1. Introduction

The emergence of a new form of transmitting marketing content—influencer marketing—seems to have caused confusion and irrationality in marketing activities. This form of marketing has been observed to be a highly promising form of influencing consumers, leading to the cooperation with influences often without reliable analysis of potential profits and losses and long-term strategy. Influencer marketing has predominantly been engaged through a process of trial and error without in-depth insight into how social media influencers (SMI) can be strategically deployed as a distinct tool in an overall marketing mix (Ye et al., 2021).

From a marketing perspective, individuals in the virtual space are recipients of advertising stimuli, and their responses are closely monitored in accordance with expectations. However, in essence, advertising cannot fulfill individuals’ informational needs on the internet. Instead, advertising is only delivered on occasion. While motivations for engaging in virtual life may vary, from the advertiser’s perspective, content that attracts attention is an effective “information good.” On the internet, capturing attention is the primary goal for advertisers.

Referencing Simon’s seminal work (Simon, 1971), we engage an economic theory that provides the basics for modeling the internet phenomena of attention economics. Decades ago, Simon noticed that the prevailing issue of contemporary times was not a lack of information, which can make rational decisions impossible, but instead the excess of information. When people are overloaded with information, their attention becomes a valuable resource.

Influencer marketing refers to marketing in which individuals who have a social media following and are seen as experts or opinion leaders in a particular niche promote a brand’s products or services to their followers. Influencers can sway their followers’ purchasing decisions due to their perceived credibility, authenticity, and authority. Influencer marketing is a hybrid combination of marketing tools such as word-of-mouth marketing and digital advertising (Abidin, 2016). This approach appears to be an effective marketing tool as it is often not perceived by consumers as advertising and guarantees a wide reach to highly engaged audiences (Ye et al., 2021). Previous research has demonstrated that influencer marketing is a tool that is increasingly able to exert a strategic influence on recipients by building images as authentic and credible people in social media (e.g., Trivedi and Sama, 2020)

Companies have been increasing investments in social media. Kirkpatrick (2016) showed that the return on investment can be up to 11 times higher than that of other forms of advertising. The general success achieved by firms that have engaged in influencer marketing seems to flow across future planning. According to the report entitled “The State of Influencer Marketing” (Influencer Marketing Hub, 2024), more than 85% of respondents intended to dedicate a budget to influencer marketing in 2024. Not all that long ago, Instagram was synonymous with influencer marketing. Until 2003, Instagram was the network of choice for such marketing campaigns. In 2022, it was used by almost 80% of our respondents for influencer marketing. It remains popular; however, in 2024 only 46.7% of brands used Instagram when deciding to participate in influencer marketing, dropping to second place. Now 68.8% of those respondents who engage in influencer marketing include TikTok in the channels they use, 85% of respondents perceive influencer marketing to be an effective form of marketing, and 60% of those who budget for influencer marketing intend to increase their influencer marketing budget over next year.

As of January 2024, almost 32% of global Instagram audiences were between 18 and 24 years of age (Generation Z) and 30.6% of users were between 25 and 34 years of age (Millennials). Overall, 16% of users belonged to the 35 to 44 age group (Statista, 2024).

One of the most difficult decisions of influencer marketing is identifying the right opinion leader for a particular marketing campaign (Araujo et al., 2017). Emerging research on the topic has yet provided conclusive results on whether, and if so, how marketers can identify influential users who can accelerate the diffusion of brand content. Although researchers have suggested that brands should identify and target influential individuals on social media (Bughin et al., 2010), defining the concept of influential users and how to identify them has not been clarified. Certainly, the aspects that should be considered when entering into cooperation with a given influencer include matching the person to the brand image, their reach, and their credibility.

This study is exploratory in nature and aims to answer the following research questions:

Question 1: Are influencers able to influence social media users’ purchase decisions?

Question 2: Do specific social media user characteristics promote the effectiveness of advertising messages related to influencer activity?

Question 3: What aspects of marketing collaboration with influencers are key to driving consumers’ purchase intent?

Our empirical analysis is based on data collected conducting an online survey using Google Forms between July 10, 2022 and July 31, 2022. The participants of the survey were residents of Poland of various ages and diverse characteristics, and 513 questionnaires were completed. Among other things, we inquired about respondents’ perceptions of the term “influencer” and frequency of social media use. The survey also raised questions concerning respondents’ purchase intentions under the influence of SMI and evaluation of selected advertising collaborations. The aspect of marking collaborations was also covered in the survey.

Using a nonhierarchical k-means clustering method, we grouped Instagram users into three clusters based on similarities. Respondents in the first cluster spent a considerable amount of time on Instagram, followed many accounts, and actively engaged with influencer posts, but did not particularly exhibit purchase intent after seeing advertisements. Cluster 2 included individuals who frequently liked influencers’ posts, followed an average of over 30 SMIs on Instagram, and spent about an hour browsing the app per day. These respondents noted that they had purchased several recommended products. Individuals in the third cluster sparingly allocated time and attention to using the app and had a selective approach to content. After determining the main sociodemographic characteristics of individuals in the three groups we sought additional insights.

We used econometric analysis to identify the characteristics that make an individual susceptible to influencer recommendations. When interpreting logistic regression estimates, we distinguish a certain set of characteristics among social media users that increase the effectiveness of influencer messaging, which is measured as purchases made based on recommendations. These users are generally young women with relatively good financial status who use Instagram. For advertisers, this may be valuable information regarding the strategic targets of specific marketing campaigns.

We also employed a random forest (RF) approach, which is efficient, interpretable, and nonparametric for various types of datasets (Ali et al., 2012) to analyze the characteristics that influenced purchases based on influencers’ recommendations. Referencing the resulting feature importance chart, we created a ranking of variable importance, placing characteristics such as age, influencer perception, number of well-known SMIs, and financial condition at the top of the list. Using partial dependence plots for the most significant explanatory variables, we then assessed how different values of these variables affected purchases based on SMI recommendations. To determine what influences SMI campaigns’ effectiveness, we also investigated the impact of selected SMI’s advertising collaborations on consumers’ purchase intent employing ordered logit models. Influencer marketing is a relatively immature method used in promotional marketing, and further in-depth research on its effectiveness and evolution is essential.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Next section reviews related empirical literature. Then we describe the data and present the empirical results. The last section concludes.

2. Literature Review

In contemporary times, individuals are constantly confronted with the imperative of decision making. Connecting the farthest corners of the globe, the internet amplifies an array of possibilities, immersing individuals in an ever-expanding realm of information. User attention, which is manifested through clicks, likes, and online reactions, has emerged as a novel currency that is fervently pursued by content providers. In their pursuit, providers meticulously design advertising campaigns. Consequently, the finite resource of attention has become a subject of competition.

