1. Introduction

Boscia senegalensis (BS) Pers.) Lam. Ex Poir (Capparaceae), is a tree, native to the Sahel region of Africa. It is used as a local food plant in Africa. Fruits and seeds are eaten fresh or processed into various food products [

1]. BS is considered a potential solution to hunger and a buffer against famine in the Sahel region because of the variety of useful products it provides. It produces products for consumption, domestic needs, and medicinal and agricultural uses [

1].

BS is also a medicinal plant that has shown antihyperglycemic effects in animals. These plants are traditionally used in Chad to treat diabetes. Diabetes is a major public health problem, affecting an estimated 463 million people worldwide, according to the World Health Organization [

2].

The mechanisms of action of BS extracts on blood sugar levels are yet elucidated. BS involve stimulating the secretion of insulin, the hormone that regulates glucose metabolism and block the intestinal absorption of glucose by inhibition of SGLT1 [

3].

Pharmacological studies in albino rabbits made hyperglycaemic by oral administration of D-glucose, showed that BSP exhibited optimal activity at a dose of 250 mg/kg, without causing any adverse effects and this antihyperglycemic effect was attributed to Glucocapparin [

4,

5]. BS could be used as a potential source of natural anti-diabetic molecules, provided that their efficacy and safety in humans are confirmed.

The objective of this study was to evaluate clinical efficacy and safety of BSP on T2DM patients with Oral antihyperglycemic drugs resistant.

2. Materials and Methods

This was an observational cohort study conducted at the Chad-China Friendship Hospital in N’Djamena. Patients (332) were included in this preliminary study between October 2013 to December 2022. The study was approved by the National Ethics Committee (N°679/PR/PM/MSP /SE/SG/DHATC/SGH/SRH/13).

2.1. Study Design

Patients were eligible if they were confirmed 1) to be diagnosed T2DM before the date of signature of consent. 2) Patients treated by oral medication or/and insulin without significant amelioration of glycaemia or glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) more than 3 months. 3) Naive patients on diet regimen alone. 4) Patients diagnosed with HbA1c >7 % and ≤ 16 % in the first medical visit or with fasting blood glucose concentration more than ≥ 150 mg/dL. 5) Patients were more than 18 years old and informed consent signed on the date of the visit 1 in accordance with good clinical practices. We excluded patients suffering of heart problems, liver, and kidney dysfunction.

We evaluated the clinical benefits of the oral administration of BSP. All patients received 350 mg of BSP three times daily during the meal for 90 days. At days -7, 0, 30, 60 and 90, vein blood glucose and biochemical parameters were analysed. Urine glucose excretion (UGE) was collected for 24h beginning at day -1, 2, 15, 30. Follow-up visits occurred every month.

Quantitative data are presented as the mean ± S.E of n patients. ANOVA was performed followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison post-test performed using Graph Pad Prism version 8.0.2 for Windows (San Diego, CA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Benefit of Oral Administration of Boscisucrophage (BSP)

To facilitated collection and data analysis, patients were divided different categories according to their basal glycaemia, HbA1C and baseline glucose-lowering therapies (DGLT) during in visit 1. The effect of treatment of BSP was evaluated by measuring fasting blood vein glucose concentration in two categories of patients according to their basal fasting blood glucose concentration values (category 1, [350-250[ mg/dL, category 2 [249-150] mg/dL) at the day 0, 30, 60, 90. The concomitant administration of BS and oral antidiabetic medication induced significant reduction (p<0.001) of fasting blood vein glucose concentration. This reduction of blood glucose was not directly dependent of the basal value before de treatment. We note that when basal value of fasting blood glucose concentration was more than 200 mg/dL, BSP can reduce glycaemia to 125 mg/dL within a month, whereas this reduction was close to 100 mg/dL when the basal fasting blood glucose concentration was close to 150 mg/dL. We also noted that BSP can regularise fasting blood glucose concentration after one month in all categories of patient.

