Submitted:

04 September 2024

Posted:

05 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals

2.2. Feeding Trial

2.3. Cloning and Sequencing of S. paramamosain fatp1 cDNA

2.4. Bioinformatic Analysis

2.5. RNA Interference

2.6. Tissue Total Lipid, Triglyceride, and Cholesterol Contents, and Fatty Acid Composition Analysis

2.7. Histological Analysis

2.8. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

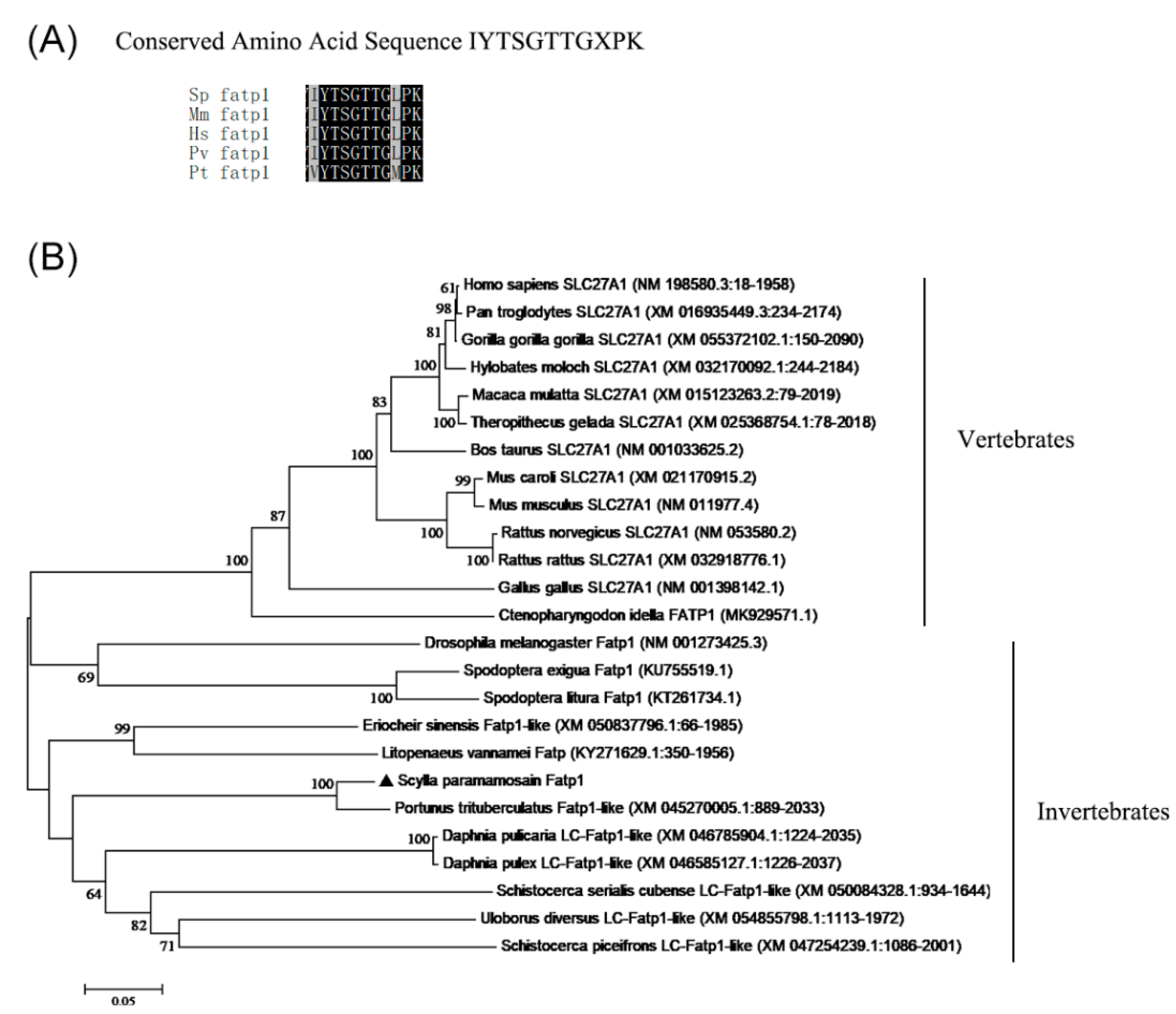

3.1. Sequence and Phylogenetic Analysis

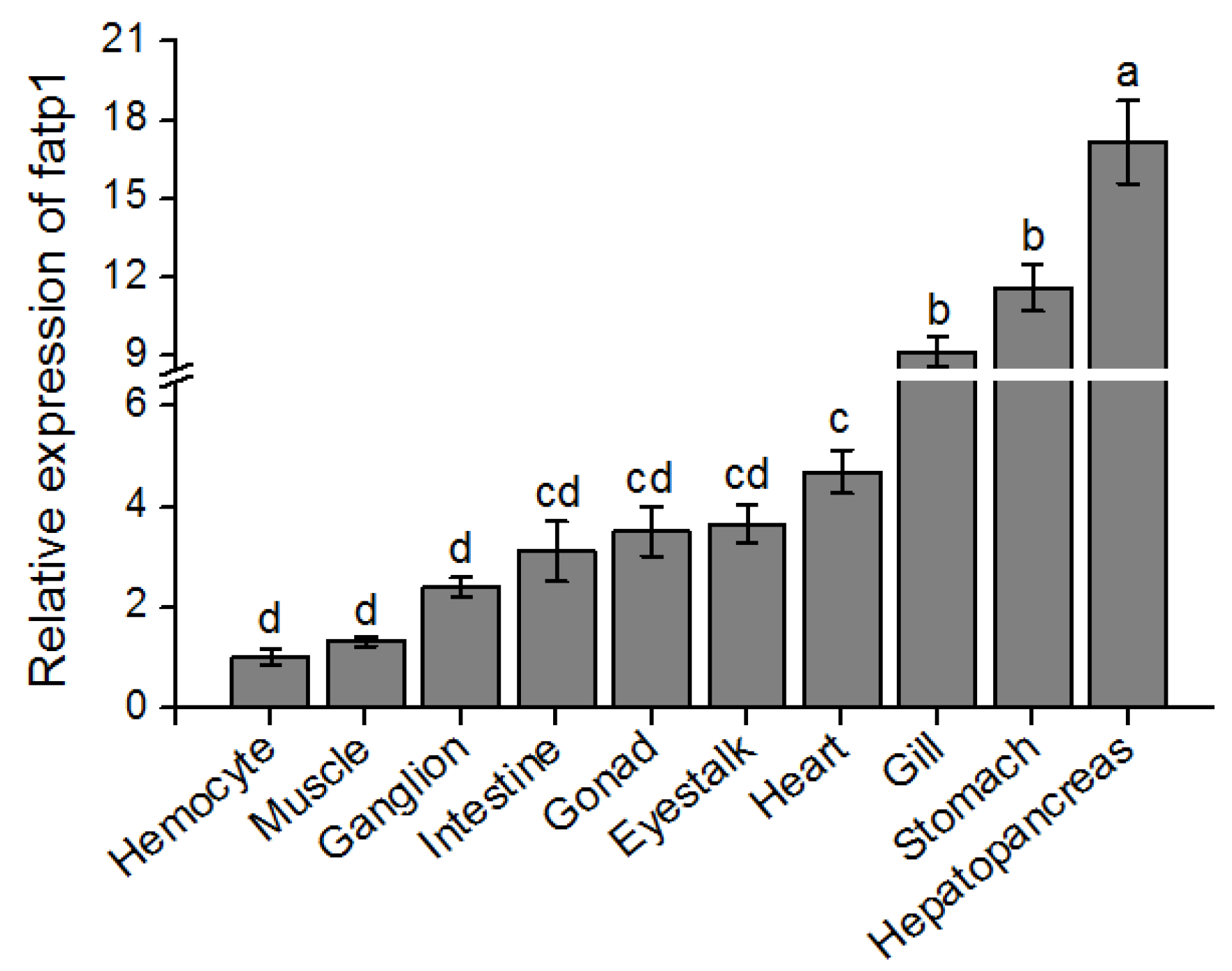

3.2. Tissue Distribution Pattern of fatp1 in Mud Crabs

