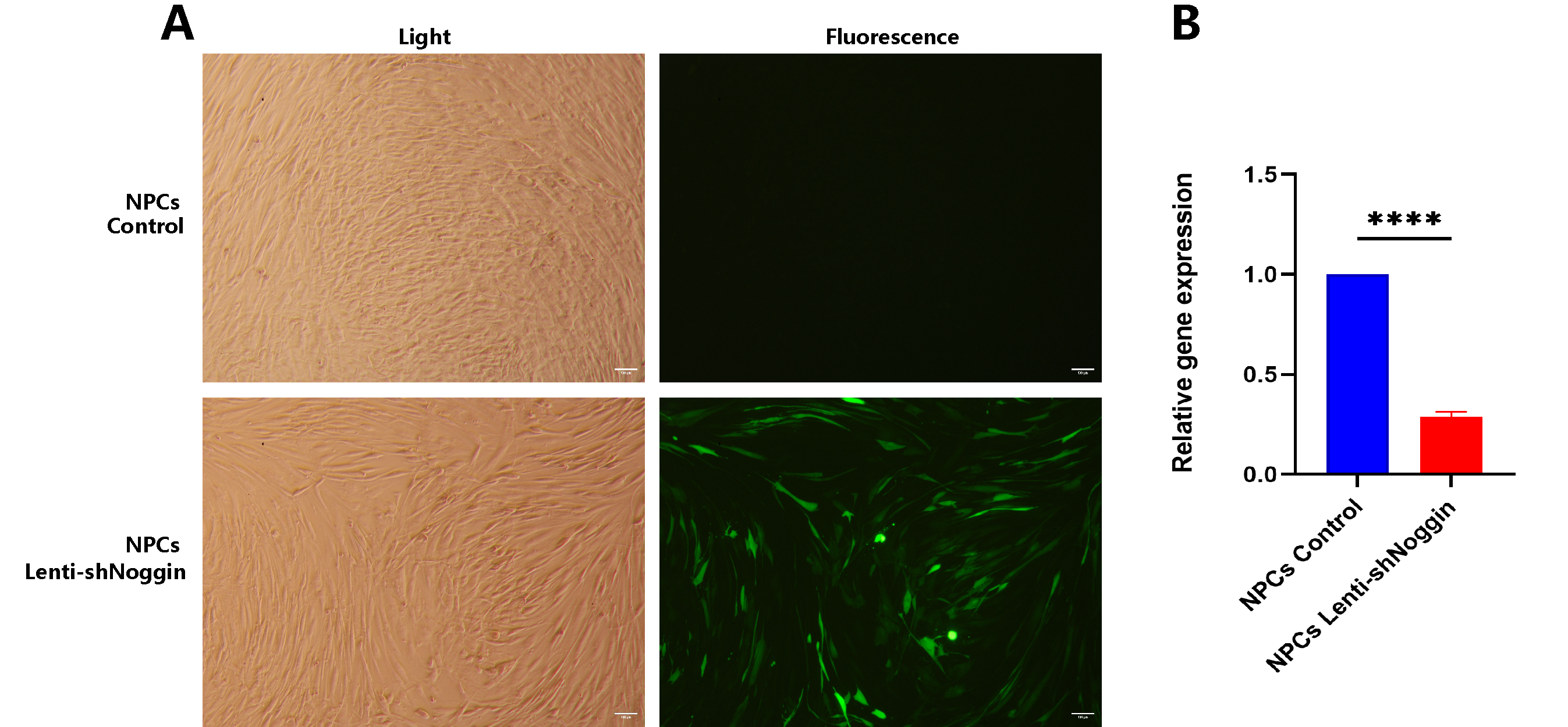

1. Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) represents a significant global health issue [

1], contributing to substantial disability and socioeconomic impact due to its prevalence and the associated healthcare costs [

2,

3]. The degeneration of the human intervertebral disc (IVD) is central to the pathogenesis of LBP [

4,

5]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying IVD degeneration is essential for developing effective therapeutic strategies to alleviate LBP and enhance patient quality of life.

Intervertebral discs are composed of a gelatinous nucleus pulposus (NP) surrounded by a tough annulus fibrosus (AF) [

6,

7,

8]. The NP is crucial for the disc’s ability to absorb shocks and distribute mechanical loads [

9]. Nucleus pulposus cells (NPCs), derived from the NP, play a vital role in maintaining the health and functionality of the IVD by producing extracellular matrix (ECM) components [

10,

11]. Recent studies [

12,

13,

14,

15] have highlighted the significance of various genes and proteins in maintaining IVD health. Among these, Noggin has emerged as a critical factor due to its high expression levels in healthy NPCs observed in our previous research [

16].

Noggin is a well-known antagonist of bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), which are involved in various cellular processes, including proliferation [

17,

18], differentiation [

19,

20], and apoptosis [

21,

22]. By inhibiting BMP signaling, Noggin regulates tissue homeostasis and prevents pathological calcification [

23,

24,

25]. This regulatory function suggests that Noggin is key to maintaining the structural and functional integrity of the IVD. It is hypothesized that Noggin is a critical factor in maintaining IVD health, and its decreased expression in NPCs is linked to IVD degeneration, thereby affecting the development of LBP.

The purpose of this study is to investigate the effects of changes in Noggin expression on human healthy NPCs. By exploring the relationship between Noggin levels and IVD health, we aim to elucidate the molecule involved in disc degeneration and identify potential therapeutic targets for preventing or reversing this process.

2. Results

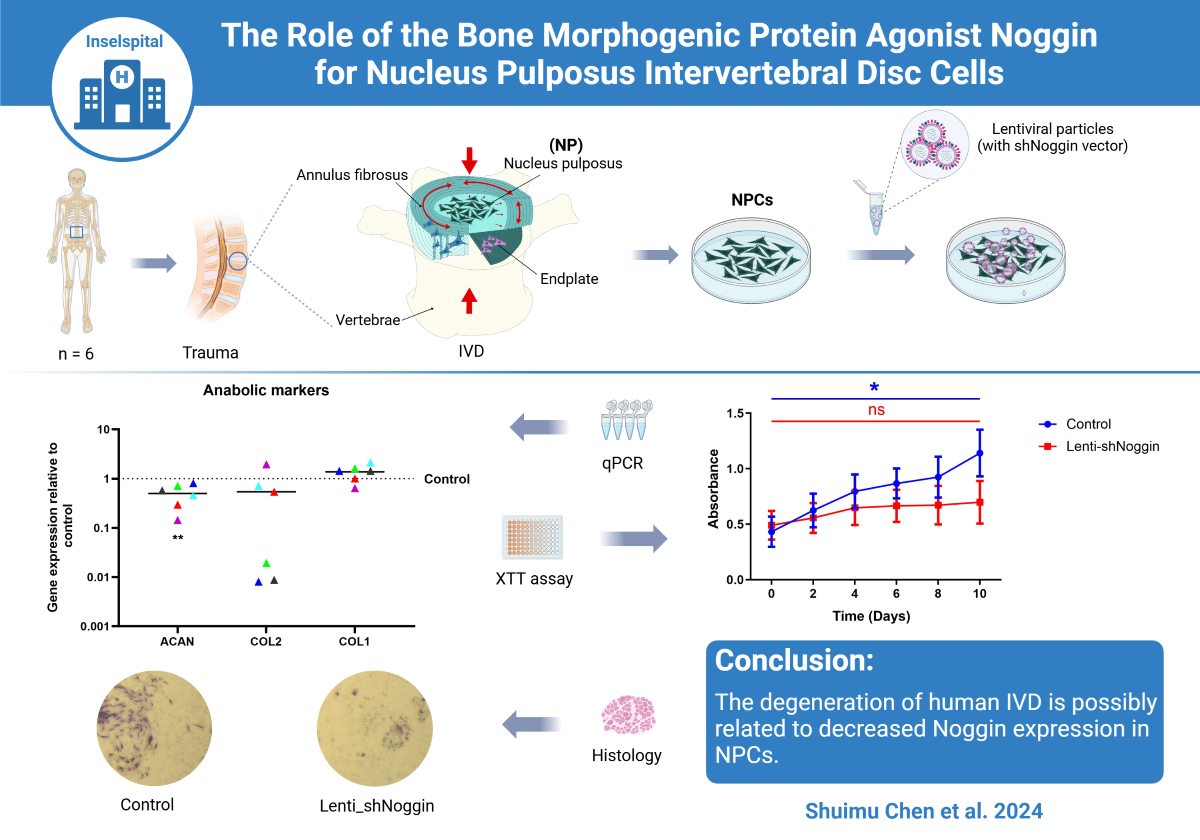

2.1. NPCs Express Elevated Levels of Noggin

To understand the expression differences of Noggin in different cells, we conducted qPCR of human NPCs and donor-matched OBs or MSCs. Subsequently, the relative expression levels of Noggin, one of important BMP antagonists, was quantified. The results showed that the expression of Noggin in NPCs was increased compared to autologous human primary OBs (

Figure 1A), and a similar result compared to MSCs (

Figure 1B). Moreover, the average expression of Noggin in NPCs was 8.379 folds higher than that in autologous OBs (

Figure 1C), and 1.474 folds in MSCs (

Figure 1D). These results revealed that Noggin was highly expressed in human primary NPCs.

