Submitted:

23 August 2024

Posted:

26 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Commonly Studied 1H MRS metabolites in AD

2.1. NAA

2.2. mIns

| Authors | Cohort | Magnet field strength and acquisition parameters | Voxel locations and size | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [48] | CU (n=30) | 7T, TR=644, MRSI, FIDLOVS | Posterior cingulate gyrus and precuneus | ↑ GABA and ↑ Glu were associated ↑ Aβ burden on PET (PiB) with a positive effect modification by APOE e4 allele. |

| [49] | AD (11), MCI (8), CU (n=26) |

3T, TR/TE=2000/30 ms, MRSI, PRESS | Posterior cingulate gyrus, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

↓Glu/tCr was associated with ↑ tau load on PET with florzolatau in the posterior cingulate gyrus of AD dementia patients. ↑ plasma NfL was associated with MRS metabolites (↓ tNAA/tCr and ↓ Glu/tCr) in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of patients with AD dementia. |

| [50] | CU (Aβ – and Aβ+) (n=338), MCI (Aβ+)(n=90) | 3T, TR/TE=2000/30 ms, single voxel, PRESS | Posterior cingulate cortex /precuneus region | ↑ mIns/tCr ratio in the posterior cingulate gyrus was associated with ↑ posterior cingulate gyrus and neuocortical meta-ROI Aβ (flutemetamol) and tau (RO948) load on PET only in APOE e4 allele carriers. ↑ plasma GFAP was associated with ↑ mIns/tCr (posterior cingulate gyrus) only in APOE e4 allele carriers. |

| [51] | CU women: CSF Aβ negative (n=71); CU Aβ positive women (n=37); MCI (CSF Aβ positive) women (n=12) |

3T, TR/TE=2000/20 ms; TR/TE=2000/68 ms/; single voxel; PRESS and MEGA-PRESS | Medial frontal cortex | ↑ Glx, ↓ GABA, and ↑ mIns/tCr ratio in MCI compared to CU CSF Aβ42 negative and positive participants. ↑ Age was associated with ↓ levels of GABA in CU and MCI groups. |

| [52] | CU (A−T−N−) (37); early AD (A+T+N−) (n=16); late AD (A+T+N+)(n=15)a | 3T, TR/TE=2000/32 ms; single voxel; PRESS | Posterior cingulate cortex /precuneus region | ↓ NAA/Cr in early AD (A+T+N−) and late AD (A+T+N+) compared to controls (A-T-N-; A+T-N-). ↑ mIns/Cr in late AD compared to controls. ↓NAA/Cr correlated with ↑ global Aβ load (PIB) and tau load (flortaucipir) on PET in whole cohort. |

| [53] | CU (n=40) | 3T, TR/TE= 3000/30 ms, single voxel; sLASER |

Posterior cingulate gyrus (automated VOI prescription) | ↑Tau PET (flortaucipir) in posterior cingulate gyrus correlated with ↓NAA/tCr and ↓Glu/tCr. |

| [54] | CSF Aβ42 positive (n=111); CSF Aβ42 negative (n=174); | 3T, TR/TE= 3000/30 ms, single voxel; PRESS | Posterior cingulate cortex /precuneus region | Visit 2 (~2.3 years after baseline): ↑ Cho/Cr, ↑mIns/Cr, ↓NAA/Cr, and ↓NAA/mI in CSF Aβ positive compared to CSF Aβ negative cases. Visit 3 (~4 years after baseline): ↑mIns/Cr, ↓NAA/Cr, and ↓NAA/mI in CSF Aβ positive compared to CSF Aβ negative cases. CSF Aβ positivity at baseline was associated with ↑mIns/Cr and ↓NAA/mIns ↑ Rate of change in the MCI Aβ positive for mIns/Cr and NAA/mIns compared to MCI Aβ negative. |

| [55] | CU younger controls (<60 years) (n=27); CU older controls (>60 years) (n=27); AD (>60 years) (n=25) | 3T, TR/TE= 1600/(31-229) ms ms, single voxel, 2D J-PRESS |

Posterior cingulate cortex /precuneus region | ↑ mIns associated with ↑CSF tau, and ↑CSF p-Tau 181; ↑ GABA associated with ↑CSF p-Tau 181p in AD dementia group |

| [56] | Two cohorts: younger age (n=30) (20–40 years); CU (n=151): older individuals (60–85 years). | 3T, TR/TE=4000/8.5 ms, single voxel, SPECIAL | Posterior cingulate cortex /precuneus region | ↑ mIns, ↑ Cr, ↑mIns/NAA, ↓ GSH, ↓ Glu in older participants compared to younger participants. |

| [57] | CU (n=289) | 1.5T, TR/TE=2000/25 ms, single voxel, PRESS | Posterior cingulate gyrus | ↑ mIns/Cr ratio in participants with two copies of APOE e4 allele compared with participants with non-carriers. ↓The NAA/mIns ratio in participants (APOE e4/e4) compared with those who were heterozygous for the APOE e4 allele and non-carriers. |

| [58]. | CU (n=15) | 3T, TR/TE=1500/68 ms, single voxel, J-edited spin echo difference method | Posterior cingulate cortex /precuneus region | ↓GSH was associated with↑the temporal and parietal Aβ load on PET with PiB. |

| [59] | aMCI (n=14); CU (n=32) | 3T, TR/TE= 3000/30 ms, single voxel, sLASER |

Posterior cingulate gyrus | ↑ Global cortical Aβ load (PiB) on PET correlated with ↓Glu/mIns ratio in the entire cohort. |

| [60] | CU older adults (n=594) c | 3T, TR/TE= 2000/30 ms, single voxel, PRESS |

Posterior cingulate gyrus | ↓ NAA/mIns and ↑ mIns/Cr at baseline were associated with ↑rate of Aβ deposition on serial PIB PET. |

| [61] | CU CSF Aβ42 negative (n=156); CU CSF Aβ42 positive (n=49), MCI CSF Aβ42 positive (n=88) | 3T, TR/TE= 2000/30 ms, single voxel, PRESS | Posterior cingulate/precuneus | ↑ mIns/Cr, ↑ Cho/Cr, ↓ NAA/Cr in MCI (CSF Aβ42 positive) compared to CU (CSF Aβ42 negative). ↑mIns/Cr in CU (CSF Aβ42 positive) compared to CU (CSF Aβ42 negative). ↑ mIns/Cr in APOE e4 allele carrier CU (CSF Aβ42 negative) compared to non e4 carrier CU (CSF Aβ42 negative). ↑ mIns/Cr and ↑ Cho/Cr were associated with ↑ Aβ deposition on PET (flutemetamol) in amyloid positive (on PET) cognitively unimpaired participants. ↑ mIns/Cr was associated with ↑ Aβ deposition on PET (flutemetamol) and in CSF Aβ42 positive cognitively unimpaired participants. |

| [62] | CU (n=16), aMCI (n=11) | 3T; TR/TE = 2000/32ms, single voxel, 2D-PRESS | Bilateral hippocampi | No difference in mIns/Cr between APOE e4 allele carriers and non-carriers |

| [63] | CU (n=21); aMCI (n=15) | 3T, TR/TE= 3000/68 ms, single voxel, MEGA-PRESS | Posterior cingulate gyrus | ↓ NAA was lower in Aβ positive subjects compared to Aβ negative (PiB PET) subjects. ↓ NAA was in APOE e4 allele carriers compared to non-carriers. |

