1. Introduction

Solar salterns, renowned as extreme environments with salinities at or near saturation, are artificial thalassohaline-hypersaline ecosystems widely distributed worldwide. They capitalize on salinity gradients for solar salt production. The traditional method of solar salt-making involves concentrating brine and precipitating NaCl through natural evaporation in a series of interconnected ponds, each linked to the other through a common opening [1-5]. In addition to serving as excellent models for studying microbial diversity and ecology at various salt concentrations, marine solar salterns are valuable for investigating phenomena such as scarce water availability and desiccation, which are linked to ongoing global climate change [

1]. Furthermore, they represent a valuable resource for exploiting extremophiles living at high saline concentrations, as they can be a source of unique enzymes with potential biotechnological applications [6-8]. Solar salterns sustain high microbial densities (10

7–10

8 cells/mL) due to the absence of predation and the presence of high nutrient concentrations [

9]. Numerous studies have investigated the diversity of coastal solar salterns across various geographic regions, including Africa [

10,

11], Asia [12-15], Australia/Oceania [

16], North and South America [

17], and Europe [6, 18-22].

The prokaryotic community of solar saltern brines has been the subject of study for decades, employing various approaches ranging from classical cultivation to culture-independent techniques. The composition of microbial communities in salterns is considered stable over time [

23,

24]

and is strongly influenced by salinity levels.

Culture-independent studies conducted on low salinity samples (40–70 g/L) revealed a microbial community composition similar to that of marine environment, with bacterial phyla predominant including Pseudomonadota, Cyanobacteriota, Bacillota, Bacteroidota, Actinomycetota, and Mycoplasmatota. At moderate salinity levels (130–180 g/L), bacterial phylotypes coexist with archaeal representatives of Halobacteriota. In contrast, high salinity samples (>250 g/L) from solar salterns are characterized by a dominance of halophilic archaea, especially members of the families Haloarculaceae, Halobacteriaceae and Haloferacaceae, along with a minor contribution from bacterial phylotypes, mainly belonging to the Bacteroidota of the class Rhodothermia, family Salinibacteraceae [

25]

. Additionally, numerous studies have demonstrated that during the salt-making process, microbial communities, primarily consisted of haloarchaea, become trapped within halite a in salt-saturated environments, thereby avoiding the harsh, MgCl

2-enriched bittern brine that remains after halite precipitates [

26,

27].

In this work we studied extremely halophilic prokaryotic communities, thriving in the salt crystallizer ponds of the Hon Khoi solar saltwork fields (HKsf), South Vietnam. This area is located in the Khanh Hoa Province (14°34’23’’N; 109°13’42”E), approximately 40 km from Nha Trang. Here, natural salt is harvested manually, without the use of heavy machinery, from shallow fields along Doc Let Beach. HKsf, covering an area of almost 400 hectares, is one of the largest salt making areas in Vietnam, with production reaching almost 740,000 tons of salt per year, accounting for a third of Vietnam's salt production. The salt harvesting season in the Hon Khoi salt fields occurs from January to July every year, with April to June considered the optimal time to obtain high-quality salt due to scorching temperatures during this period, accompanied with relatively low level of precipitation. Unlike the European method of collecting salt once or twice a year, in HKsf the process is multiply repeated. In short, seawater is directed from the East Sea into pre-drainage channels or basins, then into shallow pits (less than 50 cm depth) where the brine is left to evaporate for a very short period of time, usually no more than 10 days, after which the salt is manually extracted from these shallow pits, piled up and tracked away, and the pits are refilled with brine.

The diversity of extreme halophilic microbiota of HKsf salterns remains unexplored, thus potentially representing a hidden source of enzymes and secondary metabolites of high biotechnological demand. To fill this gap, an in-deep metabarcoding approach was conducted to study the prokaryotic diversity of crystallizer ponds and to characterize the bacterial and archaeal communities of HKsf salterns by comparing them with those of decommissioned solar salterns in North Vietnam, as well as with Italian saltwork fields located in Trapani and Motya (Sicily, Italy). Particular attention was paid to the phylogenetic analysis of bacteria and archaea, respectively belonging to the superphylum

Patescibacteria, also called Candidate Phyla Radiation (CPR), and to the superphylum DPANN (this acronym comes from

Diapherotrites,

Parvarchaeota,

Aenigmarchaeota,

Nanoarchaeota and

Nanohaloarchaeota candidate phyla). Members of these newly discovered taxa are typically ultra-small in size, with an average cell diameter of 200–450 nm, possess highly reduced genomes (average size 1 Mbp) and minimal cellular activities, including limited metabolic potential [28-30]. As a consequence, these nano-sized organisms have adopted an obligate symbiotic or predatory lifestyle, relying entirely on their respective prokaryotic hosts [29,31-35]

. They are extremely phylogenetically diverse, ubiquitous and abundant in microaerobic and/or anaerobic zones of freshwater lakes, sediments, and groundwater [

29,

31]. However, there is very little evidence for the presence of both CPR and DPANN in hypersaline environments, and only members of the phylum

Nanohaloarchaeota are commonly found worldwide in natural salt and alkaline lakes, marine solar brines, and deep-sea hypersaline anoxic basins [14,24,36-44].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

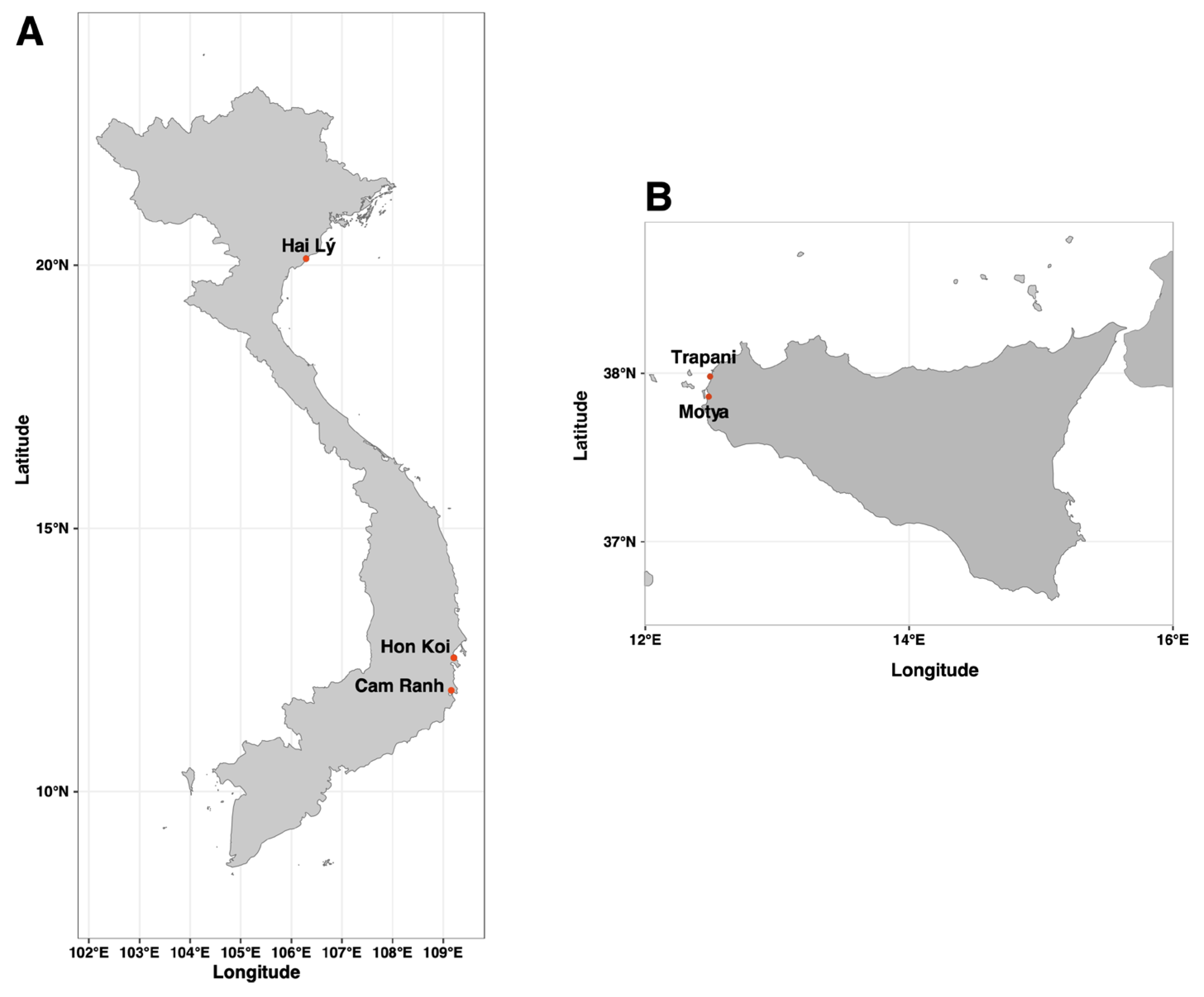

Two Vietnamese artisanal marine solar saltwork fields were chosen for sampling: the

Hon Khoi Salt Fields, Nha Trang, Khanh Hoa Province (14°34’23’’N; 109°13’42”E), one of the largest salt-making areas in Central Vietnam and Hai Lý, Hai Hau, Nam Dhin Province (20°07’20.676’’N; 106°17’45.959’’E), locally decommissioned salt fields in northern Vietnam. Commercial salt sample was additionally collected from a Nuoc Mam fish sauce factory in Thành phố Cam Ranh (Khanh Hoa Province), 60km south-east of Nha Trang. For Italy, samples were collected from multiple artisanal solar saltworks in western Sicily: Trapani Salterns (37°58’49.90’’N 12°29’42.00’’E) and Motya Salterns (37°51′48.70′′ N, 12°29′02.74′′E) (

Figure 1). Sampling took place in 2022 (June and September) and 2023 (June). Brine temperature, salinity and pH was measured directly at the sampling site using conventional thermometer, refractometer and pH meter (

Table 1).

2.2. Geochemical Analyses and Salinity-Related Measurements

Correct quantification of anions and cations in hypersaline samples is a rather challenging analysis; in fact, the matrix shows high complexity due to both the variety of species in solution and the different concentration ranges in which they are present. Quantification of the major ions in this type of samples, such as chloride or sodium, is usually not a problem. However, the determination of other ionic species can be affected by lack of selectivity [

45] and matrix effects [

46]. Ion chromatography (IC) have been used to determine the anion composition of hypersaline samples, using the EPA Method 300.1 1997. Ion chromatography with conductometric detection is the most popular technique for this determination due to its selectivity and sensitivity. The standard addition method has been used to compensate for matrix effects [

46]. For quantification of cations, analyses were performed with ICP-AES using the EPA Methods 3005 1992 and 6010D 2018.

2.2.1. Anions Analysis

The ion chromatograph was a Dionex ICS-3000 equipped with an IP20 isocratic pump, a 25 µL loop, an IonPac AS9-HC separation column with an AG9-HC precolumn and a conductivity detector CD20 with a 4 mm ASRS Ultra II suppressor. Chromeleon chromatography Data System (CDS) software was used for instrument control, data acquisition and processing. The chromatographic and detection conditions were optimized to obtain an adequate resolution of peaks and sensitivity. The instrumental conditions were 9 mM Na2CO3, flow rate of 1.0 mL/min, and expected background conductivity of 24-30 µS. In the presence of very high chloride concentration, the efficiency of early eluting peaks would be compromised due to the overloading effect. Pretreatment of the samples with Dionex OnGuard Ag followed by Dionex OnGuard H significantly reduce chloride and carbonate content, allowing accurate quantification. All chemicals used to prepare standard solutions were of analytical-reagent grade, namely NaCl (≥99.8 %) from Riedel-de Haën, NaBr (≥99.7 %) from BDH Prolabo, NaNO3 (≥99.0 %) and Na2SO4 (≥99.0 %) from Merck. Na2CO3·10H20 (≥99.0 %) from Merck were used to prepare the eluent. All solutions were prepared with ultrapure water obtained from a Milli-Q Academic system (Millipore). The impurities of the various salts did not affect the content of the other analytes significantly. Duplicate samples, were also analyzed.

