1. Introduction

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) is a cytosolic rate-limiting enzyme of the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) that breaks down glucose, promotes the oxidation of the β-D-glucose-6-phosphate to D-glucono-1,5-lactone-6-phosphate, and produces a reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) as a byproduct in oxidative phase. Both enzymatic and genetic tests allow the evaluation of G6PD status. G6PD deficiency affecting near 400 million people in the world and it is more commonly expressed in males, compared to females [

1]. G6PD deficiency occurs most frequency in Asia, Africa, in the Mediterranean and the Middle East areas, synchronizing with endemic malaria [

2]. In Italy, G6PD deficiency is mainly present in Sardinia and Sicily (2-15%), but can also be found in Campania, Basilicata, Puglia, and Lazio regions [

3]. The spread of these variants is closely correlated with malaria: in areas where the disease was endemic, the

G6PD Mediterranean,

G6PD Cassano,

G6PD Seattle and

G6PD A- pathogenic variants (PVs) are mainly observed [

4].

More than 200 G6PD PVs are known [

5], and recently by searching publicly available databases 1041 variants have been listed [

6]. The World Health Organization (WHO) has recently revised their classification [

7]: variants in class A (formerly class I) are the more severe group, as they are associated with life-long chronic non-spherocytic haemolytic anaemia (CNSHA); persons with variants in class B (formerly class II and class III) are asymptomatic in the steady state, but they are at risk of acute haemolytic anaemia (AHA), that may be triggered by eating fava beans, by infections or by certain drugs [

8,

9].

In this study, we reported the clinical and genetics data of an asymptomatic 41-year-old woman that carried out G6PD gene testing, resulting in the presence of an unreported variant (c.1357G>A, NM_001360016.2). It was decided to name the novel variant as :G6PD Potenza”, with regard to the patient’s city of birth in Basilicata region. We speculated on the impact of the expected amino acid change p.(Val453Met) on the structure of the enzyme using several in silico analysis tools, all of which agreed on its deleterious effect.

Furthermore, typical local new variants were previously published by our group in Italy, suggesting the possible underestimation of the frequency of rare or novel

G6PD variants [

10,

11].

Finally, the combined use of Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) and Sanger sequencing as confirmatory method, allowed the correct annotation of the variant, initially misinterpreted as

G6PD Cassano variant [

12].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient

A 41-year-old woman comes from Basilicata region (Italy) was admitted to our hospital Fondazione Policlinico Universitario “Agostino Gemelli” IRCCS of Rome (Italy) to perform G6PD enzymatic and genetic analyses due to prenatal investigations and before artificial insemination treatment. The patient did not report any previous event suggestive of G6PD deficiency. The patient reported positive family history of favism occurring in two first degree cousins, one of paternal and one of maternal origin. Patient undergone a standard G6PD assay [

13]. The dosage of erythrocytic G6PD enzyme was performed evaluating the kinetic determination of G6PDH in erythrocytes, with the G6PD mensuration reagent kit on the Atellica CH 930 instrument (Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany). The enzyme dosage was expressed in U/g Hb, with reference range of 9.2-13.8 U/g Hb. The analysis was extended to family members who signed the consent.

2.2. Genomic Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood sample using the QIAamp DNA Mini kit on the Qiacube instrument (Qiagen, Milan, Italy), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The quantitation of the extracted DNA was performed using the Qubit dsDNA BR fluorimetric assays (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). The G6PD genotyping strategy routinely adopted in our laboratory consists in a “first level” evaluation of the most common mutations occurring in the Mediterranean area, as reported [

14]. In absence of mutation and in presence of G6PD deficiency and/or suggestive history of favism or G6PD-related disorders, a “second level” analysis was carried out with full-gene Sanger sequencing.

