3.1. Phase Behaviour of Ferroparticles in a Liquid Crystal Polymer

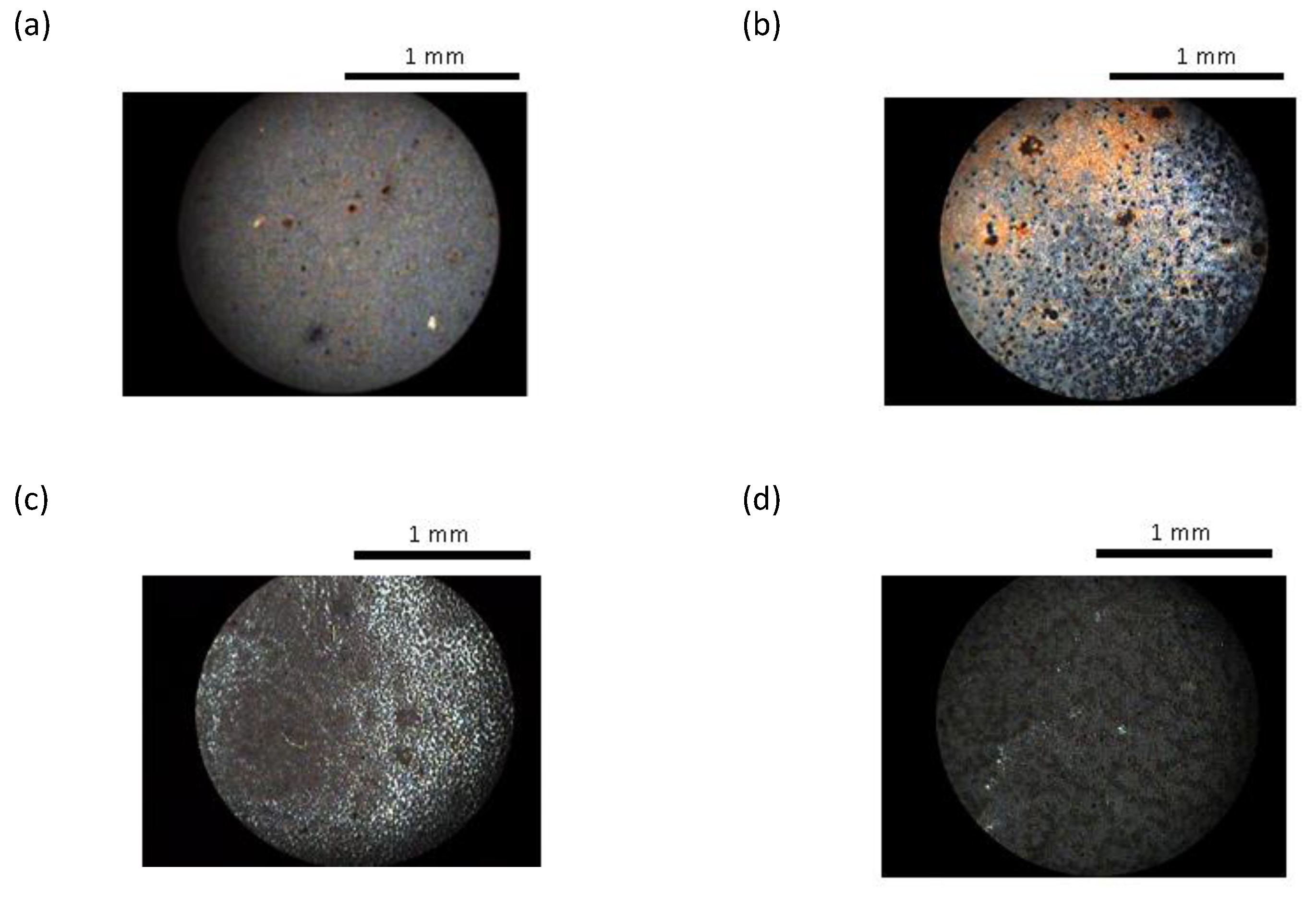

Mixtures of the nematic polymers with different quantities of ferroparticles were prepared in the way described above and observed under a polarizing optical microscope. Selected images are shown in

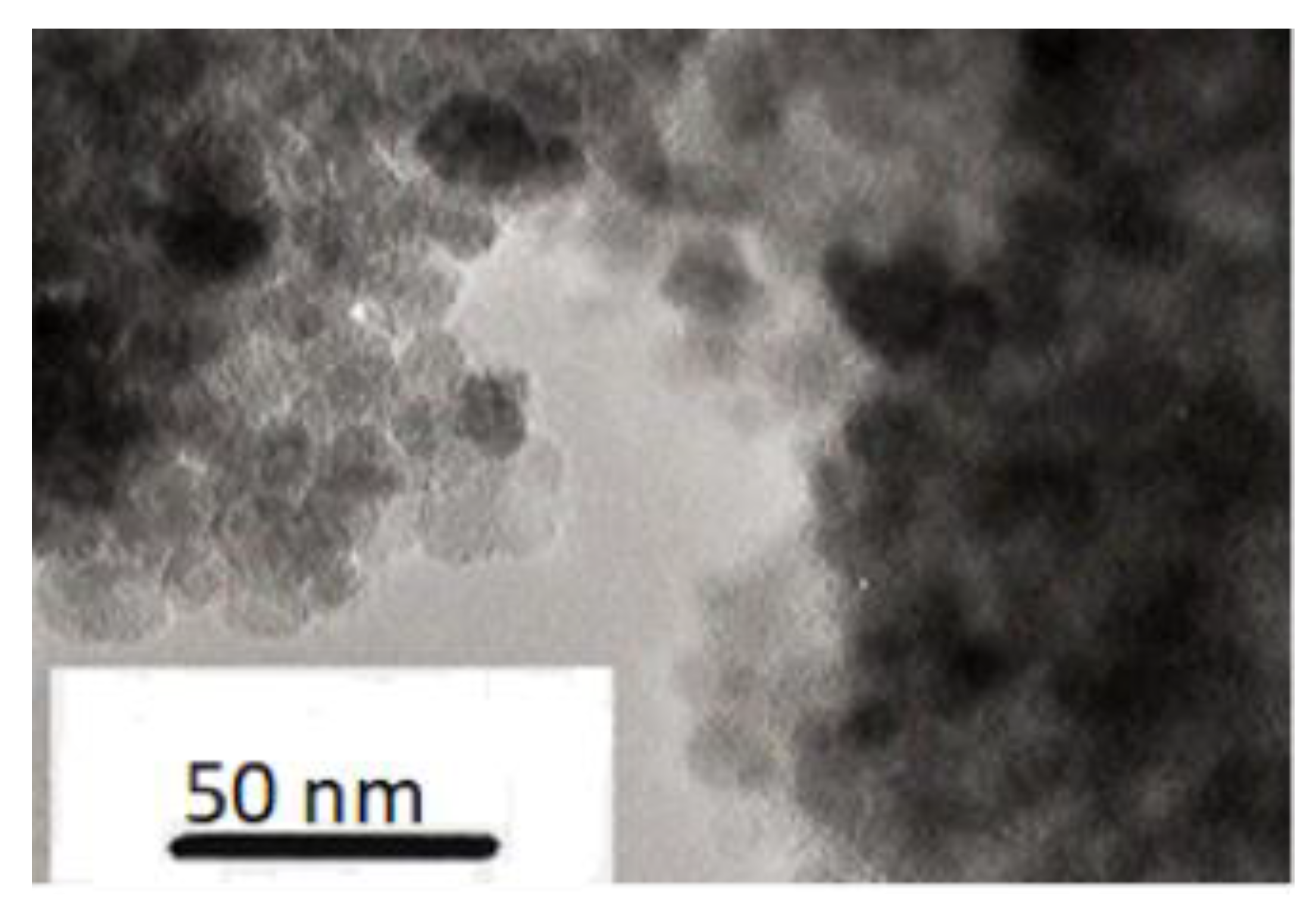

Figure 8; as the ferroparticle content was increased to around 1.42 % by volume, black objects were observed in the mixture (

Figure 8 a). As the ferroparticle content was increased further, the quantity of these objects was increased and the birefringence decreased; at around 5.68 % by volume of ferroparticles added, a black network was observed in the liquid crystal texture (

Figure 8c). These dark objects were also observed in the isotropic phase and were unchanged in the presence of a magnetic field although here the birefringence became directional if in the nematic phase.

At low concentrations of ferroparticles the liquid crystal texture appears unchanged; for example at 1 % there appears to be no phase separation. At higher concentrations phase separation occurs, the ferroparticles formed aggregates in the liquid crystal polymer matrix. At the highest concentrations examined, the ferroparticles formed a network structure within the liquid crystal polymer, which became denser with increasing concentration. This network formation was related to a decrease in the birefringence.