| [64] |

APOE e4 allele non carriers (n=89); APOE e4 allele carriers (n=23) |

3T, TR/TE= 1600/30 ms, single voxel, PRESS | Posterior cingulate gyrus | ↑ Cho/Cr and ↑ mIns/Cr increase with age in APOE e4 allele carriers. ↑ Cho/Cr ratio APOE e4 carriers compared to non-carriers. |

| [19] | No to low likelihood of AD (n=17); Intermediate to high likelihood of AD likelihood (n=24) | 3T, TR/TE= 2000/30 ms, single voxel, PRESS | Posterior cingulate gyrus | ↓ NAA/Cr and NAA/mIns were associated with ↓synaptic integrity and ↑higher p-tau pathology. ↑Aβ burden was associated with ↑ mIns/Cr and ↓ NAA/mIns. ↑GFAP-positive astrocytic burden showed a trend of association with decreased NAA/Cr and NAA/mIns. |

| [65] | CU (n=17); AD (n=19) | 3T, TR/TE= 2000/30 ms, single voxel, PRESS | Hippocampus, posterior cingulate gyrus and right parietal gyrus | ↓NAA/Cr (hippocampus) was correlated with ↓CSF Aβ42. ↓NAA/Cr (parietal gyrus) was correlated with ↑CSF p-tau. ↑mIns/Cr (posterior cingulate gyrus) was correlated with ↑t-tau; |

| [66] | All subjects (n=109); AD dementia (n=40); non-AD dementia, (n=14); MCI of AD type (n=29) MCI of non-AD type (n=26) |

1.5T, TR/TE= 2000/272, single voxel, PRESS | Medial temporal lobe | ↓ NAA was correlated with ↓CSF Aβ42 in patient with AD dementia. |

| [67] | CU (n=311) | 1.5 T, 2000/30 ms, single voxel, PRESS | Posterior cingulate gyrus | ↑mIns/Cr and ↑Cho/Cr was associated ↑ Aβ load on PET (PIB). |

| [68] | Low AD likelihood (n=11); intermediate AD likelihood (n=9); high AD likelihood (n=34) | 1.5 T/ 2000/30 ms, single voxel, PRESS | Posterior cingulate gyrus | ↓ NAA/Cr, ↑mIns/Cr, ↓ NAA/mIns in postmortem frequent neuritic plaque group compared to neuritic sparse plaque group ↓ NAA/Cr in frequent neuritic plaque group compared to neuritic moderate plaque group. ↑mIns/Cr and ↓ NAA/mIns in neuritic moderate plaque group compared to neuritic sparse plaque group. ↓ NAA/Cr, ↑mIns/Cr, ↓ NAA/mIns in high-likelihood AD group compared to low-likelihood AD group ↑mIns/Cr in high-likelihood AD group compared to intermediate-likelihood AD group. ↓NAA/Cr, ↑mI/Cr, and ↓NAA/mI ratios were associated with higher Braak NFT stage, higher neuritic plaque score, and greater likeli-hood of AD. |

| [69] | CU (n=61); patient group (MCI + AD dementia (n=46) | 1.5 T/ 2000/30 ms, single voxel, PRESS | Posterior cingulate/precuneus | No differences were noted on 1H-MRS metabolite ratios (NAA/Cr, mIns/Cr, NAA/mIns) across APOE e4 carriers and non-carriers. |

| [40] | CU (63); MCI (21); AD dementia (21) | 1.5 T/ 2000/30 or 135 ms, single voxel, PRESS | Posterior cingulate gyrus; medial occipital; left superior temporal lobe | ↑ NAA/Cr ratios (medial occipital) in patients with AD dementia correlated with APOE e4 carrier status |

| [70] | postmortem brain with AD pathology (49); non-demented control (5) | In vitro ,11.7 T, perchloric acid extracts | Autopsy brain samples from various brain regions | ↑ mIns, ↑ GPC, ↓ Glu, in APOE e3/e3 samples from AD dementia patients compared to samples from normal control brains samples ↓NAA in APOE e3/e3 and APOE e4/e4 AD samples from AD dementia patients compared to samples from normal control brains (APOE e3/e3). |

