1. Introduction

Mental health problems are a growing concern for young people world-wide. Yet despite being the demographic most vulnerable to mental ill-health, young people in their teens and early adulthood are the most reluctant to seek help, particularly professional help. Although accessing mental health services is efficacious for young people, a gap remains between the need for treatment and the use of mental health services [

1,

2]. Reasons for the treatment gap include practical, social, and psychological obstacles [

3]. If these barriers are not overcome, efficacious treatment will fail to achieve population level outcomes. It is, therefore, critical to understand the barriers that prevent young people from accessing mental health services and how to best combat them.

Key barriers to help-seeking have been identified [

4]. These include practical issues, like finances and distance to services; social concerns, such as fear of social stigma [

5], feelings of shame [

6], and negative perceptions of social support [

7]. A prominent psychological barrier is a preference for self-reliance [

4,

8], whereby emerging adults prefer to deal with their emotional problems by themselves [

9].

Self-Reliance

Self-reliance is broadly defined as a preference for solving problems on one’s own. This preference is particularly salient for young people, as adolescence and early adulthood are a time of growing autonomy, independence, and control over life choices. Self-reliance is considered a sign of resilience and a necessary part of transitioning to adulthood [

10]. During adolescence, individuals develop an increased sense of autonomy and decision-making capacity and become more oriented towards peers than their family of origin for support [

8]. This developmental period can be characterised as a time of learning to balance the need for independence with the need for support. Failure to balance these needs appropriately (i.e., being insufficiently independent or insufficiently support-seeking) is likely to be maladaptive [

11].

A maladaptively high preference for self-reliance (i.e., a preference to manage all problems on one’s own) can reduce help-seeking, increase mental distress, increase risk of suicidality [

12], and is associated with poorer evaluations of informal supports [

12,

13]. Maladaptively high self-reliance has been described using terms such as survivalist self-reliance [

14], profound self-reliance [

14,

15], excessive self-reliance [

16], and extreme self-reliance [

11,

12]. Although it is most commonly known as extreme self-reliance in the growing body of literature related to this subject [

7], terminology differences demonstrate that self-reliance is an area of research where a unified approach has yet to be developed.

Just as terminology around self-reliance varies, conceptualisations, theoretical frameworks, and measures of self-reliance vary also [

13,

18]. Measures of self-reliance differ greatly and are occasionally tautological. Studies have used single item measures (e.g., “I prefer to solve problems on my own” [

11,

19], borrowed items from help-seeking measures, or used items that relate to self-reliance but do not capture the whole construct (e.g., “I know how to help myself” [

20]. We need to better understand self-reliance to develop a more robust construct and measure that can be used to unify future research efforts.

Self-reliance in managing mental health concerns has been linked to several relevant concepts in the literature, including fear of stigma [

8], concerns about confidentiality [

21] concerns about self-stigma [

5], pride in independence [

11], beliefs that problems could not be understood by others [

16], and holding masculine ideals [

21]. Cultural factors such as perceived need for care and desire to engage with medical supports have also been associated with the tendency for self-reliance [

22]. It is apparent that self-reliance can be considered a multidimensional construct that is influenced by social (e.g., cultural), psychological (e.g., attitudinal), and practical (e.g., availability of supports) factors.

Trust and Self-Reliance

Self-reliance is likely to require a level of trust in oneself; whereas, help-seeking requires that an individual places their trust in another [

7]. Relative levels of trust (in self and others) would therefore correlate with both tendency for self-reliance and tendency for help-seeking. Several of the factors identified as being related to self-reliance appear to be conceptually related to trust. For example, low perceptions of social support [

11], poor past experiences with help-seeking [

23], and distrust in others following negative social interactions [

16], have all been linked to extreme self-reliance. A distrust of others as a result of past experiences or a perception of low social support indicates a belief that trust in others is not an option. A small qualitative study of young adults reported that those who exhibited “profound” self-reliance tended to endorse beliefs about trust such as “…the only person I could trust is myself…” as well as reporting help-seeking attitudes like “I know I’ll only ask for help when I’m in really, really deep trouble” [

15]. These responses suggest a relationship between high levels of self-trust and simultaneously low trust in others, extreme self-reliance, and reduced help-seeking.

