1. Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCCs) still rank among the most common tobacco and alcohol associated malignancies in men and women worldwide [

1]. The 5-year survival rates have only modestly improved over the last decade, and remain around 50%. In addition, recurrence of the disease following treatment is observed in about 50% of patients with high rates of associated mortality. In Canada, more than 4,300 people will develop cancer of the head and neck this year; over 1,600 of them will die from this disease [

2].

In HNSCC, promoter methylation of tumor suppressor genes appears to be a common mechanism of transcriptional silencing [

3]. The identification of novel genes specifically affected by DNA methylation represents a way forward to the identification of genes with relevance as potential clinical biomarkers, and in identifying potential new tumor suppressor genes and understanding their mechanisms of action. Our group and others have previously completed genome-wide scans of aberrant DNA methylation in DNA samples from HNSCC primary tumors [

4,

5,

6]. Our previous study identified a cluster of epigenetically-silenced Krüppel-type zinc finger protein (ZNF) genes located on chromosome 19q13 in all anatomic sub-sites of HNSCC [

5]. One of these was ZNF671, a novel Krüppel-type zinc finger protein that is epigenetically-silenced with high frequency in HNSCC cases.

Here, we examine the expression of ZNF671 and its aberrant promoter DNA methylation in an independent patient cohort of the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). We examine the effects of overexpression of ZNF671 in HNSCC cell line UM-SCC-1. And finally, we shed some light on long non-coding RNA LINC00665 as a novel target for ZNF671, and its subsequent effect on multiple cancer-related signalling pathways.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analysis of Global Gene Expression and DNA Methylation Data from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Einstein/Montefiore Patient Cohorts

Global gene expression, DNA methylation, clinical characteristics, and overall survival data, current as of December 2020, for 516 primary HNSCC patients was downloaded from TCGA database [

7]. These represented data from three major anatomic site: oral cavity (alveolar ridge, buccal mucosa, floor of mouth, hard palate, and oral tongue), oropharynx (base of tongue, uvula, soft palate, and tonsil), and larynx (hypopharynx, and larynx). DNA methylation data were measured using the using the Illumina HumanMethylation450k beadchip. Beta-values were converted to M-values using the log transformation as described previously [

8]. For downstream analysis, the M-value was more statistically valid for the differential analysis of methylation levels [

8]. Gene expression was represented as normalized gene counts from RNA seq data. Overall survival was measured as the time in days between the date of surgery, and the date of death or the last follow-up. Einstein cohort clinical data and ZNF671 expression data, measured using the Illumina HT-12 DirectHyb expression beadchip were downloaded from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Head and Neck Cancer Database [

9]. In this cohort, survival is represented as death of disease.

Summary gene expression and DNA methylation data for ZNF671 is presented as Mean ± SD. Measurements of gene expression and DNA methylation profiles were represented as continuous variables, whereas clinical data are represented as categorical variables. Comparisons between HNSCC primary tumor and adjacent non-tumor tissue samples were performed using paired t-test, and graphed using the

boxplot function R (version 4.3.1). Overall survival curves for the TCGA patient cohort were assessed using Kaplan-Meier analysis and the log-rank test to assess differences between curves following patient stratification based on median ZNF671 tumor expression. All analysis was completed using the

survival package 3.4-0 in R and plotted using

survminer 0.5.2 [

10]. In all cases, a threshold p-value of p<0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

2.2. Lentiviral Transduction of HNSCC Cell Lines

Overexpression of ZNF671 protein in oral squamous cell carcinoma cell line UM-SCC-1 was carried out by lentiviral transduction as described previously, and according to the recommendations of the manufacturer [

11]. Stable constitutive overexpression of ZNF671 in UM-SCC-1 cells was carried out using the pLenti-C-Myc-DDK-P2A-Puro construct vector expressing the Flag-tagged ZNF671 fusion protein under the control of the CMV promoter (Origene Cat#RC206413L3), followed by selection of transduced clones using 0.25-0.50 mg/mL of puromycin. As in previous experiments, the empty pLenti-C-Myc-DDK-P2A-Puro vector was used as a negative control (Origene Cat# PS100092). Isolation of total RNA from cells was carried out by the RNeasy total RNA kit (Cat# 74104, Qiagen). Expression of ZNF671 transcript was confirmed by Taqman real-time PCR (ZNF671: Hs01087685_m1) using the protocol as described by the manufacturer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.3. Measurement of ZNF671 Protein Expression

Levels of ZNF671 fusion protein in transduced cells were confirmed as described previously for ZNF proteins [

11]. Briefly, cells were washed with cold phosphate buffered saline and lysed in 200µl RIPA buffer (50mM Tris pH7.4, 137mM NaCl, 2.7mM KCl, 11.9mM phosphates, 1% TritonX, 5mM EDTA, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 0.1% SDS, 50mM β-glycerophosphate, 50mM sodium fluoride, 1mM PMSF, 2mM sodium orthovanate, 10µg/ml Aprotinin, 10µg/ml Leupeptin and 10µg/ml Pepstatin). Lysates were disrupted by passing through a 25-gauge needle and by sonication on ice. Protein extracts were then centrifuged at 11,000xg for 15 minutes at 4°C to remove cell debris. All protein concentrations were subsequently determined using the Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Cat# 2322S, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

For Western blot analysis, total cellular protein (40µg) was resolved on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Cat# 1620115, BioRad). Membranes were probed using a Flag primary antibody (1:2000) (Cat# TA50011, Origene) and secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse HRP (1:5000) (Cat# 115-035-071, Jackson Immunoresearch). Detection of HRP was carried out using Amersham ECL Select Western Blotting Detection Reagent (RPN2235) and imaged on a Biorad Chemidoc MP Imaging System. All images were analyzed using Bio-rad Laboratories Image Lab software (version 6.1). As a loading control, all membranes were re-probed for β-actin (1:2000) (Cat# MABT523, Millipore Sigma) in the presence of 0.05% sodium azide; secondary antibody was goat anti-rabbit HRP (1:10000) (Cat# 65-6120, Invitrogen). HRP signal was detected using SuperSignal West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate (Cat# 34579, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.4. Measurement of Tumor Cell Growth, Migration and Invasion

Measurements of cells counts were obtained every 48 hours using a haemocytometer and phase contrast microscope; cell viability was confirmed by Trypan Blue exclusion. All tumor cell numbers were expressed as mean ± SD in triplicate measrurements. Differences between any two independent groups were assessed by single factor ANOVA using Microsoft Excel 2013. Migration of UM-SCC-1 cells was measured using the Radius 96-well cell migration assay according to the recommendations of the manufacturer (Cat# CBA-126, Cell Biolabs). Images of cell migration were captured at 0 and 48 hours post gel removal. Cell free area was measured using Adobe Photoshop (version 23.2.2.325).

