Displaying Data

Extracted data followed detail in the table below;

First author,

year of

publication, country

of origin,

|

Principal objective

of the study

|

Reporting

focus

|

Design/methods of study |

Setting(s)

|

Participant characteristics

|

The extracted data would be analyzed for both associations and context depending on the design of the primary study. The approach is necessary to prevent the comparison of unlike study identifiers.

A thematic synthesis was done on the analyzed data from all included studies. Discussions and conclusion were then made.

(Bishop-Williams et al., 2013)

How early breast cancer symptoms are recognized by women

As documented earlier, the single and initial most common way of early BC diagnosis is through the identification of a lump in the breast.

A descriptive study was conducted in Turkey, by Somayyeh & Aydogdu (2019), among 380 women aged 20 years and above. This study assessed early detection behaviours; vis a vis symptoms discovery approaches. Participants engaged in breast self-examination (BSE), clinical breast examination (CBE) and mammography (MMG) as early detection practices. In this study, the absolute numbers indicated that the most commonly adopted symptom recognition behaviour among the three above was through BSE. In addition, the tendency of women to frequently involve in these behaviours was significantly linked with some level of fear of breast cancer disease.

Similarly, in 5 focus groups discussions of 39 women (20 years and above), BC symptoms experienced included breast and armpit lump, breast stiffness, and nipple discharge (Tuzcu & Bahar 2015). The participants also noted that these manifestations could be detected through effective BSE. The women therefore registered that their capacity and efficacy could be built for BSE, through proper information by health professionals especially on the media.

Khakbazan et’al. (2014), have posited that symptom recognition and interpretation by women are salient variables in early detection and diagnosis. In their study, the experiences (appraisal) of women presenting with self-detected breast cancer symptoms were extensively explored. With 27 Iranian participants aged 26-71 years, their qualitative inquiry found out that; symptoms talked of were breast lump with/without pain, breast skin changes, inverted nipple, swollen hands, fever, and fatigue. Participants indicated their unintended, rather accidental self-discovery of symptoms. Notably, some women detected their symptom (s) whiles showering and after menstruation. More so, obvious symptoms such as skin and nipple changes, pain etc aided the women to establish abnormalities.

In congruence to the above findings, a cross-sectional survey in Malaysia involving 1192 women, aged 20-64 has confirmed that; to promptly identify BC symptoms and subsequently present for early diagnosis, majority of women engaged in BSE (62.8%) and CBE (53.3%) practices (Farid et’ al., 2014). These attitudes were found to be significantly associated with variables as would be evident below

Also, a qualitative study of ethnically varied women in London has also resonated the findings of Tuzcu & Bahar 2015; Khakbazan et’al. (2014), that, women recognized a breast lump as a sign of breast cancer (Marlow et’ al. (2014).

In a quantitative inquiry by O’Mahony et’ al. (2013), women (53.8%; n=449) described their breast symptoms to have occurred by chance. This finding is similar with that of Khakbazan et’al. (2014), who documented BC symptoms were accidentally discovered by the participants. Again, O’Mahony et’ al. (2013), noted that, the symptom experienced by women was predominantly a breast lump; and this agrees with Tuzcu & Bahar (2015); Khakbazan et’al. (2014) & Marlow et’ al. (2014).

Using a different methodology, Dye et’ al. (2012), employed a mixed method approach to assess how and what breast symptoms are experienced by Ethiopian women as well as the provocative factors for seeking health care. The study which involved 69 participants’ also showed that the initial symptoms experienced by women were breast lump (82.6%). Their narratives indicated that additional symptoms experienced included itching/burning on the breast or at the location of lymph node. Subsequently, some women also reported pain near/around the initial lump. Further, some women experienced an additional lump before the ultimate diagnosis.

