Submitted:

14 August 2024

Posted:

20 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

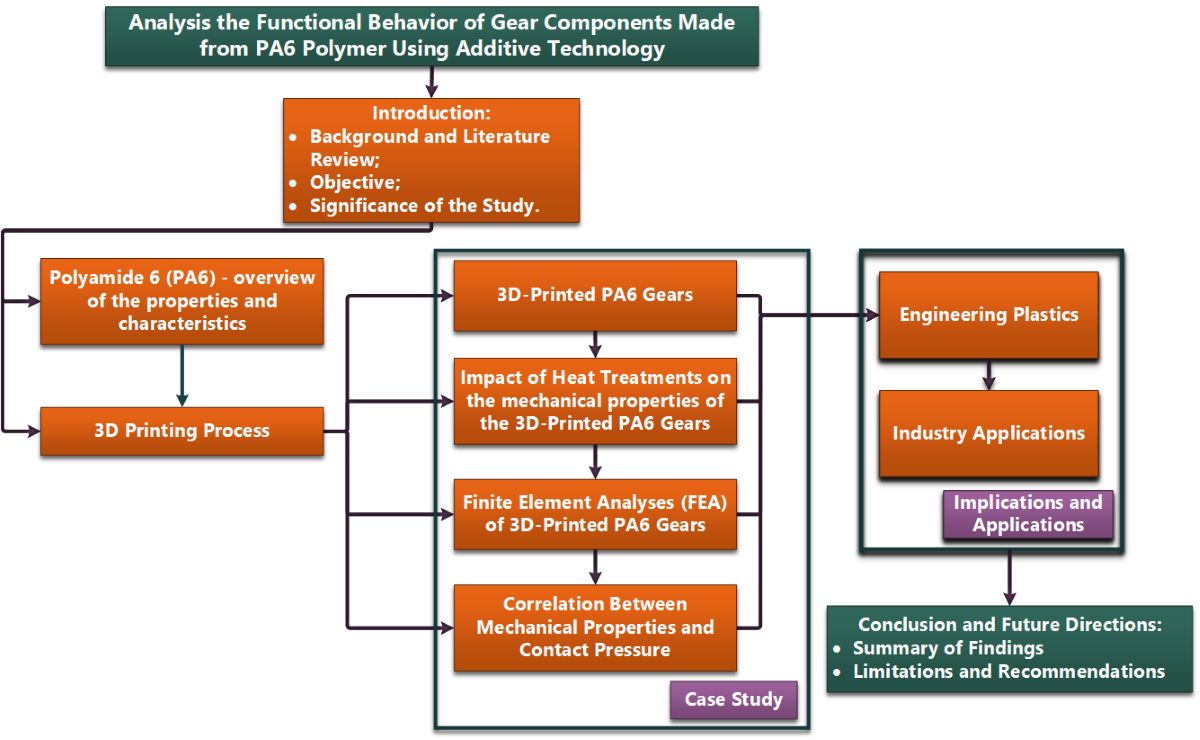

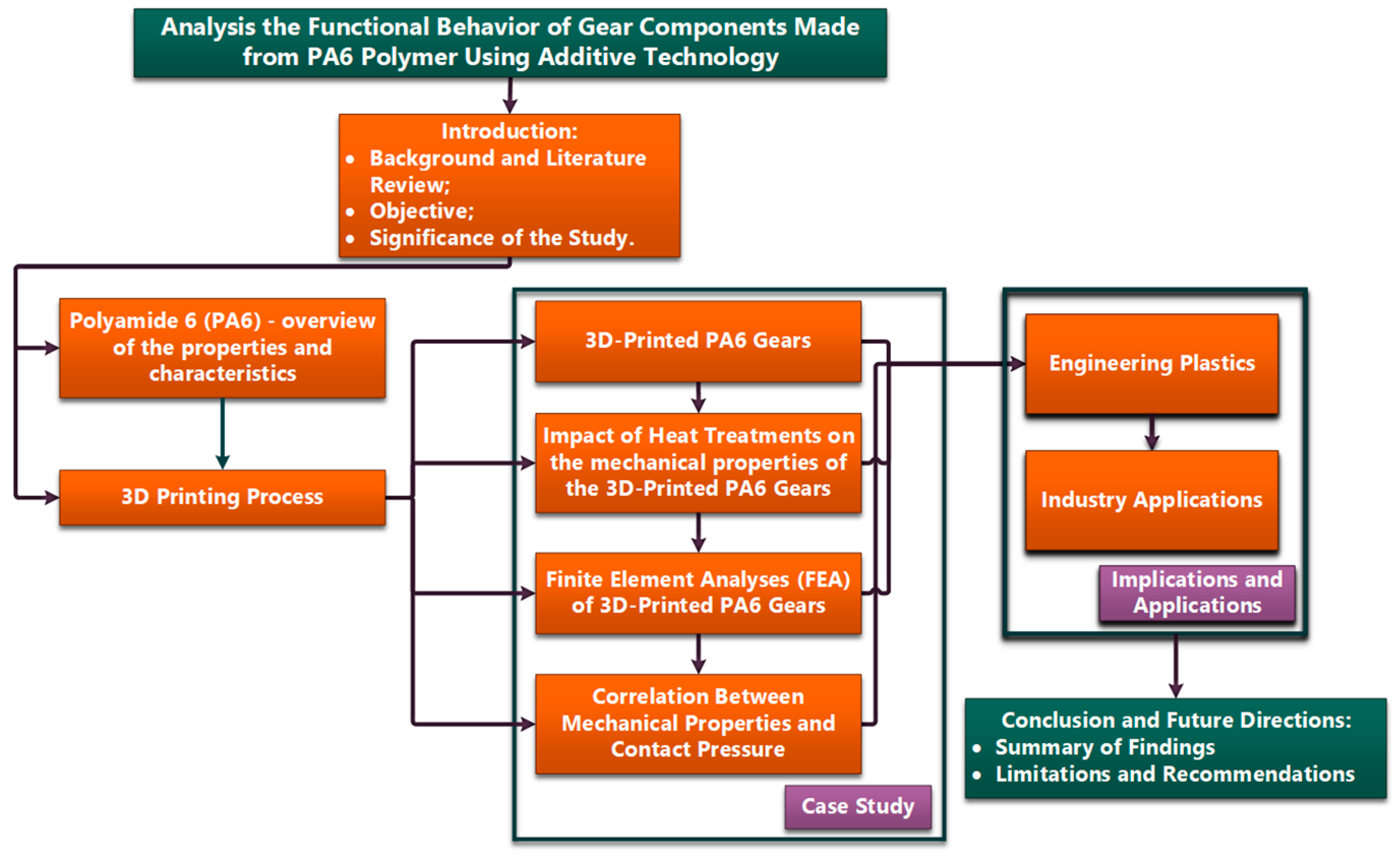

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Literature Review

1.2. Objective

1.3. Significance of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Polyamide 6 (PA6)

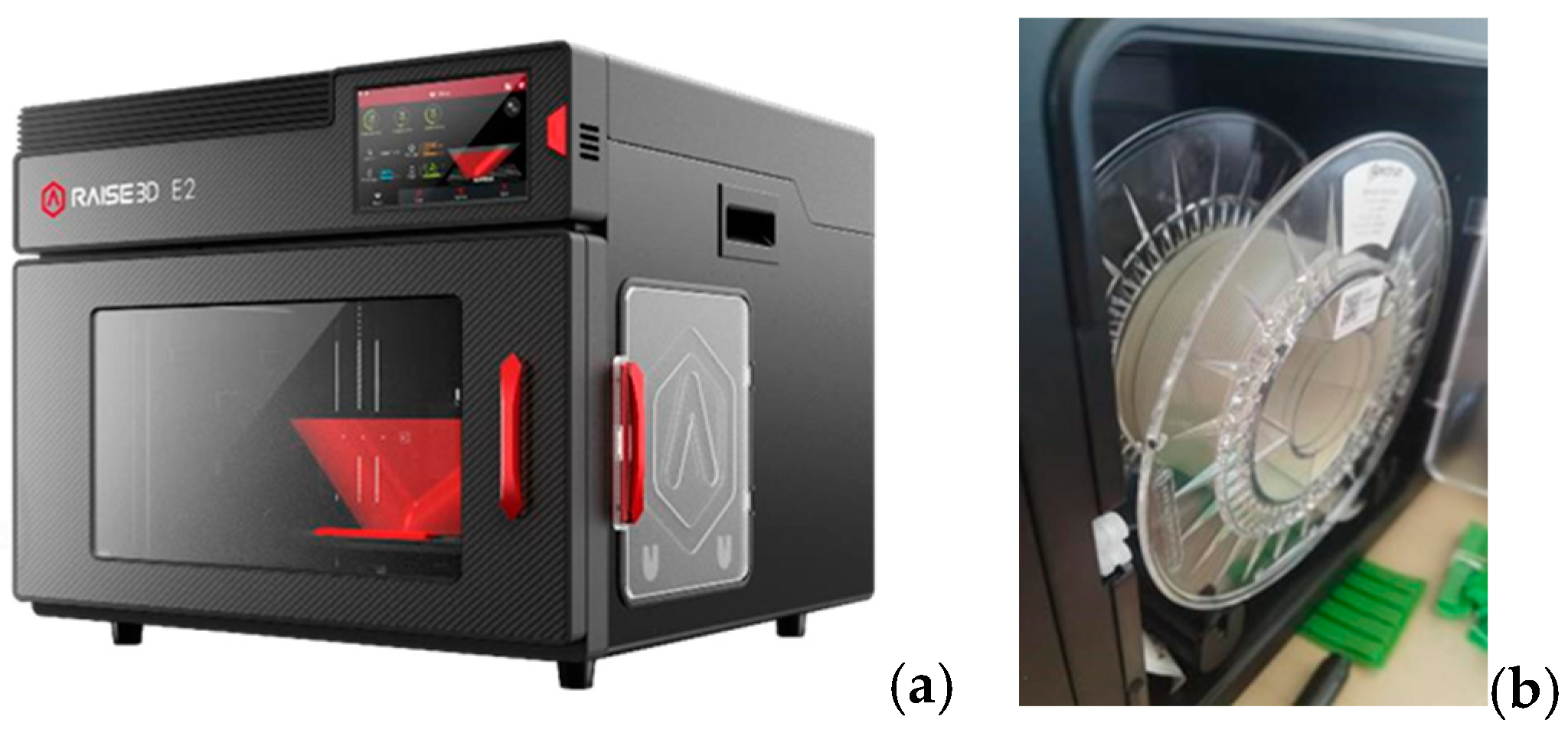

2.2. 3D Printing Process

2.3. Test Protocols

- the materials selected must have physicochemical, mechanical and technological properties that meet the requirements of the application;

- the technical solutions for the intended use, in terms of their economic viability, in terms of development, semi-manufacturing and manufacturing costs.