Tumor cell invasion assays were performed using BioCoat Matrigel Invasion Chambers (Cat# 08-774-122, Fischer Scientific) as described previously [

12]. Briefly, invasion chambers were first hydrated with complete media for 2 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cells were harvested with Accutase and approximately 1.0x105 cells were suspended in 0.5ml serum free media (0.7% BSA) and added to the top well of the invasion chamber with the bottom well containing 0.1nM mouse EGF (Cat # SRP3196, Sigma Aldrich) diluted in serum free media (0.7% BSA). Chambers were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cells were then fixed with formalin for 15 minutes and stained with Crystal Violet staining solution (0.2% crystal violet, 2% ethanol in dH2O) for 10 minutes. Non-invading cells were removed from the membrane with a moistened cotton swab. Membranes were cut from the chamber, mounted on a microscope slide and imaged with a flatbed scanner. The area of the membrane covered with invading cells was quantified using ImageJ software.

2.5. Whole Transcriptomic Analysis of Gene Expression

Whole transcriptome analysis of gene expression differences in ZNF671 overexpressing UM-SCC-1 cells was carried out by RNA sequencing on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 S4 PE100 (Genome Quebec) as paired 100 bp reads. Resulting reads were assessed for quality using FastQC (version 0.11.9) [

13]. The resulting fastq read files were aligned to the Human hg38 reference genome using RNA-Star aligner (Galaxy Version 2.7.8a) with default settings. Transcripts for a given gene were counted using

featureCounts (Galaxy version 2.0.1) [

14,

15]. Identification of differentially expressed genes when comparing ZNF671 overexpressing and empty vector control UM-SCC-1 cells was carried out using the negative binomial distribution with

DeSeq2 (Galaxy Version 2.11.40.7), with a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value of less than 0.05 [

16].

Identification of overrepresented groups of genes was carried out using

GOseq (Galaxy Version 1.44.0) [

17].

GOseq was used for gene set enrichmernt analysis with RNA seq data as it could account for gene length bias in the detection of over-represented genes ([

17]).

GOseq was used to calculate a probability weighting function (PWF) which gave us the probability that a gene would be differentially expressed (DE) based on its length alone. This function was then used to weight the chance of selecting each gene when forming a null distribution for gene ontology (GO) category membership. Random sampling was then utilized in order to generate a null distribution for GO category membership, and to calculate each category’s significance for over representation amongst the differentially expressed genes. Gene ontology categories tested included Molecular Function (GO:MF), Cellular Component (GO:CC), and Biological Process (GO:BP). Wallenius non-central hypergeometric distribution was used to assess the distributions of the numbers of members of a given category amongst the differentially expressed genes [

17]. P-values for over representation of a given GO term among the differentially expressed genes were adjusted for multiple testing using Benjamini-Hochberg correction [

18].

2.6. Knockdown of ZNF671 Gene Expression by siRNA Transient Transfection in Human Epithelial Keratinocytes

Human epithelial keratinocytes (Hekn) were purchased from ATCC (PCS-200-010) and maintained at 37°C, 5%CO2. Cells were cultured in Dermal Cell Basal Medium (ATCC PCS-200-030) supplemented with Keratinocyte Growth Kit (ATCC PCS-200-040). Knockdown of ZNF671 gene expression by siRNA was carried out essentially as described previously [

19]. Keratinocytes were plated at a density of 5x10

4 cells in antibiotic-free complete medium for 24 hours before siRNA transfection. At the time of transfection, culture medium was replaced with fresh antibiotic-free complete medium containing siGENOME oligos at a final concentration of 50 nmol/L with 1 mL of Dharmafect Reagent 1 (Cat. T-2004-02; GE Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO). siRNA oligos used were as follows: siGENOME siZNF671: Cat. D-014473, Target sequences: 5’-GGACAGAGGUAUCACAGGU-3’, 5’-GGAGAGAAUUCAUCCGGAA-3’, 5’-CCUUACACCUGGCUAAAUA-3’, 5’-GAUUAUGAGUGUAGCAGAU-3’. Accell Green Non-targeting siRNA: Cat. D-001950, Target sequence: 5’-UGGUUUACAUGUCGACUAA-3’. Cells were then incubated for 48 hours without changing medium. Knockdown of ZNF671 gene expression was confirmed by Taqman real-time PCR using the protocol as described by the manufacturer (ThermoFisher Scientific).

3. Results

3.1. Epigenetic Silencing of ZNF671 in HNSCC Primary Tumors Has Prognostic Relevance for This Disease

The ZNF671 gene, located on chromosome 19q13, codes for a protein of 534 amino acids (61kDa). The protein is categorized as a KRAB-ZNF protein containing ten C2H2 zinc finger domains as well as an N-terminal KRAB domain. Our first objective was to validate our previously reported findings that ZNF671 was epigenetically silenced in HNSCC [

