1. Introduction

Traffic accidents represent a significant global public health issue. Annually, approximately 1.35 million people die on road incidents worldwide, with between 20 and 50 million sustaining non-fatal injuries. Over 90% of these fatalities occur in underdeveloped and developing countries [

1]. Brazil ranks among the top ten countries with the highest number of traffic-related deaths, with 31,945 fatalities in 2019 [

2]. In the state of Paraná

, data from DETRAN (State Department of Transit) indicate a 188% increase in traffic, rising from 383 in 2016 to 1,106 in 2019 [

3].

In Brazil, transport accidents are the second leading cause of hospitalizations due to external causes, directly impacting the organization of the health system due to the high costs associated with trauma care [

4]. Although traffic accidents can affect any road user, pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists are particularly vulnerable due to their greater exposure to bodily harm [

1].

Currently, bicycles are recognized as a viable solution to traffic congestion problems associated with the increasing number of motor vehicles in large and medium-sized cities worldwide [

5]. Bicycles are practical, cost-effective and environmentally friendly, with particularly high popularity among young children and teenagers. Additionally, bicycles offer enhanced mobility and cost-savings due to their lack of fuel consumption, making them both an eco-friendly means of transport [

6,

7] and a high-tech sports equipment.

Bicycles can access nearly all areas of a city and require minimal physical space. Their clear limitations include the range of travel, typically up to 7.5 km, a distance considered physically comfortable [

8], and the fact that bicycles are the most commonly involved non-motorized vehicle in accidents [

9].

Despite these limitations, governments and societies have been promoting cycling as a viable alternative for urban transportation. Active transportation, which includes human-powered modes such as walking, cycling, rollerblading, and skateboarding, is increasingly gaining popularity [

7].

Despite the numerous advantages of active transportation, significant concerns remain regarding safety, as cycling infrastructure is not uniformly accessible in all locations. Frequently, cyclists share the same space with motor vehicles, which poses a risk of accidents. Given that traffic violence is one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide, particularly in developing countries where the risks for bicycle users are heightened [

10,

11], the situation becomes even more alarming.

In Paraná, between 2008 and 2017, there were 30,062 traffic accidents involving cyclists, with 77.7% occurring on urban roads. During the same period, 899 traffic fatalities involving cyclists were recorded, with 40.1% occurring on urban roads [

12]. These data underscore the importance of conducting research on this topic in urban areas.

White existing literature addresses the safety of these users, there is a notable gap in research concerning the factors associated with cyclists accidents [

13,

14,

15]. A review of the literature revealed only one study analyzing the cycling network and the number of accidents involving cyclists over a ten-year period (2006-2016) in the city of Londrina-PR [

16].

Therefore, the objective of this study is to analyze the trend of accidents involving cyclists in Maringá and its surrounding region from 2010 to 2019, as well as the factors associated with these accidents. Additionally, we aim to characterize the studied population in term of the sex and age of the individuals involved in accidents; examine the types of vehicles involved, the city regions, the days, and times of occurrence; identify the times of day and days of the week with the highest incidence of accidents; and, ultimately, associate the variables of sex, age, location, day, and time with the severity of the accidents.

2. Methods

For the development of the research, we employed an ecological time-series study method to analyze accidents involving cyclists that occurred in the metropolitan region of Maringá from 2010 to 2019. The Metropolitan Region of Maringá (MRM) comprises 26 municipalities, established by State Complementary Law No. 83/1998. It encompasses an area of 5,978,592 km2, with a population of 809,915, a density of 135.47 inhabitants per km2 and a Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.817.

Data on the characteristics of bicycle-related events were collected from the databases of the Mobile Emergency Care Service (SAMU - Serviço de Atendimento Móvel de Urgência) of Northwest Paraná, and the Integrated Emergency Trauma Care Service (SIATE - Serviço Integrado de Atendimento ao Trauma em Emergência) located in the municipality of Maringá-PR, which is also responsible for pre-hospital care in the MRM.

The sample included all Pre-hospital Care Records of cyclist accidents attended by SAMU and SIATE in Maringá-PR from January 2010 to December 2019.

Data collection was performed through the individual and manual review of all medical records generated by SIATE and SAMU. The information was transcribed into a spreadsheet created by the researchers, which included the following variables: date of care, age and sex of the victims, location of the incident and vehicles involved.

For a clearer understanding of the results, age groups were categorized in 10-year intervals.

