1. Introduction

Cranial cruciate ligament disease is a common reason for hind limb lameness in dogs and is frequently associated with medial meniscal lesions at the time of surgery (ranging from 20 to 70% of cases [

4,

11,

12,

13,

14]). Conversely, lateral meniscal lesions are less frequent, occurring in 2% of dogs with partial or complete cranial cruciate ligament ruptures [

4,

11,

12,

15]. The menisci play a crucial role in the stifle joint ensuring joint congruency [

11], aiding in load distribution, contributing to articular cartilage lubrication and preventing synovial entrapment during weight-bearing [

6,

16]. The medial meniscus is attached to the tibia, joint capsule and medial collateral ligament, whereas the lateral meniscus is more mobile. Damage of the medial meniscus often occurs in association with complete cranial cruciate ligament tears causing instability in the stifle joint. This occurs when the medial meniscus is compressed between the femoral condyle and tibial plateau during cranial displacement of the tibia, leading to shear forces exacerbated by internal rotation, frequently leading to meniscal damage [

6]. Various diagnostic methods such as ultrasonography, arthrography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and arthrotomy have been utilized to examine the menisci, with arthroscopy considered the gold standard for stifle joint assessment [

6,

15,

17,

18]. The most commonly reported lesions are fibrillation of the surface and compression injuries, longitudinal tears and bucket handle tears, radial or transverse tears, horizontal, oblique or flap tears, complex macerated tears and a folded caudal horn [

1,

6,

8,

11,

19]. Current treatments depend on the type of injury and range from partial caudal meniscectomy and caudal hemimeniscectomy to total meniscectomy, aimed at removing damaged tissue and alleviating pain [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Partial meniscectomy, being favored for less degenerative changes than meniscectomy, has become the most common treatment [

6,

12,

20,

21]. However, resection still compromises meniscal function and results in stress concentration, possibly predisposing to osteoarthritis [

13,

22]. Studies in humans have shown that meniscal suturing can lead to less osteoarthritic progression, reduced pain and improved long-term function compared to meniscectomy [

23]. Some studies emphasizing the importance of sparing the meniscus have also been performed in dogs: one study reveals that an intact lateral meniscus transmits 29% of the load. In the case of lateral partial meniscectomy with three-quarters of the lateral meniscus remaining, the load transmission increases to 45%. After total meniscectomy, the load transmission increases to 313%, a 7-fold increase in load passing through the remaining structures [

6,

24]. Other studies have found a 2.5-fold increase in the area of peak pressure on the tibial plateau after medial caudal pole meniscectomy. In cases of cranial cruciate deficient stifles treated by tibial plateau levelling osteotomy (TPLO), a 1.7-fold increase was still noted after medial caudal pole meniscectomy [

13].

Given the potential adverse effects of meniscectomy, efforts have been made to develop meniscal repair techniques that preserve meniscal tissue and promote healing [

