2. Case Series Presentation

We present bariatric surgery complications treated at our hospital by the bariatric surgery team over a seven-year period. Major complications are recorded in detail while minor complications such as pos operative nauseas, vomiting after surgery and phlebitis cases were excluded.

Demographics and preoperative Body Mass Index (BMI) of patients that presented with complications after bariatric surgery are shown on

Table 1.

Case 1

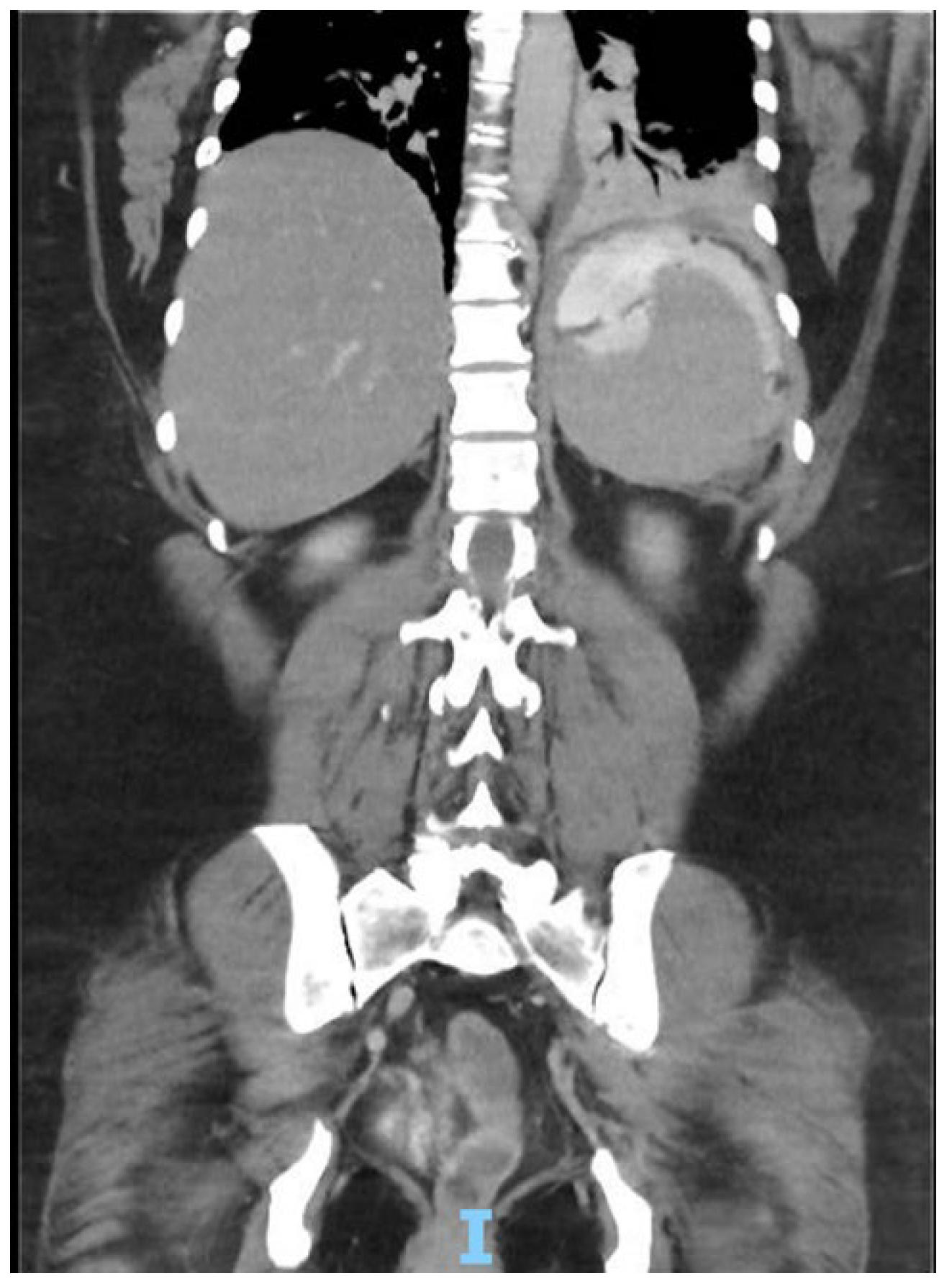

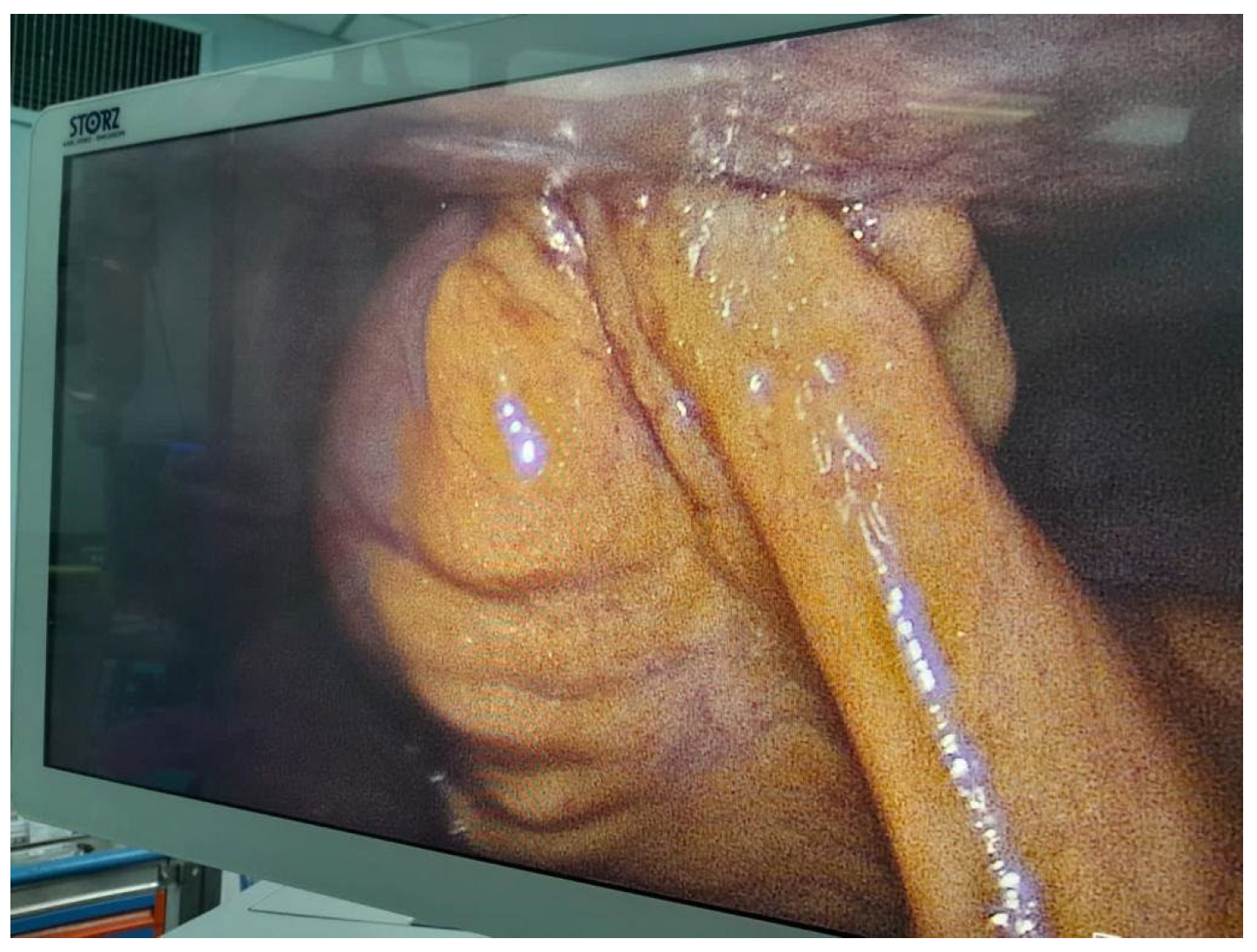

Patient arrives to the emergency room 48 hours after gastric sleeve surgery, she was admitted for abdominal pain referred to the left shoulder, a computer tomography (CT) was performed with evidence of leak at the gastroesophageal junction, a left subphrenic collection and pleural effusion of left predominance [