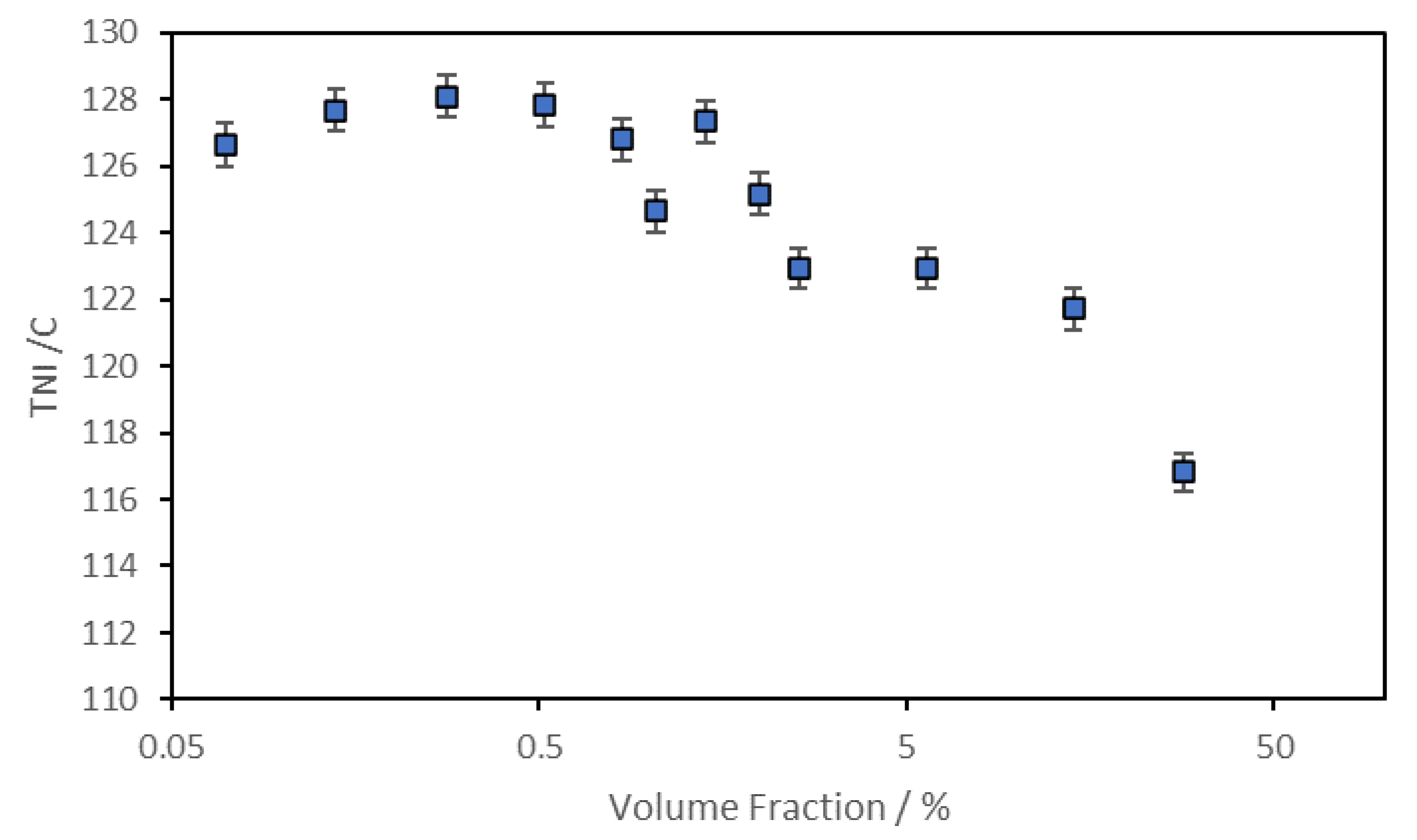

The influence of the ferroparticles on the phase behaviour was further monitored by measurement of the nematic isotropic transition temperature; the data is presented in

Figure 9. All the samples were prepared by casting films from dichloromethane and so are directly comparable. Small quantities of ferroparticles to CBZ6 increased the TNI by up to 2° C. Addition of ferroparticles has also been reported to increase the smectic A to nematic transition temperature in another liquid crystal system [

21]. The behaviour of this system is broadly in line with theoretical expectations [

22] Once a plateau had been reached the TNI was reduced by the addition of further ferroparticles, thus a small quantity of ferroparticles stabilises the liquid crystal phase, but once a certain concentration is reached it acts as an impurity and starts to reduce the stability of the liquid crystal phase, and there is some phase separation.