2.1. The Attention Economy

Two main streams of research have examined the economics of attention in contemporary economic theory. The first of these is Shannon’s mathematical theory of communication, which was proposed in 1948, arguing that insufficient audience attention leads to asymmetry with information providers. Information overload occurs when individuals struggle to understand an issue and make effective decisions when facing too much information. The second research stream has drawn from Simon and the theory of bounded rationality, finding that selective attention can lead individuals to overlook significant patterns, make erroneous forecasts, and hold false beliefs about relationships between variables (Gabaix et al., 2006). The attention economy presents a novel marketing perspective that attributes value to content based on the ability to capture attention in a media-filled, information-rich world (Fairchild, 2007).

Instagram is a platform where an individual can become a star if they understand the app’s algorithm correctly and can skillfully attract viewers’ attention. Through strategic profile management, microcelebrities can reach their followers by revealing personal information to build connections and attachment (Marwick, 2015). Individuals increasingly seek to establish personal brands on digital platforms that have established organized online attention economies that connect attention seekers and audiences. Insights into how influencers attract and retain engaged attention and interactions on such platforms remain limited (Smith and Fischer, 2021).

2.2. Choice Paradox

In the 21st century, in a world of multiplied possibilities, people experience the paradox of choice every day. This refers to the phenomenon in which having more options to choose from can lead to difficulties in making decisions and decrease satisfaction with the choice made. Societies focus on maximizing individual wellbeing by increasing personal freedom and expanding the pool of life choices that each person can make. The question arises: Does facing choices in every possible situation actually improve our wellbeing? Studies have reinforced the claim that, unfortunately, it does not (Dar-Nimrod et al., 2009). When making a decision, people often consider compromises and opportunity costs. The decision making process is complex and mentally taxing as decision makers are compelled to analyze alternative options, consider the consequences of choosing each option, and face uncertainty. The paradox of choice in the attention economy appears to be even more pronounced. Every day, we are bombarded with information presented from various perspectives as we enter the online realm. Everyone is trying to capture our attention. As a result, faced with familiar budget constraints, individuals spend hours seeking opinions, advice, and additional options. Researchers have demonstrated that increasing the options available raises the cost of decision making (Granka et al., 2004) and may result in purchase abandonment (Iyengar and Lepper, 2000).

2.3. Social Media Influencers

Online advisors that are sponsored by brands seeking to attract consumers can aid users’ decision making. A growing phenomenon of a newly created profession—the influencer—emerged at the start of the social media era. Thousands of accounts were created by people who sought to be popular in the digital space and share recommendations with followers. Thousands of marketing agencies were also set up to connect brands with influencers. An increasing number of specialists are now vying for social media users’ attention online. Due to information overload, when in doubt concerning purchases, SMI followers search the opinions of leaders that specialize in a given field to check their recommendations. If the recommendations prove to be accurate, the probability of continuing to rely on SMI support for decisions increases (Al-Harbi and Badawi, 2021). Influencers are referred to as human decision support systems whose recommendations are intended to reduce consumers’ time and effort (Bawack and Bonhoure, 2023).

In summary, influencer marketing can be considered a mechanism that drives consumerism, while it can also provide valuable advice that guides users toward specific products and relieves the effects of the paradox of choice.

2.4. Influencer Marketing in Empirical Literature

The research directly related to influencers has been limited. Nonetheless, this research area can be connected to studies regarding the credibility of messaging and the establishment of trust in virtual relationships in general.

Trust is an implicit set of beliefs that the other party will refrain from opportunistic behavior and will not take advantage of the situation (Ridings et al., 2002), and is widely considered to be the cornerstone of all communication, particularly on the internet. Warner-Søderholm et al. (2018) investigated the extent to which individuals trust social media, exploring how users’ perceptions of trust varied based on factors such as gender, age, and the duration of social media use. The authors underscored the exponential growth of social media use in the past decade, with hundreds of thousands of platforms presenting diverse perspectives on various subjects. Consequently, discerning accurate and trustworthy information amid this vast landscape can be challenging. The research revealed that only 20% of respondents unequivocally trust the news they encounter on social media. Moreover, women and younger users were found to have higher expectations regarding integrity, placing greater trust in others and anticipating empathy and goodwill from them. The level of trust in content on the internet was lowest among the group of older men who did not use social media often.

SMIs have steadily gained significance as brand endorsers by cultivating strong parasocial relationships with followers. Breves et al. (2021) conducted an analysis on the impact of SMIs on their followers, finding that the status of a follower significantly influences the strength of parasocial relationships, perceptions of source credibility, and evaluations of sponsored Instagram posts. Moreover, followers who established strong bonds with SMIs reported heightened purchase intent and brand evaluations, particularly when posts included advertising disclosures.

Hermanda et al. (2019) examined how SMIs impact brand image and cosmetic consumers’ self-concept and purchase intentions. SMIs have emerged as a significant source of information about cosmetic products for audiences on various social media platforms. Using structural equation modeling, the authors determined that influencers did not directly influence consumers’ purchase intent. Instead, SMIs had a significant indirect positive effect through the mediating variable of brand image. Additionally, following customer segmentation, the authors observed that cosmetic products are particularly favored by professionally active women aged 20 to 30 with higher education levels.

Lookadoo and Wong (2019) investigated the extent to which parasocial relationships between celebrities and social media users impact the effectiveness of celebrity endorsements on social media for various products. The authors found that celebrity credibility and message consistency did not significantly affect product purchase intent; however, these factors did have a notable impact on consumers’ attitudes toward products, particularly when the endorsements came from celebrities with whom they had strong parasocial relationships. Konstantopoulou et al. (2018) noted that the issue of perceiving influencers as authentic is particularly prominent in the cosmetics industry, and Bawack and Bonhoure (2023) demonstrated that credibility is key to success in terms of purchase intent.

Nasir et al. (2021) sought to identify consumer segments concerning the factors that can predict purchase intentions. Using cluster analysis, the authors grouped consumers into susceptible, dispassionate, and impervious segments. Consumers in the susceptible segment were found to be more predisposed to influence, exhibited higher tendencies toward impulse buying, and demonstrated a stronger inclination toward social networks compared with the other groups. The authors determined that consumers’ purchase intent is influenced by perceived relevance, susceptibility to persuasion, self-confidence, and engagement in social networks.

