1. Introduction

Using geothermal energy for mining natural gas hydrates under the seabed is an efficient and low-carbon method[

1]. As the fluid injected into the deeper geothermal reservoir, the heated water conveys the heat and is reinjected into the fractured hydrate reservoir[

2]. During the hydrate dissolving in the reservoir, the thermal fluid enhances the porosity of structure, thereby augmenting the flow capacity and convective heat transfer capacity of the reservoir[

3]. Accordingly, when heat flows through the medium of hydrate, a condition of fully multi-field coupling must be considered with every physical field of thermal-flowing-mechanic-chemical (TFMC)[

4]. The simulation must therefore analyze these interactions between the fields. It is necessary to analyze the mutual influence of key parameters between multi-field coupling during simulation.

According to the reviews of literatures, there must be functions or laws to express the coupling ways of each field in TFMC. The coupling ways between flowing and mechanic fields are the Biot equation and Darcy law[

5]. The consolidation coefficient was used to describe the harmonic relationship between the solid stress field and the fluid pressure field. The pressure field changes the fluid velocity field by Darcy law. However, the porosity changes greatly due to hydrate dissolution, and the Biot equation is no longer applicable. The coupling ways of flowing and thermal field are the convection heat transfer equation and viscosity-temperature relationship[

6]. The change of temperature has little effect on the viscosity, and the flow in the microporous structure is laminar, and the average size of the pores is generally smaller than the thickness of the boundary layer. Therefore, the convection heat transfer equation is directly used to simulate the internal energy transfer in the pores. Its thermal diffusion coefficient should include heat conduction and heat convection, while heat conduction is retained in the solid. The coupling ways between flowing field and chemical field are the Kim-Bishnoi (K-B) equation in pressure form and the kinetics of methane hydrate decomposition[

7]. The pressure distribution in the flowing field will affect the chemical reaction rate based on the K-B equation. The energy consumption caused by chemical reactions at the microscale will lead to kinetic energy transfer in the flowing field, but it will not be too obvious. The coupling way of stress field and chemical field is porosity change. Hydrate dissolution will increase porosity and reduce the elastic modulus of the solid skeleton. The elastic modulus decreasing will lead to changes in the pressure field, which in turn affects the reaction rate. The coupling ways of mechanic and thermal field are thermal expansion and effective heat conductivity. When hydrates dissolving, the thermal expansion deformation of the solid structure is very tiny, but the porosity changes greatly, which in turn affects the effective heat conductivity, which has a significant impact on convective heat transfer. The coupling way of thermal and chemical field is K-B equation in thermal form. The reaction rate coefficient of the K-B equation is related to temperature, and the equilibrium pressure is also related to temperature, but the effect is not significant. The chemical reaction has a great influence on the internal energy transfer. The dissolution enthalpy of the chemical reaction will absorb a lot of heat and affect the internal energy diffusion rate[

8].In summary, when comprehensively considering the multi-field coupling of TFMC, the unsteady Darcy's law, the unsteady convective heat transfer equation, and the unsteady K-B equation are important governing equations. Therefore, the average permeability, effective thermal conductivity and reaction rate coefficient are critical physical parameters. At microscale simulation, Darcy's law becomes the N-S equation, and the K-B equation is a macroscale equation and is not applicable. Therefore, it is necessary to solve the above key physical parameters through pore-scale simulation of the N-S equation, convective heat transfer equation, and fluid-solid boundary changes, and verify Darcy's law and K-B equation of macro-scale condition.

The lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) is a discretely REV scale simulation method based on the Boltzmann distribution equation. It can not only characterize the effects of microscale simulation, but also has perfect convergence and stability. Using the dual distribution function (DDF-LBM) method, the distribution of velocity and temperature field at the microscale modelling can be more accurately calculated[

9]. At the same time, the calculation efficiency is relatively faster and it has better self-stability for the fluid-solid boundary behaviors. Huo et al. used the DDF-LBM to simulate the solid-liquid boundary change during the dissolution of phase change of silicon materials in a square cavity and verified the feasibility of this method under natural thermal convection conditions[

10]. He et al. reviewed and introduced the detailed method of LBM simulation of single fluid solid-liquid phase change[

11]. The literature listed the expression of phase change latent heat in the convection heat transfer equation in the DDF method, and introduced MRT to correct the nonlinear coefficient of the equation. However, this paper did not describe the analysis from REV to macroscale, and achieve no physical meaning overlap from micro to macro. Zhang et al. used the DDF-LBM to simulate the hydrate dissolution process at the pore scale and calculated the variation of macroscale permeability with hydrate saturation[

12]. However, the literature did not conduct sufficient research on the effective thermal conductivity, hydrate activation reaction and phase change latent heat, resulting in inaccurate calculation results. Ji et al. used the MRT-LBM to study the two-phase curves of gas-water flow during hydrate dissolution, but did not consider the influence of multi-field coupling on the dissolution law[

13]. Ross-Jones et al. used the DDF-LBM to study the simulation results of the effective thermal conductivity of porous structures at the nanoscale[

14]. The calculation results verified that the DDF-LBM can be directly used to simulate convective heat transfer at the nanoscale, but the model did not consider the effects of forced convection and phase change on flow simulation. In summary, LBM can be applied to the microscale simulation of porous media, but the key parameters of the methods need to be modified to make the calculation results more satisfied with really physical phenomena such as convective heat transfer and phase change entropy absorption.

In this paper, the influence of hydrate activation reaction on flow-heat transfer will be considered, based on DDF-LBM. And a simulation calculation method of heat flow and solidification will be designed, based on fully multi-field coupling, by TFMC. According to the calculated results, the permeability, thermal conductivity, activation reaction rate and other parameters of the models under multi-field coupling conditions would be analyzed, which can provide more accurate reference for mining natural gas hydrates using geothermal fluids.

