Introduction

Sub-Saharan African countries and South Asian countries like India, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka give heavy subsidies on chemical fertilizers to farmers. The main aim of these subsidies is to increase the crop yield to increase farmers’ income and food security [

1].

India is home to one-sixth of the global population and holds the key to the success of the United Nations 2030 agenda or sustainable development goals (SDGs). The 17 SDGs emphasize the interconnected environmental, social and economic aspects of sustainable development by putting sustainability at their centre [

2]. SDG 2 is to end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture [

3].

SDGs were formulated in 2015 by the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), but India has been trying to achieve National food security along with sustainable agriculture from year 2007. Indian government’s efforts were similar to the SDG 2 targets. From year 2007 to 2023, the Government of India launched various programmes in this direction. In 2007, the National Agriculture Development Programme (RKVY) was launched. National Project on Management of Soil Health & Fertility (2008-2009), National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture (2014-2015), and recently Paramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana was launched in 2023. Studying the performance of such programs is necessary for fact-based discussions in sessions of parliament similar to the farmer’s issues like pesticide management [

4] or access to quality seeds [

5] etc. Consequently, a better policy can be formulated to achieve the desired goals.

The United Nations predicts that we will need to produce 50% more food by 2050 to feed another 2.5 billion people [

6]. To achieve food security, improving agricultural production is necessary [

7]. Innovations like farming the sea [

8,

9], precision farming [

10], permaculture [

11], vigour maintaining seeds [

12,

13], and advancing genetic selection technologies [

14,

15] need to be implemented.

Whatever would be the farming method, fertilizers are one of the important factors affecting agriculture as well as environment [

16,

17]. The use of organic fertilizer has contributed significantly to environmental sustainability and increasing agricultural production. So, to lessen the negative environmental impact of chemical fertilizers, replacing chemical fertilizers with organic fertilizers is a good choice for farmers [

18].

Crops can take up only 30–50% of chemical fertilizers, and a great amount of the applied components is lost in the soil where it pollutes groundwater [

19]. In such situations, it becomes necessary to understand the patterns of chemical or synthetic fertilizer (NPK) consumption over a period of time. Till date, there are few studies available showing the pattern of chemical fertilizer consumption by Indian farmers. However, most of these studies are either showing intra-state variations in chemical fertilizer consumption patterns [

20,

21] or chemical fertilizer consumption patterns for specific states or agricultural zones [

22,

23,

24]. Some of the studies are carried out to study the determinants of fertilizer consumption [

25,

26]. But there is hardly any study available which can show the national level chemical fertilizer consumption pattern specifically after year 2007, when India has decided to achieve food security along with agricultural sustainability.

This study mainly focuses on the exact quantity of chemical fertilizer consumption at the national level on a year-on-year basis specifically after year 2007. Our main purpose is to comprehend if there is any impact of the government’s sustainable agriculture program on the behaviour of farmers while choosing between organic or chemical fertilizers. The consumption pattern of chemical fertilizer mainly after year 2007 is studied when the government announced various programs for sustainable agricultural development. This study of the trend in the consumption of chemical fertilizers from the year 2007 will help to understand the impact of the government programs on the choice of farmers, to understand factors responsible for the consumption of synthetic fertilizers by farmers, to promote organic fertilizers and to design future policies to achieve food security with agriculture sustainability.

Methods:

In the present study, secondary data was used for evaluating the trend in chemical fertilizer consumption in India for the period 2007-2022.

The data on the All-India consumption of fertilizer nutrients is collected from The Fertilizer Association of India

https://www.faidelhi.org/general/con-npk.pdf. The Fertilizer Association of India (FAI) is a non-profit and non-trading company representing mainly the fertilizer manufacturers, distributors, importers, equipment manufacturers, research institutes and suppliers of inputs. The Association was established in 1955 with the objective of bringing together all concerned with the production, marketing and use of fertilizers. This study carried out the analysis of fertilizer consumption in India from the year 2007-08 to 2021-22. For the convenience of the analysis, the total time of the study is divided into three sub groups of 5 years durations each.

The data collected was stored, tabulated and analysed. Total quantity of fertilizer (N+P2O5+K2O) used per year is considered for the analysis. Keeping in view the specific objectives of the study, the data collected were subjected to tabular analysis and year wise growth rate analysis. In tabular analysis, the difference in consumption for the current year and the previous year as well as the average consumption of chemical fertilizer per year was analysed and the growth rate was studied by following formula-

Average consumption of chemical fertilizers per year for the period of five years is calculated by the formula

All the values from FAI data are in ‘000 tonnes as used in the text.