2.3. Cho

2.4. Glu, Gln, Glx

2.5. GABA

2.6. GSH

2.7. Cr

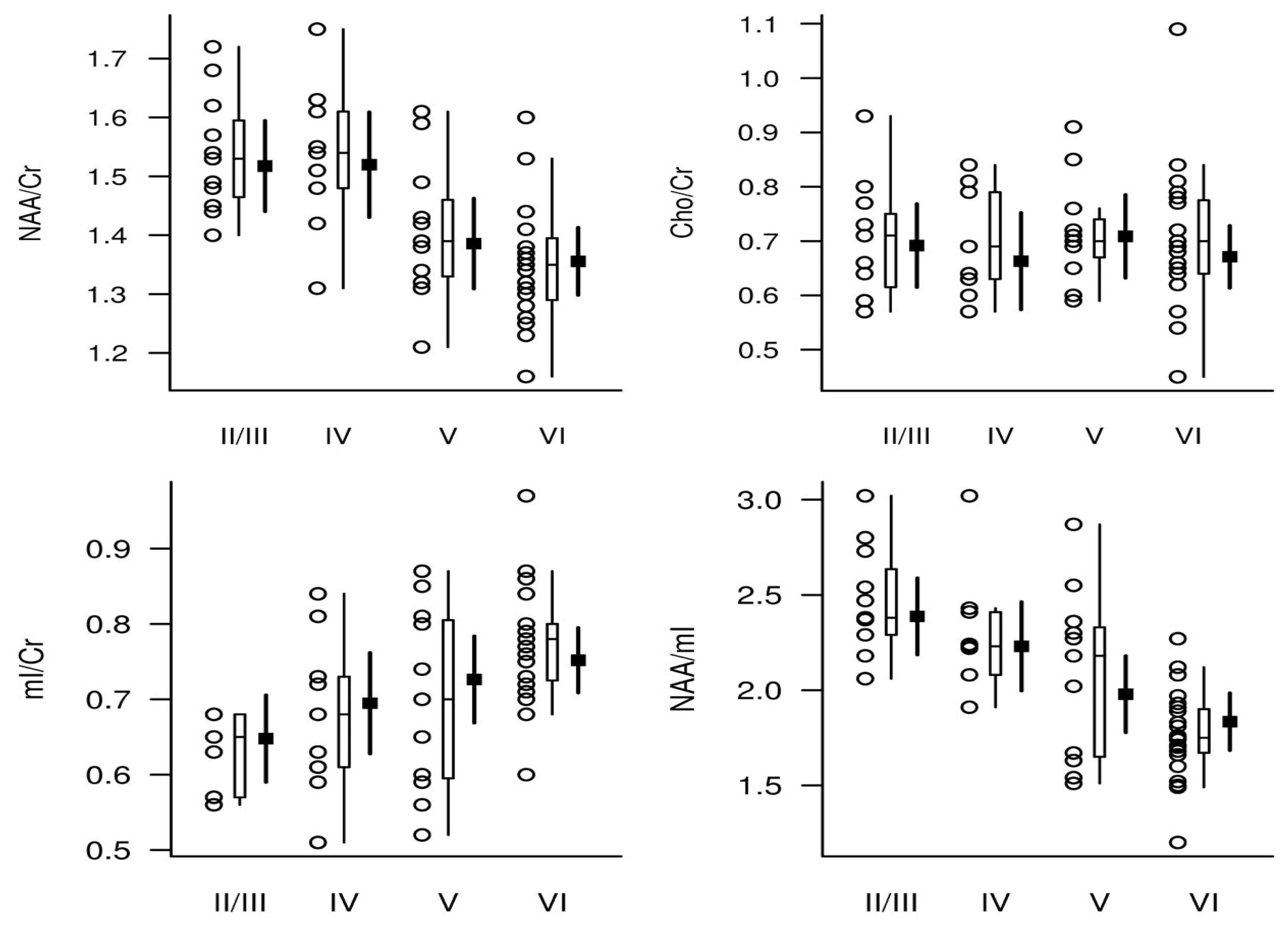

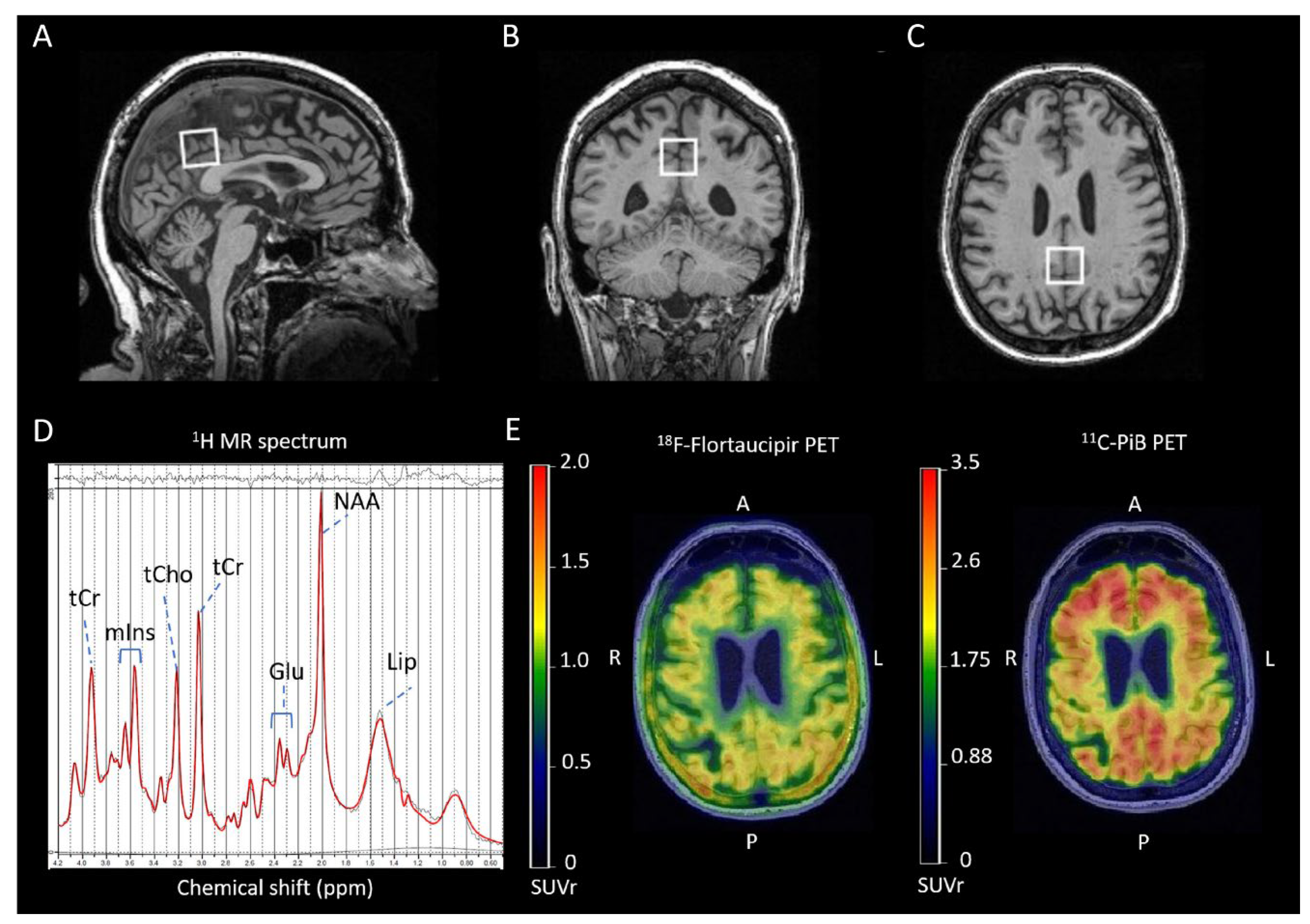

3. Association of 1H MRS Metabolites with Postmortem Neuropathology

4. Association of 1H MRS Metabolites with Tau and Amyloid PET

4.1. NAA

4.2. mIns

4.3. Cho

4.4. Glx and Glu

4.5. GABA

4.6. GSH

5. Association of 1H MRS Metabolites with Biofluid Biomarkers

5.1. NAA

5.2. mIns

5.3. Cho

5.4. Glu

5.5. GABA

6. Influence APOE ε4 Allele on 1H MRS Metabolites

7. Future Directions

References

- 2024 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2024, 20, 3708–3821. [CrossRef]