2. Methodology

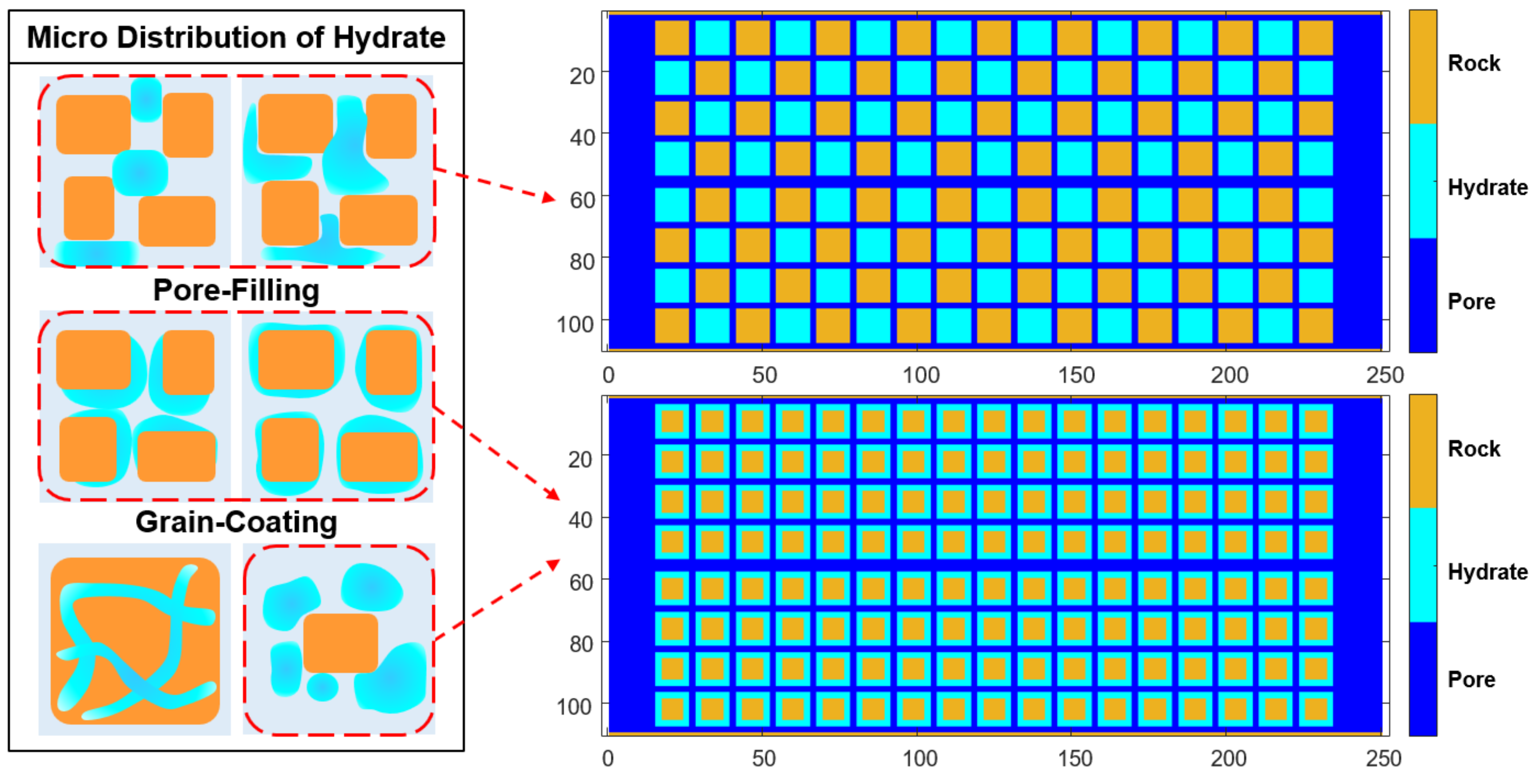

Many literatures have shown that natural gas hydrate reservoirs currently exist in different modes at microscale[

12]. In order to better characterize the hydrate dissolution mechanism, we designed two different microstructures, the Pore-filling type and the Grain-coating type, based on two common hydrate reservoir modes. The model size Length × Width = 250×110, where the size of hydrate and rock particles is 11×11. The square particles of rock and hydrate make the fluid flowing in the pores more similar to the flowing in slender pipes. This design ensures that the models have a porosity closer to the real reservoir (less than 15%) while allowing thermal fluid to flow smoothly[

2].

Figure 1.

Two different microstructures of typical hydrate reservoirs.

Figure 1.

Two different microstructures of typical hydrate reservoirs.

According to the literatures[

5], when simulating the thermal fluid flowing through porous media with hydrates, we need to set the Mass Equation (1), Momentum Equation (2), and Energy Equation (3) under the microscale as the controlling functions of the model. The controlling functions used in LBM are as follows.

where

,

,

,

stand for the density, velocity, pressure and temperature.

is the viscosity of fluid.

is the heat capability of fluid or solid.

is the heat conductivity.

is the heat source term.

is the heat absorption entropy of hydrate dissolution.

is the hydrate dissolution rate.

Some literatures have shown the experiments results under microscale, with the actual pressure and temperature conditions of natural gas hydrate reservoirs[

15,

16]. The simulations have shown that, even if hydrates release gases, such as methane after dissolution, these types of gas will be difficult to gather as continuous bubbles in water due to the high pressure in storage and will basically be mixed in the flowing water as isolated particles. Therefore, only two structural grids, fluid and solid, were established in the LBM of this paper. The influence of continuous bubbles on the flow were not considered, and only a little correction to the viscosity and density of the liquid, based on mixed bubbles.

2.1. Lattice Boltzmann Method for Convection Simulation

The simulation fields in DDF-LBM include density field and temperature field. The Distribution Equation (4) and Equilibrium Distribution Function (5) of the density field and the Distribution Equation (6) and Equilibrium Distribution Function (7) of the temperature field in the D2Q9 model are as follows.

where

and

are the relaxion frequency of density and temperature. In solid heat conduction problems,

is generally a function of the thermal diffusivity

. However, in conjugate convection, energy transfer is not only heat conduction, but also the flow affects the movement of internal energy, which is forced heat convection. Therefore, in the DDF-LBM simulation for conjugate convection, the thermal diffusion rate of fluid should be the combined effect of heat conduction and energy migration, which is,

, where

and

.

stands for the thermal diffusivity of fluid at stagnation[

17]. Using the modified relaxation frequency

in the fluid temperature grid can more accurately calculate the coupling of fluid convection and solid heat transfer in porous media under microscale.

2.2. Lattice Boltzmann Method for Phase Change

Since the heat source term

in the temperature field distribution equation only exists at the equilibrium temperature and pressure, it is zero under other conditions. Therefore, in the LBM simulation codes, the processing of source term

can be carried out according to the following equations.

where

is the equilibrium temperature.

,

stand for the lattice of hydrate as solid.

,

stand for the lattice of hydrate as fluid.

is the temperature corresponding to the cumulative internal energy of the solid hydrate lattice reaching equilibrium.

is the molecular weight of the hydrate. Common Type I and Type II natural gas hydrate

have a molecular weight of 115g/mol[

18]. Then source term in Equation (9) can be calculated as follow.

It means that, hydrate in equilibrium needs to absorb the internal energy corresponding to 215K before it can dissolve from the solid phase into fluid phase.

