Submitted:

22 August 2024

Posted:

25 August 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Colonial Context of Hepatitis

Institutional Racism in Canadian Healthcare

Hepatitis C

The Colonial Legacy and Transmission of HCV

Access to Testing and Treatment

Colonial Influence on Experience of Hepatitis

Strategies for Change through Promising Practice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| ISC | Indigenous Services Canada |

| PWUD | Person who use drugs |

| SVR | Sustained Virological Response |

Glossary

| Child welfare system / Foster Care / 60’s Scoop / Millennium Scoop | The current and past government run systems forcibly removing Indigenous children from their families, homes, and communities and placing them in non-Indigenous settings. Severing connection to culture, language and land and forcing assimilation and inter-generational trauma through discrimination, racism, neglect, physical, sexual, and emotional abuse (1). |

| Colonization | The acts of European entities rooted in religion, politics, economics and power used to subjugate and exploit Indigenous People in the process of settling Canada (1). |

| Decolonize | The undoing or divesting of colonial power of culture, languages, education, health and bureaucracy (1). |

| Indian Act of 1876 | Federal legislation regulating Indigenous People’s ability to live and access land, status, education, health supports and other aspects of daily life. Numerous amendments, revisions and re-enactments since the original document but still continues to impact all aspects of life for Indigenous People in what is now Canada (2). |

| Indigenous | Inclusive reference to the First Nation (Indigenous People who are not Inuit or Metis), Inuit (Indigenous People of the arctic and sub-arctic areas of Canada) and Metis (descendants of unions between Indigenous People and European fur traders creating a unique cultural entity) Peoples within what is known today as Canada (1). |

| Intergenerational Trauma | Past and ongoing traumatic events related to the colonizing of Canada inform the transfer of thoughts, behaviours, coping mechanisms, and health status with Indigenous People (1). |

| Knowledge Keeper | Trusted and respected Indigenous community member recognized for their experiences, the knowledge they have received, and their willingness to share these with others (1). |

| Reserve | Tracts of land set aside for use by specified Indigenous group of people, but the Crown or federal government retains title to this land. Historically specific rules controlled passage to and from these lands (2). |

| Residential School | Institutions set up by religious entities with government funding to forcibly house Indigenous children who were removed from their families, homes and communities and sometimes taken across the country. These schools took over 150,000 children age 5-16 years and focused on manual labor skills versus educational excellence. Over 6,000 children died or disappeared from these schools (2). |

| Two-Eyed Seeing | Approach to learning and understanding by seeing from one eye with Indigenous ways of knowing and from the other eye with Western ways of knowing (1) |

| Treaty | An agreement, recognized constitutionally between First Nations and the government of Canada, outlining obligations in return for access to land (2). |

| Truth and Reconciliation Commission and Calls to Action | The commission (2008-2015) was an element of the settlement for residential school survivors, and their families and communities, and established 94 calls to action to be taken by the government as steps to rectify harms and work toward reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people of Canada (1)(3). |

| 2 Joseph & Joseph. 2019. Indigenous Relations | Insights, tips and suggestions to make reconciliation a reality. Indigenous Relations Press. |

References

- Greenwood M dLS, Stout R, Larstone R), Sutherland J. Introduction to Determinants of First Nation, Inuit and Metis Peoples’ Health in Canada., 2022.

- Joseph, B. Indigenous Relations: Insights, tips and suggestions to make reconciliation a reality: Indigenous Relations Press, 2019.

- https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1450124405592/1529106060525. In.

- https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/subjects-start/indigenous_peoples. In.

- https://countryeconomy.com/countries/canada. In.

- https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/author/takwa-souissi#:~:text=Takwa%20Souissi%20is%20a%20lawyer,actualit%C3%A9%20and%20Premi%C3%A8res%20en%20Affaires. In.

- https://www.canlii.org/en/ca/scc/doc/2016/2016scc12/2016scc12.html. In.

- https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/2698184/Jugement.pdf. In.

- https://decisions.chrt-tcdp.gc.ca/chrt-tcdp/decisions/en/item/232587/index.do?r=AAAAAQAOY2FyaW5nIHNvY2lldHkB. In.

- https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-services-canada/news/2021/09/government-of-canada-honours-joyce-echaquans-spirit-and-legacy.html. In.

- https://rapportspvm2019.ca/en/grands_dossiers/. In.

