1. Introduction

The prevalence of metabolic syndrome (MetS) is increasing in younger age groups, with adverse future outcomes [

1,

2,

3] including increased morbidity and mortality associated with cardiovascular disease [

2,

4].

MetS is defined as the presence of three or more of the following components: elevated triglycerides, blood pressure and fasting glucose, reduced high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and central fat deposition represented by waist circumference (WC), which may be a mandatory component for MetS, depending on the criteria adopted [

5,

6].

Researchers and societies use different criteria to define MetS [

1,

3]. Nevertheless, despite evaluating the same components, the criteria differ in two key aspects: the cut-off points used for each component, and the abnormal WC as mandatory to diagnose MetS [

3,

7].

Early diagnosis of MetS and its risk factors is essential for more effective interventions that lead to favorable outcomes [

3,

8]. However, to diagnose MetS according to the recommended criteria, some biochemical tests are required [

5,

6]. Although these are not particularly complex, they are invasive, require patients to return for medical appointments, and are costly to public healthcare system. In primary healthcare, the potential of non-invasive tests to screen patients likely to have MetS and, consequently, cardiometabolic risk would be an interesting alternative [

4].

The construction of predictive models, based on metabolic abnormalities that define MetS and other anthropometric measurements and using artificial neural networks (ANN), has demonstrated satisfactory performance in predicting MetS. These models can be used as supplementary tools to identifying cardiometabolic risk [

9,

10]. However, the predictive models developed to date are for Asian adults [

9] and are based on a single defining criterion for MetS [

4,

8,

9]. Moreover, these predictive models include invasive and costly variables, which may delaydiagnosis and treatment.

Thus, this study aims to predict MetS in adolescents using ANNs based on non-invasive demographic, clinical and anthropometric variables.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a cross-sectional study with dataset from the 1997-1998 birth cohort in São Luís-Maranhão, Brazil. Further details on the methodological approaches of this cohort can be found in Confortin et al. [

11].

The sample consisted of 2,515 adolescents assessed at 18-19 years old, of whom 687 were from the original cohort and 1,828 from an open cohort composed of people born in São Luís-MA in 1997. The purpose of including new participants was to increase the sample size. They were randomly selected from the Live Birth Information System (Sistema de Informações de Nascidos Vivos), including children born in 1997, and identified at schools and universities and through social networks. There were 451 participants excluded due to incomplete information or inconsistencies in the variables of interest. The final sample included 2,064 adolescents aged 18-19 from São Luís-Maranhão, Brazil.

The following variables were used in this study: age (years), sex (male or female), systolic blood pressure (SBP) (mmHg), diastolic blood pressure (DBP) (mmHg), weight (kg), height (cm), WC (cm), serum glucose (mg/dL), triglycerides (mg/dL), and HDL cholesterol (mg/dL).

For SBP and DBP, the mean value of three measurements was considered, taken after five minutes of rest, using the Omron HEM742INT device (Omron®, São Paulo, Brazil). Glycemia and serum levels of HDL-cholesterol and triglycerides were measured by the automated enzymatic colorimetric method using the Cobas c501 device (Roche®, São Paulo, Brazil). Weight was measured using a high-precision scale integrated with BOD POD Gold Standard equipment (COSMED Metabolic Company, Rome, Italy). The height was measured using a portable stadiometer (AlturaExata®, Belo Horizonte, Brazil). The WC was obtained from a three-dimensional image of the body using a 3-Dimensional Photonic Scanner ([TC] Labs®, Cary, USA). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as follows: body weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2).

To identify MetS in participants, the three most widely used specific criteria for adolescents were considered: 1. Cook et al. [

12]; 2. De Ferranti et al. [

13]; and 3. International Diabetes Federation (IDF) [

14]. These classifications considered elevated triglycerides, fasting glucose, SBP and/or DBP, WC, and low HDL cholesterol levels. The IDF criteria for identifying MetS require the presence of central obesity, as measured by WC, in addition to at least two metabolic abnormalities. The criteria established by Cook et al. and De Ferranti et al. require at least three of the five metabolic abnormalities, and central obesity is not mandatory, as in the IDF criteria (

Table 1).

The primary objective of this study is to propose a statistical model capable of predicting the probability of an adolescent developing MetS. The response variable of interest (y) was the presence of MetS, which takes the value “y=1” if the adolescent has MetS and “y=0” otherwise.