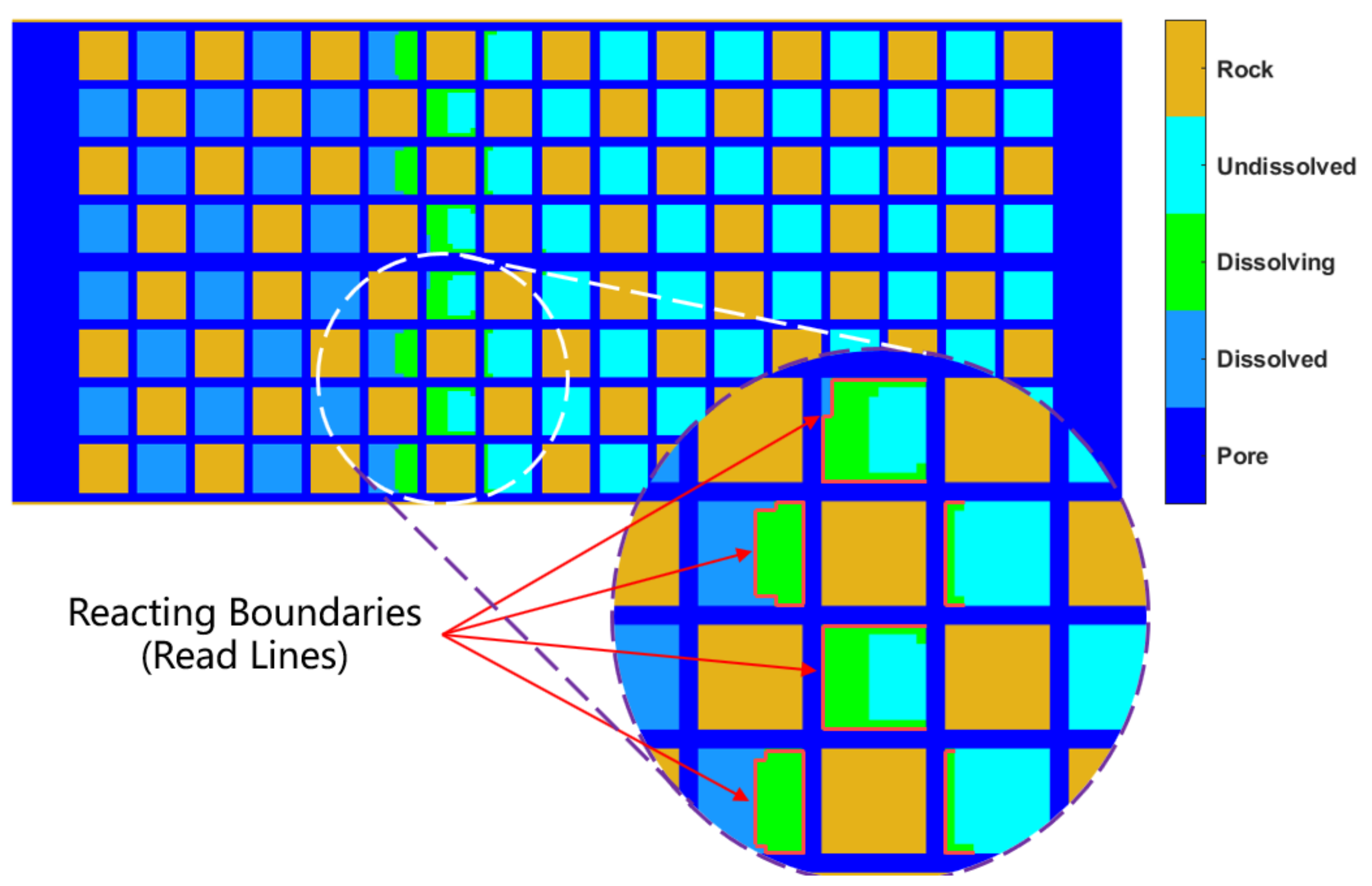

2.3. Lattice Boltzmann Method for Hydrate Reaction

The macroscopic model of hydrate dissolution and activation can be characterized by the K-B model, as shown in the following[

7]:

where

is the number of moles of dissolved hydrate,

is the reaction contact area,

is the activation energy,

is the intrinsic activation rate,

is the equilibrium pressure. The K-B model takes into account the influence of temperature-pressure equilibrium curves during hydrate dissolution and the influence of reaction contact area.

According to the literatures, the K-B model is based on a statistical experiment of each phase of hydrate at the equilibrium state in a sealed container under approximately steady-state conditions, by reducing pressure or increasing temperature. And calculated the dissolution rate of hydrates within steady-state conditions. The methods did not fully consider the effect of the thermal fluid injected into the hydrate. Therefore, the reaction rate

in the literature is a fixed value after fitting, but in fact the reaction rate changes with the temperature gradient, which cannot be calculated from the experiments. Therefore, DDF-LBM can be used to intuitively count the contact area during dissolving, and according to the average pressure of the lattices during dissolving, the change of reaction rate

as the hydrate saturation decreases can be given, which means that, this change has relationship with the hydrate saturation in this model. The dissolved and dissolving lattice can be illustrated in the

Figure 2, including the reacting boundaries.

The undissolved grids shown in

Figure 2 are the equations shown in the first-row of Eq. (9), that is, the current grids temperature have not reached the equilibrium condition. The dissolving grids shown in

Figure 2 are those in the second and third rows of Eq. (9), that is, the current grids satisfied the equilibrium condition, but the accumulated energy does not satisfy the phase transition condition. These grids maintain solid properties, and their contact boundaries with the flow grids in the pores are the activation contact areas

, as shown by the red lines in the

Figure 2. The dissolved grids shown in

Figure 2 are those in the fourth-row of Eq. (9), that is, the current accumulated energy of these grids was over the limit of heat absorption entropy. Then those grids will alter from solid into fluid, and being parts of collision calculation of fluids. Then the fluid-solid boundary evolutions with the hydrate activation reaction are realized.

2.4. Lattice Boltzmann Method for Unstable Simulation

The simulation of hydrate dissolution in porous media is a process with approximately steady-state flowing and non-steady-state heat transferring, so the statistical method of the model calculation results needs to be revised[

19]. The average permeability

of the porous structure can be calculated using the differential form of Darcy's law, as shown in Eq. (12). The efficient thermal conductivity

can be calculated using the differential form of the energy equation, as shown in Eq. (13). The model in this paper can be verified using experimental results in the literatures, and the Eq. (14) (K-B model) can be used to solve the reaction rate

.

In the simulation of dissolution process, the pressure, velocity and temperature fields at the entire physical microscale are non-uniform. Therefore, it is impossible to directly using import and export statistics results to calculate. It is necessary to divide the inhomogeneous physical fields into regions so that the calculation results can be more approximately stable. In this study, the simulation area will be divided into eight statistical areas of equal size. And use the above equations to calculate the permeability and efficient thermal conductivity in each area, then average them. This can improve the impact of unsteady state in the physical field within the models, making the calculation results more accurate.