2.2.2. Cations Analysis

Analysis of Na+, K+, Mg2+ and Ca2+ was performed using a Perkin Elmer OPTMA 7300 DV Inductively Coupled Plasma - Atomic Emission Spectrometry (ICP-AES). Hypersaline samples contain more than 3 percent dissolved salts, which cause problems such as uneven sample transport rates and chemical and spectral interferences. Samples were solubilized by acid digestion with a suitable mixture of HNO3 and HCl. The sample was then subjected to heating and reduced in volume. In the presence of particulate matter, after cooling, filtration was performed and then brought to the final volume for subsequent analytical determinations using the mentioned ICP-AES technique. Both analytical methods for anions and cations determination were carried out by Eni Rewind Priolo Environmental Laboratory, which is accredited ACCREDIA/ILAC for EPA 300.1 1997 and EPA 3005 1992 and EPA 6010D 2018 methods, with the number 0119L.

2.3. DNA Extraction and Purification

Brine samples (50-100 50 mL) were filtered through sterile Sterivex capsules (0.2 µm pore size, Merck Millipore). 10 g of salt samples were weighted and dissolved in prefiltered MilliQ water (final volume 40 mL); obtained solution was filtered through 0.2 µm pore size membranes supported on swinnex filter holder 25mm diameter (Merck Millipore, Germany). For each sample, filters were then used for DNA purification together with sterivex capsules. Genomic DNA from sediments was extracted using protocol of Hurt et al. [

47]. Total DNA from both Sterivex and membrane filters was extracted using GNOME DNA kit (MP biomedicals, USA). The extraction was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was visualized on agarose gel (0.8% w/v). Quantity of DNA was estimated by QubitTM 4 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and metagenomic analysis and

16S rRNA Gene Amplicons were performed.

2.4. Next Generation Sequencing

For sequencing 16S rRNA gene amplicons, the V3–V4 hypervariable region of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene was sequenced using the primers previously described by Klindworth and coauthors [

48]. DNA samples were PCR amplified and the amplicons were sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq platform by a commercial company (Macrogen Inc., Seul, Korea) (

http://dna.macrogen.com/main.do). Libraries preparation followed by Illumina sequencing were performed according to standard protocols [

49]. Sequences were deprived of barcodes and primers, then sequences <150 bp together with sequences with ambiguous base calls and with homopolymer runs exceeding 6 bp were removed.

2.5. NGS Data Analysis

Reads were imported in RStudio package [

50] and analyzed using the DADA2 package (v 1.26.0) [

51], as described in Crisafi et al. [

52]. PCR biases were removed applying a parametric error model constructed between the estimation of error rate and the inference [

51]. Chimeric sequences were identified and removed, then the taxonomy was assigned using a DADA2 implementation of the naive Bayesian classifier method versus the Silva Database v138 (v138;

https://www.arb-silva.de/documentation/release-138). The taxonomy table obtained (AVSs abundance table) was processed in R by means of Phyloseq, Vegan and Microbiome packages [53-55].

2.6. Statistical Analyses

A Phyloseq object was created from DADA2 results, possible contaminants and low abundance ASVs (less than five reads) were removed. Diversity analyses were performed using Phyloseq and Microbiome packages [

53,

54]. For each sample analyzed alpha diversity was investigated for Shannon, Simpson and Chao1 index. Beta diversity was calculated with UNIFRAC (weighted and unweighted distances), and the Jaccard and Bray-Curtis coefficients. R microeco package was used to perform the Mantel’s test among phylum abundance table and environmental variable [

56].

2.7. Establishing of Polysaccharide-Degrading Enrichments and Isolation of an Axenic Xylanolytic Culture

Freshly harvested halite samples VCR and STP (5 g each) were used to establish polysaccharide-degrading enrichments. Based on knowledge of the successful isolation and maintenance of both chitino- and xylanolytic cultures [

32,

33], the same

Laguna Chitin (LC) liquid mineral medium was used. For initial enrichments, 5 g of VCR halite was added to 70 mL of the LC medium, supplemented with either beechwood xylan (Megazyme, catalogue number P-XYLNBE-10G) or pectin from citrus peel (Sigma Alrdich, catalogue number P9135). Both polysaccharides were sterilized separately by autoclaving and then added at a final concentration of 2 g/L, to serve as growth substrates. The bacterium-specific antibiotics vancomycin and streptomycin were added (100 mg/L of each, final concentration) to prevent the growth of any halophilic bacteria. The same procedure was carried out for the STP halite sample, collected from artisanal solar saltworks in Trapani. All four enrichments were incubated at 40°C in tightly sealed 120-mL glass serum vials in the dark and without shaking for two to three months. The isolation strategy for axenic xylanolytic cultures consisted of several rounds of decimal-dilution transfers (each inoculation to fresh medium being a 10-fold dilution) to obtain active polysaccharidolytic enrichments, followed by a three-fold repetition of serial dilution-to-extinction. The presence of

Nanohaloarchaeota in obtained enrichments was continuously monitor by PCR using the specially designed taxon-specific primers [

32] and their 16S rDNA was cloned and sequenced.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition of Saltwork Fields

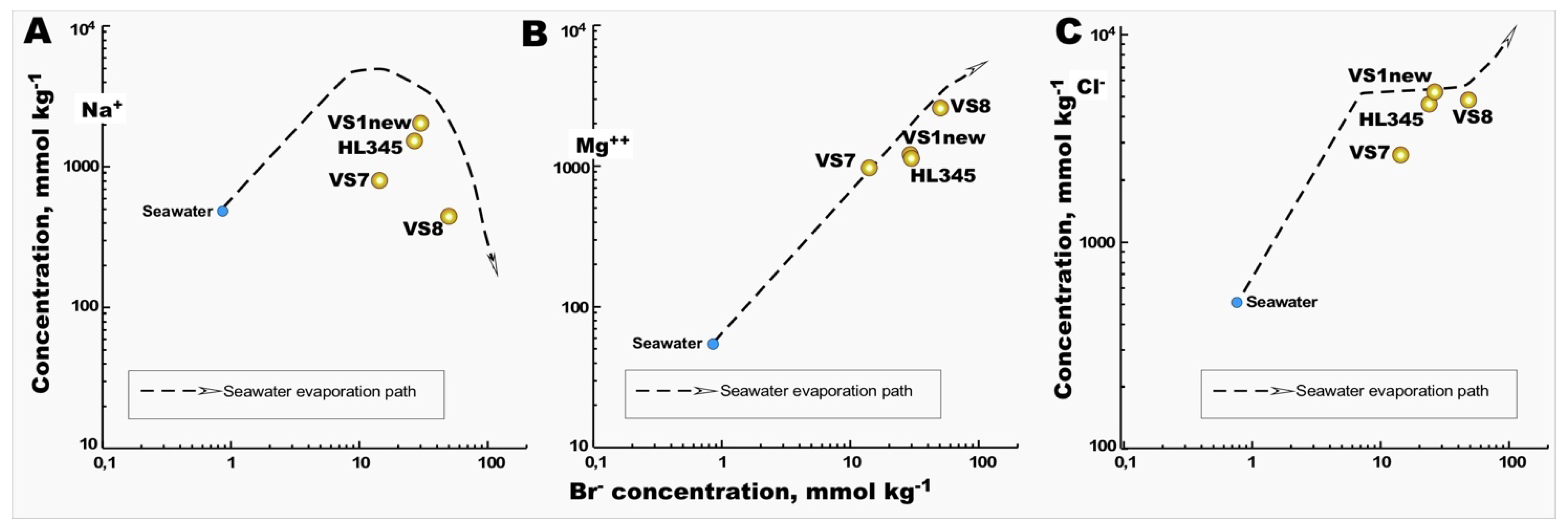

Among all 9 sites sampled from Vietnam saltwork fields, physicochemical analyses were carried out at four geographically representative locations (

Table 2). The striking differences between the three HKsf samples contrasted with the high similarity of hydrochemical settings of the VS1 (HKsf) and Hai Ly crystallizer ponds. In both, an intermediate stage of transition from thalasso- to athalassohaline composition of brines was noted. On average, the predominance of major cations in these samples was in the order of Mg

2+ > Na

+ >> K

+ >> Ca

2+, compared to seawater proportions Na

+ >> Mg

2+ > K

+ ≥ Ca

2+ (

Table 2). Considering, that these brines are nearly nine times more saline than seawater, these data are quite similar to those reported for the initial phase of late-stage evaporitic brines, formed during the evaporation path of seawater [

57]. At this stage, halite begins to form, and this process is accommodated by the relative increase of Mg

2+ cation, remaining in the brine, compared to the sodium precipitating. Differently, the VS8 brine is characterized by a high enrichment in the Mg

2+ cation (2.75M), along with a noticeable drop in sodium in the brine by more than 4.4 times and 20% less, compared to the VS1 and Hai Ly brines and initial seawater content, respectively. Thus, the VS8 brine at the time of sampling represented the final phase of seawater evaporation path, in which only a minor quantity of sodium was still present. The hydrochemical setting of the VS7 brine, less saline than the other brines analyzed, was more interesting. Being 4.3 times saltier than seawater, it contained only 1.5 times more sodium, but the content of Cl

- and especially Mg

2+ and Br

- was 4, 17 and 14 higher, respectively. The relatively high concentrations of Mg

2+ and Br- are very indicative to understand the origin of the VS7 brine, since the concentration of these ions are reported to persist crystallization during seawater evaporation and they are not predominantly incorporated into most of precipitates [

57]. Considering Br

- as a model ion for comparison with the major ions Na

+ and Cl

- in brines, we noticed that VS7 deviates significantly from the seawater evaporation path in both plots, which was not the case with the Mg

2+ and Br

- correlation, which fully followed this path (

Figure 2). This unusual hydrochemistry is easily explained by the above-mentioned peculiarity of the salt harvesting process in Vietnam, namely the frequent reuse of crystallizer pounds throughout the year. In other words, after the removal of the precipitated halite, the bitter brine seems enriched in Mg

2+ and Br

-, which still remained in the VS7 pool in unknown quantities, was diluted with seawater, slightly evaporated in pre-drainage saline saltern pond(s) to continue the salt extraction process.

3.2. Alpha and Beta Diversity

To investigate the composition of prokaryotic community in different solar salterns and freshy harvested salt samples, representative

unique amplicon sequence variants (ASVs

) were analyzed and compared to the microbial reference database for the identification. After filtering, a total of 747,857 16S rRNA sequences were obtained, ranging from 4,028 to 61,118 sequences per sample, which belonged to a total of 4,900 distinct ASVs (

Table 3). Rarefaction curves with 99.9–100% coverage were obtained for each ASVs library processed (data not shown), indicating that the entire microbial community was sampled and represented in the sequencing data analysis. The Simpson and Shannon diversity indices, which take into account both species richness and species evenness, ranged from 12.12 to 320.05 and from 2.99 to 6.0, respectively. The highest value was obtained for sediment sample VS9, indicating higher diversity within its community. The lowest value was found in the freshly collected salt sample CP, which

correspondingly exhibits the lowest diversity.

