1. Introduction

The variola virus, a highly contagious and lethal pathogen that causes smallpox, poses a significant global health threat. The development of the cowpox-based vaccination by Edward Jenner marked the beginning of the eradication of smallpox [

1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) spearheaded a global eradication campaign in 1966, which was successfully concluded with the last naturally occurring case recorded in Somalia on October 26, 1977. Subsequently, on October 26, 1979, the WHO officially declared the eradication of smallpox, representing the first instance of a disease being eliminated through human efforts [

2].

After this eradication, there was a consensus to destroy all variola virus samples preserved by various countries. However, owing to bioterrorism concerns, the virus samples were kept under WHO supervision. The virus has been preserved to develop vaccines and treatments, advance research on viral structures, prepare for potential bioterrorist threats, and maintain historical and scientific records. The variola virus is currently stored only at the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States and the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology in Russia [

3].

The potential threat of bioterrorism using the smallpox virus is a genuine concern. The variola virus is easily cultivable, can be freeze-dried, and remains stable when protected from heat and ultraviolet light [

4]. Notable past bioterrorism incidents include the 1984 Rajneeshee cult's

Salmonella attack in Oregon, which affected over 750 people, and the 2001 anthrax letters in the USA, causing 22 infections and five deaths. These events underscore the need for vigilance and preparedness. During the Cold War, a former official overseeing the Soviet Union’s biological weapons project reportedly cultivated a large amount of the variola virus in laboratories and conducted experiments for its potential deployment through missiles [

5]. Consequently, the CDC has officially classified the variola virus as a Category A bioterrorism agent [

6].

Specific antivirals, such as cidofovir [

7] and tecovirimat (ST-246) [

8], are under development and exhibit treatment efficacy; however, no definitive cure exists. Therefore, vaccination remains the sole preventive measure. Rapid diagnosis is crucial in containing the spread of the disease during a smallpox outbreak. Direct diagnostic methods, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR), are highly sensitive [

9,

10]; however, their reliance on the presence of the virus during infection limits their ability to confirm past infections in recovered individuals [

11]. Conversely, serological testing for immune antibodies is effective for epidemiological assessments and retrospective population surveys, as virus-specific immunoglobulin G antibodies remain in the body for an extended period [

12,

13,

14].

The variola virus, a member of the

Poxviridae family, is oval-shaped, approximately 350 nm × 270 nm in size, with a single, linear, double-stranded DNA and a genome length of approximately 186 kb [

15]. Poxviridae, which exclusively infects vertebrates, comprises eight genera. The variola virus belongs to the genus O

rthopoxvirus, which also includes cowpox virus,

Vaccinia virus, and monkeypox virus, which are capable of infecting humans. Notably, all poxviruses infecting vertebrates have common core antigens within the same genus, leading to their serological cross-reactivity [

16]. Immunity developed through vaccination with

Vaccinia virus, which belongs to the same

Orthopoxvirus genus as the variola virus, also confers an immune response to the variola virus. However, this immunity does not extend to viruses of different genera within the

Poxviridae family [

17]. Therefore, to address this gap in the literature, we sought to develop an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test using less lethal

Vaccinia virus antibodies against the bioterrorism pathogen variola virus in humans and assess the effectiveness of this method in evaluating the efficacy of smallpox vaccines and antibody therapies, monitoring outbreaks, and determining population-level antibody titers. This approach is aimed to advance the capacity to effectively respond to potential bioterrorism threats involving smallpox.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

The samples utilized in this study were acquired from 20 participants recruited through the “2021 Smallpox Vaccine Administration Training and First Response Personnel Vaccination Project.” Serum samples were collected at two-time points: 20 pre- and post-vaccination samples (4 weeks post-vaccination) as negative and positive controls, respectively. Furthermore, serum samples from 200 individuals born before 1978 (the year that smallpox vaccinations were stopped) and 100 individuals born thereafter were obtained from the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) National Biobank of Korea, collected through the “National Health and Nutrition Survey.” These samples were used to validate the performance of the developed ELISA test. The KDCA Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this study (IRB Number: 2021-06-08-3C-A), and all participants provided informed consent. Sample size calculation and power analysis were conducted to ensure the study was adequately powered to detect significant differences and validate the ELISA test performance.