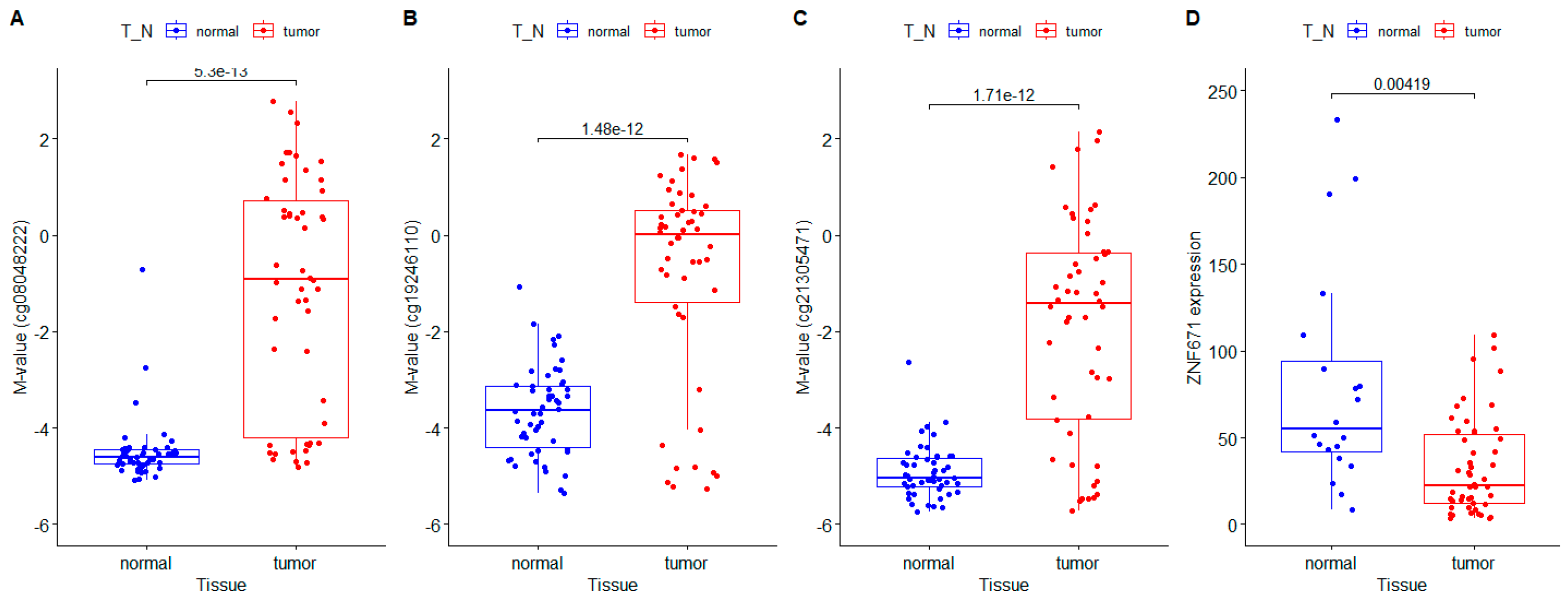

5]. tumorWe first compared measurements of DNA methylation, expressed as M-values, between primary tumor and matched adjacent non-tumor tissue for 50 HNSCC patients from the TCGA. These measurements of DNA methylation (M-values) for all three CpG loci located within the ZNF671 promoter showed significantly increased DNA methylation in the primary tumor DNA compared with matching non-tumor tissue DNA from the same patient (cg08048222: -1.17±2.43 (tumor) versus -4.49±0.66 (non-tumor) p<0.001, cg19246110: -0.80±2.12 (tumor) versus -3.65±0.92 (non-tumor) p<0.001), and cg21305471: -1.92±2.27 (tumor) versus -4.91±0.55 (non-tumor) p<0.001) (

Figure 1A-C). Next we compared ZNF671 RNA transcript levels between between primary tumor and matched adjacent non-tumor tissue for 30 of the same HNSCC patients using RNA sequencing data obtained from the TCGA. This data confirmed that ZNF671 expression was significantly downregulated in HNSCC tumors compared with matching non-tumor tissue from the same patient (

Figure 1D,p<0.05). Taken together, the results confirm our initial findings of epigenetic downregulation of ZNF671 in a separate cohort of HNSCC patients.

Not all HNSCC tumors showed epigenetic silencing of ZNF671 expression. We therefore tested whether ZNF671 expression might have a negative correlation with promoter DNA methylation, and whether expression might have prognostic significance in this disease. Utilizing the cohort of TCGA HNSCC patients, a scatter plot of DNA methylation versus gene expression for ZNF671 showed a significant negative correlation