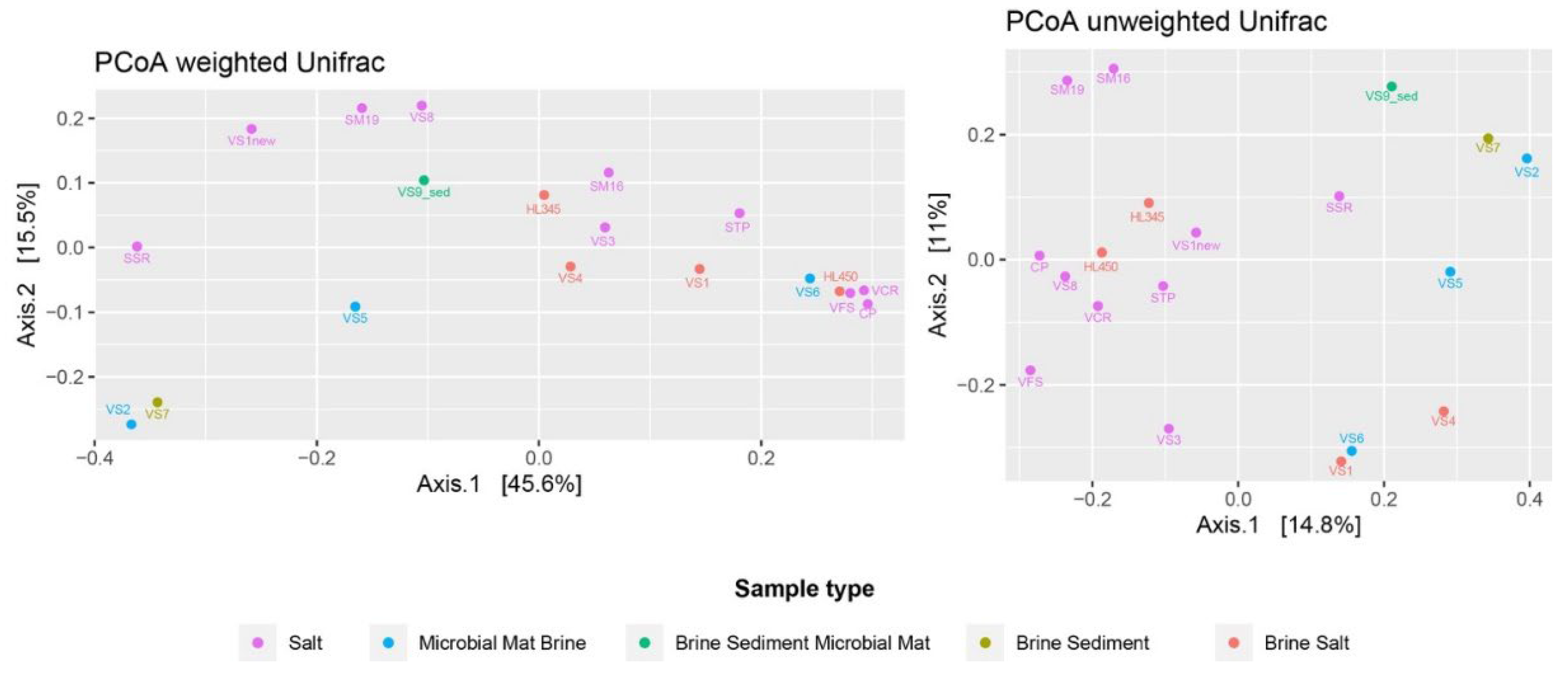

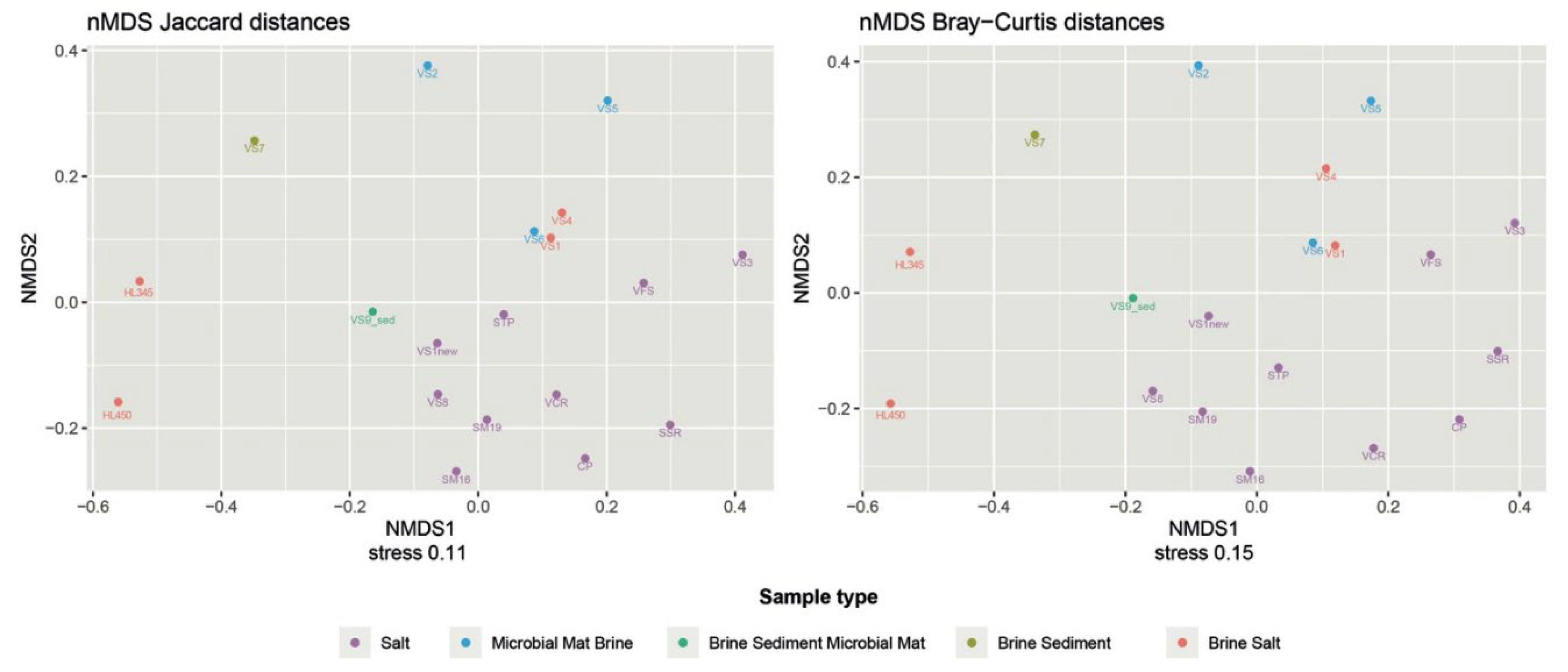

Beta diversity was measured as weighted and unweighted UniFrac and plotted as PCoA (Principal Coordinates analysis) (

Figure 3). PCoA analysis of microbial community data was used as valuable tool for exploring and visualizing the complex relationships between Italian and Vietnamese microbial communities.

Considering the varying abundances of different ASVs detected in each sample, the PCoA plot generated by the weighted UniFrac distance matrix shows that neither sample matrices, salinity, nor provenance are significant factors influencing the differences in microbial community composition between samples. The unweighted uniFrac distance, which only takes into account the presence and/or absence of different ASVs along with their phylogenetic distance, better reflects the similarities between samples. The freshly harvested halite samples were clustered together and far from the others. The stress value of 0.11 in the NMDS analysis using the Jaccard distance as the similarity metric can be considered acceptable and suggests that the NMDS plot provides a good representation of the relationships between samples in the microbial community compositions (

Figure 4). This was confirmed by Bray/Curtis analysis, which indicates that the spatial configuration obtained by the NMDS analysis closely approximates the similarities/dissimilarities in the sample data.

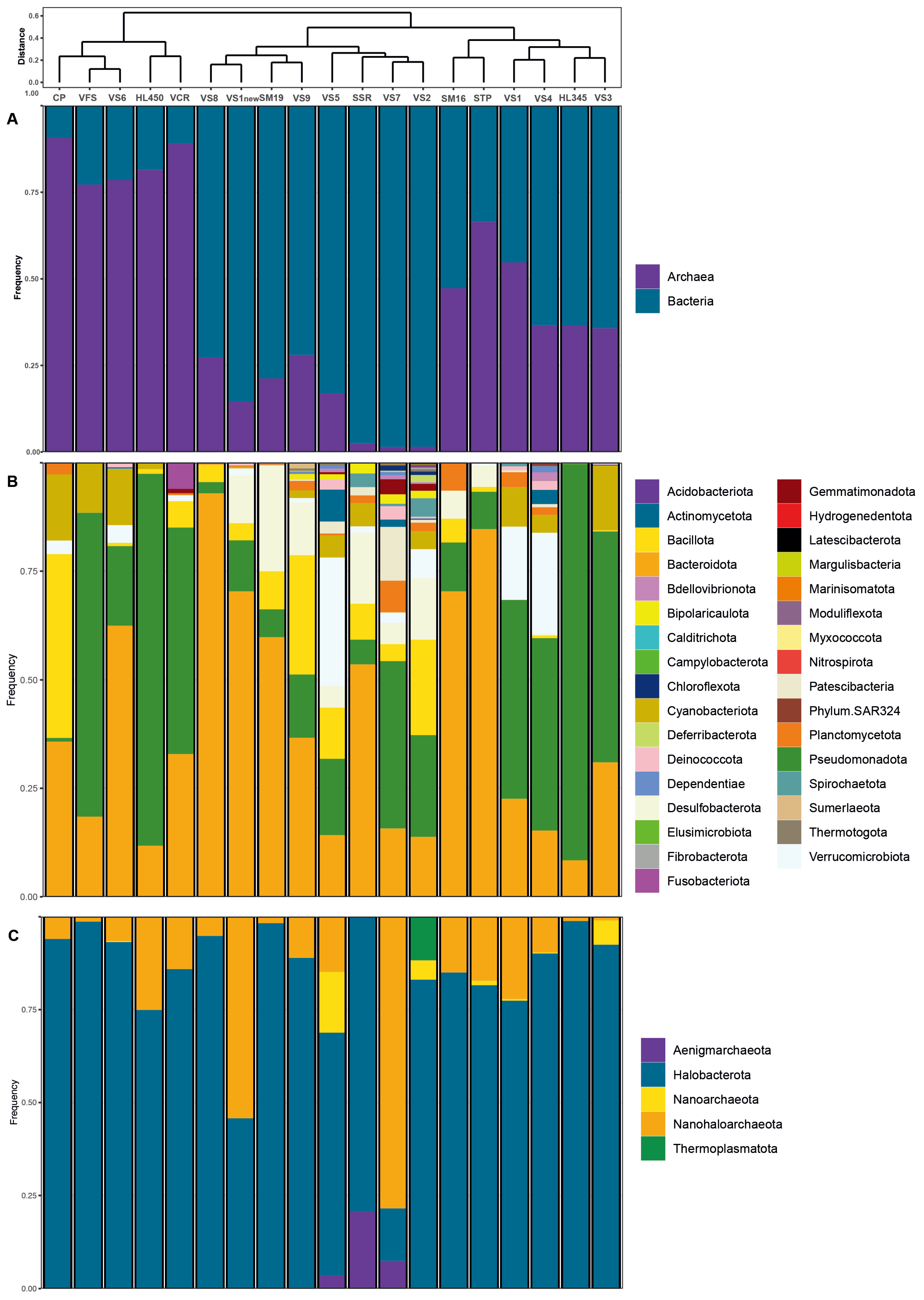

3.3. General Microbiome Profiling

The distribution of bacterial and archaeal taxonomic profiles is shown in

Figure 5. Within the samples, 280 bacterial genera belonging to 34 recognized phyla and 49 archaeal genera from 5 recognized phyla (GTDB taxonomy;

https://gtdb.ecogenomic.org/) in total were identified. Notably, archaeal abundance ranged from 80% to 90% in freshly harvested VFS halite and VS6 brine collected from Hon Khoi Salt Fields, as well as in commercialized salt VCR from Cam Ranh and Hai Lý brine (

Figure 5A). The site CP, freshly harvested halite of Motya (Italy), exhibited a similar predominance of archaea (91%). However, in other samples, which also included freshly collected halite samples and brines with salinities exceeding 250 g/L, archaeal presence ranged between 20% and 60%. This deviation was in some contrast to the results of previous studies [

24,

25,

58,

59] and may be attributed to the aforementioned distinct characteristics of Vietnamese solar salterns, numerous reusage of the crystallizer ponds with addition of slightly evaporated seawater (50-100 g/L) and the composition of the analyzed samples, which comprised a mixture of salts, sediments, microbial mats, and brines. The core tidyverse packages [

60] and phangorn [

61], dendextend [

62], vegan [

55], ggdendro [

63], ggsci [

64], cowplot [

65] libraries were used to create the bar charts with hierarchical clustering (

Figure 5).

