Submitted:

27 August 2024

Posted:

29 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

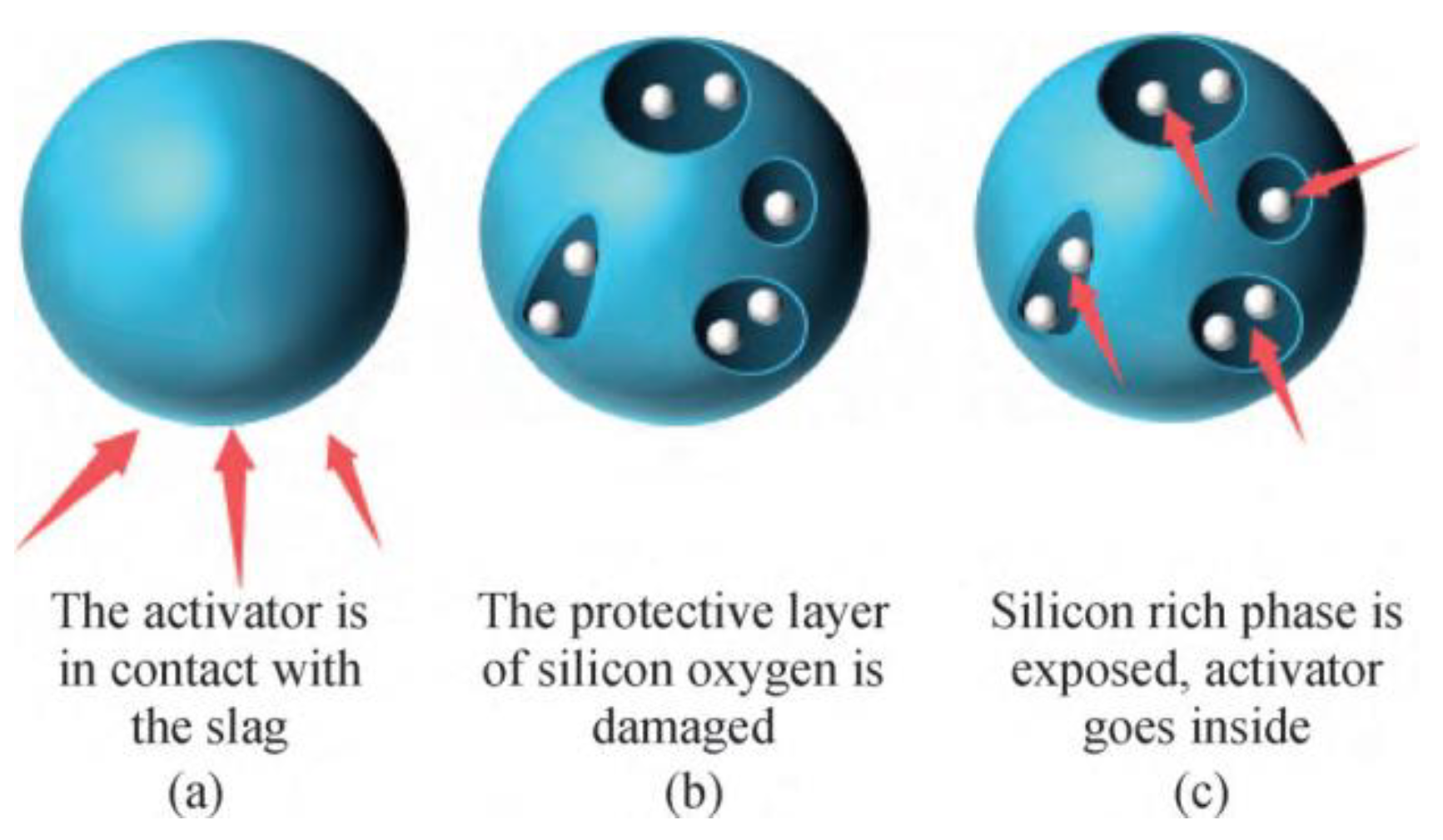

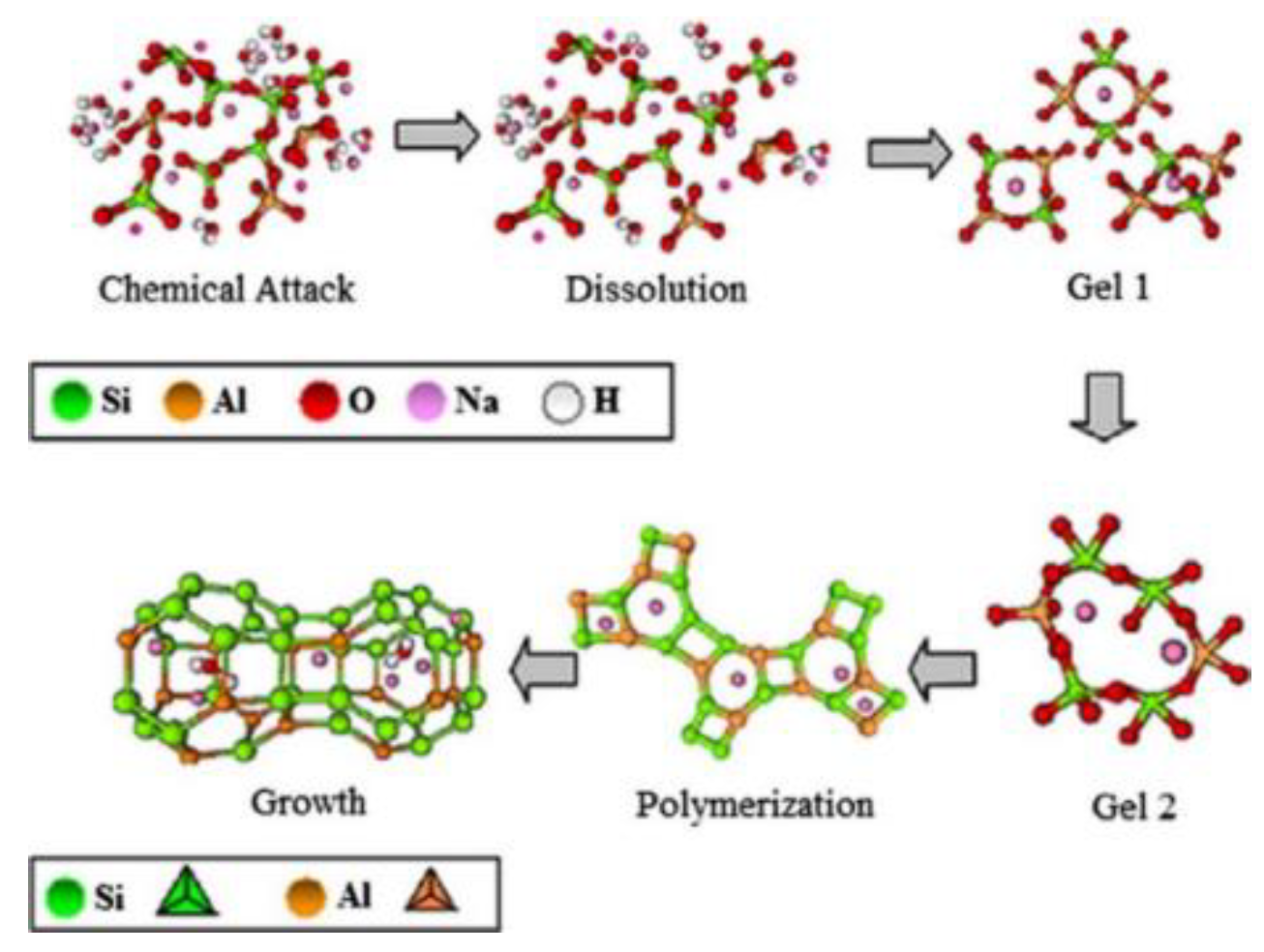

2. Hydration Mechanism of Alkali-Excited Slag Cement

3. Acid Corrosion Resistance of Alkali Excited Slag Cement Concrete