Trust has been shown to increase help-seeking behaviours in young people: having available and trusted health professionals facilitates increased help-seeking in mental health contexts [

4,

24]. Trust has also been recognised as a facilitator of help-seeking in informal settings, such as trust in referral suggestions from friends and family [

25]. Trust in others is, therefore, likely to facilitate help-seeking, but the relationships among trust, self-reliance, and help-seeking behaviours need to be better understood to determine how self-reliance may act as a facilitator or barrier to help-seeking among young people.

Prior research has established that self-reliance and help-seeking are linked, and that trust appears to be related to self-reliance as well as being a facilitator of seeking help. What this relationship looks like and how young adults, who are negotiating independence and need for support, conceptualise self-reliance and trust is an area in need of further research. The present study investigates the concept of self-reliance from the perspective of young adults, specifically focusing on what ways, if any, trust is related to self-reliance.

2. Materials and Methods

We report the study in accordance with the 32-item COREQ checklist to enhance transparency and rigor [

26].

Participants

Thirty young people living in Australia aged 18-25 years participated. The mean age was 21.6 years (SD=2.3); 18 were female and 12 were male. None were non-binary and nine identified as being from a culturally and linguistically diverse background.

Participants were recruited using flyers and snowball sampling. We aimed for a diverse range of young people, including those from hard to reach communities and snowball sampling is effective for this [

27]. Flyers were placed in community centres and other community meeting spaces and participants were encouraged to pass information on to friends. A

$30 e-gift voucher was provided as compensation for their time. Given the opt-in nature of participation, there were no participants who refused and none dropped out of the study.

Procedure

Potential participants contacted the researchers via details on the flyer. They were provided with a Participant Information form and informed consent was obtained prior to interview. Interviews were conducted online via Zoom between March and April 2023 and lasted between 20 and 60 minutes (

M = 38 minutes). Interviews were divided evenly between two researchers to reduce potential bias [

28] and ensure that stylistic differences were minimised. Researchers used a reflexive interview style to reduce the likelihood of leading participants and to increase confidence in interpreting participant responses. Both researchers were female and final year Master of Clinical Psychology students.

After some introductory discussion to establish rapport, the interview guide comprised 13 questions related to perceptions of self-reliance, with the questions increasing in specificity as the interview progressed. Questions asked participants to define the concept of self-reliance, indicate factors (both individual and environmental) that might affect self-reliance, whether trust of self and others was related to self-reliance, and to consider how a preference for self-reliance might impact help-seeking. Demographic questions were also included (e.g., age, cultural identity).

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Canberra Human Research Ethics Committee (202211903).

Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim using the assistance of the online transcription service, Otter.ai. Transcripts were not provided back to participants for comment. They were reviewed to remove identifying information (e.g., names) and correct transcription errors. QSR International NVivo 10 software was used for coding and analysis. Thematic analysis was conducted using Braun and Clark six-step data analysis process [

28,

29], and adopting a realist approach [

30]. A combined inductive (data driven) and deductive (theory driven) approach was taken. Researchers began by familiarising themselves with the data by reviewing each transcript thoroughly. Based on recommendations [

31], six interviews (20% of the data) were selected as being representative of the sample (i.e., age, gender, vulnerability, cultural identity, and endorsed beliefs). These were coded individually by the two researchers. Coding and theme construction for these six interviews were then compared between researchers and discrepancies were recoded to increase reliability (e.g., hope was recoded to optimism to increase uniformity). These transcripts were then re-coded by the project supervisor for additional reliability. The remaining interviews were divided between the two researchers and coded independently using the themes generated during initial coding, but with the addition of themes appropriate. NVivo graphing software was used to compare the final codes made by the two researchers. Participants did not provide feedback on the findings.