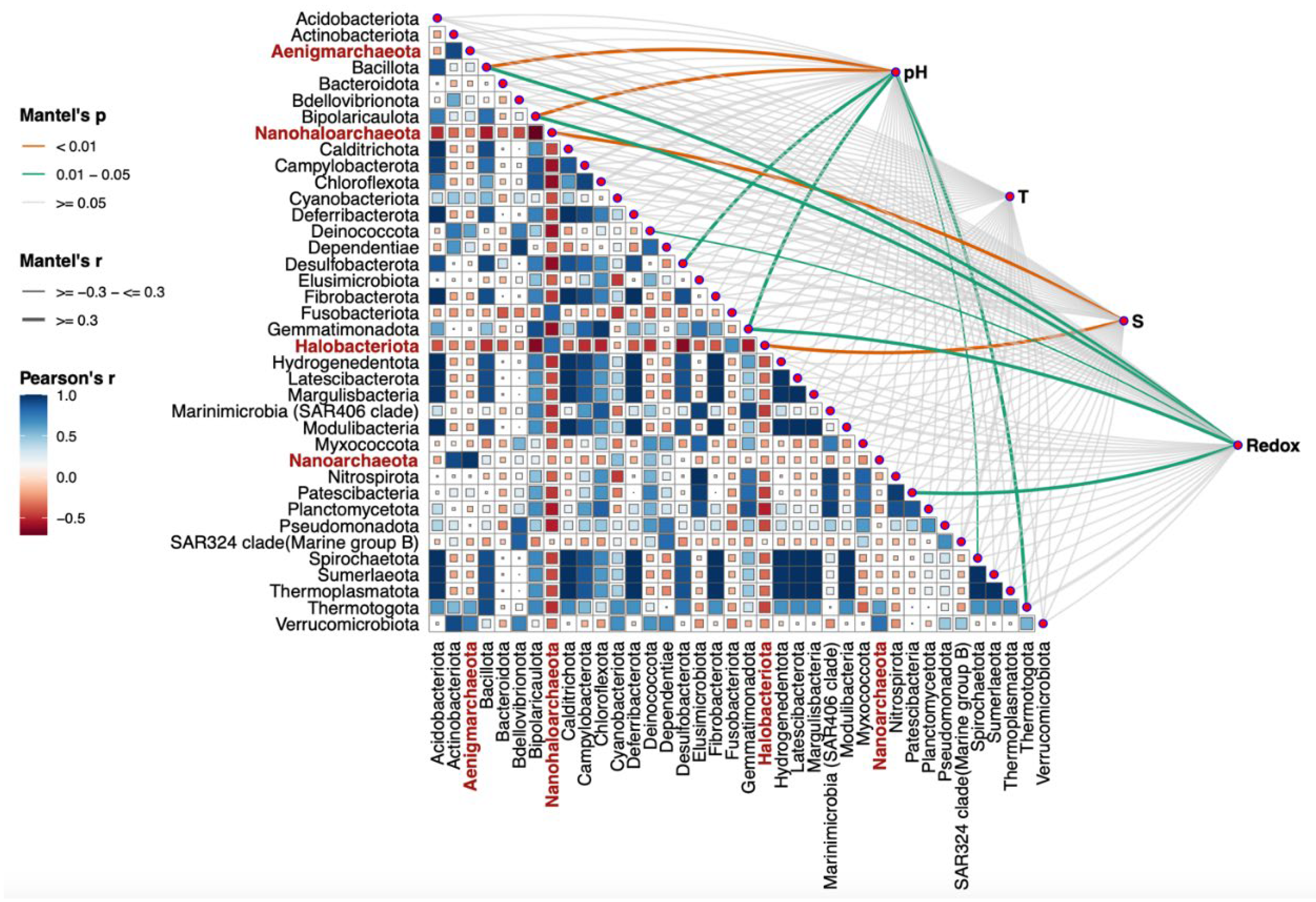

As me mentioned above, alpha and beta diversity data did not reveal a clear phylogenetic relationship or grouping of microbial populations by source location (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Additional statistical analysis was performed to monitor the environmental settings that are likely to be involved in the shaping of bacterial populations. Namely, the Mantel test using the

R microeco package [

56] was applied to evaluate the correlation between the main physicochemical parameters and the structure of the recognized microbial phyla, found in all the analyzed samples. Several important factors with significant

p and

r values, such as salinity, pH, temperature, and oxygen availability measured

in situ as redox potential, emerged to determine the presence or even abundance of a certain phylum (

Figure 6). The test was based on Bray–Curtis ASVs dissimilarity matrix. The

r value represents the correlation between the environmental factors and the ASVs matrix, while

p determines whether the correlation coefficient

r is statistically significant. The most statistically significant positive correlations were observed between salinity (S) and dominance of halophilic archaea belonging to the phyla

Halobacterota and

Nanohaloarchaeota (

Figure 6,

Table 4), as indicated by high

r values (0.899 and 0.663, respectively) and highly significant

p values (0.001 and 0.002, respectively). These findings suggest a direct relationship between increasing salinity and the abundance of these extremely halophilic archaeal groups, which is consistent with their physiology and inability to function under low salinity conditions. Strong positive correlations were also observed between pH and the dominance of the phyla

Bacillota and

Bipolaricaulota (p < 0.01) (

Figure 6,

Table 4). Their respective

r correlation coefficients of 0.503 and 0.852 indicate a substantial relationship between pH and the abundance of these bacterial groups. The same trend, although to a lesser extent, was observed between oxygen concentration, measured as reduction-oxidation potential, and the emergence of the phyla

Bacillota,

Bipolaricaulota,

Fusobacterota and

Patescibacteria. This observation is consistent with the fact that many representatives of these phyla prefer to thrive in microoxic and/or anaerobic environments.

3.4. Microbial Diversity of Brine, Sediments and Salt (Halite) Samples

Bacteroidota and

Pseudomonadota, were the dominant bacterial phyla consistently distributed across the salinity gradient and omnipresent in both Vietnamese and Italian samples during salt production (

Figure 5B). However, these phyla exhibited marked differences in abundance across sites.

Bacteroidota displayed a wide range, from a low of 8% at Hai Lý HL350 to a high of 92.9% at the hypersaline VS8 site (late-stage brine)

. Conversely,

Pseudomonadota demonstrated an opposite pattern, with a maximum abundance of 91.3% at Hai Lý HL350 and a minimum of 2.6% at VS8.

Bacillota was also a consistently detected phylum, though less abundant than

Bacteroidota and

Pseudomonadota, and was in most samples except the fresh salt from HKfs.

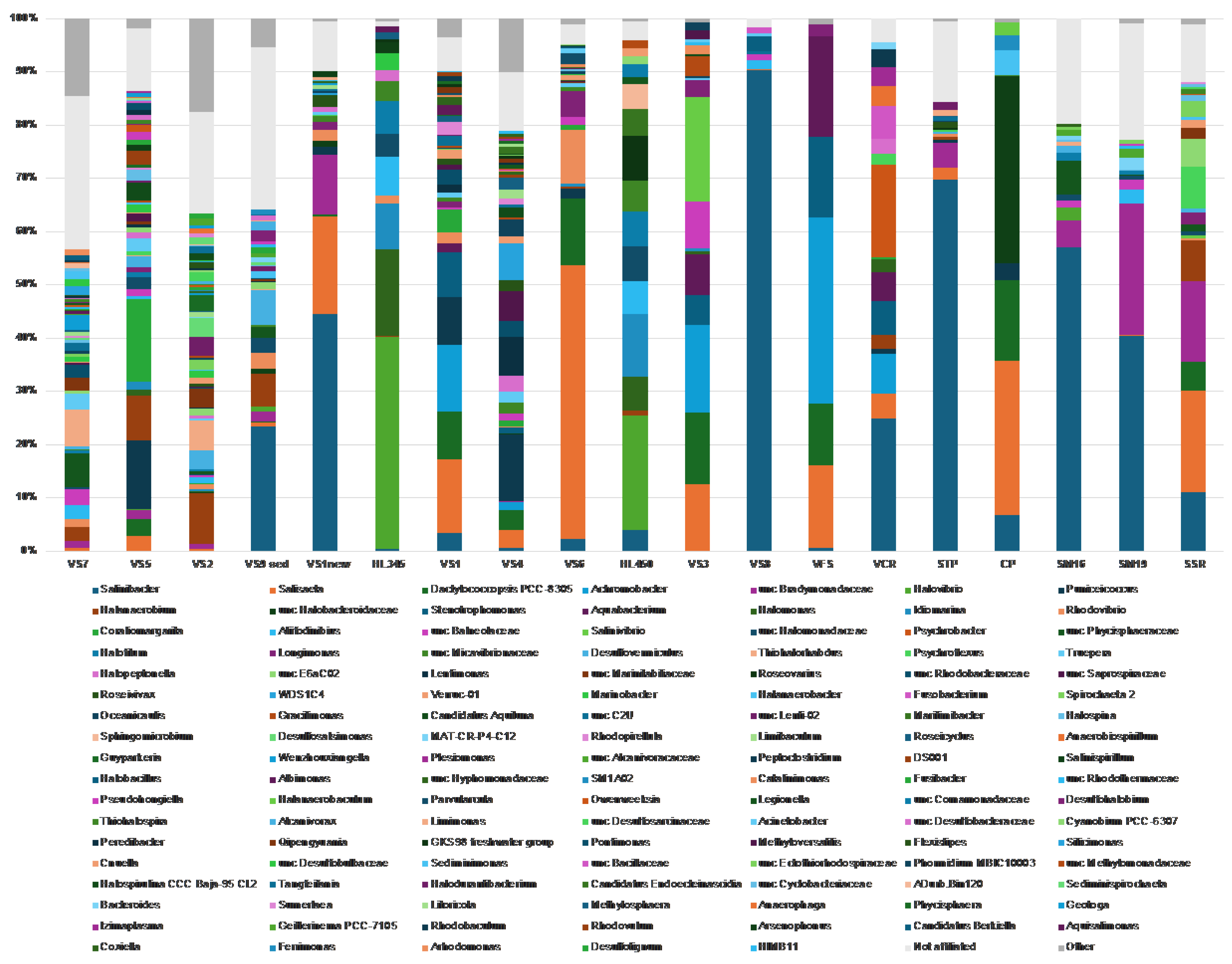

Desulfobacterota represented a smaller proportion of the community, ranging from 5 to 14.1% in anaerobic HKfs samples, with a peak abundance of 24.4% in the Italian salt sample SM19 (

Figure 5B). At the genus level (

Figure 7), ASVs belonging to the phylum

Pseudomonadota were primarily classified as

Gammaproteobacteria, representing over 50% of the bacterial community in both Hai Lý samples (86.2% and 61.2% in HL450 and HL345, respectively) and in Vietnamese salt samples VS3 (52.9%), VFS (70%), and VCR (52.2%).

