Submitted:

16 August 2024

Posted:

19 August 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

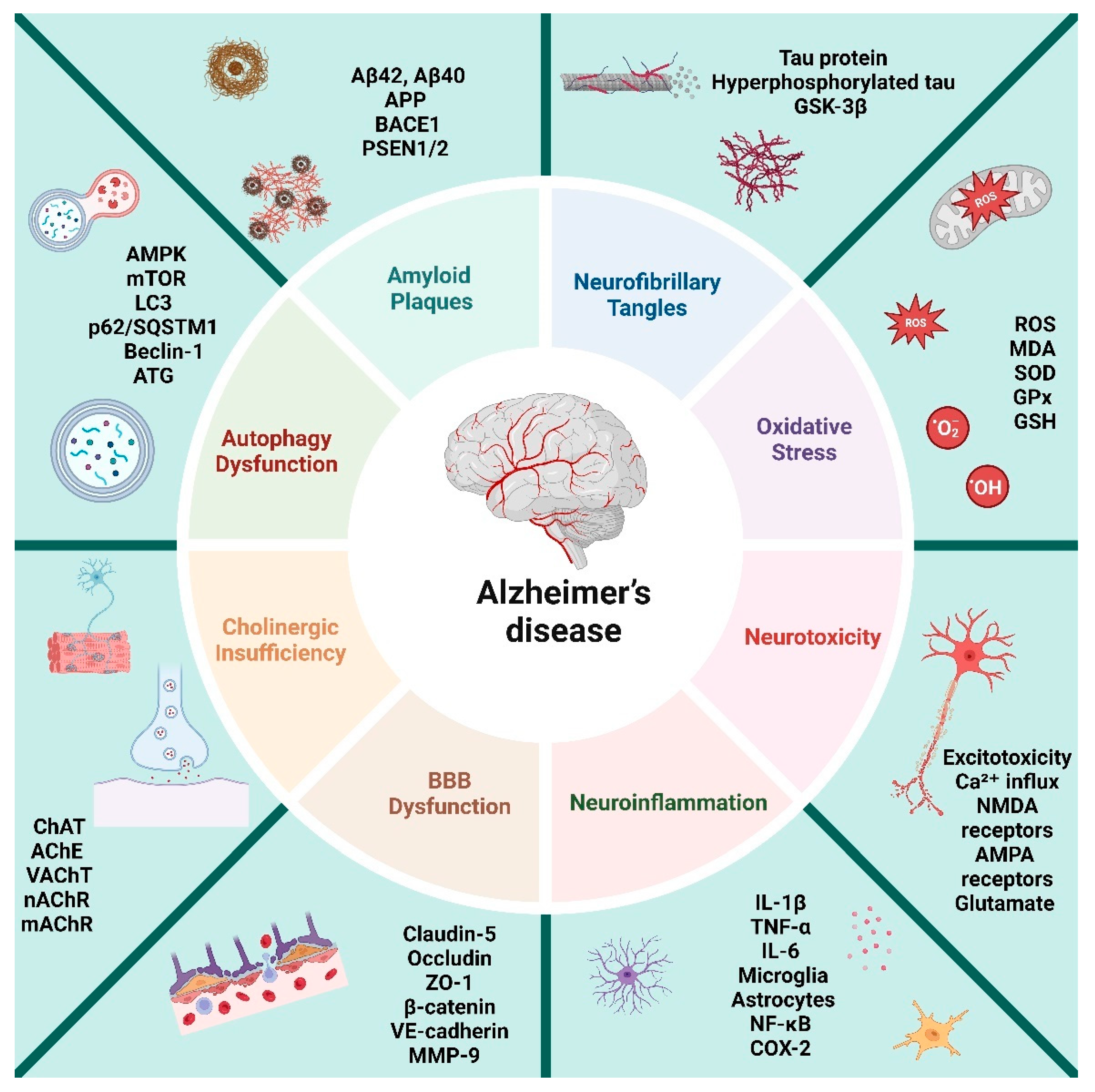

1. Introduction

2. Method

3. Oxidative Stress

4. Oxidative Stress in Alzheimer's Disease

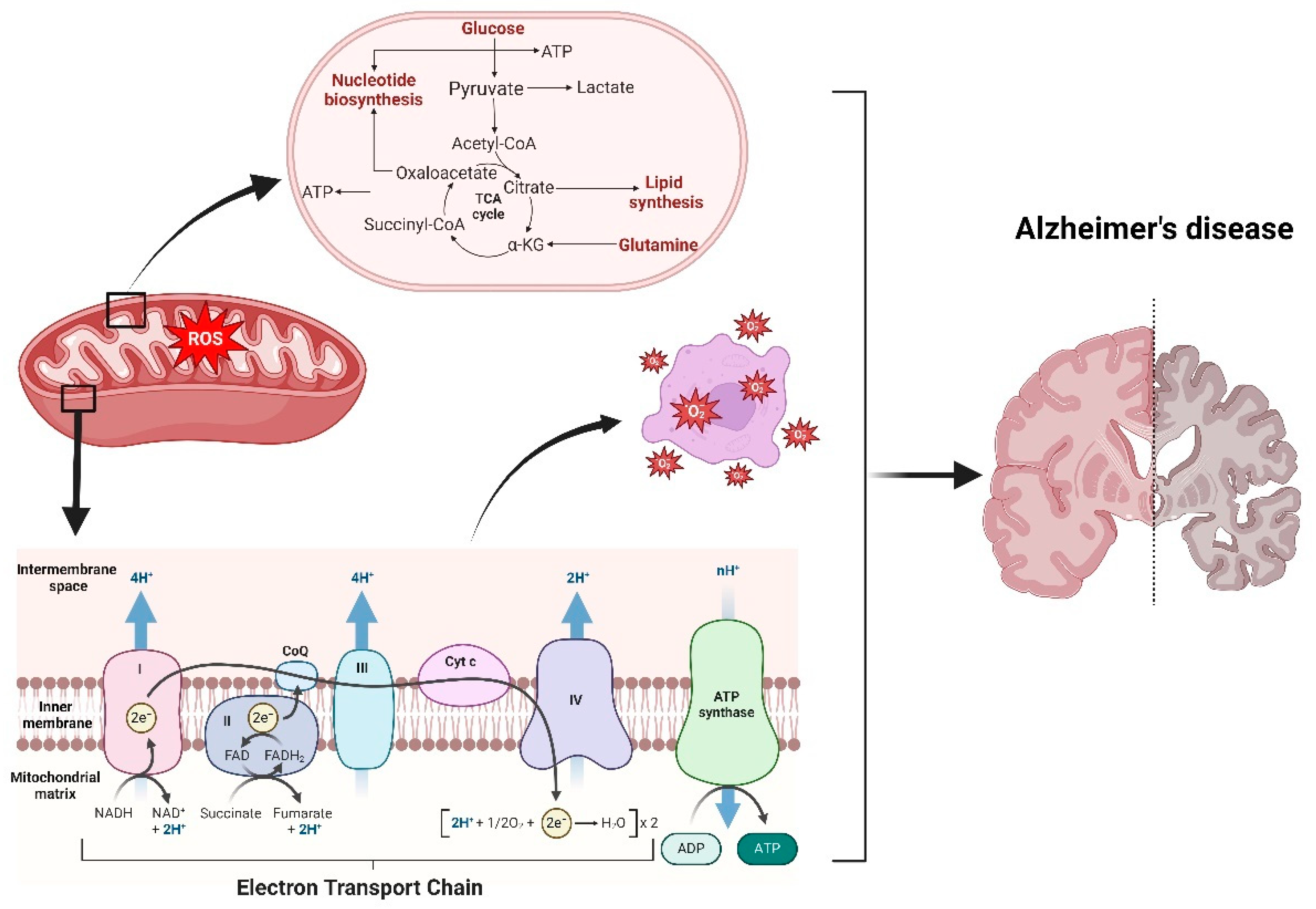

5. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Alzheimer's Disease

6. Neurobiological Implications

6.1. Oxidative Stress and Aβ plaques

6.2. Oxidative Stress and Tau Hyperphosphorylation:

6.3. Oxidative Stress and Glutamatergic Signaling and Synaptic Dysfunction

7. Oxidative Stress Impact on Cellular Functions

7.1. Protein Oxidation:

7.2. Lipid Oxidation:

7.3. DNA Oxidation:

8. Biometals and Alzheimer’s disease Pathogenesis

8.1. Copper, Selenium and Zinc:

8.2. Magnesium, Calcium, and Iron:

9. Antioxidant Deficiency in Alzheimer's Disease

10. Recent Advances in Alzheimer's Disease Therapeutics Targeting Oxidative Stress

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knopman, D.S.; Amieva, H.; Petersen, R.C.; Chételat, G.; Holtzman, D.M.; Hyman, B.T.; Nixon, R.A.; Jones, D.T. Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, A.s. 2019 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimer's & dementia 2019, 15, 321–387. [Google Scholar]

- Association, A.s. What is Alzheimer’s Disease? Available online:. Available online: https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers#:~:text=Alzheimer's%20disease%20accounts%20for%2060%2D80%25%20of%20dementia%20cases.&text=Alzheimer's%20is%20not%20a%20normal,affects%20a%20person%20under%2065. (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Organization, W.H. Dementia. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on).

- DeTure, M.A.; Dickson, D.W. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Molecular Neurodegeneration 2019, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampel, H.; Hardy, J.; Blennow, K.; Chen, C.; Perry, G.; Kim, S.H.; Villemagne, V.L.; Aisen, P.; Vendruscolo, M.; Iwatsubo, T.; et al. The Amyloid-β Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecular Psychiatry 2021, 26, 5481–5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Pozo, A.; Frosch, M.P.; Masliah, E.; Hyman, B.T. Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine 2011, 1, a006189. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ghraiybah, N.F.; Wang, J.; Alkhalifa, A.E.; Roberts, A.B.; Raj, R.; Yang, E.; Kaddoumi, A. Glial cell-mediated neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, 10572. [Google Scholar]

- Alkhalifa, A.E.; Al-Ghraiybah, N.F.; Odum, J.; Shunnarah, J.G.; Austin, N.; Kaddoumi, A. Blood–Brain Barrier Breakdown in Alzheimer’s Disease: Mechanisms and Targeted Strategies. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24, 16288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nunomura, A.; Perry, G.; Aliev, G.; Hirai, K.; Takeda, A.; Balraj, E.K.; Jones, P.K.; Ghanbari, H.; Wataya, T.; Shimohama, S. Oxidative damage is the earliest event in Alzheimer disease. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology 2001, 60, 759–767. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, R.I.; Mehta, R.I. The Vascular-Immune Hypothesis of Alzheimer's Disease. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Wang, X.; Geng, M. Alzheimer’s disease hypothesis and related therapies. Translational Neurodegeneration 2018, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Guo, J.; Ye, X.-Y.; Xie, Y.; Xie, T. Oxidative stress: The core pathogenesis and mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing research reviews 2022, 77, 101619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perluigi, M.; Di Domenico, F.; Butterfield, D.A. Oxidative damage in neurodegeneration: Roles in the pathogenesis and progression of Alzheimer disease. Physiological Reviews 2024, 104, 103–197. [Google Scholar]