3. Results

Through the thematic analysis themes related to self-reliance, trust, self-awareness and help-seeking were constructed, as described below.

Self-Reliance

Participants agreed that some level of self-reliance would be adaptive. Many felt that it was useful and important to not rely on other people, specifically noting the importance of making one’s own decisions. This type of self-reliance was described as similar to independence, and many participants struggled to distinguish between the two despite feeling them to be separate concepts.

Extreme self-reliance was distinguished from useful or adaptive self-reliance, with participants saying that extreme self-reliance was associated with an unwillingness to seek help even when it was necessitated by the situation. Subthemes included “pride” and “fears of being a burden”. One participant noted “pride can kind of push self-reliance to the extreme and then create more problems” (Participant 7). Another said, “I think there’s also like another bit of self-reliance where it’s like ‘No, I don’t want to be a burden on anyone’. I wouldn’t want to be a burden on the healthcare system” (Participant 21).

The notion of insufficient self-reliance was also raised, conceptualised as “over dependence” and a lack of confidence in one’s own abilities. Often, insufficient self-reliance appeared synonymous with excessive help-seeking, but also included aspects of independence such as lack of financial or emotional independence. Participants reflected, “I don’t see it as detracting from self-reliance to want to speak to other people. But it’s bad if like you can’t cope without speaking to other people” (Participant 3) and “People that aren’t self-reliant are quite codependent and they might feel really anxious in their relationships” (Participant 7). There was general consensus that individuals should attempt to do things themselves, only seeking help when they cannot complete a task and not purely because the task is difficult.

When considering factors that would lead to insufficient self-reliance, some participants felt that individuals who had not had the opportunity to develop age-appropriate independence would be more likely to lack self-reliance. They conceptualised self-reliance as some blend of independent action coupled with a sense of personal ability, “Too much reliance on family unit that can make it difficult to have an understanding of your own personal ability to manage things” (Participant 13).