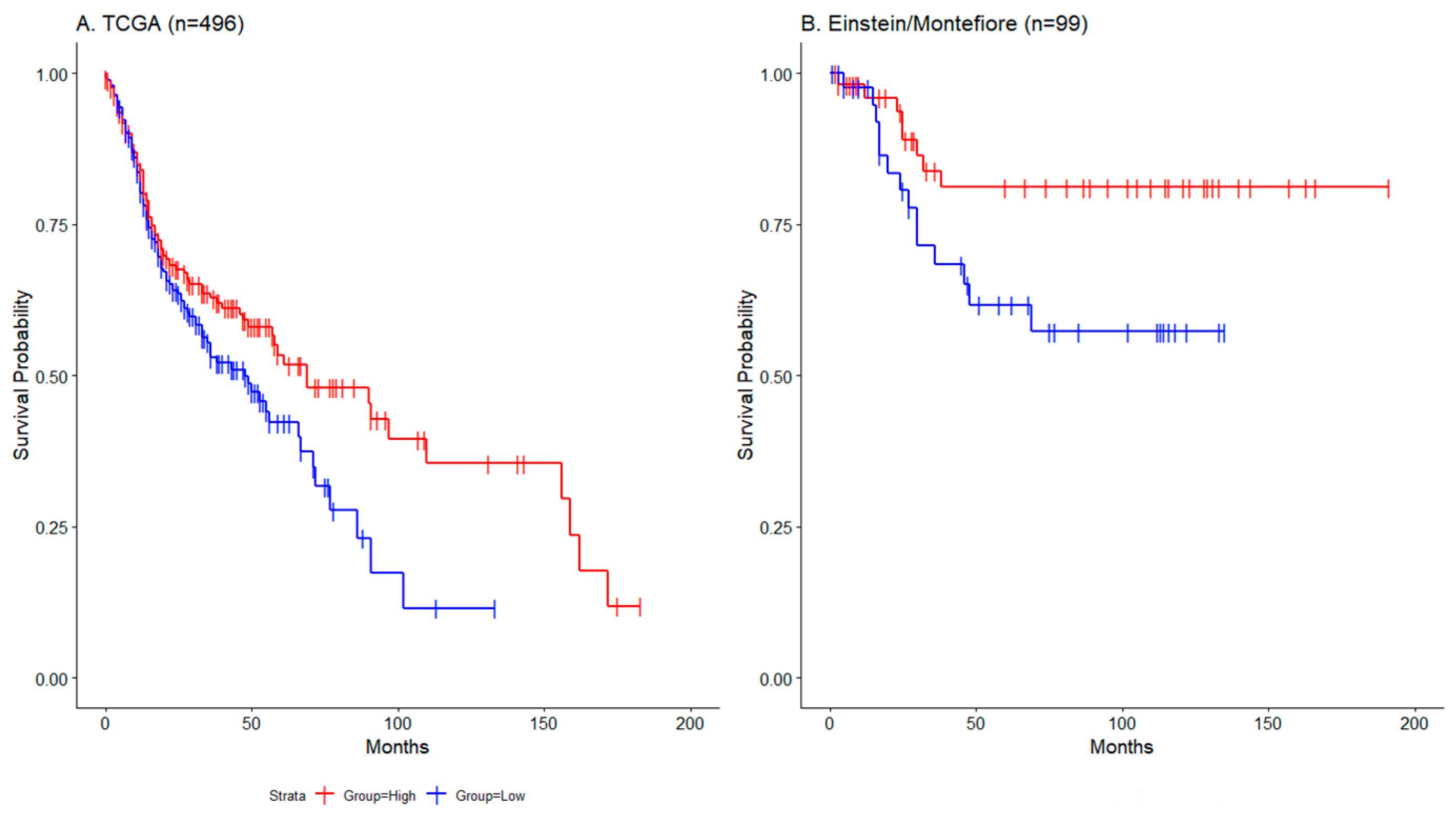

(Spearman correlation -0.58; Pearson correlation -0.52; Supplementary Figure S1). Moreover, survival analysis stratifying patients based on the median ZNF671 tumor expression demonstrated that patients whose primary tumors had low ZNF671 expression (less than the median expression) showed a significantly worse overall survival when compared to those with higher ZNF671 expression

(Figure 2A, Log-rank, p<0.05). This association was also validated in a separate cohort of 99 HNSCC patient data obtained from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Head and Neck Cancer Database. In that cohort, patients whose primary tumors had low ZNF671 expression (less than the median expression) also showed a significantly worse disease-specific survival when compared to those with higher ZNF671 expression (

Figure 2B, Log-rank, p<0.05). Together, these observations support both an epigenetic mechanism for ZNF671 expression, and a prognostic role for ZNF671 expression as a possible biomarker in head and neck malignancies.

3.2. Over-Expression of ZNF671 Decreased Tumor Cell Mobility and Invasion

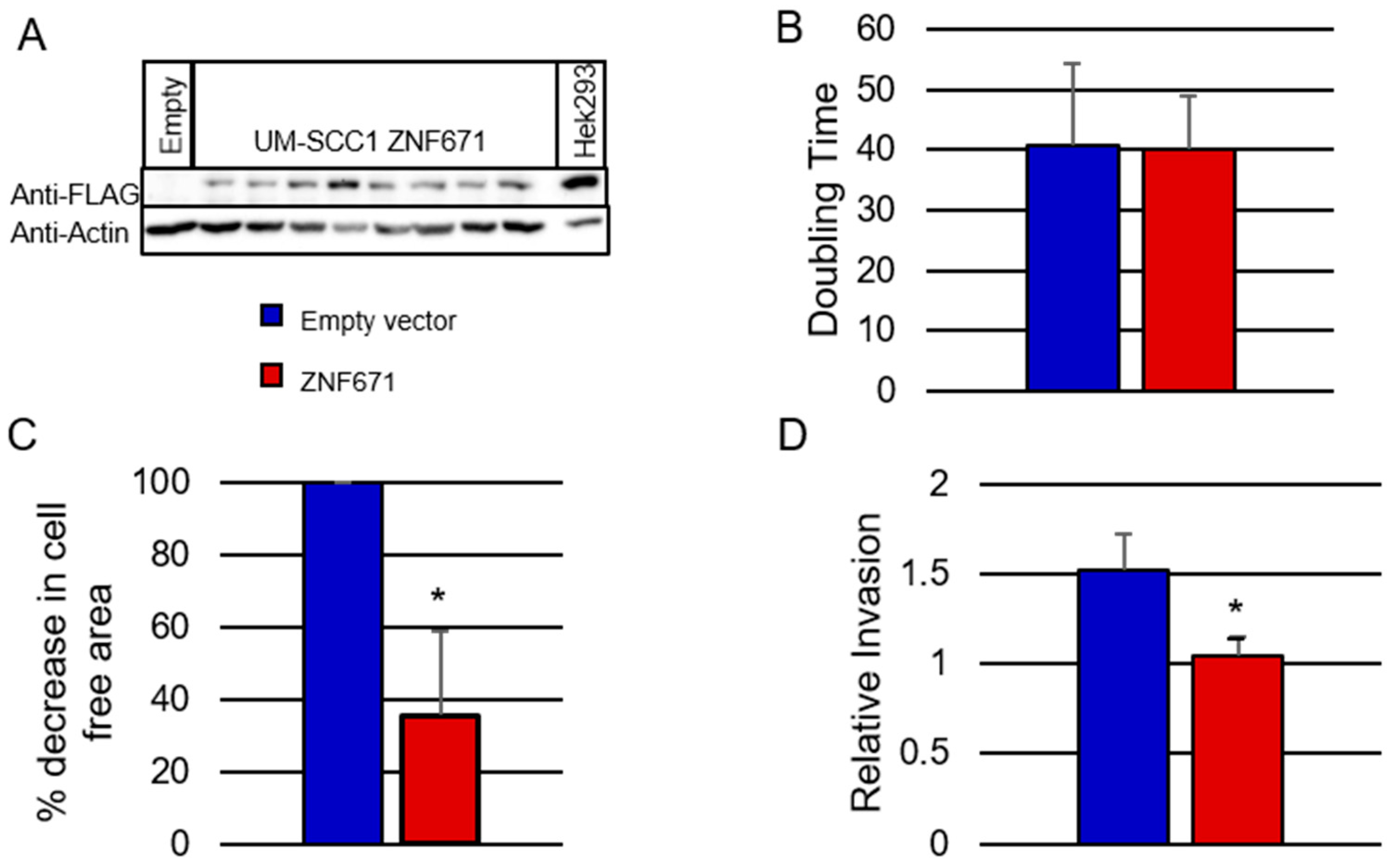

In order to investigate potential tumor suppressive properties of ZNF671 in HNSCC cells, we overexpressed ZNF671 in the oral cancer cell line UM-SCC-1 by lentiviral transduction of a C-terminal Flag-tagged fusion protein construct under the control of a CMV promoter. We initially confirmed overexpression of the Flag-tagged ZNF671 fusion-construct by both real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) and at the protein level by Western blot. As shown in

Figure 3A, Western blot analysis showed an over-expression of Flag-tagged ZNF671 protein in eight UM-SCC-1 clones, with a molecular weight of 61kDa (lanes 2 through 9). This protein was absent from the empty vector control cells (lane 1). Similarly, quantitation of ZNF671 RNA transcripts by Taqman quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) revealed a significant increase in transcript abundance in the ZNF671 overexpressing cells compared to the empty vector controls (data not shown). To date, attempts to overexpress ZNF671 in HNSCC cell lines SCC-15 and SCC-25 have been unsuccessful, or have resulted in the production of truncated proteins due to an unknown mechanism.