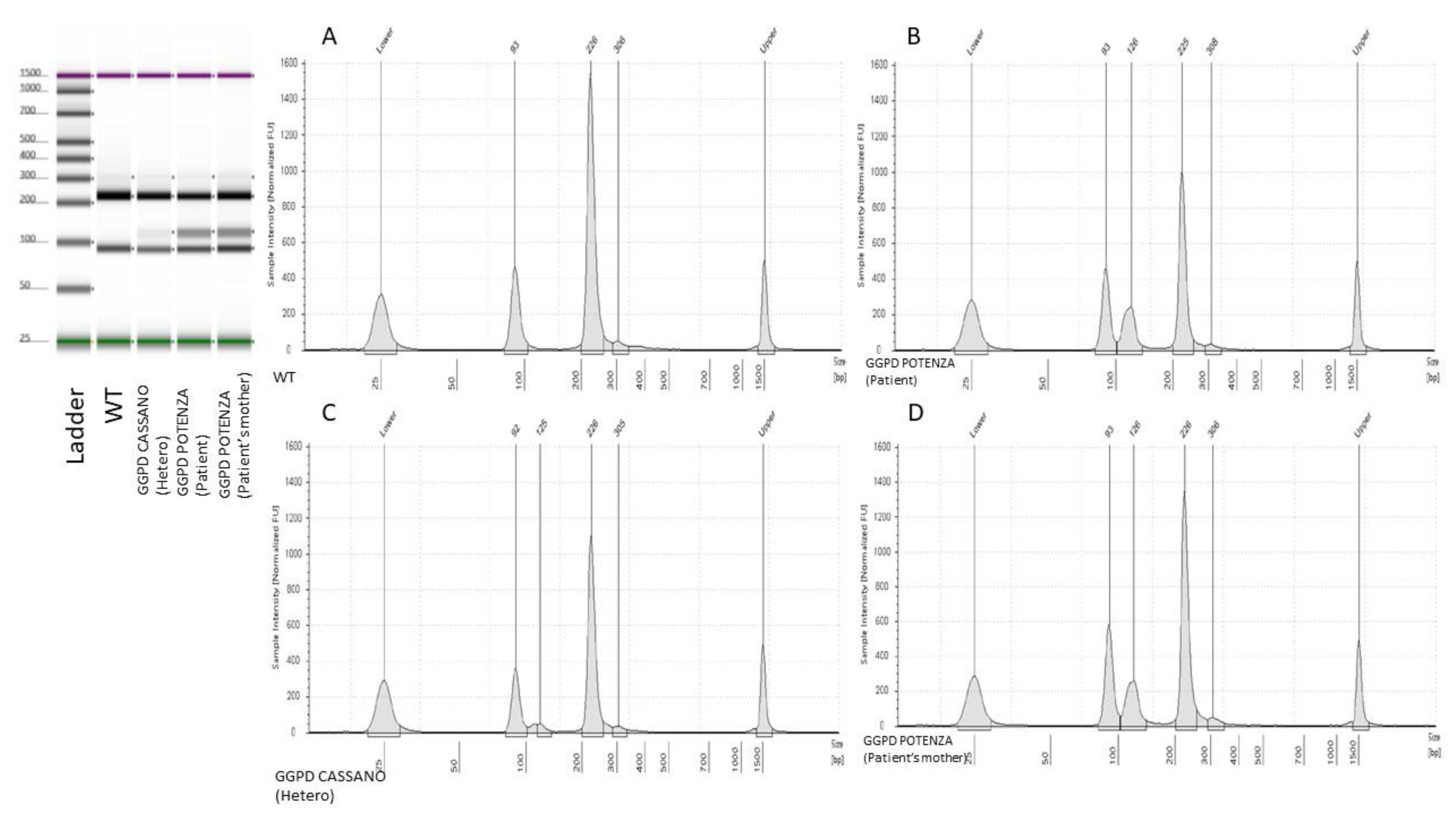

The “first level” molecular analysis was carried out using RFLP techniques, with fragments evaluation performed on agarose gels and via capillary electrophoresis, or targeted Sanger sequencing. In details, for G6PD A-, G6PD Cassano, G6PD Seattle PVs genotyping, we used PCR coupled with RFLP as methodological approach. Instead, PCR and Sanger sequencing were used for G6PD Chatham variant. Additionally, since the G6PD Mediterranean variant is the most frequent among patients addressed to our institution, it was more strategic to analyze it directly with the Sanger sequencing method. Primers used for PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing were previously reported [

14].