3. Results and Discussion

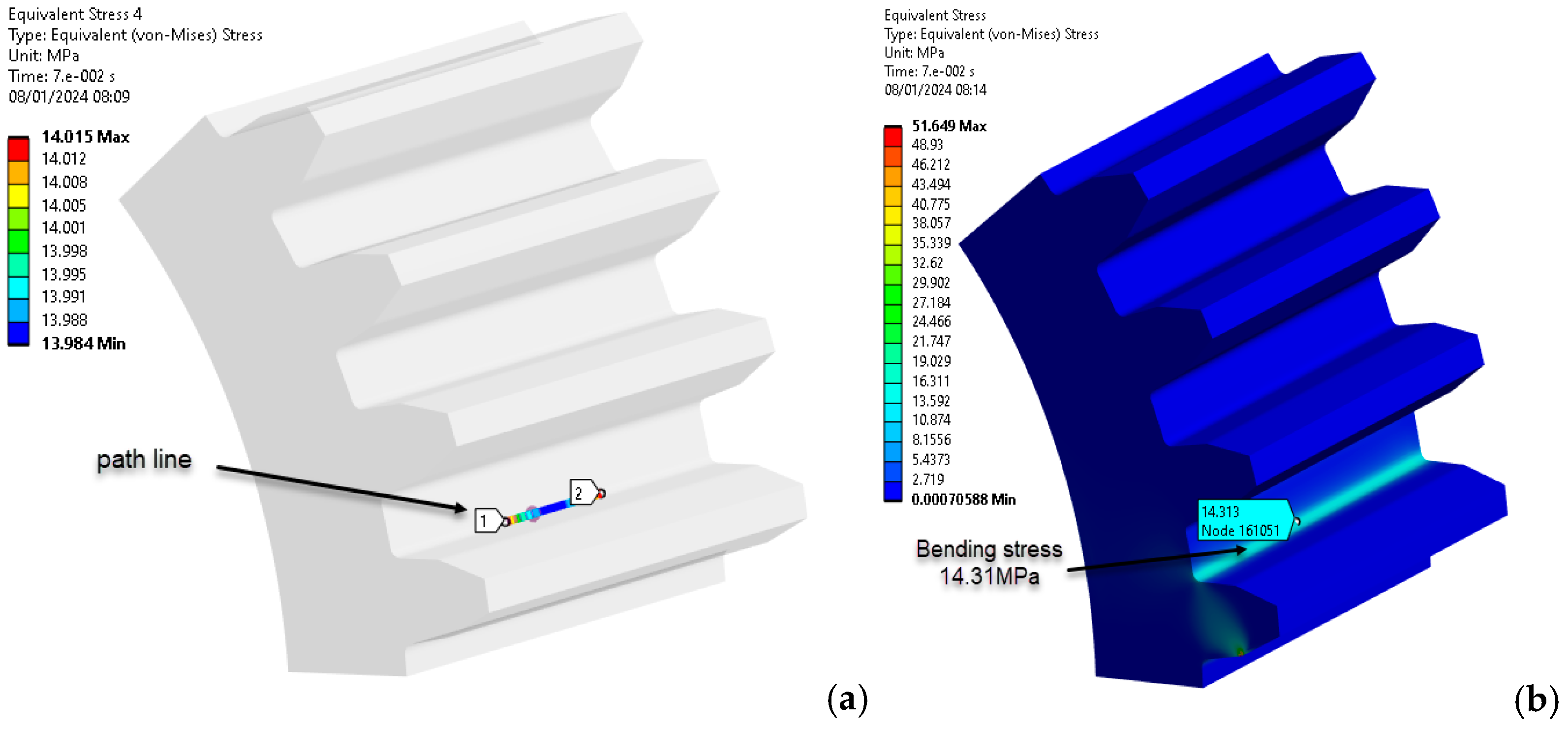

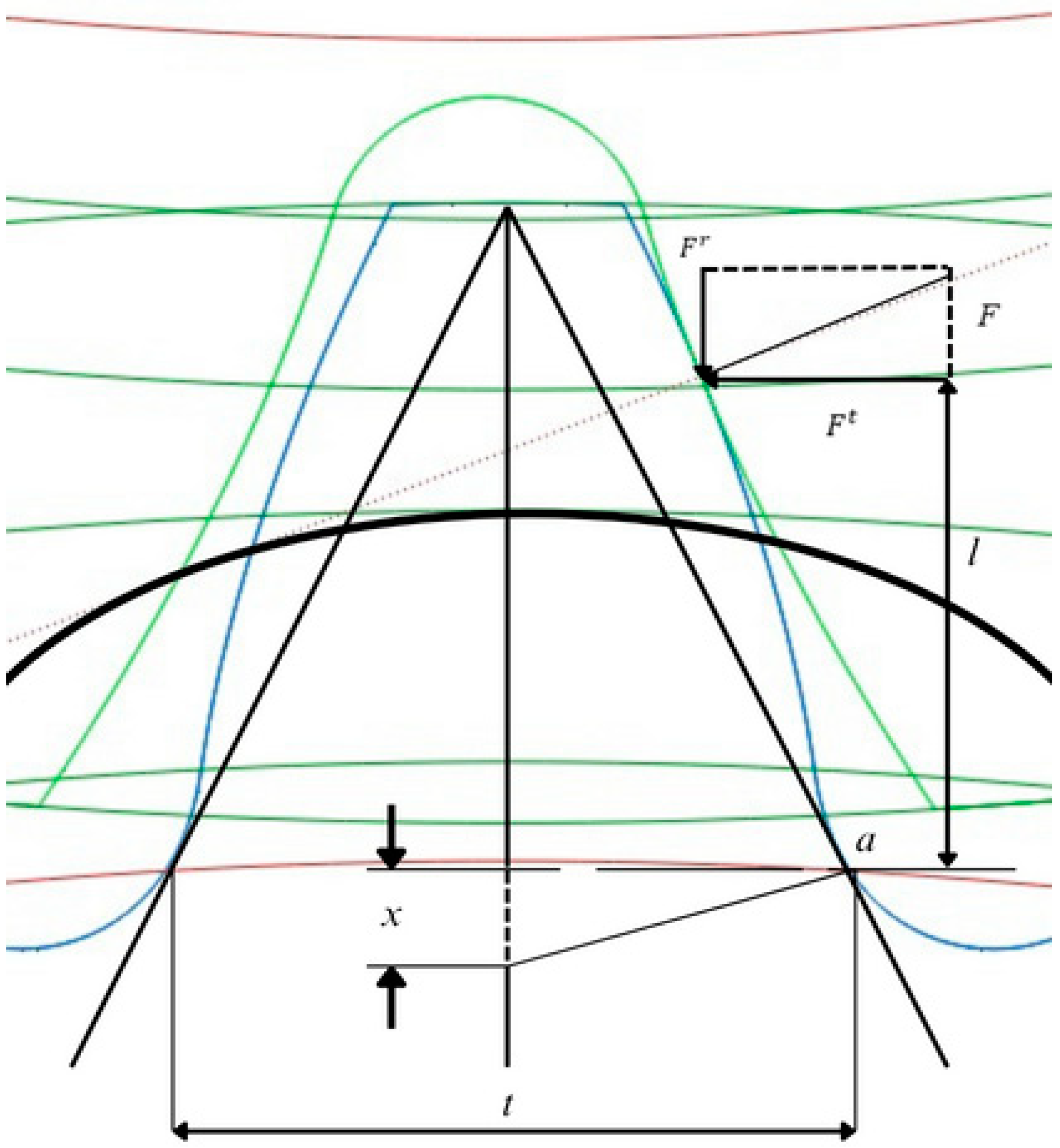

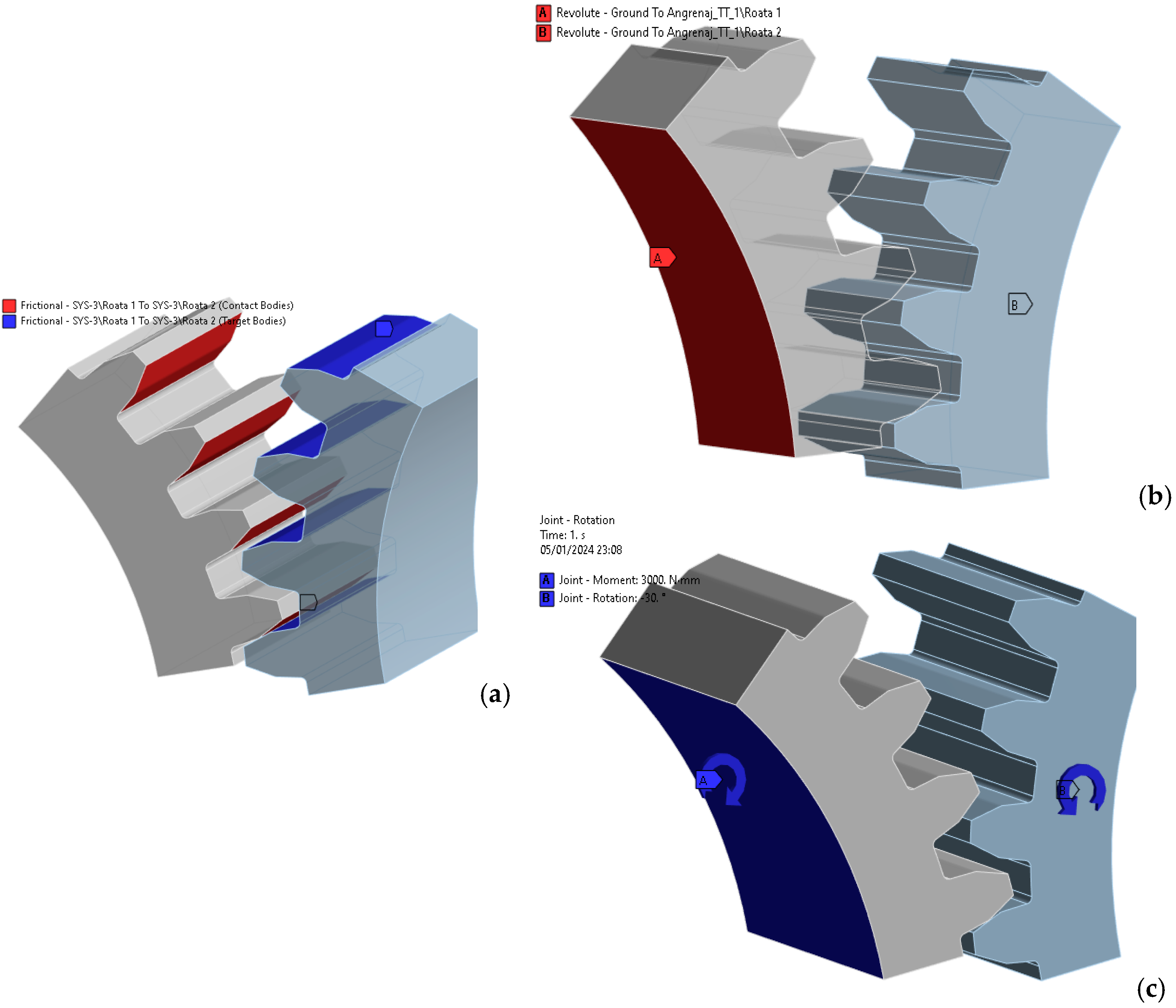

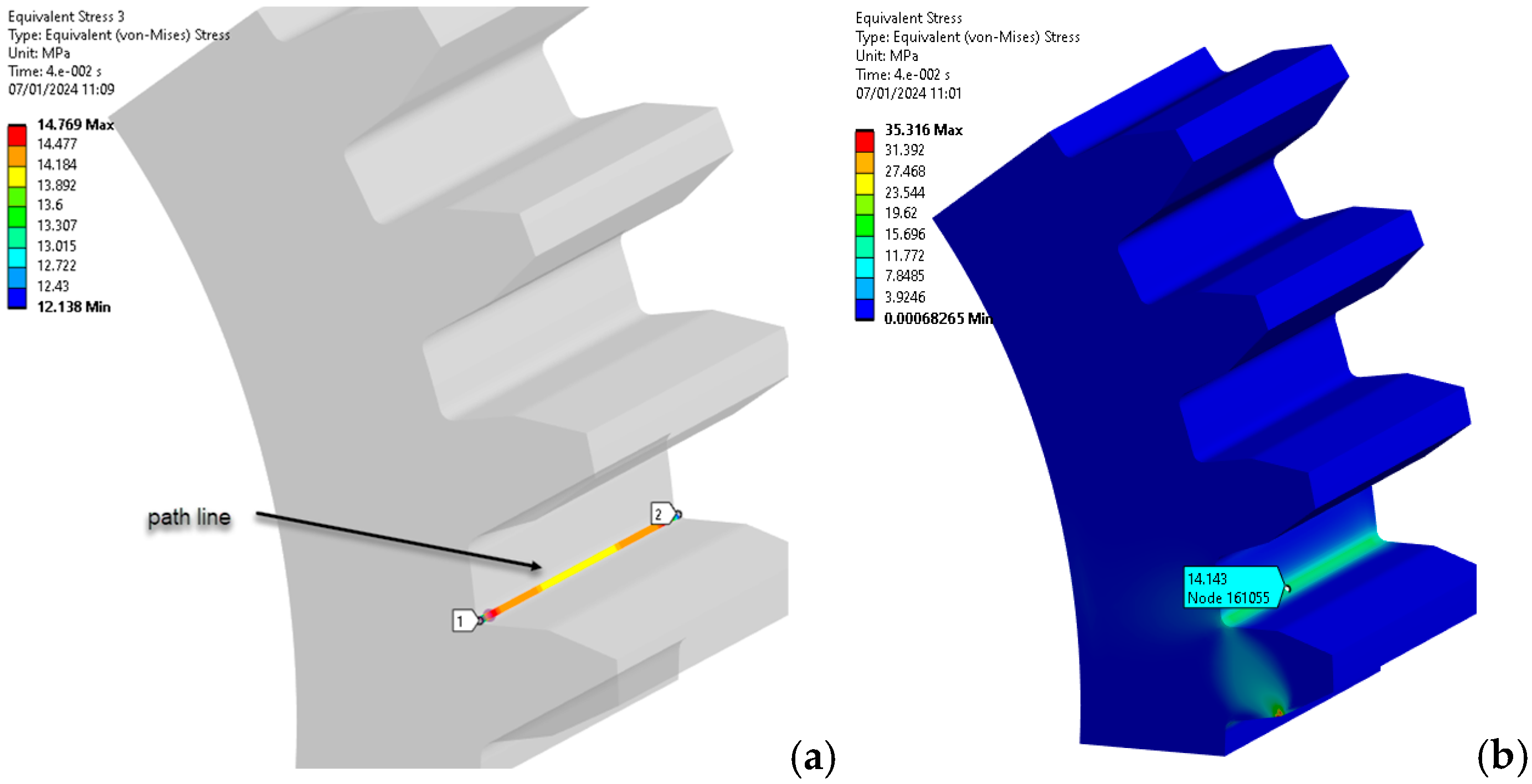