3.1. Mechanism of Acid Corrosion

3.2. Effect of Acid Corrosion on Concrete Properties

4. Sulfate Corrosion Resistance of Alkali Excited Slag Cement Concrete

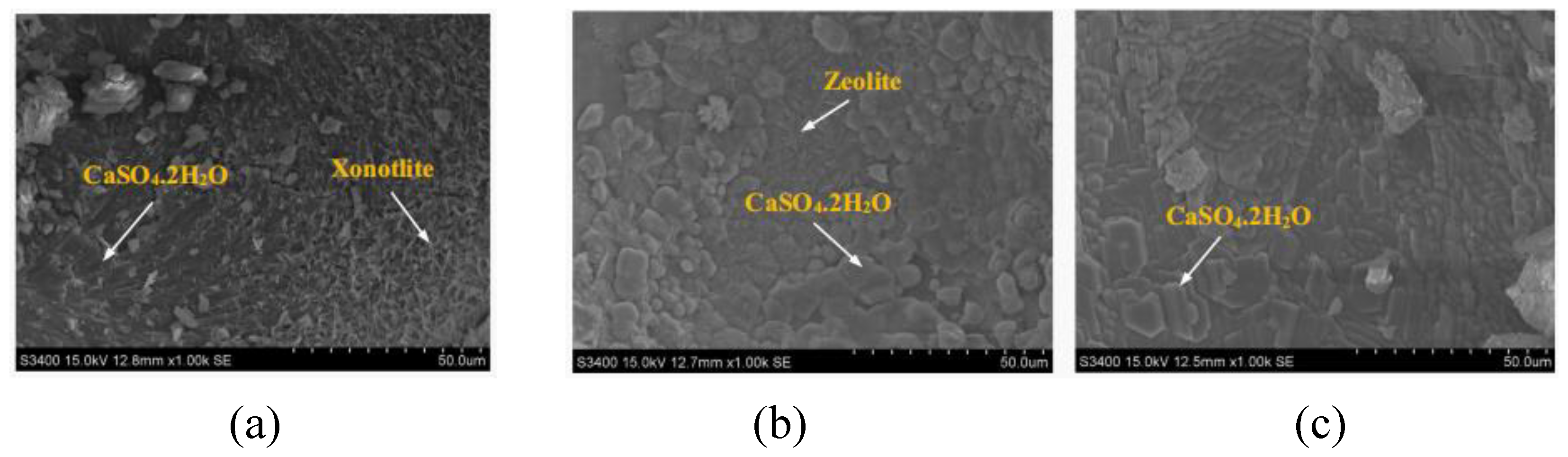

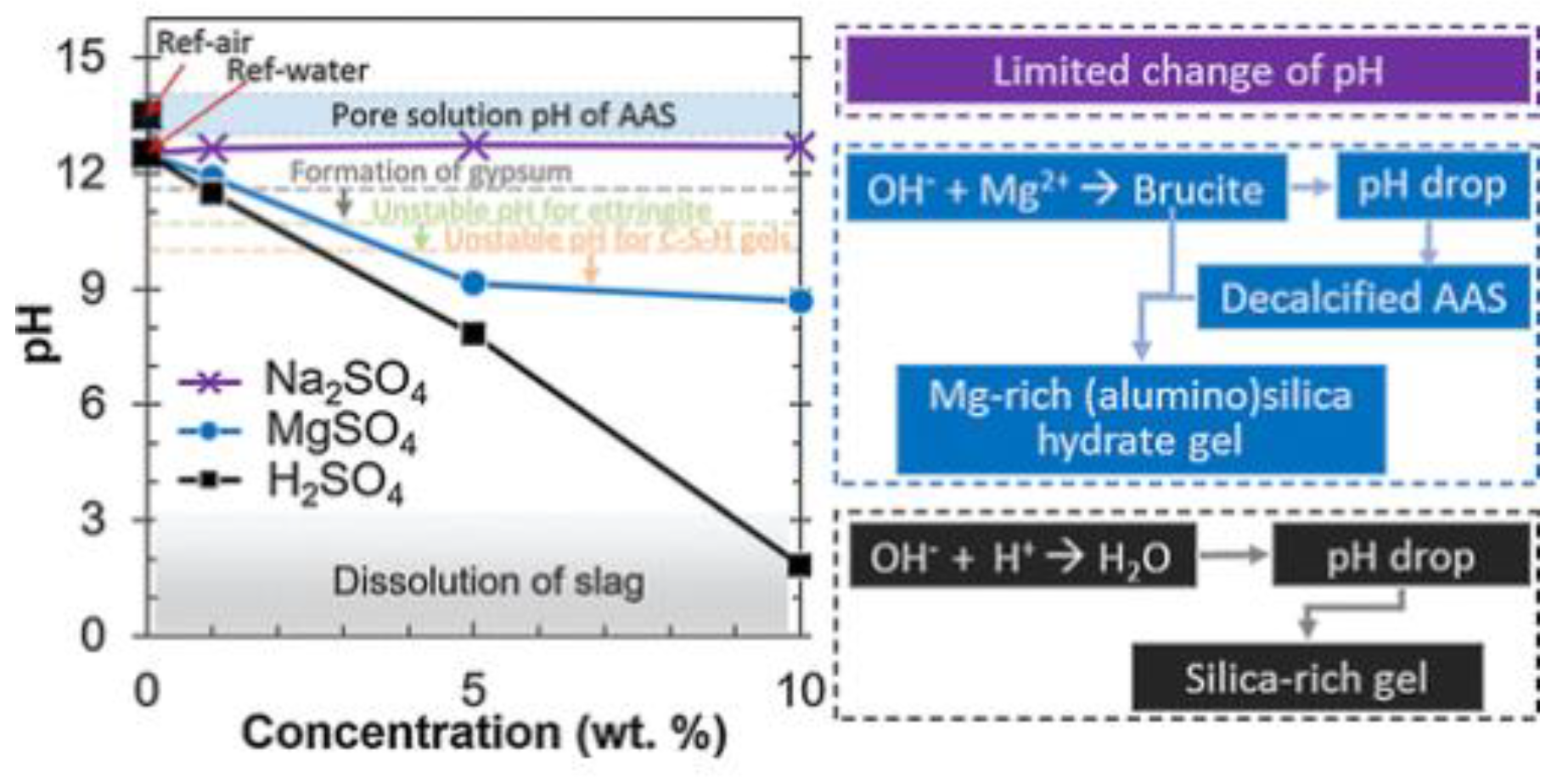

4.1. Destruction Mechanism of Sulfate Corrosion