9,

12,

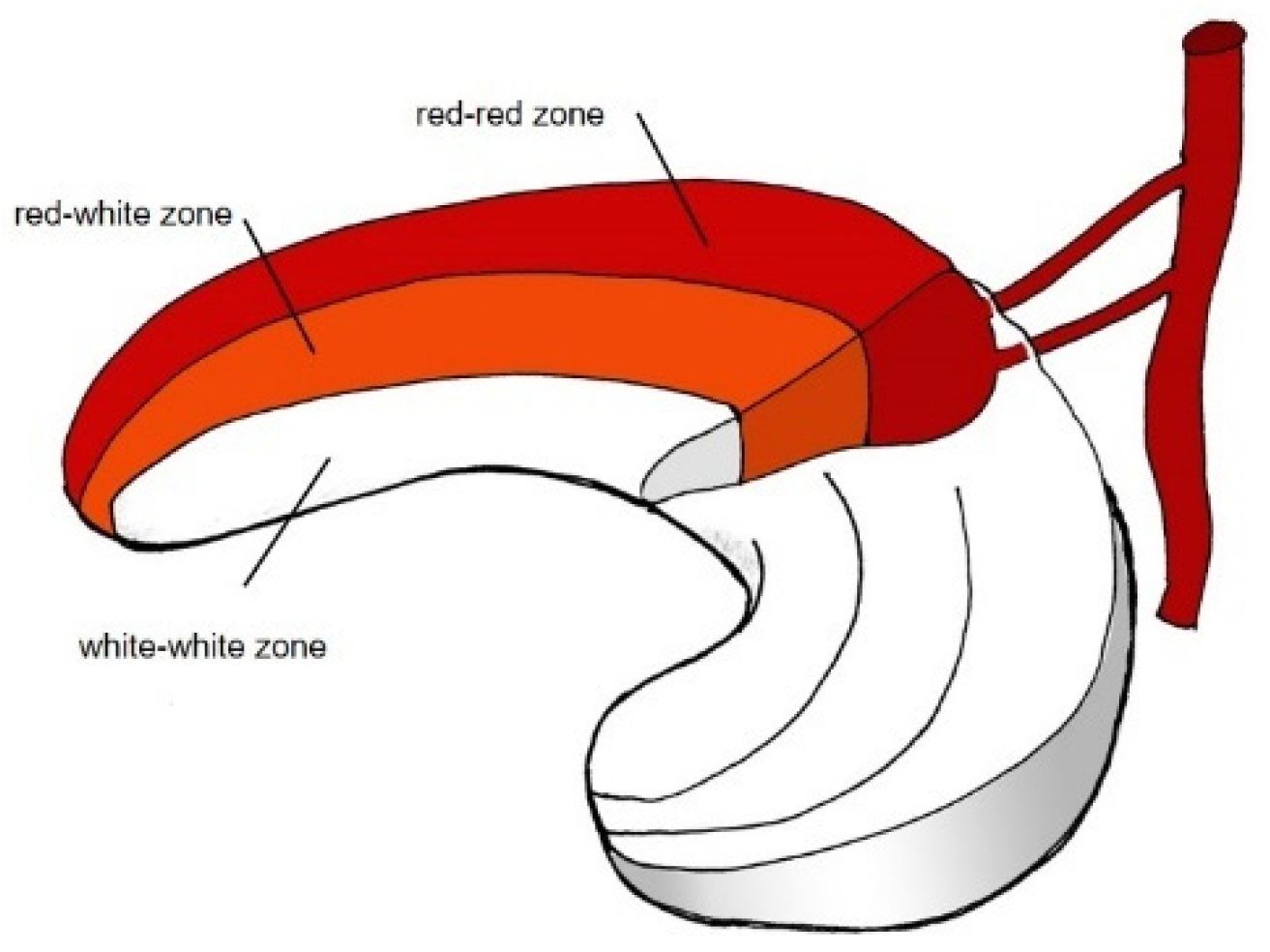

25]. The meniscus’s limited vascularization restricts healing to the vascularised red-red zone. It is divided into three zones depending on the vascularization pattern. The inner avascular white-white zone with low to no healing potential, the red-red zone on the outer rim with vascularization and good healing potential and the red-white zone in between (

Figure 1 [

26]) with lower vascularization and lower healing potential [

5].

Concerning suture types, Thieman et al. [

27] evaluated three different meniscal repair techniques for the restoration of femorotibial contact mechanics in a cadaveric dog stifle model with bucket handle tears of the medial meniscus. Sutured menisci restored by vertical, horizontal and cruciate sutures were compared. No difference was detected in restoring the contact area, the mean contact pressure and the peak contact pressure between the suture types used [

27]. The restoration of mean contact pressure and peak contact pressure after suture repair was improved for repaired menisci independent of the suture type when compared to partial meniscectomy and closer to healthy controls than after partial meniscectomy. All repair techniques restored normal contact mechanisms of the medial compartment. In contrast, partial meniscectomy caused a 35% decrease in the contact area, a 57% increase in the mean contact pressure, and a 55% increase in peak contact pressure compared to the intact meniscus [

27].