3. Results and Discussions

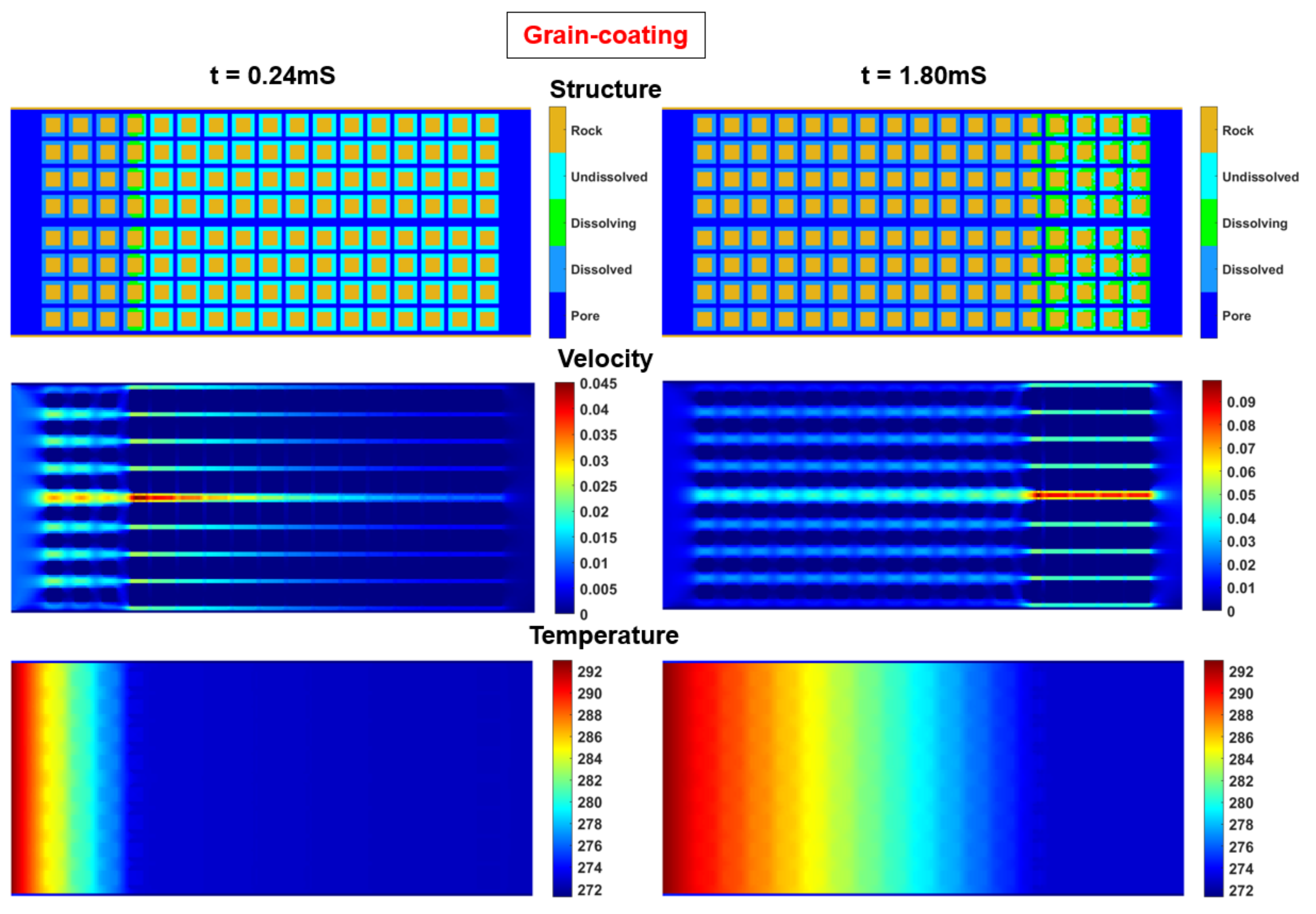

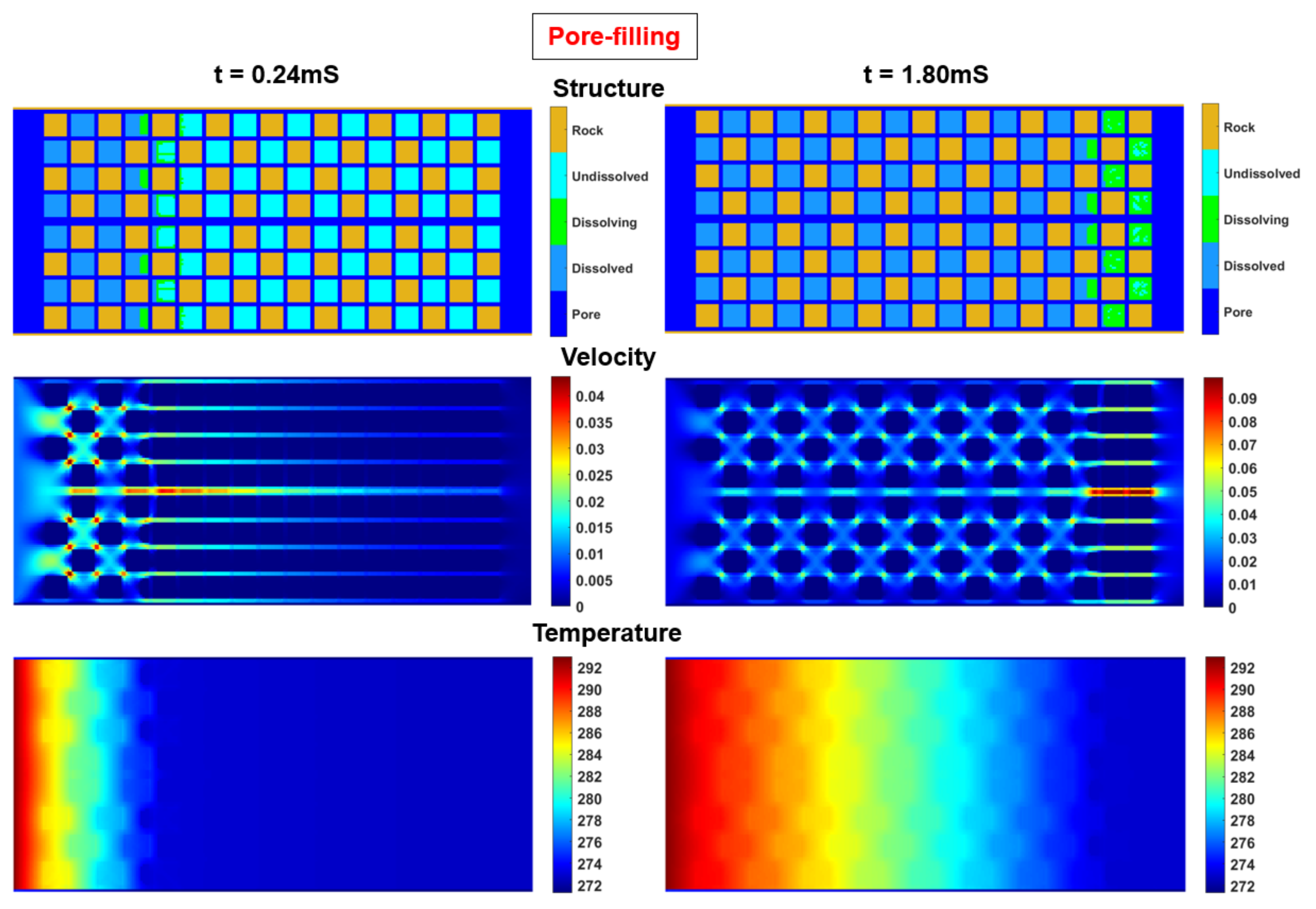

Set the left side as the hot fluid inlet and the right side as the hot fluid outlet. Other parameters and boundaries can be set as Tab. 1, including initial conditions and different lattices[

20,

21]. Set the hydrate totally dissolved as the ending point. Simulate the pressure, velocity and temperature at different times in the porous model. Fully consider the impact of fluid-solid boundary behaviors after hydrate dissolution. The calculation results of the structural field, velocity field, and temperature field at some time nodes are as follows.

Table 1.

Parameters used in the DDF-LBM model with TFMC.

Table 1.

