1. Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains a global, public health concern, with approximately 1.2 million new cases reported annually and an estimated 1.1 million deaths each year resulting from HBV related complications [

1,

2] despite of available stable and effective vaccine [

3]. The burden, and prevalence of HBV infection varies geographically, with countries in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa regions having the highest burden [

4]. Kenya relatively has lower national prevalence (3.5%)[

5] compared to neighboring countries[

6,

7], however this prevalence varies across population types and geographical regions[

5]. Higher rates are recorded among people with jaundice seeking healthcare services[

8] and those living in northern part of Kenya[

5]. The prevalence is lower among expectant mothers[

9] and those living in central and southern Kenya[

5]. Exposure to different predisposing factors accounts for these variations.

HBV infection is a silent epidemic that may remain quiescent for many years[

10,

11]. Most of those infected are asymptomatic and not aware till chronic stages of the infection, unknowingly transmitting the virus to unborn, spouses, partners and other people via body fluids(10-13). In Africa, most transmissions are believed to occur perinatally[

4,

14]. In the absence of intervention, 90% of perinatal infection develop into chronic HBV infection[

15]. Additionally, in highly endemic areas, HBV transmission often occurs horizontally within households and through close contact with infected individuals(4, 14, 16). These close contacts can be through sharing sharp items like razors, unsafe sex with infected partners, or skin puncture using contaminated sharp object and sharing unsafe injections[

11,

16]. These transmission modes are highly efficient, influenced by a combination of biological (viral load levels, age), behavioral (sexual practices, household exposures), health system (screening and diagnosis), and socio-economic factors(16-18). However, the interaction of these factors during transmission remains unclear.

In adults, HBV infection progresses to chronic infection in approximately 5–10% of cases, while the majority successfully clear the virus and develop long-lasting protective antibodies(1, 2, 19). The critical factors that predispose certain individuals to persistent infection, while others develop long-term immunity, remain unclear. This often yields conflicting results and appears to vary across populations and study settings [20, 21]. Understanding these factors is very useful in developing; structural countermeasures, tailored prevention strategies, long-term community engagement, and efficient programs that minimize resource wastage and sustained infection control. In 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) adopted a global hepatitis strategy that aims to eliminate viral hepatitis as a public health threat by the year 2030 urging for a 90% reduction in new infections and 65% decrease in deaths [1, 4, 22]. This initiative is yet to be realized in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC)[

23]. In line with this global strategy, we sought to establish the rate of hepatitis B infection in Baringo and Kisumu counties in Kenya and to establish the transmission predictors that can be used to develop sustainable prevention models and disease management strategies. In our results, we demonstrate different community HBV transmission patterns and trends that underscore the need for different prevention approaches and linkage to care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study sites

The study was conducted in Baringo and Kisumu Counties of Kenya. Baringo County is located in the central Rift Valley region with HIV prevalence range between 2.1%-4.9%, [

24] and Kisumu County that is located at the shores of Lake Victoria where there is a comprehensive HIV program based on an estimated prevalence of 11.7%[

24].

2.2. Study population and recruitment

Data from the community and selected health facility was collected for a period of one and a half years from September 2023 to February 2025. In the community, mass testing for HBV infection was done in the villages and local shopping centers by trained health care workers. The communities (villages) were sensitized and educated about free HBV testing by area public administration and health officers. During community testing, the health care workers team: nurses, laboratory technicians, medical officers and pharmacists visited the community to conduct mass testing.

All participants were aged 16 years and above and provided written informed consent or assent. For participants aged between 16 and 17 years, parental or guardian permission was obtained in addition to their written assent. A structured questionnaire was administered by trained study staff using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) (Version 13.8.1) hosted at KEMRI on a tablet (

https://projectredcap.org/software/). The questionnaire contained social demographic, behavioral, economic and cultural characteristics. Finger prick blood samples were collected from participants by trained laboratory officers and tested for the presence of HBsAg using KEMRI HEPCELL Rapid test (KEMRI Production Unit, Nairobi, Kenya), according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The test results were then recorded in the REDCap and electronically submitted to a central study database. All positive samples were confirmed using real-time PCR and all who tested positive for the virus were linked to care. A similar process was followed to recruit and test patients in the outpatient departments (OPD) of selected health facilities in the study counties. Anyone who tested HBsAg+ was linked to care.

2.3. Data management and analysis

Data from REDCap was downloaded from central database repository to STATA software Release 18 and coded. The estimated HBV prevalence in the population under study was calculated as a proportion of HBsAg+ participants and the total people tested in that region and stratified by gender and age group. The age specific trends were calculated as age groups differences stratified by gender and location, while sex-specific trend was the difference in HBV prevalence between males and females. Intrafamilial cluster were members living in the same household or have common biological parents. Descriptive and inferential analysis was computed using STATA software. Multiple logistic regression modeling was performed to identify factors associated with HBV infection and presented as adjusted prevalence ratios (aPR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI). The variables were stratified by social demographic, behavioral, financial and cultural characteristics. The significance level was set at a P-value of less than 0.05 and a 95% confidence interval for all statistical analyses.