In human medicine, arthroscopic meniscal repair techniques are the gold standard for suturing meniscal injuries [

23,

28] and various techniques have been documented [

23,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. The outside-in meniscal repair technique for treating anterior and mid-body-tears was already introduced in 1985 by Warren et al. [

32]. The needles are passed from outside the joint capsule through the two fragments of the meniscus, and both extremities of the suture are retrieved at the outside of the joint capsule to tie the knot extra-articularly [

23,

28]. The inside-out technique, applicable for mid-body and posterior tears, entails threading sutures from inside the joint through both segments of the tear before passing them through the capsule. These sutures are then retrieved outside the joint and secured over the capsule using a minor open approach [

23]. Additionally, fully arthroscopic all-inside repair techniques have been detailed, employing various suture devices [

23,

33]. These devices facilitate the introduction and tightening of knots entirely from within the joint [

23], eliminating the need for an open approach, thereby saving time and minimizing pain [

23].

A major concern for implementing arthroscopic or arthroscopic-assisted meniscal repair techniques in dogs is the limited joint space. Suture knots, are therefore preferably placed as capsular-side knots outside of the joint [

8]. Techniques such as shaver, electrocoagulation, and joint distraction have been detailed to enhance visualization and working space in the canine stifle, facilitating complex procedures like meniscal suturing [

8,

9,

19,

34,

35,

36].

Moses et al. described an open modified ”inside-out” technique in dogs, used for caudal peripheral detachment and longitudinal tears of the medial meniscus [

7]. Suture strands were tightened by a knot on the outside of the joint capsule and a second mattress suture was placed accordingly as required [

7]. The performance and description of arthroscopically performed meniscal sutures in dogs are still rare [

8,

9,

37,

38].

Our study aimed to evaluate the feasibility of an arthroscopic-assisted double-needle technique for meniscal sutures in the caudal horn of the medial meniscus in dogs under appropriate joint distraction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Inclusion Criteria

Client-owned dogs presented to the Clinica M. E. Miller in Cavriago, Italy, for hind limb lameness assessment were included in the study when meeting specific inclusion criteria. Clinical and radiographic evaluations were performed alongside with preoperative blood tests. A complete cranial cruciate ligament tear and a concurrent lesion of the caudal horn of the medial meniscus suitable for meniscal suture repair were confirmed via arthroscopic examination. The meniscal lesion was considered appropriate for meniscal suture treatment when it was located in the abaxial third of the meniscus (red-red zone,

Figure 1), with enough healthy tissue present to ensure sufficient holding force for the sutures.

General anesthesia was initiated intravenously with Midazolam and Propofol and maintained with isoflurane in oxygen. Perioperative pain medication included subcutaneous meloxicam (Meloxicam Injection® 20mg/ml, Dechra, Putney Inc., Portland USA) and intravenous buprenorphine at the time of induction (buprenorphine 0.01 mg/kg, Buprenodale®, Dechra limited, Stoke-on-Trent, United Kingdom). Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis was provided with a single intravenous dose of Cefazoline (20 mg/kg, Cefamezin®, Pfizer Inc., NY, USA) at the time of induction up to 2022. After that date, no antibiotic prophylaxis was used if the procedure was uneventful and completed within two hours of surgery.

2.2. Arthroscopic Procedure

Arthroscopy of the stifle joint was conducted in dorsal recumbency with the dog positioned in a foam cushion, the unaffected hind limb secured in an abducted position and the affected limb freely hanging for manipulation. Preliminary evaluation of the joint was initially performed arthroscopically without distraction. After detection of the meniscal lesion or if other abnormalities required further evaluation, the joint distractor was applied to the limb. Joint distraction was achieved using the Titan distractor device (Titan distractor, Ad Maiora, Cavriago, Italy), facilitating insertion of arthroscopic instruments. The distractor was applied as described previously [

8]. A 2.4 mm 30° fore-oblique arthroscope and a palpation hook were respectively inserted through cranio-medial and craniolateral portals.

The level of distraction was meticulously adjusted during the procedure to ensure adequate visualization of the meniscus. This enabled precise diagnosis and the execution of necessary meniscal suture maneuvers tailored to the patient’s needs.