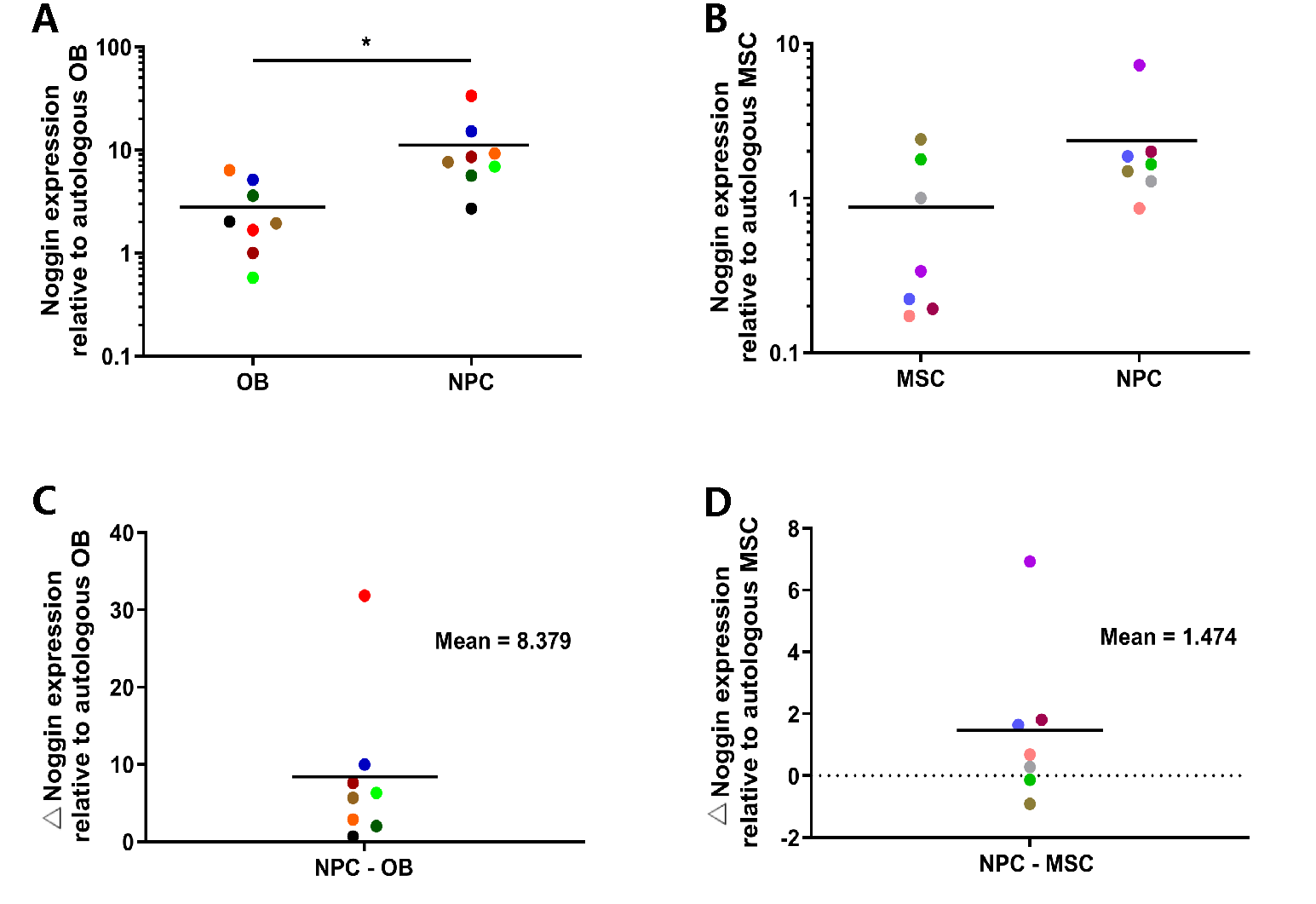

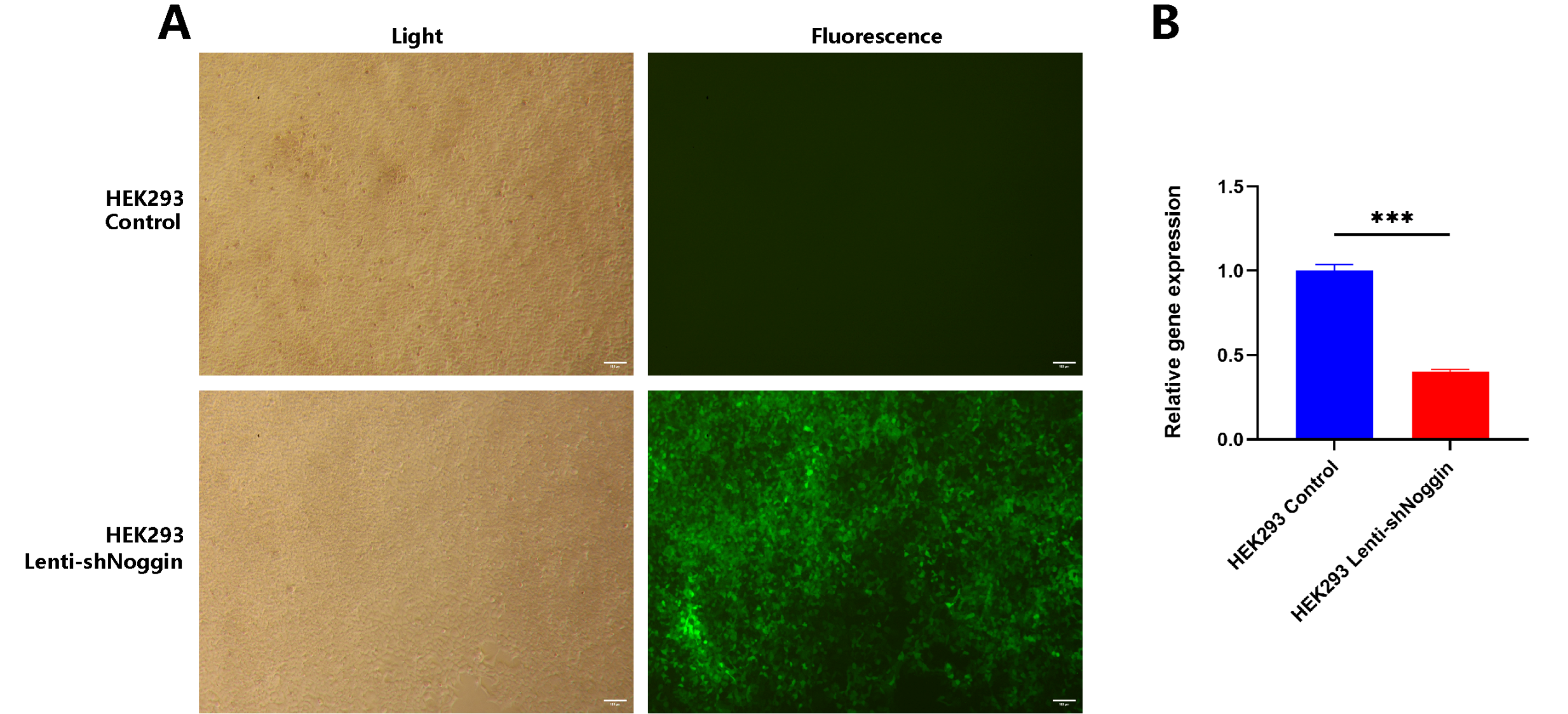

2.2. Noggin in Human Primary NPCs Was Effectively Knocked Down by Lentivirus (Lenti-shNoggin)

We silenced Noggin expression in human primary NPCs via lentiviral transduction (Lenti-shNoggin) by constructing a Noggin-downexpressed vector. Then, HEK293 cells were infected with target lentivirus to confirm its effectiveness (

Figure 2A). It showed Noggin was significantly inhibited after transduction using Lenti-shNoggin (

Figure 2B). Subsequently, we used these lentiviral particles to transduce human primary NPCs (

Figure 3A). A similar result as HEK293 cells, Noggin expression in NPCs was downregulated successfully (

Figure 3B).

