8, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashner, L.M.; McCollum, G. The organization of human postural movements: A formal basis and experimental synthesis. Behav. Brain Sci. 1985, 8, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, B.I, Swaine, and R. Forget, ‘Exploring the comparability of the Sensory Organization Test and the Pediatric Clinical Test of Sensory Interaction for Balance in children’, Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr., vol. 26, no. 1–2, pp. 23–41, 2006.

- Ferber-Viart, C.; Ionescu, E.; Morlet, T.; Froehlich, P.; Dubreuil, C. Balance in healthy individuals assessed with Equitest: Maturation and normative data for children and young adults. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2007, 71, 1041–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redline, S.; Tishler, P.V.; Schluchter, M.; Aylor, J.; Clark, K.; Graham, G. Risk Factors for Sleep-disordered Breathing in Children. Associations with obesity, race, and respiratory problem. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1999, 159, 1527–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moncho, D.; A Poca, M.; Minoves, T.; Ferré, A.; Rahnama, K.; Sahuquillo, J. [Brainstem auditory evoked potentials and somatosensory evoked potentials in Chiari malformation]. Rev. Neurol. 2013, 56, 623–34. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, H.; Tsering, D.; Myseros, J.S.; Magge, S.N.; Oluigbo, C.; Sanchez, C.E.; Keating, R.F. Management of Chiari I malformations: a paradigm in evolution. Child's Nerv. Syst. 2019, 35, 1809–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novegno, F. Clinical diagnosis—part II: what is attributed to Chiari I. Child's Nerv. Syst. 2019, 35, 1681–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldschagg, N.; Feil, K.; Ihl, F.; Krafczyk, S.; Kunz, M.; Tonn, J.C.; Strupp, M.; Peraud, A. Decompression in Chiari Malformation: Clinical, Ocular Motor, Cerebellar, and Vestibular Outcome. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 292–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.D.; E Harbaugh, R.; Lenz, S.B. Surgical decompression of Chiari I malformation for isolated progressive sensorineural hearing loss. Am. J. Otol. 1994, 15, 634–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moncho, D.; Poca, M.A.; Minoves, T.; Ferré, A.; Cañas, V.; Sahuquillo, J. Are evoked potentials clinically useful in the study of patients with Chiari malformation Type 1? J. Neurosurg. 2017, 126, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirabayashi, S.-I.; Iwasaki, Y. Developmental perspective of sensory organization on postural control. Brain Dev. 1995, 17, 111–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matheson, A.J.; Darlington, C.L.; Smith, P.F. Further evidence for age-related deficits in human postural function. J. Vestib. Res. 1999, 9, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, M.O.; Magro, J.B.; González, J.D.; González, G.D.; Gaona, J.R.; Pastor, J.B. Control postural según la edad en pacientes con vértigo posicional paroxístico benigno. Acta Otorrinolaringol. espanola 2005, 56, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinno, S.; Dumas, G.; Mallinson, A.; Najem, F.; Abouchacra, K.S.; Nashner, L.; Perrin, P. Changes in the Sensory Weighting Strategies in Balance Control Throughout Maturation in Children. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 2020, 32, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierchała, K.; Lachowska, M.; Morawski, K.; Niemczyk, K. [Sensory Organization Test outcomes in young, older and elderly healthy individuals--preliminary results]. Otolaryngol. Polska 2012, 66, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraldo-García, A.; Santos-Pérez, S.; Labella-Caballero, T.; Soto-Varela, A. Influence of Gender on the Sensory Organisation Test and the Limits of Stability in Healthy Subjects. Acta Otorrinolaringol. (English Ed. 2011, 62, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, P.; Deviterne, D.; Hugel, F.; Perrot, C. Judo, better than dance, develops sensorimotor adaptabilities involved in balance control. Gait Posture 2002, 15, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baydal-Bertomeu, J.; I Guillem, R.B.; Soler-Gracia, C.; De Moya, M.P.; Prat, J.; De Guzmán, R.B. Determinación de los patrones de comportamiento postural en población sana española. Acta Otorrinolaringol. espanola 2004, 55, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Rama-López and N. Perez-Fernandez, ‘Sensory interaction in posturograhy’, Acta Otorrinolaringológica Esp., vol. 55, pp. 62–6, Mar. 2004.

