1. Background

Extracorporeal blood purification techniques (ET) such as hemodialysis and hemofiltration have been used successfully for several decades with the aim of replacing renal function in critically ill patients with kidney failure. In the last years the concept of extracorporeal organ support (ECOS) has emerged to describe all forms of therapies where blood is extracted from the body and processed in different circuits with specific devices and techniques [

1].

Critical status, sepsis and ET are all factors that may influence the ideal pharmacokinetic / pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) targets of many drugs, including antimicrobial agents [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. The potential impact of ET on concomitantly administered drugs is not fully understood, and the lack of data limits the availability of evidence-based recommendations for antibiotic (ABs) dosing. Moreover, there are several age-related factors that influence the PK properties of drugs administered to pediatric patients.

Therefore, the “one dose fits all” approach is clearly unfeasible and the implementation of a tailored approach in critical pediatric patients, especially if on ET, may play a key role. To this aim, therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) represents a useful tool that could help intensive care physicians to adjust drug dosing in order to reach specific PK/PD targets [

7]. To date, TDM seems to be the only safe and effective way to optimize antimicrobials treatments in critically ill patients. In fact, this approach could allow to improve clinical outcome reducing the development of microbial resistance [

8].

CytoSorb

®(CS) (CytoSorbents Corporation, NJ, USA) is a novel synthetic hemoadsorption device approved by the European Union (conformité européenne – CE) for extracorporeal cytokine removal in 2011 [

9]. CS cartridges can be easily integrated in extra-corporeal circulation circuits (Continuous Kidney Replacement Therapy - CKRT, Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation - ECMO, Cardio-Pulmonary Bypass - CPB), and can be used in stand-alone modality (hemoadsorption). The cartridge contains biocompatible polystyrene divinylbenzene copolymer beads capable of removing molecules of medium molecular weight (according to their size exclusion mechanism) by using a combination of hydrophobic or ionic interactions as well as hydrogen bonding [

9,

10]. In the pediatric settings, the device has showed an excellent safety profile and potential beneficial clinical effects as adjuvant therapy helping to control overwhelming inflammatory conditions [

11,

12]. However, one critical issue that should be taken into account when administering anti-microbial therapies alongside to CS cartridge utilization, is the augmented drug clearance, that exposes patients to the risk of poor clinical outcomes and the development of ABs resistance as a result of ABs sub-therapeutic levels. Actually, no data are available on the effect of CS on ABs dosage in the pediatric field [

13,

14]. The aim of this monocentric study was to evaluate the impact of CS on plasma levels of different ABs commonly used in a pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This prospective observational study was conducted between February 2021 and March 2023 in the PICU of Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital, Rome, Italy. The study protocol was submitted to the local Ethics Committee and approved in January 2021 (protocol n° 144). Written informed consent was obtained from patient’s next of kin or guardian. Data presented were collected as part of a hospital audit on the safety of hemoadsorption with CS in critically ill children.

2.2. Data collection and characteristics of treatment

Data were recorded using an electronic case report form (eCRF). Data collection at admission (enrolment) included demographics, comorbidities, etiologies of infection, site of infection, primary diagnoses, Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction 2 score (PELOD-2) [

15], vasoactive inotropic score (VIS) [

16], Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) stage [

17], and Acute Liver failure [

18,

19]. Septic shock was defined according to the International Pediatric Consensus Conference and treated following the latest therapeutic guidelines [

20]. AKI and its stage of severity was defined according to the KDIGO guidelines [

17]. Acute Liver failure (ALF) was defined as the abrupt onset of coagulopathy and biochemical evidence of hepatocellular injury, leading to rapid deterioration in liver cell function [

19]. In order to evaluate the impact of CS on infectious status, several clinical parameters including C-Reactive Protein (CRP), procalcitonin (PCT) and white blood cells (WBC) were evaluated in a time dependent manner during the first three days of hemoadsorption, and after 7 and 14 days from the beginning of CS treatment. Furthermore, we assessed any new onset of infections at 7 and 14 days from the start of hemoadsorption. Finally, mortality in PICU, mortality at 28 days, and the length of PICU stay were also recorded.

All critically ill children received ET based on a hemoadsorption treatment with CS in combination with CKRT. CKRT indications were AKI and /or fluid overload and/or electrolyte imbalance. CS was performed as a rescue therapy in children with proven or suspected diagnosis of septic shock, in the contest of inadequate response to standard therapy or refractory shock associated with multiple organ failure in the context of a cytokine storm syndrome.

