1. Introduction

The aorta is the largest artery in animals and humans and modifications in its structure and/or function alters the cardiovascular system [

1]. The aortic wall has three layers: adventitia, media composed; the vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC), collagen and elastic fibers (EF) and intima (endothelium) [

2]. The mechanical properties of the aorta depend on the amount of the main components of these layers, and on the spatial organization and mechanical interactions between them [

3]. Changes in the phenotype of VSMC in the media are often present in hypertension and they underlie increases in the stiffness of the vessel. Two types of phenotypes are described in VSMC: the contractile and the secretory or synthetic. Markers of differentiation to the secretory phenotype include: a) increased cell size, b) increased extracellular matrix production which involves metalloproteinases (MMPs) and increased collagen III and fibronectin, c) increased migration, d) decreased contractile protein expression including smooth muscle actin and increased osteopontine [

4]. However, control of VSMC differentiation/maturation, and regulation of its responses to changing environmental cues, is complex and depends on the cooperative interaction of many factors and signaling pathways [

5]. Sucrose ingestion during critical periods (CP) of vessel development mighty induce inflammation and determine a change in the VSMC phenotype. Changes in the expression of MMPs during remodeling of the VSMC phenotype may also contribute to overexpression of the inflammatory cytokines [

6].

Previous papers have shown that changes in the diet, mainly low protein [

7] or high salt [

8] ingestion during gestation and during gestation and lactation underlie the development of hypertension during adulthood without exploring the role of inflammation. These periods comprise from 1 to 3 months of time. However, the effect of a shorter time lapse of only 16 days of a modified diet during the last days of lactation and the first days after weaning (rat postnatal days 12 to 28) also results in hypertension when the rats reach adulthood [

9]. This stage constitutes therefore a CP of vessel differentiation [

9]. During this CP, the rodent diet changes from rich in fat to rich in carbohydrates and the pancreas undergoes important maturation [

10]. The maturation of the pancreas is accompanied by changes in glucose and insulin concentrations in plasma which modify vascular reactivity [

11] and may induce inflammation. Variation in blood glucose and insulin concentrations are related to oxidative stress (OS), inflammation and changes in redox signaling [

12] and these might lead to changes in the VSMC phenotype in this critical period of development [

13,

14]. Therefore, changes induced by a modified diet might induce inflammation during the critical window which might program VSMC to the secretory phenotype.

Inflammatory mediators can override homeostatic processes, including the expression of MMPs that lead to changes in the phenotype of VSMC, thus determining the mechanical function of the vessels [

15]. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) causes a fundamental change from a contractile to a secretory phenotype of VSMCs. This switch enhances proliferation and production of extracellular matrix proteins which are associated with hypertrophy of the media [

16]. TNF-α and IL-1β, induce growth and/or migration of VSMCs and stimulate the production of chemokines, leading to a ‘proinflammatory’ phenotype of VSMC, that then secrete and express other proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and cell adhesion molecules [

17]. Additionally, elevated glucose ingestion as that consumed in drinking water during the critical period might induce hypertriglyceridemia [

18] and this condition promotes the secretion of many cytokines in human white blood cells and possibly in other tissues and cells [

19], which in turn modulate MMPs activity. On the other hand, cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) is an enzyme largely responsible for causing inflammation and whose inhibition is associated with hypertension. It is an inducible enzyme and it is expressed by inflammatory cells. This enzyme metabolizes the arachidonic acid (AA) to prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) which is proinflammatory and has vasoconstrictor effects [

20]. Another enzyme that contributes to inflammation is the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) which catalyzes the conversion of L-arginine to L-citrulline and nitric oxide (NO), and the excess NO acts as a proinflammatory agent [

21]. Both COX-2 and iNOS have synergistic actions promoting and maintaining key physiological functions such as the vascular function. There is also a cross talk between NO and vasoconstrictor prostanoids which decrease eNOS expression. However, the details of the cross talk between prostanoids and the iNOS-NO system and on the eNOS pathway remains unknown [

22]. Inflammation can also be induced by fatty acids such as oleic and arachidonic acid (AA) by activating toll like receptors (TLR), in particular, the TLR4 signaling pathway. TLR4 also increases COX-2 expression [

23]. Oleic acid elevation in plasma might also contribute to decrease of the eNOS and this can in turn increase systolic blood pressure (SBP) [

24].