Conversely to Khakbazan et’al. (2014) & O’Mahony et’ al. (2013), a qualitative study which explored how women with breast symptoms present to the health facilities, conducted by O’Mahony et’ al. (2011) in Ireland indicated that, breast symptoms experienced by women were self-discovered. The study which included 10 women ranging from ages 25-55 years also indicated, that symptoms experienced spanned from breast lump, breast pain, both breast lump and pain, and a bloody nipple discharge. Performance of BSE was found to be varying among the women, and was likened to a woman’s knowledge and skills on the concept. In addition, it was documented that participants discovered their symptoms through breastfeeding, during grooming and while taking their bath.

In a focus group discussion to explore factors relating to the performance of breast cancer screening programs, views from a section of participants echoed that BSE, CBE and MMG are vital health promotion and prevention behaviours. The study emphasized the enhancement of knowledge and the understanding of women on screening approaches. In their opinions media involvement and observing a national day of breast cancer would help in facilitating prevention and screening behaviours (Keshavarz, Simbar & Ramezankhani, 2011).

Interpretation of BC symptoms following recognition

Khakbazan et’al. (2014), have documented that though Iranian women established their BC symptoms as abnormalities, they labeled them as of less concern. This led them to resorting to the monitoring of initial symptoms for additional ones or progression. Also, assertion was made by the authors that, seriousness perception of breast symptoms was a function of personal understanding of participants, periodic examination and comparison. Participants with intense seriousness perception of their symptoms were more likely to seek prompt attention. Further, seriousness perception was influenced by knowledge on risk of breast cancer. Women who knew they were at risk for breast on account of family history, and increased incidence in their localities, labeled their initial symptoms as requiring prompt attention. Again, different breast manifestations yielded different interpretations. For instance, breast pain without lump detected, weakness, swelling of the hands, fatigue, and fever were labeled as associated with systemic sicknesses. Conversely, a mass in the breast with/without pain was perceived to be either of benign or malignant origin.

Another quantitative study in Ireland (O'Mahony et’ al., 2013), has indicated that women with breast lumps were knowledgeable and regarded their self-discovered symptom as possibly related to breast cancer. This finding echoes previous one that awareness and knowledge on risk of BC corresponds to intense serious perception.

Also, Dye et’al. (2012), reported on findings that mirror earlier ones that, following an initial experience of breast lump, most women did not perceive it to be cancer-related, neither anything to be given aggressive attention to. According to the study, this attitude lingered among participants until there were changes in symptoms.

According to O’Mahony et’ al. (2011), prompt help seekers were of the thought that a breast lump could be diagnosed as breast malignancy, adding that early detection is the way out. Similarly to previous study findings, the knowledge of perceiving a breast lump as probably indicative of breast malignancy was found to be sourced from having family history of cancer (s), and friends with breast malignancies.

Women’s reactions following the detection of the BC symptoms

For women in Iran, as was reported by Khakbazan et’al. (2014), symptom monitoring was adopted after discovery until the onset of additional and or intense symptoms. At this stage the women began to query the possible cause of their symptoms. Khakbazan et’al. (2014), also hinted that, though most women thought of benign growths, a few feared it could be malignant. These emotional reactions led the women to purposively seek clarification by selectively consulting others. Thus participants opened up to social acquaintances such as family relationships, people with prior experience of breast disease, and in some few instances health professionals. It must be noted also that, clear and accurate information from their social networks influenced the women to seek prompt health care. The information as reported included the promising outcome following early presentation and treatment. In addition, few participants also resorted to the media for better understanding of their assumptions.

Mirroring the above findings, O’Mahony et’ al. (2013), have also documented that, following self-discovery of breast symptom, women checked their symptoms occasionally to identify any change (79.1%), communed with their creator about the symptoms (42.9%). ,told others about their symptoms (94.7%) ,consulted others about visiting the hospital (42.6%). Remarkably, the women sort for help within one month. Further, it was also documented that, the Irish women exhibited emotional response of fear following identification of breast symptom (s).

Earlier as described, some participants did not know/perceive that a breast lump could be a symptom of breast cancer; neither did they consider it something of concern. Corroboratively, Dye et’al. (2012), describes that most Ethiopian women were not perturbed by the initial breast lump experience. In other words the needed attention was not metered out to their symptom (s). In fact they ignored them.

