Submitted:

12 January 2023

Posted:

17 January 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

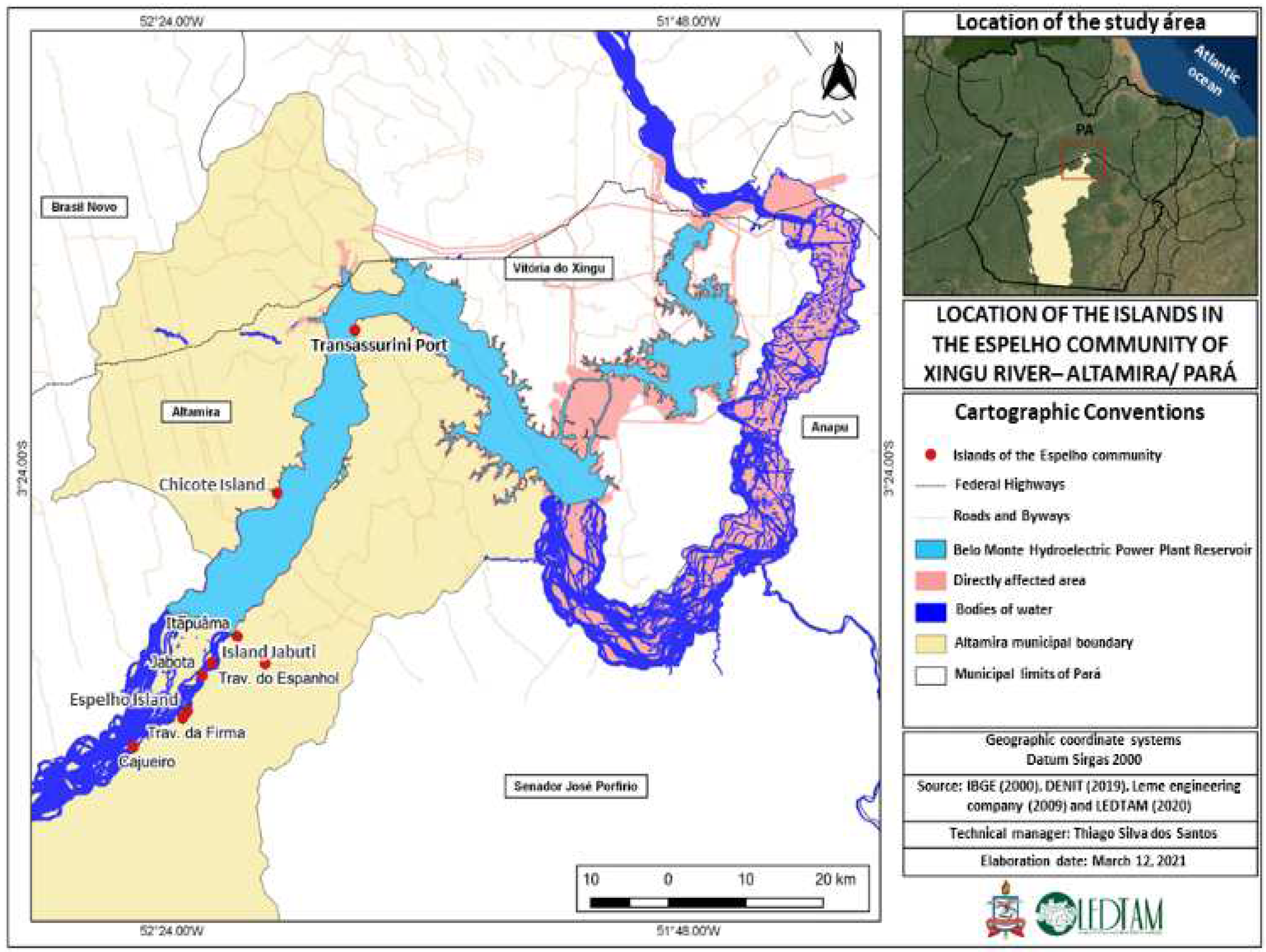

2.1. Participants

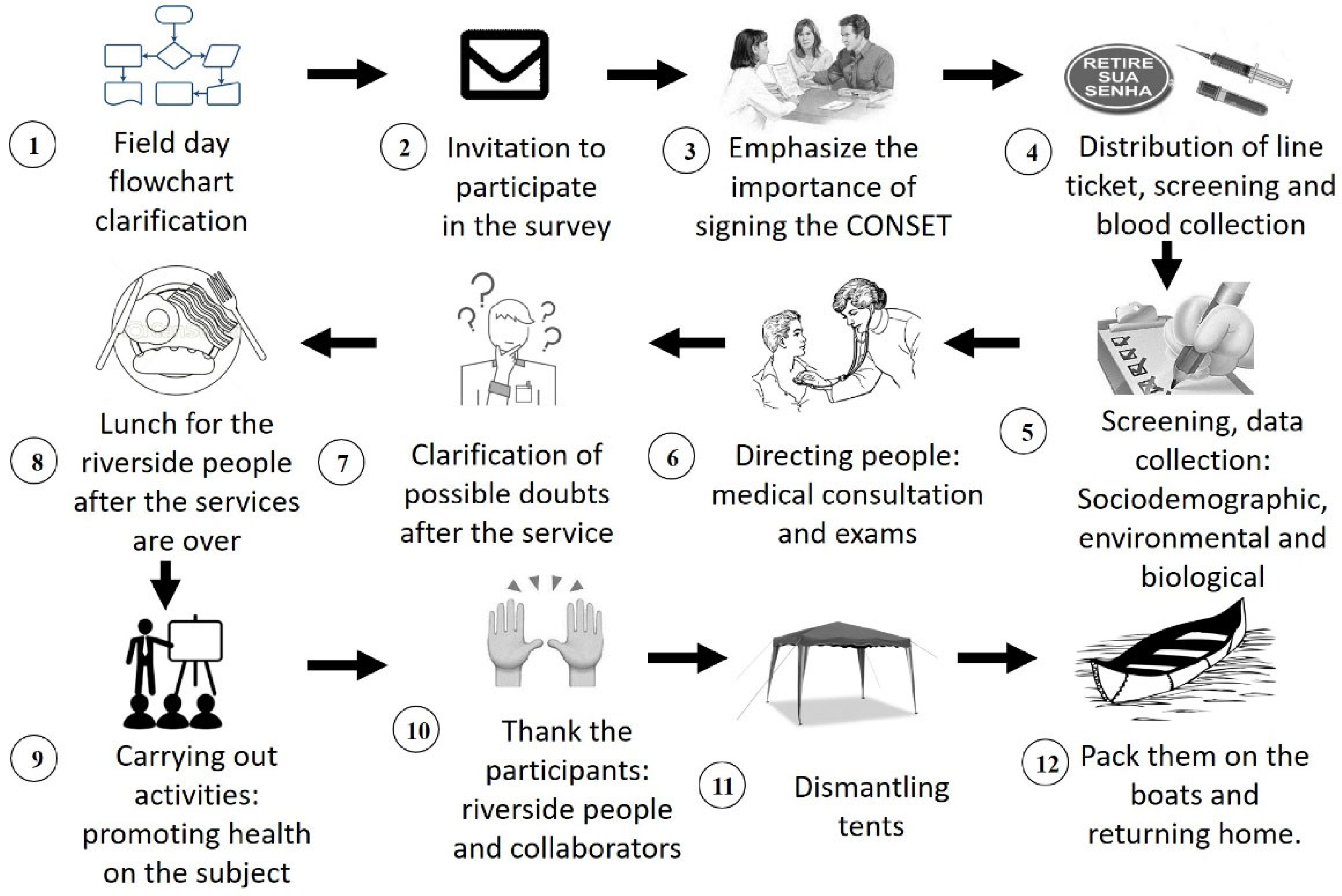

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Data Analysis

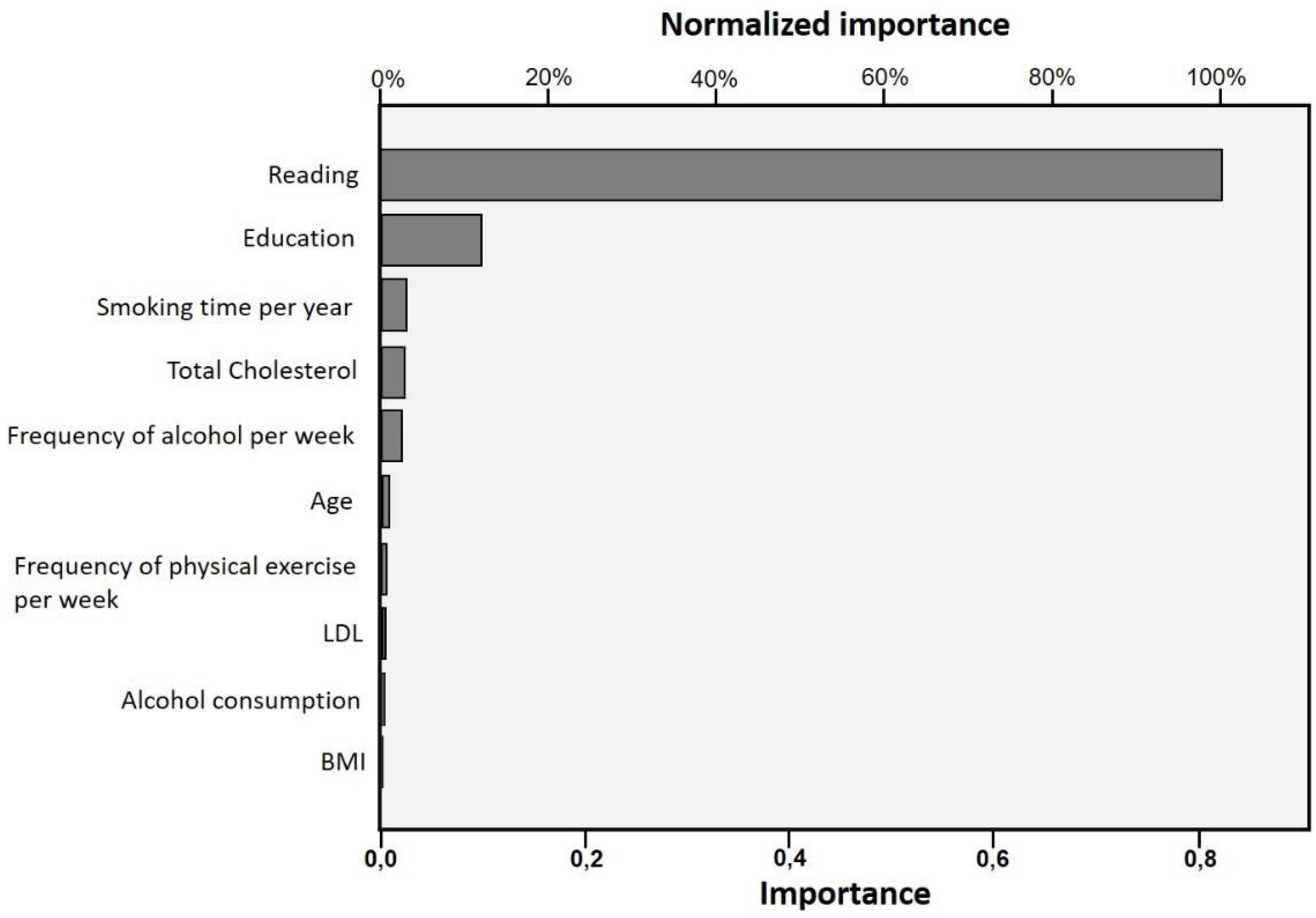

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brasil, M.S. Guidelines for the care of people with chronic diseases in health care networks and in priority lines of care. Health Care Department. Department of Primary Care. Brasilia: Ministry of Health Brasilia; 2013. Available in: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/diretrizes%20_cuidado_pessoas%20_doencas_cronicas.pdf (accessed Jan 15, 2021).

- GBD. Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016, 388(10053), 1659-724.

- Singhal, A. The global epidemic of noncommunicable disease: the role of early-life factors. J International nutrition: achieving millennium goals beyond, 2014; 78, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira B.F.A., Mourão D.S., Gomes N., Costa J.M.C., Souza A.V., Bastos W.R., Fonseca M.F., Mariani C.F., Abbad G., Hacon S.S. Prevalence of arterial hypertension in riverside communities on the Madeira River, Western Brazilian Amazon. J Cadernos de Saude Publica. 