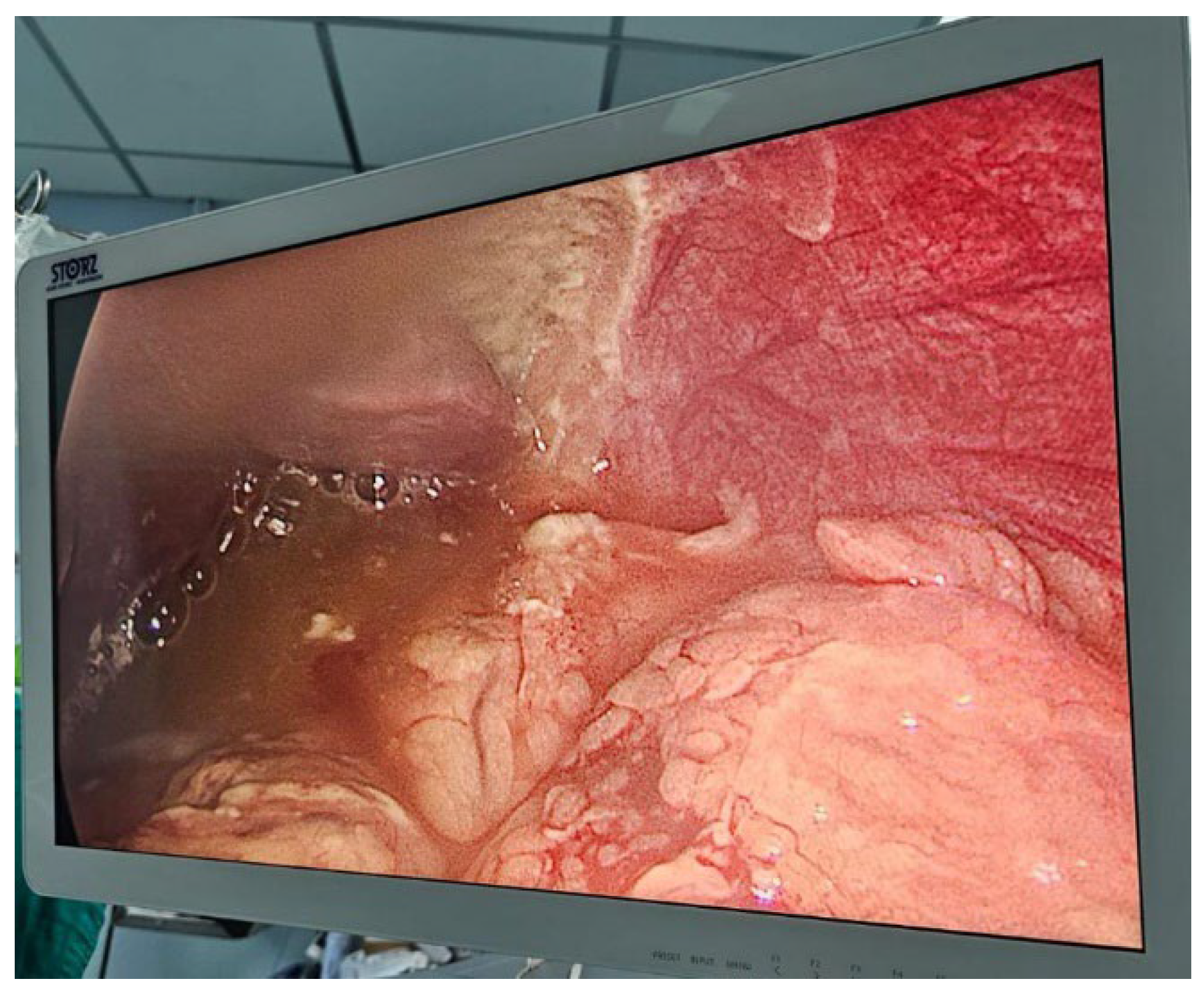

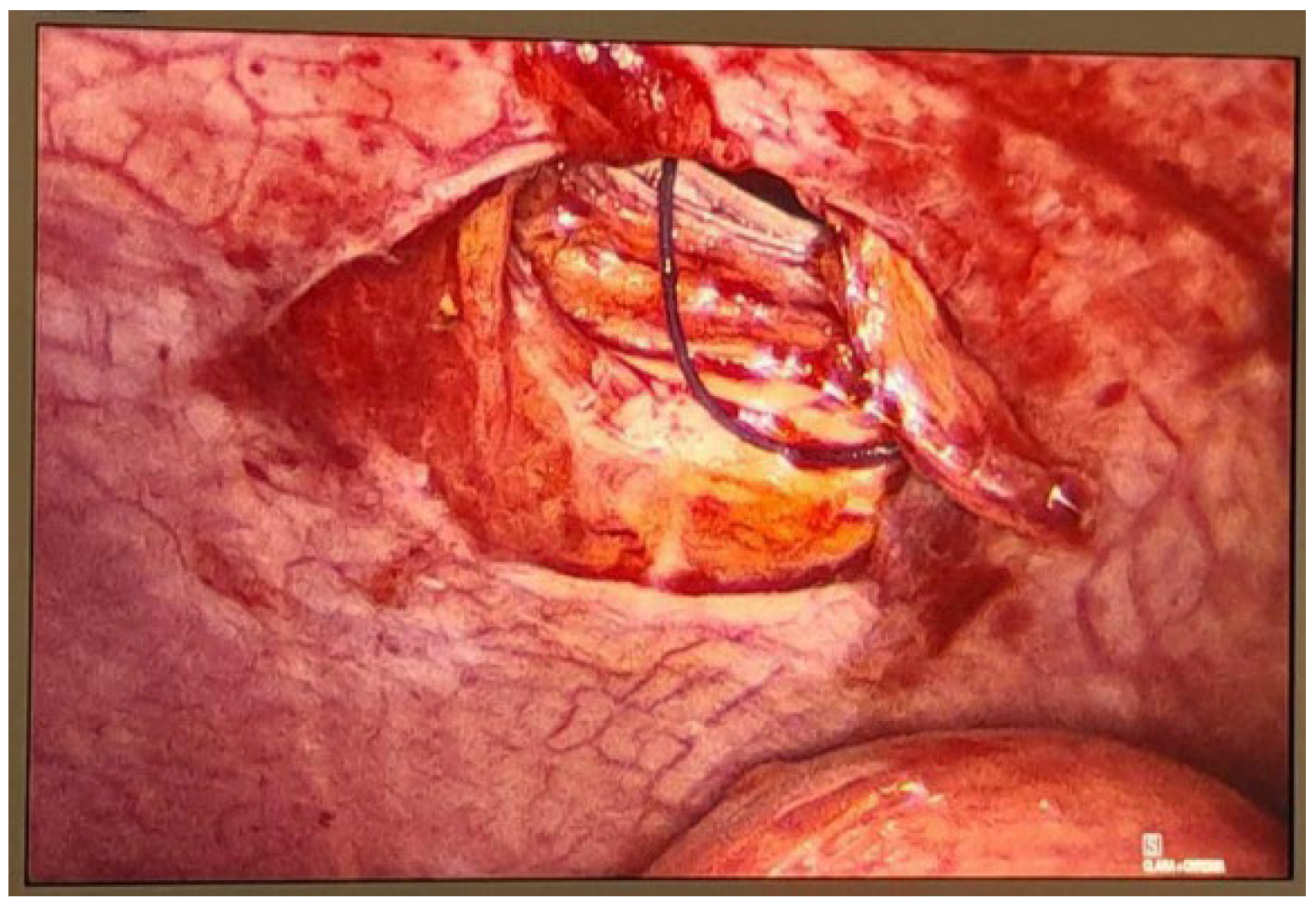

Figure 1], she is taken to operation theatre and laparoscopic lavage and drainage is performed [

Figure 2]. Treatment continues with IV antibiotics and parenteral nutrition. Thirteen days after re-intervention she presents deep venous thrombosis of the right lower limb and pulmonary thromboembolism of a segmental branch of the left lower lobe, she was managed with full anticoagulation and high flow cannula. She was then admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for 72 hours for observation. After stabilization is carried out, endoscopic management of the leak site with an Over-the-scope clip (OVESCO) is performed and mixed nutrition is installed, outpatient management is given with enteral nutrition for 4 weeks however the leak persists so after placement of vena cava filter, she is submitted for revisional Roux en Y gastric bypass [

