1. Introduction

Products made from petroleum-derived plastic materials can be found everywhere. However, these products are difficult to recycle at the end of their product life [

1] and are usually not biodegradable [

2]. 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic waste had been produced globally by 2015, most of which ended up in the landfill [

3], negatively affecting the environment. There is a pressing need for more sustainable and environmentally friendly products.

Biomass-fungi composite materials can be used to make products that are traditionally made from petroleum-derived plastic materials. These products have applications in the packaging, construction, and furniture industries [

4,

5,

6]. In the biomass-fungi composite materials, biomass particles (derived from agricultural wastes such as beechwood sawdust and hemp hurd) serve as the substrate and nutrition source for fungi [

7]. The fungi grow through and bind the biomass particles together [

8].

There are many reported studies on biomass-fungi composite materials, including production of composite materials comprising natural fiber, bio-resin, and fungi [

9]; different grades of biomass-fungi composite materials [

10]; fungal-bacterial composite with assembly technique inspired by origami [

11]; and a multiscale computational study of biomass-fungi composite materials [

12]. In these studies, molding-based manufacturing methods were used to produce samples. A 3D printing-based manufacturing method using biomass-fungi composite materials was first reported in 2020 [

13]. 3D printing provides more flexibility in designing complex parts [

10,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Reported studies on 3D printing of biomass-fungi composite materials [

13,

18,

19,

20] cover the effects of biomass-fungi mixture composition on print quality and the effects of waiting time on mechanical properties of printed samples. One reported study demonstrated a robotic manufacturing method [

21]. An organic water-based ink was developed for printing biomass-fungi composite materials [

22]. It was shown that printed samples had improved mechanical properties, self-healing behavior, and adhesion properties. Cardboards were used as substrate material for mycelium cultivation [

23]. Recently, an optimized hydrogel formulation was adopted to print mycelium composite samples [

24].

However, there are no reported studies related to biodegradation of 3D-printed samples from biomass-fungi composite materials. The number of reported studies is limited regarding biodegradation of biomass-fungi composite materials. These studies cover topics related to how biomass-fungi composite materials degraded over time based on the type of biomass materials used in the composite materials [

25,

26]; and biodegradability of molded samples from biomass-fungi composite materials [

27].

This paper will fill the gap in the literature by presenting an experimental study on biodegradation of 3D printed samples from biomass-fungi composite materials. Besides, this paper also provides insights into how biodegradation changes the physical and chemical properties of the biomass-fungi composite materials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Raw Materials

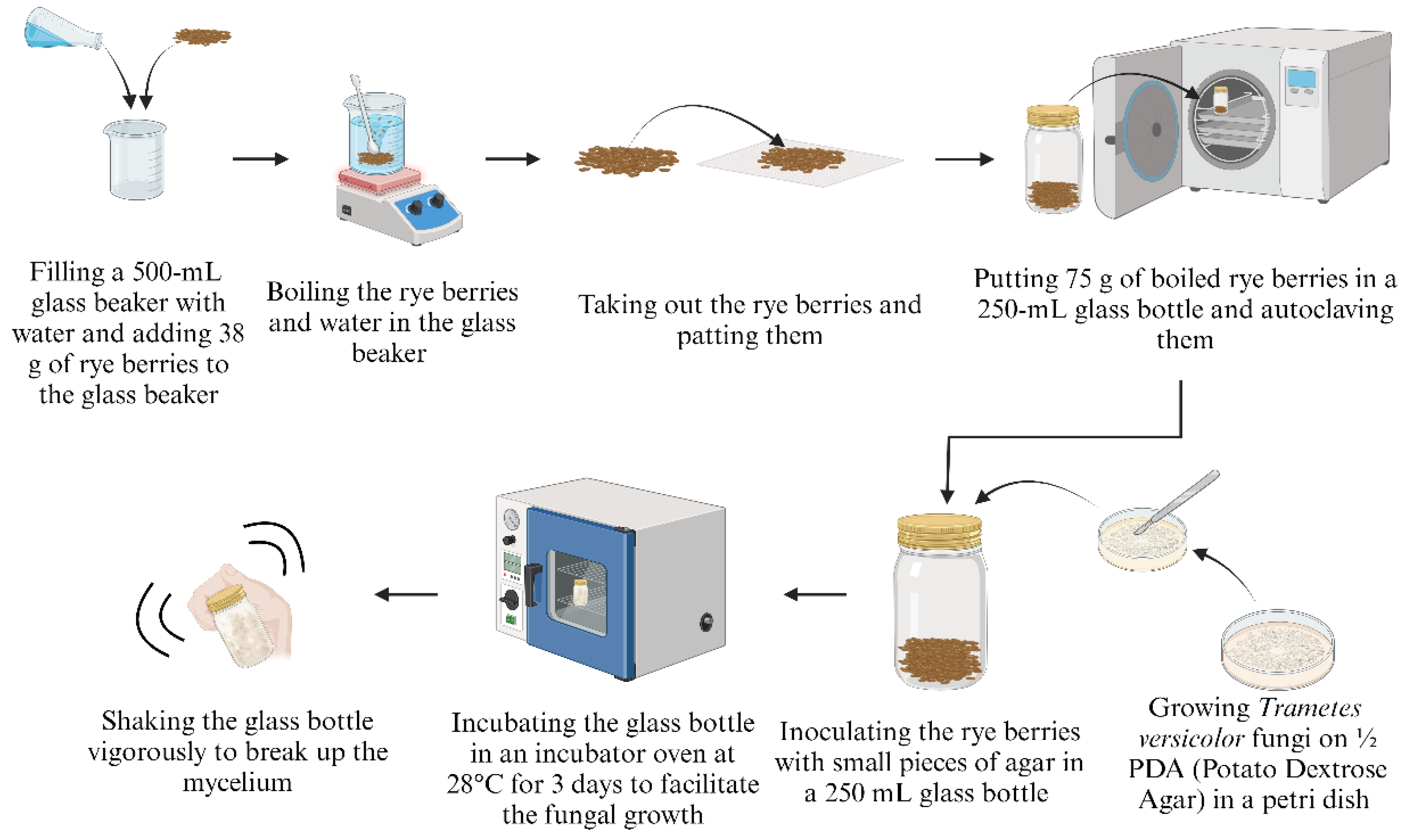

2.1.1. Fungi Growth in Rye Berries

Figure 1 shows the step-by-step procedure of fungal growth in rye berries. Approximately 38 g of dry rye berries were boiled in a 500-mL glass beaker full of water for 30 minutes with continuous manual stirring with a spoon. Afterwards, the rye berries were taken out from the glass beaker and patted with a paper towel to dry them. Subsequently, 75 g of the boiled rye berries were put in a 250-mL glass bottle (MilliporeSigma, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The bottle with the rye berries was autoclaved at 121ºC for 30 minutes in a steam sterilizer (AMSCO LS Small Steam Sterilizers, STERIS, Dublin, Ireland).

