Introduction

The startle reflex is a fast motor response triggered by a sudden and intense stimulus, probably aiming to protect the animals against injury from a potential hazard. In the acoustic startle response (ASR), the reflex is evoked by an acoustic/vibrational stimulus [

1]. The basic ASR circuit begins when the cochlear hair cells are activated by a loud sound (>80 dB in mammals). The information is transmitted to the cochlear root neurons (CRNs) through the auditory nerve and, once excited, the CRNs sends excitatory inputs to the caudal pontine reticular nucleus (PnC). Activation of PnC leads to the activation of cranial and spinal motoneurons and, finally, to the motor response, eyelid closure and contraction of facial, neck and skeletal muscles in mammals [

2]. ASR is characterized by a very short latency and duration. Abnormal reactivity of ASR has been found in mammalian models of different neuropsychiatric conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), Fragile-X syndrome, or Alzheimer’s disease [

3,

4,

5].

ASR exhibits several forms of behavioral plasticity, including habituation and prepulse inhibition (PPI), and is therefore commonly used to screen the effects of drugs on sensorimotor gating in different animal models [

1,

6,

7,

8]. Habituation is a neuroplastic process, considered as a non-associative form of learning, in which an organism “learns” to filter out irrelevant stimuli [

7]. Short-term habituation to the ASR occurs within a single session using a short interstimulus interval (ISI). In PPI, the magnitude of ASR is reduced when a non-startling stimulus (prepulse) is presented 30-500 ms before the startling stimulus (pulse) [

9]. PPI is used as a quantitative measure of sensorimotor gating [

8]. Both habituation and PPI are considered filtering mechanisms of the central nervous system (CNS) to prevent information overload, allowing selective attention and right processing of the information [

8]. ASR neuroplasticity processes are clinically relevant as they are affected in various neuropsychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, Fragile-X syndrome, obsessive-compulsive disorder [

7,

9,

10,

11], neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s or Huntington’s diseases [

12,

13], as well as after the consumption of some recreational drugs such as MDMA or cocaine [

14,

15].

Zebrafish (

Danio rerio) is a vertebrate experimental model increasingly used in the neurobiology field for several factors, including its high degree of similarity to mammalian models and humans in both the overall organization of the nervous and neurotransmitter systems [

16]. Behavioral repertoire in zebrafish is rich, including anxiety-like behavior, social behavior, learning and different types of memory, to name but a few [

7]. In addition, the genes involved in neurodegenerative diseases are also highly conserved [

16]. Like mammals, zebrafish display a robust ASR in response to acoustic/vibrational stimuli [

17]. Zebrafish ASR is mediated by the Mauthner-cell neuronal circuit, in which Mauthner cells receive sensory inputs from the acoustic-lateralis and vestibular systems [

18]. A single action potential in one of the Mauthner cells is sufficient to trigger the motor networks in the contralateral trunk muscle, simultaneously inhibiting those on the ipsilateral side [

18]. The kinematic analysis of zebrafish ASR has shown that it is characterized by a C-bend of the body, followed by a smaller counter-bend, and then a fast-swimming bout [

17]. Like in mammals, zebrafish ASR also has a very short latency and duration [

19]. Zebrafish ASR is considered a model system to study startle plasticity, including habituation and PPI [

18,

19,

20]. Although ASR is displayed by larval and adult zebrafish [

19], most of the available information is restricted to larvae. Different platforms for assessing ASR kinematics in zebrafish larvae have been developed by research groups studying startle plasticity [

19,

20], and a platform for assessing PPI is commercially available (ZebraBox PPI Hybrid, from ViewPoint; [

21]). These technological tools have allowed the high-content screening of small molecules able to modulate ASR and its plasticity in zebrafish larvae [

20]. However, to our knowledge, no similar platforms have been developed to assess ASR plasticity in adult zebrafish, making it difficult to analyze the long-term effects of developmental exposures to neurotoxic compounds, the study of late-onset neurodegenerative diseases or the effect of the gender on these processes, to give just a few examples.

In this manuscript we have developed a new automated kinematic analysis platform to assess the habituation and PPI of acoustic startle in nine adult zebrafish simultaneously. The main kinematic parameters of the initial C-bend have been characterized using different types of acoustic stimuli. Conditions for habituation and PPI analysis have been standardized, and the reliability of the platform has been tested by using ketamine, a non-competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist. Finally, the effect of the gender on these ASR neuroplasticity processes has been explored.

Material and Methods

Animals and Housing

Adult wild-type zebrafish (standard length: 2.0-3.0 cm) were obtained from Pisciber (Terrassa, Spain) and maintained into a recirculating zebrafish system (Aquaneering Inc., San Diego, United States) at the Research and Development Center zebrafish facilities (CID-CSIC) for 2 months before starting the exposures. Fish were housed in 2.8 L tanks (density: 20 fish/tank) with fish water [reverse-osmosis purified water containing 90 mg/L Instant Ocean® (Aquarium Systems, Sarrebourg, France), 0.58 mM CaSO4 · 2H2O, and 0.59 mM NaHCO3] under a 12L:12D photoperiod. The main parameters of the fish water in the housing facilities were: temperature: 28 ± 1°C; pH: 7.6–8.0; conductivity: 700–800 μS/cm; hardness: 120–130 mg/L. Fish were fed twice a day with flake food (TetraMin, Tetra, Germany).

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the CID-CSIC (OH 1032/2020) and conducted in accordance with the institutional guidelines under a license from the local government (agreement number 11336). Importantly, the ASR analysis and its associated plasticity processes are conducted using non-invasive procedures that do not cause any lasting harm to the animals. Except for the fish exposed to ketamine, all other fish involved in the assays exhibited normal behavior and showed no signs of distress after the completion of the experiments. Therefore, with the sole exception of those fish used for the ketamine tests, which were euthanized after completion of the experiments, all other fish used for this study were returned to the animal facility and used as breeders for future research in accordance with ethical guidelines and institutional policies.

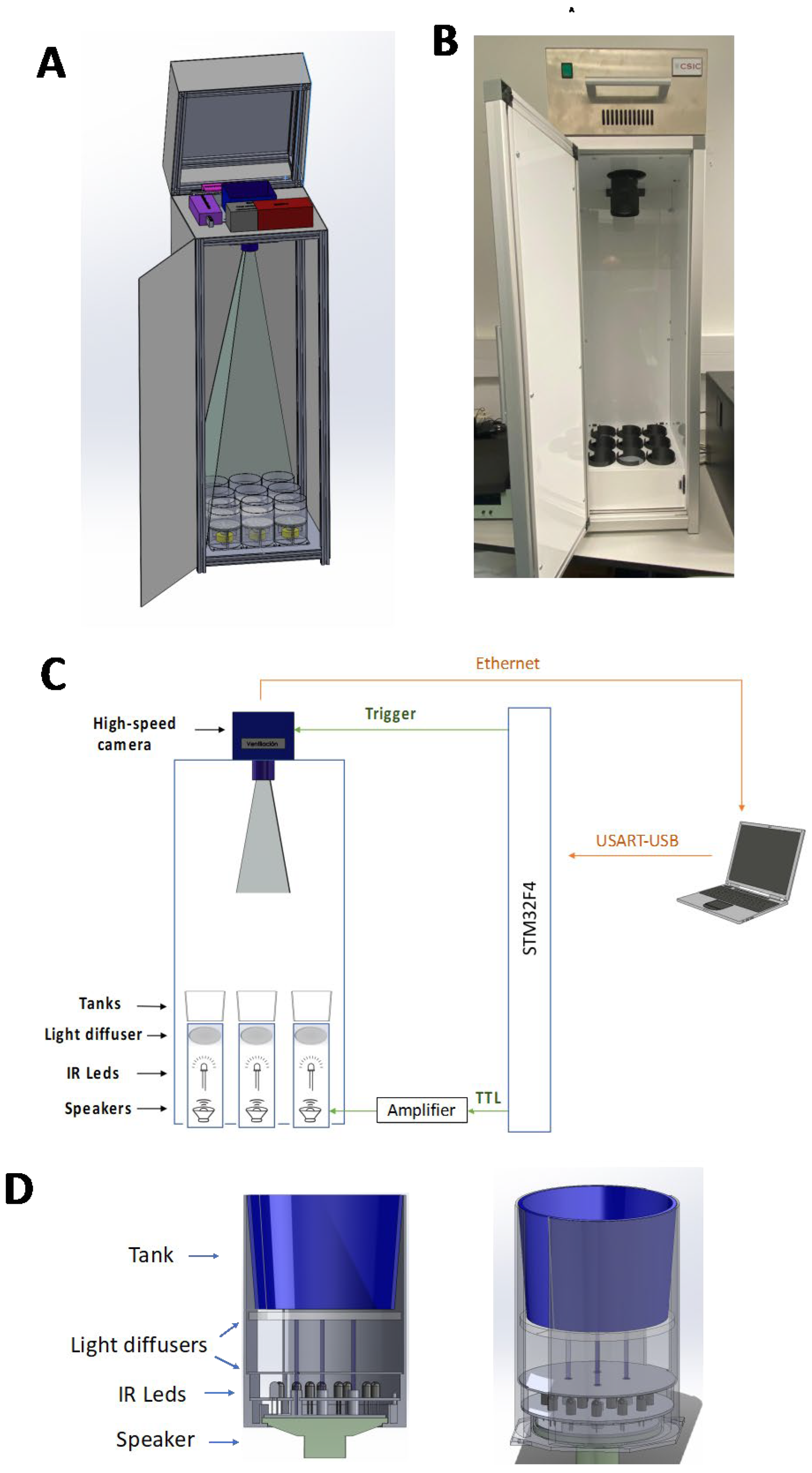

Zebra_K Observation Chamber

The Zebra_K observation chamber (

Figure 1A-B) was designed and built at the Institut of Robòtica i Informàtica Industrial (CSIC-UPC). A schema of the principal components and connections of this device is shown in

