1. Introduction

The western honeybee (

Apis mellifera) is a pollinating insect that has its origins in Europe and Africa, with adaptations over time in America, Asia, and Australia. This adaptation has been possible due to its exploitation for honey production and pollination of agricultural crops. Therefore, it is recognized as the most common individual pollinator species in crops worldwide [

1,

2]. They are insects that collect nectar and pollen, essential elements for the colony and for commercial use. Honey collection is carried out in colonies with a mated laying queen bee, and then collected in panels located in a machine with centrifugal force that makes the honey fall. On the other hand, pollen collection is done using pollen “traps.” These traps are placed at the entrance or under the hive and force the forager bees to pass through a metal or plastic mesh to enter the hive; In this way, loads of pollen come off their legs and fall into a collection tray [

3]. However, honeybees not only play a vital role in honey production and pollination, but act as bioindicators of environmental pollution. Due to their flight behavior, high reproduction rate, and sensitivity to toxic substances, honeybees can accumulate contaminants present in the air, water, soil, and plants during their foraging flights [

4]. In fact, bees, and their products, such as pollen and honey, are used as samplers to assess environmental quality in specific areas. Using techniques such as mass spectrometry, samples collected from hives can be analyzed for levels of heavy metals, pesticides, microplastics and other particles, providing valuable information on local contamination [

4,

15].

However, a reduction in bee colonies has been observed worldwide. This reduction is attributed to the use of pesticides, the fragmentation of habitats, climate change and the accumulation of plastics in the environment. The latter, when fragmented through photo- and thermo-oxidative degradation, produce polymeric particles known as microplastics (MP), with sizes between 1μm to 5 mm and nanoplastics (NP) with sizes <1 μm [

5,

6].

MPs are divided into two categories: primary and secondary. Primary MPs are produced with a specific size for application in the cosmetics and other commercial industries, while secondary MPs are derived from the degradation of larger plastic particles due to photochemical oxidation, hydrolysis, and mechanical forces. Furthermore, natural erosion processes such as tire wear and road particles, as well as sludge in wastewater, also contribute to the generation of secondary PM, thus representing significant sources of PM in the environment [

4,

7]. Both primary and secondary MPs are considered ubiquitous pollutants and resistant to natural degradation, in a wide variety of ecosystems, from soils, to urban, suburban, remote atmospheres, through aquatic systems, focusing on oceans where the presence has been demonstrated. of MP in seafood. However, MP contamination in terrestrial ecosystems may be greater than in aquatic systems since MPs have been found in beer, other beverages, fruits, and vegetables [

5,

7]. PM particles accumulate in ecosystems, where they influence soil processes and plant production, altering microbial composition. In this way, PM enter the food chain, acting as vectors for other contaminants [

8].

Animals are exposed to MPs through ingestion of water and food, as well as contact with contaminated air and soil. In insects, MPs can have a significant impact, due to their prevalence in the environment and the key ecosystem services they provide. Due to their size, insects are subject to greater impact from MPs than larger organisms. Pollinating insects, such as honeybees, play an important role in ecosystems, supporting the genetic diversity of angiosperm flora, making them essential for food production. Furthermore, its products, such as honey, pollen, and beeswax, are used for human consumption [

5,

8]. Therefore, MPs significantly affect the diversity of the bees' intestinal microbiome and genes related to the immune system, making them more susceptible to viral infections that damage their intestinal tissues; Therefore, it has an impact on the ecological function of pollinators, which could eventually affect human health [

4,

5].

It is important to establish techniques to identify contaminating MPs to mitigate the irreversible damage they can cause. Various studies have been carried out to analyze and identify MPs, highlighting techniques such as Raman spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) coupled to energy dispersive x-rays (EDX). and thermal analysis [

9,

10]. The Raman spectroscopy technique can detect MPs in the submicron size range, using a laser beam directed at a specific sample and producing a unique spectrum based on the chemical composition of the sample. Similarly, FTIR allows the quantitative and qualitative analysis of plastic polymers, producing unique spectra that differentiate plastics from other organic and inorganic particles, providing specific information about the composition of the polymer to determine its source or origin [

10,

11]. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) allows the identification of nanoparticles, easily differentiating organic particles from microplastics by providing high-resolution images, while SEM coupled to EDX allows microplastics to be differentiated according to their elemental composition [

10]. Thermal analysis is an alternative to spectroscopic techniques, which allows the measurement of any type of change in chemical and physical properties of substances based on their stability or thermal degradation [

11].