A multitude of feed-forward ANNs were used to build the predictive model. In addition to MetS components, the ANN considered the following input variables: age, sex, BMI, weight, and height. The output variable was the presence or absence of MetS (yes/no). The ANN implemented in this study is as follows:

ANN 1: Glycemia, WC, HDL, Triglycerides, SBP, DBP.

ANN 2: Age, Sex, Weight, Height, SBP, DBP.

ANN 3: Age, Sex, WC, SBP, DBP.

ANN 4: Age, Sex, BMI, SBP, DBP.

ANN 5: Age, Sex, WC, Weight, SBP, DBP.

ANN 1 included the same components as the criteria used in this study and was considered only as a reference network. Once the input variables were defined, the next step was to define the training and test sets. Given that three different criteria were considered for diagnosing MetS, three samples were constructed based on the prevalence of MetS according to the criterion adopted. Therefore, each sample included an equal number of adolescents with and without MetS (1:1). This sampling procedure was adopted because the criteria yielded disparate MetS prevalence rates. Adolescents without MetS were randomly selected. Each sample was divided into two subsamples: 70% for training and 30% for testing (

Table 2).

To avoid overfitting, k-fold cross-validation was applied to the training set. The objective of this technique is to randomly divide the sample under study into k subsets, where each subset serves as a training set, and the remaining subsets serve as validation sets for the network. In this study, the training set was divided into ten subsets. Nine of these were used to train the network, and one subset was employed to evaluate the network’s performance. The validation process was repeated ten times. Each subset was used as both training and testing sets.

Different feed-forward networks containing only one hidden layer were implemented. The distinguishing factor was the number of neurons in the input and hidden layers. To train the network, a backpropagation algorithm was employed with a maximum of 10,000 iterations, a learning rate of 0.25, and three distinct decay parameters (0.01, 0.1, and 0.5) to prevent overfitting. The activation function used in the hidden and output layers is a sigmoidal logistic function.

To avoid overfitting, k-fold cross-validation was applied to the training set. The objective of this technique is to randomly divide the sample under study into k subsets, where each subset serves as a training set, and the remaining subsets serve as validation sets for the network. In this study, the training set was divided into ten subsets. Nine of these were used to train the network.