- van Dyck, C.H.; Swanson, C.J.; Aisen, P.; Bateman, R.J.; Chen, C.; Gee, M.; Kanekiyo, M.; Li, D.; Reyderman, L.; Cohen, S.; Froelich, L.; Katayama, S.; Sabbagh, M.; Vellas, B.; Watson, D.; Dhadda, S.; Irizarry, M.; Kramer, L.D.; Iwatsubo, T. Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer's Disease. N Engl J Med 2023, 388, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, C.R.; Knopman, D.S.; Jagust, W.J.; Petersen, R.C.; Weiner, M.W.; Aisen, P.S.; Shaw, L.M.; Vemuri, P.; Wiste, H.J.; Weigand, S.D.; Lesnick, T.G.; Pankratz, V.S.; Donohue, M.C.; Trojanowski, J.Q. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer's disease: An updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. The Lancet Neurology 2013, 12, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, R.J.; Xiong, C.; Benzinger, T.L.; Fagan, A.M.; Goate, A.; Fox, N.C.; Marcus, D.S.; Cairns, N.J.; Xie, X.; Blazey, T.M.; Holtzman, D.M.; Santacruz, A.; Buckles, V.; Oliver, A.; Moulder, K.; Aisen, P.S.; Ghetti, B.; Klunk, W.E.; McDade, E.; Martins, R.N.; Masters, C.L.; Mayeux, R.; Ringman, J.M.; Rossor, M.N.; Schofield, P.R.; Sperling, R.A.; Salloway, S.; Morris, J.C. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med 2012, 367, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villemagne, V.L.; Burnham, S.; Bourgeat, P.; Brown, B.; Ellis, K.A.; Salvado, O.; Szoeke, C.; Macaulay, S.L.; Martins, R.; Maruff, P.; Ames, D.; Rowe, C.C.; Masters, C.L. Amyloid β deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer's disease: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2013, 12, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R., Jr.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; Liu, E.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Montine, T.; Phelps, C.; Rankin, K.P.; Rowe, C.C.; Scheltens, P.; Siemers, E.; Snyder, H.M.; Sperling, R. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2018, 14, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, C.R., Jr.; Andrews, J.S.; Beach, T.G.; Buracchio, T.; Dunn, B.; Graf, A.; Hansson, O.; Ho, C.; Jagust, W.; McDade, E.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Okonkwo, O.C.; Pani, L.; Rafii, M.S.; Scheltens, P.; Siemers, E.; Snyder, H.M.; Sperling, R.; Teunissen, C.E.; Carrillo, M.C. Revised criteria for diagnosis and staging of Alzheimer's disease: Alzheimer's Association Workgroup. Alzheimer's & Dementia 2016, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, B.; Hampel, H.; Feldman, H.H.; Scheltens, P.; Aisen, P.; Andrieu, S.; Bakardjian, H.; Benali, H.; Bertram, L.; Blennow, K.; Broich, K.; Cavedo, E.; Crutch, S.; Dartigues, J.F.; Duyckaerts, C.; Epelbaum, S.; Frisoni, G.B.; Gauthier, S.; Genthon, R.; Gouw, A.A.; Habert, M.O.; Holtzman, D.M.; Kivipelto, M.; Lista, S.; Molinuevo, J.L.; O'Bryant, S.E.; Rabinovici, G.D.; Rowe, C.; Salloway, S.; Schneider, L.S.; Sperling, R.; Teichmann, M.; Carrillo, M.C.; Cummings, J.; Jack, C.R.; Proceedings of the Meeting of the International Working, G. ; the American Alzheimer's Association on "The Preclinical State of, A.D.; July; Washington Dc, U.S.A. Preclinical Alzheimer's disease: Definition, natural history, and diagnostic criteria. Alzheimers Dement 2016, 12, 292–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B.; Villain, N.; Frisoni, G.B.; Rabinovici, G.D.; Sabbagh, M.; Cappa, S.; Bejanin, A.; Bombois, S.; Epelbaum, S.; Teichmann, M.; Habert, M.O.; Nordberg, A.; Blennow, K.; Galasko, D.; Stern, Y.; Rowe, C.C.; Salloway, S.; Schneider, L.S.; Cummings, J.L.; Feldman, H.H. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations of the International Working Group. Lancet Neurol 2021, 20, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, M.J.; Sachdev, P. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in AD. Neurology 2001, 56, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firbank, M.J.; Harrison, R.M.; O’Brien, J.T. A Comprehensive Review of Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Studies in Dementia and Parkinson’s Disease. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders 2002, 14, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKiernan, E.; Su, L.; O'Brien, J. MRS in neurodegenerative dementias, prodromal syndromes and at-risk states: A systematic review of the literature. NMR in Biomedicine 2023, 36, e4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, F.; Barker, P.B. Various MRS Application Tools for Alzheimer Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2014, (6 suppl), S4–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piersson, A.D.; Mohamad, M.; Rajab, F.; Suppiah, S. Cerebrospinal Fluid Amyloid Beta, Tau Levels, Apolipoprotein, and 1H-MRS Brain Metabolites in Alzheimer's Disease: A Systematic Review. Academic Radiology 2021, 28, 1447–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Tan, L.; Wang, H.F.; Liu, Y.; Yin, R.H.; Wang, W.Y.; Chang, X.L.; Jiang, T.; Yu, J.T. Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy in Alzheimer's Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease 2015, 46, 1049–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh-Bahaei, N.; Chen, M.; Pappas, I. Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) in Alzheimer's Disease. Methods Mol Biol 2024, 2785, 115–142. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Song, X.; Bartha, R.; Beyea, S.; D'Arcy, R.; Zhang, Y.; Rockwood, K. Advances in high-field magnetic resonance spectroscopy in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 2014, 11, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graff-Radford, J.; Kantarci, K. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 2013, 9, 687–696. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, M.E.; Przybelski, S.A.; Lesnick, T.G.; Liesinger, A.M.; Spychalla, A.; Zhang, B.; Gunter, J.L.; Parisi, J.E.; Boeve, B.F.; Knopman, D.S.; Petersen, R.C.; Jack, C.R., Jr.; Dickson, D.W.; Kantarci, K. Early Alzheimer's disease neuropathology detected by proton MR spectroscopy. J Neurosci 2014, 34, 16247–16255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öz, G.; Alger, J.R.; Barker, P.B.; Bartha, R.; Bizzi, A.; Boesch, C.; Bolan, P.J.; Brindle, K.M.; Cudalbu, C.; Dinçer, A.; Dydak, U.; Emir, U.E.; Frahm, J.; González, R.G.; Gruber, S.; Gruetter, R.; Gupta, R.K.; Heerschap, A.; Henning, A.; Hetherington, H.P.; Howe, F.A.; Hüppi, P.S.; Hurd, R.E.; Kantarci, K.; Klomp, D.W.J.; Kreis, R.; Kruiskamp, M.J.; Leach, M.O.; Lin, A.P.; Luijten, P.R.; Marjańska, M.; Maudsley, A.A.; Meyerhoff, D.J.; Mountford, C.E.; Nelson, S.J.; Pamir, M.N.; Pan, J.W.; Peet, A.C.; Poptani, H.; Posse, S.; Pouwels, P.J.W.; Ratai, E.-M.; Ross, B.D.; Scheenen, T.W.J.; Schuster, C.; Smith, I.C.P.; Soher, B.J.; Tkáč, I.; Vigneron, D.B.; Kauppinen, R.A.; Group, F. t. M. C. Clinical Proton MR Spectroscopy in Central Nervous System Disorders. Radiology 2014, 270, 658–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffett, J.R.; Ross, B.; Arun, P.; Madhavarao, C.N.; Namboodiri, A.M. N-Acetylaspartate in the CNS: From neurodiagnostics to neurobiology. Progress in neurobiology 2007, 81, 89–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyten, P.R.; den Hollander, J.A. Observation of metabolites in the human brain by MR spectroscopy. Radiology 1986, 161, 795–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urenjak, J.; Williams, S.R.; Gadian, D.G.; Noble, M. Specific expression of N-acetylaspartate in neurons, oligodendrocyte-type-2 astrocyte progenitors, and immature oligodendrocytes in vitro. J Neurochem 1992, 59, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallan, H.H. Studies on the distribution of N-acetyl-L-aspartic acid in brain. J Biol Chem 1957, 224, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Graaf, R.A. In vivo NMR Spectroscopy: Principles and techniques. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley,. Wiley: 2007; p 592.