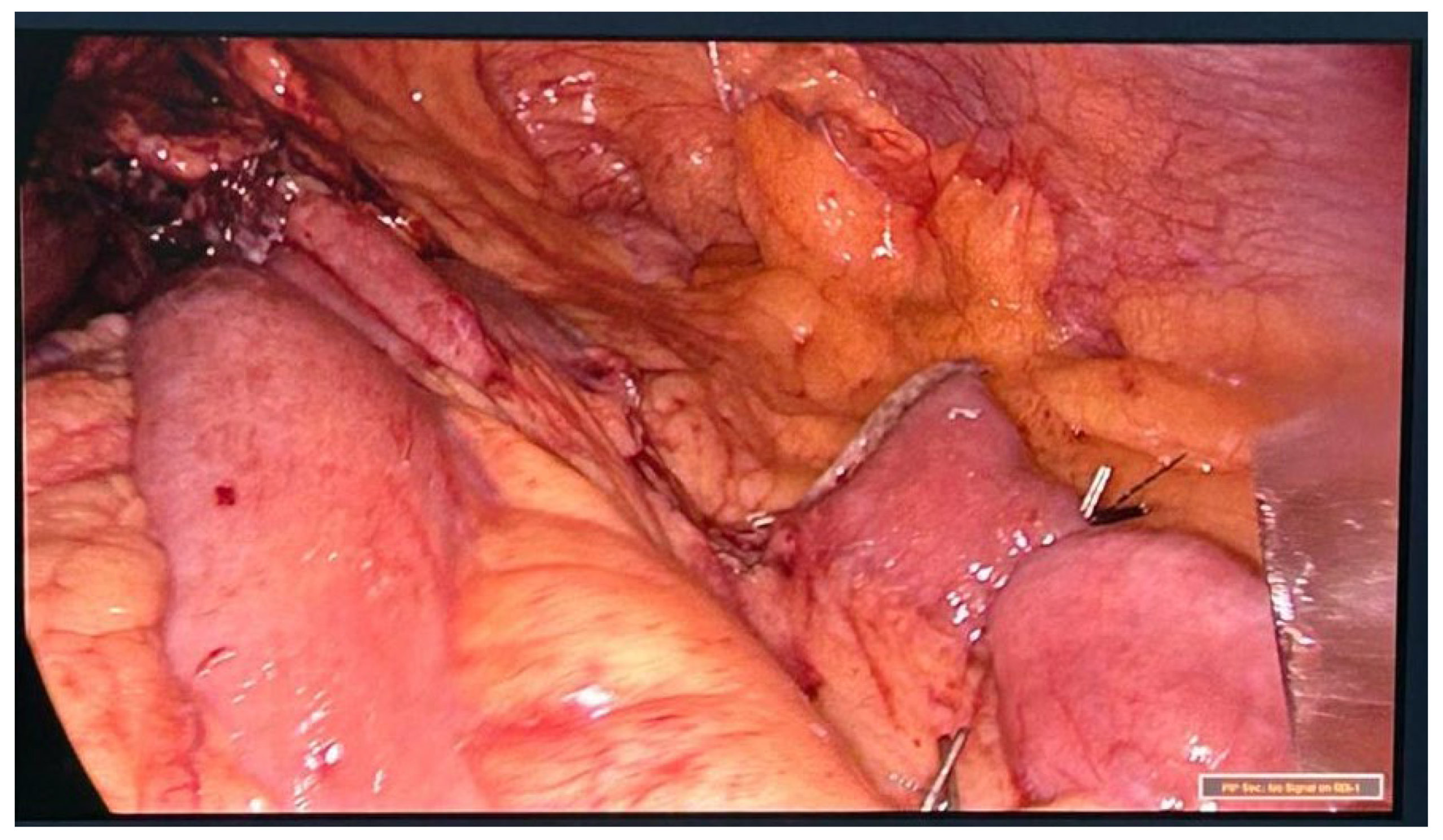

Figure 3]. Patient is discharged at 72 hours with complete resolution of the fistula, current follow-up at 4 months has been uneventful.