Trametes versicolor fungi were put on a petri dish with half-strength PDA (Potato Dextrose Agar that composed of 1000 ml of distilled water, 19.5 g of PDA, and 7.5 g of agar) for one week to prepare the fungi-agar pieces (to be used as the inoculum for Step 3 [

28]. Agar consists of polysaccharides extracted from the cell walls of some species of red algae, is known for its strong gelling properties, and is used in various applications due to its ability to form thermoreversible gels. The detailed procedure for making a half-strength PDA can be found on the internet [

29]. Small fungi-agar pieces and rye berries were added to a 250 mL glass bottle. The bottle was then sealed and shaken to ensure even distribution of the small fungi-agar pieces. The labeled glass bottle was stored in an incubator oven (Fisher Scientific Isothemp 650D Incubator Oven, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, USA) set to 28°C to facilitate fungal growth. After three days, the glass bottle was tightly closed and vigorously shaken to break up the mycelium, facilitating more fungal growth on different parts of rye berries. The glass bottle with rye berries was kept for an additional four days.

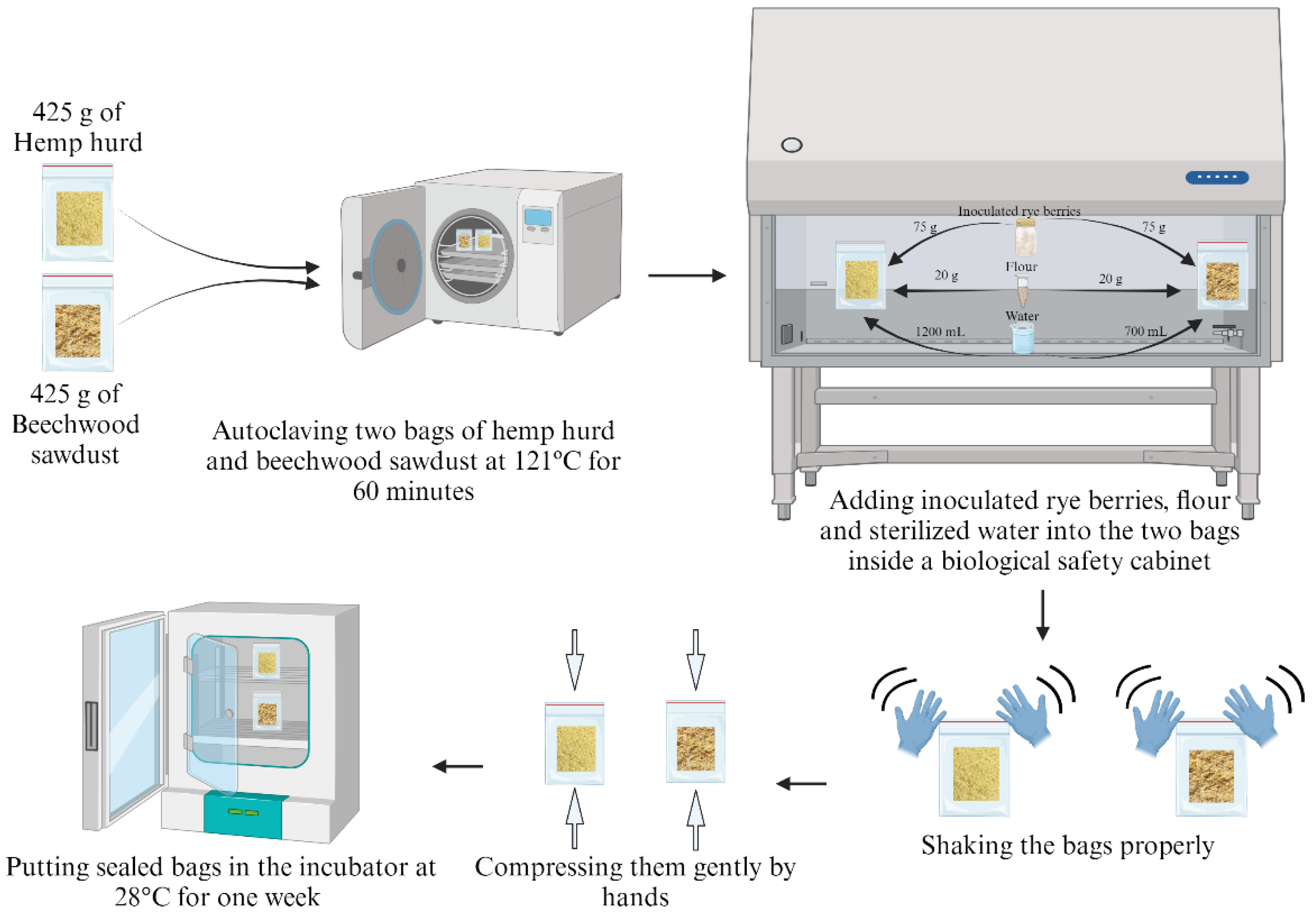

2.1.2. Inoculating Biomass in Bags

Two bags (Mushroom bags, Vabiooth, US) of 5"×8"×20" in size were filled with 425 g of hemp hurd (with average particle size of 2 mm) (Bulk Hemp Warehouse, Las Vegas, NV, USA) in one bag and beechwood sawdust (with average particle size of 0.75 mm) (Culitrade, Schaumburg, IL, USA) in another bag. Then, they were autoclaved in a steam sterilizer (AMSCO LS Small Steam Sterilizers, STERIS, Dublin, Ireland) for 60 minutes at 121ºC. In a biological safety cabinet (Logic+ Class II A2 Biological Safety Cabinet, Labconco Corporation, Kansas City, MO, USA) (which ensures a sterile environment), 75 g of inoculated rye grain spawn was added to each bag (

Figure 2). Additionally, 20 g of wheat flour was added to each of the two bags. Then, due to differences in volume, 1200 mL of sterilized water was added to the bag containing hemp hurd particles, while 700 mL of sterilized water was added to the bag containing beechwood sawdust. Water from a water purifier (LABCONCO, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA, USA) was collected and sterilized with the steam sterilizer. The bags were then sealed, gently shaken to mix the contents, and gently compressed by hand. Finally, the sealed bags were placed in an incubator oven (BLACK+DECKER TO3000G 6-Slice Convection Countertop Toaster Oven, Black & Decker, Towson, MD, USA) set to 28°C for one week. These biomass-fungi materials became ready for preparation of mixtures to be used in printing experiments.

