Submitted:

03 September 2024

Posted:

05 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Study Design

- Research Centers The study subjects are from the breast surgery departments of two large comprehensive hospitals.

- Inclusion Criteria 1) Female patients aged between 18 and 70. 2) Underwent radical breast cancer surgery. 3) Received at least one postoperative treatment (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or hormone therapy). 4) Signed informed consent.

- Exclusion Criteria 5) Concurrent severe diseases (e.g., cardiovascular diseases, severe liver or renal insufficiency). 6) Cognitive impairments or mental disorders preventing questionnaire completion. 7) Other factors that may affect CRF assessment (e.g., recent major surgeries).

Data Collection

- Demographic Information Age: Recorded at the time of surgery. Marital Status: Classified as single (never married, divorced, or widowed) or married.

- Medical History Information Disease Stage: Recorded according to the TNM staging system (Stages I, II, III). Pathological Type: Specific types of breast cancer. Surgical Method: Types of surgery performed (radical mastectomy, breast-conserving surgery, etc.). Postoperative Treatment Plans: Detailed records of adjuvant treatments (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormone therapy). Body Mass Index (BMI): Calculated based on height and weight.

- Lifestyle Information Exercise Frequency: Frequency of postoperative exercise, classified as daily, weekly, or monthly. Sleep Quality: Assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), including seven components: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. Classified as good, average, or poor.

- Psychological Status Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): HADS consists of 14 items, assessing anxiety (7 items) and depression (7 items), with each item scored from 0 to 3. The total score for each dimension ranges from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety or depression.

- Fatigue Assessment Cancer-Related Fatigue Scale (CFS): The CFS includes 10 items, each scored from 0 to 10, with a total score ranging from 0 to 100. Higher scores indicate greater fatigue.

Statistical Analysis

- Descriptive Analysis

- 2.

- Univariate and Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards Regression

- 3.

- Propensity Score Matching (PSM)

- 4.

- Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis

- 5.

- Random Forest Survival Analysis

- 6.

- Restricted Cubic Spline Analysis

Results

- Baseline Characteristics Analysis

- 2.

- Univariate and Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis

- 3.

