Submitted:

22 August 2024

Posted:

23 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

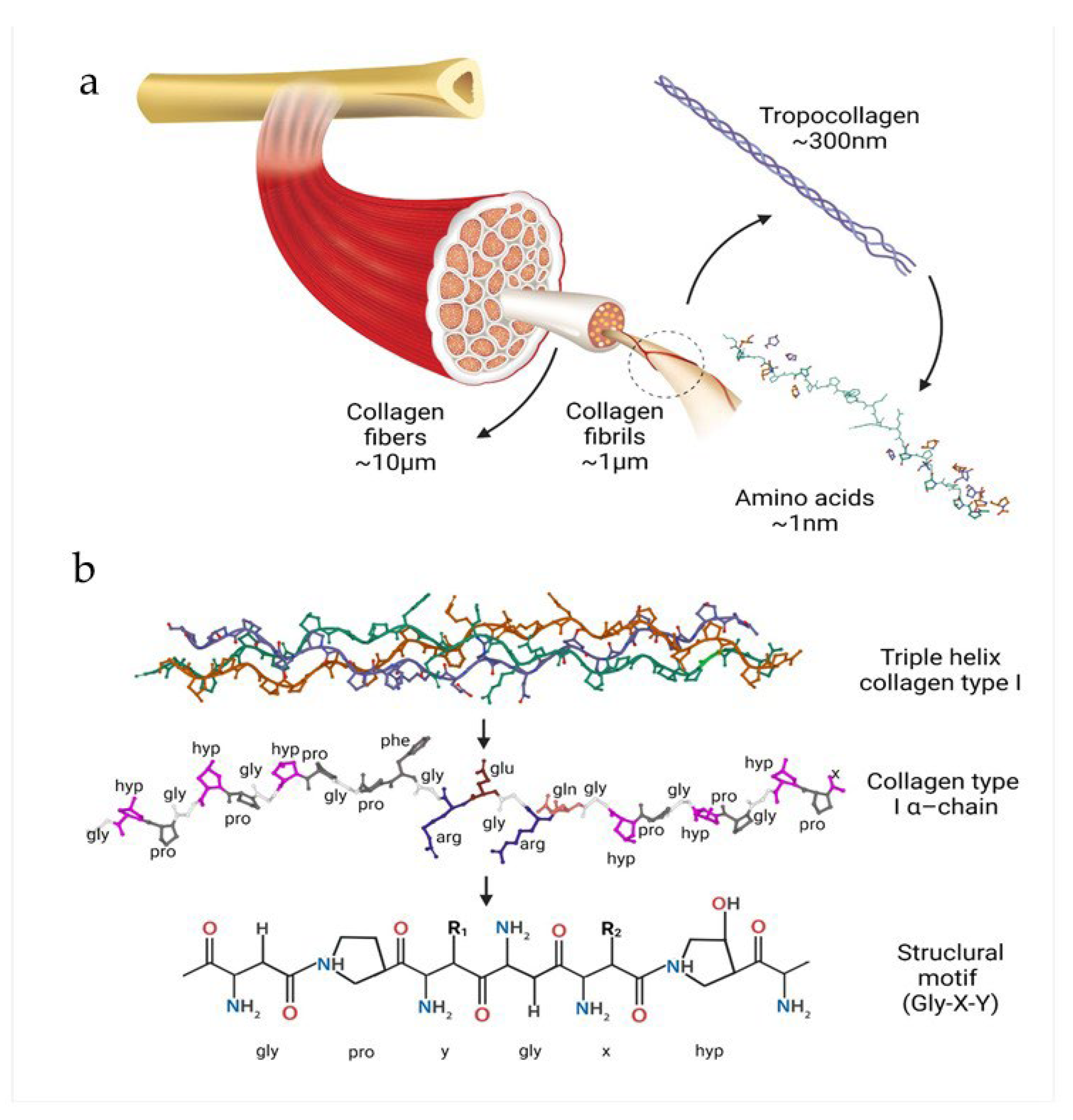

2. Characteristics of the Collagen

3.1. Structure and Properties

2.2. Types of Collagen and Their Origin

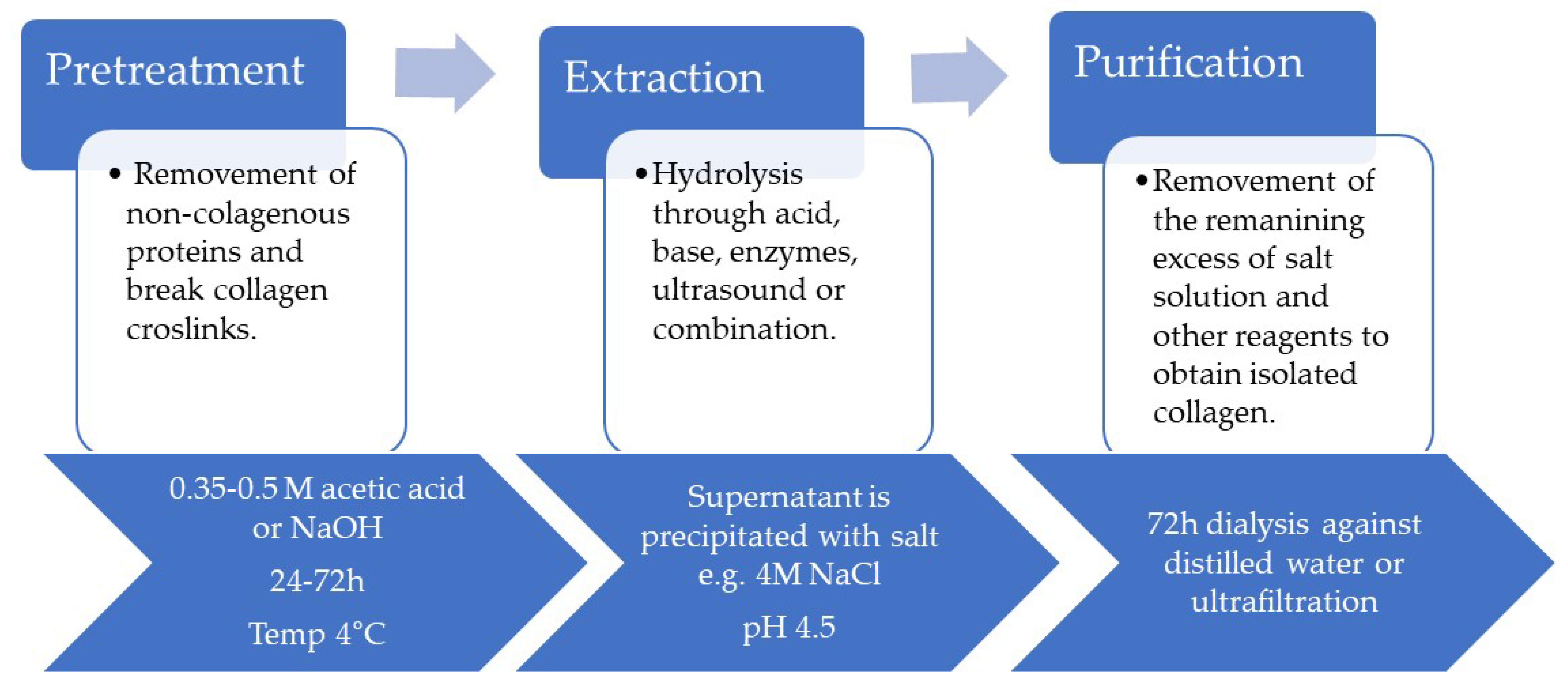

2.3. Methods of Obtaining

2.4. Native Collagen vs. Cross-Linked Collagen

3. Biomedical Properties of Collagen

3.1. Biocompatibility and Immunogenicity

3.2. Biodegradability of Collagen

3.1.1. Enzymatic Degradation of Collagen

3.1.1. Non-Enzymatic Degradation of Collagen

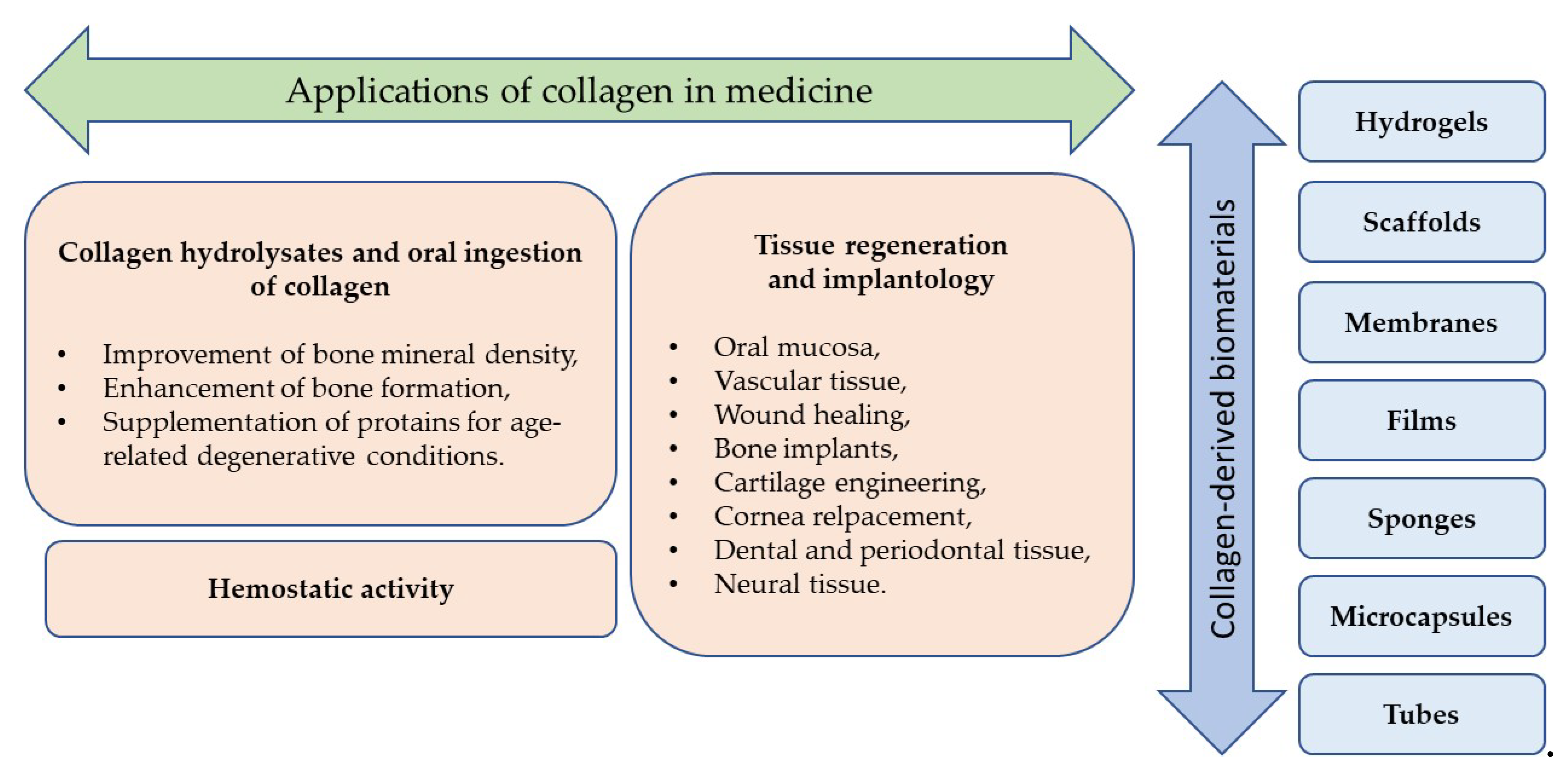

4. Collagen-Derived Biomaterials

4.1. Membranes

4.2. Scaffolds

4.3. Gels

4.4. Sponges

4.5. Films

4.6. Other Forms

5. Applications of Collagen in Medicine

5.1. Collagen Hydrolysates and Oral Ingestion Of Collagen

5.2. Tissue Regeneration and Implantology

5.2.1. Oral Mucosa

5.2.2. Vascular Tissue

5.2.3. Wound Healing

5.2.4. Bone

5.2.5. Cartilage

5.2.6. Cornea

5.2.7. Dental and Periodontal Tissue

5.2.8. Neural Tissue

5.3. Hemostatic Activity

6. Current Research Trends

6.1. Drug Delivery Systems Based on Collagen

6.2.3. D-Printing Of Collagen

6.3. Collagen and Stem Cells

6.4. Recombinant Human Collagen

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Todros, S.; Todesco, M.; Bagno, A. Biomaterials and Their Biomedical Applications: From Replacement to Regeneration. Processes 2021, 9, 1949.

- Williams, D.F. On the nature of biomaterials. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 5897-5909. [CrossRef]

- Biswal, T.; BadJena, S.K.; Pradhan, D. Sustainable biomaterials and their applications: A short review. Materials Today: Proceedings 2020, 30, 274-282. [CrossRef]

- Raghavendra, G.M.; Varaprasad, K.; Jayaramudu, T. Chapter 2 - Biomaterials: Design, Development and Biomedical Applications. In Nanotechnology Applications for Tissue Engineering, Thomas, S., Grohens, Y., Ninan, N., Eds. William Andrew Publishing: Oxford, 2015; pp. 21-44. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, V.; Brandalise, R.N.; Savaris, M. Biomaterials: Characteristics and Properties. In Engineering of Biomaterials, dos Santos, V., Brandalise, R.N., Savaris, M., Eds. Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 5-15. [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, H.R.; Bakhtiari, L.; Öchsner, A. Introduction. In Biomaterials and Their Applications, Reza Rezaie, H., Bakhtiari, L., Öchsner, A., Eds. Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015, pp. 1-18.; [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Benson, R. 8 - Polymeric Biomaterials. In Applied Plastics Engineering Handbook (Second Edition), Kutz, M., Ed. William Andrew Publishing: 2017; pp. 145-164. [CrossRef]

- Kulinets, I. 1 - Biomaterials and their applications in medicine. In Regulatory Affairs for Biomaterials and Medical Devices, Amato, S.F., Ezzell, R.M., Eds. Woodhead Publishing: 2015; pp. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Sorushanova, A.; Delgado, L.M.; Wu, Z.; Shologu, N.; Kshirsagar, A.; Raghunath, R.; Mullen, A.M.; Bayon, Y.; Pandit, A.; Raghunath, M., et al. The Collagen Suprafamily: From Biosynthesis to Advanced Biomaterial Development. Adv Mater 2019, 31, e1801651. [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.-S.; Ok, Y.-J.; Hwang, S.-Y.; Kwak, J.-Y.; Yoon, S. Marine Collagen as A Promising Biomaterial for Biomedical Applications. In Mar Drugs, 2019; Vol. 17.