2.2. Cells and Virus

Vero E6 (C1008) cells were procured from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, VA, USA) and cultured at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 using Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The Vaccinia virus Western reserve (WR) strain (VR-1354™) was obtained from the ATCC and utilized for the study. Vero E6 cells at a density of 1.4 × 107 cells were cultured in a T175 flask at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere using DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. After 1 day of culture, the medium was removed, and the stored Vaccinia virus (4 × 108 plaque-forming units [PFU]/mL) was applied at a concentration of 0.5 multiplicity of infection using approximately 3 mL of DMEM with 1% FBS and allowed to adsorb for 2 days. Following infection, the supernatant was removed, and the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Gibco) before adding 3 mL of DMEM with 1% FBS for three cycles of freeze-thawing. The dislodged cells were transferred to a 15-mL tube, and the virus-infected cells and culture medium were centrifuged at 700 × g for 8 minutes at 37°C to remove cell debris. The supernatant was then supplemented with 5 mL of DMEM and 1% FBS, aliquoted into 500 μL portions, and stored at −70°C until further use.

2.3. Plaque Reduction Neutralization Test

The plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) was conducted by mixing inactivated serum (heated at 56°C for 30 min) with 200 PFU of Vaccinia virus in equal volumes of 100 μL each, followed by neutralization at 30°C for 1 h. The neutralized Vaccinia virus was then inoculated into Vero E6 cells cultured in a monolayer in a prepared 12-well plate (Corning, Germany) and adsorbed for 1 h. After adsorption, the virus culture medium was removed. Furthermore, the overlay medium (1% Crystal Violet solution [200 mL], 37% formaldehyde [108 mL], 100% ethanol [25 mL], and distilled water [167 mL] to makeup the total volume to 500 mL) was added, followed by incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2. When the plaque formation reached approximately 1 mm in diameter (approximately 54 h later), the overlay medium was removed, and The plaques were washed with 1× PBS at room temperature. The washed plates were then stained with a crystal violet mixture for 30 minutes at 37°C, followed by another wash with 1× PBS. The neutralizing antibody titers (PRNT50) were determined as the reciprocal of the serum dilution that reduced virus plaques by ≥50% compared with that in the positive control (virus without neutralized serum).

2.4. Anti-Vaccinia Virus IgG Antibody Detection ELISA

Carbonate–bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.4; Sigma, MA, USA) was dissolved at one capsule per 100 mL to prepare the coating buffer. Recombinant A27L antigen expressed in Escherichia coli (MBS1141613; MyBioSource, CA, USA) was diluted to a final concentration of 0.2 μg/mL, and inactivated WR Vaccinia virus was diluted to 3 × 106 PFU/mL. They were individually dispensed into Immulon® 2HB 96-well microtiter ELISA plates (ImmunoChemistry Technologies, MN, USA) at 100 μL/well, sealed, and reacted for 24 h at 4°C. The samples were washed five times with 350 μL/well of 1× PBS-Tween20 (PBST). Subsequently, 5% skim milk (232100; BD Difco, NJ, USA) in 1× PBST was dispensed at 200 μL/well as a blocking buffer and reacted for 1 h at 37°C. Post-blocking, the samples were rewashed before adding diluted human serum in blocking buffer at 100 μL/well and incubating for 1 h at 37°C. Thereafter, the samples were washed and incubated with anti-Human immunoglobulin G (IgG) (H+L) and horseradish peroxidase conjugate (W4038; Promega, WI, USA) antibodies, diluted 1:10,000 in blocking buffer, at 100 μL/well for 1 h at 37°C.

