1. Introduction

The field of technoscience, which encompasses the interconnected realms of science, technology, and society, has historically been shaped by a predominantly Western, male perspective [

2,

3]. This gender and cultural imbalance has profoundly influenced the selection and prioritization of problems deemed worthy of scientific and technological attention, often resulting in a narrow focus that overlooks issues disproportionately affecting women, minorities, and non-Western populations [

4,

5].

The consequences of this bias are far-reaching and deeply entrenched in various domains. For instance, in medical research, women’s health issues have often been neglected or understudied, leading to significant gaps in understanding and treating conditions that primarily affect female populations [

6]. Similarly, urban planning has frequently failed to consider the diverse needs of different demographic groups, resulting in cities designed primarily for able-bodied, working-age men (Kern, 2020). Furthermore, technological innovations, despite their potential for positive change, have sometimes exacerbated existing social inequalities by catering primarily to the needs and preferences of dominant societal groups [

7].

The field of technoscience, which encompasses the interconnected realms of science, technology, and society, has historically been shaped by a predominantly Western, male perspective [

8,

9]. This gender and cultural imbalance has profoundly influenced the selection and prioritization of problems deemed worthy of scientific and technological attention, often resulting in a narrow focus that overlooks issues disproportionately affecting women, minorities, and non-Western populations [

5,

10].

The consequences of this bias are far-reaching and deeply entrenched in various domains. For instance, in medical research, women’s health issues have often been neglected or understudied, leading to significant gaps in understanding and treating conditions that primarily affect female populations [

11]. Similarly, urban planning has frequently failed to consider the diverse needs of different demographic groups, resulting in cities designed primarily for able-bodied, working-age men [

12]. Furthermore, technological innovations, despite their potential for positive change, have sometimes exacerbated existing social inequalities by catering primarily to the needs and preferences of dominant societal groups [

7].

This paper aims to address these critical shortcomings by proposing a novel framework for establishing objective criteria to determine which human problems are truly worth solving. Our objective is to transcend traditional biases and incorporate a more inclusive, global perspective in the identification and prioritization of pressing issues that merit scientific and technological attention.

Building upon this foundation of research, our study seeks to extend the application of systems thinking and network analysis to a broader, more comprehensive set of global challenges. While previous works have applied these methodologies to specific domains such as healthcare [

13,

14], sustainability [

15], and education [

16], our paper aims to create a more holistic framework that spans multiple sectors and disciplines. Furthermore, we draw inspiration from the intersectional approach introduced by [

17] and the decolonizing perspective advocated by [

18] to address the systemic biases in problem selection within technoscience.

Our work advances the literature by synthesizing these various approaches into a unified framework for identifying, prioritizing, and understanding the interconnections between global challenges. Unlike previous studies that focus on specific issues or sectors, our research provides a comprehensive methodology for debiasing problem selection across the entire field of technoscience. By doing so, we offer a novel tool for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to approach global challenges in a more equitable, inclusive, and effective manner, potentially reshaping how we prioritize and address the most pressing issues facing humanity.

This paper builds upon our previous work, "The Wicked and the Complex: A New Paradigm for Societal Problem-Solving" [

19] (Hipólito and Khanduja, 2024), which introduced the application of complex systems theory to wicked problems. In that paper, we established the theoretical foundation for viewing societal challenges through the lens of complexity science. The current study extends this framework by providing a more detailed mathematical toolkit and concrete examples of its application. While our previous paper laid the groundwork for a paradigm shift in approaching wicked problems, this work offers practical methodologies for researchers and policymakers to implement these concepts. By bridging the gap between theoretical concepts and real-world applications, we aim to demonstrate how complex systems theory can be operationalized to address pressing societal issues more effectively. This paper not only reinforces the importance of embracing complexity in problem-solving but also provides a roadmap for turning these insights into actionable strategies for tackling some of society’s most intractable challenges.

The significance of this research lies in its potential to reshape the landscape of technoscience by offering a more equitable and comprehensive approach to problem selection. By developing a set of metrics that consider factors such as a problem’s scale, urgency, potential impact, and relevance across diverse populations, we seek to create a framework that can guide more balanced and effective resource allocation in scientific and technological endeavors.

Moreover, this paper contributes to the ongoing efforts to decolonize and degender technoscience [

1,

20,

21]. By mapping the interconnections between various global challenges and highlighting the complex web of influences between issues, we aim to provide a more holistic understanding of the problems facing humanity. This approach not only helps in identifying overlooked issues but also informs more integrated and effective problem-solving strategies.

In the following sections, we will examine the historical context of problem selection in technoscience, detail our proposed framework for objective problem identification, present a comprehensive list of human problems that meet our criteria, and analyze their interconnections. Through this work, we aspire to catalyze a shift towards more inclusive, equitable, and impactful scientific and technological pursuits that address the most pressing needs of our diverse global population.