- Korovesis, D.; Rubio-Tomás, T.; Tavernarakis, N. Oxidative Stress in Age-Related Neurodegenerative Diseases: An Overview of Recent Tools and Findings. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.W. Role of oxidative stress in Alzheimer's disease. Biomed Rep 2016, 4, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheignon, C.; Tomas, M.; Bonnefont-Rousselot, D.; Faller, P.; Hureau, C.; Collin, F. Oxidative stress and the amyloid beta peptide in Alzheimer's disease. Redox Biol 2018, 14, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: where are we now? Journal of neurochemistry 2006, 97, 1634–1658. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.H.; Kim, J.E.; Rhie, S.J.; Yoon, S. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Exp Neurobiol 2015, 24, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Patterson, C. Atherosclerosis: risks, mechanisms, and therapies; John Wiley & Sons, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.X.; Wang, Y.; Qin, Z.H. Molecular mechanisms of excitotoxicity and their relevance to pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2009, 30, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amartumur, S.; Nguyen, H.; Huynh, T.; Kim, T.S.; Woo, R.-S.; Oh, E.; Kim, K.K.; Lee, L.P.; Heo, C. Neuropathogenesis-on-chips for neurodegenerative diseases. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Drake, J.; Pocernich, C.; Castegna, A. Evidence of oxidative damage in Alzheimer's disease brain: central role for amyloid β-peptide. Trends in molecular medicine 2001, 7, 548–554. [Google Scholar]

- Misrani, A.; Tabassum, S.; Yang, L. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2021, 13, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Alqahtani, T.; Deore, S.L.; Kide, A.A.; Shende, B.A.; Sharma, R.; Chakole, R.D.; Nemade, L.S.; Kale, N.K.; Borah, S.; Deokar, S.S. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-an updated review. Mitochondrion 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Perez Ortiz, J.M.; Swerdlow, R.H. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease: Role in pathogenesis and novel therapeutic opportunities. British journal of pharmacology 2019, 176, 3489–3507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Li, L.; Perry, G.; Lee, H.-g.; Zhu, X. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 2014, 1842, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Swomley, A.M.; Sultana, R. Amyloid β-peptide (1–42)-induced oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease: importance in disease pathogenesis and progression. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2013, 19, 823–835. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.M.; Barnes, K.; De Marco, M.; Shaw, P.J.; Ferraiuolo, L.; Blackburn, D.J.; Venneri, A.; Mortiboys, H. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: a biomarker of the future? Biomedicines 2021, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.W. Role of oxidative stress in Alzheimer's disease. Biomedical reports 2016, 4, 519–522. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, A.H.; Dar, K.B.; Anees, S.; Zargar, M.A.; Masood, A.; Sofi, M.A.; Ganie, S.A. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegenerative diseases; a mechanistic insight. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2015, 74, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Food, U.; Administration, D. FDA grants accelerated approval for Alzheimer’s drug. FDA News Release 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. An insider's perspective on FDA approval of aducanumab. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2023, 9, e12382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson, T.; Popescu, B.O.; Cedazo-Minguez, A. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease: why did antioxidant therapy fail? Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Valko, M.; Rhodes, C.; Moncol, J.; Izakovic, M.; Mazur, M. Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chemico-biological interactions 2006, 160, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Koopman, W.J.; Nijtmans, L.G.; Dieteren, C.E.; Roestenberg, P.; Valsecchi, F.; Smeitink, J.A.; Willems, P.H. Mammalian mitochondrial complex I: biogenesis, regulation, and reactive oxygen species generation. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2010, 12, 1431–1470. [Google Scholar]

- Cheignon, C.m.; Tomas, M.; Bonnefont-Rousselot, D.; Faller, P.; Hureau, C.; Collin, F. Oxidative stress and the amyloid beta peptide in Alzheimer’s disease. Redox biology 2018, 14, 450–464. [Google Scholar]