2.4. Ethical consideration

This study was approved by Kenya Medical Research Institute’s (KEMRI’s) Scientific and Ethics Review Unit (SERU) Protocol No. SERU4680 and NACOSTI License No. NACOSTI/P/23/27902. In addition, informed written consent was sought from participants aged above 18 years old and assent for 17 years and below. Consenting was done by trained personnel. All methods were performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

3. Results

A total of 3,034 study participants were interviewed, of which 65.4% were female and 34.6% male. Participant turnout was lower in Kisumu County (8.1%) compared to Baringo County (91.9%). Most of the participants had the highest education level as either primary, 1179 (46.1%) or secondary 1031 (40.3%) with a small proportion having college 334 (13.1%) and the rest had none (

Table 1). More than 80% of the participants were married (n=2431) of which monogamous (63.7%) were more than polygamous marriages (17.3%). Those who were single and never married were 425 (14.2%) and the rest were once married but widowed(er) (

Table 1). Of those who reported having children 63.9% had children aged 5 years and below. When the participants were asked the number of siblings in their family, 1597 (55.6%) reported to be less than five, 1153 (40.2%) had between 5 and 10 and the rest had more than 10 siblings (

Table 1). The study was carried in rural communities where majority 1838 (61.9%) were unemployed of which only 383 (34.2%) had a net monthly income of more than US

$100 (

Table 1). The mean age was 37 ± 5.93 years, ranging from 17 to 94 years. The proportion of participants within each age group is shown in

Table 1.

Prevalence and sociodemographic factors associated with Hepatitis B infection

Out of the 3034 participants, 191 tested positives for HBsAg resulting in 6.3% (95% CI=0.055-0.072) the prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in the study regions. We assessed the association between demographic characteristics and HBV infection using a logistic regression model (

Table 1). In the bivariable analysis demographic factors that were associated with Hepatitis B infection (

p-value ≤0.1) included; respondents who were married (cPR=2.18;95%CI=1.31,3.60) in marital status category, those whose education level was secondary (cPR=0.70; 95%CI=0.50,0.98), respondents with 5 to 10 children (cPR=1.90; 95%CI=1.41,2.55), respondents with children more than 10 (cPR=2.07; 95%CI=1.33,3.22), respondents who live more than 5 km to a health facility (cOR = 7.3; 95%CI = 1.68 - 31.70), net monthly income of the unemployed between 51 to 100 USD (cPR=1.81; 95%CI=0.97,3.39), and respondents who live in Baringo (cPR=0.18; 95%CI=0.06,0.56), with Baringo having a higher prevalence (6.8% (95%CI=0.058-0.077)) as compared to 1.2% (95%CI=-0.002-0.026) for Kisumu County. These factors were later subjected to a multivariable analysis.