2013, 29(8), 1617-30. [CrossRef]

- Magalhães S.B., Cunha M.C. Study on the compulsory displacement of riverside dwellers in Belo Monte: SBPC report: São Paulo: SBPC, 2017; 448 p. Available in: http://portal.sbpcnet.org.br/publicacoes/a-expulsao-de-ribeirinhos-em-belo-monte-relatorio-da-sbpc/ (accessed nov 01, 2022).

- Arrifano G.P.F., Martin-Doimeadios R.D.C.R., Jiménez-Moreno M., Augusto-Oliveira M., Souza-Monteiro J.R., Paraense R., Machado C.R., Farina M., Macchi B., Do Nascimento J.L.M. Assessing mercury intoxication in isolated/remote populations: Increased S100B mRNA in blood in exposed riverine inhabitants of the Amazon. J Neurotoxicology. 2018, 68, 151-8. [CrossRef]

- Santos Sousa, I. , Sousa F.C., Sousa R.M.S. Living condition and water and sanitary situation in communities in the sphere of incluence of the gas pipeline Coari-Manaus in Macacapuru, state of Amazon, Brazil. J Hygeia-Revista Brasileira de Geografia Médica e da Saúde. 2009, 5(9), 88-98.

- Franco, E.C. , Santo C.E., Arakawa A.M., Xavier A., França M.d.L., De Oliveira A.N., Machado M.A.M.P., Bastos R.S., Bastos J.R.M., Caldana M.L. Health promotion on amazonic riverside population: experience report. J Revista CEFAC 2015, 17, 1521–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama A.S.M., Fernandes T.G., Parente R.C.P., Secoli S.R. Health survey in riverside communities in Amazonas, Brazil. J Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2018, 34(2), e00002817. [CrossRef]

- Hacon, S.S. , Dórea J.G., Fonseca M.F., Oliveira B.A., Mourão D.S., Ruiz C., Gonçalves R.A., Mariani C.F., Bastos W.R. The influence of changes in lifestyle and mercury exposure in riverine populations of the Madeira River (Amazon Basin) near a hydroelectric project. J International journal of environmental research public health. 2014, 11(3), 2437-55. [CrossRef]

- Katsuragawa, T.H. , Gil L.H.S., Tada M.S., Silva L.H.P. Endemic and epidemic diseases in Amazonia: Malaria and other emerging diseases in riverine areas of the Madeira River. A school case. J Estudos Avançados. 2008, 22(64), 111-41. Available in: https://www.scielo.br/j/ea/a/zcDwWg3XwwQWhCVR8vCLH3s/?lang=en&format=pdf.