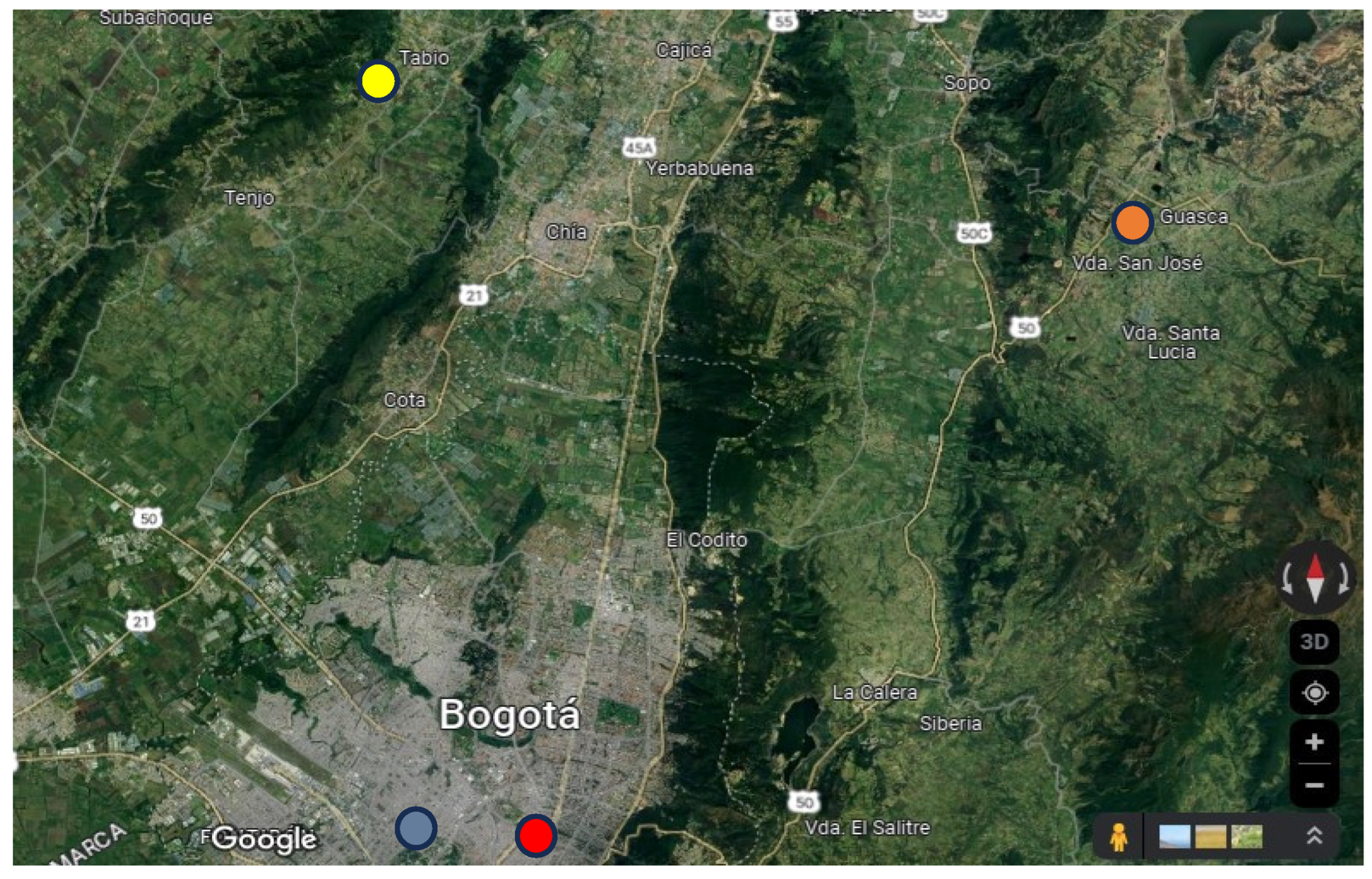

To understand the impact of MPs on the environment, it is necessary to consider their presence in living organisms and in the products derived from them. Therefore, it is important to identify the presence of PM through analytical techniques in samples collected at different sampling points. The following study covered both rural areas (Guasca and Tabio) and urban areas (Pontificia Universidad Javeriana and Universidad Nacional), considering the climatic data and environmental quality of the same month in two different years (August 2021 – August 2023).

4. Discussion

The levels of environmental contamination in the study areas are an essential factor to analyze the presence of MP found in the collected bees, pollen, and honey. According to official data, the air quality in Bogotá city has decreased when comparing the years 2021 and 2023. The annual average of PM

2.5 particulate matter in 2021 was 16 μ/mg

3, this value being higher than the annual norm of 15 μ /mg

3, so the air quality index ranged between “moderate” and “harmful for sensitive groups” during the year, considering that the main sources of pollution were industrial emissions and vehicular traffic. Meanwhile, the data until August 2023 indicate an average PM

2.5 of 22 μ/mg

3 where the environmental quality index recorded more days in the “harmful to health” category, which is attributed to the increase in vehicle emissions and conditions unfavorable climatic conditions [

22,

23]. In Cundinamarca, according to the Corporación Autónoma Regional (CAR) Monitoring Network, the Soacha, Chía and Zipaquirá stations recorded PM

10 levels above the annual norm (50 μ/mg

3) in both years [

25,

26], presenting a greater increase in 2023 and this is due to the increase in vehicular and industrial emissions [

14,

15]. Furthermore, the difference between environmental pollution levels between 2021 and 2023 is attributed to studies that confirm that the quality of the environment decreased after the COVID-19 contingency [

27,

28], which could have influenced the increase in the presence of microplastics in the samples analyzed.