Concomitant oral administration of BSP and oral antidiabetic medication in different category of patient according to their basal value in fasting blood glucose concentration before the treatment was evaluated. The results shows that BSP can significantly reduce the fasting blood glucose concentration within the month (ap<0.0001). We studied the effect of BSP on glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) according to oral medication (baseline glucose-lowering therapies-BGLT-) of patient before oral administration of BSP and different category of basal value of HbA1c in visit 1.

The effect of BSP was evaluated on patients receiving previously BGLT. All the combination with BSP showed a significant reduction of blood concentration HbA1c suggesting the clinical benefit of the use of BSP in combination of oral antidiabetic drugs. Utilisation of BSP in combination with insulin or in combination with insulin plus Glimepiride plus Metformin showed a significant reduction of blood concentration HbA1c.

3.2. Effect of BSP on Serum Aminotransferase Activities and Creatinine

During the period of clinical trial, aminotransferase and creatinine were controlled with the focus to know if a combination of BSP and Oral antihyperglycemic drugs might affect the function of liver. The results showed a category of patient with the high concentration of serum aminotransferase, the combination of BSP and Oral antihyperglycemic drugs induced the reduction of hepatic aminotransferase to normal concentration, without affecting categories of patients with normal concentration of aminotransferase (

Table 2).

BSP in combination with oral antihyperglycemic drugs on hepatic alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) showed that BSP can significantly reduce the ALT and AST in categories of patients with high concentration of aminotransferase. In contrast BS did not affected aminotransferase of patient in normal range concentration.