Therefore, the aim of this paper was to study changes in the VSMCs phenotype and in the expression of MMPs in rats that received sucrose at the end of the CP, before compensatory mechanisms are established. We tested the possible involvement of the COX-2 and TLR4 pathways which are related to iNOS and eNOS. We also studied the levels of inflammatory mediators in this group of rats.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Experimental Groups

Experiments in animals were approved by the Laboratory Animal Care Committee of our Institution and were conducted in compliance with our Institution´s ethical guidelines for animal research (INCAR protocol number 20-1147).

A group of rats was given 30% sucrose in drinking water during the CP window of vessel development (postnatal days 12 to 28) and the Control (C) group received the normal diet and drinking water and the animals in both groups had the same age. All animals were fed Purina 5001 rat chow (Richmond, IN) ad libitum, and were kept under controlled temperature and a 12:12-hours light-dark cycle. Rats from at least 3 litters of 6 male animals for the C and CP groups were used for pressure measurement and other rats from at least 3 litters of 8 male animals for the CP and C groups were used for serum and tissue determinations.

2.2. Blood Pressure Measurement and Sacrifice

For SBP determinations, six 28-day old rats from 3 litters of control and CP, that were previously fasted for 12 h were weighed and intraperitoneally anesthetized with 50mg/Kg of sodium pentobarbital and allowed (Anestesal; Pfizer, Mexico) to reach a state of surgical anesthesia. An intra-tracheal tube was placed for respiration. A catheter filled with Hartmann solution: heparin (3:1) was placed in the left cranial carotid artery and connected to a blood pressure transducer to a previously calibrated polygraph VR-6 simultrance recorder (Model M4-A, Electronics for Medicine/Honeywell, White Plains, NY, USA). Five min of recuperation after surgery were given before the register was obtained. The mean of five independent determinations was calculated.

Another group of rats were killed by decapitation after overnight fasting (12 hours). The blood was collected, and the serum was separated by centrifugation at 600 g during 15 min at room temperature and stored at –70°C until needed. Thoracic aortas were obtained and cleaned from blood and adipose tissue. Pools of 3 aortas from C and CP rats were done for the western blot analysis.

2.3. Biochemical and Physiological Determinations

Glucose concentration was assayed using an enzymatic SERA-PAKR Plus from Bayer Corporation (Bayer Corporation, Sées, France). Serum insulin was determined using a commercial radioimmunoassay (RIA) specific for rat (Linco Research, Inc. Missouri, USA); its sensitivity was of 0.1 ng/mL and intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 5 and 10%, respectively. The HOMA-IR was calculated from the fasting glucose and insulin concentrations. The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance HOMA-IR is used as a physiological index of insulin resistance and it is determined from the fasting glucose and insulin concentrations by the following formula: (insulin (µU/mL) × glucose (in mmol/L)/22.5). Triglycerides (TGs) were determined by commercially available procedures (Ran-dox, Laboratories LTD, Antrim, United Kingdom).

2.4. Histological Analysis

Cross sections (5 µm) of C and CP aortas were processed by paraffin inclusion. They were stained by the conventional method for Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE) staining or immunolocalization for COX-2, TLR4, iNOS and eNOS. HE staining, 10x, 20x or 25x images were obtained around the ring from which the total image of the ring was reconstructed (n=10), superimposing the photographs at the coincidence points Using an Olympus BX51 microscope, with integrated camera [Q-IMAGING, Micropublisher 5.0 RTV (Real-Time Viewing)]; coupled to Image-Pro Premier software, version 9.0, (Media Cybernetics). The average value of the wall thickness was obtained from 20 measurements at equidistant points of each ring (n=10). Total lumen area (n=10) and total wall area (n=10) were measured. From the same sections with HE staining, images in a gray tone were acquired, using a Floid Cell Imaging Station (Life Technologies), with the color channel in relief phase since changes can be more clearly appreciated. Approaches are presented in which the differences in the structure of the aortic wall of group C and CP are distinguished in greater detail.

For the immunostaining for COX-2, eNOS, iNOS and TLR4, the aortic rings of each of the rats were preserved in 10% formalin in a 1:20 ratio. The immunohistochemistry was processed according to the conventional histological technique. The samples were incubated with the primary monoclonal antibodies at a final dilution of 1:20 for all antibodies for COX-2 sc-19999, IgG1, iNOS (c-11) sc-7271, IgG1k, and eNOS (a-9) sc-376751, IgG2ak, TLR4 (25) sc-293072. The staining was revealed with DAB (3′3′-Diaminobenzidine), contrasted with hematoxylin. The histological sections were analyzed with a Carl Zeiss light microscope (66300 Model) equipped with a 9-megapixel Cool SNAP-Pro digital camera at a 25× magnification. The photomicrographs were analyzed by densitometry using Sigma Scan Pro 5 Image Analysis software (Systat Software Inc. San Jose, CA, USA), and the parameters of analyses in the software were adjusted and remained constant for each of the antibodies. An average of five sections of endothelium and the muscular media layer in each sample were examined. The density values are expressed as pixel area units.