- Lee, C.H.; Singla, A.; Lee, Y. Biomedical applications of collagen. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2001, 221, 1-22. [CrossRef]

- An, B.; Lin, Y.S.; Brodsky, B. Collagen interactions: Drug design and delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2016, 97, 69-84. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.M.; Gentile, P.; Chiono, V.; Ciardelli, G. Collagen for bone tissue regeneration. Acta Biomater 2012, 8, 3191-3200. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M.K.; Hahn, R.A. Collagens. Cell Tissue Res 2010, 339, 247-257. [CrossRef]

- Felician, F.F.; Xia, C.; Qi, W.; Xu, H. Collagen from Marine Biological Sources and Medical Applications. Chem Biodivers 2018, 15, e1700557. [CrossRef]

- Prajaputra, V.; Isnaini, N.; Maryam, S.; Ernawati, E.; Deliana, F.; Haridhi, H.A.; Fadli, N.; Karina, S.; Agustina, S.; Nurfadillah, N., et al. Exploring marine collagen: Sustainable sourcing, extraction methods, and cosmetic applications. South African Journal of Chemical Engineering 2024, 47, 197-211. [CrossRef]

- Alcaide-Ruggiero, L.; Molina-Hernandez, V.; Granados, M.M.; Dominguez, J.M. Main and Minor Types of Collagens in the Articular Cartilage: The Role of Collagens in Repair Tissue Evaluation in Chondral Defects. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.; Bächinger, H.P. Structure, stability and folding of the collagen triple helix. Topics in Current Chemistry 2005, 247, 7-33. [CrossRef]

- Ottani, V.; Raspanti, M.; Ruggeri, A. Collagen structure and functional implications. Micron 2001, 32, 251-260. [CrossRef]

- Karsdal, M.A.; Leeming, D.J.; Henriksen, K.; Bay-Jensen, A.C. Biochemistry of Collagens, Laminins and Elastin; Academic Press: 2016; 10.1016/c2015-0-05547-2pp. 1-238.

- Amirrah, I.N.; Lokanathan, Y.; Zulkiflee, I.; Wee, M.; Motta, A.; Fauzi, M.B. A Comprehensive Review on Collagen Type I Development of Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering: From Biosynthesis to Bioscaffold. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Ren, Y.; Emmert, S.; Vuckovic, I.; Stojanovic, S.; Najman, S.; Schnettler, R.; Barbeck, M.; Schenke-Layland, K.; Xiong, X. The Use of Collagen-Based Materials in Bone Tissue Engineering. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Shoulders, M.D.; Raines, R.T. Collagen structure and stability. Annu Rev Biochem 2009, 78, 929-958. [CrossRef]

- Collier, T.A.; Nash, A.; Birch, H.L.; de Leeuw, N.H. Effect on the mechanical properties of type I collagen of intra-molecular lysine-arginine derived advanced glycation end-product cross-linking. J Biomech 2018, 67, 55-61. [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Quan, T. Oxidative Stress and Human Skin Connective Tissue Aging. Cosmetics 2016, 3. [CrossRef]

- Lindholm, M.; Manon-Jensen, T.; Karsdal, M.A. Chapter 14 - Type XIV collagen. Biochemistry of Collagens, Laminins and Elastin (Second Edition) 2019, 121-125.