Figure 1C. The setup includes nine cylindrical glass tanks (diameter 73 cm, height 60 cm), each holding a single adult zebrafish in 40 mL of fish water. The tanks are organized in a 3x3 grid and they are placed in a closed chamber to isolated them from the vibrations and illumination in the environment. As show in

Figure 1D, each tank is placed on the top of a translucent surface providing infrared illumination using 16 LEDs (OSRAM SFH 4556) regularly distributed in the base of the tank. A speaker of 66 mm of diameter, 4 Ohm and 5W (Amazon, ASIN: B097BHFDSX) is placed under the illumination system of each tank. This speaker is used to generate vibrations that are transmitted to the tank bypassing the illumination system. The sound pressure level (SPL) of the stimuli on the tanks provided by the speakers was determined by a sonometer PCE-322A (PCE Instruments, Meschede, Germany). To capture the reactions of the fish to the vibrations, we installed a high-speed camera (Photron Fastcam Mini UX100) equipped with a 28 mm lens (Sigma 28 mm F1.4 DG HSM Art) on top of the device. When active, the camera takes 1024x1024 pixel images at 1000 frames per second. The camera trigger is activated by a microprocessor (Arm Cortex-M4-based STM32F4) which is also responsible for generating the acoustic stimuli. In this way, a precise synchronization between the stimuli and the captured videos is achieved.

Zebra_K: Software Description

Two software packages are provided to properly operate the device, one to control the experiments and one to analyze the images obtained in each experiment. Both can be run on a standard PC. The ZK Control Software takes care of generating the acoustic stimuli and capturing the images with the potential fish reactions to such stimuli. The main window of this software is shown in

Supplementary Figure S1. This is a highly-flexible software that allows the generation of a wide variety of sequences of acoustic stimuli patterns with arbitrary pauses between them and with an arbitrary number of repetitions for each pattern sequence. Moreover, the intensity and duration of each stimulus can be set individually. The software takes care of translating the configured experiment into low-level commands that are sent to the microcontroller via a USB connection. Finally, this same software is also responsible for downloading the videos captured by the high-speed camera, which is connected to the PC via a gigabit ethernet cable.

The videos captured with the control software are processed with Zebrafish Acoustic Startle Response kinematic analysis software (

Supplementary Figure S2). This software examines the video frame by frame. For each frame, it locates the nine tanks and then, for each tank, it determines the posture of the corresponding fish (

Supplementary Figure S3). To this end, four relevant points on the fish are identified, namely, the head, a point on the upper body, another one on the lower body, and the tail. These four points, robustly identified using a deep neural network trained with DeepLabCut [

22,

23,

24], are used to characterize the posture of the fish using the angles shown in

Supplementary Figure S4. More specifically, the computed angles are the one between the first and second segment (α), the one between the second and third segment (β), and the sum of both (

). The temporal evolution of

gives an accurate account of the reaction of the fish to the stimuli. The microprocessor and the high-speed camera allow the identification of the reactions with an accuracy up to the millisecond. In this way, all fish reactions can be properly detected. To facilitate the data analysis of each experiment, the software generates a comprehensive report with graphs of the analyzed angles, automatically identifying the escape reaction event (

Supplementary Figure S5). Finally, the software summarizes the relevant statistics of the entire experiment, and outputs a report with the parameters in

Supplementary Table S1. These are the data finally used to evaluate the fish responses.

Experimental Procedure

All the experiments with Zebra_K were performed in an isolated behavioral room at 27-28°C, between 10:00 - 17:00 h. Fish were acclimated to the behavior room 1 h before starting the experiments.

To characterize the kinematic endpoints of ASR in adult zebrafish, a strong intensity acoustic/vibrational (AV) stimulus (startle-inducing stimulus) inducing 60-80% startle responses in short-fin wild-type adult zebrafish was used.

The protocol used for short-term habituation studies, based on that described by Wolman et al. [

20] for zebrafish larvae, includes 4 steps. First, during the sensitivity step, adults were exposed to 5 moderate-level AV stimuli, typically eliciting 15-30% of startle responses, delivered with an interstimulus interval (ISI) of 120 s. Then, during the prehabituation step, 5 startle-inducing AV stimuli were delivered with an ISI of 120 s. During the habituation step, 15 startle-inducing AV stimuli were delivered with an ISI of only 1 s. Finally, after 300 s of resting time, the recovery step was characterized by 5 startle-inducing AV stimuli delivered every 120 s. The degree of habituation was calculated as the ratio between the average startle responses during the last 5 stimuli of the habituation step and the 5 stimuli of the prehabituation step [

20].

For PPI analysis, a low-intensity AV stimuli, typically eliciting 0-10% startle responses, was selected as the prepulse stimulus, and the startle-inducing AV stimulus was selected for the pulse. A series of 5 low-intensity AV stimuli (IS: 120 s), then a series of 5 startle-inducing AV stimuli (ISI: 120 s), and finally, a series of 5 sequences “prepulse+pulse” AV stimuli (ISI: 120 s) were delivered. For these sequences, the effect of different times between the prepulse and the pulse, from 1 ms to 2 s, on PPI was tested. The PPI percentage was calculated as described elsewhere [

19]:

Pharmacological Modulation of ASR

Ketamine hydrochloride (K2763; Purity = 100%) was provided by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). To investigate the effect of ketamine on sensitivity, habituation, and PPI, a pretest-posttest control group design [

25] approach was used. This design allows for the comparison of responses within and between control and treated groups before and after ketamine administration. A total of 56 adult fish were used in the pharmacological study. Fish were randomly assigned to either the control group (n=28) or the ketamine-treated group (n=26). Half of the fish in each group were used for habituation experiments (control: n=14, ketamine-treated: n=13), while the remaining half were used for PPI experiments (control: n=14, ketamine-treated: n=13). The standard length of fish in each group is shown in

Supplementary Table S2.

Baseline measurements of ASR sensitivity, habituation, and PPI were obtained in the Zebra_K for all fish. Then, the ketamine-assigned group was transferred to a new tank containing a 50 μM ketamine solution, while the control group was transferred to a new tank with fish water. Post-treatment measurements of ASR, habituation, and PPI were conducted 20 min after exposure. All three endpoints were calculated for each fish both before and after the treatment and the changes observed from pre-test to post-test were analyzed.

Effect of Gender on ASR Plasticity

To assess the effect of the gender on sensitivity and habituation, 24 male and 24 female adult fish were distributed into 6 experimental groups. The standard length of the selected males and females is shown in

Supplementary Table S2. The experiments were conducted in 2 different days, with three trials per day. A similar design was followed to determine the effect of gender on the percentage of PPI.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with IBM SPSS v29 (Statistical Package 2010, Chicago, IL, USA) and plotted with GraphPad Prism 9 for Windows (GraphPad software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

In order to determine if the samples followed a normal distribution, a Shapiro–Wilk test was used. Descriptive statistics were presented as mean ± standard error (SEM) for parametric data, and as median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-parametric data. For normally distributed groups, an unpaired t-test was used to determine statistical significance and one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s as a multiple comparison test. When parametric assumptions could not be made, statistical significance was determined by a Mann–Whitney U test and a Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn–Bonferroni’s test to see if there were any differences between more than two groups. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results and Discussion

Kinematic Parameters of the Acoustic Startle Response in Adult Zebrafish

To systematically determine the kinematic parameters of ASR in adult zebrafish, Zebra_K, an automated kinematic analysis platform able to assess the acoustic startle in adult zebrafish, has been developed. The Zebra_K Observation Chamber (

Figure 1) includes nine cylindrical tanks, organized in a 3x3 grid, and the acoustic stimuli are provided by speakers located under each tank. Illumination is provided by 16 near-infrared leds under each tank, and the fish reactions are recorded at 1000 frames per second (fps) using a high-speed camera located on top of the chamber. The Zebra_K control software allows to determine the number, frequency, duration and intensity of the acoustic stimuli, as well as the interstimuli intervals. Finally, four points on each fish are identified using the Zebrafish ASR kinematic analysis software, a trained deep neural network, and different kinematic parameters are determined, including the latency and the maximum angular velocity, duration and amplitude of the C-bend.