2.5. Western Blott Analysis (MMP2, MMP9, SMA, β-Actin)

Aortas were homogenized in a lysis buffer plus protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. The homogenate was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 ◦C; the supernatant was separated and stored at −70 ◦C until use. The Bradford method was used to determine the total proteins [

26].

Protein (50 μg) was separated on an SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Blots were blocked 1 h at room temperature using Tris-buffered saline (TBS)-0.01% Tween (TBS-T 0.01%) plus 5% non-fat milk. The membranes were incubated overnight at 4 ◦C with rabbit primary polyclonal antibodies -Actin (sc-81178), metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2; sc-13595), metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9; sc-393859), and Smooth Muscle Actin (SMA; sc-53142) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). All blots were incubated with Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; sc-365062) antibody as a loading control. Images from films were digitally obtained using a GS-800 densitometer with the Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. Hercules, CA, USA) and they are reported as arbitrary units (AU).

3.4. Total Fatty Acid (TFA) Determination

For the extraction and derivatization of the fatty acids (FA), 50 µg of aorta homogenate were used according to the method described by Folch [

25], in presence of 50 µg of margaric acid (C17:0) as an internal standard. Then, 1 mL of a saline solution (0.09%) was added and mixed for 15 s, and then 2 mL of a methanol chloroform mixture (2:1 vol/vol) plus 0.002% BHT were added and centrifuged at 3000 rpm by 5 min. This step was repeated twice, and the organic phase was recovered and evaporated under a gentle current of nitrogen (N

2). FAs were trans esterified to their FA methyl esters by heating them at 90 °C for 2 h with 2 mL of methanol plus 0.002% BHT, 40 µL of H

2SO

4, and 100 µL of toluene. Afterward, 1 mL of the saline solution and 4 mL the hexane were added, and the mixture was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min. The hexane phase was recovered and evaporated under a gentle current of N

2. The evaporated residue containing the FA was suspended in 100 µL of hexane, and 4 µL was injected into the chromatograph. The FA methyl esters were separated and identified by gas chromatography FID in a Carlo Erba Fratovap 2300 chromatograph equipped with a capillary column packed with the stationary phase HP-FFAP (description: 30 m length × 0.320 mm diameter × 0.25 µm film) and fitted with a flame ionization detector at 210 °C with helium as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.2 mL/min. The areas under the peaks were calculated using Chromatograph software version 1.1 coupled to the gas chromatograph. The identification of each FA methyl ester was made by comparing their retention time with their corresponding standard.

2.6. Determination of Inflammatory Mediators

The Elisa kit ab100768 -IL-1β for Rat, the Elisa Kit ab 100772 Rat IL-6 and Elisa Kit ab100785 TNF alpha Rat Simple Step, were used in a double-antibody sandwich ELISA method to measure inflammatory cytokines in rat serum. The anti-rat IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, antibodies were coated on an enzyme plate. During the experiment, the rat IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, in the sample or standard product were bound to the coated antibody and the free components were washed away. Biotinylated anti-rat IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, antibodies and horseradish peroxidase labeled with streptavidin were successively added. The anti-rat IL-1β, IL-6, or TNF-α antibody were bound to the coated antibody to the rat IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and the biotin specifically bound to avidin to form an immune complex, while the free components were washed away. Color substrate (TMB) was added, and it became blue under the catalysis of horseradish peroxidase and became yellow with the addition of termination solution. The concentration of IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α in the sample were proportional to the OD450 value. The concentration of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α in the sample were calculated by drawing standard curves.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard errors. The type of distribution was evaluated by means of the Shapiro-Wilks test. Statistical analysis was done by Student’s t test, using the Sigma Stat program version 15 (Jandel Scientific). Differences were considered statistically significant when p<0.05.