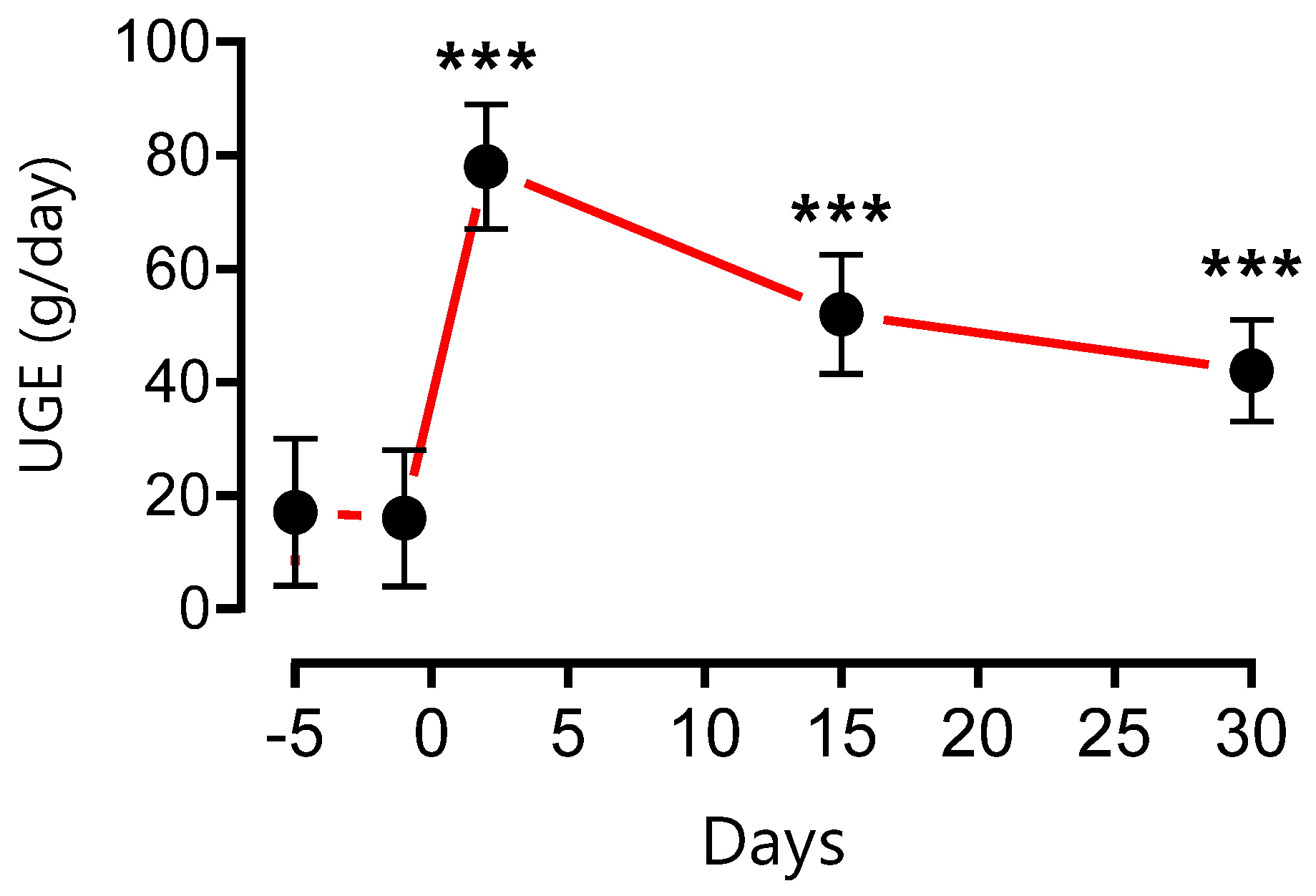

3.3. Effect of BSP on Urinary Glucose Excretion (UGE)

Oral administration of BSP 350 mg three times daily, significantly increased UGE over the next 24 h, as well as increases in the volume of urine (polyurea) and pollakiuria which are most marked the first days of treatment and returning slowly to baseline value by day 15 (

Figure 1).

3.4. Effect of BSP on Functional Adverse Effects Symptoms of T2DM

During medical visit, adverse effects, and different symptoms of T2DM were evaluated and noted such as thirst, vomiting, dry mouth, abdominal pain, impotent, headache, paraesthesia, dizziness, nausea, diarrhoea, constipation, fatigue, pollakiuria and urinary frequency (

Table 3). At the first endpoint we noted significant remission of major side effects of diabetes on patients.

4. Discussion

The general situation of type 2 diabetes is becoming worrying on a global scale. About 422 million people worldwide have diabetes, the majority living in low-and middle-income countries, and 1.5 million deaths are directly attributed to diabetes each year. Both the number of cases and the prevalence of diabetes have been steadily increasing over the past few decades. For people living with diabetes, access to affordable treatment, including insulin, is critical to their survival. There is a globally agreed target to halt the rise in diabetes and obesity by 2025 [

6] (who).

However, oral antidiabetics may not be effective for some people with type 2 diabetes, especially if they have poor glycaemic control or long duration of diabetes. In these cases, clinicians may prescribe a combination of oral antidiabetics with different modes of action to achieve better glucose control. Sometimes, oral antidiabetics may also be combined with insulin injections, which directly supply synthetic insulin to the body. The choice of medication and dosage depends on various factors, such as the individual’s blood glucose level, weight, kidney function, and potential side effects.

People with type 2 diabetes in low-income countries often do not have access to medicines. Some diabetics people cannot follow a healthy diet because of food shortages. The only solution left for these people is to use traditional treatments. Among the traditional antidiabetic treatments used in Chad and Cameroon are lost foods or famine foods such as BS.

The result clearly shows that BS directly inhibits the intestinal absorption of glucose in vitro in mice and it improved glucose tolerance and body weight in rats after acute and chronic oral administration in vivo [

3]. In addition, our findings lend support to use of BSP to reduce glycaemia and HbA1C in diabetic patients with Oral antihyperglycemic drugs resistant.

Clinical studies in humans were carried out in priority in diabetic patients resistant to oral antidiabetics under Baseline glucose-lowering therapies (BGLT). This choice was guided by ethical reasons. It was the first time that clinical studies were performed on diabetic patients. In order not to compromise the health of our patients and to give them every chance of normalizing their blood sugar levels, we have opted for the use of BSP as a therapeutic supplement. It was after the confirmation of the positive clinical benefits of the use of BSP that we extended the trials to naive patients with HbA1c (8.23 ± 2.68).