UM-SCC-1 oral cancer SCC cells overexpressing were tested for changes in tumor cell phenotype. First, growth of UM-SCC-1 cells expressing the ZNF671 protein did not result in any significant increase in UM-SCC-1 doubling time (40.3 hours) when compared to the empty vector control cells (40.7 hours) (

Figure 3B). However, migration of UM-SCC-1 cells, measured using the Radius 96-well cell migration assay, showed that expression of ZNF671 resulted in a significant decrease in tumor cell migration when compared to the empty vector control cells (

Figure 3C). At 48 hours, UM-SCC-1 cells overexpressing ZNF671 showed only a 36% decrease in cell-free area, compared with 100% for the empty vector control cells. Representative images of the cell migration assay are shown in

Supplementary Figure S2. Similarly, overexpression of ZNF671 resulted in a significant decrease in tumor cell invasion compared to the empty vector control cells as measured by transwell invasion assay (

Figure 3D). From these results, we concluded that when expressed in UM-SCC-1 cells, ZNF671 had a significant effect on both mobility and invasion, and may likely affect the expression of target genes involved in these processes.

3.3. Transcriptomic Analysis of ZNF671 Re-Expression Revealed Alterations in Multiple Cancer-Related Signalling Pathways via a Significant Decrease in Oncogenic LINC00665

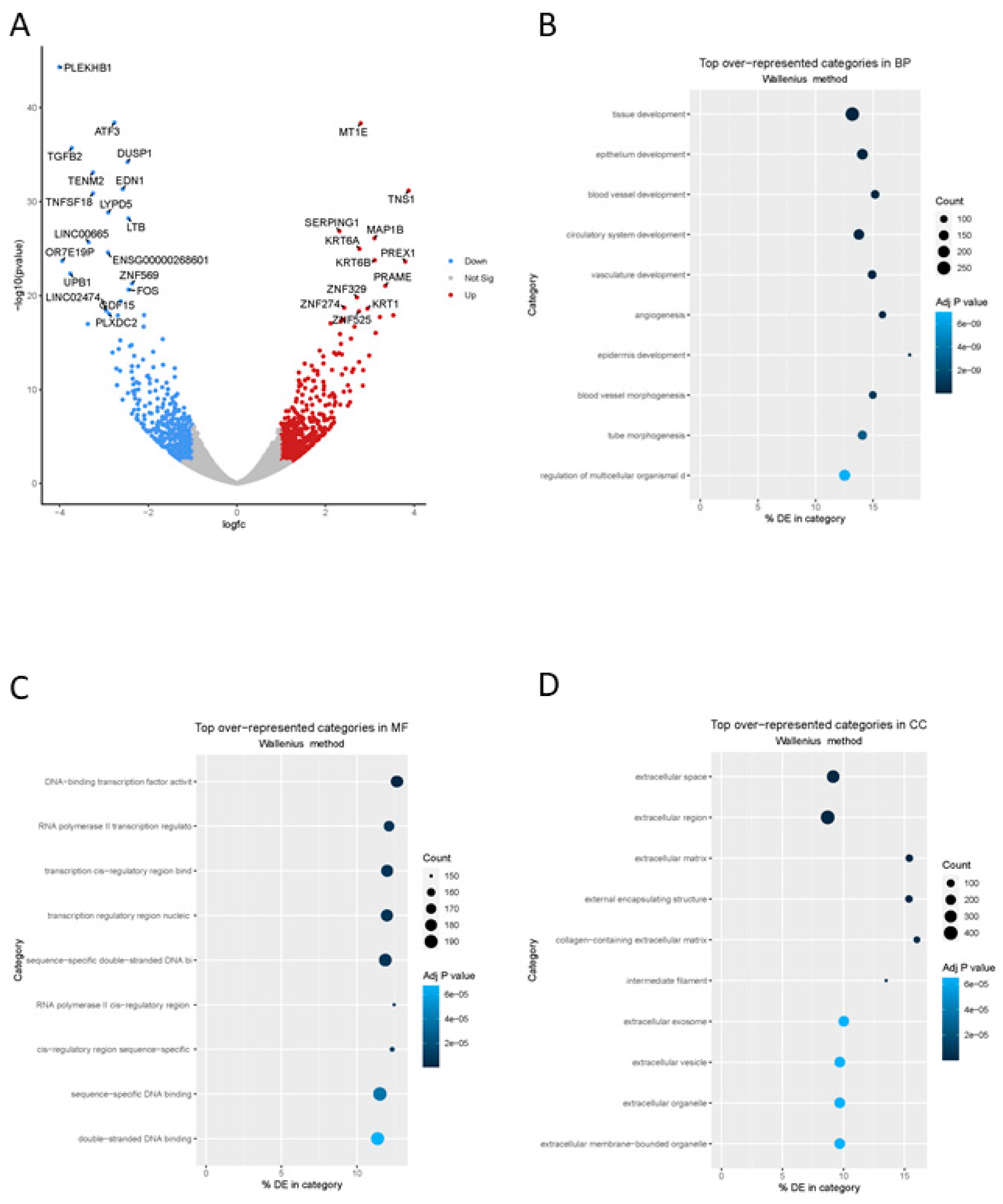

In order to get a global view of gene expression changes in response to ZNF671 overexpression, we compared transcriptomic profiles of UM-SCC-1 cells overexpressing ZNF671 to those of empty vector control cells using RNA-sequencing technology. Analysis of transcriptomic data using DESeq2 revealed a total of 1,729 differentially expressed genes with an adjusted p-value of less than 0.05

(Supplementary Table S1). Limiting the genes to those with a log fold change (log

2FC) of at least 1 (or -1) resulted in 981 differentially expressed genes (540 up-regulated, 441 down-regulated) in response to ZNF671 overexpression (

Figure 4A). Most genes identified in both lists of differentially expressed genes were located on chromosome 19, suggesting a role for ZNF671 in the expression of other ZNF proteins.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) using gene ontology (GO) terms related to biological processes (BP), molecular function (MF), and cellular component (CC) was utilized to group differentially expressed genes along common biological themes

(Supplementary Table S2). Most GO:BP categories included those related to genes involved in developmental processes such as tissue development, epithelium development and development related to vasculature (

Figure 4B). GO:MF categories were over-represented by genes associated with transcriptional activity and categories related to regulation of gene expression

(Figure 4C). And finally, in terms of cellular components, differentially expressed genes were over-represented in GO categories related to extracellular space and extracellular regions (

Figure 4D).