Corroborative to findings by O’Mahony et’ al. (2013), O’Mahony et’ al. (2011), found out in their study that, women who were classified as prompt health seeker sought help within one month after discovery of symptom (s). O’Mahony et’ al. (2011), also posited in resonance that, following symptom discovery prompt help seekers confided in their social acquaintances and relatives for support. The attitude of prompt help seeking was significantly associated with a positive attitude towards health, varied magnitudes of fear, confidence in health care systems (including knowledge and expertise of health professionals), and accessibility to a health care setting.

Facilitators to earlier presentation for earlier BC diagnoses

Per earlier positions, the relationship between BSE, CBE, MMG and earlier symptom discovery has been established. Notwithstanding the fact that the frequency of these approaches has been significantly associated with different levels of fear; Somayyeh & Aydogdu (2019), emphatically stated that rather, medium level of fear associated with BC diagnosis expedites women to frequently perform BSE, have CBE and MMG. They further stating that, prompt help seeking was compromised among women with low and high levels of fear. This association was also documented to be underpinned by varied levels of seriousness perception and fatalism. This implies that women with medium levels of BC fear are likely to adopt more efficient measures to dealing with the fear as compared to those with the extremes. The rate of early detecting and diagnosis was hence relatively higher among women with medium fear levels, & seriousness and fatalism perception (Somayyeh & Aydogdu, 2019). Clearly, the fear of breast cancer plays a pivotal role in screening and earlier detection programs. The resultant effect could therefore be positive or adverse depending on the level of fear.

Kocaöz et’al. (2018), conducted a semi-experimental study in Turkey, to define the effects of education on the attitudes and behaviours of women towards early diagnosis and screening programs. The study (n=342) found out that, creating awareness and providing educational programs on early diagnosis for women, is directly proportional to increasing willingness to partake in screening programs (BSE,CBE, MMG). This also leads to behaviour change, increasing seriousness perception, and driving a positive health belief attitude etc. Also, Kocaöz et’al. (2018), posited that, an initial educational program does not guarantee an indefinite positive early-diagnosis attitudes. The study therefore recommends persistency and consistency in the provision of educational programs by health care providers. Further, Kocaöz et’al. (2018), documented that seriousness perception could be improved by performing breast cancer risk assessment for women; this way, women would know their levels of risks. This could pose some level of fear, which in turn may facilitate their involvement in screening programs and earlier presentation. This assertion is consistent with the findings of Somayyeh & Aydogdu (2019), which emphasizes on medium breast cancer fear levels to increase seriousness perception, and subsequent involvement in earlier diagnosis practices.

Also, Adjimah (2017) involved 1,259 respondents aged between 20-45 years in a study in Ho (Volta-Ghana). The study reported on women’s engagement in breast screening practices, and the facilitators. From the study, even though the general involvement in BSE, CBE, MMG was low, almost 30% of the respondents were reported to have engaged in one form of breast examination practice or the other. This early detection attitude was documented to be significantly associated with advice by nurses/doctors, formal education of respondents, breast health education at health care facilities, distance to breast examination centre, level of knowledge on breast cancer, and awareness of breast examination practices. Interestingly, the study results showed that, the probability of a woman to engage in earlier detection practices was higher among those with primary level education (2.5 times) than their counterpart with tertiary level education. Adjimah, (2017), therefore asserted that only some basic form of formal education is required to aid women in breast screening practice for early detection.

In another recent study (Scheel et’al., 2017), the beliefs of 401 women (mean age; 41years) were assessed to establish the association with early detection practices. The study results delineated a link between one’s belief and earlier presentation. Thus beliefs not rooted in scientific evidence yielded late presentation. Conversely, beliefs grounded in science promoted early presentation practices. The assertion therefore is that, women’s belief on BC must be understood, refined or aligned with science to promote earlier presentation. Scheel et’al. (2017), further posited that, understanding the local beliefs of women on BC is a requirement for developing effective early detection interventions.