4. Discussion

Changes in the diet during early development program organisms to develop hypertension when they grow into adulthood [

9]. Therefore, epigenetic cues might appear at this stage that result in the development this disease later in life. In this sense, essential hypertension, as other heart diseases, has been reported to be programmed since childhood [

29,

30,

31,

32]. Moreover, there is a possible association between SBP levels at childhood and hypertension in the adult [

32]. Therefore, changes occurring at early stages of life might predispose to development of diseases in adult life rendering important the study of critical periods [

33]. In this study we evaluated the inflammatory pathways that may lead to morphological changes in the aortas from rats receiving sucrose during a CP of vascular development.

We had previously reported that the effect of the ingestion of a sucrose rich diet during a CP of vessel development that lasts for only 16 days (from postnatal day 12 to 28), comprising a period in which pups are still suckling milk from the mother and a period in which they are feeding independently, results in hypertension in adulthood. During this period there is an important change in the diet from a high lipid diet to a carbohydrate rich diet. The increase in SBP was accompanied by elevated levels of NO, reduced expression of eNOS and OS in the thoracic aortas [

9].

When studying the changes caused by the sucrose ingestion at the end of the critical period that might underlie the epigenetic cues, our group reported that the pups that received sucrose during this CP had a decreased body weight and there were no changes in serum glucose or insulin while TG were increased. These findings were corroborated in the present study. The decrease in body weight in sucrose fed rats even when the diet contained more Kcal could be due to excess activity of the pups as was discussed [

28]. The lack of changes in the glucose and insulin concentration might be the consequence of the short time of exposure to sucrose. The increase in triglycerides results from the high exposure to sucrose [

27].

At this stage, SBP was elevated and there was a diminished expression of eNOS in the aorta. This elevation of SBP that was also found in the present study is transient since in a previous paper we reported that at 4 months of age, rats receiving sucrose had a comparable SBP as C rats and that at this point of development arterial pressure began to rise leading to hypertension at 6 months of age [

9]. Therefore, this increase at the end of the critical period might set an epigenetic cue that is lost during the next months of development but programs the arterial contraction in adulthood [

33]. At this early stage, there was also a decrease and of the total non-enzymatic antioxidant capacity, and elevation of lipoperoxidation [

28].

Remodeling of vessels which might underlie hypertension in adults is characterized by an elevation of the stiffness of large arteries which decreases their ability to modify the pulsatile pressure to a continuous pressure and flow in arterioles. Intrinsic stiffness and arterial geometry of the vessel underlie arterial compliance [

34,

35]. Cellular processes that determine these characteristics include altered VSMC growth, migration, differentiation and increased extracellular matrix abundance [

36]. Regarding changes in the phenotype of the VSMC when rats receive sucrose during the CP window, we previously reported that there was a decrease of the lumen of the arteries and the media an adventitia were diminished in diameter and muscle fibers were discontinuous when the animals reached the adult stage. There was a decreased expression of α-actin and surprisingly a decrease in the expression of MMP-2 and -9, suggesting compensatory mechanisms to the changes in the aortas at the early stage were activated [

27]. These results also might indicate that vessels from rats that received sucrose during early stages might reach a new stable stationary state with a low renewal of EF. This surprising finding which contradicts the expected previously results of an increase in the expression of MMPs motivated the study on the possible increase on the expression of these proteins earlier, possibly the end of the altered diet period, in which the arteries are programmed to develop the altered phenotype underlying the development of hypertension in the adult. It has been previously reported that the expression of active MMPs is absent or very low in mature and quiescent vessels in contrast to the high expression, secretion and activation of these enzymes found in the tissues undergoing vascular remodeling which might be happening at the end of the critical period of vessel development.

In the present study we found that the morphology of the aortas from rats that received sucrose during the CP is altered and that they show eccentric hypertrophy which is characterized by dilatation of the lumen of the artery (

Figure 1). Eccentric hypertrophy is due to an increase in the overall size of myocytes that results from in-series increase in the contractile proteins. Eccentric hypertrophy is usually the result of volume overload and leads to diastolic stress [

37]. In our model this type of hypertrophy was accompanied by an increase in smooth muscle mass. Vascular stiffness results from fibrosis, which was not observed in the aortas from our experimental groups and extracellular matrix remodeling. Fibrosis was probably not found due to the short lapse of time that comprises the critical period of vascular function (only 12 days).