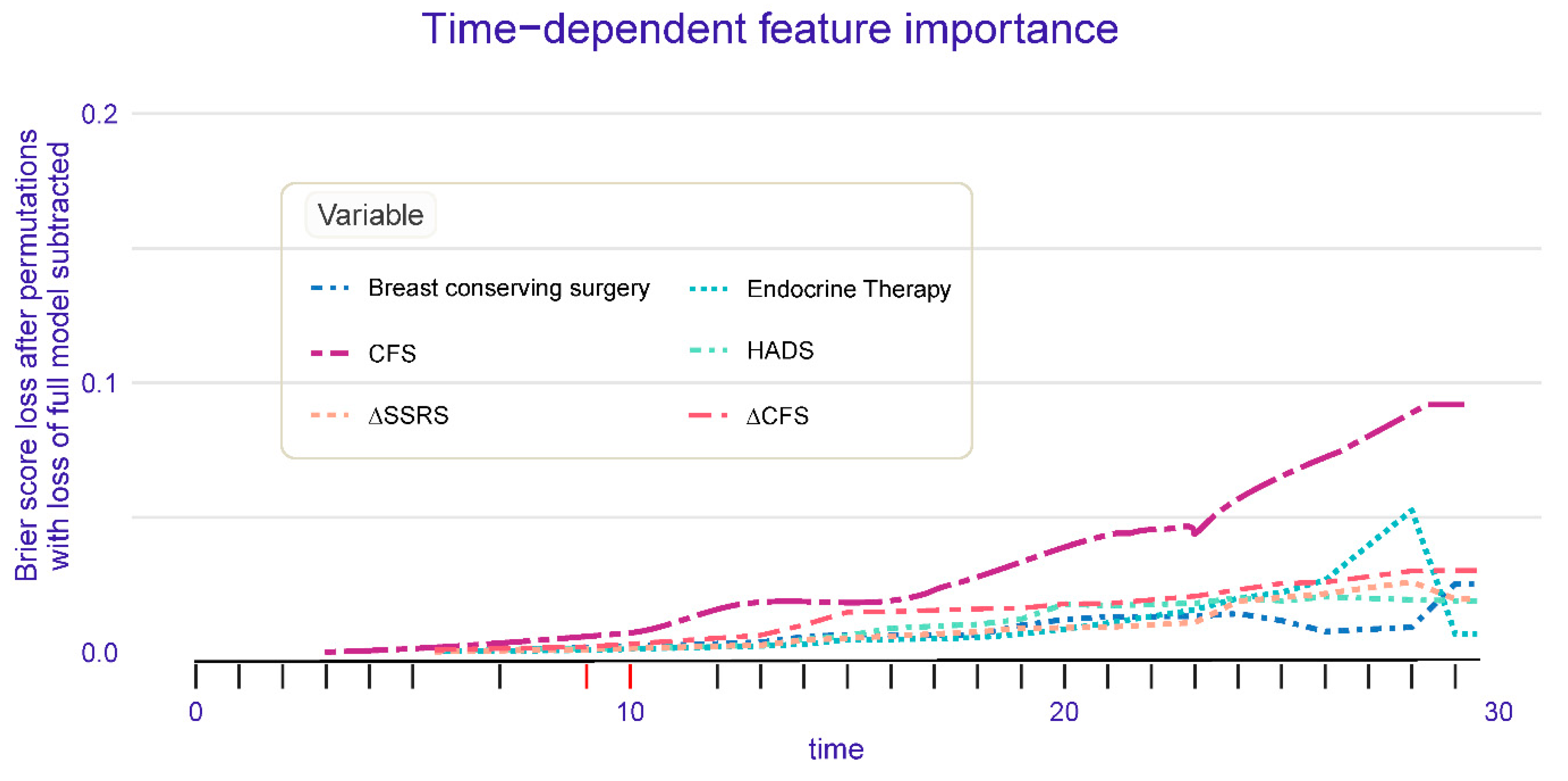

- Random Forest Survival Analysis Results

- 4.