Another phenomenological investigations in Turkey (Tuzcu & Bahar 2015), adopted a focus group approach to among others, explore the facilitators for BC screening uptake. In this study however, focus was rather on only migrant women in Turkey. The results of the study showed that; knowledge and awareness on BC, self ability to perform BSE effectively, social/family support, and the preference of a female health professional to perform screening exercises were triggers for participation in earlier presentation practices. Fear of BC diagnosis, stigma, advance stages and associated mortalities, and perceived loss of feminity were predominantly discussed among the participants. In addition, the women registered that; means of transportation to the screening facilities, and the implementation of community screening programs as possible factors for earlier presentation practices.

In the quantitative inquiry by Farid et’ al. (2014) as previewed earlier, several facets of variable accounted for the uptake of BC screening practices. Notably, proximity to a BC screening and income of the women were key facilitators. Majority of the respondents (50-95.5%) lived within 20km from the hospital/clinic; a distance considered in their study as nearer. Similarly, women with higher income (within the bracket of RM 1000-1999) were more likely to undergo CBE. Also 50%-98.9% of the Malaysians in their study, recounted their preference for examination of their breast by a female health professional. More so, spousal support encouraged majority of the respondents to engage in breast screening. Paradoxically, Farid et’ al. (2014) pointed out clearly that CBE uptake was highest among the group with the lowest BC knowledge. A situation described as a function of the active health intervention practices by health professionals.

In another qualitative inquiry involving 54 ethnically diverse women, Marlow et’ al. (2014), explored the perceived facilitators for help-seeking. It is documented that the ability of a women to label a symptom as a possible malignant manifestation is a function of earlier diagnosis.

Consistent with previous findings, good attitude of health professionals, fear of BC diagnosis and mortality, prior BC experience e by friend(s)/ family relative (s), and placing a high value on life were perceived to be facilitators for taking earlier action.

Emphasizing findings by Marlow et’ al. (2014), Khakbazan et’al. (2014), found that most common facilitators for early presentation included; effective interpretation and labeling of symptoms, changes in manifestations especially the onset of breast pain as additional symptom. Also, social support through effective and selective interactions, fear, and seriousness perception were noted as triggers for earlier presentation. More importantly, reliable sources of knowledge and risk perception were also identified as common with participants who sought prompt health care.

O'Mahony et’ al. (2013), repeated their study using a quantitative approach to describe the factors that influence Irish women to seek help after self- discovery of breast symptoms. Comprising of women (499) 18 years and above, they found out that, influencing factors and prompt help seeking behaviours after self-discovery of breast symptoms were; good access to health, positive attitude towards health (53.8%), fear on symptom discovery, disclosure of the symptom (s) to another person (94.7%), and knowledge of the breast changes. In addition, women who were termed as prompt help seekers (69.9%), sought help within a month after symptom discovery. The majority of the Irish women (62%; n=449) noted that having lesser family commitments, and some degree of family support triggered prompt action.

Forbes et’ al. (2012), implemented an evidence-based intervention to promote early presentation among elderly women with BC symptoms. After delivery of the PEP intervention to 830 women by trained health professionals, the study found out that, BC awareness multiplied seven folds at one month relative to a two-fold outcome in the control group. Forbes et’ al. (2012), remarked clearly that, the implementation of the PEP intervention has a 95% confidence level of reducing delay in BC diagnosis among older women. Also, the training of health professional to deliver the intervention built their capacity, to positively interact and communicate with the older women hence motivating the participants.

In the study by Dye et’al. (2012), participants’ ultimate trigger (s) for taking action following the initial symptom experienced were that; they experienced additional symptoms to the original one; there were changes in the initial symptom experienced. Generally, almost 3/4th of the participants sought for help owing to the dynamism of an initial symptom, and or an experience of additional symptom (s). Further, some women noted they were motivated by their families to take action. Again, in their study, a section of the participants reported that no deliberate action was taken, however their breast cancer was accidentally diagnosed secondarily to visiting the health setting for other reasons.