- https://oci-bec.gc.ca/sites/default/files/2023-10/Annual%20Report%20EN%20%C3%94%C3%87%C3%B4%20Web.pdf. In.

- Kovach, M. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/235413280_Indigenous_methodologies_Characteristics_conversations_and_contexts, 2009.

- k, M. https://afnigc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Data_Resources_Report.pdf. In.

- https://publications.gc.ca/Collection-R/LoPBdP/EB/prb9924-e.htm. In.

- https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.801236/publication.html. In.

- https://indigenousdatatoolkit.ca/project/the-fnigcs-a-first-nations-data-governance-strategy/. In.

- https://publications.gc.ca/site/archivee-archived.html?url=https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2015/trc/IR4-8-2015-eng.pdf. In.

- Quon, A. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/sask-drug-policy-1.7087683. In; 2024.

- https://www.health.gov.au/. In: Australian Government Department of Health & Ageing.

- Shoukry NH, Feld JJ, Grebely J. Hepatitis C: A Canadian perspective. Can Liver J 2018;1:1-3. [CrossRef]

- Popovic N, Williams A, Perinet S, Campeau L, Yang Q, Zhang F, Yan P, et al. National Hepatitis C estimates: Incidence, prevalence, undiagnosed proportion and treatment, Canada, 2019. Can Commun Dis Rep 2022;48:540-549.

- Sadler MD, Lee SS. Hepatitis C virus infection in Canada’s First Nations people: a growing problem. Can J Gastroenterol 2013;27:335. [CrossRef]

- Uhanova J, Tate RB, Tataryn DJ, Minuk GY. The epidemiology of hepatitis C in a Canadian Indigenous population. Can J Gastroenterol 2013;27:336-340. [CrossRef]

- Trubnikov M, Yan P, Archibald C. Estimated prevalence of Hepatitis C Virus infection in Canada, 2011. Can Commun Dis Rep 2014;40:429-436.

- Rotermann M, Langlois K, Andonov A, Trubnikov M. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infections: Results from the 2007 to 2009 and 2009 to 2011 Canadian Health Measures Survey. Health Rep 2013;24:3-13.

- https://diseases.canada.ca/notifiable/. In.

- https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-services-canada.html. In.

- El-Bassel N, Shaw SA, Dasgupta A, Strathdee SA. People who inject drugs in intimate relationships: it takes two to combat HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2014;11:45-51. [CrossRef]

- Stoicescu C, Cluver LD, Spreckelsen TF, Mahanani MM, Ameilia R. Intimate partner violence and receptive syringe sharing among women who inject drugs in Indonesia: A respondent-driven sampling study. Int J Drug Policy 2019;63:1-11. [CrossRef]

- https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health.html. In.

- Singh D, Prowse S, Anderson M. Overincarceration of Indigenous people: a health crisis. CMAJ 2019;191:E487-E488.

- Owusu-Bempah A, Kanters S, Druyts E, Toor K, Muldoon KA, Farquhar JW, Mills EJ. Years of life lost to incarceration: inequities between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Canadians. BMC Public Health 2014;14:585. [CrossRef]

- Muir NM, Rotondi M, Brar R, Rotondi NK, Bourgeois C, Dokis B, Hardy M, et al. Our Health Counts: Examining associations between colonialism and ever being incarcerated among First Nations, Inuit, and Metis people in London, Thunder Bay, and Toronto, Canada. Can J Public Health 2023. [CrossRef]

- Nitulescu R, Young J, Saeed S, Cooper C, Cox J, Martel-Laferriere V, Hull M, et al. Variation in hepatitis C virus treatment uptake between Canadian centres in the era of direct-acting antivirals. Int J Drug Policy 2019;65:41-49.