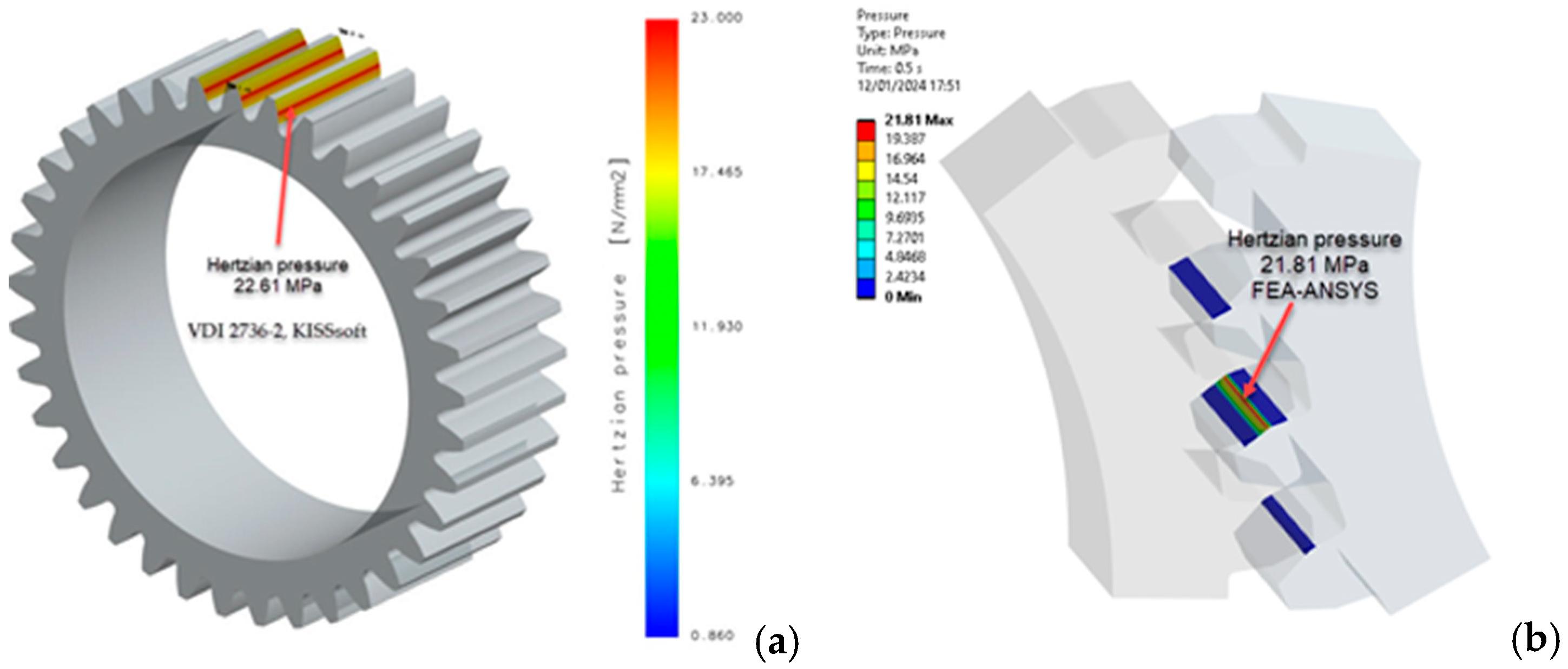

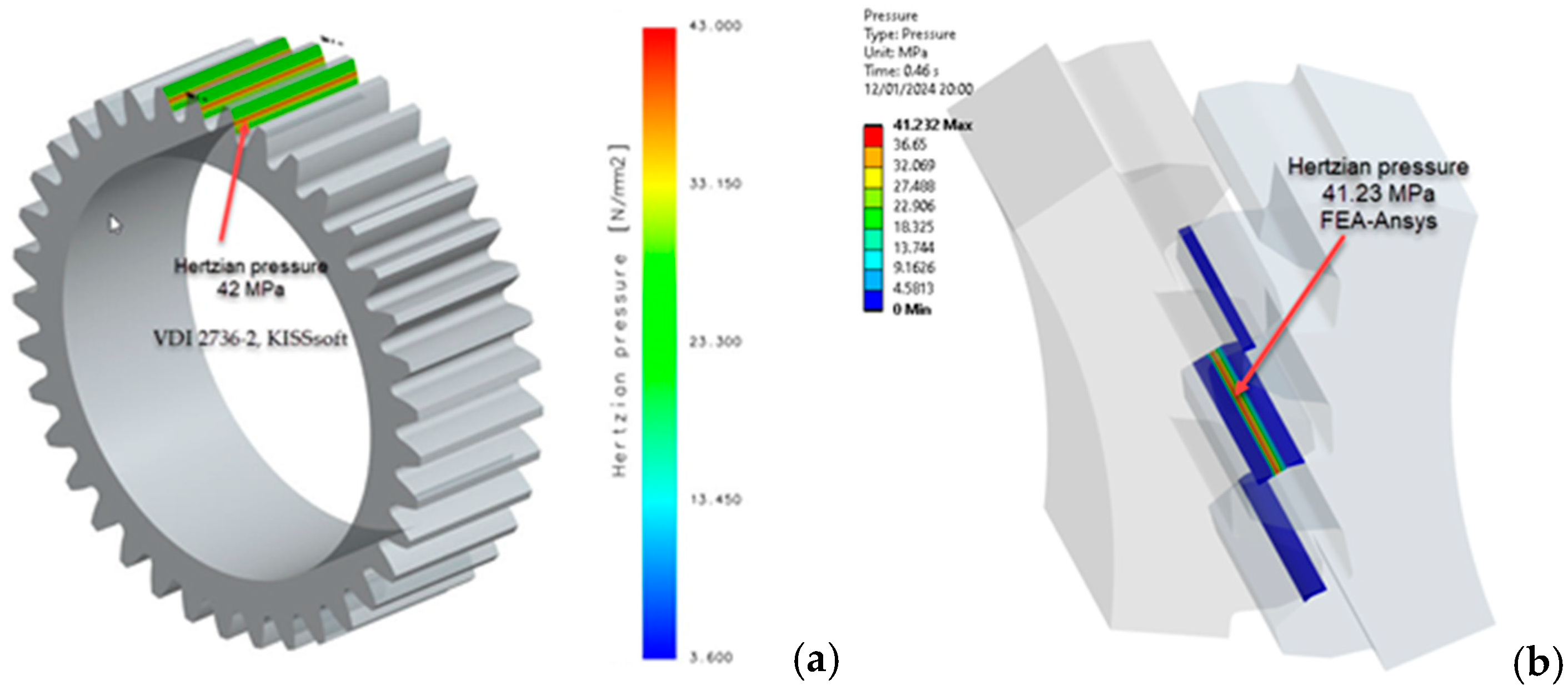

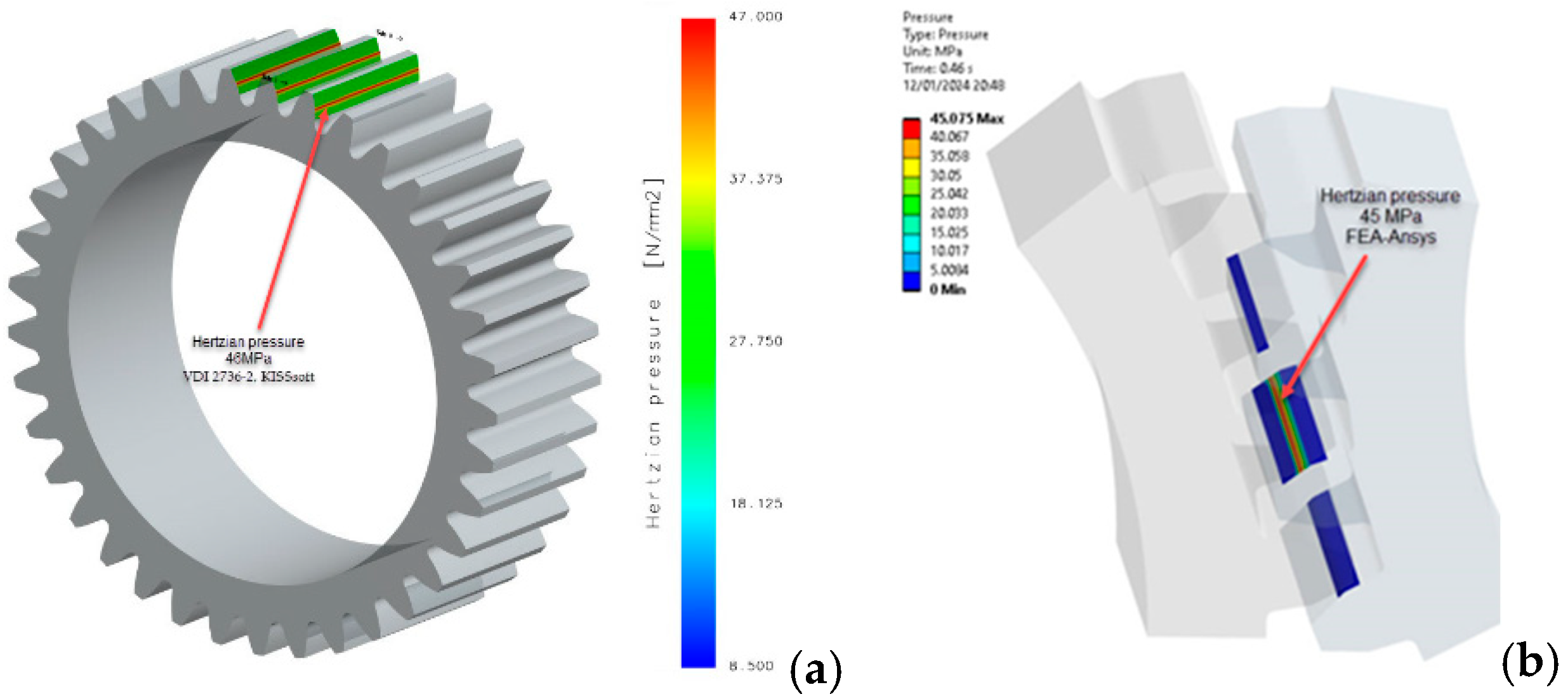

3.1. Finite Element Analyses of 3D-Printed Gears