A clear indication that a post is sponsored can significantly influence consumers’ perception and purchase intent. Weismueller et al. (2020) investigated this topic in research on SMIs, revealing several key findings. First, the disclosure of collaboration positively affects the influencer’s attractiveness. Second, the SMI’s credibility, which was measured in terms of attractiveness, level of trust, and expertise, positively influences consumers’ purchase intent. Additionally, the authors found that a higher number of followers on Instagram was correlated with higher SMI scores in terms of attractiveness, trustworthiness, and purchase intent.

Simply having a large number of followers does not always translate into an effective and positively perceived product marketing campaign. De Veirman et al. (2017) found that influencers with extensive reach might not be an optimal choice for promoting niche or unique brands because such brands’ association with a typical mainstream SMI could disrupt consumers’ perception of the brand’s positioning. The researchers noted a negative impact when influencers with excessively large following promote niche products. Using a mass-reaching influencer for such promotions can dilute the product’s uniqueness.

Labeling paid advertising collaborations is considered to be a legal obligation for influencers; however, there is a fine line between recommending a product out of pure goodwill and receiving associated financial or material support. Mixing sponsored materials with unpaid ones, which is known as native advertising, complicates the audience’s ability to differentiate between paid and unpaid content (Campbell and Grimm, 2019). Many SMIs disregard this legal requirement by inadequately disclosing sponsored content. Kay et al. (2020) assessed the impact of labeling paid materials on micro- and macro-influencers’ effectiveness, finding that micro-influencers who labeled sponsored content achieved the highest score when estimating purchase intent. Previous research has suggested that straightforward disclosure messages such as “this is a sponsored post” can diminish the persuasive power of advertising (Hwang, Jeong, 2016).

We formulated the study’s research questions based on our literature review. A fundamental research question is whether SMIs influence social media users’ purchasing decisions. The second research question asks, do specific social media user characteristics make users more receptive to influencers and more likely to make purchasing decisions influenced by SMIs? Similar questions have been posed by other researchers in their work; for instance, Nasir et al. (2021) distinguished segments of consumers using social media platforms in relation to their perceptions of influencers or advertisements. Hermanda, Sumarwan, and Tinaprillia (2019) confirmed that beauty products from SMI referrals are most likely to be purchased by active women with higher education in the 20–30 age range.

The third research question seeks to examine the aspects of marketing collaborations with influencers that are key in stimulating consumers’ purchase intent. Bawack and Bonhoure (2023) found that the greatest effect on purchase intent is observed for consumers’ corresponding attitude toward the product/brand, and that the SMI’s credibility in the eyes of the audience significantly affects purchase intent. Hermanda, Sumarwan, and Tinaprillia (2019) demonstrated that SMI’s action primarily affects brand image and consumer awareness of a product.

3. Data and Methods

As noted previously, the data for this study were collected using an online survey that was conducted using Google Forms between July 10, 2022 and July 31, 2022. The survey participants were residents of Poland of various ages and diverse characteristics. Overall, 513 questionnaires were completed, including 320 women (62.4%) and 193 men (37.6%). Among the respondents, 208 lived in large cities (40.5%), and the rest were from towns (39.8%) and villages (19.7%). The sample was dominated by individuals with higher education (69.4%). In terms of age, the largest group was respondents aged 24–29 (48.3%). This study also considered respondents’ employment status, and the majority of the respondents were employed full time (57.3%). From a financial perspective, each participant had the opportunity to choose one of seven categories. The largest group of respondents classified their financial condition as good, indicating that they have enough to meet their needs and save for the future (with savings at the level of affording vacations).

Table 1 presents the respondents’ demographic and financial characteristics.

Two aspects of our survey merit attention. The first concerns the frequency of social media usage, and the second refers to influencers’ recognition within the Polish Instagram TOP10. The primary aim was to identify the prevailing platforms and users’ time spent on them. Almost 99% of participants reported using social media platforms. Facebook emerged as the most common, followed by YouTube. Instagram came in third place, with nearly 80% of respondents engaging with the platform. We observed a negative correlation between age and familiarity with influencers. The youngest age group, with individuals up to 23 years old, indicated that they had knowledge of an average of eight influencers, whereas respondents aged 30 and above knew an average of only three influencers out of 10.

We also inquired about respondents’ perceptions of the term influencer. The results indicated that 43% of respondents held a neutral attitude toward the term, 16% expressed positive associations and 4% indicated very positive associations, and 36% of respondents reported negative feelings associated with the term. Among them, 25% associated the term negatively, and 11% described their associations as very negative. Interestingly, across all age groups, women exhibited more favorable perception of SMIs.

This The survey also raised questions about purchase intent under the influence of SMIs (

Table 2). The largest group (36.8%) indicated that they had investigated a product several times (less than 5) after encountering it on social media. Slightly fewer individuals (27.5%) indicated that they made purchasing decisions several times (less than 5) based on social media recommendations. Nearly 10% indicated that they had repeatedly made purchases based on SMI’s endorsement.

Among the respondents, 25.6% stated that social media posts never prompted them to search for information about products, and 37.6% indicated that they had never made a purchase based on social media recommendations. Purchases were most often made by women in good financial condition. Across all financial demographics, women tended to make more purchases of influencer-recommended products compared to men.

Respondents were asked whether they paid attention to influencers’ disclosures of advertising collaborations, and 24% of the respondents admitted to not paying attention to it at all. The same number of respondents indicated that they had noticed such disclosures with some of the influencers they follow, while 29% indicated that they had observed proper disclosures made by the majority of SMI’s content.

The respondents were then asked to rate marking collaborations in terms of several considerations on a Likert scale. The results revealed diverse perspectives regarding the significance of marking collaborations. A significant proportion of respondents (42%) fully agreed with the statement that proper acknowledgment of collaborations fosters transparency. Only 6% of participants indicated that disclosure encourages purchasing decisions, while the largest group of the respondents did not have an opinion on the matter. Furthermore, 36% of the respondents disagreed with a statement suggesting that labeling collaborations is unnecessary, which is a signal of consumers’ need to receive reliable information from influencers.

The participants also responded to questions concerning Instagram, provided that they had an account (412 of the 513 respondents). On average, respondents reported spending around 40 minutes on Instagram per day, while half of the users dedicated between 15 and 60 minutes to the application each day.

Authors When questioned about responses to influencer posts, over 40% of the respondents indicated that they react occasionally, particularly when a post caught their attention. Nearly 5% admitted to consistently liking most posts, while 9% indicated that they never engaged with influencer content. The number of influencers that respondents followed on Instagram varied significantly (

Table 3). Almost 50% of the respondents purchased a product recommended by an influencer on Instagram at least once, and this trend was most prevalent in the beauty and sports industries.