2.3. CKRT and hemoadsorption with CytoSorb.

An 8 or 11.5 hemodialysis catheter was inserted into a central vein (internal jugular or femoral) as appropriate, according to the children size. CKRT was performed with a standard hemofilter (AN69ST) combined with CS continuous veno-venous hemodiafiltration - CVVHDF or in continuous veno-venous hemofiltration - CVVH modality, using pre-filter reinfusion and an effluent dose of 2000 ml/h/1.73 m2. Blood flow was set based on the patient’s body weight (5-10 ml/kg/min for patients below 10 Kg, 5 ml/kg/min between 10 and 20 Kg, 100-150 ml/min for patients above 20 Kg). CS was inserted into the CKRT circuit in series with the hemofilter in a post-filter position; both the CKRT circuit and CS was flushed with a saline solution and primed with blood. Anticoagulation was managed with regional citrate anticoagulation with a starting citrate dose of 2.5 mmol/L and with an aim of circuit calcium of 0.3-0.4 mmol/l and patient calcium of 1.1-1.25 mmol/l or with unfractioned heparin with a continuous infusion of 10–20 UI/kg/h to achieve a post-filter activated clotting time (ACT) between 160 and 180 sec. CS therapy was continued on the basis of the clinical course as well as laboratory surrogates (lactate concentration, and metabolic status including pH). CS was changed every 24 hours as recommended by the manufacturer.

2.4. Blood samples protocol

TDM of four ABs (meropenem, ceftazidime, amikacin and levofloxacin) was carried out throughout the whole study duration in each patient. Measurements for TDM have been performed from patient’s blood samples (venous central line or arterial line). In

Table 1, the dosing regimens used for each AB are given.