Figure 1.

graphic representation of posturographic results. Global SOT and vestibular ratio improve significantly after surgery.

Figure 1.

graphic representation of posturographic results. Global SOT and vestibular ratio improve significantly after surgery.

Figure 2.

graphic representation of lateral deviation comparison and significant postoperative difference. Comparison between the two groups did not find any significant difference; p=0.35. On the contrary, real improvement is noticed between before and after the intervention; p=0.011.

Figure 2.

graphic representation of lateral deviation comparison and significant postoperative difference. Comparison between the two groups did not find any significant difference; p=0.35. On the contrary, real improvement is noticed between before and after the intervention; p=0.011.

Figure 3.

Correspondence between FLAIR MRI tonsillar signal anomaly and lateral deviation on posturography was found in four patients of Group 2. A) FLAIR axial images at craniovertebral junction of patient number 26, showing sufferance signal of left tonsil, going toward the median line. B) Posturographic results showed a deviation of CoG toward the left side. (Alignement du CDG: Center of gravity alignement; CoG: Center of Gravity).

Figure 3.

Correspondence between FLAIR MRI tonsillar signal anomaly and lateral deviation on posturography was found in four patients of Group 2. A) FLAIR axial images at craniovertebral junction of patient number 26, showing sufferance signal of left tonsil, going toward the median line. B) Posturographic results showed a deviation of CoG toward the left side. (Alignement du CDG: Center of gravity alignement; CoG: Center of Gravity).

Figure 4.

schematic reconstruction of neural pathway implicated in the sensory neural integration for postural control.

Figure 4.

schematic reconstruction of neural pathway implicated in the sensory neural integration for postural control.

Table 1.

Computerized dynamic posturography. Sensory organization test (Equitest

®, NeuroCom, Clackamas, OR). Determination of the six conditions. SR, sway-referenced[

27,

31,

32], [

33].

Table 1.

Computerized dynamic posturography. Sensory organization test (Equitest

®, NeuroCom, Clackamas, OR). Determination of the six conditions. SR, sway-referenced[

27,

31,

32], [

33].

| Postural control test |

|---|

| Name |

Situation |

Sensory consequences |

| Condition 1 |

Fixed support, eyes open |

- |

| Condition 2 |

Fixed support, eyes closed |

Vision absent |

| Condition 3 |

Fixed support, SR surround |

Altered vision |

| Condition 4 |

SR support, eyes open |

Altered proprioception |

| Condition 5 |

SR support, eyes closed |

Vision absent, altered proprioception |

| Condition 6 |

SR support, SR surround |

Altered vision and proprioception |

Table 2.

Computerized dynamic posturography. Sensory organization test (Equitest®, NeuroCom, Clackamas, OR). Significance of composite score and sensory ratios.

Table 2.

Computerized dynamic posturography. Sensory organization test (Equitest®, NeuroCom, Clackamas, OR). Significance of composite score and sensory ratios.

| Name |

Equation |

Significance |

| Composite score |

[C1 + C2 + 3 (C3 + C4 + C5 + C6)] / 14 |

Evaluate global balance performance. A low score represents poor postural control |

| Somatosensory ratio |

C2 / C1 |

Ability to use somatosensory input to maintain balance (even when visual cues are removed).

A low score suggests poor use of somatosensory references |

| Visual ratio |

C4 / C1 |

Ability to use visual input to maintain balance (even when somatosensory cues are altered). A low score suggests poor use of visual references |

| Vestibular ratio |

C5 / C1 |

Ability to use vestibular input system to maintain balance (even when visual cues are removed and somatosensory cues are altered).

a low score suggests poor use of vestibular cues or that vestibular information is unavailable |

| Visual preference ratio |

C3 + C6 / C2 + C5 |

Degree to which patient relies on visual information to maintain balance (correct/incorrect information).

A low score suggests reliance on visual cues even when they are inaccurate |

Table 3.

Epidemiological and basic medical information of the 18 included patients. In some cases, data lack for one patient. Fisher’s exact test was utilized for statistical analysis for all variables but glasses need (Chi square test). .

Table 3.