2.2. Preparation of Sodium Alginate Solution and Calcium Chloride Crosslinking Solution

In this experiment, sodium alginate (NaC

6H

7O

6) was used as a hydrogel, and calcium chloride (CaCl

2) as a crosslinking solution. The 1% sodium alginate solution and the 5% calcium chloride crosslinking solution were prepared by following the procedures described in a published paper [

30]. The sodium alginate solution was used during the printable mixture preparation stage. After preparation, the crosslinking solution was kept in an autoclavable plastic box (Flex-A-Top, LA Container, Yorba Linda, CA, USA). More information about crosslinking, roles of sodium alginate and calcium chloride is provided in other papers [

31,

32].

2.3. Preparation of Mixtures for 3D Printing

First, 50 g of biomass-fungi material (with either hemp hurd particles or beechwood sawdust), 20 g of wheat flour, 100 mL of 1% sodium alginate solution, and 100 mL of autoclaved water were added into the mixing container of a commercial mixer (NutriBullet PRO: Capital Brands, Los Angeles, CA, USA). An intermittent mixing mode with mixing time of 30 seconds was used during the mixing process. Afterward, 10 g of psyllium husk powder (Now Foods Psyllium Husk Powder, 12 Ounce, Now Food, Bloomingdale, IL, USA) was added to the mixture using a spatula. After a waiting time of 30 minutes, the mixture became ready for printing.