One of the most interesting observations is the dramatic transcription repression of long non-coding RNA LINC00665 and LINC02474 (

Figure 4A). We validated the significant decrease in LINC00665 expression in response to ZNF671 expression by real time qPCR in UM-SCC-1 cells (

Supplementary Figure S3). We know from previous work that LINC00665 is an oncogenic long non-coding RNA affecting multiple cancer-related signalling pathways via the targeting of tumor suppressive RNAs such as miR-214-3p and miR424-5p [

20]. LINC00665 can participate in the regulation of five signaling pathways to regulate cancer progression, including the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, TGF-β signaling pathway, NF-κB signaling pathway, PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, and MAPK signaling pathway [

21]. From these observations, we hypothesize that ZNF671 may represent a novel transcriptional repressor capable of affecting multiple signalling pathways by its targeting of long non-coding RNA LINC00665.

Consistent with the above findings, ZNF671 overexpression resulted in significant decrease in the expression of TGFB2, which plays a significant role in various ongoing cellular mechanisms [

22]. Similarly, ZNF671-initiated downregulation of ATF3 is consistent with its role as a negative regulator the growth and migration of human tongue SCC cells

in vitro [

23]. Endothelin 1 (EDN1) was also significantly down-regulated in response to ZNF671 overexpression, and it is known to act as a survival factor in oral SCC cells [

24]. Other down-regulated genes include EPHB1, ECM1, CCDC34, EMP1 and decorin (DCN), many of which have been shown to have oncogenic properties [

25,

26]. A complete list of differentially expressed genes is shown in

Supplementary Table S1.

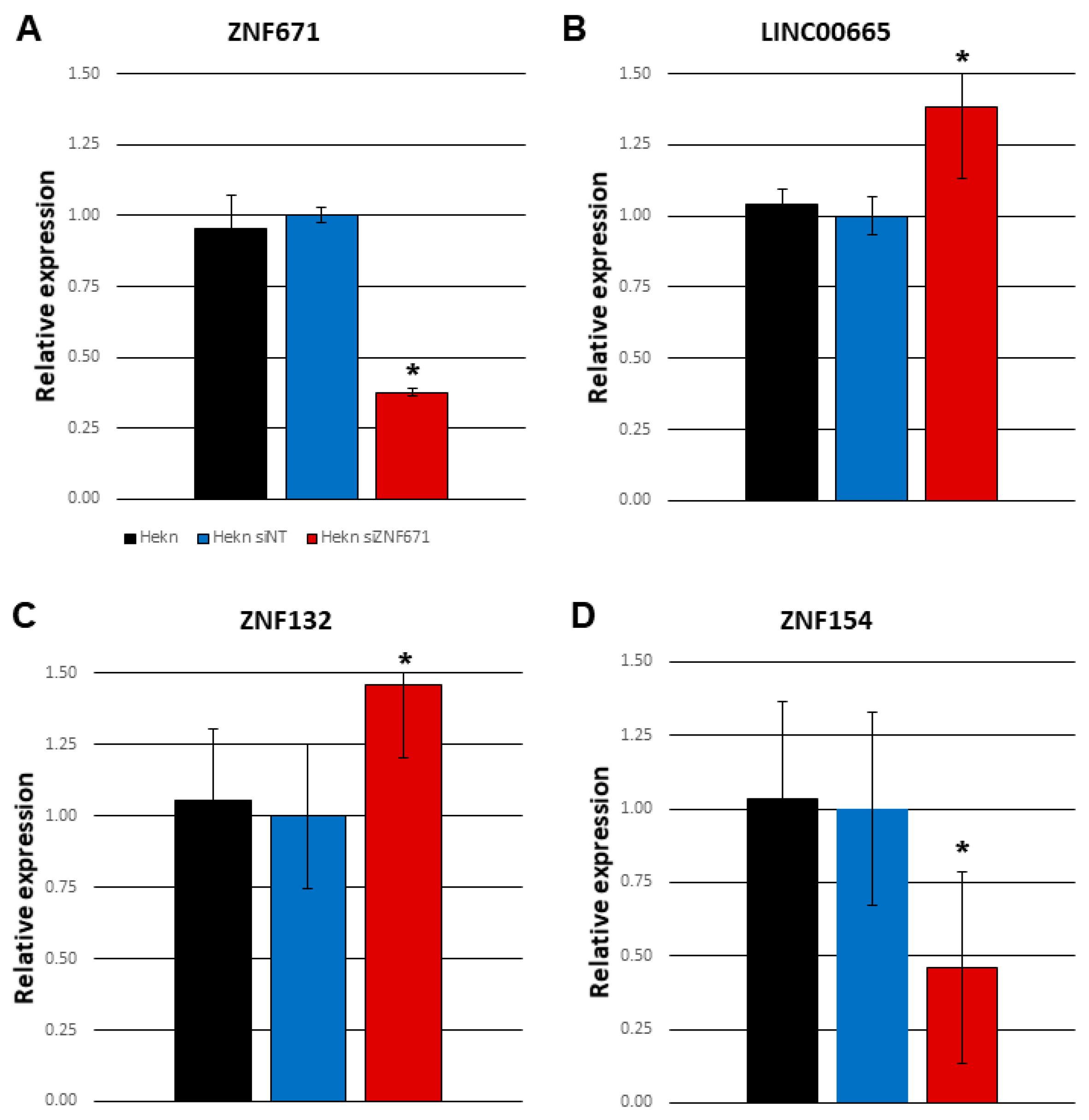

3.4. ZNF671 Knockdown in Human Oral Keratinocytes (Hekn) Can Reverse LINC00665 Repression

In order to further establish the connection between ZNF671 and oncogenic long non-coding RNA LINC00665, we knocked down ZNF671 expression in human epithelial keratinocytes by siRNA targeting ZNF671 (