Parameters used in the DDF-LBM model with TFMC.

| Parameters |

Symbols |

Value with Units |

| Kinetic viscosity |

|

1×10-6 m2/s |

| Heat diffusivity of liquid |

|

1.31×10-7 m2/s |

| Thermal conductivity of rock |

|

2.0 W/m/K |

| Thermal conductivity of hydrate |

|

9.0 W/m/K |

| Thermal conductivity of liquid |

|

0.55 W/m/K |

| Density of hydrate |

|

920 kg/m3

|

| Density of rock |

|

2650 kg/m3

|

| Specific heat of rock |

|

1.0 kJ/kg/K |

| Specific heat of hydrate |

|

2.08 kJ/kg/K |

| Inlet temperature |

|

293 K |

| Phase change temperature |

|

274 K |

| Original temperature |

|

271 K |

| Inlet velocity |

|

0.1 m/s |

| Original pressure |

|

2.3 MPa |

| Length scale |

|

2×10-7 m |

| Time scale |

|

2×10-8 s |

| Height |

|

10×10-7 m |

| Activation energy |

|

81 kJ/mol |

| Reaction heat absorption |

|

52 kJ/mol |

| Phase equilibrium curve |

|

|

Figure 3.

Cloud maps of structural field, velocity field, and temperature field at 0.24mS and 1.80mS.

Figure 3.

Cloud maps of structural field, velocity field, and temperature field at 0.24mS and 1.80mS.

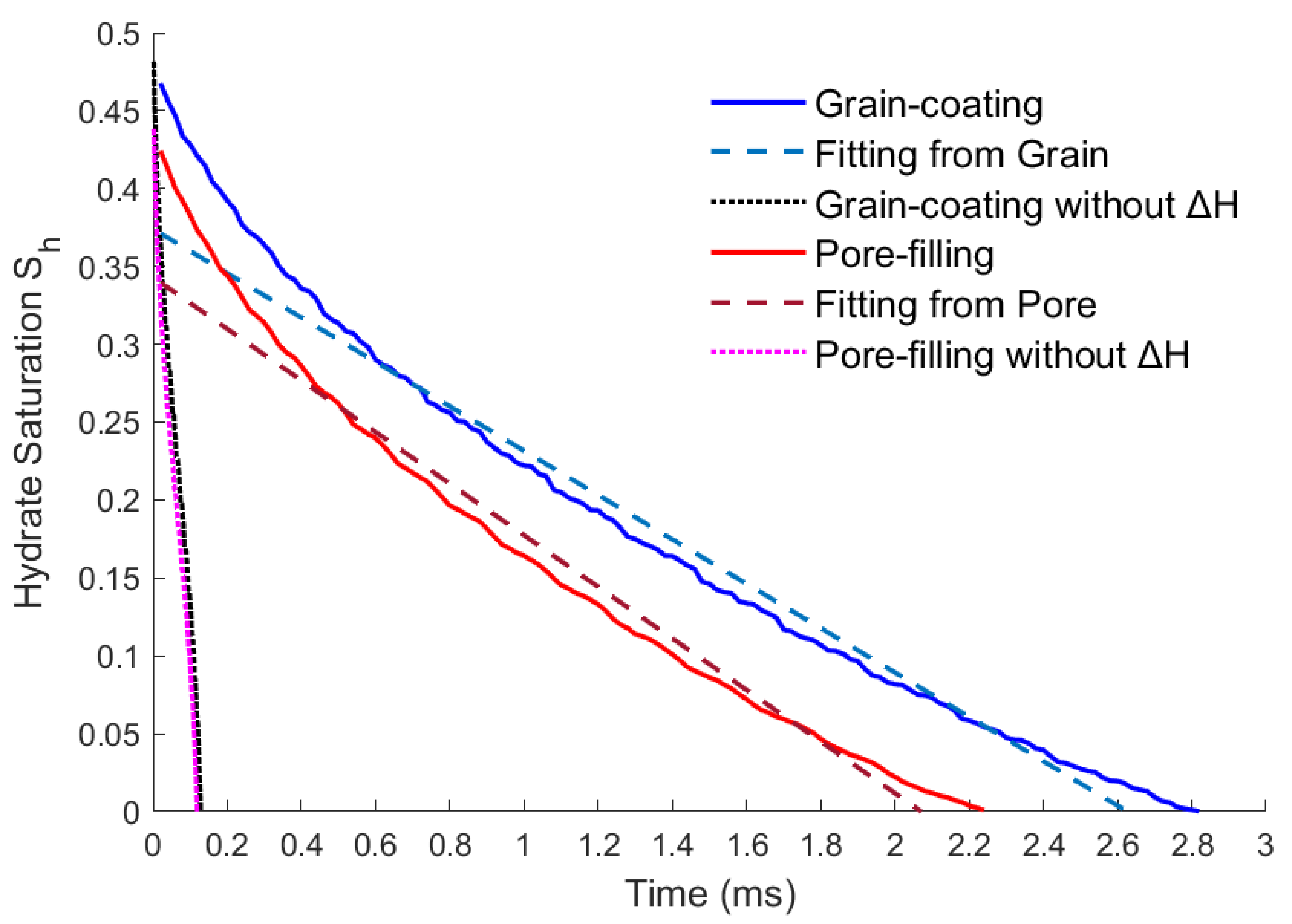

3.1. Simulation Verifying by Reaction Rate

Changing the hydrate storage state may not change the dissolving rate much.

Figure 4 shows the variation of residual hydrate saturation over time for two different pore structures.

is the absolute saturation of hydrate in the pores and

.

and

are the solid hydrate volume and pore volume respectively.

Although the initial hydrate saturations of the grain-coating and the pore-filling types are different, their dissolution rates change in the same way because of the same boundary conditions of inlet velocity and temperature. By linear fitting the curves in

Figure 4, the hydrate dissolution rates of the two models can be approximately described by the following equations.

According to Eq. (15), the fitting results of the hydrate dissolution rate

of the two models can be directly obtained as below.

Substituting the hydrate dissolution rate

into Eq. (14), we can obtain the hydrate activation reaction rate per contact area simulated by LBM, as known as

. The activation reaction area

can be obtained by counting the solid-liquid phase field boundary in

Figure 2. The temperature difference

in Eq. (17) comes from the temperature difference between the inlet

and the boundary

in Tab. 1.

The simulation results in Eq. (17) are familiar with the experimental results in the literatures[

22]. However, the experimental condition in the literature is to directly heat the upper surface of the hydrate in a sealed container, the thermal fluid is not injected into the porous structure with hydrate. Therefore, the hydrate dissolution reaction rate caused by the injection of hot fluids simulated by LBM must be greater than the experimental results, but not much more. It is further proved that the DDF-LBM simulation method that comprehensively considers TFMC in this paper can approximately and accurately describe the hydrate dissolution process when thermal fluid is injected into porous media.