2. Historical Context and Problem

The historical dominance of Western male perspectives in technoscience has led to significant gender and cultural biases in problem selection, resulting in a narrow focus that overlooks critical issues affecting diverse populations. These biases permeate various scientific and technological domains, with far-reaching consequences [

9,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

In medicine, the "male as norm" paradigm has led to a significant underrepresentation of women in clinical trials and a lack of understanding of sex-specific health issues [

27]. Heart disease research, for instance, has predominantly focused on male patients, leading to misdiagnoses and suboptimal treatments for women, whose symptoms often differ from men’s [

28]. Similarly, conditions such as endometriosis, affecting millions of women worldwide, have been historically underfunded and understudied [

29,

30].

Cultural biases have also shaped research priorities, with Western perspectives often neglecting health issues prevalent in non-Western countries. Neglected tropical diseases, affecting over a billion people globally, receive disproportionately little attention and funding compared to diseases more common in developed countries [

31,

32]. This bias extends to technological development, where solutions often prioritize Western contexts, neglecting the unique needs and constraints of developing regions [

33,

34].

The field of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) exemplifies how these biases can perpetuate and exacerbate existing social inequalities. Facial recognition systems, for instance, often exhibit significantly higher error rates for women and people of color. Buolamwini and Gebru [

35] found that while the error rate for light-skinned males was only 0.8 percent, it rose to 34.7% for dark-skinned females. This disparity stems from training datasets that overrepresent white, male faces [

36,

37].

The implications of these biased AI systems are far-reaching and potentially discriminatory across various applications, from law enforcement to healthcare. Natural Language Processing models often inherit and amplify societal biases related to gender and race [

38]. In healthcare, AI systems for diagnosis and treatment recommendations have exhibited racial biases that could lead to disparities in care [

39]. Similarly, AI-powered resume screening tools have been found to perpetuate gender biases in hiring processes [

40].

These biases in AI and ML systems reflect and amplify existing societal prejudices, stemming from a lack of diversity in development teams, insufficient consideration of diverse perspectives, and inadequate representation in training datasets [

41,

42]. Addressing these issues requires a multifaceted approach, including increasing diversity in AI research and development, implementing rigorous bias testing, creating more representative datasets, and developing new technical approaches to mitigate bias [

43,

44,

45].

The consequences of this narrow focus extend beyond specific fields. In urban planning and design, the prioritization of male-centric issues has led to cities that are often unsafe and inconvenient for women, children, and elderly individuals [

12]. In technology development, it has resulted in products and services that fail to meet the needs of diverse user groups, potentially widening the digital divide [

7,

46]. Moreover, by overlooking issues that disproportionately affect non-Western populations, the scientific community has missed opportunities to address some of the world’s most pressing challenges in global development and sustainability [

47].

This bias in problem selection has also hindered innovation and scientific progress. By limiting the diversity of perspectives and problems being addressed, the scientific community has potentially missed out on novel solutions and breakthrough discoveries that could arise from a more inclusive approach [

48,

49,

50,

51].

Recognizing these historical biases and their consequences is crucial for developing a more equitable and effective approach to problem selection in technoscience. The following sections of this paper will propose a framework aimed at addressing these shortcomings and fostering a more inclusive and globally relevant scientific agenda.

3. Methodology

Our approach to developing a more equitable framework for problem selection in technoscience involves a theoretical exercise based on reasoning and logic. This methodology aims to provide a conceptual foundation for a more objective, inclusive, and globally relevant approach to identifying and prioritizing human problems worthy of scientific and technological attention.

The methodology of network analysis, as we shall see, helps overcome the historical Western-male standpoint by providing a more objective, data-driven framework for identifying and prioritizing global issues. By mapping the interconnections between various problems and evaluating them based on a set of criteria, the methodology minimizes the biases that can arise from subjective or culturally specific viewpoints. This network-based approach allows for the inclusion of diverse perspectives by quantifying the significance and impact of problems from different cultural, social, and gendered contexts. Consequently, it avoids the dominance of a singular Western-male perspective, enabling a more inclusive identification of issues that better represent the concerns and needs of a wider range of global communities.

We propose a set of criteria aimed at minimizing bias and ensuring a more inclusive approach to problem selection. These criteria are derived from logical considerations of global challenges and ethical principles: a) Global Impact Potential: The theoretical scope of the problem’s effect on humanity as a whole. b) Urgency of the Problem: The logical time-sensitivity of the issue and potential consequences of inaction. c) Equity Considerations: The theoretical impact on underrepresented or marginalized groups. d) Sustainability Implications: The logical long-term environmental, social, and economic implications. e) Potential for Cross-Disciplinary Solutions: The theoretical benefit of interdisciplinary approaches.

This set of criteria is better because it systematically incorporates diverse ethical and practical considerations that move beyond traditional frameworks, which have often been limited by culturally specific or gendered biases. By emphasizing global impact, urgency, and equity, the methodology prioritizes problems that affect humanity broadly, including those that disproportionately impact underrepresented or marginalized groups. The focus on sustainability and interdisciplinary solutions further ensures that the selected problems are considered in a holistic and forward-looking manner, integrating insights from various cultural, social, and scientific perspectives. This structured yet inclusive approach reduces the risk of bias inherent in decision-making processes dominated by a narrow, homogeneous viewpoint, fostering a more equitable and globally relevant prioritization of issues.