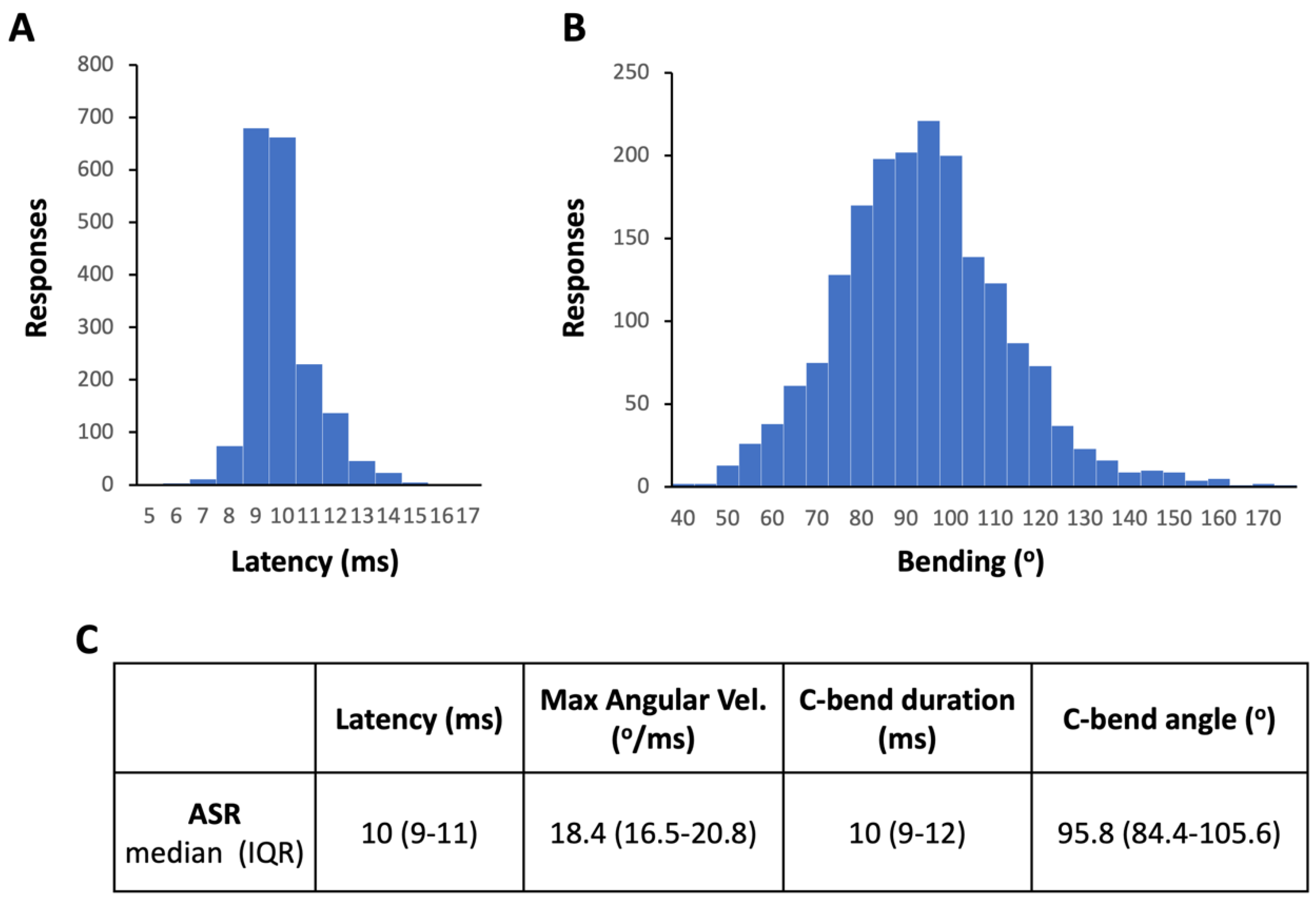

As shown in

Figure 2, kinematic analysis of 1,875 ASRs performed by wild-type short-fin adult zebrafish in response to a startle-inducing stimulus (1000 Hz/ 1 ms/ 103.9 dB re 20 mPa) showed only one wave of responses, characterized by a short latency [median (IQR): 10.0 ms (9-11 ms)] and duration [10.0 ms (9-12 ms)] (

Supplementary Dataset S1). These kinematic values found in the ASR of adult fish are consistent with those previously reported for the short-latency C-bend (SLC) in zebrafish larvae [

19,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. Moreover, in contrast to the ASR reported in larvae [

19], no evidence has been found in this study of long latency C-bend (LLC) in adult zebrafish exposed to startle stimuli. Burgess and Granato [

19] also found an ASR consistent with SLC in adult zebrafish (TLF wild-type line), and furthermore, they found no evidences of LLC in the behavioral repertoire of the adult fish.

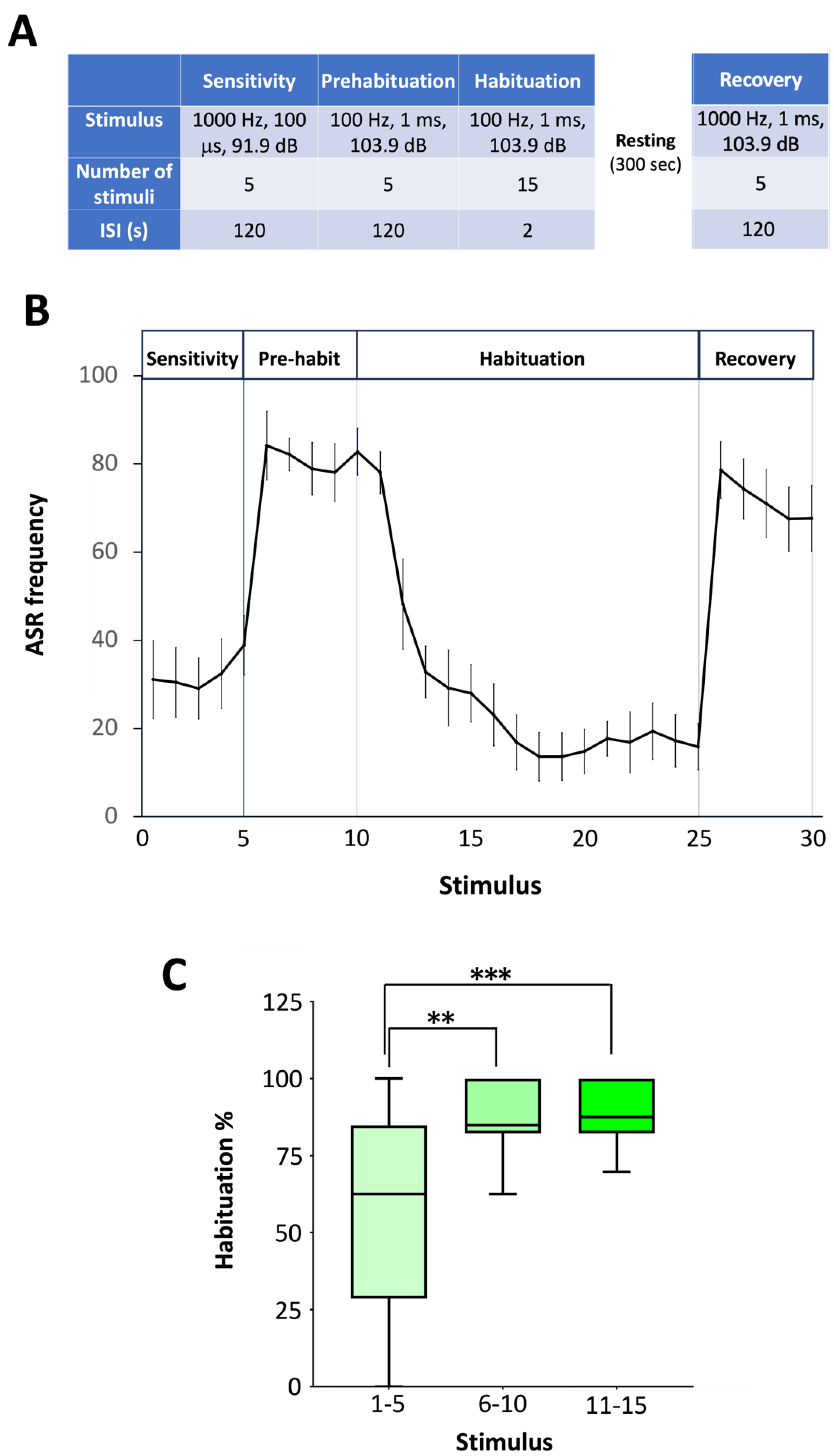

Short-Term Habituation of ASR in Adult Zebrafish

To assess the short-term habituation of ASR, the four-step protocol designed by Wolman et al. [

20] for larvae has been adapted for adult zebrafish (

Figure 3A). Each step is based in delivering a series of stimuli, with moderate or high intensity level depending on the step, separated by specific interstimulus intervals [

20,

26]. For the sensitive step, a moderate level acoustic stimulus (1000 Hz, 100 μs and 91.9 dB re 20 mPa), able to elicit ASR in about 30% of the population, was selected, while a strong startle-inducing stimulus (1000 Hz, 1 ms, 103.9 dB re 20 mPa) able to elicit ASR in about 70% of the animals was selected for the prehabituation, habituation and recovery steps for the habituation protocol in adult zebrafish (

Figure 3A). Series of five stimuli were delivered during the sensitivity, prehabituation, and recovery steps, with interstimulus intervals (ISI) of 120 s. For the habituation step, a series of 15 stimuli was delivered every 2 s.