It is possible that some of the structural changes that we observe in the images shown in

Figure 1 are associated with the presence of hemodynamic shear stress that could be present in the animals that received sucrose during the CP. Shear stress, the frictional force acting on the inner surface of blood vessels in the direction of blood flow, is linked to elevated blood pressure. Shear stress may be involved in the development of changes in the endothelium and may regulate vascular caliber, cell proliferation and inflammation of the vessel wall (vascular remodeling) in hypertensive patients and in several animal models, leading to alterations in the structure and function of blood vessels [

38]. Furthermore, the presence of aneurysms observed in the aortas of CP animals (marked with white arrows in the images in

Figure 1) also coincides with what has been reported by other works that indicate that in the presence of shear stress favors the development of aneurysms [

39,

40].

Histological changes in the aortas and alterations in VSMC phenotype of the vessels at the end of the sucrose ingestion period may be due to underlying inflammatory process which has not been evaluated. The role played by inflammation on the change of the VSMC phenotype, and the possible inflammatory pathways involved have not been studied and they were the aim of the present paper. High levels of glucose and insulin induce an inflammatory process [

14]. Although the serum levels of these variables were not increased at the end of the CP, there is exposure to the elevated glucose concentration in the drinking water. Hypertriglyceridemia may result from excess glucose consumption [

18] and it has been reported that the rate of TG fatty acid clearance is suppressed by cytokines, notably TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β, increasing this condition as our data shows [

41]. In this paper we analyzed the role of some inflammatory pathways including those mediated by COX-2, and TLR4. COX-2 catalyze the conversion of AA to prostaglandins and thromboxane [

42]. These lipid mediators play important roles in inflammation and vasomotricity [

42]. We found that COX-2 was increased in vessels from rats that received sucrose during the CP. There is interaction between the COX-2, iNOS and eNOS systems. We found a decrease in iNOS but a decrease in eNOS expression in aortas from rats that received sucrose during the CP. COX-2 metabolizes AA to PGE

2 and is associated with changes in cytokine expression such as TLR4 is a pattern recognition receptor that plays a central role in the innate immune response. Activation of the endothelial TLR-4, contributes to vascular inflammation [

43]. TLR-4 expression is activated by saturated fatty acids as oleic acid and it can also be triggered by OS through oxLDL and oxidized phospholipids with the participation of nuclear factor kappa B [

44]. OS is increased in the CP window [

27]. Activation of TLR4 induces nuclear factor kappaB activation and expression of COX-2 [

23]. Moreover, disturbed blood flow at arterial branches and curvatures causes shear stress and modulates endothelial function and predisposes the region to endothelial inflammation possibly through the participation of TLR4 [

43]. Alterations in TLR4 activity can exert control over the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and type 1 interferons [

45]. We found that TLR4 and oleic acid were increased in CP, and could indicate the participation an important function of this protein in the inflammation process in the critical period (

Figure 3,

Table 1).

It has been reported that lipids have different biological functions and that changes in their concentrations can be linked to the secretory program associated to senescence which consist in the production of pro-inflammatory factors and extracellular matrix remodeling factors [

46]. Particularly, hypertriglyceridemia is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease and is linked to vascular dysfunction and with an exacerbated inflammatory response [

34]. In this sense, oleic acid contributes to increase SBP through the inhibition of the eNOS pathway and favors the increase of the iNOS. Our results showed that this fatty acid was increase in the CP group and this could be associates with the increase of systolic blood pressure. Also, the iNOS and COX-2 pathway may contribute to the remodeling of the vessels because these enzymes are overexpressed by anatomical changes in the VSMC and this contributes to inflammation (

Figure 2). Our results showed a tendency to increase and an elevation, respectively, in the CP group. This suggests that the CP is very important because the physiological and anatomical changes in the vessels begin to appear in these animals due to the early insult of carbohydrates and remain marked and susceptible for consequences to appear later with age with a possible more aggressive response.