The collected data were compiled using Microsoft Excel

®. Following compilation, a descriptive analysis of the cyclist accident profiles in the MRM was carried out. Trend analysis was performed using the non-parametric Mann-Kendall test [

17] and the chi-square test to evaluate associations between variables. A significance level of 5% (p-value < 0.001) was adopted.

All analyses were conducted using the R statistical environment (R Development Core Team), version 3.5 [

18]. For event data analysis, Microsoft Excel (2003) and QGIS 3.16.11 software were used.

The research project was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee Involving Human Beings of the State University of Maringá, with approval number 3.071.844. Since the data were secondary, a waiver for the Free and Informed Consent Form (FICF) was requested.

3. Results

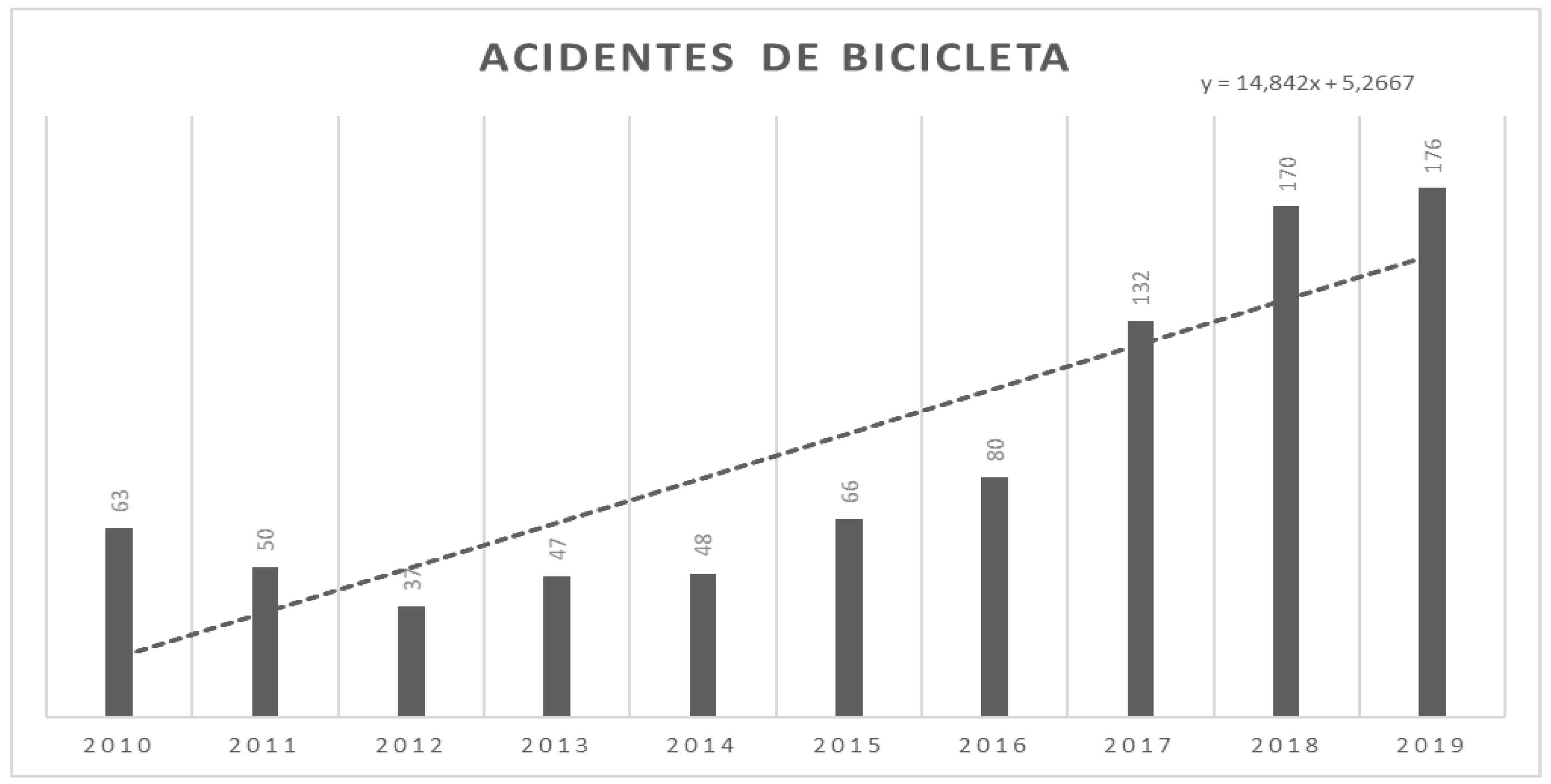

Between January 2010 and December 2019, SAMU and SIATE in Maringá-PR recorded 848 cyclist accident responses . The number of accidents during the study period showed a slight decrease from 2010 to 2012 (from 7.2% to 4.2%) in the Metropolitan Region of Maringá (MRM). Starting in 2013, there was a continuous increase, reaching 20.2% (n=176) of the accidents in 2019. Despite these variations, a strong upward trend in the number of cyclist accidents was observed during the analyzed period

(R

2 = 0.0017) (

Figure 1).