Macheneri (2012), presented the factors that influence participation in BC screening practices with focus on reproductive women. Though BC screening uptake was generally low, at least between 27.3% to 44.1% (n=245) of the participants were involved in one form of earlier detection practices or the other. For this statistics, the study established positively significant associations between BC screening uptake and factors such as; socioeconomic status, level of knowledge on BC, educational level, BC heath education, marital status. That is to say that, relatively high socioeconomic status, appropriate information on BC, at least having a secondary level education, continual health talk and guidance by health workers, and being married were more likely to facilitate women’s participation in earlier presentation practices. It is worth emphasizing again that, of the women who involved in BC screening practices, 78% had second cycle education. The finding resonates that fact that ability to understand facts on BC and the tendency of screening uptake is not a synonymous with attaining very higher levels of education; a development good for health education and outcome.

Indifferently, the study by O’Mahony et’ al. (2011) as elucidated above, has also documented that facilitators to prompt/earlier presentation include: a woman’s knowledge and skills on BC and BSE, positive attitude towards health, varied magnitudes of fear, confidence in the health systems (including knowledge and expertise of health professionals), and accessibility to a health care setting. Again, prompt help seeking for breast symptoms was associated with symptom disclosure to others, fatalism perception, positive notion that breast malignancy is curable or could be treated. Consistent with earlier findings, O’Mahony et’ al. (2011), remarked that prompt help seekers had strong religious belief attached to their positive attitudes. Moreover in their study, a key finding was that, prompt help seekers had strong confidence in conventional hospital treatment for BC; considering alternative treatments as adjunct approaches.

A focus group discussion of 46 elderly Turkish women (60-75years) was robustly conducted to portray the experience of women about breast screening practices; and to include the perceived facilitators. A review of the study (Kissal & Beser 2011) showed that, fear of breast cancer metastasis, self-care deficit, and the possibility of a positive screening result triggered women to take action. More so, variables such as familial history, family/social support, confidence in health professionals and systems, as well as health education especially on the media motivated and or enlightened women on breast screening practices. In addition, the study reported that several women emphasized the facilitative role played by feminine medical officers for breast screening programs and earlier presentation. It is important to note however that, the stands/preference of feminine health workers by women in the Turkish society cannot be over-emphasized.

Mirroring Kissal & Beser (2011); Ersin, & Bahar, (2011), employed similar methodologies to investigate women’s breast cancer early diagnosis behavior; to include the perceived facilitating factors. Rather with women aged 40 years and above, the narratives of the 43 participants indicated that, perceived factors for earlier presentation and diagnosis include; awareness/education, tolerant and concerned professionals, free health care. Regarding awareness and education, the participants believed that early presentation and diagnosis practices could be achieved primarily through health education activities. Among these activities as pointed out by the participants included; media involvement, administration of brochures, seminars, telephone reminders, and home visits. Further, free transportation to the health setting, and preference for a feminine medical doctor were acknowledged.

A qualitative study which also adopted focus group discussion involving 70 participants, aged 20-45 in Iran, emphasized that; education, positive health attitude, family support as factors for promoting breast cancer screening among women (Keshavarz, Simbar & Ramezankhani, 2011).

In an attempt to increasing breast cancer awareness and to promote early presentation and diagnosis, Forbes et’ al. (2011) employed randomized control trial using an educational intervention (Promoting Early Presentation (PEP)). The study randomized 867 UK women aged 67-71, with a prolonged follow-up trials. In effect breast cancer awareness was assessed at baseline, a month on, after six months, a year on, and after 2 years. The result of the study clearly delineated that the administration of the PEP-intervention yielded a correspondent increase in breast cancer awareness. The aim and resultant effect of this study did not only maximize breast cancer awareness, but equipped women with the necessary breast screening skills, confidence, and motivation to aid in early presentation and diagnosis. A follow up to this study with similar results is what has been presented previously by Forbes et’ al. (2012).

