1. Introduction

Autonomous vehicles precisely predict the trajectories of other traffic participants in the next few seconds to enable safe decision-making, whereas it is challenging to precisely predict the trajectories of agents in complex traffic dynamics scenarios. In recent years, learning-based approaches have been widely used for trajectory prediction [

1,

2,

3,

4], where a large number of solutions have emerged based on Transformer [

5], which has had successful applications in Natural Language Processing (NLP) and computer vision, among others [

6,

7,

8,

9], and is considered to be the most successful solution for extracting the serial correlation.

Trajectory prediction is essentially a time series prediction task, and Transformer-based time series analysis solutions have produced several well-known models for time series prediction, such as Informer [

10], FEDformer [

11], and Autoformer [

12]. However, in time series modeling, while the Transformer uses positional encoding techniques to retain some ordered information, the inherent alignment-invariant of the self-attention mechanism inevitably leads to the loss of temporal information [

13]. The alignment-invariant of the self-attention mechanism refers to its irrelevance to the order of the input sequence. Specifically, during the calculation of attention scores, the dot-product operations between the queries (Q), keys (K), and values (V) only consider the similarity between vectors without taking into account their positions in the sequence. As a result, even if the order of the input sequence changes, the outcome of the dot-product operation remains essentially unchanged. Additionally, the self-attention mechanism applies global weighted averaging to all input elements, disregarding their positions and only performing weighted summation based on the calculated attention scores. This means that the output vectors do not retain the positional information of the input elements, making the entire process fundamentally independent of the input sequence order.

For NLP, the semantics of the overall sentence is preserved to a large extent, even if some of the words are reordered. However, trajectory prediction requires learning temporal changes of successive points, and order plays the most crucial role. Meanwhile, recent studies have emphasized that information about independence and correlation among multiple variables in time series prediction impacts the prediction results [

14,

15]. As a result, the performance of Transformers in long-term time series forecasting (LTSF) has been questioned. Researchers found that the linear layer outperforms the complex Transformer in both performance and efficiency in the task of long-term time series forecasting [

13,

16].

Trajectory prediction is technically not a simple LTSF task; LTSF is applicable to time series that have relatively significant trend and periodicity, such as weather, traffic flow, energy, economic, and disease forecasts, and their prediction scales are typically measured in hours. In addition, researchers have pointed out that combining linear layers with attention as well as other components leads to performance degradation [

13], and the effectiveness of using linear layers for prediction is related to the size of the look-back window (historical series), with the larger the look-back window (96-720), the better the performance of the linear layer. For trajectory prediction, the argoverse [

17] dataset, for instance, has a lookback window of only 20.

Through experiments, we found that a simple linear layer is not capable of the trajectory prediction task. Trajectory prediction generally requires predicting precise trajectories for several seconds in the future and faces more complex challenges because the trajectories of agents on the road are affected by interactions between agents and traffic rules, and their potential future trajectory choices are diverse. Although self-attention loses temporal information due to the inherent alignment invariance, the ability of self-attention to extract serial dependencies is still worthy of attention. We believe that while the linear layers cannot be directly integrated with self-attention components, they can operate in parallel with components like self-attention to extract features from trajectory series and then perform feature fusion. This approach can preserve the order of the sequence inputs, thereby compensating for the Transformer’s limitations in extracting temporal information.

Therefore, we explored the effective application of linear layers in the field of trajectory prediction and proposed a flexible trajectory prediction framework by combining the sparse self-attention to extract multivariate correlations and dependencies in the series. The effectiveness of the linear prediction scheme and the sparse self-attention mechanism in trajectory prediction is experimentally verified.

In summary, the contributions of our work include:

To the best of our knowledge, our work is the first to introduce the ability to extract temporal information from linear layers to trajectory prediction. It uses linear layers to process sequence features in parallel with self-attention, extracts the temporal information with a simple linear layer, maintains multivariate independence. This approach solves the issue of temporal information loss in Transformer-based trajectory prediction schemes caused by self-attention and verifies the effectiveness of using linear layers to extract temporal information in trajectory prediction.

The sparse self-attention mechanism is applied to trajectory prediction, in our work, the multivariate correlation information is considered. On the one hand, the sparse self-attention mechanism extracts dependency relationships among the trajectory sequences. On the other hand, it captures the multivariate correlation information, aiming to achieve accurate predictions.

We conducted a series of empirical studies on the designed trajectory prediction scheme, exploring the effects of using linear layers to extract temporal information, the sparse self-attention mechanism to extract trajectory sequence dependencies and variable correlations, and positional encoding in Transformer on the effectiveness of trajectory prediction. Our work will benefit future research in this area.

2. Related Work

Transformer-based solutions have achieved unparalleled functionality in NLP and computer vision tasks due to the effectiveness of the multiple self-attention mechanisms, and their ability to capture long-term dependencies has given rise to the rapid development of Transformer-based trajectory serial modeling schemes.

Recent studies have begun to emphasize the impact of independence between multivariables in time series forecasting [

14,

15,

16], and some researchers have questioned the effectiveness of Transformer. Transformer-based forecasting architectures typically embed multiple variables at the same timestamp into indistinguishable channels, causing multivariables to lose their independence. In addition, the time series variation is strongly correlated with the order. However, the Transformer employs the alignment-invariant self-attention in the time dimension, and the self-attention mechanism has quadratic time complexity and high memory loss. These factors make the Transformer limited in time series forecasting tasks.