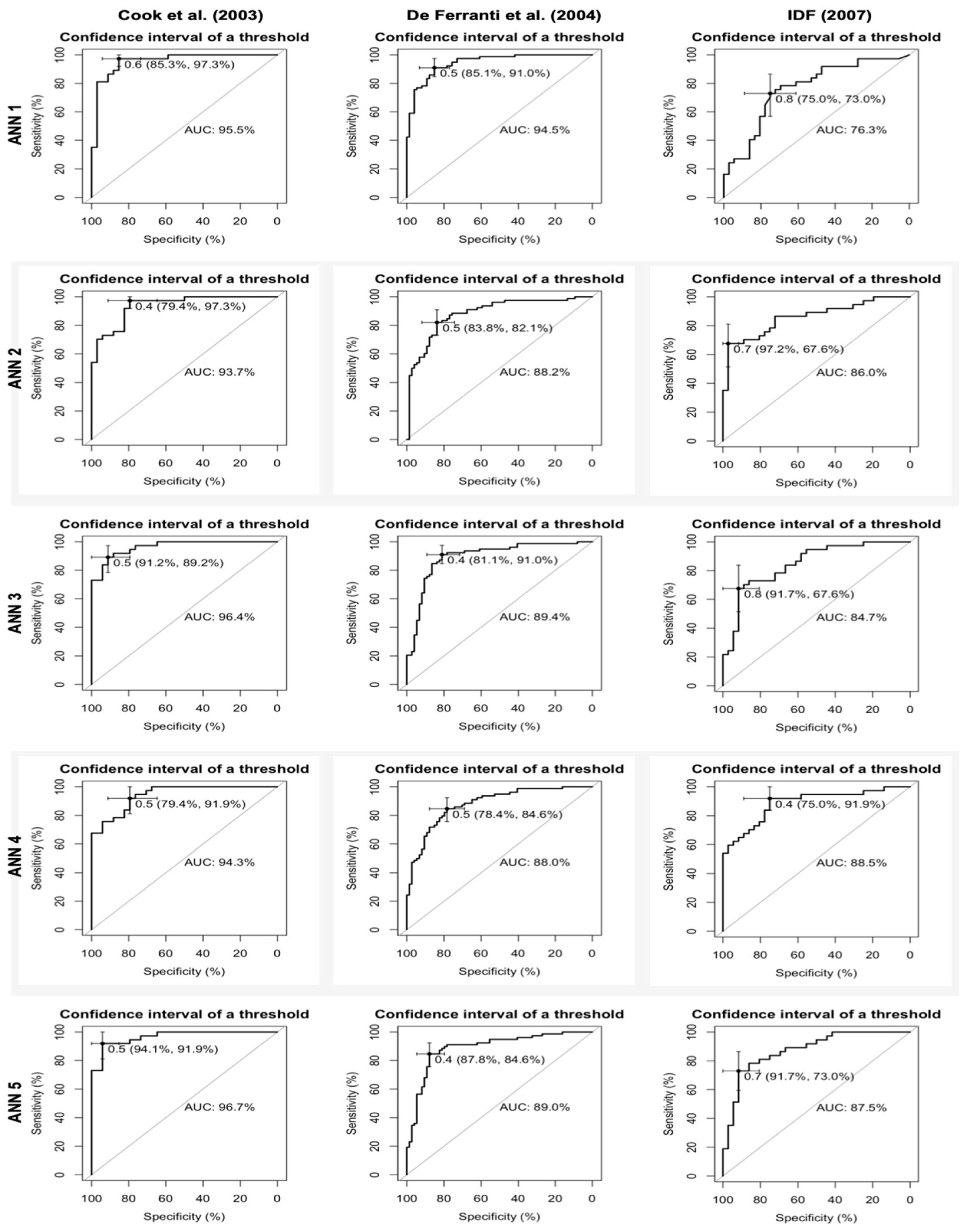

The generalization capacity of the trained ANN was evaluated using a test set with the following metrics: accuracy (ACUR), sensitivity (SENS), specificity (SPEC), and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. These metrics were derived from a confusion matrix (

Table 3) that calculated the following measures: True Positives (TPs), True Negatives (TNs), False Positives (FPs), and False Negatives (FNs).

The SENS was defined as the percentage of adolescents with MetS correctly classified by the ANN. It was calculated using SENS = TPs / (TPs + FNs). SPEC is the percentage of adolescents without MetS correctly classified. SPEC was calculated as follows: SPEC = TNs / (TNs + FPs). The ACUR was defined as the percentage of adolescents with and without MetS correctly classified. This was calculated using ACUR = (TPs + TNs) / (TPs + TNs + FPs + FNs).

A ROC curve was constructed, and the Area Under the Curve (AUC) was determined to assess the discriminatory power of the ANN. The ROC curve illustrates how the SENS and SPEC values of the method vary when different cut-off points are considered. The AUC ranges from 0 to 1. The higher the AUC, the more effective the evaluated method.

Analyses were performed in the open-acess statistical program R (R Core Team, 2023). The NeuralNetTools, caret, ggplot2, and pROC packages were used.

The data analyzed in this study is part of the larger project, “Determinantes ao Longo do Ciclo Vital da Obesidade, Precursores de Doenças Crônicas, Capital Humano e Saúde Mental: Uma Contribuição das Coortes de Nascimento de São Luís para o SUS” (Determinants throughout the Life Cycle of Obesity, Precursors of Chronic Diseases, Human Capital and Mental Health: A Contribution of the São Luís Birth Cohorts to the SUS), which was approved on 29/10/2015 by the Research Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of the Federal University of Maranhão (Process nº 1.302.489).

All the participants signed an Informed Consent Form. This study was conducted by the Declaration of Helsinki and Resolution nº 466/2012 requirements of the Conselho Nacional de Saúde (National Health Council) and its complementary provisions.

3. Results

The study sample comprised 2,064 adolescents aged 18-19, 50.9% of whom were female.

Table 4 presents the descriptive measures of the study variables.