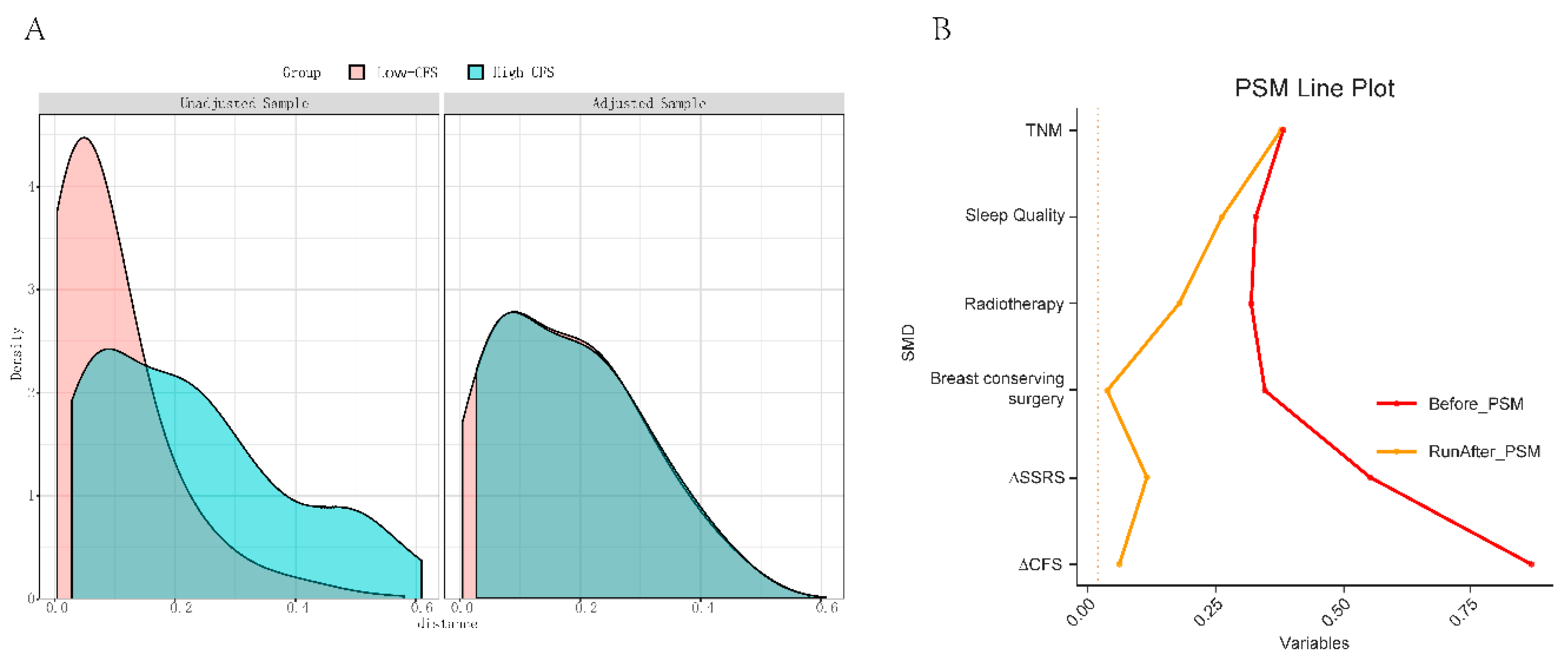

- Propensity Score Matching Analysis Results

- 5.