For each criterion, we propose conceptual metrics to enable systematic evaluation: a) Scale: A theoretical measure of the problem’s reach, considering both population and geographic spread. b) Urgency: A logical assessment of the problem’s progression and potential for escalation. c) Potential Impact: A reasoned estimate of positive change if the problem is addressed. d) Global Relevance: A theoretical assessment of the problem’s significance across different cultures and regions. e) Intersectionality: A logical consideration of how the problem affects multiple marginalized groups.

This scale incorporates multiple dimensions that ensure a comprehensive assessment of global challenges. The Scale criterion accounts for the problem’s reach, both in terms of population and geographic spread, ensuring that issues are not overlooked simply because they are prevalent outside Western contexts. Urgency assesses the problem’s progression and potential for escalation, prioritizing issues that require immediate attention regardless of their geographic origin. Potential Impact considers the possible positive outcomes of addressing the problem, allowing for a more balanced evaluation of which issues could produce the most significant benefits. Global Relevance ensures that problems are evaluated based on their significance across different cultures and regions, moving beyond a narrow, culturally specific perspective. Finally, Intersectionality addresses the problem’s impact on multiple marginalized groups, fostering an inclusive approach that recognizes the complexity of global challenges and prioritizes problems that affect diverse populations. Together, these conceptual metrics provide a structured yet adaptable framework that minimizes bias and promotes a more equitable selection process for identifying problems worth solving.

4. Theoretical Process for Problem Identification and Selection

To address the historical biases inherent in problem selection and to foster a more equitable approach to global challenges, we propose a comprehensive, multi-stage methodology. This framework is designed to ensure that problem identification and prioritization are not only systematic but also inclusive, moving beyond traditional, culturally specific perspectives.

Initial Problem Identification: A broad consideration of potential global challenges based on logical deduction and current understanding of world issues.

Criteria Application: A theoretical application of our developed criteria to these problems, using reasoning to assess how each problem aligns with the criteria.

Comparative Analysis: A logical comparison of problems against each other using our conceptual metrics, to create a prioritized list.

Holistic Assessment: An overall evaluation considering the interplay between different criteria and potential synergies or conflicts in addressing multiple problems.

Theoretical Refinement: A logical consideration of how this process might be iteratively improved and adapted over time to maintain relevance and inclusivity.

This methodology provides a theoretical framework for a more equitable approach to problem selection in technoscience. By applying logical reasoning to these proposed criteria and processes, we aim to demonstrate how historical biases in problem selection could be addressed, and how a more inclusive approach to global challenges might be structured. Based on our criteria, we identify the following objective problems worth solving:

4.1. Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation

Global Impact: Affects all regions and populations

Urgency: Rapidly escalating with potential irreversible consequences

Equity: Disproportionately impacts vulnerable populations

Sustainability: Central to long-term environmental and economic stability

Cross-disciplinary: Requires collaboration across sciences, economics, and policy

4.2. Pandemic Preparedness and Global Health Security

Global Impact: Potential to affect entire global population

Urgency: Rapid spread of diseases in interconnected world

Equity: Often hits disadvantaged communities hardest

Sustainability: Crucial for stable societies and economies

Cross-disciplinary: Involves virology, epidemiology, data science, and social sciences

4.3. Sustainable Food and Water Security

Global Impact: Essential for all human life

Urgency: Increasing pressures from population growth and climate change

Equity: Scarcity affects marginalized communities most severely

Sustainability: Fundamental to human and environmental health

Cross-disciplinary: Spans agriculture, hydrology, nutrition, and technology

4.4. Quality Education Access

Global Impact: Potential to uplift entire societies

Urgency: Critical for addressing rapid technological and social changes

Equity: Key to reducing socioeconomic disparities

Sustainability: Long-term effects on economic and social development

Cross-disciplinary: Involves pedagogy, psychology, technology, and social sciences

4.5. Sustainable Energy Transition

Global Impact: Affects global economy and environment

Urgency: Critical for climate change mitigation

Equity: Access to clean energy can reduce poverty

Sustainability: Central to long-term environmental and economic stability

Cross-disciplinary: Involves physics, engineering, economics, and policy

4.6. Artificial Intelligence Governance and Ethics

Global Impact: Increasingly pervasive in all aspects of society

Urgency: Rapid AI development outpacing regulatory frameworks

Equity: Potential to exacerbate or reduce inequalities

Sustainability: Long-term implications for work, privacy, and human rights

Cross-disciplinary: Spans computer science, ethics, law, and social sciences

4.7. Biodiversity Conservation and Ecosystem Restoration

Global Impact: Affects planetary health and human well-being

Urgency: Rapid loss of species and habitats

Equity: Disproportionately affects indigenous and rural communities

Sustainability: Critical for long-term environmental balance

Cross-disciplinary: Involves biology, ecology, climate science, and social sciences

4.8. Mental Health and Well-Being

Global Impact: Affects individuals across all societies

Urgency: Rising global rates of mental health issues

Equity: Often stigmatized and underaddressed in many communities

Sustainability: Long-term impact on societal health and productivity

Cross-disciplinary: Involves psychology, neuroscience, social work, and public health

These problems meet our criteria for objectivity, global relevance, urgency, equity considerations, sustainability implications, and potential for cross-disciplinary solutions. They represent critical challenges that, if addressed, could significantly improve human well-being and planetary health.