Case 2

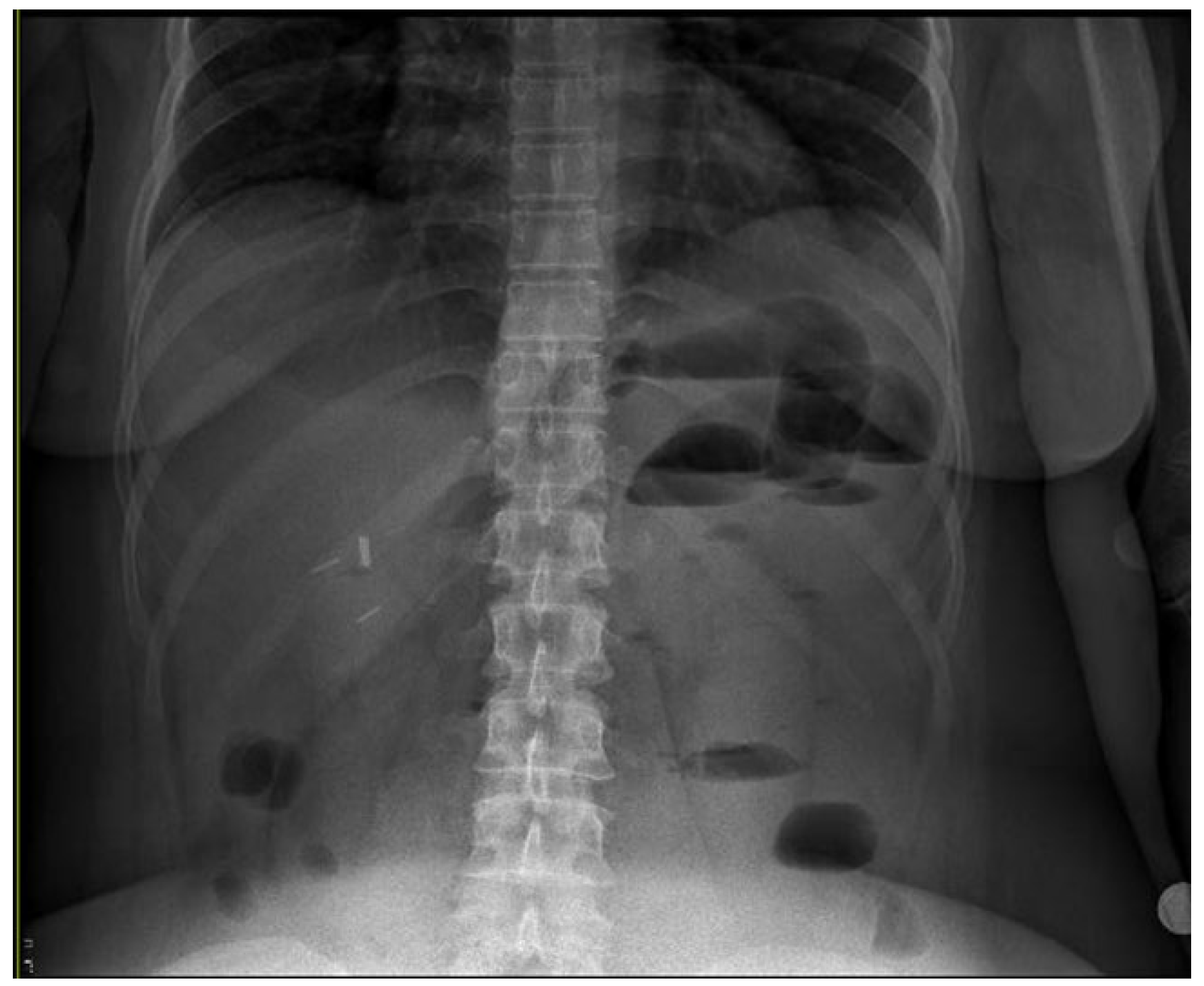

Elective laparoscopic gastric sleeve is performed, ports are closed with trans facial stitches. Patient is discharged at 48 hours and 12 hours after, she begins with bilious vomiting and pain in the left flank. Upon physical examination one could find tenderness and palpable lump which would not reduce upon manipulation. An acute abdomen X rays’ series is ordered with evidence of an intestinal limb trapped at the site of the port in the left hypochondrium abdominal wall and intestinal obstruction [

Figure 4 and

Figure 5]. She is taken to operative theatre and reduction of the incarcerated intestinal loop is performed, no ischemic damage to the bowel is detected so closure of the port by means of laparoscopy is done [

Figure 6 and

Figure 7].

