Submitted:

08 August 2024

Posted:

20 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

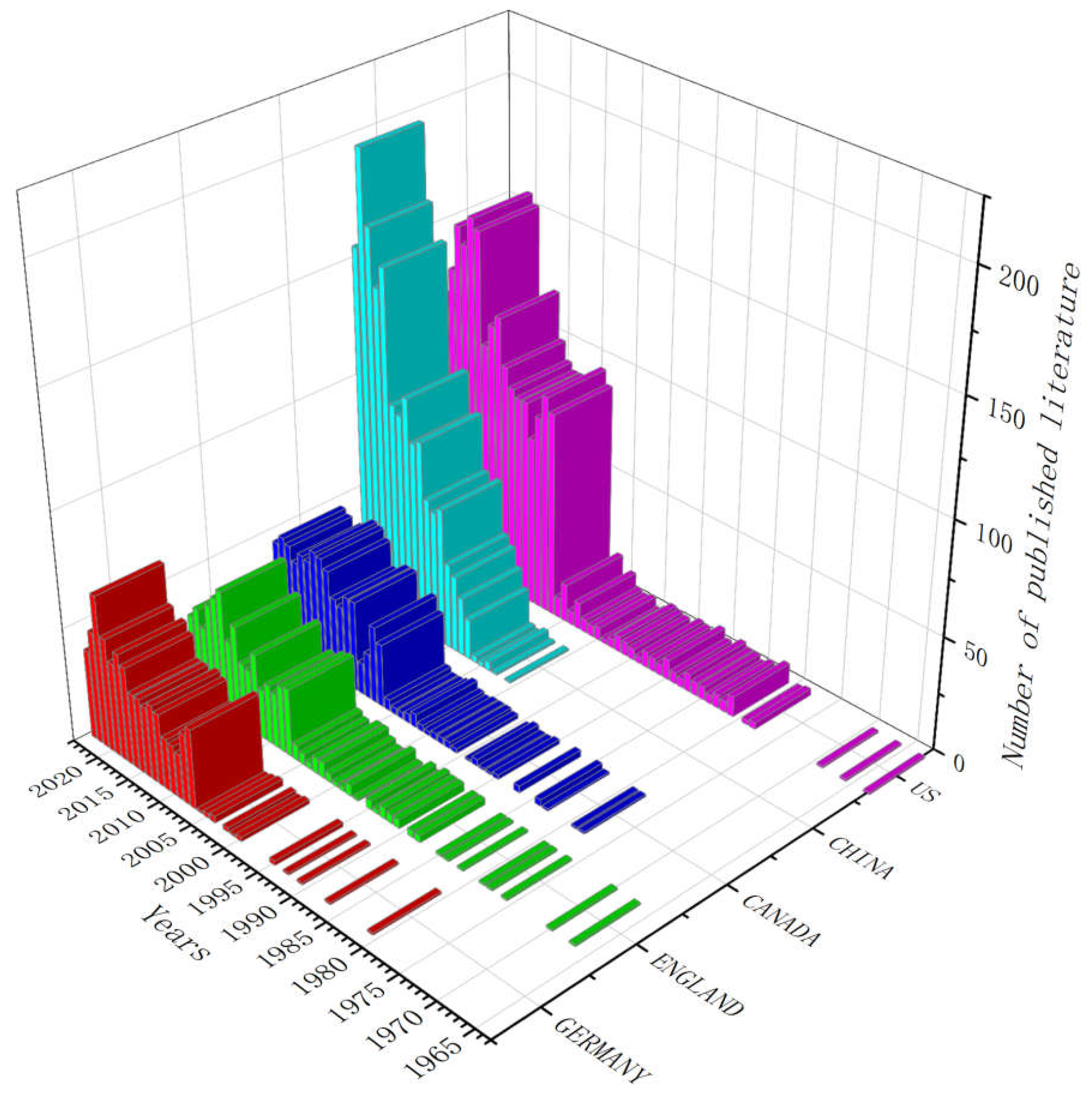

2. Data and Hot Spot Analysis

2.1. Data Sources

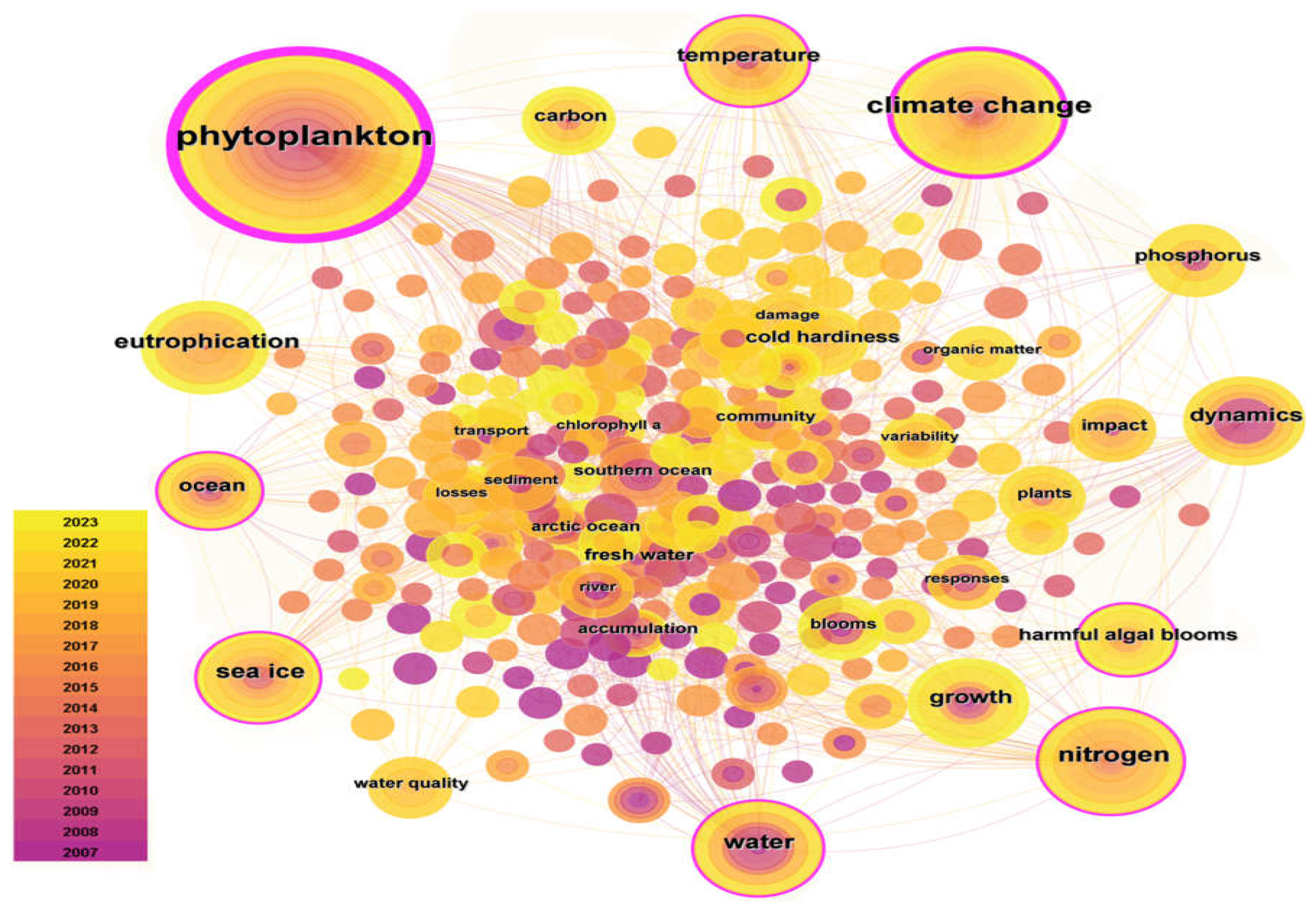

2.2. Hot Spot Analyze

| order | Sort by frequency of occurrence | Centrality sorting | Emergent analysis | ||||||

| Key words | frequency | Key words | Centrality | Key words | Emergence rate | Start | Over | 1963-2023 | |

| 1 | Phytoplankton | 3359 | Phytoplankton | 0.11 | Carbon | 0.87 | 2007 | 2012 |  |

| 2 | Climate change | 1346 | Water | 0.09 | Plankton | 0.09 | 2007 | 2010 |  |

| 3 | Temperature | 1098 | Great lakes | 0.09 | Dynamics | 0.12 | 2009 | 2015 |  |

| 4 | Nitrogen | 1095 | impacts | 0.08 | Sea ice | 0.85 | 2010 | 2014 |  |

| 5 | ice | 1008 | ecology | 0.07 | Nitrogen | 0.5 | 2013 | 2016 |  |

| 6 | Phosphorus | 970 | ice | 0.06 | diversity | 0.69 | 2014 | 2017 |  |

| 7 | Constructed wetland | 969 | dynamics | 0.06 | winter | 0.88 | 2014 | 2019 |  |

| 8 | Denitrification | 823 | climate | 0.05 | tibetan plateau | 0.55 | 2019 | 2023 |  |

| 9 | Waste water treatment | 762 | trends | 0.05 | northern hemisphere | 0.1 | 2020 | 2023 |  |

| 10 | Dynamics | 707 | diversity | 0.05 | lake ice phenology | 0.66 | 2020 | 2023 |  |

3. Definition and Driving Mechanism

3.1. Definition of Algal Blooms in Cold Lake

| Lake/country | Representative dominant species | Impact factor |

| Alte Donau/(US) | Raphidiopsis and raciborskii | TN TP |

| Bethel Lake/Canada | Dolichospermum affinis | TN TP BOD5 |