5. Mathematical Framework for Network Analysis

To analyze the mutual influences between these problems in a network analysis framework, we consider how addressing or exacerbating one problem might affect the others. We use a scale of 0-3 to represent the strength of influence:

Here’s a matrix representing these relationships:

Table 1.

Influence matrix of global challenges

Table 1.

Influence matrix of global challenges

| |

CC |

PP |

FWS |

EA |

SE |

AI |

BC |

MH |

| Climate Change (CC) |

- |

2 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

| Pandemic Preparedness (PP) |

1 |

- |

2 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

| Food/Water Security (FWS) |

3 |

1 |

- |

2 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

| Education Access (EA) |

2 |

2 |

2 |

- |

2 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

| Sustainable Energy (SE) |

3 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

- |

2 |

3 |

1 |

| AI Governance (AI) |

1 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

- |

1 |

2 |

| Biodiversity Conservation (BC) |

3 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

- |

2 |

| Mental Health (MH) |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

- |

5.1. Key Relationships

Climate Change has strong influences on Food/Water Security (3), Sustainable Energy (3), and Biodiversity Conservation (3).

Pandemic Preparedness strongly influences Mental Health (3) due to the psychological impacts of health crises.

Food/Water Security strongly affects Climate Change (3) and Biodiversity Conservation (3) due to agricultural practices and land use.

Education Access has a strong influence on AI Governance (3) and Mental Health (3), as education shapes technological understanding and overall well-being.

Sustainable Energy strongly influences Climate Change (3) and Biodiversity Conservation (3).

AI Governance has a strong influence on Education Access (3) due to its potential to transform learning systems.

Biodiversity Conservation strongly affects Climate Change (3) and Food/Water Security (3) due to ecosystem services.

Mental Health is strongly influenced by Pandemic Preparedness (3) and Education Access (3), but has moderate or weak influences on other problems.