Pollution levels with particulate matter can be related to the presence of MP and the foraging patterns of

A. mellifera bees by actively interacting with plants, air, soil and water close to the hive, honeybees transfer contaminants such as PM, to their products [

7]; this may explain the presence of different MP in the samples analyzed in this study.

This foraging pattern increases the probability that honeybees meet different potential sources of MP contamination in

A. mellifera, demonstrating an impact of contamination on these pollinating insects. Alma et al. (2023) demonstrated that honeybees can incorporate MP from their food sources and subsequently transferring them to honey, wax, and larvae. This implies that upon returning to the hive after foraging in contaminated areas, bees can introduce these plastic contaminants to bee products intended for human consumption [

7]. In the present study, MP were found in both honey and pollen.

It is important to mention the wide flight range that these pollinators have when obtaining resources, honey bees are collectors from central places that can search for food at certain distances from their nests, the method they use to collect food consists of a dance of wagging indicating foraging distances of up to 15 km from the nest for

A. mellifera, however average foraging ranges rarely exceed 3 km and vary between seasons or environmental settings [

20]. Honeybees actively interact with plants, air, soil, and water in the vicinity of the hive and, consequently, contaminants from these sources are transferred to the honeybees and hive products [

7]. When bees collect nectar, honeydew, pollen, water, and other plant exudates such as propolis, they encounter almost all environmental contaminants, so PM contamination will eventually be introduced into the bee colony and its bee products. [

7]. UNAL is an open field, larger and with less tree and flower density than PUJ, which would force the bees to fly farther and explore more points with anthropogenic intervention. This university is in a central area of the city surrounded by urban and industrial areas. In addition, PUJ is close to the eastern hills of the city, which would explain the greater presence of MP in the bees at UNAL.