Results

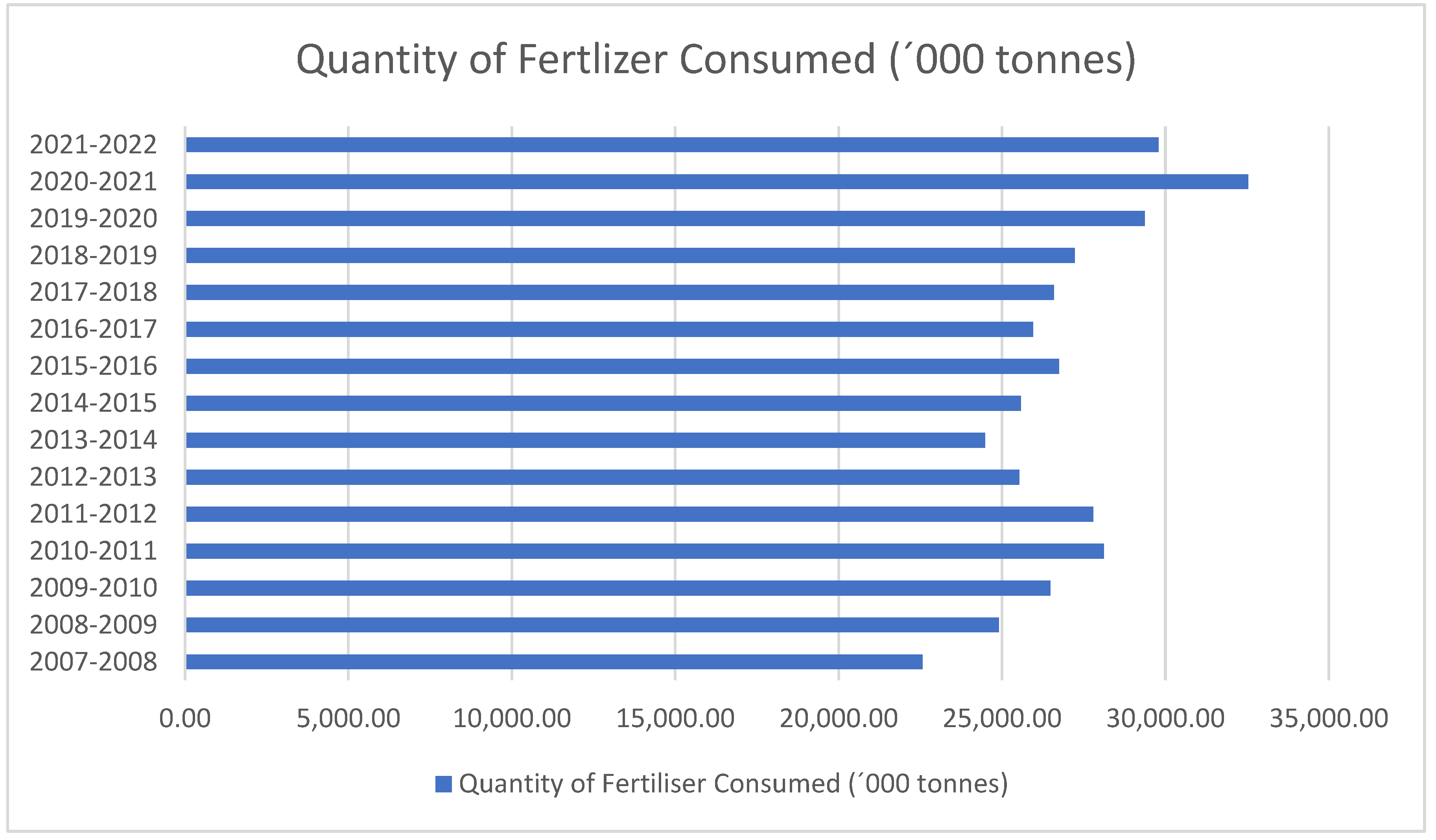

The fertilizer consumption results for the 5 years (2007-2012) of analysis show increasing trends (

Table 1). But the maximum consumption of chemical fertilizer in these five years was in year 2008-2009. This is the year when the National Project on Management of Soil Health & Fertility (2008-2009) was launched and just a year after the launch of the National Agriculture Development Programme (RKVY, 2007). In year 2011-2012, fertilizer consumption is reduced as compared to the previous year (2010-2011). In the five-year period, from 2007- 2012, the total quantity of fertilizer Consumed was 129878 tonnes. Whereas the average quantity of chemical fertilizer consumed per year was 25,975.6 tonnes (

Table 4).