Patients were eligible if they were confirmed to be diagnosed (or suffering) type 2 diabetes before the date of signature of consent and treated by oral medication or/and insulin without significant amelioration of glycaemia or glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) more than 3 months except the naive patients, they were on diet regimen alone. The clinical studies showed that BSP improved Glycemic control in all the patients with type 2 diabetes. The reduction of blood glucose was effective after one week of treatment. On the other hand, the decrease in HbA1c is measurable after 30 days of treatment and remains below 7% after 60 days of treatment.

We collected urine from patients for 24 hours to measure urine glucose excretion (UGE). The result showed that BSP enhanced urinary glucose excretion. All patients confirmed significantly increased of volume of urine (polyurea) and frequency pollakiuria which are most marked the first days of treatment and returning slowly to baseline value by day 15. The weight loss, especially for overweight people was also observed during the treatment with BSP. The fact that BSP enhanced UGE suggests that BS or the active component (Glucocapparin) is a dual inhibitor of SGLT1/SGLT2. This may be one of the explanations for its effectiveness in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Indeed, several candidate antidiabetic molecules or molecules already prescribed in clinics are dual inhibitors of the sodium-glucose cotransporter SGLT1/SGLT2 such as Canagliflozin [

7], Empaglioflozin [

8,

9], Ipraglioflozin [

10,

11], Luseogliflozin [

12], Tofogliflozin [

13]. The IC

50) of BS in mouse intestine was close to above molecules and all of them are derivatives of Phloridzin (phloretin-2′-O-D-glucopyranoside) a bitter-tasting natural compound [

14], like Glucocapparin (Methyl glucosinolates) a main component of BS.

SGLT2 inhibitors have several benefits: (1) they lower blood glucose levels by increasing glucose excretion in the urine, which reduces the risk of severe hypoglycemia; (2) they do not require insulin to remove glucose from the blood, which eases the burden on pancreatic β-cells; (3) they may help with weight loss (4) and they may lower blood pressure by removing excess glucose in the urine. These benefits have been shown in recent studies of SGLT2 inhibitors [

15,

16,

17,

18]. SGLT1 inhibitors have 2 benefits (1) They reduces intestinal glucose absorption (both in small intestine and colon), (2) they partly reduce renal reabsorption of glucose, although this function represent only 10% [

19].

SGLT1 and SGLT2 are sodium-glucose cotransporters that play important roles in glucose homeostasis and offer novel targets for diabetes treatment. SGLT1 mediates glucose uptake in the small intestine and reabsorption in the kidney, while SGLT2 reabsorbs most of the filtered glucose in the kidney. Drugs that inhibit these transporters (such as dapagliflozin, canagliflozin, and empagliflozin) can lower blood glucose levels by reducing intestinal absorption and increasing urinary excretion of glucose. Clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of SGLT inhibitors as monotherapy or add-on therapy for type 2 diabetes, with additional benefits of weight loss and blood pressure reduction [

20]. The main limitations of SGLT inhibitors are their dependence on renal function and their increased risk of urinary and genital infections. Moreover, excessive inhibition of SGLT1 may cause gastrointestinal side effects. SGLT inhibitors have an insulin-independent mechanism of action that may provide long-term glucose control with low hypoglycemia risk in type 2 diabetes. They may also have a role in combination with insulin in type 1 diabetes [

21].

BSP causes a decrease in weight both in animals [

22] and in humans (personal communication). We think that reducing glucose absorption reduces the transformation of excess glucose and its storage as fat, but we also think that inhibiting intestinal glucose absorption by blocking SGLT1, could reduce the absorption of Chylomicrons. The reason for this is that: The chylomicrons that carry lipids are absorbed at the level of the intestinal villi. To pass into the lymphatic vessels they must pass through button junctions between the endothelial cells that are the walls of these vessels by increasing the hydrostatic pressure of the villi [

23]. We sincerely believe that by increasing the hydrostatic pressure, it promotes the passage of chylomicrons by increasing the openings of the button junctions. As glucose stimulates the absorption of sodium and therefore water, glucose should increase the local hydrostatic pressure and thus promote the absorption of lipids.