Alphaproteobacteria, on the other hand, never exceeded 30% of the bacterial population, with a peak abundance of 28.8% in the VS4 (brine and salt) sample. Delving deeper into the genus level, members of the genus

Salinibacter of the phylum

Bacteroidota (former phylum

Rhodothermota) consistently appeared in all analyzed samples excluding HKsf less saline VS2, VS5 and VS7 brines. The highest relative abundance of

Salinibacter was observed in the both Italian and Vietnamese freshly harvested halite STP and VS8 brine (69.2% and 91.3%, respectively). It is well-know that

Salinibacter uses the ‘salt-in’ strategy known from the archaeal

Halobacteriota and is a major component of hypersaline aquatic ecosystems worldwide [66, for further references]. In contrast, to the ubiquitous

Salinibacter, the gammaproteobacterium

Halovibrio was exclusive to brine and predominated in the Hai Lý samples, comprising 45.8% and 38.75% of the community, respectively. Overall, brine samples exhibited a higher diversity compared to halite which indicated through the presence of sequences belonging to higher number of phyla and a correspondingly greater number of bacterial genera.

3.4. Microbial Diversity of Brine, Sediments and Salt (Halite) Samples

Among

Archaea,

Halobacterota was the dominant archaeal phylum in all but one tested samples (brines, microbial mats, and salts), accounting for up to 99% of the total archaeal communities in Hai Lý HL345 brine (

Figure 5C). In the VS7 brine, however, they represented only 14% of all archaea, likely due to the unusual hydrochemistry of this site mentioned above. Apparently, prior to our sampling, the precipitated halite had just been removed from the pool along with most of haloarchaeal cells embedded in the salt crystals, thus artificially enriching the remaining bitter brine with

Nanohaloarchaeota, which ultimately comprised 78.5% of the archaeal population. The members of

Aenigmarchaeota made up the remaining 7.5% of archaea in VS7 brine, and their presence in this brine is a likely the result of recent addition of slightly evaporated seawater from saltwork’s pre-drainage channels to repeat the salt harvesting process. Indeed, these typically marine archaea, first discovered and named as the “Deep Sea Euryarchaeotic Group” (DSEG) [

67], disappeared with increasing total salinity in the others, more saline brine samples. Representatives of two other archaeal phyla,

Thermoplasmatota and

Nanoarchaeota (former

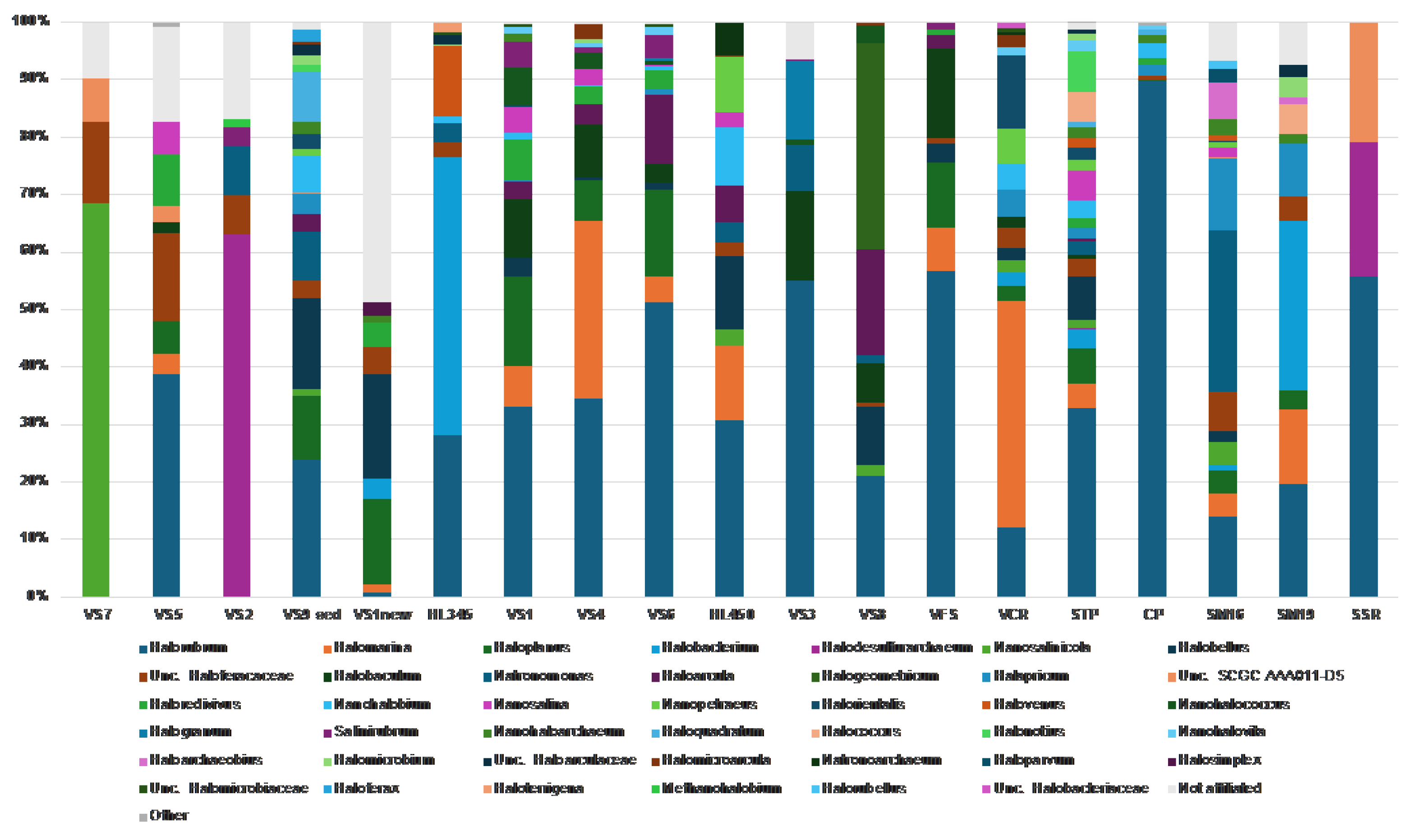

Woeasearchaeota) show the same tendency towards salinity intolerance and were found only in the less saline ponds VS2 and VS5, albeit in significant numbers (relative abundance 12-16%).

At the genus level, for

Halobacterota, we found a typical trend of increasing haloarchaeal diversity associated with increasing brine salinity [

6,

68,

69], with up to 20 haloarchaeal genera detected in the saltiest brines (

Figure 8). This is almost three times the number of haloarchaeal genera found in less saline samples (6 genera on average). In contrast to other studies conducted at European saltworks [

6,

27], which traditionally harvest halite once or twice a year, the multiple reusage of crystallization ponds in Vietnam apparently creates significant perturbations and structural instability in consortia. In fact, when examining the haloarchaeal community across all brine and halite samples, we did not detect any minimally defined structure at the genus level. They were all quite diverse, even those in close proximity. However, some interesting features were noticed, at least two of which deserves special attention. First, the genus

Halorubrum was found among the most represented taxa across the investigated brines and salts from solar salterns in both Vietnam and Italy (present in 17 of all 19 analyzed samples), reaching its highest relative abundances in freshly collected halite from CP (Italy) and VFS (Vietnam) with relative abundances of 90% and 57% of archaeal sequences, respectively (

Figure 8). Studies examining commercial salt derived from marine solar salterns [70-73] and ancient halite [74-77] have demonstrated that haloarchaea that dominate brine communities are often present at reduced abundance or undetectable in halite communities. This does not appear to be the case for

Halorubrum, as its dominance (up to 51% of relative abundance) was also detected in many of HKsf and Hai Lý brines (

Figure 8). These data correspond well with the dominance of

Halorubrum in the brines of solar salterns and freshly harvested halite of Trapani, where its mean relative abundance of 55.2% was detected [

27]. Secondly, the highest relative abundance of the genus

Halobaculum was found only in the Hon Khoi salt fields samples (up to 10% in brines and up to 16% in halite samples, respectively), while their minority or even absence was detected in all other analyzed samples, both Vietnamese and Italian. Though a study of

Halobacteria associated with halite crystals collected from coastal salterns of Western Europe, the Mediterranean, and East Africa, yielded little support for the existence of biogeographical patterns for this group of

Archaea [

66,

72], the presence of the genus

Halobaculum among the most represented taxa in the HKsf samples can be taken into consideration as a strong geographical connotation, which is quite indisputably linked to the Hon Khoi salt production area.

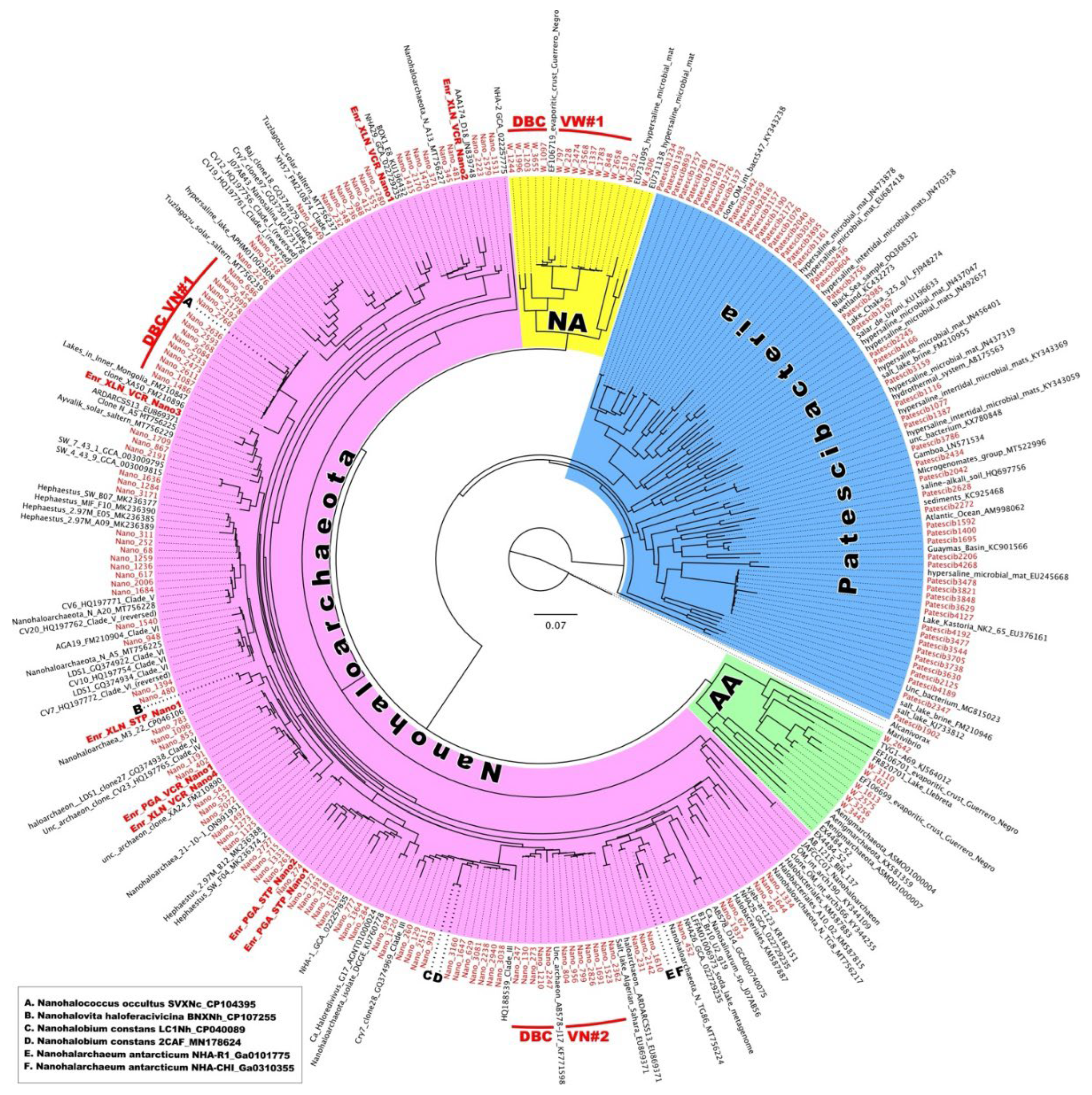

3.4. Diversity of Nano-Sized DPANN and CPR Microbiota.

To further explore the possible existence of biogeographical regionalization of halophilic microbial communities thriving in Vietnamese saltwork sites, we conducted an in-depth phylogenetic analysis of ultra-small prokaryotes belonging to DPANN