Subsequently, the samples were washed, and 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) was added at 100 μL/well; the samples were then incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes for color development. Subsequently, TMB Stop Buffer (GenDEPOT, TX, USA) was added at 50 μL/well to quench the reaction, and a plate reader (SpectraMax® i3, Molecular Devices) was used to record the values at a wavelength of 450 nm.

2.5. Standardization of ELISA Results

Two methods were employed to standardize the variation in color development across plates. One method [

18] (Method 1) involved establishing a blank well in each plate, computing the average value, and subsequently adding three times the standard deviation to derive the ΔO.D._1 value. The alternative method [

19] (Method 2) involved subtracting the average O.D. value of normal human serum from the O.D. value of the sample to obtain ΔO.D._2. These approaches were used to normalize color development variations across plates.

2.6. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve Analysis

The diagnostic accuracy of standardized ΔO.D. values was assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis with the MedCalc version 22 software (Belgium). The ROC curve analysis was used to determine the optimal cut-off value based on the relationship between sensitivity and specificity. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) represents the overall accuracy of the diagnostic test, with larger AUC values indicating enhanced accuracy. Ranging from 0 to 1, the AUC value closer to 1 signifies perfect diagnostic capability, whereas a value of 0.5 denotes performance equivalent to random guessing. This methodology facilitated the establishment of a cut-off value for the specific diagnostic test, evaluating its utility through the computed sensitivity and specificity at this threshold.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the GraphPad Prism version 9 software. Significant differences between the groups were determined using an independent sample t-test. This statistical test compares the means of two independent groups to assess if they are significantly different from each other. This analysis was based on the assumption that the data were normally distributed and focused on evaluating differences in mean values. In the t-test outcomes, statistical significance was set at a p-value of <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using a two-tailed test, with data presented as mean ± standard deviation.

3. Results

3.1. Establishment of Standard Serum Using PRNT

The neutralizing antibody titers in the 20 smallpox vaccine recipients exhibited an increase, ranging between 4- and 64-fold in post-vaccination serum samples compared with that in pre-vaccination serum samples, indicating the development of neutralizing antibodies against the

Vaccinia virus WR strain. The ROC curve analysis, using antibody titers from pre- and post-vaccination sera in the neutralization experiment, demonstrated that setting the neutralizing antibody titer against

Vaccinia virus at ≥4 yielded 100% sensitivity and specificity (

Supplementary Table 1). Notably, all 20 pre-vaccination sera tested negative, whereas all 20 post-vaccination sera tested positive (

Supplementary Table 2). These findings confirmed that sera collected pre- and post-smallpox vaccination could serve as a gold standard for positive and negative results, forming the basis for ELISA.

3.2. Results of IgG ELISA using A27L Recombinant Antigen, a Common Antigen of Orthopoxvirus

Utilizing the A27L recombinant protein, a major antigen of Vaccinia virus, as the coating antigen in ELISA and diluting smallpox vaccine sera 50–800-fold in two-fold increments for indirect ELISA, we revealed increased OD450 values in post-vaccination serum samples compared with those in pre-vaccination serum samples. However, these values required adjustment owing to potential variations in OD450 across different experimental plates caused by factors such as the TMB solution reaction time, experimental temperature, and humidity. Consequently, the ΔO.D._1 and ΔO.D._2 adjusted values were higher in post-vaccination serum samples than in pre-vaccination serum samples.

Furthermore, during analysis using the serum dilution factor, the highest AUC value was observed at a 50-fold dilution using the ΔO.D._2 adjustment method. Considering a positive result for cut-off points > 0.4667, both sensitivity and specificity were 100% (

Supplementary Table 3), indicating the formation of smallpox vaccination-induced IgG antibodies against the A27L antigen. Therefore, the developed A27L IgG ELISA technique can measure the extent of IgG antibody formation against

Vaccinia virus following smallpox vaccination.

