1. Introduction

According to SSC 2021 guidelines, the prognosis for patients with sepsis depends largely on a prompt institution of antibiotic therapy and adequate fluid intake. Appropriate selection of an antibiotic and its optimal dosage are of primary importance. It is therefore necessary to consider pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of a drug with a view to achieve optimal pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) indices. Sepsis and septic shock are the most common causes of acute kidney injury (AKI) [

1]. The pathomechanism of AKI involves hypoperfusion or compromised renal perfusion, inflammation, the release of proinflammatory cytokines and compromised function of renal cell mitochondria [

1,

2]. The implementation of continuous renal replacement therapy, apart from replacement or support for renal function in septic patients enables elimination of inflammatory mediators from the system, enhances stability of the circulatory system, improves organ perfusion, and also allows to gradually decrease plasma osmolality so as to avoid DDS (dialysis disequilibrium syndrome) [

2,

3] In order to increase toxin adsorption, polyethyleneimine-treated polyacrylonitrile filters (PAN PEI) were introduced into RRT. These filters are capable of adsorbing molecules of small and medium, but also large size. It was demonstrated that proinflammatory cytokines (tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukines (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and IL- 10) also undergo adsorption on this type of filter. Moreover, a negatively charged polyacrylonitrile membrane (PAN) makes it possible to bind positively charged molecules, including drugs. PAN filters treated with polyethyleneimine (PEI) generate weaker negative charges, reducing the production of bradykinin, but still making it possible to bind negatively charged drugs, such as heparin. [

4,28] With polysulfone filters (PS), during CRRT, elimination of molecules up to 30 kD is possible, while the capacity of these filters to eliminate cytokines is much smaller than with acrylonitrile filters [

4]. Linezolid is an antibiotic with a molecular weight of 337.35 Da. In normal pH it is an electrically neutral molecule [

5]. The efficacy of linezolid therapy depends on the time of its concentration remaining above MIC (T>MIC), as well as the ratio of area under the concentration-time curve during 24 hours to MIC (AUC24>MIC). [

6,

7]. Intensive therapy patients receiving standard linezolid doses (600 mg every 12 h) are reported to have inadequate plasma drug concentration, which implies worse prognosis. Owing to this fact, introducing increased drug doses into therapy has been considered. [

8] One of the causes which might dictate the need to change the dosing regimen of linezolid may be adsorption of the drug on the filter in patients subject to CRRT [

9,

10,

11]. In order to eliminate these doubts, we decided to assess the degree of linezolid adsorption on a range of filters: PS, PAN and PAN PEI in our study. To exclude the effect of plasma proteins on the degree of adsorption we compared solutions of bovine blood and 0.9% NaCl containing 600 mg of linezolid.

2. Materials And Methods:

The aim of the study was to assess the degree of linezolid adsorption for

3 types of filters: polysulfone PS AV1000S (Fresenius Medical Care, Germany), polyethyleneimine-treated polyacrylonitrile filter

AN69ST150 (Baxter International Inc., U.S.) and non-eneimine polyacrylonitrile filter