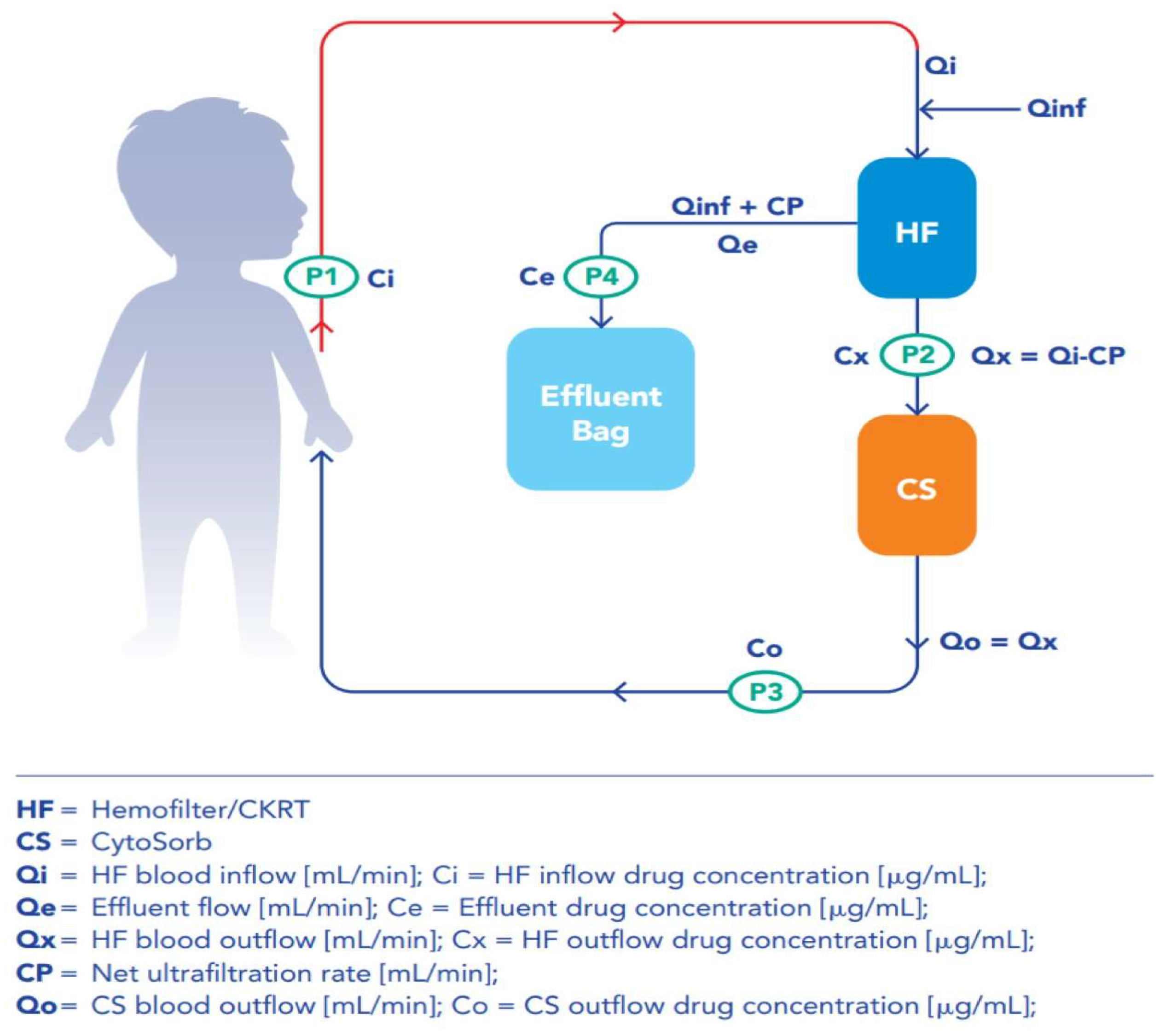

In addition, in order to quantify the impact of the ET and the individual CKRT and CS contributions to Abs removal, 3 sampling points for the determination of drugs concentration were identified along the circuit: hemofilter outflow (= CS cartridge inflow), CS cartridge outflow and effluent line (

Figure 1). All samples for TDM were collected during a drug steady-state. For time-dependent ABs, Concentration trough (

Cmin) was measured before the beginning of next infusion in patient blood sample (P1); drug concentration was also determined for each ABs in blood samples simultaneously collected at each circuit point (P2, P3, P4). For concentration-dependent ABs, concentration max (C

max) and C

min, along with concentration at each circuit point, were evaluated by collecting blood samples 1 h after the initiation of a bolus infusion and before the administration of next dose, respectively. For time dependent ABs, blood sampling was repeated for two to three consecutive days, whereas concentration-dependent Abs samples were collected for two consecutive days. All blood samples were collected at the same time, irrespective of any change in the CS cartridge.

2.5. Clearance and mass removal calculations.

In order to analyze the effects of ET on the circulating drug levels, we considered the following parameters: ET Drug Clearance (

CL [ml/min]), expressed as the total amount of blood purified from the administered drug

per unit of time; and ET Mass Removal (

MR [µg/min]), calculated as the amount of drug removed over a unit of time. These parameters were used to calculate the Total ET and the individual CKRT and CS contribution to the ABs removal from bloodstream. CL and MR were calculated as follow in

Table 2.

We have translated the mean clearance from milliliter per minutes (ml/min) to liter (L) per hours (h): L/h and the mean mass removal from microgram per minutes (µcg/min) to milligram (mg) per hour (h): mg/h. The variables defining both parameters are reported in

Figure 1. For each AB, CL and MR were calculated at C

min. For the concentration-dependent ABs, both parameters were additionally calculated at C

min and C

max. For each AB we calculated the Total Extracorporeal Clearance (CL

ET) during the study period. CL

ET was assessed considering the individual contribution of CKRT and CS. Residual renal clearance CL

ren was measured by urine collection during the monitoring period. For anuric patients CL

ren was assumed to be null. Data related to CS’s impact on overall clearance was also classified according available

in vitro and

in vivo data using similar cutoffs as low (<30%), moderate (30–60%), or high (>60%) removal potential [

2].

2.6. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

TDM of four ABs (meropenem, ceftazidime, levofloxacin, amikacin) was performed in the Laboratory of Metabolic Diseases and Drug Biology at Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital in Rome.

For amikacin determination, liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry analysis were performed using an UHPLC Agilent 1290 Infinity II coupled to a 6470 Mass Spectrometry system (Agilent Technologies, Deutschland GmbH, Waldbronn, Germany) equipped with an ESI-JET-STREAM source operating in the positive ion (ESI+) mode. The software used for controlling this equipment and analyzing data was MassHunter Workstation (Agilent Technologies). The assay calibration curve was linear for amikacin and ranged from 1.28 to 58.8 µg/mL. Each batch of patients’ analysis included both Low- and High-Quality Controls (QCs) at fixed concentrations of 3.70 and 39.4 µg/mL, respectively. Calibrators, QCs and patients’ samples were analyzed using a CE/IVD validated LC-MS/MS kit (FloMass Antibiotics) provided by B.S.N. S.r.l (Biological Sales Network, Castellone, CR, Italy). Both the LC-MS/MS analytical kits included calibrators and QCs, and were further validated according to European Medicines Agendy (EMA) guidelines for bioanalytical methods validation [

21].