2.3. Meniscal Sutures

Suture application for meniscal tears was performed in meniscal lesions located in the abaxial third of the meniscus (red-red zone, as illustrated in

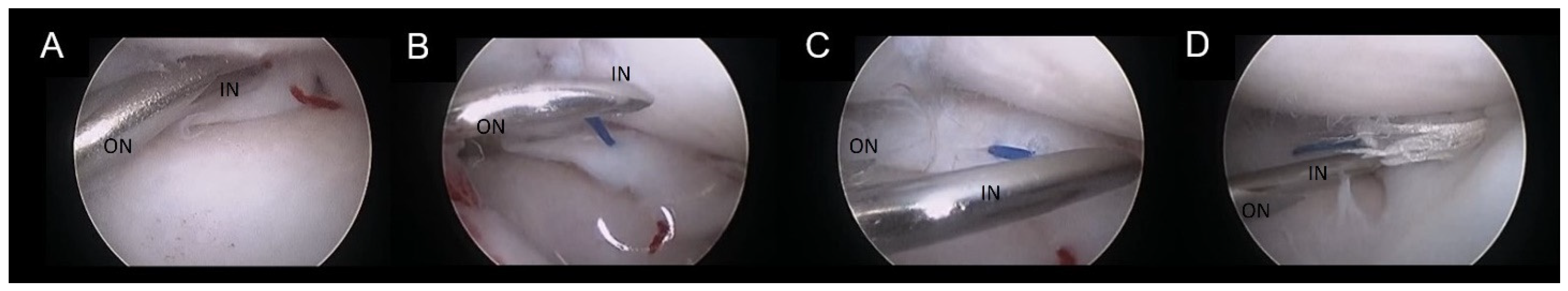

Figure 1) when an adequate amount of healthy tissue was present to ensure a robust suture hold. The suturing technique employed was the double needle method, an evolution of the single-needle technique already described [

8]. A 22-G spinal needle (inner needle, IN) was passed through the lumen of a 16-G standard needle (outer needle, ON) (

Figure 2). The assembly was introduced through the cranio-lateral portal and navigated in a caudo-medial direction until contact with the meniscal surface was reached. Subsequently, the spinal needle was advanced through the meniscus plan to the lesion and across the lesion site (

Figure 2A). It was then pushed through the joint capsule, emerging in the caudo-medial aspect of the stifle joint, where the needle tip was palpated and exposed by a stab incision. Soft tissue dissection was meticulously performed to reveal the needle tip. The needle trocar was removed. The suture material was then inserted into the inner needle’s tip and advanced until caught at the needle cone, secured by manual grasp. Retracting the inner needle tip back into the joint rendered the suture strand visible within the joint (

Figure 2B). While the outer needle maintained meniscal stability and kept a working distance between the meniscus and the scope, a suture loop was created. The inner needle’s bevel was rotated. The spinal needle was once more propelled through the meniscus abaxial to the initial insertion (