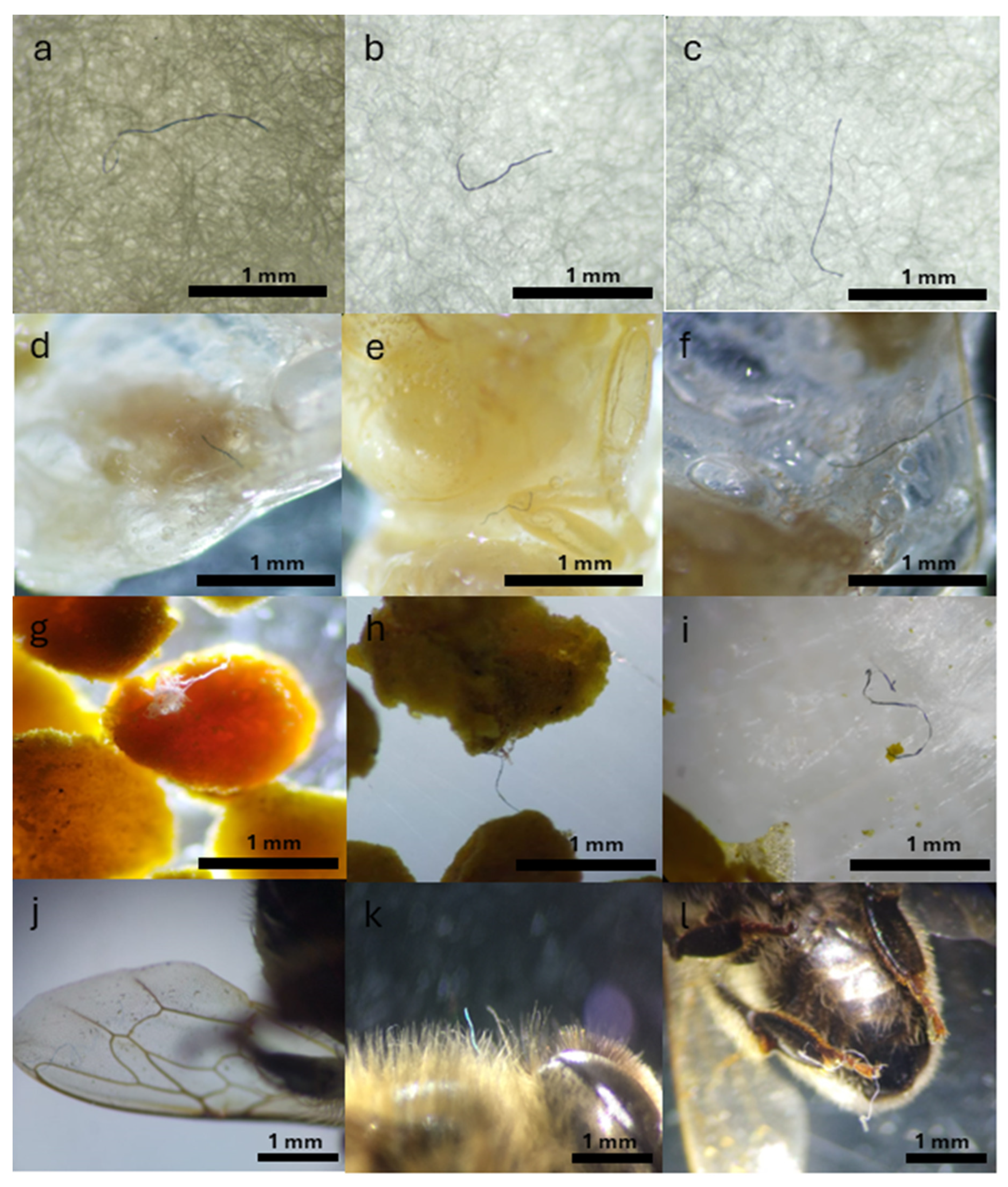

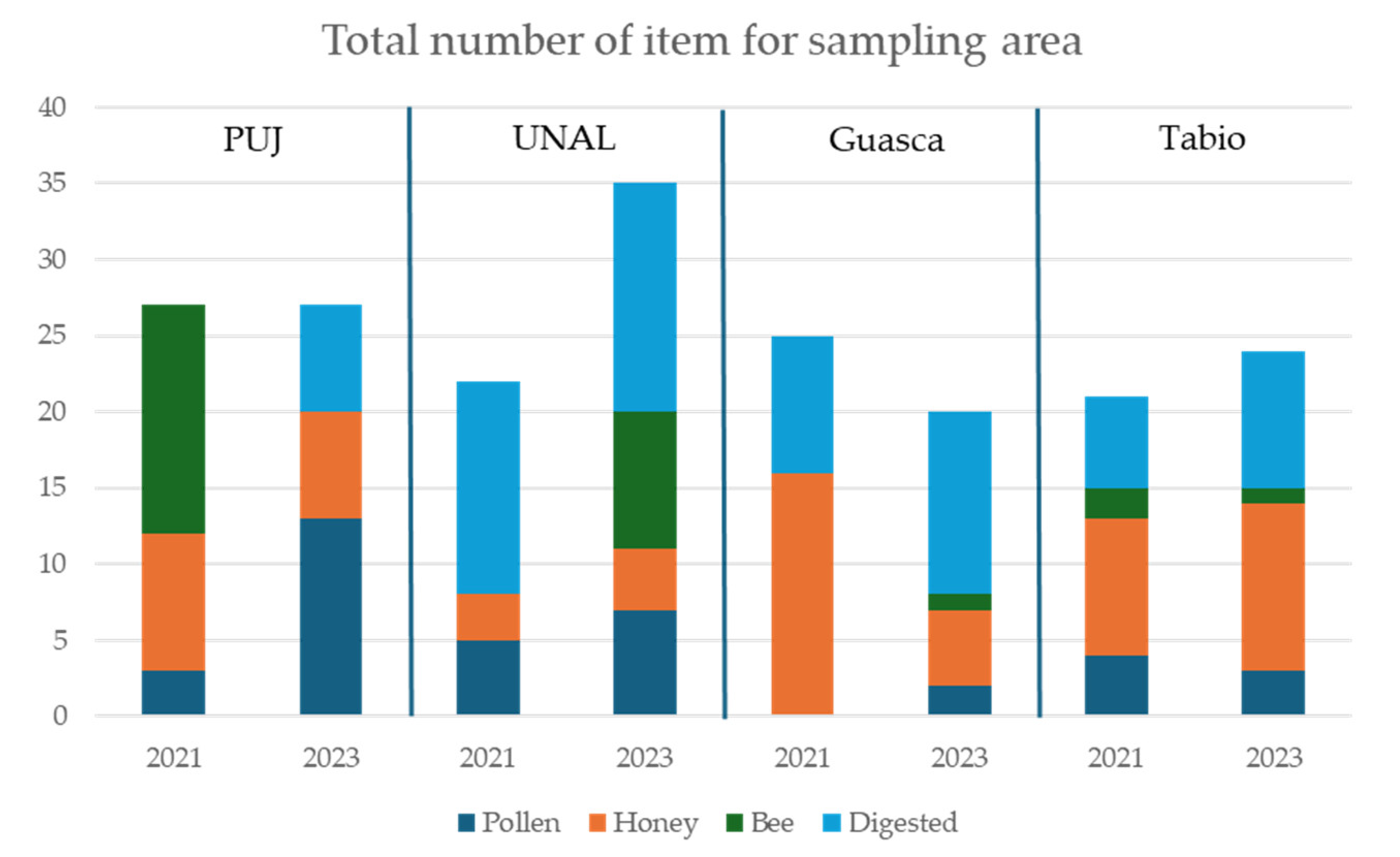

According to the data obtained, Figure 3 shows that in 2021 a greater amount of MP was found in bees in the PUJ (urban area) with 15 items, compared to the rural areas and UNAL. For the year 2023, the observation of bees under digestion with H2O2 showed that UNAL had the largest amount with 15 items, followed by Guasca (12 items), Tabio (9 items) and PUJ (7 items. Thus Likewise, the observation of the filtration used for honey after digestion with H2O2, in the year 2023 Tabio recorded the highest number of items, then the PUJ (6 items), Guasca (4 items) and UNAL (4 item). Regarding pollen, the highest amount of MP was evident in the year 2023, in the PUJ, 13 items were evident, followed by the UNAL with 7 items, Tabio 3 items and Guasca 2 items show that urban areas (UNAL and PUJ) had a higher incidence of MP than in rural areas. This may be due to factors specific to each location such as the presence of particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) that can act as vectors of MP transport for microplastics, adhering to their surface and facilitating their atmospheric dispersion, as well as point sources of pollution such as a greater concentration of population, human activity, infrastructure, the use of chemical products and the lack of vegetation, in addition to the conditions climatic.