The UHPLC apparatus used for determination of meropenem, ceftazidime and levofloxacin levels consisted of an Agilent 1290 Infinity II system equipped with a quaternary pump, a degassing line, a thermostated auto sampler, a column oven and a 10 μl cell DAD (Diode Array Detector) (Agilent Technologies). Specifically, analysis of meropenem and ceftazidime levels were carried out by using a CE/IVD validated HPLC kit (antibiotics in serum/plasma) provided by Chromsystems (Chromsystems Instruments & Chemicals GmbH). QCs and patients’ samples were prepared according to manufacturer’s instructions. Data were acquired and processed by using OpenLAB Workstation (Agilent Technologies). Levofloxacin levels were determined by using a previously described method [

22]. Briefly, 100 μl of plasma were spiked with 50 μl of Butylparaben (used as internal standard, IS) and vortexed for 5 s; thereafter, mixture was extracted with 250 μl of acetonitrile, mixed for 30s and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 9 min. Supernatant was collected and evaporated under liquid nitrogen flow. Reconstitution was achieved with 100 μl of 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES) buffer. The chromatographic run was realized on a Kinetex® 2.6 μm EVO C18 100 × 2.1mm column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) thermostated at 50 °C with 0.5 ml/min flow. Analytes were discriminated by gradient elution. Mobile phase A consisted of Na

2HPO

4 *2H

2O 0.35% in H

2O (adjusted to pH 7 with H

3PO

4) and mobile phase B was acetonitrile. Total running time was 8 min and the injection volume was 5 μl. Levofloxacin concentrations were calculated from a linear calibration curve ranging from 1.0 to 25.0 µg/mL. For each analyzed compound, samples with drug concentrations above the higher calibration point were diluted and re-analyzed again.

2.7. Statistical analysis

For descriptive data, continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR), according to their distribution; categorical variables are expressed as count (n) or percentage (%). All statistical analyses were performedusing XLSTAT excel advanced statistical software (Version 2022.3, Addinsoft Inc, Paris, France) and NCSS 2021 Statistical Software (NCSS, LLC. Kaysville, Utah, USA).

3. Results

We enrolled 10 pediatric patients who received hemoadsorption with CS and CKRT between October 2021 to March 2023. In

Table 3 demographic and clinical characteristics on admission including etiology and source of infections are reported.

3.1. CytoSorb and CKRT clearance and mass removal

In

Table 4, the hemofilter and CS mean values ± standard deviation (SD) for clearance and mass removal are reported. Mean clearance and mass removal for the antimicrobials analyzed in this study positively indicated drug removal by both devices, except for meropenem. In fact, CS clearance and mass removal mean values for meropenem were both negative (

Table 4). Average clearance was higher than 2 L/h only for levofloxacin. Mean values of mass removal and clearance showed a lower impact of CS compared to just the hemofilter, whilst for levofloxacin clearance and mass removal values were significantly affected by CS at both Cmin and Cmax levels.