When the analysis was done for the period of year 2012 to year 2017, the decreasing consumption trend was noticed (

Table 2). In these five years, comparatively lowest quantity of chemical fertilizer (24,482.4 tonnes) was used in the year 2013-2014. In this five-years period of year 2012-2017, the total chemical fertilizers consumed was 128302.4 tonnes whereas 25,660.48 tonnes were used per year.

The results for the year 2017-2022 are showing mixed trends (

Table 3). In the years 2017 to 2019, the chemical fertilizer consumption was more or less similar. But the values have shown the dramatic increase in the year 2019-2020 (29,370.4 tonnes) and year 2020-2021 (32,535.6 tonnes). Year 2020-2021 has seen the highest chemical fertilizer consumption in the total study period of fifteen years. Again, in the year 2021-2022, the chemical fertilizer consumption has reduced substantially. The total chemical fertilizer consumed in this period was 145523.9 tonnes whereas the average quantity of fertilizer consumed per year in this period was 29,104.78 tonnes.

Figure 1.

quantity of fertiliser consumed (‘000 tonnes) per year over the period of fifteen years.

Figure 1.

quantity of fertiliser consumed (‘000 tonnes) per year over the period of fifteen years.

Table 4.

Total quantity of Fertilizer Consumed in five years and average quantity of Fertilizer Consumed per year.

Table 4.

Total quantity of Fertilizer Consumed in five years and average quantity of Fertilizer Consumed per year.

| Sr. No |

Period |

Total quantity of Fertilizer Consumed (´000 tonnes) |

Average quantity of Fertilizer Consumed per year (´000 tonnes) |

| 1 |

2007-2012 |

129878.0 |

25,975.60 |

| 2 |

2012-2017 |

128302.4 |

25,660.48 |

| 3 |

2017-2022 |

145523.9 |

29,104.78 |

Discussion

In 2007, National Agriculture Development Programme (RKVY) was launched. The main objective of this program was to increase productivity of important crops through focused interventions and maximizing returns to farmers. After year or so in year 2008-2009, to improve soil health through green manuring, the National Project on Management of Soil Health & Fertility was launched. Both these programs are important from agriculture sustainability and environmental management point of view. The reason behind implementing these programs might be through the XIth – five year plan, Government of India was trying to achieve 4% increase in agricultural growth while focussing on environmental sustainability.

The study is mainly carried out for understanding whether the government agriculture programs affect the chemical fertilizer consumption of Indian farmers or not. The results of the study have shown steadily increasing trends in the chemical fertilizer consumption in India over the last fifteen years.

The analysis of year 2007-2012 shows, after launching these two crucial national programs there was increasing trend in the chemical fertilizer consumption. Many studies say, subsidy is one of the major reasons for the increasing trend of chemical fertilizer consumption [

27,

28]. If so, then it is important to consider in the study period, in certain years the chemical fertilizer consumption has reduced in India. In year 2011-2012, the chemical fertilizer consumption reduced by annual growth rate -1.18. The possible reason behind this might be, in year 2011–12 India saw extremely dry events or drought [

29].

The analysis of data for the year 2012-2017 shows slight reduction in the consumption of chemical fertilizers as compared to the period 2007-2012. The possible reason behind this trend might be the implementation of National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture (NMSA) in year 2014-2015. Soil Health Management (SHM) is one of the most important interventions under this Mission. SHM has an aim at promoting location as well as crop specific sustainable soil health management, creating and linking soil fertility maps with macro-micro nutrient management, judicious application of fertilizers and organic farming practices. These efforts of government might have helped in slight reduction of chemical fertilizer consumption during this period.

The results for the years 2017-2022, have shown considerable increase in consumption of chemical fertilizers as compared to the period 2007-2012 and 2012-2017. Though the analysis shows comparatively lower consumption in period 2007-2012 and 2012-2017, chemical fertilizer consumption in India in last fifteen years is increasing steadily with slight variations. There is hardly any inclination towards the use of organic fertilizers (manure).