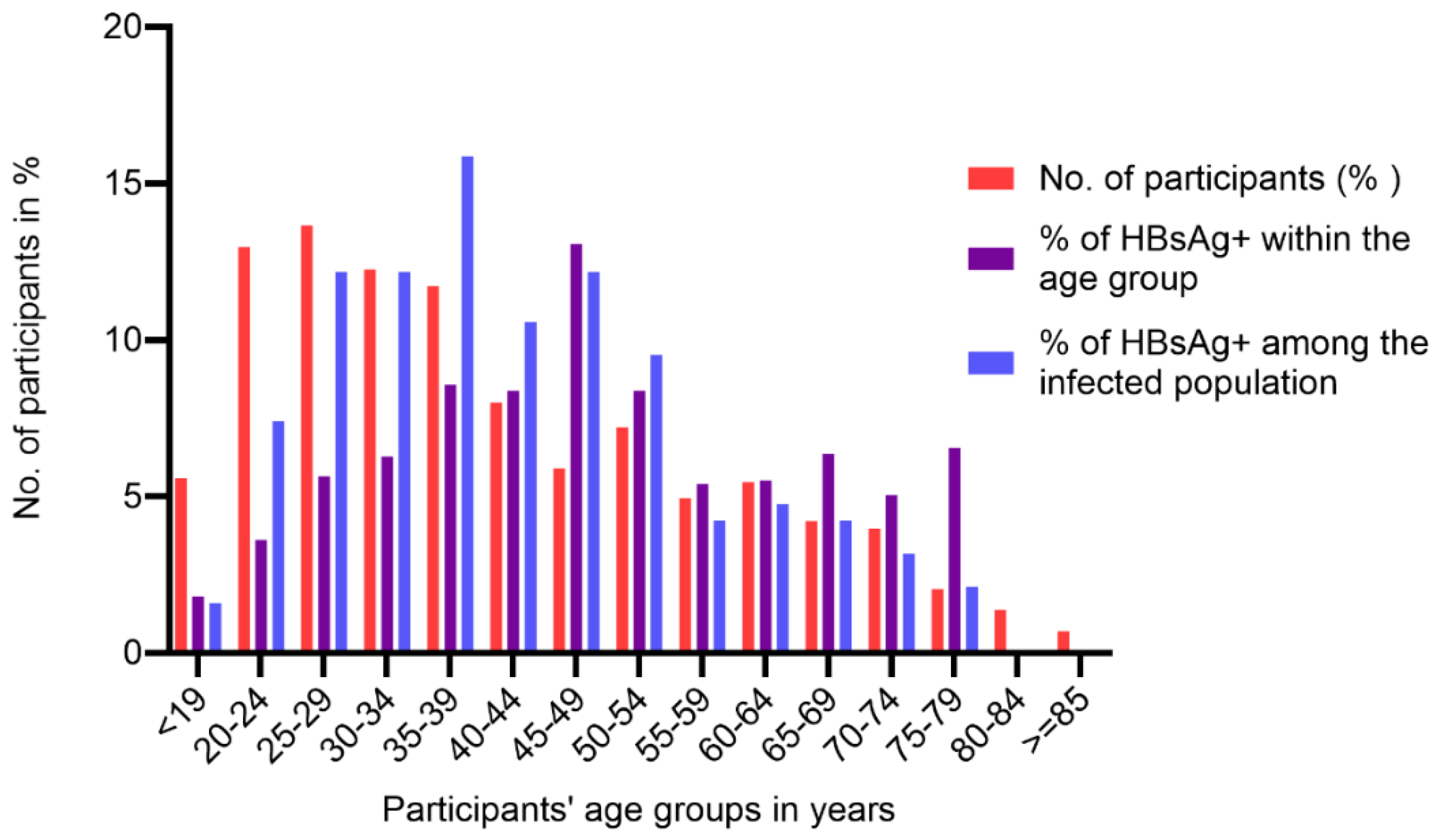

Trends of Hepatitis B Infection by Age Group

On stratifications of participants by age, highest HBV prevalence of 13.1% was observed in individuals aged 45 to 49 years and lowest of 1.8% in ≤19 years old (

Figure 1). Among the infected (HBsAg+) group, participants aged between 25-49 years had a prevalence of more than 10%, with a gradual decrease to no infection in participants of ≥80 years old (

Figure 1). Additionally, among HBsAg+, age groups 35-39 years had the highest prevalence (15.9%) while and ≤19 years had the lowest (

Figure 1).