Figure 5A). Knockdown of ZNF671 expression in these cells was accompanied by a significant increase in LINC00665 expression compared to non-transfected Hekn cells as measured by real-time qPCR (

Figure 5B). This increase was not observed in response to transfection by a non-targeting siRNA control. We also observed that siRNA knockdown of ZNF671 was capable of affecting expression of other ZNF proteins, including ZNF132 and ZNF154 on chromosome 19q13 (

Figure 5C-D). This is consistent with our findings of a large number of genes located on chromosome 19 among the differentially expressed genes shown in

Supplementary Table S1. The exact hierarchy of ZNF protein to ZNF protein targeting and regulation is yet to be determined.

4. Discussion

Promoter DNA hypermethylation of tumor suppressor is thought to be one of the most common transcriptional gene silencing mechanisms in human malignancies. In this study, we confirmed that ZNF671 was epigenetically silenced and hypermethylated in a significant number of HNSCC primary tumor samples when compared to adjacent non-tumor samples from the same patient. Our original DNA methylation profiling of head and neck cancers demonstrated that ZNF671 showed elevated DNA hypermethylation as well as reduced gene expression in most head and neck primary tumors [

5]. This hypermethylation was observed in all three anatomic subsites of HNSCC (oral cavity, oropharynx and larynx). ZNF671 was also observed in the study by Poage and colleagues, appearing in all 3 methylation clusters [

27].

The epigenetic silencing and tumor suppressive properties of ZNF671 is not confined to these cancers. Recent studies have reported DNA methylation of ZNF671 in cervical cancer [

28], nasopharyngeal carcinoma [

29], colorectal carcinoma [

30] and many others [

31]. Results from single cell RNA seq experiments (scRNA) also indicated that ZNF671 played a tumor suppressor role in multiple tumors, and inhibited EMT, migration, and invasion of CNS cancers, lung cancer, melanoma, and breast carcinoma

in vitro [

32]. Overall, elucidating the mechanism of ZNF671 action may provide us with new insights into a role for ZNF671 in cancer treatment.

Survival analysis in two patient cohorts stratifying patients based on ZNF671 expression demonstrated that patients whose primary tumors expressed low levels of ZNF671 showed a significantly decreased survival compared to the rest of the cohort. These observations support a role for these proteins in tumor aggressiveness for HNSCC malignancies. The prognostic relevance of ZNF671 was observed not only in HNSCC, but also in breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA), cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma (CESC), kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (KIRP), lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD), and uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC) solid tumors [

31].

Little is known about the mechanism of action of ZNF671 in HNSCC, and what genes are the target of its transcriptional suppression. We suspect that ZNF671 represses transcription of key genes involved in cancer progression. Up-regulation of ZNF671 in colorectal carcinoma (CRC) cells resulted in suppressive effects on proliferative ability and metastatic potency via the deactivation of Notch signaling, with decreases in expression of Notch1, NICD, HES1 and HEY1 [

30]. Overexpression of ZNF671 in nasopharyngeal cancer (NPC) cells induced S phase arrest by upregulating p21 and downregulating cyclin D1 and c-myc [

33]. And in urothelial carcinoma (UC) cells, ZNF671 re-expression inhibited tumor growth and invasion, in conjunction with downregulation of cancer stem cell markers (c-KIT, NANOG, OCT4) [

34].

Perhaps most interesting in our study is the strong transcriptional repression of oncogenic long non-coding RNA LINC00665 in response to ZNF671 re-expression. LINC00665 is also located on chromosomal 19q13. Recent studies have found that LINC00665 expression was significantly upregulated in many cancers and could be used as a valuable diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic target [

21]. LINC00665 plays an oncogenic role in multiple processes including cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion through various molecular mechanisms [

20]. These mechanisms often include the sponging of microRNAs but may also involve an encoded biologically active micropeptide CIP2A-BP. The role of LINC00665 and its micropeptide CIP2A-BP have yet to be studies in head and neck cancer.

The study as presented does have some limitations. First, only a single HNSCC cell line UM-SCC-1 was utilized in the in vitro studies of ZNF671 overexpression. To date, our attempts to overexpress ZNF671 in other HNSCC cell lines, including SCC-15 and SCC-25, have not been successful, possibly due to its tumor suppressive properties. We are currently characterizing the a ZNF671 overexpression phenotype in the FaDu hypopharyngeal HNSCC cell line. These experiments are now in progress. It is also not clear whether ZNF671 exerts its repressive effect directly on LINC00665 via direct promoter binding, or whether ZNF671 is acting through an as of yet unidentified intermediary. Experiments to identify direct binding sites by ChIP-seq for ZNF671 in HNSCC cells are now underway.

In conclusion, the work presented here represents a preliminary characterization of a novel tumor suppressor gene (ZNF671) and its role in head and neck carcinogenesis. Future studies are needed to address the underlying molecular mechanisms regulating ZNF671 expression in HNSCC and other malignancies, its potential as a diagnostic and prognostic marker, and additional downstream genes that are possible targets for its suppression.

Acknowledgements

This study and was supported by funds from a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR): GlaxoSmithKline Partnered Operating Grant, a grant from InnovateNL, and funds from Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador’s Faculty of Medicine. Dr. Belbin had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

There are no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Maier H, Dietz A, Gewelke U, Heller WD, Weidauer H. Tobacco and alcohol and the risk of head and neck cancer. Clin Investig. 1992 Apr;70(3–4):320–7. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Canadian Cancer Society. [cited 2023 Feb 25]. Canadian Cancer Statistics. Available from: https://cancer.ca/en/research/cancer-statistics/canadian-cancer-statistics.