3.2. Monodomain Formation

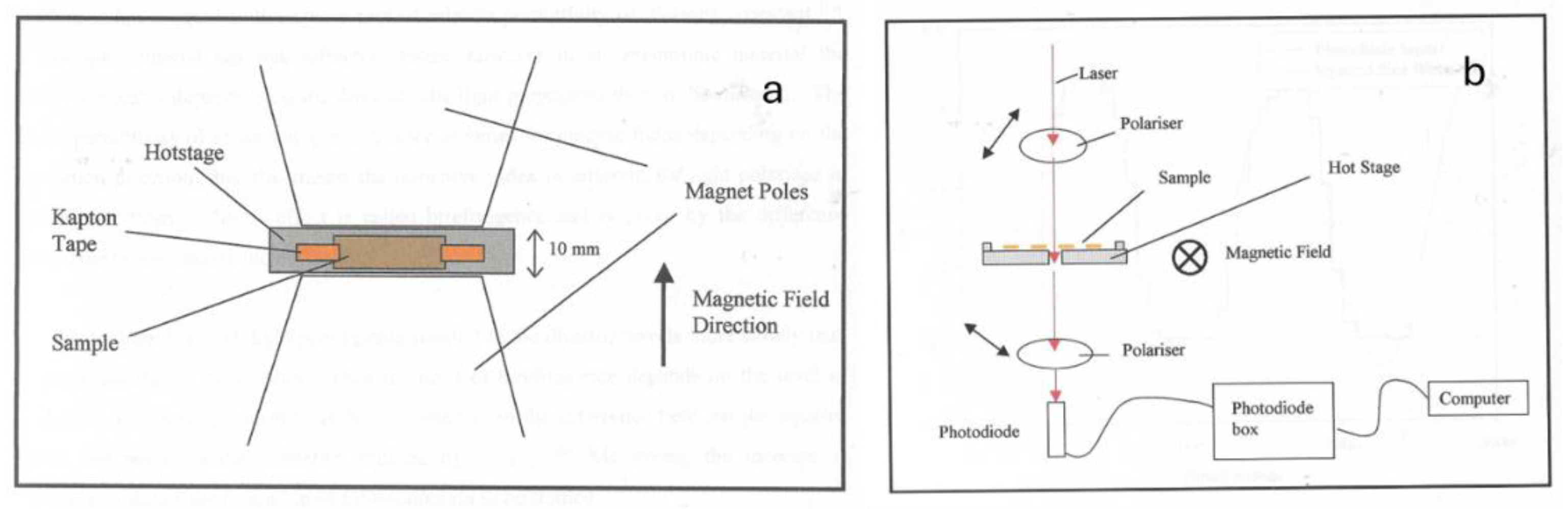

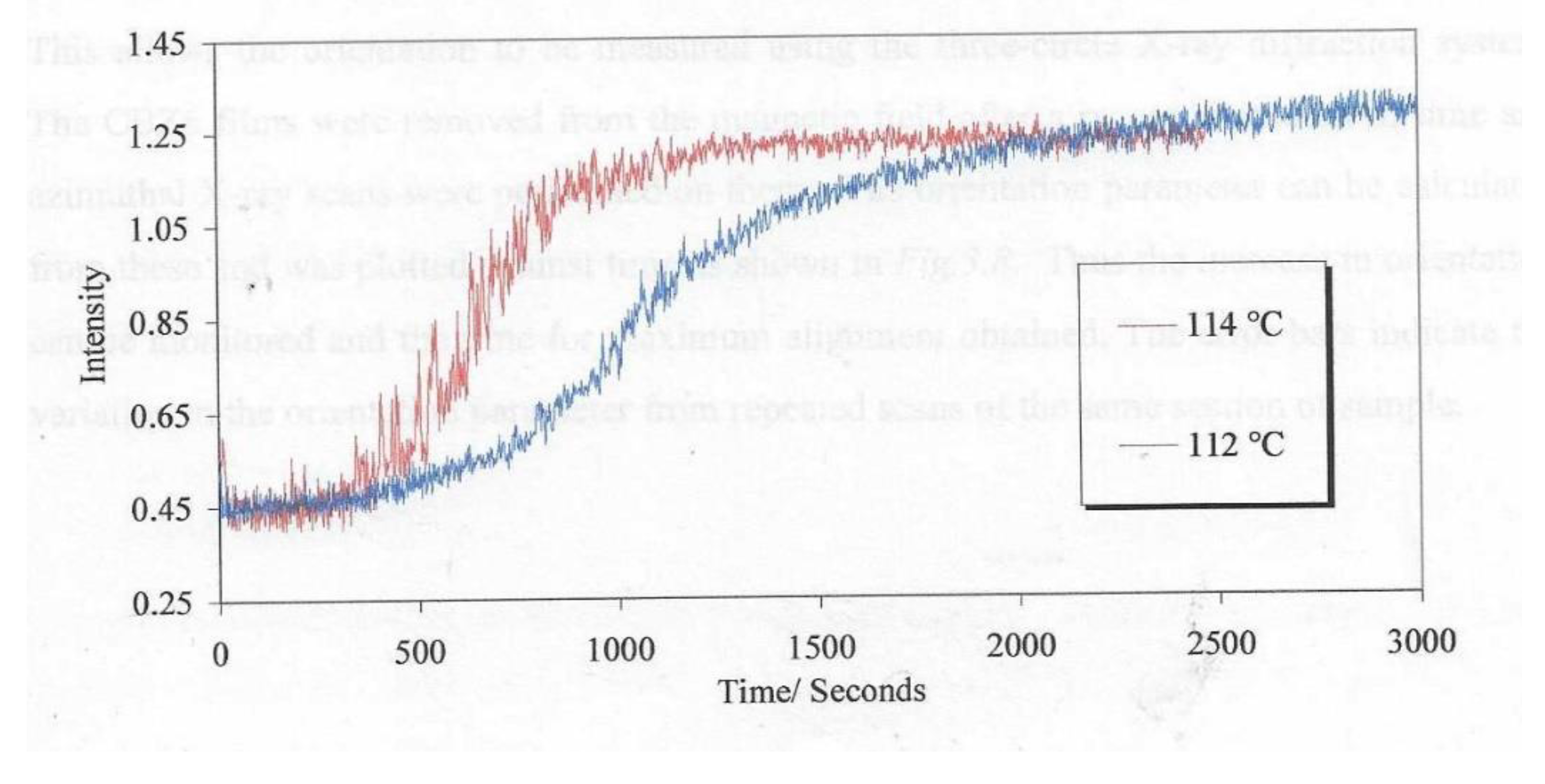

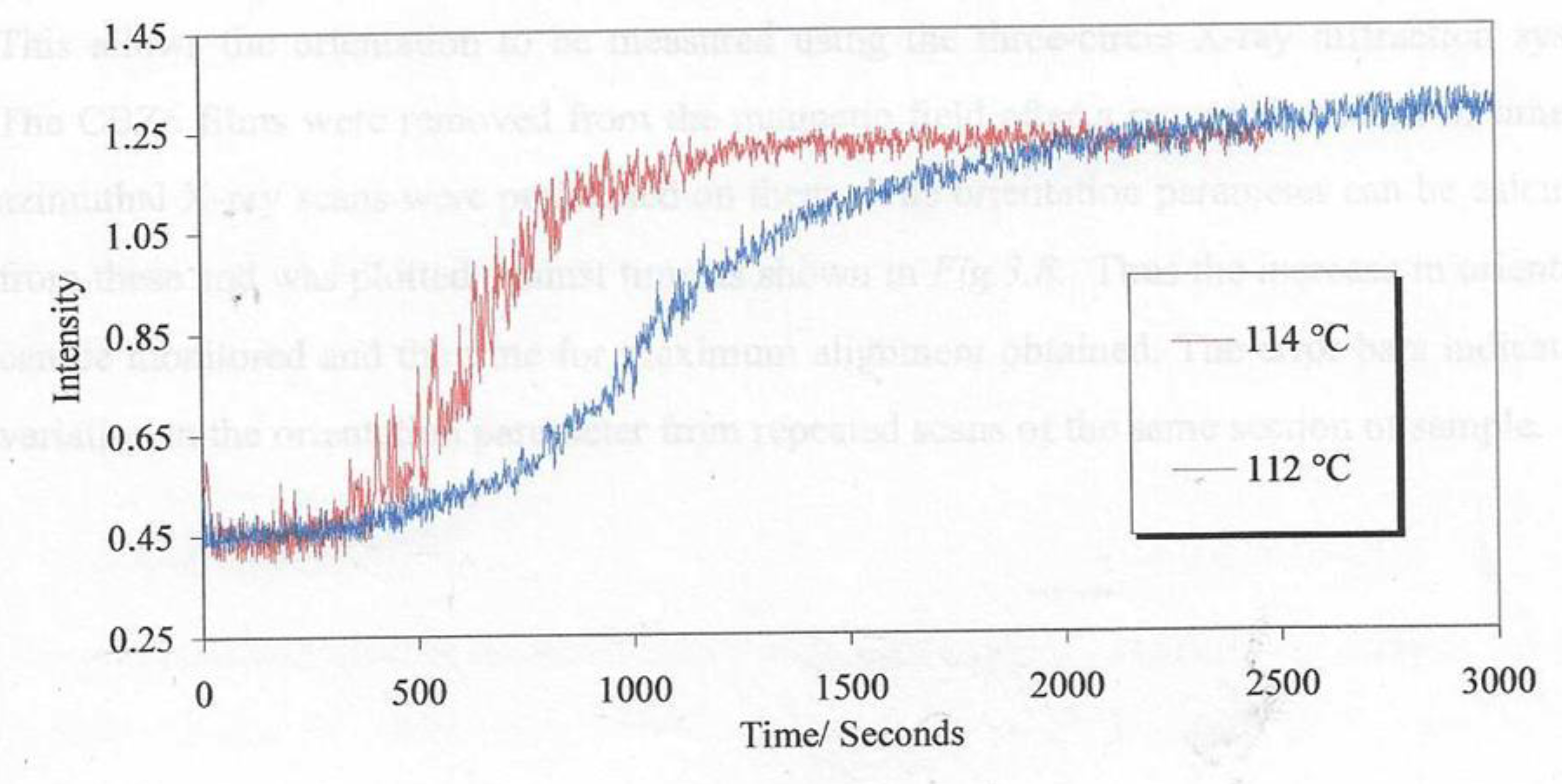

Figure 10 show a plot of the measured light using the system with cross-polarisers as shown in

Figure 4b. There is a clearly a significant temperature effect.