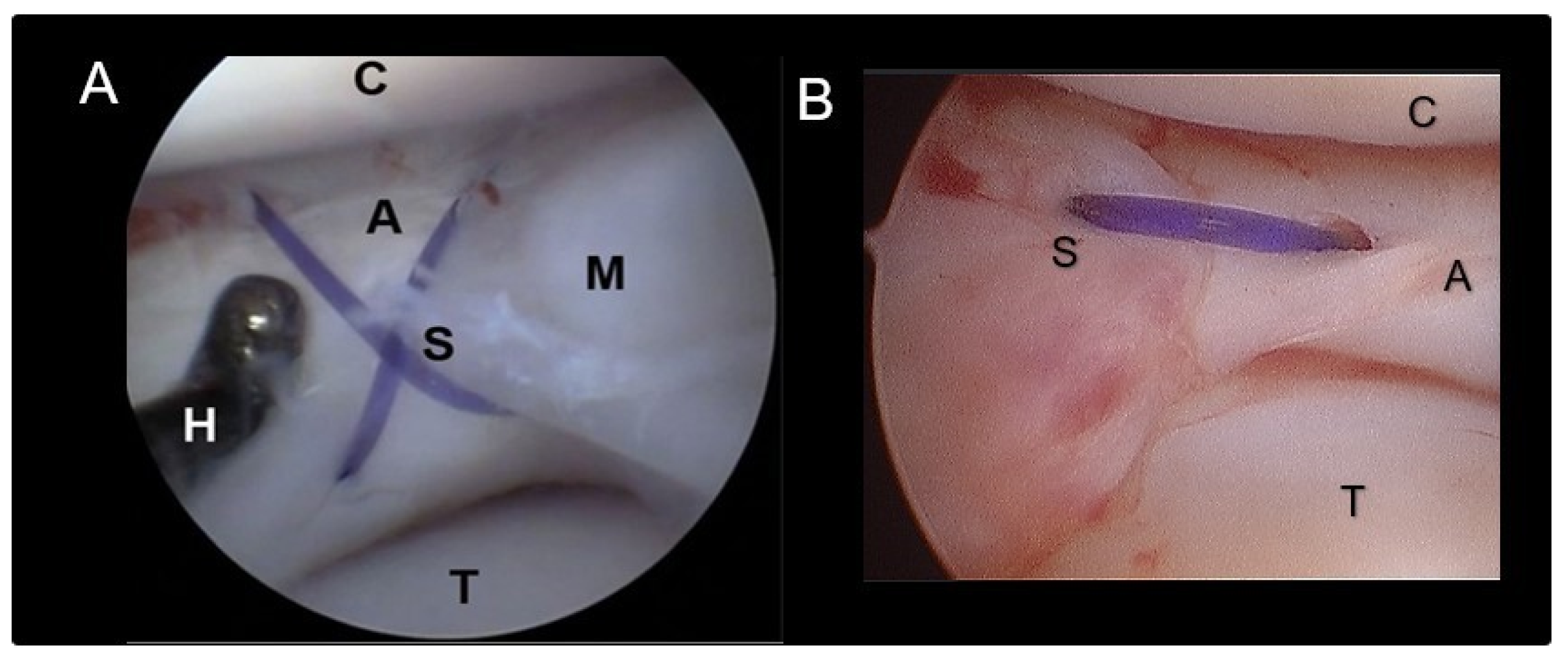

Figure 2C,D), pushing the suture through the meniscus. Vigilance was exercised to prevent suture damage by the needle’s tip. In case of suture damage, the procedure was repeated. Upon the needle tip’s re-emergence at the joint capsule, the suture loop was retrieved from the needle tip, and the extremity was pulled out, leaving the two extremities of the suture exiting from the wound. Following needle removal, the two suture ends were carefully tightened without tension by a square knot and 4-5 secure knots, ensuring the meniscal segments were closely apposed without gap formation or bulging. Sutures were applied in cross, horizontal or vertical configuration (

Figure 3). The process was repeated as many times as needed to meet clinical requirements (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) and achieve a secure hold by the sutures. The choice of suture type and material was tailored to each patient, with 2-4 crossed and horizontal or vertical mattress sutures executed using polypropylene (Prolene® USP 3-0, Ethicon) and/ or polydioxanone (PDS II®, USP 3-0, Ethicon) (

Table 1). Any complication encountered was recorded.