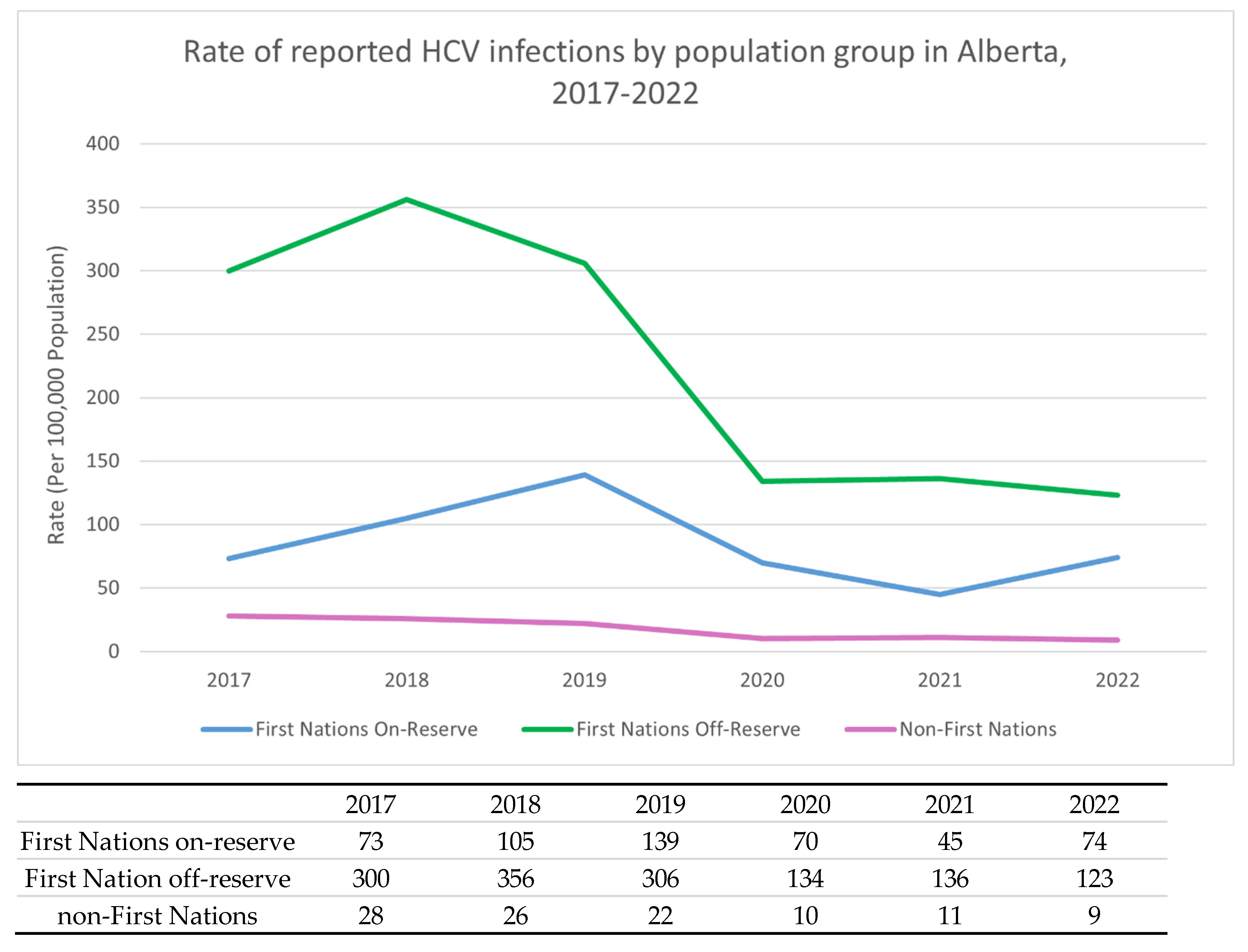

- O’Neil CR, Buss E, Plitt S, Osman M, Coffin CS, Charlton CL, Shafran S. Achievement of hepatitis C cascade of care milestones: a population-level analysis in Alberta, Canada. Can J Public Health 2019;110:714-721.

- Ortiz-Paredes D, Amoako A, Ekmekjian T, Engler K, Lebouche B, Klein MB. Interventions to Improve Uptake of Direct-Acting Antivirals for Hepatitis C Virus in Priority Populations: A Systematic Review. Front Public Health 2022;10:877585.

- Parmar P, Corsi DJ, Cooper C. Distribution of Hepatitis C Risk Factors and HCV Treatment Outcomes among Central Canadian Aboriginal. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;2016:8987976.

- Saeed S, Thomas T, Dinh DA, Moodie E, Cox J, Cooper C, Gill J, et al. Frequent Disengagement and Subsequent Mortality Among People With HIV and Hepatitis C in Canada: A Prospective Cohort Study. Open Forum Infect Dis 2024;11:ofae239.

- Mendlowitz AB, Bremner KE, Krahn M, Walker JD, Wong WWL, Sander B, Jones L, et al. Characterizing the cascade of care for hepatitis C virus infection among Status First Nations peoples in Ontario: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ 2023;195:E499-E512.

