Submitted:

13 August 2024

Posted:

14 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

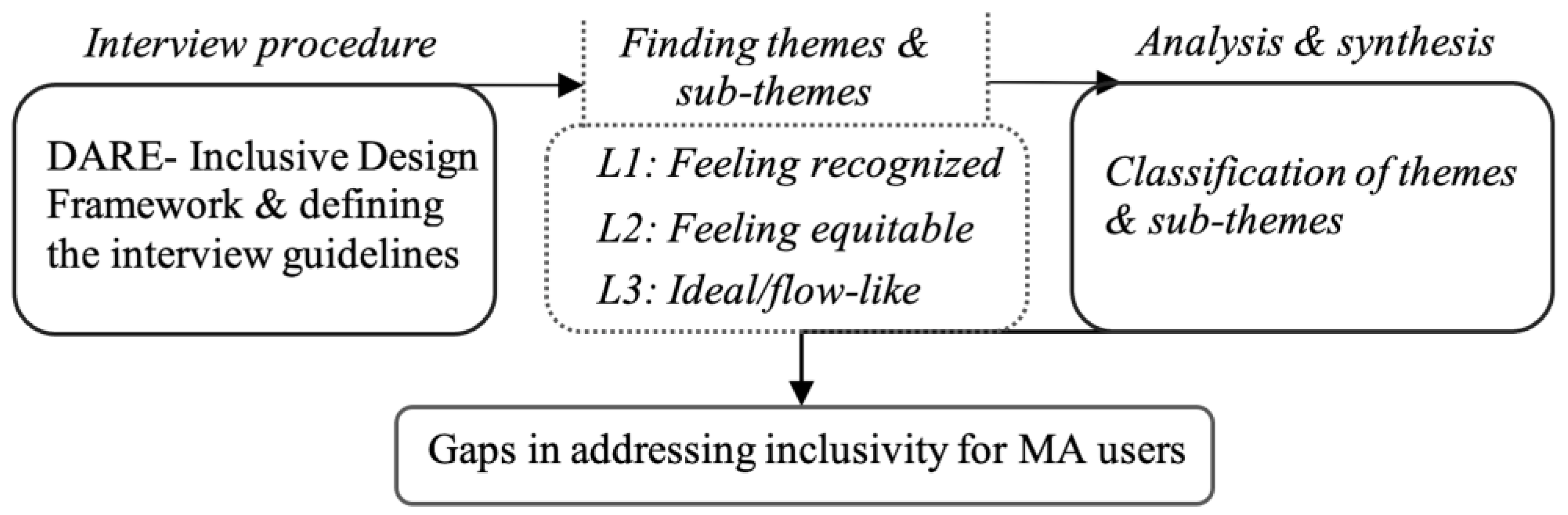

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Establishment of the Study Procedure

2.2. DARE-Inclusive Design Framework

- Level 1 (L1) focuses on accessibility and is linked to industry regulations. L1 follows market-driven reform policies and neoliberalism principles, which suggest that market forces can self-regulate. Designs under L1 aim to meet minimum standards to remove barriers.

- Level 2 (L2) emphasizes increased engagement and positive emotions, promoting equitable access and fair relationships guided by social justice principles. Rooted in social justice, L2 seeks to validate users' experiences through empathy and understanding of how products impact their everyday lives.

- At Level 3 (L3), a minimal mismatch between users and design is ideal. L3 focuses on empowered success through positive design, emphasizing human flourishing and the complete inclusion of all individuals [40]. Users experience a state of flow, enjoying profound immersion in tasks with harmonious interaction between themselves and the environment, enabling fluid and creative interaction with their physical and social environment [20].

2.3. Development of Interview Guidelines and Questions

2.4. Recruitment and Study Population

2.5. Data Collection

- Broad questions (e.g., experiences, definition of disability, etc.).

- What is your thought on the adjustment of environments and MAs for clients’ needs? And how might they be improved?