- Fontenele, F.F.; Bouklas, N. Understanding the inelastic response of collagen fibrils: A viscoelastic-plastic constitutive model. Acta Biomater 2023, 163, 78-90. [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.; Lewis, E.D.; Zakaria, N.; Pelipyagina, T.; Guthrie, N. A randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel study to evaluate the efficacy of a freshwater marine collagen on skin wrinkles and elasticity. J Cosmet Dermatol 2021, 20, 825-834. [CrossRef]

- Chambers, E.S.; Vukmanovic-Stejic, M. Skin barrier immunity and ageing. Immunology 2020, 160, 116-125. [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, M.; Sricholpech, M.; Terajima, M.; Tomer, K.B.; Perdivara, I. Glycosylation of Type I Collagen. Methods Mol Biol 2019, 1934, 127-144. [CrossRef]

- Oba, C.; Ohara, H.; Morifuji, M.; Ito, K.; Ichikawa, S.; Kawahata, K.; Koga, J. Collagen hydrolysate intake improves the loss of epidermal barrier function and skin elasticity induced by UVB irradiation in hairless mice. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed 2013, 29, 204-211. [CrossRef]

- Sirbu, R.; Paris, S.; Lupașcu, N.; Cadar, E.; Mustafa, A.; Cherim, M. Collagen Sources and Areas of Use. European Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 2016, 4, 8-13. [CrossRef]

- Avila Rodriguez, M.I.; Rodriguez Barroso, L.G.; Sanchez, M.L. Collagen: A review on its sources and potential cosmetic applications. J Cosmet Dermatol 2018, 17, 20-26. [CrossRef]

- Jafari, H.; Lista, A.; Siekapen, M.M.; Ghaffari-Bohlouli, P.; Nie, L.; Alimoradi, H.; Shavandi, A. Fish Collagen: Extraction, Characterization, and Applications for Biomaterials Engineering. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 2230. [CrossRef]

- Silvipriya, K.; Kumar, K.; Bhat, A.; Kumar, B.; John, A.; Lakshmanan, P. Collagen: Animal Sources and Biomedical Application. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science 2015, 5, 123-127. [CrossRef]

- Coppola, D.; Oliviero, M.; Vitale, G.A.; Lauritano, C.; D'Ambra, I.; Iannace, S.; de Pascale, D. Marine Collagen from Alternative and Sustainable Sources: Extraction, Processing and Applications. Mar Drugs 2020, 18. [CrossRef]

- Matinong, A.M.E.; Chisti, Y.; Pickering, K.L.; Haverkamp, R.G. Collagen Extraction from Animal Skin. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Davison-Kotler, E.; Marshall, W.S.; Garcia-Gareta, E. Sources of Collagen for Biomaterials in Skin Wound Healing. Bioengineering (Basel) 2019, 6. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. A Review of the Effects of Collagen Treatment in Clinical Studies. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13, 3868. [CrossRef]

- Jadach, B.; Mielcarek, Z.; Osmalek, T. Use of Collagen in Cosmetic Products. Curr Issues Mol Biol 2024, 46, 2043-2070. [CrossRef]

- Calleja-Agius, J.; Brincat, M.; Borg, M. Skin connective tissue and ageing. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2013, 27, 727-740. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.S.; Cho, H.H.; Cho, S.; Lee, S.R.; Shin, M.H.; Chung, J.H. Supplementating with dietary astaxanthin combined with collagen hydrolysate improves facial elasticity and decreases matrix metalloproteinase-1 and -12 expression: a comparative study with placebo. J Med Food 2014, 17, 810-816. [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.H.; Moreira-Silva, J.; Marques, A.L.; Domingues, A.; Bayon, Y.; Reis, R.L. Marine origin collagens and its potential applications. Mar Drugs 2014, 12, 5881-5901. [CrossRef]

- Sionkowska, A.; Lewandowska, K.; Adamiak, K. The Influence of UV Light on Rheological Properties of Collagen Extracted from Silver Carp Skin. Materials (Basel) 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, L.; Yao, J.; Ma, Y.-Y.; Chen, J.-M.; Lu, T.-B. Improving the Solubility and Bioavailability of Apixaban via Apixaban–Oxalic Acid Cocrystal. Crystal Growth & Design 2016, 16, 2923-2930. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Shu, Z. The extraction of collagen protein from pigskin. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 2014, 6, 683–687.

- Sionkowska, A.; Adamiak, K.; Musial, K.; Gadomska, M. Collagen Based Materials in Cosmetic Applications: A Review. Materials (Basel) 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, L.; Yi, R.; Xu, N.; Gao, R.; Hong, B. Extraction and characterization of acid-soluble collagen from scales and skin of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). LWT - Food Science and Technology 2016, 66, 453-459. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.M.; Prestes Dornelles, R.; Mello, R.; Kubota, E.H.; Mazutti, M.; Kempka, A.; Demiate, I. Collagen extraction process. 2016, 23, 913-922.

- Pal, G.K.; Suresh, P.V. Sustainable valorisation of seafood by-products: Recovery of collagen and development of collagen-based novel functional food ingredients. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2016, 37, 201-215. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wei, G.; Li, T.; Hu, J.; Lu, N.; Regenstein, J.M.; Zhou, P. Effects of alkaline pretreatments and acid extraction conditions on the acid-soluble collagen from grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) skin. Food Chem 2015, 172, 836-843. [CrossRef]

- Ran, X.G.; Wang, L.Y. Use of ultrasonic and pepsin treatment in tandem for collagen extraction from meat industry by-products. Journal of the science of food and agriculture 2014, 94, 585-590. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.B.; Su, D.H.; Liu, P.; Ma, Y.Q.; Shao, Z.Z.; Dong, J. Shape-memory collagen scaffold for enhanced cartilage regeneration: native collagen versus denatured collagen. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2018, 26, 1389-1399. [CrossRef]

- Dill, V.; Morgelin, M. Biological dermal templates with native collagen scaffolds provide guiding ridges for invading cells and may promote structured dermal wound healing. Int Wound J 2020, 17, 618-630. [CrossRef]

- Eekhoff, J.D.; Fang, F.; Lake, S.P. Multiscale mechanical effects of native collagen cross-linking in tendon. Connect Tissue Res 2018, 59, 410-422. [CrossRef]

- Jansen, K.A.; Licup, A.J.; Sharma, A.; Rens, R.; MacKintosh, F.C.; Koenderink, G.H. The Role of Network Architecture in Collagen Mechanics. Biophys J 2018, 114, 2665-2678. [CrossRef]

- Adamiak, K.; Sionkowska, A. Current methods of collagen cross-linking: Review. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 161, 550-560. [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, R.; Yaghoobi, H.; Frampton, J. A Comparative Study of the Effects of Different Crosslinking Methods on the Physicochemical Properties of Collagen Multifilament Bundles. Chemphyschem 2024, 25, e202400259. [CrossRef]

- Sallent, I.; Capella-Monsonis, H.; Zeugolis, D.I. Production and Characterization of Chemically Cross-Linked Collagen Scaffolds. Methods Mol Biol 2019, 1944, 23-38. [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, C.; Buhren, B.A.; Bunemann, E.; Schrumpf, H.; Homey, B.; Frykberg, R.G.; Lurie, F.; Gerber, P.A. A novel native collagen dressing with advantageous properties to promote physiological wound healing. J Wound Care 2016, 25, 713-720. [CrossRef]

- Bohm, S.; Strauss, C.; Stoiber, S.; Kasper, C.; Charwat, V. Impact of Source and Manufacturing of Collagen Matrices on Fibroblast Cell Growth and Platelet Aggregation. Materials (Basel) 2017, 10. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Pei, Y.; Tang, K.; Albu-Kaya, M.G. Structure, extraction, processing, and applications of collagen as an ideal component for biomaterials - a review. Collagen and Leather 2023, 5, 20. [CrossRef]

- Joyce, K.; Fabra, G.T.; Bozkurt, Y.; Pandit, A. Bioactive potential of natural biomaterials: identification, retention and assessment of biological properties. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 122. [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Zhang, D.; Macedo, M.H.; Cui, W.; Sarmento, B.; Shen, G. Advanced Collagen-Based Biomaterials for Regenerative Biomedicine. Advanced Functional Materials 2018, 29, 1804943. [CrossRef]

- Colchester, A.C.; Colchester, N.T. The origin of bovine spongiform encephalopathy: the human prion disease hypothesis. Lancet 2005, 366, 856-861. [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Sun, F.; Zou, Q.; Huang, J.; Zuo, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Cheng, L.; Man, Y.; Yang, F., et al. Fish Collagen and Hydroxyapatite Reinforced Poly(lactide- co-glycolide) Fibrous Membrane for Guided Bone Regeneration. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 2058-2067. [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, M.; Toda, M.; Ebihara, T.; Irie, S.; Hori, H.; Imai, A.; Yanagida, M.; Miyazawa, H.; Ohsuna, H.; Ikezawa, Z., et al. IgE antibody to fish gelatin (type I collagen) in patients with fish allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000, 106, 579-584. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; He, C.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, S.; Mo, X. Evaluation of biocompatibility and immunogenicity of micro/nanofiber materials based on tilapia skin collagen. J Biomater Appl 2019, 33, 1118-1127. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.Y.; Glattauer, V.; Ramshaw, J.A.; Werkmeister, J.A. Evaluation of the immunogenicity and cell compatibility of avian collagen for biomedical applications. J Biomed Mater Res A 2010, 93, 1235-1244. [CrossRef]

- Hassanbhai, A.M.; Lau, C.S.; Wen, F.; Jayaraman, P.; Goh, B.T.; Yu, N.; Teoh, S.H. In Vivo Immune Responses of Cross-Linked Electrospun Tilapia Collagen Membrane<sup/>. Tissue Eng Part A 2017, 23, 1110-1119. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Wang, N.; Xue, Y.; Ding, T.; Liu, X.; Mo, X.; Sun, J. Electrospun tilapia collagen nanofibers accelerating wound healing via inducing keratinocytes proliferation and differentiation. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2016, 143, 415-422. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hu, C.; Gao, D.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, X.; Hu, X.; Gong, S.; Li, L.; Zhang, L. Pharmacokinetics and bioequivalence of generic and branded abiraterone acetate tablet: a single-dose, open-label, and replicate designed study in healthy Chinese male volunteers. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2019, 83, 509-517. [CrossRef]

- Hulmes, D.J.S. Collagen Diversity, Synthesis and Assembly. In Collagen, Fratzl, P., Ed. Springer US: Boston, MA, 2008; 10.1007/978-0-387-73906-9_2pp. 15-47.