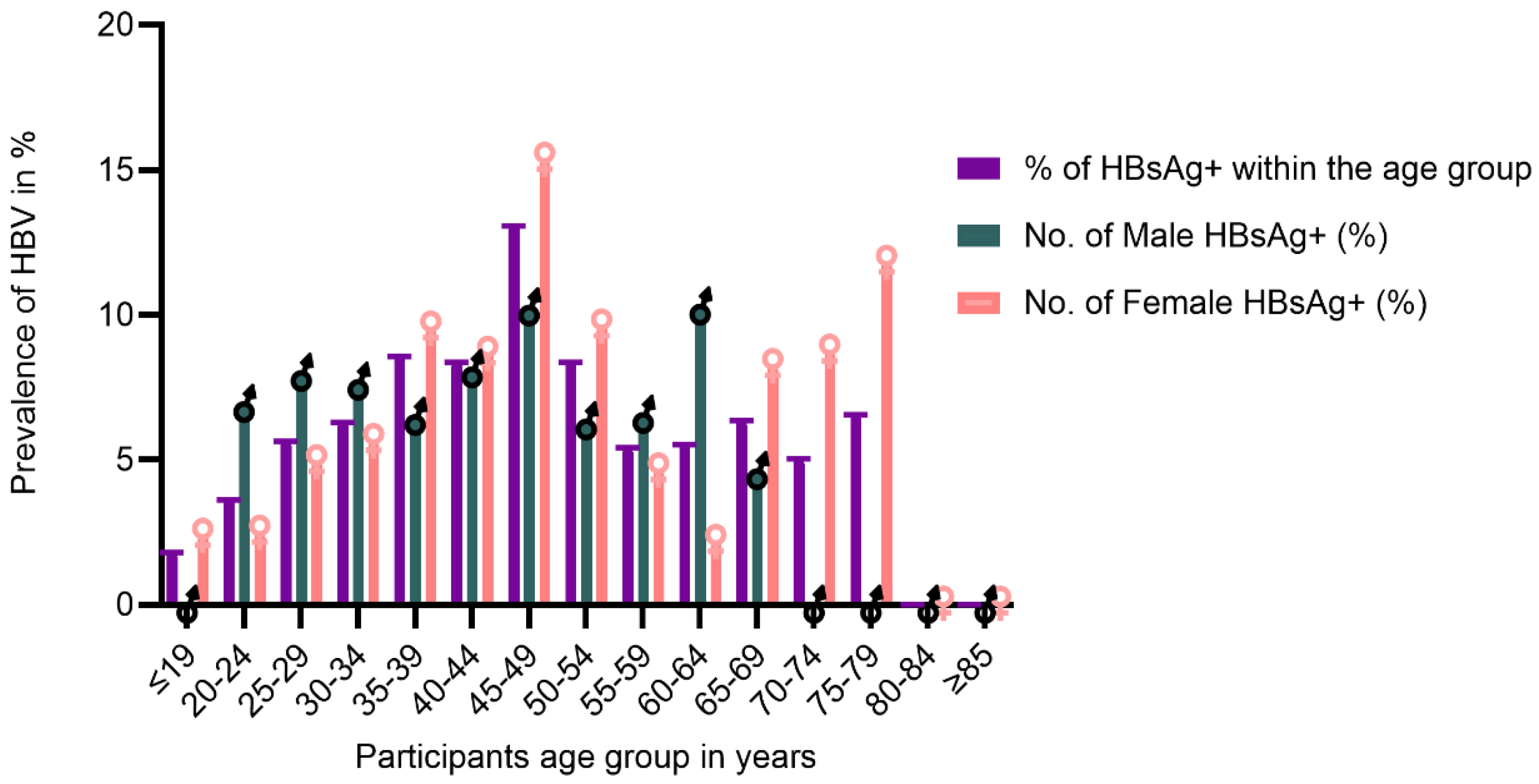

Distribution of Hepatitis B Infection by Age Group and Gender

In the younger age groups males had a higher prevalence up to 34 years and female of older ages demonstrated a higher prevalence than male (

Figure 2 and

appendix 1). The highest infected age group was 45-49 years for both male and female. We observed that infected males were <70 years, compared to female who were infected up 79 years (

Figure 2 and

Appendix 1). In bivariable analysis, being 30 years and above was associated with hepatitis B infection with respondents between 40 to 49 (cPR = 6.32; 95%CI = 1.93 - 20.66) being significantly affected with HBV infection (

table 1).

Trends of HBV infection among related families

Among the families that participated in the study, 40 families were from the community mass testing of which 6 families (15.0%) had two or more members infected. Almost half (48.6%) of the families had members were infected and among the siblings (56.7%) had the infection. For parents, only half had at least one parent infected (

Table 2). In one of the families where the mother had died of hepatocellular carcinoma, all the children were HBV positive. Current infections among siblings were proportionately higher compared to the total family infections.

Behavioral, traditional and cultural practices and Hepatitis B infection

We assessed behavioral, traditional and cultural practices that predispose participants to hepatitis B virus. Majority (84.4%) of the participants shared items and sharps in the household, majority (87.9%) used public saloon or barber shops in hair dressing and shaving. More than half (65.2%) the participants reported traditional circumcision; male circumcision or female genital mutilation (FGM) that was culturally done at home (98.1%) and of which more than half (62.8%) reported sharing circumcision/FGM sharps. All participants reported on a heterosexual relationship, however, (85.0%) did not respond to the question on the number of sexual partners. Among those who reported history of alcohol consumption (23.3%) most of them (78.7%) occasionally consume alcohol. A very small proportion (3.8%) reported smoking or using tobacco.

Overall, we observed that the number of health care workers to be low; (0.9%). On occupational exposure to blood, especially in healthcare settings, only 4.4% had a history of blood transfusion, 0.4% reported having diabetes but none of them shared the diabetic sharps and only 0.9% reported tattoos or scarification. When the participants we asked if they have tested for HIV, more than half (55.8%) knew their HIV status of whom 3.6% were HIV positive

Table 3.

Bivariable analysis of behavioral, traditional and cultural practices

Bivariable analysis using logistic regression model revealed that respondents who shared items (cPR=1.76; 95%CI= 1.28,2.40) those who reported using other injectable drugs ( cPR=4.02; 95%CI=1.20,13.47) those who were circumcised) (cPR=155; 95%CI =1.13,2.13), those who take alcohol (cOR = 1.42; 95%CI = 1.03 - 1.97) (cPR=1.38; 95CI=1.03,1.88) were associated with Hepatitis B at

P value < 0.1. These factors were later subjected to a multivariable analysis (

table 3). Receiving transfused blood, being diabetic or being HIV positive, hair dressing and shaving hair, being a health care worker, smoking or use of tobacco, and having tattoos or scarification were not associated with Hepatitis B in the study population (

Table 3).