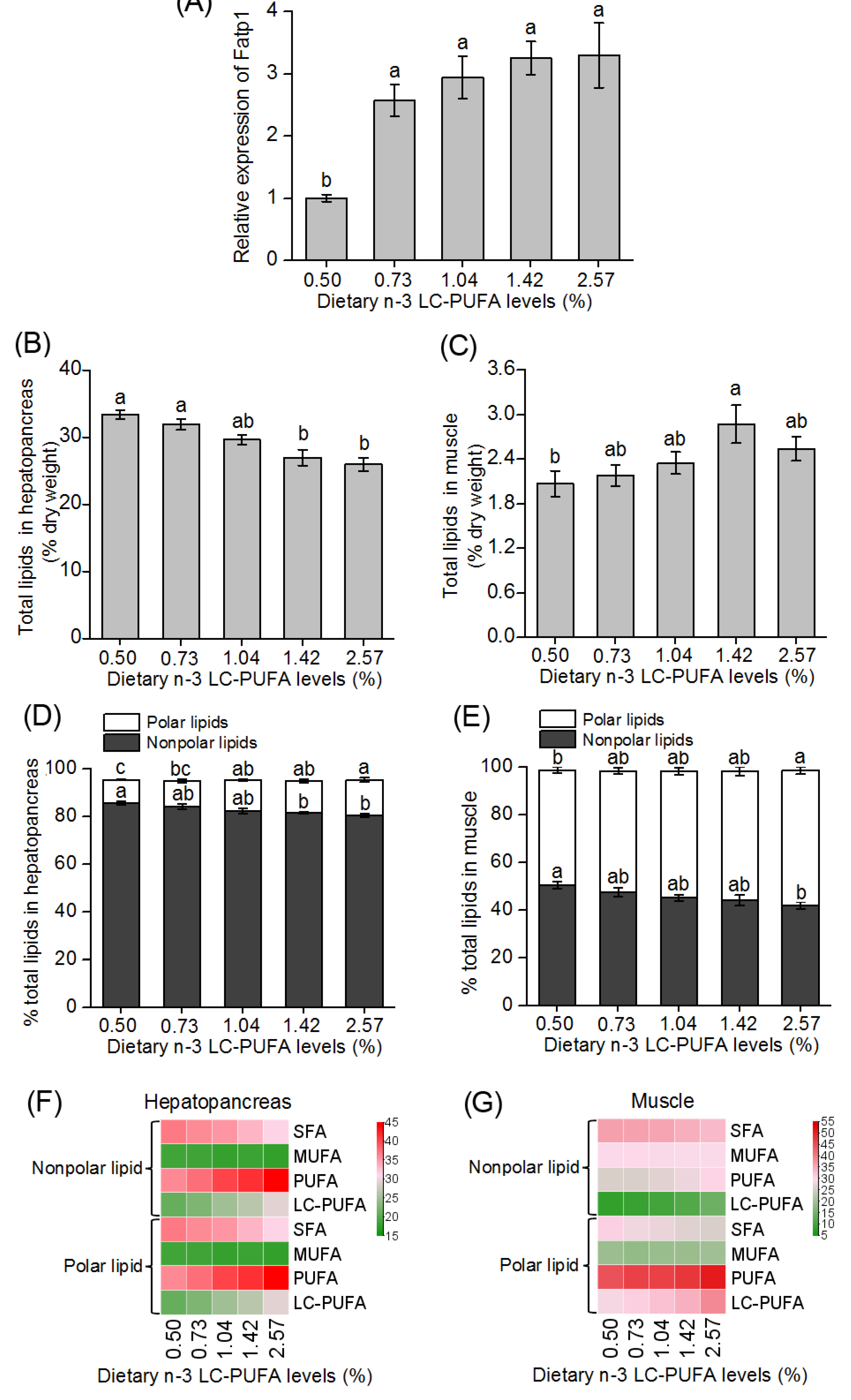

3.3. Expression of fatp1 in Hepatopancreas of Crabs Fed Different Dietary n-3 LC-PUFA Levels

3.4. Total Lipid and Fatty Acid Composition in Hepatopancreas and Muscle of Crabs Fed Different Dietary n-3 LC-PUFA Levels