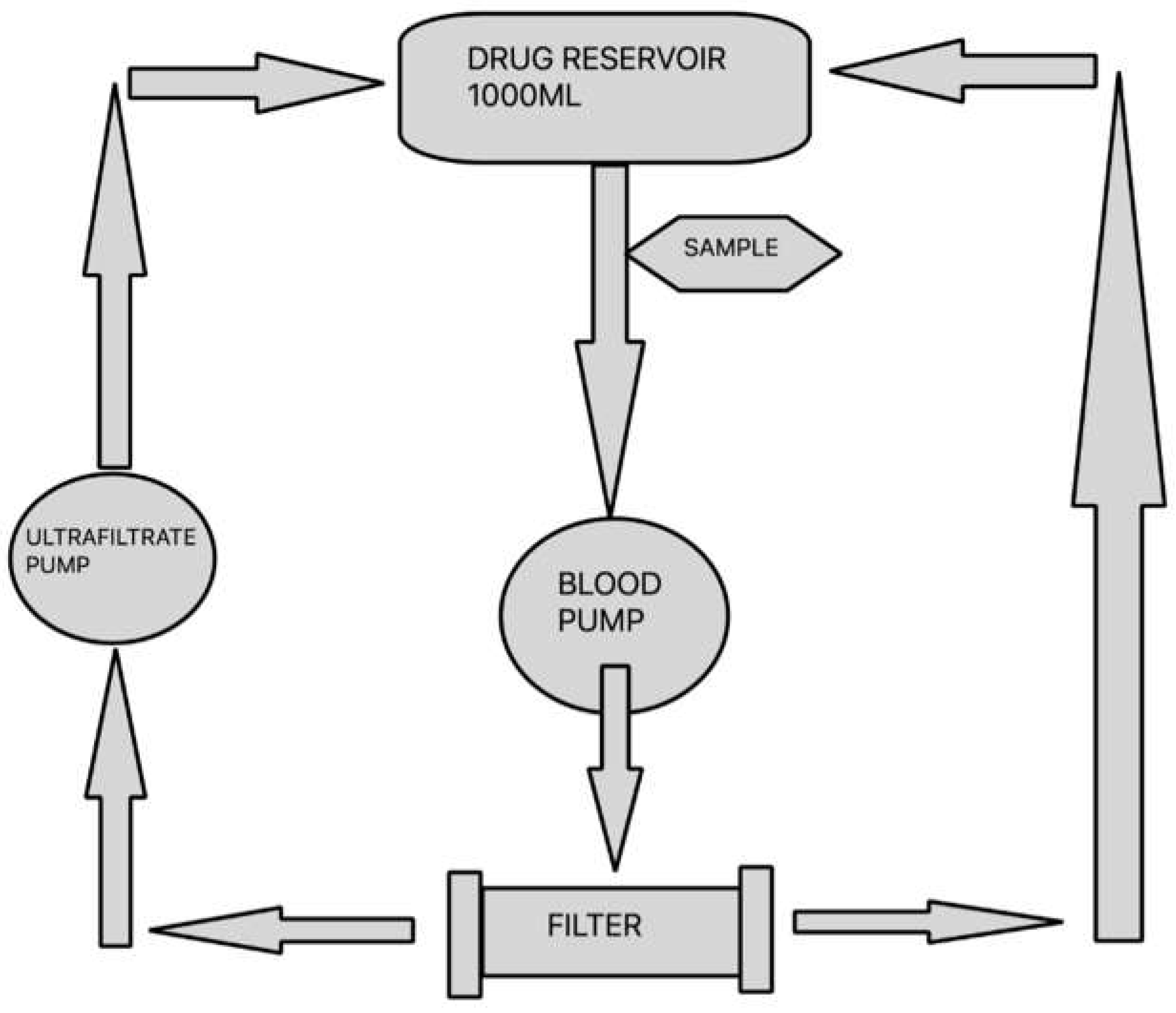

AN69HF M150 (Baxter International Inc., U.S.) using a continuous veno-venous hemofiltration (CVVH) circuit filled with blood or 0.9% NaCl. The test was carried out on a device used for CRRT in clinical setting (Multifiltrate, Fresenius Medical Care, Germany) with a filtration kit (MultiFiltrate Kit 7 HV-CVVH 1000 Fresenius). Filters PS AV1000S, AN69ST150 and AN69HF M150 with the surface areas of 1.8 m

2, 1.5 m

2 and 1.5 m

2, respectively, were inserted as presented in

Figure 1.

The total volume of blood compartment in the kit and filter equalled approximately 200 ml. The parameters of CVVH procedure were set at blood flow rate of 100 ml/min and ultrafiltration rate of 600 ml/h. Prior to the commencement of the study the circuit was filled with 0.9% NaCl without antibiotic. Subsequently, a reservoir was connected, containing bovine blood or 0.9% NaCl solution with antibiotic. In order to prevent the thrombosis of fresh bovine blood, 30 ml of 7.4% sodium citrate was added per each litre of blood immediately after it was obtained. The amount of linezolid used in the test was 600 mg, which is a standard single dose used in clinical practice. The drug was dissolved in a reservoir filled with bovine blood or 0.9% NaCl, respectively, to obtain the total volume of 1000 ml. After CVVH was started, the first 200 ml of fluid (0.9% NaCl solution) was removed. During the test, the ultrafiltration fluid was continuously returned to the reservoir containing blood or 0.9% NaCl with antibiotic. In order to maintain the temperature of recirculating fluid in the return line within the range of 35 to 37°C, a GUARDIAN 5000 OHAUS hotplate stirrer was used. For every filter type and solvent, 3 study cycles were run. Both from 0.9% NaCl and bovine blood solutions undergoing CVVH, 3 ml solution samples were collected from the pump port of the CVVH circuit at 0, 5, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90 and 120 minutes, starting with the moment of preparing the solutions. Two control tests were carried out with the aim to assess a spontaneous degradation of the drug. The solutions of 1000 ml total volume each were prepared, containing 600 mg of linezolid with bovine blood or 0.9% NaCl as solvents, respectively. Then the solutions were heated to 35-37°C and, maintaining stable temperature, were left without conducting CVVH. This was followed by collection of samples for analysis at time points as indicated above. The samples obtained from bovine blood solution were centrifuged at 3000 rotations/min immediately after collection, for the purpose of plasma separation. The obtained plasma was then frozen at –80°C and, still frozen, delivered to a laboratory in order to determine antibiotic concentration.

2.1. Drug Analysis

2.1.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Analytical standards for LIN (linezolid) and deuterium-labeled LIN-d3 (for use as an internal standard, IS) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany) and Toronto Research Chemicals (Toronto, ON, Canada), respectively. Formic acid, acetonitrile and water, all mass spectrometry grade, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Stock solutions (2 mg/ml for LIN and 1 mg/ml for IS) were prepared by dissolving the LIN and IS in methanol. Working solutions of the drugs for calibration curves (0.5 µg/ml, 2.5 µg/ml, 5 µg/ml, 25 µg/ml, 50 µg/ml, 100 µg/ml, 250 µg/ml, 500 µg/ml for LIN and 50 µg/ml for IS) were prepared by diluting the standard solutions in methanol.