3.2. Sensitivity Analyses

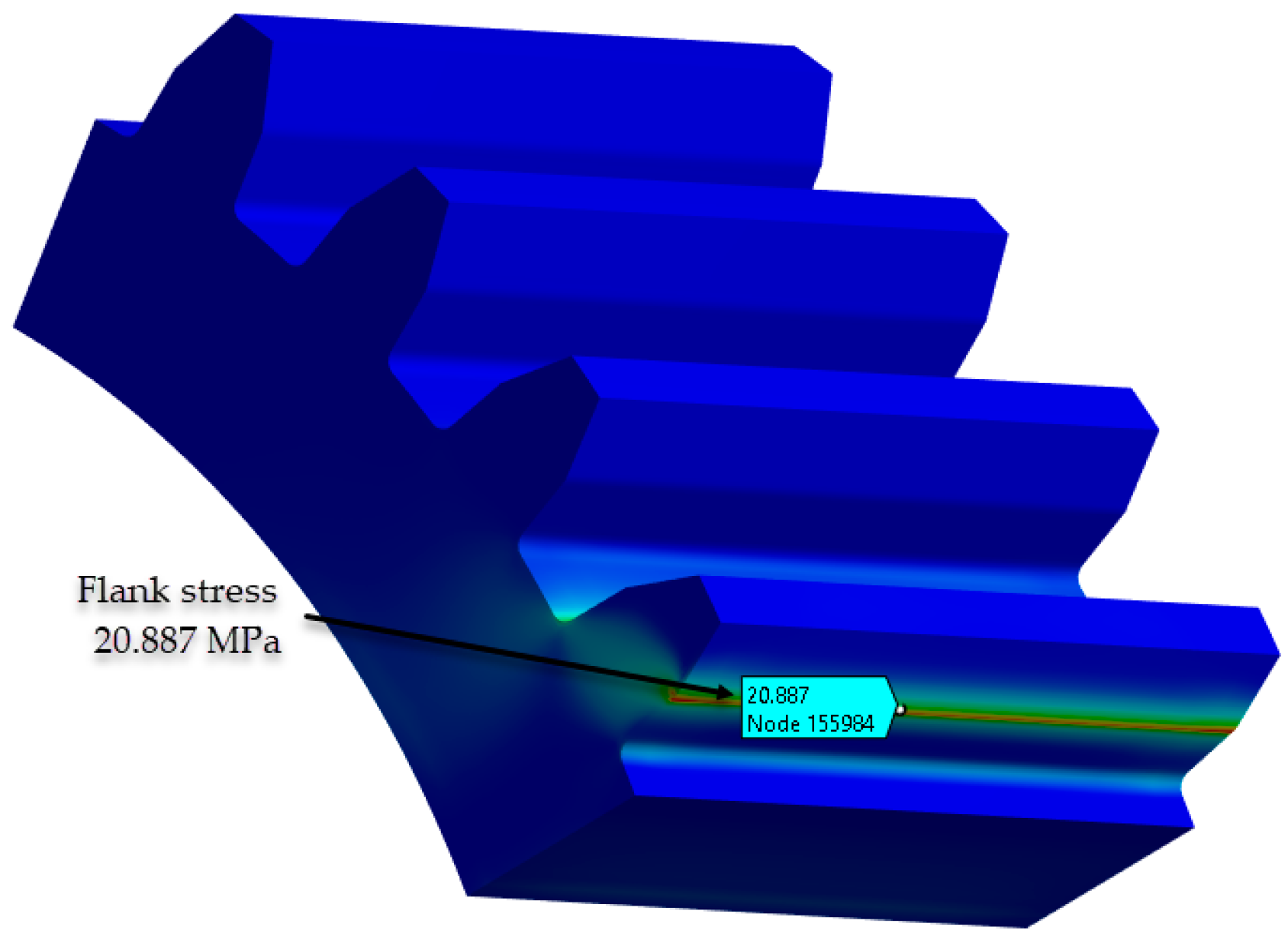

3.3. Effect of Heat Treatments on Bending Stress and Flank Contact Pressure

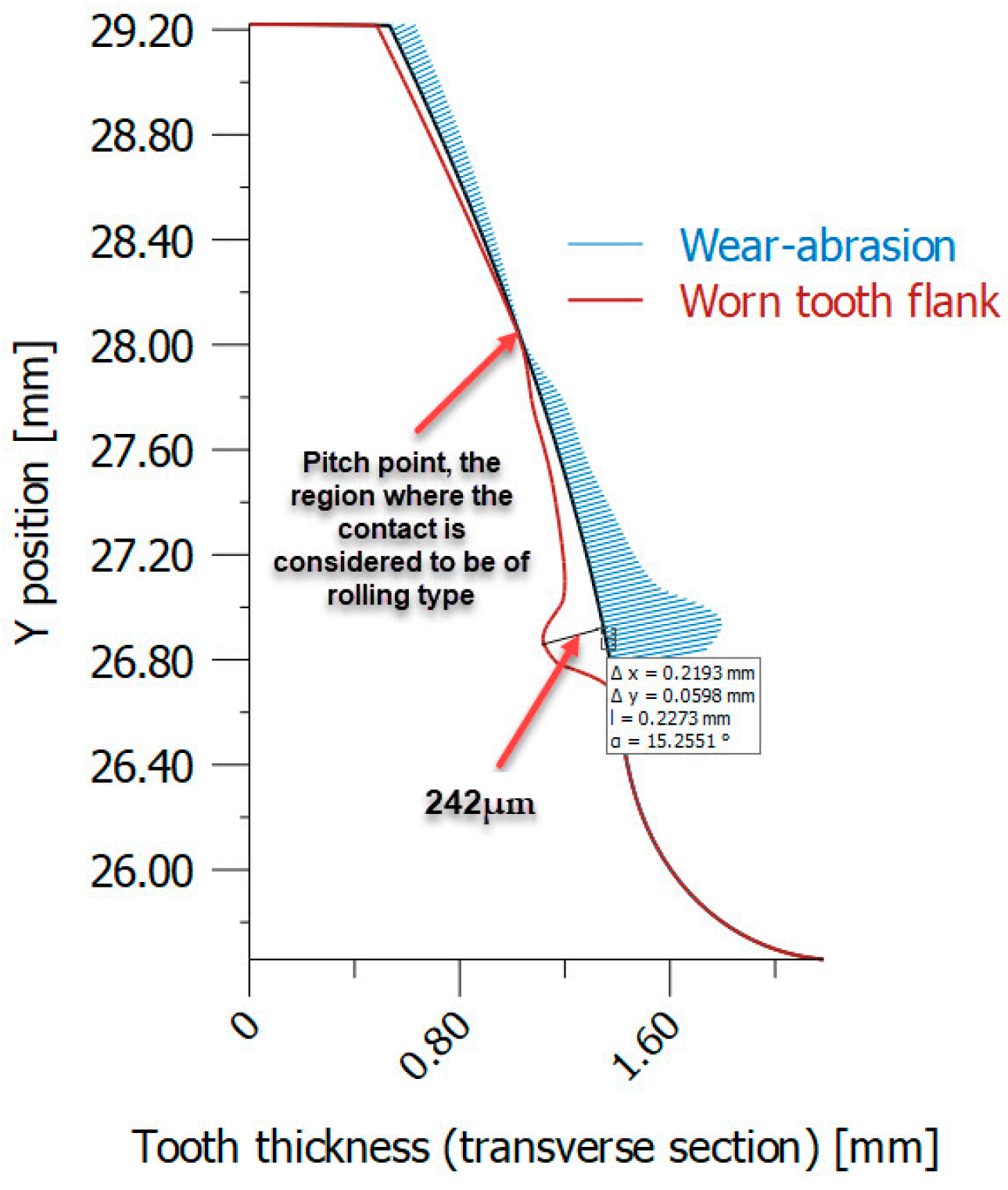