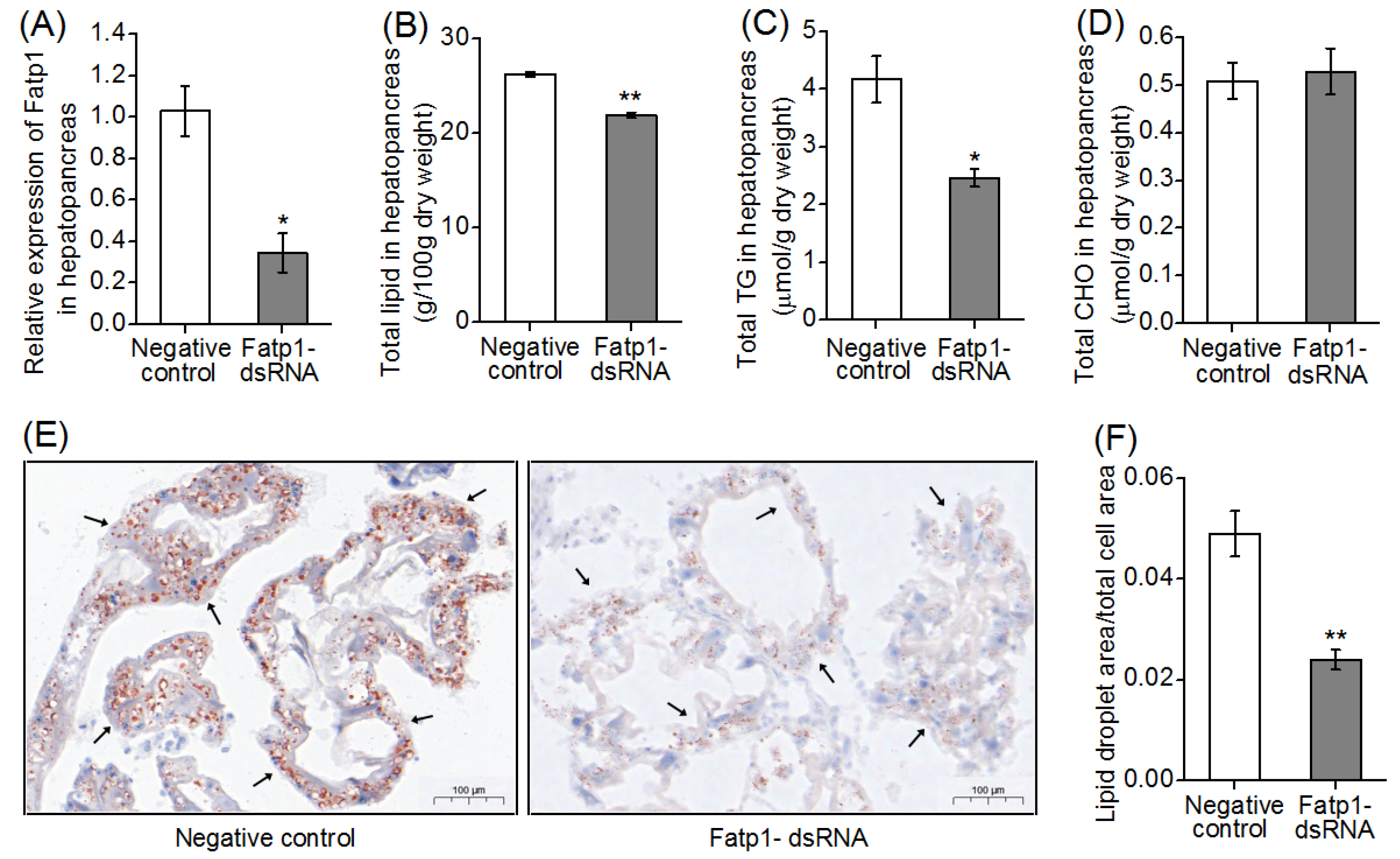

3.5. Total Lipid, Triglyceride and Cholesterol Contents, and Fatty Acid Compositions in Hepatopancreas and Muscle after Knockdown of the fatp1 Gene in Mud Crab