More importantly, women with varied chronic ailments have been noted to encounter a lot of barriers participating in breast screening practices (Todd & Stuifbergen 2011). Thus elderly women with chronic conditions are not likely to engage in some BC early diagnosis measures. In a qualitative investigation to identify the challenges and facilitators for BC screening among this group, and to tailor specific measures to catalyze earlier presentation; 36 elderly women with multiple sclerosis (MS) were interviewed. Despite the above obvious challenge, the study (Todd & Stuifbergen 2011), found that, there are a significant number of these women (50% -70%) who were motivated to indulge in early presentation practices. In their study, facilitators for earlier presentation and diagnosis among the elderly women with MS included; regular reminders prompt referrals by health professionals, knowledge base and sensitivity of technicians on the special needs of this cohort of women. More significantly, this category of women emphasized the adjustability and mobility of the MMG equipment as a key facilitator. In their narratives these kinds of devices can be adjusted to accommodate their mobility impairments; some of whom permanently use wheelchairs.

Summary & Conclusions

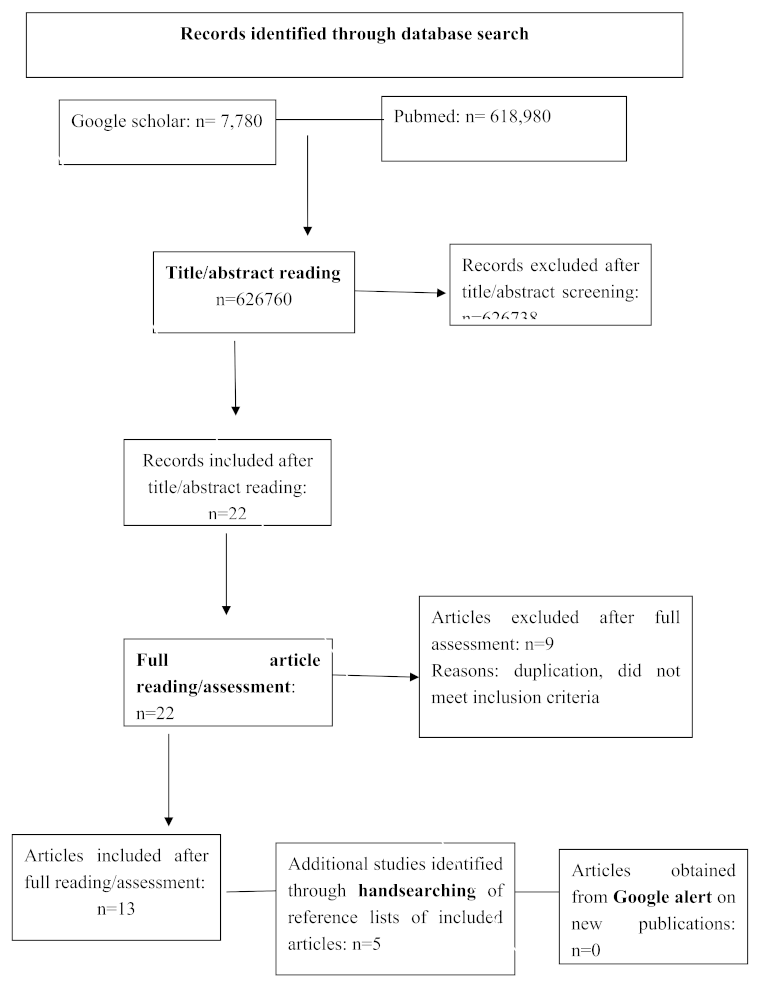

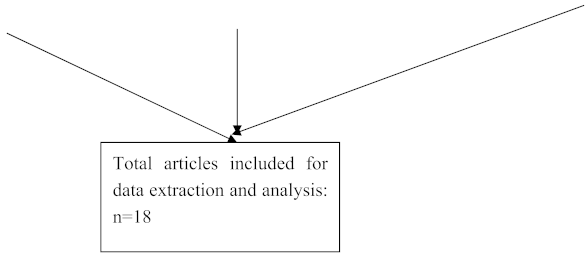

This review adopted a methodological approach to systematically synthesize evidence on the variables that are associated with earlier presentation. Given the dearth of evidence on the phenomenon, the broad objective was simplified to include many studies around the Globe.