The results of the multivariable logistic regression suggest that respondents who live more than 5 km away from a health facility (aPR = 10.44; 95%CI = 2.21 - 49.37; p = 0.003), those who use other injectable drugs (aPR=6.71 95%CI = 1.34,33.67; p=0.021), those who shared items (aPR=2.60; 95%CI= 1.54,4.39; p=<0.001), and those who underwent traditional circumcision (aPR 1.02; 95%CI=0.56,1.88; p=0.040) were significantly associated with higher prevalence rates of Hepatitis B virus. (

table 1 and

table 3). On the other hand, education level, being imprisoned or jailed, age category, marital status, number of children, being circumcised, and taking alcohol sharing hygiene items were not associated with Hepatitis B infection.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first sero-epidemiological study of Hepatitis B infection in the rural communities of Kenya. The observed prevalence of 6.33% places the study communities in Kisumu and Baringo, within the WHO-defined intermediate endemicity range (2–7%)[

25]. The findings affirm other studies reporting intermediate endemicity [

5,

9] with variations largely attributed to geographical differences among study populations. Baringo County that reported a prevalence of >6% is among other counties in Rift valley and Northern Kenya that have high endemicity. Kisumu County, has a high prevalence for HIV compared to Baringo county, despite the lower participant turnout observed in Kisumu County compared to Baringo, the prevalence rate was notably lower[

5]. HIV and hepatitis share transmission routes, and these two counties exemplify regions where one infection predominates. Integrating HBV into existing HIV services offers a promising approach to strengthening community-based services, however, the uneven distribution of HIV services across regions may limit its implementation and scale-up. These findings highlight the need to strengthen community-based HBV screening and early diagnosis strategies to ensure timely linkage to care and to reduce community-based transmission

HBV prevalence by gender distribution showed that the males had a slightly higher prevalence as compared to the female, 6.6% and 6.2% respectively. This is similar with findings from other studies[

26]. Although more males are infected than females, the study also showed that there was a higher proportion of HBsAg+ women at old age compared to men, suggesting that female live with the virus longer compared to male. This observation may be attributed to sexual dimorphism of the liver, and androgen response elements which has a strong influence in HBV infection outcome with males more likely to suffer from HBV complication compared to female(27-29). Similarly, females tend to mount stronger immune responses and likely to develop protective antibodies compare to male(27, 30-32). This could explain why no cases of infection were observed among males over 70 years.

Hepatitis B virus progresses to HCC after three to four decades of infection, if there is no intervention[

33,

34]. The mean age of our study population was 37 ± 5.93 years. We observed a steady increase in infection, with the highest prevalence observed among individuals aged 40-49 years, several studies have recorded similar observations[

26,

35]. In our study, age was significantly associated with HBV positivity at bivariant analysis, individuals aged 30 years and above were more likely to be infected. In various occasions the high HBV burden among the elderly largely result from infections acquired perinatally or during early childhood exposure(4, 14, 36, 37), such transmissions were due to lack of immunization, close contact and sexual activities during adolescence or early adulthood[

14]. This study showed that the proportion of infection among young age was low compared to older participants, most likely due to access to immunization, improved health care and standards of living that could reduce close contacts.

Our finding from community mass testing highlighted that HBV infections were not randomly distributed but tend to cluster within household. There was clear evidence of household clustering with 15.0% of families reporting two or more infected members and nearly half of the members (48.6%) within the family affected. While transmission appeared particularly pronounced among siblings (56.7%), children and young family members are at risk of transmitting HBV infection to each other, probably through close contact. Other studies have reported similar household transmissions, in India and Tanzania they reported a household prevalence of 9.2% and 5.4% respectively[

38,

39], in Arak Iran, they reported a prevalence of 23.3% among HBsAg+ family members with mothers of index cases having the highest infection rates (46.6%)[

40]. A study in in Kinshasa had a HBsAg intrafamilial prevalence of 5.0% and revealed that exposed offspring had 3.3 times the prevalence of HBV compared to unexposed offspring[

41]. Although the number of children and sharing household sharp items were not significantly associated with HBV transmission at multivariable logistic regression, studies involving different regions and large samples have yielded contrary findings[

39]. Identifying the key predictors for interfamilial transmission remains crucial for developing effective prevention strategies.

Married individuals had the highest prevalence (6.95%), but the once married had the highest prevalence ratio suggesting they were the most affected group. Participants with education level above primary had a lower prevalence (5.57%) as compared to those with primary education or below (7.2%). This may impact the knowledge and awareness of transmission or inadequate healthcare access that is associated with limited health literacy and access to prevention strategies.

Factors independently associated with HBV infection in this study residing in Baringo, users of other injectable drugs, those circumcised and staying >5 kilometers from a healthcare facility, exhibited significantly higher ratios of being infected with the Hepatitis B virus. HIV positivity, being a health care worker, smoking or use of tobacco, and having tattoos or scarification were not associated with HBV infection, other studies have yielded contrary findings(42-44).