Discharge is given at 24 hours postoperatively and follow up has been uneventful eleven months after surgery.

Case 3

Patient admitted to our service nine days after laparoscopic gastric sleeve (06/14/2023) in another country. She presented with a history of epigastric left hypochondrium pain associated with tachycardia and hyperlactatemia. CT scan is performed showing free fluid and signs of peritonitis. She is taken to the operation theatre for laparotomy, upon exploring the cavity a contained bilious/purulent collection is evidenced so lavage with 10 liters of saline solution is performed, no evidence of the leak is found in the sleeved remnant stomach or small bowel.

In the postoperative period, the patient showed signs of sepsis, so control CT scan was ordered, findings showed residual collections that were managed by interventional radiology. She shows better general health conditions, however one month after laparotomy at an outpatient consultation the drain output changed with evident food remains on it. She also presented poor healing of the abdominal wound with partial dehiscence and food remains also coming out of the cavity through the wound. Management was given initially with nasoenteric tube feeding but lack of positive results in decreasing fistula output leads us to indicate OVESCO 10mm clips at the fistula site (33 cm from the incisors) in the endoscopy suite. This measure did not show any improvement whatsoever, so a self-expandable metallic stent was placed to reduce the output of the fistula.

Despite adequate nutritional interventions and less invasive therapies, gastro-cutaneous fistula persists, and healing of the operative wound is not satisfactory.

The patient was then admitted for preoperative optimization and revisional surgery to a laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with fistula takedown is performed with no intraoperative or immediate complications approximately 21 weeks after index surgery. Six days later she was reoperated due to dehiscence of the surgical wound; the wound was closed without any other injuries being found.

She had good oral tolerance and was discharged. At the control appointment in December 2024, partial dehiscence of the surgical wound was observed, which was decided to manage non operatively.

In follow-up appointments in 4 months later, the patient reported poor food tolerance with hypersalivation and dysphagia. Laboratory results accused severe hypoalbuminemia as well as microcytic anemia, she was then admitted for mixed nutrition at surgical ward. During this hospitalization, she presented signs of severe disorientation and refeeding syndrome was diagnosed.

The patient is given further nutritional therapy and electrolytes were corrected, she is then discharged oriented and with no signs of neurological impairment.

On May 23rd, 2024, while at home she presented sudden deterioration of her mental status and was brought to the institution emergency room (ER) were she required mechanical ventilation and despite resuscitating maneuvers she died from severe electrolyte imbalance.

Case 4

Patient comes to our service with diagnosis of gastric sleeve torsion and chronic malnutrition. She underwent laparoscopic gastric sleeve 5 years ago at another country, two years later a laparoscopic gastric re-sleeve was performed and 1 month later she had gastric sleeve stenosis being then submitted for endoscopic dilation. She tolerated liquids and soft diet, but persists with vomiting, salivation upon solid food uptake. Patient loses weight until reaching a BMI of 29, with significant loss of lean mass, reduction in mobility, depressive symptoms, reduction in quality of life, and hypophosphatemia. A tomography was performed showing gastric sleeve torsion. Hypophosphatemia was corrected parenterally, mixed nutrition and physiotherapy were given for 1 month, before surgery.