A year-by-year review of the indicators was conducted to investigate whether there were patterns in the characteristics of cyclist accidents during the analyzed period. The majority of bicycle-related accidents involved male individuals (84.4%) (

Table 1).

The majority of the victims were male, and a higher percentage of them experienced severe accidents compared to females (7.8% versus 5.3%, respectively). Females, proportionally, experienced less severe accidents (92.4%). For minor accidents, there were five male cases for every female case, whereas for moderate accidents, this ratio doubled to ten males for every female. In severe cases, the ratio was eight males to each female.

The highest percentage of cyclist accidents during the analyzed period occurred in the 11 to 20-year age group. Conversely, the lowest percentages were observed in children up to 10 years of age and, notably, in individuals over 60 years old. Throughout the period, children under 10 years consistently had accident rates below 10%.

During the week, there was a tendency for increased accidents on the last two days, Friday and Saturday. However, the study indicates that the highest concentration of severe cases occurred on Tuesdays (22.2%) and Fridays (23.5%) (

Table 2).

The highest percentage of accidents across all analyzed years occurred between noon and 8:00 p.m., with particularly notable peaks in 2015 and 2018, during which this percentage exceeded 60%. Although most cyclist accidents were minor, the number of severe accidents was higher than that of moderate accidents, with statistical significance (

Table 3).

Regarding the type of accident, falls were the most frequent incident in most years, followed by accidents involving cyclists and cars and cyclists and motorcycles.

4. Discussion

This study analyzed the trend of traffic accidents involving cyclists in the metropolitan region of Maringá-PR and the associated factors from 2010 to 2019. Starting in 2017, there was a significant increase in accidents involving cyclists, which is directly related to the rise in the number of cyclists on the streets [

19,

20]. This increase is attributed to heightened concerns about the ecological impacts of transportation [

21] and the expansion of the cycling infrastructure in Maringá [

22]. In 2008, the city had a cycling network of eight kilometers, in poor conditions and without any type of interconnection. The development of new bike lanes gained momentum in 2015, and the network now spans approximately 37 kilometers [

23]. For instance, in the city of São Paulo, the growth of the cycling network has also been accompanied by an increase in cyclist fatalites [

24]. On the other hand, in the Federal District, investment in bike lanes has led to a reduction in cyclist mortality [

25].

Data from the Brazilian Traffic Medicine Association [

26] reveals that, between 2010 and 2019, hospital admissions for cyclists involved in accidents increased by 57% in Brazil, with a notable rise of 1,250% in Rio Grande do Norte and 678% in Pernambuco, consistent with our findings [

26]. Infosiga SP (2022) data, also reported in the Folha de São Paulo newspaper on March 3, 2022, indicated a significant rise in cyclist deaths in the capital of São Paulo, between 2015 and 2021, despite the expansion of the cycling network. These findings suggest that while the implementation of bike lanes encourages greater bicycle use, it does not always ensure increased safety for users, as these lanes are often added to streets and avenues without adequate integration and traffic synchronization. Approximately 80% of cycling accidents involved males. Consistent with these studies, research conducted by De Guerra

et al [

15] was also identified.

The highest percentage of accidents recorded and analyzed in the study involved children and adolescents aged 11 to 20 years – data also reported by Tavares

et al [

27] and Orsi [

9]. Conversely, children under 10 years and individuals over 60 years, as previously mentioned, experienced the fewest cyclist accidents - information corroborated by

Sousa et al [

28].

A trend of increasing accidents throughout the week, peaking on weekends, was observed, as detailed in

Table 2 and supported by the researchers of Tavares

et al [

29]. This higher accident rate on weekends may be attributed to increased bicycle use for recreational purposes [

20]. Despite this weekend increase, the highest concentration of severe cases occurs on Tuesdays and Fridays. It is inferred that this results from the greater number of cars circulating on weekdays compared to weekends. Consequently, the conflict between cyclists and vehicles leads to higher accident rates on weekdays [

30].