Figure 3B summarizes results from habituation experiments in a total of 10 groups of adult zebrafish (51 fish in total; results of each experiment can be found in

Supplementary Dataset S2). The proposed protocol provides baselines for the sensitivity to the acoustic stimuli (first step), the highest ASR percentage of the batch (second step), the short-term habituation to a series of startle-inducing stimuli (third step) and, after 5 min of resting time, the recovery of the responses of the adult fish to a series of startle-inducing stimuli (fourth step).

The results of habituation experiments are commonly presented as percentage of responses to the different steps and percentage of habituation. To determine the percentage of habituation in larvae, Wolman et al. [

20] proposed to calculate the ratio between ASR during the last 10 stimuli of the habituation step and the 10 stimuli delivered in the prehabituation step. The percentage of ASR habituation in adult zebrafish was initially calculated as the ratio of the responses during the first (stimuli 1-5), second (stimuli 6-10), or last (stimuli 11-15) 5-stimulus periods of the habituation step to the responses during the 5 stimuli delivered during the prehabituation step (

Figure 3C and

Supplementary Dataset S3). The results show a 62.5 % habituation (IQR: 28.6-84.8%) during the initial 5 stimuli of the series, and then, habituation increases up to 85-88% during the 6-10 or 11-15 stimuli of the series (

Figure 3C). Zebrafish larvae also reach the habituation by the 11

th-15

th stimulus during the habituation period [

20]. Therefore, when a similar criteria is used for determining the short-term ASR habituation in adult and larval zebrafish, similar levels of habituation are reached [

20,

31,

32].

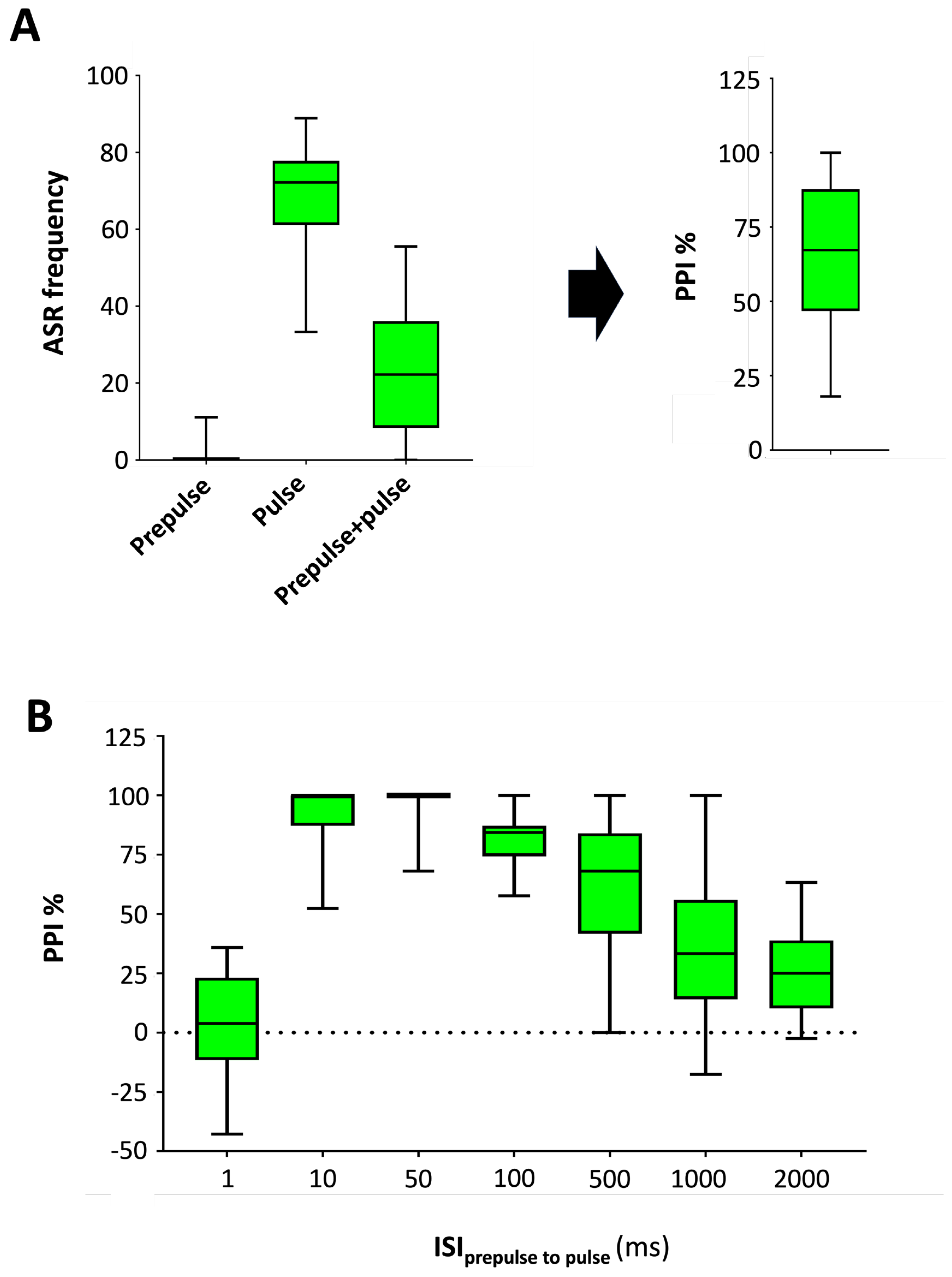

Prepulse Inhibition of ASR in Adult Zebrafish

As other vertebrate models, zebrafish larvae can modulate ASR by sensorimotor gating, and both custom-made [

19,

30,

33,

34] and commercial [

21] systems have been developed for quantitatively determining this neuromodulatory process through the PPI analysis. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are currently no platforms available to assess PPI in adult zebrafish and, as a result, information on sensorimotor gating in adults remains quite limited [