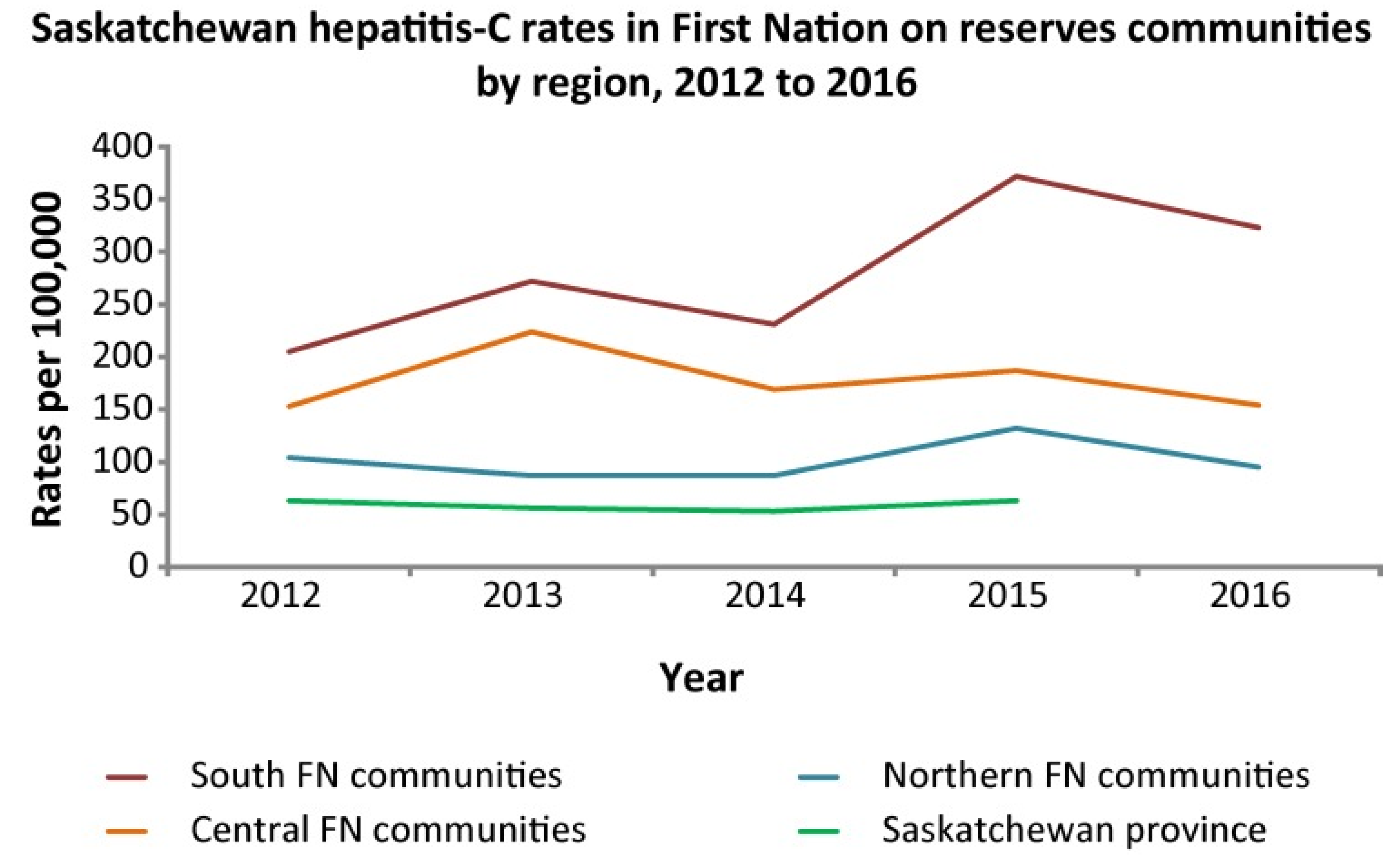

- Skinner S, Cote G, Khan I. Hepatitis C virus infection in Saskatchewan First Nations communities: Challenges and innovations. Can Commun Dis Rep 2018;44:173-178.

- Fayed ST, King A, King M, Macklin C, Demeria J, Rabbitskin N, Healy B, et al. In the eyes of Indigenous people in Canada: exposing the underlying colonial etiology of hepatitis C and the imperative for trauma-informed care. Can Liver J 2018;1:115-129.