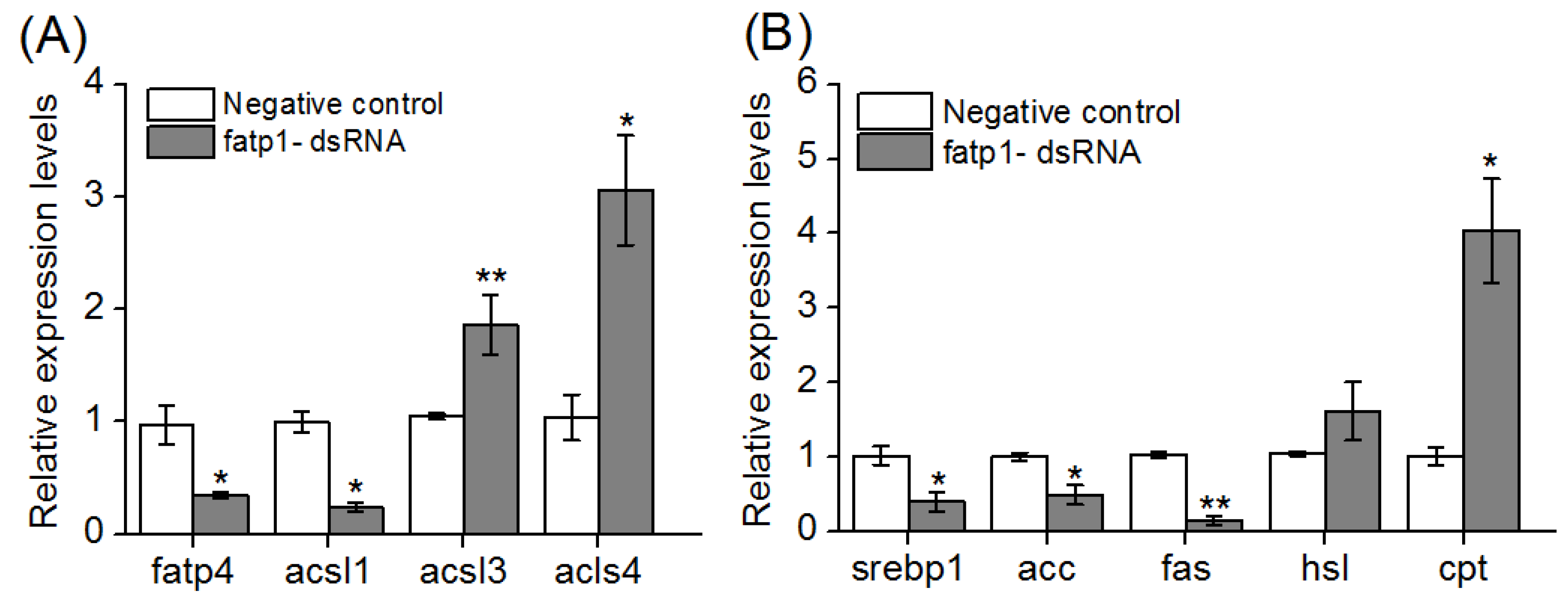

3.6. Expression of Lipid Metabolism-Related Genes in Hepatopancreas of Crabs after Knockdown of the fatp1 Gene

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gimeno, R.E. Fatty acid transport proteins. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2007, 18, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.M.; Stahl, A. SLC27 fatty acid transport proteins. Mol. Aspects Med. 2013, 34, 516–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doege, H.; Stahl, A. Protein-mediated fatty acid uptake: Novel insights from in vivo models. Physiology 2006, 21, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, S.E.; Listenberger, L.L.; Ory, D.S.; Schaffer, J.E. Membrane topology of the murine fatty acid transport protein 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 37042–37050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, D.; Stahl, A.; Lodish, H.F. A family of fatty acid transporters conserved from mycobacterium to man. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998, 95, 8625–8629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faergeman, N.J.; DiRusso, C.C.; Elberger, A.; Knudsen, J.; Black, P.N. Disruption of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologue to the murine fatty acid transport protein impairs uptake and growth on long-chain fatty acids. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 8531–8538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiRusso, C.C.; Li, H.; Darwis, D.; Watkins, P.A.; Berger, J.; Black, P.N. Comparative biochemical studies of the murine fatty acid transport proteins (FATP) expressed in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 16829–16837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahl, A. A current review of fatty acid transport proteins (SLC27). Pflug. Arch. Eur. J. Phy. 2004, 447, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, J.E.; Lodish, H.F. Expression cloning and characterization of a novel adipocyte long chain fatty acid transport protein. Cell 1994, 79, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, A.; Evans, J.G.; Pattel, S.; Hirsch, D.; Lodish, H.F. Insulin causes fatty acid transport protein translocation and enhanced fatty acid uptake in adipocytes. Dev. Cell 2002, 2, 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.; Nemoto, M.; Gelman, L.; Geffroy, S.; Najib, J.; Fruchart, J.C.; Roevens, P.; de Martinville, B.; Deeb, S.; Auwerx, J. The human fatty acid transport protein-1 (SLC27A1; FATP-1) cDNA and gene: organization, chromosomal localization, and expression. Genomics 2000, 66, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohl, J.; Ring, A.; Hermann, T.; Stremmel, W. Role of FATP in parenchymal cell fatty acid uptake. BBA-Mol. Cell Bio. L. 2004, 1686, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.P.; Zhu, R.R.; Shi, D.S. The role of FATP1 in lipid accumulation: a review. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2021, 476, 1897–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, S.; Wiczer, B.M.; Smith, A.J.; Hall, A.M.; Bernlohr, D.A. Fatty acid metabolism in adipocytes: functional analysis of fatty acid transport proteins 1 and 4. J. Lipid Res. 2007, 48, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.W.; Kazantzis, M.; Doege, H.; Ortegon, A.M.; Tsang, B.; Falcon, A.; Stahl, A. Fatty acid transport protein 1 is required for nonshivering thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue. Diabetes 2006, 55, 3229–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.W.; Ortegon, A.M.; Tsang, B.; Doege, H.; Feingold, K.R.; Stahl, A. FATP1 is an insulin-sensitive fatty acid transporter involved in diet-induced obesity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 26, 3455–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.L.; Luo, Y.L.; Wang, R.S.; Zhou, B.; Huang, Z.Q.; Jia, G.; Zhao, H.; Liu, G.M. Effects of fatty acid transport protein 1 on proliferation and differentiation of porcine intramuscular preadipocytes. Anim. Sci. J. 2017, 88, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, D.; Guitart, M.; Garcia-Martinez, C.; Mauvezin, C.; Orellana-Gavalda, J.M.; Serra, D.; Gomez-Foix, A.M.; Hegardt, F.G.; Asins, G. Novel role of FATP1 in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle cells. J. Lipid Res. 2009, 50, 1789–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guitart, M.; Osorio-Conles, O.; Pentinat, T.; Cebria, J.; Garcia-Villoria, J.; Sala, D.; Sebastian, D.; Zorzano, A.; Ribes, A.; Jimenez-Chillaron, J.C.; Garcia-Martinez, C.; Gomez-Foix, A.M. Fatty acid transport protein 1 (FATP1) localizes in mitochondria in mouse skeletal muscle and regulates lipid and ketone body disposal. Plos One 2014, 9, e98109. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, F.F.; Xie, L.; Ma, J.E.; Luo, W.; Zhang, L.; Chao, Z.; Chen, S.H.; Nie, Q.H.; Lin, Z.M.; Zhang, X.Q. Lower expression of SLC27A1 enhances intramuscular fat deposition in chicken via down-regulated fatty acid oxidation mediated by CPT1A. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Brink, D.M.; Cubizolle, A.; Chatelain, G.; Davoust, N.; Girard, V.; Johansen, S.; Napoletano, F.; Dourlen, P.; Guillou, L.; Angebault-Prouteau, C.; Bernoud-Hubac, N.; Guichardant, M.; Brabet, P.; Mollereau, B. Physiological and pathological roles of FATP-mediated lipid droplets in Drosophila and mice retina. Plos Genetics 2018, 14, e1007627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohnishi, A.; Hashimoto, K.; Imai, K.; Matsumoto, S. Functional characterization of the Bombyx mori fatty acid transport protein (BmFATP) within the silkmoth pheromone gland. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 5128–5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kage-Nakadai, E.; Kobuna, H.; Kimura, M.; Gengyo-Ando, K.; Inoue, T.; Arai, H.; Mitani, S. Two very long chain fatty acid acyl-CoA synthetase genes, acs-20 and acs-22, have roles in the cuticle surface barrier in Caenorhabditis elegans. Plos One 2010, 5, e8857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jin, M.; Cheng, X.; Hu, X.; Zhao, M.; Yuan, Y.; Sun, P.; Jiao, L.; Tocher, D.R.; Zhou, Q. Hepatopancreas transcriptomic and lipidomic analyses reveal the molecular responses of mud crab (Scylla paramamosain) to dietary ratio of docosahexaenoic acid to eicosapentaenoic acid. Aquaculture 2022, 551, 737903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.J.; Jiang, G.Z.; Liu, W.B.; Abasubong, K.P.; Zhang, D.D.; Li, X.F.; Chi, C.; Liu, W.B. Evaluation of dietary linoleic acid on growth as well as hepatopancreatic index, lipid accumulation oxidative stress and inflammation in Chinese mitten crabs (Eriocheir sinensis). Aquaculture Reports 2022, 22, 100983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Gong, J.; Zeng, C.; Wu, X. Effect of estradiol on hepatopancreatic lipid metabolism in the swimming crab, Portunus trituberculatus. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2019, 280, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Shi, X.; Fang, S.; Xie, Z.; Guan, M.; Li, S.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ikhwanuddin, M.; Ma, H. Different biochemical composition and nutritional value attribute to salinity and rearing period in male and female mud crab Scylla paramamosain. Aquaculture 2019, 513, 734417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Nie, X.F.; Cheng, Y.; Shen, J.J.; He, X.D.; Wang, S.Q.; You, C.H.; Li, Y.Y. Comparative analysis of growth performance, feed utilization, and antioxidant capacity of juvenile mud crab, Scylla Paramamosian, reared at two different conditions. Crustaceana 2021, 94, 1021–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.Y.; Waiho, K.; Huang, Z.; Li, S.K.; Zheng, H.P.; Zhang, Y.L.; Ikhwanuddin, M.; Lin, F.; Ma, H.Y. Growth performance and biochemical composition dynamics of ovary, hepatopancreas and muscle tissues at different ovarian maturation stages of female mud crab, Scylla paramamosain. Aquaculture 2020, 515, 734560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.J.; Chen, C.S.; Tan, S.Y.; He, X.D.; Wang, S.Q.; Tocher, D.R.; Lin, F.; Sun, Z.J.; Wen, X.B.; Li, Y.Y.; Waiho, K.; Wu, X.G.; Chen, C.Y. Identification of a novel crustacean vascular endothelial growth factor b-like in the mud crab Scylla paramamosain, and examination of its role in lipid accumulation. Aquaculture 2023, 575, 739793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.L.; Shi, X.; Fang, S.B.; Zhang, Y.; You, C.H.; Ma, H.Y.; Lin, F. Comparative transcriptome analysis combining SMRT and NGS sequencing provides novel insights into sex differentiation and development in mud crab (Scylla paramamosain). Aquaculture 2019, 513, 734447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Monroig, O.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Zheng, X.; Dick, J.R.; You, C.; Tocher, D.R. Vertebrate fatty acyl desaturase with Δ4 activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 16840–16845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Jiang, M.; Lian, G.L.; Liu, Q.; Shi, M.; Li, T.Y.; Song, L.T.; Ye, J.; He, Y.; Yao, L.M.; Zhang, C.X.; Lin, Z.Z.; Zhang, C.S.; Zhao, T.J.; Jia, W.P.; Li, P.; Lin, S.Y.; Lin, S.C. AIDA selectively mediates downregulation of fat synthesis enzymes by ERAD to retard intestinal fat absorption and prevent obesity. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuhlsatz-Krouper, S.M.; Bennett, N.E.; Schaffer, J.E. Molecular aspects of fatty acid transport: mutations in the IYTSGTTGXPK motif impair fatty acid transport protein function. Prostaglandins Leukotrienes Essent. Fatty Acids 1999, 60, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, S.G.; Fujii, T.; Ito, K.; Nakano, R.; Ishikawa, Y. Cloning and functional characterization of a fatty acid transport protein (FATP) from the pheromone gland of a lichen moth, Eilema japonica, which secretes an alkenyl sex pheromone. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011, 41, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Wu, X.G.; Liu, Z.J.; Zheng, H.J.; Cheng, Y.X. Insights into hepatopancreatic functions for nutrition metabolism and ovarian development in the crab Portunus trituberculatus: gene discovery in the comparative transcriptome of different hepatopancreas stages. Plos One 2014, 9, e84921. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, G. Functional cytology of the hepatopancreas of decapod crustaceans. J. Morphol. 2019, 280, 1405–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Gui, L.; Zan, L.; Zhao, C. The effect of FATP1 on adipocyte differentiation in Qinchuan beef cattle. Animals 2021, 11, 2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, A.; Gimeno, R.E.; Tartaglia, L.A.; Lodish, H.F. Fatty acid transport proteins: a current view of a growing family. Trends Endocrin. Met. 2001, 12, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soupene, E.; Kuypers, F.A. Mammalian long-chain Acyl-CoA synthetases. Exp. Biol. Med. 2008, 233, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.M.; Frahm, J.L.; Li, L.O.; Coleman, R.A. Acyl-coenzyme A synthetases in metabolic control. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2010, 21, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes-Marques, M.; Cunha, I.; Reis-Henriques, M.A.; Santos, M.M.; Castro, L.F.C. Diversity and history of the long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase (Acsl) gene family in vertebrates. BMC Evol. Bio. 2013, 13, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polyak, S.W.; Abell, A.D.; Wilce, M.C.J.; Zhang, L.; Booker, G.W. Structure, function and selective inhibition of bacterial acetyl-coa carboxylase. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2012, 93, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recazens, E.; Mouisel, E.; Langin, D. Hormone-sensitive lipase: sixty years later. Prog. Lipid Res. 2021, 82, 101084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, J.; Ring, A.; Ehehalt, R.; Herrmann, T.; Stremmel, W. New concepts of cellular fatty acid uptake: role of fatty acid transport proteins and of caveolae. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2004, 63, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melton, E.M.; Cerny, R.L.; Watkins, P.A.; Dirusso, C.C.; Black, P.N. Human fatty acid transport protein 2a/very long chain acyl-CoA synthetase 1 (FATP2a/Acsvl1) has a preference in mediating the channeling of exogenous n-3 fatty acids into phosphatidylinositol. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 30670–30679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Pei, Z.; Maiguel, D.; Toomer, C.J.; Watkins, P.A. The fatty acid transport protein (FATP) family: Very long chain acyl-CoA synthetases or solute carriers? J. Mol. Neurosci. 2007, 33, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickerson, J.G.; Alkhateeb, H.; Benton, C.R.; Lally, J.; Nickerson, J.; Han, X.-X.; Wilson, M.H.; Jain, S.S.; Snook, L.A.; Glatz, J.F.C.; Chabowski, A.; Luiken, J.J.F.P.; Bonen, A. Greater transport efficiencies of the membrane fatty acid transporters FAT/CD36 and FATP4 compared with FABPpm and FATP1 and differential effects on fatty acid esterification and oxidation in rat skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 16522–16530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, G.P.; Chou, C.J.; Lally, J.; Stellingwerff, T.; Maher, A.C.; Gavrilova, O.; Haluzik, M.; Alkhateeb, H.; Reitman, M.L.; Bonen, A. Increasing skeletal muscle fatty acid transport protein 1 (FATP1) targets fatty acids to oxidation and does not predispose mice to diet-induced insulin resistance. Diabetologia 2011, 54, 1457–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fatty acids |