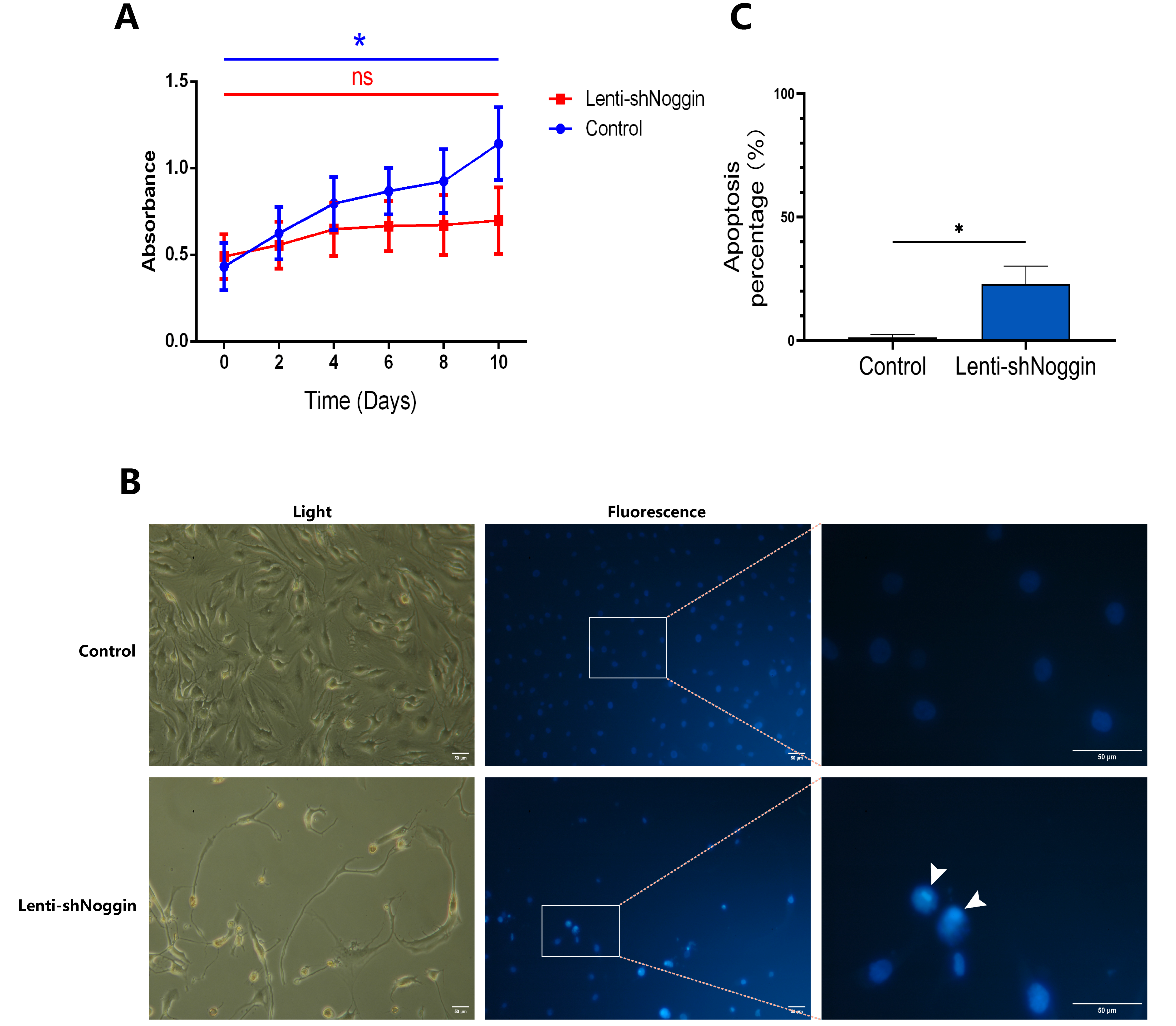

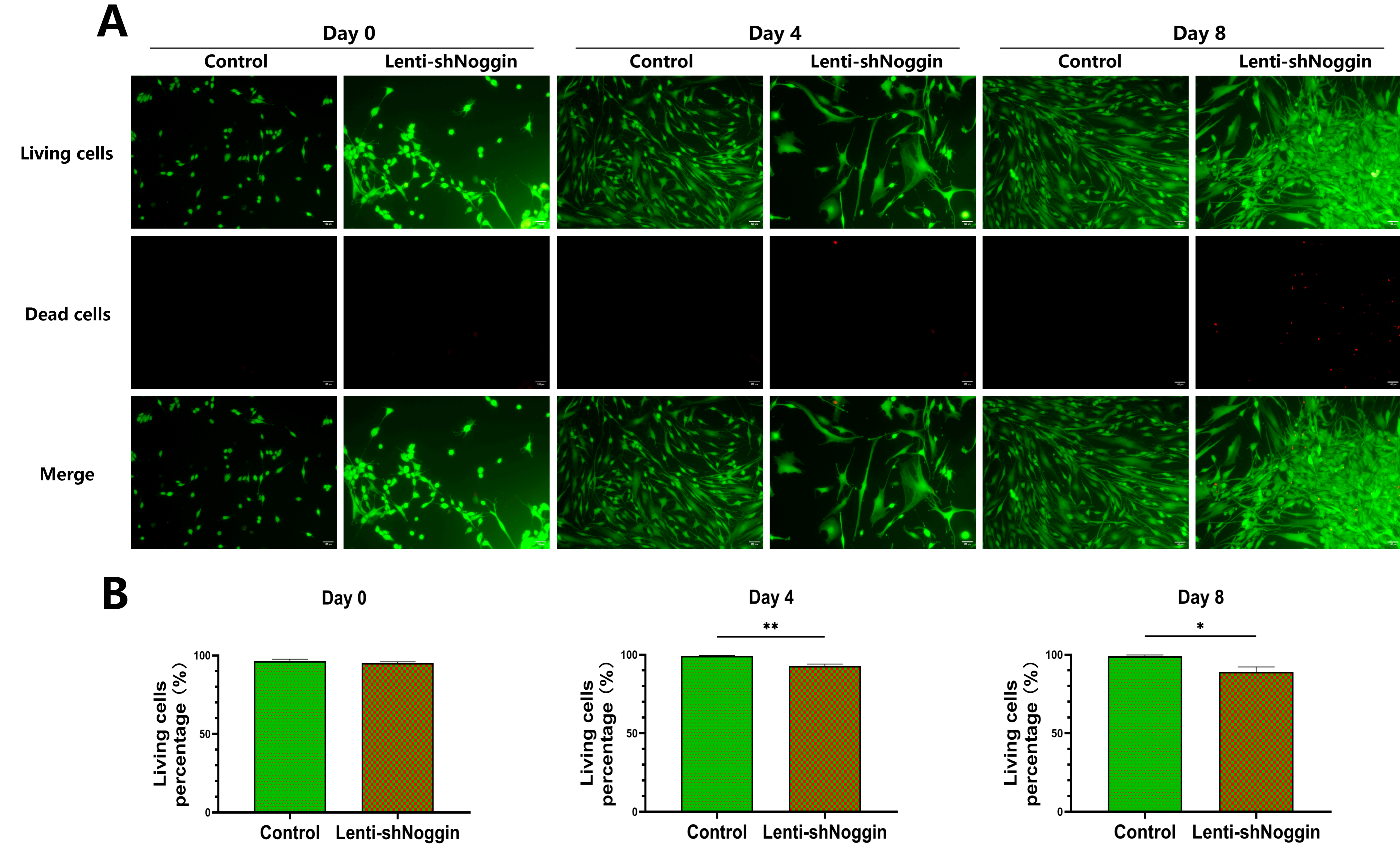

2.3. Silencing Noggin in Human Primary NPCs Inhibited Cell Growth and Induced Apoptosis

To address the possible intrinsic effects of Noggin knockdown on NPCs development, XTT assay was conducted to check the proliferation of human NPCs transduced by Lenti-shNoggin. The results revealed that Noggin knockdown was significantly correlated with proliferation suppression in NPCs (

Figure 4A). After 10 days culture, the NPCs in control group showed active growth compared to Day 0 (p < 0.05), whereas the cells in Lenti-shNoggin group showed slow proliferation rate (p > 0.05). To understand why the activity of NPCs changed after silencing Noggin, we stained the cells with Hoechst 33,258 dye and found that in Lenti-shNoggin group the cells were induced chromatin condensation and nuclear shrinkage or fragmentation, and the apoptosis increased obviously (

Figure 4B). Compared to control group (apoptosis % = 1.337%), the percentage of cell apoptosis in Lenti-shNoggin group reached 22.930% (

Figure 4C). The above-mentioned findings were further supported by the results of the colony formation assay, it indicated that silencing Noggin resulted in a decrease in colony formation ability in vitro (

Figure 5A). There were statistically significant differences in the number of colonies among two groups (p < 0.01,

Figure 5B). These results suggest that Noggin may act as a critical role to maintain homeostasis of NPCs.