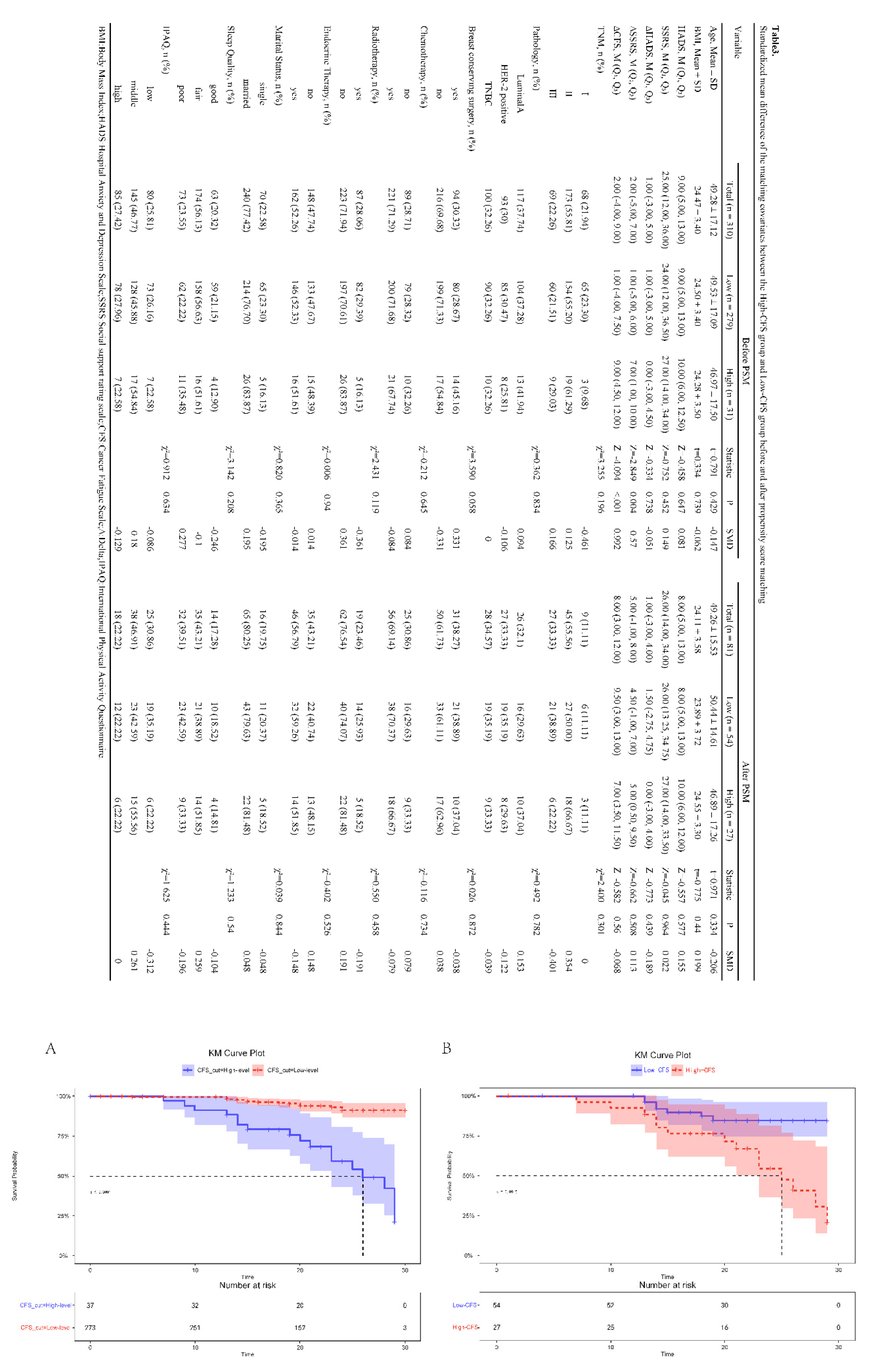

- Kaplan-Meier Survival Analysis Before and After Propensity Score Matching

- 6.