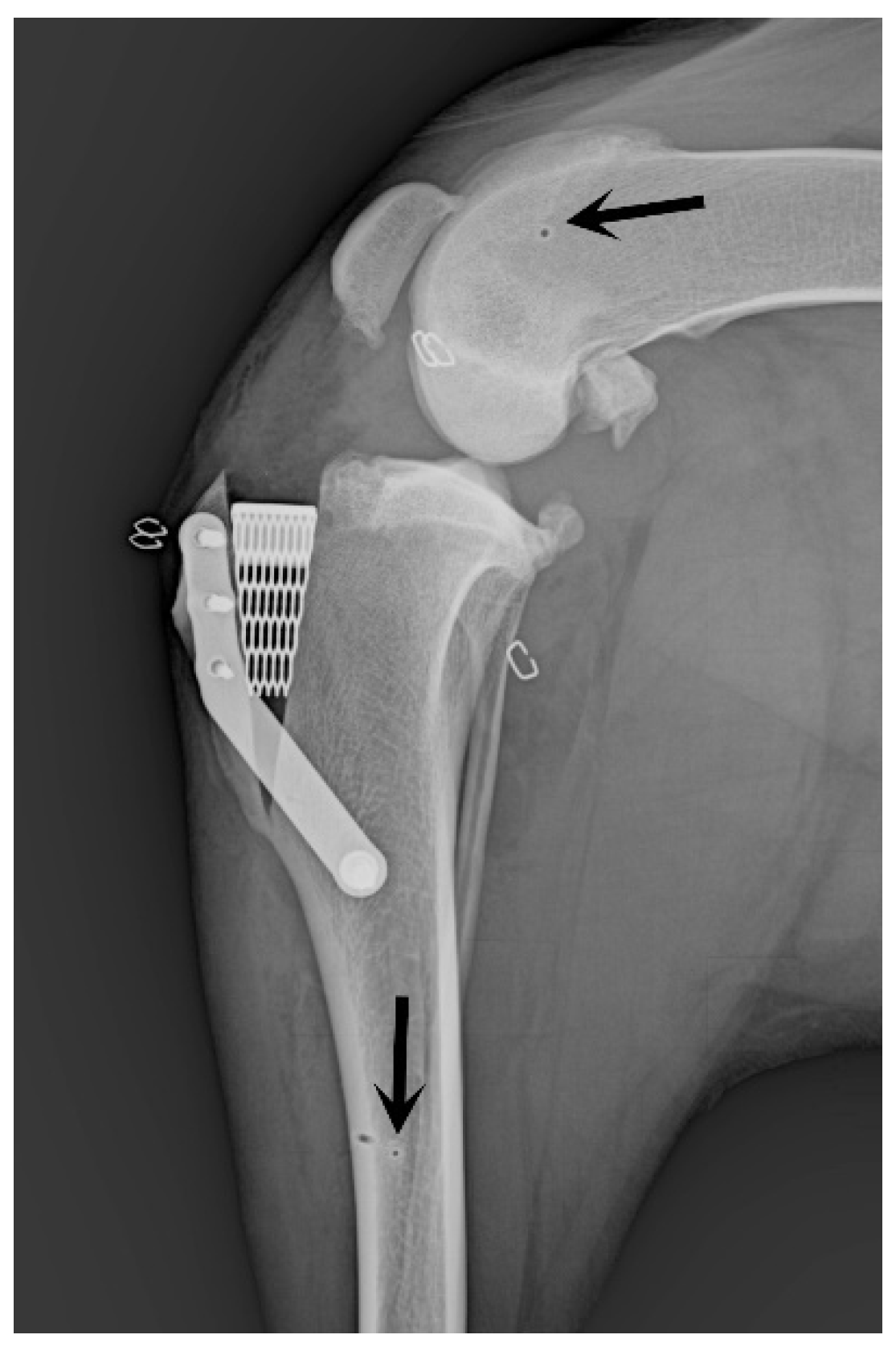

2.4. Surgical Stabilization of the Stifle Joint

The stifle joint underwent surgical stabilization to treat cranial cruciate ligament injuries, employing the X-Porous tibial tuberosity advancement (X-Porous TTA) procedure [

10] (implants: Ad Maiora, Cavriago, Italy). Post-surgical assessments included radiographic evaluations for all cases (

Figure 4).

2.5. Postoperative Management

Dogs were discharged as soon as they recovered from general anesthesia and vital parameters were stable. The postoperative analgesic regimen included meloxicam (Meloxoral®, 0.1 mg/ kg once daily, PO, A.T.I. s.r.l. Ozzano Emilia, Italy) administered over two weeks and tramadol (Altadol®, Formevet s.r.l., Milano, Italy; 3 mg/kg) dispensed for five days. Cephalexin (ICF Vet®, I.C.F. Industria Chimica Fine s.r.l. Pignano, Italy; 20 mg/kg twice daily) was prescribed as antibiotic coverage for one week up to 2022, afterwards no antibiotic was prescribed if the procedure was considered uneventful. All dogs were managed without bandages and were subjected to restricted and controlled activity. They were limited to leash walks of specified duration, three to four times daily over an eight-week period.