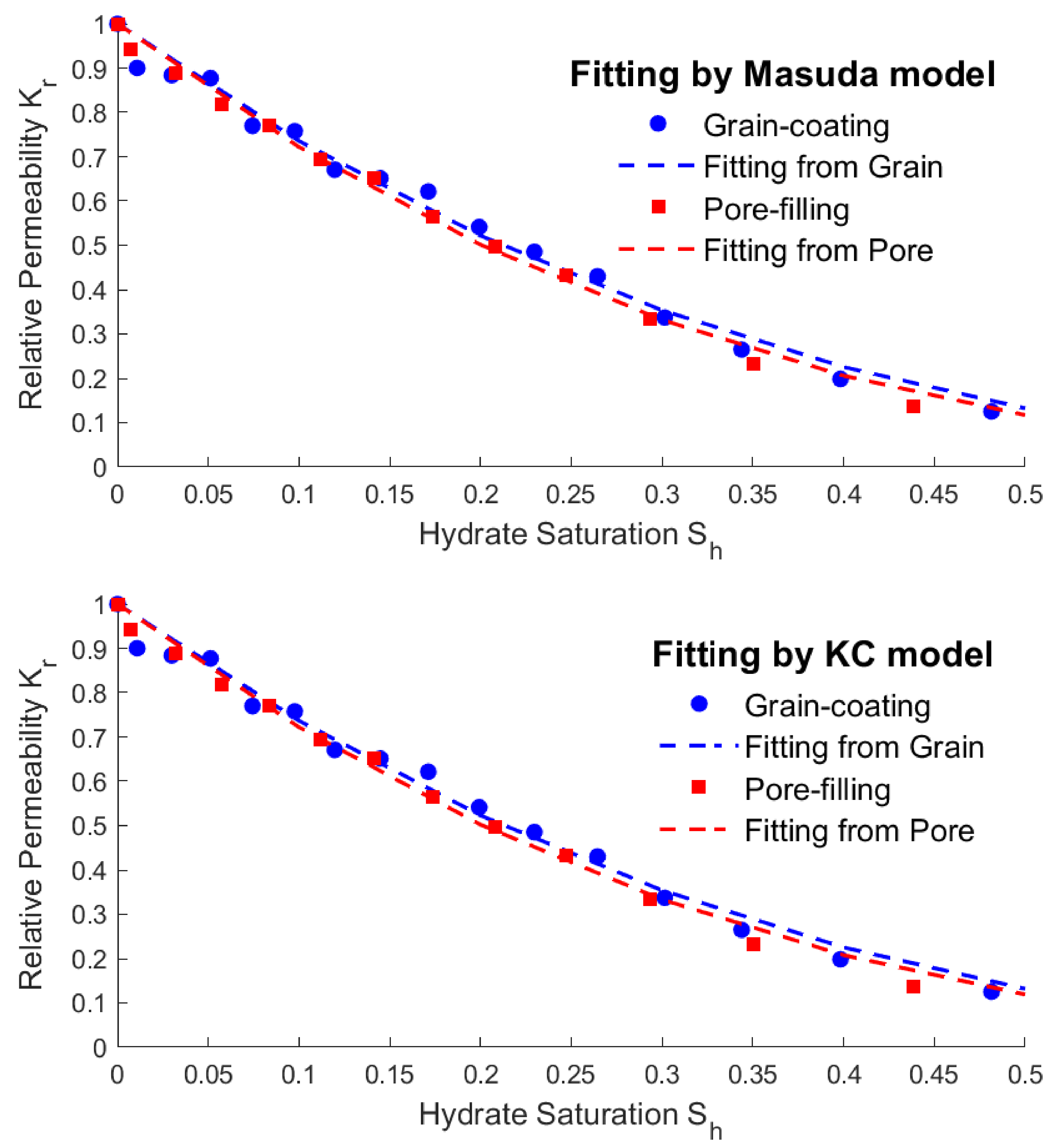

3.2. Relationship between Saturation and Permeability

Firstly, the solid boundary state in the model under different saturation conditions will be retained, as shown in the structure map in

Figure 3. Then, the velocity and pressure field distributions under different solid boundary conditions were calculated using the BLGK method with 8 partitions method. The approximate stable average permeability

is calculated using Eq. (12). The average permeability of the grain-coating model increased from 14mD at undissolved state to 116mD at totally dissolved state. The average permeability of the pore-filling model increased from 14mD at undissolved state to 107mD at totally dissolved state. Then the average permeability was processed as dimensionless relative permeability

, and it was found that the hydrate saturation

and relative permeability

basically conformed to the power exponential relationship. According to relevant literatures, there are two typical models: Masuda model (18) and KC model (19), which can describe the power exponential relationship[

23,

24]. The fitting results based on the calculation results are shown in the following figures and equations.

Figure 5.

Fitting results between hydrate saturation and relative permeability by Masuda model and KC model.

Figure 5.

Fitting results between hydrate saturation and relative permeability by Masuda model and KC model.

From the fitting results above, the average permeability calculation results of different saturations can be obtained by using the steady-state LBM. The fitting results of the Masuda model and KC model are basically the same, which is consistent with the conclusions in the literatures. This method can be used to accurately given the expression of permeability by saturation and provide accurate results for other coupled parameters.