| Brandy Lake/Canada | Aphanizomenonspp.And Dolichospermum | TN TP BOD5 WT |

| Suya Lake Reservoir/China | Cyanobacteria: Microcystis and Anabaena | TN TP |

| Lake Baikal/Russia | Diatom Melosomum baikalense (Russia) | WT TN |

| Lake Erie/North America | Cyanobacteria: Anabaena and Aphanizomenon and MicrocystisDiatoms and Melosceles Icelandica and filamentous diatoms | TN TP |

| Balkan Lakes/Albania | Diatoms and Cyclotella menifolia and Golden algae and Yellow algae | TN TP |

| Lake Luboszki / Latvia | Cyanobacteria | TN TP BOD5 WT |

| Antarctica | Diatoms and Navicula gracilis and Navicula glacierica and Thalassiosira and Nitzschia fragmenta | TN TP NO3- |

| Hulun Lake/China | Cyanobacteria and Chromococcus Chlorella and Fibrous algae and Chlorella and Chlamydomonas | NH3-N TP TN |

| Lake Khanka/China | Cyanobacteria Microcystis and Anabaena | TN TP BOD5 WT |

| Xidayang Reservoir/China | Cyanobacteria Microcystis | BOD5 TN TP |

| Devil’s Lake/US | Dolichospermum circinalis and Aphanizomenon flos-aquae | BOD5 |

| Fernan Lake/US | Microcystis spp and Dolichospermum spp and Gloeotrichia spp. | TN TP |

| LakeStechlin/Germany | Dolichospermum(primary)and Aphanizomenon, and Planktothrix | BOD5 WT |

| Lough Neagh/Northern Ireland | Planktothrix agardhii and Pseudanabaena spp. | TN TP BOD5 WT |

| Neusiedler see/Austria | Aphanocapsa incerta and Oscillatoria and Dolichospermum | TN TP WT chl-a |

| Three Mile Lake/Canada | Aphanizomenonspp.and Dolichospermum spp. | TP BOD5 WT |

| VänernWeyhenmeyer/Sweden | Aphanizomenon sp. | TN BOD5 WT |

3.2. Hydrothermal and Hydrodynamic Conditions

- (1)