Similar results were found in the comparative study carried out for India, Bangladesh and Nepal for chemical fertilizer used for Rice and Wheat crops [

30]. Here, farmers in focus groups indicated that their use of manure was decreasing over time in all the three countries. They reported that educated young household members are less interested in carrying manure to plots, and as a result, the use of chemical fertilizer is increasing over time. Economic and elements of social capital are primarily positively correlated with increased chemical fertilizer use. Their study also suggests wealth, gender, education, migration for employment, access to market, training, and off-farm income sources are some of the key factors influencing the application of chemical fertilizers.

Another study carried out in Iran to analyse the factors affecting the level of water resources pollution caused by the amount of chemical fertilizer consumed by farmers shows that variables such as main activity, farmers’ experience, farmers’ education, awareness of organic farming, income, price of fertilizers and irrigation methods have significant effect on the level of consumption of chemical fertilizers by farmers [

31].

Understanding the determinants for farmer’s choice of chemical fertilizer over the organic fertilizer can help to reduce the consumption of chemical fertilizers. This is relevant for informing

policy-making towards the negative environmental impacts and may help to achieve sustainable

agriculture development goals, such as the zero growth of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, and

recycling of animal and plant waste [

32].

A study carried out in Chinese farmers, different fertilizer investment behaviours has discussed interesting facts [

33]. Environmental friendliness appeared to be unattractive to farmers, who may usually be myopic in developing countries and may need community-level coordination in providing environmental goods that benefit themselves in the long run [

34,

35].

A study carried out in the Indo-Gangetic Plain (IGP) where the externalities of excessive use of chemical fertilizers for cereal production manifest in pollution highlights an interesting fact. Here, researchers studied the determining factors for the adoption of organic fertilizers in the region. Their study shows that only 32% of the farmers adopted organic fertilizers in the region whereas rest are dependent on the chemical fertilizers. Membership in farmer organizations, training, and education are the key variables that determine the adoption of organic fertilizers over chemical fertilizers. This study suggests the need for efficient extension efforts in organic fertilizers and suggests policy interventions that promote collective learning through farmer groups [

36].

The adoption rate of organic fertilizer is low compared to the increasing usage of chemical fertilizer because many farmers fear the loss of crop output. Uncertainty can lead risk-averse farmers to apply more fertilizers and generate more pollution than in the certainty case [

37]. Perceived high cost and long payback period are also the barriers of investment in organic fertilizer [

38]

A study was carried out with farmers of Denmark to understand their current use of organic fertilizer, their interest in using alternative types in the future, and their perception of most important barriers or advantages to using organic fertilizers. Almost three quarters of respondents (72%) used organic fertilizer, and half of the arable/horticultural farms (without livestock) used unprocessed manures, suggesting significant manure exchange from animal production farms to arable farms in Denmark. The most important barriers to the use of organic fertilizer identified among these respondents were an unpleasant odour for neighbours, uncertainty in nutrient content, and difficulty in planning and use. Improved soil structure was clearly chosen as the most important advantage or reason to use organic fertilizer, followed by low cost to buy or produce, and ease of availability. Consequently, Danish government policies aim to increase in manure processing [

39].

Our study clearly shows there is no effect of national sustainable agriculture policies on the consumption of chemical fertilizers by farmers. Across all the study period, farmers reported inclined to chemical fertilizers, related with a lack of awareness of the principles of appropriate fertilizer management that can limit environmental damage. Government needs to sensitize farmers by educational programs highlighting measures to improve nutrient-use-efficiency and reducing the negative impact of chemical fertilizer over-use.

Conclusions

This study clearly shows that chemical fertilizer consumption has increased steadily over the last fifteen years in India. There is no effect of national sustainable agriculture policies on the choice of consumption of chemical fertilizer of Indian farmers. Subsidy on the fertilizers is not the only reason behind the increasing use of chemical fertilizer over the organic fertilizer. Region specific determinants for choice of chemical fertilizers needs to study. To achieve goals of environmental management and agricultural sustainability, policies need to be framed to educate the farmers for long term gains of their choice of fertilizer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, analysis and investigation: - Jaimini Sarkar 2) Original draft preparation, review and editing- Chiradeep Sarkar.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests

References

- Aymeric Ricome, Jesus Barreiro-Hurle, Cheickh Sadibou Fall. 2024 Government fertilizer subsidies, input use, and income: The case of Senegal. Food policy, vol 124, 102623. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306919224000344.