5. Conclusions

We identified key transmission predictors of HBV transmission as; household exposure to infected individuals, traditional and cultural practices like circumcision, unsafe drug injectables and living in areas that have high HBV burden. Identifying these exact predisposing factors is a milestone towards transforming public health efforts from broad and reactive to sustainable precise preventive measures. To reduce the family close contact transmission, increasing awareness about Hepatitis B and vaccination of uninfected family members is essential. These findings highlight the need for timely infant immunization and catch-up vaccine doses to adolescents and adults at increased risk of infection. Administering birth-dose HBV vaccination would provide the much needed early protection against HBV infection especially for infants born to households inhabited by infected members.

Recommendations

There is need to scale up HBV community services to other regions. This can be achieved through integrating HBV services to the existing interventions. We identified key predictors of HBV transmission in endemic regions and recommend their integration into national HBV awareness and prevention campaigns to enhance control efforts.

This study focused on current HBV transmission and did not explore historic exposure to HBV; thus, hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb) was not tested. We recommend future results to consider HBcAb especially in intra-familial clusters and inclusion of different regions in the country.

Author Contributions

For Conceptualization: MO. Methodology, MO, DM-M, JHK, SWO, LMM, EO, HM, GT, RK, ES, AO, RO. Writing – original draft MO, DM-M, RO. Software: MO, HM, EO, SWO, LMM. Validation, MO, AO, ES, GT, RK. Formal Analysis, MO, VW. Investigation, MO, DM-M, JHK, SWO, LMM, EO, HM, GT, RK, ES, AO, RO. Resources; MO. Data Curation: MO, DKO, EOO, BCW. Writing – Original draft preparation: MO, DM-M. Writing – Review & editing, MO, DM-M, JHK, SWO, LMM, EO, HM, GT, RK, ES, AO, RA, VW. Visualization: EO, JHK, RO. Supervision, AO, DM-M, JHK. Project Administration: MO, GT, HM, SWO, LMM, EO. Funding Acquisition: MO, AE. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by The Gilead Sciences, Inc. The grant was awarded to Missiani Ochwoto in 2022 under Research Scholar Program (RSP) Award.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Kenya Medical Research Institute’s (KEMRI’s) Scientific and Ethics Review Unit (SERU) Protocol No. SERU4680.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. In addition, informed written consent was sought from all participants by trained personnel collecting the data for storage and publication of their data

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are confidential and are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the county research departments of Kisumu and Baringo for allowing us to conduct this research in their counties. We are grateful to the personnel involved in hepatitis B screening and data collection in Kisumu County and Marigat subcounty Hospital. We acknowledge KEMRI management for the support and the ICT department for support in developing data tools used in data collection and training of health workers. We acknowledge The Ministry of Health at Division of National AIDS and STI Control Program (NASCOP) for their support and Dr. Mercy Karoney, of Moi University, School of Medicine for her clinical support. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HBsAg |

hepatitis B surface antigen |

| HBV |

Hepatitis B virus |

| aPR |

prevalence ratios |

| NASCOP |

National AIDS and STI Control Program |

| KEMRI |

Kenya Medical Research Institute’s |

| LMIC |

low- and middle-income countries |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| HCC |

Hepatocellular carcinoma |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix Table1.

Distribution of Hepatitis B Infection by Age.

Appendix Table1.

Distribution of Hepatitis B Infection by Age.

| Age group |

No. of participants

n (%) |

No. of HBV Infected

n |

Proportion (%) of HBV infected within: |

| Age group |

The total population |

The infected population |

| ≤19 |

167 |

(5.6) |

3 |

(1.8) |

(0.1) |

(1.6) |

| 20-24 |

387 |

(13.0) |

14 |

(3.6) |

(0.5) |

(7.4) |

| 25-29 |

408 |

(13.7) |

23 |

(5.6) |

(0.8) |

(12.2) |

| 30-34 |

366 |

(12.3) |

23 |

(6.3) |

(0.8) |

(12.2) |

| 35-39 |

350 |

(11.7) |

30 |

(8.6) |

(1.0) |

(15.9) |

| 40-44 |

239 |

(8.0) |

20 |

(8.4) |

(0.7) |

(10.6) |

| 45-49 |

176 |

(5.9) |

23 |

(13.1) |

(0.8) |

(12.2) |

| 50-54 |

215 |

(7.2) |

18 |

(8.4) |

(0.6) |

(9.5) |

| 55-59 |

148 |

(5.0) |

8 |

(5.4) |

(0.3) |

(4.2 |

| 60-64 |

163 |

(5.5) |

9 |

(5.5) |

(0.3) |

(4.8) |

| 65-69 |

126 |

(4.2) |

8 |

(6.4) |

(0.3) |

(4.2) |

| 70-74 |

119 |

(4.0) |

6 |

(5.0) |

(0.2) |

(3.2) |

| 75-79 |

61 |

(2.0) |

4 |

(6.6) |

(0.1) |

(2.1) |

| 80-84 |

41 |

(1.4) |

0 |

(0.0) |

(0.0) |

(0.0) |

| ≥85 |

21 |

(0.7) |

0 |

(0.0) |

(0.0) |

(0.0) |

| Total |

2987 |

100.0 |

189 |

6.3 |

6.3 |

100 |

References

- World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report 2024: action for access in low-and middle-income countries; World Health Organization, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bigna, J.J.; Kenne, A.M.; Hamroun, A.; Ndangang, M.S.; Foka, A.J.; Tounouga, D.N.; et al. Gender development and hepatitis B and C infections among pregnant women in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infectious diseases of poverty. 2019, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Busafi, S.A.; Al-Harthi, R.; Al-Naamani, K.; Al-Zuhaibi, H.; Priest, P. Risk Factors for Hepatitis B Virus Transmission