Sanger sequencing was carried out for the G6PD Chatam and G6PD Mediterranean variants and for confirmatory screening following a positive or equivocal RFLP. Sequencing reactions were running on the 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and analyzed using the SeqScape™ software 3 (Applied Biosystems) using the Reference Sequence NM_001360016.2.

For the remaining G6PD common mutations, the RFLP protocol was carried out after the first PCR as reported with minor changes [

15]. The digested PCR reactions were analyzed on the agarose gel or using the capillary electrophoretic system Tape Station 4200 (Agilent Technologies) using the High Sensitivity D1000 ScreenTape analysis (Agilent Technologies) and the reagents combined as recommended by the manufacturer.

2.3. In Silico Analysis

The potential effect of the novel

G6PD variant on the enzyme structure/function and the prediction of pathogenicity were evaluated combining different in silico tools from Varsome (

https://varsome.com/).

3. Results

The results obtained from the evaluation of G6PD enzymatic activity and the hematological profile of the patient are described in

Table 1. The patient showed normal, although very close to the lower range, G6PD activity (9.2 U/g Hb; 80% enzymatic activity) and displayed asymptomatic status.

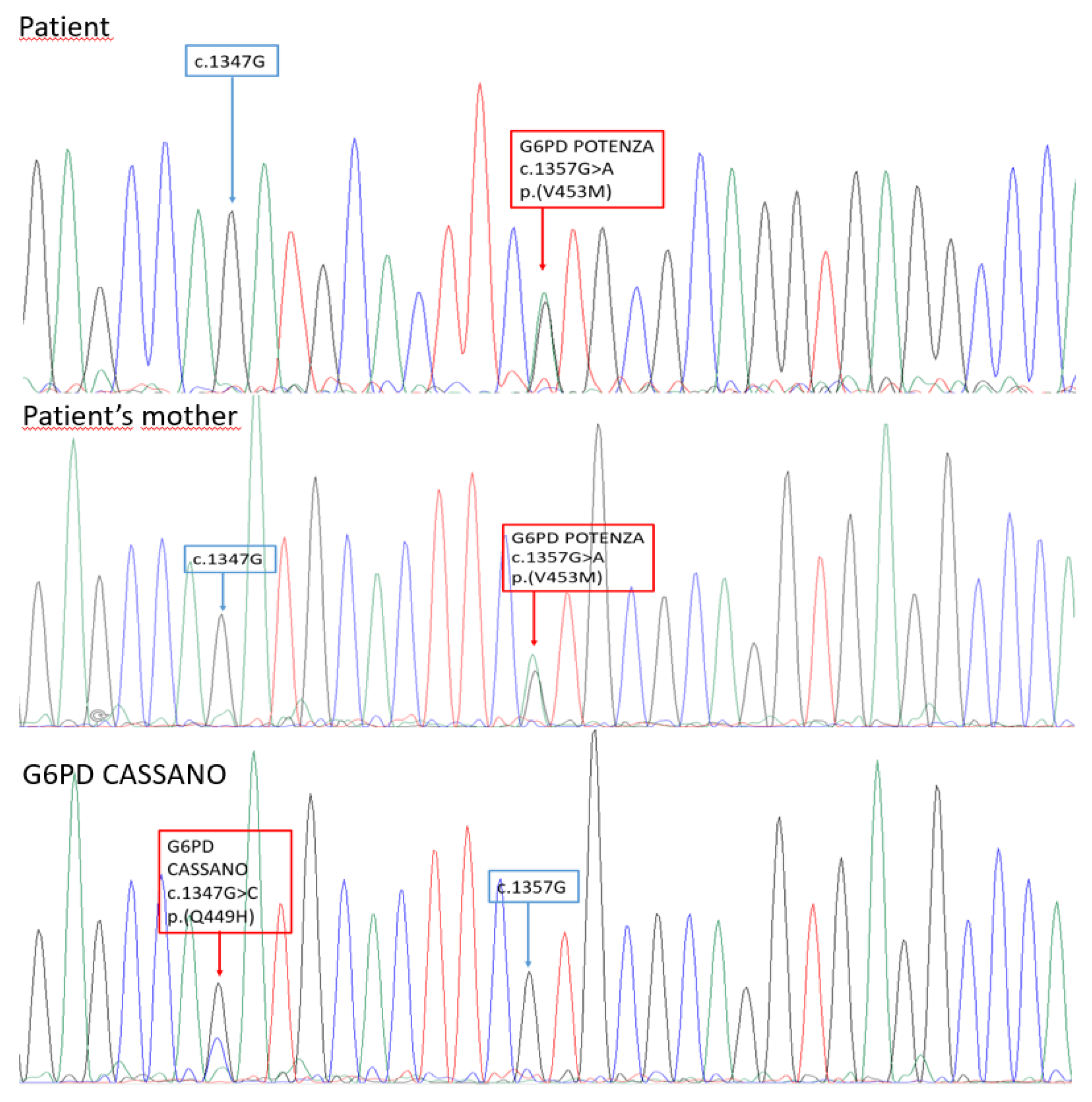

From the genetic analysis of G6PD, emerged a wild type status for the

G6PD Chatham,

G6PD Mediterranean, analyzed by direct sequencing. The same result was obtained via RFLP technique regarding the

G6PD A-, and

G6PD Seattle variants. From RFLP enzymatic digestion of exon 11, associated with the