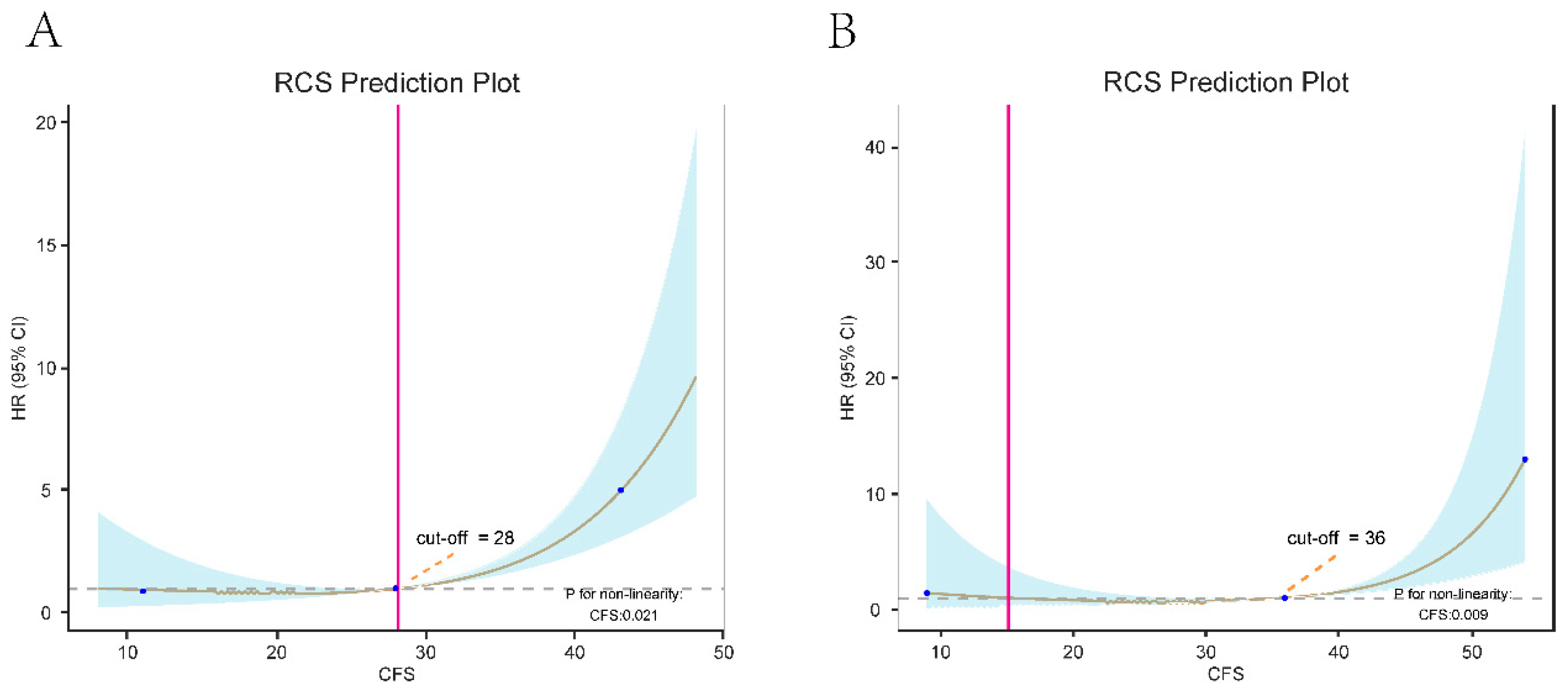

- Restricted Cubic Spline Analysis Before and After Propensity Score Matching

Discussion

Study Limitations

Future Research Directions

Conclusion

Declaration of Competing Interest

Ethics Statement

Manuscript Approval

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Schmidt, M.E.; Chang-Claude, J.; Vrieling, A.; Heinz, J.; Flesch-Janys, D.; Steindorf, K. Fatigue and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: temporal courses and long-term pattern. J. Cancer Surviv. 2012, 6, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, O.; Berger, A.; Barsevick, A.; Cramp, F.; Goedendorp, M.; Mitchell, S.A.; Stone, P.C. Cancer-related fatigue and its impact on functioning. Cancer 2013, 119, 2124–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger AM, Mooney K, Alvarez-Perez A, Breitbart WS, Carpenter KM, Cella D, Cleeland C, Dotan E, Eisenberger MA, Escalante CP, Jacobsen PB, Jankowski C, et al. Cancer-Related Fatigue, Version 2.2015. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN 2015;13: 1012-39.

- Bower, JE. Cancer-related fatigue--mechanisms, risk factors, and treatments. Nature reviews Clinical oncology 2014;11: 597-609.

- Glaus, A.; Crow, R.; Hammond, S. A qualitative study to explore the concept of fatigue/tiredness in cancer patients and in healthy individuals. Support. Care Cancer 1996, 4, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmann, K.; Mehnert, A.; Geue, K.; Hinz, A. Fatigue in breast cancer patients: psychometric evaluation of the fatigue questionnaire EORTC QLQ-FA13. Breast Cancer 2014, 22, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Raaf PJ, de Klerk C, van der Rijt CC. Elucidating the behavior of physical fatigue and mental fatigue in cancer patients: a review of the literature. Psycho-oncology 2013;22: 1919-29.

- Schmidt, M.E.; Chang-Claude, J.; Seibold, P.; Vrieling, A.; Heinz, J.; Flesch-Janys, D.; Steindorf, K. Determinants of long-term fatigue in breast cancer survivors: results of a prospective patient cohort study. Psycho-Oncology 2015, 24, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D.; Bennett, B.; Friedlander, M.; Davenport, T.; Hickie, I.; Lloyd, A. Fatigue states after cancer treatment occur both in association with, and independent of, mood disorder: a longitudinal study. BMC Cancer 2006, 6, 240–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry-Amar M, Busson R. Does persistent fatigue in survivors relate to cancer? The Lancet Oncology 2016;17: 13512.