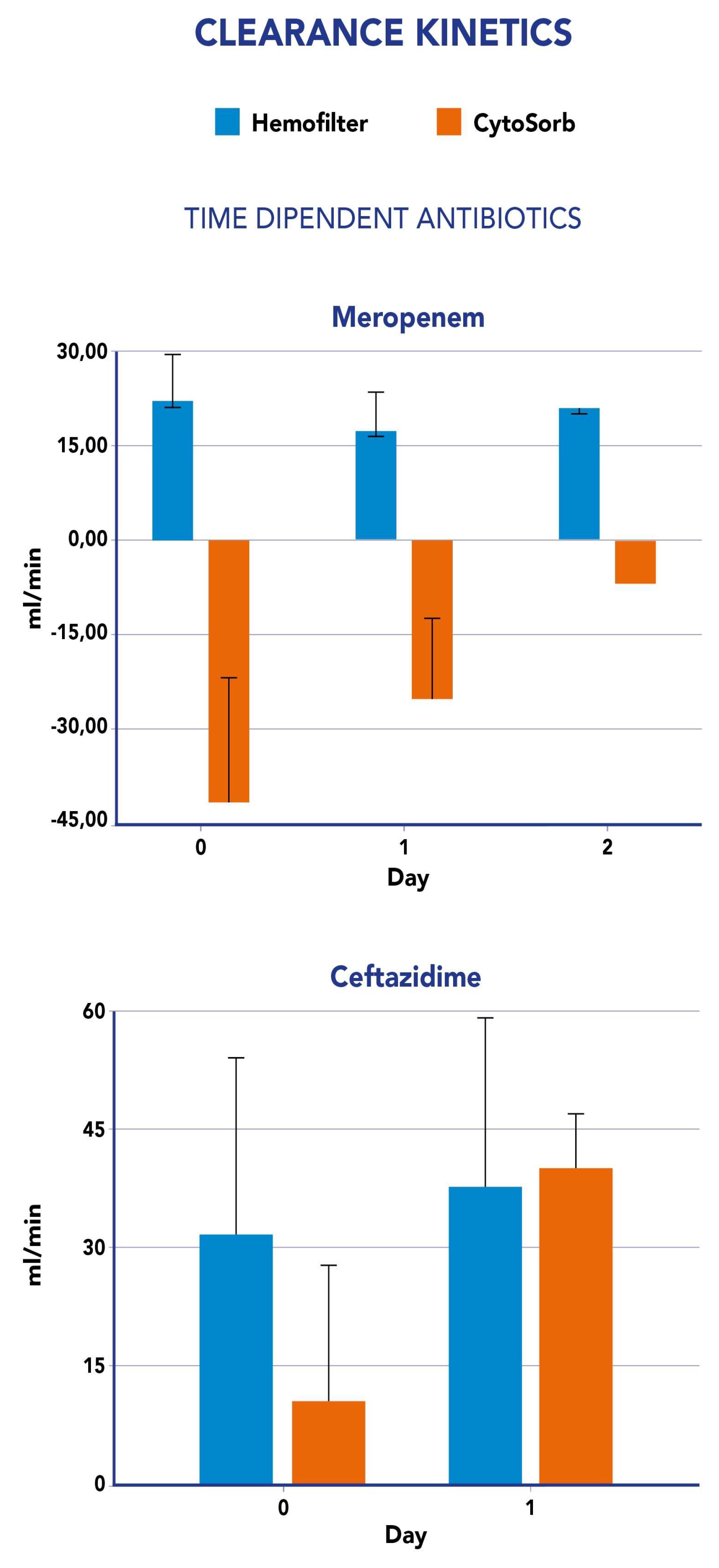

Clearance values measured for both CS and CKRT were not constant during the study period . In fact, by analyzing the impact of CS on ET clearance, we observed an increase, in most cases, although meropenem constantly showed negative values (

Figure 2). Similarly, CS-mediated clearance for ceftazidime showed an increase from the first day to the second day of study period (