The iTransformer [

16] centers on variables and embeds the entire time series of each variable independently into tokens, with the self-attention capturing multivariate correlations while applying a feed-forward network to each variable token to learn a nonlinear representation. Informer [

10] proposes the sparse self-attention mechanism, which reduces the complexity of the Transformer’s self-attention mechanism. The LTSF-Linear [

13] uses only the linear layer for time series prediction and achieves higher performance than the Transformer and its variants. It also finds that combining the linear layer with other components, such as the attention component, leads to performance degradation.

High-precision maps are also crucial in trajectory prediction [

18]. Map representations help in accurate trajectory prediction, and most of the current trajectory prediction models use map representations [

2,

17,

18,

19,

20], where VectorNet extracts the feature representations of the agents and lanes respectively using two graph convolutions [

21], LaneGCN [

20] obtains sparsely connected lane graphs from map topological connections and uses polylines as node representations to obtain high resolution.

3. Attention-Linear Trajectory Prediction

We propose the Attention-Linear Trajectory Prediction architecture, which uses self-attention to extract dependencies and correlations of variables in the trajectory series, the linear layer to extract the temporal information of the trajectory series, and a prediction component to decode the multivariate channels independently for direct forward prediction of the trajectory series. At the same time, in order to intuitively explore the potential of different forms of self-attention in trajectory prediction and the ability of the linear layer to model temporal information in the trajectory series, we constructed the network using the basic components.

3.1. Problem Formulation

We formulate the trajectory prediction problem as predicting the future position coordinates of the target vehicle based on the observed historical motion information of the agents, i.e., the target vehicle and its surrounding traffic participants. Formally, trajectory prediction is based on the past time steps ,predicting the future positions for time steps. Here, represents the information of N+1 agents at time t, where N+1 denotes the target vehicle and the N surrounding traffic participants.We represent the geometric properties of the agents’ trajectory using relative positions, transforming the trajectory data into vector information. Therefore, in the model, , where P represents the two-dimensional coordinates (x, y) of agent i at a certain time. At this point, X is denoted as , and , which represents the predicted trajectory coordinates of the target vehicle at time t. Thus, Y represents the of the target vehicle.

3.2. Overview of the structure

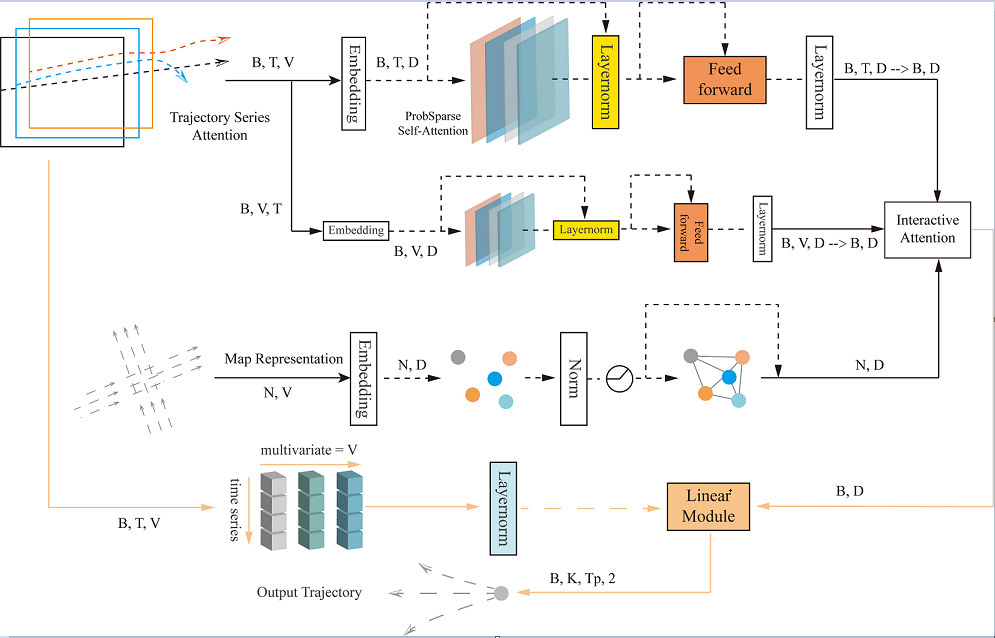

As shown in

Figure 1, the Attention-Linear trajectory prediction architecture uses the trajectory series attention module to extract the features and dependencies of the trajectory sequences, as well as the interaction information between the variables. The input to the trajectory series attention module is of shape (B, T, V), and the output is (B, T, D), where B represents the number of agents in each batch, T represents the time steps, and V represents the trajectory variables. The model uses the last time step of the historical features, which is the initial time step for prediction, as the input (B, D) to the feature interaction attention module. This module extracts interaction information between the agents and the local traffic environment. The map representation module extracts structured map features, with input (N, V), where N represents the number of lane nodes, and V here represents the map input variables. The linear module utilizes linear layers to extract features from trajectory sequences in a channel-wise manner and aggregates features from the above modules. Finally, it outputs the predicted trajectory sequence of shape (B, K, Tp, 2), where K represents the K multimodal trajectories output, Tp represents the prediction timestep, and 2 represents the x and y coordinates of the trajectory.