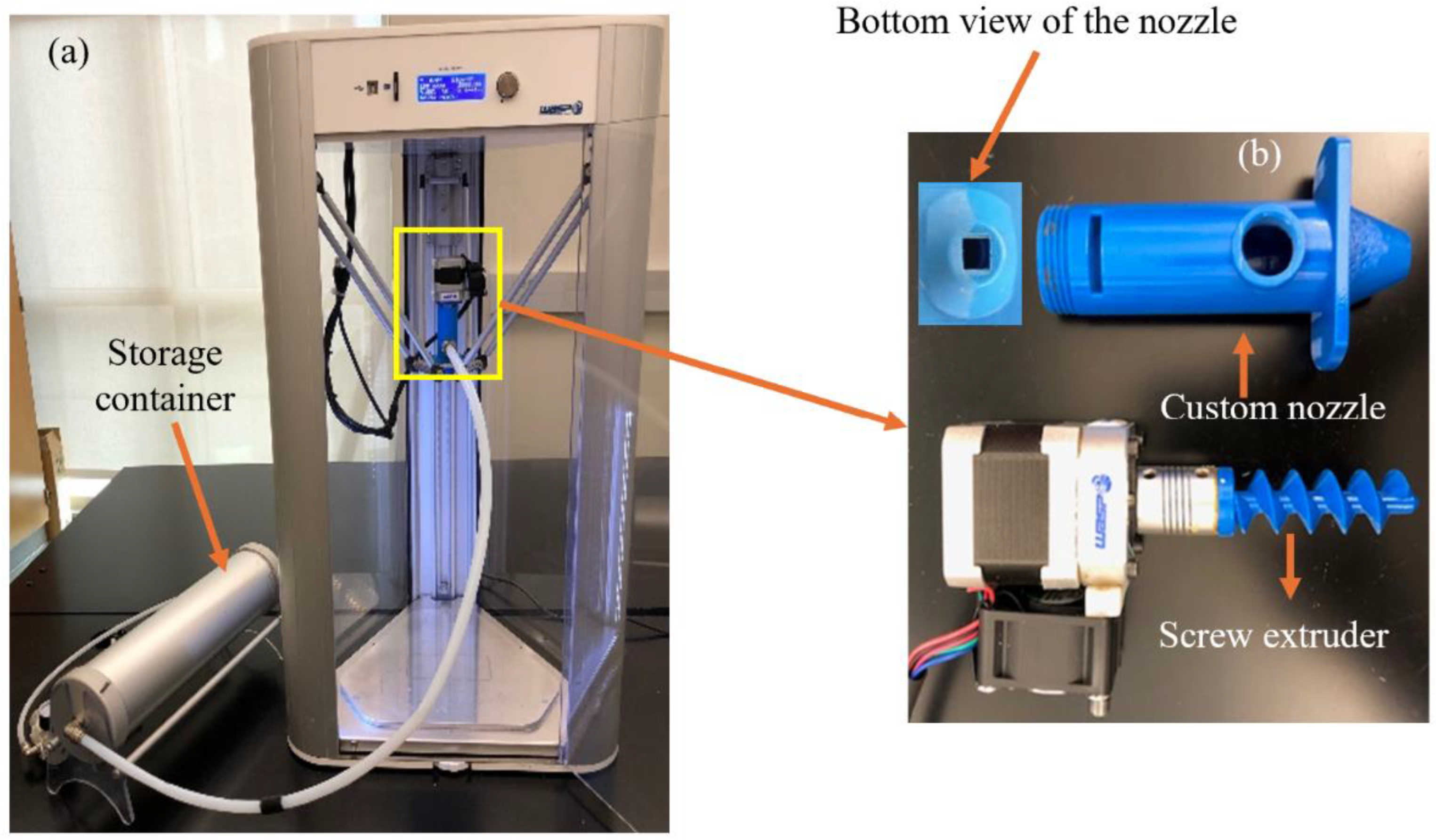

2.4. Preparation of Samples by Extrusion Based 3D Printing

The printer (Delta 2040: WASP, Massa Lombarda RA, Italy) used is shown in

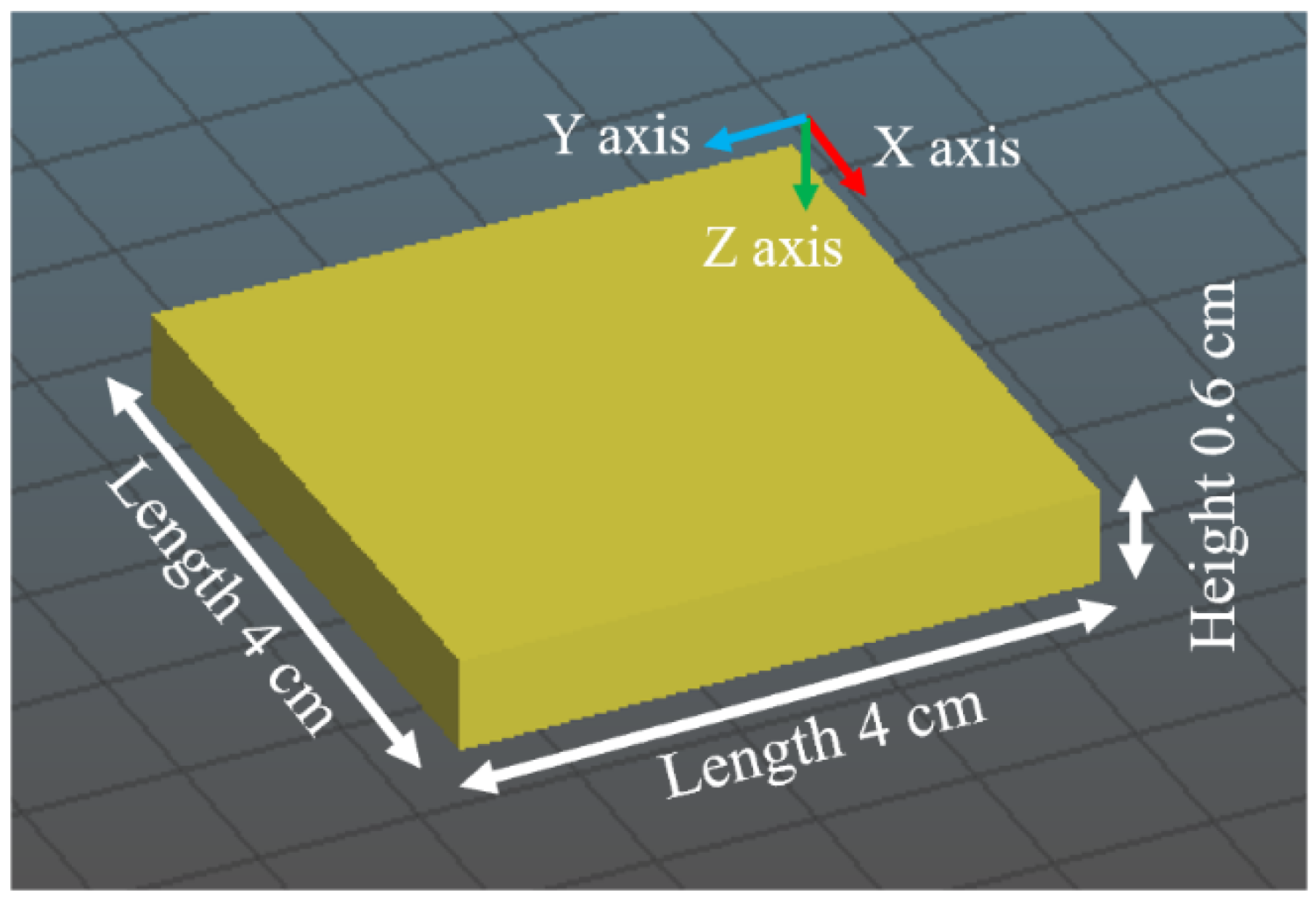

Figure 3. The printer had a motor, customed nozzle (with an opening of 6 mm × 6 mm), and screw extruder. A storage container (with the volume of 3 L) that was used to store the mixture was connected to the extruder via a pipe. Printing pressure (used to push the mixture through the nozzle) was achieved by an air compressor (Kobalt 4.3-gallon Electric Twin Stack Quiet Air Compressor: Kobalt, Mooresville, NC, USA). The pressure was set at 2.6 bar to print the hemp hurd mixture and 3.1 bar to print the beechwood sawdust mixture. The samples had dimensions of 4 cm × 4 cm × 0.6 cm (

Figure 4) and were designed using SOLIDWORKS (version 2023, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). A G-code was created using the Slic3r software (version 1.3.0.0). The following printing parameters were used to generate the G-code: extruder speed = 15 mm/s, infill density = 30%, and infill type = concentric. Then, the G-code was imported to Delta WASP 2040 3D printer via an SSD (Solid-State Drive) card. The printed samples were soaked in a 5% calcium chloride crosslinking solution for 1 minute for crosslinking.

Figure 5 shows the after soaking condition of the printed samples. A total of 8 samples were printed in the experiment (4 for hemp hurd and 4 for beechwood sawdust). The printed samples were stored for five days in a location shielded from direct sunlight for secondary colonization. Afterwards, they were put in an oven at 120ºC for four hours to kill all the fungi in the samples. These samples became ready for the soil burial test.

2.5. Soil Burial Test

Soil burial tests were used in many reported studies on degradation of several types of materials [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38], including hemp hurd, beechwood sawdust, and wheat straw. In some of these reported studies [

27], the procedure described in ISO 20200 was followed. ISO 20200 defines a method for determining the disintegration of plastic and other materials under laboratory conditions [

39]. This study follows the ISO 20200 standard for the soil burial test.

The step-by-step procedure of the soil burial test used in this study is shown in

Figure 6. The soil (Miracle Gro Potting Mix, Scotts Miracle-Gro Company, Marysville, Ohio) was purchased from a local Walmart store. The soil contained green waste, general fertilizer, and brown waste (pine barks). After sieving with a 2-mm mesh strainer (Adamas-Beta, Shanghai, China), the soil was kept in a plastic storage box (Sterilite 12-Quart Plastic Storage Boxes, Townsend, MA, USA) with two openings of 2.3" × 2" in size on the sides of the box (

Figure 7 (a)). The pH level of the soil wad in the range of 6.0 to 7.0. The weight of the samples was measured with a balance scale (U.S. Solid, Cleveland, OH, USA). Then the samples were wrapped in a small garden net (Garden Netting Pest Barrier: Ultra Fine 10' x 20' Bug Netting for Garden Protection, The Garden Taylor, Tunbridge Wells, Kent, UK), and subsequently buried in the soil. The garden nets were made from high-density polyethylene. Six garden nets of 10 cm × 10 cm were used for wrapping six printed samples (one net for one sample). One of the 4 printed beechwood sawdust samples and one of the 4 printed hemp hurd samples were used as control samples in the experiment and kept on the top of the plastic storage boxes. Afterwards, the plastic storage boxes were put in the environment chamber (

Figure 7(b)). The temperature of the environmental chamber was maintained at 25ºC with a relative humidity of 48%. Every week, the plastic storage boxes were taken out from the environment chamber, the samples in the garden nets were taken out from the soil, and samples were removed from the garden nets. Hands were thoroughly sanitized, gloves (Vinyl Symmax Exam Gloves, Zibo, China) were worn, and samples were taken out from the nets carefully.

2.6. Weight Measurement

Weight measurement took place every week. The weight change (in percentage) was the difference between

(initial weight of the sample) and

(weight of the sample after a certain period of time in the environmental chamber). It was calculated from Equation (1).

The average weight change for the samples were calculated by averaging the weight changes of the 3 samples.