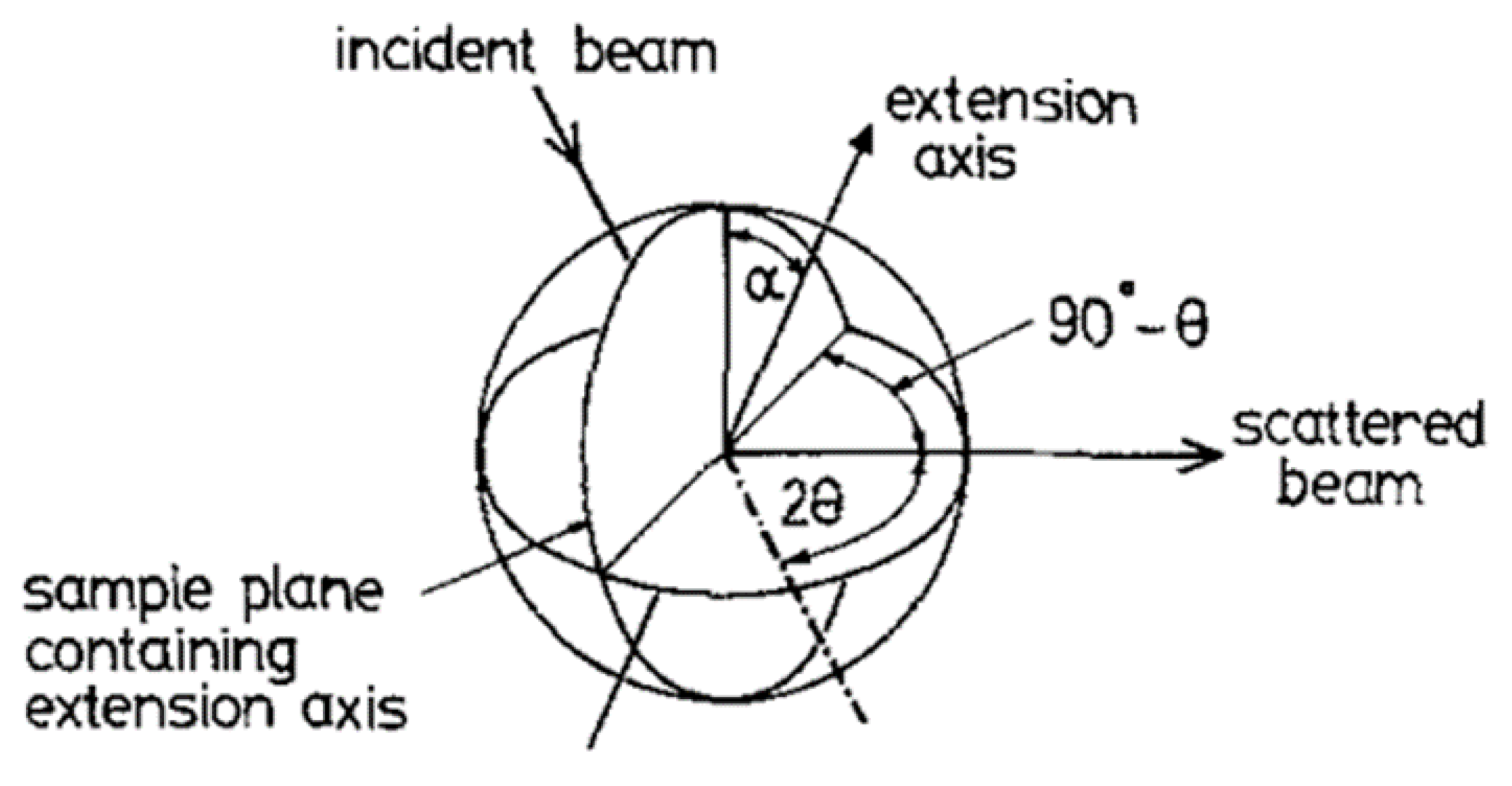

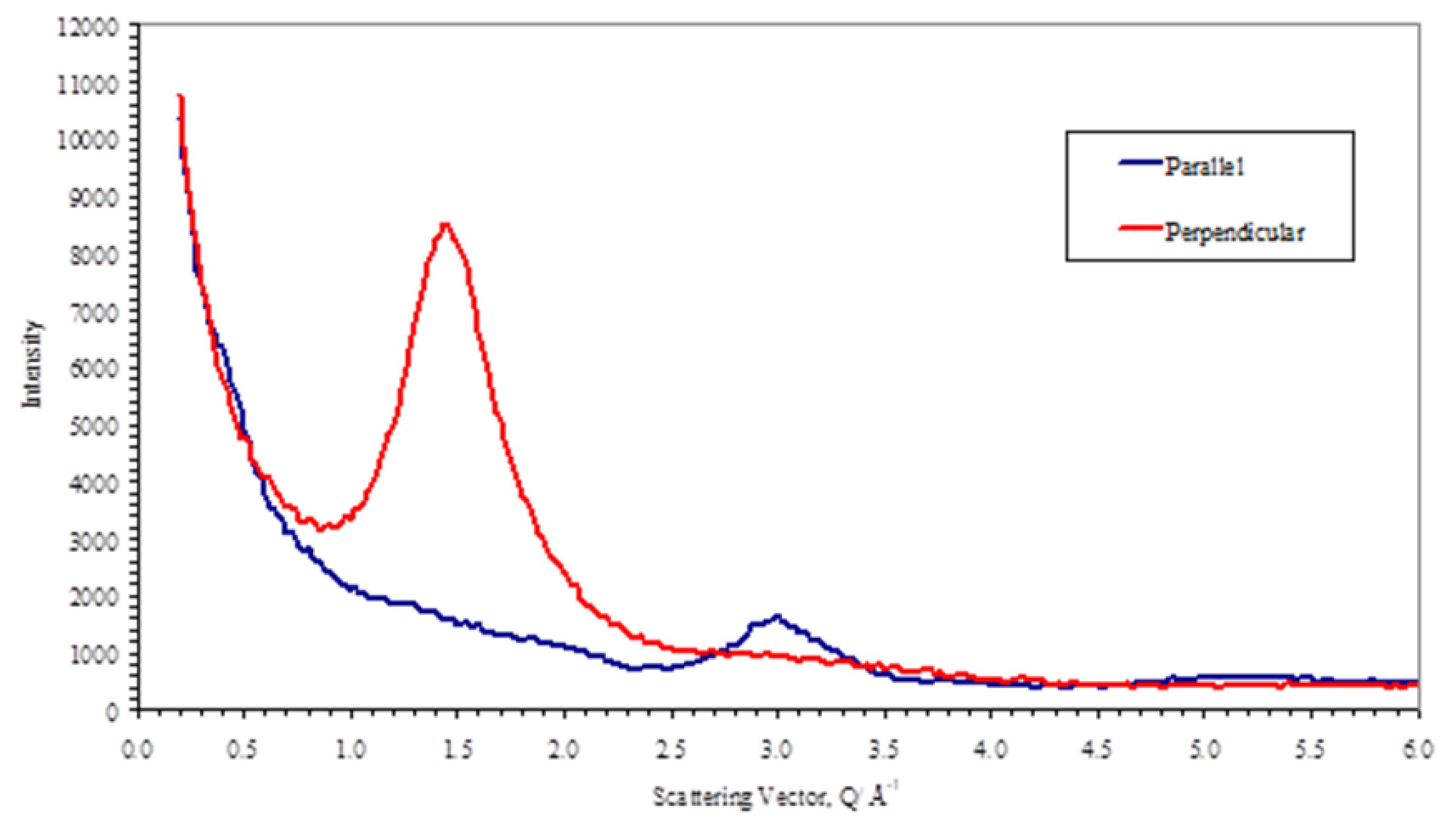

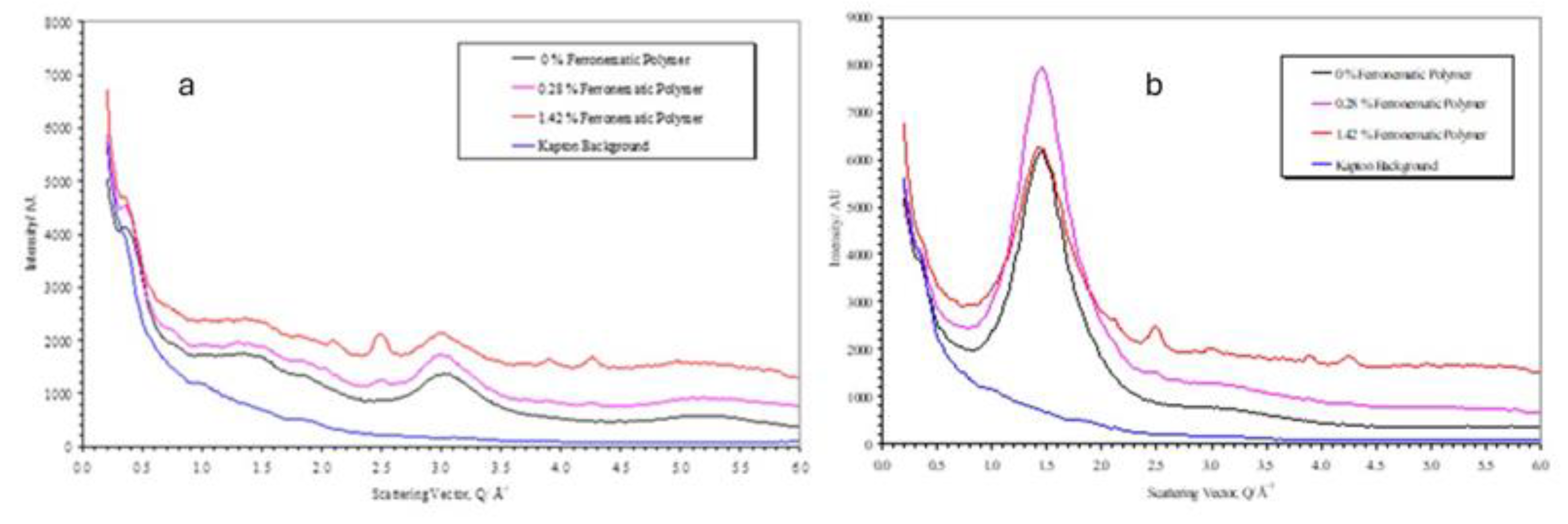

We also used wide-angle x-ray scattering measurements performed using the 3circle Diffractometer.

Figure 11 shows a plot of the intensity recorded parallel and perpendicular to the monodomain director or the direction of the applied magnetic field. The intense broad peak at Q ~ 1.44Å

-1 arises from the short range correlations between the mesogenic side chains and we use the azimuthal variation in this peak to evaluate the global orientation parameter <P

2> which as indicated earlier is the product of the nematic order parameter S and the domain director orientation parameter <D

2>. This process of quantitative evaluation is described in [

23,

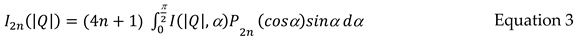

24] and is a mathematically robust procedure which is summarized below. The scattering pattern I(|Q|, α) expressed as a series of amplitudes of spherical harmonics I

2n(|Q|), where only the even harmonics are required due to the present of an inversion centre in the scattering pattern [

23]. The amplitude of each harmonic is evaluated using equation 3 [

23]

Where P2n(cos) are a series of Legendre polynomials. The Global orientation parameters <P2n(cos)> can be found at a |Q| value corresponding to the maximum intensity for the structural element of interest using Equation 4

Where P

m2n are the values calculated for the scattering from a perfectly aligned structure. Reference [

24] gives some values for common structures. In this study we are using the scattering arising from the correlations between the mesogenic side-groups which gives a peak in the scattering at |

Q|~ 1.44Å

-1 which intensifies on the equatorial section. Th advantage of using this feature is that it is the more intense feature in the scattering pattern and it is well separated from other structural features.

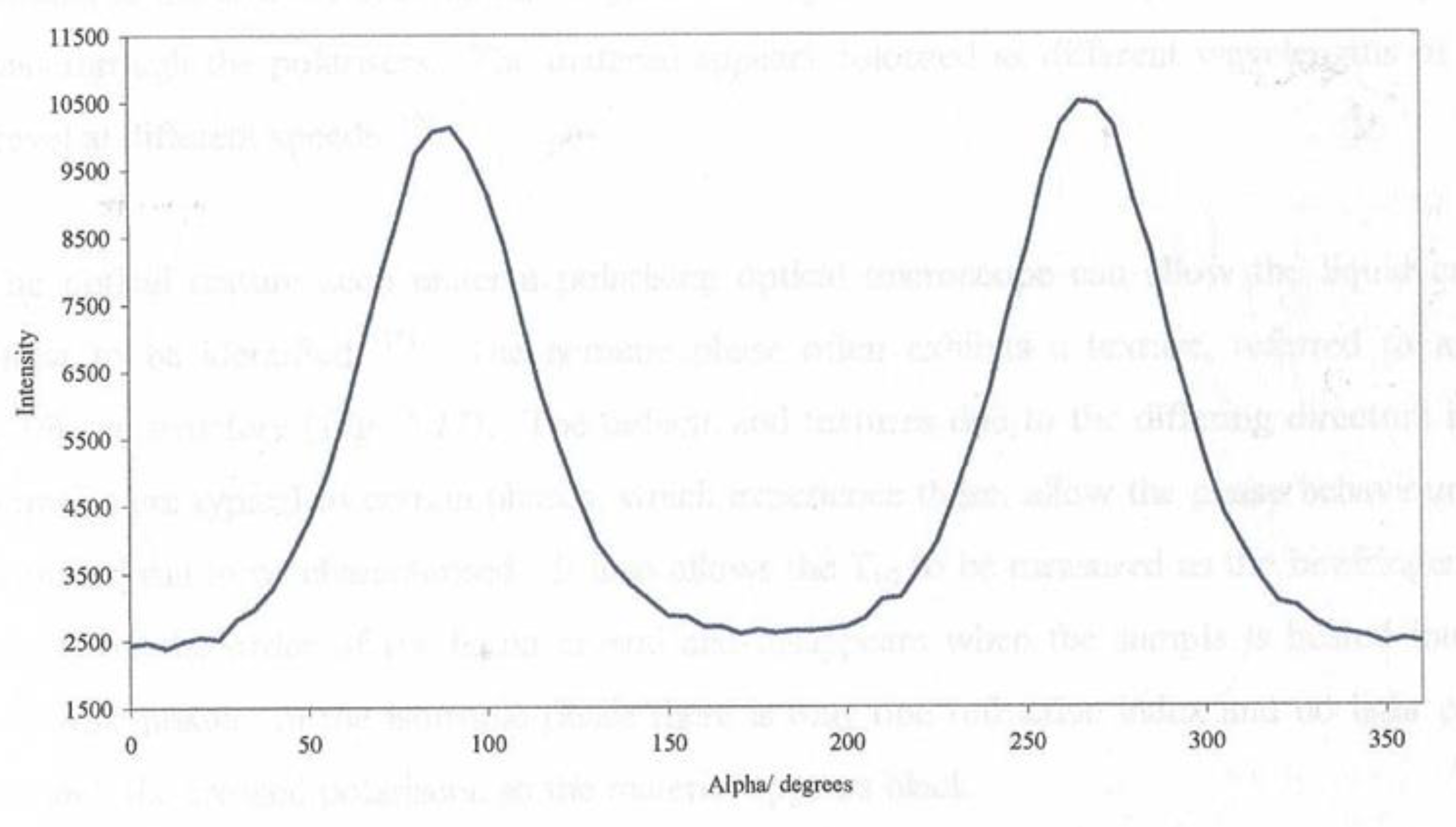

Figure 12 shows a plot of the I() at a fixed value of |Q|= 1. 44Å

-1 used to evaluate the global orientation parameters <P2n>. The plot shows a symmetrical curve which Is inherent to the scattering data for a weakly-absorbing sample such as CBZ6. The intensification of the peak at 90° and 270° indicates directly that the long-axis of the mesogenic groups lie parallel to the magnetic field direction as is expected for mesogens which exhibit a positive diamagnetic anisotropy. A more complete structural analysis is given in references [

19].