3.3. IgG Titer Determination using Vaccinia Virus ELISA

Vaccinia virus-infected Vero-E6 cells were lysed and used as inactivated antigens for ELISA. Smallpox vaccine sera were diluted 50–800-fold in two-fold increments for indirect ELISA. After adjusting OD

450, the ΔO.D._1 and ΔO.D._2 adjusted values of post-vaccination serum samples were higher than those of pre-vaccination serum samples. Additionally, during analysis using the serum dilution factor, the highest AUC value was observed at a 50-fold dilution using the ΔO.D._2 adjustment method. Considering a positive result for cut-off points > 0.0535, the sensitivity and specificity were 100% and 95%, respectively (

Supplementary Table 4), indicating the formation of smallpox vaccination-induced IgG antibodies against V

accinia virus. Therefore, the developed V

accinia virus IgG titer can reflect the extent of IgG antibody formation against

Vaccinia virus following smallpox vaccination.

3.4. Investigation of Smallpox IgG Titer Using Age-Specific Serum Samples from South Korea

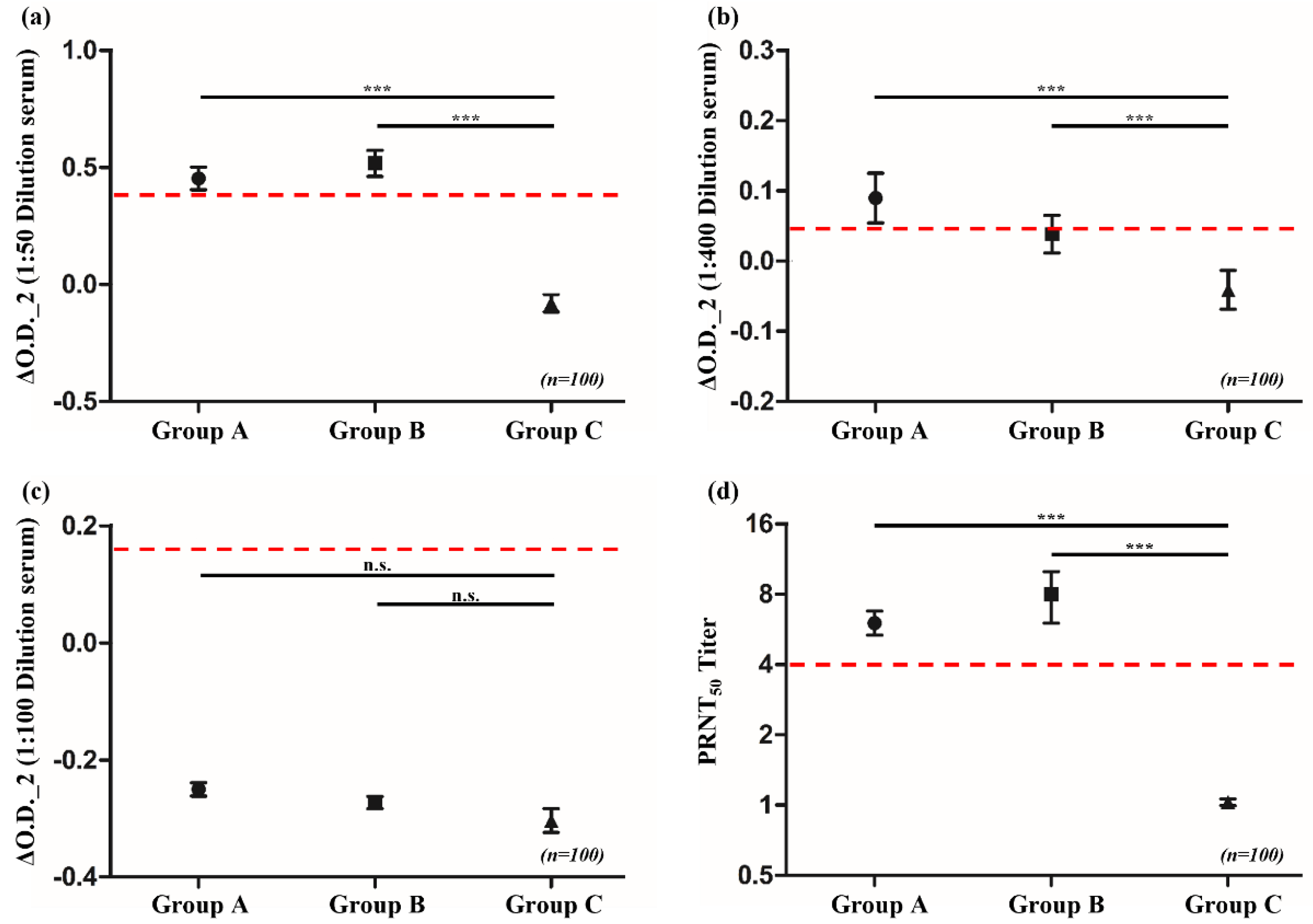

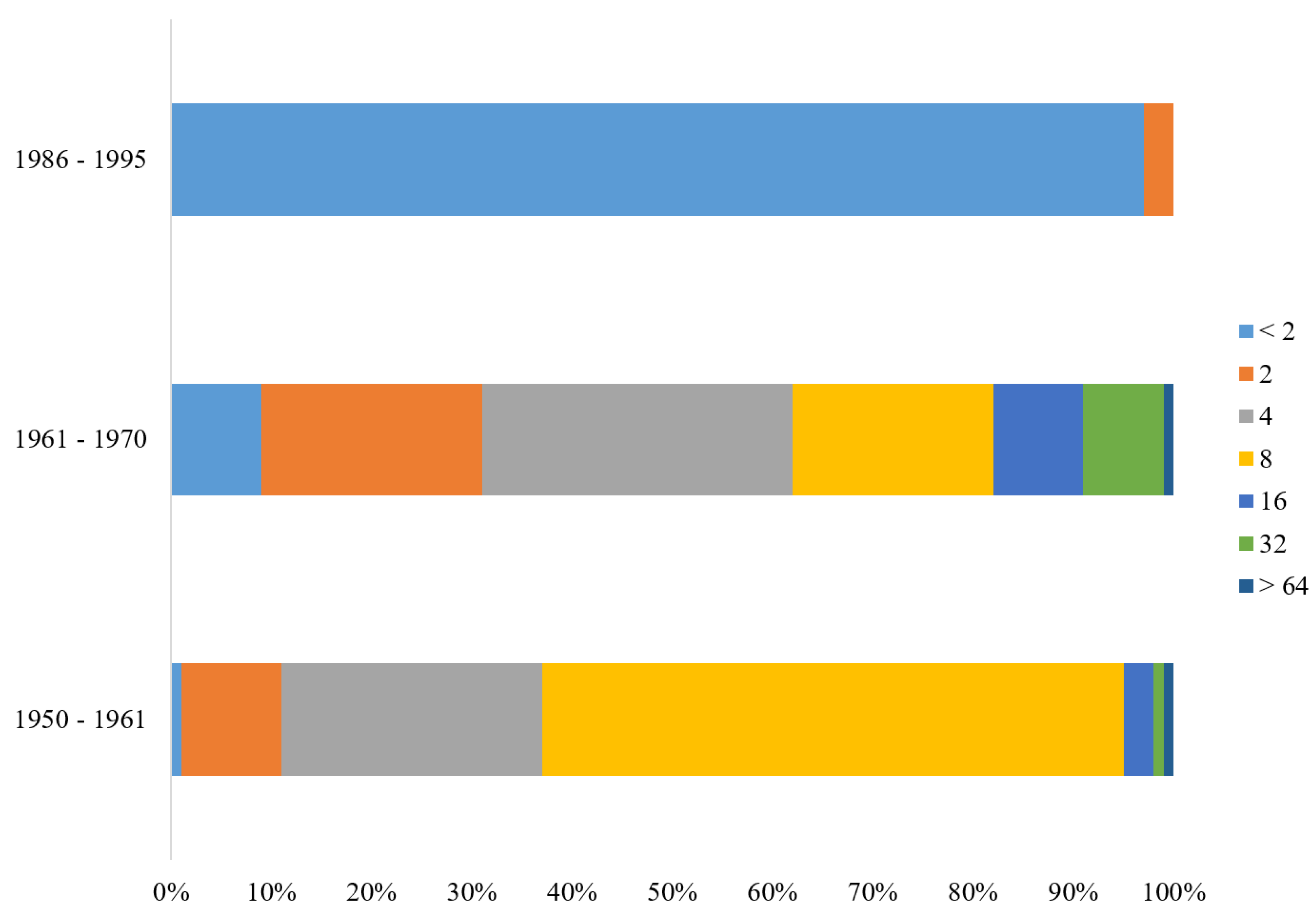

Serum samples from the general population, collected through the National Health and Nutrition Survey in South Korea, were categorized into groups based on birth years and smallpox vaccination status as follows: Group A comprised individuals born between 1950 and 1961, who were likely vaccinated owing to smallpox vaccination campaigns actively conducted until 1978 in South Korea; Group B comprised individuals born between 1962 and 1970, who had a reduced likelihood of vaccination as the disease was