- Schleicher, J., M. Schaafsma, and B. Vira. 2018. “Will the Sustainable Development Goals Address the Links Between Poverty and the Natural Environment?.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 34: 43–7.

- Goal 2: Zero Hunger. UNDP. Archived from the Original on 30 December 2020.

- Sarkar, J. 2011. “Science and Higher Education-Related Legislature Before Parliament.” Current Science 100, no. 9: 10.

- Sarkar, J. 2012. “Parliament sessions—Planning versus performance”. Current Science 102, no.9: 10.

- Food and Agriculture Organization. 2017b. “FAO and the SDGs. Indicators: Measuring up to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”. http://www.fao.org/3/a-i6919e.pdf. Rome.

- Pawlak, K. , and M. Kołodziejczak. 2020. “The Role of Agriculture in Ensuring Food Security in Developing Countries: Considerations in the Context of the Problem of Sustainable Food Production.” Sustainability 12, no. 13: 5488. [CrossRef]

- Schubel, Jerry R., and Kimberly Thompson. 2019. “Farming the Sea: The Only Way to Meet Humanity’s Future Food Needs.” GeoHealth 3, no. 9: 238–44. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, J. 2021. “Farming the Sea for the Future.” Science Reporter 3: 28–31.

- Erickson, B. , and S. W. Fausti. 2021. “The Role of Precision Agriculture in Food Security.” Agronomy Journal 113, no. 6: 4455–62. [CrossRef]

- Kurniawati, I. Z. Dahlan, and B. Faisal. “Permaculture Landscape as an Adaptive Strategy Towards Food Security at Community-Scale.” IOP Conference Series: Earth & Environmental Science 1092: 012015.

- Finch-Savage, W. E. , and G. W. Bassel. 2016. “Seed Vigour and Crop Establishment: Extending Performance Beyond Adaptation.” Journal of Experimental Botany 67, no. 3, Febr.: 567–91. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, J. 2011. “Vigour Maintaining Seeds for Farmers.” Current Science 101, no. 1: 12–3.

- Qaim, Matin. 2020. “Role of New Plant Breeding Technologies for Food Security and Sustainable Agricultural Development.” Applied Economic Perspectives & Policy 42, no. 2: 129–50. [CrossRef]

- Shabnam, A. A., D. Jaimini, R. Phulara, C. Sarkar, and S. E. Pawar. 2011. “Evaluation of Gamma Rays-Induced Changes in Oil Yield and Oleic Acid Content of Niger, Guizotia abyssinica (L.f.) Cass..” Current Science, 101.

- Li, Dong-Po, and Zhi-Jie Wu. 2008, May. “Impact of Chemical Fertilizers Application on Soil Ecological Environment.” Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao 19, no. 5: 1158–65. Chinese. PubMed: 18655608.

- Savci, S. 2012. “Investigation of Effect of Chemical Fertilizers on Environment.” APCBEE Procedia 1: 287–92. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Y. Zhu, S. Zhang, and Y. Wang. 2018. “What Could Promote Farmers to Replace Chemical Fertilizers with Organic Fertilizers?.” Journal of Cleaner Production 199: 882–90. [CrossRef]

- Link, J., S. Graeff, W. D. Batchelor, and W. Claupein. 2006. “Evaluating the Economic and Environmental Impact of Environmental Compensation Payment Policy Under Uniform and Variable-Rate Nitrogen Management.” Agricultural Systems 91, no. 1–2: 135–53. [CrossRef]

- Bora, K. 2022. “Spatial Patterns of Fertilizer Use and Imbalances: Evidence from Rice Cultivation in India.” Environmental Challenges 7: 100452. [CrossRef]

- Chand, R. , and S. Pavithra. 2015. “Fertiliser Use and Imbalance in India: Analysis of States.” Economic & Political Weekly 50, no. 44: 98–104.

- Usama, M. , and A. K. Monowar. 2018. “Fertilizer Consumption in India and Need for Its Balanced Use: A Review.” Indian Journal of Environmental Protection 38, no. 7: 564–77.