Regarding the times of highest accident incidence, the collected data reveal that the majority of accidents occur between noon and 8:00 p.m. across all analyzed years. During this period, there is a higher number of cyclists on the roads, and end-of-day fatigue among cyclists and other road users contributes to this statistic. Additionally, nighttime conditions worsen visibility, and the lack of mutual awareness between cyclists and other road users increases the severity of accidents [

31]. This explains why 33.3% of afternoon accidents are classified as severe, with an increase to 38.1% during nighttime.

The present study is limited by the use of secondary data derived from Pre-hospital Care Records, which may present inaccuracies or incomplete entries. Despite this limitation, SAMU and SIATE are valuable sources of data, as their work facilitates access to emergency hospital services and hospital beds, thereby serving as a critical entry point into the healthcare system that can save lives [

15].

Another important aspect of this research is the use of a less common data source compared to published literature. For example, studies such as those by ABRAMET with data from DATASUS [

26]; Sousa

et al, with data from VIVA Inquérito [

28]; Maffei de Andrade and Mello Jorge, with data from military police and DATASUS [

32]; Nóbrega

et al, using DETRAN and DATASUS [

25], and Galvão

et al, with data from SIM and SUS [

33]. The findings of this study are distinct due to its unique data source, yet contribute to the analysis of cyclist accidents by highlighting cases that may not be recorded in traditional notification systems. Consequently, many minor accidents involving cyclists might not be reflected in the statistics and thus may not be considered in accident prevention planning [

33]. Additionally, the costs associated with these minor care incidents still require healthcare services, even though they may not be reflected in the statistics. Therefore, despite its specific characteristics, this research demonstrates that SIATE and SAMU provide a substantial number of services to cyclists, and this data should be incorporated in the planning of cycling infrastructure for the metropolitan region of Maringá and other cities in Brazil.

Thus, there is a clear need for expanded research on this topic, not only in Maringá and its region but also across cities of Paraná and other Brazilian states. Cyclist accidents have increasingly demanded healthcare services, necessitating targeted planning based on studies that investigate the unique characteristics and needs of each city or region.

Acknowledgments

To the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) – Funding Code 001 – which supported the conduct of this research.

References

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Road Safety. World Heal Organ [Internet]. 2018;20. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565684.

- Portal do Transito e Mobilidade [Internet]. 2021 [accessed Jan 29, 2022]. Available at: https://www.portaldotransito.com.br/.

- Departamento de Trânsito do Paraná [Internet]. 2021 [accessed Jan 29, 2022]. Available at: https://www.detran.pr.gov.br.

- Brasil. Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (Ipea). Estimativa dos custos dos acidentes de trânsito no Brasil com base na atualização simplificada das pesquisas anteriores do Ipea. Relatório Pesqui do Inst Pesqui Econômica Apl [Internet]. 2015 [accessed Sep 10, 2022]. Available at: http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/bitstream/11058/7456/1/RP_Estimativa_2015.pdf.

- Gössling S, Choi A, Dekker K, Metzler D. The social cost of automobility, cycling and walking in the European Union. Ecol Econ 2019, 158, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. Why cities need to take road space from cars - and how this could be done. J Urban Des 2020, 25, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand C, Dons E, Anaya-Boig E, Avila-Palencia I, Clark A, Nazelle A, Gascon M, Gaupp-Berghausen M, Gerike R, Götschi T, Iacorossi F, Kahlmeier S, Laeremans M, Nieuwenhuijsen M, Orjuela JP, Racioppi F, Raser E, Rojas-Rueda D, Panis LI. The climate change mitigation effects of daily active travel in cities. Transp Res Part D Transp Environ 2021, 93, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandretti L, Aslak U, Lehmann S. The scales of human mobility. Nature 2020, 587, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orsi C, Montomoli C, Otte D, Morandi A. Road accidents involving bicycles: Configurations and injuries. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot 2017, 24, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szell, M. Crowdsourced quantification and visualization of urban mobility space inequality. Urban Plan 2018, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladeira RM, Malta DC, Neto OLM, Montenegro MMS, Filho AMS, Vasconcelos CH, Mooney M, Naghavi M. Acidentes de transporte terrestre: Estudo Carga Global de Doenças, Brasil e unidades federadas, 1990 e 2015. Rev brasileira de epidemiologia 2017, 20 (Suppl. 1), 157–170.

- Departamento de Trânsito do Paraná. Statistical Yearbook [Internet]. 2017 [accessed Jan 30, 2022]. Available at: https://www.detran.pr.gov.br.