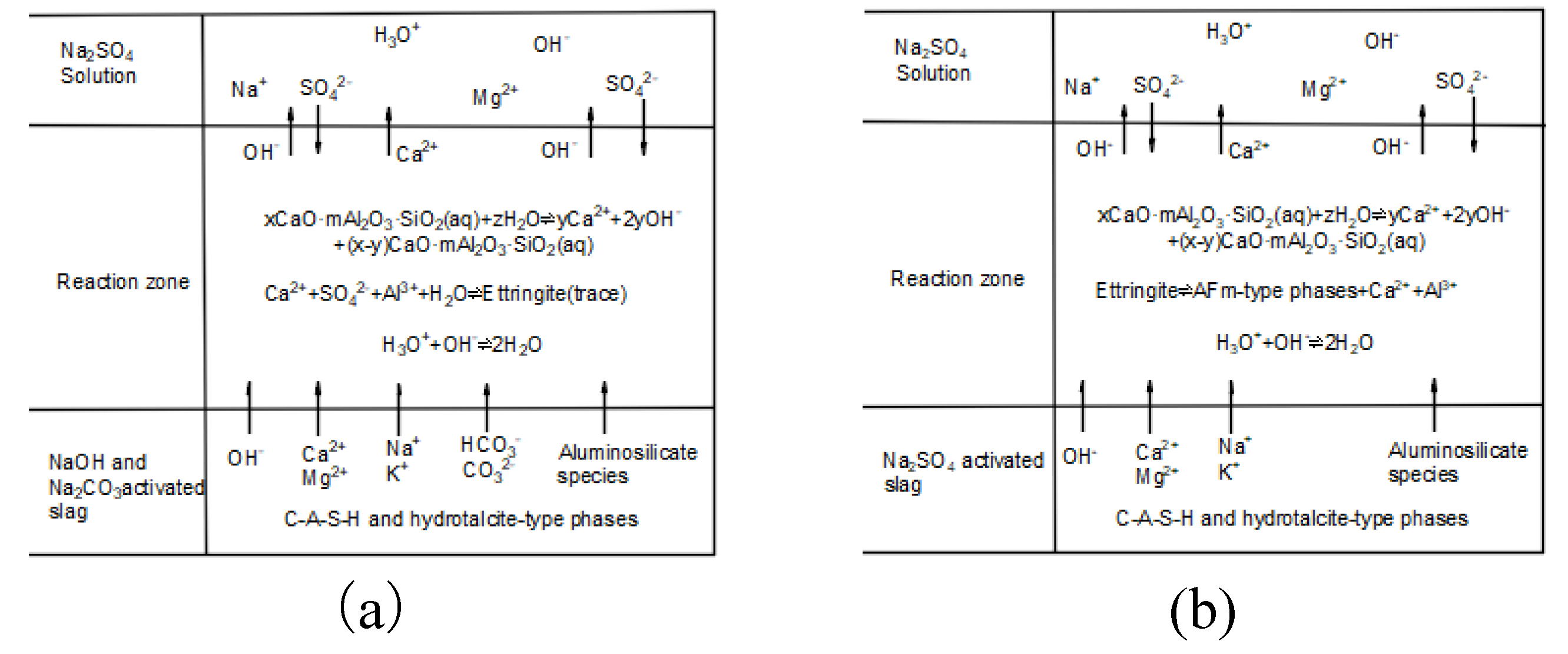

4.1.1. Sodium Sulfate Corrosion Damage Mechanism

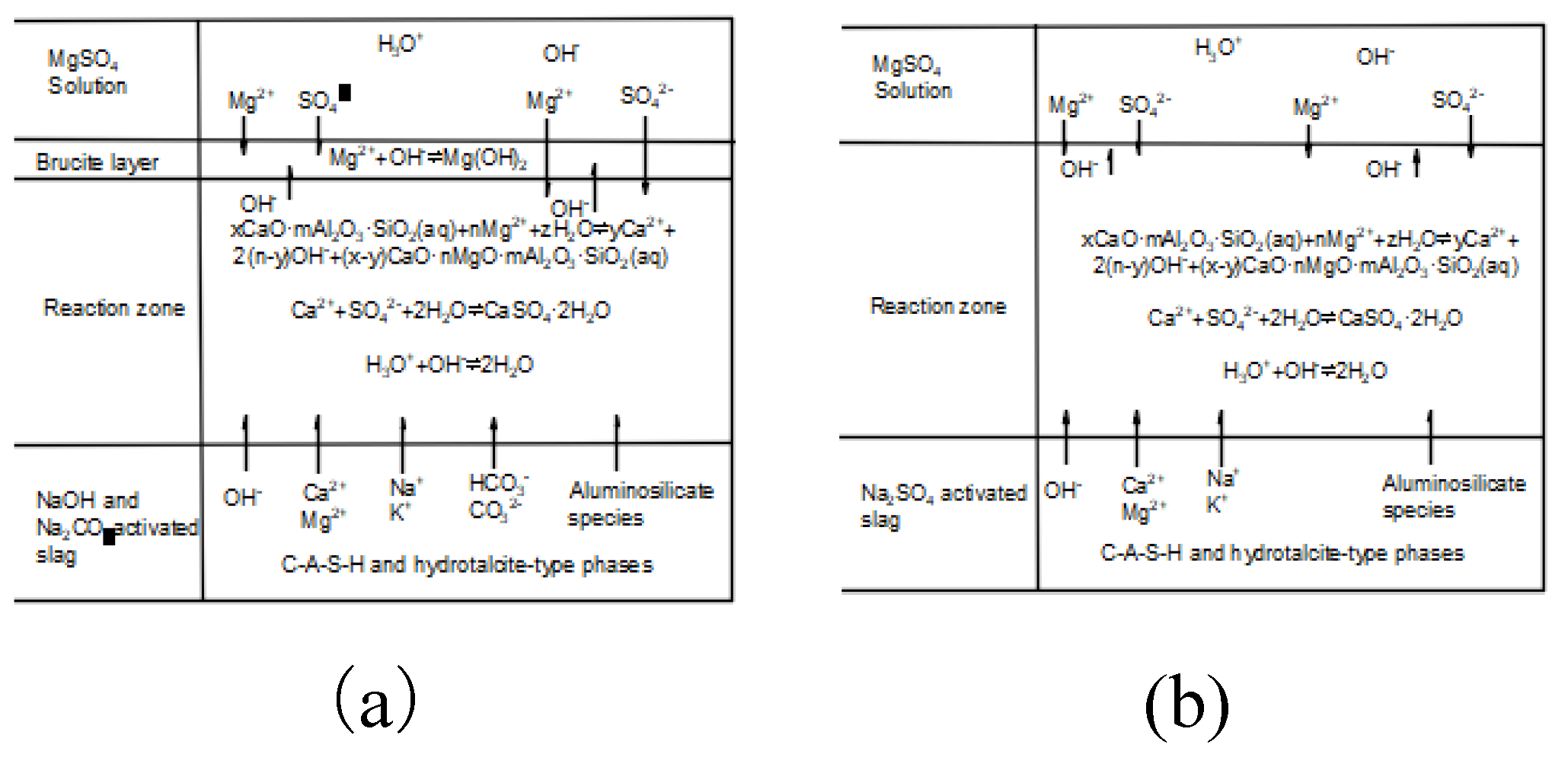

4.1.2. Magnesium Sulfate Corrosion Damage Mechanism

4.2. Effect of Sulfate on the Properties of AAS Concrete