In the final part of the survey, the respondents were asked to evaluate examples of advertising collaborations of influencers on Instagram, presenting influencers from various age groups and industries. Mateusz Trąbka, known for his presence on YouTube, was chosen to represent the under 20 age group. Natalia Szroeder, who is recognized in the music industry, was selected to represent the 20–30 age group. Robert Lewandowski, a prominent figure in sports, was chosen to represent the 30–40 age group. Finally, Martyna Wojciechowska, known for her travel content, was selected to represent the 40+ age group. Respondents regarded Martyna Wojciechowska and Robert Lewandowski as the most positively perceived and authentic influencers. In an experiment involving sample campaigns, 19% of participants expressed a high likelihood of purchasing (with a 4 or 5 rating on a Likert scale of 1–5) for the campaign with Robert Lewandowski, and 24% for the campaign with Natalia Szroeder. For collaborations involving Mateusz Trąbka, nearly 20% of respondents showed a high level of purchase intent and 40% in the campaign with Martyna Wojciechowska.

Even at this preliminary stage, based on the initial data analysis, it is evident that influencers have the capacity to influence social media users’ purchasing decisions.

4. Results

This section explores the acquired data to obtain answers to our research questions.

4.1. Instagram Users: Cluster Analysis

We used a nonhierarchical k-means clustering method based on the variables described in

Table 3 to group Instagram users into k clusters based on similarities, as shown in

Table 4.

To select the optimal number of clusters, we applied the elbow method, Silhouette method, Gap statistic, and Akaike information criterion (Kodinariya and Makwana, 2013). Three clusters were created, with the first cluster containing 109 observations, the second one 186, and the third one 117.

The first cluster included 62 females and 47 males, predominantly falling in the age group up to 29 years (94%); 24% were residents of rural areas, and 34% resided in large cities with over 500,000 inhabitants. Only 46% of the group indicated that they had higher education, 42% had secondary education, and 12% had primary education. The largest number of individuals were students, at 57%, followed by full-time employees, at 32%. Concerning financial condition, Cluster 1 is a middle-income group, with a significant representation of individuals who lived frugally, managing to meet their basic needs without saving for the future. This group can be described as young residents of smaller towns, with average financial conditions. Instagram users in Cluster 1 also reported a relatively high frequency of liking posts, most of them followed at least 50 influencer profiles, and their time spent online ranged from 20 to 60 minutes per day. They expressed moderate interest in making purchases, and while the majority have looked for more information about a product, they rarely or never made purchases recommended by influencers. In summary, this group could be called “resilient but closely watching” as they spent a considerable amount of time on Instagram, followed many accounts, and actively engaged with influencer posts, but they did not exhibit purchase intent after seeing advertisements. The reason for this could be their young age (lack of full independence in making purchases) and/or poorer financial conditions.

The majority in Cluster 2 were women (82%), and 60% of the group were 24–29 years old. Nearly half (44%) were residents of large cities with over 500,000 inhabitants, and 77% reported having higher education. The majority of the group (62%) were full-time employees. The largest proportion of the group (35%) reported good financial conditions, with savings equivalent to a vacation trip. Descriptively, this group can be characterized as young but mature women from larger cities, with higher education and very good financial condition. Cluster 2 included individuals who frequently liked influencer posts, followed an average of over 30 SMIs on Instagram, and spent about an hour browsing the app per day. These individuals indicated that they have often shown interest in products recommended by influencers and have purchased such products several times. This cluster can be described as active and reactive individuals who are susceptible to SMI’s actions and persuasion. The reason for this behavioral style may be high financial independence and limited time for decision making, including higher susceptibility to recommendations, which shortened the time spent searching for the right product.

Men predominated Cluster 3, accounting for 56% of the group, and 32% of this cluster included individuals over 30 years old, representing the largest representation of the generation born before the smartphone era in the entire study. Individuals aged 24–29 years made up the majority of the group (42%), and 39% of this cluster resided in cities with over 500,000 inhabitants. The majority of the group (67%) had higher education, and 58% were full-time employees. This cluster can be described as being in very good financial condition, as many respondents reported savings that allowed them to purchase a new car (33%), and slightly fewer (25%) could finance a vacation trip. Cluster 3 represents individuals who liked and reacted to Instagram influencer posts less frequently than others, spent only a few minutes in the app each day, and followed only a few select individuals. They rarely showed interest in advertised products and seldom made purchases based on Instagram recommendations. This group can be described as “Instagram regulars”; individuals who sparingly allocated time and attention to using the app with a selective approach to content.

4.2. Characteristics That Make an Individual Susceptible to Influencer Recommendations: Logistic Regression

In this section, we present the results of the classification obtained using logistic regression. The model’s quality was evaluated based on the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) statistic. The dependent variable was assigned a value of 1 when the surveyed person indicated that they had ever purchased a product or service recommended by an influencer and was 0 otherwise. The explanatory variables used in the model included age, gender, place of residence (scale of 1–5), education (scale of 1–3), employment status, financial condition measured (scale of 1–7), assessment of associations related to the word “influencer” (scale of 1–5), the number of known SMIs from the presented TOP 10 list, binary variables controlling for the use of specific online platforms, and a variable measuring how many minutes per day the respondent spent on social media.

The variables with statistical significance at the 5% significance level included age, gender, financial condition, influencer rating, Instagram usage, LinkedIn usage, and Twitter usage. Additionally, education and employment status were relevant at a 10% significance level.

Therefore, this study revealed a certain set of characteristics among social media users that impact the increased effectiveness of SMI messaging, which we measured as purchases based on recommendations. These users were identified as young women with relatively good financial status who used Instagram. This may be valuable information for advertisers for developing strategic target marketing campaigns.

Table 5.

Logistic regression estimates.

Table 5.