2.7. Pictures Taken Using iPhone

Pictures were taken for each of the samples with an iPhone 14 Pro camera (iPhone 14 Pro, Apple, Cupertino, CA, USA). For the control samples, pictures were taken only before and after the soil burial test. Afterwards, the samples were put back into the environment chamber.

2.8. Micrographs Taken Using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

A scanning electron microscope (SNE-4500M Plus, NanoImages, Lafayette, CA, USA) was used to take micrographs of the samples. SEM images of the samples were taken before putting them into the soil and after the soil burial test.

2.9. Observations Using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

To find out different types of functional groups in the printed samples, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) with an Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) mode was carried out in a spectrophotometer (iD7 ATR with Nicolet™ iS™ 5 Spectrometer, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The samples for FTIR observation were small pieces of the sample after 3 months of the soil burial test. Each FTIR sample was put on the sample holder of the spectrophotometer. A spectral range of 500 – 4000 cm-1 and a resolution of 16 cm-1 were used.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Visual Observations of Samples

Figure 8 shows the pictures of samples after each month of the soil burial test. After one month, no samples showed any sign of disintegration. After two months, both types of the hemp hurd and beechwood sawdust samples became more darkened than the previous month. After three months, disintegration was observed in the beechwood sawdust samples, but not in the hemp hurd samples.

3.2. Weight Change

Figure 9 shows the weight change data starting from week 5. Within a month of the soil burial test, all the samples did not have noticeable weight change, instead, the weight increased for both types of test samples. This weight increase was probably due to microbe growth on the sample surfaces and the samples’ moisture absorption from soil. Weight change gradually increased from week 5 to week 13. After three months of the soil burial test, weight change was 33.3% for the hemp hurd samples and 29.9% for the beechwood sawdust samples. The result of biodegradation for the hemp hurd test samples is congruent with the reported study by Wylick et al. [

27], who showed that hemp hurd test samples degraded 36.05% after week 12 of the soil burial experiment. The weight of control samples remained constant for both types of samples, which is also agreed with the results obtained by Wylick et al. [

27]. The soil burial test conducted by different research groups throughout one to four months revealed that the weight change for the biomass-fungi composite samples varied between 13.19% to 70% [

25,

26,

40]. However, the speed at which substances break down can differ depending on various factors like what they are made of, how strong they are, their physical and chemical traits, the presence of microorganisms like bacteria and fungi, and how well they can withstand exposure to the different types of environments [

40]. Overall, the weight change falls within the standard range of biodegradable materials [

41], which implies that the 3D-printed biomass-fungi composite materials are environmentally friendly.

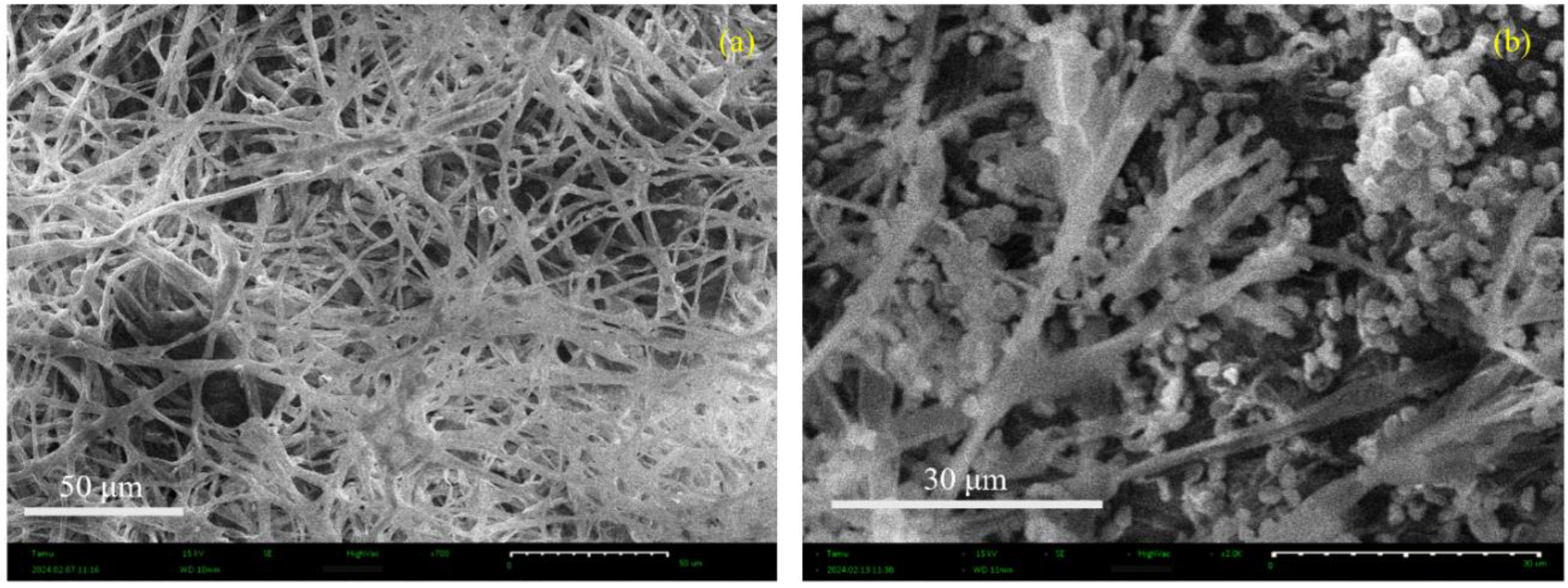

3.3. SEM Micrographs

Surface features of the beechwood sawdust samples before and after the soil burial test were captured by SEM micrographs.

Figure 10 (a) shows that the colonization of the mycelium into the substrate was not homogenous. The hyphae look very compact and have thread-like structures. The diameters of the filaments depend on the types of nutrients present in the substrate [

42]. Since beechwood sawdust is lignocellulosic in nature, the fungal hyphae can grow well in these substrates [

42].

Figure 10 (b) shows how the morphological changes happened after the soil burial test (biodegradation). Many microorganisms are involved in the biodegradation of lignocellulosic substrates, and soil fungi are one of them [

43]. The small ball-like structures are Zygospores [

44], which belong to Zygomycota fungal clones. This species is responsible for degrading the composite samples after the soil burial test [

45]. During the soil burial test, the thread-like structures were degraded with time, which resulted in a decreased weight for the composite samples.