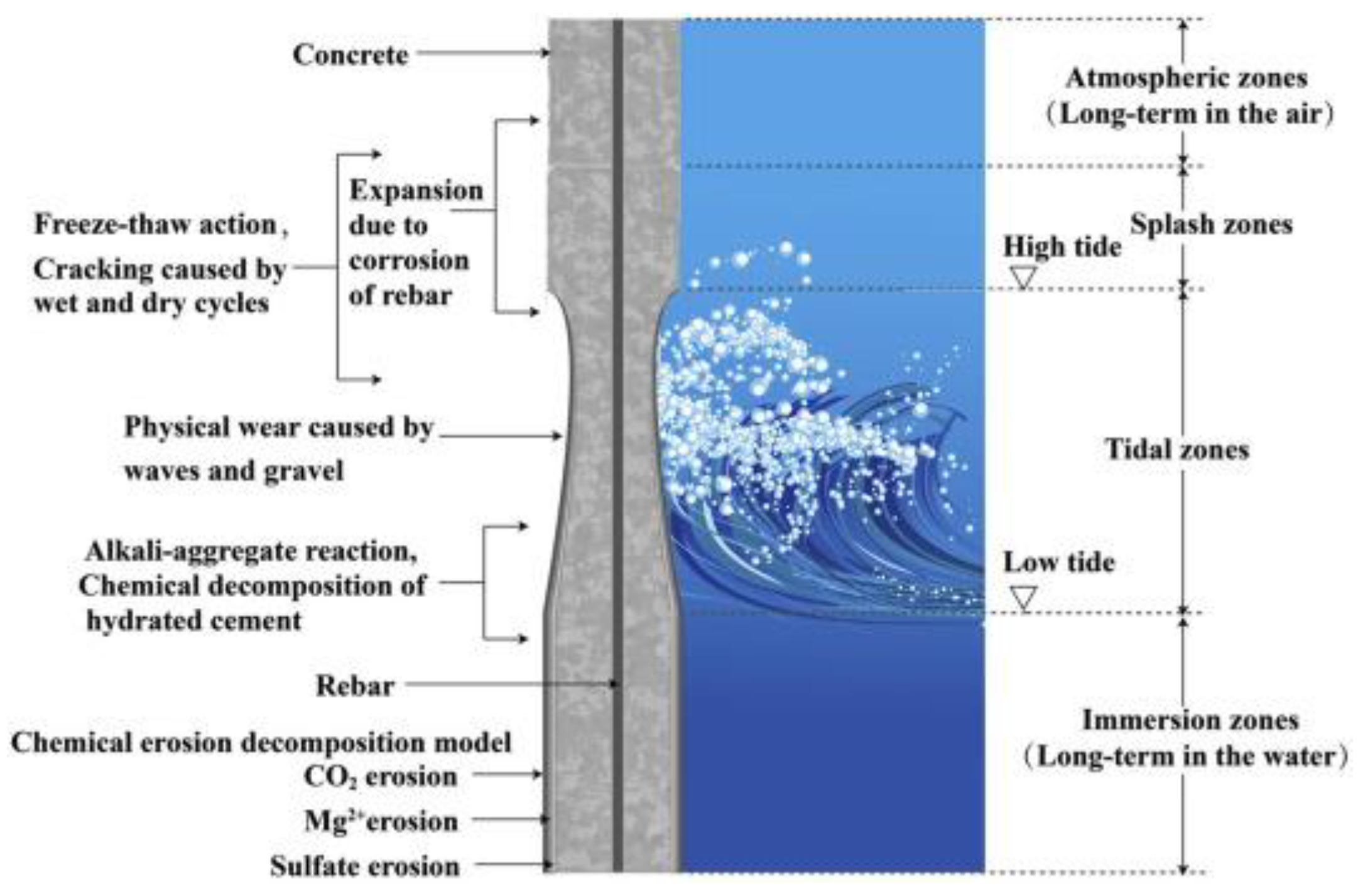

5. Alkali-Inspired Slag Cement Concrete for Seawater Corrosion Resistance

6. Conclusion and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Gartner, E. Industrially interesting approaches to “low-CO2” cements. Cement and Concrete Research 2004, 34, 1489–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Torgal F, Labrincha J A, Leonelli C, et al. Baščarevć Z. 14 - The resistance of alkali-activated cement-based binders to chemical attack [M]// Handbook of Alkali-Activated Cements, Mortars and Concretes. Woodhead Publishing, 2015: 373-396.