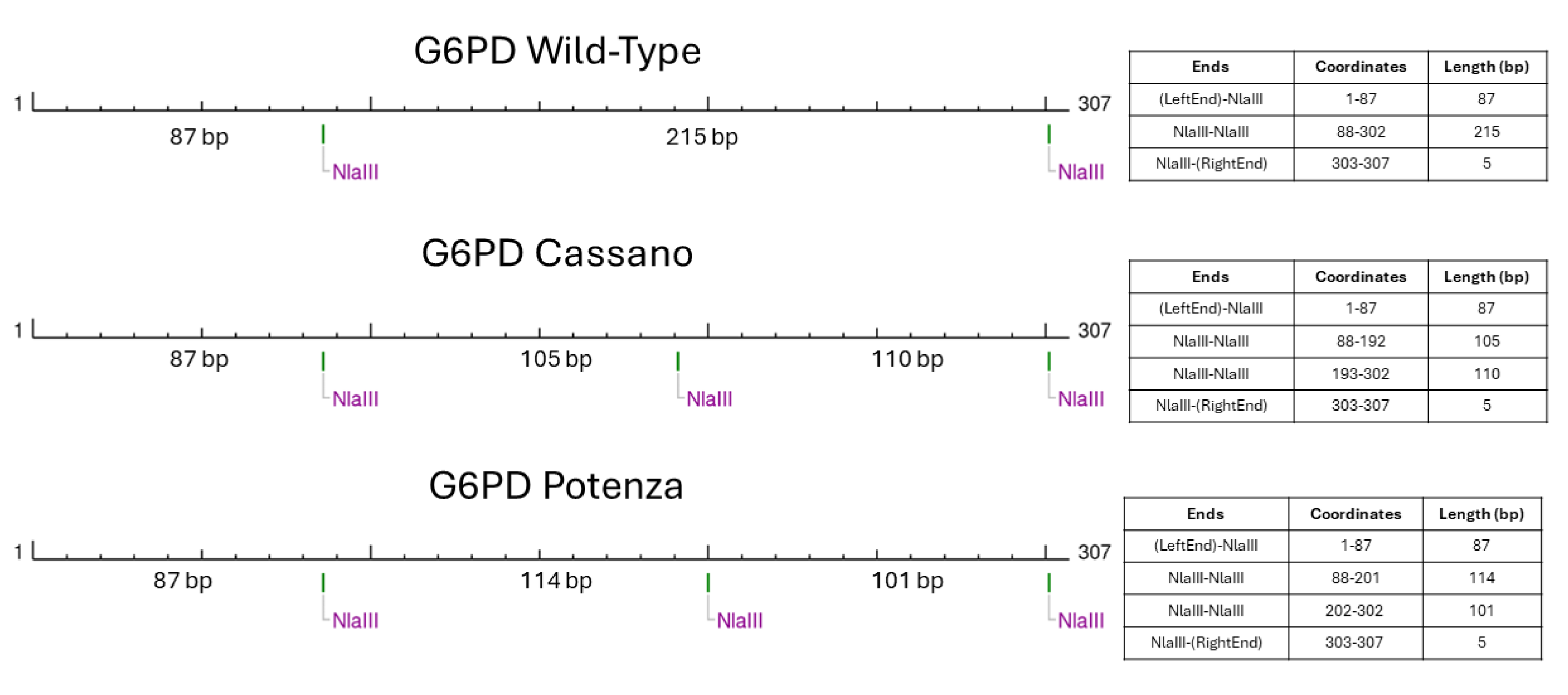

G6PD Cassano variant (

c.1347G>C, p.(Gln449His)), emerged a positive restriction pattern suggestive of the presence of the variant. In particular, the observed restriction pattern showed the presence of three different bands with bp sizes values close to the typical RFLP pattern of

G6PD Cassano. Consequently, the presence of the G6PD Cassano variant was initially hypothesized. The latter positive result obtained by RFLP, as per practice in our laboratory, is was then reconfirmed by Sanger sequencing testing. Unexpectedly, the direct sequencing analysis showed the presence of the heterozygous variant

c.1357G>A (NM_001360016.2). The variant is not found in the databases of the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), 1000 Genomes (

http://www.internationalgenome.org/), Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database (dbSNP), ClinVar (http://

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/) and LOVD (

https://www.lovd. nl/). For these reasons, the variant was considered as novel.

To fully characterized the familiar segregation of the novel variant, G6PD screening was offered to the patient’s mother, father, and brother. The same variant was found in the patien

t’s mother (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

We speculated about the impact of the novel p.(Val453Met) amino acidic change on the enzyme structure using several in silico analysis tool that are overall in accordance about its deleterious effect (

Table 2 ).

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the

c.1357G>A variant was not previously reported in the main mutational databases and in literature. It was decided to name the new variant as

‘‘G6PD Potenza’‘, with regard to the patien

t’s city of birth in Basilicata region. The molecular basis of such unexpected RFLP result consisted in a peculiar restriction patter created by the novel variant (

Figure 3).

In fact, the presence of the G6PD c.1357G>A variant generated restriction sites and fragments with lengths that could be easily overlapped if analyzed with electrophoretic approaches. This observation underlined the key role of Sanger sequencing method that still represent the gold standard confirmatory approach.