- De Francesco, A. , Carneirom C. Atlas of the impacts of HPP Belo Monte on fisheries. São Paulo: Socio-environmental Institute; 2015. Available in: https://ox.socioambiental.org/sites/default/files/ficha-tecnica/node/202/edit/2018-06/atlas-pesca-bm.pdf (accessed Jun 21, 2021).

- Silveira, M. The implementation of hydroelectric plants in the Brazilian Amazon, socio-environmental and health impacts with the transformations in the territory: the case of the Belo Monte HPP [PhD in Geography]. University of Brasilia, Brasilia, 2016. Available in: https://repositorio.unb.br/handle/10482/20534 (accessed Jun 05, 2021).

- Gonçalves, A.C.O. , Cornetta A., Alves F., Barbosa L.J.G. Belém and Abaetetuba. In: The socio-environmental function of the Union's heritage in the Amazon, Alves F, editor, Brasília: Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (Ipea): 2016; p. 359. Available in: http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/handle/11058/6619.

- Lucas, E.W.M. , De Sousa F.A.S., Dos Santos F.D.S., Rocha-Júnior R.L., Pinto D.D.C., Da Silva V.P.R. Trends in climate extreme indices assessed in the Xingu river basin-Brazilian Amazon. J Weather Climate Extremes. 2021, 31, 100306. [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, J.M. , Dal’Asta A.P., Amaral S., Escada M.I.S., Monteiro A.M.V. The Middle and Lower Xingu: the response to the crystallization of different temporalities in the production of regional space. J Revista Brasileira de Estudos Urbanos e Regionais. 2017, 19(1), 148-63. [CrossRef]

- Weißermel, S. Towards a conceptual understanding of dispossession–Belo Monte and the precarization of the riverine people. J Novos Cadernos NAEA. 2020, 23, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil, M.S. The National Policy for the Comprehensive Health of rural, forest and water populations and the environment. Support for Participatory Management (DAGEP) Brasília: Ministry of Health; 2015. Available in: https://www.arca.fiocruz.br/bitstream/icict/42147/2/Cap_A%20Pol%C3%ADtica%20Nacional%20de%20Sa%C3%BAde%20Integral%20das%20Popula%C3%A7%C3%B5es%20do.pdf (accessed 14 jan 2022).

- Pontes, F.A.R. , Silva S.S.d.C., Bucher-Maluschke J.S., Reis D.C.d., Silva S.D.B.d. The ecological engagement in the context of an Amazon river Village. J Interamerican Journal of Psychology. 2008, 42(1), 1-10.

- De Rodrigues, L.R. Accessibility in the modular teaching organization system in elementary schools in riverside communities in the municipality of Abaetetuba. J Brazilian Journal of Development. 2020, 6(3), 13147-61. [CrossRef]

- Machado, F.S.N. , de Carvalho M.A.P., Mataresi A., Mendonça E.T., Cardoso L.M., Yogi M.S., Rigato H.M., Salazar M. Use of telemedicine technology as a strategy to promote health care of riverside communities in the Amazon: experience with interdisciplinary work, integrating NHS guidelines. J Ciencia saude coletiva. 2010, 15(1), 247-54. [CrossRef]

- Arrifano, G.P. , Alvarez-Leite J.I., Macchi B.M., Campos N.F., Augusto-Oliveira M., Santos-Sacramento L., Lopes-Araújo A., Souza-Monteiro J.R., Alburquerque-Santos R., Do Nascimento J.L.M. Living in the southern hemisphere: metabolic syndrome and its components in Amazonian riverine populations. J Journal of clinical medicine. 2021, 10(16), 3630. [CrossRef]

- Anjana, R.M. , Baskar V., Nair A.T.N., Jebarani S., Siddiqui M.K., Pradeepa R., Unnikrishnan R., Palmer C., Pearson E., Mohan V., et al. Novel subgroups of type 2 diabetes and their association with microvascular outcomes in an Asian Indian population: a data-driven cluster analysis: the INSPIRED study. J BMJ Open Diabetes Research. 2020, 8(1), e001506. [CrossRef]

- Hillesheim, E. , Ryan M.F., Gibney E., Roche H.M., Brennan L., metabolism. Optimisation of a metabotype approach to deliver targeted dietary advice. J Nutrition. 2020, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tallman, D.A. , Latifi E., Kaur D., Sulaheen A., Ikizler T.A., Chinna K., Mat Daud Z.A., Karupaiah T., Khosla P. Dietary patterns and health outcomes among African American maintenance hemodialysis patients. J Nutrients. 2020, 12, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, T.P. Sample size determination and power: John Wiley & Sons, 2013; 1118439228. 400 p.

- Yamane, T. Statistics, An Introductory Analysis, 1967: J New York Harper Row CO. USA, 1967; 919 p.

- Cabral, M.M. , Venticinque E.M., Rosas F.C.W. Perception of riverine people in relation to the performance and management of two distinct categories of protected areas in the Brazilian Amazon. J Biodiversidade Brasileira-BioBrasil. 2014, 1, 199-210.