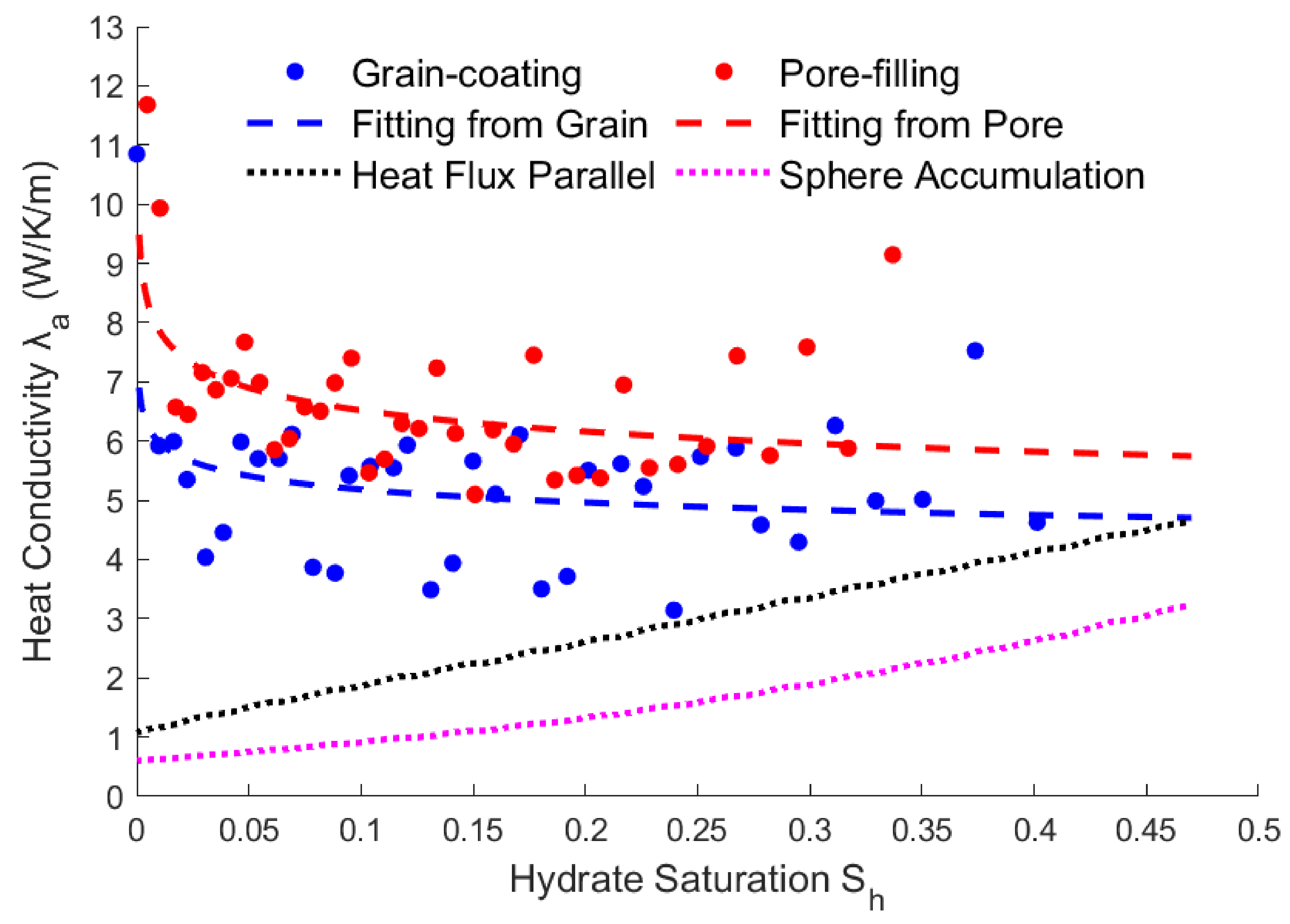

3.3. Relationship between Saturation and Heat Conductivity

The effective thermal conductivity can only be calculated using a non-steady-state method, because Eq. (3) is a partial differential equation. Eq. (13) can be used to calculate the effective heat conductivity at different hydrate saturation. According to the literatures[

25,

26], if the medium of the porous is single or has a simple distribution, the average thermal conductivity can be directly calculated using the multi-component percentage weight of hydrate, rock, and fluid. However, the porous structure of hydrate reservoirs is relatively complex. So, the non-steady-state calculation results and component average calculation results of different structures are compared in the figure below.

Figure 6.

Calculation results between hydrate saturation and effective heat conductivity.

Figure 6.

Calculation results between hydrate saturation and effective heat conductivity.

The simulation results were shown in

Figure 5, although the effective thermal conductivity fluctuates as the saturation decreases, the overall result gradually increases as the saturation decreases. The effective thermal conductivity of the grain-coating hydrate is smaller than that of the interval hydrate. Fitting the above calculation results, it is found that they can be approximately fitted by a power exponential equation, and the results are shown as follow.

Compared with the results of heat flux parallel and sphere accumulation, the rules are just the opposite. The reason is that, after the hydrates are reduced, the permeability increases, resulting in an increase in flow rate. And then the heat convection rate increases, resulting in an increase in the effective thermal conductivity.

3.4. Relationship between Saturation and Reaction Rate

Calculate the average pressure

at the activation reaction area, what is shown in

Figure 2, then we can get the intrinsic activation reaction rate at different dissolution time or hydrate saturation by Eq. (14). The simulation results are shown as follow.

It can be seen from

Figure 7 that the intrinsic reaction rate gradually decreases with the decrease of saturation. Comparing the simulation results of two different structures, the intrinsic reaction rate of the grain-coating type hydrate is smaller than that of the pore-filling type. By fitting the results, the expressions of the intrinsic reaction rate can be obtained.

Kim et al. used experimental methods to obtain the intrinsic activation reaction rate

. However, Clarke et al. used a combination of experimental and numerical simulation methods to prove that Kim's results may be too large[

27,

28]. The fitting results in Eq. (21) show that if thermal fluid injection dissolution was considered,

will be larger and related to the saturation

.

Compared with the fitting results obtained above, the K-B model results are too large because the actual reaction contact area under micro-scale conditions is not fully considered. Not all contact boundaries between solid hydrates and fluids, only the contact boundaries between hydrates and fluids in the activation reaction are the actual reaction contact areas

.Clarke's simulation results obtained a fixed value because it did not fully consider the influence of temperature gradient under micro-scale conditions. Although the inlet temperature

remains unchanged during the dissolution process, the front of the activation reaction gradually advances as the hydrate dissolves. By comparing the structural field and temperature field results at different times in

Figure 3, it is shown that the distance between the dissolving lattices (green) and the entrance gradually increases as the saturation decreases, so the temperature gradient of the model decreases as the saturation decreases. Therefore, the intrinsic reaction rate of hydrates is actually correlated with the hydrate saturation, and the K-B model can be further modified.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, the DDF-LBM was used to simulate the dissolution of natural gas hydrate caused by the thermal fluid injection under micro-scale porous model. The simulation results were solved by unsteady difference method and it was found that the dissolution rate of thermal fluid injection was higher than that of surface heat absorption only. According to the simulated velocity field, pressure field, temperature field and structure field results, the key physical parameters under different hydrate saturation conditions were calculated, and their exponential fitting equations were given. The fitting results were compared with those from other literatures, which further proved that the DDF-LBM was feasible and realized the TFMC fully multi-field coupled dynamic simulation of thermal fluid injection to dissolve natural gas hydrates. Based on the above results, the following conclusions can be drawn.

(1) When DDF-LBM simulates conjugate convection, the relaxation frequency of the thermal lattice in the pores needs to be modified to consider the simultaneous existence of thermal diffusion and thermal convection. The modification is necessary when simulating forced convection heat transfer, otherwise the calculated results will be much smaller. When describing the changes in fluid-solid boundaries, we must first determine whether the current solid hydrate lattices have reached the P-T phase equilibrium condition, and then determine whether the cumulative internal energy absorbed by the current lattice exceeds the heat required for its reaction. The lattices that have reached phase equilibrium conditions but do not satisfy the cumulative endothermic conditions are dissolving solid hydrate lattices, and their contact boundaries with the flowing lattices are the reacting contact areas in the K-B model. The reaction contact area can be directly obtained from the structural field simulation results, so that the effect of dissolution endothermicity on internal energy transfer in the convective heat transfer process can be described at micro-scale.

(2) By comparing the results of heating dissolution experiments in closed containers in other literature, the hydrate dissolution rate under the thermal fluid injection conditions simulated in this paper is slightly higher than the result of only heat absorption on surface. This is because the hydrate reaction rate calculated from the experiments in the literature was based on surface heat diffusion only, and did not take into account the actual situation of thermal fluid flowing under the porous structure of the reservoir. Therefore, the activation reaction rate calculated by DDF-LBM is more consistent with the real reservoir situation. Compared the dissolution rates of the grain-coating type and the pore-filling type, although the hydrate structures and initial saturations of the two models are different, their dissolution rates are basically the same due to the same boundary conditions of injection flow velocity and temperature. It is shown that the DDF-LBM simulation with TFMC multi-field coupling in this paper can approximately and accurately describe the hydrate dissolution process when thermal fluid injected into porous media.