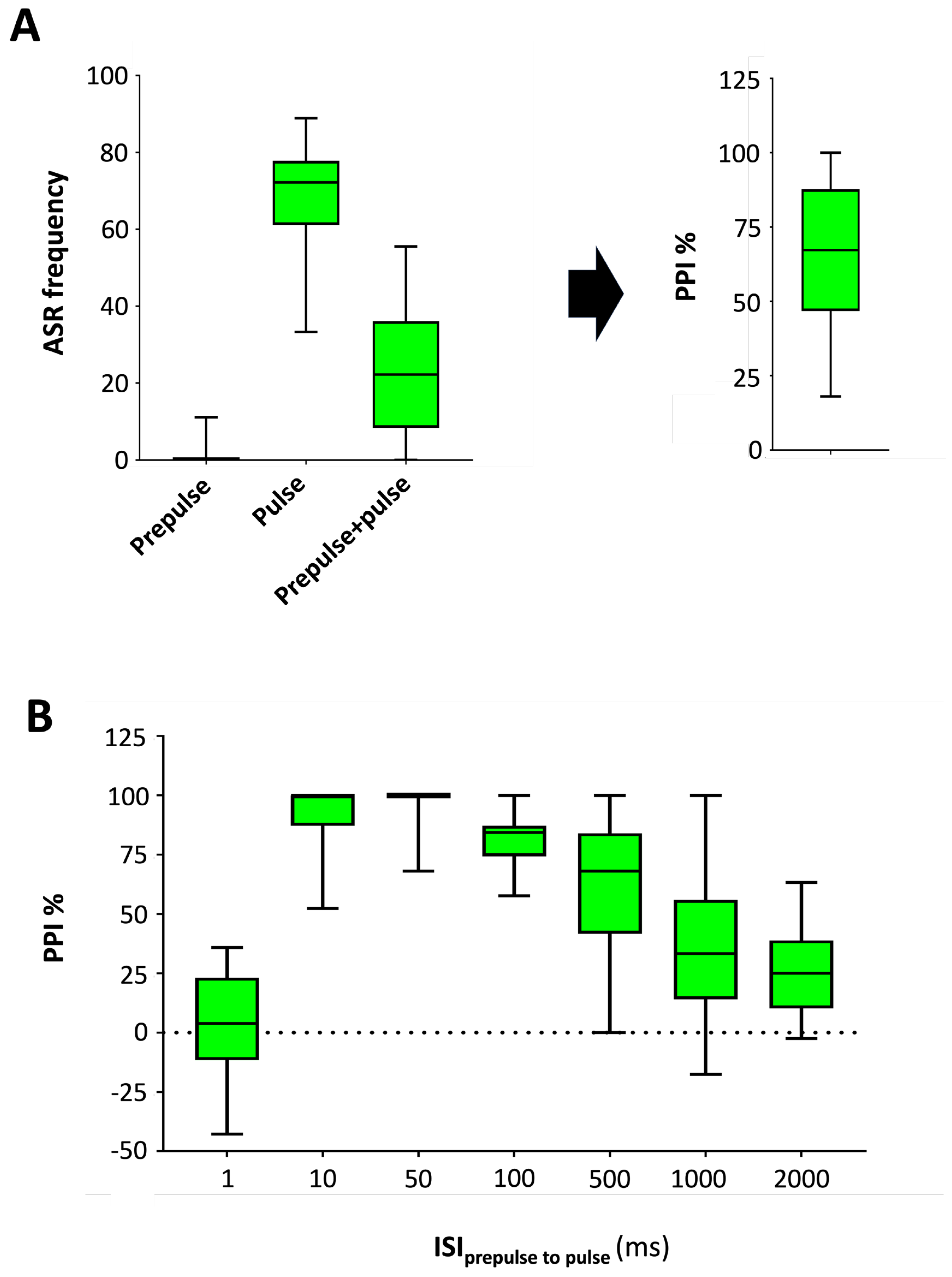

19]. Therefore, the suitability of Zebra_K to determine PPI in adult zebrafish was tested (

Figure 4A). First of all, an AV stimulus of 1000 Hz, 10 μs and 72.9 dB re 20 mPa, which typically elicited 0-10% startle responses, was selected as a prepulse. The startle-inducing stimulus used in the prehabituation step of the habituation protocol (1000 Hz, 1 ms, 103.9 dB re 20 mPa) was also selected for the pulse. The developed PPI protocol started with 5 prepulse stimuli (ISI: 120 s), followed by 5 pulse (ISI: 120 s) and finally by a series of 5 sequences prepulse+pulse (ISI

between sequences: 120 s), with the interval between prepulse and pulse to be determined.

Figure 4A shows that the median ASR frequencies during the prepulse and pulse steps were 0% (IQR: 0-0%) and 72.2% (IQR: 61.1-77.8%), respectively (individual data provided in Supplementary Dataset 4). A significant inhibition of the startle response, with only a 22.2% of responses (IQR: 8.3-36.1%), was found when the prepulse was delivered 100 ms before the pulse (

U(

Npulse=10,

Nprepulse+pulse=10) = 4.500, z = -3.471,

P = 1.3 x 10

-4), with a median PPI percentage of 67.2% (IQR: 46.7—87.7%). This PPI percentage is consistent with the reported by Burgess & Granato for wild-type adult fish [

19].

The effect of the interval between prepulse and pulse on the PPI magnitude was then analyzed. Whereas the pulse led a median ASR frequency of 77.8% (IQR: 66.7-88.9%) of the fish, this frequency decreased to 25.0% (IQR: 11.1-40%) or 44.4% (IQR: 25.0-55.6%) if a prepulse was delivered 500 or 1000 ms before the pulse, respectively. In contrast, when the prepulse was delivered 1 ms or 2000 ms before the pulse, it failed to decrease the ASR frequency. As shown in

Figure 4B, PPI % was maximal at intervals between 10-100 ms (data provided as Supplementary Dataset 5). The interval range leading to a significant PPI in adult zebrafish in this study, and the interval resulting in the maximal PPI% (50 ms), are consistent with the results reported elsewhere with wild-type adult zebrafish [

19]. However, in contrast to our results, no PPI was found in Tuebingen long-fin adult zebrafish when the prepulse was delivered 10 or 1000 ms before the pulse [

19]. Differences in the genetic background and/or the type of stimuli used could explain the wider range of intervals leading PPI in our study.

Pharmacological Modulation of ASR Sensitivity and Plasticity by the NMDA Receptor Antagonist Ketamine in Adult Zebrafish

In both mammalian models and zebrafish larvae, behavioral plasticity of ASR is modulated by N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists [

6,

19,

20]. However, no information is currently available about the modulation of ASR by NMDA-receptor antagonists in adult zebrafish. To evaluate the specific effects of NMDA receptor antagonists on habituation and PPI, a pretest-posttest control group design [

25] with ketamine was employed.

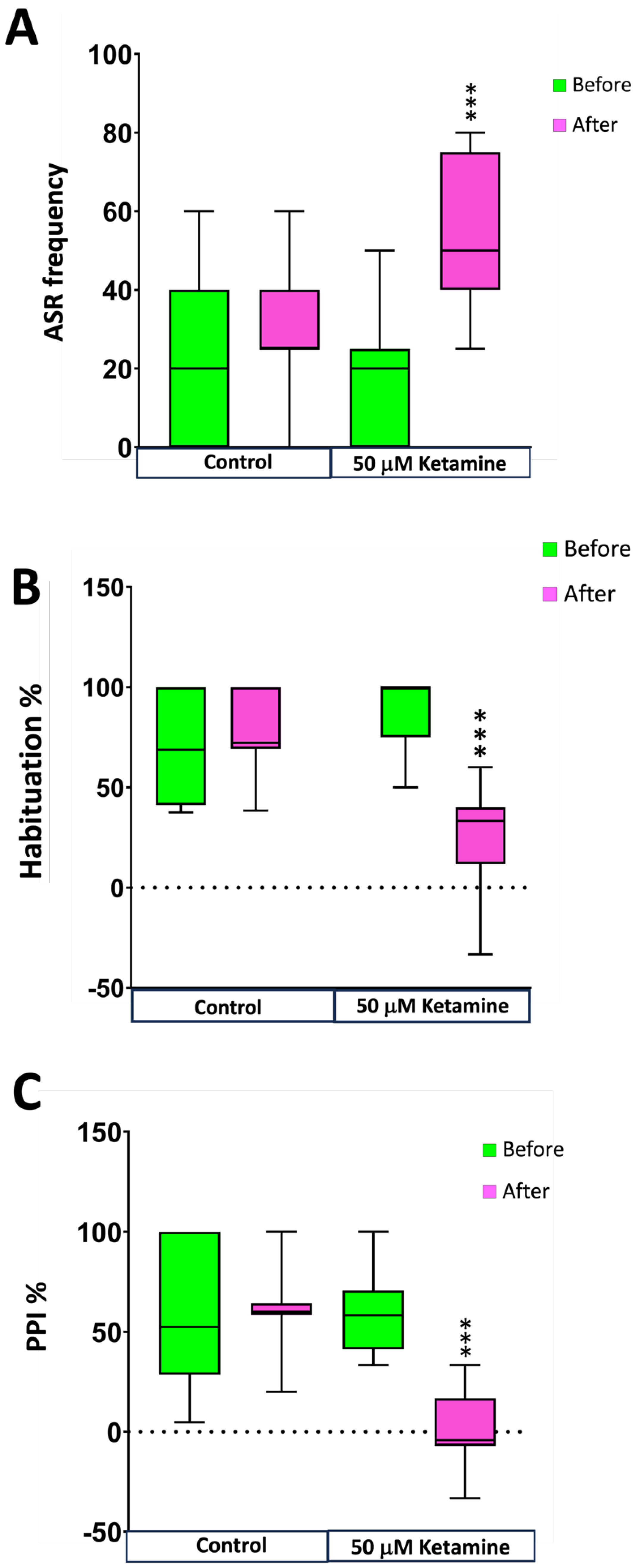

The detailed results of the modulation of ASR sensitivity and plasticity by ketamine are provided in the Supplementary Dataset 7. As shown in

Figure 5A, no differences in sensitivity were found between the control [20.0% (IQR: 0.0-40.0%)] and ketamine [20.0% (IQR: 0.0-25.0%)] groups before starting the treatment (pretest). Then, sensitivity was determined again in these groups 20 min after waterborne exposure to fish water (control group) or 50 μM of the NMDA-receptor antagonist ketamine (ketamine group; posttest). While no significant changes were found in the control group [25% (IQR:25-40%),

U(

Nbefore=15,

Nafter=14) = 122.00,

z = 0.765,

P = 0.477] ], a significant increase in the responsiveness was found during the sensitivity step of the habituation protocol in the ketamine-treated group [50% (IQR:40-75%),

U(

Nbefore=15,

Nafter=14) = 197.00,

z = 4.063,

P = 9.6 x 10

-6]. Wolman et al. [

20] reported a similar increase in responsiveness to ASR in zebrafish larvae after the exposure to the NMDA receptor antagonists MK-801 and ketamine. Interestingly, this effect of the ketamine in larvae was observed at a ketamine concentration 10-fold higher than that used with adults in our study. In addition to increasing sensitivity to the acoustic stimulus, ketamine exposure also led a strong decrease in the habituation percentage [

U(

Nbefore = 15,

Nafter = 15) = 1.000, z = -4.700,

P = 2.6 x 10

-8)]. As shown in

Figure 5B, while no differences were found in the control groups before and after treatment [

U(

Nbefore = 15,

Nafter = 15) = 151.000, z = 1.641,

P = 0.116)], the percentage of habituation decreased from 100% (75-100%) to 33.3% (11.8-40%) after ketamine treatment. These results on the effect of this NMDA receptor antagonist on the short-term habituation of ASR in adult zebrafish are consistent with the reported decrease in habituation evoked by ketamine and MK-801 in zebrafish larvae [

20].