Overall, although observational studies can be useful for generating hypotheses and signals about drug effects, they are subject to many potential biases that can make it difficult to determine a causal relationship. For this reason, randomised clinical trials are generally considered the gold standard for assessing the efficacy and safety of a drug, as they minimise many of the biases mentioned above through randomisation. Observational studies should be interpreted with caution and their results confirmed by controlled clinical trials.

5. Conclusions

Our findings lend support to use of BSP to reduce glycaemia and HbA1c in diabetic patients with Oral antihyperglycemic drugs resistant without overt adverse effects. These data support of BSP-mediated dual SGLT1/SGLT2 inhibition as a novel mechanism of action in the treatment of T2DM. This study should be confirmed by controlled clinical trials.

6. Patents

The patent resulting from the work reported in this manuscript FR1201589

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation (BE, JMB, BG, JFD), data curation, formal analysis (BE, AO RN, JMB), funding acquisition, investigation (BI, IR, CT, PP, KT, NM, JC), methodology (BE, JMB, RN, ASA) project administration (BE, AAD), resources (BE, JFD), software (BE, JMB, AO), supervision (BE, JMB, JFD), validation, visualisation, writing—original draft, and writing—review & editing (BE, JMB).

Acknowledgement

The authors are thankful to the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2024R132), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- M.O. Belem, J. Yameogo, S. Ouédraogo, M. Nabaloum, Étude ethnobotanique de Boscia senegalensis (Pers.) Lam (Capparaceae) dans le Département de Banh, Province du Loroum, au Nord du Burkina Faso, J. Anim. Plant Sci. 34 (2017) 5390–5403.

- I.W. Suryasa, M. Rodríguez-Gámez, T. Koldoris, Health and treatment of diabetes mellitus, Int. J. Health Sci. 5 (2021). [CrossRef]

- B. Eto, Clinical Phytopharmacology Improving Health Care in Developing Countries, Schaltungsdienst Lange o.H.G., LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing, Berlin, 2019.

- M. Deli, E.B. Ndjantou, J.T. Ngatchic Metsagang, J. Petit, N. Njintang Yanou, J. Scher, Successive grinding and sieving as a new tool to fractionate polyphenols and antioxidants of plants powders: Application to Boscia senegalensis seeds, Dichrostachys glomerata fruits, and Hibiscus sabdariffa calyx powders, Food Sci. Nutr. 7 (2019) 1795–1806. [CrossRef]

- F. Dongmo, S.S. Dogmo, Y.N. Njintang, Aqueous extraction optimization of the antioxidant and antihyperglycemic components of Boscia Senegalensis using central composite design methodology, J Food Sci Nutr 3 (2017) 15. [CrossRef]

- Wold Health Organization, Diabetes, (2023). https://www.who.int/health-topics/diabetes#tab=tab_1.

- A. Lehmann, P.J. Hornby, Intestinal SGLT1 in metabolic health and disease, Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 310 (2016) G887–G898. [CrossRef]

- R. Grempler, L. Thomas, M. Eckhardt, F. Himmelsbach, A. Sauer, D.E. Sharp, R.A. Bakker, M. Mark, T. Klein, P. Eickelmann, Empagliflozin, a novel selective sodium glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor: characterisation and comparison with other SGLT-2 inhibitors, Diabetes Obes. Metab. 14 (2012) 83–90. [CrossRef]

- S.T.W. Cheng, L. Chen, S.Y.T. Li, E. Mayoux, P.S. Leung, The effects of empagliflozin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, on pancreatic β-cell mass and glucose homeostasis in type 1 diabetes, PloS One 11 (2016) e0147391. [CrossRef]

- A. Tahara, E. Kurosaki, M. Yokono, D. Yamajuku, R. Kihara, Y. Hayashizaki, T. Takasu, M. Imamura, L. Qun, H. Tomiyama, Pharmacological profile of ipragliflozin (ASP1941), a novel selective SGLT2 inhibitor, in vitro and in vivo, Naunyn. Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 385 (2012) 423–436. [CrossRef]