Epidemiological and basic medical information of the 18 included patients. In some cases, data lack for one patient. Fisher’s exact test was utilized for statistical analysis for all variables but glasses need (Chi square test). .

| Variable |

Total population (n=28/27) |

Group 1 (n=18/17) |

Group 2 (before operation) (n=10) |

P value |

| Genre male |

18 (64 %) |

13 (72 %) |

5 (50 %) |

0.26 |

| Age |

10.0 (8.0 - 14.0) |

10.0/18 (8.0 - 13.0) |

10.0 (8.0 - 15.0) |

0.90 |

| Normal schoolarship |

22/28 (79 %) |

14 (78 %) |

8/10 (80 %) |

1.00 |

| Chronic non neurologic illness |

6/28 (21 %) |

5 (28 %) |

1/10 (10 %) |

0.37 |

| Non chronic, non neurologic anterior medical history |

4/27 (15 %) |

1/17 (6 %) |

3/10 (30 %) |

0.13 |

| Non chronic, non neurologic anterior surgery |

6/27 (22 %) |

3/17 (18 %) |

3/10 (30 %) |

0.64 |

| Genetic pathology |

2/27 (7 %) |

1/17 (6 %) |

1/10 (10 %) |

1.00 |

| Neurologic pathology |

1/27 (4 %) |

1/17 (6 %) |

0/10 (0 %) |

1.00 |

| ENT non vestibular pathology |

1 (4 %) |

1/17 (6 %) |

0/10 (0 %) |

1.00 |

| Ortopaedic pathology |

1 (4 %) |

1/17 (6 %) |

0/10 (0 %) |

1.00 |

| Respiratory pathology |

2 (7 %) |

2/17 (11 %) |

0/10 (0 %) |

0.52 |

| Strabismus |

5 (18 %) |

3/17 (17 %) |

2/10 (20 %) |

1.00 |

| Speech difficulties/Speech therapy |

15/27 (56 %) |

8/17 (47 %) |

7/10 (70 %) |

0.42 |

| Glasses |

14/27 (50 %) |

8/17 (44 %) |

6/10 (60 %) |

0.43 |

| Bicycle driving difficulties |

24/28 (89 %) |

18/18 (100 %) |

7/10 (70 %) |

0.041 |

Table 4.

Presenting symptoms of enrolled patients, leading to cerebral imaging. The first presenting symptom was headache, but the second most important way to diagnosis was accidental finding. (Fisher’s exact test).

Table 4.

Presenting symptoms of enrolled patients, leading to cerebral imaging. The first presenting symptom was headache, but the second most important way to diagnosis was accidental finding. (Fisher’s exact test).

| Presenting symptom |

Total population (n=28) |

Group 1

(n=18) |

Group 2

(before operation) (n=10) |

P

value |

| Headaches |

12 (43 %) |

6 (33 %) |

6 (60 %) |

0.24 |

| Accidental |

7 (25 %) |

4 (22 %) |

3 (30 %) |

0.67 |

| Developmental delay |

2 (7 %) |

2 (11 %) |

0 (0 %) |

0.52 |

| Malaise |

2 (7 %) |

2 (11 %) |

0 (0 %) |

0.52 |

| Nuchal pain |

2 (7 %) |

1 (6 %) |

1 (10 %) |

1.00 |

| Oculomotor deficit |

2 (7 %) |

2 (11 %) |

0 (0 %) |

0.52 |

| Sensory-motor deficit |

1 (4 %) |

1 (6 %) |

0 (0 %) |

1.00 |

Table 5.

headaches and vertigo characteristics in the enrolled patients. Results based on patient’s survey. Globally, headaches are declared by 82% of the enrolled patients, and in all operated children. None but one Group 1 patient declared exertional headaches. No significant differences were found between the two groups. Concerning vertigo, prevalence in the total population was 43%, 60% in the Group 2. Significant difference is noted in vertigo frequency (Fisher’s exact test).