- Miller, B.L.; Moats, R.A.; Shonk, T.; Ernst, T.; Woolley, S.; Ross, B.D. Alzheimer disease: Depiction of increased cerebral myo-inositol with proton MR spectroscopy. Radiology 1993, 187, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Alexander, G.E.; Chang, L.; Shetty, H.U.; Krasuski, J.S.; Rapoport, S.I.; Schapiro, M.B. Brain metabolite concentration and dementia severity in Alzheimer's disease: A (1)H MRS study. Neurology 2001, 57, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moats, R.A.; Ernst, T.; Shonk, T.K.; Ross, B.D. Abnormal cerebral metabolite concentrations in patients with probable Alzheimer disease. Magn Reson Med 1994, 32, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shonk, T.K.; Moats, R.A.; Gifford, P.; Michaelis, T.; Mandigo, J.C.; Izumi, J.; Ross, B.D. Probable Alzheimer disease: Diagnosis with proton MR spectroscopy. Radiology 1995, 195, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frederick, B.B.; Satlin, A.; Yurgelun-Todd, D.A.; Renshaw, P.F. In vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of Alzheimer's disease in the parietal and temporal lobes. Biol Psychiatry 1997, 42, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnetti, L.; Tarducci, R.; Presciutti, O.; Lowenthal, D.T.; Pippi, M.; Palumbo, B.; Gobbi, G.; Pelliccioli, G.P.; Senin, U. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy can differentiate Alzheimer's disease from normal aging. Mech Ageing Dev 1997, 97, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, F.; Block, W.; Träber, F.; Keller, E.; Flacke, S.; Papassotiropoulos, A.; Lamerichs, R.; Heun, R.; Schild, H.H. Proton MR spectroscopy detects a relative decrease of N-acetylaspartate in the medial temporal lobe of patients with AD. Neurology 2000, 55, 684–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, P.; Schlosser, A.; Henriksen, O. Reduced N-acetylaspartate content in the frontal part of the brain in patients with probable Alzheimer's disease. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 1995, 13, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antuono, P.G.; Jones, J.L.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.J. Decreased glutamate + glutamine in Alzheimer's disease detected in vivo with (1)H-MRS at 0.5 T. Neurology 2001, 56, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, R.M.; Bradley, K.M.; Budge, M.M.; Styles, P.; Smith, A.D. Longitudinal quantitative proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the hippocampus in Alzheimer's disease. Brain 2002, 125 Pt 10 Pt 10, 2332–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catani, M.; Cherubini, A.; Howard, R.; Tarducci, R.; Pelliccioli, G.P.; Piccirilli, M.; Gobbi, G.; Senin, U.; Mecocci, P. (1)H-MR spectroscopy differentiates mild cognitive impairment from normal brain aging. Neuroreport 2001, 12, 2315–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantarci, K.; Petersen, R.C.; Boeve, B.F.; Knopman, D.S.; Tang-Wai, D.F.; O'Brien, P.C.; Weigand, S.D.; Edland, S.D.; Smith, G.E.; Ivnik, R.J.; Ferman, T.J.; Tangalos, E.G.; Jack, C.R., Jr. 1H MR spectroscopy in common dementias. Neurology 2004, 63, 1393–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiino, A.; Watanabe, T.; Shirakashi, Y.; Kotani, E.; Yoshimura, M.; Morikawa, S.; Inubushi, T.; Akiguchi, I. The profile of hippocampal metabolites differs between Alzheimer's disease and subcortical ischemic vascular dementia, as measured by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2012, 32, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, N.; Abe, K.; Sakoda, S.; Sawada, T. Proton MR spectroscopic study at 3 Tesla on glutamate/glutamine in Alzheimer's disease. Neuroreport 2002, 13, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarci, K.; Jack, C.R.; Xu, Y.C.; Campeau, N.G.; O’Brien, P.C.; Smith, G.E.; Ivnik, R.J.; Boeve, B.F.; Kokmen, E.; Tangalos, E.G.; Petersen, R.C. Regional metabolic patterns in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. A 1H MRS study 2000, 55, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelis, T.; Merboldt, K.D.; Hänicke, W.; Gyngell, M.L.; Bruhn, H.; Frahm, J. On the identification of cerebral metabolites in localized 1H NMR spectra of human brain in vivo. NMR Biomed 1991, 4, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindaraju, V.; Young, K.; Maudsley, A.A. Proton NMR chemical shifts and coupling constants for brain metabolites. NMR Biomed 2000, 13, 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, C.D. A guide to the metabolic pathways and function of metabolites observed in human brain 1H magnetic resonance spectra. Neurochem Res 2014, 39, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratai, E.-M.; Alshikho, M.J.; Zürcher, N.R.; Loggia, M.L.; Cebulla, C.L.; Cernasov, P.; Reynolds, B.; Fish, J.; Seth, R.; Babu, S.; Paganoni, S.; Hooker, J.M.; Atassi, N. Integrated imaging of [11C]-PBR28 PET, MR diffusion and magnetic resonance spectroscopy 1H-MRS in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. NeuroImage: Clinical 2018, 20, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutma, E.; Fancy, N.; Weinert, M.; Tsartsalis, S.; Marzin, M.C.; Muirhead, R.C.J.; Falk, I.; Breur, M.; de Bruin, J.; Hollaus, D.; Pieterman, R.; Anink, J.; Story, D.; Chandran, S.; Tang, J.; Trolese, M.C.; Saito, T.; Saido, T.C.; Wiltshire, K.H.; Beltran-Lobo, P.; Phillips, A.; Antel, J.; Healy, L.; Dorion, M.-F.; Galloway, D.A.; Benoit, R.Y.; Amossé, Q.; Ceyzériat, K.; Badina, A.M.; Kövari, E.; Bendotti, C.; Aronica, E.; Radulescu, C.I.; Wong, J.H.; Barron, A.M.; Smith, A.M.; Barnes, S.J.; Hampton, D.W.; van der Valk, P.; Jacobson, S.; Howell, O.W.; Baker, D.; Kipp, M.; Kaddatz, H.; Tournier, B.B.; Millet, P.; Matthews, P.M.; Moore, C.S.; Amor, S.; Owen, D.R. Translocator protein is a marker of activated microglia in rodent models but not human neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, J.G.; Stagg, C.J.; Dennis, A. Chapter 2.5 - Other Significant Metabolites: Myo-Inositol, GABA, Glutamine, and Lactate. In Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy; Stagg, C., Rothman, D., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, 2014; pp. 122–138. [Google Scholar]