3.3. Attention-Linear Components

3.3.1. Trajectory Series Attention

First, we extract the trajectory information of the agents from the scene data, use the relative position to represent the geometrical attributes of the agents trajectory, and when the length of the agents’ trajectory sequence is less than the historical time step, fill it with the value 0 and mark the filled elements with a mask. The trajectory series attention module uses variables at the same moment as token in extracting dependencies between sequences and uses linear layers to transform the variables to a higher dimensional space, and then models the temporal dependencies using the sparse self-attention mechanism [

10] with the following formulas:

where the input

to the self-attention layer is obtained by the embedding, i.e., linear projection, after which

is multiplied by the corresponding weight matrix

to generate the queries (

), keys (

), and values (

). In the sparse self-attention mechanism, the input

is a sparse matrix that only contains the top- u queries selected based on a sparsity metric. The sparsity metric formula is as follows:

denotes the ith query,

represents the set of key vectors,

is the total number of key vectors,

d represents the dimension of q and k vectors, and the dot product divided by the scaling factor

prevents the gradient from vanishing or exploding. The sparsity metric distinguishes between major and minor dot products to generate different sparse query key pairs for each attention head, which reduces the time complexity and avoids serious information loss. In addition, residual connectivity [

22] is used in the self-attention part to improve the speed and effectiveness of network training, and Layernorm [

23] is used to improve the convergence and training stability of the deep network, and the feed-forward network follows the Transformer’s linear connection.

In order to extract correlation information between variables, the trajectory series attention module uses the same components and inverts embedding, where the overall time series of the same variable is used independently as a token, and instead of modeling the temporal information of the series, self-attention is used to extract the interactions between independent variables. Meanwhile, layer normalization is used for the representation of individual variables, and normalizing variables to a Gaussian distribution reduces the discrepancy caused by inconsistent measurement scales.

3.3.2. Map Representation

The map representation provides geometric and semantic information for trajectory prediction. The input lane-level map is first represented as a set of vectorized data, including lane centerlines and connectivity properties between lanes. We denote lane nodes by r. The lane node is represented as the centerline of each lane in the vectorized data of the map, and N represents the total number of lane nodes in the map. There are four kinds of connectivity characteristics of lane nodes, namely, predecessor, successor, left neighbor, and right neighbor, and the corresponding adjacency matrix is constructed from them, where is an matrix, e.g., if node i is the right neighbor of j, the jth column of the ith row of is 1, otherwise it is 0.

Trajectory prediction generally uses the graph convolution operator [20] to process the map information, i.e., graph convolution is used to process the input features of lane nodes and adjacency matrix. Firstly, feature

of the lane nodes is:

where

denotes the start-to-finish vector of the lane nodes, which represents the geometry features of the lane nodes, and

denotes the centroid location features of the lane nodes, and then

is converted to a high-dimensional feature matrix by MLP.

The adjacency matrix represents the connectivity information of the lanes, and the lane node features, together with the adjacency matrix features, constitutes the basic elements of the graph convolution operator, and the multi-scale graph convolution can capture the map information in a larger horizon, which is calculated as follows:

where

denotes the corresponding weight matrix, which participates in the graph convolution operation with the adjacency matrix

and the lane node features matrix

in training and continuously updates its parameters, k represents the multiscale factor, which enables graph convolution of the lane connection features in different perception domains. In addition, residual connections are introduced in the part of graph convolution to improve the speed and effectiveness of network training.

3.3.3. Interactive Attention

Interactive attention is based on spatial distance information, and its main goal is to capture spatial interactions in a traffic scenario. Its scenario embedding inputs are concatenated based on distance queries to road features near the agents as well as other traffic participants. Notably, in contrast to many previous approaches, Attention-Linear avoids using trajectory series features between agents as interactions and instead uses variable features along with sequence features as the target for encoding information about agents’ interactions.

3.3.4. Linear Module

The linear layer itself does not directly capture temporal information but extracts features by applying the same linear transformation to each time step t across different variable sequences. Its advantages lie in weight sharing, simple and effective feature extraction, and the ability to integrate with other related structures. Time series often exhibit certain patterns and regularities, and weight sharing can better capture these patterns, thus playing a crucial role in time series data processing tasks. Additionally, the introduction of the LTSF-Linear [