- S. Komatsu, T. Nomiyama, T. Numata, T. Kawanami, Y. Hamaguchi, C. Iwaya, T. Horikawa, Y. Fujimura-Tanaka, N. Hamanoue, R. Motonaga, SGLT2 inhibitor ipragliflozin attenuates breast cancer cell proliferation, Endocr. J. 67 (2020) 99–106. [CrossRef]

- H. Kakinuma, T. Oi, Y. Hashimoto-Tsuchiya, M. Arai, Y. Kawakita, Y. Fukasawa, I. Iida, N. Hagima, H. Takeuchi, Y. Chino, (1 S)-1, 5-anhydro-1-[5-(4-ethoxybenzyl)-2-methoxy-4-methylphenyl]-1-thio-d-glucitol (TS-071) is a potent, selective sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor for type 2 diabetes treatment, J. Med. Chem. 53 (2010) 3247–3261. [CrossRef]

- M. Suzuki, K. Honda, M. Fukazawa, K. Ozawa, H. Hagita, T. Kawai, M. Takeda, T. Yata, M. Kawai, T. Fukuzawa, Tofogliflozin, a potent and highly specific sodium/glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, improves glycemic control in diabetic rats and mice, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 341 (2012) 692–701. [CrossRef]

- L. Tian, J. Cao, T. Zhao, Y. Liu, A. Khan, G. Cheng, The bioavailability, extraction, biosynthesis and distribution of natural dihydrochalcone: Phloridzin, Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (2021) 962. [CrossRef]

- G. Musso, R. Gambino, M. Cassader, G. Pagano, A novel approach to control hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: Sodium glucose co-transport (SGLT) inhibitors. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials, Ann. Med. (2012). [CrossRef]

- B. Komoroski, N. Vachharajani, Y. Feng, L. Li, D. Kornhauser, M. Pfister, Dapagliflozin, a novel, selective SGLT2 inhibitor, improved glycemic control over 2 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 85 (2009) 513–519. [CrossRef]

- E. Ferrannini, S.J. Ramos, A. Salsali, W. Tang, J.F. List, Dapagliflozin monotherapy in type 2 diabetic patients with inadequate glycemic control by diet and exercise: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial, Diabetes Care 33 (2010) 2217–2224. [CrossRef]

- K. Katsuno, Y. Fujimori, Y. Ishikawa-Takemura, M. Isaji, Long-term treatment with sergliflozin etabonate improves disturbed glucose metabolism in KK-Ay mice, Eur. J. Pharmacol. 618 (2009) 98–104. [CrossRef]

- B. Zambrowicz, J. Freiman, P.M. Brown, K.S. Frazier, A. Turnage, J. Bronner, D. Ruff, M. Shadoan, P. Banks, F. Mseeh, LX4211, a dual SGLT1/SGLT2 inhibitor, improved glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 92 (2012) 158–169. [CrossRef]

- M. Kosiborod, M.A. Cavender, A.Z. Fu, J.P. Wilding, K. Khunti, R.W. Holl, A. Norhammar, K.I. Birkeland, M.E. Jørgensen, M. Thuresson, Lower risk of heart failure and death in patients initiated on sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors versus other glucose-lowering drugs: the CVD-REAL study (comparative effectiveness of cardiovascular outcomes in new users of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors), Circulation 136 (2017) 249–259. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Tahrani, A.H. Barnett, C.J. Bailey, SGLT inhibitors in management of diabetes, Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 1 (2013) 140–151. [CrossRef]

- D.O. Nohya, I.D. Soudy, M.A. Ahmat, A.-H. Sossal, M. Djimalbaye, A. Lenga, Anti-Obesity Effect of Boscia senegalensis in Rabbits, Food Nutr. Sci. 13 (2022) 568–576. [CrossRef]

- D.M. McDonald, Tighter lymphatic junctions prevent obesity, Science 361 (2018) 551–552. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).