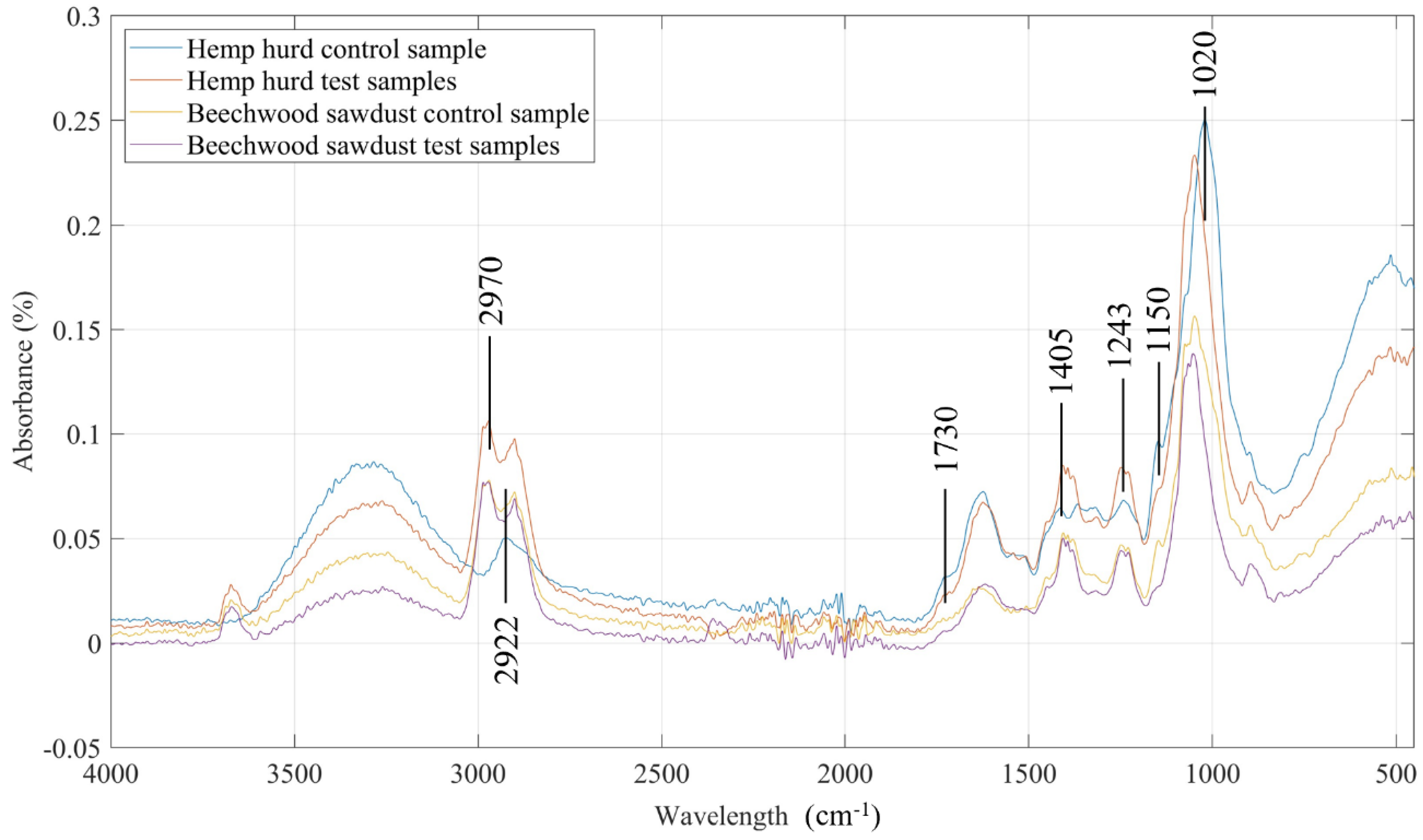

3.4. FTIR Analysis

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy technique is extensively used to find out what solid, liquid, or gas is present in a substance [

46]. FTIR spectroscopy was used to detect any changes in the printed composite samples before and after the soil burial test. Both hemp hurd and beechwood sawdust samples showed numerous peaks in the 3500- 3000 cm

-1 range (

Figure 11 before and after the soil burial test. It is highly possible that the O-H and N-H functional groups are present in this region [

38,

47,

48]. The bands noticed from the 3000-2800 cm

-1 range come from the stretching vibration of symmetric and asymmetric -CH2 (~2970 cm

-1) for all the composite samples except the hemp hurd control sample. A peak was observed around 2922 cm

-1 in all four types of samples (hemp hurd samples, hemp hurd control sample, beechwood sawdust samples, and the beechwood sawdust control sample), which is indicative of chitin (C-H stretching) [

49]. The amide Ⅰ band was overserved from the 1700-1600 cm

-1 range (~1730 cm

-1), amide Ⅱ and Ⅲ bands from 1575-1300 cm

-1 range (~1405 cm

-1); these three bands are indicative of proteins. Nucleic acids (1260-1245 cm

-1) and polysaccharides (1200-900 cm

-1) were also observed in all four types of samples at 1243 cm

-1 and 1150 cm

-1wavelength respectively [

38]. Moreover, C-O stretch in hemicelluloses and cellulose was observed at 1020 cm

-1 wavelengths [

48]. From the peaks of the absorption intensity, it is evident that after the biodegradation of the composite samples, the amount of substances in the sample reduced [

48,

49,

50].

4. Conclusions

This paper presents a preliminary experimental study on biodegradation of 3D-printed samples from biomass-fungi composite materials. After three months of the soil burial test, weight change was 33% for the hemp hurd samples and 30% for the beechwood sawdust samples. This means that the hemp hurd samples degraded more than the beechwood sawdust samples. SEM micrographs showed how the surface morphology of these samples changed after the soil burial test. Among different types of soil microbes, zygospores of Zygomycota were abundantly present on the surface of the test samples, responsible for the biodegradation of the test samples. FTIR spectroscopy results showed that the amount of substances in the test samples changed after the soil burial test.

Future studies can be conducted using a full factorial design of experiments, more fungi strains, and more types of biomass materials. Effects of crosslinking solution on biodegradation of biomass-fungi composite materials can also be investigated. Moreover, in-depth chemical analyses such as XPS (X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy) and mechanical analyses such as compressive tests of the printed samples can provide more insight.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M.A., C.O.B., A.M.R., J.H., B.D.S., and Z.P.; methodology, Y.M.A., C.O.B., and A.M.R.; software, Y.M.A.; validation, Y.M.A., C.O.B., A.M.R., and F.K.; formal analysis, Y.M.A.; investigation, Y.M.A., C.O.B., and A.M.R.; resources, Z.P., B.D.S., and Chukwuzubelu Okenwa Ufodike; data curation, Y.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.M.A., and C.O.B.; writing—review and editing, Y.M.A., Z.P., C.O.B., A.M.R., and B.D.S.; visualization, Y.M.A.; supervision, Z.P., and B.D.S.; project administration, Z.P., and B.D.S.; funding acquisition, Z.P., and B.D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 2308575.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the analyzed data that support the findings of this study are available within the article and others are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of undergraduate students Emma Moser, Daniel Mendez Castro, and Roger McGrath, Industrial and Systems Engineering, Texas A&M University, College Station and Abu Shoaib Saleh, Department of Multidisciplinary Engineering, Texas A&M University, College Station for their assistance in the experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this study.