in Oman. Oman Med J. 2021, 36, e287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearman, C.W.; Afihene, M.; Ally, R.; Apica, B.; Awuku, Y.; Cunha, L.; et al. Hepatitis B in sub-Saharan Africa: strategies to achieve the 2030 elimination targets. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2017, 2, 900–909. [Google Scholar]

- Ondondo, R.O.; Muthusi, J.; Oramisi, V.; Kimani, D.; Ochwoto, M.; Young, P.; et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in Kenya: A study nested in the Kenya Population-based HIV Impact Assessment 2018. PLOS ONE. 2024, 19, e0310923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilonzo, S.B.; Gunda, D.W.; Mpondo, B.C.T.; Bakshi, F.A.; Jaka, H. Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Tanzania: Current Status and Challenges. J Trop Med. 2018, 2018, 4239646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafeero, H.M.; Ndagire, D.; Ocama, P.; Kudamba, A.; Walusansa, A.; Sendagire, H. Prevalence and predictors of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in east Africa: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies published from 2005 to 2020. Archives of Public Health. 2021, 79, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochwoto, M.; Kimotho, J.H.; Oyugi, J.; Okoth, F.; Kioko, H.; Mining, S.; et al. Hepatitis B infection is highly prevalent among patients presenting with jaundice in Kenya. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2016, 16, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngaira, J.A.; Kimotho, J.; Mirigi, I.; Osman, S.; Ng'ang'a, Z.; Lwembe, R.; et al. Prevalence, awareness and risk factors associated with Hepatitis B infection among pregnant women attending the antenatal clinic at Mbagathi District Hospital in Nairobi, Kenya. Pan Afr Med J. 2016, 24, 315. [Google Scholar]

- Songtanin, B.; Chaisrimaneepan, N.; Mendóza, R.; Nugent, K. Burden, Outcome, and Comorbidities of Extrahepatic Manifestations in Hepatitis B Virus Infections. Viruses. 2024, 16, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook, G.; Chawla, Y. Hepatitis viruses. Sexually Transmitted Infections-E-book. 2013, 380.

- Zoulim, F.; Mason, W.S. Reasons to consider earlier treatment of chronic HBV infections. Gut. 2012, 61, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishizaki, A.; Bouscaillou, J.; Luhmann, N.; Liu, S.; Chua, R.; Walsh, N.; et al. Survey of programmatic experiences and challenges in delivery of hepatitis B and C testing in low-and middle-income countries. BMC infectious diseases. 2017, 17, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari, A.; Vincent, J.P.; Moorhouse, L.; Shimakawa, Y.; Nayagam, S. Risk of early horizontal transmission of hepatitis B virus in children of uninfected mothers in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health. 2023, 11, e715–e728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indolfi, G.; Easterbrook, P.; Dusheiko, G.; Siberry, G.; Chang, M.-H.; Thorne, C.; et al. Hepatitis B virus infection in children and adolescents. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2019, 4, 466–476. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, J.; Liu, Z.; Gu, F. Epidemiology and Prevention of Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Int J Med Sci. 2005, 2, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepard, C.W.; Finelli, L.; Fiore, A.E.; Bell, B.P. Epidemiology of Hepatitis B and Hepatitis B Virus Infection in United States Children. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2005, 24, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allain, J.-P.; Opare-Sem, O. Screening and diagnosis of HBV in low-income and middle-income countries. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2016, 13, 643–653. [Google Scholar]