2.1.2. Chromatography

The analysis was performed with an Acquity UPLC system I-class Plus coupled with a Xevo TQ-XS tandem mass spectrometer (MS/MS) (Waters, Milford, USA). Chromatographic separation of both analytes was performed on an Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column (Waters, Milford, USA) (100 × 2.1 mm) with a particle size of 1.8 µm that was maintained at 35°C. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water (phase A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (phase B), and the pump was set for gradient elution as follows: 0-0.75 min – 10% phase A; 0.75-2.25 min – linear gradient to 100% phase A; 2.25-3.00 min – linear gradient to 10% phase A. The duration of the entire analysis was 5.50 min, the injection volume was 1 µl, and the autosampler temperature was 15°C. Detection was performed in positive ion mode and MRM mode, and the transitions were set to 338.17m/z→296.10m/z for LIN and 341.17m/z→297.10m/z for IS. The basic mass spectrometry parameters were as follows: ionization mode – positive electrospray; desolvation gas – nitrogen; desolvation temperature 350°C; desolvation gas flow – 1000 L/h; source temperature 150°C; collision gas – argon; collision energy (for both compounds) – 17eV; cone voltage – 26 V; capillary voltage – 0.5 kV; dwell – 0.025 s; delay – 0.003 s.

For our experiments, we used two types of matrices: plasma and 0.9% NaCl. Both types of samples for LIN determination were prepared according to a method developed in our laboratory. As we were using mass spectrometry, we chose not to use a classical extraction procedure and used only a protein precipitation technique.

The 100 µl of samples were thawed at room temperature (the samples for calibration curves were spiked with 10 µl of LIN), and mixed in a vortex mixer at 1000 rpm for 5 s. Next, 600 µL of acetonitrile (with 5 µg/mL of IS for calibration and 50 µg/mL of IS for experimental samples) was added for protein precipitation, and the samples were mixed at 3000 rpm for 10 s. After this, all samples were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C.

At this point, to avoid contamination of the LC-MS/MS (the concentrations of LIN in this experiment were more than 10 times higher than concentrations achieved in clinical practice), the experimental samples (plasma and 0.9% NaCl) were subjected to an additional 10-fold dilution with water, unlike the calibration standards. This extra dilution was achieved by transferring 20 µL of the supernatant into a clean probe and diluting it with 180 µL of LC/MS water (thus, the results from the analysis of the experimental samples were later multiplied by 10 to calculate the actual results). Finally, all samples (from the experiment and for calibration) were filtered through a 0.22 µm nylon syringe filter (13 mm in diameter) into chromatographic total recovery vials and injected into the chromatographic system.

The analytical method was validated according to Markowska et al. 2021 [29]. During the validation procedure, we used samples without any additional dilution procedure for the experimental samples that was described above (our experimental samples were diluted approximately 60 times, thus we performed only matrix effect test for NaCl). Thus, we could measure the matrix effect precisely, and this method can also be used to analyze LIN in clinical practice. The following parameters were determined: linearity (eight-point curve prepared and analyzed three times at one-day intervals), accuracy, precision (repeatability/intra-day precision and intermediate precision/inter-day precision, determined by preparing analyte concentrations at the three QC points and the LLOQ, which were all within the range of the standard curve; this was done three times at one-day intervals in six replicates together with the IS), LLOQ, selectivity, recovery (six replicates of LLOQ and HQC points were prepared, in which the analytes were added to the plasma either before or after extraction), matrix effect (LIN and IS were added to the phase obtained following extraction of an empty matrix in six replicates for LLOQ and HQC points and compared the signal of LIN and IS added to a mixture of water and ACN), carry-over (six replicates of HQC and six blank samples were prepared, and the blank sample was analyzed after each HQC sample analysis), and stability (without a long-term freeze-thaw stability test, but including freeze-thaw stability, autosampler stability, working standard and stock stability, and sample processing-temperature stability, always comparing to freshly prepared samples; all these tests were performed by preparing analyte concentrations at the three QC points and the LLOQ, which were all within the range of the standard curve; this was done three times, at specified time intervals, in six replicates together with IS). The acceptance criteria were based on Markowska et al. 2021.