Hepatopancreas | Muscle | |||||

| Negative control |

fatp1 dsRNA | P - value | Negative control |

fatp1 dsRNA | P - value | ||

| 12:00 | 3.45 ± 0.20 | 2.67 ± 0.23 | 0.044 | 1.04 ± 0.19 | 0.40 ± 0.03 | 0.027 | |

| 14:00 | 4.40 ± 0.23 | 3.92 ± 0.42 | 0.352 | 2.24 ± 0.29 | 1.23 ± 0.04 | 0.028 | |

| 16:00 | 15.97 ± 0.63 | 17.62 ± 1.88 | 0.436 | 17.83 ± 0.33 | 18.88 ± 0.81 | 0.296 | |

| 18:00 | 5.63 ± 0.30 | 3.73 ± 0.94 | 0.103 | 10.89 ± 0.25 | 11.45 ± 0.43 | 0.319 | |

| 16:1n-9 | 3.52 ± 0.28 | 4.24 ± 0.80 | 0.427 | 2.20 ± 0.26 | 2.26 ± 0.35 | 0.894 | |

| 16:1n-7 | 0.67 ± 0.07 | 1.52 ± 0.37 | 0.066 | 0.89 ± 0.19 | 4.89 ± 1.17 | 0.028 | |

| 18:1n-9 | 14.34 ± 0.31 | 14.70 ± 0.32 | 0.453 | 11.00 ± 0.54 | 10.39 ± 0.80 | 0.558 | |

| 20:1n-9 | 0.85 ± 0.10 | 1.85 ± 0.34 | 0.03 | 0.55 ± 0.12 | 0.91 ± 0.06 | 0.054 | |

| 18:2n-6 | 13.12 ± 0.58 | 13.28 ± 0.74 | 0.87 | 7.19 ± 0.74 | 6.50 ± 0.62 | 0.509 | |

| 18:3n-3 | 4.32 ± 0.12 | 3.87 ± 0.14 | 0.051 | 1.59 ± 0.18 | 1.44 ± 0.28 | 0.679 | |

| 20:4n-6 | 6.94 ± 0.24 | 6.68 ± 0.48 | 0.649 | 12.48 ± 0.94 | 10.81 ± 0.31 | 0.168 | |

| 22:4n-6 | 0.45 ± 0.12 | 0.44 ± 0.03 | 0.948 | 1.06 ± 0.20 | 1.03 ± 0.23 | 0.919 | |

| 20:5n-3 | 6.58 ± 0.27 | 6.08 ± 0.46 | 0.385 | 14.22 ± 0.19 | 11.97 ± 1.31 | 0.165 | |

| 22:5n-3 | 1.40 ± 0.08 | 1.42 ± 0.06 | 0.866 | 1.35 ± 0.06 | 0.98 ± 0.14 | 0.071 | |

| 22:6n-3 | 6.41 ± 0.34 | 6.27 ± 0.42 | 0.806 | 7.18 ± 0.40 | 5.98 ± 0.85 | 0.268 | |

| ΣSFA1 | 29.44 ± 1.32 | 27.94 ± 1.60 | 0.496 | 31.99 ± 0.68 | 31.96 ± 1.29 | 0.985 | |

| ΣMUFA2 | 19.39 ± 0.49 | 22.31 ± 1.04 | 0.044 | 14.64 ± 0.69 | 18.45 ± 0.95 | 0.032 | |

| ΣPUFA3 | 39.21 ± 1.54 | 38.04 ± 1.59 | 0.615 | 45.07 ± 1.02 | 38.70 ± 3.14 | 0.126 | |

| ΣLC-PUFA4 | 21.78 ± 0.85 | 20.89 ± 1.27 | 0.584 | 36.28 ± 0.70 | 30.76 ± 2.57 | 0.107 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).