- How do clients perceive their bodies and disability? How do they compare their body before and after disability challenge?

- How do clients see their MAs and environment? Are there any mismatches between their expectations and the existing situation?

- How can the technology influence the client's decision to accept or refuse a prescribed MA?

- How do clients feel about social activities and participation? How do culture and social context affect their perceptions?

- How do clients deal with potential social challenges? And what they do to improve their social participation?

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Ethics

3. Results

- 1.

- Perceived Financial Value: Assessing Worth

- 8.

- Objective Enhancements: Optimizing Environments and MAs (Technological and ergonomics optimization in MAs; Enhancement of accessibility in private and public settings).

- 9.

- Subjective Enhancements: Trustworthiness, Support, and Hope (Fear and shyness in the usage of MAs in public settings; Desire for empathy from family and physiotherapists).

- 10.

- Contextual Factors: Interpretations and Representations (Causes of disability and inclusivity perceptions; Lack of aesthetic polish in MA design)

3.1. Theme 1: Perceived Financial Value: Assessing Worth

3.2. Theme 2: Objective Enhancements: Optimizing Environments and Mas

3.3. Theme 3: Subjective Enhancements: Trustworthiness, Support, and Hope

3.4. Theme 4: Contextual Factors: Interpretations and Representations

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Studies

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Desai, R.H.; Hollingsworth, H.; Stark, S.; Putnam, M.; Eyler, A.; Wehmeier, A.; Morgan, K. Social Participation of Adults Aging with Long-Term Physical Disabilities: A Cross-Sectional Study Investigating the Role of Transportation Mode and Urban vs Rural Living. Disability and Health Journal 2023, 16, 101503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, F.; Yang, H.-Y.; Sanford, J. Physical Environmental Barriers to Community Mobility in Older and Younger Wheelchair Users. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhao, P.; Qin, K.; Kwan, M.-P.; Wang, N. Towards Healthcare Access Equality: Understanding Spatial Accessibility to Healthcare Services for Wheelchair Users. Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 2024, 108, 102069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, C.A.; Rawat, V.; Sullivan, J.; Tay, R.; Naweed, A.; Gudimetla, P. “I’m Very Visible but Seldom Seen”: Consumer Choice and Use of Mobility Aids on Public Transport. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 2017, 14, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, D.J.; Reid, D.; Cott, C. The Experience of Senior Stroke Survivors: Factors in Community Participation among Wheelchair Users. Can J Occup Ther 2006, 73, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Saray, P.; Peláez-Ballestas, I.; Ramos-Lira, L.; Sánchez-Monroy, D.; Burgos-Vargas, R. Usage Problems and Social Barriers Faced by Persons with a Wheelchair and Other Aids. Qualitative Study from the Ergonomics Perspective in Persons Disabled by Rheumatoid Arthritis and Other Conditions. Reumatol Clin 2013, 9, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Park, G.-R.; Namkung, E.H. The Link between Disability and Social Participation Revisited: Heterogeneity by Type of Social Participation and by Socioeconomic Status. Disability and Health Journal 2024, 17, 101543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oishi, M.M.K.; Mitchell, I.M.; Loos, H.F.M.V. der Design and Use of Assistive Technology: Social, Technical, Ethical, and Economic Challenges; Springer New York, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4419-7030-5.

- Barlew, L.; Secrest, J.; Guo, Z.; Fell, N.; Haban, G. The Experience of Being Grounded: A Phenomenological Study of Living with a Wheelchair. Rehabilitation Nursing Journal 2013, 38, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, V. de S.P.; Melo, M.R.A.C.; Garanhani, M.L.; Fujisawa, D.S. Social Representations of the Wheelchair for People with Spinal Cord Injury. Rev. Latino-Am. Enfermagem 2010, 18, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edberg, A.-K.; Persson, D. The Experience of Active Wheelchair Provision and Aspects of Importance Concerning the Wheelchair Among Experienced Users in Sweden. 2011.