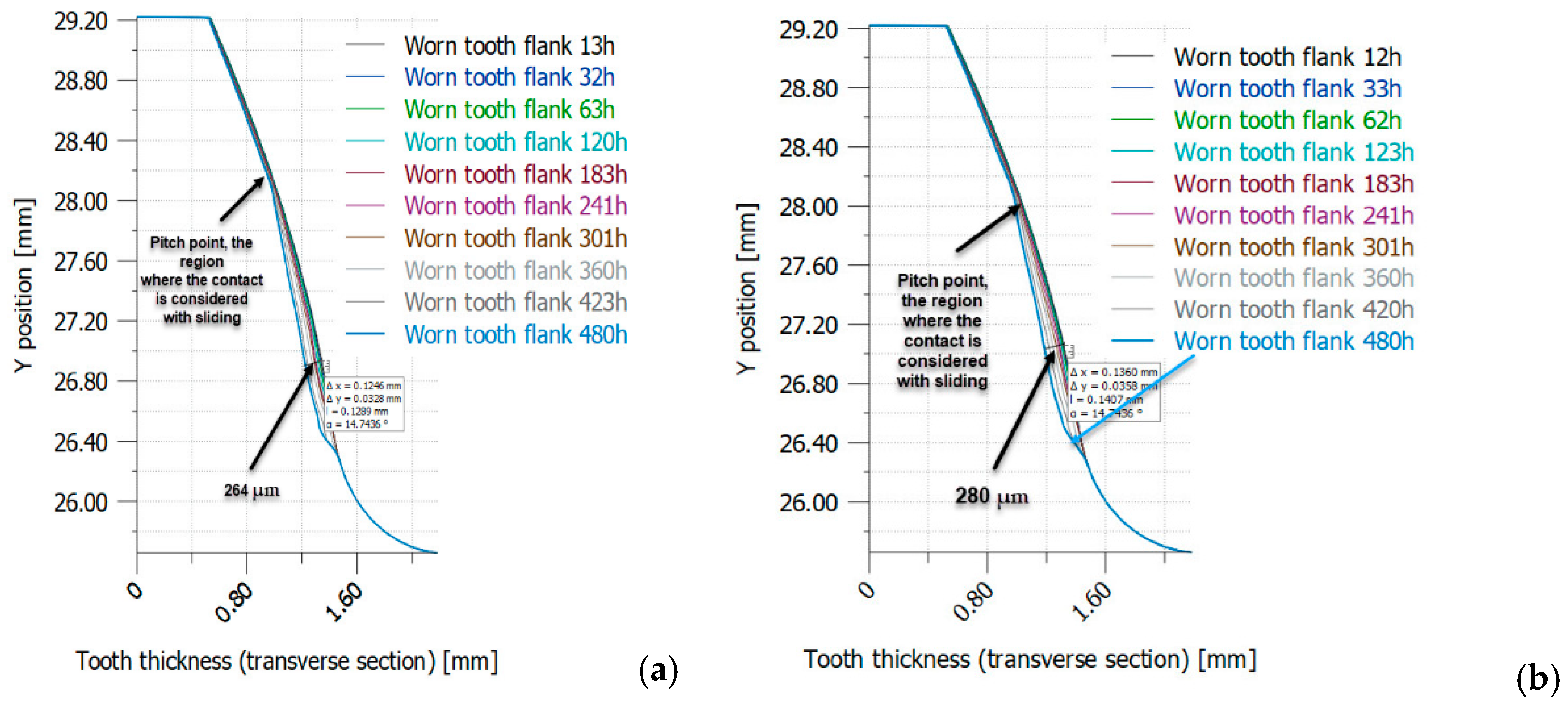

3.4. Effect of Heat Treatments on Wear and Service Life

4. Discussions

4.1. Discussions about Case Study

4.2. Correlation between Mechanical Properties and Contact Pressure

- A direct correlation between the increase in modulus of elasticity (E) due to heat treatment and high contact pressures is established in the text.