- Schieber, M.; Chandel, N.S. ROS function in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Current biology 2014, 24, R453–R462. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gella, A.; Durany, N. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease. Cell Adh Migr 2009, 3, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreyev, A.Y.; Kushnareva, Y.E.; Starkov, A. Mitochondrial metabolism of reactive oxygen species. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2005, 70, 200–214. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, R. Metal-catalyzed oxidations of organic compounds: mechanistic principles and synthetic methodology including biochemical processes; Elsevier, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Doorn, J.A.; Petersen, D.R. Covalent adduction of nucleophilic amino acids by 4-hydroxynonenal and 4-oxononenal. Chemico-biological interactions 2003, 143, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Di Meo, S.; Reed, T.T.; Venditti, P.; Victor, V.M. Role of ROS and RNS Sources in Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 2016, 1245049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Koo, N.; Min, D.B. Reactive oxygen species, aging, and antioxidative nutraceuticals. Comprehensive reviews in food science and food safety 2004, 3, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Turrens, J.F. Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J Physiol 2003, 552, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therade-Matharan, S.; Laemmel, E.; Duranteau, J.; Vicaut, E. Reoxygenation after hypoxia and glucose depletion causes reactive oxygen species production by mitochondria in HUVEC. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2004, 287, R1037–R1043. [Google Scholar]

- Turrens, J.F. Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. The Journal of physiology 2003, 552, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.D.; Chen, X.; Fu, J.; Chen, M.; Zhu, H.; Roher, A.; Slattery, T.; Zhao, L.; Nagashima, M.; Morser, J. RAGE and amyloid-β peptide neurotoxicity in Alzheimer's disease. Nature 1996, 382, 685–691. [Google Scholar]

- Kusano, T.; Nishino, T.; Okamoto, K.; Hille, R.; Nishino, T. The mechanism and significance of the conversion of xanthine dehydrogenase to xanthine oxidase in mammalian secretory gland cells. Redox Biol 2023, 59, 102573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvo, M.L.; Marinho, H.S.; Marcelino, P.; Lopes, R.M.; Vale, C.A.; Marques, C.R.; Martins, L.C.; Laverman, P.; Storm, G.; Martins, M.B.A. Superoxide dismutase enzymosomes: Carrier capacity optimization, in vivo behaviour and therapeutic activity. Pharmaceutical research 2015, 32, 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Fridovich, I. Superoxide radical and superoxide dismutases. Oxygen and Living Processes: An Interdisciplinary Approach, 1981; 250–272. [Google Scholar]

- Zorov, D.B.; Juhaszova, M.; Sollott, S.J. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS release. Physiol Rev 2014, 94, 909–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okado-Matsumoto, A.; Fridovich, I. Subcellular distribution of superoxide dismutases (SOD) in rat liver: Cu, Zn-SOD in mitochondria. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 38388–38393. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J.; Koppenol, W.H.; Margoliash, E. Kinetics and mechanism of the reduction of ferricytochrome c by the superoxide anion. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1982, 257, 10747–10750. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Andrés, C.M.C.; Pérez de la Lastra, J.M.; Andrés Juan, C.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. Superoxide Anion Chemistry-Its Role at the Core of the Innate Immunity. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Kukreti, R.; Saso, L.; Kukreti, S. Oxidative Stress: A Key Modulator in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forster, M.J.; Dubey, A.; Dawson, K.M.; Stutts, W.A.; Lal, H.; Sohal, R.S. Age-related losses of cognitive function and motor skills in mice are associated with oxidative protein damage in the brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1996, 93, 4765–4769. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, R.L.; Williams, J.A.; Stadtman, E.P.; Shacter, E. [37] Carbonyl assays for determination of oxidatively modified proteins. In Methods in enzymology; Elsevier, 1994; Volume 233, pp. 346–357. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, S.A.; Karieb, S.S.; Davies, S.J.; Jha, A.N. Assessment of oxidative damage to DNA, transcriptional expression of key genes, lipid peroxidation and histopathological changes in carp Cyprinus carpio L. following exposure to chronic hypoxic and subsequent recovery in normoxic conditions. Mutagenesis 2015, 30, 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Headlam, H.A.; Davies, M.J. Markers of protein oxidation: different oxidants give rise to variable yields of bound and released carbonyl products. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2004, 36, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nadeau, P.J.; Charette, S.J.; Toledano, M.B.; Landry, J. Disulfide bond-mediated multimerization of Ask1 and its reduction by thioredoxin-1 regulate H2O2-induced c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation and apoptosis. Molecular biology of the cell 2007, 18, 3903–3913. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, H.; Ozaki, T.; Nakanishi, M.; Kikuchi, H.; Yoshida, K.; Horie, H.; Kuwano, H.; Nakagawara, A. Oxidative stress induces p53-dependent apoptosis in hepatoblastoma cell through its nuclear translocation. Genes to Cells 2007, 12, 461–471. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, W.; Ijaz, B.; Shabbiri, K.; Ahmed, F.; Rehman, S. Oxidative toxicity in diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease: mechanisms behind ROS/RNS generation. Journal of biomedical science 2017, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Uttara, B.; Singh, A.V.; Zamboni, P.; Mahajan, R. Oxidative stress and neurodegenerative diseases: a review of upstream and downstream antioxidant therapeutic options. Current neuropharmacology 2009, 7, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, B. Oxidative stress and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2013, 2013, 316523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Halliwell, B. Oxidative stress, dysfunctional glucose metabolism and Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 2019, 20, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley-Whitman, M.A.; Lovell, M.A. Biomarkers of lipid peroxidation in Alzheimer disease (AD): an update. Arch Toxicol 2015, 89, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaur, R.J.; Siems, W.; Bresgen, N.; Eckl, P.M. 4-Hydroxy-nonenal—A bioactive lipid peroxidation product. Biomolecules 2015, 5, 2247–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, B.; Wang, X.; Nunomura, A.; Moreira, P.I.; Lee, H.G.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A.; Zhu, X. Oxidative stress signaling in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 2008, 5, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, H.; Solomon, V.A.; Fonteh, A.N. Involvement of Lipids in Alzheimer's Disease Pathology and Potential Therapies. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeevalk, G.D.; Bernard, L.P.; Sinha, C.; Ehrhart, J.; Nicklas, W.J. Excitotoxicity and oxidative stress during inhibition of energy metabolism. Dev Neurosci 1998, 20, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, M.A.; Xiong-Fister, S.; Markesbery, W.R.; Lovell, M.A. Elevated 4-hydroxyhexenal in Alzheimer's disease (AD) progression. Neurobiology of aging 2012, 33, 1034–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Di Domenico, F.; Tramutola, A.; Butterfield, D.A. Role of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE) in the pathogenesis of alzheimer disease and other selected age-related neurodegenerative disorders. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2017, 111, 253–261. [Google Scholar]