- Terrault, N.A.; Lok, A.S.F.; McMahon, B.J.; Chang, K.M.; Hwang, J.P.; Jonas, M.M.; et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018, 67, 1560–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morikawa, K.; Shimazaki, T.; Takeda, R.; Izumi, T.; Umumura, M.; Sakamoto, N. Hepatitis B: progress in understanding chronicity, the innate immune response, and cccDNA protection. Ann Transl Med. 2016, 4, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, C.; Liu, Z.; Zou, G.; Li, J.; Lu, M. Host Genetic Determinants of Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Frontiers in Genetics. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global, W. Hepatitis Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jaquet, A.; Muula, G.; Ekouevi, D.K.; Wandeler, G. Elimination of viral hepatitis in low and middle-income countries: epidemiological research gaps. Current epidemiology reports. 2021, 8, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutisya, I.; Muthoni, E.; Ondondo, R.O.; Muthusi, J.; Omoto, L.; Pahe, C.; et al. A national household survey on HIV prevalence and clinical cascade among children aged≤ 15 years in Kenya (2018). Plos one. 2022, 17, e0277613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, A.; Horn, J.; Mikolajczyk, R.T.; Krause, G.; Ott, J.J. Estimations of worldwide prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systematic review of data published between 1965 and 2013. The Lancet. 2015, 386, 1546–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, S.A.; Rauf, A.; Alshahrani, M.M.; Awadh, A.A.A.; Iqbal, Z.; Soltane, R.; et al. Hepatitis B among University Population: Prevalence, Associated Risk Factors, Knowledge Assessment, and Treatment Management. Viruses. 2022, 14, 1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.; Goulder, P.; Matthews, P.C. Sexual Dimorphism in Chronic Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Infection: Evidence to Inform Elimination Efforts. Wellcome Open Res. 2022, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Li, L.; Zhao, J.; Ungvari, G.S.; Ng, C.H.; Duan, Z.; et al. Gender differences in demographic and clinical characteristics in patients with HBV-related liver diseases in China. PeerJ. 2022, 10, e13828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggieri, A.; Barbati, C.; Malorni, W. Cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in hepatocellular carcinoma gender disparity. International journal of cancer. 2010, 127, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, B.S. Sex differences in response to hepatitis b virus. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1979, 22, 1261–1266. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Wu, C.; Lou, Z.; Peng, C.; Jiang, L.; Wu, T.; et al. Changing incidence of hepatitis B and persistent infection risk in adults: a population-based follow-up study from 2011 in China. BMC Public Health. 2023, 23, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroffolini, T.; Esvan, R.; Biliotti, E.; Sagnelli, E.; Gaeta, G.B.; Almasio, P.L. Gender differences in chronic HBsAg carriers in Italy: Evidence for the independent role of male sex in severity of liver disease. Journal of medical virology. 2015, 87, 1899–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.-M.; Sheen, I.-S.; Lin, S.-M.; Liaw, Y.-F. Sex Difference in Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection: Studies of Serum HBeAg and Alanine Aminotransferase Levels in 10,431 Asymptomatic Chinese HBsAg Carriers. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1993, 16, 709–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.S.Y.; Covert, E.; Wilson, E.; Kottilil, S. Chronic Hepatitis B Infection: A Review. JAMA. 2018, 319, 1802–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, A.G.; Shamarina, S.; Hisham, M.; Hafiz, A.R.A. Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Hepatitis B Virus Infection In Lafia Metropolis, Nasarawa State, Nigeria. Afr J Infect Dis. 2025, 19, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Preventing perinatal hepatitis B virus transmission: a guide for introducing and strengthening hepatitis B birth dose vaccination; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Seto, W.-K.; Lo, Y.-R.; Pawlotsky, J.-M.; Yuen, M.-F. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection. The Lancet. 2018, 392, 2313–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athalye, S.; Khargekar, N.; Shinde, S.; Parmar, T.; Chavan, S.; Swamidurai, G.; et al. Exploring risk factors and transmission dynamics of Hepatitis B infection among Indian families: implications and perspective. Journal of Infection and Public Health. 2023, 16, 1109–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangowi, I.; Mirambo, M.M.; Kilonzo, S.B.; Mlewa, M.; Nyawale, H.; Majinge, D.; et al. Hepatitis B virus infection, associated factors, knowledge and vaccination status among household contacts of hepatitis B index cases in Mwanza, Tanzania. IJID Regions. 2024, 10, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofian, M.; Banifazl, M.; Ziai, M.; Aghakhani, A.; Farazi, A.A.; Ramezani, A. Intra-familial Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Arak, Central Iran. Iran J Pathol. 2016, 11, 328–333. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, C.E.; Ngimbi, P.; Boisson-Walsh, A.J.N.; Ntambua, S.; Matondo, J.; Tabala, M.; et al. Hepatitis B Virus Prevalence and Transmission in the Households of Pregnant Women in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2024, 11, ofae150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, S.; Buxton, J.A.; Afshar, K.; Copes, R.; Baharlou, S. Tattooing and risk of hepatitis B: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Public Health. 2012, 103, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, S.C.; Lee, Y.C.; Hashibe, M.; Dai, M.; Zheng, T.; Boffetta, P. Interaction between cigarette smoking and hepatitis B and C virus infection on the risk of liver cancer: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010, 19, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Baecker, A.; Wu, M.; Zhou, J.Y.; Yang, J.; Han, R.Q.; et al. Interaction between tobacco smoking and hepatitis B virus infection on the risk of liver cancer in a Chinese population. Int J Cancer. 2018, 142, 1560–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).