- Barker, D.J.; Reid, D.; Cott, C. Acceptance and Meanings of Wheelchair Use in Senior Stroke Survivors. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 2004, 58, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emerson, E.; Fortune, N.; Llewellyn, G.; Stancliffe, R. Loneliness, Social Support, Social Isolation and Wellbeing among Working Age Adults with and without Disability: Cross-Sectional Study. Disabil Health J 2021, 14, 100965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lidwell, W.; Holden, K.; Butler, J. Universal Principles of Design: 125 Ways to Enhance Usability, Influence Perception, Increase Appeal, Make Better Design Decisions, and Teach through Design; [25 Additional Design Principles]; rev. and updated.; Rockport Publ: Beverly, Mass, 2010; ISBN 978-1-59253-587-3.

- Rousseau-Harrison, K.; Rochette, A.; Routhier, F.; Dessureault, D.; Thibault, F.; Cote, O. Perceived Impacts of a First Wheelchair on Social Participation. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 2012, 7, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newell, A. Inclusive Design or Assistive Technology. In Inclusive Design: Design for the Whole Population; Clarkson, J., Keates, S., Coleman, R., Lebbon, C., Eds.; Springer: London, 2003; pp. 172–181 ISBN 978-1-4471-0001-0.

- Yaldiz, N.; Agarwal, H.; Chakrabarti, A. Assessment of Inclusivity in a Product Life Cycle. In Proceedings of the Design in the Era of Industry 4.0, Volume 2; Chakrabarti, A., Singh, V., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 747–760.

- Product Experience; Schifferstein, H.N.J., Hekkert, P., Eds.; 1st edition.; Elsevier Science: San Diego, CA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-08-045089-6.

- Heylighen, A.; Van der Linden, V.; Van Steenwinkel, I. Ten Questions Concerning Inclusive Design of the Built Environment. Building and Environment 2017, 114, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, V.M.; Hollenbeck, C.R. Designing for All: Consumer Response to Inclusive Design. Journal of Consumer Psychology 2021, 31, 360–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbareschi, G.; Carew, M.T.; Johnson, E.A.; Kopi, N.; Holloway, C. “When They See a Wheelchair, They’ve Not Even Seen Me”—Factors Shaping the Experience of Disability Stigma and Discrimination in Kenya. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grue, J. The Social Meaning of Disability: A Reflection on Categorisation, Stigma and Identity. Sociology of Health & Illness 2016, 38, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Right Watch “I Am Equally Human”. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/06/27/i-am-equally-human/discrimination-and-lack-accessibility-people-disabilities-iran (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- Sahoo, S.K.; Choudhury, B.B. Wheelchair Accessibility: Bridging the Gap to Equality and Inclusion. Decision Making Advances 2023, 1, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perangin-Angin, R.; Tavakoli, R.; Kusumo, C. Inclusive Tourism: The Experiences and Expectations of Indonesian Wheelchair Tourists in Nature Tourism. Tourism Recreation Research 2023, 48, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Physiopedia Assistive Devices. Available online: https://www.physio-pedia.com/Assistive_Devices (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- UNICEF, WHO. Assistive Technology for Children with Disabilities: Creating Opportunities for Education, Inclusion and Participation 2015 2018.

- Hossen Sajib, S. Identifying Barriers to the Public Transport Accessibility for Disabled People in Dhaka: A Qualitative Analysis. Transactions on Transport Sciences 2022, 13, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widehammar, C.; Lidström, H.; Hermansson, L. Environmental Barriers to Participation and Facilitators for Use of Three Types of Assistive Technology Devices. Assistive Technology 2019, 31, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiri, A. Inclusivity and Diversity of Navigation Services. The Journal of Navigation 2021, 74, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiri, A. Open Area Path Finding to Improve Wheelchair Navigation 2020.