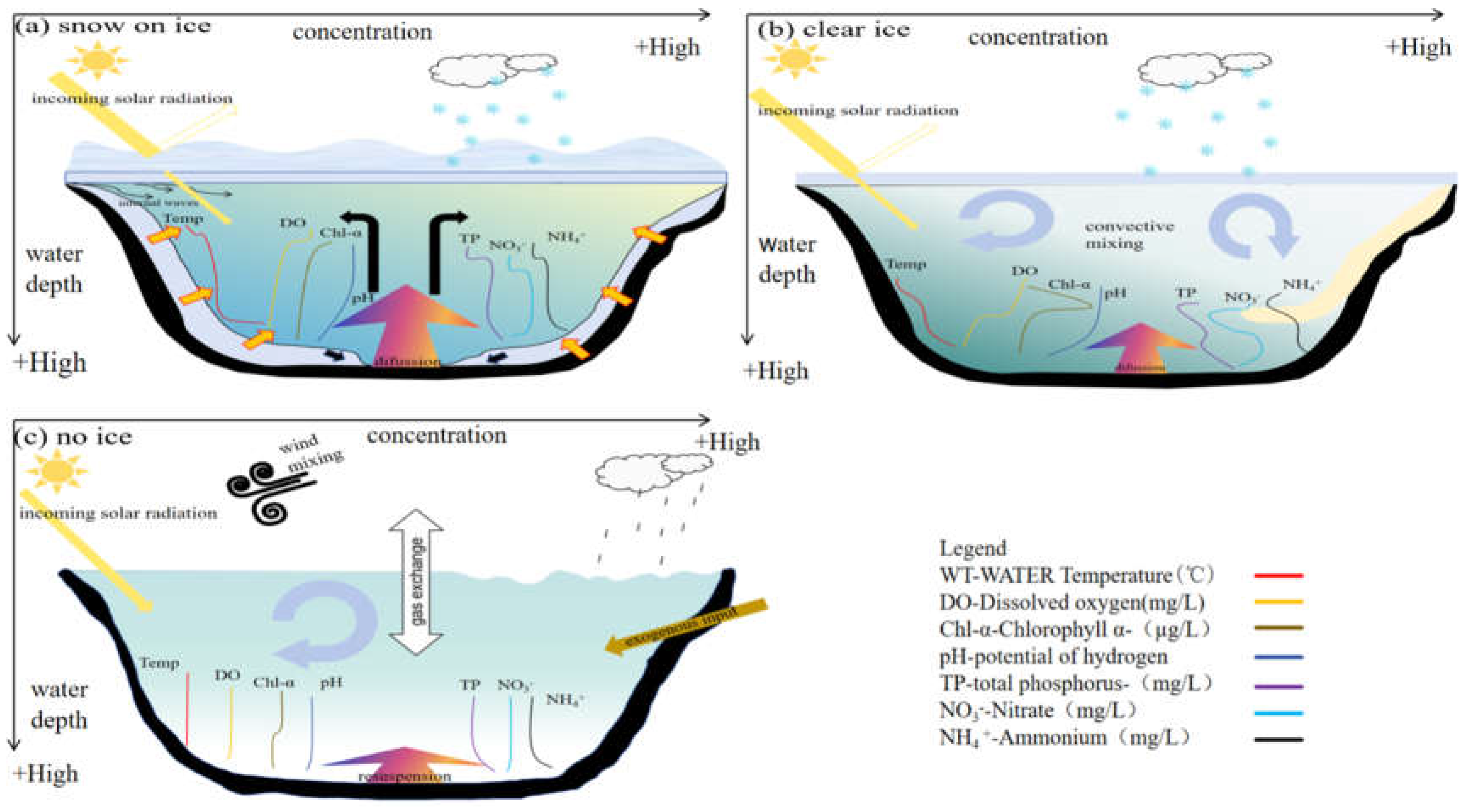

- Freeze-thaw period (Figure 3c): It mainly occured in early winter and early spring. During this period, there were significant temperature variations and lakes were in a state of both freezing and thawing. In early winter, the freezing process caused nutrients from ice to be released into the water, which triggerred osmotic convection and stratification of the water column [16]. This caused the water quality factors to slow down and formed a stable stratified state [26]. During melting, solar radiation (higher than in winter) penetrating the ice will cause hydrodynamic processes to become more intensity [27]. Radiation-driven (RDC) convection driven vertical convective circulation, which penetrates from the surface boundary layer to the stratified water column below [28]. How water quality factors were affected by increasing water temperature, increasing convection and increasing resussuspension are worthy of further discussion. The melting of ice and snow in early spring can lead to a large amount of freshwater flowing into lakes, exacerbating the resuspension of sediment at the bottom of the lake and carrying a large amount of pollutions into the lake [26]. Wind-induced waves can also cause sediment re-suspension, which induces the release of nutrients (such as nitrogen and phosphorus) from the sediment into the water body [29].

- (2)

- Ice-covered period (Figure 3a-b): mainly occured in midwinter. The presence of snow and ice reduced the available solar radiation under the ice, and the radiation-driven convection has little affected on the hydrodynamic force under the ice (Figure 3a) [26]. Lake convective circulation continued to occur slowly when there was no snow on the ice (Figure 3b) [24].