- Nagase, H.; Woessner, J.F., Jr. Matrix metalloproteinases. J Biol Chem 1999, 274, 21491-21494. [CrossRef]

- Fields, G.B. Mechanisms of Action of Novel Drugs Targeting Angiogenesis-Promoting Matrix Metalloproteinases. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 1278. [CrossRef]

- Costello, L.; Dicolandrea, T.; Tasseff, R.; Isfort, R.; Bascom, C.; von Zglinicki, T.; Przyborski, S. Tissue engineering strategies to bioengineer the ageing skin phenotype in vitro. Aging Cell 2022, 21, e13550. [CrossRef]

- Bohlender, J.M.; Franke, S.; Stein, G.; Wolf, G. Advanced glycation end products and the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2005, 289, F645-659. [CrossRef]

- Reiser, K.M. Nonenzymatic glycation of collagen in aging and diabetes. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1991, 196, 17-29. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.J.; Paul, R.G.; Knott, L. Mechanisms of maturation and ageing of collagen. Mech Ageing Dev 1998, 106, 1-56. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Chen, R.; Wang, J.; Lu, J.; Yu, T.; Wu, X.; Xu, S.; Li, Z.; Jie, C.; Cao, R., et al. Biphasic fish collagen scaffold for osteochondral regeneration. Mater Design 2020, 195, 108947. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gu, J.; Fan, D. Fabrication of High-Strength and Porous Hybrid Scaffolds Based on Nano-Hydroxyapatite and Human-Like Collagen for Bone Tissue Regeneration. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 61. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Jin, Y.; Ying, X.; Wu, Q.; Yao, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Ma, G.; Wang, X. Development of an antimicrobial peptide-loaded mineralized collagen bone scaffold for infective bone defect repair. Regenerative Biomaterials 2020, 7, 515-525. [CrossRef]

- Terada, M.; Izumi, K.; Ohnuki, H.; Saito, T.; Kato, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Kawano, Y.; Nozawa-Inoue, K.; Kashiwazaki, H.; Ikoma, T., et al. Construction and characterization of a tissue-engineered oral mucosa equivalent based on a chitosan-fish scale collagen composite. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2012, 100, 1792-1802. [CrossRef]

- Chandika, P.; Ko, S.C.; Oh, G.W.; Heo, S.Y.; Nguyen, V.T.; Jeon, Y.J.; Lee, B.; Jang, C.H.; Kim, G.; Park, W.S., et al. Fish collagen/alginate/chitooligosaccharides integrated scaffold for skin tissue regeneration application. Int J Biol Macromol 2015, 81, 504-513. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.W.; Huang, S.S.; Yu, W.X.; Hsu, Y.W.; Hsu, F.Y. Collagen Scaffolds Containing Hydroxyapatite-CaO Fiber Fragments for Bone Tissue Engineering. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1174. [CrossRef]

- Bermueller, C.; Schwarz, S.; Elsaesser, A.F.; Sewing, J.; Baur, N.; von Bomhard, A.; Scheithauer, M.; Notbohm, H.; Rotter, N. Marine collagen scaffolds for nasal cartilage repair: prevention of nasal septal perforations in a new orthotopic rat model using tissue engineering techniques. Tissue Eng Part A 2013, 19, 2201-2214. [CrossRef]

- Zak, L.; Albrecht, C.; Wondrasch, B.; Widhalm, H.; Vekszler, G.; Trattnig, S.; Marlovits, S.; Aldrian, S. Results 2 Years After Matrix-Associated Autologous Chondrocyte Transplantation Using the Novocart 3D Scaffold: An Analysis of Clinical and Radiological Data. Am J Sports Med 2014, 42, 1618-1627. [CrossRef]

- Szychlinska, M.A.; Calabrese, G.; Ravalli, S.; Dolcimascolo, A.; Castrogiovanni, P.; Fabbi, C.; Puglisi, C.; Lauretta, G.; Di Rosa, M.; Castorina, A., et al. Evaluation of a Cell-Free Collagen Type I-Based Scaffold for Articular Cartilage Regeneration in an Orthotopic Rat Model. Materials (Basel) 2020, 13, 2369. [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Luo, D.; Qiao, J.; Guo, J.; He, D.; Jin, S.; Tang, L.; Wang, Y.; Shi, X.; Mao, J., et al. A hierarchical bilayer architecture for complex tissue regeneration. Bioact Mater 2022, 10, 93-106. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, S.; Luo, P.; Deng, S.; Shan, Z.; Fang, J.; Liu, X.; Xie, J.; Liu, R.; Wu, S., et al. Optimizing the bio-degradability and biocompatibility of a biogenic collagen membrane through cross-linking and zinc-doped hydroxyapatite. Acta Biomater 2022, 143, 159-172. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.J.; Kim, H.J.; Bae, E.B.; Cho, W.T.; Choi, Y.; Hwang, S.H.; Jeong, C.M.; Huh, J.B. Evaluation of 1-Ethyl-3-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl) Carbodiimide Cross-Linked Collagen Membranes for Guided Bone Regeneration in Beagle Dogs. Materials (Basel) 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- Allan, B.; Ruan, R.; Landao-Bassonga, E.; Gillman, N.; Wang, T.; Gao, J.; Ruan, Y.; Xu, Y.; Lee, C.; Goonewardene, M., et al. Collagen Membrane for Guided Bone Regeneration in Dental and Orthopedic Applications. Tissue Eng Part A 2021, 27, 372-381. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.K.; Yeo, K.P.; Chun, Y.Y.; Tan, T.T.Y.; Tan, N.S.; Angeli, V.; Choong, C. Fish scale-derived collagen patch promotes growth of blood and lymphatic vessels in vivo. Acta Biomater 2017, 63, 246-260. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-H.; Hsieh, D.-J.; Periasamy, S.; Chuang, C.-T.; Tseng, F.-W.; Kuo, J.-C.; Tarng, Y.-W. Regenerative porcine dermal collagen matrix developed by supercritical carbon dioxide extraction technology: Role in accelerated wound healing. Materialia 2020, 9, 100576. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Giusti, G.; Friedrich, P.F.; Archibald, S.J.; Kemnitzer, J.E.; Patel, J.; Desai, N.; Bishop, A.T.; Shin, A.Y. The effect of collagen nerve conduits filled with collagen-glycosaminoglycan matrix on peripheral motor nerve regeneration in a rat model. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012, 94, 2084-2091. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Li, L.; Li, D.; Takagi, Y.; Zhang, X. Properties of Grass Carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) Collagen and Gel for Application in Biomaterials. In Gels, 2022; Vol. 8.

- Shang, Y.; Yao, S.; Qiao, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Huang, Z.; Gu, Q.; Wang, N.; Peng, C. Evaluations of Marine Collagen Peptides from tilapia skin on experimental oral ulcer model of mice. Materials Today Communications 2021, 26, 101893. [CrossRef]

- Moeinzadeh, S.; Park, Y.; Lin, S.; Yang, Y.P. In-situ stable injectable collagen-based hydrogels for cell and growth factor delivery. Materialia (Oxf) 2021, 15. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes-Cunha, G.M.; Chen, K.M.; Chen, F.; Le, P.; Han, J.H.; Mahajan, L.A.; Lee, H.J.; Na, K.S.; Myung, D. In situ-forming collagen hydrogel crosslinked via multi-functional PEG as a matrix therapy for corneal defects. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 16671. [CrossRef]

- Xeroudaki, M.; Thangavelu, M.; Lennikov, A.; Ratnayake, A.; Bisevac, J.; Petrovski, G.; Fagerholm, P.; Rafat, M.; Lagali, N. A porous collagen-based hydrogel and implantation method for corneal stromal regeneration and sustained local drug delivery. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 16936. [CrossRef]

- Lazurko, C.; Khatoon, Z.; Goel, K.; Sedlakova, V.; Eren Cimenci, C.; Ahumada, M.; Zhang, L.; Mah, T.F.; Franco, W.; Suuronen, E.J., et al. Multifunctional Nano and Collagen-Based Therapeutic Materials for Skin Repair. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2020, 6, 1124-1134. [CrossRef]

- Ge, B.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Liu, H.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, N.; Qin, S. Comprehensive Assessment of Nile Tilapia Skin (Oreochromis niloticus) Collagen Hydrogels for Wound Dressings. Mar Drugs 2020, 18, 178. [CrossRef]

- Mredha, M.T.I.; Kitamura, N.; Nonoyama, T.; Wada, S.; Goto, K.; Zhang, X.; Nakajima, T.; Kurokawa, T.; Takagi, Y.; Yasuda, K., et al. Anisotropic tough double network hydrogel from fish collagen and its spontaneous in vivo bonding to bone. Biomaterials 2017, 132, 85-95. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes-Cunha, G.M.; Brunel, L.G.; Arboleda, A.; Manche, A.; Seo, Y.A.; Logan, C.; Chen, F.; Heilshorn, S.C.; Myung, D. Collagen Gels Crosslinked by Photoactivation of Riboflavin for the Repair and Regeneration of Corneal Defects. ACS Applied Bio Materials 2023, 6, 1787-1797. [CrossRef]

- Rosenquist, J.; Folkesson, M.; Höglund, L.; Pupkaite, J.; Hilborn, J.; Samanta, A. An Injectable, Shape-Retaining Collagen Hydrogel Cross-linked Using Thiol-Maleimide Click Chemistry for Sealing Corneal Perforations. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2023, 15, 34407-34418. [CrossRef]

- Xeroudaki, M.; Rafat, M.; Moustardas, P.; Mukwaya, A.; Tabe, S.; Bellisario, M.; Peebo, B.; Lagali, N. A double-crosslinked nanocellulose-reinforced dexamethasone-loaded collagen hydrogel for corneal application and sustained anti-inflammatory activity. Acta Biomaterialia 2023, 172, 234-248. [CrossRef]

- Adamiak, K.; Lewandowska, K.; Sionkowska, A. The Infuence of Salicin on Rheological and Film-Forming Properties of Collagen. In Molecules, 2021; Vol. 26.