In order to determine the effect of ketamine on the PPI percentage of adult zebrafish, a 500 ms interstimulus interval between the prepulse and the pulse was used. As shown in

Figure 5C, while no differences were observe in the control groups before and after treatment [

U(

Nbefore = 15,

Nafter = 15) = 151.500, z = 1.632,

P = 0.106)], a total abolition of the PPI was found 20 min after exposure to 50 μM ketamine [

U(

Nbefore = 15,

Nafter = 15) = 0.500, z = -4.667,

P = 1.3 x 10

-8)]. These results are consistent with an strong decrease in PPI% previously reported in zebrafish larvae exposed to 100 μM ketamine for 10 min using the same prepulse-to-pulse interval [

19]. However, the effect of ketamine on PPI appears to depend on the prepulse-to-pulse interval used, with intervals of 30 or 100 ms reported to increase the PPI percentage in ketamine exposed larvae [

19,

21]. The observed effect of ketamine on sensorymotor gating in adult zebrafish in this study is also consistent with the reported effect of this NMDA receptor antagonist on PPI in different mammalian models[

35,

36,

37].

Physiological Modulation of ASR Sensitivity and Plasticity by Gender in Adult Zebrafish

While a significative effect of gender on ASR modulation has been reported in humans [

38], no information is currently available for zebrafish. The detailed results of the modulation of ASR sensitivity and plasticity by fish gender are provided in Supplementary Dataset 8.

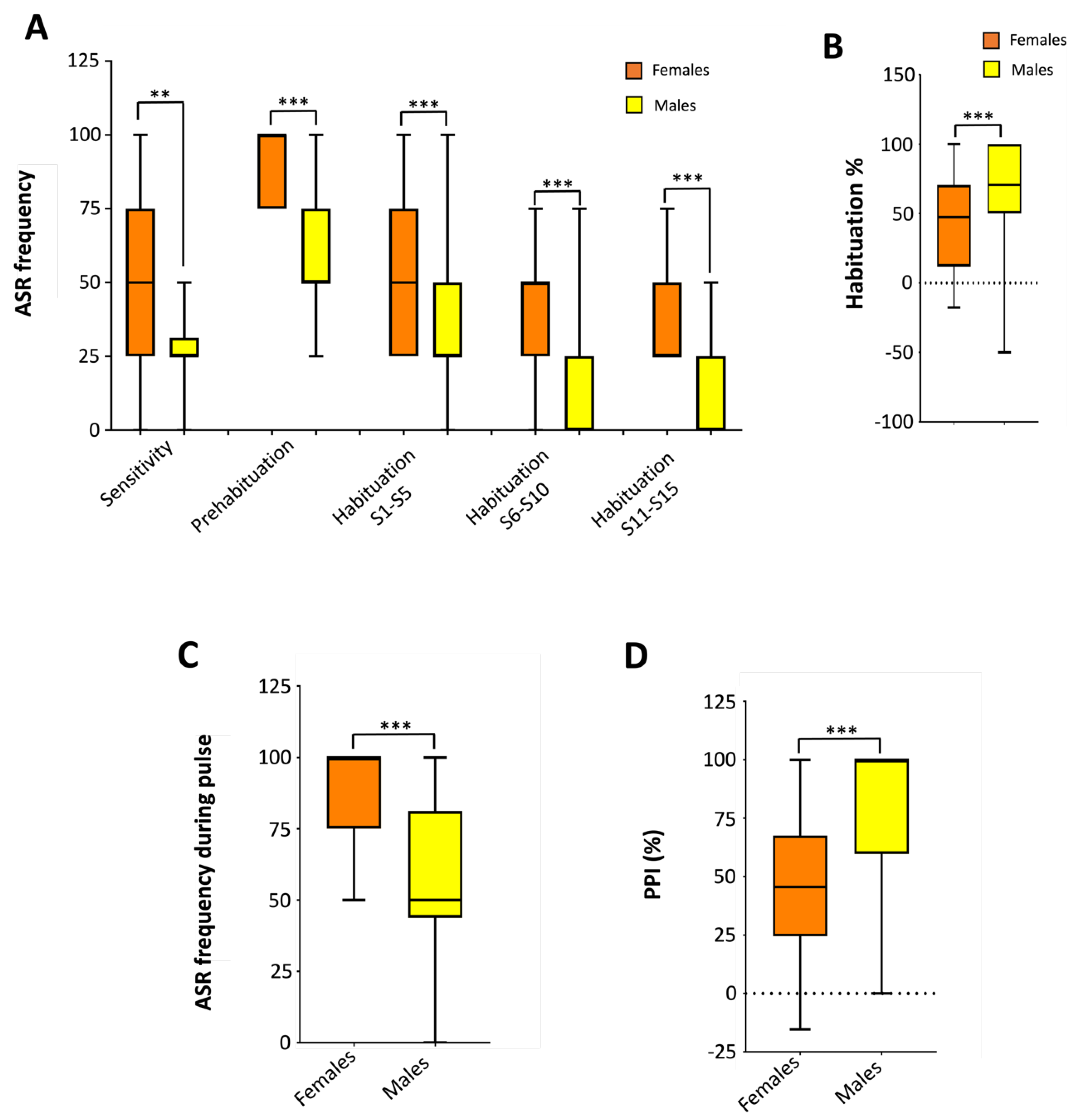

Figure 6A shows that females exhibit a higher responsiveness than males [

U(

Nfemales = 30,

Nmales = 30) = 640.000,

z = 2.954,

P = 0.003] to acoustic stimuli from mild to moderate level [50.0% (25.0-75.0%) vs 25.0% (25.0-31.2%) for females and males, respectively] during the sensitivity step of the habituation protocol. Similarly, females exhibit a higher responsiveness [

U(

Nfemales = 30,

Nmales = 30) = 771.000,

z = 5.013,

P = 5.4 x 10

-7] to the strong acoustic stimuli used for the prehabituation step [100.0% (75.0-100.0%) vs 50.0% (50.0-75.0%) for females and males, respectively]. Moreover, as shown in

Figure 6B, females exhibit a significatively lower habituation than males to a series of acoustic stimuli [70.6% (41.2-73.7%) vs 100.0% (61.5-100.0%) habituation percentage for females and males, respectively;

U(

Nfemales = 30,

Nmales = 30) = 201.000,

z = -3.764,

P = 1.7 x 10

-4). These results are consistent with the reported gender effect on ASR in humans, where women exhibit higher responsiveness to ASR and lower habituation than men [

38].