Logistic regression estimates.

| Dependent variable: purchase based on SMI recommendations (binary outcome) |

|---|

| |

Coef |

S.E. |

Wald Z |

Pr( > |Z|) |

| Age |

−0.0377 |

0.0153 |

−2.47 |

0.0136 |

| Gender (0 - Woman, 1 - Man) |

−1.1766 |

0.2304 |

−5.11 |

0.0001 |

| Place of living (scale) |

0.0678 |

0.0722 |

0.94 |

0.3475 |

| Education (scale) |

0.3985 |

0.2279 |

1.75 |

0.0804 |

| Employment status: Entrepreneur |

−1.0090 |

1.0192 |

−0.99 |

0.3222 |

| Employment status: Student |

−1.7845 |

0.9815 |

−1.82 |

0.0691 |

|

Employment status:Full-time employment

|

−1.1268 |

0.9612 |

−1.17 |

0.2411 |

| Financial condition (scale) |

0.2191 |

0.0908 |

2.41 |

0.0158 |

| Influencer perception (scale) |

0.5604 |

0.1169 |

4.79 |

0.0001 |

| Number of known SMIs |

0.0642 |

0.0455 |

1.41 |

0.1585 |

| Facebook |

−0.5006 |

0.3880 |

−1.29 |

0.1970 |

| Instagram |

1.1874 |

0.3034 |

3.91 |

0.0001 |

| YouTube |

0.1575 |

0.3056 |

0.52 |

0.6063 |

| TikTok |

−0.5723 |

0.2447 |

−2.34 |

0.0193 |

| LinkedIn |

−0.2957 |

0.2471 |

−1.20 |

0.2314 |

| Daily time on SM |

0.0017 |

0.0012 |

1.45 |

0.1471 |

| Constant |

−2.0172 |

1.4998 |

−1.34 |

0.1786 |

| Number of observations |

|

|

513 |

| LR chi2 (16) |

|

|

136.18 |

| Prob > chi2 |

|

|

0.000*** |

| Pseudo R2 |

|

|

0.1915 |

| AUC |

|

|

0.7919 |

| Sensitivity |

|

|

73.83% |

| Specificity |

|

|

70.04% |

4.3. Random Forest

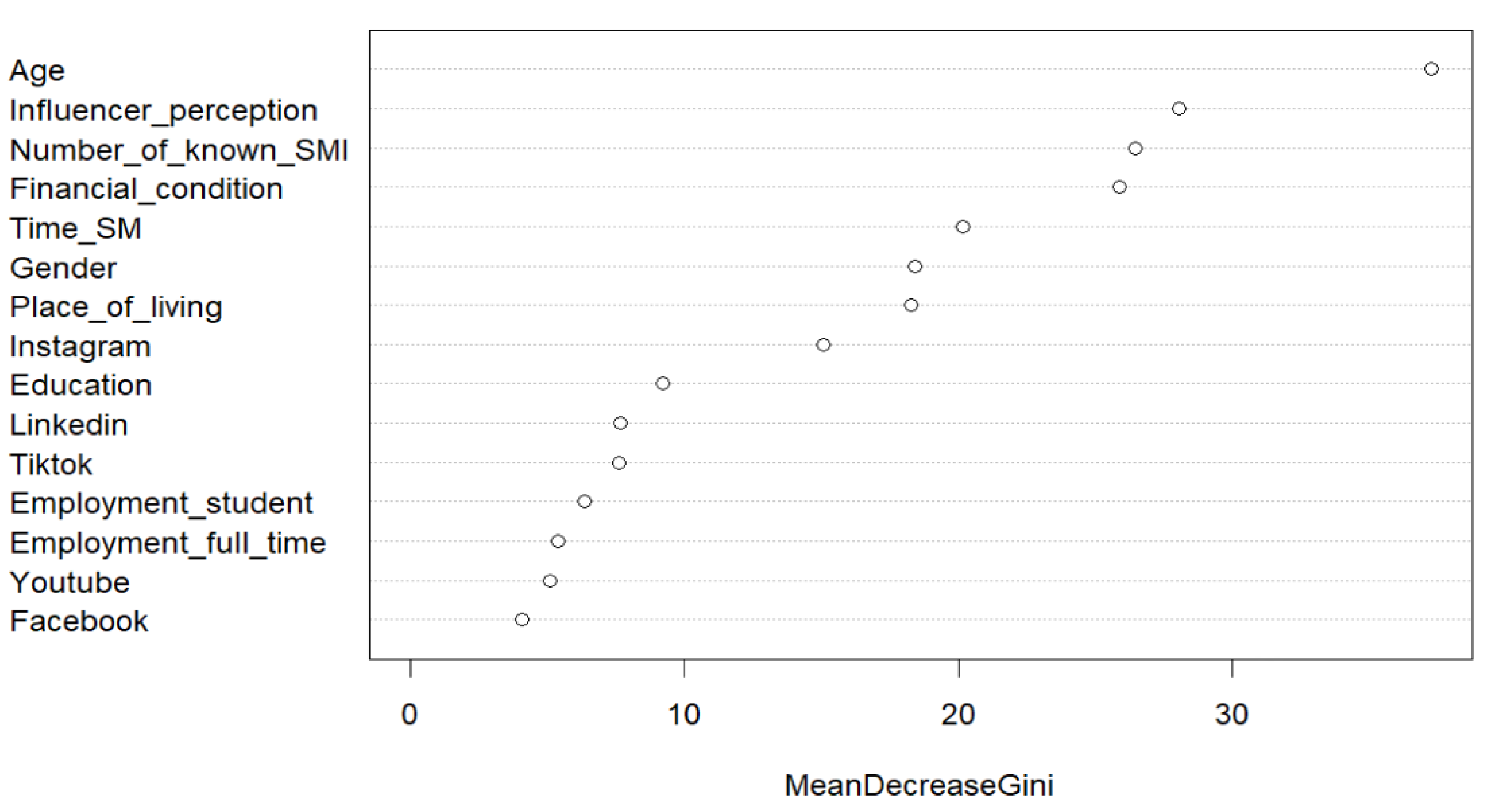

We also employed a RF approach, which is efficient, interpretable, and nonparametric for various types of datasets (Ali et al., 2012) to analyze the characteristics that influenced purchases based on influencers’ recommendations. In addition, we used internal estimates to measure variable importance (Breiman, 2001).

The feature importance chart (

Figure 1) illustrates the ranking of variable importance. The most important predictors included variables of age, influencer perception, number of well-known SMIs, financial condition, daily time spent on social media, and gender.