- Liouta G, Adamaki M, Tsintarakis A, Zoumpourlis P, Liouta A, Agelaki S, et al. DNA Methylation as a Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Predictive Biomarker in Head and Neck Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Feb 3;24(3):2996. [CrossRef]

- Lleras RA, Adrien LR, Smith RV, Brown B, Jivraj N, Keller C, et al. Hypermethylation of a cluster of Krüppel-type zinc finger protein genes on chromosome 19q13 in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2011 May;178(5):1965–74. [CrossRef]

- Lleras RA, Smith RV, Adrien LR, Schlecht NF, Burk RD, Harris TM, et al. Unique DNA methylation loci distinguish anatomic site and HPV status in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013 Oct 1;19(19):5444–55. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Preston R, Soudry E, Acero J, Orera M, Moreno-López L, Macía-Colón G, et al. NID2 and HOXA9 promoter hypermethylation as biomarkers for prevention and early detection in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma tissues and saliva. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2011 Jul;4(7):1061–72.

- Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nature. 2015 Jan 29;517(7536):576–82. [CrossRef]

- Du P, Zhang X, Huang CC, Jafari N, Kibbe WA, Hou L, et al. Comparison of Beta-value and M-value methods for quantifying methylation levels by microarray analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010 Nov 30;11:587. [CrossRef]

- Belbin TJ, Bergman A, Brandwein-Gensler M, Chen Q, Childs G, Garg M, et al. Head and neck cancer: reduce and integrate for optimal outcome. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2007;118(2–4):92–109. [CrossRef]

- Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. 356 p.

- Pearson P, Smith K, Sood N, Chia E, Follett A, Prystowsky MB, et al. Kruppel-family zinc finger proteins as emerging epigenetic biomarkers in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Archives of Otolaryngology--Head & Neck Surgery. 2023;52(1):41–54. [CrossRef]

- Harris T, Jimenez L, Kawachi N, Fan JB, Chen J, Belbin T, et al. Low-level expression of miR-375 correlates with poor outcome and metastasis while altering the invasive properties of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 2012 Mar;180(3):917–28. [CrossRef]

- Babraham Bioinformatics - FastQC A Quality Control tool for High Throughput Sequence Data [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jul 28]. Available from: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/.

- Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013 Jan 1;29(1):15–21. [CrossRef]

- Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014 Apr 1;30(7):923–30. [CrossRef]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550.

- Young MD, Wakefield MJ, Smyth GK, Oshlack A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010;11(2):R14. [CrossRef]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological). 1995;57(1):289–300. [CrossRef]

- Jayakar SK, Loudig O, Brandwein-Gensler M, Kim RS, Ow TJ, Ustun B, et al. Apolipoprotein E Promotes Invasion in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2017 Oct;187(10):2259–72. [CrossRef]

- Zhu J, Zhang Y, Chen X, Bian Y, Li J, Wang K. The Emerging Roles of LINC00665 in Human Cancers. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:839177. [CrossRef]

- Zhong C, Xie Z, Shen J, Jia Y, Duan S. LINC00665: An Emerging Biomarker for Cancer Diagnostics and Therapeutics. Cells. 2022 May 4;11(9):1540. [CrossRef]

- Baba AB, Rah B, Bhat GhR, Mushtaq I, Parveen S, Hassan R, et al. Transforming Growth Factor-Beta (TGF-β) Signaling in Cancer-A Betrayal Within. Frontiers in Pharmacology [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Jul 28];13. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2022.791272. [CrossRef]

- Xu L, Zu T, Li T, Li M, Mi J, Bai F, et al. ATF3 downmodulates its new targets IFI6 and IFI27 to suppress the growth and migration of tongue squamous cell carcinoma cells. PLOS Genetics. 2021 Feb 4;17(2):e1009283. [CrossRef]

- Awano S, Dawson LA, Hunter AR, Turner AJ, Usmani BA. Endothelin system in oral squamous carcinoma cells: Specific siRNA targeting of ECE-1 blocks cell proliferation. International Journal of Cancer. 2006;118(7):1645–52. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Zhang L, Yao C, Ma Y, Liu Y. Epithelial Membrane Protein 1 Promotes Sensitivity to RSL3-Induced Ferroptosis and Intensifies Gefitinib Resistance in Head and Neck Cancer. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022:4750671. [CrossRef]

- Geng W, Liang W, Fan Y, Ye Z, Zhang L. Overexpression of CCDC34 in colorectal cancer and its involvement in tumor growth, apoptosis and invasion. Mol Med Rep. 2018 Jan;17(1):465–73. [CrossRef]

- Poage GM, Butler RA, Houseman EA, McClean MD, Nelson HH, Christensen BC, et al. Identification of an epigenetic profile classifier that is associated with survival in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2012 Jun 1;72(11):2728–37.

- Shi L, Yang X, He L, Zheng C, Ren Z, Warsame JA, et al. Promoter hypermethylation analysis of host genes in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancers on histological cervical specimens. BMC Cancer. 2023 Feb 20;23(1):168. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Zhao W, Mo Y, Ma N, Midorikawa K, Kobayashi H, et al. Combination of RERG and ZNF671 methylation rates in circulating cell-free DNA: A novel biomarker for screening of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2020 Jul;111(7):2536–45. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Chen FR, Wei CC, Sun LL, Liu CY, Yang LB, et al. Zinc finger protein 671 has a cancer-inhibiting function in colorectal carcinoma via the deactivation of Notch signaling. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2023 Jan 1;458:116326. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Zheng Z, Zheng J, Xie T, Tian Y, Li R, et al. Epigenetic-Mediated Downregulation of Zinc Finger Protein 671 (ZNF671) Predicts Poor Prognosis in Multiple Solid Tumors. Front Oncol. 2019;9:342. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Luo J, Jiang H, Xie T, Zheng J, Tian Y, et al. The Tumor Suppressor Role of Zinc Finger Protein 671 (ZNF671) in Multiple Tumors Based on Cancer Single-Cell Sequencing. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1214. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Wen X, Liu N, Li YQ, Tang XR, Wang YQ, et al. Epigenetic mediated zinc finger protein 671 downregulation promotes cell proliferation and tumorigenicity in nasopharyngeal carcinoma by inhibiting cell cycle arrest. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017 Oct 19;36(1):147. [CrossRef]

- Yeh CM, Chen PC, Hsieh HY, Jou YC, Lin CT, Tsai MH, et al. Methylomics analysis identifies ZNF671 as an epigenetically repressed novel tumor suppressor and a potential non-invasive biomarker for the detection of urothelial carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015 Oct 6;6(30):29555–72. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).