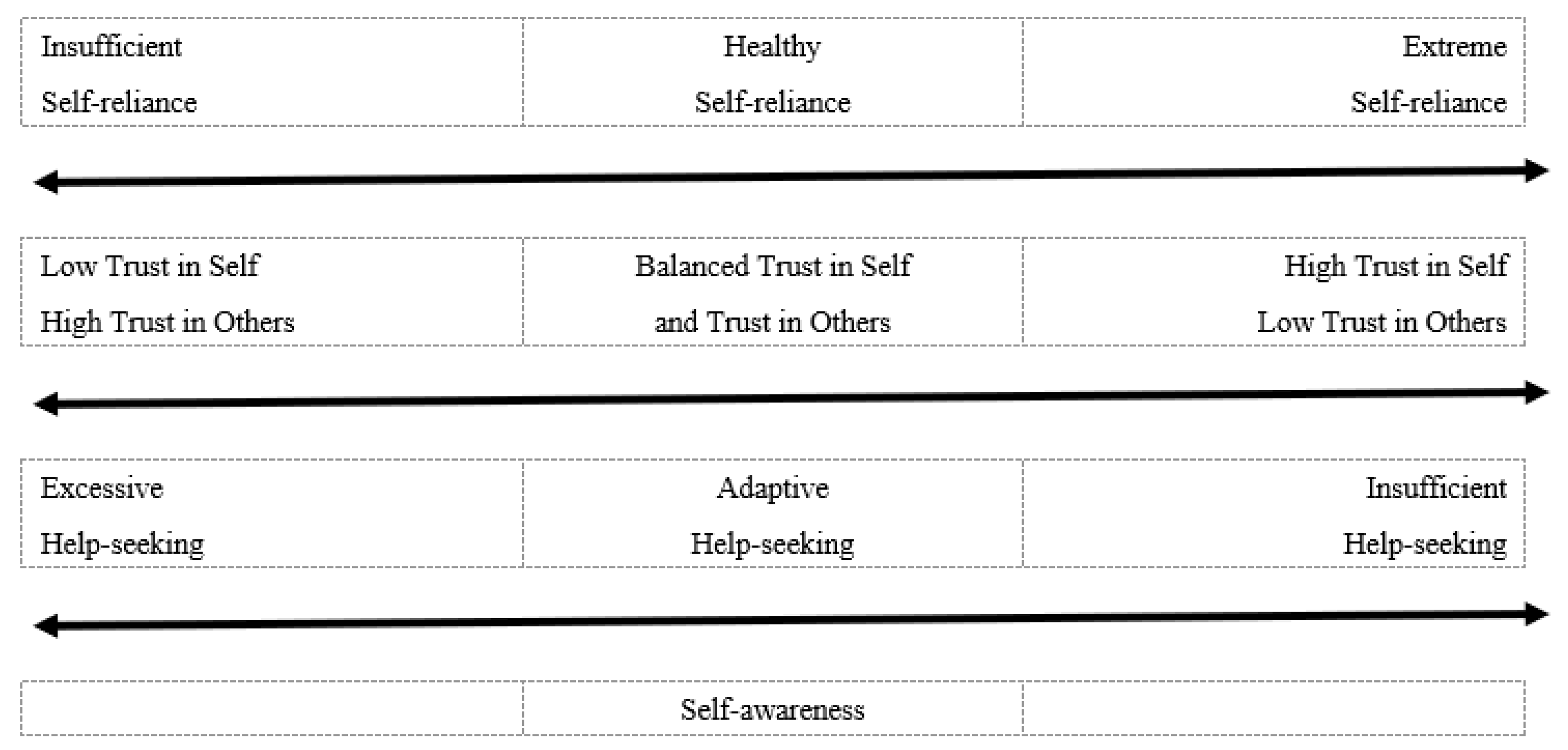

Self-reliance was considered to be both domain dependent (varying depending on context) and on a continuum from insufficient to healthy to extreme self-reliance.

There’s different forms of self-reliance, I guess, in those different domains. And some people can be very self-reliant in a professional domain, but sort of a little bit awkward or… I guess, lacking that calmness and self-knowledge in a social domain. (Participant 27)

This sentiment was repeated throughout the interviews, with many participants describing themselves as self-reliant in some domains and not in others (e.g., financially dependent on others but emotionally self-reliant). At the same time, there was a general regard for the balance that exists between being highly self-reliant and being “un-self-reliant”. The need for maintaining this balance was put down to the usefulness of being able to achieve things on your own and at the same time the usefulness of utilising the resources at your disposal.

Trust

Both Trust in Self and Trust in Others were clearly evident as critical factors. Young people with a high level of Trust in Self were understood to be more self-reliant, more resilient, and more independent. Trust in Self was described as the confidence that you will “rise to the occasion” when faced with adversity, and that you can “make the right decision” and overcome challenges that occur “day to day and over the long term”.

I think that trusting… like trusting yourself is the most important part of self-reliance. Kind of in the name I guess, but you know, to rely on yourself. You need to trust that you are capable of doing the things that you rely on yourself for. (Participant 18)

“Confidence” was the word most frequently used to refer to Trust in Self, but another related theme was that of “resilience”. Participants felt that individuals who had demonstrated greater resilience (i.e., the ability to “bounce back”) would subsequently have a greater Trust in Self because of this ability. Confidence and resilience have in common that they can refer to both how an individual handles challenging life events (e.g., significant stressors in early childhood) and how they cope with responsibilities of living (e.g., paying rent, grocery shopping).

Trust in Others was associated with social support and the availability of trusted personal relationships.

It is important that you know, trust the outside world, that you trust the people that you’re close with, trust the people. I think it is important that trust is important for self-reliance because you need people around you, to encourage you and you need to feel safe around them. (Participant 2)

Trust in Others was considered to be the foundation of self-reliance and a key component of balanced self-reliance, although itself dependant on life experiences. Participants identified that experiences that reduced Trust in Others would lead to an increase in self-reliance and would potentially be associated with extreme self-reliance and an unwillingness to help-seek in the future.