nearing global eradication and vaccination efforts were decreasing; and Group C comprised individuals born between 1986 and 1995, who were least likely to have been vaccinated following the worldwide eradication of smallpox and the cessation of routine smallpox vaccinations.

The PRNT results, with a cut-off for PRNT

50 values set at ≥8, helped to detect neutralizing antibodies in the serum of 63 and 38 individuals from Groups A and B, respectively. No serum with neutralizing ability was identified in Group C. Using the same serum samples for the ELISA analysis with A27L recombinant antigen, 33 and 43 individuals from Groups A and B, respectively, tested positive. In Group C, two individuals tested positive. When using

Vaccinia virus to detect IgG antibodies, 44, 35, and 12 individuals from Groups A, B, and C, respectively, tested positive. However, when testing for immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies using the same antigen, individuals from all groups tested negative (

Table 1). Statistical analysis of the ELISA results indicated that the averages for Groups A and B in the IgG ELISA were above the cut-off and that they significantly differed from the result of Group C, which was below the cut-off (

p < 0.0001). These results are consistent with those obtained from the PRNT (

Figure 1). The cut-off value of ≥8 for PRNT

50 was established based on ROC curve analysis, which validated its sensitivity and specificity in detecting neutralizing antibodies against

Vaccinia virus.

4. Discussion