The lowest limit of quantitation (LLOQ) equaled 0.05 μg/ml ± 0.005 (the signal-to-noise ratio was not lower than 6:1). To prepare a calibration curve, plasma free from LIN was used, which was obtained from blood drawn from clinically healthy subjects. The curve included 8 points at 0.05, 0.25, 0.50, 2.5, 5.0, 10.0, 25.0, and 50.0 μg/mL, of which 3 points served for QC: low quality control (LQC – 0.25 μg/ml), medium quality control (IQC – 2.5 μg/ml), and high quality control (HQC – 50.0 μg/ml). The LIN calibration curve was linear. The coefficient of determination, r2, was above 0.99 for all the calibration curves. Differences between particular control points were 1.68–4.91% for accuracy, and the coefficient of variation for precision was within 1.75–7.23% for individual points. The specificity of the method was determined via an analysis of six samples of plasma free from LIN, which showed no significant peaks at the retention time of LIN and IS (2.20 min). Also, there were no “ghost” peaks after injection of six replicates of HQC (with IS) and six blank samples, which indicates that the chromatographic system did not carry over any analytes. With this method, the total recovery was 95% ± 8.9 for LIN and 97.1% ± 6.8 for IS. LIN was stable after 24 h in an autosampler at 15°C (the increase/decrease in the concentration in the QC samples was ± 10.45-13.21%), after 3 h at sample processing temperature (± 2.38-9.26%), during the 3 cycles of thawing and freezing after 24, 48, 480 h (± 4.1-14.8%), and in the prepared stock and working standards stored in a refrigerator (4 °C) for 7 consecutive days (±1.14-14.12%). The matrix, which was plasma and 0.9% NaCl, did not demonstrate any significant effect on the signal from the detector, which was verified by analyzing the signal from the matrix with and without the LIN standard, or by comparing the signal after adding the same concentration of LIN to water and to the matrix (the increase/decrease was ± 7.35-14.52%).

2.2. Statistic

Descriptive statistics were performed. The normal distribution of continuous variable was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The differences in mean drug/NaCl adsorption and mean drug/blood adsorption between STL, ML and PSL at different time points (0, 5, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120) were determined using one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons by Tukey’s post-hoc test. The differences in mean drug/NaCl adsorption and drug/blood adsorption during time for STL, ML, PSL were measured using repeated measures ANOVA with multiple comparisons by Tukey’s post-hoc test. A p-value <0.05 was considered to be significant. The data analysis was conducted using Statistica (data analysis software), version 13. http:// statistica. io TIBCO Software Inc., Krakow, Poland (2017).

3. Results

The analysis of the drug concentration in the control solutions did not show a decrease in concentration in any case. This is a reason to conclude that the antimicrobial studies did not undergo spontaneous degradation in the test solution used for CVVH. In all blood samples albumin values did not differ significantly from one another and equalled 410.11, 412.6 and 393.79.

The greatest and significant adsorption was noted for PAN PEI membrane (

Table 1). In the samples with bovine blood a significant difference was demonstrated on the filter PAN PEI over time between the starting value and each time point (p<0.05). The value at 120 min (T120) constituted 73% of the initial value (

Table 2).