2.6. Postsurgical Follow Up

Routine clinical and radiographic evaluations were scheduled at 10 and 45 days postoperatively, with subsequent assessments based on the surgeon’s judgment until bone healing. The follow-up period was in average 6 months. A second look arthroscopy was not performed in any case.

3. Results

Eight client-owned dogs presented for hind limb lameness met the inclusion criteria of cranial cruciate ligament rupture and medial meniscal lesions in the abaxial third of the medial meniscus amenable to meniscal repair by meniscal suturing using the double needle technique described (n=10).

The breeds included were Cane Corso (n=2), Labrador (n=1), Dobermann (n=1), German Shorthair (n=1), Boxer (n=1), Maremmano-abruzzese (n=1) and mixed breed (n=1) with an average age of 5.28 years (range, from 1.8 to 11.5 years). Two of the dogs underwent treatment for both limbs at different times. The mean body weight was 36 kg ± 7.1 kg (range 24 to 48 kg). Three male and five female, six left and four right stifles were included in the study. Preoperative blood tests showed no abnormalities. Presurgical radiographic evaluation revealed joint effusion of the stifle in all dogs. The arthroscopic assessment was performed in all dogs without distraction for preliminary evaluation. When the meniscal lesion was detected or some abnormality required further evaluation, the distractor was applied to the limb. Sufficient distraction allowed for the evaluation of both menisci in all cases with slight difficulties in visualization in two cases (

Table 1). Findings confirmed a complete cranial cruciate ligament rupture in all dogs, and meniscal lesions were identified in the abaxial third of the caudal horn of the medial meniscus (

Table 1,

Figure 2). Utilizing the double-needle technique, meniscal suturing was successfully performed in all dogs with surgical times ranging from 42 to 83 minutes (average 64 minutes ± 22 minutes). The suturing was done by two stitches in four cases, three stitches in four cases, and four stitches in one case. Of the total number of twenty-seven stitches, twenty-one were vertical, two were horizontal and four were crossed. The suture materials used were nonabsorbable polypropylene (sixteen stitches) and polydioxanone (eleven stitches) (

Table 1).

Intraoperative complications included difficult visualization in two cases and suture cutting by the needle tip during the passage of the suture through the meniscus in three cases (11,11% of stitches, 5,55% of passages through the meniscus) (

Table 1). No further complications were recorded when repeating the procedure.

Following meniscal repair, a X-Porous TTA (modified tibial tuberosity advancement) procedure was routinely performed in all dogs to restore stifle stability. Postoperative tibial compression test was negative in all dogs.

Postoperative clinical rechecks revealed no complications associated with the meniscal repair technique. One dog presented a tibial fracture one month after surgery for a reason unrelated to the study. The fracture was subsequently treated with plate osteosynthesis.

4. Discussion

Cranial cruciate ligament disease often involves damage to the caudal horn of the medial meniscus, resulting in pain and the progression of osteoarthritis. Given the potential adverse effects of meniscectomy and the attempt to avoid arthrotomy, arthroscopic meniscal repair is a standard procedure in humans [

23,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32], but still rarely described in dogs [

8,

9].

Moses et al. have detailed a medial arthrotomy approach that involves lateral reflection of the patella to facilitate meniscal suturing [

7]. The double needle technique described in our study allowed us to avoid arthrotomy and required only a small stab incision at the caudomedial aspect of the joint for suture passage and tightening as mentioned above. Meniscal suturing was successfully performed in all cases. Despite concerns regarding the potential for greater iatrogenic injury described for arthroscopy [

39], our experience suggests it is less invasive, offers superior visualization of the menisci and simplifies the procedure compared to arthrotomy [

7,

8]. The Titan distractor provided adequate visualization in most cases [7, 8]. In two stifles, visualization was reduced, but it was still sufficient to perform the procedure without iatrogenic damage. Cartilage damage was evaluated during the procedure, but no second look arthroscopy was performed later on as it was denied by the owner. Cadaver studies may be an option to evaluate the cartilage damage using specific stains to quantify the damage in a more objective way in the future [

38].