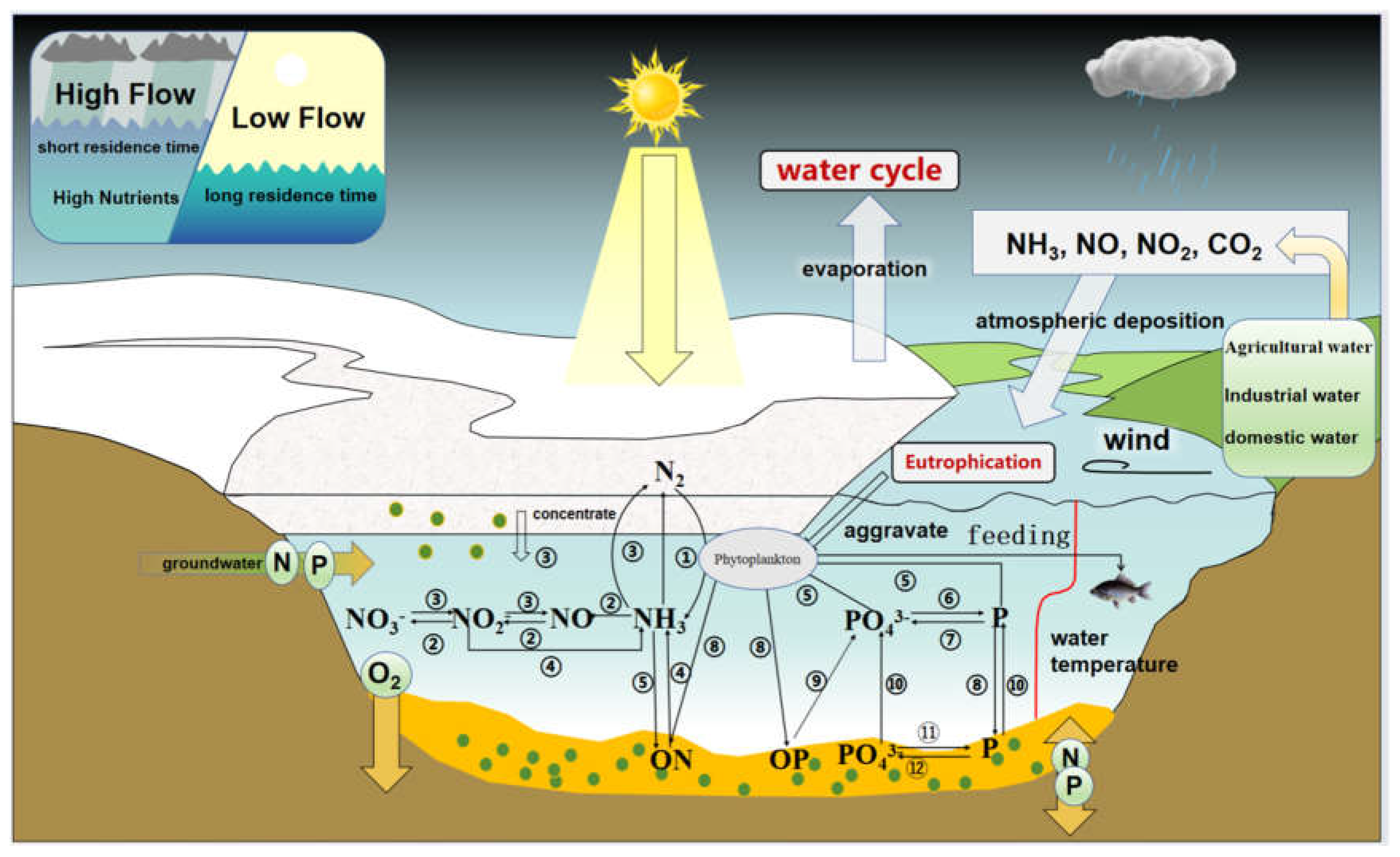

3.3. Nutrient Migration and Transformation During Freezing

3.4. Phytoplankton Characteristics

4. Advances in Research Methods

4.1. Conventional Technical Means

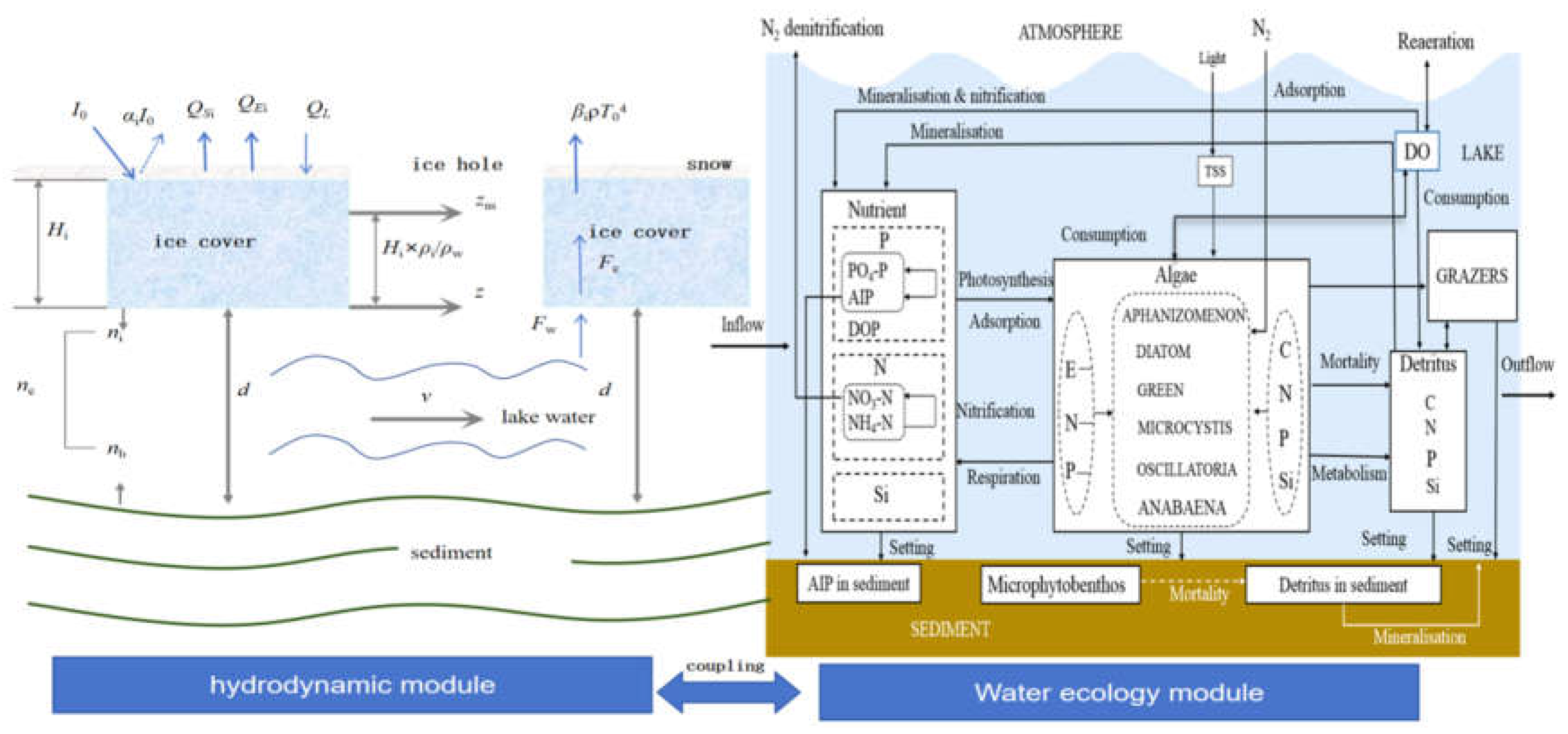

4.2. Numerical Simulation Model

5. Response to Climate Change

6. Conclusion and Outlook

- (1)

- Provide a definition of the validity of cold lakes with physical and ecological significance;

- (2)

- Accurately characterize the subglacial hydrodynamics and biogeochemical processes under the action of ice sheet formation and decline, so as to reveal the internal mechanism of algal blooms in cold lakes;

- (3)

- Build a comprehensive simulation technology of hydrodynamics, water quality and water ecology for cold lakes in all seasons, so as to provide technical means for the precise prevention and control of algal blooms in cold lakes;

- (4)

- Strengthen the in-depth understanding of the response of algal blooms in cold lakes to climate change, so as to propose adaptive prevention and control strategies to cope with future climate change.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflict of Interest

References

- Huisman, J.; Codd, G.A.; Paerl, H.W.; et al. Cyanobacterial blooms. NatureReviews Microbiology 2018, 16, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merel, S.; Walker, D.; Chicana, R.; et al. State of knowledge and concerns on cyanobacterial blooms and cyanotoxins. Environment international 2013, 59, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellner, K.G. Physiology, ecology, and toxic properties of marine cyanobacteria blooms. Limnology and oceanography 1997, 42, 1089–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, I.R. Toxic cyanobacterial bloom problems in Australian waters: risks and impacts on human health. Phycologia 2001, 40, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, J.M.; Davis, T.W.; Burford, M.A.; et al. The rise of harmful cyanobacteria blooms: the potential roles of eutrophication and climate change. Harmful algae 2012, 14, 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, W.F.; Hobbie, J.E.; Laybourn-Parry, J. Introduction