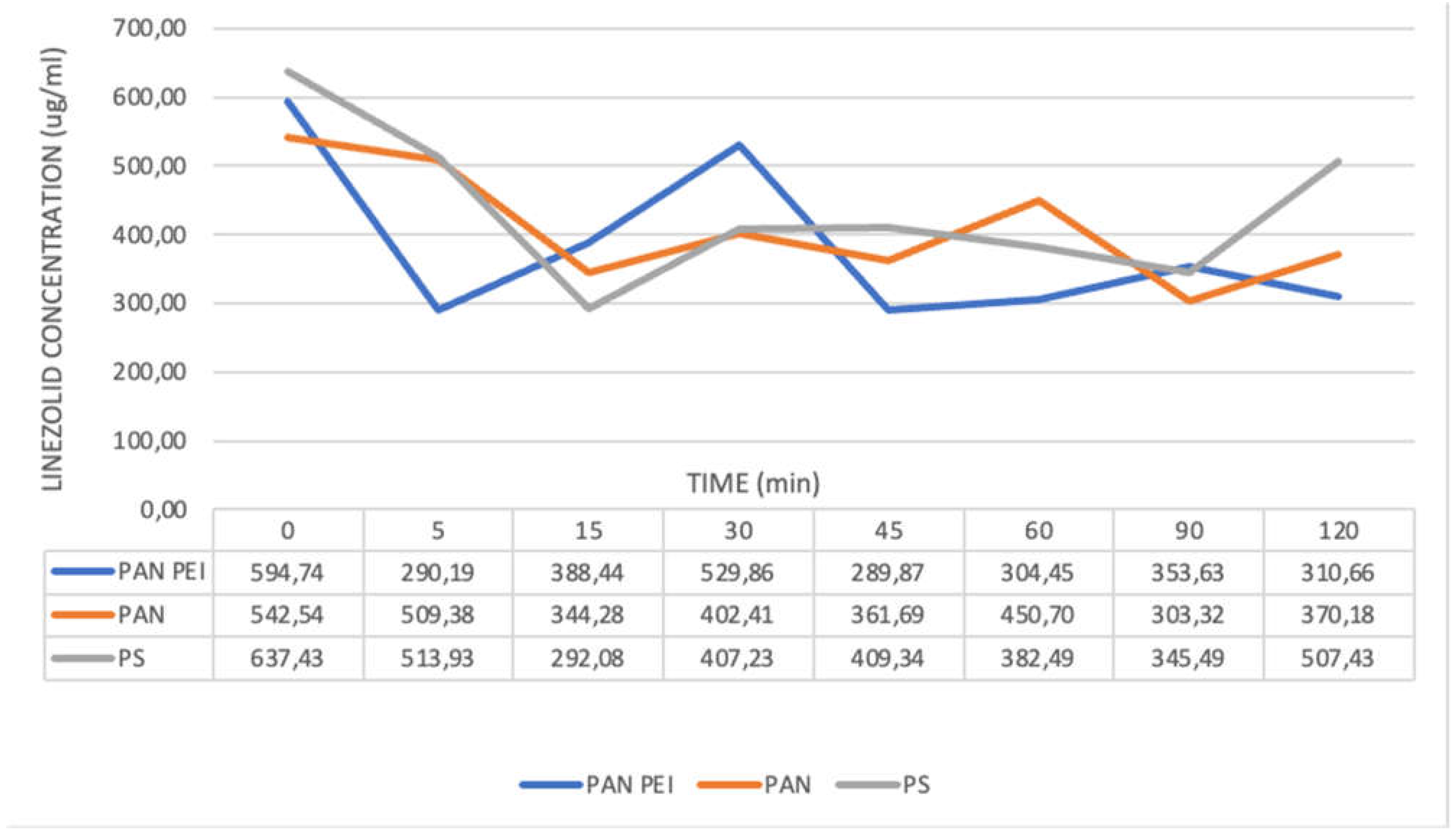

The lowest drug concentration for PAN membrane during CVVH with blood solution was seen at 60 minute of the experiment (

Figure 2). The concentration values gradually increased in two subsequent samples, while failing to reach the initial level: the difference between the starting concentration and the endpoint was 15% (

Table 2).

For PAN PEI membrane the drug concentration fell after 5 minutes of the test and remained at a relatively stable, low level till the end of the test. For PS membrane the concentration of linezolid in blood solution was the lowest at 45 minute, then increased gradually and at endpoint did not differ significantly from the starting value.

The level of plasma protein binding for linezolid is approximately 30%, [13] and that is why CVVH was conducted also for the solution of linezolid in 0.9% NaCl. For solutions with 0.9% NaCl the greatest and significant adsorption was demonstrated for PAN PEI membrane [

Table 3].

The lowest concentration of antibiotic was seen in 5. and 45. minute. At endpoint at 120. minute the difference between the concentration at 0. and 120. minute was 48% and it was statistically significant (

Figure 3) (

Table 7).

For PAN filter only at 90. minute there was a considerable fall in concentration (p<0.05) to 303.32 ug/ml, which then increased at 120 minute to 370.18 ug/ml, with the initial concentration of 542.54 ug/ml. For PS filter a significant decrease in concentration was demonstrated between 15. to 90 minute, while the endpoint value was 507.43 ug/ml and was lower than the initial value of 637.43 ug/ml by 20%. (

Table 4)

In Anova+Tukey post hoc test a statistically significant variability of area under the curve (AUC) was demonstrated between PAN PEI vs. PS filters and PAN PEI vs PAN filters in blood samples. (

Table 5) (

Table 7). The lowest AUC values were found on PAN PEI filter in blood samples. The samples with 0.9% NaCl also showed the lowest AUC for PAN PEI filters, but here the values between the filters were more closer than in blood samples. (

Table 6) (

Table 7).

Table 5.

Statistics One way Anova + Tukey post hoc - bovine blood AUC.

Table 5.

Statistics One way Anova + Tukey post hoc - bovine blood AUC.

| Group |

Significance |

P value |

| PAN PEI vs PS |

YES |

p<0.001 |

| PAN PEI vs PAN |

YES |

p<0.001 |

| PS vs PAN |

NO |

p=0.653 |

Table 6.

Statistics One way Anova + Tukey post hoc - 0.9% Natrium Chloratum AUC.

Table 6.

Statistics One way Anova + Tukey post hoc - 0.9% Natrium Chloratum AUC.

| Group |

Significance |

p value |

| PAN PEI vs PS |

NO |

|

| PAN PEI vs PAN |

NO |

|

| PS vs PAN |

NO |

|

Table 7.

AUC values on different types of filters in blood and 0.9% NaCl samples.

Table 7.

AUC values on different types of filters in blood and 0.9% NaCl samples.

| AUC(0-t) values in blood samples |

AUC(0-t) values in 0.9% NaCl samples |

| Membrane type |

Mean

(mg*min/l)

|

SD |

Membrane type |

Mean

(mg*min/l) |

SD |

| PAN PEI |

43627.02 |

1532.896 |

PAN PEI |

42933.61 |

5979.0174 |

| PS |

54475.07 |

2423.964 |

PS |

47929.42 |

5048.3368 |

| PAN |

55784.54 |

1020.386 |

PAN |

45734.66 |

9467.0715 |

4. Discussion

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of many antibiotics may change in critically ill patients with multiorgan failure. Changes in antibiotic concentrations are particularly hazardous in septic patients, in whom drug concentrations between doses may fall below MIC, or the ratio AUC:MIC may be too low. [18] This phenomenon is more pronounced, when patients in septic shock developing renal failure and need renal replacement therapy. In patients who are hemodynamically unstable, in septic shock still the preferred option is continuous renal replacement therapy CRRT.