- Bitsch, A.; Bruhn, H.; Vougioukas, V.; Stringaris, A.; Lassmann, H.; Frahm, J.; Brück, W. Inflammatory CNS demyelination: Histopathologic correlation with in vivo quantitative proton MR spectroscopy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1999, 20, 1619–1627. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner, S.J.; Van Bergen, J.M.G.; Gietl, A.F.; Buck, A.; Hock, C.; Pruessmann, K.P.; Henning, A.; Unschuld, P.G. Gray matter gamma-hydroxy-butyric acid and glutamate reflect beta-amyloid burden at old age. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2024, 16, e12587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, K.; Hirata, K.; Kokubo, N.; Maeda, T.; Tagai, K.; Endo, H.; Takahata, K.; Shinotoh, H.; Ono, M.; Seki, C.; Tatebe, H.; Kawamura, K.; Zhang, M.R.; Shimada, H.; Tokuda, T.; Higuchi, M.; Takado, Y. Investigating neural dysfunction with abnormal protein deposition in Alzheimer's disease through magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging, plasma biomarkers, and positron emission tomography. Neuroimage Clin 2024, 41, 103560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spotorno, N.; Najac, C.; Stomrud, E.; Mattsson-Carlgren, N.; Palmqvist, S.; van Westen, D.; Ronen, I.; Hansson, O. Astrocytic function is associated with both amyloid-beta and tau pathology in non-demented APOE ϵ4 carriers. Brain Commun 2022, 4, fcac135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hone-Blanchet, A.; Bohsali, A.; Krishnamurthy, L.C.; Shahid, S.S.; Lin, Q.; Zhao, L.; Bisht, A.S.; John, S.E.; Loring, D.; Goldstein, F.; Levey, A.; Lah, J.; Qiu, D.; Crosson, B. Frontal Metabolites and Alzheimer's Disease Biomarkers in Healthy Older Women and Women Diagnosed with Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 2022, 87, 1131–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Abrigo, J.; Liu, W.; Han, E.Y.; Yeung, D.K.W.; Shi, L.; Au, L.W.C.; Deng, M.; Chen, S.; Leung, E.Y.L.; Ho, C.L.; Mok, V.C.T.; Chu, W.C.W. Lower Posterior Cingulate N-Acetylaspartate to Creatine Level in Early Detection of Biologically Defined Alzheimer's Disease. Brain Sci 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, F.; Joers, J.M.; Deelchand, D.K.; Park, Y.W.; Przybelski, S.A.; Lesnick, T.G.; Senjem, M.L.; Zeydan, B.; Knopman, D.S.; Lowe, V.J.; Vemuri, P.; Mielke, M.M.; Machulda, M.M.; Jack, C.R.; Petersen, R.C.; Oz, G.; Kantarci, K. (1)H MR spectroscopy biomarkers of neuronal and synaptic function are associated with tau deposition in cognitively unimpaired older adults. Neurobiol Aging 2022, 112, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voevodskaya, O.; Poulakis, K.; Sundgren, P.; van Westen, D.; Palmqvist, S.; Wahlund, L.-O.; Stomrud, E.; Hansson, O.; Westman, E.; Swedish Bio, F.S.G. Brain myoinositol as a potential marker of amyloid-related pathology: A longitudinal study. Neurology 2019, 92, e395–e405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullins, R.; Reiter, D.; Kapogiannis, D. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy reveals abnormalities of glucose metabolism in the Alzheimer's brain. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2018, 5, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, S.; Emir, U.; Stagg, C.J.; Near, J.; Mekle, R.; Schubert, F.; Zsoldos, E.; Mahmood, A.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Kivimäki, M.; Ebmeier, K.P.; Mackay, C.E.; Filippini, N. Effect of age and the APOE gene on metabolite concentrations in the posterior cingulate cortex. Neuroimage 2017, 152, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waragai, M.; Moriya, M.; Nojo, T. Decreased N-Acetyl Aspartate/Myo-Inositol Ratio in the Posterior Cingulate Cortex Shown by Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy May Be One of the Risk Markers of Preclinical Alzheimer's Disease: A 7-Year Follow-Up Study. J Alzheimers Dis 2017, 60, 1411–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, G.C.; Mao, X.; Kang, G.; Chang, E.; Pandya, S.; Vallabhajosula, S.; Isaacson, R.; Ravdin, L.D.; Shungu, D.C. Relationships among Cortical Glutathione Levels, Brain Amyloidosis, and Memory in Healthy Older Adults Investigated In Vivo with (1)H-MRS and Pittsburgh Compound-B PET. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2017, 38, 1130–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeydan, B.; Deelchand, D.K.; Tosakulwong, N.; Lesnick, T.G.; Kantarci, O.H.; Machulda, M.M.; Knopman, D.S.; Lowe, V.J.; Jack, C.R., Jr.; Petersen, R.C.; Öz, G.; Kantarci, K. Decreased Glutamate Levels in Patients with Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment: An sLASER Proton MR Spectroscopy and PiB-PET Study. J Neuroimaging 2017, 27, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedelska, Z.; Przybelski, S.A.; Lesnick, T.G.; Schwarz, C.G.; Lowe, V.J.; Machulda, M.M.; Kremers, W.K.; Mielke, M.M.; Roberts, R.O.; Boeve, B.F.; Knopman, D.S.; Petersen, R.C.; Jack, C.R.; Kantarci, K. H-1-MRS metabolites and rate of beta-amyloid accumulation on serial PET in clinically normal adults. Neurology 2017, 89, 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voevodskaya, O.; Sundgren, P.C.; Strandberg, O.; Zetterberg, H.; Minthon, L.; Blennow, K.; Wahlund, L.O.; Westman, E.; Hansson, O.; Swedish Bio, F. s. g. , Myo-inositol changes precede amyloid pathology and relate to APOE genotype in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2016, 86, 1754–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Wu, W.; Liu, R.; Liang, X.; Yu, T.; Chen, X.; Feng, J.; Guo, A.; Xie, Y.; Yang, H.; Huang, M.; Tian, C.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Y. APOE genotype and age modifies the correlation between cognitive status and metabolites from hippocampus by a 2D (1)H-MRS in non-demented elders. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1202–e1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riese, F.; Gietl, A.; Zölch, N.; Henning, A.; O'Gorman, R.; Kälin, A.M.; Leh, S.E.; Buck, A.; Warnock, G.; Edden, R.A.E.; Luechinger, R.; Hock, C.; Kollias, S.; Michels, L. Posterior cingulate γ-aminobutyric acid and glutamate/glutamine are reduced in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and are unrelated to amyloid deposition and apolipoprotein E genotype. Neurobiology of aging 2015, 36, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomar, J.J.; Gordon, M.L.; Dickinson, D.; Kingsley, P.B.; Uluğ, A.M.; Keehlisen, L.; Huet, S.; Buthorn, J.J.; Koppel, J.; Christen, E.; Conejero-Goldberg, C.; Davies, P.; Goldberg, T.E. APOE genotype modulates proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy metabolites in the aging brain. Biol Psychiatry 2014, 75, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, D.M.; Heinze, H.J.; Kaufmann, J. Association of 1H-MR spectroscopy and cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in Alzheimer's disease: Diverging behavior at three different brain regions. J Alzheimers Dis 2013, 36, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, F.; Lewczuk, P.; Gür, O.; Block, W.; Ende, G.; Frölich, L.; Hammen, T.; Arlt, S.; Kornhuber, J.; Kucinski, T.; Popp, J.; Peters, O.; Maier, W.; Träber, F.; Wiltfang, J. Association of N-acetylaspartate and cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 in dementia. J Alzheimers Dis 2011, 27, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantarci, K.; Lowe, V.; Przybelski, S.A.; Senjem, M.L.; Weigand, S.D.; Ivnik, R.J.; Roberts, R.; Geda, Y.E.; Boeve, B.F.; Knopman, D.S.; Petersen, R.C.; Jack, C.R., Jr. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy, β-amyloid load, and cognition in a population-based sample of cognitively normal older adults. Neurology 2011, 77, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarci, K.; Knopman, D.S.; Dickson, D.W.; Parisi, J.E.; Whitwell, J.L.; Weigand, S.D.; Josephs, K.A.; Boeve, B.F.; Petersen, R.C.; Jack, C.R., Jr. Alzheimer disease: Postmortem neuropathologic correlates of antemortem 1H MR spectroscopy metabolite measurements. Radiology 2008, 248, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantarci, K.; Smith, G.E.; Ivnik, R.J.; Petersen, R.C.; Boeve, B.F.; Knopman, D.S.; Tangalos, E.G.; Jack, C.R., Jr. 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy, cognitive function, and apolipoprotein E genotype in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2002, 8, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klunk, W.E.; Panchalingam, K.; McClure, R.J.; Stanley, J.A.; Pettegrew, J.W. Metabolic alterations in postmortem Alzheimer's disease brain are exaggerated by Apo-E4. Neurobiol Aging 1998, 19, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.C.; Gant, N. Chapter 2.3 - The Biochemistry of Choline. In Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy; Stagg, C., Rothman, D., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, 2014; pp. 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, B.L.; Chang, L.; Booth, R.; Ernst, T.; Cornford, M.; Nikas, D.; McBride, D.; Jenden, D.J. In vivo 1H MRS choline: Correlation with in vitro chemistry/histology. Life Sci 1996, 58, 1929–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, P.B.; Breiter, S.N.; Soher, B.J.; Chatham, J.C.; Forder, J.R.; Samphilipo, M.A.; Magee, C.A.; Anderson, J.H. Quantitative proton spectroscopy of canine brain: In vivo and in vitro correlations. Magn Reson Med 1994, 32, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerhoff, D.J.; MacKay, S.; Constans, J.M.; Norman, D.; Van Dyke, C.; Fein, G.; Weiner, M.W. Axonal injury and membrane alterations in Alzheimer's disease suggested by in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging. Ann Neurol 1994, 36, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, S.; Meyerhoff, D.J.; Constans, J.M.; Norman, D.; Fein, G.; Weiner, M.W. Regional gray and white matter metabolite differences in subjects with AD, with subcortical ischemic vascular dementia, and elderly controls with 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging. Arch Neurol 1996, 53, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, S.; Ezekiel, F.; Di Sclafani, V.; Meyerhoff, D.J.; Gerson, J.; Norman, D.; Fein, G.; Weiner, M.W. Alzheimer disease and subcortical ischemic vascular dementia: Evaluation by combining MR imaging segmentation and H-1 MR spectroscopic imaging. Radiology 1996, 198, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fayed, N.; Andrés, E.; Viguera, L.; Modrego, P.J.; Garcia-Campayo, J. Higher glutamate+glutamine and reduction of N-acetylaspartate in posterior cingulate according to age range in patients with cognitive impairment and/or pain. Acad Radiol 2014, 21, 1211–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Blamire, A.M.; Watson, R.; He, J.; Hayes, L.; O'Brien, J.T. Whole-brain patterns of 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy imaging in Alzheimer's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Translational Psychiatry 2016, 6, e877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantal, S.; Labelle, M.; Bouchard, R.W.; Braun, C.M.; Boulanger, Y. Correlation of regional proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic metabolic changes with cognitive deficits in mild Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2002, 59, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurtman, R.J.; Blusztajn, J.K.; Maire, J.C. "Autocannibalism" of choline-containing membrane phospholipids in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease-A hypothesis. Neurochem Int 1985, 7, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satlin, A.; Bodick, N.; Offen, W.W.; Renshaw, P.F. Brain proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) in Alzheimer's disease: Changes after treatment with xanomeline, an M1 selective cholinergic agonist. Am J Psychiatry 1997, 154, 1459–1461. [Google Scholar]