- Tenorová, K.; Masteiková, R.; Pavloková, S.; Kostelanská, K.; Bernatonienė, J.; Vetchý, D. Formulation and Evaluation of Novel Film Wound Dressing Based on Collagen/Microfibrillated Carboxymethylcellulose Blend. In Pharmaceutics, 2022; Vol. 14.

- Abdullah, J.A.; Yemişken, E.; Guerrero, A.; Romero, A. Marine Collagen-Based Antibacterial Film Reinforced with Graphene and Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. In International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023; Vol. 24.

- Wang, L.; Qu, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, K.; Qin, S. Effects and metabolism of fish collagen sponge in repairing acute wounds of rat skin. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2023, 11, 1087139. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Song, W.; Chen, A.; Liu, J.; Xuan, X. Collagen sponge prolongs taurine release for improved wound healing through inflammation inhibition and proliferation stimulation. Ann Transl Med 2021, 9, 1010. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Li, M.; Shi, P.; Gao, Y.; Ma, J.; Li, Y.; Huang, L.; Yang, Z.; Yang, L. Polydopamine-modified collagen sponge scaffold as a novel dermal regeneration template with sustained release of platelet-rich plasma to accelerate skin repair: A one-step strategy. Bioact Mater 2021, 6, 2613-2628. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gao, K.; Liu, S.; Wang, S.; Elango, J.; Bao, B.; Dong, J.; Liu, N.; Wu, W. Fish Collagen Surgical Compress Repairing Characteristics on Wound Healing Process In Vivo. Mar Drugs 2019, 17, 33. [CrossRef]

- Yeung, P.; Cheng, K.H.; Yan, C.H.; Chan, B.P. Collagen microsphere based 3D culture system for human osteoarthritis chondrocytes (hOACs). Sci Rep 2019, 9, 12453. [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, Y.; Haraguchi, R.; Aoki, S.; Oishi, Y.; Narita, T. Effect of UV Irradiation of Pre-Gel Solutions on the Formation of Collagen Gel Tubes. Gels 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, Y.; Haraguchi, R.; Nakao, R.; Aoki, S.; Oishi, Y.; Narita, T. One-Pot Preparation of Collagen Tubes Using Diffusing Gelation. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 22872-22878. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Yang, P.; Zhou, C.; Li, S.; Hong, P. Marine Collagen Peptides from the Skin of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus): Characterization and Wound Healing Evaluation. Mar Drugs 2017, 15, 102. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Fan, L.; Alkildani, S.; Liu, L.; Emmert, S.; Najman, S.; Rimashevskiy, D.; Schnettler, R.; Jung, O.; Xiong, X., et al. Barrier Membranes for Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR): A Focus on Recent Advances in Collagen Membranes. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Sbricoli, L.; Guazzo, R.; Annunziata, M.; Gobbato, L.; Bressan, E.; Nastri, L. Selection of Collagen Membranes for Bone Regeneration: A Literature Review. In Materials, 2020; Vol. 13.

- Mizraji, G.; Davidzohn, A.; Gursoy, M.; Gursoy, U.; Shapira, L.; Wilensky, A. Membrane barriers for guided bone regeneration: An overview of available biomaterials. Periodontol 2000 2023, 93, 56-76. [CrossRef]

- Calciolari, E.; Ravanetti, F.; Strange, A.; Mardas, N.; Bozec, L.; Cacchioli, A.; Kostomitsopoulos, N.; Donos, N. Degradation pattern of a porcine collagen membrane in an in vivo model of guided bone regeneration. J Periodontal Res 2018, 53, 430-439. [CrossRef]

- Radenković, M.; Alkildani, S.; Stoewe, I.; Bielenstein, J.; Sundag, B.; Bellmann, O.; Jung, O.; Najman, S.; Stojanović, S.; Barbeck, M. Comparative In Vivo Analysis of the Integration Behavior and Immune Response of Collagen-Based Dental Barrier Membranes for Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR). In Membranes, 2021; Vol. 11.

- Wu, Y.; Chen, S.; Luo, P.; Deng, S.; Shan, Z.; Fang, J.; Liu, X.; Xie, J.; Liu, R.; Wu, S., et al. Optimizing the bio-degradability and biocompatibility of a biogenic collagen membrane through cross-linking and zinc-doped hydroxyapatite. Acta Biomater 2022, 143, 159-172. [CrossRef]

- Rico-Llanos, G.A.; Borrego-Gonzalez, S.; Moncayo-Donoso, M.; Becerra, J.; Visser, R. Collagen Type I Biomaterials as Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Kolodziejska, B.; Kaflak, A.; Kolmas, J. Biologically Inspired Collagen/Apatite Composite Biomaterials for Potential Use in Bone Tissue Regeneration-A Review. Materials (Basel) 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gu, J.; Fan, D. Fabrication of High-Strength and Porous Hybrid Scaffolds Based on Nano-Hydroxyapatite and Human-Like Collagen for Bone Tissue Regeneration. In Polymers, 2020; Vol. 12.

- Furtado, M.; Chen, L.; Chen, Z.; Chen, A.; Cui, W. Development of fish collagen in tissue regeneration and drug delivery. Engineered Regeneration 2022, 3, 217-231. [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.; Clegg, J.R.; Anselmo, A.C.; Mitragotri, S. Hydrogels in the clinic. Bioengineering & Translational Medicine 2020, 5, e10158. [CrossRef]

- International Union of Pure and Applied, C. reference method. In The IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2014; 10.1351/goldbook.R05231.

- Ribeiro, M.; Simões, M.; Vitorino, C.; Mascarenhas-Melo, F. Hydrogels in Cutaneous Wound Healing: Insights into Characterization, Properties, Formulation and Therapeutic Potential. In Gels, 2024; Vol. 10.

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jin, M.; Lin, X.; Zhuang, Z.; Guo, K.; Zhang, T.; Tan, W. Application of Collagen-Based Hydrogel in Skin Wound Healing. Gels 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Liu, G.; Wang, L.; Yang, Q.; Liao, F.; Yang, X.; Xiao, B.; Duan, L. Synthesis and Properties of Injectable Hydrogel for Tissue Filling. In Pharmaceutics, 2024; Vol. 16.

- Hong, H.; Fan, H.; Chalamaiah, M.; Wu, J. Preparation of low-molecular-weight, collagen hydrolysates (peptides): Current progress, challenges, and future perspectives. Food Chem 2019, 301, 125222. [CrossRef]

- T, W.; L, L.; N, C.; P, C.; K, T.; A, G. Efficacy of Oral Collagen in Joint Pain - Osteoarthritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Journal of Arthritis 2017, 06. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, B.; Song, S.; Ma, M.; Si, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, B.; Feng, K.; Wu, J.; Guo, Y. Bovine collagen peptides compounds promote the proliferation and differentiation of MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblasts. PLoS One 2014, 9, e99920. [CrossRef]

- Y, K. Effects of Collagen Ingestion and their Biological Significance. Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences 2016, 06. [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, T.; Nanbu, P.N.; Kurokawa, M. Distribution of prolylhydroxyproline and its metabolites after oral administration in rats. Biol Pharm Bull 2012, 35, 422-427. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe-Kamiyama, M.; Shimizu, M.; Kamiyama, S.; Taguchi, Y.; Sone, H.; Morimatsu, F.; Shirakawa, H.; Furukawa, Y.; Komai, M. Absorption and effectiveness of orally administered low molecular weight collagen hydrolysate in rats. J Agric Food Chem 2010, 58, 835-841. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, M.; Liang, R.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. Oral administration of marine collagen peptides prepared from chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) improves wound healing following cesarean section in rats. Food Nutr Res 2015, 59, 26411. [CrossRef]

- McAlindon, T.E.; Nuite, M.; Krishnan, N.; Ruthazer, R.; Price, L.L.; Burstein, D.; Griffith, J.; Flechsenhar, K. Change in knee osteoarthritis cartilage detected by delayed gadolinium enhanced magnetic resonance imaging following treatment with collagen hydrolysate: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011, 19, 399-405. [CrossRef]

- Konig, D.; Oesser, S.; Scharla, S.; Zdzieblik, D.; Gollhofer, A. Specific Collagen Peptides Improve Bone Mineral Density and Bone Markers in Postmenopausal Women-A Randomized Controlled Study. Nutrients 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sugihara, F.; Suzuki, K.; Inoue, N.; Venkateswarathirukumara, S. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, clinical study on the effectiveness of collagen peptide on osteoarthritis. Journal of the science of food and agriculture 2015, 95, 702-707. [CrossRef]

- Centner, C.; Zdzieblik, D.; Roberts, L.; Gollhofer, A.; Konig, D. Effects of Blood Flow Restriction Training with Protein Supplementation on Muscle Mass And Strength in Older Men. J Sports Sci Med 2019, 18, 471-478.