- There is theoretical support for this correlation in Equation 1 and empirical support in the results shown in Table 7.

- Root bending stress was found to have a relatively small effect on overall gear mechanical behaviour. This highlights the importance of the contact pressure on the flanks.

- The fatigue properties of the gear, as affected by heat treatment, are important for gear life and wear.

- Despite varying Young's modulus, gears subjected to different heat treatments show a constant life, highlighting the influence of factors such as wear and related mechanisms which are influenced by contact pressure and load cycles.

- It also highlights the importance of achieving the minimum levels of pulse and rolling contact resistance (Table 10) through heat treatment to ensure performance comparable to untreated PA6.

- Comparison of simulated and actual contact pressure values provides validation and ensures reliability of wear analysis.

5. Implications and Applications

5.1. Engineering Plastics

5.2. Industry Applications

6. Conclusion and Future Directions

6.1. Summary of Findings

6.2. Limitations and Recommendations

6.3. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Özsoy, K.; Aksoy, B.; Bayrakçı, H. C. Optimization of Thermal Modeling Using Machine Learning Techniques in Fused Deposition Modeling 3-D Printing. ASTM International. J. Test. Eval., January 2022, 50(1): 613–628. [CrossRef]

- Özsoy, K.; Erçetin, A.; Çevik, Z. A. Comparison of Mechanical Properties of PLA and ABS Based Structures Produced by Fused Deposition Modelling Additive Manufacturing. Avrupa Bilim Ve Teknoloji Dergisi, (27), 802-809. January 2022. [CrossRef]

- Karaveer, V.; Mogrekar, A.; Preman. R. Modeling and Finite Element Analysis of Spur Gear. International Journal of Current Engineering and Technology, ISSN 2277 - 4106, Volume 3, No.5 (December 2013), 29 December 2023 accessed.

- Rahul, M.; Kamble, D.P. Experimental investigation and FEA of wear in gear at torque loading conditions. IJARIIE-ISSN (O)-2395-4396, Volume-3, Issue-4, 2017, 29 December 2023 accessed.

- Rajeshkumar, S.; Manoharan, R. Design and analysis of composite spur gears using finite element method. IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 263 (2017) 062048 . [CrossRef]

- Bergant, Z.; Šturm, R.; Zorko, D.; Borut Cerne, B. Fatigue and Wear Performance of Autoclave-Processed and Vacuum-Infused Carbon Fibre Reinforced Polymer Gears. Polymers 2023, 15, 1767. [CrossRef]

- Catera, P.G.; Mundo, D.; Treviso, A.; et al. On the Design and Simulation of Hybrid Metal-Composite Gears. Appl Compos Mater 26, 817–833 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Muratovic, E.; Muminovic, A.; Delic, M.; Pervan, N.; Muminovic, A.J.; Šaric, I. Potential and Design Parameters of Polyvinylidene Fluoride in Gear Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 4275. [CrossRef]

- *** VDI 2736 Part 1; Thermoplastic Gear Wheels—Materials, Material Selection, Production Methods, Production Tolerances, Form Design. Verein Deutscher Ingenieure: Harzgerode, Germany, 2016, 30 December 2023 accessed.

- *** VDI 2736 Part 2; Thermoplastic Gear Wheels—Cylindrical Gears—Calculation of the Load—Carrying Capacity. Verein Deutscher Ingenieure: Harzgerode, Germany, 2016, 30 December 2023 accessed.

- *** VDI 2736 Part 3; Thermoplastic Gear Wheels—Crossed Helical Gears—Mating Cylindrical Worm with Helical Gear—Calculation of the Load Carrying Capacity. Deutscher Ingenieure: Harzgerode, Germany, 2016, 30 December 2023 accessed.

- *** VDI 2736 Part 4; Thermoplastic Gear Wheels—Determination of Strength Parameters on Gears. Deutscher Ingenieure: Harzgerode, Germany, 2016, 30 December 2023 accessed.

- Zhong, B.; Song, H.; Liu, H.; Wei, P.; Lu, Z. Loading capacity of POM gear under oil lubrication. J. Adv. Mech. Des. Syst. Manuf. 2022, 16, 31–36. [CrossRef]

- Trobentar, B.; Hriberšek, M.; Kulovec, S.; Glodež, S.; Belšak A. Noise Evaluation of S-Polymer Gears. Polymers 2022, 14, 438. [CrossRef]

- Zorko, D. Effect of Process Parameters on the Crystallinity and Geometric Quality of Injection Molded Polymer Gears and the Resulting Stress State during Gear Operation. Polymers 2023, 15, 4118. [CrossRef]

- Tunalioglu, M.S.; Agca, B.V. Wear and Service Life of 3-D Printed Polymeric Gears. Polymers 2022, 14, 2064. [CrossRef]

- *** Direct plastics, Available online: https://www.directplastics.co.uk/pdf/datasheets/Nylon%20Extruded%206%20Black%20Data%20Sheet.pdf, 20 December 2023 acceseed.

- Unal, H.; Mimaroglu, A. Friction and wear performance of polyamide 6 and graphite and wax polyamide 6 composites under dry sliding conditions. Wear, Volume 289, 15 June 2012, Pages 132-137. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kanagaraj, G. Investigation on Mechanical and Tribological Behaviors of PA6 and Graphite-Reinforced PA6 Polymer Composites. Arab J Sci Eng, March 2016. [CrossRef]

- Uday, K.; Kumar, H.; Ravishankar, S.; Kalyan, S.; Paul, S. Stress Analysis on Spur Gear in Marine Applications by Fem Technique. A project review report submitted for the partial fulfillment of the Requirement for the award of the degree, DEPARTMENT OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING ANIL NEERUKONDA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY & SCIENCES (A) SANGIVALASA, VISAKHAPATNAM (District) – 531162 2020-2021, 4 January 2024 accessed.

- *** Medium, Available online: https://getwelsim.medium.com/multi-step-quasi-static-structural-finite-element-analysis-2a75e94ccde0, 4 January 2024 accessed.

- Voyer, J.; Klien, S.; Velkavrh, I.; Ausserer, F.; Diem, A. Static and Dynamic Friction of Pure and Friction-Modified PA6 Polymers in Contact with Steel Surfaces: Influence of Surface Roughness and Environmental Conditions. Lubricants 2019, 7(2), 17. [CrossRef]

- Vignesh S.; Johnney Mertens A. A deflection study of steel-polypropylene gear pair using finite element analysis. In Proceedings of the Materials Today, Volume 90, Part 1, 2023, Pages 36-42. [CrossRef]

- Bae, In.; Kissling, Ul. Comparison of strength ratings of plastic gears by VDI 2736 and JIS B 1759. Gearsolutions Magazine, 15 December, 2021, 5 January 2024 accessed.

- *** https://gearsolutions.com/features/comparison-of-strength-ratings-of-plastic-gears-by-vdi-2736-and-jis-b-1759/, 5 January 2024 accessed.

- IRSEL G. Bevel Gears Strength Calculation: Comparison ISO, AGMA, DIN, KISSsoft and ANSYS FEM Methods, Journal of the Chinese Society of Mechanical Engineers, Volume 42, No.3, pp315~323 (2021), 7 January 2024 accessed.

- Chena, G.; Liub, Y.; Lodewijksc, G.; Schotta, D.L. Experimental Research on the Determination of the Coefficient of Sliding Wear under Iron Ore Handling Conditions. Tribology in Industry, Volume 39, No. 3 (2017) 378-390. [CrossRef]

- Feulner, R.: Verschleiß trocken laufender Kunststoffge- triebe – Kennwertermittlung und Auslegung. Diss. Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, 2008, 7 January 2024 accessed.