- Feio, C.M.A. , Fonseca F.A., Rego S.S., Feio M.N., Elias M.C., Costa E.A., Izar M.C., Paola Â.A., Carvalho A.C. Lipid profile and cardiovascular risk in Amazonians. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2003, 81(6), 592-5. Available in: https://www.scielo.br/j/abc/a/kcz8gg3kBQQWJyLFbrWKFKw/?format=pdf&lang=pt.

- Murrieta, R.S.S. Dialectic of flavor: food, ecology and daily life in riverside communities on the island of Ituqui, Baixo Amazonas, Pará. J Revista Antropologia. 2001, 44, 39–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulvers, K. , Scheuermann T.S., Romero D.R., Basora B., Luo X., Ahluwalia J.S. Classifying a smoker scale in adult daily and nondaily smokers. J nicotine tobacco research. 2014, 16(5), 591-9. [CrossRef]

- SBAC. Brazilian Consensus for the Standardization of Laboratory Determination of Lipid Profile. Brazilian Society of Clinical Analysis; 2016. Available in: https://www.sbac.org.br/blog/2016/12/10/consenso-brasileiro-para-a-normatizacao-da-determinacao-laboratorial-do-per%EF%AC%81l-lipidico/ (accessed abr 27, 2021).

- SBD. Guidelines of the Brazilian Society of Diabetes 2017-2018. Brazilian Society of Diabetes: Publisher Clannad, São Paulo; 2017. Available in: https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/4925460/mod_resource/content/1/diretrizes-sbd-2017-2018.pdf (accessed abr 20, 2021).

- Teknomo, K. K-means clustering tutorials 2007. Available from: http://sigitwidiyanto.staff.gunadarma.ac.id/Downloads/files/38034/M8-NotekMeans (acessed mai 05, 2021).

- Mahmoud, P. K-Means Clustering - Data Algorithms: O´Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472, 2015; 725 p.

- Chatterji, P. , Joo H., Lahiri K. Racial/ethnic-and education-related disparities in the control of risk factors for cardiovascular disease among individuals with diabetes. J Diabetes Care. 2012, 35(2), 305-12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, P.A.N. , Sichieri R. Waist-hip ratio and dietary factors in adults. J Revista Saúde Pública. 2002, 36, 198-204. [CrossRef]

- Merz, C.N.B. , Ramineni T., Leong D. Sex-specific risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women-making cardiovascular disease real. J Current opinion in cardiology. 2018, 33, 500–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.U. , Lone A.N., Khan M.S., Virani S.S., Blumenthal R.S., Nasir K., Miller M., Michos E.D., Ballantyne C.M., Boden W.E. Effect of omega-3 fatty acids on cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J EClinicalMedicine 2021, 38, 100997. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Sacramento, L. , Arrifano G.P., Lopes-Araújo A., Augusto-Oliveira M., Albuquerque-Santos R., Takeda P.Y., Souza-Monteiro J.R., Macchi B.M., do Nascimento J.L.M., Lima R.R. Human neurotoxicity of mercury in the Amazon: A scoping review with insights and critical considerations. J Ecotoxicology environmental safety 2021, 208, 111686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basta, P.C. , Viana P.V.d.S., Vasconcellos A.C.S.d., Périssé A.R.S., Hofer C.B., Paiva N.S., Kempton J.W., Ciampi de Andrade D., Oliveira R.A.A.d., Achatz R.W. Mercury exposure in Munduruku indigenous communities from Brazilian Amazon: Methodological background and an overview of the principal results. J International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health 2021, 18, 9222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneses, H.N.M. , Oliveira-da-Costa M., Basta P.C., Morais C.G., Pereira R.J.B., De Souza S.M.S., Hacon S.S. Mercury contamination: a growing threat to riverine and urban communities in the Brazilian Amazon. J International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health 2022, 19, 2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza-Araujo, J. , Andrades R., Hauser-Davis R., Lima M., Giarrizzo T. Before the Dam: A Fish-Mercury Contamination Baseline Survey at the Xingu River, Amazon Basin Before the Belo Monte Dam. J Bulletin of Environmental Contamination Toxicology 2022, 108, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2 rd ed: Academic press, 2013; 1483276481. 579 p.

- Fritz, C.O. , Morris P.E., Richler J.J. Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. J Journal of experimental psychology: General. 2012, 141(1), 2-18. [CrossRef]

- Russell S., Norvig P. Artificial intelligence: a modern approach. 3rd ed: Upper Saddle River (NJ): Prentice Hall Press, 2010; 9780132071482. 1132 p.

- SBC. Brazilian Society of Cardiology - 7th Brazilian Guideline on Arterial Hypertension. Arquivos Brasileiros Cardiologia. 2016, 107(3), 1-103. Available in: http://publicacoes.cardiol.br/2014/diretrizes/2016/05_HIPERTENSAO_ARTERIAL.pdf.

- WHO. Waist circumference and waist–hip ratio: report of a WHO expert consultation. World Health Organization - Geneva; 2008. Available in: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44583/9789241501491_eng.pdf;jsessionid=2BE502B0C60142042631C73640261857?sequence=1 (accessed jan 15, 2022).