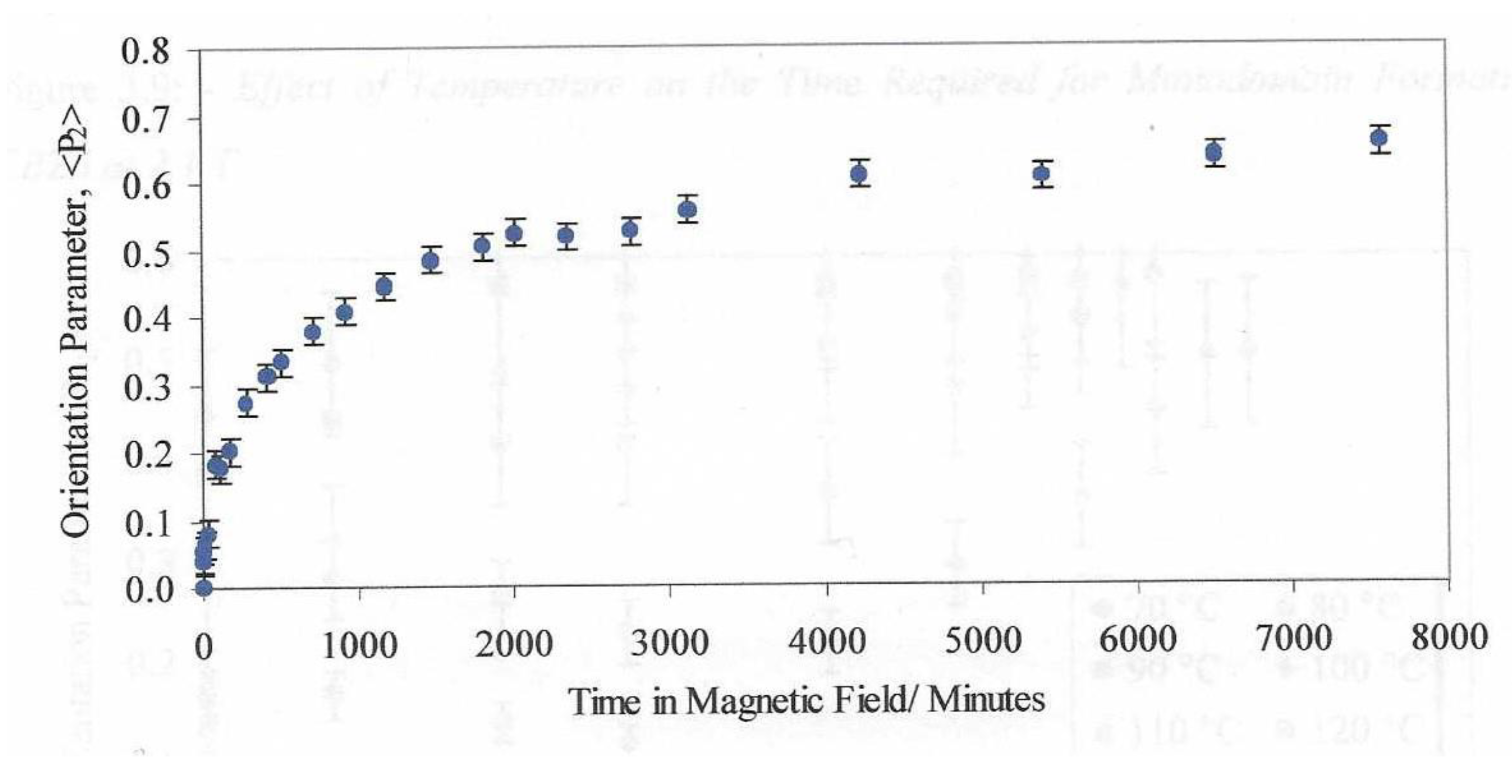

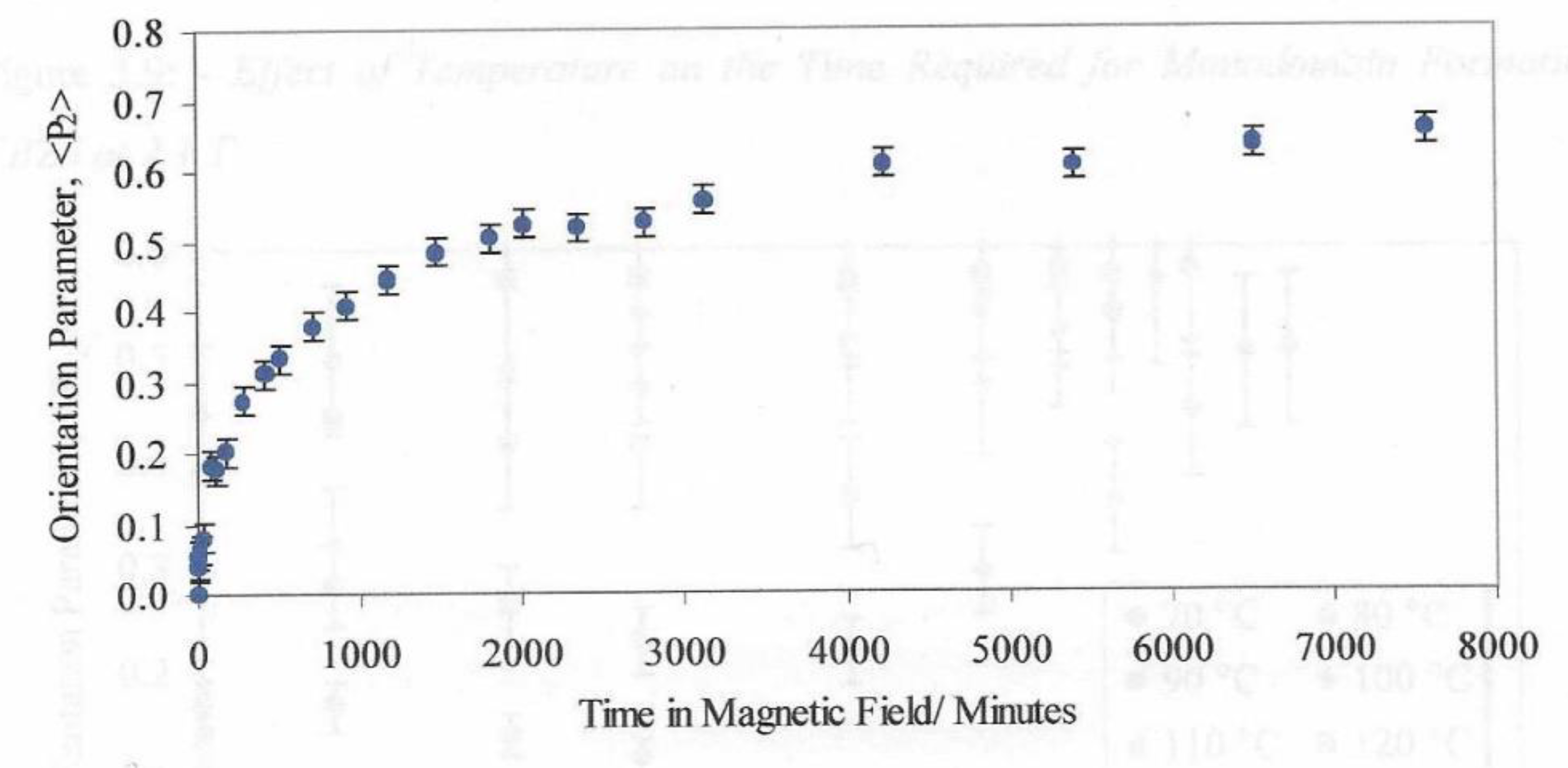

The plot of orientation parameter <P2> is shown in

Figure 10 for the liquid crystal held at 90° C and using a magnetic field of 2.1T. These data were obtained by periodically removing the sample from the hotstage where upon it cooled to below the glass transition which froze in the structure and any relaxation processes were inhibited.

The plot of orientation parameter <P2> is shown in

Figure 10 for the liquid crystal held at 90° C and using a magnetic field of 2.1T. These data were obtained by periodically removing the sample from the hotstage where upon it cooled to below the glass transition which froze in the structure and any relaxation processes were inhibited.

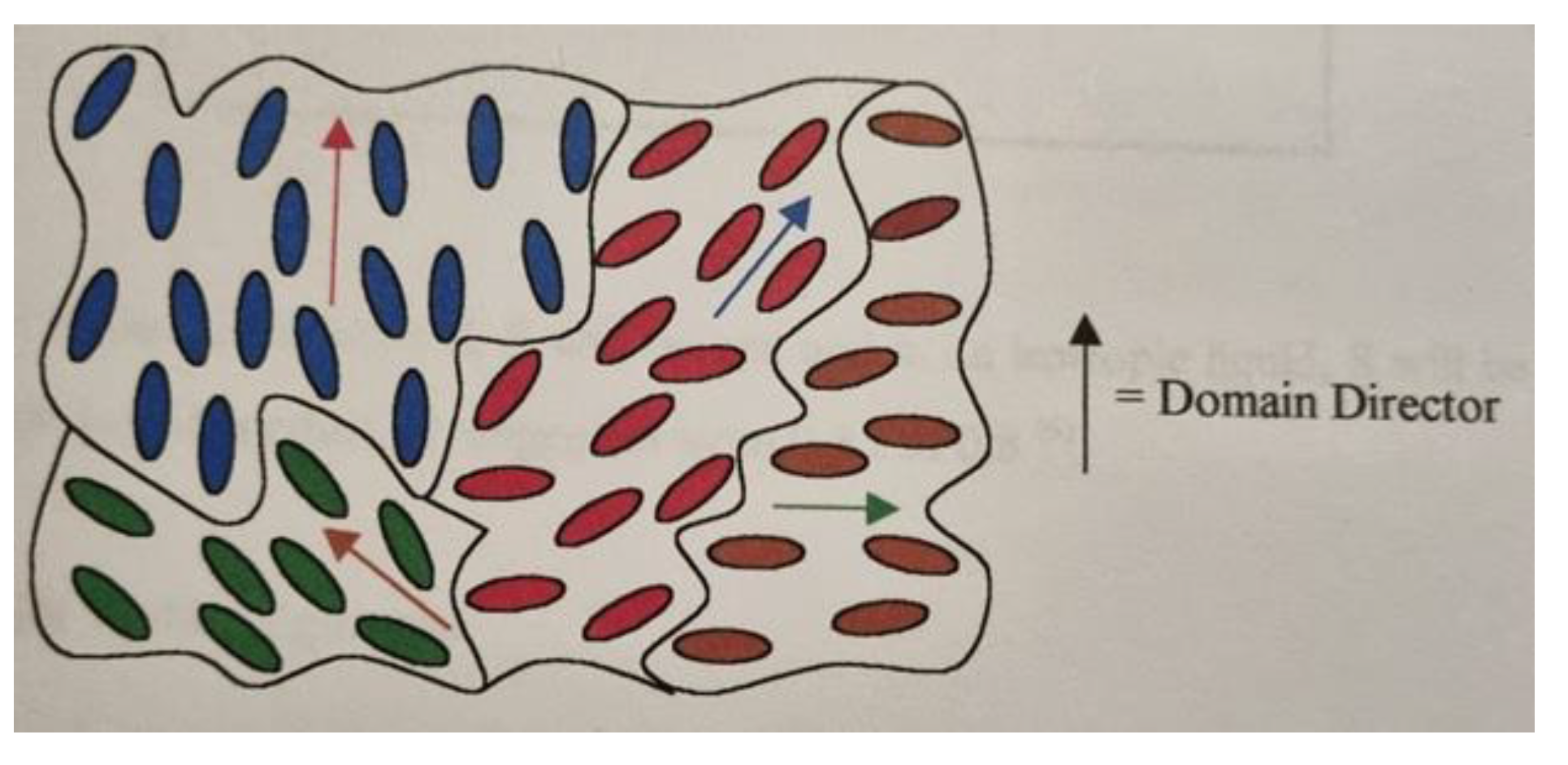

Figure 5 shows a plot of the global orientation parameter against time in a magnetic field of 2.1T. We can identify a value of time at which the orientation value reaches 50% of the final value.

Figure 11 shows a plot of those times measured for a series of similar measurements made with different magnetic field values. The dashed line shows that fit to the expected variation as shown in Equation 2. We can see the variation follows the expected pattern.

Figure 10 shows the variation in these alignment times as a function of the applied magnetic field strength. The plot shows the strong effect that the magnetic field strength has on the alignment time. The magnetic fields we use in this work are at the limit due to the saturation of the magnetic field in the iron core pole pieces. Larger magnetic fields are available with air cored magnetics as in the case of superconducting magnets where fields up to 45T are possible. Clearly heating the sample in a cryogenically cooled bore is more challenging than the methodology presented here. It is interesting that the alignment times follow the 1/B2 model (equation 2) and We anticipated that the molecular weight would have a strong influence on the alignment times.

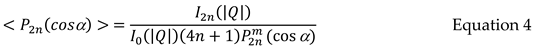

Figure 14 shows the global orientation parameter <P

2> plotted against time in a fixed magnetic field of 2.1T at 90° C against two samples of CBZ6 with differing molecular weights but otherwise chemically equivalent.

Figure 15.

A plot of the global orientation <P2> against time, for two sample of the liquid crystal polymer used in this work at 90° C and in a magnetic field of 2.1T. SIP198 has a Mw of 2,400,000 and a Mn of 28,250 SIP127 has a Mw of 27,600 and a MN of 13,200.

Figure 15.