- Zdzieblik, D.; Oesser, S.; Baumstark, M.W.; Gollhofer, A.; Konig, D. Collagen peptide supplementation in combination with resistance training improves body composition and increases muscle strength in elderly sarcopenic men: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Nutr 2015, 114, 1237-1245. [CrossRef]

- Blidi, O.; El Omari, N.; Balahbib, A.; Ghchime, R.; Ibrahimi, A.; Bouyahya, A.; Chokairi, O.; Barkiyou, M. Extraction Methods, Characterization and Biomedical Applications of Collagen: a Review. Biointerface Research in Applied Chemistry 2021, 11, 13587-13613. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yang, L.; Wang, G.; Han, L.; Chen, K.; Liu, P.; Xu, S.; Li, D.; Xie, Z.; Mo, X., et al. Biocompatibility, hemostatic properties, and wound healing evaluation of tilapia skin collagen sponges. Journal of Bioactive and Compatible Polymers 2020, 36, 44-58. [CrossRef]

- Rana, D.; Desai, N.; Salave, S.; Karunakaran, B.; Giri, J.; Benival, D.; Gorantla, S.; Kommineni, N. Collagen-Based Hydrogels for the Eye: A Comprehensive Review. Gels 2023, 9, 643. [CrossRef]

- Boni, R.; Ali, A.; Shavandi, A.; Clarkson, A.N. Current and novel polymeric biomaterials for neural tissue engineering. J Biomed Sci 2018, 25, 90. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Li, B.; Song, W.; Zhang, K.; Fan, Y.; Hou, H. Comprehensive assessment of Nile tilapia skin collagen sponges as hemostatic dressings. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2020, 109, 110532. [CrossRef]

- Arun, A.; Malrautu, P.; Laha, A.; Luo, H.; Ramakrishna, S. Collagen Nanoparticles in Drug Delivery Systems and Tissue Engineering. In Applied Sciences, 2021; Vol. 11.

- El-Sawah, A.A.; El-Naggar, N.E.; Eldegla, H.E.; Soliman, H.M. Bionanofactory for green synthesis of collagen nanoparticles, characterization, optimization, in-vitro and in-vivo anticancer activities. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 6328. [CrossRef]

- Nicklas, M.; Schatton, W.; Heinemann, S.; Hanke, T.; Kreuter, J. Preparation and characterization of marine sponge collagen nanoparticles and employment for the transdermal delivery of 17beta-estradiol-hemihydrate. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 2009, 35, 1035-1042. [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, M.; Hamouda, D.; Khedr, S.M.; Mostafa, H.M.; Saeed, H.; Ghareeb, A.Z. Nanoparticles fabricated from the bioactive tilapia scale collagen for wound healing: Experimental approach. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0282557. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.A.; Akhter, J.; Aarzoo; Junaid Bashir, D.; Manzoor, S.; Rastogi, S.; Arora, I.; Aggarwal, N.B.; Samim, M. Resveratrol loaded nanoparticles attenuate cognitive impairment and inflammatory markers in PTZ-induced kindled mice. Int Immunopharmacol 2021, 101, 108287. [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.M.; Shalaby, M.A.; Saeed, H.; Mostafa, H.M.; Hamouda, D.G.; Nounou, H. Theophylline-encapsulated Nile Tilapia fish scale-based collagen nanoparticles effectively target the lungs of male Sprague-Dawley rats. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 4871. [CrossRef]

- Ruszczak, Z.; Friess, W. Collagen as a carrier for on-site delivery of antibacterial drugs. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2003, 55, 1679-1698. [CrossRef]

- Tihan, G.T.; Rău, I.; Zgârian, R.G.; Ghica, M.V. Collagen-based biomaterials for ibuprofen delivery. Comptes Rendus. Chimie 2016, 19, 390-394. [CrossRef]

- Voicu, G.; Geanaliu, R.; Ghiţulică, C.; Ficai, A.; Grumezescu, A.; Bleotu, C. Synthesis, characterization and bioevaluation of irinotecan-collagen hybrid materials for biomedical applications as drug delivery systems in tumoral treatments. Open Chemistry 2013, 11, 2134-2143. [CrossRef]

- Constantin Barbaresso, R.; Rău, I.; Gabriela Zgârian, R.; Meghea, A.; Violeta Ghica, M. Niflumic acid-collagen delivery systems used as anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics in dentistry. Comptes Rendus. Chimie 2013, 17, 12-17. [CrossRef]

- Petrisor, G.; Ion, R.M.; Brachais, C.H.; Boni, G.; Plasseraud, L.; Couvercelle, J.P.; Chambin, O. In VitroRelease of Local Anaesthetic and Anti-Inflammatory Drugs from Crosslinked Collagen Based Device. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part A 2012, 49, 699-705. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ronsin, O.; Gravez, B.; Farman, N.; Baumberger, T.; Jaisser, F.; Coradin, T.; Helary, C. Nanostructured Dense Collagen-Polyester Composite Hydrogels as Amphiphilic Platforms for Drug Delivery. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2021, 8, 2004213. [CrossRef]

- Anandhakumar, S.; Krishnamoorthy, G.; Ramkumar, K.M.; Raichur, A.M. Preparation of collagen peptide functionalized chitosan nanoparticles by ionic gelation method: An effective carrier system for encapsulation and release of doxorubicin for cancer drug delivery. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2017, 70, 378-385. [CrossRef]

- Anghel, N.; Dinu, V.M.; Verestiuc, L.; Spiridon, I.A. Transcutaneous Drug Delivery Systems Based on Collagen/Polyurethane Composites Reinforced with Cellulose. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Wufuer, M.; Kim, I.; Choi, T.H.; Kim, B.J.; Jung, H.G.; Jeon, B.; Lee, G.; Jeon, O.H.; Chang, H., et al. Sequential dual-drug delivery of BMP-2 and alendronate from hydroxyapatite-collagen scaffolds for enhanced bone regeneration. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 746. [CrossRef]

- Rathore, P.; Arora, I.; Rastogi, S.; Akhtar, M.; Singh, S.; Samim, M. Collagen Nanoparticle-Mediated Brain Silymarin Delivery: An Approach for Treating Cerebral Ischemia and Reperfusion-Induced Brain Injury. Front Neurosci 2020, 14, 538404. [CrossRef]

- Khiari, Z. Recent Developments in Bio-Ink Formulations Using Marine-Derived Biomaterials for Three-Dimensional (3D) Bioprinting. Mar Drugs 2024, 22. [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, A.; Al Kayal, T.; Mero, A.; Mezzetta, A.; Pisani, A.; Foffa, I.; Vecoli, C.; Buscemi, M.; Guazzelli, L.; Soldani, G., et al. Marine Collagen-Based Bioink for 3D Bioprinting of a Bilayered Skin Model. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.F.; Diogo, G.S.; Pina, S.; Oliveira, J.M.; Silva, T.H.; Reis, R.L. Collagen-based bioinks for hard tissue engineering applications: a comprehensive review. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2019, 30, 32. [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, A.; Etxeberria, A.E.; Naffa, R.; Zidan, G.; Seyfoddin, A. 3D-Printed Hybrid Collagen/GelMA Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering Applications. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Suo, H.; Zhang, J.; Xu, M.; Wang, L. Low-temperature 3D printing of collagen and chitosan composite for tissue engineering. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2021, 123, 111963. [CrossRef]

- Sanz, B.; Albillos Sanchez, A.; Tangey, B.; Gilmore, K.; Yue, Z.; Liu, X.; Wallace, G. Light Cross-Linkable Marine Collagen for Coaxial Printing of a 3D Model of Neuromuscular Junction Formation. Biomedicines 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, X.; Wu, W.; Zhang, A.; Lu, B.; Zhang, T.; Kong, M. Dual cure (thermal/photo) composite hydrogel derived from chitosan/collagen for in situ 3D bioprinting. Int J Biol Macromol 2021, 182, 689-700. [CrossRef]

- Matejkova, J.; Kanokova, D.; Supova, M.; Matejka, R. A New Method for the Production of High-Concentration Collagen Bioinks with Semiautonomic Preparation. Gels 2024, 10. [CrossRef]

- Stepanovska, J.; Otahal, M.; Hanzalek, K.; Supova, M.; Matejka, R. pH Modification of High-Concentrated Collagen Bioinks as a Factor Affecting Cell Viability, Mechanical Properties, and Printability. Gels 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Hudson, A.R.; Shiwarski, D.J.; Tashman, J.W.; Hinton, T.J.; Yerneni, S.; Bliley, J.M.; Campbell, P.G.; Feinberg, A.W. 3D bioprinting of collagen to rebuild components of the human heart. Science 2019, 365, 482-487. [CrossRef]

- Kou, Z.; Li, B.; Aierken, A.; Tan, N.; Li, C.; Han, M.; Jing, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, S.; Peng, S., et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Pretreated with Collagen Promote Skin Wound-Healing. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Ma, D.; Shen, H.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, B.; Fan, Y.; Sun, Z.; Chen, B.; Xue, W.; Shi, Y., et al. Aligned collagen scaffold combination with human spinal cord-derived neural stem cells to improve spinal cord injury repair. Biomater Sci 2020, 8, 5145-5156. [CrossRef]

- Kourgiantaki, A.; Tzeranis, D.S.; Karali, K.; Georgelou, K.; Bampoula, E.; Psilodimitrakopoulos, S.; Yannas, I.V.; Stratakis, E.; Sidiropoulou, K.; Charalampopoulos, I., et al. Neural stem cell delivery via porous collagen scaffolds promotes neuronal differentiation and locomotion recovery in spinal cord injury. NPJ Regen Med 2020, 5, 12. [CrossRef]