- Diniță, A.; Neacșa, A.; Portoacă, A.I.; Tănase, M.; Ilinca, C.N.; Ramadan, I.N. Additive Manufacturing Post-Processing Treatments, a Review with Emphasis on Mechanical Characteristics. Materials 2023, 16, 4610. [CrossRef]

- Yabin Guan, Y.; Chen, J.; Fang, Z.; Shengyang, Hu. A quick multi-step discretization and parallelization wear simulation model for crown gear coupling with misalignment angle. Mechanism and Machine Theory, Volume 168, February 2022, 104576. [CrossRef]

- Pakhaliuk V.; Polyakov Al.; Kalinin M.; Kramar V. Improving the Finite Element Simulation of Wear of Total Hip Prosthesis’ Spherical Joint with the Polymeric Component. Procedia Engineering, Volume 100, 2015, Pages 539-548 . [CrossRef]

- Xiangzhen, Xue; Sanmin, Wang; Jie, Yu; Liyun, Qin Wear Characteristics of the Material Specimen and Method of Predicting Wear in Floating Spline Couplings of Aero-Engine. International Journal of Aerospace Engineering, Volume 2017, 2017, Article ID 1859167, 11 pages. [CrossRef]

- *** Gears for stress and selection, available online: https://faculty.mercer.edu/jenkins_he/documents/Gears4StressandSelection.pdf, 5 January 2024 accessed.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Nozzle thickness | 0.8 mm |

| Print height layer | 0.2 mm |

| Temperature of deposition bed | 80 °C |

| Melt temperature | 260 °C |

| Percentage of filling | 100 % |

| Parameters | Values | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of teeth | [z] | 37 |

| Facewidth (mm) | [b] | 17 |

| Normal module (mm) | [m] | 1.5 |

| Normal pressure angle (°) | [α] | 20 |

| Material | Own Input | PA6 (VDI 2736) |

| Accuracy grade in accordance with ISO1328:2020 | A6 | |

| Reference diameter (mm) | [d] | 55.43 |

| Tip diameter (mm) | [da] | 59.56 |

| Root diameter (mm) | [df] | 52.08 |

| Addendum coefficient | [haP] | 1.00 |

| Dendum coefficient | [hfP] | 1.25 |

| Centre distance (mm) | [a] | 56 |

| Parameters | Values | |

|---|---|---|

| Young's Modulus (in the scenario where the material is not heat-treated) |

[N/mm2] | 2,100÷2,800 [16,24] |

| Young's Modulus (in the scenario where the material is heat-treated) |

[N/mm2] | 6,000 |

| Poisson's Ratio | - | 0.4 [16] |

| Ultimate Tensile Strength (in the scenario where the material is not heat-treated) |

[N/mm2] | 48 [16,24] |

| Yield Strength (in the scenario where the material is not heat-treated) | [N/mm2] | 37 [16,24] |

| Ultimate Tensile Strength (in the scenario where the material is heat-treated, Tabel 16) |

[N/mm2] | 67 |

| Yield Strength (in the scenario where the material is heat-treated) | [N/mm2] | 58 |

| Density | [kg/m3] | 1,130 [9] |

| Wear factor | [mm3/Nm] | (7.8÷9) ·10-6 [18,19] |

| Bending stress [MPa] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KISSsoft | Lewis Bending Equation | Classical beam theory | FEA | Finite element size [mm] |

| 14.65 Analytical base on VDI 2736 Part 2 [10] |

11.14 |

14.16 |

9.25 | 0.25 |

| 10.98 | 0.22 | |||

| 11.53 | 0.18 | |||

| 14.9 | 0.1 | |||

| Stress type | Mathematical expression [10,25] | Coefficients used [10,25] |

Meaning of the coefficients [25] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bending stress |

[MPa] |

- tooth root load factor - application factor - dynamic factor - face load factor - transverse load factor |

|

|

- nominal tangential load [N] T - nominal torque of pinion [Nmm] d - reference circle of pinion [mm] |

|||

|

- ooth form factor - normal module [mm] - pressure angle - normal pressure angle - bending moment arm relevant to load application at the tooth tip [mm] |

|||

|

- stress correction factor - notch factor - Tooth root chord at the critical section [mm] |

|||

|

- contact ratio - transverse contact ratio |

|||

|

- helix angle factor - overlap ratio - helix angle |

|||

| - stress correction factor | |||

| Permissible bending stress |

[MPa] |

- llowable stress on the tooth root [MPa] - the required minimum safety factor for continuous operation is generally = 2.0. - maximum root strength [MPa] |

|

| Allowable bending stress |

defined as stress level with 10% failure probability [25] |

- fatigue strength (nominal root stress) [MPa] [32] | |

| Service life factor |

combined into [25] |

- life factor |

| Method | H [hr] Service Life |

KA Application factor |

SF Safety for tooth root stress |

Nominal stress at tooth root (MPa) |

Tooth root stress (MPa) |

Permissible tooth root stress (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA6 Untreated (E = 2,100 MPa) |

3024 | 1.25 | 4.83 | 11.72 | 14.65 (14.14 FEA) |

54.46 |

| PA6 160 °C annealing temperature (E = 6,000 MPa) |

3024 | 1.25 | 4.83 | 11.72 | 14.65 (14.31 FEA) |

54.46 |

| Method | H [hr] | SH Safety factor for contact stress on operating pitch circle |

σH0 Nominal contact stress (MPa) |

σH Contact stress at operating pitch circle (MPa) |

σHP Permissible contact stress (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA6 Untreated (E = 2,100 MPa) |

3,024 | 1.46 | 20.46 | 22.87 (20.887 FEA) |

35.26 |

| PA6 120 °C annealing temperature (E = 4,000 MPa) |

3,024 | 1.06 | 28.23 | 31.57 | 35.26 |

| PA6 140 °C annealing temperature (E = 5,000 MPa) |

2,973 | 0.95 | 31.57 | 35.29 | 35.26 |

| PA6 160 °C annealing temperature (E = 6,000 MPa) |

1,024 | 0.87 | 34.58 | 38.66 | 35.26 |

| PA6 | Local linear wear (µm) |

Wear, volume per tooth (mm³) |

Wear, mass per gear (g) |

Hertzian pressure (N/mm²) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | ||||

| PA6 - Untreated (E = 2,100 MPa) |

0.89 | 267 | 2.77 | 0.11 | 22.61 |

| PA6 - 120 °C annealing temperature (E = 4,000 MPa) |

0.90 | 251 | 2.66 | 0.11 | 42 |

| PA6 - 140 °C annealing temperature (E = 5,000 MPa) |

0.90 | 242 | 2.6 | 0.11 | 46 |

| PA6 - 160 °C annealing temperature (E = 6,000 MPa) |

0.90 | 231 | 2.53 | 0.11 | 54 |

| PA6 | Local linear wear (µm) |

Wear, volume per tooth (mm³) |

Wear, mass per gear (g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PA6 - Untreated (E = 2,100 MPa) |

264 | 3.93 | 0.164 |

| PA6 - 120 °C annealing temperature (E = 4,000 MPa) |

280.74 | 4.48 | 0.187 |

| PA6 - 140 °C annealing temperature (E = 5,000 MPa) |

271 | 4.54 | 0.19 |

| PA6 - 160 °C annealing temperature (E = 6,000 MPa) |

403 | 5.95 | 0.25 |

| PA6 | Wear, mass per gear -iterative calculation (g) |

Wear, mass per gear-experminetal calculaion (g) |

Percentage difference (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PA6 - Untreated (E = 2,100 MPa) |

0.164 | 0.141 | 4.17 |

| PA6 - 120 °C annealing temperature (E = 4,000 MPa) |

0.187 | 0.194 | 3.67 |

| PA6 - 140 °C annealing temperature (E = 5,000 MPa) |

0.19 | 0.197 | 3.61 |

| PA6 - 160 °C annealing temperature (E = 6,000 MPa) |

0.25 | 0.258 | 3.14 |

| Fatigue strength type |

PA6 Non-treated (E = 2,100 MPa) (retrieved from the KISSsoft database) |

PA6 Treated 120 °C annealing temperature |

PA6 Treated 160 °C annealing temperature |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 600 h | 3,000 h | 600 h | 3,000 h | 600 h | 3,000 h | |

| Fatigue strength under pulsating stress (nominal stress) [MPa] | 43.4 | 35.4 | 44 | 38 | 48 | 43 |

| Rolling contact fatigue strength [MPa] |

41.9 | 33.5 | 44 | 38 | 48 | 43 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).