to the limnology of high-latitude lake and river ecosystems. Polar lakes and rivers: limnology of Arctic and Antarctic aquatic ecosystems 2008, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Przytulska, A.; Bartosiewicz, M.; Vincent, W.F. Increased risk of cyanobacterialblooms in northern high-latitude lakes through climate warming and phosphorusenrichment. Freshwater Biology 2017, 62, 1986–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, W.F. Cold tolerance in cyanobacteria and life in the cryosphere[M]//Algae and cyanobacteria in extreme environments. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands 2007, 287-301.

- Pandey, K.D.; Shukla, S.P.; Shukla, P.N.; et al. Cyanobacteria in Antarctica: ecology, physiology and cold adaptation. CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY-PARIS-WEGMANN- 2004, 50, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmaso, N.; Capelli, C.; Shams, S.; et al. Expansion of bloom-forming Dolichospermum lemmermannii (Nostocales, Cyanobacteria) to the deep lakes south of the Alps: colonization patterns, driving forces and implications for water use. Harmful Algae 2015, 50, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babanazarova, O.; Sidelev, S.; Schischeleva, S. The structure of winter phytoplankton in Lake Nero, Russia, a hypertrophic lake dominated by Planktothrix-like Cyanobacteria. Aquatic Biosystems 2013, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinl, K.L.; Harris, T.D.; North, R.L.; et al. Blooms also like it cold. Limnology and Oceanography Letters 2023, 8, 546–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkundakci, D.; Gsell, A.S.; Hintze, T.; et al. Winter severity determines functional trait composition of phytoplankton in seasonally ice-covered lakes. Global change biology 2016, 22, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampton, S.E.; Moore, M.V.; Ozersky, T.; et al. Heating up a cold subject: prospects for under-ice plankton research in lakes. Journal of plankton research 2015, 37, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.T. The Ecology of Phytoplankton in an Ice-covered Lake[D]. Harvard University, 1963.