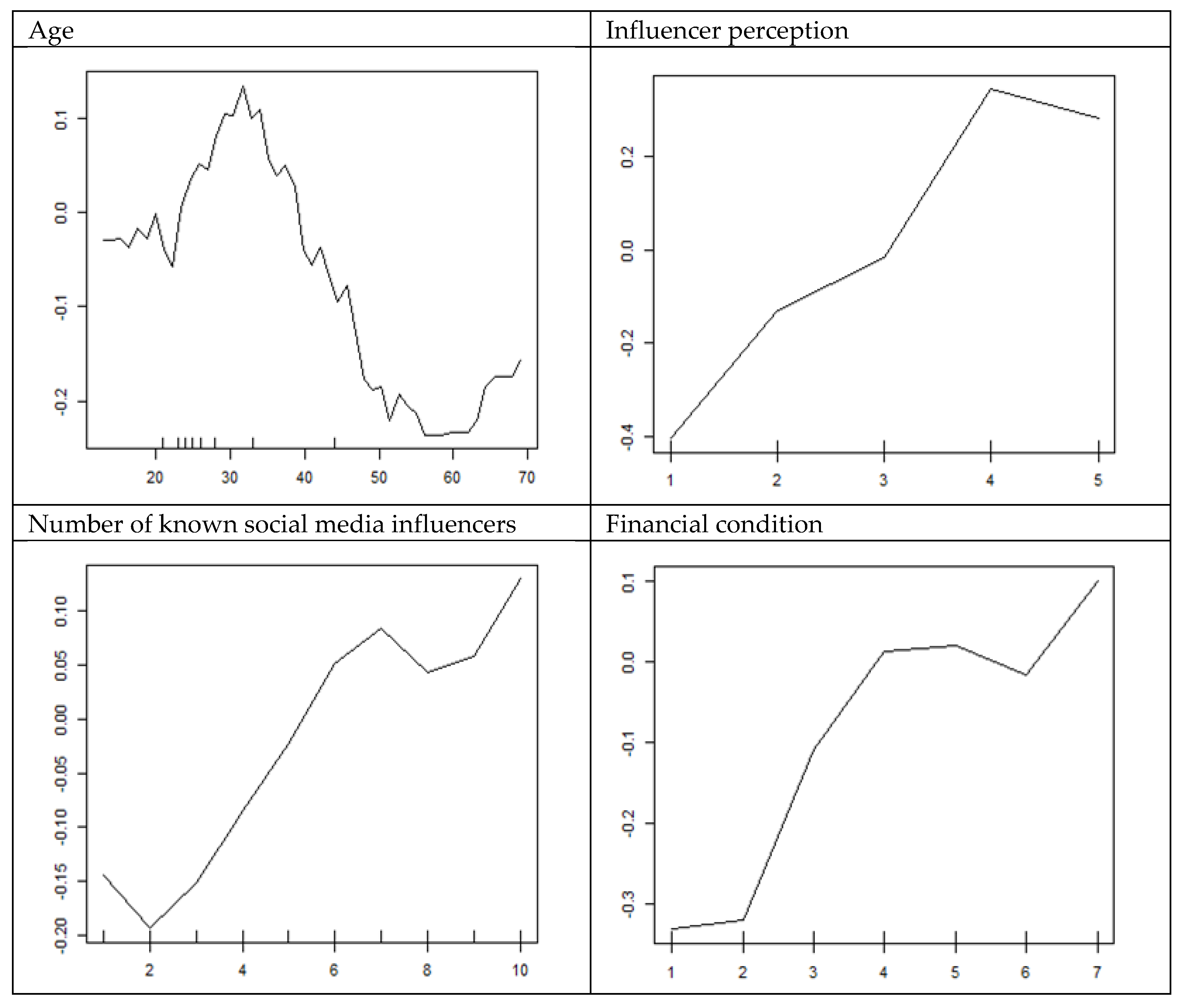

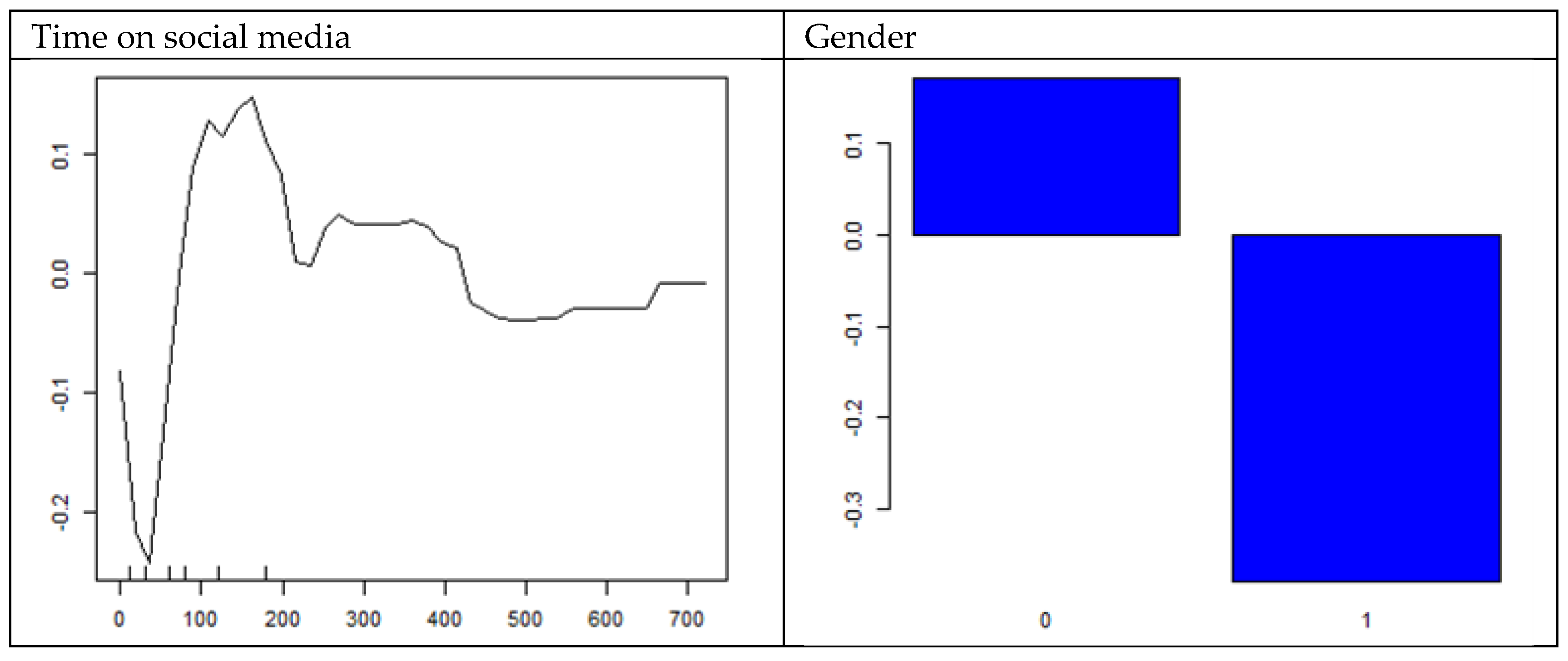

We created partial dependence plots to present low-dimensional graphical renderings of the prediction function. Partial dependence plots show the dependence between the target response and a set of input features of interest, marginalizing the values of all other input features. Intuitively, the partial dependence indicates the expected target response as a function of the input features of interest. This allows for a clearer understanding of the relationship between the outcome and predictors of interest. Using partial dependence plots for the most significant explanatory variables, we assessed how different values of these variables affected purchases based on SMI recommendations.