In order to obtain better therapy effects in patients requiring CRRT the right dose of antibiotic and the regimen accounting for altered pharmacokinetics of the drug (PK) must be selected. However, the studies on the changed antibiotic pharmacokinetics during CRRT are scarce. [17] The factors which affect PK/PD of the drug during CRRT include: preserved residual diuresis, drug distribution volume (the greater it is, the smaller elimination of the drug during CRRT), extrarenal clearance, the level of drug binding to proteins, duration and parameters of CRRT, blood flow rate, type of filters [15]. Adsorption of drug on filter depends on electrical charge of the membrane as well as the drug, material of the membrane, its structure, the degree of drug binding to plasma proteins. [17,19]

Linezolid is an antibiotic of small molecular weight (337 Da) and a neutral electrical charge. Its volume of distribution accounts for the total body water content of 40–50 L and, owing to its moderately lipophilic nature, it undergoes minimal changes during sepsis. Its plasma half-life ranges between 3.4 to 7.4 hours. Approximately 30% of the drug binds to plasma proteins, while about 70% constitutes unbound fraction. [14,17,20]

The renal clearance of linezolid is approximately 30%. However, in patients with sepsis whose life is threatened, the drug pharmacokinetics may change considerably, particularly in patients with AKI undergoing CRRT. The clearance of linezolid during CRRT differed depending on the kind of therapy, and for CVVH (the method used in our study) it was 1.2-3.2 L/h (the total drug clearance being 6.4-14.8 L/h). [14,15] The efficacy of linezolid action depends on time (T>MIC) and ratio of area under the concentration-time curve during 24-hour period to MIC (AUC0-24/MIC). [14,22]

Our in vitro study was conducted on three types of filters commonly used in clinical practice: PS, PAN and PAN PEI. We used bovine blood a model most closely imitating in vivo conditions. Albumin values for all the solutions were similar: 410.11 mg, 412.6 mg and 393.79 mg, respectively. In order to exclude possibilities of drug elimination other than its adsorption on dialysis filter membrane, there were more tests carried out, with the drug dissolved in 0.9% NaCl solution which was subjected to CVVH. Also, a control test without CVVH was conducted to exclude spontaneous drug degradation. A significant adsorption was obtained for PAN PEI filter, both in samples containing bovine blood plasma, as well as 0.9% NaCl.Taking into account AUC values obtained in our study for blood samples, a statistically significant difference in values was found for PAN PEI filters.

The review article by Villa G et al. [14] mentions the surface area of the filter as a significant factor: the greater it is, the higher drug clearance occurs. Carcerelo et al. [24] demonstrated that similar values of total extracorporeal drug clearance are obtained for PAN filter and for PS filter with the surface area almost twice greater than that of filter with PAN membrane. The aim of our study was to determine and compare drug adsorption regardless of the filter surface area, but in relation to its type. This is why we used filters with the greatest available adsorption surface area which were also similar in size. The review article from 2016 [14] points out that, in septic patients with AKI undergoing CRRT, only one publication found an optimal AUC/MIC ratio for pathogens with dedicated MIC>4mg/L. With regard to PK/PD of linezolid in patients treated with CRRT, Villi G. et al. [14] demonstrated a decrease in min. concentration, while max. concentration was similar to or even higher than those mentioned in literature. Bandin-Vilar et al. [27] reported clearance of linezolid of 30% in patients treated with RRT, with subtherapeutic drug concentrations more common than supratherapeutic values.

The publication by Sartori et al. [16] was based on the analysis of linezolid adsorption on polysulfone filters (PS). The results of this analysis proved that there was a decrease in drug concentration during the first 10 minutes, and then its concentration increased both in saline and blood samples - a rebound phenomenon occurred. A similar phenomenon can be observed in our study involving the use of polysulfone membranes, although it is delayed (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). In a publication by Meyer et al. [26], PK parameters were comparable for patients undergoing CVVH involving the use of PS filters for healthy individuals.

In an article by Hiraiwa T et al. [

10] a sharp fall in linezolid concentration was reported between 0 and 15 minute on three types of filters, including AN69 ST (PAN PEI) and PS. PEI on PAN membrane in filters AN69ST changes adsorption properties of the membrane, increasing adhesion of some complement components, β2macroglobulines, and also decreasing the negative charge of the membrane. PAN PEI hydrogel structure allows adsorption not only on the surface of the membrane, but also within it, which translates into its greater ability to remove cytokines [19,24,25]. The analysis of the results we obtained shows that the addition of PEI to PAN membrane had a significant effect on the adsorption of linezolid, both in 0.9%NaCl and blood solutions.

It seems that using PAN PEI filters plays an important role here, as they are negatively charged; multiple sulfone groups attract water, forming hydrogel structure, which is characterised by high diffusion permeability. The chemical composition of AN69ST (PAN PEI) membrane enables adsorption of proteins with low molecular weight, and a high water content in hydrogel makes the polymer chains easily accessible [21]. The addition of PEI to PAN filters reduces the negative charge of the filter, which may translate into decreased adsorption of drugs with a positive charge. [28]

A publication by Matthew S. Dryden reports administration of linezolid in the dose of 600 mg every 12 hours, resulting in linezolid concentration >MIC90 for sensitive pathogens maintained until another dose administration, with the threshold values observed between 10 and 12h for Staphylococcus infection. [18] There are a number of factors which may affect the PK/PD ratio for linezolid, leading to subtherapeutic drug concentrations. These risk factors include CRRT and adsorption of antibiotic on a filter. There is a need for further research in order to reach a consensus on a modification of linezolid therapy in CRRT patients which would minimise the risk of obtaining subtherapeutic doses. Even short periods of subtherapeutic concentrations of a time-dependent antibiotic, such as linezolid, may lead to a therapeutic failure, particularly for less sensitive pathogens, and contribute to a growing bacterial resistance. Developing new recommendations requires further research in the clinical setting.