- O’Keefe-Markman C, Lea KD, McCabe C, Hyshka E, Bubela T. Social values for health technology assessment in Canada: a scoping review of hepatitis C screening, diagnosis and treatment. BMC Public Health 2020;20:89.

- Gordon J, Bocking N, Pouteau K, Farrell T, Ryan G, Kelly L. First Nations hepatitis C virus infections: Six-year retrospective study of on-reserve rates of newly reported infections in northwestern Ontario. Can Fam Physician 2017;63:e488-e494.

- Pearce ME, Jongbloed K, Demerais L, MacDonald H, Christian WM, Sharma R, Pick N, et al. "Another thing to live for": Supporting HCV treatment and cure among Indigenous people impacted by substance use in Canadian cities. Int J Drug Policy 2019;74:52-61.

- Pearce ME, Jongbloed K, Pooyak S, Christian WM, Teegee M, Caron NR, Thomas V, et al. The Cedar Project: exploring the role of colonial harms and childhood maltreatment on HIV and hepatitis C infection in a cohort study involving young Indigenous people who use drugs in two Canadian cities. BMJ Open 2021;11:e042545.

- https://www.canhepc.ca/sites/default/files/media/documents/blueprint_hcv_2019_05.pdf. In.

- Krajden M, Cook D, Janjua NZ. Contextualizing Canada’s hepatitis C virus epidemic. Can Liver J 2018;1:218-230.

- Zietara F, Crotty P, Houghton M, Tyrrell L, Coffin CS, Macphail G. Sociodemographic risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection in a prospective cohort study of 257 persons in Canada who inject drugs. Can Liver J 2020;3:276-285.

- Amoako A, Ortiz-Paredes D, Engler K, Lebouche B, Klein MB. Patient and provider perceived barriers and facilitators to direct acting antiviral hepatitis C treatment among priority populations in high income countries: A knowledge synthesis. Int J Drug Policy 2021;96:103247.

- https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1690909773300/1690909797208. In.

- https://www.indigenousrelationsacademy.com/products/indigenous-relations. In.