The effect of gender on sensorimotor gating of ASR was studied using the PPI protocol. As shown in

Figure 6D, females exhibit increased responsiveness to the acoustic stimulus used for the pulse [100.0% (75.0-100.0%) vs 50.0% (43.8-81.2%) of ASR for females and males, respectively;

U(

Nfemales = 30,

Nmales = 30) = 727.000,

z = 4.389,

P = 1.1 x 10

-5]. This result is consistent with what was observed during the prehabituation step, since in both cases the same stimulus was used. Finally,

Figure 6D shows that PPI percentage is significantly lower in females than in males [45.6% (24.5-67.6%) vs 100% (59.7-100.0%) of PPI % in females and males, respectively;

U(

Nfemales = 30,

Nmales = 30) = 198.000,

z = -3.789,

P = 1.5 x 10

-4], consistent with the lower values of PPI reported in females both in humans [

39] and rodent models [

40] compared to males.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: D.R., S.P., J.M.P.; Methodology: S.P., J.M.P.; Formal Analysis: D.R; Software: S.P., J.M.P.; Investigation: M.S., N.T., C.R.M., O.A., E.P.; Resources, D.R. and C.F.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: D.R., M.S., N.T., C.R.M., S.P., O.A., E.P., C.F., and J.M.P.; Writing—Review and Editing: D.R., M.S., N.T., C.R.M., S.P., O.A., E.P., C.F., and J.M.P.; Visualization, D.R., M.S.; Supervision, D.R., C.F., and J.M.P.; Project Administration, D.R.; Funding Acquisition, D.R., C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was carried out in the framework of the European Partnership for the Assessment of Risks from Chemicals (PARC) and has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No 101057014, by “Agencia Estatal de Investigación” from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, (PID2023-148502OB-C21 and PDC2021-120754-I00), and by IDAEA-CSIC, Severo Ochoa Centre of Excellence (CEX2018-000794-S).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the CID-CSIC (OH 1032/2020) and conducted in accordance with the institutional guidelines under a license from the local government (agreement number 11336).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the manuscript and its Supplementary Material file or will be made available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lauer, A.M.; Behrens, D.; Klump, G. Acoustic startle modification as a tool for evaluating auditory function of the mouse: Progress, pitfalls, and potential. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 77, 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Nieto, R.; de Horta-Júnior, J. de A.C.; Castellano, O.; Millian-Morell, L.; Rubio, M.E.; López, D.E. Origin and function of short-latency inputs to the neural substrates underlying the acoustic startle reflex. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegelaar, S.E.; Olff, M.; Bour, L.J.; Veelo, D.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Van Bruggen, G.; De Vries, G.J.; Raabe, S.; Cupido, C.; Koelman, J.H.T.M.; et al. The auditory startle response in post-traumatic stress disorder. Exp. Brain Res. 2006, 174, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Toth, M. Fragile X mice develop sensory hyperreactivity to auditory stimuli. Neuroscience 2001, 103, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, T.P.; Shin, S.; Fertan, E.; Dingle, R.N.; Almuklass, A.; Gunn, R.K.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J.; Brown, R.E. Reduced acoustic startle response and peripheral hearing loss in the 5xFAD mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Genes, Brain Behav. 2017, 16, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M. The neurobiology of startle. Prog. Neurobiol. 1999, 59, 107–128. [Google Scholar]

- López-Schier, H. Neuroplasticity in the acoustic startle reflex in larval zebrafish. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2019, 54, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Nieto, R.; Hormigo, S.; López, D.E. Prepulse inhibition of the auditory startle reflex assessment as a hallmark of brainstem sensorimotor gating mechanisms. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swerdlow, N.R.; Geyer, M.A. Using an animal model of deficient sensorimotor gating to study the pathophysiology and new treatments of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1998, 24, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoenig, K.; Hochrein, A.; Quednow, B.B.; Maier, W.; Wagner, M. Impaired prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 57, 1153–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K. Why is prepulse inhibition disrupted in schizophrenia? Med. Hypotheses 2020, 143, 109901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, A.; Yee, B.K.; Feldon, J.; Ferger, B. Acoustic startle response, prepulse inhibition, and spontaneous locomotor activity in MPTP-treated mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2004, 154, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, Z.; Kolb, B.E.; Mohajerani, M.H. Prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle reflex and P50 gating in aging and alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 59, 101028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quednow, B.B.; Kühn, K.U.; Hoenig, K.; Maier, W.; Wagner, M. Prepulse inhibition and habituation of acoustic startle response in male MDMA ('Ecstasy’) users, cannabis users, and healthy controls. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004, 29, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preller, K.H.; Ingold, N.; Hulka, L.M.; Vonmoos, M.; Jenni, D.; Baumgartner, M.R.; Vollenweider, F.X.; Quednow, B.B. Increased sensorimotor gating in recreational and dependent cocaine users is modulated by craving and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 73, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, P.P.J.; Goizet, C.; Raldúa, D. Zebrafish models of human motor neuron diseases: Advantages and limitations. Prog. Neurobiol. 2014, 118, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fero, K.; Yokogawa, T.; Burgess, H.A. The behavioral repertoire of larval zebrafish. In Zebrafish models in neurobehavioral research; Springer, 2011; pp. 249–291. [Google Scholar]

- Medan, V.; Preuss, T. The Mauthner-cell circuit of fish as a model system for startle plasticity. J. Physiol. 2014, 108, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, H.A.; Granato, M. Sensorimotor gating in larval zebrafish. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 4984–4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolman, M.A.; Jain, R.A.; Liss, L.; Granato, M. Chemical modulation of memory formation in larval zebrafish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 15468–15473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banono, N.S.; Esguerra, C. V. Pharmacological validation of the prepulse inhibition of startle response in larval zebrafish using a commercial automated system and software. J. Vis. Exp. 2020, 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauer, J.; Zhou, M.; Ye, S.; Menegas, W.; Schneider, S.; Nath, T.; Rahman, M.M.; Di Santo, V.; Soberanes, D.; Feng, G.; et al. Multi-animal pose estimation, identification and tracking with DeepLabCut. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath, T.; Mathis, A.; Chen, A.C.; Patel, A.; Bethge, M.; Mathis, M.W. Using DeepLabCut for 3D markerless pose estimation across species and behaviors. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 2152–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathis, A.; Mamidanna, P.; Cury, K.M.; Abe, T.; Murthy, V.N.; Mathis, M.W.; Bethge, M. DeepLabCut: Markerless pose estimation of user-defined body parts with deep learning. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, D.M.; Rumrill, P.D. Pretest-posttest designs and measurement of change. Work 2003, 20, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Santistevan, N.J.; Nelson, J.C.; Ortiz, E.A.; Miller, A.H.; Halabi, D.K.; Sippl, Z.A.; Granato, M.; Grinblat, Y. Cacna2D3, a Voltage-Gated Calcium Channel Subunit, Functions in Vertebrate Habituation Learning and the Startle Sensitivity Threshold. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meserve, J.H.; Nelson, J.C.; Marsden, K.C.; Hsu, J.; Echeverry, F.A.; Jain, R.A.; Wolman, M.A.; Pereda, A.E.; Granato, M. A forward genetic screen identifies Dolk as a regulator of startle magnitude through the potassium channel subunit Kv1.1. PLoS Genet. 2021, 17, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, N.R.; Panlilio, J.M.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Ivashkin, E.; Stegeman, J.J.; Goldstone, J. V. Developmental exposure to non-dioxin-like polychlorinated biphenyls promotes sensory deficits and disrupts dopaminergic and GABAergic signaling in zebrafish. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Inoue, M.; Tanimoto, M.; Kohashi, T.; Oda, Y.; Martin, R.M.; Bereman, M.S.; Marsden, K.C.; Santistevan, N.J.; Nelson, J.C.; et al. Developmental neurotoxicity of the harmful algal bloom toxin domoic acid: Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying altered behavior in the zebrafish model. Curr. Biol. 2020, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaramella, C.; Alzagatiti, J.B.; Creighton, C.; Mankatala, S.; Licea, F.; Winter, G.M.; Emtage, J.; Wisnieski, J.R.; Salazar, L.; Hussain, A.; et al. Bisphenol A Exposure Induces Sensory Processing Deficits in Larval Zebrafish during Neurodevelopment. eNeuro 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolman, M.A.; Jain, R.A.; Marsden, K.C.; Bell, H.; Skinner, J.; Hayer, K.E.; Hogenesch, J.B.; Granato, M. A Genome-wide Screen Identifies PAPP-AA-Mediated IGFR Signaling as a Novel Regulator of Habituation Learning. Neuron 2015, 85, 1200–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.A.; Wolman, M.A.; Marsden, K.C.; Nelson, J.C.; Shoenhard, H.; Echeverry, F.A.; Szi, C.; Bell, H.; Skinner, J.; Cobbs, E.N.; et al. A Forward Genetic Screen in Zebrafish Identifies the G-Protein-Coupled Receptor CaSR as a Modulator of Sensorimotor Decision Making. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, 1357–1369.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandiwad, A.A.; Raible, D.W.; Rubel, E.W.; Sisneros, J.A. Noise-Induced Hypersensitization of the Acoustic Startle Response in Larval Zebrafish. JARO - J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2018, 19, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandiwad, A.A.; Zeddies, D.G.; Raible, D.W.; Rubel, E.W.; Sisneros, J.A. Auditory sensitivity of larval zebrafish (Danio rerio) measured using a behavioral prepulse inhibition assay. J. Exp. Biol. 2013, 216, 3504–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandner, G.; Canal, N.M.; Brandão, M.L. Effects of ketamine and apomorphine on inferior colliculus and caudal pontine reticular nucleus evoked potentials during prepulse inhibition of the startle reflex in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2002, 128, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansbach, R.S.; Geyer, M.A. Parametric determinants in pre-stimulus modification of acoustic startle: Interaction with ketamine. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1991, 105, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canal, N.M.; Gourevitch, R.; Sandner, G. Non-monotonic dependency of PPI on temporal parameters: Differential alteration by ketamine and MK-801 as opposed to apomorphine and DOI. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2001, 156, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofler, M.; Müller, J.; Reggiani, L.; Valls-Solé, J. Influence of gender on auditory startle responses. Brain Res. 2001, 921, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swerdlow, N.R.; Auerbach, P.; Monroe, S.M.; Hartston, H.; Geyer, M.A.; Braff, D.L. Men are more inhibited than women by weak prepulses. Biol. Psychiatry 1993, 34, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Pryce, C.R.; Feldon, J. Sex differences in the acoustic startle response and prepulse inhibition in Wistar rats. Behav. Brain Res. 1999, 104, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Zebra_K observation chamber. (A-B) General view of the experimental Zebra_K observation chamber, including the initial model (A) and its actual implementation (B); (C) Diagram of the platform, identifying the main components and connections of the observation chamber; (D) Detail of the illumination and vibration system for each tank.