References

- M. Akter, M. H. M. Akter, M. H. Uddin, and I. S. Tania, "Biocomposites based on natural fibers and polymers: A review on properties and potential applications," Journal of Reinforced Plastics and Composites, vol. 41, no. 17-18, pp. 705-742, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Harding, T. Gounden, and S. Pretorius, "“Biodegradable” plastics: a myth of marketing?," Procedia manufacturing, vol. 7, pp. 106-110, 2017.

- R. Geyer, J. R. Jambeck, and K. L. Law, "Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made," Sci Adv, vol. 3, no. 7, p. e1700782, Jul 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. Grimm and H. A. B. Wosten, "Mushroom cultivation in the circular economy," Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, vol. 102, no. 18, pp. 7795-7803, Sep 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. A. Holt, G. McIntyre, D. Flagg, E. Bayer, J. D. Wanjura, and M. G. Pelletier, "Fungal Mycelium and Cotton Plant Materials in the Manufacture of Biodegradable Molded Packaging Material: Evaluation Study of Select Blends of Cotton Byproducts," Journal of Biobased Materials and Bioenergy, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 431-439, 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. Bhardwaj, A. M. Rahman, X. Wei, Z. Pei, D. Truong, M. Lucht, and N. Zou, "3D Printing of Biomass–Fungi Composite Material: Effects of Mixture Composition on Print Quality," Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, vol. 5, no. 4, p. 2, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Bonfante and A. Genre, "Mechanisms underlying beneficial plant-fungus interactions in mycorrhizal symbiosis," Nat Commun, vol. 1, no. 1, p. 48, Jul 27 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Jones, A. Mautner, S. Luenco, A. Bismarck, and S. John, "Engineered mycelium composite construction materials from fungal biorefineries: A critical review," Materials & Design, vol. 187, p. 108397, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Jiang, D. Walczyk, G. McIntyre, R. Bucinell, and G. Tudryn, "Manufacturing of biocomposite sandwich structures using mycelium-bound cores and preforms," Journal of Manufacturing Processes, vol. 28, pp. 50-59, 2017/08/01/ 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Ghazvinian, P. Farrokhsiar, F. Vieira, J. Pecchia, and B. Gursoy, "Mycelium-based bio-composites for architecture: Assessing the effects of cultivation factors on compressive strength," Mater. Res. Innov, vol. 2, pp. 505-514, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. M. McBee, M. Lucht, N. Mukhitov, M. Richardson, T. Srinivasan, D. Meng, H. Chen, A. Kaufman, M. Reitman, C. Munck, D. Schaak, C. Voigt, and H. H. Wang, "Engineering living and regenerative fungal-bacterial biocomposite structures," Nat Mater, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 471-478, Apr 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Islam, G. Tudryn, R. Bucinell, L. Schadler, and R. C. Picu, "Morphology and mechanics of fungal mycelium," Sci Rep, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 13070, Oct 12 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Bhardwaj, J. Vasselli, M. Lucht, Z. Pei, B. Shaw, Z. Grasley, X. Wei, and N. Zou, "3D Printing of Biomass-Fungi Composite Material: A Preliminary Study," Manufacturing Letters, vol. 24, pp. 96-99, 2020/04/01/ 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhang, Y. Li, W. Kang, X. Liu, and Q. Wang, "Current advances and future perspectives of additive manufacturing for functional polymeric materials and devices," SusMat, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 127-147, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Attias, O. Danai, T. Abitbol, E. Tarazi, N. Ezov, I. Pereman, and Y. J. Grobman, "Mycelium bio-composites in industrial design and architecture: Comparative review and experimental analysis," Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 246, p. 119037, 2020. [CrossRef]

- B. Modanloo, A. Ghazvinian, M. Matini, and E. Andaroodi, "Tilted Arch; Implementation of Additive Manufacturing and Bio-Welding of Mycelium-Based Composites," Biomimetics (Basel), vol. 6, no. 4, p. 68, Nov 30 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Sydor, A. Bonenberg, B. Doczekalska, and G. Cofta, "Mycelium-Based Composites in Art, Architecture, and Interior Design: A Review," Polymers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 1, p. 145, Dec 31 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Bhardwaj, A. M. Rahman, X. Wei, Z. Pei, D. Truong, M. Lucht, and N. Zou, "3D Printing of Biomass–Fungi Composite Material: Effects of Mixture Composition on Print Quality," Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, vol. 5, no. 4. . https://doi.org/. [CrossRef]

- M. Rahman, A. Bhardwaj, Z. Pei, C. Ufodike, and E. Castell-Perez, "The 3D Printing of Biomass– Fungi Composites: Effects of Waiting Time after Mixture Preparation on Mechanical Properties, Rheological Properties, Minimum Extrusion Pressure, and Print Quality of the Prepared Mixture," Journal of Composites Science, vol. 6, no. 8, p. 237, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Malik, J. Hagopian, S. Mohite, C. Lintong, L. Stoffels, S. Giannakopoulos, R. Beckett, C. Leung, J. Ruiz, M. Cruz, and B. Parker, "Robotic Extrusion of Algae-Laden Hydrogels for Large-Scale Applications," Glob Chall, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 1900064, Jan 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Elsacker, E. Peeters, and L. De Laet, "Large-scale robotic extrusion-based additive manufacturing with living mycelium materials," Sustainable Futures, vol. 4, p. 100085, 2022/01/01/ 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Soh, J. H. Teoh, B. Leong, T. Xing, and H. Le Ferrand, "3D printing of mycelium engineered living materials using a waste-based ink and non-sterile conditions," Materials & Design, vol. 236, p. 112481, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Mohseni, F. R. Vieira, J. A. Pecchia, and B. Gursoy, "Three-Dimensional Printing of Living Mycelium-Based Composites: Material Compositions, Workflows, and Ways to Mitigate Contamination," Biomimetics (Basel), vol. 8, no. 2, p. 257, Jun 14 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Lin, A. Taghizadehmakoei, L. Polovina, I. McLean, J. C. Santana-Martinez, C. Naese, C. Moraes, S. J. Hallam, and J. Dahmen, "3D Bioprinting of Food Grade Hydrogel Infused with Living Pleurotus ostreatus Mycelium in Non-sterile Conditions," ACS Appl Bio Mater, vol. 7, no. 5, pp. 2982-2992, 2024. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zimele, I. Irbe, J. Grinins, O. Bikovens, A. Verovkins, and D. Bajare, "Novel Mycelium-Based Biocomposites (MBB) as Building Materials," Journal of Renewable Materials, vol. 8, no. 9, pp. 1067--1076, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Ly and W. Jitjak, "Biocomposites from agricultural wastes and mycelia of a local mushroom, Lentinus squarrosulus (Mont.) Singer," Open Agriculture, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 634-643, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Van Wylick, E. Elsacker, L. L. Yap, E. Peeters, and L. De Laet, "Mycelium composites and their biodegradability: An exploration on the disintegration of mycelium-based materials in soil," 2022 2022, vol. 1: Trans Tech Publ, pp. 652-659. [CrossRef]