- Pedroso FE, Angriman F, Bellows AL, Taylor K. Bicycle use and cyclist safety following Boston’s bicycle infrastructure expansion, 2009-2012. Am J Public Health 2016, 106, 2171–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spörri E, Halvachizadeh S, Gamble JG, Berk T, Allemann F, Pape HC,Rauer T. Comparison of injury patterns between electric bicycle, bicycle and motorcycle accidents. J. Clin. Med 2021, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Guerre LEVM, Sadiqi S, Leenen LPH, Oner CF, Gaalen SM. Injuries related to bicycle accidents: An epidemiological study in The Netherlands. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2020, 46, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva MOM, Cunha FCA. Rede cicloviária e acidentes envolvendo ciclistas na cidade de Londrina/PR. Rev Caminhos Geogr 2020, 21, 253–268. [Google Scholar]

- Agresti, A. An introduction to categorical data analysis. 3rd Edition. Hoboken: John Wiley And Sons; 2012.

- R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2015.

- Associação Brasileira do Setor de Bicicletas. Aliança Bike. Mercado de bicicletas elétricas 2021 [Internet]. 2021 [accessed Sep 10, 2022]. Available at: https://aliancabike.org.br/wp-content/uploads/docs/2021/04/Boletim-Bike-Eletrica.pdf.

- Associação Brasielira dos Fabricantes de Motocicletas, Ciclomotores, Motonetas, Bicicletas e Similares (ABRACICLO) [Internet]. 2021 [accessed Jun 3, 2021]. Available at: https://www.abraciclo.com.br.

- Rosenberg Associados. O uso de bicicletas no Brasil: Qual o melhor modelo de incentivos? [Internet]. 2015. [accessed Sep 10, 2022]. Available at: http://www.abraciclo.com.br/linkssitenovo/downloads/ABRACICLO%20ESTUDO%20MODELO%20DE%20INCENTIVO.pdf142.

- Secretaria de Mobilidade Urbana (SEMOB). Associados CVE e A. Plano de Mobilidade de Maringá [Internet]. 2019. [accessed Sep 10, 2022]. Available at: http://ippul.londrina.pr.gov.br/index.php/plano-de-mobilidade.html.

- Barbiero, LC. A produção de ciclovias em Maringá-Pr. In: Textos para discussão LabCit/Gedri; 2020; Florianópolis, Brasil. Florianópolis. p. 1-9.

- INFOSIGA SP [Internet]. 2022 [accessed Mar 5, 2022]. Available at: http://www.infosiga.sp.gov.br/.

- Nóbrega BG, Santos JA, Andrade M, Júnior RVS, Costa SMT. Análise da Acidentalidade de Usuários de Bicicleta dos Últimos 10 Anos no Distrito Federal. Rev Cient de Pesquisa Aplicada à Eng 2020, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Associação Brasileirta de Medicina de Tráfego (ABRAMET) [Internet]. 2021 [accessed Oct 10, 2021]. Available at: https://abramet.com.br/.

- Tavares FL, Leite FMC, Caliman MF, Bomfat PR, Cavaca AG, Antunes MN. Ciclismo e saúde: As matérias sobre bicicleta veiculadas em um jornal de grande circulação no Espírito Santo. Rev Bras Pesqui em Saúde 2018; 20(2):88-97.

- Sousa CAM, Bahia CA, Constantino P. Analysis of factors associated with traffic accidents of cyclists attended in Brazilian state capitals. Cienc e Saude Coletiva 2016, 21, 3683–3690. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares FL, Leite FMC, Lima EFA, Melo EBM, Silva TASM, Coelho MJ. The bicycle accident in Brazil: An integrative review / Os acidentes de bicicleta no Brasil: Uma revisão integrativa. Rev Pesqui Cuid é Fundam Online 2019, 11, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva ALDN. Prevalência de fatores associados à ocorrência e severidade de acidentes com bicicleta em porto alegre – RS [dissertation]. Porto Alegre (RS): Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul; 2018.

- Pour-Rouholamin M, Zhou H. Investigating the risk factors associated with pedestrian injury severity in Illinois. J Safety Res 2016, 57, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade SM, Mello Jorge MHP. Características das vítimas por acidentes de transporte terrestre em município da Região Sul do Brasil. Rev Saude Publica 2000, 34, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvão PVM, Oliveira TG, Marques OF, Pestana VM, Vidal HG, Souza EHA. Acidentes Fatais De Bicicletas No Brasil – 2001 a 2010. Rev Baiana Saúde Pública 2018, 41, 965–980. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).