Table 5.

headaches and vertigo characteristics in the enrolled patients. Results based on patient’s survey. Globally, headaches are declared by 82% of the enrolled patients, and in all operated children. None but one Group 1 patient declared exertional headaches. No significant differences were found between the two groups. Concerning vertigo, prevalence in the total population was 43%, 60% in the Group 2. Significant difference is noted in vertigo frequency (Fisher’s exact test).

| Headaches and vertigo |

Total population |

Not operated |

Operated |

P value |

| Headaches |

Global |

23/28 (82%) |

13/18 (72%) |

10/10 (100%) |

0.128 |

| Occipital headaches |

9/28 (32 %) |

5/18 (28 %) |

4/10 (40 %) |

0.68 |

| Non occipital headaches |

14/28 (50 %) |

9/18 (6 %) |

6/10 (60 %) |

1.00 |

| Exertional headaches |

1/28 (4 %) |

1/18 (6 %) |

0/10 (0 %) |

1.00 |

| Weekly headaches |

17/28 (61 %) |

10/18 (56 %) |

7/10 (70 %) |

0.69 |

| Monthly headaches |

6/28 (21 %) |

3/18 (17 %) |

3/10 (30 %) |

0.63 |

| Drugs resolving headaches |

12/27 (44 %) |

6/17 (35 %) |

6/10 (60 %) |

0.26 |

| Rest and dark resolving headaches |

4/27 (15 %) |

2/17 (12 %) |

2/10 (20 %) |

0.61 |

| |

Family migraine |

19/28 (68 %) |

12/18 (67 %) |

7/10 (70 %) |

1.00 |

| Associated vomiting |

6/27 (22 %) |

3/17 (18 %) |

3/10 (30 %) |

0.64 |

| Vertigo |

Global |

12/28 (43 %) |

6/18 (33 %) |

6/10 (60 %) |

0.24 |

| Weekly vertigo |

6/28 (21 %) |

5/18 (28 %) |

1/10 (10 %) |

0.37 |

| Monthly vertigo |

6/28 (21 %) |

1/18 (6 %) |

5/10 (50 %) |

0.013 |

| Positional vertigo |

7/28 (25 %) |

4/18 (22 %) |

3/10 (30 %) |

0.67 |

| Exertional vertigo |

4/28 (14 %) |

1/18 (6 %) |

3/10 (30 %) |

0.12 |

| Vision related vertigo |

1/28 (4 %) |

1/18 (6 %) |

0/10 (0 %) |

1.00 |

| |

Motion sickness |

7/28 (25 %) |

5/18 (28 %) |

2/10 (20 %) |

1.00 |

Table 6.

evolution of headaches and vertigo after the intervention in Group 2 patients. Even if any of the result is significant from a statistical point of view, we found really low p-value comparing pre-operative and postoperative headaches (p=0.052), in particular for non-nuchal pain (p=0.059).

Table 6.

evolution of headaches and vertigo after the intervention in Group 2 patients. Even if any of the result is significant from a statistical point of view, we found really low p-value comparing pre-operative and postoperative headaches (p=0.052), in particular for non-nuchal pain (p=0.059).

| Group 2 |

Before intervention |

After intervention |

P value |

| Headaches |

10/10 (100%) |

7/10 (70%) |

p=0.052 |

| Nuchal |

4/10 (40%) |

1/7 (14%) |

p=0.527 |

| Non nuchal |

6/10 (60%) |

6/7 (71%) |

p=0.059 |

| Vertigo |

6/10 (60%) |

2/10 (20%) |

P=0.593 |

| Positional |

3/10 (30%) |

0/2 |

p=0.655 |

| Exertional |

3/10 (30%) |

1/2 (50%) |

p=0.317 |

| Brutal |

0/10 |

1/2 (50%) |

p=0.317 |

Table 7.

A) Radiologic details concerning degree of cerebellar ptosis and presence of syringomyelia. B) Polysomnography results. Significant difference is obviously found, because syringomyelia and CSAS are absolute criteria to operate (Fisher’s exact test). In the same manner, the most important is the degree of tonsillar ptosis. A higher degree is related to an increased probability of the patient developing CSF circulation pathology at the craniocervical junction. In Group 1, polysomnographic data is missing for one patient. AHI: Apnoea-Hypopnea index; OAHI: Obstructive Apnea-hypopnea index.

Table 7.