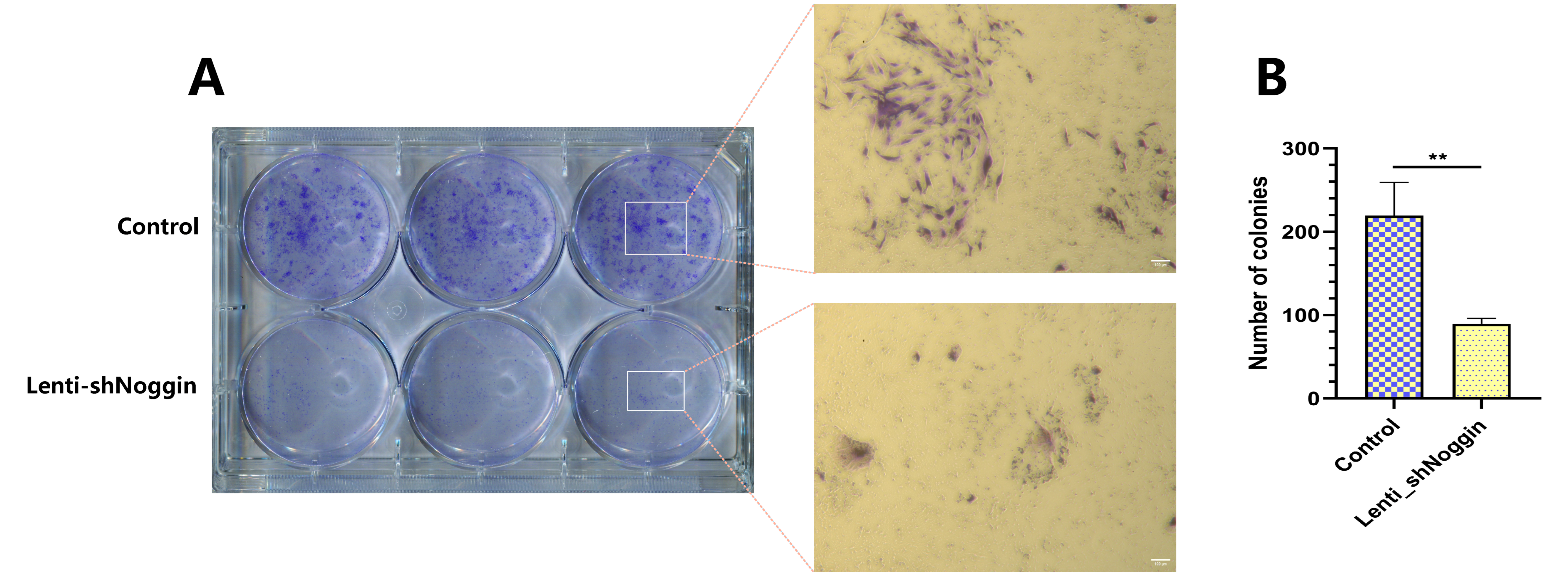

2.4. Inhibition of Noggin Expression Affected the Cell Viability of Human Primary NPCs

To further assess the effect of Noggin inhibition on the survival of NPCs, the cell viability was analyzed. The result showed a correlation between the time and the extent of cell death after transduction. There was not significantly difference between the two groups on Day 0. Generally, the cell death rate in control group was stable over the culture period. However, the NPCs in Lenti-shNoggin group showed an increase in cell death rate over time (

Figure 6A&B. Day 0, 4.75%; Day 4, 7.12%; Day 8, 10.99% in Lenti-shNoggin group). Furthermore, the cell viability was significantly decreased after transduction compared to control group on Day 4 (p = 0.0060) and on Day 8 (p = 0.0363).

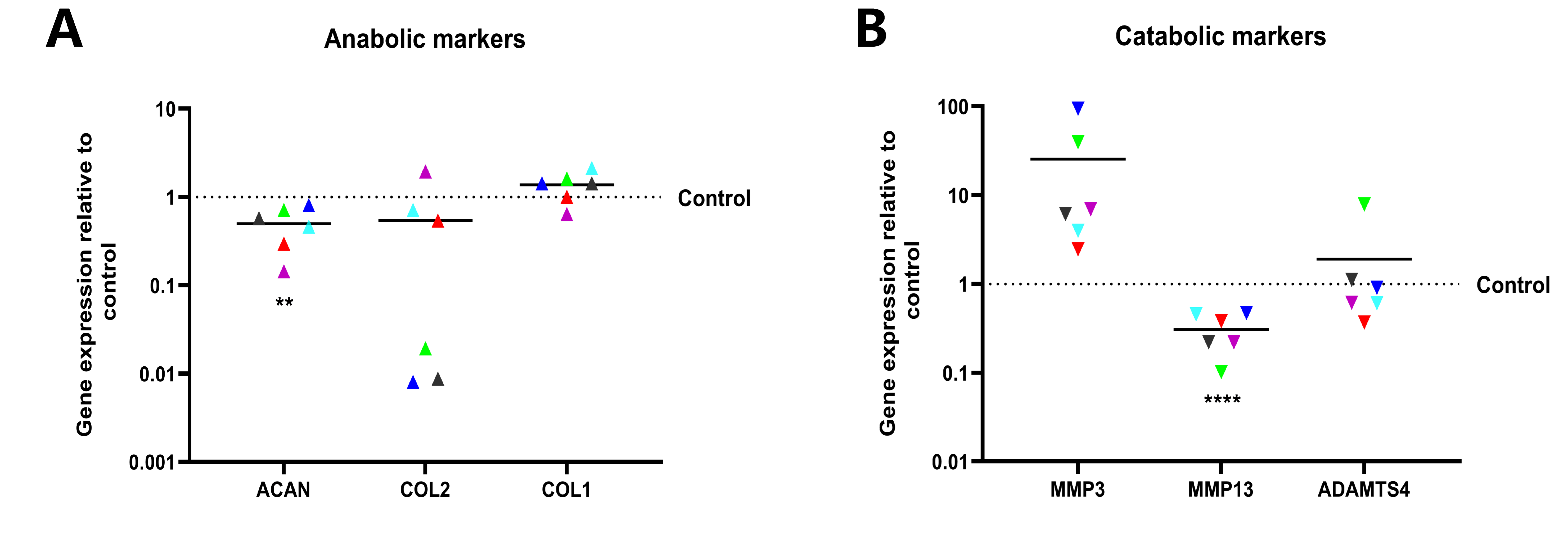

2.5. Knockdown of Noggin in Human NPCs Could Hinder Cellular Anabolism and Enhance Catabolism

To determine the role of Noggin in regulating the metabolism of human NPCs, the makers in cellular anabolism and catabolism of NPCs were quantified at the transcript level by qPCR. ACAN and COL2, markers of NP cells, were downregulated following Noggin knockdown. In contrast, COL1, a fibroblastic marker, was upregulated with Noggin knockdown. These results indicate that Noggin expression is important for maintaining the NPCs phenotype (

Figure 7A). Conversely, downregulated Noggin accelerated the process of catabolism in NPCs. The average expression of MMP3 and ADAMTS4 among measured six donors increased, especially MMP3 (mean = 25.54). Unexpectedly, the expression of MMP13 (mean = 0.3078) was not consistent with the result of other catabolic makers, still the overall catabolic effect was that the increase is greater than the decrease (

Figure 7B).

3. Discussion

The degeneration of the IVD is a pivotal factor in the development of LBP, a significant global health issue [

26]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying IVD degeneration is crucial for developing effective therapeutic strategies.