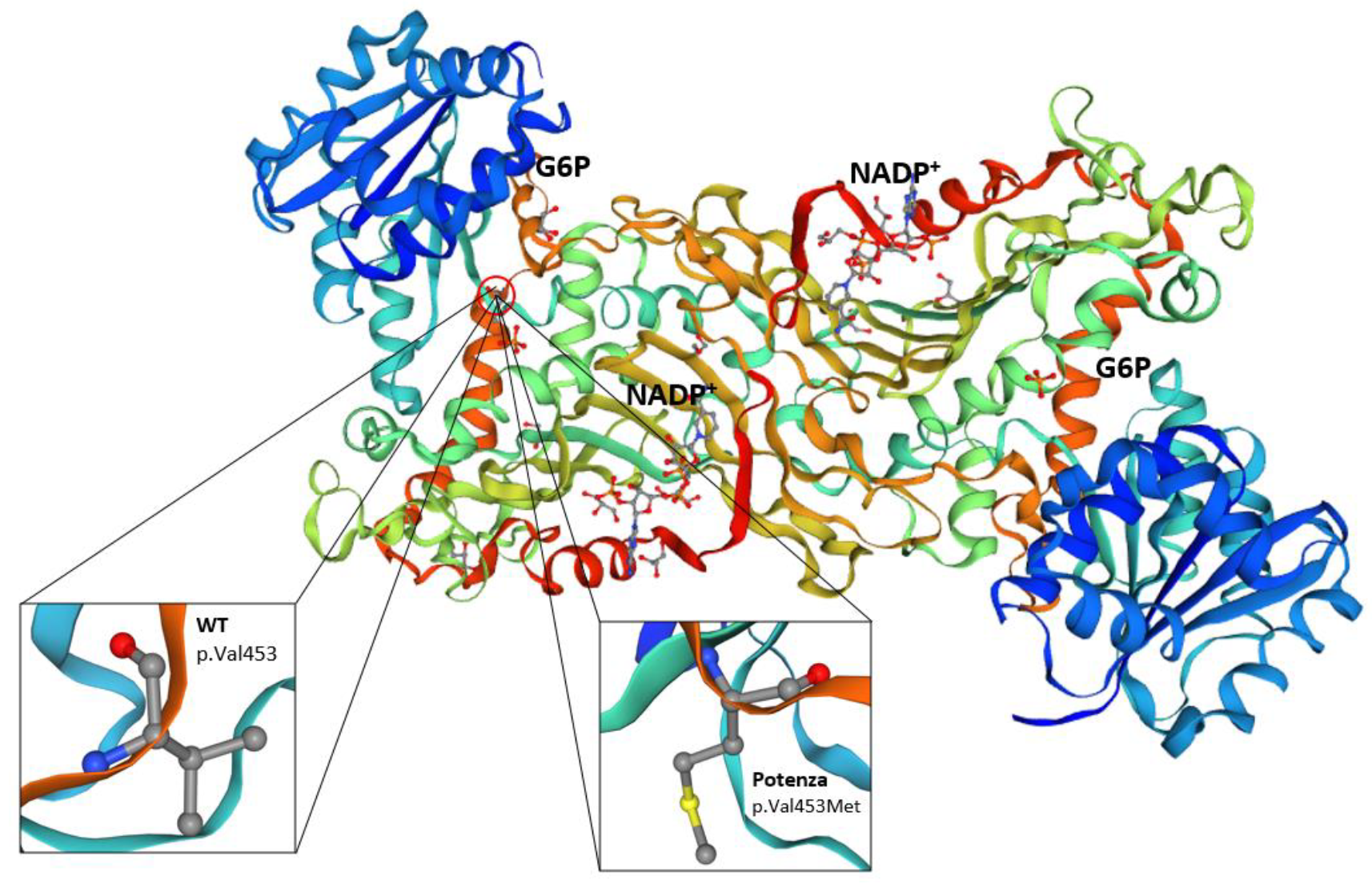

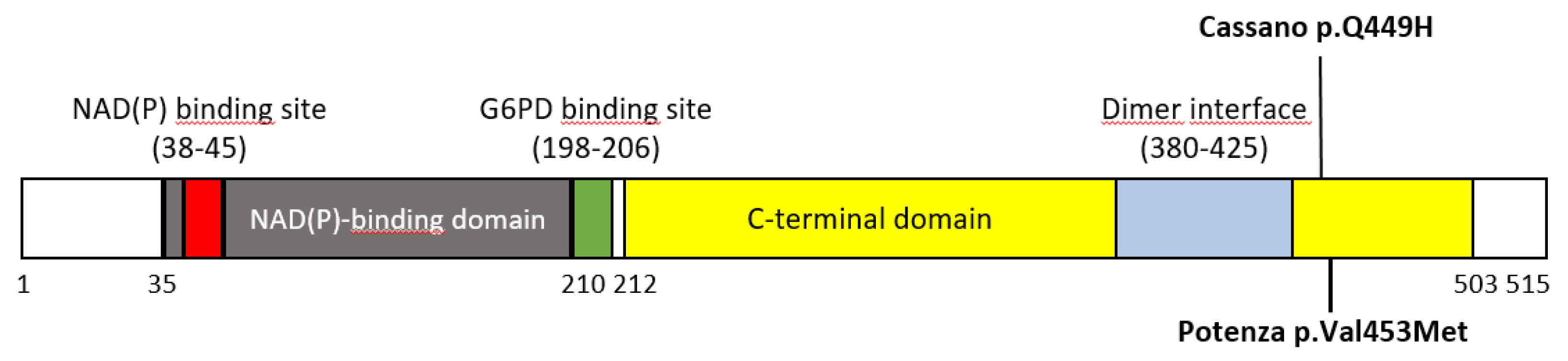

The p.(Val453Met) substitution is located in a region of the G6PD enzyme that is important for maintaining its structural stability and catalytic function. Valine at position 453 is highly conserved across species, suggesting that it plays a critical role in the enzyme function. The replacement by methionine residue could potentially disrupt the enzyme tertiary structure or affect the binding affinity for its substrates and cofactors [

16] (

Figure 4).

The average incidence of G6PD deficiency is 0.4% in the middle of Italy and 1% in Sicily, while it reaches the average value of 14.3% in Sardinia, with a peak of 25.8% in the province of Cagliari. In 1971, Yoshida and colleagues suggested a five-category classification system of G6PD mutations, based on the residual enzymatic activity and the severity of the anemia[

6]. From the five classes, variants of IV and V (the latter was based on a single clinical case) have no clinical manifestations, unlike those of classes I-III. Specifically, the rare class I variants are defined as chronically associated to non-spherocytic hemolytic anemia (CNSHA), while the polymorphic and with higher prevalence variants associated with the development of AHA (Acute Haemolytic anemia) triggered by medicines, broad beans, or infection, were assigned to classes II and III. Novel G6PD variants can be classified mainly according to the enzymatic activity in one or few samples [

13]. The classification of the variants adopted by WHO takes into account the hematological consequences of G6PD deficiency and its degree of deficiency. In particular, the degree of G6PD deficiency is classified as of class II if the residual activity was less than 10% and of class III if greater than 10% [

13]. Following a technical consultation held in January 2022, a revision (approved with minor changes by the WHO Malaria Policy Advisory Group) of the G6PD variant classification was proposed. This proposal was recently published in the WHO Bulletin [