A) Radiologic details concerning degree of cerebellar ptosis and presence of syringomyelia. B) Polysomnography results. Significant difference is obviously found, because syringomyelia and CSAS are absolute criteria to operate (Fisher’s exact test). In the same manner, the most important is the degree of tonsillar ptosis. A higher degree is related to an increased probability of the patient developing CSF circulation pathology at the craniocervical junction. In Group 1, polysomnographic data is missing for one patient. AHI: Apnoea-Hypopnea index; OAHI: Obstructive Apnea-hypopnea index.

| |

Variable |

Total population (n=28/27) |

Group 1 (n=18/17) |

Group 2 (before operation) (n=10) |

P

value |

| A |

Tonsillar ptosis >1 cm

|

12/28 (43 %) |

5/18 (28 %) |

7/10 (70 %) |

0.049 |

| Syringomyelia |

4/28 (14 %) |

0 (0 %) |

4/10 (40 %) |

0.010 |

| B |

Central apnoea syndrom |

4/27 (15 %) |

0/17 (0 %) |

4/10 (40 %) |

0.012 |

| AHI>5/h |

2/27 (7 %) |

0/17 (0 %) |

2/10 (20 %) |

0.13 |

| Obstructive apnoea syndrom |

15/27 (56 %) |

9/17 (53 %) |

6/10 (60 %) |

1.00 |

| OAHI>5 |

2/27 (7 %) |

2/17 (12 %) |

0/10 (0 %) |

0.52 |

Table 9.

posturographic results of Group 1 patients and Group 2 patients, before the intervention. No significant difference is found comparing global SOT and the 3 ratios. On the contrary, lateral CoG deviation is significantly different between the 2 groups. (Wilcoxon-Mann-Withney test; *: Fisher’s exact Test).

Table 9.

posturographic results of Group 1 patients and Group 2 patients, before the intervention. No significant difference is found comparing global SOT and the 3 ratios. On the contrary, lateral CoG deviation is significantly different between the 2 groups. (Wilcoxon-Mann-Withney test; *: Fisher’s exact Test).

| Variable |

Total population (n=28) |

Group 1 (n=18) |

Group 2 (before operation) (n=10) |

P value |

| SOT |

65.6 (65.3 – 76.5) |

66 (64 – 76) |

62,3.0 (66 – 77.5) |

0.655* |

| Somaesthetic Ratio |

97.0 (91.5 - 98.5) |

97.5 (95.0 - 98.0) |

95.0 (68.1 - 99.0) |

0.37* |

| Visual Ratio |

85.5 (74.5 - 91.5) |

86.0 (79.0 - 91.0) |

85.0 (65.3 - 95.0) |

0.98 |

| Vestibular Ratio |

60.0 (40.5 - 69.0) |

61.0 (41.0 - 69.0) |

56.4 (39.0 - 64.0) |

0.41 |

| Lateral deviation |

9 (32 %) |

3 (17 %) |

6 (60%) |

0.35 |

| Inappropriate strategy |

11 (39 %) |

6 (33 %) |

5 (50 %) |

0.44 |

Table 10.

preoperative and postoperative posturographic results in the Group 2 patients. Significant difference is found comparing global SOT and vestibular ratio; interestingly, low p-values are found comparing somaesthétic and visual ones. In the same way, lateral CoG deviation is also significantly different. (Fisher’s exact Test; *: Wilcoxon-Mann-Withney test).

Table 10.

preoperative and postoperative posturographic results in the Group 2 patients. Significant difference is found comparing global SOT and vestibular ratio; interestingly, low p-values are found comparing somaesthétic and visual ones. In the same way, lateral CoG deviation is also significantly different. (Fisher’s exact Test; *: Wilcoxon-Mann-Withney test).

| Group 2 (n° 10) |

Before surgery |

After surgery |

P value |

| SOT |

62.3 (66 – 77.5) |

73.9 (67 – 80.8) |

0.007 |

| Somaesthetic Ratio |

85.7 (73.5 – 98.5) |

97.6 (95.3 – 99.5) |

0.096 |

| Visual Ratio |

73.1 (68.5 – 94.3) |

85.1 (74.8 – 93.5) |

0.084 |

| Vestibular Ratio |

49.5 (42 – 63) |

65.3 (60.5 – 77.5) |

0.005 |

| Lateral deviation |

6/10 (60%) |

0/10 (0%) |

0.011* |

| Inappropriate strategy |

5/10 (50%) |

1/10 (10%) |

0.141* |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).