- J. G. Vasselli, H. Hancock, C. O. Bedsole, E. Kainer, T. M. Chappell, and B. D. Shaw, "The conidial coin toss: A polarized conidial adhesive in Colletotrichum graminicola," Fungal Genet Biol, vol. 163, p. 103747, Nov 2022. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://wiki.bugwood.org/Acid_potato_dextrose_agar_(half_strength) (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- A. M. Rahman, C. O. Bedsole, Y. M. Akib, J. Hamilton, T. T. Rahman, B. D. Shaw, and Z. Pei, "Effects of Sodium Alginate and Calcium Chloride on Fungal Growth and Viability in Biomass-Fungi Composite Materials Used for 3D Printing," Biomimetics (Basel), vol. 9, no. 4, p. 251, Apr 20 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen, A. Abdullayev, M. F. Bekheet, B. Schmidt, I. Regler, C. Pohl, C. Vakifahmetoglu, M. Czasny, P. H. Kamm, V. Meyer, A. Gurlo, and U. Simon, "Extrusion-based additive manufacturing of fungal-based composite materials using the tinder fungus Fomes fomentarius," Fungal Biol Biotechnol, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 21, Dec 21 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Liu, A. K. Bastola, and L. Li, "A 3D Printable and Mechanically Robust Hydrogel Based on Alginate and Graphene Oxide," (in eng), ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, vol. 9, no. 47, pp. 41473-41481, Nov 29 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. Sanhawong, P. Banhalee, S. Boonsang, and S. Kaewpirom, "Effect of concentrated natural rubber latex on the properties and degradation behavior of cotton-fiber-reinforced cassava starch biofoam," Industrial Crops and Products, vol. 108, pp. 756-766, 2017. [CrossRef]

- I. R. Oliveira, F. R. Cunha, and C. T. Andrade, "Evaluation of biodegradability of different blends of polystyrene and starch buried in soil," 2010, vol. 290: Wiley Online Library, 1 ed., pp. 115-120. [CrossRef]

- M. Mazibuko, J. Ndumo, M. Low, D. Ming, and K. Harding, "Investigating the natural degradation of textiles under controllable and uncontrollable environmental conditions," Procedia Manufacturing, vol. 35, pp. 719-724, 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Mattos, P. H. G. de Cademartori, T. V. Lourençon, D. A. Gatto, and W. L. E. Magalhães, "Biodeterioration of wood from two fast-growing eucalypts exposed to field test," International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, vol. 93, pp. 210-215, 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Kumar and J. P. Kruth, "Composites by rapid prototyping technology," Materials & Design, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 850-856, 2010/02/01/ 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Haneef, L. Ceseracciu, C. Canale, I. S. Bayer, J. A. Heredia-Guerrero, and A. Athanassiou, "Advanced Materials From Fungal Mycelium: Fabrication and Tuning of Physical Properties," Sci Rep, vol. 7, no. 1, p. 41292, Jan 24 2017. [CrossRef]

- ISO 20200:2015. "ISO: Global standards for trusted goods and services." ISO. https://www.iso.org/standard/63367.html (accessed ). 07 June.

- W. Aiduang, K. Jatuwong, P. Jinanukul, N. Suwannarach, J. Kumla, W. Thamjaree, T. Teeraphantuvat, T. Waroonkun, R. Oranratmanee, and S. Lumyong, "Sustainable Innovation: Fabrication and Characterization of Mycelium-Based Green Composites for Modern Interior Materials Using Agro-Industrial Wastes and Different Species of Fungi," Polymers (Basel), vol. 16, no. 4, p. 550, Feb 18 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Kjeldsen, M. Price, C. Lilley, E. Guzniczak, and I. Archer, "A review of standards for biodegradable plastics.

- N. I. Nashiruddin, K. S. Chua, A. F. Mansor, R. A. Rahman, J. C. Lai, N. I. Wan Azelee, and H. A. El Enshasy, "Effect of growth factors on the production of mycelium-based biofoam," Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, vol. 24, pp. 351-361, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Rajeshkumar, P. S. Kumar, M. Ramesh, M. R. Sanjay, and S. Siengchin, "Assessment of biodegradation of lignocellulosic fiber-based composites - A systematic review," Int J Biol Macromol, vol. 253, no. Pt 5, p. 127237, Dec 31 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. J. Volk, "Fungi," in Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, S. A. Levin Ed. New York: Elsevier, 2001, pp. 141-163.

- B.-Y. Tian, Q.-G. Huang, Y. Xu, C.-X. Wang, R.-R. Lv, and J.-Z. Huang, "Microbial community structure and diversity in a native forest wood-decomposed hollow-stump ecosystem," World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 233-240, 2010/02/01 2009. [CrossRef]

- P. R. Griffiths, "Fourier transform infrared spectrometry," Science, vol. 222, no. 4621, pp. 297-302, Oct 21 1983. [CrossRef]

- R. Aravindhan, B. Madhan, J. R. Rao, B. U. Nair, and T. Ramasami, "Bioaccumulation of chromium from tannery wastewater: an approach for chrome recovery and reuse," Environ Sci Technol, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 300-6, Jan 1 2004. [CrossRef]

- B. Mohebby, "Attenuated total reflection infrared spectroscopy of white-rot decayed beech wood," International biodeterioration & biodegradation, vol. 55, no. 4, pp. 247-251, 2005.

- A. Rigobello and P. Ayres, "Compressive behaviour of anisotropic mycelium-based composites," Sci Rep, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 6846, Apr 27 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Stevulova, J. Cigasova, A. Estokova, E. Terpakova, A. Geffert, F. Kacik, E. Singovszka, and M. Holub, "Properties Characterization of Chemically Modified Hemp Hurds," Materials (Basel), vol. 7, no. 12, pp. 8131-8150, Dec 17 2014. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).