In this study, we observed that Noggin was highly expressed in healthy intervertebral disc NPCs compared to autologous OBs/MSCs. Previous studies [

16] involving smaller samples of various intervertebral disc-derived cell types have demonstrated similar trends, further illustrating the unique role of Noggin in healthy intervertebral discs. However, it remains unclear whether Noggin is a key factor in the transition from healthy intervertebral discs to intervertebral disc degeneration. To investigate this, we employed lentivirus-mediated knockdown of Noggin expression in human NPCs to explore its impact on NPCs survival.

As a fundamental aspect of cellular biology, cell growth refers to the increase in cell size and number [

27]. In the context of NPCs within the IVD, maintaining robust cell growth is crucial for the health and functionality of the IVD [

28]. The NP serves as the central gelatinous core of the IVD, providing mechanical support and flexibility to the spine [

29]. NPCs are responsible for producing and maintaining the ECM [

30], a complex network of proteins and polysaccharides essential for the structural integrity of the NP [

31]. Our study demonstrated that lentivirus-mediated downregulation of Noggin in human NPCs significantly suppressed cell growth. Noggin, a known antagonist of BMPs [

32,

33], plays an important role in regulating BMP signaling pathways involved in cellular proliferation and differentiation [

17], contributing to bone formation and regeneration [

34]. By inhibiting BMPs, Noggin ensures the proper balance of cellular activities necessary for tissue homeostasis [

35]. Interestingly, the suppression of cell growth observed in our study suggests that Noggin is vital for maintaining the proliferative capacity of NPCs, which is essential for the continuous renewal and repair of the NP.

Our study also highlighted the role of Noggin in regulating apoptosis in NPCs. The lentivirus-mediated knockdown of Noggin induced significant apoptosis in NPCs, as evidenced by apoptosis staining assay. This result was consistent with the slow cell growth in Lenti-shNoggin group to a certain extent. Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, is a tightly regulated process that eliminates damaged or dysfunctional cells [

36]. However, excessive apoptosis can lead to tissue degeneration and loss of cellular function [

37,

38]. Studies [

39,

40] have shown that BMP-2 can induce apoptosis in various cell types, including mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). By antagonizing BMPs, Noggin may help maintain cell viability by preventing apoptosis. Our results suggest that reduced Noggin expression removes this protective effect, rendering NPCs more susceptible to apoptotic signals and decreasing cell growth.

Generally, as apoptosis continues, cell death also increases [

36]. In Live/Dead staining, we found that the death rate of transduced NPCs at Day 4 and Day 8 was significantly higher than that of the control group. In addition to the effect from increased apoptosis, the reduced viability of NPCs may be also related to the disrupted balance between anabolic and catabolic activities observed in our study. qPCR analysis revealed significant alterations in the expression levels of genes associated with these metabolic processes. The downregulation of Noggin hindered anabolic processes while enhancing catabolic activity in NPCs. This disruption in cellular metabolism likely contributes to the degeneration of the IVD, as the balance between anabolic and catabolic activities is essential for maintaining extracellular matrix integrity and overall disc health. The observed increase in apoptosis further supports the notion that reduced Noggin expression leads to detrimental cellular outcomes.

Colony formation assay is a widely used method for assessing the clonogenic potential and proliferative capacity of cells [

41]. This assay measures the ability of a single cell to grow into a colony, reflecting the cell’s ability to undergo multiple rounds of division and proliferation [

42]. In our study, the downregulation of Noggin in NPCs significantly decreased colony formation, indicating a diminished proliferative capacity. The decreased colony formation can be associated with the increased apoptosis observed in our study. Apoptosis reduces the number of viable cells available to form colonies, directly impacting the clonogenic potential of NPCs. Moreover, the enhanced catabolic activity observed upon Noggin downregulation may also contribute to reduced colony formation by degrading ECM components necessary for cell attachment and growth [

43]. Studies [

44,

45] have shown that ECM integrity is critical for supporting cell proliferation and colony formation. The disrupted balance between anabolic and catabolic activities in NPCs with reduced Noggin expression likely creates a less favorable microenvironment for colony formation.

Despite the promising findings, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The use of in vitro models, while valuable for controlled mechanistic studies, may not fully replicate the complex environment of the human IVD in vivo. The effects of Noggin knockdown observed in cultured NPCs may differ from those in a living organism, where multiple cell types and systemic factors interact. Furthermore, the study focused on primary NPCs from a limited number of donors, which may not capture the full variability in Noggin expression and function across different individuals.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Human Materials and Cell Isolation

Multiple specimens, including bone fragments, intervertebral disc tissues and human bone marrow aspirates, were obtained from patients undergoing spinal surgery at the Insel University Hospital with their written consent. Six donors derived NPCs were used for transduction and ten donors for comparison of Noggin expression between NPCs and autologous mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)/osteoblasts (OBs) (

Table 1 and

Table 2). All donor tissues and cells were collected anonymously and with written consent. Approvals were under the Insel University Hospital’s general consent, including anonymizing biological material and health-related data. The injured vertebral body bone fragments were cut into smaller pieces, 3–5 mm in diameter. The pieces were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) before being transferred to T75 flasks for culturing in alpha minimum essential medium (α-MEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S, Sigma-Aldrich, Inc, Buchs, Switzerland). Primary OBs were expanded via the active outgrowth technique and selected for plastic adherence. The medium was replaced after roughly one week of culture, coinciding with the observation of multiple initial OB populations. IVD tissues were processed within 24 hours following surgery, with the NP being harvested from the IVD tissue, usually in the operating room by a skilled spine surgeon. These tissues were then sequentially digested using 1.9 mg/ml pronase (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) for an hour, followed by collagenase II (64 U/ml; Worthington, London, UK) on a plate shaker at 37°C overnight. To remove residual fragments, the digested tissue mixture was filtered through a 100μm cell strainer (Falcon, Becton Dickinson, Allschwil, Switzerland). The obtained NPCs were cultured in low-glucose (1 g/L) Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (LG-DMEM, Gibco, Life Technologies, Zug, Switzerland) containing 10% FBS and 1% P/S. MSCs were isolated from bone marrow samples aspirated from vertebrae during spinal surgery (5-10 mL) using gradient centrifugation (Histopaque-1077, Sigma-Aldrich) [

46]. These MSCs were subsequently expanded in α-MEM (from Sigma-Aldrich) with 10% FBS, 1% P/S and 2.5 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor 2 (bFGF2, Peprotech, London, UK) [

47].

4.2. Target Cells Transduction

To generate Noggin knockdown NPCs, lentiviral vector particles with shRNA targeting Noggin were used to transduce primary NPCs (Noggin shRNA plasmid, with GFP, OriGene Technologies, Inc, Rockville, United States; and the shRNA sequences are listed in

Table 3). Lentiviral vector particles were produced by co-transfection of the vector construct and packaging constructs pMDLg/pRRE, pRSV-Rev and pCMV-VSV-G in 293T cells with lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), as previously described [

48]. Then the collected virus particles were used for transduction of primary NPCs.

4.3. Cell Proliferation Assay

NPCs from two groups were seeded into 96-well plates (2,000 cells/well) and was assessed using a Reagent kit for the quantification of cell proliferation (TACS® XTT, R&D Systems, Inc. Minneapolis, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At day 0, 4, 8 of the culture, cells were incubated with the XTT mixture for 3 h at 37°C. Subsequently, absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (SpectraMax M5, Bucher Biotec, Basel, Switzerland).

4.4. Apoptosis Analysis

Hoechst 33,258 (from Sigma-Aldrich) was utilized to detect the apoptosis in human NPCs after transduction [

49,

50]. Cells were seeded into 6-well plates (3,000 cells/well) and cultured for five days. Subsequently, the medium of all wells was removed and 2ml 1× PBS with a final concentration of 10μg/ml Hoechst 33,258 was added inside. Finally, they were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min before microscopic images were taken.

4.5. Live/Dead Staining

To assess the cell viability, NPCs from each group were seeded into 24-well plates (8000 cells/well) and cell viability was checked at day 0, 4, 8. Briefly, NPCs were immersed into serum-free medium containing 5 µM calcein-AM (#17783-1MG; Sigma-Aldrich) to stain the living cells and 1 µM ethidium homodimer (#46043-1MG-F; Sigma-Aldrich) to stain the dead cells and incubated at 37 °C. After 30 min of incubation, images were taken under a fluorescence microscopy. Finally, the living and dead cells were quantified using a custom-made macro for ImageJ software version 1.52 [

51].