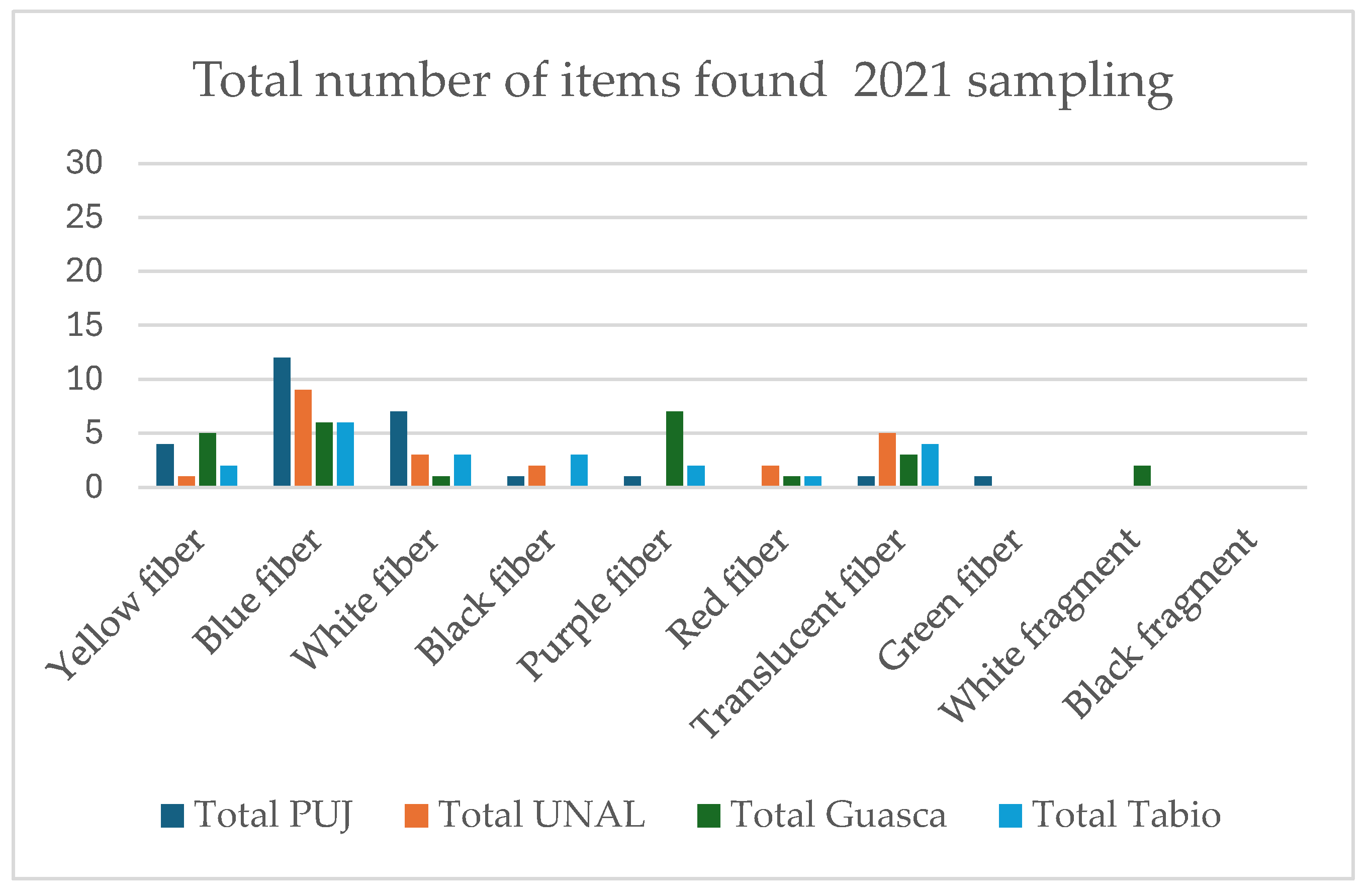

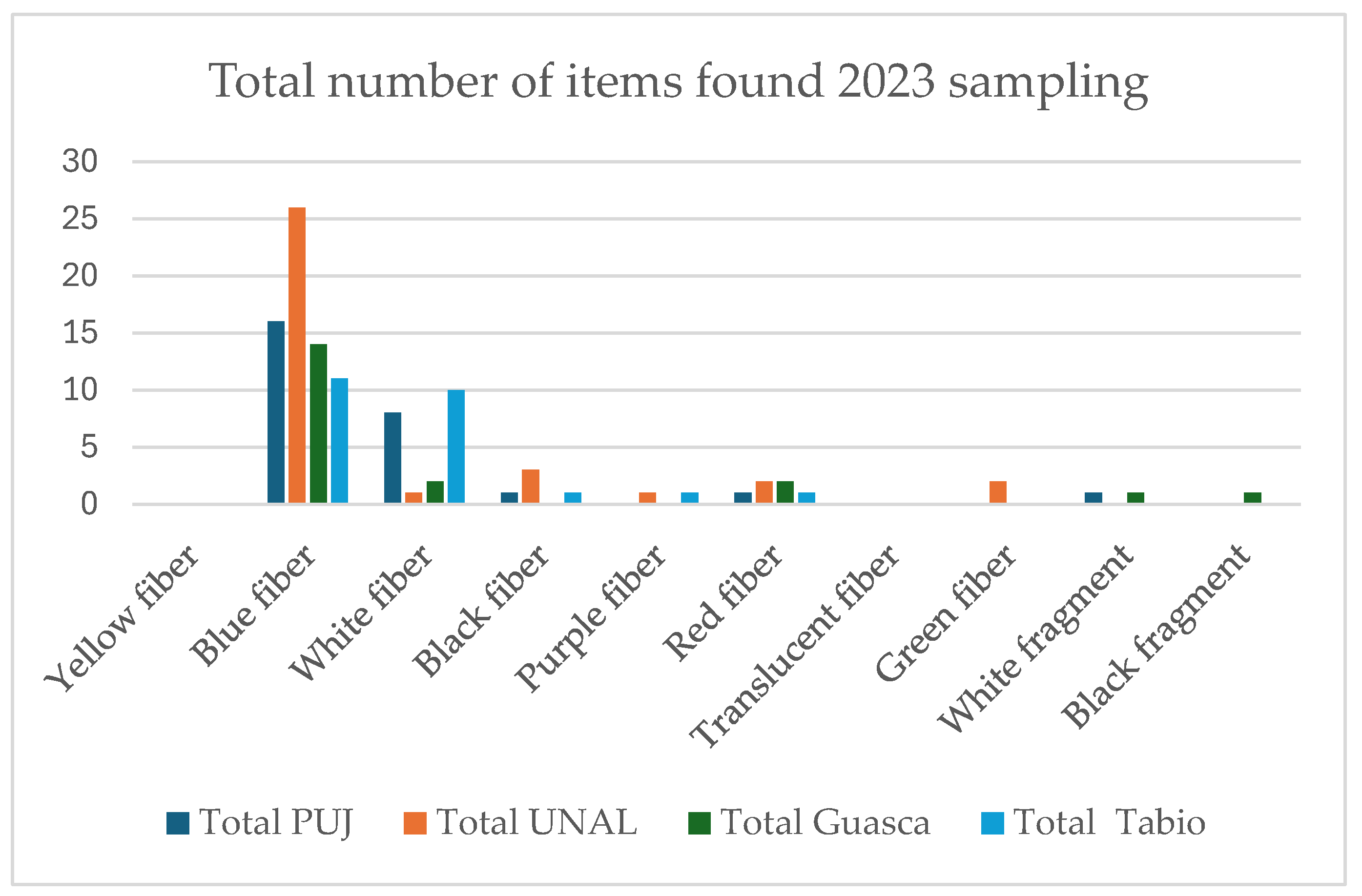

According to the number of fibers found per color, blue fibers were the most frequent type of PM in bees, pollen, and honey, both in 2021 and 2023 (Figure 4 and Figure 5). This predominance is linked to the preference of