A plot of the global orientation <P2> against time, for two sample of the liquid crystal polymer used in this work at 90° C and in a magnetic field of 2.1T. SIP198 has a Mw of 2,400,000 and a Mn of 28,250 SIP127 has a Mw of 27,600 and a MN of 13,200.

These differences can be attributed to the greater viscosity for the higher molecular weight polymer. The ratio of the alignment time is over a factor of 16. Now we turn attention to evaluating the behaviour of mixtures of the polymer with ferro nanoparticles. Wide angle X-ray scattering was used to probe the intermediate range structure (distances between neighbouring molecules).

Figure 16 shows the equivalent scans of the polymer plus differences volume fractions of the nanoparticles.

These curves are essential the same as shown in

Figure 8 for the polymer apart from the superposition of some small sharp bragg reflections arising from the magnetite in the nanoparticles. It is clear by comparison of the curves for the parallel and perpendicular sections that the magnetite scattering is isotropic. This was confirmed by azimuthual sections at the peak positions for the magnetite [

25] (for example at |Q|=2.1Å-1(220), |Q|=2.48Å-1(311), |Q|=3.89Å-1(511), |Q|=4.26Å-1(440). The background in these sections is higher than the polymer alone due to the X-ray fluorescence from the iron. For these samples, the Kapton substrate used in their fabrication before measurement of the X-ray scattering has not been removed and so this also contributes to the background, and this is also shown in

Figure 12.

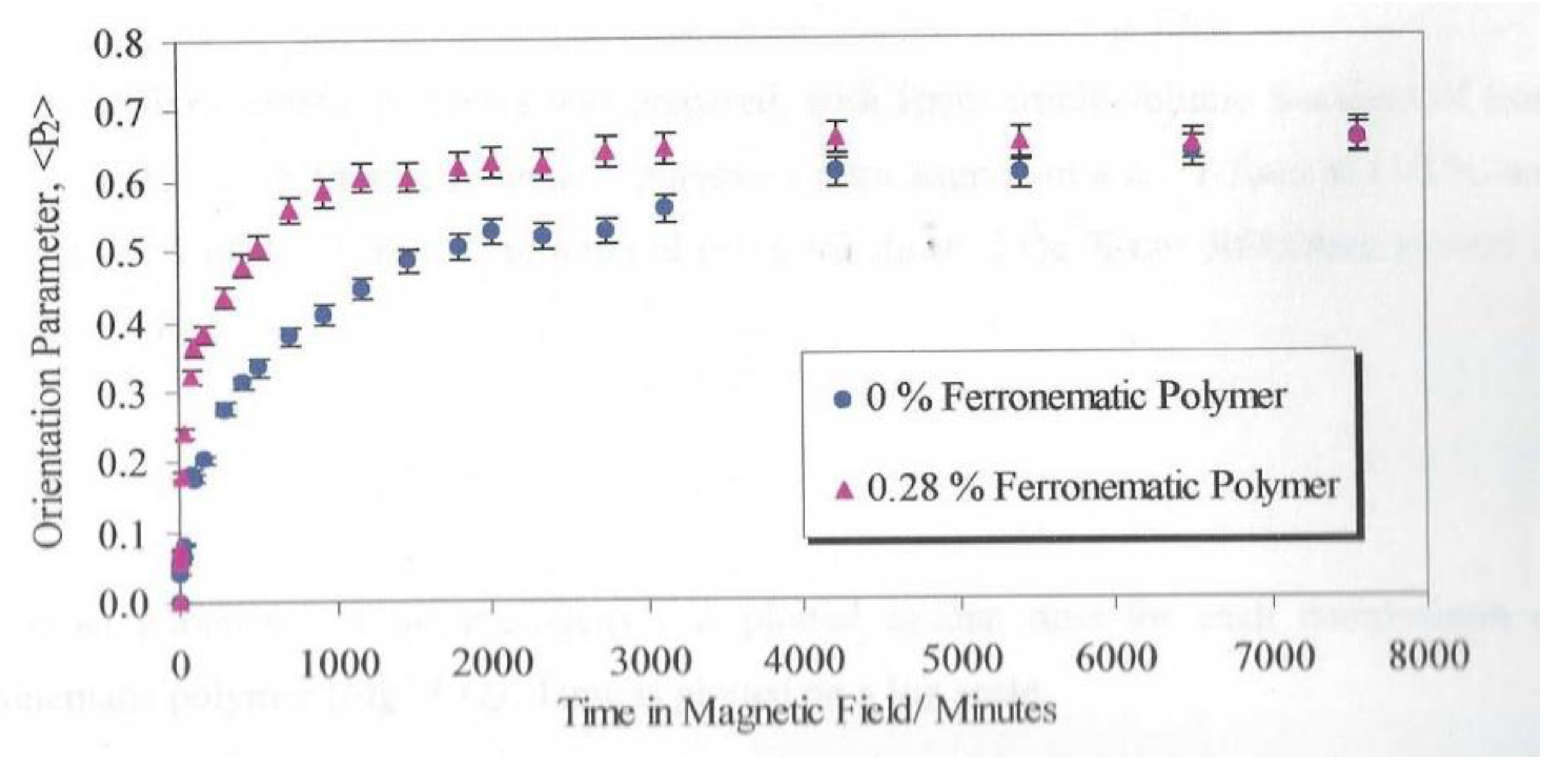

Figure 17 shows the development of the Global Orientation Parameter <P2> against time for samples of the polymer plus a small fraction of the nanoparticles.

A comparison of the two curves in

Figure 17 shows a remarkable change in the alignment time with the addition of the ferro nanoparticles. The time to reach 90% of the maximum value of <P

2> observed was reduced by a factor of 4 by the addition of 0.28% v/v of ferroparticles. In order to develop an understanding of the mechanism and the optimum fraction of ferro particles a range of polymer films with different composition ranging from 0.07% to 28.4%were prepared and the alignment time evaluated through repeated X-ray scattering measurements.

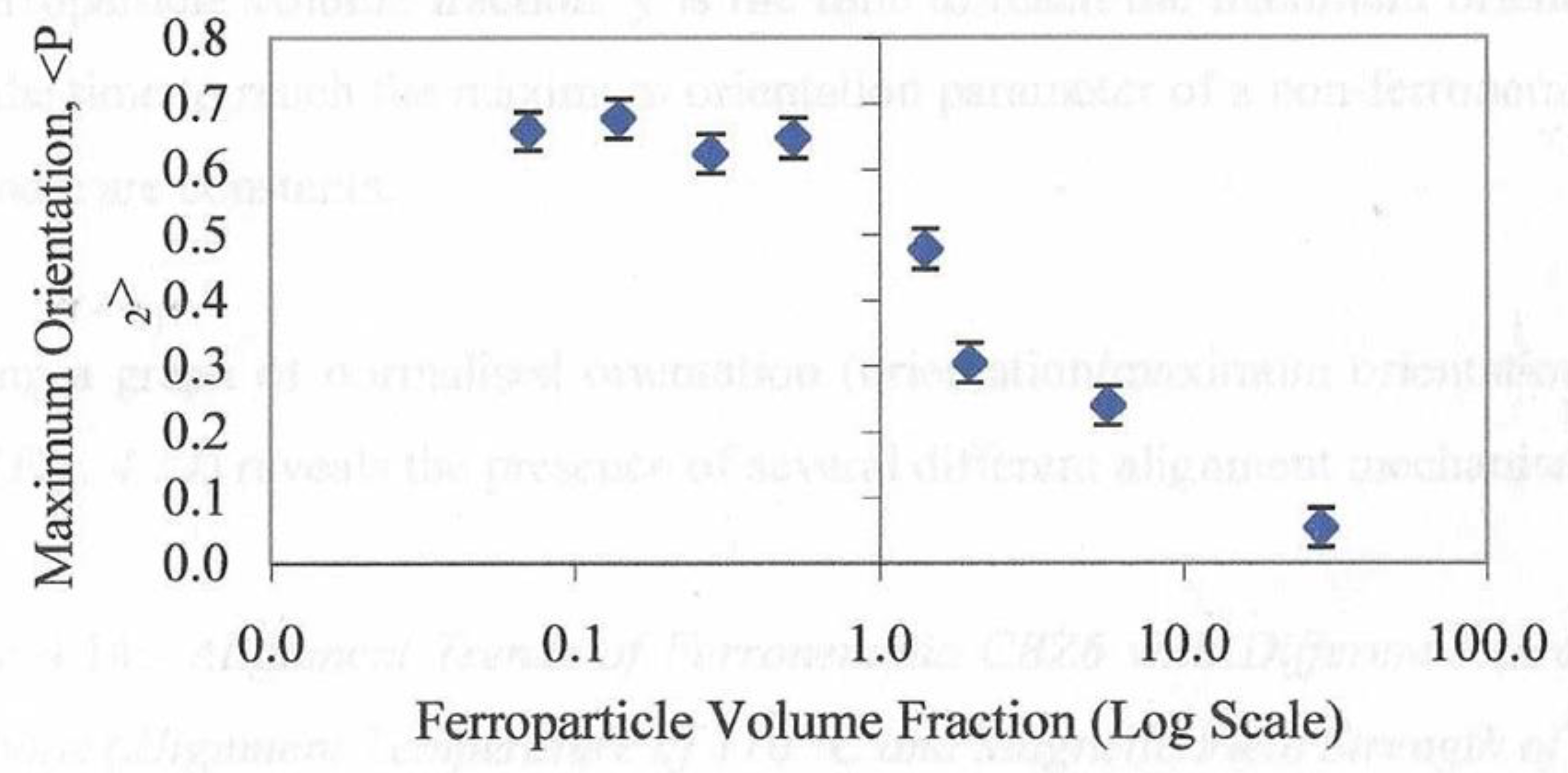

Figure 18 shows the maximum value of <P

2> for each composition were held in a magnetic field of 2.1T at a temperature of 110° C. There are two regions of this plot. At lower concentrations of the ferroparticles, the value of <P2> appears to exhibit a more or less constant value and the second region which shows a rapidly reducing value above a concentration of 0.52%. In the first region the ferroparticles appear to enhance or at least stabilize the maximum value of <P

2> whereas above a volume fraction of 0.52%, orientational order appears inhibited.