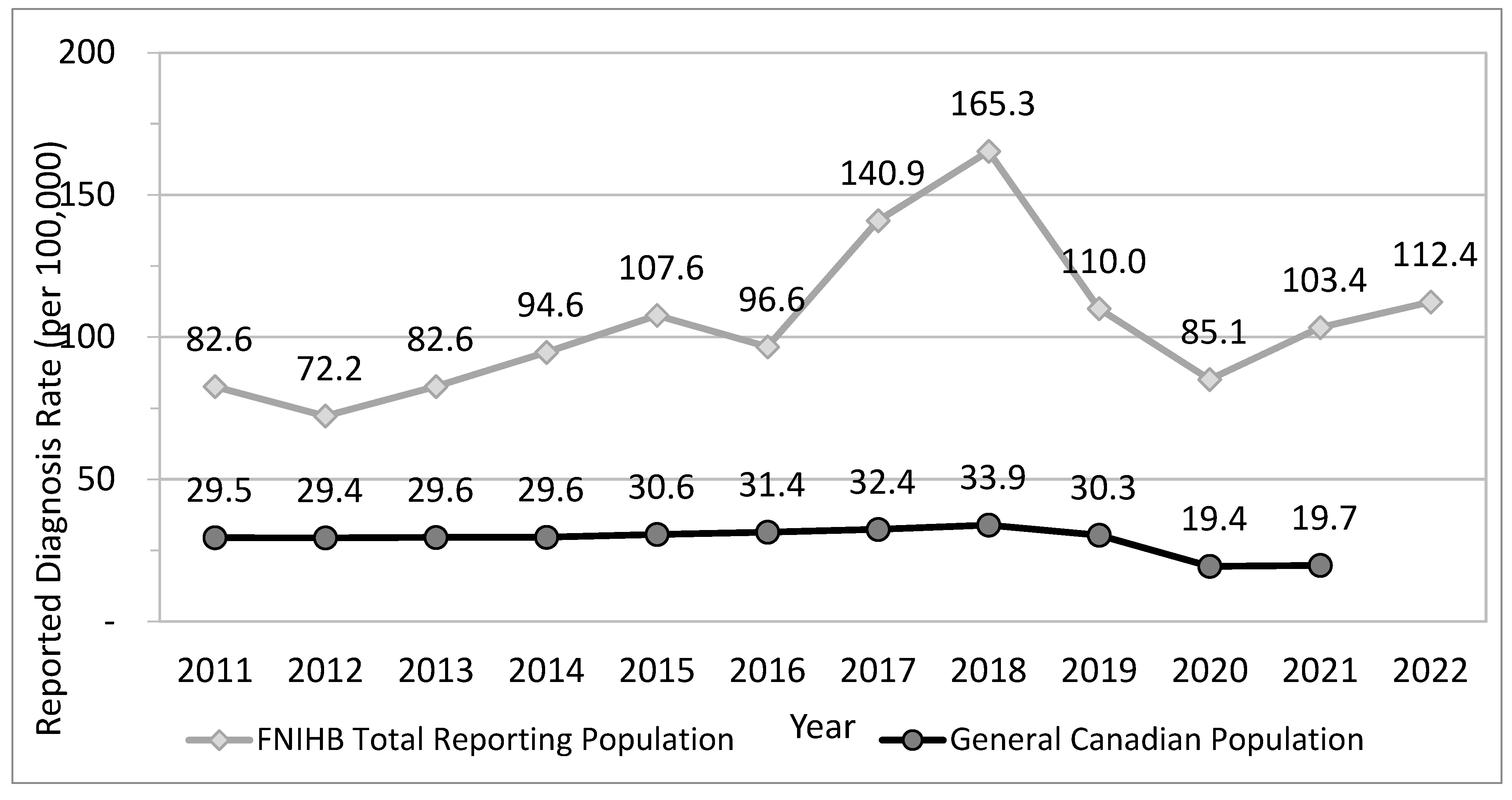

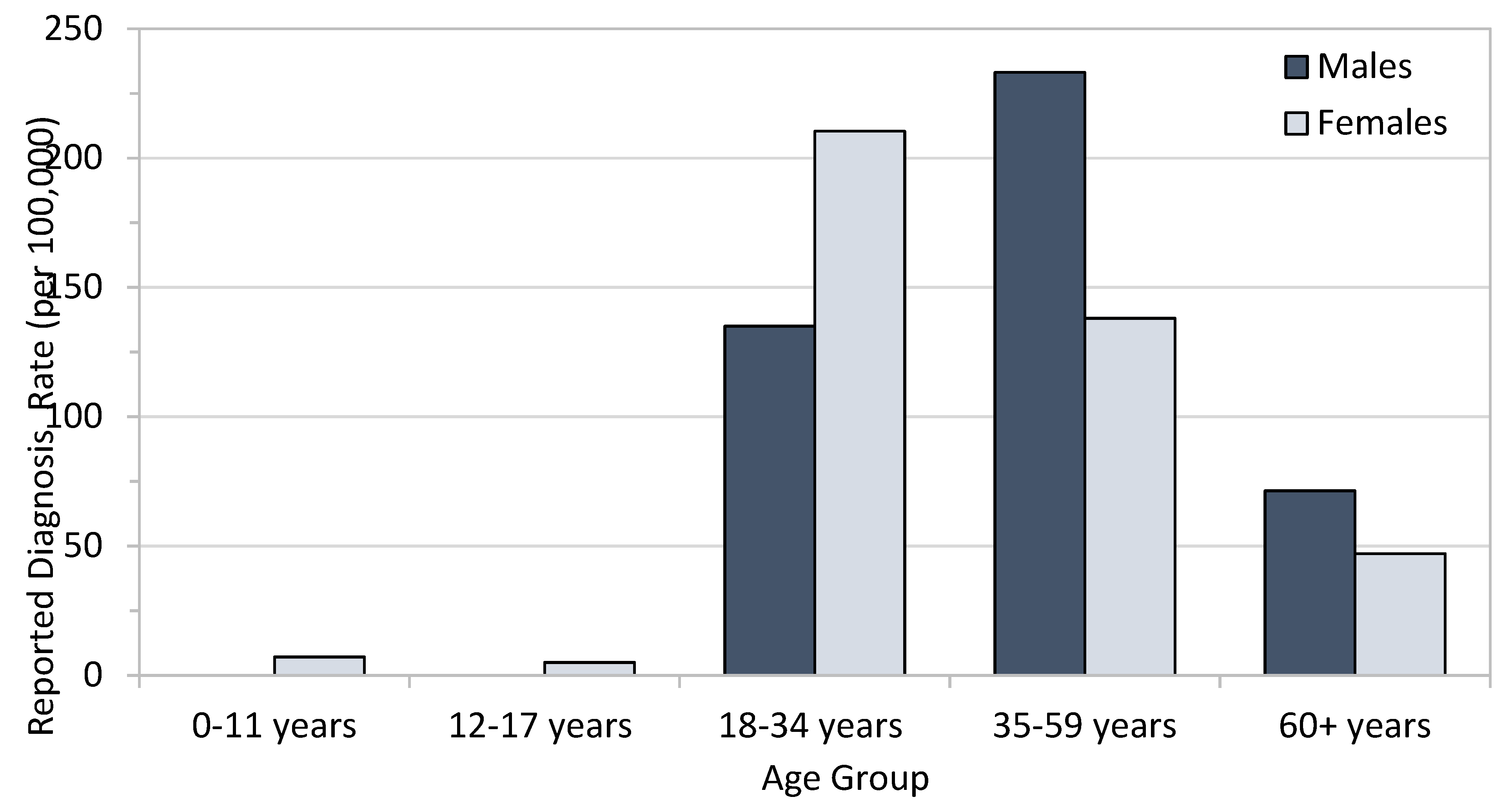

- Lourenco L, Kelly M, Tarasuk J, Stairs K, Bryson M, Popovic N, Aho J. The hepatitis C epidemic in Canada: An overview of recent trends in surveillance, injection drug use, harm reduction and treatment. Can Commun Dis Rep 2021;47:561-570.

- Dunn KP, Williams KP, Egan CE, Potestio ML, Lee SS. ECHO+: Improving access to hepatitis C care within Indigenous communities in Alberta, Canada. Can Liver J 2022;5:113-123.

- Granfield R, & Cloud, W.. Coming clean: Overcoming addiction without treatment. New York: New York University Press, 1999.

- Cloud W, & Granfield, R: A life course perspective on exiting addiction: The relevance of RC in treatment.. In: Nordic Council for Alcohol and Drug Research). Volume 44: NAD Publication, 2004; 185-202.

- Lettner B, Mason K, Greenwald ZR, Broad J, Mandel E, Feld JJ, Powis J. Rapid hepatitis C virus point-of-care RNA testing and treatment at an integrated supervised consumption service in Toronto, Canada: a prospective, observational cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Am 2023;22:100490.

- Dunn KPR, Oster RT, Williams KP, Egan CE, Letendre A, Crowshoe H, Potestio ML, et al. Addressing inequities in access to care among Indigenous peoples with chronic hepatitis C in Alberta, Canada. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;7:590-592.