The prevalence of MetS varies depending on the diagnostic criteria used. According to the IDF and Cook et al., the prevalence rates were very similar and less than half of those obtained from the definition adopted by De Ferranti et al. (5.9%, 5.7%, and 12.3%, respectively). Regardless of the criteria chosen, lipid profile inadequacy was the most common: low HDL cholesterol levels (44.5%, 35.2%, and 22.2% in De Ferranti et al., IDF and Cook et al., respectively) and hypertriglyceridemia (29.7% in De Ferranti et al. and 22.9% in Cook et al.), except IDF (8.4%). The IDF showed a higher prevalence of abnormal blood glucose levels (19.0%) than the other criteria (9.0% for both). Altered blood pressure showed slight variation between the criteria (9.4% to 11.5%), whereas abnormal WC was more prevalent according to the IDF (28.1%) and De Ferranti et al. (25.1%) criteria than according to the Cook et al. criteria (10.1%) (

Table 5).

Table 6 presents the ANN performance for the test and total samples, as evaluated using the three criteria employed in this study. Overall, all ANNs demonstrated satisfactory performance in predicting MetS in the adolescent sample, with the ACUR, SENS, and ESPEC values exceeding 70%.

When the criteria of Cook et al. was adopted, the ANN performed better. Among them, ANN 3 and 5 demonstrated the best performance. They used age, sex, WC, SBP, and DBP as input variables, and ANN 5 also used weight. According to the criteria of De Ferranti et al., ANN 3 also performed better than the others. When the criteria of IDF was employed, ANN 4, which used age, sex, BMI, SBP, and DBP, and ANN 5 exhibited superior performance.

Considering the total sample size (n=2,064), the ANN performance slightly declined when the criteria of Cook et al. was used. However, ANN 3 and ANN 5 still demonstrated superior performance compared to the others. When the criteria of De Ferranti et al. was used, the ANN performance demonstrated minimal variation, with ANN 5 and ANN 3 exhibiting particularly noteworthy performances. When the criteria of IDF and the entire sample were used, the performance of the ANNs improved. However, their performances remained inferior to those of the other two criteria. ANN 3 and ANN 5 demonstrated superior performances when the total sample was used, outperforming ANN 4, which performed better on testing set.

Figure 1 shows the ROC curves generated to assess the discriminatory power of the ANNs. The criteria of Cook et al. exhibited the highest AUC value, exceeding 90%. Additionally, ANN 5 demonstrated robust discriminatory power across all diagnostic criteria: Cook et al. (AUC = 96.7%), De Ferranti et al. (AUC = 89.0%), and IDF (AUC = 87.5%).

4. Discussion

This study proposed some ANNs to predict the change of developing MetS in adolescents. Different criteria have been considered for the diagnosis of MetS. The ANN implemented using the criteria of Cook et al. demonstrated superior ACUR and SENS. Furthermore, the ANN that included only age, sex, WC, weight, SBP, and DBP (ANN 5) demonstrated superior performance and discriminatory power in predicting MetS, regardless of the criteria employed. This was followed by a network that included age, sex, WC, SBP, and DBP (ANN 3). These ANNs include the same non-invasive components used to define MetS (WC, SBP, and DBP). Moreover, the ANNs used numerical values, thereby obviating the necessity of defining a cut-off point for identifying the risk of developing MetS.

WC is a practical and cost-effective anthropometric method, like BMI is. Nevertheless, WC exhibits an important limitation, as the diagnostic cut-off points vary according to sex and ethnic group [

15]. Considering this, the criteria employed in this study considered different cut-off points for WC according to sex and age. A comparison of the SENS between ANN 3 and 5 according to the adopted criteria revealed that the ANN that considered the criteria of Cook et al. for diagnosing MetS exhibited a higher SENS for the sample under study. This suggests that WC cut-off point can influence identifying adolescents with MetS.

Although WC is the most used anthropometric indicator for assessing abdominal fat associated with metabolic abnormalities [

7,

16], it may not be a significant and predominant metabolic abnormality for defining MetS in younger age groups. Therefore, including other anthropometric measurements is relevant for diagnosing MetS in this age group. The ANN 5 good performance shows that incorporating weight measurement in addition to WC enables a more precise identification of MetS in adolescents when the criteria of IDF is used.

The criteria adopted in this study use the same metabolic abnormalities to define MetS. However, their cut-off points and the necessity of WC differ in such a way as to determine significant variations [

1,

17]. Weihe and Weihrauch-Blüher [

6] argued that it is imperative to have a unified criterion for defining MetS in children and adolescents that considers pubertal stage, and ethnicity, besides age, and sex.