The variable measuring how many minutes per day the respondent spends on social media initially had a negative impact on the likelihood of purchases based on recommendations. Subsequently, the effect became distinctly positive, then returned to being negative. The effect of the age is nonmonotonic. Initially, age had a positive impact on the likelihood of purchases based on recommendations, but after exceeding 33 years of age, the effect became negative. The variable reflecting the influencer rating had a positive impact on the likelihood of purchases based on SMI recommendations. This effect strengthened as the influencer’s rating increased. People who were familiar with more SMIs had a higher likelihood of making purchases based on recommendations. Financial condition also positively influenced the explained variable, and women were more likely to make purchases based SMI recommendations than men.

Figure 2.

Partial dependence plots for the most significant explanatory variables for purchases based on SMI recommendations.

Figure 2.

Partial dependence plots for the most significant explanatory variables for purchases based on SMI recommendations.

4.4. Influences of Campaigns’ Effectiveness

We also investigated the impact of selected influencers’ advertising collaborations on consumers’ purchase intent, with purchase intent ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 indicates a definite lack of willingness to purchase, and 5 represents maximum interest in making a purchase. We estimated an ordered logit model for each influencer (

Table 6).

Table 6 reveals that the statistically significant explanatory variables influencing consumers’ intent to purchase a recommended product for all SMIs included attitude toward the brand promoted and the perceived authenticity of the influencer’s presentation. As a positive attitude toward the brand and perceived authenticity increased, the probability of responding “definitely yes” to the question concerning the likelihood of purchasing the product rose. The factor that was statistically significant for the model describing Robert Lewandowski’s campaign and Mateusz Trąbka’s campaign was respondents’ positive attitude toward the influencer. This variable positively influenced the likelihood of responding “definitely yes” to the question concerning the intent to purchase the product. Furthermore, a statistically significant variable for Martyna Wojciechowska’s campaign was the respondent’s interest in the industry in which the influencer operates. This variable had a positive effect on the purchase intent toward the advertised product.

In conclusion, after analyzing the four SMI advertising campaigns, the significant factors included attitude toward the promoted brand and the influencer’s authenticity. These variables were found to have a positive impact on purchase intent; therefore, companies advertising products should prioritize enhancing the perceived authenticity of the individuals with whom they collaborate. Ultimately, we can infer that if a brand collaborates with an influencer that has high perceived authenticity whose publications reach an audience that is sympathetic to the brand, this could potentially increase the effectiveness of an SMI campaign.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The aim of this study was to examine the phenomenon of SMI marketing within the framework of the paradox of choice and the economy of attention, employing advanced econometric methods such as logistic regression, an ordered logit model, and data science techniques, including supervised and unsupervised machine learning and the RF algorithm. In previous research addressing similar topics econometric modeling and data science methods have not been used often, and studies also used smaller datasets. For this study, we conducted a survey that primarily focused on analyzing social media users’ behavior. The analysis revealed answers to the research questions posed.

The findings demonstrate that influencers have substantial influence over some social media users’ purchasing decisions, with almost half of the respondents making at least one purchase in the past based on SMI recommendations. A slightly larger proportion of respondents (approximately 65%) indicated interest in SMI-promoted products. Influencers are effective when they attract users’ attention and when followers engage with the products they recommend; however, advertisers’ objectives are even broader—to drive purchase intent—which was found to be successful two-thirds of the individuals who expressed interest in the product. While it is essential to capture user attention online, it is not a sufficient condition to ensure that users will actually make a purchase.

Nasir et al. (2021) examined whether it is possible to distinguish segments of consumers that use social media platforms in relation to their perceptions of influencers or advertisements. Our study identified three groups of Instagram users using unsupervised machine learning, revealing heterogeneity among the responding social media users. One group was particularly more receptive to influencer recommendations, primarily including young women, aged 24–29, with higher education, in good financial positions that live in large cities. These results align with Warner-Søderholm et al. (2018) and Hermanda et al. (2019). Referencing the logistic regression estimates, we assert that the main factors that positively affect purchase based on SMI recommendations are gender, good financial position, a positive perception of the influencer, and regularly using the Instagram app. Similar conclusions were obtained using the RF method and partial dependence plots.

The final empirical section of the study addressed the research question regarding aspects of marketing collaboration with influencers that are crucial for stimulating purchase intent. Using the ordered logit model, we determined that crucial factors in stimulating purchase intent are the user’s attitude toward the advertised brand and the perceived authenticity of the influencer.

Other aspects that may influence purchase intent are identification with the SMI and a positive perception of the brand. Hermanda et al. (2019) found influencers to have a positive impact on brand image and consumer product knowledge, but not on purchase intent; thereafter, brand image has a positive impact on purchase intent. Similar conclusions were drawn by Bawack and Bonhoure (2023), emphasizing that the most substantial impact on purchasing decisions results from consumers’ favorable attitudes toward the brand. The positive brand image consideration was also found to be relevant across all influencer campaigns tested. However, a positive attitude toward the influencer significantly increased purchase intent in only one out of the four SMI campaign cases presented. As demonstrated by Bawack and Bonhoure (2023), authenticity was a significant factor across all campaigns. In addition to a positive attitude toward the brand, authenticity is the secondary pillar for stimulating purchase intent.

Influencer marketing is a relatively new method used for product and service promotions, and further research on its effectiveness and evolution is essential. This study has not fully exhausted the topic and there is ample room for future investigations. To deepen the analysis, it would be valuable to conduct focus group meetings to better understand social media users’ motivations for reacting to influencers’ recommendations. A valuable approach could be a live experiment using mouse tracking while users browse Instagram to examine how users’ attention is divided and identify the stimuli that attract their attention for longer periods. This study recruited 513 Polish survey respondents, over 100 were representatives of the 1998 cohort (Generation Z), born in the internet era. To improve the quality of statistical analysis, it would be beneficial to ensure a larger representation of individuals aged 30+. In the final section of the survey, we presented four preselected influencer campaigns. An ideal survey could present campaigns that are customized to respondents based on their interests and industry knowledge.