- Singh Bagal, Y. S., L. K. Sharma, G. P. Kaur, A. Singh, and P. Gupta. 2018. “Trends and Patterns in Fertilizer Consumption: A Case Study.” International Journal of Current Microbiology & Applied Sciences 7, no. 4: 480–7. [CrossRef]

- Suryavanshi, S. 2015. “Growth of Chemical Fertilizer Consumption in India: Some Issues.” Research Front: 202–7.

- Jadhav, V. , and K. B. Ramappa. 2021. “Growth and Determinants of Fertilizer Consumption in India: Application of Demand and Supply Side Models.” Economic Affairs 66, no. 3: 419–25. [CrossRef]

- Waghmode, S. S., P. N. Shelake, and U. A. Vidhate. 2020. “Growth and Determinants of Fertilizer Use in India- an Economic Analysis.” International Journal of Current Microbiology & Applied Sciences 11: 1730–7.

- Chand, R. , and L. M. Pandey. 2008. “Fertilizer Growth, Imbalances and Subsidies – Trends and Implication” [Discussion] [Paper]. New Delhi: National Centre for Agricultural Economics and Policy Research.

- Praveen, K. V. , and A. Singh. “The Landscape of World Research on Fertilizers: A Bibliometric Profile.” Current Science 124, no. 10: 25.

- Udmale, P. D., Y. Ichikawa, S. Manandhar, H. Ishidaira, A. S. Kiem, N. Shaowei, and S. N. Panda. 2015. “How Did the 2012 Drought Affect Rural Livelihoods in Vulnerable Areas? Empirical Evidence from India.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 13, no. Sept.: 454–69. [CrossRef]

- Aryal, Jeetendra Prakash, Tek Bahadur Sapkota, Timothy J. Krupnik, Dil Bahadur Rahut, Mangi Lal Jat, and Clare M. Stirling. 2021. “Factors Affecting Farmers’ Use of Organic and Inorganic Fertilizers in South Asia.” Environmental Science & Pollution Research International 28, no. 37: 51480–96. [CrossRef]

- Hosein Mohammadi, A. 2017. Factors Affecting Farmer’s Chemical Fertilizers Consumption and Water Pollution in Northeastern Iran. Solmaz Nojavan. “Moarefi Mohammadi.” Journal of Agricultural Science 9, no. 2: 234.

- “Ministry-of-Agriculture.” National Agricultural Sustainable Development Plan of China (2015–2030). 2015. Beijing, China: Ministry-Of-Agriculture.

- Chen, X., D. Zeng, Y. Xu, and X. Fan. 2018. “Perceptions, Risk Attitude and Organic Fertilizer Investment: Evidence from Rice and Banana Farmers in Guangxi, China.” Sustainability 10, no. 10: 3715. [CrossRef]

- Dong, G., X. Mao, J. Zhou, and A. Zeng. 2013. “Carbon Footprint Accounting and Dynamics and the Driving Forces of Agricultural Production in Zhejiang Province, China.” Ecological Economics 91: 38–47. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., Z. Huang, X. Jia, R. Hu, and C. Xiang. 2015. “Long-Term Reduction of Nitrogen Fertilizer Use Through Knowledge Training in Rice Production in China.” Agricultural Systems 135: 105–11. [CrossRef]

- Koovalamkadu Velayudhan, P. , Singh, A., Jha, G. K., & Kumar, P. [2021]. Immanuelraj Thanaraj, K; Korekallu Srinivasa, A. What Drives the Use of Organic Fertilizers? Evidence from Rice Farmers in Indo-Gangetic Plains, India. Sustainability, 13, 9546.

- Isik, M. , and M. Khanna. 2003. “Stochastic Technology, Risk Preferences, and Adoption of Site-Specific Technologies.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 85, no. 2: 305–17. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y., G. L. Velthof, S. D. C. Case, M. Oelofse, C. Grignani, P. Balsari, L. Zavattaro, F. Gioelli, M. P. Bernal, D. Fangueiro, H. Trindade, L. S. Jensen, and O. Oenema. 2018. “Stakeholder Perceptions of Manure Treatment Technologies in Denmark, Italy, The Netherlands and Spain.” Journal of Cleaner Production 172: 1620–30. [CrossRef]

- Case, S. D. C., M. Oelofse, Y. Hou, O. Oenema, and L. S. Jensen. 2017. “Farmer Perceptions and Use of Organic Waste Products as Fertilizers—A Survey Study of Potential Benefits and Barriers.” Agricultural Systems 151: 84–95. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).