- Valencia-Saavedra, W.G.; Mejia, D.G.R. Resistance to Chemical Attack of Hybrid Fly Ash-Based Alkali-Activated Concretes. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostami, M.; Behfarnia, K. The effect of silica fume on durability of alkali activated slag concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2017, 134, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, S.A.; San Nicolas, R.; Provis, J.L.; et al. Natural carbonation of aged alkali-activated slag concretes. Materials and structures 2013, 47, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, H.; Mazloom, M. Opposite effects of ground granulated blast-furnace slag and silica fume on the fracture behavior of self-compacting lightweight concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2019, 222, 622–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chol, H.; Lee, J.; Lee, B.; et al. Shrinkage properties of concretes using blast furnace slag and frost-resistant accelerator. Construction and Building Materials 2019, 220, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, S.; Guo, K.; Pin, Z.; et al. Progress of hydration, mechanical and shrinkage properties of alkali-slag cement. Bulletin of the Chinese Ceramic Society 2022, 41, 162–173. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J. Research on the composition structure and performance of alkali-excited slag micro-powder cementitious materials [D]. Xi'an University of Architecture and Technology, 2008.

- Ru, Y. Physicochemical basis for the formation of alkali cementitious materials (Ⅱ). Journal of the Chinese Ceramic Society 1996, 459–465. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, G. Research on the reaction process of alkali-excited slag cementitious material and its modification [D]. Shenzhen University, 2018.

- Sheng, Z.; jun, Y.; Xiong, W.; et al. Hydration of granulated blast furnace slag in different environments: First Annual Meeting of the Cement Branch of the China Silicate Society [C], Jiaozuo, Henan, China, 2009.

- Mastali, M.; Kinnunen, P.; Dalvand, A.; et al. Drying shrinkage in alkali-activated binders – A critical review. Construction and Building Materials 2018, 190, 533–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Torgal, F. 1 - Introduction to Handbook of Alkali-activated Cements, Mortars and Concretes [M]//Pacheco-Torgal F, Labrincha J A, Leonelli C, et al. Handbook of Alkali-Activated Cements, Mortars and Concretes. Oxford: Woodhead Publishing 2015, 1-16.

- Jiang, N.; Du, Y.; Liu, K. Durability of lightweight alkali-activated ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS) stabilized clayey soils subjected to sulfate attack. Applied clay science 2018, 161, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhu, H.; Shah, K.W.; et al. Performance evaluation and microstructure characterization of seawater and coral/sea sand alkali-activated mortars. Construction & building materials 2020, 259, 120403. [Google Scholar]

- Min, M.; Ping, H.; Liang, N.; et al. Study on the effects of alkali exciter concentration and modulus on compressive properties and hydration products of alkali slag cementitious materials. Bulletin of the Chinese Ceramic Society 2018, 37, 2002–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Shi Caijun Bavel Clevenko Della Roy. Alkali-Excited Cement and Concrete [M]. Chemical Industry Press, 2008.

- Hu, X.; Shen, F.; Zheng, H.; et al. Effect of melt structure property on Al2O3 activity in CaO-SiO2-Al2O3-MgO system for blast furnace slag with different Al2O3 content. Metallurgical research & technology 2021, 118, 515. [Google Scholar]

- Adesanya, E.; Perumal, P.; Luukkonen, T.; et al. . Opportunities to improve sustainability of alkali-activated materials: A review of side-stream based activators. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 286, 125558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, L.; Yan, L. Research on acid corrosion mechanism of concrete. Science and Technology Information, 2010(35): 1085-1095.

- Ling, J.; Ping, S.; Min, P.; et al. Acid corrosion damage phenomenon of cementitious materials and measures to improve acid corrosion resistance.China Concrete, 2020(04): 44-52.

- Abdel-Gawwad, H.A.; El-Aleem, S.A. EFFECT OF REACTIVE MAGNESIUM OXIDE ON PROPERTIES OF ALKALI ACTIVATED SLAG GEOPOLYMER CEMENT PASTES. Ceramics (Praha) 2015, 59, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Allahverdi, A.; Škvára, F. Nitric acid attack on hardened paste of geopolymeric cements. Ceramics - Silikaty 2001, 45, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Cherki El Idrissi, A.; Rozière, E.; Darson-Balleur, S.; et al. Resistance of alkali-activated grouts to acid leaching. Construction and Building Materials 2019, 228, 116681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandlez-Jimenez, A.G.I.P.A. Durability of alkali-activated fly ashcementitious matcrials. Jounal of Matcrials Scicncc 2007, 9, 3055–3065. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Yao, X.; Yang, T.; et al. The degradation mechanisms of alkali-activated fly ash/slag blend cements exposed to sulphuric acid. Construction & building materials 2018, 186, 1177–1187. [Google Scholar]