- Hertz, L. Functional interactions between neurons and astrocytes I. Turnover and metabolism of putative amino acid transmitters. Progress in neurobiology 1979, 13, 277–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bak, L.K.; Schousboe, A.; Waagepetersen, H.S. The glutamate/GABA-glutamine cycle: Aspects of transport, neurotransmitter homeostasis and ammonia transfer. J Neurochem 2006, 98, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, B.T.; Van Hoesen, G.W.; Damasio, A.R. Alzheimer's disease: Glutamate depletion in the hippocampal perforant pathway zone. Ann Neurol 1987, 22, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupsingh, R.; Borrie, M.; Smith, M.; Wells, J.L.; Bartha, R. Reduced hippocampal glutamate in Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging 2011, 32, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puts, N.A.; Edden, R.A. In vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy of GABA: A methodological review. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc 2012, 60, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Liu, D.; Yin, J.; Qian, T.; Shrestha, S.; Ni, H. Glutamate-glutamine and GABA in brain of normal aged and patients with cognitive impairment. Eur Radiol 2017, 27, 2698–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rae, C.D.; Williams, S.R. Glutathione in the human brain: Review of its roles and measurement by magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Anal Biochem 2017, 529, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, P.K.; Tripathi, M.; Sugunan, S. Brain oxidative stress: Detection and mapping of anti-oxidant marker 'Glutathione' in different brain regions of healthy male/female, MCI and Alzheimer patients using non-invasive magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2012, 417, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, D.; Mandal, P.K.; Tripathi, M.; Vishwakarma, G.; Mishra, R.; Sandal, K. Quantitation of in vivo brain glutathione conformers in cingulate cortex among age-matched control, MCI, and AD patients using MEGA-PRESS. Hum Brain Mapp 2020, 41, 194–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, P.K.; Saharan, S.; Tripathi, M.; Murari, G. Brain Glutathione Levels - A Novel Biomarker for Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer's Disease. Biological Psychiatry 2015, 78, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabel, M.; Nackenoff, A.; Kirsch, W.M.; Harrison, F.E.; Perry, G.; Schrag, M. Markers of oxidative damage to lipids, nucleic acids and proteins and antioxidant enzymes activities in Alzheimer's disease brain: A meta-analysis in human pathological specimens. Free Radic Biol Med 2018, 115, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, M.; Kaddurah-Daouk, R. Creatine and creatinine metabolism. Physiol Rev 2000, 80, 1107–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rackayova, V.; Cudalbu, C.; Pouwels, P.J.W.; Braissant, O. Creatine in the central nervous system: From magnetic resonance spectroscopy to creatine deficiencies. Analytical Biochemistry 2017, 529, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Ernst, T.; Poland, R.E.; Jenden, D.J. In vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the normal aging human brain. Life Sciences 1996, 58, 2049–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maudsley, A.A.; Domenig, C.; Govind, V.; Darkazanli, A.; Studholme, C.; Arheart, K.; Bloomer, C. Mapping of brain metabolite distributions by volumetric proton MR spectroscopic imaging (MRSI). Magn Reson Med 2009, 61, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, D.E.; Howe, F.A.; van den Boogaart, A.; Griffiths, J.R.; Brown, M.M. Aging of the adult human brain: In vivo quantitation of metabolite content with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging 1999, 9, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheimer, S.M.; Bryan, R.N.; Conturo, T.E.; Soher, B.J.; Preziosi, T.J.; Barker, P.B. Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy and gadolinium-DTPA perfusion imaging of asymptomatic MRI white matter lesions. Magn Reson Med 1995, 33, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ongür, D.; Prescot, A.P.; Jensen, J.E.; Cohen, B.M.; Renshaw, P.F. Creatine abnormalities in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res 2009, 172, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Edden, R.A.; Gao, F.; Wang, G.; Wu, L.; Zhao, B.; Wang, M.; Chan, Q.; Chen, W.; Barker, P.B. Decreased γ-aminobutyric acid levels in the parietal region of patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015, 41, 1326–1331. [Google Scholar]

- Mielke, M.M.; Dage, J.L.; Frank, R.D.; Algeciras-Schimnich, A.; Knopman, D.S.; Lowe, V.J.; Bu, G.; Vemuri, P.; Graff-Radford, J.; Jack, C.R., Jr.; Petersen, R.C. Performance of plasma phosphorylated tau 181 and 217 in the community. Nat Med 2022, 28, 1398–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R., Jr.; Wiste, H.J.; Algeciras-Schimnich, A.; Weigand, S.D.; Figdore, D.J.; Lowe, V.J.; Vemuri, P.; Graff-Radford, J.; Ramanan, V.K.; Knopman, D.S.; Mielke, M.M.; Machulda, M.M.; Fields, J.; Schwarz, C.G.; Cogswell, P.M.; Senjem, M.L.; Therneau, T.M.; Petersen, R.C. Comparison of plasma biomarkers and amyloid PET for predicting memory decline in cognitively unimpaired individuals. Alzheimers Dement 2024, 20, 2143–2154. [Google Scholar]

- Pais, M.V.; Forlenza, O.V.; Diniz, B.S. Plasma Biomarkers of Alzheimer's Disease: A Review of Available Assays, Recent Developments, and Implications for Clinical Practice. J Alzheimers Dis Rep 2023, 7, 355–380. [Google Scholar]

- Janelidze, S.; Teunissen, C.E.; Zetterberg, H.; Allué, J.A.; Sarasa, L.; Eichenlaub, U.; Bittner, T.; Ovod, V.; Verberk, I.M.W.; Toba, K.; Nakamura, A.; Bateman, R.J.; Blennow, K.; Hansson, O. Head-to-Head Comparison of 8 Plasma Amyloid-β 42/40 Assays in Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurology 2021, 78, 1375–1382. [Google Scholar]