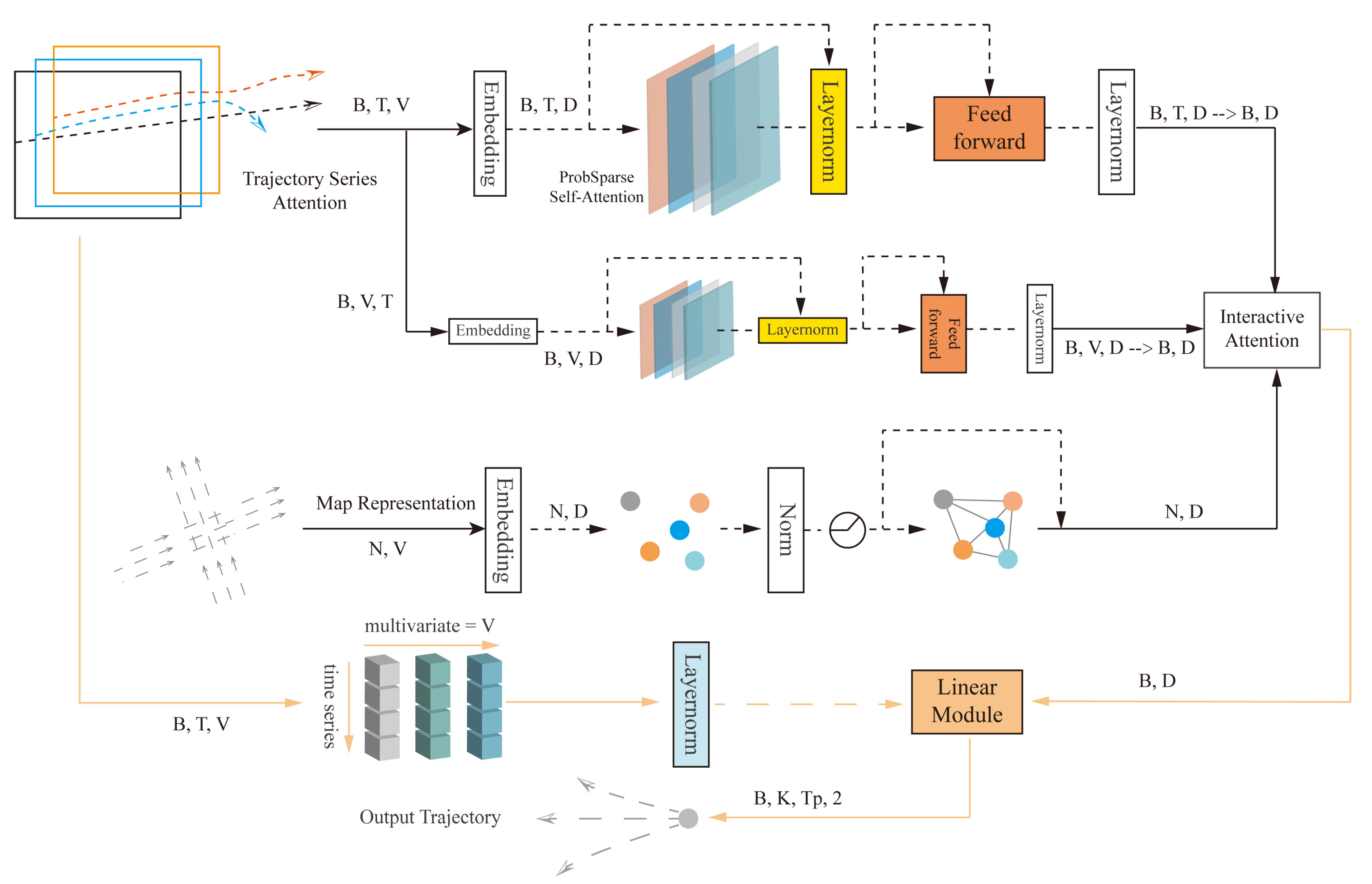

13] model provides valuable insights into our understanding of time series representation. As shown in

Figure 2, we designed a linear layer to learn the temporal information representation of the trajectory sequence.

We first perform layer normalization on the entire sequence of variables, followed by independent linear transformations on the entire sequence for each variable, allowing each variable to learn specific feature representations. Within the sequence of the same variable, the linear layer can utilize shared weights across the time dimension. Additionally, since the time steps are processed independently, the feature representations at each time step maintain consistency. Compared to time-step-specific feature transformations like the self-attention mechanism, this approach can extract stable global features from the sequence. The calculation formula is as follows:

where

is the linear layer along the time axis, and

as well as

represent the linear transformation feature and input of the ith variable.

contains the temporal order of the trajectory sequence. To facilitate efficient learning, common deep learning techniques residual connections are used. Finally, the features from the interaction attention mechanism are aggregated through simple summation.

In the prediction phase, direct forward prediction is performed, where the sequence dimension is converted to the length of the future prediction sequence through the linear layer. The same linear transformation is applied to each channel. At this point, the weight of the linear layer are shared across all variables, ensuring that the highly correlated output time series of variables x, y are mapped in the same manner. The prediction module consists of K-stacked linear prediction layers. For each traffic participant, K possible future trajectories can be predicted. The linear layer is also directly applied in the prediction section to map the input features to a one-dimensional space as a classification confidence score to predict the prediction closest to the true value among the K trajectories.