A. Corona et al. emphasizes that, with the need to adjust antibiotic dosage in patients subject to CRRT, the category of an antibiotic – time-dependent vs. concentration-dependent must be considered, as it will define the benefits from modifying the treatment strategy. For a time-dependent antibiotic, a continuous infusion or prolonged administration of the drug will prove more beneficial. For concentration-dependent antibiotics a single dose of the drug should be increased. [15].

5. Conclusions

Institution of CRRT may cause changes in antibiotic pharmacokinetics through various mechanisms, including drug adsorption on a filter. In our study, adsorption of linezolid on three types of membranes: PS, PAN and PAN PEI was compared. Adsorption of linezolid on PAN PEI filter was found to be significant and it may be of importance in the clinical setting. Both data from our study and literature led us to conclude that increased linezolid dosage should be considered, e.g. by introducing shorter intervals between the doses once CRRT is started; alternatively, by doubling the dose of the antibiotic as CRRT is commenced or when the filter is replaced. In vivo studies are mandatory to resolve the issue.

6. Limitations

Duration of the test was shorter than the recommended interval between linezolid doses (12 h), which will fail to correspond to the changes in PK/PD of linezolid. Further research should be conducted involving drug dosage in the clinical setting and the frequency of dialysis filter changes.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kulkarni AP, Bhosale SJ. Epidemiology and Pathogenesis of Acute Kidney Injury in the Critically Ill Patients. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020;24(Suppl 3):S84-S89. [CrossRef]

- Jundong Xu. A review: continuous renal replacement therapy for sepsis-associated acute kidney injury}, All Life 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hellman T, Uusalo P, Järvisalo MJ. Renal Replacement Techniques in Septic Shock. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(19):10238. Published 2021 Sep 23. [CrossRef]

- Lee KH, Ou SM, Tsai MT, et al. AN69 Filter Membranes with High Ultrafiltration Rates during Continuous Venovenous Hemofiltration Reduce Mortality in Patients with Sepsis-Induced Multiorgan Dysfunction Syndrome. Membranes (Basel). 2021;11(11):837. Published 2021 Oct 29. [CrossRef]

- Herrmann DJ, Peppard WJ, Ledeboer NA, Theesfeld ML, Weigelt JA, Buechel BJ. Linezolid for the treatment of drug-resistant infections. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2008 Dec;6(6):825-48. PMID: 19053895. [CrossRef]

- Pea F, Furlanut M, Cojutti P, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of linezolid: a retrospective monocentric analysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(11):4605-4610. [CrossRef]

- MacGowan AP. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile of linezolid in healthy volunteers and patients with Gram-positive infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003 May;51 Suppl 2:ii17-25. PMID: 12730139. [CrossRef]

- Taubert M, Zander J, Frechen S, Scharf C, Frey L, Vogeser M, Fuhr U, Zoller M. Optimization of linezolid therapy in the critically ill: the effect of adjusted infusion regimens. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017 Aug 1;72(8):2304-2310. PMID: 28541510. [CrossRef]

- Zheng J, Sun Z, Sun L, Zhang X, Hou G, Han Q, Li X, Liu G, Gao Y, Ye M, Wang H, Yu K. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Linezolid in Patients With Sepsis Receiving Continuous Venovenous Hemofiltration and Extended Daily Hemofiltration. J Infect Dis. 2020 Mar 16;221(Suppl 2):S279-S287. PMID: 32176792. [CrossRef]

- Hiraiwa T, Moriyama K, Matsumoto K, Shimomura Y, Kato Y, Yamashita C, Hara Y, Kawaji T, Kurimoto Y, Nakamura T, Kuriyama N, Shibata J, Komura H, Morita K, Nishida O. In vitro Evaluation of Linezolid and Doripenem Clearance with Different Hemofilters. Blood Purif. 2020;49(3):295-301. Epub 2020 Jan 29. PMID: 31995801; PMCID: PMC7212696. [CrossRef]

- Joannidis M. Continuous renal replacement therapy in sepsis and multisystem organ failure. Semin Dial. 2009 Mar-Apr;22(2):160-4. PMID: 19426421. [CrossRef]

- Zoller M, Maier B, Hornuss C, et al. Variability of linezolid concentrations after standard dosing in critically ill patients: a prospective observational study. Crit Care. 2014;18(4):R148. Published 2014 Jul 10. [CrossRef]

- Stalker DJ, Jungbluth GL. Clinical pharmacokinetics of linezolid, a novel oxazolidinone antibacterial. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42(13):1129-40. PMID: 14531724. [CrossRef]