- Potthoff, K.; E Schmidt, M.; Wiskemann, J.; Hof, H.; Klassen, O.; Habermann, N.; Beckhove, P.; Debus, J.; Ulrich, C.M.; Steindorf, K. Randomized controlled trial to evaluate the effects of progressive resistance training compared to progressive muscle relaxation in breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy: the BEST study. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 162–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.E.; Wiskemann, J.; Krakowski-Roosen, H.; Knicker, A.J.; Habermann, N.; Schneeweiss, A.; Ulrich, C.M.; Steindorf, K. Progressive resistance versus relaxation training for breast cancer patients during adjuvant chemotherapy: Design and rationale of a randomized controlled trial (BEATE study). Contemp. Clin. Trials 2013, 34, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.E.; Wiskemann, J.; Armbrust, P.; Schneeweiss, A.; Ulrich, C.M.; Steindorf, K. Effects of resistance exercise on fatigue and quality of life in breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 137, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steindorf, K.; Schmidt, M.E.; Klassen, O.; Ulrich, C.M.; Oelmann, J.; Habermann, N.; Beckhove, P.; Owen, R.; Debus, J.; Wiskemann, J.; et al. Randomized, controlled trial of resistance training in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant radiotherapy: results on cancer-related fatigue and quality of life. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 2237–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.M.; Marquis, J.N.; Taylor, C.B. A script for deep muscle relaxation. DisNervSyst. 1977, 38, 703–8. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahams, H.J.G.; Gielissen, M.F.M.; Schmits, I.C.; Verhagen, C.A.H.H.V.M.; Rovers, M.M.; Knoop, H. Risk factors, prevalence, and course of severe fatigue after breast cancer treatment: a meta-analysis involving 12 327 breast cancer survivors. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.E.; Chang-Claude, J.; Seibold, P.; Vrieling, A.; Heinz, J.; Flesch-Janys, D.; Steindorf, K. Determinants of long-term fatigue in breast cancer survivors: results of a prospective patient cohort study. Psycho-Oncology 2015, 24, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Person, H.; Guillemin, F.; Conroy, T.; Velten, M.; Rotonda, C. Factors of the evolution of fatigue dimensions in patients with breast cancer during the 2 years after surgery. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 146, 1827–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, D.; Bennett, B.K.; Webber, K.; Boyle, F.; de Souza, P.L.; Wilcken, N.R.; Scott, E.M.; Toppler, R.; Murie, P.; O'Malley, L.; et al. Cancer-Related Fatigue in Women With Breast Cancer: Outcomes of a 5-Year Prospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 1805–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, N.; Candel, M.J.J.M.; Schouten, H.C.; Abu-Saad, H.H.; Courtens, A.M. Prevalence and course of fatigue in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 2004, 15, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, N.; Candel, M.J.J.M.; Schouten, H.C.; Abu-Saad, H.H.; Courtens, A.M. Course of mental fatigue and motivation in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 2005, 16, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karshikoff, B.; Sundelin, T.; Lasselin, J. Role of Inflammation in Human Fatigue: Relevance of Multidimensional Assessments and Potential Neuronal Mechanisms. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandani-Susan, B.; Montazeri, A.; Haghighizadeh, M.H.; Araban, M. The effect of mobile health educational intervention on body image and fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Ir. J. Med Sci. 2022, 191, 1599–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighat, S.; Akbari, M.E.; Holakouei, K.; Rahimi, A.; Montazeri, A. Factors predicting fatigue in breast cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2003, 11, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, G.D.l.C.; Karamchandani, M.; Chambergo-Michilot, D.; Narvaez-Rojas, A.R.; Jonczyk, M.; Príncipe-Meneses, F.S.; Posawatz, D.; Nardello, S.; Chatterjee, A. Does Breast-Conserving Surgery with Radiotherapy have a Better Survival than Mastectomy? A Meta-Analysis of More than 1,500,000 Patients. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 6163–6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J.; Sgroi, D.; Treuner, K.; Zhang, Y.; Ahmed, I.; Piper, T.; Salunga, R.; Brachtel, E.; Pirrie, S.; Schnabel, C.; et al. Breast Cancer Index and prediction of benefit from extended endocrine therapy in breast cancer patients treated in the Adjuvant Tamoxifen—To Offer More? (aTTom) trial. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1776–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Total (n = 310) | Stable (n = 276) | Recurrence (n = 34) | Statistic | P | SMD |

| Age, Mean ± SD | 49.28 ± 17.12 | 49.22 ± 16.94 | 49.76 ± 18.79 | t=-0.176 | 0.861 | 0.029 |

| BMI, Mean ± SD | 24.47 ± 3.40 | 24.55 ± 3.38 | 23.83 ± 3.59 | t=1.172 | 0.242 | -0.202 |