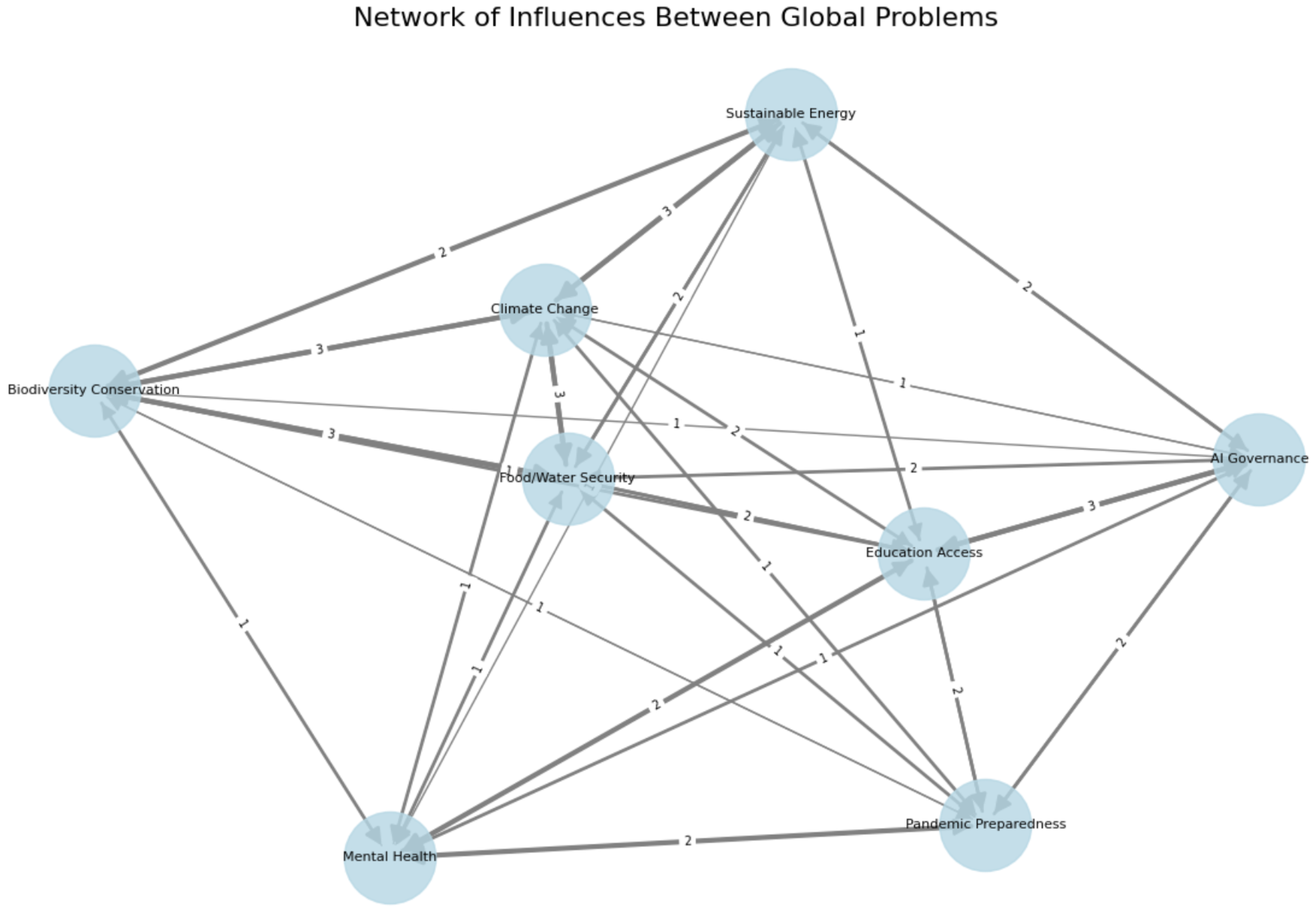

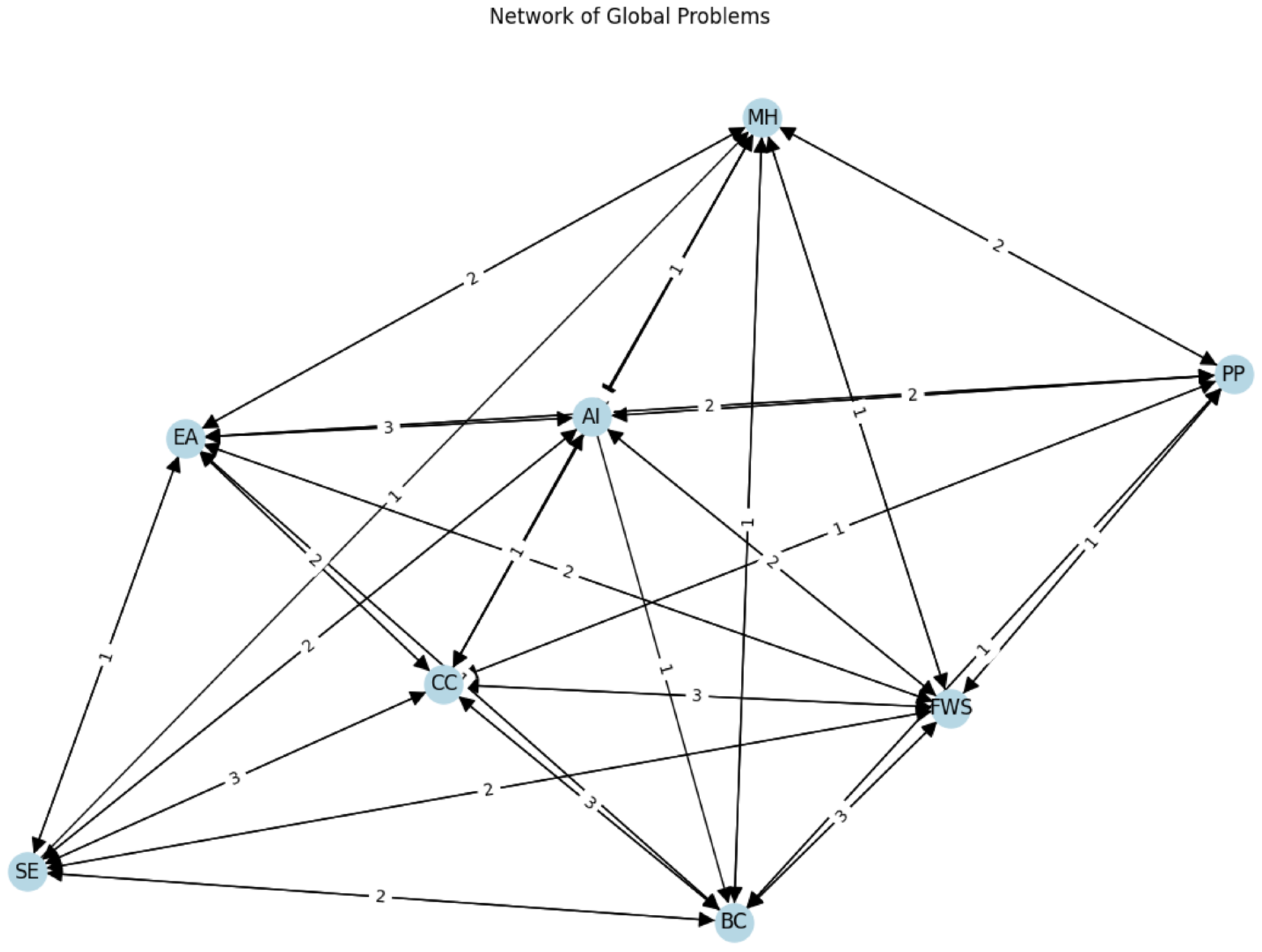

This network analysis reveals complex interdependencies among these global challenges. Climate Change, Food/Water Security, and Education Access appear to have the most widespread and significant influences across the network. Addressing these central issues could potentially create positive cascading effects on other problems. Conversely, neglecting these central issues could exacerbate multiple other challenges.