I think, a lack of trust in others or being hurt in previous experiences where you’ve been vulnerable… feeling like you have no really like true friends or no support, I think can kind of make you think, well, actually, we’re all alone in this world and we should just be able to cope with things ourselves. (Participant 3)

In general, there was consensus that Trust in Others is necessary for human survival. Participants recognised that humans are social creatures and that individuals are not able to do everything alone. The importance of “connection” was identified as another theme within Trust in Others. Sometimes this connection with others was identified as an explicit reason for cultivating Trust in Others (i.e., to increase connection) and other times it was seen as a biproduct of needing others. Regardless, it was evidently a positive outcome of having Trust in Others.

I just don’t think that anyone can live by themselves. Like you need support. Like you can be self-reliant to the point where like, you’re not always looking for help, like, you know, you’re taking accountability for like your own life and taking responsibility for whatever you need to do, and mistakes you make, but I don’t think that you can kind of live happily without relying on other people. (Participant 21)

Trust in Self and Trust in Others were not seen as mutually exclusive; a high level of both was the most desirable and most likely to result in healthy self-reliance. One way this was described by participants was in terms of “open mindedness”. Open minded individuals may have a high level of Trust in Self, but they take into consideration the perspectives of others.

If you don’t rely on other people, you will create a situation where you are only thinking with yourself and that can create a funny little echo chamber of one person which is not good for your own thinking. Also, you don’t know everything, you can never know everything, other people might know things that will help you. (Participant 17)

In this quote, there is recognition that consulting others increases one’s Trust in Self. There is also the understanding that a high level of Trust in Self without Trust in Others can lead to cognitive biases and mistakes that are otherwise avoidable. Trust in Self needs to be balanced by Trust in Others.

A high level of Trust in Others and low Trust in Self was attributed to insufficient self-reliance. Participants tended to feel that these individuals had low confidence in their own abilities to problem solve, often because of insufficient opportunities to do so in the past (e.g., being “mollycoddled”) and, therefore, were more likely to have confidence in others than themselves. Conversely, high Trust in Self and low Trust in Others was typically associated with extreme self-reliance. It was felt that these individuals would be less help-seeking, potentially due to insufficient or inadequate help in the past and would hold the belief that it is better to cope with challenges on their own. Low Trust in Self and low Trust in Others was not a predominant theme in any of the interviews.

Self-Awareness

Another relevant theme constructed from responses was “Self-awareness”. In order to be adaptively self-reliant, individuals need to be able to assess their own abilities and needs against the challenges and responsibilities they are met with. Self-awareness here refers to the conscious knowledge of one’s skills, abilities, and limitations in the context of a given situation. Participants considered self-knowledge to be the deciding factor in help-seeking; they felt that if an individual could accurately and consciously reflect on their abilities in context, they would seek help or not as required. Participants felt that truly self-aware individuals would act in their own best interests, although many felt that they did not always have this quality themselves.

If you have this healthy level, maybe it’s like, based off past experience… They might be more in tune with themselves and like past experiences in terms of just like ‘Okay, now I know I need help, or I know I know I can do this by myself because I’ve done this before type thing’. (Participant 10)

Self-awareness was characterised as self-knowledge, boundary setting, accurate assessment of needs in context, emotional awareness and regulation, recognition of limits, and recognition of the need for help. It was not discussed in terms of too much or too little self-awareness.

Help-Seeking

Help-seeking was generally understood by participants as the process of identifying the need for support and taking steps to obtain this support through intentional and interpersonal interaction, as defined in the literature [

32]. Importantly, all participants acknowledged the need for help-seeking in some contexts, and many regarded help-seeking behaviours as a character strength. When asked what they thought of others who asked for help, responses included:

People tended to agree that help-seeking could be a vulnerable and difficult process that may be perceived as weakness by others, but usually reflected non-judgementally on it or felt that to seek help was a sign of strength and a quality to be admired.