4.6. Colony Formation Assay

Cell suspensions (2,000 cells/well) were seeded into a 6-well plate and cultured in a cell culture incubator. After 2 weeks, the cell colonies were washed three times with 1× PBS. The colonies were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes and stained with 0.2% crystal violet (Millipore, Boston, United States) for 30 minutes. Colonies in each group were subsequently counted.

4.7. RNA Extraction and Relative Gene Expression by qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from human NPCs of both groups, evaluating anabolic and catabolic marker genes expression after transduction, including aggrecan core protein (ACAN), collagen 1 (COL1), collagen 2 (COL2), matrix metalloproteinase 3 (MMP3), matrix metalloproteinase 13 (MMP13), ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif 4 (ADAMTS4). The relative gene expression was normalized to the control group. Cells from the same donor were collected for RNA extraction to compare the expression of Noggin between human OBs/MSCs and NPCs, and the result in NPCs was compared with the control (OBs/MSCs). RNA isolated from the samples was converted into cDNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (#4368814; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cDNA was then mixed with iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (#1725122; Bio-Rad) and human-specific oligonucleotide primers listed in

Table 4. Subsequently, quantitative PCR analysis was performed using the CFX96™ Real-Time System (#185-5096; Bio-Rad Laboratory). Relative gene expression was analyzed via the 2

-ΔΔCt method [

52], with GAPDH serving as the reference gene.

4.8. Statistics

The statistical evaluation was performed by Student’s t-test between two groups and one-way ANOVA for three or more groups. The analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 10 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) software and a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All experiments were performed in triplicates. n = number of biological replicates is indicated in all graphs.

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that low expression of Noggin in human NPCs inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis. Suppression of Noggin results in the downregulation of anabolic processes and upregulation of catabolic processes in NPCs. These findings suggest that decreased expression of Noggin is potentially linked to the degeneration of human IVD. The research provides valuable insights into the role of Noggin in IVD homeostasis, highlighting its significance in maintaining disc health. Understanding Noggin’s function could inform the development of targeted therapies for preventing or treating LBP, thereby contributing to improved patient outcomes and quality of life.

Author Contributions

S.C. and B.G. conceived and designed the experiments; S.C. performed the experiments and partly received technical guidance from X.M. and X.N.; S.C., B.G. and Z.L. analyzed the data; S.B. and S.H. contributed donor tissue; S.C. and B.G. wrote the manuscript; C.R. provided research support and revised the manuscript. B.G. provided funding. S.C. created the graphic arts. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

S.C. was supported by a China Scholarship Council #202208170027. S.H. was supported by a grant of the Swiss Orthopedic Society (SGOT).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The used human tissues and cells in this study were approved and under the general ethical consent of the Insel University Hospital of Bern.

Informed Consent Statement

All human donors have given written consent to this study.