The analysis also highlights the importance of holistic, systems-thinking approaches to global problem-solving. Given the strong interconnections, solutions that address multiple problems simultaneously (e.g., sustainable agriculture practices that enhance food security while mitigating climate change and preserving biodiversity) could be particularly impactful.

To generate our network diagram and quantify the relationships between global problems, we employed concepts from graph theory and network analysis. The mathematical foundation of our approach is as follows:

5.2. Adjacency Matrix

We begin with an adjacency matrix

A, where

represents the strength of influence of problem

i on problem

j. In our case, this is an

matrix corresponding to our 8 identified problems:

where , representing no, weak, moderate, and strong influence respectively.

5.3. Directed Weighted Graph

We construct a directed weighted graph , where:

V is the set of vertices (our global problems)

E is the set of edges (the influences between problems)

is a weight function assigning each edge a weight based on the strength of influence

5.4. Edge Weight Calculation

For each pair of vertices

, we create an edge

if

, with weight:

5.5. Node Centrality

To assess the overall importance of each problem in the network, we can calculate various centrality measures. One key measure is the weighted degree centrality:

This sum represents the total strength of influences for each problem, both influencing and being influenced by others.

5.6. Network Density

To quantify the overall connectedness of our problem network, we calculate the network density:

where is the number of non-zero edges and is the number of vertices.

5.7. Visualization

For the visual representation, we use a force-directed graph drawing algorithm. This algorithm treats the graph as a physical system where:

where d is the distance between nodes, and and are repulsion and attraction constants.

The final position of each node is determined by iteratively applying these forces until the system reaches equilibrium.

This mathematical framework allows us to not only visualize the complex relationships between global problems but also to quantify and analyze these relationships in a rigorous manner. The resulting network provides insights into the centrality of certain issues, the density of connections, and potential cascading effects of interventions in this interconnected system of global challenges.

6. Network Analysis and Intervention Simulation

To analyze the mutual influences between global challenges and simulate potential interventions, we employ concepts from graph theory and network analysis. Our approach is as follows:

6.1. Mathematical Framework

We begin with an adjacency matrix

A, where

represents the strength of influence of problem

i on problem

j:

where

, representing no, weak, moderate, and strong influence respectively.

We construct a directed weighted graph , where:

V is the set of vertices (our global problems)

E is the set of edges (the influences between problems)

is a weight function assigning each edge a weight based on the strength of influence

For each pair of vertices

, we create an edge

if

, with weight:

To assess the overall importance of each problem in the network, we calculate the weighted out-degree centrality:

This sum represents the total strength of influences for each problem on others.

6.2. Intervention Simulation

To simulate an intervention, we identify the node with the highest weighted out-degree centrality as our starting point. We model the intervention as a significant improvement in this problem area, reducing its severity by 50%.

We then model cascading effects through the network using a propagation rule: for each outgoing edge from the intervened node, we reduce the severity of the connected problem by a percentage based on the edge weight:

Strong influence (3): 30% reduction

Moderate influence (2): 20% reduction

Weak influence (1): 10% reduction

This process is iterated multiple times to capture secondary and tertiary effects. The severity

S of a problem

i at iteration

is given by:

where is the set of neighbors influencing node i, and is the influence factor based on the edge weight from j to i.

The network analysis presented in

Figure 1 offers significant insights into the complex interdependencies among major global challenges, advancing our understanding of their systemic nature. This visualization empirically demonstrates the high degree of interconnectivity between issues such as climate change, food and water security, and education access, supporting the theoretical framework of systems thinking in global problem-solving. The varying edge weights reveal a nuanced hierarchy of influence, with some nodes, notably Climate Change (CC) and Food/Water Security (FWS), exhibiting disproportionate centrality. This finding corroborates previous research on the cascading effects of environmental factors on socio-economic issues (Smith et al., 2020). Furthermore, the network structure elucidates potential leverage points for intervention, suggesting that targeted efforts in highly connected nodes could propagate benefits throughout the system. For instance, the strong outgoing connections from Education Access (EA) to other nodes provide quantitative support for the long-standing hypothesis that improvements in education can catalyze progress across multiple domains (Johnson, 2018). Importantly, this analysis also reveals unexpected strong links, such as the influence of AI Governance (AI) on Education Access, highlighting emerging interdependencies in our increasingly technological society. By quantifying these relationships, this network analysis not only validates qualitative assessments of global challenge interactions but also provides a rigorous foundation for evidence-based policy making and resource allocation in addressing these interconnected global issues.

7. Discussion

The network analysis of global challenges presented in this study offers a novel quantitative approach to understanding the complex interdependencies among critical issues facing humanity. Our findings reveal several key insights that have significant implications for policy-making, resource allocation, and future research directions.

Firstly, the high degree of interconnectivity observed in the network underscores the necessity of adopting holistic, systems-thinking approaches to global problem-solving. The dense web of connections between nodes such as Climate Change (CC), Food/Water Security (FWS), and Education Access (EA) empirically supports the theoretical framework that these challenges cannot be effectively addressed in isolation [

52]. This finding aligns with recent calls for integrated approaches to sustainable development [

53] and provides a quantitative basis for such strategies.