There was also recognition of the need for balance: neither being excessively help-seeking nor unwilling to seek help. Excessive help-seeking was associated with insufficient self-reliance and an unwillingness or inability to problem solve on one’s own. It was also associated with high Trust in Others and low Trust in Self. Unwillingness to seek help was associated with extreme self-reliance. This was discussed in relation to insufficient Trust in Others and high levels of Trust in Self.

Many participants acknowledged that they themselves did not seek help as often as they would like to. While there was social stigma associated with being extremely self-reliant and unwilling to seek help, there was also a clearly expressed dislike towards the appearance of being insufficiently self-reliant and excessively help-seeking. When asked “What do you think of people who ask for help?” participants responded:

“Fine. As long as it’s not like everything. But yeah, I think that goes back to the people that like, too much on the ‘not self-reliant’ like spectrum.” (Participant 8)

“Everyone has asked for help throughout their life, so I feel like it is that middle ground where you’re able to be both self-reliant and ask for help.” (Participant 15)

When asked what self-reliant help-seeking might look like, one participant described:

Um, like let’s say you’re making dinner and you’ve prepped pretty much everything, but you can’t reach the wine glasses on the very top shelf and you don’t have a stool or a chair around and you merely are just too short to grab it. You can ask for help. That doesn’t mean you’re not self-reliant on anything, just means you can’t physically reach it. (Participant 19)

There was some disagreement about whether a given action could be both self-reliant and help-seeking, with some identifying help-seeking as a means of self-reliance (i.e., I seek help so that I am able to be self-reliant) and others feeling that individual actions were either help-seeking or self-reliant. The latter agreed that an individual could be overall self-reliant, and still help-seek when necessary. Finally, participants tended to agree that some characteristics would co-occur as shown in

Figure 1: low trust in self, high trust in others, insufficient self-reliance, excessive help-seeking; balanced trust in self and others, healthy self-reliance, healthy help-seeking; high trust in self, low trust in others, extreme self-reliance, insufficient help-seeking.

4. Discussion

This study examined young people’s views about self-reliance, which has been reported as a barrier to seeking help for mental health problems [

4,

32]. Overall, young people agreed that self-reliance was a valuable quality that exists on a continuum and is domain dependent. They understood help-seeking as directly related to self-reliance and as also being on a continuum. There was an understanding that self-reliant individuals must at times seek help. Unwillingness to seek help was associated with extreme self-reliance, and excessive help-seeking was associated with insufficient self-reliance. This suggests that it is extreme self-reliance, not self-reliance per se, that is a barrier to help-seeking [

4,

6,

7].

Both extreme self-reliance and insufficient self-reliance were regarded as undesirable. Future research could develop our understanding of the relative undesirability of each and whether the social perceptions of this undesirability impact help-seeking behaviour. Individuals who are extremely self-reliance may be this way in part because they do not want to be perceived by themselves or others as insufficiently self-reliant. This would accord with previous research about stigmatisation (both self and other) and the impact of this on help-seeking [

4,

5].

Novel to this study, the theme of trust was explored and the relevance of both trust in self and trust in others was revealed. Participants felt that those who were extremely self-reliant would have a low level of trust in others, high trust in self, and a general unwillingness to seek help. The converse was also proposed, whereby those with insufficient self-reliance had low trust in self, high trust in others, and were excessive in their help-seeking behaviours. Establishing a balance along the continuums of trust, help-seeking, and self-reliance was thought to require a level of self-awareness.

Underpinning themes of resilience were also apparent, as well as themes of pride and fears of being a burden. Participants tended to regard resilience as a component of trust in self (i.e., a resilient person has greater confidence in their own abilities). Fears of being a burden and excessive pride in independence were associated with extreme self-reliance. Pride in one’s ability to look after oneself was not always considered negative, but excessive pride (identifying as wholly independent) was considered to be negative it did not allow for trust in others and adaptive self-reliance.