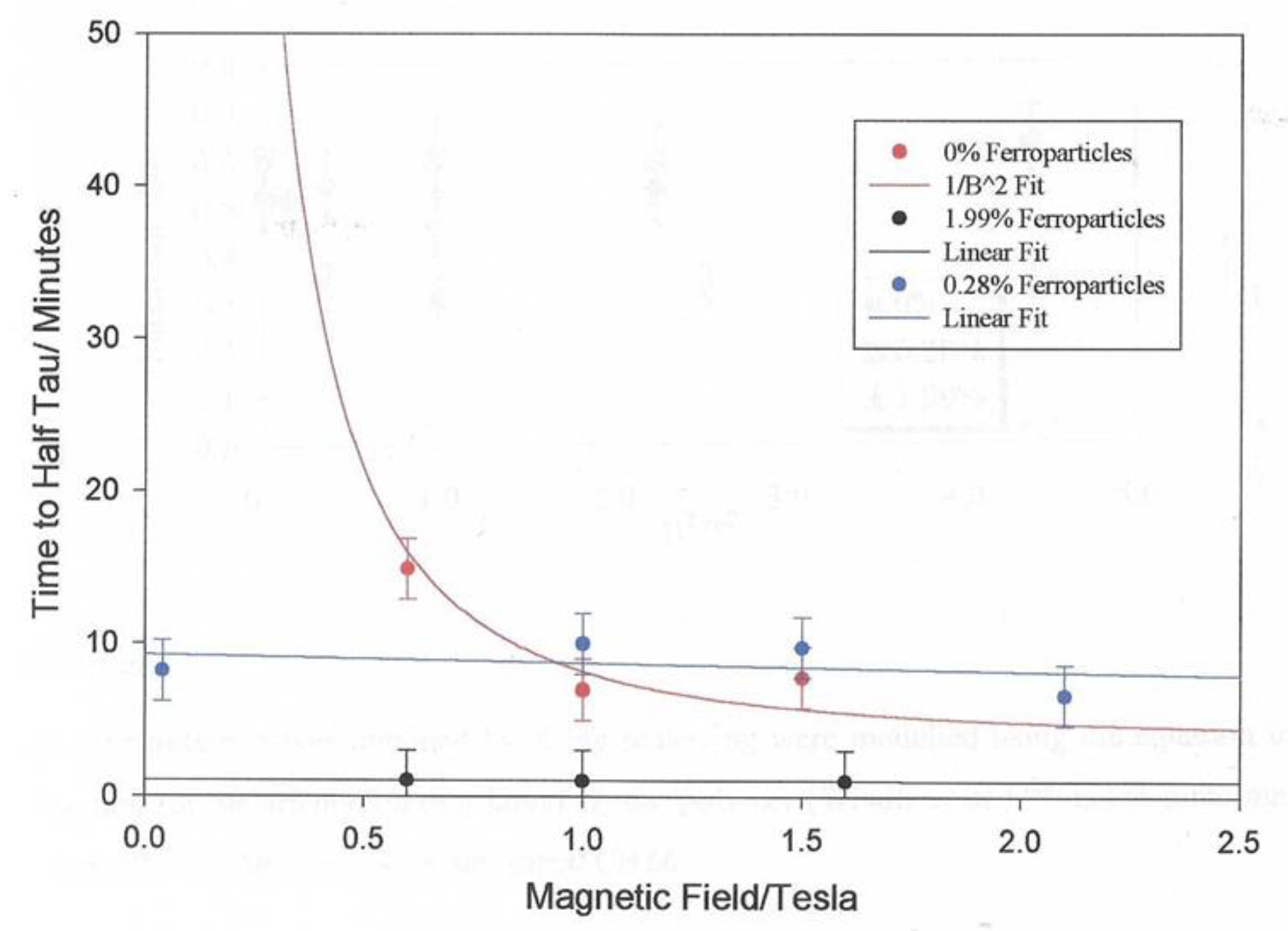

Figure 19 shows a plot of the alignment times of the monodomains formed from the mixture of the polymer and a small fraction of the ferroparticles and remarkably the alignment time is independent on the applied magnetic field. Note that for the mixture with 0.28% ferroparticles, this invariance could be observed at a very low field ~ 0.15T, this was the lowest field which could be obtained using the electromagnet used in the preparation system due to the remanent magnetisation of the iron pole pieces. To emphasise this remarkable observation, the alignment time is invariant with magnetic field from .15T to 2.1T. This is in marked contrast to the alignment times for the monodomains prepared from the polymer which show a strong dependence on the strength of the applied magnetic field, see

Figure 10.

The first proposal of mixing ferroparticles with liquid crystals was made by de Gennes and Brochard in a paper published in 1970 [

26] They suggested that there was both a magnetic field effect on liquid crystal alignment due to the anisotropic magnetic field surrounding even a spherical particle and a mechanical effect due to the elongated particle that they used. The invariant nature of the alignment time with the magnetic field in the current work suggests that there is indeed another alignment mechanism in place which is sufficiently strong to mask the inherent magnetic field effect due to the diamagnetic anisotropy of the mesogenic units.

Ferrofluids, essentially a suspension of magnetic particles in a carrier fluid, were first developed in the 1960s and subsequently developed for a wide variety of applications [

27,

28] ranging from rocket fluid [

28] through magnetic hyperthermia in medical physics [

29] and for fluid seals [

30]. Due to their size, nanoparticles are readily magnetized but usually have no magnetization when the applied magnetic field is removed. Consequently, they readily form dipolar chains of nanoparticles. Zubarev et al [

22] have developed a theoretical model which predicts the mean number of particles n in a chain due magneto-dipole inter-particle interaction as

Where φ is the solid fraction and λ is the dimensionless coupling coefficient which is a measure of the strength of the particle-particle interactions and determines the probability of aggregate formation due to magneto-dipole interactions. can be derived using Equation 6

Where M

d is the saturation moment of the bulk, V is the particle volume and 0 is the permeability of free space. To give an example, a 10nm magnetite particle at 298K with Md= 466kAm-1, n=1.36 so little chaining occurs, whereas for a 13nm particle n is infinite. In this situation λ~0.4 and it is the regime that long chains are formed A λ≥ 3 is required for spherical aggregates. At higher concentrations Dubois et al [

32] observed cellular like structure.

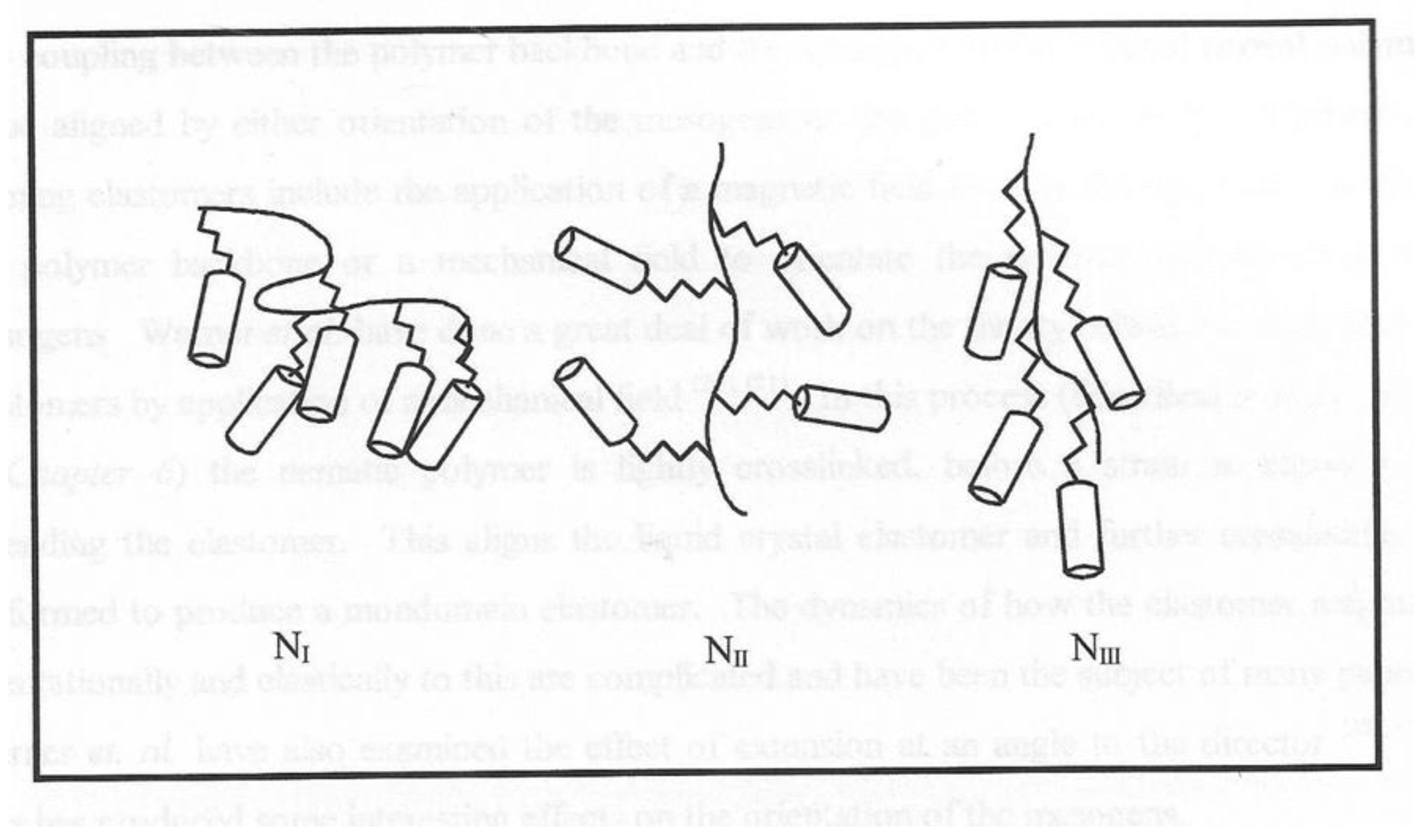

We can expect that these chains form parallel to the magnetic field present a series of internal surfaces in a similar manner to polymer stabilized liquid crystals [

33,

34]. Just as the interactions with any surface will affect the alignment of the nematic domains, we propose a simple model to explain the results in

Figure 14. In the absence of an external magnetic field, the ferroparticles are randomly arranged. Realistically it is difficult to place the sample in a zero magnetic field, due to the earth’s magnetic field of ~ 30T. Increasing the applied magnetic field to 0.15T is sufficient to align the chains of the nanoparticles, the response time will depend on a threshold magnetic field, the viscosity of the polymer and the number of internal surfaces. The latter gives rise to the composition dependence shown in

Figure 15.

Figure 14 shows the dependence of the maximum value of <P2> observed during the formation of the monodomain. Clearly all of the compositions in the first region of this plot are sufficient to drive the domain alignment towards a monodomain and we attribute this to the fact that these chains are organized in a parallel 2d manner. As the proportion of ferro particles increases, the morphology of the chains becomes more 3-D and starts to inhibit monodomain formation.