- Aliques-Granero, J.; Tognonvi, T.M.; Tagnit-Hamou, A. Durability test methods and their application to AAMs: case of sulfuric-acid resistance. Materials and structures 2016, 50, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Zhang, L.; San Nicolas, R. Degradation process of alkali-activated slag/fly ash and Portland cement-based pastes exposed to phosphoric acid. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 232, 117209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Lin, X.; Pan, W.; et al. Study on corrosion mechanism of alkali-activated concrete with biogenic sulfuric acid. Construction & building materials 2018, 188, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Lin, X.; Ji, T.; et al. Comparison of corrosion resistance mechanism between ordinary Portland concrete and alkali-activated concrete subjected to biogenic sulfuric acid attack. Construction & building materials 2019, 228, 117071. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Z. Research on the properties of alkali-excited composite cinder (AAW) concrete [D]. Chongqing University, 2006.

- Asaad, M.A.; Huseien, G.F.; Memon, R.P.; et al. Enduring performance of alkali-activated mortars with metakaolin as granulated blast furnace slag replacement. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2022, 16, e845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.K.; Lee, H.K. Influence of the slag content on the chloride and sulfuric acid resistances of alkali-activated fly ash/slag paste. Cement and Concrete Composites 2016, 72, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, P.; Gluth, G.J.G.; Jäger, C.; et al. Sulfuric acid resistance of one-part alkali-activated mortars. Cement and Concrete Research 2018, 109, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huseien, G.F.; Shah, K.W. Durability and life cycle evaluation of self-compacting concrete containing fly ash as GBFS replacement with alkali activation. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 235, 117458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie Ren, P.D.; Lihai Zhang, P.D.; Rackel San Nicolas, P.D. Degradation of Alkali-Activated Slag and Fly Ash Mortars under Different Aggressive Acid Conditions. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2021, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M.G.; Fourie, C. Performance of sewer pipe concrete mixtures with portland and calcium aluminate cements subject to mineral and biogenic acid attack. Materials and structures 2011, 44, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Fan, Z.; Li, X.; et al. Characterization and Comparison of Corrosion Layer Microstructure between Cement Mortar and Alkali-Activated Fly Ash/Slag Mortar Exposed to Sulfuric Acid and Acetic Acid. Materials (Basel) 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R.R.; Provis, J.L.; van Deventer, J.S.J. Acid resistance of inorganic polymer binders. 1. Corrosion rate. Materials and structures 2011, 45, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ana Mellado, M.I.P.J. Resistance to acid attack of alkali-activated binders: Simple new techniques to measure susceptibility. Construction and Building Materials 2017, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teymouri, M.; Behfarnia, K.; Shabani, A. Mix Design Effects on the Durability of Alkali-Activated Slag Concrete in a Hydrochloric Acid Environment. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 13, 8096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Min, S.; Lun, D. Research progress on mechanical properties and erosion products of sulfate-eroded concrete. China Concrete and Cement Products 2019, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Jun, D.; Dietmar, S.; et al. Experimental study on the durability of alkali-stimulated slag concrete under the action of erosive media. Concrete 2021, 82–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, H.; Chen, Z.; Huang, L. Mechanism of sulfate attack on alkali-activated slag: The role of activator composition. Cement and concrete research 2019, 125, 105868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, L.B.; de Azevedo, A.R.G.; Marvila, M.T.; et al. Durability of geopolymers with industrial waste. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2022, 16, e839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Puertas, F.; Sobrados, I.; et al. Structure of Calcium Silicate Hydrates Formed in Alkaline-Activated Slag: Influence of the Type of Alkaline Activator. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 2003, 86, 1389–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, I.; Bernal, S.A.; Provis, J.L.; et al. Microstructural changes in alkali activated fly ash/slag geopolymers with sulfate exposure. Materials and Structures 2013, 46, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhi, C. Discussion on the mechanism of alkali-inspired cementitious materials against sulfate erosion. Journal of Zhengzhou University (Engineering Edition) 2012, 33, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, J.; Liu, L.; He, Y.; et al. Early mechanical properties and microstructural evolution of slag/metakaolin-based geopolymers exposed to karst water. Cement & concrete composites 2019, 99, 140–150. [Google Scholar]

- Rashad, A.M.; Bai, Y.; Basheer, P.A.M.; et al. Hydration and properties of sodium sulfate activated slag. Cement and Concrete Composites 2013, 37, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binici, H.; Kapur, S.; Arocena, J.; et al. The sulphate resistance of cements containing red brick dust and ground basaltic pumice with sub-microscopic evidence of intra-pore gypsum and ettringite as strengtheners. Cement & concrete composites 2012, 34, 279–287. [Google Scholar]

- Ping, W. Study on the microstructure of hydrated C-A-S-H gel of alkali excited slag cement. Silicate Bulletin 2019, 38, 1062–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Provis, J.L.; Myers, R.J.; White, C.E.; et al. X-ray microtomography shows pore structure and tortuosity in alkali-activated binders. Cement and concrete research 2012, 42, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, L.; Coffetti, D.; Crotti, E.; et al. The Durability of One-Part Alkali-Activated Slag-Based Mortars in Different Environments. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland) 2020, 12, 3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Reaction mechanism of sulfate attack on alkali-activated slag/fly ash cements. Construction & building materials 2022, 318, 126052. [Google Scholar]

- Mithun, B.M.; Narasimhan, M.C. Performance of alkali activated slag concrete mixes incorporating copper slag as fine aggregate. Journal of Cleaner Production 2016, 112, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydın, S.; Baradan, B. Sulfate resistance of alkali-activated slag and Portland cement based reactive powder concrete. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 43, 103205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Z. Carbonation, chloride binding and sulfate erosion resistance of alkali slag/fly ash cement [D]. Hunan University, 2019.