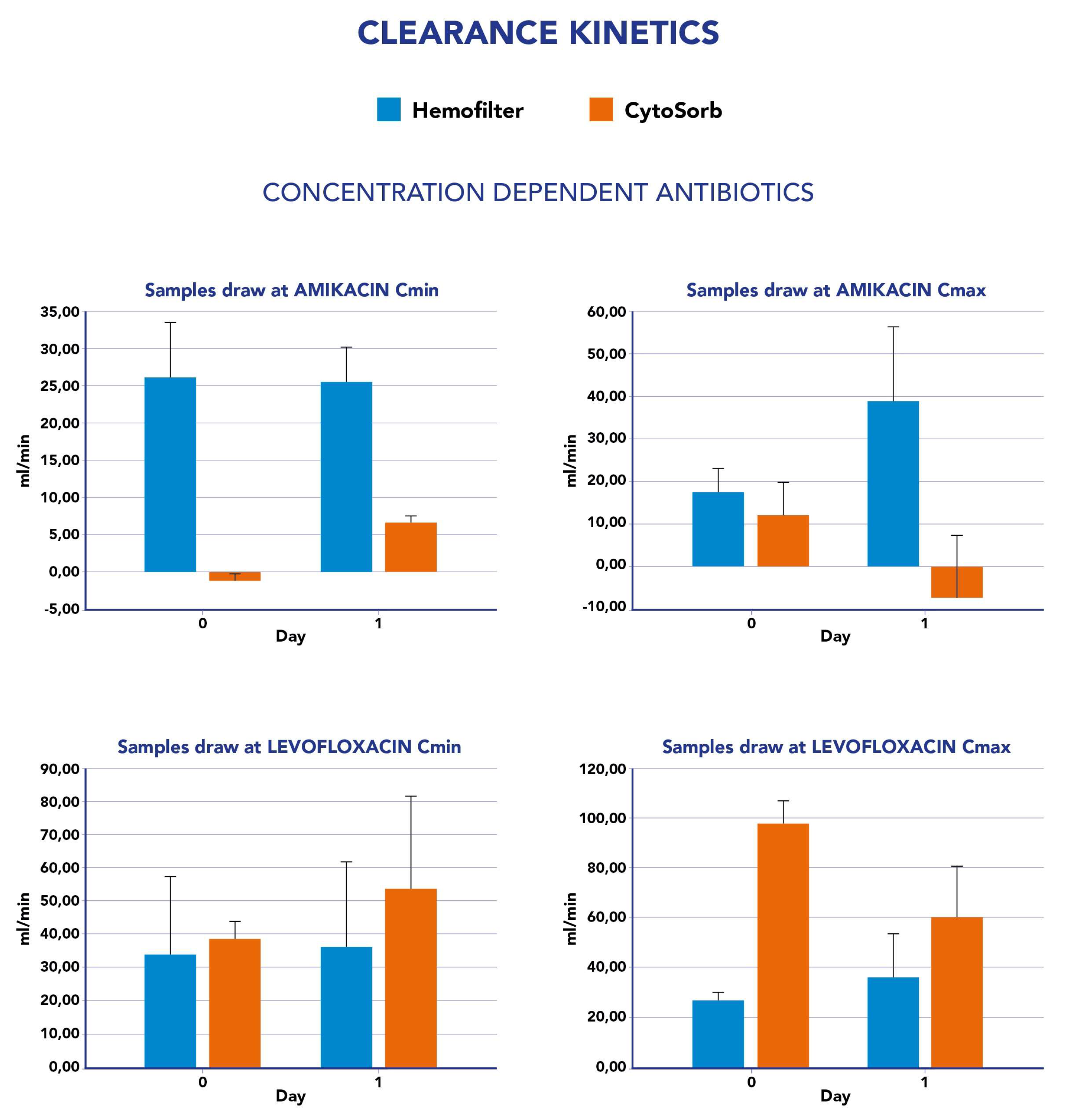

Figure 2). For the concentration-dependent antibiotics amikacin and levofloxacin, we observed an increase in clearance value at Cmin from the first to the second day whereas a reduction was reported in the same period at Cmax measurements (

Figure 3).

Supplementary Figure 3 reports the impact of the hemofilter on CL

ET for each antibiotic. CS was associated to an increase in total clearance for all tested drugs expect for meropenem (-57%). The impact was considered low for amikacine (6-12%), moderate for ceftazidime (43%) and moderate to high for levofloxacine (52-72%).

3.2. Clinical outcomes and AUC during ET treatments

Table 5 reports on the time course of CRP, PCT and WBC during the first 3 days of hemoadsorption treatment and at 7 and 14 days after the end of the hemoadsorption. We observed new onset infections in 3 out of 10 patients at day 7 and in 1 out of 10 patients at 14 days. In our cohort, median PICU length of stay was 11.5 days (8.75 – 20.25) and PICU and 28 day mortality was 50%.

A positive microbiological culture was observed in 5 out of 10 patients (including 4 patients with a positive hemoculture and 1 patient with a positive bronco-alveolar culture). As shown in Figure 5 , ABs plasma levels achieved the pharmacodynamic target attainment (PTA) at all time-points of the study period on the basis of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) found. For patients with suspected septic shock and a negative culture, we evaluated the hypothetical PTA on the basis of clinical scenario, antibiotic treatment and EUCAST breakpoint MIC values. As reported in

Supplementary Table 6, antibiotic plasma levels were adequate enough to reach the PK/PD targets used in this study [

23].

4. Discussion

In this study we report for the first time the assessment of PK/PD alteration due to CS and CKRT treatment in pediatric critically ill patients, considering the individual contributions from the different ET used. In particular, we focused on 4 frequently used ABs with different PK/PD characteristics. Our data confirm the insignificant

in vivo removal of meropenem by the CS cartridge as previously reported [

24]. Furthermore, we observed a negative value of CS clearance for meropenem suggesting an increase in ABs levels at the CS outflow as a consequence of potential desorption. This mechanism has already been advocated by Schneider et al., in particular for beta-lactams. Perrottet N. et al [

26], have confirmed rapid efflux of Ganciclovir from red blood cells into plasma, through permeation across the red blood cell membrane: this phenomenon could also play a role during blood filtration by CKRT and during hemoadsorption.

For amikacine, we observed low removal both at the Cmax and Cmin measurements as already reported

in vitro by Reiter [

27]. We also observed a low impact of CS on ceftazidime removal. No previous data have been reported for this antibiotic, but only for drugs belonging to the same class (third generation cephalosporine). Finally, among the ABs tested, levofloxacine resulted in the most removal by the CS, confirming that lipophilicity was the only pharmacokinetic factor moderately associated with CS clearance

25 [

25]. The Abs kinetics during the study period were more stable with the hemofilter contribution in comparison to the CS cartridge suggesting that a steady state concentration during treatment was easily obtained with CKRT whereas it may be more difficult to be achieved with the CS column due to the cartridge exchange, the kinetics of saturation in the first hours of treatment and the concentration dependent effect in the removal of target molecules. Thus, in most of the categories of the ABs studied in our population, CS’s clearance resulted in inferior results to that of the hemofilter. These data are very important, as higher doses of ABs have been suggested to guarantee PTA in patients undergoing CKRT [

7] but clear indications for CS are not available. Indeed, this empirical approach may allow for adequate dosing even during hemoadsorption with CS cartridge without the need for further implementation for any additional risk of antibiotic removal.

We only found microbiological isolates in 5 of 10 patients. In these patients we evaluated the area under the curve (AUC) and PTA for different classes of antibiotics, and found that PTA was achieved at each time point of the study period. The PK/PD targets adopted in this study were CSS = 4-6 X MIC for meropenem and ceftazidime, C

max =10 X MIC for levofloxacin and the ratio

Cmax/MIC >8 for amikacin [

23]. Conversely, the incidence of new onset infections at 7 and 14 days during hemoadsorption showed a low incidence in our cohort (3 out of 10 at 7 days and 1 out of 10 at 14 days).