- Jansen, J.; MacIntyre, S.; Barrett, D.C.; et al. Winter limnology: How do hydrodynamics and biogeochemistry shape ecosystems under ice? Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 2021, 126, e2020JG006237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.M.; Hampton, S.E. Winter limnology as a new frontier. Limnology and Oceanography Bulletin 2016, 25, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favot, E.J.; Rühland, K.M.; DeSellas, A.M.; et al. Climate variability promotes unprecedented cyanobacterial blooms in a remote, oligotrophic Ontario lake: evidence from paleolimnology. Journal of Paleolimnology 2019, 62, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favot, E.J.; Rühland, K.M.; DeSellas, A.M.; et al. Climate variability promotes unprecedented cyanobacterial blooms in a remote, oligotrophic Ontario lake: evidence from paleolimnology. Journal of Paleolimnology 2019, 62, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klanten, Y.; MacIntyre, S.; Fitzpatrick, C.; et al. Regime shifts in lake oxygen and temperature in the rapidly warming high Arctic. Geophysical Research Letters 2024, 51, e2023GL106985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonen, K.; Leppäranta, M.; Viljanen, M.; et al. Perspectives in winter limnology: closing the annual cycle of freezing lakes. Aquatic Ecology 2009, 43, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. CiteSpace II: Detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. Journal of the American Society for information Science and Technology 2006, 57, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; et al. Characteristics of the Northern Hemisphere cold regions changes from 1901 to 2019. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leppäranta, M. Freezing of lakes[M]//Freezing of Lakes and the Evolution of their Ice Cover. Cham: Springer International Publishing 2023, 17-62.

- Bouffard, D.; Zdorovennova, G.; Bogdanov, S.; et al. Under-ice convection dynamics in a boreal lake. Inland Waters 2019, 9, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Huang, W.; Li, R.; et al. Solar radiation transfer in an ice-covered lake at different snow thicknesses. Hydrological Sciences Journal 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wells, M.G.; McMeans, B.C.; et al. A new thermal categorization of ice-covered lakes. Geophysical Research Letters 2021, 48, e2020GL091374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, T.; Terzhevik, A.Y.; Mironov, D.V.; et al. Radiatively driven convection in an ice-covered lake investigated by using temperature microstructure technique. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2003, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talling, J.F. Photosynthetic characteristics of some freshwater plankton diatoms in relation to underwater radiation. The New Phytologist 1957, 56, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, F. Sedimentation and sediment resuspension in Lake Ontario. [CrossRef]

- Journal of Great Lakes Research1985, 11, 13–25. [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, L.; Malm, J.; Terzhevik, A.; et al. Field investigation of winter thermo-and hydrodynamics in a small Karelian lake. Limnology and oceanography 1996, 41, 1502–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, E.; Søreide, J.E.; Hessen, D.O.; et al. Consequences of changing sea-ice cover for primary and secondary producers in the European Arctic shelfseas: Timing, quantity, and quality. Progress in Oceanography 2011, 90, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Hei, P.; Song, J.; et al. Nitrogen variations during the ice-on season in the eutrophic lakes. Environmental Pollution 2019, 247, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, D.K.; Goldthwait, S.A.; Hansell, D.A. Zooplankton vertical migration and the active transport of dissolved organic and inorganic nitrogen in the Sargasso Sea. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 2002, 49, 1445–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Huang, W.; Li, R.; et al. Solar radiation transfer in an ice-covered lake at different snow thicknesses. Hydrological Sciences Journal 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B. Physical Processes in Ice-covered Lakes[D]. University of Toronto (Canada), 2022.

- Whitfield, C.J.; Casson, N.J.; North, R.L.; et al. The effect of freeze-thaw cycles on phosphorus release from riparian macrophytes in cold regions. Canadian Water Resources Journal/Revue Canadienne des Ressources Hydriques 2019, 44, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Changyou, L.; Leppäranta, M.; et al. Notable increases in nutrient concentrations in a shallow lake during seasonal ice growth. Water Science and Technology 2016, 74, 2773–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Wang, Y.; He, J.; et al. Phosphorus mobility among sediments, water and cyanobacteria enhanced by cyanobacteria blooms in eutrophic Lake Dianchi. Environmental Pollution 2016, 219, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallina, S.M.; Cermeno, P.; Dutkiewicz, S.; et al. Phytoplankton functional diversity increases ecosystem productivity and stability. Ecological Modelling 2017, 361, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borics, G.; Abonyi, A.; Salmaso, N.; et al. Freshwater phytoplankton diversity: models, drivers and implications for ecosystem properties. Hydrobiologia 2021, 848, 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanabe, Y.; Kudoh, S.; Imura, S.; et al. Phytoplankton blooms under dim and cold conditions in freshwater lakes of East Antarctica. Polar Biology 2008, 31, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungblut, A.D.; Lovejoy, C.; Vincent, W.F. Global distribution of cyanobacterial ecotypes in the cold biosphere. The ISME Journal 2010, 4, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priscu, J.C.; Adams, E.E.; Paerl, H.W.; et al. Perennial Antarctic lake ice: a refuge for cyanobacteria in an extreme environment. Life in ancient ice 2005, 22–49. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, A.; Kim, D.K.; Perhar, G.; et al. Integrative analysis of the Lake Simcoe watershed (Ontario, Canada) as a socio-ecological system. Journal of environmental management 2017, 188, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, D.; Yau, S.; Williams, T.J.; et al. Key microbial drivers in Antarctic aquatic environments. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2013, 37, 303–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, R.; Thangaradjou, T.; Kumar, S.S.; et al. Water quality and phytoplankton characteristics in the Palk Bay, southeast coast of India. Journal of environmental biology 2006, 27, 561–566. [Google Scholar]