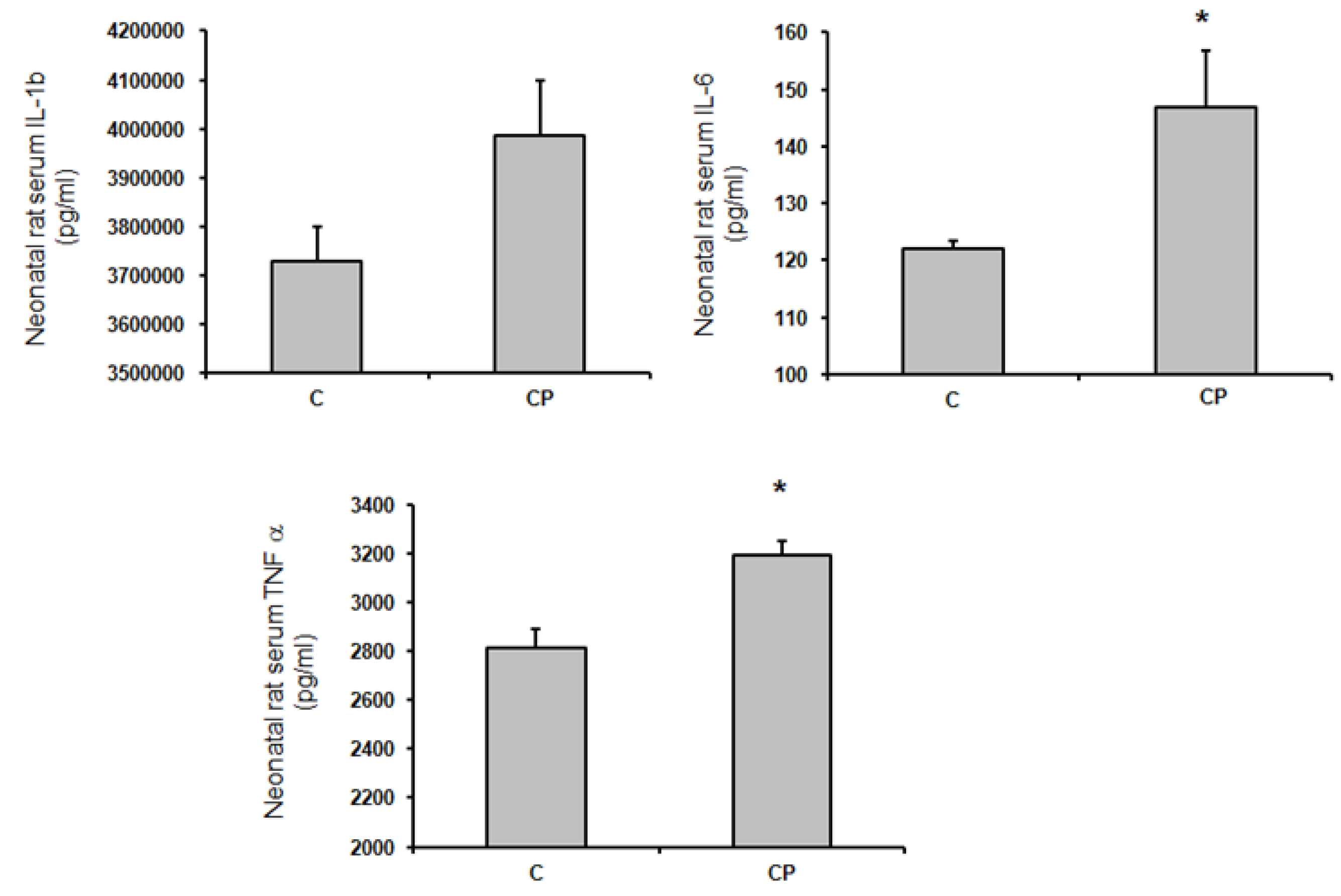

In this paper we explored if inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL6 were modified in the aortas from CP rats (

Figure 4). In this sense, TNF-α is involved in the shift from a contractile to a secretory phenotype of VSMCs. This switch promotes proliferation and production of extracellular matrix proteins which are associated with hyper-trophy of the medial [