The only intraoperative complication encountered was suture damage by the needle itself during passage through the meniscus. This complication was addressed by repeating the procedure and no further issues were reported.

Meniscal lesions were only considered appropriate for meniscal suture treatment when located in the abaxial third of the meniscus (red-red zone) when enough healthy tissue was present to ensure a robust suture hold, assuming that only tears in this zone would have potential for healing. Because no reevaluation was performed arthroscopically, no information about meniscal healing status or presence of persistent non-union can be provided. Future research should investigate if healing occurs and if healing capacities in dogs are comparable to humans.

The type of suture stiches used do not seem to influence the restoration of meniscal tissue as shown by Thieman et al. [

27]. The use of crossed, horizontal or vertical sutures were therefore considered feasible and adapted to the specific lesion.

In early investigations, monofilament synthetic absorbable suture (polydioxanone (PDS II, size 1.5metric) was described as suture material for meniscal sutures [

7], observing no clinical complication. No recommendations can be given for the choice of suture material in canine patients. The choice is not evidence-based and very indifferent, depending on technique and surgeons preference [

9]. Further studies are required to determine which suture material allows healing without creating foreign body reactions within the joint and in the same time would provide enough strength until healing is finished. Additionally, the suture requires low elongation to prevent gap formation and a sufficient load to failure until healing has occurred [

40]. The use of permanent sutures facilitate extended fixation periods necessary for the healing, maturation and remodeling of the meniscus [

40], despite the implication of leaving foreign material within the stifle joint. In early and still limited human studies, insufficient evidence supports that non-absorbable sutures in meniscus repair surgery enhance meniscal healing success rate compared to absorbable sutures [

41]. Conversely, other hints exist that absorbable sutures promote meniscal healing [

41]. In our study, we integrated the healing benefits with prolonged stability, utilizing absorbable sutures (polydioxanone) to foster healing alongside with non-absorbable sutures (polypropylene) to ensure extended stability throughout the healing process. A constraint of our study is the challenge of definitively verifying holding capacity, suture integrity and meniscal healing within a considerable long follow-up period.

Although follow-up arthroscopy could potentially help to answer this question, the lack of clinical symptoms frequently results in owners’ hesitancy towards authorizing this supplementary procedure, given the requirements for anesthesia and the risk of inflicting additional surgical trauma to the dog. The small number of patients together with a short follow-up period of 6 months in average is part of the limitations of our study. None of the dogs showed recurrence of lameness or other clinical signs. In humans, 19% of meniscus repairs undergo revision, with failures often occurring beyond the second postoperative year. Anyway, it remains uncertain whether these failures are due to the meniscus repair itself or to additional adjacent tears [

42].

Furthermore, it is important to emphasize the necessity of the stifle stabilization technique to mitigate the forces within a cruciate-ligament deficient stifle joint, which is crucial for enabling meniscal healing [

7]. In our case cohort, stability was achieved through a variant of the tibial tuberosity advancement technique, known as X-Porous TTA [

10]. Other stabilization methods may be adequate if appropriate stability can be achieved [

7]. The differences and choice of stabilization techniques available are beyond the focus of this study.

Meniscal sutures of the caudal horn of the medial meniscus were treatable by the arthroscopic assisted double-needle technique described. However, additional research is necessary to refine the suture technique to prevent subsequent damage, ascertain meniscal healing and assess long-term clinical outcomes. Furthermore, mechanical testing and clinical studies are required to determine the most suitable suture material to prevent elongation and gap formation, to enhance healing and to avoid intraarticular foreign body reactions in the long term. It is also important to understand how ambulation affects meniscal movements and the suture’s holding capacity.