Archaea and CPR

Bacteria (

Figure 9). DPANN

Archaea are extremely diverse and have been found in a wide variety of environments on Earth, including marine sediments and waters, freshwater ecosystems, hot springs, microbial mats, and hypersaline systems, where mostly only

Nanohaloarchaeota thrive (Oren, 2024, for further references). However, there are some evidences of the presence and even dominance of

Woesearchaeota (now order

Woesearchaeales in the phylum

Nanoarchaeota) in halo-alkaline lakes and hypersaline sediments [

42,

78]. Representatives of this taxon were found in all HKsf brines and halite, reaching the 16.4% (VS5 brine) and 6.5% (VS3 halite) of all archaeal community, respectively. Most of the ASVs associated with HKsf

Woesearchaeota formed a deeply branched cluster DBCVW#1 together with a single similar riboclone Y9A (EF106719) (98.53 % of identity), recovered from the Guerrero Negro Baja endoevaporitic crust community [

79]. This appears to be a very specific halophilic cluster of

Woesearchaeales, as we could not find any other relative sequences in the NCBI database with more than 88% identity.

The phylum

Nanohaloarchaeota was expectedly abundant in all analyzed samples, reaching a peak relative abundance of 78.5% in the brine sample VS7 (

Figure 5C), likely for the reasons discussed above. Screening for the HKsf-specific signatures revealed the presence of at least two deeply branched clusters, found only in Hon Khoi brine and halite samples (

Figure 9). The first cluster, DBCVN#1, consisting of 14 distinct ASVs, was most similar (93.7% - 97.2% identity) to cultured nanohaloarchaeon

Candidatus Nanohalococcus occultus [

33,

80] with no other related sequences in the NCBI database possessing greater than 93% identity (it is worth to notice that all riboclones similar at this level were recovered exclusively from Asian hypersaline lakes). The second cluster, DBCVN#2, consisting of 12 distinct ASVs, was most similar (97.98% identity) to four riboclones AB576-D04, AB577-G21, AB577-N13 and AB578-J17, all recovered from Santa Pola salterns (Spain) [

81]. The next similar nanohaloarchaeon with 95.1% identity was cultured

Candidatus Nanohalobium constans [

32]. Both these cultured nanohaloarchaea are characterized by their interspecies interactions with polysaccharidolytic haloarchaea, which can be assigned to the classical types of either mutualistic symbiosis or pure commensalism.

Candidatus Nanohalobium is associated with a chitin-degrading

Halomicrobium strain, while

Candidatus Nanohalococcus occultus were grown in a xylan-degrading trinary culture with

Haloferax lucentense and

Halorhabdus sp. (

Halobacteriota). These data indicate that the ectosymbiotic nanohaloarchaea found in such overwhelming abundance in the HKsf ecosystem are likely an active ecophysiological component of extreme halophilic communities that can degrade polysaccharides in hypersaline environments.

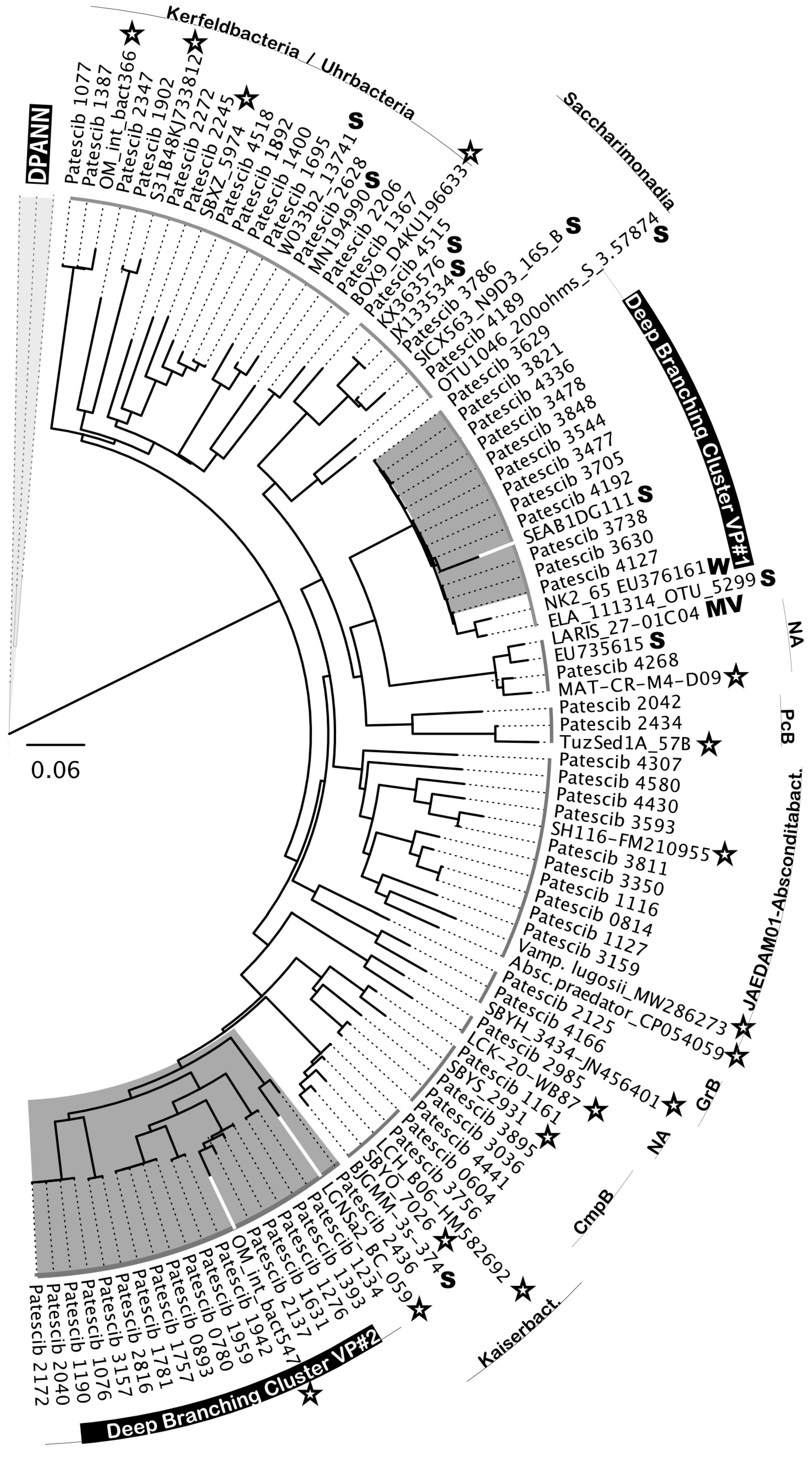

Another notable feature of the Hon Khoi saltwork ecosystem was the presence, sometimes even in significant numbers (representing 12.37% of the bacterial community in the VS7 brine), of organisms belonging to the superphylum

Patescibacteria, also called Candidate Phyla Radiation (CPR) (

Figure 10). The phylogenetic affiliation of 64 related ASVs showed a distribution in at least 11 different classes or clades of

Patescibacteria (

Figure 10). Among all 5,687 CPR-related reads retrieved, nearly two-thirds were from the less saline VS7 brine (66.7%). Their presence gradually decreased with increasing salinity, from 10.6% in the VS5 brine to 4.6% in the VS4 brine (204 g/L and 425 g/L, respectively). None of CPR-related sequences were recovered from either the Hai Ly brines or the HKsf and VCR halite samples. Interestingly, only CPR members distantly related to the cluster of

Candidatus Uhr- and Kerfeldbacteria were detected in a single Italian halite sample, SSR (8.7% of all CPR-related sequences). In-depth phylogenetic analysis revealed no clear grouping with the CPR riboclones from the NCBI database based on either the isolation source, ecosystem type/trophic state or the presence/absence of oxygen. Many of the related NCBI sequences were from very different ecosystems, from soil, marine sediments, mud volcano, fresh water lakes and hypersaline ecosystems (

Figure 10).

Similar to

Nanohaloarchaeota, two deeply branched clusters of CPR bacteria were found to be highly specific to Hon Khoi saltwork fields ecosystem. The first cluster, DBCVP#1, was detected only in VS2 and VS7 brine samples. It consists of 11 distinct ASVs and, together with 5 uncultured riboclones (NK2_65, ELA_111314_OTU_5299, SEAB1DG111, SEAB1BH081 and SEAB1BC021) recovered from wetland solis and fresh water lakes, was distantly related to

Candidatus Pacebacteria (currently the class

Microgenomatia) with no other relatives in the NCBI data base with over 91% identity. Much more intriguing was the discovery of a second, class-level cluster, DBCVP#2, found only in the VS1, VS4 and VS7 brines and grouping 17 individual ASVs, unifying 2,473 sequences taxonomically assigned to

Patescibacteria. Members of this cluster accounted for 100%, 17.1% and 62.8% in brines VS1, VS4 and VS7, respectively. Cluster DBCVP#2 appeared to be halophilic, as all members were very distantly related (90.2%-94.6% identity) only to two bacterial riboclones, OM_int_bact547 and LGNSa2_BC_059, both retrieved from hypersaline ecosystems [

82,

83]. We could not find any other relatives in the NCBI data base with the sequence identities greater than 85%.

Because most

Patescibacteria remain uncultured, it is difficult to make any assumptions about their specific hosts in Hon Khoi saltwork fields ecosystem. However, some halophilic representatives of the class

Candidatus Gracilibacteria have been maintained in stable binary cultures with gammaproteobacterial hosts [

34], abundant in HKsf brines. Thus, it is likely that

Patescibacteria are important components of the HKsf microbiome and may harbor unique metabolic traits to thrive under hypersaline conditions. This finding highlights the complexity of food webs in Hon Khoi saltwork fields ecosystem, with symbiotic and predatory nutritional strategies existing there.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we describe the first detailed data on halophilic prokaryotic communities from different crystallizer ponds and halite samples of the Hon Khoi and Hai Lý saltwork fields (Vietnam), as well as halite samples collected from several artisanal solar saltworks in western Sicily (Italy). Prokaryotic diversity (archaea and bacteria) of the sampling sites was determined using 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing approach (Illumina chemistry) during the summer season, with high radiation, scorching temperatures and high desiccation rates. Due to specificity of salt harvesting processes, the crystallizer ponds had different salinities in range of 155-315 g/kg, pH values, temperatures and other environmental characteristics, which is reflected in strong differences in the microbial community composition between samples. However, a general, well-studied trend of decreasing bacterial diversity with increasing salinity was observed in the saltiest pits and halite samples. This was not the case for the extremely halophilic bacterial genus Salinibacter which consistently appeared as the main bacterial taxon in all analyzed samples, except for the less saline HKsf brines VS2, VS5 and VS7.