- Perluigi, M.; Sultana, R.; Cenini, G.; Di Domenico, F.; Memo, M.; Pierce, W.M.; Coccia, R.; Butterfield, D.A. Redox proteomics identification of 4-hydroxynonenal-modified brain proteins in Alzheimer's disease: role of lipid peroxidation in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. PROTEOMICS–Clinical Applications 2009, 3, 682–693. [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe, D.F.; Brown, G.C. Cellular energy utilization and molecular origin of standard metabolic rate in mammals. Physiol Rev 1997, 77, 731–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, H.S.; Dighe, P.A.; Mezera, V.; Monternier, P.A.; Brand, M.D. Production of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide from specific mitochondrial sites under different bioenergetic conditions. J Biol Chem 2017, 292, 16804–16809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, P.; Sulejczak, D.; Kleczkowska, P.; Bukowska-Ośko, I.; Kucia, M.; Popiel, M.; Wietrak, E.; Kramkowski, K.; Wrzosek, K.; Kaczyńska, K. Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress-A Causative Factor and Therapeutic Target in Many Diseases. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, S.; Abdul Manap, A.S.; Attiq, A.; Albokhadaim, I.; Kandeel, M.; Alhojaily, S.M. From imbalance to impairment: the central role of reactive oxygen species in oxidative stress-induced disorders and therapeutic exploration. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1269581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Ramos-Campo, D.J.; Belinchón-deMiguel, P.; Martinez-Guardado, I.; Dalamitros, A.A.; Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Mitochondria and Brain Disease: A Comprehensive Review of Pathological Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misrani, A.; Tabassum, S.; Yang, L. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress in Alzheimer's Disease. Front Aging Neurosci 2021, 13, 617588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, S.M.; Barnes, K.; De Marco, M.; Shaw, P.J.; Ferraiuolo, L.; Blackburn, D.J.; Venneri, A.; Mortiboys, H. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Alzheimer's Disease: A Biomarker of the Future? Biomedicines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Hu, Y.; Wang, B.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X. Metabolic Dysregulation Contributes to the Progression of Alzheimer's Disease. Front Neurosci 2020, 14, 530219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.S.; Reiman, E.M.; Valla, J.; Dunckley, T.; Beach, T.G.; Grover, A.; Niedzielko, T.L.; Schneider, L.E.; Mastroeni, D.; Caselli, R.; et al. Alzheimer's disease is associated with reduced expression of energy metabolism genes in posterior cingulate neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 4441–4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, A.; Schmitt, K.; Götz, J. Mitochondrial dysfunction - the beginning of the end in Alzheimer's disease? Separate and synergistic modes of tau and amyloid-β toxicity. Alzheimers Res Ther 2011, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Li, L.; Perry, G.; Lee, H.G.; Zhu, X. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1842, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.M.; Cassarino, D.S.; Abramova, N.N.; Keeney, P.M.; Borland, M.K.; Trimmer, P.A.; Krebs, C.T.; Bennett, J.C.; Parks, J.K.; Swerdlow, R.H.; et al. Alzheimer's disease cybrids replicate beta-amyloid abnormalities through cell death pathways. Ann Neurol 2000, 48, 148–155. [Google Scholar]

- Mecocci, P.; MacGarvey, U.; Beal, M.F. Oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA is increased in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol 1994, 36, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Ma, S.L. Is Mitochondria DNA Variation a Biomarker for AD? Genes (Basel) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhong, C. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Bull 2014, 30, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wei, H. Calcium Dysregulation in Alzheimer's Disease: A Target for New Drug Development. J Alzheimers Dis Parkinsonism 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görlach, A.; Bertram, K.; Hudecova, S.; Krizanova, O. Calcium and ROS: A mutual interplay. Redox Biol 2015, 6, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Youle, R.J. The role of mitochondria in apoptosis*. Annu Rev Genet 2009, 43, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardi, P.; Di Lisa, F. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore: molecular nature and role as a target in cardioprotection. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2015, 78, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, F.; Ma, X.; Perry, G.; Zhu, X. Mitochondria dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease: recent advances. Mol Neurodegener 2020, 15, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandas, E.; Rajmohan, V.; Raghunath, B. Neurobiology of Alzheimer's disease. Indian J Psychiatry 2009, 51, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamagno, E.; Guglielmotto, M.; Vasciaveo, V.; Tabaton, M. Oxidative Stress and Beta Amyloid in Alzheimer's Disease. Which Comes First: The Chicken or the Egg? Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, A.B.; Arain, H.A.; Stecker, M.M.; Siegart, N.M.; Kasselman, L.J. Amyloid toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Reviews in the Neurosciences 2018, 29, 613–627. [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield, D.A. The 2013 discovery award from the society for free radical biology and medicine: Selected discoveries from the Butterfield Laboratory of oxidative stress and its sequelae in brain in cognitive disorders exemplified by Alzheimer disease and chemotherapy induced cognitive impairment. Free radical biology & medicine, 2014; 157. [Google Scholar]

- Boutte, A.M.; Woltjer, R.L.; Zimmerman, L.J.; Stamer, S.L.; Montine, K.S.; Manno, M.V.; Cimino, P.J.; Liebler, D.C.; Montine, T.J. Selectively increased oxidative modifications mapped to detergent-insoluble forms of Aβ and β-III tubulin in Alzheimer's disease. The FASEB journal 2006, 20, 1473–1483. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allan Butterfield, D. Amyloid β-peptide (1-42)-induced oxidative stress and neurotoxicity: implications for neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease brain. A review. Free radical research 2002, 36, 1307–1313. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, R.T.; FU, S.; Stocker, R.; Davies, M.J. Biochemistry and pathology of radical-mediated protein oxidation. Biochemical Journal 1997, 324, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Takuma, K.; Yao, J.; Huang, J.; Xu, H.; Chen, X.; Luddy, J.; Trillat, A.-C.; Stern, D.M.; Arancio, O.; Yan, S.S. ABAD enhances Aβ-induced cell stress via mitochondrial dysfunction. The FASEB Journal 2005, 19, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, T.; Popescu, B.O.; Cedazo-Minguez, A. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease: why did antioxidant therapy fail? Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity 2014, 2014, 427318. [Google Scholar]

- Akterin, S.; Cowburn, R.F.; Miranda-Vizuete, A.; Jiménez, A.; Bogdanovic, N.; Winblad, B.; Cedazo-Minguez, A. Involvement of glutaredoxin-1 and thioredoxin-1 in β-amyloid toxicity and Alzheimer's disease. Cell Death & Differentiation 2006, 13, 1454–1465. [Google Scholar]

- Cenini, G.; Sultana, R.; Memo, M.; Butterfield, D.A. Elevated levels of pro-apoptotic p53 and its oxidative modification by the lipid peroxidation product, HNE, in brain from subjects with amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2008, 12, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, R.; Chaudhary, P.; Vatsyayan, R.; Pearce, V.; Jeyabal, P.V.; Zimniak, P.; Awasthi, S.; Awasthi, Y.C. 4-Hydroxynonenal induces p53-mediated apoptosis in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics 2008, 480, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelkow, E.M.; Mandelkow, E. Biochemistry and cell biology of tau protein in neurofibrillary degeneration. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012, 2, a006247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi Naini, S.M.; Soussi-Yanicostas, N. Tau Hyperphosphorylation and Oxidative Stress, a Critical Vicious Circle in Neurodegenerative Tauopathies? Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015, 2015, 151979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, T.; Li, P.; Wei, N.; Zhao, Z.; Liang, H.; Ji, X.; Chen, W.; Xue, M.; Wei, J. The Ambiguous Relationship of Oxidative Stress, Tau Hyperphosphorylation, and Autophagy Dysfunction in Alzheimer's Disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015, 2015, 352723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhapola, R.; Beura, S.K.; Sharma, P.; Singh, S.K.; HariKrishnaReddy, D. Oxidative stress in Alzheimer's disease: current knowledge of signaling pathways and therapeutics. Mol Biol Rep 2024, 51, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Koh, S.H.; Noh, M.Y.; Park, K.W.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, S.H. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta activity plays very important roles in determining the fate of oxidative stress-inflicted neuronal cells. Brain Res 2007, 1129, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, M.; Authelet, M.; Dedecker, R.; Brion, J.P. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta and the p25 activator of cyclin dependent kinase 5 increase pausing of mitochondria in neurons. Neuroscience 2010, 167, 1044–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudher, A.; Shepherd, D.; Newman, T.A.; Mildren, P.; Jukes, J.P.; Squire, A.; Mears, A.; Drummond, J.A.; Berg, S.; MacKay, D.; et al. GSK-3beta inhibition reverses axonal transport defects and behavioural phenotypes in Drosophila. Mol Psychiatry 2004, 9, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibáñez-Salazar, A.; Bañuelos-Hernández, B.; Rodríguez-Leyva, I.; Chi-Ahumada, E.; Monreal-Escalante, E.; Jiménez-Capdeville, M.E.; Rosales-Mendoza, S. Oxidative Stress Modifies the Levels and Phosphorylation State of Tau Protein in Human Fibroblasts. Front Neurosci 2017, 11, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanacora, G.; Rothman, D.L.; Mason, G.; Krystal, J.H. Clinical studies implementing glutamate neurotransmission in mood disorders. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2003, 1003, 292–308. [Google Scholar]