A. mellifera bees for shades in the visual range between 300 and 700 nm, with maximum peaks in ultraviolet (344 nm), blue (438 nm) and green (560 nm) [

29]. These wavelengths correspond to the vibrant colors that bees prefer during pollination and collecting nectar and pollen. Therefore, the high prevalence of blue fibers in UNAL and PUJ urban areas could be due to several factors. Firstly, the green areas and gardens present in these places that could be contaminated due to their location. In these areas, vehicle pollution, garbage accumulation, and the deposition of plastic or synthetic materials could contribute to the presence of fibers [38]. On the other hand, the preference of bees for flowers of bright colors such as blue, yellow, red, and green, during foraging could influence their exposure to these fibers since they could transport them from the gardens and green areas present in that environment to the hive, which may explain its high prevalence in these areas. The translucent fibers could be related to proteins present in bees, while fibers of other colors are attributed to the incorporation of MP by bees during foraging. These notable differences in the types of MP found between the rural areas (Tabio and Guasca) and the urban areas sampled could be related to the presence of urban settlements within the feeding range of worker bees and the ease with which MP They can be dissipated by wind [

7]. However, it has been shown that transparent, white, and black MP fibers are the most abundant in sediments and freshwater [

20]. The prevalence of this type of fibers or fragments found could indicate the presence of sediments close to the sampling points, considering that the rural area possibly has a greater probability of nearby sediments due to its greater number of green areas, which, could also be contaminated due to the urbanization that has occurred in these areas over time [

31]. However, blue MP and shades close to that color should not be ignored in rural areas close to the apiaries studied. Various polypropylene (PP) or polyethylene (PE) type plastics were observed in Guasca and Tabio used as enclosures (walls) of farms (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Plastic enclosures observed in Tabio (a) and Guasca (b) farms, close to the apiaries studied.

Figure 6.

Plastic enclosures observed in Tabio (a) and Guasca (b) farms, close to the apiaries studied.

MPs found in bees and their bee products revealed the presence of fibers and fragments, including fibers of different colors such as blue, red, black, white, and translucent, as well as black and white but not in size, shape and, probably, not in polymeric composition. Some colored fibers could, with low probability, come from primary sources such as synthetic fabrics, clothing or ropes, while the blue, green, grey or black fragments and fibers could be remains of the degradation of larger plastics in the environment, such as those used as dividing nets, becoming secondary MP (Figure 6), which significantly affects their behavior and environmental impact [

5]. In addition, some fibers may also have been formed by the fragmentation of larger plastics exposed to environmental processes such as UV-B rays [

20,

21,

31]. Both primary and secondary MP are ubiquitous and persistent pollutants found in urban, suburban, and rural atmospheres far from their sources, indicating possible long-distance atmospheric transport [

7]. Some of the polymers commonly found in MP include PP, PE, polystyrene (PS), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyurethane (PU) and terephthalate (PET) [

28]. In this study, an attempt was made to determine the chemical composition of the MP found, but due to their size, the microscope coupled to the infrared spectrometer did not detect them.

Understanding the composition of MPs is essential to evaluate their persistence, distribution, transport and impacts on ecosystems, human and animal health. The confirmed presence of primary MPs and secondary effects in these reservoirs highlights the importance of continuing to investigate the sources, exposure routes and effects of these contaminating particles.

MPs found in bees, pollen, and honey, may represent a risk to the health and well-being of these pollinating insects. Fibers and plastic fragments could cause damage to the digestive system of bees, as well as alterations in their behavior and foraging capacity [

7]. Furthermore, the presence of MP in pollen and honey could affect the nutritional quality of these products both for bees and for human consumption.