- Montes-Hugo, M.; Doney, S.C.; Ducklow, H.W.; et al. Recent changes in phytoplankton communities associated with rapid regional climate change along the western Antarctic Peninsula. Science 2009, 323, 1470–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prowse, T.; Alfredsen, K.; Beltaos, S.; et al. Effects of changes in arctic lake and river ice. Ambio 2011, 40, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laybourn-Parry, J.; Pearce, D.A. The biodiversity and ecology of Antarctic lakes: models for evolution. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2007, 362, 2273–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepernick, B.N.; Chase, E.E.; Denison, E.R.; et al. Declines in ice cover are accompanied by light limitation responses and community change in freshwater diatoms. The ISME Journal 2024, wrad015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twiss, M.R.; McKay RM, L.; Bourbonniere, R.A.; et al. Diatoms abound in ice-covered Lake Erie: An investigation of offshore winter limnology in Lake Erie over the period 2007 to 2010. Journal of Great Lakes Research 2012, 38, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.P.; Fernald KM, H.; Anderson, R.S.; et al. Physical and chemical characterization of a spring flood event, Bench Glacier, Alaska, USA:evidence for water storage. Journal of Glaciology 1999, 45, 177–189. [Google Scholar]

- Weyhenmeyer, G.A.; Obertegger, U.; Rudebeck, H.; et al. Towards critical white ice conditions in lakes under global warming. Nature communications 2022, 13, 4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüest, A.; Pasche, N.; Ibelings, B.W.; et al. Life under ice in Lake Onego(Russia)–an interdisciplinary winter limnology study. Inland Waters 2019, 9, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hébert, M.P.; Beisner, B.E.; Rautio, M.; et al. Warming winters in lakes: Later ice onset promotes consumer overwintering and shapes springtime planktonic food webs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2114840118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirillin, G.; Leppäranta, M.; Terzhevik, A.; et al. Physics of seasonally ice-covered lakes: a review. Aquatic sciences 2012, 74, 659–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, F.; Straile, D.; Lorke, A.; et al. Earlier onset of the spring phytoplankton bloom in lakes of the temperate zone in a warmer climate. Global Change Biology 2007, 13, 1898–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, V.; Adrian, R.; Gerten, D. Phytoplankton response to climate warming modified by trophic state. Limnology and Oceanography 2008, 53, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.M.; Sharma, S.; Gray, D.K.; et al. Rapid and highly variable warming of lake surface waters around the globe. Geophysical Research Letters 2015, 42, 773–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, W. Implications of climate warming for Boreal Shield lakes: a review and synthesis. Environmental Reviews 2007, 15, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Grogan, P.; Chu, H.; et al. The effect of freeze-thaw conditionson arctic soil bacterial communities. Biology 2013, 2, 356–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawak, S.D.; Kulkarni, K.; Luis, A.J. A review on extraction of lakes from remotely sensed optical satellite data with a special focus on cryospheric lakes. Advances in Remote Sensing 2015, 4, 196–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegert, M.J.; Makinson, K.; Blake, D.; et al. An assessment of deep hot-water drilling as a means to undertake direct measurement and sampling ofAntarctic subglacial lakes: Experience and lessons learned from the Lake Ellsworth field season 2012/13. Annals of Glaciology 2014, 55, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.C.; Hamblin, P.F. Thermal simulation of a lake with winter ice cover 1. Limnology and Oceanography 1988, 33, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toporowska, M.; Pawlik-Skowronska, B.; Krupa, D.; et al. Winter versus summer blooming of phytoplankton in a shallow lake: effect of hypertrophic conditions. Polish Journal of Ecology 2010, 58, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, D.C.; Filazzola, A.; Woolway, R.I.; et al. Nonlinear responses in interannual variability of lake ice to climate change. Limnology and Oceanography 2024, 69, 789–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozersky, T.; Bramburger, A.J.; Elgin, A.K.; et al. The changing face of winter: lessons and questions from the Laurentian Great Lakes. 2021.

- Yang, F.; Cen, R.; Feng, W.; et al. Dynamic simulation of nutrient distribution in lakes during ice cover growth and ablation. Chemosphere 2021, 281, 130781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsby, A.E.; Hayes, P.K.; Boje, R. The gas vesicles, buoyancy and vertical distribution of cyanobacteria in the Baltic Sea. European Journal of Phycology 1995, 30, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozdnoukhov, A.; Foresti, L.; Kanevski, M. Data-driven topo-climatic mapping with machine learning methods. Natural hazards 2009, 50, 497–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, E.; Marsili-Libelli, S. Spatio-temporal dissolved oxygen dynamics in the Orbetello lagoon by fuzzy pattern recognition. Ecological Modelling 2009, 220, 2415–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralston, D.K.; Moore, S.K. Modeling harmful algal blooms in a changing climate. Harmful Algae 2020, 91, 101729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havens, K.E. Cyanobacteria blooms: effects on aquatic ecosystems. Cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms: state of the science and research needs 2008, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, S.W.; Farnsley, S.E.; LeCleir, G.R.; et al. The relationships between nutrients, cyanobacterial toxins and the microbial community in Taihu (Lake Tai), China. Harmful Algae 2011, 10, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüest, A.; Lorke, A. Small-scale hydrodynamics in lakes. Annual Review of fluid mechanics 2003, 35, 373–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouffard, D.; Wüest, A. Convection in lakes. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 2019, 51, 189–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, L.; Malm, J.; Terzhevik, A.; et al. Field investigation of winter thermo-and hydrodynamics in a small Karelian lake. Limnology and oceanography 1996, 41, 1502–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, B.R.; Imberger, J.; Laval, B.; et al. Modeling the hydrodynamics of stratified lakes[C]//Hydroinformatics 2000 conference. Iowa Institute of Hydraulics Research 2000, 4, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, E.C.; Creed, I.F.; Jones, B.; et al. Global changes may be promoting a rise in select cyanobacteria in nutrient-poor northern lakes. Global Change Biology 2020, 26, 4966–4987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priscu, J.C.; Adams, E.E.; Paerl, H.W.; et al. Perennial Antarctic lake ice: a refuge for cyanobacteria in an extreme environment. Life in ancient ice 2005, 22–49. [Google Scholar]