An implication of this study is that a measure of self-reliance is needed that incorporates both adaptive and maladaptive dimensions. It also needs to include trust, in self and in others. For instance, an item such as “I do not trust myself to make decisions” could be used to assess insufficient self-reliance, while an item such as “I do not trust others to be there for me” could assess extreme self-reliance. Other items for measuring extreme self-reliance might be in relation to pride, “I pride myself on doing things on my own” or “I am completely independent”, and fears of imposing, “I worry about being a burden to others”. Healthy self-reliance could be indicated by items such as “I am aware of my own abilities and limitations when taking on difficult tasks”. Notably, in developing a measure, future researchers should avoid using items that contain help-seeking references. A self-reliance measure is needed that can predict help-seeking, rather than be confounded with it. For instance, an item related to self-awareness such as “When I realise I need it, I get help” would measure self-awareness but would also measure help-seeking. This type of tautology in evident in measures used in the current research showing why a better, unconfounded, measure of self-reliance is needed.

A key strength of the current study is that it directly obtained the views of 30 young Australians from diverse backgrounds. The qualitative nature of our approach ensured that their viewpoints were investigated in depth. Our specific focus was to investigate trust as a potential factor in self-reliance, as suggested by the literature [

24]. Other themes were, however, evident in participant responses, which have been reported elsewhere [

33]. The results must be considered in light of the limitations. These include that the views of these young people do not comprise a representative sample, and other young people may have different perspectives. It was also challenging to ask questions in the interviews that probed our interest areas without somewhat priming these issues.

5. Conclusions

This study confirms that self-reliance is relevant to young people’s help-seeking but reveals that a more comprehensive and dimensional approach to conceptualising self-reliance is required. Trust in self and others are important aspects of self-reliance and impact whether or not an individual will engage in help-seeking. Both insufficient and extreme self-reliance were undesirable, but through self-awareness and balancing trust in self with trust in others, healthy self-reliance and adaptive help-seeking could be achieved. These findings may inform future interventions for young people who are unwilling to seek help.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, AM, DR, AI; Methodology, AM, DR, AI; Calidation AM, DR, AI; formal analysis, AM, AI; resources, DR.; writing—original draft preparation, AM, DR.; writing—review and editing, AM,,DR, AI. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Canberra Human Research Ethics Committee (202211903).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Islam, I.; Yunus, F.M.; Isha, S.N.; Kabir, E.; Khanam, R.; Martiniuk, A. The gap between perceived mental health needs and actual service utilization in Australian adolescents. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, E.; Clare, P.J.; Aiken, A.; Boland, V.C.; De Torres, C.; Bruno, R.; Hutchinson, D.; Kypri, K.; Mattick, R.; McBride, N.; et al. Changes in mental health and help-seeking among young Australian adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: a prospective cohort study. Psychol. Med. 2021, 53, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, S.L.; French, R.S.; Henderson, C.; Ougrin, D.; Slade, M.; Moran, P. Help-seeking behaviour and adolescent self-harm: A systematic review. Aust. New Zealand J. Psychiatry 2014, 48, 1083–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulliver, A.; Griffiths, K.M.; Christensen, H. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 113–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGuzman, P.B.; Vogel, D.L.; Bernacchi, V.; A Scudder, M.; Jameson, M.J. Self-reliance, Social Norms, and Self-stigma as Barriers to Psychosocial Help-Seeking Among Rural Cancer Survivors With Cancer-Related Distress: Qualitative Interview Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e33262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radez, J.; Reardon, T.; Creswell, C.; Orchard, F.; Waite, P. Adolescents’ perceived barriers and facilitators to seeking and accessing professional help for anxiety and depressive disorders: a qualitative interview study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 31, 891–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, A.; Rickwood, D.; Bariola, E.; Bhullar, N. Autonomy versus support: self-reliance and help-seeking for mental health problems in young people. Chest 2022, 58, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radez, J.; Reardon, T.; Creswell, C.; Lawrence, P.J.; Evdoka-Burton, G.; Waite, P. Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 30, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickwood, D.J.; Deane, F.P.; Wilson, C.J. When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems? Medical Journal of Australia 2007, 187, S35–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windle, G. What is resilience? A review and concept analysis. Rev. Clin. Gerontol. 2010, 21, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labouliere, C.D.; Kleinman, M.; Gould, M.S. When Self-Reliance Is Not Safe: Associations between Reduced Help-Seeking and Subsequent Mental Health Symptoms in Suicidal Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2015, 12, 3741–3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, D.L.; Wei, M. Adult Attachment and Help-Seeking Intent: The Mediating Roles of Psychological Distress and Perceived Social Support. J. Couns. Psychol. 2005, 52, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, G.M.; Pryce, J.M. “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger”: Survivalist self-reliance as resilience and risk among young adults aging out of foster care. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2008, 30, 1198–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, I.; Appleton, P. To plan or not to plan: The internal conversations of young people leaving care. Qual. Soc. Work. 2015, 15, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenkens, M.; Rodenburg, G.; Schenk, L.; Nagelhout, G.E.; Van Lenthe, F.J.; Engbersen, G.; Sentse, M.; Severiens, S.; Van De Mheen, D. “I Need to Do This on My Own” Resilience and Self-Reliance in Urban At-Risk Youths. Deviant Behav. 2019, 41, 1330–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, P.Y.; Marszalek, J.M. Self-compassion: A potential shield against extreme self-reliance? Journal of Happiness Studies 2019, 20, 971–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickwood D (2022) Help-seeking. Ebook: Understanding Youth Mental Health: Perspectives from Theory and Practice:75.