- Nabers, A.; Perna, L.; Lange, J.; Mons, U.; Schartner, J.; Güldenhaupt, J.; Saum, K.U.; Janelidze, S.; Holleczek, B.; Rujescu, D.; Hansson, O.; Gerwert, K.; Brenner, H. Amyloid blood biomarker detects Alzheimer's disease. EMBO Molecular Medicine 2018, 10, e8763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, A.; Kaneko, N.; Villemagne, V.L.; Kato, T.; Doecke, J.; Doré, V.; Fowler, C.; Li, Q.-X.; Martins, R.; Rowe, C.; Tomita, T.; Matsuzaki, K.; Ishii, K.; Ishii, K.; Arahata, Y.; Iwamoto, S.; Ito, K.; Tanaka, K.; Masters, C.L.; Yanagisawa, K. High performance plasma amyloid-β biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 2018, 554, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janelidze, S.; Mattsson, N.; Palmqvist, S.; Smith, R.; Beach, T.G.; Serrano, G.E.; Chai, X.; Proctor, N.K.; Eichenlaub, U.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Reiman, E.M.; Stomrud, E.; Dage, J.L.; Hansson, O. Plasma P-tau181 in Alzheimer’s disease: Relationship to other biomarkers, differential diagnosis, neuropathology and longitudinal progression to Alzheimer’s dementia. Nature Medicine 2020, 26, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karikari, T.K.; Pascoal, T.A.; Ashton, N.J.; Janelidze, S.; Benedet, A.L.; Rodriguez, J.L.; Chamoun, M.; Savard, M.; Kang, M.S.; Therriault, J.; Schöll, M.; Massarweh, G.; Soucy, J.-P.; Höglund, K.; Brinkmalm, G.; Mattsson, N.; Palmqvist, S.; Gauthier, S.; Stomrud, E.; Zetterberg, H.; Hansson, O.; Rosa-Neto, P.; Blennow, K. Blood phosphorylated tau 181 as a biomarker for Alzheimer's disease: A diagnostic performance and prediction modelling study using data from four prospective cohorts. The Lancet Neurology 2020, 19, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janelidze, S.; Berron, D.; Smith, R.; Strandberg, O.; Proctor, N.K.; Dage, J.L.; Stomrud, E.; Palmqvist, S.; Mattsson-Carlgren, N.; Hansson, O. Associations of Plasma Phospho-Tau217 Levels With Tau Positron Emission Tomography in Early Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurology 2021, 78, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielke, M.M.; Hagen, C.E.; Xu, J.; Chai, X.; Vemuri, P.; Lowe, V.J.; Airey, D.C.; Knopman, D.S.; Roberts, R.O.; Machulda, M.M.; Jack, C.R., Jr.; Petersen, R.C.; Dage, J.L. Plasma phospho-tau181 increases with Alzheimer's disease clinical severity and is associated with tau- and amyloid-positron emission tomography. Alzheimer's & Dementia 2018, 14, 989–997. [Google Scholar]

- Gafson, A.R.; Barthélemy, N.R.; Bomont, P.; Carare, R.O.; Durham, H.D.; Julien, J.P.; Kuhle, J.; Leppert, D.; Nixon, R.A.; Weller, R.O.; Zetterberg, H.; Matthews, P.M. Neurofilaments: Neurobiological foundations for biomarker applications. Brain 2020, 143, 1975–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, N.; Cullen, N.C.; Andreasson, U.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K. Association Between Longitudinal Plasma Neurofilament Light and Neurodegeneration in Patients With Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurology 2019, 76, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielke, M.M.; Syrjanen, J.A.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Vemuri, P.; Skoog, I.; Machulda, M.M.; Kremers, W.K.; Knopman, D.S.; Jack, C., Jr.; Petersen, R.C.; Kern, S. Plasma and CSF neurofilament light: Relation to longitudinal neuroimaging and cognitive measures. Neurology 2019, 93, e252–e260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verberk, I.M.W.; Laarhuis, M.B.; van den Bosch, K.A.; Ebenau, J.L.; van Leeuwenstijn, M.; Prins, N.D.; Scheltens, P.; Teunissen, C.E.; van der Flier, W.M. Serum markers glial fibrillary acidic protein and neurofilament light for prognosis and monitoring in cognitively normal older people: A prospective memory clinic-based cohort study. The Lancet Healthy Longevity 2021, 2, e87–e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, C.; Foiani, M.S.; Moore, K.; Convery, R.; Bocchetta, M.; Neason, M.; Cash, D.M.; Thomas, D.; Greaves, C.V.; Woollacott, I.O.; Shafei, R.; Van Swieten, J.C.; Moreno, F.; Sanchez-Valle, R.; Borroni, B.; Laforce, R., Jr.; Masellis, M.; Tartaglia, M.C.; Graff, C.; Galimberti, D.; Rowe, J.B.; Finger, E.; Synofzik, M.; Vandenberghe, R.; de Mendonca, A.; Tagliavini, F.; Santana, I.; Ducharme, S.; Butler, C.R.; Gerhard, A.; Levin, J.; Danek, A.; Frisoni, G.; Sorbi, S.; Otto, M.; Heslegrave, A.J.; Zetterberg, H.; Rohrer, J.D. Plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein is raised in progranulin-associated frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2020, 91, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braak, H.; Braak, E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 1991, 82, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thal, D.R.; Rüb, U.; Orantes, M.; Braak, H. Phases of A beta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology 2002, 58, 1791–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.W.; Deelchand, D.K.; Joers, J.M.; Hanna, B.; Berrington, A.; Gillen, J.S.; Kantarci, K.; Soher, B.J.; Barker, P.B.; Park, H.; Oz, G.; Lenglet, C. AutoVOI: Real-time automatic prescription of volume-of-interest for single voxel spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med 2018, 80, 1787–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantarci, K.; Jicha, G.A. Development of <sup>1</sup>H MRS biomarkers for tracking early predementia Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2019, 92, 209–210. [Google Scholar]

- Deelchand, D.K.; Adanyeguh, I.M.; Emir, U.E.; Nguyen, T.-M.; Valabregue, R.; Henry, P.-G.; Mochel, F.; Öz, G. Two-site reproducibility of cerebellar and brainstem neurochemical profiles with short-echo, single-voxel MRS at 3T. Magnetic resonance in medicine 2015, 73, 1718–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öz, G.; Deelchand, D.K.; Wijnen, J.P.; Mlynárik, V.; Xin, L.; Mekle, R.; Noeske, R.; Scheenen, T.W.J.; Tkáč, I. Advanced single voxel (1) H magnetic resonance spectroscopy techniques in humans: Experts' consensus recommendations. NMR Biomed 2020, e4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, T.K.; Godfrey, K.J.; Ware, A.L.; Yeates, K.O.; Harris, A.D. Harmonization of multi-site MRS data with ComBat. NeuroImage 2022, 257, 119330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.D.; Amiri, H.; Bento, M.; Cohen, R.; Ching, C.R.K.; Cudalbu, C.; Dennis, E.L.; Doose, A.; Ehrlich, S.; Kirov, I.I.; Mekle, R.; Oeltzschner, G.; Porges, E.; Souza, R.; Tam, F.I.; Taylor, B.; Thompson, P.M.; Quidé, Y.; Wilde, E.A.; Williamson, J.; Lin, A.P.; Bartnik-Olson, B. Harmonization of multi-scanner in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy: ENIGMA consortium task group considerations. Frontiers in Neurology 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).