Figure 1.

Zebra_K observation chamber. (A-B) General view of the experimental Zebra_K observation chamber, including the initial model (A) and its actual implementation (B); (C) Diagram of the platform, identifying the main components and connections of the observation chamber; (D) Detail of the illumination and vibration system for each tank.

Figure 2.

Kinematic values of 1875 acoustic startle responses (ASR) in adult zebrafish. Histograms of latency (A) and C-bend angle (B), and the main kinematic values of these responses (C). IQR: interquartile range.

Figure 2.

Kinematic values of 1875 acoustic startle responses (ASR) in adult zebrafish. Histograms of latency (A) and C-bend angle (B), and the main kinematic values of these responses (C). IQR: interquartile range.

Figure 3.

Adult zebrafish habituation to acoustic stimuli using Zebra_K. (A) Main steps of the habituation of acoustic startle response (ASR) protocol optimized for adult zebrafish. (B) Trace of the mean ASR frequencies in adult zebrafish using the developed protocol. Results of 10 groups of fish (51 fish in total), presented as mean ± SEM. (C) ASR habituation calculated as the ratio of the responses during the first (1-5), second (6-10), or last (11-15) stimuli during the habituation step to the responses during the 5 stimuli delivered during the prehabituation step. Data are presented as boxplots where the box indicates the 25th and 75th percentiles, the thin line within the box marks the median and the whiskers the maximum and minimum values. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; Kruskal Wallis test with Bonferroni correction. Data from 3 independent experiments.

Figure 3.

Adult zebrafish habituation to acoustic stimuli using Zebra_K. (A) Main steps of the habituation of acoustic startle response (ASR) protocol optimized for adult zebrafish. (B) Trace of the mean ASR frequencies in adult zebrafish using the developed protocol. Results of 10 groups of fish (51 fish in total), presented as mean ± SEM. (C) ASR habituation calculated as the ratio of the responses during the first (1-5), second (6-10), or last (11-15) stimuli during the habituation step to the responses during the 5 stimuli delivered during the prehabituation step. Data are presented as boxplots where the box indicates the 25th and 75th percentiles, the thin line within the box marks the median and the whiskers the maximum and minimum values. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; Kruskal Wallis test with Bonferroni correction. Data from 3 independent experiments.

Figure 4.

Prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle response (ASR) in adult zebrafish. (A) ASR frequency during the prepulse, pulse and the prepulse+pulse sequence. In each experiment 9 adult zebrafish were acclimated to the Zebra_K observation chamber and then, 5 prepulses of mild acoustic stimuli were delivered with an interstimulus interval (ISI) of 120 s. Then, 5 strong acoustic stimuli pulses followed by 5 prepulse+pulse sequences were delivered using the same ISI. In each sequence, the interval between the prepulse and the pulse was 100 ms. The boxplot on the right represents the percentage of PPI, calculated from the ASR during the pulse and during the prepulse+pulse sequences. (B) Analysis of the effect of different interstimulus intervals (ISI) between prepulse and pulse on the percentage of PPI. Data are presented as boxplots where the box indicates the 25th and 75th percentiles, the thin line within the box marks the median and the whiskers the maximum and minimum values. Data from 2 to 4 independent experiments with 9 adult wild-type short-fin zebrafish each.

Figure 4.

Prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle response (ASR) in adult zebrafish. (A) ASR frequency during the prepulse, pulse and the prepulse+pulse sequence. In each experiment 9 adult zebrafish were acclimated to the Zebra_K observation chamber and then, 5 prepulses of mild acoustic stimuli were delivered with an interstimulus interval (ISI) of 120 s. Then, 5 strong acoustic stimuli pulses followed by 5 prepulse+pulse sequences were delivered using the same ISI. In each sequence, the interval between the prepulse and the pulse was 100 ms. The boxplot on the right represents the percentage of PPI, calculated from the ASR during the pulse and during the prepulse+pulse sequences. (B) Analysis of the effect of different interstimulus intervals (ISI) between prepulse and pulse on the percentage of PPI. Data are presented as boxplots where the box indicates the 25th and 75th percentiles, the thin line within the box marks the median and the whiskers the maximum and minimum values. Data from 2 to 4 independent experiments with 9 adult wild-type short-fin zebrafish each.

Figure 5.

Effect of 20 min exposure to 50 μM ketamine on acoustic startle response (ASR) plasticity in adult zebrafish using a pretest-posttest control group design. Exposure to ketamine increases responsiveness to moderate-level stimuli during the sensitivity step of the habituation protocol (A), decreases the percentage of habituation to a series of strong-level acoustic stimuli (B) and leads to the total abolition of the prepulse inhibition (C). Data are presented as boxplots where the box indicates the 25th and 75th percentiles, the thin line within the box marks the median and the whiskers the maximum and minimum values. Mann–Whitney U test, *** P<0.001. Data from 3 independent experiments with 4-5 adult wild-type short-fin zebrafish by experimental group in each experiment.

Figure 5.

Effect of 20 min exposure to 50 μM ketamine on acoustic startle response (ASR) plasticity in adult zebrafish using a pretest-posttest control group design. Exposure to ketamine increases responsiveness to moderate-level stimuli during the sensitivity step of the habituation protocol (A), decreases the percentage of habituation to a series of strong-level acoustic stimuli (B) and leads to the total abolition of the prepulse inhibition (C). Data are presented as boxplots where the box indicates the 25th and 75th percentiles, the thin line within the box marks the median and the whiskers the maximum and minimum values. Mann–Whitney U test, *** P<0.001. Data from 3 independent experiments with 4-5 adult wild-type short-fin zebrafish by experimental group in each experiment.

Figure 6.

Effect of gender on ASR plasticity in adult zebrafish. Female fish exhibited higher responsiveness than males to the acoustic stimuli through the habituation protocol (A), and a decreased habituation to a series of strong level acoustic stimuli compared to males (B). Consistent to the higher responsiveness in the habituation protocol, females also exhibited a higher responsiveness to the pulse than males (C). Finally, prepulse inhibition in females was significantly lower than in males (D). Data are presented as boxplots where the box indicates the 25th and 75th percentiles, the thin line within the box marks the median and the whiskers the maximum and minimum values. **P<0.01, *** P<0.001; Mann–Whitney U test. Data from 3 independent experiments with 4-5 adult wild-type short-fin zebrafish by experimental group in each experiment.

Figure 6.

Effect of gender on ASR plasticity in adult zebrafish. Female fish exhibited higher responsiveness than males to the acoustic stimuli through the habituation protocol (A), and a decreased habituation to a series of strong level acoustic stimuli compared to males (B). Consistent to the higher responsiveness in the habituation protocol, females also exhibited a higher responsiveness to the pulse than males (C). Finally, prepulse inhibition in females was significantly lower than in males (D). Data are presented as boxplots where the box indicates the 25th and 75th percentiles, the thin line within the box marks the median and the whiskers the maximum and minimum values. **P<0.01, *** P<0.001; Mann–Whitney U test. Data from 3 independent experiments with 4-5 adult wild-type short-fin zebrafish by experimental group in each experiment.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

). The temporal evolution of

). The temporal evolution of  gives an accurate account of the reaction of the fish to the stimuli. The microprocessor and the high-speed camera allow the identification of the reactions with an accuracy up to the millisecond. In this way, all fish reactions can be properly detected. To facilitate the data analysis of each experiment, the software generates a comprehensive report with graphs of the analyzed angles, automatically identifying the escape reaction event (Supplementary Figure S5). Finally, the software summarizes the relevant statistics of the entire experiment, and outputs a report with the parameters in Supplementary Table S1. These are the data finally used to evaluate the fish responses.

gives an accurate account of the reaction of the fish to the stimuli. The microprocessor and the high-speed camera allow the identification of the reactions with an accuracy up to the millisecond. In this way, all fish reactions can be properly detected. To facilitate the data analysis of each experiment, the software generates a comprehensive report with graphs of the analyzed angles, automatically identifying the escape reaction event (Supplementary Figure S5). Finally, the software summarizes the relevant statistics of the entire experiment, and outputs a report with the parameters in Supplementary Table S1. These are the data finally used to evaluate the fish responses.