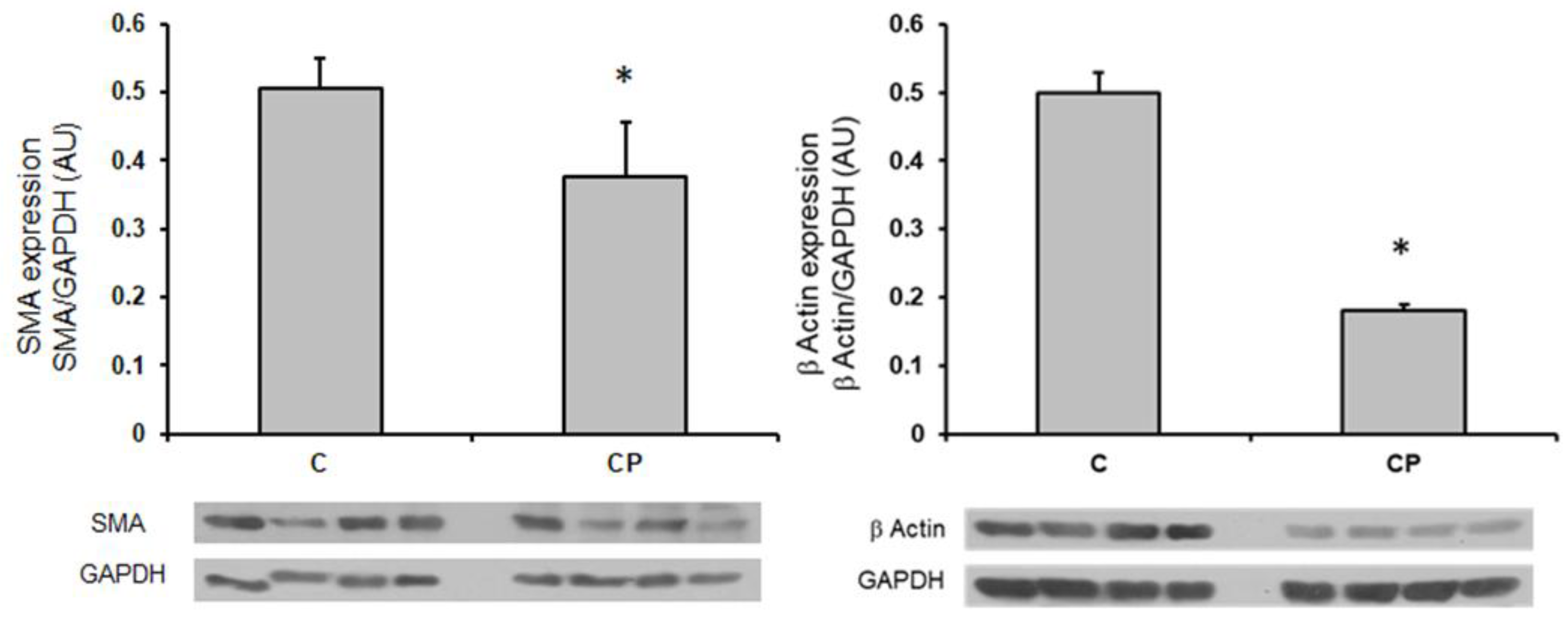

16] and seems to be present in our group of CP rats, since α-actin (SMA), a marker of this shift was decreased (

Figure 5). The expression of TNF-α in the aortic tissue can be in CP rats drive to SMA expression. TNF-α, induces growth and/or migration of VSMCs and stimulate the production of chemokines, leading to a ‘proinflammatory’ phenotype of VSMC. As previously mentioned, TNF-α was significantly increased in the CP group and there was a clear tendency of IL-1β to also be increased. Both these inflammatory mediators, then promote the secretion and expression of other cytokines and cell adhesion molecules, including IL-6 [

18] which was increased in the aortas from rats that received sucrose during the CP. Furthermore, it has been documented that the increase in shear stress accelerates the proliferation and turnover of endothelial cells, promotes the inflammatory response and adjusts vascular SMC phenotype towards the secretory phenotype [

47]. In this paper we found that smooth muscle β-actin was decreased in aortas from the group of CP rats. A decrease in smooth muscle β-actin is a marker of the media layer remodeling to a secretory phenotype which could underlie a decrease in contractility leading to hypertension. Although α-actin is the contractile protein and the one that if decreased acts as a marker of the secretory phenotype, β-actin is also present in VSMC forming part of the “cytoplasmic”, i.e. cytoskeletal “non-muscle” actin [

48]. We also determined the expression of β-actin and found that is also decreased in CP rats.

There are reports that demonstrate that elevated SBP and structural modifications of the vessels are associated with the presence of OS, low bioavailability of NO, and levels of MMPs [

49]. This sense, a study previously published by our group [

9] demonstrated that in the aortas of CP animals present OS and low expression of eNOS. Although in this paper (

Figure 2) there was only a tendency of eNOS to be diminished in the immunohistochemistry we had previously found that this enzyme was also diminished in the aortas from CP rats in western blot analysis [

28] and can be associated with the morphological changes that we observed.