Our study presents some limitations. Firstly, we studied the pharmacokinetics of four antibiotics in a small cohort, therefore our data need to be confirmed in larger populations. Secondly, we monitored antibiotics levels irrespective of the CS changes, however, some authors [

27,

28] reported a higher removal rate of drug in the first hours of hemoadsorption treatment due to saturation of the drug binding site on the absorber surface. Conversely, our study presents several strengths: we have assessed the role of a hemofilter and CS in extracorporeal clearance during routine clinical practice and not in a clinical trial. To this aim, we have collected blood samples at different points of the hemoadsorption circuits, analyzing the different contribution of hemofilter and CS cartridge to antibiotic removal from the bloodstream. Moreover, for the first time we have evaluated the impact of the CS cartridge on the capability of each administered antibiotic to reach the previously established PK/PD targets of efficacy.

5. Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the clearance of meropenem, ceftazidime, levofloxacin and amikacin in critically ill children undergoing CKRT in combination with CS hemoadsorption. We found that the application of CS was associated with a lower clearance rate for meropenem, ceftazidime and amikacin but not for levofloxacin compared to the hemofilter. In the studied population, no significant clinical burden was observed neither on ongoing infections nor on the occurrence of new infections, as the result of appropriate antibiotic coverage during treatments. However, more evidence is needed to confirm our data in a larger pediatric population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S4. Table S6.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.B., B.G., I.G., A.T.M.; methodology, G.B., B.G., I.G., M.M, S.M.; software, B.G., S.C., R.S., J.C.C.B.; validation S.M., F.S.T., P.B., T.C.; formal analysis G.B., C.M., L.V., Gi.B., J.C.C.B.; investigation G.B., M.M. J.C.C.B..; resources, C.C., B.G.; data curation C.M., G.Bi., A.C., R.L., L.V., Gi.B.; writing—original draft preparation G.B., C.M; writing—review and editing, G.B. G.Bi. I.G., B.G., R.S., P.B., L.V, A.T.M.; supervision, S.M., F.S.T., I.G., B.G, T.C, A.T.M., C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding has been received for this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by IRCCS Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital in July 2019 (N376).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)’ legal guardian/next of kin. The research has been conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed and discussed in the framework of this study are included in this published article and its online

supplementary information. The corresponding author may provide specified analyses or fully de-identified parts of the dataset upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

this work was supported also by the Italian Ministry of Health with "Current Research funds”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Ranieri VM, Brodie D, Vincent JL: Extracorporeal organ support: from technological tool to clinical strategy supporting severe organ failure. JAMA 2017;318:1105–1106.

- Pistolesi V, Morabito S, Di Mario F, Regolisti G, Cantarelli C,Fiaccadori E. A Guide to under standing antimicrobial drug dosing in critically ill patients on renal replacement therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63:e00583-e619.

- Li L, Li X, Xia Y, Chu Y, Zhong H, Li J, et al. Recommendation of antimicrobial dosing optimization during continuous renal replacement therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:786. [CrossRef]

- Hoff BM, Maker JH, Dager WE, Heintz BH. Antibiotic dosing for critically ill adult patients receiving intermittent hemodialysis, prolonged intermittent renal replacement therapy, and continuous renal replacement therapy: an update. Ann Pharmacother. 2020;54:43–55. [CrossRef]

- Jamal J-A, Mueller BA, Choi GYS, Lipman J, Roberts JA. How can we ensure effective antibiotic dosing in critically ill patients receiving different types of renal replacement therapy? Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;82:92–103.

- Wong W-T, Choi G, Gomersall CD, Lipman J. To increase or decrease dosage of antimicrobials in septic patients during continuous renal replacement therapy: the eternal doubt. CurrOpinPharmacol. 2015;24:68–78. [CrossRef]

- Gatti M, Pea F et al.; Expert clinical pharmacological advice may make an antimicrobial TDM program for emerging candidates more clinically useful in tailoring therapy of critically ill patients. Critical Care (2022) 26:178. [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Aziz MH, Alffenaar J-WC, Bassetti M, Bracht H, Dimopoulos G, Marriott D, et al. Antimicrobial therapeutic drug monitoring in critically ill adult patients: a position paper. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:1127–53. [CrossRef]

- Poli, E. C., Rimmele, T. & Schneider, A. G. Hemoadsorption with CytoSorb((R)). Intensive Care Med. (2018). [CrossRef]

- Malard B, Lambert C, Kellum JA (2018) In vitro comparison of the adsorption of inflammatory mediators by blood purification devices. Intensive Care Med Exp 6:12.