Data Availability Statement

All the data used in this research are available at the request of the first and corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate our colleagues’ valuable suggestions and technical assistance for this study, especially Paola Bermudez’s help in graphics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Knezevic, N.N.; Candido, K.D.; Vlaeyen, J.W.S.; Van Zundert, J.; Cohen, S.P. Low back pain. Lancet 2021, 398, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Lancet, R. The global epidemic of low back pain. Lancet Rheumatol 2023, 5, e305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieleman, J.L.; Cao, J.; Chapin, A.; Chen, C.; Li, Z.; Liu, A.; Horst, C.; Kaldjian, A.; Matyasz, T.; Scott, K.W.; et al. US Health Care Spending by Payer and Health Condition, 1996-2016. JAMA 2020, 323, 863–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zehra, U.; Tryfonidou, M.; Iatridis, J.C.; Illien-Jünger, S.; Mwale, F.; Samartzis, D. Mechanisms and clinical implications of intervertebral disc calcification. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2022, 18, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Glaeser, J.D.; Kaneda, G.; Sheyn, J.; Wechsler, J.T.; Stephan, S.; Salehi, K.; Chan, J.L.; Tawackoli, W.; Avalos, P.; et al. Intervertebral disc human nucleus pulposus cells associated with back pain trigger neurite outgrowth in vitro and pain behaviors in rats. Sci Transl Med 2023, 15, eadg7020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, N.; Lively, S.; Séguin, C.A.; Perruccio, A.V.; Kapoor, M.; Rampersaud, R. Intervertebral disc degeneration and osteoarthritis: A common molecular disease spectrum. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2023, 19, 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novais, E.J.; Tran, V.A.; Johnston, S.N.; Darris, K.R.; Roupas, A.J.; Sessions, G.A.; Shapiro, I.M.; Diekman, B.O.; Risbud, M.V. Long-term treatment with senolytic drugs Dasatinib and Quercetin ameliorates age-dependent intervertebral disc degeneration in mice. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 5213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Liao, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhong, D.; Qiu, X.; Chen, T.; Su, D.; Ke, X.; et al. Self-amplifying loop of NF-κB and periostin initiated by PIEZO1 accelerates mechano-induced senescence of nucleus pulposus cells and intervertebral disc degeneration. Mol Ther 2022, 30, 3241–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Isa, I.L.; Teoh, S.L.; Mohd Nor, N.H.; Mokhtar, S.A. Discogenic Low Back Pain: Anatomy, Pathophysiology and Treatments of Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Wang, Z.; Cui, M.; Liu, S.; Wu, W.; Chen, M.; Wu, Y.; Qu, Y.; Lin, H.; Chen, S.; et al. HIF1A Alleviates compression-induced apoptosis of nucleus pulposus derived stem cells via upregulating autophagy. Autophagy 2021, 17, 3338–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Fan, L.; Guan, M.; Zheng, Q.; Jin, J.; Kang, X.; Gao, Z.; Deng, X.; Shen, Y.; Chu, G.; et al. A Redox Homeostasis Modulatory Hydrogel with GLRX3+ Extracellular Vesicles Attenuates Disc Degeneration by Suppressing Nucleus Pulposus Cell Senescence. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 13441–13460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Lei, L.; Li, Z.; Chen, F.; Huang, Y.; Jiang, G.; Guo, X.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; et al. Grem1 accelerates nucleus pulposus cell apoptosis and intervertebral disc degeneration by inhibiting TGF-β-mediated Smad2/3 phosphorylation. Exp Mol Med 2022, 54, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, A.; Ziadlou, R.; Lang, G.; Pfannkuche, J.; Cui, S.; Li, Z.; Richards, R.G.; Alini, M.; Grad, S. Small molecule-based treatment approaches for intervertebral disc degeneration: Current options and future directions. Theranostics 2021, 11, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, E.J.; Darai, A.; Kyung, J.W.; Choi, H.; Kwon, S.Y.; Bhujel, B.; Kim, K.T.; Han, I. Genetic Therapy for Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, R.D.; Frauchiger, D.A.; Albers, C.E.; Tekari, A.; Benneker, L.M.; Klenke, F.M.; Hofstetter, W.; Gantenbein, B. Application of Cytokines of the Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) Family in Spinal Fusion - Effects on the Bone, Intervertebral Disc and Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Current Stem Cell Research & Therapy 2019, 14, 618–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Croft, A.S.; Bigdon, S.; Albers, C.E.; Li, Z.; Gantenbein, B. Conditioned Medium of Intervertebral Disc Cells Inhibits Osteo-Genesis on Autologous Bone-Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells and Osteoblasts. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yung, L.-M.; Yang, P.; Joshi, S.; Augur, Z.M.; Kim, S.S.J.; Bocobo, G.A.; Dinter, T.; Troncone, L.; Chen, P.-S.; McNeil, M.E.; et al. ACTRIIA-Fc rebalances activin/GDF versus BMP signaling in pulmonary hypertension. Sci Transl Med 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lozano, M.-L.; Sudre, L.; van Eegher, S.; Citadelle, D.; Pigenet, A.; Lafage-Proust, M.-H.; Pastoureau, P.; De Ceuninck, F.; Berenbaum, F.; Houard, X. Gremlin-1 and BMP-4 Overexpressed in Osteoarthritis Drive an Osteochondral-Remodeling Program in Osteoblasts and Hypertrophic Chondrocytes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaz, A.; Jayasuriya, A.C. Osteogenic differentiation cues of the bone morphogenetic protein-9 (BMP-9) and its recent advances in bone tissue regeneration. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2021, 120, 111748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murase, Y.; Yokogawa, R.; Yabuta, Y.; Nagano, M.; Katou, Y.; Mizuyama, M.; Kitamura, A.; Puangsricharoen, P.; Yamashiro, C.; Hu, B.; et al. In vitro reconstitution of epigenetic reprogramming in the human germ line. Nature 2024, 631, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukač, N.; Katavić, V.; Novak, S.; Šućur, A.; Filipović, M.; Kalajzić, I.; Grčević, D.; Kovačić, N. What do we know about bone morphogenetic proteins and osteochondroprogenitors in inflammatory conditions? Bone 2020, 137, 115403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, S.; Kondo, J.; Onuma, K.; Coppo, R.; Ota, K.; Kamada, M.; Harada, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Nakazawa, M.A.; Tamada, Y.; et al. Inhibition of the bone morphogenetic protein pathway suppresses tumor growth through downregulation of epidermal growth factor receptor in MEK/ERK-dependent colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci 2023, 114, 3636–3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-N.; Yu, F.-J.; Chang, Y.-H.; Huang, K.-L.; Pham, N.N.; Truong, V.A.; Lin, M.-W.; Kieu Nguyen, N.T.; Hwang, S.-M.; Hu, Y.-C. CRISPR interference-mediated noggin knockdown promotes BMP2-induced osteogenesis and calvarial bone healing. Biomaterials 2020, 252, 120094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerneni, S.S.; Adamik, J.; Weiss, L.E.; Campbell, P.G. Cell trafficking and regulation of osteoblastogenesis by extracellular vesicle associated bone morphogenetic protein 2. J Extracell Vesicles 2021, 10, e12155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Zhang, X.; Kang, M.; Lee, C.-S.; Kim, L.; Hadaya, D.; Aghaloo, T.L.; Lee, M. Complementary modulation of BMP signaling improves bone healing efficiency. Biomaterials 2023, 302, 122335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashin, A.G.; Folly, T.; Bagg, M.K.; Wewege, M.A.; Jones, M.D.; Ferraro, M.C.; Leake, H.B.; Rizzo, R.R.N.; Schabrun, S.M.; Gustin, S.M.; et al. Efficacy, acceptability, and safety of muscle relaxants for adults with non-specific low back pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2021, 374, n1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Micco, R.; Krizhanovsky, V.; Baker, D.; d’Adda di Fagagna, F. Cellular senescence in ageing: From mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021, 22, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilotta, V.; Vadalà, G.; Ambrosio, L.; Di Giacomo, G.; Cicione, C.; Russo, F.; Darinskas, A.; Papalia, R.; Denaro, V. Wharton’s Jelly mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles promote nucleus pulposus cell anabolism in an in vitro 3D alginate-bead culture model. JOR Spine 2024, 7, e1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordechai, H.S.; Aharonov, A.; Sharon, S.E.; Bonshtein, I.; Simon, C.; Sivan, S.S.; Sharabi, M. Toward a mechanically biocompatible intervertebral disc: Engineering of combined biomimetic annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus analogs. J Biomed Mater Res A 2023, 111, 618–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Wu, O.; Chen, Q.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, H.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, K.; Gao, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Hypoxia-Preconditioned BMSC-Derived Exosomes Induce Mitophagy via the BNIP3-ANAX2 Axis to Alleviate Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2024, e2404275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Jiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhu, J.; Xu, X.; Sun, J.; Shi, J. The role of nerve fibers and their neurotransmitters in regulating intervertebral disc degeneration. Ageing Res Rev 2022, 81, 101733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartori, R.; Hagg, A.; Zampieri, S.; Armani, A.; Winbanks, C.E.; Viana, L.R.; Haidar, M.; Watt, K.I.; Qian, H.; Pezzini, C.; et al. Perturbed BMP signaling and denervation promote muscle wasting in cancer cachexia. Sci Transl Med 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóth, F.; Gáll, J.M.; Tőzsér, J.; Hegedűs, C. Effect of inducible bone morphogenetic protein 2 expression on the osteogenic differentiation of dental pulp stem cells in vitro. Bone 2020, 132, 115214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, E.Y.; Um, S.-H.; Park, J.; Jung, Y.; Cheon, C.-H.; Jeon, H.; Chung, J.J. Precisely Localized Bone Regeneration Mediated by Marine-Derived Microdroplets with Superior BMP-2 Binding Affinity. Small 2022, 18, e2200416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouahoud, S.; Hardwick, J.C.H.; Hawinkels, L.J.A.C. Extracellular BMP Antagonists, Multifaceted Orchestrators in the Tumor and Its Microenvironment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertheloot, D.; Latz, E.; Franklin, B.S. Necroptosis, pyroptosis and apoptosis: An intricate game of cell death. Cell Mol Immunol 2021, 18, 1106–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Kong, Q.; Wang, Y. Regulating inflammation and apoptosis: A smart microgel gene delivery system for repairing degenerative nucleus pulposus. J Control Release 2024, 365, 1004–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Jing, X.; Guo, J.; Yao, X.; Guo, F. Mitophagy in degenerative joint diseases. Autophagy 2021, 17, 2082–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Du, C.; Xiao, P.; Lei, Y.; Zhao, P.; Zhu, Z.; Gao, S.; Chen, B.; Cheng, S.; Huang, W.; et al. Sox9-Increased miR-322-5p Facilitates BMP2-Induced Chondrogenic Differentiation by Targeting Smad7 in Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Stem Cells Int 2021, 2021, 9778207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tanjaya, J.; Shen, J.; Lee, S.; Bisht, B.; Pan, H.C.; Pang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Berthiaume, E.A.; Chen, E.; et al. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-γ Knockdown Impairs Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2-Induced Critical-Size Bone Defect Repair. Am J Pathol 2019, 189, 648–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Peng, C.; Chen, J.; Chen, D.; Yang, B.; He, B.; Hu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Dai, L.; et al. WTAP facilitates progression of hepatocellular carcinoma via m6A-HuR-dependent epigenetic silencing of ETS1. Mol Cancer 2019, 18, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.; Hu, C.; Liu, T.; Sun, Y.; Hu, F.; He, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Ding, J.; Fan, J.; et al. IGF2BP3 enhances lipid metabolism in cervical cancer by upregulating the expression of SCD. Cell Death Dis 2024, 15, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Liang, S.; Gao, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, R.; Yu, W. Extracellular matrix stiffness mediates radiosensitivity in a 3D nasopharyngeal carcinoma model. Cancer Cell Int 2022, 22, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Luo, T.; Hua, H. Targeting extracellular matrix stiffness and mechanotransducers to improve cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol 2022, 15, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Dou, H.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, S.; Xiao, M. Extracellular matrix remodeling in tumor progression and immune escape: From mechanisms to treatments. Mol Cancer 2023, 22, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanov, J.V.; Gantenbein-Ritter, B.; Bertolo, A.; Aebli, N.; Baur, M.; Alini, M.; Grad, S. Role of hypoxia and growth and differentiation factor-5 on differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells towards intervertebral nucleus pulposus-like cells. Eur Cell Mater 2011, 21, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solchaga, L.A.; Penick, K.; Porter, J.D.; Goldberg, V.M.; Caplan, A.I.; Welter, J.F. FGF-2 enhances the mitotic and chondrogenic potentials of human adult bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Physiol 2005, 203, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleibeuker, W.; Zhou, X.; Centlivre, M.; Legrand, N.; Page, M.; Almond, N.; Berkhout, B.; Das, A.T. A sensitive cell-based assay to measure the doxycycline concentration in biological samples. Hum Gene Ther 2009, 20, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Qiu, S.; Wang, P.; Liang, X.; Huang, F.; Wu, H.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W.; Tian, X.; Xu, R.; et al. Cardamonin inhibits breast cancer growth by repressing HIF-1α-dependent metabolic reprogramming. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2019, 38, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.-L.; Wang, S.-S.; Shen, K.-P.; Chen, L.; Peng, X.; Chen, J.-F.; An, H.-M.; Hu, B. Ursolic acid induces apoptosis and anoikis in colorectal carcinoma RKO cells. BMC Complement Med Ther 2021, 21, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, A.S.; Roth, Y.; Oswald, K.A.C.; Ćorluka, S.; Bermudez-Lekerika, P.; Gantenbein, B. In Situ Cell Signalling of the Hippo-YAP/TAZ Pathway in Reaction to Complex Dynamic Loading in an Intervertebral Disc Organ Culture. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Noggin expression in human NPCs and autologous OBs/MSCs. (A, B) Noggin was higher expressed in human NPCs compared to autologous OBs/MSCs. Moreover, the relative expression level of Noggin in human NPCs was 8.379 folds higher than that in OBs (C) and 1.474 folds in MSCs (D) on average respectively. (Shown as mean. p-value, * < 0.05; n =7-8).