After a thorough search, this review included studies from several countries around the Globe such as Ireland, London, Turkey, Iran, Ghana, Kenya, Ethiopia etc. The varied studies consisted of diverse methodologies, population characteristics, and sample size. It also encompassed populations of assorted age group, ethnic affiliations as well as other socio-demographic features.

In line with the specific objectives the review was done under four major topical themes as summarized below;

The single and initial most common way of early BC diagnosis is through the identification of a lump in the breast, and this could be done through BSE, CBE, and MMG. Symptoms commonly talked of included breast lump with/without pain, breast skin changes, inverted nipple, itching/burning on the breast or at the location of lymph node, swollen hands, fever, and fatigue.

In furtherance to the above, prompt help seekers mainly self-discovered their BC, and this occurred through accidental touch, after menstruation, through breastfeeding, during grooming, and while taking their bath.

After discovery of symptoms, a number of women were known to be able to establish them as abnormalities; however, they labeled them as of less concern and did not give them the needed attention. Notably, women who were termed prompt help seekers had higher seriousness perception of their symptoms. This was likened to their level of understanding and awareness, as well as periodic examination and comparison. Similarly, women who knew they were at risk for breast on account of family history, and increased incidence of BC in their localities, labeled their initial symptoms as requiring prompt attention. More so, different breast manifestations yielded different interpretations. For instance, breast pain without lump, weakness, swelling of the hands, fatigue, and fever were labeled as associated with systemic sicknesses for some women. Conversely, a mass in the breast with/without pain was perceived to be either of benign or malignant origin.

Following interpretation and labeling of symptoms, the participants generally resorted to symptom monitoring until the onset of additional and or intense symptoms. Though most women thought of benign growths, a few feared it could be malignant. These emotional reactions led the women to purposively seek clarification by selectively consulting others. Further, participants opened up to social acquaintances such as family relationships, people with prior experience of breast disease, and in some few instances health professionals. Some women also resorted to media items to better their understanding. Remarkably, prompt help seekers sort for help within one month. Last but not least, some women first communed with their creator after discovery and labeling based on their spiritual affiliations.

From the diverse characteristics of literature reviewed it is clear that, several factors contribute to prompt help seeking among women with BC symptoms around the world. Significantly, prompt help seeking was grounded on factors such as proper labeling of BC symptoms, and fear of BC diagnosis and stigma, as well as the fatalism associated with advance BC.

Also, seriousness/fatalism perception, knowledge and awareness on BC, and providing persistent educational interventions especially by healthcare providers, and on the media were noted to facilitate earlier presentation and diagnosis. More so, administration of brochures, seminars, telephone reminders, and home visits were suggested as enhancers for earlier presentation practices. Remarkably, performing breast cancer risk assessment for women was noted to facilitate earlier presentation. BC risk assessment of women has been regarded a measure to improve seriousness and fatalism perception.

In addition, social/family support and the preference of a female health professional to perform screening exercises, were found as triggers for earlier presentation. It is important to note that, women’s belief on BC must be explored, understood, refined or aligned with science to promote earlier presentation.

Moreover, higher economic status, positive attitude towards health, good health care systems, good attitude of health professionals, provision of means of transportation to the screening facilities, and the implementation of community screening programs were also emphasized as enhancers of earlier presentation.

Interestingly in some instances, participants recounted that no deliberate action was taken for BC diagnoses; however their diagnoses were accidentally made secondarily to visiting the health setting for other reasons.

In conclusion, knowledge and awareness on BC should be intensified through active health education. Emphasis should be placed on BSE, CBE, MMG, as well as the better prognosis associated with earlier presentation and treatment.

Also, researchers should consider conducting surveys to assess the BC risks for specific smaller groups. This would help tailor specific educational interventions to promote earlier presentation and treatment among the vulnerable.