The persistent threat of smallpox as a potential bioterrorism agent or biological weapon has caused South Korea to take proactive measures, including the accumulation of smallpox vaccine stockpiles and the development of vaccination plans for first responders and medical personnel. Furthermore, ensuring the scientific validation of vaccine efficacy, including the verification of antibody formation and their capacity to neutralize the virus, is imperative.

Herein, we present major findings from the serological analysis of smallpox vaccine efficacy using PRNT and ELISA analysis. In the absence of commercially available standard antibodies against Vaccinia virus, sera were strategically collected from 20 individuals before and after vaccination with the CJ strain (CJ50300) smallpox vaccine as part of the “2021 Smallpox Vaccine Administration Training and First Response Personnel Vaccination Project.” The PRNT helped to validate the presence of neutralizing antibodies in all post-vaccination serum samples by establishing pre-vaccination sera as negative controls and post-vaccination serum samples, collected 4 weeks after vaccination, as positive controls, thus validating their use as standard controls.

In this study, a cut-off value of >4 for PRNT50 was established as the criterion for successful antibody generation against Vaccinia virus. The optimal cut-off for the IgG ELISA method was determined through ROC curve analysis, using the PRNT results as the gold standard. The ELISA method demonstrated sensitivity and specificity of over 95% with the optimal cut-off, indicating the capability of the developed ELISA diagnostic method to discern the presence or absence of smallpox vaccine-induced antibodies.