3.4. Training

In the trajectory prediction training phase, we train the whole model end-to-end. For the trajectory prediction task, the loss function

L consists of two terms: the trajectory regression loss

and the classification loss

, defined as shown in Equation

9–

11:

where the trajectory regression loss is the smooth

loss, where i and j both range from 1 to K.

and

represent the predicted trajectory and the confidence probability, respectively. m is the maximum margin value. The classification loss begins to accumulate when the probability of the trajectory that is closest to the ground truth is not higher than the probabilities of other trajectories by at least the margin value m; otherwise, the classification loss is zero. j is the index of the trajectory with the lowest average displacement error (ADE) closest to the ground truth trajectory

:

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Settings

Dataset. The effectiveness of our method is validated on the Argoverse dataset, a large-scale dataset from real-world sources widely used in the field of trajectory prediction, covering 324,557 diverse traffic scenarios in the Pittsburgh and Miami regions of the U.S. The trajectories of each scenario are recorded via sequential frames sampled at 10Hz. Each scenario focuses on a specific agent object and includes the historical trajectories of all traffic participants over 2 seconds and the true future trajectories for the next 3 seconds. This dataset provides a reliable empirical basis for motion prediction studies in complex real-world environments.

Metrics. We computed the most widely used evaluation metrics in the field of trajectory prediction:

min: The average distance between the best trajectory among k predictions and the ground truth trajectory across all timesteps.

min: The distance between the endpoint of the best trajectory among k predictions and the ground truth endpoint position.

: The proportion of predictions where the distance between the predicted endpoint and the ground truth endpoint exceeds the 2-meter threshold.

The best trajectory among k predictions refers to the trajectory whose position is closest to the ground truth. The performance is evaluated using the results when k=6 and k=1 as performance metrics.

Training. We trained the model on 205,942 scenarios of the training set using an RTX3090. The training was conducted for 8 epochs at a learning rate of , then the learning rate was reduced to and continued up to 36 epochs with a batch size of 32 and using the Adam optimizer.

4.2. Experimental Results

Comparison with Different Methods: We compared the Attention-Linear model with several baseline methods and some state-of-the-art approaches on the Argoverse [

17] test set. The results for K=1 are reported in

Table 1. The baseline methods include the constant velocity baseline [

17], nearest neighbor retrieval NN+map [

17], Social-LSTM encoder-decoder model LSTM ED+Social [

17], goal-driven multimodal trajectory prediction TNT framework [

25], a novel vehicle motion prediction method based on multi-head attention Jean [

26], attention-based method using recurrent graphs WIMP [

27], hierarchical graph neural network VectorNet [

28], a method combining graph convolution with multi-head self-attention CRAT-Pred [

29], and SceneTransformer [

30], which uses a masking strategy as model queries. It can be observed that the Attention-Linear model achieves lower minADE and minFDE than the aforementioned methods when K=1.

Importance of each module: We analyzed the overall architecture of the Attention-Linear model, studied the function of each module separately, and analyzed its impact on the model’s functionality by reducing specific modules to record the corresponding experimental effects. The corresponding results are recorded in

Table 2. Where TSA denotes the part of the Trajectory Series Self Attention module that extracts series features, iTSA denotes the part of the Trajectory Series Self Attention module that extracts correlations between variables, Map represents the Map Representation module, and LinearM denotes the Linear module.

The results in the table indicate that each module of Attention-Linear has improved the model performance, which shows the effectiveness of the overall architecture. Moreover, LinearM can improve the model performance by 18.91%, 25.14%, and 39.15% under the three evaluation metrics of k=6. The prediction performance of the model can reach the best when combining the advantages of the self-attention mechanism and the linear layer to extract the trajectory series features in parallel. Secondly, the experimental results show that using trajectory series self-attention to extract correlation features between series variables has a certain degree of influence on trajectory prediction.

Importance of particular components in the module: In order to further verify the improvement of LinearM on the ability of Transformer to extract temporal information, we add positional encoding to the embedding part of TSA as a comparison. At the same time, we do the effectiveness analysis of the sparse self-attention and change it to the normal self-attention for the comparison experiments. The corresponding results are recorded in

Table 3.

From the experimental results, we can see that the effect of sparse self-attention is better than that of normal self-attention, the combination of LinearM and self-attention is better than the combination of Positional encoding and self-attention, and there is a significant improvement in the effect when LinearM is added to the combination of Positional encoding and self-attention, indicating that LinearM can effectively extract the temporal information to improve the performance of the overall model. Although Positional encoding can encode the temporal information of the trajectory series, the temporal information will be lost due to the influence of the self-attention mechanism. LinearM can effectively solve this problem.