The identification of highly central nodes in the network, particularly Climate Change and Food/Water Security, corroborates existing literature on the far-reaching impacts of environmental factors on socio-economic issues [

54]. However, our analysis goes further by quantifying the relative strength of these influences, providing a more nuanced understanding of their importance. This hierarchical structure of influence suggests that targeted interventions in these key areas could potentially yield cascading benefits throughout the system, offering a data-driven approach to prioritizing global efforts.

Interestingly, our analysis also reveals some unexpected strong connections, such as the significant influence of AI Governance on Education Access. This finding highlights emerging interdependencies in our increasingly technological society and suggests new avenues for research and policy consideration. As artificial intelligence continues to permeate various sectors, including education, understanding and managing its governance becomes crucial for ensuring equitable and effective educational outcomes [

55].

The strength of Education Access as a node with numerous outgoing connections provides quantitative support for the long-standing hypothesis that improvements in education can catalyze progress across multiple domains [

56]. This result suggests that investments in global education could serve as a powerful lever for addressing a wide range of interconnected challenges, from improving public health to fostering technological innovation.

However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. The network model, while comprehensive, is a simplification of extremely complex real-world relationships. The linear nature of our influence propagation model may not fully capture the non-linear dynamics often present in complex systems. Furthermore, the weights assigned to edges in the network, while based on expert assessment, contain an inherent degree of subjectivity that could influence the results.

Future research could address these limitations by incorporating dynamic, non-linear models of influence propagation and by validating edge weights through extensive empirical studies. Additionally, expanding the network to include a broader range of global challenges and exploring how the network structure evolves over time could provide valuable insights into the changing landscape of global issues.

In conclusion, this network analysis provides a rigorous, quantitative foundation for understanding the interconnected nature of global challenges. By revealing key leverage points and unexpected relationships, it offers valuable guidance for policymakers, researchers, and practitioners working to address these critical issues. As we continue to grapple with complex, interconnected global problems, such data-driven approaches will be essential in informing effective, holistic strategies for creating a more sustainable and equitable world.

References

- Roy, A. Decolonizing both researcher and research and its effectiveness in Indigenous research. Research Ethics 2018, 14, 1–24.

- Harding, S.G. The science question in feminism; Cornell University Press, 1986.

- Wajcman, J. Feminism confronts technology; John Wiley & Sons, 1991.

- Schiebinger, L.L. Has feminism changed science?; Harvard University Press, 1999.

- Harding, S. Objectivity and diversity: Another logic of scientific research; University of Chicago Press, 2015.

- Criado-Perez, C. Invisible women: Exposing data bias in a world designed for men; Random House, 2019.

- Noble, S.U. Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism; NYU Press, 2018.

- Harding, S.G. The science question in feminism; Cornell University Press, 1986.

- Wajcman, J. Feminism confronts technology; John Wiley & Sons, 1991.

- Schiebinger, L.L. Has feminism changed science?; Harvard University Press, 1999.

- Criado Perez, C. Invisible women: Exposing data bias in a world designed for men; Chatto & Windus, 2019.

- Kern, L. Feminist City: Claiming Space in a Man-made World; Verso Books, 2020.

- Griffith, J.M.; Paulus, M.P.; Farahani, S.; Thompson, W.K. Network approaches to understand individual differences in brain connectivity: opportunities for personality neuroscience. Personality Neuroscience 2021, 4.

- Greer, B.; Robotham, D.; Simblett, S.; Curtis, H.; Griffiths, H.; Wykes, T. The COVID-19 pandemic and the future of telemedicine. Journal of Medical Systems 2020, 44, 1–3.

- Gallopín, G. A systems approach to sustainability and sustainable development. CEPAL - SERIE Medio ambiente y desarrollo 2003.

- Tsai, C.C.; Chiang, Y.T.; Shen, Y.X. The impact of social network analysis on education. Educational Technology & Society 2020, 23, 1–13.

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review 1991, 43, 1241–1299. [CrossRef]

- Kimmerer, R.W. Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants; Milkweed Editions, 2018.

- Hipólito, I.; Khanduja, A. The Wicked and the Complex: A New Paradigm for Societal Problem-Solving 2024.

- Subramaniam, B. Ghost stories for Darwin: The science of variation and the politics of diversity. University of Illinois Press 2014.

- Hipólito, I.; Winkle, K.; Lie, M. Enactive artificial intelligence: subverting gender norms in human-robot interaction. Frontiers in Neurorobotics 2023, 17, 1149303. [CrossRef]

- Venditti, V. The utopian dimension of new technologies: A feminist technophilosophical approach to sex and gender. In Feminist philosophy and emerging technologies; Routledge, 2024; pp. 129–148.

- Edwards, M.L.; Palermos, S.O. Feminist philosophy and emerging technologies; Routledge, 2023.

- Gardner, P.M.; Rauchberg, J. Feminist Cybernetic, Critical Race, Postcolonial, and Crip Propositions for the Theoretical Future of Human-Machine Communication. Human-Machine Communication 2024, 8, 2. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S. Crisis epistemologies: a case for queer feminist digital ethnography. Journal of Gender Studies 2023, 32, 486–497. [CrossRef]

- Weber, J. From science and technology to feminist technoscience. In Women, Science, and Technology; Routledge, 2013; pp. 543–556.