- Villa G, Di Maggio P, De Gaudio AR, Novelli A, Antoniotti R, Fiaccadori E, Adembri C. Effects of continuous renal replacement therapy on linezolid pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamics: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2016 Nov 19;20(1):374. PMID: 27863531; PMCID: PMC5116218. [CrossRef]

- Corona A, Veronese A, Santini S, Cattaneo D. “CATCH” Study: Correct Antibiotic Therapy in Continuous Hemofiltration in the Critically Ill in Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy: A Prospective Observational Study. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022 Dec 13;11(12):1811. PMID: 36551468; PMCID: PMC9774802. [CrossRef]

- Sartori M, Loregian A, Pagni S, De Rosa S, Ferrari F, Zampieri L, Zancato M, Palú G, Ronco C. Kinetics of Linezolid in Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy: An In Vitro Study. Ther Drug Monit. 2016 Oct;38(5):579-86. PMID: 27391086. [CrossRef]

- Jang SM, Infante S, Abdi Pour A. Drug Dosing Considerations in Critically Ill Patients Receiving Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy. Pharmacy (Basel). 2020 Feb 7;8(1):18. PMID: 32046092; PMCID: PMC7151686. [CrossRef]

- Matthew S. Dryden, Linezolid pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in clinical treatment, Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, Volume 66, Issue suppl_4, May 2011, Pages iv7–iv15. [CrossRef]

- Onichimowski D, Nosek K, Ziółkowski H, Jaroszewski J, Pawlos A, Czuczwar M. Adsorption of vancomycin, gentamycin, ciprofloxacin and tygecycline on the filters in continuous renal replacement therapy circuits: in full blood in vitro study. J Artif Organs. 2021 Mar;24(1):65-73. Epub 2020 Oct 8. PMID: 33033945; PMCID: PMC7889537. [CrossRef]

- Hashemian SMR, Farhadi T, Ganjparvar M. Linezolid: a review of its properties, function, and use in critical care. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018 Jun 18;12:1759-1767. PMID: 29950810; PMCID: PMC6014438. [CrossRef]

- Thomas M, Moriyama K, Ledebo I. AN69: Evolution of the world’s first high permeability membrane. Contrib Nephrol. 2011;173:119-129. Epub 2011 Aug 8. PMID: 21865784. [CrossRef]

- Fang J, Chen C, Wu Y, Zhang M, Zhang Y, Shi G, Yao Y, Chen H, Bian X. Does the conventional dosage of linezolid necessitate therapeutic drug monitoring?-Experience from a prospective observational study. Ann Transl Med. 2020 Apr;8(7):493. PMID: 32395537; PMCID: PMC7210126. [CrossRef]

- Pea F, Furlanut M, Cojutti P, Cristini F, Zamparini E, Franceschi L, Viale P. Therapeutic drug monitoring of linezolid: a retrospective monocentric analysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010 Nov;54(11):4605-10. Epub 2010 Aug 23. PMID: 20733043; PMCID: PMC2976143. [CrossRef]

- Carcelero E, Soy D, Guerrero L, Poch E, Fernandez J, Castro P, et al. Linezolid pharmacokinetics in patients with acute renal failure undergoing continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52:1430–5. [CrossRef]

- Doi, K., Iwagami, M., Yoshida, E., & Marshall, M. R. (2017). Associations of Polyethylenimine-Coated AN69ST Membrane in Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy with the Intensive Care Outcomes: Observations from a Claims Database from Japan. Blood Purification, 44(3), 184–192. [CrossRef]

- Meyer B, Kornek GV, Nikfardjam M, Karth GD, Heinz G, Locker GJ, Jaeger W, Thalhammer F. Multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of linezolid during continuous venovenous haemofiltration. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005 Jul;56(1):172-9. Epub 2005 May 19. PMID: 15905303. [CrossRef]

- Bandín-Vilar E, García-Quintanilla L, Castro-Balado A, Zarra-Ferro I, González-Barcia M, Campos-Toimil M, Mangas-Sanjuan V, Mondelo-García C, Fernández-Ferreiro A. A Review of Population Pharmacokinetic Analyses of Linezolid. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2022 Jun;61(6):789-817. Epub 2022 Jun 14. Erratum in: Clin Pharmacokinet. 2023 Sep;62(9):1331. PMID: 35699914; PMCID: PMC9192929. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Yuqiang, Huang, Xiaohong, Yang, Yanan, Lei, Zhenlin, Chen, Qingan, Guo, Xu, Tian, Jia and Gao, Xiaoxin. “Clinical analysis of AN69ST membrane continuous venous hemofiltration in the treatment of severe sepsis” Open Medicine, vol. 18, no. 1, 2023, pp. 20230784. [CrossRef]

- Markowska P, Procajło Z, Wolska J, Jaroszewski JJ, Ziółkowski H. Development, Validation, and Application of the LC-MS/MS Method for Determination of 4-Acetamidobenzoic Acid in Pharmacokinetic Pilot Studies in Pigs. Molecules. 2021; 26(15):4437. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).