- Bottari G, Lorenzetti G, Severini F, Cappoli A, Cecchetti C, Guzzo I. Role of Hemoperfusion With CytoSorb Associated With Continuous Kidney Replacement Therapy on Renal Outcome in Critically III Children With Septic Shock. Front Pediatr. 2021 Aug 24;9:718049. [CrossRef]

- Bottari G, Guzzo I, Marano M, Stoppa F, Ravà L, Di Nardo M, Cecchetti C. Hemoperfusion with Cytosorb in pediatric patients with septic shock: A retrospective observational study. Int J Artif Organs. 2020 Sep;43(9):587-593. [CrossRef]

- Liebchen U, Scharf C, Zoller M, Weinelt F, Kloft C; CytoMero collaboration team.No clinically relevant removal of meropenem by cytokine adsorber CytoSorb® in critically ill patients with sepsis or septic shock.Intensive Care Med. 2021 Nov;47(11):1332-1333. [CrossRef]

- Dimski T, Brandenburger T, MacKenzie C, Kindgen-Milles D. Elimination of glycopeptide antibiotics by cytokine hemoadsorption in patients with septic shock: A study of three cases.Int J Artif Organs. 2020 Dec;43(12):753-757. [CrossRef]

- Leteurtre S, Duhamel A, Salleron J, Grandbastien B, Lacroix J, Leclerc F; Groupe Francophone de Réanimation et d’Urgences Pédiatriques (GFRUP). PELOD-2: an update of the PEdiatric logistic organ dysfunction score. Crit Care Med. 2013 Jul;41(7):1761-73.

- Gaies MG, Jeffries HE, Niebler RA, Pasquali SK, Donohue JE, Yu S, Gall C, Rice TB, Thiagarajan RR. Vasoactive-inotropic score is associated with outcome after infant cardiac surgery: an analysis from the Pediatric Cardiac Critical Care Consortium and Virtual PICU System Registries. PediatrCrit Care Med. 2014 Jul;15(6):529-37.

- KDIGO KDIGO AKI Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Kidney IntSuppl2012; 2: 1–138.

- Zellos A, Debray D, Indolfi G. Proceedings of ESPGHAN monothematic conference 2020: “acute liver failure in children” : diagnosis and initial management. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Diagnostic Approach to Acute Liver Failure in Children: A Position Paper by the SIGENP Liver Disease Working Group. A. Di Giorgio, L. D’Antiga. Digestive and Liver Disease 53 (2021) 545–557. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A; International Consensus Conference on Pediatric Sepsis. International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. PediatrCrit Care Med. 2005 Jan;6(1):2-8.

- European Medicines Agency. Guidelines on Bioanalytical Method Validation. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-bioanalytical-methodvalidation_en.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2022).

- Cairoli S, Simeoli R, Tarchi M, Dionisi M, Vitale A, Perioli L, Dionisi-Vici C, Goffredo BM. A new HPLC-DAD method for contemporary quantification of 10 antibiotics for therapeutic drug monitoring of critically ill pediatric patients. Biomed Chromatogr. 2020 Oct;34(10):e4880. [CrossRef]

- M. Gatti, S. Tedeschi, F. Trapani, S. Ramirez, R. Mancini, M. Giannella, P. Viale, F. Pea, A Proof of Concept of the Usefulness of a TDM-Guided Strategy for Optimizing Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Target of Continuous Infusion Ampicillin-Based Regimens in a Case Series of Patients with Enterococcal Bloodstream Infections and/or Endocarditis, Antibiotics (Basel) 11(8) (2022). [CrossRef]

- Scheier J, Nelson PJ, Schneider A, Colombier S, Kindgen-Milles D, Deliargyris EN, Nolin TD.Mechanistic Considerations and Pharmacokinetic Implications on Concomitant Drug Administration During CytoSorb Therapy.Crit Care Explor. 2022 May 9;4(5):e0688. [CrossRef]

- Schneider AG, André P, Scheier J, Schmidt M, Ziervogel H, Buclin T, Kindgen-Milles D. Pharmacokinetics of anti-infective agents during CytoSorb hemoadsorption. Sci Rep. 2021 May 18;11(1):10493. [CrossRef]

- Perrottet N, Robatel C, Meylan P, Pascual M, Venetz JP, Aubert JD, Berger MM, Decosterd LA, Buclin T. Disposition of valganciclovir during continuous renal replacement therapy in two lung transplant recipients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008 Jun;61(6):1332-5. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn102. Epub 2008 Mar 15. PMID: 18344549. [CrossRef]

- Reiter K, Bordoni V, Dall’Olio G, et al: In vitro removal of therapeutic drugs with a novel adsorbent system. Blood Purif 2002; 20:380–388.

- König C, Röhr AC, Frey OR, Brinkmann A, Roberts JA, Wichmann D, Braune S, Kluge S, Nierhaus A. In vitro removal of anti-infective agents by a novel cytokine adsorbent system. Int J ArtifOrgans. 2019 Feb;42(2):57-64. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).