- Krystal, J.H.; Tolin, D.F.; Sanacora, G.; Castner, S.A.; Williams, G.V.; Aikins, D.E.; Hoffman, R.E.; D'Souza, D.C. Neuroplasticity as a target for the pharmacotherapy of anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and schizophrenia. Drug discovery today 2009, 14, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pekny, M.; Nilsson, M. Astrocyte activation and reactive gliosis. Glia 2005, 50, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lipton, S.A.; Rosenberg, P.A. Excitatory amino acids as a final common pathway for neurologic disorders. New England Journal of Medicine 1994, 330, 613–622. [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum, B.S. The role of glutamate in epilepsy and other CNS disorders. Neurology 1994, 44, S14–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maragakis, N.J.; Rothstein, J.D. Mechanisms of disease: astrocytes in neurodegenerative disease. Nature clinical practice Neurology 2006, 2, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kew, J.N.; Kemp, J.A. Ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptor structure and pharmacology. Psychopharmacology 2005, 179, 4–29. [Google Scholar]

- Gjessing, L.; Gjesdahl, P.; Sjaastad, O. The free amino acids in human cerebrospinal fluid. 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Danbolt, N.C. Glutamate uptake. Progress in neurobiology 2001, 65, 1–105. [Google Scholar]

- Görlach, A.; Bertram, K.; Hudecova, S.; Krizanova, O. Calcium and ROS: A mutual interplay. Redox biology 2015, 6, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Girouard, H.; Wang, G.; Gallo, E.F.; Anrather, J.; Zhou, P.; Pickel, V.M.; Iadecola, C. NMDA receptor activation increases free radical production through nitric oxide and NOX2. Journal of Neuroscience 2009, 29, 2545–2552. [Google Scholar]

- Mattson, M.P.; Magnus, T. Ageing and neuronal vulnerability. Nature reviews neuroscience 2006, 7, 278–294. [Google Scholar]

- Szule, J.A.; Jung, J.H.; McMahan, U.J. The structure and function of ‘active zone material’at synapses. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2015, 370, 20140189. [Google Scholar]

- DeKosky, S.T.; Scheff, S.W. Synapse loss in frontal cortex biopsies in Alzheimer's disease: correlation with cognitive severity. Annals of Neurology: Official Journal of the American Neurological Association and the Child Neurology Society 1990, 27, 457–464. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, S.-S.; Chung, H.J. Emerging link between Alzheimer’s disease and homeostatic synaptic plasticity. Neural plasticity 2016, 2016, 7969272. [Google Scholar]

- Tönnies, E.; Trushina, E. Oxidative Stress, Synaptic Dysfunction, and Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2017, 57, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcomer, J.W.; Farber, N.B.; Olney, J.W. NMDA receptor function, memory, and brain aging. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience 2000, 2, 219–232. [Google Scholar]

- Frankland, P.W.; Bontempi, B. The organization of recent and remote memories. Nature reviews neuroscience 2005, 6, 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Trushina, E.; McMurray, C. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Neuroscience 2007, 145, 1233–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Bezprozvanny, I.; Mattson, M.P. Neuronal calcium mishandling and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Trends Neurosci 2008, 31, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.P.; Raymond, L.A. Extrasynaptic NMDA receptor involvement in central nervous system disorders. Neuron 2014, 82, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, S.A. Paradigm shift in neuroprotection by NMDA receptor blockade: memantine and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2006, 5, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.; Boehm, J.; Sato, C.; Iwatsubo, T.; Tomita, T.; Sisodia, S.; Malinow, R. AMPAR removal underlies Abeta-induced synaptic depression and dendritic spine loss. Neuron 2006, 52, 831–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shichiri, M. The role of lipid peroxidation in neurological disorders. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2014, 54, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westra, M.; Gutierrez, Y.; MacGillavry, H.D. Contribution of Membrane Lipids to Postsynaptic Protein Organization. Front Synaptic Neurosci 2021, 13, 790773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolar, M.; Hey, J.; Power, A.; Abushakra, S. Neurotoxic Soluble Amyloid Oligomers Drive Alzheimer's Pathogenesis and Represent a Clinically Validated Target for Slowing Disease Progression. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaid, J.; Mustaly-Kalimi, S.; Stutzmann, G.E. Ca(2+) Dyshomeostasis Disrupts Neuronal and Synaptic Function in Alzheimer's Disease. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Reddy, P.H. Role of Glutamate and NMDA Receptors in Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2017, 57, 1041–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birben, E.; Sahiner, U.M.; Sackesen, C.; Erzurum, S.; Kalayci, O. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. World Allergy Organ J 2012, 5, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefa, U.; Kim, D.; Kim, M.S.; Jeong, N.Y.; Jung, J. Roles of Gasotransmitters in Synaptic Plasticity and Neuropsychiatric Conditions. Neural Plast 2018, 2018, 1824713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajam, Y.A.; Rani, R.; Ganie, S.Y.; Sheikh, T.A.; Javaid, D.; Qadri, S.S.; Pramodh, S.; Alsulimani, A.; Alkhanani, M.F.; Harakeh, S.; et al. Oxidative Stress in Human Pathology and Aging: Molecular Mechanisms and Perspectives. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Paal, J.; Neyts, E.C.; Verlackt, C.C.W.; Bogaerts, A. Effect of lipid peroxidation on membrane permeability of cancer and normal cells subjected to oxidative stress. Chem Sci 2016, 7, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehm, R.; Baldensperger, T.; Raupbach, J.; Höhn, A. Protein oxidation - Formation mechanisms, detection and relevance as biomarkers in human diseases. Redox Biol 2021, 42, 101901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Sun, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, D. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage and neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen Res 2013, 8, 2003–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.J. The oxidative environment and protein damage. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Proteins and Proteomics 2005, 1703, 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Gonos, E.S.; Kapetanou, M.; Sereikaite, J.; Bartosz, G.; Naparło, K.; Grzesik, M.; Sadowska-Bartosz, I. Origin and pathophysiology of protein carbonylation, nitration and chlorination in age-related brain diseases and aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2018, 10, 868–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishii, K. PET approaches for diagnosis of dementia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014, 35, 2030–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M.F.; Argüelles, S. Lipid peroxidation: production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2014, 2014, 360438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Dang, T.N.; Arseneault, M.; Ramassamy, C. Role of by-products of lipid oxidation in Alzheimer's disease brain: a focus on acrolein. J Alzheimers Dis 2010, 21, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Bader Lange, M.L.; Sultana, R. Involvements of the lipid peroxidation product, HNE, in the pathogenesis and progression of Alzheimer's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010, 1801, 924–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montine, T.J.; Peskind, E.R.; Quinn, J.F.; Wilson, A.M.; Montine, K.S.; Galasko, D. Increased cerebrospinal fluid F2-isoprostanes are associated with aging and latent Alzheimer's disease as identified by biomarkers. Neuromolecular Med 2011, 13, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, T.N.; Arseneault, M.; Murthy, V.; Ramassamy, C. Potential role of acrolein in neurodegeneration and in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Mol Pharmacol 2010, 3, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ali, J.; Aziz, M.A.; Rashid, M.M.O.; Basher, M.A.; Islam, M.S. Propagation of age-related diseases due to the changes of lipid peroxide and antioxidant levels in elderly people: A narrative review. Health Sci Rep 2022, 5, e650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, R.J.; Lovell, M.A.; Markesbery, W.R.; Uchida, K.; Mattson, M.P. A role for 4-hydroxynonenal, an aldehydic product of lipid peroxidation, in disruption of ion homeostasis and neuronal death induced by amyloid β-peptide. Journal of neurochemistry 1997, 68, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Selley, M.; Close, D.; Stern, S. The effect of increased concentrations of homocysteine on the concentration of (E)-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal in the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of aging 2002, 23, 383–388. [Google Scholar]