- Pietrucha, K.; Zychowicz, M.; Podobinska, M.; Buzanska, L. Functional properties of different collagen scaffolds to create a biomimetic niche for neurally committed human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC). Folia Neuropathol 2017, 55, 110-123. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hu, H.; Wang, J.; Qiu, H.; Gao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Song, L.; Ramshaw, J., et al. Characterization of recombinant humanized collagen type III and its influence on cell behavior and phenotype. Journal of Leather Science and Engineering 2022, 4, 33. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liang, X.; Yu, S.; Zhou, J. Expression, characterization, and application potentiality evaluation of recombinant human-like collagen in Pichia pastoris. Bioresour Bioprocess 2022, 9, 119. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, H.; Yin, H.; Shi, X.; Chen, Y.; Gao, G.; Sun, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y., et al. Status and developmental trends in recombinant collagen preparation technology. Regen Biomater 2024, 11, rbad106. [CrossRef]

- Deng, A.; Yang, Y.; Du, S.; Yang, X.; Pang, S.; Wang, X.; Yang, S. Preparation of a recombinant collagen-peptide (RHC)-conjugated chitosan thermosensitive hydrogel for wound healing. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2021, 119, 111555. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Hou, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; XiaolinYang; Liang, Q.; Zhao, J. Assessment of biological properties of recombinant collagen-hyaluronic acid composite scaffolds. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 149, 1275-1284. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xu, F. [Optimization of unnatural amino acid incorporation in collagen and the cross-linking through thioether bond]. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao 2021, 37, 3231-3241. [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Wei, N.; Xie, Y.; Wang, L.; Yao, L.; Xiao, J. Self-Assembling Triple-Helix Recombinant Collagen Hydrogel Enriched with Tyrosine. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2024, 10, 3268-3279. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yan, H.; Yao, L.; Xie, Y.; Liu, P.; Xiao, J. A highly bioactive THPC-crosslinked recombinant collagen hydrogel implant for aging skin rejuvenation. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 266, 131276. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ritchie, A.C.; Everitt, N.M. Using type III recombinant human collagen to construct a series of highly porous scaffolds for tissue regeneration. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2021, 208, 112139. [CrossRef]

- Kong, B.; Sun, L.; Liu, R.; Chen, Y.; Shang, Y.; Tan, H.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, L. Recombinant human collagen hydrogels with hierarchically ordered microstructures for corneal stroma regeneration. Chem Eng J 2022, 428, 131012. [CrossRef]

- Fushimi, H.; Hiratsuka, T.; Okamura, A.; Ono, Y.; Ogura, I.; Nishimura, I. Recombinant collagen polypeptide as a versatile bone graft biomaterial. Communications Materials 2020, 1, 87. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qiu, H.; Xu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Tan, P.; Zhao, R.; Liu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Bao, C., et al. The biological effect of recombinant humanized collagen on damaged skin induced by UV-photoaging: An in vivo study. Bioact Mater 2022, 11, 154-165. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Rodriguez, G.B.; Montesi, M.; Panseri, S.; Sprio, S.; Tampieri, A.; Sandri, M. (*) Biomineralized Recombinant Collagen-Based Scaffold Mimicking Native Bone Enhances Mesenchymal Stem Cell Interaction and Differentiation. Tissue Eng Part A 2017, 23, 1423-1435. [CrossRef]

- Mostert, D.; Jorba, I.; Groenen, B.G.W.; Passier, R.; Goumans, M.T.H.; van Boxtel, H.A.; Kurniawan, N.A.; Bouten, C.V.C.; Klouda, L. Methacrylated human recombinant collagen peptide as a hydrogel for manipulating and monitoring stiffness-related cardiac cell behavior. iScience 2023, 26, 106423. [CrossRef]

- Tytgat, L.; Dobos, A.; Markovic, M.; Van Damme, L.; Van Hoorick, J.; Bray, F.; Thienpont, H.; Ottevaere, H.; Dubruel, P.; Ovsianikov, A., et al. High-Resolution 3D Bioprinting of Photo-Cross-linkable Recombinant Collagen to Serve Tissue Engineering Applications. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 3997-4007. [CrossRef]

- Gibney, R.; Patterson, J.; Ferraris, E. High-Resolution Bioprinting of Recombinant Human Collagen Type III. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Xia, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, S.; Jin, M. Preparation of Chitosan/Recombinant Human Collagen-Based Photo-Responsive Bioinks for 3D Bioprinting. Gels 2022, 8. [CrossRef]

| Material form | Collagen source | Additives | Cross-linking | In vivo test | In vitro test | Application | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scaffold | Fish collagen | Chondroitin sulfate, hydroxyapatite | Yes | Yes | Yes | Osteochondral regeneration | After 6 weeks, the scaffold-treated defects were well-filled with smooth, integrated tissue, unlike the empty group with irregular surfaces. By 12 weeks, the scaffold group showed complete filling with cartilage-like tissue and superior integration compared to the empty group. | [80] |

| Scaffold | Human-like collagen | Nano-hydroxyapatite | Yes | Yes | Yes | Bone regeneration | 12 weeks after implantation, one of the tested scaffolds degraded completely and visibly repaired the bone defect | [81] |

| Scaffold | NA | PLGA, antibacterial synthetic peptides | Yes | No | Yes | Bone regeneration | Obtaining collagen-based scaffolds with osteogenic activity and sustained release of antibacterial peptides creates an environment that promotes cell differentiation and inhibits bacteria | [82] |

| Scaffold | Fish scale collagen (tilapia) | Chitosan | Yes | No | Yes | Oral mucosa therapeutic device | Oral keratinocytes from human oral mucosa produced a multi-layered, polarized, stratified epithelial layer | [83] |

| Scaffold | Fish collagen (flatfish) | Chitooligosaccharides, carbodiimide derivative | Yes | No | Yes | Skintissue regeneration | Induced cell adhesion and proliferation, promotion of well-spread cell morphology | [84] |

| Scaffold | Calf skin | Hydroxyapatite, CaO fibers | Yes | Yes | Yes | Bone regeneration | 8 weeks after implantation, the condylar bone defect was wholly regenerated, and the scaffold had been completely absorbed | [85] |

| Scaffold | Jellyfish | - | Yes | Yes | Yes | Nasa cartilage repair | Excellent biocompatibility with only slight evidence of local inflammatory reactions; prevention of septal perforations | [86] |

| Scaffold | N/A | Chondrocytes | N/A | Yes | No | Matrix associated autologous | Partial or complete filling of the lesion in knee joint cartilage | [87] |

| Scaffold | Equine | - | Yes | Yes | No | Cartilage repair | Integration into the host articular cartilage and promotion of the new cartilage-like tissue development by recruiting the host cells and driving them towards the chondrogenic differentiation, total biodegradation, and replacement of the biomaterial with the newly formed cartilage-like tissue at 16 weeks post-implantation | [88] |

| Scaffold | Type I collagen (corning) | Concentrated growth factor | No | Yes | Yes | Periodontal defects healing | 8 weeks after implantation, the scaffold reconstructed a complete and functional periodontium with the insertion of periodontal ligament fibers into newly formed cementum and alveolar bone | [89] |

| Membrane | Porcine Peritonea | Zinc-doped nanohydroxyapatite | Yes | Yes | Yes | Guided bone regeneration | Obtaining a membrane that preserves the triple-helical structure of collagen fibers and their native 3D network and has a satisfactory biodegradation rate | [90] |

| Membranes | Porcine (Bio-Gide®), Bovine (Colla-D®) | 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide | Yes | Yes | Yes | Guided bone regeneration | Membranes integrated well with surrounding tissues and achieved good osseointegration, without cytotoxic effect, with no membrane exposure observed and no complications | [91] |

| Membrane | Type I porcine collagen (CelGro™) | - | No | Yes | No | Cortical bone regeneration | CelGro™ significantly improved cortical bone repair in the preclinical animal study; in dental implant placement, GBR with CelGro™ resulted in successful regeneration of sufficient mature bone to stabilize the dental implants and process to crown placement | [92] |

| Patches | Scales of snakehead (Channa Micropeltes) | 1,4-butanediol diglycidyl ether | Yes | Yes | Yes | Subcutaneous implantation in mice | Improved cell attachment, proliferation, an infiltration favorable growth of blood and lymphatic vessels | [93] |

| Collagen matrix | Porcine skin | - | No | Yes | Yes | Wound healing | The collagen matrix supports the migration of cells through the matrix, accelerating the healing process | [94] |

| Collagen matrix | Type I bovine | - | Yes | Yes | No | Nerve defect regeneration | Significant improvement of the nerve gap bridging and functional motor recovery in a rat model | [95] |

| Gel | Fish collagen | Genipin | Yes | No | Yes | Biomaterial | Obtained collagen gels exhibit high thermal stability, antioxidant capacity, and characteristic FTIR peaks of type I collagen, indicating their potential for biomaterial applications | [96] |

| Gel | Fish skin (tilapia) – collagen peptides applied in a gel form | - | No | Yes | Yes | Oral ulcer healing on dorsum tongue of mice | Healing promotion: decreased inflammatory cell infiltration, reduced TNF-αand IL-1β expression, increased fibroplasia, angiogenesis, and collagenesis trend | [97] |

| Hydrogel | Type I rat tail collagen | Alginate, CaSO4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cells / biomolecules delivery in surgeries | A simple method for creating pre-crosslinked injectable collagen-based hydrogels was developed, and significant results of cell viability compared to similar hydrogels were achieved | [98] |