In this study, the proposed ANNs for predicting MetS in adolescents aged 18-19 demonstrated satisfactory performance. To date, no studies have been identified in the literature that propose developing and validating a predictive model that considers only non-invasive measurements (WC, SBP, and DBP) in this population.

Some studies have successfully applied artificial intelligence at the primary healthcare level to track future conditions and enable early prevention to improve outcomes and optimize resources [

10,

18,

19]. These studies demonstrated that artificial intelligence can be used to identify and predict future cardiovascular risks, allowing for implementation of early prevention strategies. This approach can potentially enhance the effectiveness of primary healthcare services and improve the population’s overall health.

In primary healthcare, an important challenge is the limited access to biochemical tests necessary for diagnosing MetS. In Brazil, access to these tests is limited, expensive, and time-consuming [

20]. This can hinder the ability of primary healthcare providers to diagnose and manage MetS effectively.

Furthermore, in clinical practice, a significant number of patients either do not return for follow-up appointments or do not provide laboratory test results in a timely manner, which can delay the diagnosis of MetS. Developing an ANN to predict the chance of a patient exhibiting MetS at the initial appointment would optimize the intervention flow and contribute to managing public resources (financial, human, and material), prioritizing and guiding patients who require biochemical tests to confirm the diagnosis of MetS.

Thus, ANN 5 allows predicting the chance of an adolescent exhibit MetS using simple and non-invasive measurements obtained during screening at a primary healthcare center, by accessible and inexpensive instruments. After that, it is possible to direct efforts towards early intervention to reduce cardiometabolic risks and disease burden. The healthcare system can better manage their care by identifying adolescents more likely to develop MetS. This will facilitate effective interventions, including undergoing the necessary tests, attending scheduled appointments, motivation to embrace the proposed changes and follow-up medical care. This approach is likely to result in higher intervention success rates.

The construction of ANNs for predicting MetS only considered adolescents aged 18-19. This may be a limitation because other age groups were not included in this life stage. However, the diagnostic criteria employed for MetS are limited to those applicable to this specified age range. Therefore, caution should be exercised when extrapolating the findings of this study to adolescents of various ages.

In contrast, this study used three diagnostic criteria for MetS to verify which criteria exhibited the most efficacious performance in predicting MetS. Most studies have utilized only a single criterion [4,8,16-17,21-22]. It was also determined that only input variables representing non-invasive measures that were fast and easy to obtain should be employed to serve as screening tools for MetS at the primary healthcare level. There is one study included only complex biochemical and cardiac parameters [

21].

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate that the use of non-invasive measures enables predicting chance of an adolescent developing MetS, thereby guiding the flow of care in primary healthcare and optimizing the management of public resources.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.J., A.K.F, V.S. and A.S.; methodology, A.C.J., A.K.F, V.S. and A.S.; formal analysis, A.C.J. and V.S.; investigation, A.C.J., E.S. and V.S.; data curation, A.C.J., E.S. and V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.J. and A.K.F.; writing—review and editing, A.K.F, E.S. and A.S.; supervision, A.K.F. and A.S.; project administration, A.K.F and A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the or Ethics Committee of University Hospital of the Federal University of Maranhão (Protocol nº 1.302.489, approved on 29/10/2015).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Melo, D.A.; Santos, A.M.; Silveira, V.N.C.; Silva, M.B.; Diniz, A.S. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in adolescents based on three diagnostic definitions: a cross-sectional study. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2023;67(5):1-8. [CrossRef]

- DeBoer, M.D. Assessing and Managing the Metabolic Syndrome in Children and Adolescents. Nutrients. 2019;11(1788). [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamad, D.; Raman, V. Metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6(4):397-407. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shami, I.; Alkhalidy, H.; Alnaser, K.; Mukattash, T.L.; Hourani, H.A.; Alzboun, T.; et al. Assessing metabolic syndrome prediction quality using seven anthropometric indices among Jordanian adults: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep. 2022;12(21043). [CrossRef]

- Orsini, F.; D’Ambrosio, F.; Scardigno, A.; Ricciardi, R.; Calabrò, G.E. Epidemiological Impact of Metabolic Syndrome in Overweight and Obese European Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Literature Review. Nutrients. 2023;15(3895). [CrossRef]