| HADS, M (Q₁, Q₃) | 9.00 (5.00, 13.00) | 9.00 (5.00, 13.00) | 11.00 (7.00, 14.50) | Z=-2.145 | 0.032 | 0.438 |

| SSRS, M (Q₁, Q₃) | 25.00 (12.00, 36.00) | 24.50 (12.00, 36.00) | 27.50 (17.00, 38.25) | Z=-0.889 | 0.374 | 0.154 |

| CFS, M (Q₁, Q₃) | 28.00 (18.25, 37.00) | 27.00 (17.00, 35.25) | 44.00 (26.00, 53.50) | Z=-5.393 | <.001 | 1.018 |

| ∆HADS, M (Q₁, Q₃) | 1.00 (-3.00, 5.00) | 0.00 (-3.00, 4.00) | 2.00 (0.00, 5.00) | Z=-1.775 | 0.076 | 0.388 |

| ∆SSRS, M (Q₁, Q₃) | 2.00 (-5.00, 7.00) | 1.00 (-5.00, 6.00) | 5.00 (1.00, 9.00) | Z=-2.961 | 0.003 | 0.66 |

| ∆CFS, M (Q₁, Q₃) | 2.00 (-4.00, 9.00) | 1.00 (-4.00, 7.25) | 8.50 (3.25, 12.00) | Z=-4.155 | <.001 | 0.987 |

| TNM, n (%) | χ²=4.804 | 0.091 | ||||

| Ⅰ | 68 (21.94) | 65 (23.55) | 3 (8.82) | -0.519 | ||

| Ⅱ | 173 (55.81) | 153 (55.43) | 20 (58.82) | 0.069 | ||

| Ⅲ | 69 (22.26) | 58 (21.01) | 11 (32.35) | 0.242 | ||

| Pathology, n (%) | χ²=0.756 | 0.685 | ||||

| LuminalA | 117 (37.74) | 104 (37.68) | 13 (38.24) | 0.011 | ||

| HER-2 positive | 93 (30) | 81 (29.35) | 12 (35.29) | 0.124 | ||

| TNBC | 100 (32.26) | 91 (32.97) | 9 (26.47) | -0.147 | ||

| Breast conserving surgery, n (%) | χ²=11.808 | <.001 | ||||

| yes | 94 (30.32) | 75 (27.17) | 19 (55.88) | 0.578 | ||

| no | 216 (69.68) | 201 (72.83) | 15 (44.12) | -0.578 | ||

| Chemotherapy, n (%) | χ²=0.501 | 0.479 | ||||

| no | 89 (28.71) | 81 (29.35) | 8 (23.53) | -0.137 | ||

| yes | 221 (71.29) | 195 (70.65) | 26 (76.47) | 0.137 | ||

| Radiotherapy, n (%) | χ²=3.376 | 0.066 | ||||

| yes | 87 (28.06) | 82 (29.71) | 5 (14.71) | -0.424 | ||

| no | 223 (71.94) | 194 (70.29) | 29 (85.29) | 0.424 | ||

| Endocrine Therapy, n (%) | χ²=11.286 | <.001 | ||||

| no | 148 (47.74) | 141 (51.09) | 7 (20.59) | -0.754 | ||

| yes | 162 (52.26) | 135 (48.91) | 27 (79.41) | 0.754 | ||

| Marital Status, n (%) | χ²=1.355 | 0.244 | ||||

| single | 70 (22.58) | 65 (23.55) | 5 (14.71) | -0.25 | ||

| married | 240 (77.42) | 211 (76.45) | 29 (85.29) | 0.25 | ||

| Sleep Quality, n (%) | χ²=7.417 | 0.025 | ||||

| good | 63 (20.32) | 61 (22.10) | 2 (5.88) | -0.689 | ||

| fair | 174 (56.13) | 155 (56.16) | 19 (55.88) | -0.006 | ||

| poor | 73 (23.55) | 60 (21.74) | 13 (38.24) | 0.339 | ||

| IPAQ, n (%) | χ²=0.404 | 0.817 | ||||