- Mariosa, D.F. , Ferraz R.R.N., Santos-Silva E.N. Influence of socio-environmental conditions on the prevalence of systemic arterial hypertension in two riverside communities in the Amazon, Brazil. J Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2018, 23, 1425–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohlsson, A. , Eckerdal N., Lindahl B., Hanning M., Westerling R. Non-employment and low educational level as risk factors for inequitable treatment and mortality in heart failure: a population-based cohort study of register data. J BMC public health. 2021, 21(1), 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Rarau, P. , Pulford J., Gouda H., Phuanukoonon S., Bullen C., Scragg R., Pham B.N., McPake B., Oldenburg B. Socio-economic status and behavioural and cardiovascular risk factors in Papua New Guinea: A cross-sectional survey. J PloS one. 2019, 14(1), e0211068. [CrossRef]

- Rosengren, A. , Smyth A., Rangarajan S., Ramasundarahettige C., Bangdiwala S.I., AlHabib K.F., Avezum A., Boström K.B., Chifamba J., Gulec S. Socioeconomic status and risk of cardiovascular disease in 20 low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries: the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiologic (PURE) study. J The Lancet Global Health. 2019, 7(6), e748-e60. [CrossRef]

- Fard, N.A. , Morales G.F., Mejova Y., Schifanella R. On the interplay between educational attainment and nutrition: a spatially-aware perspective. J EPJ Data Science. 2021, 10(1), 18. [CrossRef]

- Arrighi, E. , Ruiz de Castilla E., Peres F., Mejía R., Sørensen K., Gunther C., Lopez R., Myers L., Quijada J., Vichnin M. Scoping health literacy in Latin America. J Global Health Promotion. 2022, 29(2), 78-87. [CrossRef]

- De Azevedo, P.L. , Freitas S.R.S. Prevalence of major cardiometabolic diseases in the riverine populations from the interior of the State of Amazonas, Brazil. J Acta Scientiarum Health Sciences. 2018, 40. [CrossRef]

- Machado, C.L.R. , Crespo-Lopez M.E., Augusto-Oliveira M., Arrifano G.P., Macchi B.M., Lopes-Araújo A., Santos-Sacramento L., Souza-Monteiro J.R., Alvarez-Leite J.I., De Souza C.B.A. Eating in the Amazon: nutritional status of the riverine populations and possible nudge interventions. J Foods. 2021, 10(5), 1015. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, P.L. Prevalence of the main chronic non-communicable diseases in riverside populations in the interior of Amazonas [Course Conclusion Paper]. State University of Amazonas, Manaus, 2017. Available in: http://repositorioinstitucional.uea.edu.br/handle/riuea/523 (accessed jan 15, 2022).

- Relvas, A. , Camargo J., Basano S., Camargo L.M.A., Development. Prevalence of chronic noncommunicable diseases and their associated factors in adults over 39 years in riverside population in the western Brazilian amazon region. J Journal of Human Growth. 2022, 32, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omare, M.O. , Kibet J.K., Cherutoi J.K., Kengara F.O. A review of tobacco abuse and its epidemiological consequences. J Journal of Public Health. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, S.C. , Burgess S. Appraising the causal role of smoking in multiple diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of Mendelian randomization studies. J EBioMedicine 2022, 82, 104154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, M.C. , Borgonovi F. Education, alcohol use and abuse among young adults in Britain. J Social science & Medicine. 2010, 71(1), 143-51. [CrossRef]

- Jefferis, B. , Manor O., Power C. Cognitive development in childhood and drinking behaviour over two decades in adulthood. J Journal of Epidemiology Community Health. 2008, 62, 506–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, L.E.S. , Helman B., Luz e Silva D.C., Aquino É.C., Freitas P.C., Santos R.O., Brito V.C.A., Garcia L.P., Sardinha L.M.V. Prevalence of heavy episodic drinking in the Brazilian adult population: National Health Survey 2013 and 2019. J Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde. 2022, 31. [CrossRef]

- Plens, J.A. , Valente J.Y., Mari J.J., Ferrari G., Sanchez Z.M., Rezende L.F. Patterns of alcohol consumption in Brazilian adults. J Scientific reports. 2022, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira, W.P. , Caetano K.A.A., Brandão G.C.G., Freire M.E.M., Reis R.K., Oliveira e Silva A.C. Harmful alcohol consumption and associated factors in riverine communities. 2022. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macinko, J. , Mullachery P., Silver D., Jimenez G., Neto O.L.M. Patterns of alcohol consumption and related behaviors in Brazil: Evidence from the 2013 National Health Survey (PNS 2013). J PLoS one. 2015, 10(7), e0134153. [CrossRef]

- Sales, F.M.A.M. , Silva L.M.C., Oliveira A.P.P., Reis R.C., Guerreiro J.F. Risk of excess weight/body fat and dyslipidemia associated with hemoglobin A2 levels. Revista Paraense de Medicina. 2014, 28(4), 57-64.