In the IgG ELISA, using inactivated cell culture fluid from Vaccinia virus-infected cells and the recombinant A27L antigen expressed in E. coli as a coating antigen indicated that inactivated Vaccinia virus samples typically had higher average OD450. These results suggest that using Vaccinia virus as an antigen results in better reactivity, attributable to the presence of various surface proteins and the corresponding antibodies in the serum. This approach offers enhanced sensitivity; however, the presence of multiple proteins from the infected Vero E6 cells may decrease its specificity.

The results of analysis of 300 serum samples from the general population in South Korea, collected through the “National Health and Nutrition Survey Project,” aligned with those from the PRNT, confirming the persistent neutralizing capacity of the vaccine-induced antibodies. The absence of IgM antibodies in individuals of all groups indicated the lack of recent viral exposure or vaccination. These findings have crucial implications for public health, particularly regarding bioterrorism threats involving variola or related Orthopoxvirus species, highlighting the need for continued vigilance and the potential reevaluation of vaccination strategies.

The increased presence of neutralizing antibodies in individuals of Groups A and B, with no detectable neutralization in those from Group C, indicated a generational immunity gap, likely owing to the discontinuation of smallpox vaccination post-1978. The older individuals in Groups A and B likely received the vaccine, whereas the younger individuals in Group C, who were born post-vaccination cessation, did not have these antibodies. These observations highlight notable public health concerns, particularly regarding potential smallpox resurgence, as it indicates heightened vulnerability of the younger, unvaccinated population in the event of an outbreak.

A recent CDC study on residual immunity from smallpox vaccination in China revealed that individuals born before 1980 who were tested for the

Vaccinia virus Tiantan strain exhibited lasting neutralizing antibodies, suggesting long-lasting immunity and potential cross-immunity to related viruses in these individuals. Similarly, our findings from testing 300 individuals in South Korea showed a comparable pattern (

Figure 2), indicating sustained immunity in older individuals vaccinated against smallpox. These findings further highlight the significance of our findings, as they may help prepare against emerging

Orthopoxvirus threats. Furthermore, these findings highlight the substantial contribution of the developed ELISA method in monitoring vaccine-induced immunity and responding to potential bioterrorism threats [

20].

This study has some limitations. First, its focus on a specific population in South Korea may restrict the generalizability of its findings to other regions with different demographics or vaccination histories. Second, the relatively small number of patients, particularly in specific analyses involving 20 individuals, could affect the statistical robustness and broader applicability of the results. A longitudinal study may be required to obtain comprehensive insights into the persistence of antibodies over time and potential decline in their levels.

In conclusion, in this study, we developed and validated an ELISA method that can effectively detect

Orthopoxvirus antibody responses across various population groups. This method could be used to identify heightened antibody responses in specific population groups, such as men who have sex with men (MSM), who may be at higher risk for infections such as mpox due to the cross-reactivity of antigens and antibodies within the

Orthopoxvirus genus, which includes

Vaccinia and

Monkeypox viruses. This aligns with recent research trends, highlighting the utility of the ELISA method in assessing antibody responses to different virus strains [

21]. Furthermore, these results emphasize the importance of continuous monitoring and evaluation of

Orthopoxvirus species in public health and highlight the significance of developing tailored vaccination strategies for specific population groups, especially for the MSM community. Finally, our findings reinforce the need for adaptable and targeted approaches to disease prevention and control.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C. and H.Y.; methodology, H.C.; software, H.C.; validation, H.C. and S.L.; formal analysis, H.C. and S.L.; investigation, M.C.; resources, M.C.; data curation, H.C. and H.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, H.C.; writing—review and editing, H.Y. and Y.C.; visualization, H.C.; supervision, Y.C.; project administration, M.C.; funding acquisition, M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, grant number 6331-301-210-13”