Among Archaea, the extremely halophilic phyla Halobacterota and Nanohaloarchaota appeared as the dominant population in all analyzed samples (brines, microbial mats, and salts), accounting for up to 99% of the total archaeal communities in brine HL345. Both these phyla are characterized by their interspecies interactions that can be classified as classical types of either mutualistic symbiosis or pure commensalism. Similar to Bacteria, no clear and defined population structure at the genus level was detected in the haloarchaeal community in all brine and halite samples. They were all quite diverse, even in brine pools located in close proximity. However, we did find some interesting trends. For example, the genus Halorubrum was omnipresent as one of the dominant taxa in 17 of all 19 analyzed brine and salt samples, reaching its highest relative abundances in freshly collected halite from both Vietnam and Italy. It is also noteworthy that the highest relative abundance of the genus Halobaculum was found only in the Hon Khoi salt fields samples, which can be considered a biogeographical connotation.

In the same vein of the likely existence of other biogeographic patterns, we examined the diversity of the ultra-small prokaryotes belonging to Patescibacteria (CPR) and DPANN Archaea. Surprisingly, we found at least five deeply branched clades, both bacterial and archaeal, that appeared to be highly specific to Hon Khoi saltwork fields ecosystem. Among the two CPR clusters, DBCVP#2, consisting of 17 distinct ASVs, together with only two similar sequences (90.2%-94.6% identity) known, retrieved from hypersaline ecosystems of Oman and Mexico, appears represent a novel halophilic class-level taxon within the phylum Patescibacteria. The same is true for most of ASVs associated with HKsf Woesearchaeales (phylum Nanoarchaeota), as they formed a deeply branched halophilic cluster DBCVW#1, along with a single similar riboclone recovered from the same hypersaline ecosystem of Mexico as the CPR-associated clone mentioned above. Since most of ultra-small prokaryotes remain uncultured, it is difficult to make assumptions about their specific hosts, their roles and functional activities in Hon Khoi saltwork fields ecosystem. Only two nanohaloarchaeal clades, DBCVN#1 and DBCVN#2, were found be distantly related to the cultivated Candidatus Nanohalobium and Candidatus Nanohalococcus, both of which are members of polysaccharide-degrading consortia. This finding may suggest that ectosymbiotic ultra-small prokaryotes or at least nanohaloarchaea are an active ecophysiological component of extreme halophilic hydrolytic communities in the HKsf ecosystem. Further studies are needed to characterize these uncultivated taxa, as well as attempts to isolate and cultivate them, which will allow us to elucidate their ecological role in these hypersaline habitats and explore their biotechnological and biomedical potential. Finally, this study helps fill the gaps in our understanding of prokaryotic diversity and resources of Vietnamese saltworks.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Bacterial genera with ambiguous affiliations and relative abundances <1.0 %; Table S2: Archaeal genera with ambiguous affiliations and relative abundances <1.0 %; Table S3: Bacterial genera with relative abundances >1.0 %; Table S4: Archaeal genera with relative abundances >1.0 %.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.L.C., H.H.N.K, N.K.B. and M.M.Y.; methodology, V.L.C., L.M., A.M., P.D.T., C.T.T.H. and M.M.Y.; software, G.L.S., F.S. and F.C.; validation, V.L.C., N.K.B. and M.M.Y.; formal analysis, V.L.C., G.L.S., F.S. and F.C.; investigation, V.L.C., H.H.N.K, N.K.B. and M.M.Y.; resources, V.L.C., H.H.N.K, N.K.B. and M.M.Y X.X.; data curation, G.L.S., F.S. and F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, V.L.C., G.L.S. and M.M.Y.; writing—review and editing, V.L.C., G.L.S., H.H.N.K, N.K.B. and M.M.Y X.X.; visualization, G.L.S. and M.M.Y.; supervision, V.L.C. and M.M.Y.; project administration, V.L.C., H.H.N.K, N.K.B. and M.M.Y.; funding acquisition, V.L.C., H.H.N.K, N.K.B. and M.M.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Council of Research (CNR) and Vietnamese Academy of Science and Technology (VAST) in the frame of two projects of bilateral collaborations, EXPLO-Halo and HaloPharm, under grant number QTIT01.01/20-21 and QTIT01.01/23-24, respectively.

Data Availability Statement

The sequencing dataset obtained in this study is freely available through the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA)/NCBI under the accession number PRJNA1142429, BioSample accessions SAMN42940649-67. All 16S rDNA sequences of

Nanohaloarchaeota, obtained in various polysaccharide-degrading enrichments were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers PQ139286-93 (

https://submit.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/subs/?search=SUB14640106). All the R scripts used to analyze the sequences and reproduce the pictures are available on:

https://github.com/GiISP/Vietnam. All other data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank to Vietnamese and Italian authorities, for kind permission and assistance with sampling in the solar salterns of Vietnam and Trapani (Sicily, Italy) and especially to Adele Occhipinti to get permission for sampling in the private solar salters of Motya (Sicily, Italy).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wei, Y.-L.; Long, Z.-J.; Ren, M.-X. Microbial community and functional prediction during the processing of salt production in a 1000-year-old marine solar saltern of South China. Sci Total Environ. 2022, 819, 152014–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javor, B.J. Industrial microbiology of solar salt production. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002, 28, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Medeiros Rocha, R.; Costa, D.F.; Lucena-Filho, M.A.; Bezerra, R.M.; Medeiros, D.H.; Azevedo-Silva, A.M.; Araujo, C.N.; Xavier-Filho, L. Brazilian solar saltworks - ancient uses and future possibilities. Aquat. Biosyst. 2012, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani, K.; Salgaonkar, B.B.; Braganca, J.M. Culturable halophilic archaea at the initial and crystallization stages of salt production in a natural solar saltern of Goa, India. Aquat. Biosyst, 2012, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conde-Martinez, N.; Acosta-Gonzalez, A.; Diaz, L.E.; Tello, E. Use of a mixed culture strategy to isolate halophilic bacteria with antibacterial and cytotoxic activity from the Manaure solar saltern in Colombia. BMC Microbiol. 2017, 17, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoni, C.; Volpicella, M.; Fosso, B.; Manzari, C.; Piancone, E.; Dileo, M.C.G.; Arcadi, E.; Yakimov, M.; Pesole, G.; Ceci, L.R. A differential metabarcoding approach to describe taxonomy profiles of bacteria and archaea in the saltern of Margherita di Savoia (Italy). Microorganisms, 2020, 8, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margesin, R.; Zacke, G.; Schinner, F. Characterization of heterotrophic microorganisms in alpine glacier cryoconite. Arctic Antarct. Alp. Res. 2002, 34, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbrel, J.A.; Ballor, N.; Wu, Y.-W.; David, M.M.; Hazen, T.C.; Simmons, B.A.; Singer, S.W.; Jansson, J.K. Microbial Community Structure and Functional Potential Along a Hypersaline Gradient. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oren, A. Diversity of halophilic microorganisms: Environments, phylogeny, physiology, and applications. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002, 28, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baati, H.; Guermazi, S.; Amdouni, R.; Gharsallah, N.; Sghir, A.; Ammar, E. Prokaryotic diversity of a Tunisian multipond solar saltern. Extremophiles, 2008, 12, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigui, H.; Masmoudi, S.; Brochier-Armanet, C.; Barani, A.; Grégori, G.; Denis, M.; Dukan, S.; Maalej, S. Characterization of heterotrophic prokaryote subgroups in the Sfax coastal solar salterns by combining flow cytometry cell sorting and phylogenetic analysis. Extremophiles, 2011, 15, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, K. B.; Canfield, D. E.; Teske, A. P.; Oren, A. Community composition of a hypersaline endoevaporitic microbial mat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 11, 7352–7365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manikandan, M.; Kannan, V.; Pašic ́, L. Diversity of microorganisms in solar salterns of Tamil Nadu, India. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 25, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selivanova, E.A.; Poshvina, D.V.; Khlopko, Y.A.; Gogoleva, N.E.; Plotnikov, A.O. Diversity of prokaryotes in planktonic communities of saline Sol-Iletsk lakes (Orenburg Oblast, Russia). Microbiology, 2018, 87, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpolat, C.; Fernández, A.B.; Caglayan, P.; Calli, B.; Birbir, M.; Ventosa, A. Prokaryotic communities in the Thalassohaline Tuz Lake, deep zone, and Kayacik, Kaldirim and Yavsan Salterns (Turkey) assessed by 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing. Microorganisms, 2021, 9, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, D.G.; Camakaris, H.M.; Janssen, P.H.; Dyall-Smith, M.L. Combined use of cultivation-dependent and cultivation-independent methods indicates that members of most haloarchaeal groups in an Australian crystallizer pond are cultivable. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 5258–5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, J.G.; Carlin, M.; Gutierrez, A.; Nguyen, V.; McLain, N. Patterns of microbial diversity along a salinity gradient in the Guerrero Negro solar saltern, Baja CA Sur, Mexico. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, J.; Rossello-Mora, R.; Rodriguez-Valera, F.; Amann, R. Extremely Halophilic Bacteria in Crystallizer Ponds from Solar Salterns. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 3052–3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlloch, S.; López-López, A.; Casamayor, E.O.; Øvreås, L.; Goddard, V.; Daae, F.L.; Smerdon, G.; Massana, R.; Joint, I.; Thingstad, F.; et al. Prokaryotic genetic diversity throughout the salinity gradient of a coastal solar saltern. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 4, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pašić, L.; Ulrih, N.P.; Crnigoj, M.; Grabnar, M.; Velikonja, B.H. Haloarchaeal communities in the crystallizers of two Adriatic solar salterns. Can. J. Microbiol. 2007, 53, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventosa, A.; Fernández, A.B.; León, M.J.; Sánchez-Porro, C.; Rodriguez- Valera, F.J.E. The Santa Pola saltern as a model for studying the microbiota of hypersaline environments. Extremophiles, 2014, 18, 811–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kambourova, M.; Tomova, I.; Boyadzhieva, I.; Radchenkova, N.; Vasileva- Tonkova, E. Unusually high archaeal diversity in a crystallizer pond, Pomorie salterns, Bulgaria, revealed by phylogenetic analysis. Archaea 2016, 16, 7459679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasol, J.M.; Casamayor, E.O.; Joint, I.; Garde, K.; Gustavson, K.; Benlloch, S.; Díez, B.; Schauer, M.; Massana, R.; Pedrós-Alió, C. Control of heterotrophic prokaryotic abundance and growth rate in hypersaline planktonic environments. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 2004, 34, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghai, R.; Pašić, L.; Fernández, A.B.; Martin-Cuadrado, A.B.; Mizuno, C.M.; McMahon, K.D.; Papke, R.T.; Stepanauskas, R.; Rodriguez-Brito, B.; Rohwer, F.; et al. New abundant microbial groups in aquatic hypersaline environments. Sci. Rep. 2011, 1, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani, K.; Taib, N.; Hugoni, M.; Bronner, G.; Bragança, J.M.; Debroas, D. Transient dynamics of archaea and bacteria in sediments and brine across a salinity gradient in a solar saltern of Goa, India. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, C.F.; Grant, W.D. Survival of halobacteria within fluid inclusions in salt crystals. Microbiology 1988, 134, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huby, T.J.C.; Clark, D.R.; McKew, B.A.; McGenity, T.J. Extremely halophilic archaeal communities are resilient to short-term entombment in halite. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 3370–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown,C.T.; Hug, L.A.; Thomas, B.C.; Sharon, I.; Castelle, C.J. Singh, A.; Wilkins, M.J.; Wrighton, K.C.; Williams, K.H.; Banfield, J.F. Unusual biology across a group comprising more than 15% of domain Bacteria. Nature 2015, 523, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelle, C.J.; Banfield, J.F. Major new microbial groups expand diversity and alter our understanding of the tree of life. Cell 2018, 172, 1181–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Ning, D.; He, Z.; Zhang, P.; Spencer, S.J.; Gao, S.; Shi, W.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; et al. Small and mighty: adaptation of superphylum Patescibacteria to groundwater environment drives their genome simplicity. Microbiome 2020, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hug, L.A.; Baker, B.J.; Anantharaman, K.; Brown, C.T.; Probst, A.J.; Castelle, C.J.; Butterfield, C.N.; Hernsdorf, A.W.; Amano, Y.; Ise, K.; et al. A new view of the tree of life. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Cono, V.; Messina, E.; Rohde, M.; Arcadi, E.; Ciordia, S.; Crisafi, F.; Denaro, R.; Ferrer, M.; Giuliano, L.; Golyshin, P.N.; et al. Symbiosis between nanohaloarchaeon and haloarchaeon is based on utilization of different polysaccharides. PNAS, 2020, 117, 20223–20234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Cono, V.; Messina, E.; Reva, O.; Smedile, F.; La Spada, G.; Crisafi, F.; Marturano, L.; Miguez, N.; Ferrer, M.; Selivanova, E.A.; et al. Nanohaloarchaea as beneficiaries of xylan degradation by haloarchaea. Microb. Biotech. 2023, 16, 1803–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakimov, M.M.; Merkel, A.Y.; Gaisin, V.A.; Pilhofer, M.; Messina, E.; Hallsworth, J.E.; Klyukina, A.A; Tikhonova, E.N.; Gorlenko, V.M. Cultivation of a vampire: ‘Candidatus Absconditicoccus praedator’. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 24, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Molenda, O.; Brown, C.T.; Toth, C.R.; Guo, S.; Luo, F.; Howe, J.; Nesbo, C.L.; He, C.; Montabana, E.A.; et al. “Candidatus Nealsonbacteria” are likely biomass recycling ectosymbionts of methanogenic archaea in a stable benzene-degrading enrichment culture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2023, 89, e00025–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasingarao, P.; Podell, S.; Ugalde, J.A.; Brochier-Armanet, C.; Emerson, J.B.; Brocks, J.J.; Heidelberg, K.B.; Banfield, J.F.; Allen, E.E. De novo metagenomic assembly reveals abundant novel major lineage of Archaea in hypersaline microbial communities. ISME J. 2012, 6, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podell, S.; Emerson, J.B.; Jones, C.M.; Ugalde, J.A.; Welch, S.; Heidelberg, K.B.; Banfield, J.F.; Allen, E.E. Seasonal fluctuations in ionic concentrations drive microbial succession in a hypersaline lake community. ISME J. 2014, 8, 979–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornariz, M.; Martínez-García, M.; Santos, F.; Rodriguez, F.; Capella-Gutiérrez, S.; Gabaldón, T.; Rosselló-Móra, R.; Meseguer, I.; Antón, J. From community approaches to single-cell genomics: the discovery of ubiquitous hyperhalophilic Bacteroidetes generalists. ISME J 2015, 9, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crits-Christoph, A.; Gelsinger, D.R.; Ma, B.; Wierzchos, J.; Ravel, J.; Davila, A.; Casero, M.C.; DiRuggiero, J. Functional interactions of archaea, bacteria and viruses in a hypersaline endolithic community. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 2064–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Meglio, L.; Santos, F.; Gomariz, M.; Almansa, C.; López, C.; Antón, J.; Nercessian, D. Seasonal dynamics of extremely halophilic microbial communities in three Argentinian salterns. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, fiw184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Ruiz, M. D.R. , Cifuentes, A., Font-Verdera, F., Pérez-Fernández, C., Farias, M.E., González, B., Orfila, A.; Rosselló-Móra, R. Biogeographical patterns of bacterial and archaeal communities from distant hypersaline environments. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 41, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavourakis, C.D.; Andrei, A.-S.; Mehrshad, M.; Ghai, R.; Sorokin, D.Y.; Muyzer, G. A metagenomics roadmap to the uncultured genome diversity in hypersaline soda lake sediments. Microbiome. 2018, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Cono, V.; Bortoluzzi, G.; Messina, E.; La Spada, G.; Smedile, F.; Giuliano, L.; Borghini, M.; Stumpp, C.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Harir, M.; et al. The discovery of Lake Hephaestus, the youngest athalassohaline deep-sea formation on Earth. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Neri, U.; Gosselin, S.; Louyakis, A.S., Papke, R.T.; Gophna, U.; Gogartenet, J.P. The evolutionary origins of extreme halophilic archaeal lineages. Genome Biol. Evol. 2021, 13, evab166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadros-Rodrıguez L., Bagur-González M.G., Sanchez-Viñas M., Gonzalez-Casado A., Gomez-Saez A.M. , Bagur-González M.G., Sanchez-Viñas M., Gonzalez-Casado A., Gomez-Saez A.M. Principles of analytical calibration/quantification for the separation sciences. J. Chromat. 2007, A 1158, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienitz, O. , Rohker K., Schiel D., Han J., Oeter D. New equation for the evaluation of standard addition experiments applied to ion chromatography. Microchim. Acta, 2006, 154, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurt, R.A.; Qiu, X.; Wu, L.; Roh, Y.; Palumbo, A.V.; Tiedje, J.M.; Zhou, J. Simultaneous recovery of RNA and DNA from soils and sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 4495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glöckner, F.O. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 2013. 41, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, J.; Lauber, C.; Walters, W.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Huntley, J.; Fierer, N.; Owens, S.M.; Betley, J.; Fraser, L.; Bauer, M.; et al. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J 2012, 6, 1621–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Open J. Stat. 13, (2023).