- Rühland, K.; Paterson, A.M.; Smol, J.P. Hemispheric-scale patterns of climate-related shifts in planktonic diatoms from North American and European lakes. Global Change Biology 2008, 14, 2740–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.J. Diatoms, temperature and climatic change. European Journal of Phycology 2000, 35, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elser, J.J.; Wu, C.; González, A.L.; et al. Key rules of life and the fading cryosphere: Impacts in alpine lakes and streams. Global change biology 2020, 26, 6644–6656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, S.N.; Merchant, C.J. Surface water temperature observations of large lakes by optimal estimation. Canadian Journal of Remote Sensing 2012, 38, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernica, P.; North, R.L.; Baulch, H.M. In the cold light of day: The potential importance of under-ice convective mixed layers to primary producers. Inland Waters 2017, 7, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppäranta, M. Freezing of lakes and the evolution of their ice cover[M]. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer, 2015.

- Smetacek, V. Diatoms and the ocean carbon cycle. Protist 1999, 150, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bopp, L.; Aumont, O.; Cadule, P.; et al. Response of diatoms distribution to global warming and potential implications: A global model study. Geophysical Research Letters 2005, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyhenmeyer, G.A. Warmer winters: are planktonic algal populations in Sweden’s largest lakes affected? AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment 2001, 30, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, S.L.; Izmest’eva, L.R.; Hampton, S.E.; et al. The “M elosira years” of Lake B aikal: Winter environmental conditions at ice onset predict under-ice algal blooms in spring. Limnology and Oceanography 2015, 60, 1950–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffer, M.M.; Schaeffer, B.A.; Darling, J.A.; et al. Quantifying national and regional cyanobacterial occurrence in US lakes using satellite remote sensing. Ecological Indicators 2020, 111, 105976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungblut, A.D.; Vincent, W.F. Cyanobacteria in polar and alpine ecosystems. Psychrophiles: from biodiversity to biotechnology 2017, 181–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckerstorfer, M.; Bühler, Y.; Frauenfelder, R.; et al. Remote sensing of snow avalanches: Recent advances, potential, and limitations. Cold Regions Science and Technology 2016, 121, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynov, A.; Sushama, L.; Laprise, R. Simulation of temperate freezing lakes by one-dimensional lake models: performance assessment for interactive coupling with regional climate models. Boreal environment research 2010, 15, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Surdu, C.M.; Duguay, C.R.; Brown, L.C.; et al. Response of ice cover on shallow lakes of the North Slope of Alaska to contemporary climate conditions (1950–2011): radar remote-sensing and numerical modeling data analysis. The Cryosphere 2014, 8, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Willard, J.; Karpatne, A.; et al. Physics-guided machine learning for scientific discovery: An application in simulating lake temperature profiles. ACM/IMS Transactions on Data Science 2021, 2, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, J.L.; Pernica, P.; Wheater, H.; et al. Parameter sensitivity analysis of a 1-D cold region lake model for land-surface schemes. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 2017, 21, 6345–6362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, S.E.; Moore, M.V.; Ozersky, T.; et al. Heating up a cold subject: prospects for under-ice plankton research in lakes. Journal of plankton research 2015, 37, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolway, R.I.; Merchant, C.J. Amplified surface temperature response of cold, deep lakes to inter-annual air temperature variability. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozersky, T.; Bramburger, A.J.; Elgin, A.K.; et al. The changing face of winter: lessons and questions from the Laurentian Great Lakes. 2021.

- Malmaeus, J.M.; Blenckner, T.; Markensten, H.; et al. Lake phosphorus dynamics and climate warming: A mechanistic model approach. Ecological Modelling 2006, 190, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wells, M.G.; Li, J.; et al. Mixing, stratification, and plankton under lake-ice during winter in a large lake: Implications for spring dissolved oxygen levels. Limnology and Oceanography 2020, 65, 2713–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arp, C.D.; Jones, B.M.; Whitman, M.; et al. Lake Temperature and Ice Cover Regimes in the Alaskan Subarctic and Arctic: Integrated Monitoring, Remote Sensing, and Modeling 1. JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources Association 2010, 46, 777–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.C.; Michalak, A.M.; Pahlevan, N. Widespread global increase in intense lake phytoplankton blooms since the 1980s. Nature 2019, 574, 667–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Country | Identify | References |

| Bates, R. E. And Bilello | US | The maximum snow depth observed on the ground is greater than 0.3m, the average freezing period of rivers and lakes is greater than 100 days per year, and the ice depth is greater than 0.3m in at least one year every 10 years. | Bates, R. E. And Bilello et al. (1966) |

| Yang, Z | China | Yang proposed the criteria for the division of China’s cold regions, including the coldest month temperature below -3°C, the average monthly temperature above 10°C for no more than 4 months, the freezing period of rivers and lakes for more than 100 days, and the proportion of precipitation received in the form of frozen ice exceeding 50%. Yang et al. added the accumulated temperature between 500 and 1000°C and the average number of snow days per year of 30 days to calculate China’s cold regions. | Yang, Z et al. 2000 |

| Paerland and huisman 2008;Lurling et al. 2013 | US | When the annual average water temperature is below 15°C, which is far below the optimal temperature for cyanobacteria to grow, cyanobacterial blooms are observed, which are called cold water cyanobacterial blooms. | Paerland and huisman 2008;Lurling et al. 2013 |

| Maartje 2024 | US | Lake surface ice is defined as cold region lakes | Maartje et al. 2024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).