This study fills a research gap concerning quantitative analysis of data on the effectiveness of influencer marketing. Our results using several complementary methods yielded consistent conclusions. Young, educated women, in good financial conditions that live in large cities may be particularly susceptible to SMI’s influence. Advertisers should primarily focus on this group, while considering adjustments to existing strategies to expand the reach to this group and stimulate recipients who are not naturally receptive to the marketing content published by influencers.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ye, G., Hudders, L., De Jans, S., & De Veirman, M. (2021). The value of influencer marketing for business: A bibliometric analysis and managerial implications. Journal of Advertising, 50(2), 160-178.

- Simon, H.A. (1971). Designing organizations for an information-rich world. In Martin Greenberger (ed.), Computers, Communication, and the Public Interest. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press, 37-72.

- Abidin, C. (2016). Visibility labour: Engaging with Influencers’ fashion brands and# OOTD advertorial campaigns on Instagram. Media International Australia, 161(1), 86-100.

- Trivedi, J., & Sama, R. (2020). The effect of influencer marketing on consumers’ brand admiration and online purchase intentions: An emerging market perspective. Journal of Internet Commerce, 19(1), 103-124.

- Kirkpatrick, D. (2016). Influencer marketing spurs 11 times the ROI over traditional tactics: Study. Marketing Dive, 6.

- Influencer Marketing Hub (2024). The state of Influencer Marketing 2024. From: https://influencermarketinghub.com/influencer-marketing-benchmark-report/ (28.06.2024).

- Statista (2024). Distribution of Instagram users worldwide as of January 2024, by age group. From: https://www.statista.com/statistics/325587/instagram-global-age-group/ (04.03.2024).

- Araujo, T., Neijens, P., & Vliegenthart, R. (2017). Getting the word out on Twitter: The role of influentials, information brokers and strong ties in building word-of-mouth for brands. International Journal of Advertising, 36(3), 496-513.

- Bughin, J., Doogan, J., & Vetvik, O. J. (2010). A new way to measure word-of-mouth marketing. McKinsey Quarterly, 2(1), 113-116.

- Ali, J., Khan, R., Ahmad, N., & Maqsood, I. (2012). Random forests and decision trees. International Journal of Computer Science Issues (IJCSI), 9(5), 272.

- Gabaix, Xavier, Laibson, David, Moloche, Guillermo, and Stephen Weinberg. (2006). Costly information-acquisition: experimental analysis of a boundedly rational model. American Economic Review, 96(4): 1043- 1068.

- Fairchild, C. (2007). Building the authentic celebrity: The “Idol” phenomenon in the attention economy. Popular music and society, 30(3), 355-375.

- Marwick, A. E. (2015). Instafame: Luxury selfies in the attention economy. Public culture, 27(1 (75)), 137-160.

- Smith, A. N., & Fischer, E. (2021). Pay attention, please! Person brand building in organized online attention economies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 49(2), 258-279.

- Dar-Nimrod, I., Rawn, C. D., Lehman, D. R., & Schwartz, B. (2009). The maximization paradox: The costs of seeking alternatives. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(5-6), 631-635.

- Granka, L. A., Joachims, T., & Gay, G. (2004, July). Eye-tracking analysis of user behavior in WWW search. In Proceedings of the 27th annual international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval (pp. 478-479).

- Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (2000). When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing?. Journal of personality and social psychology, 79(6), 995.

- Al-Harbi, A. I., & Badawi, N. S. (2022). Can opinion leaders through Instagram influence organic food purchase behaviour in Saudi Arabia?. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 13(6), 1312-1333.

- Bawack, R. E., & Bonhoure, E. (2023). Influencer is the new recommender: insights for theorising social recommender systems. Information Systems Frontiers, 25(1), 183-197.

- Ridings, C. M., Gefen, D., & Arinze, B. (2002). Some antecedents and effects of trust in virtual communities. The journal of strategic information systems, 11(3-4), 271-295.

- Warner-Søderholm, G., Bertsch, A., Sawe, E., Lee, D., Wolfe, T., Meyer, J., ... & Fatilua, U. N. (2018). Who trusts social media?. Computers in human behavior, 81, 303-315.

- Breves, P., Amrehn, J., Heidenreich, A., Liebers, N., & Schramm, H. (2021). Blind trust? The importance and interplay of parasocial relationships and advertising disclosures in explaining influencers’ persuasive effects on their followers. International Journal of Advertising, 40(7), 1209-1229.

- Hermanda, A., Sumarwan, U., & Tinaprillia, N. (2019). The effect of social media influencer on brand image, self-concept, and purchase intention. Journal of Consumer Sciences, 4(2), 76-89.

- Lookadoo, K. L., & Wong, N. C. (2019). “Hey guys, check this out!# ad” The Impact of Media Figure-User Relationships and Ad Explicitness on Celebrity Endorsements. The Journal of Social Media in Society, 8(1), 178-210.

- Konstantopoulou, A., Rizomyliotis, I., Konstantoulaki, K., & Badahdah, R. (2019). Improving SMEs’ competitiveness with the use of Instagram influencer advertising and eWOM. International journal of organizational analysis, 27(2), 308-321.

- Nasir, V. A., Keserel, A. C., Surgit, O. E., & Nalbant, M. (2021). Segmenting consumers based on social media advertising perceptions: How does purchase intention differ across segments?. Telematics and informatics, 64, 101687.

- Weismueller, J., Harrigan, P., Wang, S., & Soutar, G. N. (2020). Influencer endorsements: How advertising disclosure and source credibility affect consumer purchase intention on social media. Australasian marketing journal, 28(4), 160-170.

- De Veirman, M., Cauberghe, V., & Hudders, L. (2017). Marketing through Instagram influencers: the impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. International journal of advertising, 36(5), 798-828.

- Campbell, C., & Grimm, P. E. (2019). The challenges native advertising poses: Exploring potential federal trade commission responses and identifying research needs. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 38(1), 110-123.

- Kay, S., Mulcahy, R., & Parkinson, J. (2020). When less is more: the impact of macro and micro social media influencers’ disclosure. Journal of marketing management, 36(3-4), 248-278.

- Hwang, Y., & Jeong, S. H. (2016). “This is a sponsored blog post, but all opinions are my own”: The effects of sponsorship disclosure on responses to sponsored blog posts. Computers in human behavior, 62, 528-535.

- Kodinariya, T. M., & Makwana, P. R. (2013). Review on determining number of Cluster in K-Means Clustering. International Journal, 1(6), 90-95.

- Breiman, L. (2001). Random forests. Machine learning, 45, 5-32.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).