- Tamagno, E.; Robino, G.; Obbili, A.; Bardini, P.; Aragno, M.; Parola, M.; Danni, O. H2O2 and 4-hydroxynonenal mediate amyloid β-induced neuronal apoptosis by activating JNKs and p38MAPK. Experimental neurology 2003, 180, 144–155. [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield, D.A. Brain lipid peroxidation and alzheimer disease: Synergy between the Butterfield and Mattson laboratories. Ageing Res Rev 2020, 64, 101049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul, H.M.; Sultana, R.; St Clair, D.K.; Markesbery, W.R.; Butterfield, D.A. Oxidative damage in brain from human mutant APP/PS-1 double knock-in mice as a function of age. Free Radic Biol Med 2008, 45, 1420–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Castegna, A.; Lauderback, C.M.; Drake, J. Evidence that amyloid beta-peptide-induced lipid peroxidation and its sequelae in Alzheimer’s disease brain contribute to neuronal death. Neurobiology of aging 2002, 23, 655–664. [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield, D.A.; Swomley, A.M.; Sultana, R. Amyloid β-peptide (1-42)-induced oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease: importance in disease pathogenesis and progression. Antioxid Redox Signal 2013, 19, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Xu, L.; Porter, N.A. Free radical lipid peroxidation: mechanisms and analysis. Chemical reviews 2011, 111, 5944–5972. [Google Scholar]

- Lovell, M.A.; Markesbery, W.R. Oxidative DNA damage in mild cognitive impairment and late-stage Alzheimer's disease. Nucleic acids research 2007, 35, 7497–7504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Collins, A.R.; Dusinska, M.; Gedik, C.M.; Stĕtina, R. Oxidative damage to DNA: do we have a reliable biomarker? Environmental health perspectives 1996, 104, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gabbita, S.P.; Lovell, M.A.; Markesbery, W.R. Increased nuclear DNA oxidation in the brain in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of neurochemistry 1998, 71, 2034–2040. [Google Scholar]

- Mattson, M.P.; Chan, S.L. Neuronal and glial calcium signaling in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell calcium 2003, 34, 385–397. [Google Scholar]

- Nunomura, A.; Perry, G.; Pappolla, M.A.; Wade, R.; Hirai, K.; Chiba, S.; Smith, M.A. RNA oxidation is a prominent feature of vulnerable neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neuroscience 1999, 19, 1959–1964. [Google Scholar]

- Lovell, M.A.; Gabbita, S.P.; Markesbery, W.R. Increased DNA oxidation and decreased levels of repair products in Alzheimer's disease ventricular CSF. Journal of neurochemistry 1999, 72, 771–776. [Google Scholar]

- Mecocci, P.; MacGarvey, U.; Beal, M.F. Oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA is increased in Alzheimer's disease. Annals of Neurology: Official Journal of the American Neurological Association and the Child Neurology Society 1994, 36, 747–751. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard, S.; Schurman, S.H.; Harboe, C.; de Souza-Pinto, N.C.; Bohr, V.A. Base excision repair of oxidative DNA damage and association with cancer and aging. Carcinogenesis 2009, 30, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannan, W.J.; Pederson, D.S. Mechanisms and Consequences of Double-Strand DNA Break Formation in Chromatin. J Cell Physiol 2016, 231, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Potlapalli, R.; Quan, H.; Chen, L.; Xie, Y.; Pouriyeh, S.; Sakib, N.; Liu, L.; Xie, Y. Exploring DNA Damage and Repair Mechanisms: A Review with Computational Insights. BioTech (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, N.; Alexandrov, V. Computational science research methods for science education at PG level. Procedia Computer Science 2015, 51, 1685–1693. [Google Scholar]

- Milanowska, K.; Rother, K.; Bujnicki, J.M. Databases and bioinformatics tools for the study of DNA repair. Molecular biology international 2011, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, T.; Du, S.; Peng, Z.; Chen, L. Multifaceted regulation and functions of 53BP1 in NHEJ-mediated DSB repair (Review). Int J Mol Med 2022, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentout, S.; Smith, R.; Jacquier, M.; Huet, S. New methodologies to study DNA repair processes in space and time within living cells. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 9, 730998. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, N.T.; Whitehouse, I.J.; Hooper, N.M. The role of zinc in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2010, 2011, 971021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, K.L.; Schilling, K.M.; Roseman, G.; Markham, K.A.; Dolgova, N.V.; Kroll, T.; Sokaras, D.; Millhauser, G.L.; Pickering, I.J.; George, G.N. X-ray absorption spectroscopy investigations of copper (II) coordination in the human amyloid β peptide. Inorganic Chemistry 2019, 58, 6294–6311. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, G.; Fan, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhou, B. Huntington disease arises from a combinatory toxicity of polyglutamine and copper binding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110, 14995–15000. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, E.; Crews, L.; Ubhi, K.; Hansen, L.; Adame, A.; Cartier, A.; Salmon, D.; Galasko, D.; Michael, S.; Savas, J.N. Progressive accumulation of amyloid-β oligomers in Alzheimer’s disease and in amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice is accompanied by selective alterations in synaptic scaffold proteins. The FEBS journal 2010, 277, 3051–3067. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mezentsev, Y.V.; Medvedev, A.E.; Kechko, O.I.; Makarov, A.A.; Ivanov, A.S.; Mantsyzov, A.B.; Kozin, S.A. Zinc-induced heterodimer formation between metal-binding domains of intact and naturally modified amyloid-beta species: implication to amyloid seeding in Alzheimer’s disease? Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics 2016, 34, 2317–2326. [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri, S.; Squitti, R.; Haertlé, T.; Siotto, M.; Saboury, A.A. Role of copper in the onset of Alzheimer’s disease compared to other metals. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2018, 9, 446. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cherny, R.A.; Atwood, C.S.; Xilinas, M.E.; Gray, D.N.; Jones, W.D.; McLean, C.A.; Barnham, K.J.; Volitakis, I.; Fraser, F.W.; Kim, Y.-S. Treatment with a copper-zinc chelator markedly and rapidly inhibits β-amyloid accumulation in Alzheimer's disease transgenic mice. Neuron 2001, 30, 665–676. [Google Scholar]