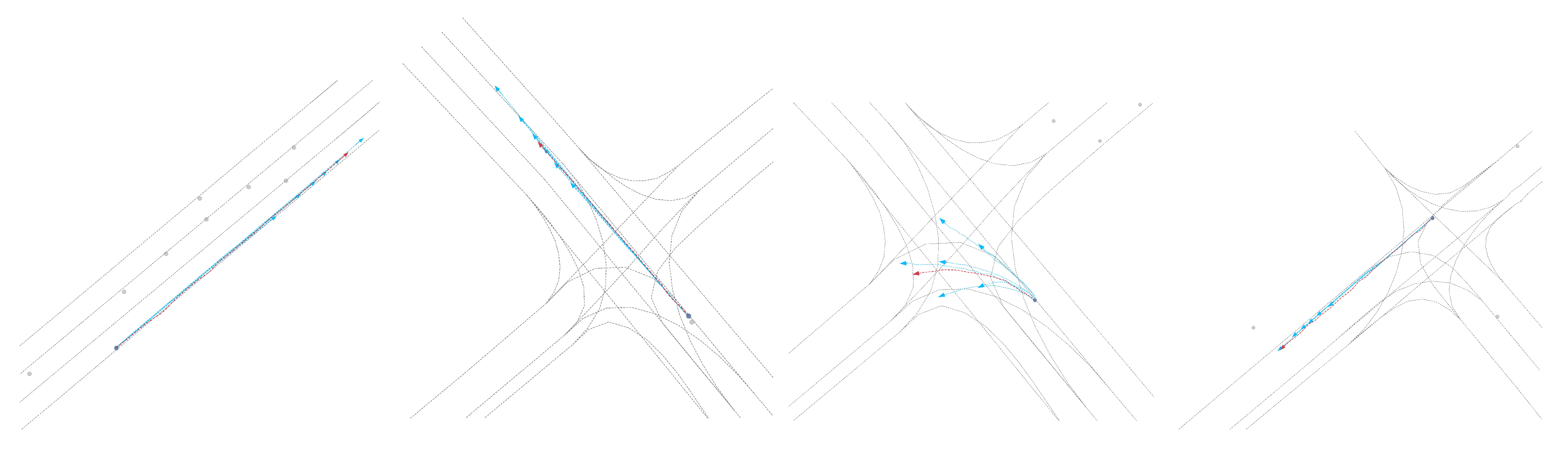

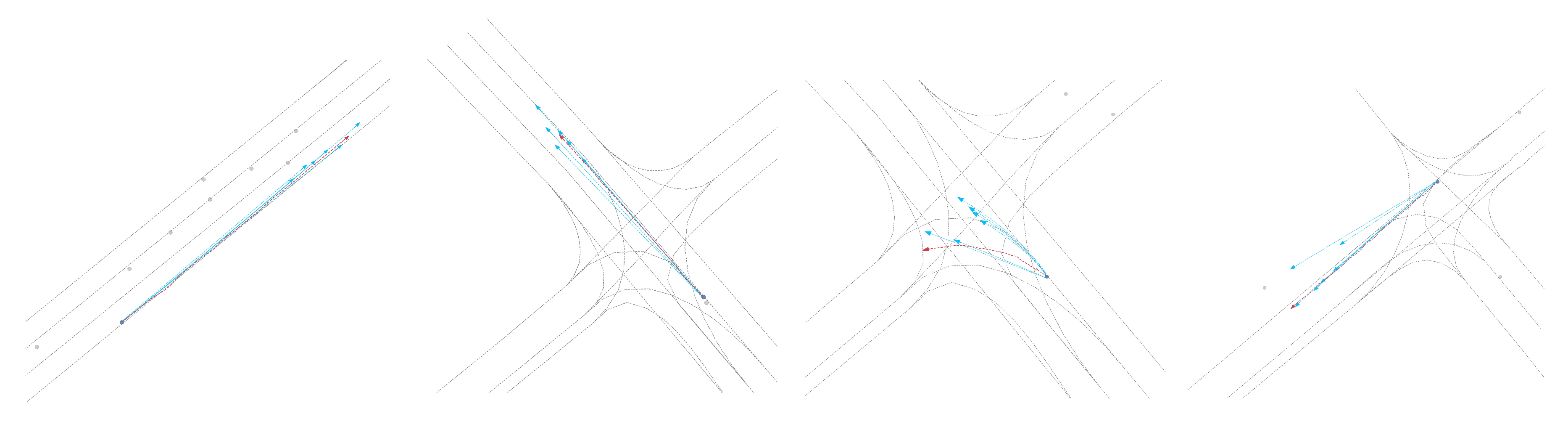

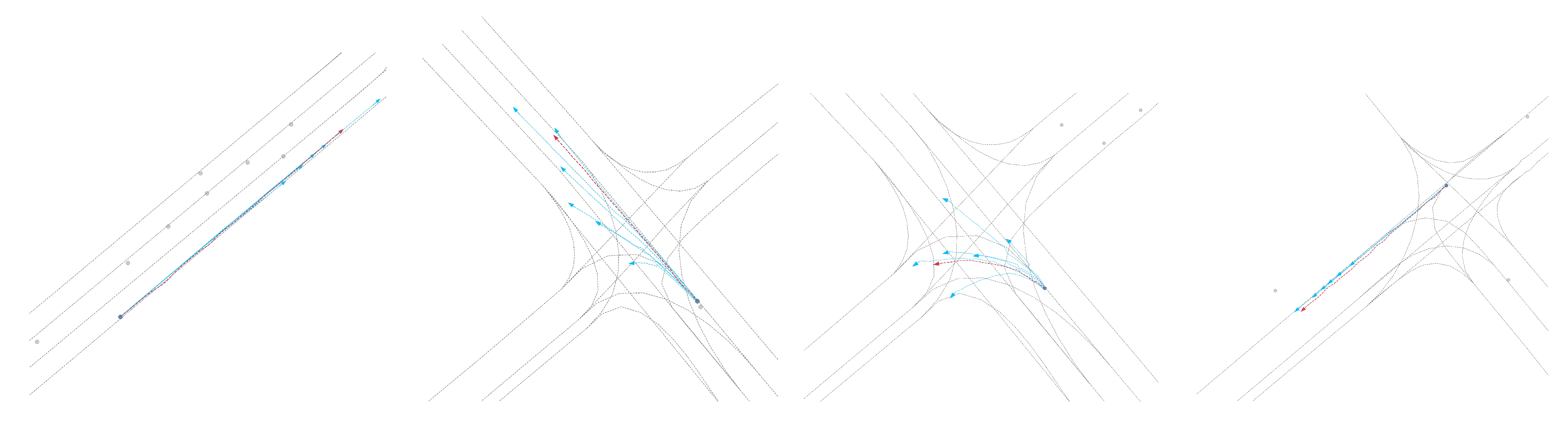

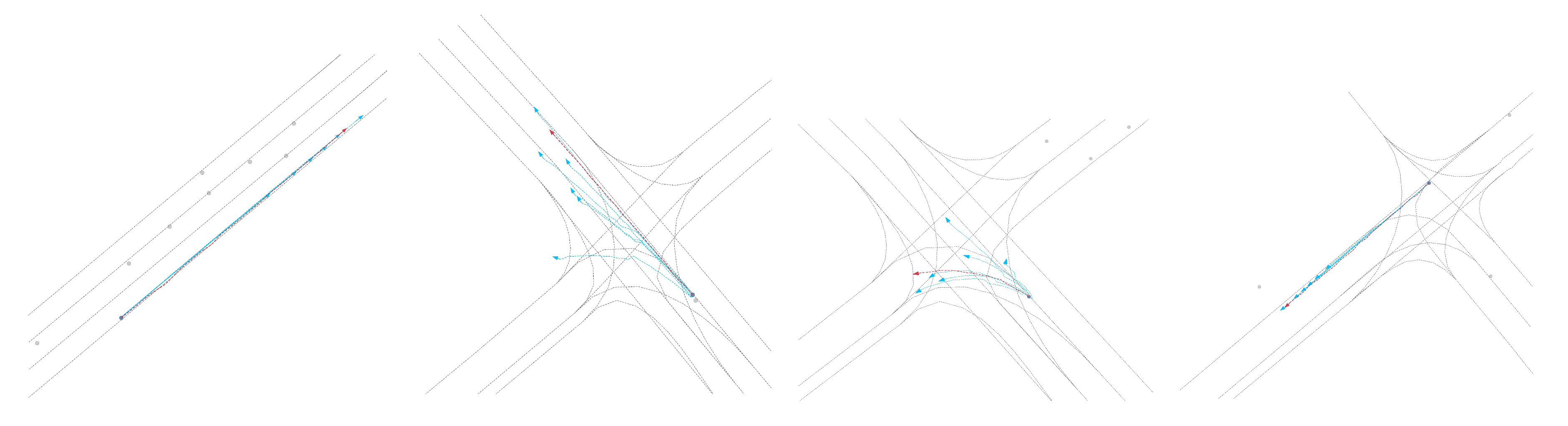

Qualitative results: As shown in

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, we present the qualitative results of the Attention-Linear model on the Argoverse validation set. It is evident that the Attention-Linear model can accurately predict agents’ behavior in complex traffic interaction scenarios with a multimodal approach. For clarity, we visualized the centerlines of lanes (gray lines), the true trajectory of one agent (red line), the predicted trajectory (light blue line), and the real positions of other traffic participants at the final moment (gray dots) in each scenario.

5. Conclusion

We question the effectiveness of Transformer in trajectory prediction. For the first time, we introduce the ability of the linear layer to extract series information into trajectory prediction by using linear layers with sparse self-attention to process series features in parallel and then fusing the features in separate channels to ensure the independence of the variables. Empirical studies demonstrate that our strategy of parallel feature extraction using linear layers and self-attention can improve the performance of Transformers in trajectory prediction and verify the effectiveness of sparse self-attention in extracting trajectory series dependencies and variable correlations in trajectory prediction.

Funding

This research was funded by Jilin Provincial Office of Science and Technology grant number 20220301012GX.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Z. Zhou, L. Ye, J. Wang, K. Wu, and K. Lu, "HIVT: Hierarchical Vector Transformer for Multi-Agent Motion Prediction," in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Mercat, T. Gilles, N. El Zoghby, G. Sandou, D. Beauvois, and G. P. Gil, "Multi-Head Attention for Multi-Modal Joint Vehicle Motion Forecasting," in 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), pp. 9638-9644, IEEE, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Yu, X. Ma, J. Ren, H. Zhao, and S. Yi, "Spatio-Temporal Graph Transformer Networks for Pedestrian Trajectory Prediction," in Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Nayakanti, R. Al-Rfou, A. Zhou, K. Goel, K. S. Refaat, and B. Sapp, "Wayformer: Motion forecasting via simple & efficient attention networks," in 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), pp. 2980-2987, IEEE, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Vaswani, N. Shazeer, N. Parmar, J. Uszkoreit, L. Jones, A. N. Gomez, L. Kaiser, and I. Polosukhin, "Attention Is All You Need," in Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2017.

- J. Devlin, M.-W. Chang, K. Lee, and K. Toutanova, "BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding," arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805, 2018.