- Adams, C. , Murrieta R., Neves W.A. Amazonian caboclo societies: modernity and invisibility: Annablume, 2006; 8574196444. 364 p. São Paulo.

- Tomita, L.Y. , Cardoso M.A. Assessment of the food list and serving size of a Food Frequency Questionnaire in an adult population. J Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 2002; 18, 1747–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.L. , Begossi A. Biodiversity, food consumption and ecological niche dimension: a study case of the riverine populations from the Rio Negro, Amazonia, Brazil. J Environment, Development Sustainability. 2009, 11(3), 489-507. [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, S.T. , Singh-Manoux A., Pentti J., Madsen I.E., Sabia S., Alfredsson L., Bjorner J.B., Borritz M., Burr H., Goldberg M. Association of healthy lifestyle with years lived without major chronic diseases. J JAMA internal medicine. 2020, 180(5), 760-8. [CrossRef]

- Peres, M.A.C. Old age and illiteracy, a paradoxical relationship: educational exclusion in rural contexts in the Northeast region. J Sociedade e estado. 2011, 26, 631–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez-Rojas, W.V. , Martín D., Miralles B., Recio I., Fornari T., Cano M.P. Composition of Brazil Nut (Bertholletia excels HBK), Its Beverage and By-Products: A Healthy Food and Potential Source of Ingredients. J Foods. 2021, 10(12), 3007. [CrossRef]

- Matos, Â.P. , Matos A.C., Moecke E.H.S. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and nutritional quality of five freshwater fish species cultivated in the western region of Santa Catarina, Brazil. J Brazilian Journal of Food Technology 2019, 22, e2018193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataveli, G. , Chaves M., Guerrero J., Escobar-Silva E.V., Conceição K., De Oliveira G. Mining Is a Growing Threat within Indigenous Lands of the Brazilian Amazon. J Remote Sensing. 2022, 14(16), 4092. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo-Santos, V.M. , Arcifa M.S., Brito M.F., Agostinho A.A., Hughes R.M., Vitule J.R., Simberloff D., Olden J.D., Pelicice F.M. Negative impacts of mining on Neotropical freshwater fishes. J Neotropical Ichthyology. 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrifano, G.P. , Martín-Doimeadios R.C.R., Jiménez-Moreno M., Ramírez-Mateos V., da Silva N.F., Souza-Monteiro J.R., Augusto-Oliveira M., Paraense R.S., Macchi B.M., Do Nascimento J.L.M. Large-scale projects in the amazon and human exposure to mercury: The case-study of the Tucuruí Dam. J Ecotoxicology environmental safety. 2018, 147, 299-305. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.F. , Singh K., Chan H.M. Mercury exposure, blood pressure, and hypertension: A systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis. J Environmental health perspectives. 2018, 126(07), 076002. 0760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J. , Pan Y., Tang Z., Song Y. Mercury poisoning presenting with hypertension: report of 2 cases. J The American Journal of Medicine. 2019, 132(12), 1475-7. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.F. , Lowe M., Chan H.M. Mercury exposure, cardiovascular disease, and mortality: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. J Environmental research. 2021, 193, 110538. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, J.P.S. , Lopes I.S.S., Henriques C.E.L., Minekawa T.B., Bastos M.S.C.B.O., editors. Katuana from Baía do Guajará: diabetes and self-reported arterial hypertension in a riverside population of Combú. III Congress on Health Education in the Amazon (COESA); 2014; Federal University of Pará, Pará, Brazil.

- Rodrigues, D.N. , Mussi R.F.d.F., Almeida C.B.d., Nascimento Junior J.R.A., Moreira S.R., Carvalho F.O. Sociodemographic determinants associated with the level of physical activity of Bahian quilombolas, 2016 survey. J Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde 2020, 29, e2018511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanzeler, F.S.d.C. Physical activity and associated factors in riverside adolescents in the Amazon [Master’s Degree]. University of Brasilia, Brasília, 2017. Available in: https://repositorio.unb.br/handle/10482/24652 ((accessed jan 15, 2021).

- Wanzeler, F.S.d.C. , Nogueira J.A.D. Physical activity in rural populations of Brazil: a review of literature. Revista Brasileira de Ciência e Movimento. 2019, 27(4), 228-40.

- Cercato, C. , Mancini M.C., Arguello A.M.C., Passos V.Q., Villares S.M.F., Halpern A. Systemic hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia in relation to body mass index: evaluation of a Brazilian population. J Revista do Hospital das Clínicas. 2004, 59(3), 113-8. [CrossRef]

- Costa-Font, J. , Gil J., Biology H. Obesity and the incidence of chronic diseases in Spain: a seemingly unrelated probit approach. Economics & Human Biology. 2005, 3(2), 188-214. [CrossRef]

- Brasil, M.S. Protocols of the Food and Nutrition Surveillance System - SISVAN in health care. Primary Care, Health Care Secretariat. Brasília: Ministry of Health; 2008. Available in: http://189.28.128.100/dab/docs/portaldab/publicacoes/protocolo_sisvan.pdf (accessed fev 10, 2022).