- Weihe, P.; Weihrauch-Blüher, S.; Metabolic Syndrome in Children and Adolescents: Diagnostic Criteria, Therapeutic Options and Perspectives. Curr Obes Rep. 2019;8(4):472-479. [CrossRef]

- Nagayama, D.; Sugiura, T.; Choi, S.-Y.; Shirai, K. Various Obesity Indices and Arterial Function Evaluated with CAVI—Is Waist Circumference Adequate to Define Metabolic Syndrome? Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2022;18:721-733. [CrossRef]

- El-Wahab, E.W.; Shatat, H.Z.; Charl, F. Adapting a Prediction Rule for Metabolic Syndrome Risk Assessment Suitable for Developing Countries. J Prim Care Community Health. 2019;10:1-13. [CrossRef]

- Hirose, H.; Takayama, T.; Hozawa, S.; Hibi, T.; Saito, I. Prediction of metabolic syndrome using artificial neural network system based on clinical data including insulin resistance index and serum adiponectin. Comput Biol Med. 2011;41(11):1051-1056. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.-H.; Lin, C.-M. The Utility of Artificial Neural Networks for the Non-Invasive Prediction of Metabolic Syndrome Based on Personal Characteristics. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(9288). [CrossRef]

- Confortin, S.C.; Ribeiro, M.R.C.; Barros, A.J.D.; Menezes, A.M.B.; Horta, B.L.; Victora, C.G.; et al. RPS Brazilian Birth Cohorts Consortium (Ribeirão Preto, Pelotas and São Luís): history, objectives and methods. Cad Saúde Pública. 2021;37(4):e 00093320. [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.; Weitzman, M.; Auinger, P.; Nguyen, M.; Dietz, W.H. Prevalence of a Metabolic Syndrome Phenotype in Adolescents: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(8):821-827. [CrossRef]

- De Ferranti, S.; Gauvreau, K.; Ludwig, D.S.; Neufeld, E.J.; Newburger, J.W.; Rifai, N. Prevalence of the Metabolic Syndrome in American Adolescents: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Circulation. 2004;110(16):2494-2497. [CrossRef]

- Zimmet, P.; Alberti, K.G.M.M.; Kaufman, F.; Tajima, N.; Silink, M.; Arslanian, S.; et al. The metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents—an IDF consensus report. Pediatr Diabetes. 2007;8(5):299-306. [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Berg, E.; Cheng, X.; Shen, W. How to best assess abdominal obesity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2018; 21(5):360-365. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, E.; Nah, E.-H.; Kim, S.; Cho, S. Relative Lean Body Mass and Waist Circumference for the Identification of Metabolic Syndrome in the Korean General Population. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(13186). [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Choi, J.R.; Koh, S.B. Development and Validation of prediction Model for Risk Reduction of Metabolic Syndrome by Body Weight control: A prospective population-based Study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(10006). [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Rincón, H.; Ríos-Blancas, M.; Ortega-Montiel, J.; Montoya, A.; Martinez-Juarez, L.A.; Lomelín-Gascón, J.; et al. MIDO GDM: an innovative artificial intelligence-based prediction model for the development of gestational diabetes in Mexican women. Sci Rep. 2023;13(6992). [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lv, B.; Chen, X.; Pan, Y.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Y.; et al. An early model to predict the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus in the absence of blood examination indexes: application in primary health care centers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(814). [CrossRef]

- Do Nascimento, L.C.; Viegas, S.M.F.; Menezes, C.; Roquini, G.R.; Santos, T.R. The SUS in the lives of Brazilians: care, accessibility and equity in the daily lives of Primary Health Care users. Physis. 2020;30(3):e300330. [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; He, J.; Gao, X.; Guo, H.; Wang, K.; Zhang, X.; et al. Metabolic syndrome in Xinjiang Kazakhs and construction of a risk prediction model for cardiovascular disease risk. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9):e 0202665. [CrossRef]

- Motamed, N.; Ajdarkosh, H.; Niya, M.H.K.; Panahi, M.; Farahani, B.; Rezaie, N.; et al. Scoring systems of metabolic syndrome and prediction of cardiovascular events: A population based cohort study. Clin Cardiol. 2022;45:641-649. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).