- Z. Liu, Y. Lin, Y. Cao, H. Hu, Y. Wei, Z. Zhang, S. Lin, and B. Guo, "Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer Using Shifted Windows," in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 10012-10022, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Dong, S. Xu, and B. Xu, "Speech-Transformer: A No-Recurrence Sequence-to-Sequence Model for Speech Recognition," in 2018 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), pp. 5884-5888, IEEE, 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. Brown et al., "Language Models Are Few-Shot Learners," in Proceedings of the 34th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2020.

- H. Zhou, S. Zhang, J. Peng, S. Zhang, J. Li, H. Xiong, and W. Zhang, "Informer: Beyond Efficient Transformer for Long Sequence Time-Series Forecasting," in Proceedings of the Thirty-Fifth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI 2021), Virtual Conference, vol. 35, pp. 11106-11115, AAAI Press, 2021.

- T. Zhou, Z. Ma, Q. Wen, X. Wang, L. Sun, and R. Jin, "FEDformer: Frequency Enhanced Decomposed Transformer for Long-Term Series Forecasting," in Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2022.

- H. Wu, J. Xu, J. Wang, and M. Long, "Autoformer: Decomposition transformers with auto-correlation for long-term series forecasting," Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 34, pp. 22419-22430, 2021.

- A. Zeng, M. Chen, L. Zhang, and Q. Xu, "Are Transformers Effective for Time Series Forecasting?," in Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 37, no. 9, pp. 11121-11128, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang and J. Yan, "Crossformer: Transformer Utilizing Cross-Dimension Dependency for Multivariate Time Series Forecasting," in Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2023.

- V. Ekambaram, A. Jati, N. Nguyen, P. Sinthong, and J. Kalagnanam, "Tsmixer: Lightweight MLP-Mixer Model for Multivariate Time Series Forecasting," in Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD), 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, T. Hu, H. Zhang, H. Wu, S. Wang, L. Ma, and M. Long, "iTransformer: Inverted Transformers are Effective for Time Series Forecasting," arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.06625, 2023.

- M. F. Chang, J. Lambert, P. Sangkloy, J. Singh, S. Bak, A. Hartnett, D. Wang, P. Carr, S. Lucey, D. Ramanan, and J. Hays, "Argoverse: 3D Tracking and Forecasting with Rich Maps," in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 8748-8757, 2019.

- B. Wilson, W. Qi, T. Agarwal, J. Lambert, J. Singh, S. Khandelwal, B. Pan, R. Kumar, A. Hartnett, J. K. Pontes, and D. Ramanan, "Argoverse 2: Next Generation Datasets for Self-Driving Perception and Forecasting," arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.00493, 2023.

- J. Gao, C. Sun, H. Zhao, Y. Shen, D. Anguelov, C. Li, and C. Schmid, "VectorNet: Encoding HD Maps and Agent Dynamics from Vectorized Representation," in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 11525-11533, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Liang, B. Yang, R. Hu, Y. Chen, R. Liao, S. Feng, and R. Urtasun, "Learning Lane Graph Representations for Motion Forecasting," in Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. N. Kipf and M. Welling, "Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks," arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.02907, 2016.

- K. He, X. Zhang, S. Ren, and J. Sun, "Deep residual learning for image recognition," in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2016, pp. 770-778. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Ba, J. R. Kiros, and G. E. Hinton, "Layer normalization," arXiv preprint arXiv:1607.06450, 2016.

- K. Hornik, "Approximation capabilities of multilayer feedforward networks," Neural Networks, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 251–257, 1991. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhao, J. Gao, T. Lan, C. Sun, B. Sapp, B. Varadarajan, Y. Shen, Y. Shen, Y. Chai, C. Schmid, and C. Li, "TNT: Target-driven trajectory prediction," in Conf. Robot Learn., Oct. 2021, pp. 895-904, PMLR.

- J. Mercat, T. Gilles, N. El Zoghby, G. Sandou, D. Beauvois, and G. P. Gil, "Multi-head attention for multi-modal joint vehicle motion forecasting," in 2020 IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Autom. (ICRA), May 2020, pp. 9638-9644, IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Khandelwal, S., Qi, W., Singh, J., Hartnett, A. and Ramanan, D., 2020. What-if motion prediction for autonomous driving. arXiv preprint arXiv:2008.10587.

- J. Gao, C. Sun, H. Zhao, Y. Shen, D. Anguelov, C. Li, and C. Schmid, "VectorNet: Encoding HD maps and agent dynamics from vectorized representation," in Proc. IEEE/CVF Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit., 2020, pp. 11525-11533.

- J. Schmidt, J. Jordan, F. Gritschneder, and K. Dietmayer, "CRAT-Pred: Vehicle trajectory prediction with crystal graph convolutional neural networks and multi-head self-attention," in 2022 Int. Conf. Robot. Autom. (ICRA), May 2022, pp. 7799-7805, IEEE.

- J. Ngiam, B. Caine, V. Vasudevan, Z. Zhang, H. T. L. Chiang, J. Ling, R. Roelofs, A. Bewley, C. Liu, A. Venugopal, and D. Weiss, "Scene Transformer: A unified architecture for predicting multiple agent trajectories," arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.08417, 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).