- Mazure, C.M.; Jones, D.P. Twenty years and still counting: including women as participants and studying sex and gender in biomedical research. BMC women’s health 2015, 15, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Regitz-Zagrosek, V.; Seeland, U. Sex and gender differences in myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure. Circulation Journal 2012, 76, 1703–1710.

- As-Sanie, S.; Black, R.; Giudice, L.C.; Valbrun, T.G.; Gupta, J.; Jones, B.; Laufer, M.R.; Milspaw, A.T.; Missmer, S.A.; Norman, A.; others. Assessing research gaps and unmet needs in endometriosis. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 2019, 221, 86–94. [CrossRef]

- Loh, J. Feminist Ethics and AI: A Subfield of Feminist Philosophy of Technology. In Handbook on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence; Edward Elgar Publishing, 2024; pp. 274–287.

- Hotez, P.J.; Molyneux, D.H.; Fenwick, A.; Kumaresan, J.; Sachs, S.E.; Sachs, J.D.; Savioli, L. Control of neglected tropical diseases. New England Journal of Medicine 2007, 357, 1018–1027. [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, C. Sheltering: Care Tactics for Ethnography Attentive to Intersectionality and Underrepresentation in Technoscience. Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Mavhunga, C.C. What do science, technology, and innovation mean from Africa?; MIT Press, 2017.

- Baizabal, E. From Cyberfeminism and Technofeminism to an Ontological and Feminist Technology. Women Philosophers on Economics, Technology, Environment, and Gender History: Shaping the Future, Rethinking the Past 2023, p. 109.

- Buolamwini, J.; Gebru, T. Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. Conference on fairness, accountability and transparency. PMLR, 2018, pp. 77–91.

- Raji, I.D.; Buolamwini, J. Actionable auditing: Investigating the impact of publicly naming biased performance results of commercial AI products. Proceedings of the 2019 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society 2019, pp. 429–435.

- Hipólito, I. The human roots of Artificial Intelligence: a commentary on Susan Schneider’s Artificial You. Philosophy East and West 2024, 74, 297–305. [CrossRef]

- Bolukbasi, T.; Chang, K.W.; Zou, J.Y.; Saligrama, V.; Kalai, A.T. Man is to computer programmer as woman is to homemaker? debiasing word embeddings. Advances in neural information processing systems 2016, 29.

- Obermeyer, Z.; Powers, B.; Vogeli, C.; Mullainathan, S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science 2019, 366, 447–453. [CrossRef]

- Dastin, J. Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women. Reuters 2018.

- Crawford, K. The trouble with bias. Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, invited speaker 2017.

- Sherman, J. Black Feminist Technoscience: Sojourner Truth, Storytelling, and a Framework for Design. Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Designing Interactive Systems Conference, 2023, pp. 978–986.

-

arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.06165, Gebru, T. Oxford handbook on AI ethics book chapter on race and gender. arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.06165 2019. arXiv:1908.06165 2019.

- Schurr, C.; Marquardt, N.; Militz, E. Intimate technologies: Towards a feminist perspective on geographies of technoscience. Progress in Human Geography 2023, 47, 215–237. [CrossRef]

- Toupin, S. Shaping feminist artificial intelligence. New Media & Society 2024, 26, 580–595.

- Carraro, V. Map fetishism and the power of maps: A feminist-technoscience perspective. In The Routledge Handbook of Cartographic Humanities; Routledge; pp. 200–207.

- Turnhout, E.; Dewulf, A.; Hulme, M. What does policy-relevant global environmental knowledge do? The cases of climate and biodiversity. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2016, 18, 65–72. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.W.; Alegria, S.; Børjeson, L.; Etzkowitz, H.; Falk-Krzesinski, H.J.; Joshi, A.; Leahey, E.; Smith-Doerr, L.; Woolley, A.W.; Schiebinger, L. Gender diversity leads to better science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, 1740–1742. [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, J. Bodily Fluids, Fluid Bodies and International Politics: Feminist Technoscience, Biopolitics and Security; Policy Press, 2024.

- Meskus, M. Speculative feminism and the shifting frontiers of bioscience: envisioning reproductive futures with synthetic gametes through the ethnographic method. Feminist Theory 2023, 24, 151–169. [CrossRef]

- Jungnickel, K. Speculative sewing: Researching, reconstructing, and re-imagining wearable technoscience. Social Studies of Science 2023, 53, 146–162. [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in systems: A primer; Chelsea Green Publishing, 2008.

- United Nations. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. General Assembley 70 session 2015.

- Carleton, T.A.; Hsiang, S.M. Climatic change and human potential. Science 2016, 353, 1518–1519.

- Holmes, W.; Bialik, M.; Fadel, C. Artificial intelligence in education. The Cambridge Handbook of Artificial Intelligence 2019, 1, 525–537.

- Hanushek, E.A.; Woessmann, L. The role of cognitive skills in economic development. Journal of economic literature 2008, 46, 607–668. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).