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisafi, F.; Smedile, F.; Yakimov, M.M.; Aulenta, F.; Fazi, S.; La Cono, V.; Martinelli, A.; Di Lisio, V.; Denaro, R. Bacterial biofilms on medical masks disposed in the marine environment: a hotspot of biological and functional diversity. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 837, 155731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R Package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S.A.; Lahti, L. Microbiome data science. J. Biosci. 2019, 44, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; R Package version 2.3-2. Vegan: community ecology package. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=vegan (accessed on 19 June 2020).

- Liu, C.; Cui, Y.; Li, X.; Yao, M. microeco: an R package for data mining in microbial community ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lange, G.; Middelburg, J.; van der Weijden, C.; Catalano, G.; Luther, G.; Hydes, D.; Woittiez, J.R.W.; Klinkhammer, G.P. Composition of anoxic hypersaline brines in the Tyro and Bannock basins, eastern Mediterranean. Mar. Chem. 1990, 31, 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.B.; Ghai, R.; Martin-Cuadrado, A.B.; Sanchez-Porro, C.; Rodriguez-Valera, F.; Ventosa, A. Prokaryotic taxonomic and metabolic diversity of an intermediate salinity hypersaline habitat assessed by metagenomics. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 88, 623–635. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A. B.; Vera-Gargallo, B.; Sánchez-Porro, C.; Ghai, R.; Papke, R.T.; Rodriguez-Valera, F., Ventosa, A. Comparison of prokaryotic community structure from Mediterranean and Atlantic saltern concentrator ponds by a metagenomic approach. Front. Microbiol. 2014b, 5, 196. [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; D’Agostino McGowan, L.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. (2019). Welcome to the tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schliep, K. phangorn: phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics, 2011, 27, 592–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galili, T. dendextend: an R package for visualizing, adjusting, and comparing trees of hierarchical clustering. Bioinformatics, 2015, 31, 3718–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, A.; Ripley, B.D. ggdendro: Create Dendrograms and Tree Diagrams Using 'ggplot2'. R package version 0.2.0, 2024, https://andrie.github.io/ggdendro/.

- Xiao, N. ggsci: Scientific Journal and Sci-Fi Themed Color Palettes for 'ggplot2'. R package version 3.2.0, 2024, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggsci/.

- Wilke, C. cowplot: Streamlined Plot Theme and Plot Annotations for 'ggplot2'. R package version 1.1.3, 2024, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cowplot.

- Oren, A. Novel insights into the diversity of halophilic microorganisms and their functioning in hypersaline ecosystems. npj Biodivers, 2024, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takai, K.; Moser, D.P.; DeFlaun, M.; Onstott, T.C.; Fredrickson, J.K. Archaeal Diversity in Waters from Deep South African Gold Mines. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollister, E.; Engledow, A.; Hammett, A.; Provin,T.L.; Wilkinson, H.H; Gentry T.J. Shifts in microbial community structure along an ecological gradient of hypersaline soils and sediments. ISME J 2010, 4, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baricz, A.; Chiriac, C.M.; Andrei, A.-Ș.; Bulzu P.-A.; Levei; E.A.; Cadar, O.; Battes, K.P.; Cîmpean, M.; Șenilă, M.; Cristea, A. Spatio-temporal insights into microbiology of the freshwater-to-hypersaline, oxic-hypoxic-euxinic waters of Ursu Lake. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 3523–3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriet, O.; Fourmentin, J.; Delincé, B.; Mahillon, J. Exploring the diversity of extremely halophilic archaea in food-grade salts. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 191, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, H.-W.; Song, H.S.; Song, U.; Yim, K.J.; Roh, S.W.; Park, S.-J. Halolamina sediminis sp. nov., an extremely halophilic archaeon isolated from solar salt. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 2479–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.R.; Mathieu, M.; Mourot, L.; Dufossé, L.; Underwood, G.J.C.; Dumbrell, A.J.; McGenity, T.J. Biogeography at the limits of life: do extremophilic microbial communities show biogeographical regionalization? Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 2017, 26, 1435–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibtan, A.; Park, K.; Woo, M.; Shin, J.-K.; Lee, D.-W.; Sohn, J.H.; Song, M.; Roh, S.W.; Lee, S.-J.; Lee, H.-S. Diversity of extremely halophilic archaeal and bacterial communities from commercial salts. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGenity, T.J.; Gemmell, R.T.; Grant, W.D.; Stan- Lotter, H. Origins of halophilic microorganisms in ancient salt deposits. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 2, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mormile, M.R.; Biesen, M.A.; Gutierrez, M.C.; Ventosa, A.; Pavlovich, J.B.; Onstott, T.C.; Fredrickson, J.K. Isolation of Halobacterium salinarum retrieved directly from halite brine inclusions. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 5, 1094–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramain, A.; Díaz, G.C.; Demergasso, C.; Lowenstein, T.K.; McGenity, T.J. Archaeal diversity along a sub- terranean salt core from the Salar Grande (Chile). Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 2105–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, S.T.; Ravantti, J.J.; Oksanen, H.M.; Bamford, D.H. Buried alive: microbes from ancient halite. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyh, N.A.; Merkel, A.Y.; Kondrasheva, K.V.; Alimov, J.E.; Klyukina, A.A.; Bonch-Osmolovskaya, E.A.; Slobodkin, A.I.; Davranov, K.D. At the shores of a vanishing sea: microbial communities of Aral and southern Aral Sea region. Microbiology, 2024, 93, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahl, J.W.; Pace, N.R.; Spear, J.R. Comparative molecular analysis of endoevaporitic microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 6444–6446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reva, O.N.; La Cono, V.; Crisafi, F.; Smedile, F.; Mudaliyar, M.; Ghosal, D.; Giuliano, L.; Krupovic, M.; Yakimov, M.M. Interplay of intracellular and trans-cellular DNA methylation in natural archaeal consortia. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2024, 16, e13258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Garcia, M.; Santos, F.; Moreno-Paz, M.; Parro, V.; Anton, J. Unveiling viral-host interactions within the ’microbial dark matter’. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, K.; Green, S. J.; Jahnke, L.; Kubo, M.; Parenteau, M. N.; Vogel, M.; Des Marais, D. Phylogenetic analysis of microbial communities from gypsum precipitating environments. Astrobiology, 2008, 8, 383. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, J. C.; Abed, R.M.; Albach, D.C.; Palinska, K.A. Bacterial and archaeal diversity in hypersaline cyanobacterial mats along a transect in the intertidal flats of the Sultanate of Oman. Microb. Ecol. 2018, 75, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).