7]. Because CNSHA is a clinically distinct phenotype, all rare variants that cause CNSHA (previously classified as class I), are now classified as class A. In this revision, the previous class II and III were merged into class B. It is important to underline that class B G6PD variants could be considered a triggering factor of a pathological manifestation instead of a disease per se[

13]. Based on the overall data highlighted in this case report, we could put forward a hypothesis of classification of the new c.1357G>A, p.(Val453Met) variant as class B, and formerly class III, given the absence of pathological phenotypic or clinical manifestations and the enzymatic activity of 80%.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we describe the occurrence of the novel

G6PD variant

c.1357G>A, p.(Val453Met) in an Italian woman without any clinical symptoms. This case also highlights how the Sanger sequencing technique still represents an indispensable standard method for the final confirmation of germline variants that could be mis-interpreted by using rapid approach as the RFLP. The main limit of the study is the lack of functional assays measuring the activity of the

G6PD p.(Val453Met) enzyme compared to the wild-type, that are considered crucial for determining the variant impact. The observation of a significant reduction in enzyme activity in vitro would support the hypothesis that the variant could be damaging [

16].

Our study confirms the high heterogeneity of the distribution of G6PD variants in Italy, confirming the possibility of identifying novel, rare or local G6PD variants in specific regions.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, A.M., C.R.T. and E.T; methodology, C.R.T, E.T., R.B, A, P. M.D.B., J.E. and C.C; software, G.M..; validation, C.R.T., A.M., A.P., M.R., and A.U.; data curation, E.D.P., M.D.B. and R.B; writing—original draft preparation, C.R.T., E.T., A.M., M.D.B and E.D.P.; writing—review and editing, A.M., A.U., E.T. and C.R.T; supervision, A.M. and A.U.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are included in the manuscript