- Vaz, F.N.C.; Fermino, B.L.; Haskel, M.V.L.; Wouk, J.; de Freitas, G.B.L.; Fabbri, R.; Montagna, E.; Rocha, J.B.T.; Bonini, J.S. The Relationship Between Copper, Iron, and Selenium Levels and Alzheimer Disease. Biol Trace Elem Res 2018, 181, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Xie, C.; Li, Z.; Zeng, H.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, Z. Selenium Intake and its Interaction with Iron Intake Are Associated with Cognitive Functions in Chinese Adults: A Longitudinal Study. Nutrients 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Vondrakova, D.; Lawson, M.; Valko, M. Metals, oxidative stress and neurodegenerative disorders. Mol Cell Biochem 2010, 345, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Wang, T.T.; Cai, B.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhan, J.X.; Shen, G.M. Genistein protects hippocampal neurons against injury by regulating calcium/calmodulin dependent protein kinase IV protein levels in Alzheimer's disease model rats. Neural Regen Res 2017, 12, 1479–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikawa, N.; Walter, J. Presenilins and γ-Secretase in Membrane Proteostasis. Cells 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greotti, E.; Capitanio, P.; Wong, A.; Pozzan, T.; Pizzo, P.; Pendin, D. Familial Alzheimer's disease-linked presenilin mutants and intracellular Ca(2+) handling: A single-organelle, FRET-based analysis. Cell Calcium 2019, 79, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, M.; Hoke, D.E.; Chua, Y.J.; Li, Q.X.; Culvenor, J.G.; Masters, C.; White, A.R.; Evin, G. Effect of Metal Chelators on γ-Secretase Indicates That Calcium and Magnesium Ions Facilitate Cleavage of Alzheimer Amyloid Precursor Substrate. Int J Alzheimers Dis 2010, 2011, 950932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, C.M.; Lahiri, D.K.; Huang, X.; Rogers, J.T. Amyloid precursor protein and alpha synuclein translation, implications for iron and inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009, 1790, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baruch-Suchodolsky, R.; Fischer, B. Soluble amyloid beta1-28-copper(I)/copper(II)/Iron(II) complexes are potent antioxidants in cell-free systems. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 7796–7806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, J.; Céspedes, E.; Shelford, L.R.; Exley, C.; Collingwood, J.F.; Dobson, J.; van der Laan, G.; Jenkins, C.A.; Arenholz, E.; Telling, N.D. Ferrous iron formation following the co-aggregation of ferric iron and the Alzheimer's disease peptide β-amyloid (1-42). J R Soc Interface 2014, 11, 20140165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everett, J.; Brooks, J.; Lermyte, F.; O'Connor, P.B.; Sadler, P.J.; Dobson, J.; Collingwood, J.F.; Telling, N.D. Iron stored in ferritin is chemically reduced in the presence of aggregating Aβ(1-42). Sci Rep 2020, 10, 10332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.A.; Zhu, X.; Tabaton, M.; Liu, G.; McKeel, D.W., Jr.; Cohen, M.L.; Wang, X.; Siedlak, S.L.; Dwyer, B.E.; Hayashi, T.; et al. Increased iron and free radical generation in preclinical Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis 2010, 19, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.L.; Fan, Y.G.; Yang, Z.S.; Wang, Z.Y.; Guo, C. Iron and Alzheimer's Disease: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Implications. Front Neurosci 2018, 12, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.D.; Tan, E.K. Iron regulatory protein (IRP)-iron responsive element (IRE) signaling pathway in human neurodegenerative diseases. Mol Neurodegener 2017, 12, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, E.; Ganz, T. Hepcidin-Ferroportin Interaction Controls Systemic Iron Homeostasis. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.H.; Gao, W.J.; Kong, W.N.; Xie, H.L.; Peng, Y.; Shao, T.M.; Yu, W.G.; Chai, X.Q. Neuroprotective effect of the active components of three Chinese herbs on brain iron load in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Exp Ther Med 2015, 9, 1319–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Almeida, A.; de Oliveira, J.; da Silva Pontes, L.V.; de Souza Júnior, J.F.; Gonçalves, T.A.F.; Dantas, S.H.; de Almeida Feitosa, M.S.; Silva, A.O.; de Medeiros, I.A. ROS: Basic Concepts, Sources, Cellular Signaling, and its Implications in Aging Pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2022, 2022, 1225578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahal, A.; Kumar, A.; Singh, V.; Yadav, B.; Tiwari, R.; Chakraborty, S.; Dhama, K. Oxidative stress, prooxidants, and antioxidants: the interplay. Biomed Res Int 2014, 2014, 761264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, H.J.; Zhang, H.; Rinna, A. Glutathione: overview of its protective roles, measurement, and biosynthesis. Mol Aspects Med 2009, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubos, E.; Loscalzo, J.; Handy, D.E. Glutathione peroxidase-1 in health and disease: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal 2011, 15, 1957–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajic, V.P.; Van Neste, C.; Obradovic, M.; Zafirovic, S.; Radak, D.; Bajic, V.B.; Essack, M.; Isenovic, E.R. Glutathione "Redox Homeostasis" and Its Relation to Cardiovascular Disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019, 2019, 5028181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Rodríguez, M.A.; Mendoza-Núñez, V.M. Oxidative Stress Indexes for Diagnosis of Health or Disease in Humans. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019, 2019, 4128152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Murata, N.; Noda, Y.; Tahara, S.; Kaneko, T.; Kinoshita, N.; Hatsuta, H.; Murayama, S.; Barnham, K.J.; Irie, K.; et al. SOD1 (copper/zinc superoxide dismutase) deficiency drives amyloid β protein oligomerization and memory loss in mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 44557–44568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olufunmilayo, E.O.; Gerke-Duncan, M.B.; Holsinger, R.M.D. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, P. Oxidative Stress and Its Clinical Applications in Dementia. J Neurodegener Dis 2013, 2013, 319898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.; Herrmann, N.; Chen, J.J.; Saleem, M.; Oh, P.I.; Andreazza, A.C.; Kiss, A.; Lanctôt, K.L. Glutathione Peroxidase Activity Is Altered in Vascular Cognitive Impairment-No Dementia and Is a Potential Marker for Verbal Memory Performance. J Alzheimers Dis 2021, 79, 1285–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studart, A.N.; Nitrini, R. Subjective cognitive decline: The first clinical manifestation of Alzheimer's disease? Dement Neuropsychol 2016, 10, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthold, D.; Joyce, G.; Ferido, P.; Drabo, E.F.; Marcum, Z.A.; Gray, S.L.; Zissimopoulos, J. Pharmaceutical Treatment for Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias: Utilization and Disparities. J Alzheimers Dis 2020, 76, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, E.; Ringman, J.M. Cognitive symptoms of Alzheimer's disease: clinical management and prevention. Bmj 2019, 367, l6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderberg, L.; Johannesson, M.; Nygren, P.; Laudon, H.; Eriksson, F.; Osswald, G.; Möller, C.; Lannfelt, L. Lecanemab, Aducanumab, and Gantenerumab - Binding Profiles to Different Forms of Amyloid-Beta Might Explain Efficacy and Side Effects in Clinical Trials for Alzheimer's Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2023, 20, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Sánchez, R.A.; Torner, L.; Fenton Navarro, B. Polyphenols and Neurodegenerative Diseases: Potential Effects and Mechanisms of Neuroprotection. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhalifa, A.E.; Al-Ghraiybah, N.F.; Kaddoumi, A. Extra-Virgin Olive Oil in Alzheimer's Disease: A Comprehensive Review of Cellular, Animal, and Clinical Studies. International journal of molecular sciences 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, L.; Fernandez, F.; Johnson, J.B.; Naiker, M.; Owoola, A.G.; Broszczak, D.A. Oxidative stress in alzheimer's disease: A review on emergent natural polyphenolic therapeutics. Complement Ther Med 2020, 49, 102294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.H.; Wang, D.W.; Xu, S.F.; Zhang, S.; Fan, Y.G.; Yang, Y.Y.; Guo, S.Q.; Wang, S.; Guo, T.; Wang, Z.Y.; Guo, C. α-Lipoic acid improves abnormal behavior by mitigation of oxidative stress, inflammation, ferroptosis, and tauopathy in P301S Tau transgenic mice. Redox Biol 2018, 14, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, N.B.; Elabed, N.; Punia, S.; Ozogul, F.; Kim, S.K.; Rocha, J.M. Recent Developments in Polyphenol Applications on Human Health: A Review with Current Knowledge. Plants (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucciantini, M.; Leri, M.; Nardiello, P.; Casamenti, F.; Stefani, M. Olive Polyphenols: Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, O.; Dalhat, M.H.; Altamimi, A.S.A.; Rasool, R.; Alzarea, S.I.; Almalki, W.H.; Murtaza, B.N.; Iftikhar, S.; Nadeem, S.; Nadeem, M.S.; Kazmi, I. Green Tea Catechins Attenuate Neurodegenerative Diseases and Cognitive Deficits. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Ju, I.G.; Kim, N.; Huh, E.; Son, S.R.; Hong, J.P.; Choi, Y.; Jang, D.S.; Oh, M.S. Yomogin, Isolated from Artemisia iwayomogi, Inhibits Neuroinflammation Stimulated by Lipopolysaccharide via Regulating MAPK Pathway. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Shi, X.; Ma, C. An overview on therapeutics attenuating amyloid β level in Alzheimer's disease: targeting neurotransmission, inflammation, oxidative stress and enhanced cholesterol levels. Am J Transl Res 2016, 8, 246–269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ekert, J.O.; Gould, R.L.; Reynolds, G.; Howard, R.J. TNF alpha inhibitors in Alzheimer's disease: A systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2018, 33, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisby, B.; Jarrell, J.T.; Agar, M.E.; Cohen, D.S.; Rosin, E.R.; Cahill, C.M.; Rogers, J.T.; Huang, X. Alzheimer's Disease and Its Potential Alternative Therapeutics. J Alzheimers Dis Parkinsonism 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Tan, M.; Liu, A.; Chen, M.; Liu, J.; Pi, R.; Fang, J. Carvedilol, a third-generation β-blocker prevents oxidative stress-induced neuronal death and activates Nrf2/ARE pathway in HT22 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2013, 441, 917–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Guo, Y.E.; Fang, J.H.; Shi, C.J.; Suo, N.; Zhang, R.; Xie, X. Donepezil, a drug for Alzheimer's disease, promotes oligodendrocyte generation and remyelination. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2019, 40, 1386–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atef, M.M.; El-Sayed, N.M.; Ahmed, A.A.M.; Mostafa, Y.M. Donepezil improves neuropathy through activation of AMPK signalling pathway in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Biochem Pharmacol 2019, 159, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, S.S.; Hafez, M.M.; Mehanna, E.T.; Mesbah, N.M.; Abo-Elmatty, D.M. Combined vildagliptin and memantine treatment downregulates expression of amyloid precursor protein, and total and phosphorylated tau in a rat model of combined Alzheimer's disease and type 2 diabetes. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2019, 392, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Xiong, R.; Gong, X. Memantine, NMDA Receptor Antagonist, Attenuates ox-LDL-Induced Inflammation and Oxidative Stress via Activation of BDNF/TrkB Signaling Pathway in HUVECs. Inflammation 2021, 44, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosini, M.; Simoni, E.; Caporaso, R.; Basagni, F.; Catanzaro, M.; Abu, I.F.; Fagiani, F.; Fusco, F.; Masuzzo, S.; Albani, D.; et al. Merging memantine and ferulic acid to probe connections between NMDA receptors, oxidative stress and amyloid-β peptide in Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Med Chem 2019, 180, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, M.; Govitrapong, P.; Boontem, P.; Reiter, R.J.; Satayavivad, J. Mechanisms of Melatonin in Alleviating Alzheimer's Disease. Curr Neuropharmacol 2017, 15, 1010–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.C.; Liu, X.C.; Yang, S.H.; Song, L.L.; Zhou, S.J.; Deng, S.L.; Tian, L.; Cheng, L.Y. Melatonin Inhibits Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis in Cryopreserved Ovarian Tissues via Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling Pathway. Front Mol Biosci 2020, 7, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, S.; Spampinato, S.F.; Sortino, M.A. Early compensatory responses against neuronal injury: A new therapeutic window of opportunity for Alzheimer's Disease? CNS Neurosci Ther 2019, 25, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez Ortiz, J.M.; Swerdlow, R.H. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease: Role in pathogenesis and novel therapeutic opportunities. Br J Pharmacol 2019, 176, 3489–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.; Akram, M.; Shahrukh, M.; Ishrat, T.; Parvez, S. Effects of pramipexole on beta-amyloid(1-42) memory deficits and evaluation of oxidative stress and mitochondrial function markers in the hippocampus of Wistar rat. Neurotoxicology 2022, 92, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jia, Y.; Li, G.; Wang, B.; Zhou, T.; Zhu, L.; Chen, T.; Chen, Y. The Dopamine Receptor D3 Regulates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Depressive-Like Behavior in Mice. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2018, 21, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, S.; OuYang, D.; Lu, J.H. Resveratrol in experimental Alzheimer's disease models: A systematic review of preclinical studies. Pharmacol Res 2019, 150, 104476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; He, J.; Pan, C.; Wang, J.; Ma, M.; Shi, X.; Xu, Z. Resveratrol Activates Autophagy via the AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway to Improve Cognitive Dysfunction in Rats With Chronic Cerebral Hypoperfusion. Front Neurosci 2019, 13, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiger, S.; Matthes, F.; Posey, K.; Kickstein, E.; Weber, S.; Hettich, M.M.; Pfurtscheller, S.; Ehninger, D.; Schneider, R.; Krauß, S. Resveratrol induces dephosphorylation of Tau by interfering with the MID1-PP2A complex. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 13753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detrait, E.R.; Danis, B.; Lamberty, Y.; Foerch, P. Peripheral administration of an anti-TNF-α receptor fusion protein counteracts the amyloid induced elevation of hippocampal TNF-α levels and memory deficits in mice. Neurochem Int 2014, 72, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.T.; Luo, S.F.; Lee, C.W.; Wang, S.W.; Lin, C.C.; Chang, C.C.; Chen, Y.L.; Chau, L.Y.; Yang, C.M. Overexpression of HO-1 protects against TNF-alpha-mediated airway inflammation by down-regulation of TNFR1-dependent oxidative stress. Am J Pathol 2009, 175, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortí-Casañ, N.; Wu, Y.; Naudé, P.J.W.; De Deyn, P.P.; Zuhorn, I.S.; Eisel, U.L.M. Targeting TNFR2 as a Novel Therapeutic Strategy for Alzheimer's Disease. Front Neurosci 2019, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Dhapola, R.; Sarma, P.; Medhi, B.; Reddy, D.H. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's Disease: Current Progress in Molecular Signaling and Therapeutics. Inflammation 2023, 46, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chen, J.; Zhao, J.; Meng, M. Etanercept attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by decreasing inflammation and oxidative stress. PloS one 2014, 9, e108024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalatbary, A.R.; Khademi, E. The green tea polyphenolic catechin epigallocatechin gallate and neuroprotection. Nutr Neurosci 2020, 23, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Wang, M.; Jing, X.; Shi, H.; Ren, M.; Lou, H. (-)-Epigallocatechin gallate protects against cerebral ischemia-induced oxidative stress via Nrf2/ARE signaling. Neurochem Res 2014, 39, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierzynowska, K.; Podlacha, M.; Gaffke, L.; Majkutewicz, I.; Mantej, J.; Węgrzyn, A.; Osiadły, M.; Myślińska, D.; Węgrzyn, G. Autophagy-dependent mechanism of genistein-mediated elimination of behavioral and biochemical defects in the rat model of sporadic Alzheimer's disease. Neuropharmacology 2019, 148, 332–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, K.P.; Shanmuganathan, B.; Manayi, A.; Nabavi, S.F.; Nabavi, S.M. Molecular and Therapeutic Targets of Genistein in Alzheimer's Disease. Mol Neurobiol 2017, 54, 7028–7041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Yang, G.; He, Y.; Xu, H.; Fan, H.; An, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, R.; Cao, G.; Hao, D.; Yang, H. Involvement of α7nAChR in the Protective Effects of Genistein Against β-Amyloid-Induced Oxidative Stress in Neurons via a PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 Pathway-Related Mechanism. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2021, 41, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).