Figure 1.

Noggin expression in human NPCs and autologous OBs/MSCs. (A, B) Noggin was higher expressed in human NPCs compared to autologous OBs/MSCs. Moreover, the relative expression level of Noggin in human NPCs was 8.379 folds higher than that in OBs (C) and 1.474 folds in MSCs (D) on average respectively. (Shown as mean. p-value, * < 0.05; n =7-8).

Figure 2.

Transduction of HEK293 with Lenti-shNoggin. (A) The results of transduction under fluorescence microscope. (B) RT-PCR analysis of Noggin expression in the control group and Lenti-shNoggin group. (Scale bar: 100 μm. Mean ± SED. p-value, * * * < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Transduction of HEK293 with Lenti-shNoggin. (A) The results of transduction under fluorescence microscope. (B) RT-PCR analysis of Noggin expression in the control group and Lenti-shNoggin group. (Scale bar: 100 μm. Mean ± SED. p-value, * * * < 0.001).

Figure 3.

NPCs transduced by Lenti-shNoggin showed a significant lower expression of Noggin. (A) Lenti-shNoggin was used to transduce human NPCs. (B) Noggin expression in human NPCs was supressed after transduction. (Scale bar: 100 μm. Mean ± SED. p-value, * * * * < 0.0001; n=3).

Figure 3.

NPCs transduced by Lenti-shNoggin showed a significant lower expression of Noggin. (A) Lenti-shNoggin was used to transduce human NPCs. (B) Noggin expression in human NPCs was supressed after transduction. (Scale bar: 100 μm. Mean ± SED. p-value, * * * * < 0.0001; n=3).

Figure 4.

Low expression of Noggin in human NPCs inhibited cell growth. (A) XTT assay was conducted to check the proliferation of human NPCs transduced by Lenti-shNoggin. (B) The cell apoptosis increased in human NPCs of Lenti-shNoggin group. (C) Quantitative analysis for apoptosis. (Apoptosis under Hoechst 33,258 dye: bright blue. Scale bar: 50 μm. Mean ± SED. p-value, ns > 0.05; * < 0.05; n=3-5).

Figure 4.

Low expression of Noggin in human NPCs inhibited cell growth. (A) XTT assay was conducted to check the proliferation of human NPCs transduced by Lenti-shNoggin. (B) The cell apoptosis increased in human NPCs of Lenti-shNoggin group. (C) Quantitative analysis for apoptosis. (Apoptosis under Hoechst 33,258 dye: bright blue. Scale bar: 50 μm. Mean ± SED. p-value, ns > 0.05; * < 0.05; n=3-5).

Figure 5.

Colony formation assay revealed an inhibition of human NPCs proliferative potential after transduction by Lenti-shNoggin. (A) Transduced human NPCs were plated in 6-well plates and cultured for 14 days. (B) The number of cell clones was counted under the microscope. (Scale bar: 100 μm. Mean ± SED. p-value, * * < 0.01; n=3).

Figure 5.

Colony formation assay revealed an inhibition of human NPCs proliferative potential after transduction by Lenti-shNoggin. (A) Transduced human NPCs were plated in 6-well plates and cultured for 14 days. (B) The number of cell clones was counted under the microscope. (Scale bar: 100 μm. Mean ± SED. p-value, * * < 0.01; n=3).

Figure 6.

Cell viability analysis revealed the dead cells increased in human NPCs transduced by Lenti-shNoggin. (A) Calcein AM and Ethidium Homodimer-1 dye were used to stain the human NPCs after transduction. (B) The semi-quantitative analysis on cell viability about living cells for control and Lenti-shNoggin group. (Scale bar: 100 μm. Mean ± SED. p-value, * < 0.05; * * < 0.01; n=3).

Figure 6.

Cell viability analysis revealed the dead cells increased in human NPCs transduced by Lenti-shNoggin. (A) Calcein AM and Ethidium Homodimer-1 dye were used to stain the human NPCs after transduction. (B) The semi-quantitative analysis on cell viability about living cells for control and Lenti-shNoggin group. (Scale bar: 100 μm. Mean ± SED. p-value, * < 0.05; * * < 0.01; n=3).

Figure 7.

Low expression of Noggin in human NPCs could hinder cellular anabolism and enhance catabolism. (A) Suppression of Noggin resulted in a downregulation of the anabolic markers in human NPCs. (B) Catabolism in human NPCs after transduction. (Shown as mean. p-value, * * < 0.01; * * * * < 0.0001; n=6).

Figure 7.

Low expression of Noggin in human NPCs could hinder cellular anabolism and enhance catabolism. (A) Suppression of Noggin resulted in a downregulation of the anabolic markers in human NPCs. (B) Catabolism in human NPCs after transduction. (Shown as mean. p-value, * * < 0.01; * * * * < 0.0001; n=6).

Table 1.

The collected NP tissues from human donors for NPCs isolation and transduction in this study.

Table 1.

The collected NP tissues from human donors for NPCs isolation and transduction in this study.

| Donor |

Year of birth |

Sex |

Type |

Level |

NP tissues |

NPCs isolation |

| 1 |

1988 |

M |

T |

L3-L4 |

√ |

√ |

| 2 |

1994 |

M |

T |

L1-L2 |

√ |

√ |

| 3 |

1992 |

M |

T |

L2-L3 |

√ |

√ |

| 4 |

1994 |

M |

T |

T12-L1 |

√ |

√ |

| 5 |

1974 |

M |

T |

T12-L1 |

√ |

√ |

| 6 |

2004 |

M |

T |

L2-L3 |

√ |

√ |

Table 2.

The details of donors for comparison of Noggin expression between NPCs and autologous MSCs/OBs.

Table 2.

The details of donors for comparison of Noggin expression between NPCs and autologous MSCs/OBs.

| Donor |

Year of birth |

Sex |

Type |

NPtissues |

Level |

Bonemarrow |

Bonefragments |

| 1 |

1988 |

F |

T |

√ |

T12-L1 |

x |

√ |

| 2 |

1988 |

M |

T |

√ |

L2-L3 |

√ |

√ |

| 3 |

1950 |

F |

T |

√ |

L1-L2 |

x |

√ |

| 4 |

1985 |

F |

T |

√ |

T12-L1 |

x |

√ |

| 5 |

1994 |

M |

T |

√ |

L1-L2 |

√ |

√ |

| 6 |

1947 |

F |

T |

√ |

L1-L2 |

√ |

√ |

| 7 |

1992 |

M |

T |

√ |

L2-L3 |

√ |

√ |

| 8 |

1994 |

M |

T |

√ |

T12-L1 |

√ |

√ |

| 9 |

1946 |

M |

D |

√ |

L3-L4 |

√ |

x |

| 10 |

1961 |

M |

D |

√ |

L3-L4 |

√ |

x |

Table 3.

The shRNA sequences to target Noggin.

Table 3.

The shRNA sequences to target Noggin.

| shRNA |

Primer sequence |

| Noggin |

5′ GCTGCGGAGGAAGTTACAGATGTGGCTGT 3′ |

Table 4.

Human gene primers for qPCR.

Table 4.

Human gene primers for qPCR.

| Gene |

Accession No. |

Forward sequence |

Reverse sequence |

| GAPDH |

NM_001289745.2 |

ATC TTC CAG GA

G CGA GAT |

GGA GGC ATT GCT

GAT GAT |

| NOG |

NM_001078309.1 |

CAG CAC TAT CT

C CAC ATC CG |

CAG CAG CGT CTC

GTT CAG |

| ACAN |

NM_001135.4 |

CAT CAC TGC AGC TGT CAC |

AGC AGC ACT ACC TCC TTC |

| COL1 |

NM_000089.3 |

GTG GCA GTG AT

G GAA GTG |

CAC CAG TAA GGC

CGT TTG |

| COL2 |

XM_017018831.3 |

AGC AGC AAG AGC AAG GAG AA |

GTA GGA AGG TCA TCT GGA |

| MMP3 |

NM_002422.5 |

CAA GGC ATA GAG ACA ACA TAG A |

GCA CAG CAA CAG TAG GAT |

| MMP13 |

NM_002427.4 |

AGT GGT GGT GAT GAA GAT |

CTA AGG TGT TAT CGT CAA GTT |

| ADAMTS4 |

XM_054339708.1 |

TTC CTG GAC AAT GGC TAT GG |

GTG GAC AAT GGC GTG AGT |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).