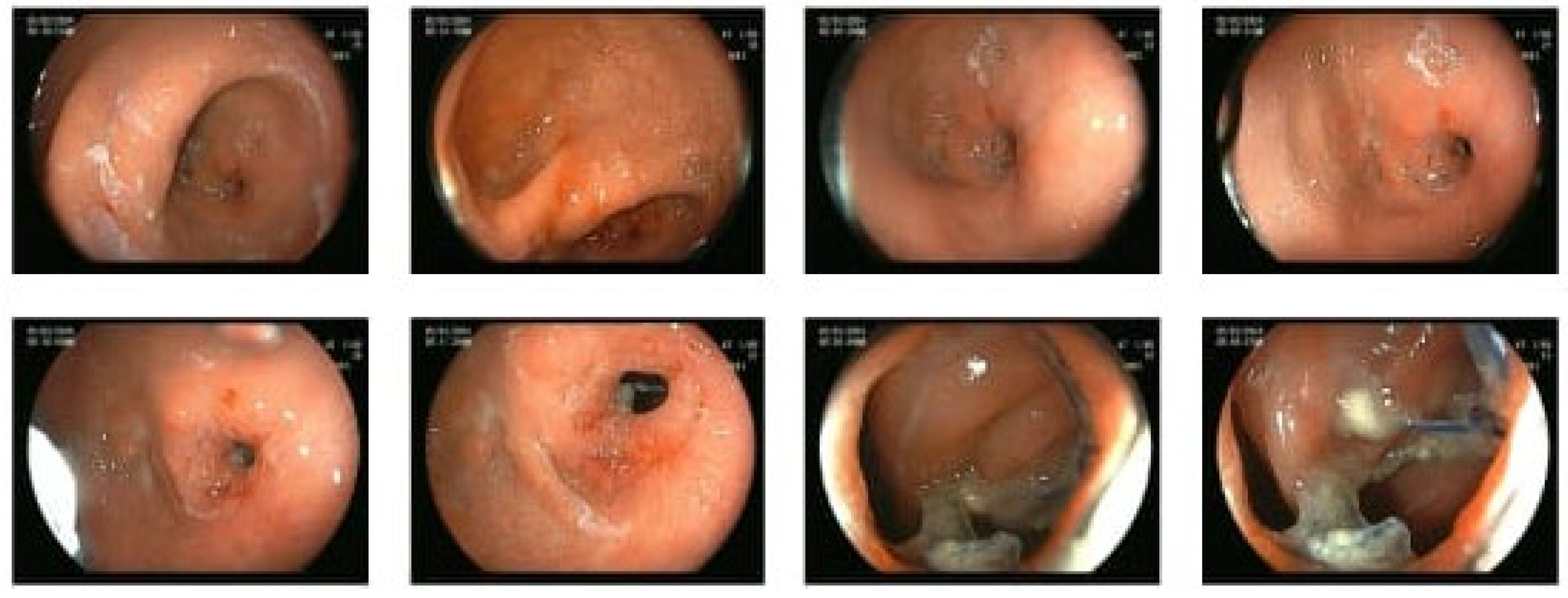

In May 2023, she underwent conversion to laparoscopic gastric bypass, with manual gastro-jejunal anastomosis. one month after she developed new episodes of salivation and poor tolerance to soft and solid diet. Two successful endoscopic dilations were performed [

Figure 8], but the symptoms persisted, ranging from daily to 3 times a week. Supplementation of vitamins and protein were indicated. During this period a conventional appendectomy was performed for acute inflammatory abdomen. A new endoscopic dilation was performed, 10 months after surgery, with triamcinolone injection.

Patient evolves with adequate tolerance of solid diet, normal hemoglobin values and nutritional parameters, she performs physical activity and weights, improved quality of life, BMI 25, in a 6-month follow-up after the last dilation.

Case 5

Patient presents to the ER forty-eight hours after a one anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB) was done at another service, he complaints abdominal and showed sepsis sings, he was tachycardic, elevated lactate and respiratory distress. After initial IV hydration and stabilization he was taken to theatre for exploration laparoscopy, due to poor visualization surgery was converted and a punctiform perforation in the afferent loop was detected, enterorrhaphy was performed and the patient went to the ICU for further management. On the 7th day after reoperation, he presented clinical decline of the general state with abdominal distention, fever, tachycardia and worsening of abdominal pain. A new CT scan was done, and it showed perihepatic, peri splenic free fluid and purulent collection in the hepatic hilum so he was taken to theatre and cavity lavage and drainage was done without evidence of other lesions. He is then managed with intravenous antibiotic therapy and notable clinical improvement is seen so he is discharged. In a follow-up visit one month after discharge he shows no symptoms of dumping or sepsis, only referring a few diarrheal stools.

At 4 months postoperatively he is in good shape and exercises regularly, on outpatient visit an incisional hernia was detected.