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) Institutional Review Board (IRB Number 2021-06-08-3C-A, approved on August 27, 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Riedel, S. St. Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination. Proc. (Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent.) 2005, 18, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geddes, A.M. The history of smallpox. Clin. Dermatol. 2006, 24, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alibek, K.; Handelman, S. Biohazard: The Chilling True Story of the Largest Covert Biological Weapons Program in the World, Told from the Inside by the Man Who Ran It, 1st ed.; Random House: New York, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, G.J. Airborne micro-organisms: Survival tests with four viruses. J. Hyg. (Lond) 1961, 59, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, G. Infectious diseases. WHO gives a cautious green light to smallpox experiments. Science 2004, 306, 1270–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breman, J.G.; Henderson, D.A. Diagnosis and management of smallpox. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 1300–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Clercq, E. Cidofovir in the treatment of poxvirus infections. Antiviral Res. 2002, 55, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, R.; Leeds, J.M.; Tyavanagimatt, S.; Hruby, D.E. Development of ST-246® for treatment of poxvirus infections. Viruses 2010, 2, 2409–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofi Ibrahim, M.; Kulesh, D.A.; Saleh, S.S.; Damon, I.K.; Esposito, J.J.; Schmaljohn, A.L.; Jahrling, P.B. Real-time PCR assay to detect smallpox virus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 3835–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taub, D.D.; Ershler, W.B.; Janowski, M.; Artz, A.; Key, M.L.; McKelvey, J.; Muller, D.; Moss, B.; Ferrucci, L.; Duffey, P.L.; et al. Immunity from smallpox vaccine persists for decades: A longitudinal study. Am. J. Med. 2008, 121, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammarlund, E.; Lewis, M.W.; Hansen, S.G.; Strelow, L.I.; Nelson, J.A.; Sexton, G.J.; Hanifin, J.M.; Slifka, M.K. Duration of antiviral immunity after smallpox vaccination. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 1131–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crotty, S.; Felgner, P.; Davies, H.; Glidewell, J.; Villarreal, L.; Ahmed, R. Cutting edge: Long-term B cell memory in humans after smallpox vaccination. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 4969–4973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pütz, M.M.; Alberini, I.; Midgley, C.M.; Manini, I.; Montomoli, E.; Smith, G.L. Prevalence of antibodies to vaccinia virus after smallpox vaccination in Italy. J. Gen. Virol. 2005, 86, 2955–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amanna, I.J.; Carlson, N.E.; Slifka, M.K. Duration of humoral immunity to common viral and vaccine antigens. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 1903–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condit, R.C.; Moussatche, N.; Traktman, P. In a nutshell: Structure and assembly of the vaccinia virion. Adv. Virus Res. 2006, 66, 31–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McInnes, C.J.; Damon, I.K.; Smith, G.L.; McFadden, G.; Isaacs, S.N.; Roper, R.L.; Evans, D.H.; Damaso, C.R.; Carulei, O.; Wise, L.M.; et al. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Poxviridae 2023. J. Gen. Virol. 2023, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodroofe, G.M.; Fenner, F. Serological relationships within the poxvirus group: An antigen common to all members of the group. Virology 1962, 16, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, W.H.; Khan, N.; Mishra, A.; Gupta, S.; Bansode, V.; Mehta, D.; Bhambure, R.; Ansari, M.A.; Das, S.; Rathore, A.S. Dimerization of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein affects sensitivity of ELISA based diagnostics of COVID-19. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 200, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanakumar, A.V.; Thomann, P.; Candeias, J.M.; Ferreira, S.; Villa, L.L.; Franco, E.L. Use of the normalized absorbance ratio as an internal standardization approach to minimize measurement error in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for diagnosis of human papillomavirus infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Guo, L.; Li, Y.; Ren, L.; Nie, J.; Xu, F.; Huang, T.; Zhong, J.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Residual immunity from smallpox vaccination and possible protection from mpox, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Guo, M.; Huang, H.; Guo, C.; Wang, W.; Zhang, W.; Tang, H.; Wan, Y. Unexpectedly higher levels of anti-Orthopoxvirus neutralizing antibodies are observed among gay men than general adult population. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).