- Schenk, L.; Sentse, M.; Lenkens, M.; Engbersen, G.; van de Mheen, D.; Nagelhout, G.E.; Severiens, S. At-risk youths’ self-sufficiency: The role of social capital and help-seeking orientation. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 91, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zoonen, K.; Kleiboer, A.; Cuijpers, P.; Smit, J.; Penninx, B.; Verhaak, P.; Beekman, A. Determinants of attitudes towards professional mental health care, informal help and self-reliance in people with subclinical depression. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2015, 62, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, K.M.; Crisp, D.A.; Jorm, A.F.; Christensen, H. Does stigma predict a belief in dealing with depression alone? J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 132, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drioli-Phillips, P.G.; Oxlad, M.; Scholz, B.; LeCouteur, A.; Feo, R. “My Skill Is Putting on a Mask and Convincing People Not to Look Closer”: Silence, Secrecy and Self-Reliance in Men’s Accounts of Troubles-Telling in an Online Discussion Forum for Anxiety. The Journal of Men’s Studies 2021, 30, 230–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.E.; Winefield, H.; Ward, L.; Turnbull, D. Understanding help seeking for mental health in rural South Australia: thematic analytical study. Aust. J. Prim. Heal. 2009, 15, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, A.N.; Alegría, M. Self-Reliance, Mental Health Need, and the Use of Mental Healthcare Among Island Puerto Ricans. Ment. Heal. Serv. Res. 2002, 4, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanagh, D.; Jurcik, T.; Charkhabi, M. How does trust affect help-seeking for Depression in Russia and Australia? Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2021, 68, 1561–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickwood, D.; Deane, F.P.; Wilson, C.J.; Ciarrochi, J. Young people’s help-seeking for mental health problems. Adv. Ment. Heal. 2005, 4, 218–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valerio, M.A.; Rodriguez, N.; Winkler, P.; Lopez, J.; Dennison, M.; Liang, Y.; Turner, B.J. Comparing two sampling methods to engage hard-to-reach communities in research priority setting. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell J (2011) A Realist Approach to Qualitative Research.

- Linneberg, M.S.; Korsgaard, S. Coding qualitative data: a synthesis guiding the novice. Qual. Res. J. 2019, 19, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickwood DJ (2022) Help-seeking. In: Hennessy E, Heary C, Michail M (eds) Understanding Youth Mental Health: Perspectives from Theory and Practice. McGraw Hill Open University Press.

- Ishikawa A, Rickwood DJ, Meadley A (2024) Understanding self-reliance according to emerging adults, including as a barrier to seeking help for mental health problems. Preprint.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).