| low | 80 (25.81) | 70 (25.36) | 10 (29.41) | 0.089 | ||

| middle | 145 (46.77) | 129 (46.74) | 16 (47.06) | 0.006 | ||

| high | 85 (27.42) | 77 (27.90) | 8 (23.53) | -0.103 |

| Variables | β | S.E | Z | Univariate P |

HR (95%CI) | Multivariate | ||||

| β | S.E | Z | P | HR (95%CI) | ||||||

| TNM Ⅰ Ⅱ Ⅲ |

0.73 1.14 |

0.62 0.65 |

1.18 1.75 |

0.237 0.08 |

1.00 (Reference) 2.08 (0.62 ~ 7.01) 3.13 (0.87 ~ 11.22) |

|||||

| Pathology LuminalA HER-2 positive TNBC |

0.08 -0.27 |

0.4 0.43 |

0.19 -0.62 |

0.851 0.535 |

1.00 (Reference) 1.08 (0.49 ~ 2.36) 0.76 (0.33 ~ 1.79) |

|||||

| Breast conserving surgery yes no |

-1.18 | 0.35 | -3.42 | <.001 | 1.00 (Reference) 0.31 (0.16 ~ 0.60) |

-0.85 | 0.38 | -2.26 | 0.024 | 1.00 (Reference) 0.43 (0.20 ~ 0.89) |

| Chemotherapy no yes | 0.24 | 0.4 | 0.59 | 0.558 | 1.00 (Reference) 1.27 (0.57 ~ 2.80) |

|||||

| Radiotherapy yes no | 0.89 | 0.48 | 1.83 | 0.068 | 1.00 (Reference) 2.42 (0.94 ~ 6.27) |

|||||

| Endocrine Therapy no yes |

1.43 | 0.43 | 3.37 | <.001 | 1.00 (Reference) 4.20 (1.82 ~ 9.68) |

1.96 | 0.51 | 3.88 | <.001 | 1.00 (Reference) 7.13 (2.64 ~ 19.22) |

| Marital Status single married | 0.52 | 0.49 | 1.07 | 0.285 | 1.00 (Reference) 1.68 (0.65 ~ 4.36) |

|||||

| Sleep Quality good fair poor |

1.26 1.87 |

0.74 0.76 |

1.7 2.46 |

0.09 0.014 |

1.00 (Reference) 3.53 (0.82 ~ 15.16) 6.46 (1.46 ~ 28.67) |

1.03 0.89 |

0.76 0.79 |

1.35 1.12 |

0.178 0.261 |

1.00 (Reference) 2.79 (0.63 ~ 12.45) 2.42 (0.52 ~ 11.35) |

| IPAQ low middle high Age BMI HADS, M SSRS, M CFS, M ∆HADS, M ∆SSRS, M |

-0.03 -0.26 0.01 -0.06 0.09 0.01 0.09 0.07 0.07 |

0.4 0. 470. 010. 050. 040. 010. 020. 040. 03 |

-0.07 -0.55 0.64 -1.29 2.51 0.78 5.37 1.89 2.59 |

0. 9430. 5850. 5250. 1960. 0120. 434<. 0010. 059 0.01 |

1.00 (Reference) 0.97 (0.44 ~ 2.14) 0.77 (0.30 ~ 1.96) 1.01 (0.99 ~ 1.03) 0.94 (0.85 ~ 1.03) 1.09 (1.02 ~ 1.17) 1.01 (0.99 ~ 1.04) 1.09 (1.06 ~ 1.13) 1.08 (1.00 ~ 1.16) 1.07 (1.02 ~ 1.13) |

0.08 0.07 0.06 |

0.04 0.02 0.03 |

2.15 3.9 2.22 |

0.032 <.001 0.026 |

1.09 (1.01 ~ 1.17) 1.07 (1.03 ~ 1.10) 1.07 (1.01 ~ 1.13) |

| ∆CFS, M | 0.1 | 0.03 | 4.05 | <.001 | 1.11 (1.06 ~ 1.17) | 0.07 | 0.03 | 2.23 | 0.026 | 1.07 (1.01 ~ 1.14) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).