- de Araújo, I.M. , Antunes Paes N. Quality of anthropometric data of hypertensive users seen at the family health program and its correlation with risk factors. Texto & Contexto Enfermagem. 2013, 22(4), 1030-40.

- Pereira, R.A. , Sichieri R., Marins V.M. Razão cintura/quadril como preditor de hipertensão arterial. J Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 1999, 15, 333-44. Available in: https://www.scielo.br/j/csp/a/QL4w8KBLPPh9sTds769ZS9g/?lang=pt&format=pdf.

- Rodrigues, J.M.P. , Da Silva G.P. The Modular Teaching Organization System (MTOS) from the perspective of graduates in the municipality of Breves - Pará. J Revista Brasileira de Educação do Campo. 2018, 3(1), 260-86. [CrossRef]

| Descriptors | Group 1 n=39 |

Group 2 n=47 |

Effect size |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC | ||||

| Sex | F = 51.3% | F = 48.9% | Φ = 0.02 | 0.83 |

| M = 48.7% | M = 51.1% | |||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Asian | 2.6% | 4.3% | V = 0.23++ | 0.35 |

| White | 17.9% | 21.3% | ||

| Indigenous | 2.6% | 6.4% | ||

| Mixed race | 43.6% | 53.2% | ||

| Black | 33.3% | 14.9% | ||

| Education | ||||

| No education | 59.0% a | 0.0% a | V = 0.77+++ | < 0.001*** |

| Initial Elementary School | 41.0% | 40.5% | ||

| Final Elementary School | 0.0% b | 46.8% b | ||

| High School | 0.0% c | 10.6% c | ||

| University graduate | 0.0% | 2.1% | ||

| Reading | ||||

| No | 100.0% | 0.0% | Φ = 1.00+++ | < 0.001*** |

| Yes | 0.0% | 100.0% |

| Descriptors | Group 1 n=39 |

Group 2 n=47 |

Effect size |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEHAVIORAL | ||||

| Smoking Time/year | 0.0 (0-15) | 0.0 (0-0) | 0.04 | < 0.05* |

| Number of cigarettes/day | 0.0 (0-0) | 0.0 (0-0) | 0.00 | 0.50 |

| Frequency Alcohol/week | 0.0 (0-0) | 0.0 (0-3) | 0.04 | < 0.05* |

| Exercise Frequency | 0.0 (0-0) | 1.5 (0-4) | 0.11+ | < 0.01** |

| Fish Consumption/week | 3.0 (2-6) | 4.0 (2-6) | 0.01 | 0.32 |

| BIOLOGICAL | ||||

| SBP | 130.0 (120-142) | 130.0 (120-140) | 0.01 | 0.30 |

| DBP | 80 (80-90) | 80 (80-92) | 0.00 | 0.80 |

| WHR | 1.0 (0.9-1.0) | 0.9 (0.9-1.0) | 0.01 | 0.27 |

| BMI kg/m2 | 29.4 (25-34) | 27 (24-30) | 0.05 | < 0.05* |

| Total Cholesterol mg/dL | 185 (165-215) | 166 (140-200) | 0.07 | < 0.05* |

| HDL mg/dL | 55 (50-68) | 54 (41-65) | 0.02 | 0.23 |

| LDL mg/dL | 103 (81-123) | 83.8 (72-104) | 0.08 | < 0.05* |

| Triglycerides mg/dL | 120 (85-159) | 115 (80-183) | 0.00 | 0.90 |

| Blood glucose mg/dL | 70 (68-85) | 72 (70-84) | 0.01 | 0.40 |

| Age | 55.0 (49-62) | 40.0 (32-48) | 0.29+ | < 0.001*** |

| Descriptors | Group 1 n=39 |

Group 2 n=47 |

Effect size |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEHAVIORAL | ||||

| Smoker | ||||

| No | 89.7% | 95.7% | Φ = 0.12+ | 0.40 |

| Yes | 10.3% | 4.3% | ||

| Ex-smoker | ||||

| No | 64.1% | 85.1% | V = 0.24++ | 0.09 |

| Yes | 25.6% | 10.6% | ||

| No reply | 10.3% | 4.3% | ||

| Alcohol consumption | ||||

| No | 79.5% | 57.4% | Φ = 0.23+ | < 0.05* |

| Yes | 20.5% | 42.6% | ||

| Healthy eating | ||||

| No | 38.5% | 29.8% | Φ = 0.09 | 0.40 |

| Yes | 61.5% | 70.2% | ||

| BIOLOGICAL | ||||

| SAH | ||||

| No | 74.4% | 83.3% | Φ = 0.10+ | 0.33 |

| Yes | 25.6% | 17.0% | ||

| Diabetes | ||||

| No | 94.9% | 95.7% | Φ = 0.02 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 5.1% | 4.3% | ||

| Stroke | ||||

| No | 100% | 97.9% | Φ = 0.10+ | 1.00 |

| Yes | 0.0% | 2.1% | ||

| CVD | ||||

| No | 84.6% | 85.1% | V = 0.10+ | 0.87 |

| Don’t know | 15.4% | 12.8% | ||

| Other | 0.0% | 2.1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).