- Dunn, KP. https://cumming.ucalgary.ca/resource/echo/home. In.

- Young J, Ablona A, Klassen BJ, Higgins R, Kim J, Lavoie S, Knight R, et al. Implementing community-based Dried Blood Spot (DBS) testing for HIV and hepatitis C: a qualitative analysis of key facilitators and ongoing challenges. BMC Public Health 2022;22:1085.

- Brown SJ, Cosgrove LT, Lee SS. Achieving HCV micro-elimination in rural communities. Can Liver J 2021;4:1-3.

- Pandey M, Konrad S, Reed N, Ahenakew V, Isbister P, Isbister T, Gallagher L, et al. Liver health events: an indigenous community-led model to enhance HCV screening and linkage to care. Health Promot Int 2022;37.

- Gale, N. https://www.catie.ca/programming-connection/shelter-based-hepatitis-c-treatment-at-the-calgary-drop-in-centre. In.

- Bartlett SR, Wong S, Yu A, Pearce M, MacIsaac J, Nouch S, Adu P, et al. The Impact of Current Opioid Agonist Therapy on Hepatitis C Virus Treatment Initiation Among People Who Use Drugs From the Direct-acting Antiviral (DAA) Era: A Population-Based Study. Clin Infect Dis 2022;74:575-583.

- Kronfli N, Dussault C, Bartlett S, Fuchs D, Kaita K, Harland K, Martin B, et al. Disparities in hepatitis C care across Canadian provincial prisons: Implications for hepatitis C micro-elimination. Can Liver J 2021;4:292-310.

- https://treeofcreation.ca/. In.

- https://www.oahas.org/. In.

- https://caan.ca/. In.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).