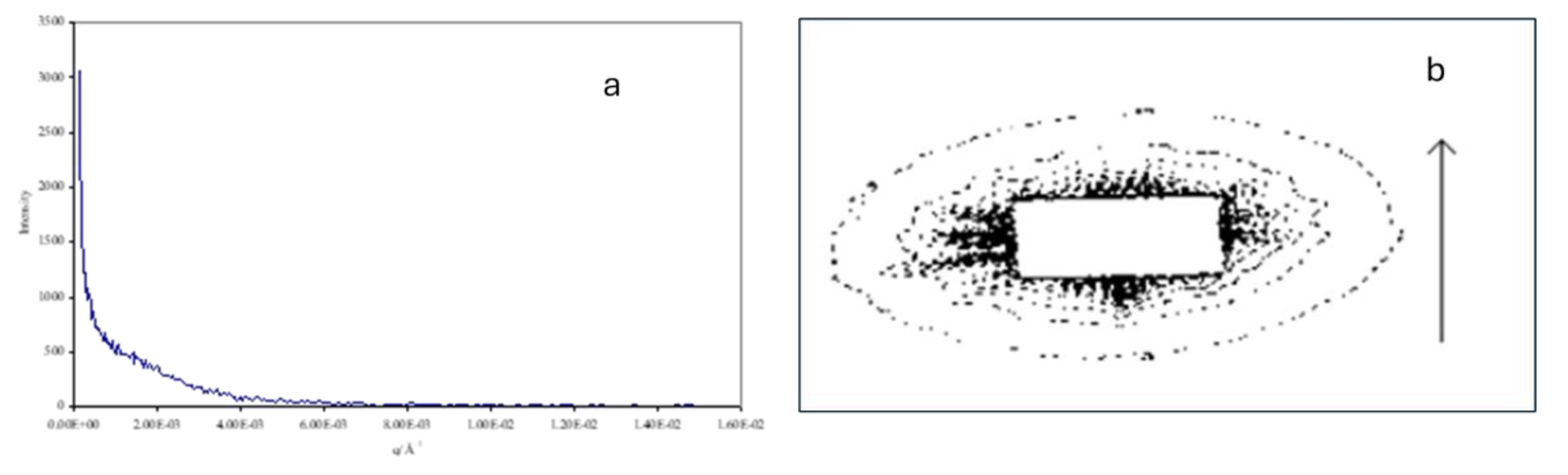

In order to explore if there is any additional evidence to support this chain model for the invariance of the monodomain formation time we used both laser and X-ray scattering to probe the appropriate samples. A dispersion of the ferroparticles in kerosene readily yields a highly anisotropic light scattering pattern between crossed polarizers lying normal to the applied magnetic field direction. The characteristics of the light scattering yielded objects 24 µm long and 5 µm. The external surface of a cross-linked sample of the polymer with 0.28% volume fraction of ferroparticles showed a rippled surface when examined in a scanning electron microscope which were µm wide. Although it is tempting to associate these with the chains of particles, the work of Zubarev et al [

22] predicts such a rippled surface as the ferroparticles are generate a surface according to the field lines.

Figure 20 shows that the 2D small-angle scattering pattern for the monodomain shows strong scattering clustered around the zero-angle point. Although much of the scattering is obscured by the beam stop, we can see that it shows some highly anisotropic scattering in which the scattering is high constrained in the vertical direction indicating some highly extended objects and spread out in the horizontal direction indicating that the extended objects are quite narrow in the horizontal direction. We attribute such features as arising from individual chains. The strength of scattering increases with increasing volume fraction of the ferro particles and an increasing level of anisotropy with increasing time in the magnetic field.

Tentative analysis of these features by fitting a gaussian peak to the observable data yields a width of the anisotropic object of 10 µm with length evaluation probably limited by the resolution of the setup but in excess of 100 µm.

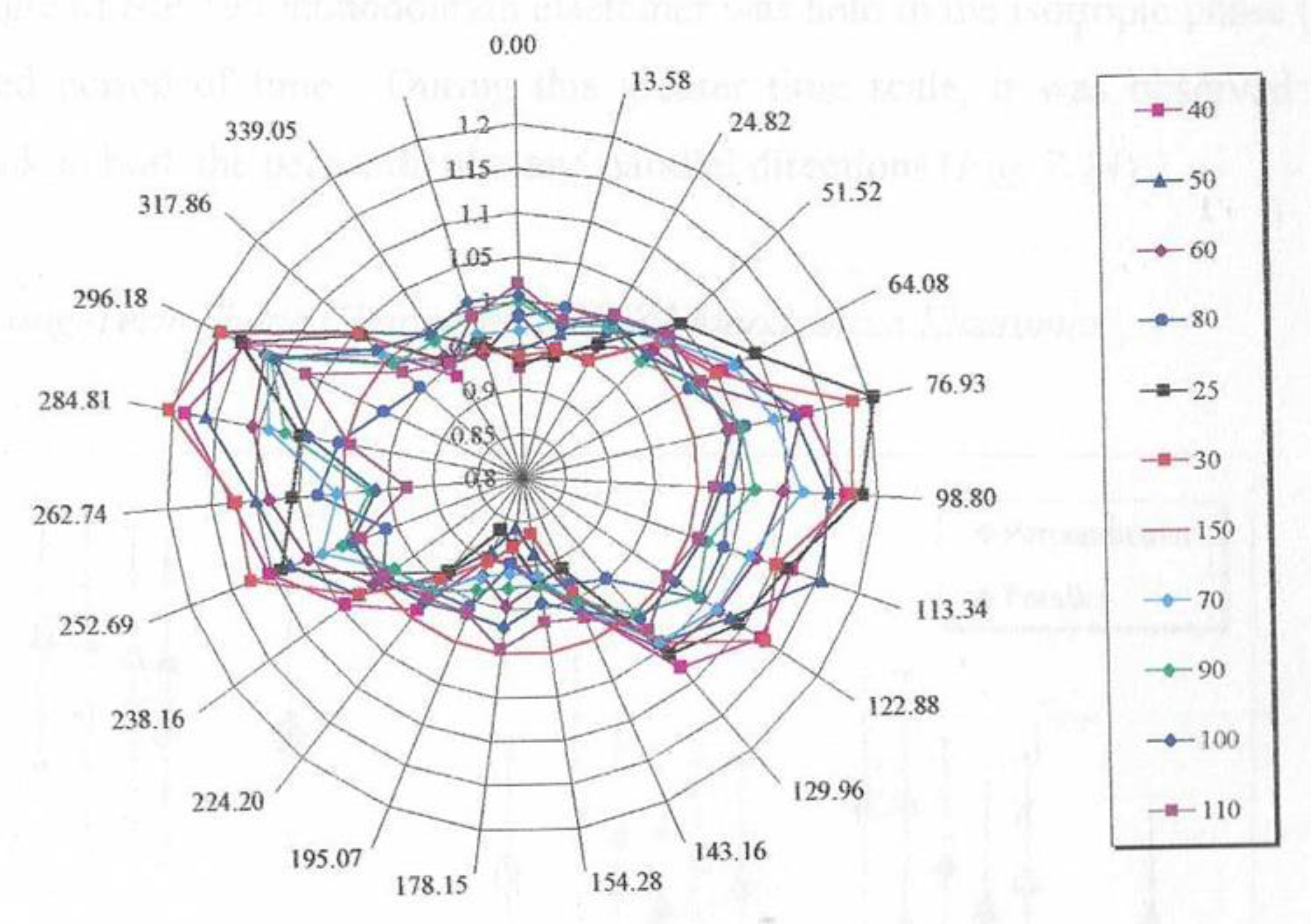

3.4. Director Rotation

In order to further understand the role of ferroparticles in the orientation of the liquid crystal polymer we conducted experiments to reorientate the aligned polymer systems. A 2.1 T magnetic field was applied at 90° to the director of an aligned ferronematic polymer (0.28 % volume fraction) and the change in mesogenic side group orientation was monitored using X-ray scattering and the three-circle diffractometer. The angle of side-group orientation gradually changed with time to correspond to the new magnetic field direction in approximately 30 minutes. This time appears to be independent of magnetic field strength at the fields investigated (0.8T – 2.1 T). It was also found that this reorientation resulted in a decrease in the order parameter as the mesogens rotated; this decrease is independent of field strength both in depth and time. The orientation level is recovered at the same time as the new angle of orientation is reached. This behaviour can be compared with the reorientation of CBZ6 without ferroparticles.

Figure 15 shows this system takes longer than the ferronematic polymer to reorganize (as with the initial monodomain formation}. The intermediate decrease in orientation is much larger and there is a discontinuity in the change in

The difference in behaviour can be seen more clearly by looking at the X-ray scattering azimuthal scans, showing intensity as a function of alpha, where alpha is the angle to the original director. For the non-ferronematic polymer

Figure 21 (a) shows a gap in the plots where the maximum orientation angle discontinuity occurs. In contrast for the ferronematic polymer

Figure 21 (b) shows a continuous array of plots where the orientation angle changes smoothly to the applied magnetic field direction.

The behaviour of the ferronematic polymer reorientation is different to that for the non-ferronematic polymer. The non-ferronematic polymer exhibits a discontinuity in the maximum orientation angle and a decrease in the level of orientation as the director rotation occurs. This suggests that the mesogens are first unaligned and then realigned in the new direction, whereas the ferronematic polymer has a continuous change in maximum orientational angle and only a small decrease in the level of orientation indicating that the mesogens rotate together to the new direction, this appears to a be a collective behaviour. This strikingly different behaviour lends itself to two potential explanations; the firstly one is that it is more energetically favourable for the ferroparticle chains to rotate to the new magnetic field direction, rather than dissolve and re-assemble; since they influence the mesogens, the director follows the same behaviour. However, as we have seen above the ferroparticle chains are particularly unstable and lose their alignment relatively easily, even without the additional influence of a change in magnetic field direction. An alternative explanation is that for the materials aligned in the presence of the ferroparticles, it is a general realignment of the polymer backbone which is occurring, in this case loss of local mesogen alignment is energetically unfavourable, since it will require a greater distortion of the elastic network. This arises because the polymer backbone was originally better aligned with the ferroparticles and the backbone as a whole reorientates.

The difference in behaviour can be seen more clearly by looking at the X-ray scattering azimuthal scans, showing intensity as a function of alpha, where alpha is the angle to the original director. For the non-ferronematic polymer

Figure 21 (a) shows a gap in the plots where the maximum orientation angle discontinuity occurs. In contrast for the ferronematic polymer

Figure 21 (b) shows a continuous array of plots where the orientation angle changes smoothly to the applied magnetic field direction.

Figure 22 shows the shape change for an initially circular sample which was cut from a monodomain sample held in the isotropic phase. We have measured the dimensions of the sample at specific angular positions, a process easily achieved with digital imaging as the sample temperature was varied. This approach also compensates for any error in aligning the sample with respect to the original magnetic field direction. As

Figure 22 shows the maximum changes is observed at an angle slightly titled from the horizontal. This measurement was performed with the chemically same polymer but with a lower molecular weight of Mw = 31,000 and Mn = 19,500.