Acknowledgments

We thank the study’s participants

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nkhoma, E.T.; Poole, C.; Vannappagari, V.; Hall, S.A.; Beutler, E. The Global Prevalence of Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Blood Cells, Mol. Dis. 2009, 42, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Manzo, S.; Marcial-Quino, J.; Vanoye-Carlo, A.; Serrano-Posada, H.; Ortega-Cuellar, D.; González-Valdez, A.; Castillo-Rodríguez, R.A.; Hernández-Ochoa, B.; Sierra-Palacios, E.; Rodríguez-Bustamante, E.; et al. Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase: Update and Analysis of New Mutations around the World. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canu, G.; Mazzuccato, G.; Urbani, A.; Minucci, A. Report of an Italian Family Carrying a Typical Indian Variant of the Nilgiris Tribal Groups Resulting from a de Novo Occurrence. Hum. Genome Var. 2018, 5, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minucci, A.; Antenucci, M.; Giardina, B.; Zuppi, C.; Capoluongo, E. G6PD Murcia, G6PD Ube and G6PD Orissa: Report of Three G6PD Mutations Unusual for Italian Population. Clin. Biochem. 2010, 43, 1180–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minucci, A.; Moradkhani, K.; Hwang, M.J.; Zuppi, C.; Giardina, B.; Capoluongo, E. Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (G6PD) Mutations Database: Review of the “Old” and Update of the New Mutations. Blood Cells, Mol. Dis. 2012, 48, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geck, R.C.; Powell, N.R.; Dunham, M.J. Functional Interpretation, Cataloging, and Analysis of 1,341 Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Variants. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 110, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luzzatto, L.; Bancone, G.; Dugué, P.; Jiang, W.; Minucci, A.; Nannelli, C.; Pfeffer, D.; Prchal, J.; Sirdah, M.; Sodeinde, O.; et al. New WHO Classification of Genetic Variants Causing G6PD Deficiency. Bull. World Health Organ. 2024, 102, 615–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luzzatto, L.; Ally, M.; Notaro, R. Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency. Blood 2021, 136, 1225–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minucci, A.; Giardina, B.; Zuppi, C.; Capoluongo, E. Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Laboratory Assay: How, When, and Why? IUBMB Life 2009, 61, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minucci, A.; Concolino, P.; De Luca, D.; Giardina, B.; Zuppi, C.; Capoluongo, E. A Prolonged Neonatal Jaundice Associated with a Rare G6PD Mutation. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2009, 53, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minucci, A.; Concolino, P.; Antenucci, M.; Santonocito, C.; Ameglio, F.; Zuppi, C.; Giardina, B.; Capoluongo, E. Description of a Novel Missense Mutation of Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Gene Associated with Asymptomatic High Enzyme Deficiency. Clin. Biochem. 2007, 40, 856–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menounos, P.; Zervas, C.; Garinis, G.; Doukas, C.; Kolokithopoulos, D.; Tegos, C.; Patrinos, G.P. Molecular Heterogeneity of the Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency in the Hellenic Population. Hum. Hered. 2000, 50, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nannelli, C.; Bosman, A.; Cunningham, J.; Dugué, P.A.; Luzzatto, L. Genetic Variants Causing G6PD Deficiency: Clinical and Biochemical Data Support New WHO Classification. Br. J. Haematol. 2023, 202, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minucci, A.; Concolino, P.; Vendittelli, F.; Giardina, B.; Zuppi, C.; Capoluongo, E. Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Buenos Aires: A Novel de Novo Missense Mutation Associated with Severe Enzyme Deficiency. Clin. Biochem. 2008, 41, 742–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minucci, A.; Delibato, E.; Castagnola, M.; Concolino, P.; Ameglio, F.; Zuppi, C.; Giardina, B.; Capoluongo, E. Identification of RFLP G6PD Mutations by Using Microcapillary Electrophoretic Chips (Experion). J. Sep. Sci. 2008, 31, 2694–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VarChat Available online: https://varchat.engenome.com/).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).