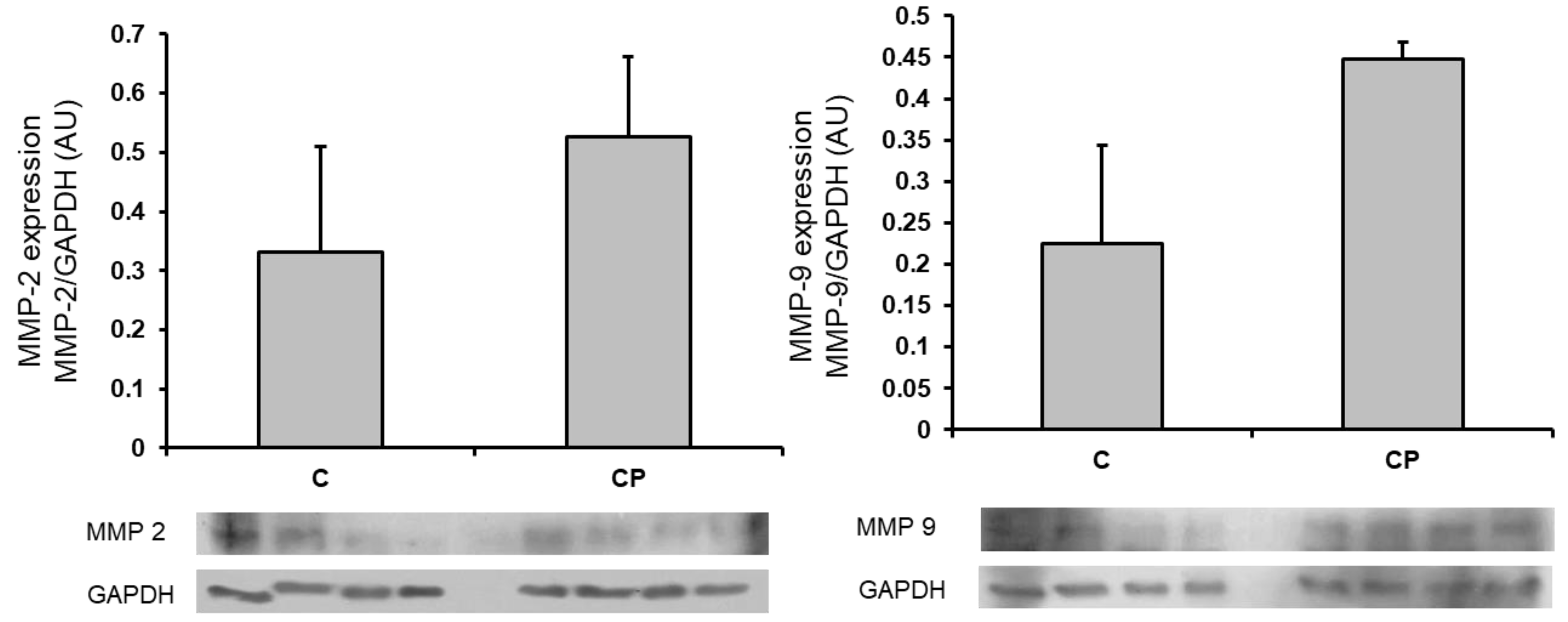

Inflammatory mediators can modify the MMPs expression that results in changes in the phenotype of VSMCs [

15]. The shift in the phenotype of VSMC from contractile to secretory is characterized by modifications in the MMPs expression or activity which are endopeptidases that degrade proteins in the extracellular matrix such as collagen and elastin. MMPs also modify endothelial cells, determine migration and proliferation of VSMC, alter Ca

2+ signaling, and contraction. Changes in MMP-2 and MMP-9 underlie arterial remodeling determining pathological disorders that include hypertension [

27,

50,

51]. In this paper we determined the expression of metalloproteinases (MMP-2 and -9) and found that there was a clear tendency to an increase in their expression in the aortas from CP rats (

Figure 6). We do not have a specific reason to explain it, although it could be due to the activity of the enzymes rather than the expression, which suggests that the alterations we found in the aortas cannot be attributed solely to the presence of these enzymes but that it would be interesting to evaluate their activity. MMP-2 and -9 are gelatinases and that are produced by several vascular cell types, including endothelial cells, pericytes and podocytes, fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. They participate in type IV collagen degradation, vasculature remodeling, angiogenesis, inflammation and atherosclerotic plaque rupture. MMP-2 is expressed constitutively on the cell surface, and it is involved in hypertension induced by maladaptive vascular remodeling by de-grading extra- and intracellular proteins. In turn, secretion of MMP-9 is induced by external stimuli, and it is stored in secretory granules [

52].

It is difficult to apply the results from basic studies in experimental animals on the possible role and on the mechanisms of changes induced in early stages to the programming of complex diseases including hypertension in humans. However, the increased knowledge on these issues could help prevent the appearance of diseases if it is proven that the same mechanisms participate in the human populations and could help prevent the appearance of the disease in adulthood.