- Wang, A.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; et al. The Durability of Alkali-Activated Materials in Comparison with Ordinary Portland Cements and Concretes: A Review. Engineering (Beijing, China) 2020, 6, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.R.; Chen, B.; Shah, S.F.A. Influence of different admixtures on the mechanical and durability properties of one-part alkali-activated mortars. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 265, 120320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, X.; Yang, K.; et al. The long-term failure mechanisms of alkali-activated slag mortar exposed to wet-dry cycles of sodium sulphate. Cement and Concrete Composites 2021, 116, 103893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, S.; Zhe, Y.; Wei, L.; et al. Sand consolidation characteristics and sulfate erosion resistance of alkali slag cementitious materials. Materials Reports 2020, 34, 10061–10067. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, W. Sand consolidation characteristics and sulfate erosion resistance of alkali slag cementitious materials. Chemical Engineering Management 2020, 34, 64–65. [Google Scholar]

- Jie, C. Research on service performance mechanism and pore solution of alkali-excited slag concrete under sulfate dry and wet cycles [D]. Qingdao University of Technology, 2018.

- Zhu, H.; Liang, G.; Li, H.; et al. Insights to the sulfate resistance and microstructures of alkali-activated metakaolin/slag pastes. Applied Clay Science 2021, 202, 105968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikal, M.; Nassar, M.Y.; El-Sayed, G.; et al. Physico-chemical, mechanical, microstructure and durability characteristics of alkali activated Egyptian slag. Construction & building materials 2014, 69, 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Karakoç, M.B.; Türkmen, İ.; Maraş, M.M.; et al. Sulfate resistance of ferrochrome slag based geopolymer concrete. Ceramics International 2016, 42, 1254–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, B.; Sheng, Y.; Wei, C. Research on sulfate erosion resistance of alkali slag concrete. Concrete 2019, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Hua, Y. Study on sulfate erosion resistance of alkali slag concrete and cement concrete. Concrete and Cement Products 2021, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, K.; White, C.E. Nanoscale Chemical Degradation Mechanisms of Sulfate Attack in Alkali-activated Slag. Journal of physical chemistry. 2018, 122, 5992–6004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakharev, T.; Sanjayan, J.G.; Cheng, Y.B. Sulfate attack on alkali-activated slag concrete. Cement and Concrete Research 2002, 32, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komljenovic, M.; Bascarevic, Z.; Marjanovic, N.; et al. External sulfate attack on alkali-activated slag. Construction & building materials 2013, 49, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kirezci, E.; Young, I.R.; Ranasinghe, R.; et al. Projections of global-scale extreme sea levels and resulting episodic coastal flooding over the 21st Century. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 11629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. K. Mehta P J M M. Concrete: Microstructure, Properties, and Materials. McGraw-Hill Education, 2005.

- Shi, J.; Wu, M.; Ming, J. Long-term corrosion resistance of reinforcing steel in alkali-activated slag mortar after exposure to marine environments. Corrosion Science 2021, 179, 109175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Xin, H. Experiment on the effect of chloride salt on the strength of alkali-excited slag net slurry. Journal of Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics 2015, 41, 693–700. [Google Scholar]

- Babaee, M.; Castel, A. Chloride diffusivity, chloride threshold, and corrosion initiation in reinforced alkali-activated mortars: Role of calcium, alkali, and silicate content. Cement and Concrete Research 2018, 111, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, Y.; Yoon, S.; Oh, J. A Comparison Study for Chloride-Binding Capacity between Alkali-Activated Fly Ash and Slag in the Use of Seawater. Applied sciences 2017, 7, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengasini, L.; Mavroulidou, M.; Gunn, M.J. Alkali-activated concrete mixes with ground granulated blast furnace slag and paper sludge ash in seawater environments. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy 2021, 20, 100380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, I.; Tadic, M.; Jankovic-Castvan, I.; et al. Durability of alkali activated slag in a marine environment: Influence of alkali ion. Journal of the Serbian Chemical Society 2018, 83, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, X.; Singh Raman, R.K.; et al. Thermal and mechanical properties of alkali-activated slag paste, mortar and concrete utilising seawater and sea sand. Construction and Building Materials 2018, 159, 704–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Xu, J.; Zang, C.; et al. Mechanical properties of alkali-activated slag concrete mixed by seawater and sea sand. Construction & building materials 2019, 196, 395–410. [Google Scholar]

- Rashad, A.M.; Sadek, D.M. An Exploratory Study on Alkali-Activated Slag Blended with Microsize Metakaolin Particles Under the Effect of Seawater Attack and Tidal Zone. Arabian journal for science and engineering ( 2011), 2021. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).