(3) The modified expressions of the key physical parameters of TFMC multi-field coupling can be obtained, by fitting the hydrate saturation with the average permeability, effective thermal conductivity and intrinsic reaction rate. The fitting results show that the parameters’ trending of two different storage structures are the same. The average permeability increases as the saturation decreases, and the relative permeability has an exponential relationship with saturation. The effective thermal conductivity increases slightly with decreasing saturation and increases substantially when most of the hydrates are dissolved. Therefore, there is an approximate linear or exponential relationship between the effective thermal conductivity and the saturation, and a power exponential equation was used for fitting in this paper. The intrinsic reaction rate decreases with decreasing saturation, which is different from the fixed value given by the K-B model in the literature. This is because the model does not fully consider the impact of temperature gradient and reaction contact area on the results at micro-scale, so the K-B model can be further modified. The above modified expressions of key parameters can provide necessary references for simulating the real-time full coupling of thermal fluid injection into hydrates under macros-scale conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, analysis and writing, Zhengyi Li; Methodology and supervision, Zhiyuan Wang; resources and validation, Hongfei Ji. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NSFC, grant No. 51974350 and No. 51991363.

Data Availability Statement

The original codes for this research can be found online.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, Z., Zhang, Y., Peng, Z., Shan, Z., Sun, B., & Sun, J. (2022). Recent advances in methods of gas recovery from hydrate-bearing sediments: A Review. Energy & Fuels, 36(11), 5550-5593. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Sun, B., Wang, Z., Gao, Y., & Li, H. (2019). Coupled heat and mass transfer model of gas migration during well cementing through a hydrate layer in deep-water regions. Applied Thermal Engineering, 163, 114383. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Liao, Y., Zhang, W., Sun, B., Sun, X., & Deng, X. (2018). Coupled temperature field model of gas-hydrate formation for thermal fluid fracturing. Applied Thermal Engineering, 133, 160-169. [CrossRef]

- Rathnaweera, T. D., Wu, W., Ji, Y., & Gamage, R. P. (2020). Understanding injection-induced seismicity in enhanced geothermal systems: From the coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical-chemical process to anthropogenic earthquake prediction. Earth-science reviews, 205, 103182. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., Yin, X., Barrufet, M., & Killough, J. (2021). Lattice Boltzmann simulation of phase equilibrium of methane in nanopores under effects of adsorption. Chemical Engineering Journal, 419, 129625. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Hou, J., Zhao, H., Liu, X., & Xia, Z. (2018). A method to recover natural gas hydrates with geothermal energy conveyed by CO2. Energy, 144, 265-278. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. C., Bishnoi, P. R., Heidemann, R. A., & Rizvi, S. S. (1987). Kinetics of methane hydrate decomposition. Chemical engineering science, 42(7), 1645-1653. [CrossRef]

- Moridis, G.J. (2014). User's manual for the hydrate v1. 5 option of TOUGH+ v1. 5: A code for the simulation of system behavior in hydrate-bearing geologic media.

- Karani, H., & Huber, C. (2015). Lattice Boltzmann formulation for conjugate heat transfer in heterogeneous media. Physical Review E, 91(2), 023304. [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y., & Rao, Z. (2015). Lattice Boltzmann simulation for solid–liquid phase change phenomenon of phase change material under constant heat flux. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 86, 197-206.

- He, Y. L., Liu, Q., Li, Q., & Tao, W. Q. (2019). Lattice Boltzmann methods for single-phase and solid-liquid phase-change heat transfer in porous media: A review. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 129, 160-197. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Zhang, C., Zhang, K., Zhang, L., Yao, J., Sun, H., & Yang, Y. (2019). Pore-scale investigation of methane hydrate dissociation using the lattice Boltzmann method. Water Resources Research, 55(11), 8422-8444. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y., Kneafsey, T. J., Hou, J., Zhao, J., Liu, C., Guo, T., … & Bai, Y. (2022). Relative permeability of gas and water flow in hydrate-bearing porous media: A micro-scale study by lattice Boltzmann simulation. Fuel, 321, 124013. [CrossRef]

- Ross-Jones, J., Gaedtke, M., Sonnick, S., Meier, M., Rädle, M., Nirschl, H., & Krause, M. J. (2021). Pore-scale conjugate heat transfer simulations using lattice Boltzmann methods for industrial applications. Applied Thermal Engineering, 182, 116073. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Yin, Z., Khan, S. A., Li, S., Li, Q., Liu, X., & Linga, P. (2024). Path-dependent morphology of CH 4 hydrates and their dissociation studied with high-pressure microfluidics. Lab on a Chip, 24(6), 1602-1615. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Xu, Q., Liu, Z., & Shi, L. (2022). Pore-scale study of the multiphase methane hydrate dissociation dynamics and mechanisms in the sediment. Chemical Engineering Journal, 430, 132786. [CrossRef]

- Woods, L.C. (1993). An introduction to the kinetic theory of gases and magnetoplasmas. Oxford University Press.

- Li, J., Liang, Z., Wang, Z., & Bao, W. (2020). Molecular dynamics simulation of decomposition of methane hydrate and interfacial characteristics in nanostructure region. International Journal of Thermophysics, 41, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Guo, B., Zhang, P., & Zhang, H. (2022, July). Mathematical modeling of heat transfer from geothermal reservoirs to gas hydrate reservoirs. In Applied Energy Symposium: MIT A+ B. [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, A.A. (2019). Lattice Boltzmann Method (2nd edition): Fundamentals and Engineering Applications with Computer Codes. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Gaedtke, M., Abishek, S., Mead-Hunter, R., King, A. J., Mullins, B. J., Nirschl, H., & Krause, M. J. (2020). Total enthalpy-based lattice Boltzmann simulations of melting in paraffin/metal foam composite phase change materials. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 155, 119870. [CrossRef]

- Kamath, V. A., & Holder, G. D. (1987). Dissociation heat transfer characteristics of methane hydrates. AIChE Journal, 33(2), 347-350. [CrossRef]

- Masuda, Y. (1997). Numerical calculation of gas-production performance from reservoirs containing natural gas hydrates. In SPE Asia Pacific Oil & Gas Conference & Exhibition, held in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 14-16 April, 1997.

- Dai, S., & Seol, Y. (2014). Water permeability in hydrate-bearing sediments: A pore-scale study. Geophysical Research Letters, 41(12), 4176-4184. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W., Kan, A., Chen, Z., Zhang, Q., & Zhang, J. (2022). A modified Lattice Boltzmann method for predicting the effective thermal conductivity of open-cell foam materials. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, 133, 105957. [CrossRef]

- Qin, X., Cai, J., Zhou, Y., & Kang, Z. (2020). Lattice Boltzmann simulation and fractal analysis of effective thermal conductivity in porous media. Applied Thermal Engineering, 180, 115562. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M., & Bishnoi, P. R. (2001). Determination of the activation energy and intrinsic rate constant of methane gas hydrate decomposition. The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering, 79(1), 143-147. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Luo, T., Wang, L., Wang, H., Song, Y., & Li, Y. (2019). Numerical simulation of gas recovery from a low-permeability hydrate reservoir by depressurization. Applied energy, 250, 7-18. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).