| Hydrogel | Bovine | Polyethylene glycol | Yes | Yes | Yes | Corneal defects repairment | PEG-collagen hydrogels were able to fill the defect area, remained transparent over one week, and supported multi-layered epithelial growth | [99] |

| Hydrogel | Porcine | - | Yes | Yes | Yes | Corneal implantation | Positive replacement of the portion of a native corneal stroma with rapid wound healing in vivo, the implant permitted host stroma cell migration, epithelial and nerve regeneration while maintaining corneal shape and thickness during a 6-month postoperative period | [100] |

| Hydrogel | Porcine skin | Chondroitin sulfate, poly-d-lysine | Yes | Yes | Yes | Wound healing | Induced fast and superior skin regeneration in a non-healing wound model in diabetic mice | [101] |

| Hydrogel | Fish skin (Nile tilapia) | - | No | Yes | Yes | Healing of deep second-degree burns on rat skin | Significant acceleration of healing of deep second-degree burn wounds | [102] |

| Hydrogel | Swim bladder of Bester sturgeon fish – Type I atelocollagen | Hydroxyapatite, poly(N,N’-dimethylacrylamide) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Implantation into the osteochondral defect | 4 weeks after implantation, the collagen-based gel did not degrade and maintained high strength, indicating its strong osteointegration ability | [103] |

| Gel | Type I Bovine telocollagen | Riboflavin | Yes | No | Yes | Sealant for Corneal Perforation | A highly transparent gel with high adhesion between endo and exogenous collagen was obtained | [104] |

| Hydrogel | Type I Porcine | DL-N-acetylhomocysteine thiolactone | Yes | No | Yes | Sealant for Corneal Perforation | Fully transparent enzyme degradable hydrogel was obtained, and the manufacturing method allows for tuning of the mechanical properties of the gel | [105] |

| Hydrogel | Type I porcine dermal collagen | Dexamethasone, 1-[3-(Dimethylamino) propyl] −3-ethylcarbodiimide me- thiodide, N-hydroxysuccinimide, riboflavin | Yes | Yes | Yes | Corneal application | A transparent hydrogel composed of collagen reinforced by nanocellulose fibers and strengthened through chemical and photochemical crosslinking. Sustainable biomaterial, offering abundance, renewability, and biocompatibility, was obtained, which can be loaded with dexamethasone to reduce inflammation for at least two months post-implantation effectively | [106] |

| Film | Fish collagen (silver carp) | Salicin | Yes | No | Biomaterial application, cosmetics | Addition of salicin increases the viscosity of the solution (intermediate product) and improves the mechanical properties of collagen films | [107] | |

| Film | Porcine, bovine, equine | Carboxymethylcellulose, glycerine, macrogol 300 | No | No | Wound treatment | Films made of equine collagen showed the highest mechanical strength and the lowest swelling ratio compared to the porcine and bovine collagen | [108] | |

| Film | Type 1 marine collagen | Nanoparticles Iron Oxide, Nanoparticles Graphene oxide | No | No | Medicine, Food packaging | Adding iron oxide and graphene oxide improves collagen films' antioxidant, antibacterial and mechanical properties. | [109] | |

| Sponge | Fish collagen, Bovine, Rat tail | No additives | No | Yes | Yes | Wound healing material | The porosity and structure of tilapia skin sponge can be tuned by changing the final concentration. The obtained material can induce blood vessel ingrowth in the wound | [110] |

| Sponge | Rat tail | Taurine | No | Yes | Yes | Wound healing material | The fastest growth of epidermis increased level of TGF- and VEGF protein secretion was observed for collagen sponges with taurine compared to collagen alone and the control sample | [111] |

| Sponge | Type I bovine | Polydopamine, platelet rich plasma | Yes | Yes | Yes | Full thickness skin defect healing | Collagen sponge with polydopamine and PRP showed the highest cell adhesion and proliferation and the fastest wound healing compared to materials without polydopamine | [112] |

| Sponge | Fish collagen (tilapia); bovine collagen | Polyethylene oxide, chitosan | - | Yes | No | Evaluation of wound healing in rats | Increasing the percentage of wound contraction, reducing the inflammatory infiltration, and accelerating the epithelization and healing also enhanced the total protein and hydroxyproline levels in the wound bed | [113] |

| Microcapsule | Type I rat tail | Osteoarthritis chondrocytes | Yes | No | Yes | Osteoarthritis | UV-treated collagen pre-gels form hollow tubes with high stability, adjustable viscoelasticity, and controlled pore structure, ideal for separate endothelial and ectodermal cell cultures | [114] |

| Collagen tube | Type I | Riboflavin | Yes | No | Yes | Vascular networks and nerve fibers in artificial organ fabrication and regenerative medicine | A method for producing collagen gel tubes for potential biomedical applications has been developed |

[115] |

| Tube / rod | Type I porcine atelocollagen | Carbonate buffer | Yes | No | Yes | Regenrative medicine | A collagen-based material with excellent mechanical properties, biocompatibility, and patentability has been developed | [116] |

| Powder | Fish skin (Nile tilapia) collagen polypeptides | - | No | Yes | Yes | Evaluation of wound healing activity | High capacity to induce HaCaT cell migration; healing improvement in the deep partial-thickness scald model in rabbits | [117] |

| Product / Manufacturer | Collagen type | Additive | Material type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-Gide® / Geistlich Pharma | Type I, III | - | Membrane |

| Jason® / Botiss | Type III | - | Membrane |

| OssixPlus® / Datum Dental Ltd. | Type I | - | Membrane |

| Biomend® Zimmer | Type I | - | Membrane |

| Collagraft® / Zimmer | Type I >95%, Type II <5% | HAP 1 - 65% β-TCP 2 - 35% |

Scaffold |

| GingivAid®/ Maxigen Biotech Inc. | Type I | HAP, β-TCP | Scaffold |

| Integra Mozaik / Integra Life Sciences | Type I | TCP 3 | Scaffold |

| FormaGraft / Maxigen Biotech Inc. | Type I | HAP, TCP | Scaffold |

| Orthoss Collagen / Geistlich | N/A | Bovine HAP | Scaffold |

| OP-1 Implant / Stryker | Type I | BMP-7 4 | Scaffold |

| SilvaKollagen®Gel/ DermaRite®, | Type I | 1% silver oxide | Gel |

| WounDres® / Coloplast | N/A | Panthenol, alantoine | Gel |

| RatuZel / Regional Health Center Ltd. | Type I | Lactic acid | Gel |

| Parasorb® / Resorba | N/A | - | Sponge |

| Hemocollagene / Septodont | Type I | - | Sponge |

| Surgispon® / AegisLifeSciences | N/A | - | Sponge |

| Collagen origin and the type of drug delivery system |

Drug (and its activity) |

Route of administration | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bovine type I collagen cross-linked by glutaraldehyde, hybrid lyophilizates | irinotecan (topoisomerase I inhibitor) | transdermal | treatment of bone and skin cancer | [158] |

| bovine type I collagen cross-linked by glutaraldehyde, lyophilized sponges | niflumic acid (an analgesic and anti-inflammatory agent) | local - teeth | pain management in dentistry and medicine |

[159] |

| type I collagen from calf skin, cross-linked by glutaraldehyde | lidocaine hydrochloride (local anesthetic), diclofenac sodium salt (anti-inflammatory), caffeic acid (anti-inflammatory, antioxidant) |

dermal | potential dermal application for anesthetic or anti-inflammatory action | [160] |

| amphiphilic composite platform associating dense collagen hydrogels and up to 50 wt% polyesters |

spironolactone (an antagonist against mineralocorticoid receptor) | not specified | potential application in cardiovascular and renal diseases, cutaneous chronic wounds, age-related macular degeneration, chorioretinal disorders |

[161] |

| collagen peptide and chitosan nanoparticles (pH-responsive) | doxorubicin hydrochloride (antineoplastic activity) | not specified | significant anti-proliferative properties against HeLa (human cervical carcinoma) cells, potential innovative drug delivery carriers in advanced cancer therapy | [162] |

| biomaterials made from cellulose, collagen, and polyurethane formed into thin films | ketoconazole (antifungal agent) | transcutaneous | controlled drug release and biocidal activity | [163] |

| collagen (rat tail-derived) type I -hydroxyapatite scaffolds functionalized using BMP-2 and loaded with biodegradable microspheres with ALN encapsulated |

bone morphogenic protein-2 (BMP-2; osteoinductive growth factor) and alendronate (ALN; treatment of bone loss and osteoporosis) | bone implantation | the initial release of BMP-2 for a few days, followed by the sequential release of ALN, after two weeks, provides enhanced bone regeneration |

[164] |

| ovine collagen-based micellar nanoparticles (3-ethyl carbodiimide-hydrochloride and malondialdehyde as crosslinkers) |

silymarin (neuroprotective activity) | intraperitoneal | enhanced neuroprotection by increasing drug bioavailability and targeting (in rats) | [165] |

| PerioChip – gelatin insert | chlorhexidine digluconate (antibacterial) | periodontal pockets | enhanced reduction of pocket depth by approx. 0.4 mm within 6 months | [156] |

| bovine collagen sponge (cross-linked with glutaraldehyde) | ibuprofen (anti-inflammatory, analgesic) | dental | dental problems | [157] |

| collagen (from the marine sponge Chondrosia reniformis) nanoparticles | 17β-estradiol-hemihydrate (hormone replacement therapy) | transdermal | prolonged release and enhanced absorption of estradiol through human skin | [152] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).