- Bodaghi, N.B.; Zainab, A.N. Accessibility and Facilities for the Disabled in Public and University Library Buildings in Iran. Information Development 2013, 29, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vice, J.; Barstow, B.A.; Bowman, S.; Mehta, T.; Padalabalanarayanan, S. Effectiveness of the International Symbol of Access and Inclusivity of Other Disability Groups. Disability and Health Journal 2020, 13, 100836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, K.; Maeda, J. Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design; Reprint Edition.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts ; London, England, 2020; ISBN 978-0-262-53948-7.

- Turk, M.A.; Mitra, M. The Evolution of Disability and Health Research and Practice. Disability and Health Journal 2023, 16, 101450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracy, S.J. Qualitative Research Methods: Collecting Evidence, Crafting Analysis, Communicating Impact; John Wiley & Sons, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4051-9202-6.

- Nussbaumer, L.L. Inclusive Design: A Universal Need; 1st edition.; Fairchild Books: New York : London, 2011; ISBN 978-1-56367-921-6. [Google Scholar]

- Jamshed, S. Qualitative Research Method-Interviewing and Observation. J Basic Clin Pharm 2014, 5, 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longhurst, R. Interviews: In-Depth, Semi-Structured. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Kitchin, R., Thrift, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, 2009; pp. 580–584. ISBN 978-0-08-044910-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pohlmeyer, A.E. How Design Can (Not) Support Human Flourishing. In Positive Psychology Interventions in Practice; Proctor, C., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 235–255. ISBN 978-3-319-51787-2. [Google Scholar]

- Chartered Society Of Physiotherapy Disabled, Not Defeated. Available online: https://www.csp.org.uk/frontline/article/disabled-not-defeated (accessed on 9 February 2024).

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis. In APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol 2: Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological; APA handbooks in psychology®; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, US, 2012; pp. 57–71. ISBN 978-1-4338-1005-3. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Conceptual and Design Thinking for Thematic Analysis. Qualitative Psychology 2022, 9, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UChicago Library The Holy Defense - The Graphics of Revolution and War - The University of Chicago Library. Available online: https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/collex/exhibits/graphics-revolution-and-war-iranian-poster-arts/holy-defense/ (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Colizzi, M.; Lasalvia, A.; Ruggeri, M. Prevention and Early Intervention in Youth Mental Health: Is It Time for a Multidisciplinary and Trans-Diagnostic Model for Care? International Journal of Mental Health Systems 2020, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasoulivalajoozi, M.; Touir, G. Spinal Fusion Surgery for High-Risk Patients: A Review of Hospitals Information. Social Determinants of Health 2023, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, I.; Robertson, I.K.; Neil, A.; Reeve, J.; Palmer, A.J.; Skinner, E.H.; Browning, L.; Anderson, L.; Hill, C.; Story, D.; et al. Preoperative Physiotherapy Is Cost-Effective for Preventing Pulmonary Complications after Major Abdominal Surgery: A Health Economic Analysis of a Multicentre Randomised Trial. Journal of Physiotherapy 2020, 66, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EtemadOnline The price of a wheelchair has increased at least 3 times / 56% of disabled people in Tehran receive a pension. Available online: https://shorturl.at/coCXY (accessed on 5 May 2024).

- WHO-Asssitive Assistive Technology. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/assistive-technology (accessed on 4 January 2022).

- White, K. An Introduction to the Sociology of Health and Illness; SAGE Publications: London ; Thousand Oaks, Calif, 2002; ISBN 978-0-7619-6399-8.

- Matin, P. Introductionn of Medical Annthropology; 1st ed.; Farhameh: Tehran, 2021; ISBN 978-600-94057-1-8.

- Skempes, D.; Kiekens, C.; Malmivaara, A.; Michail, X.; Bickenbach, J.; Stucki, G. Supporting Government Policies to Embed and Expand Rehabilitation in Health Systems in Europe: A Framework for Action. Health Policy 2022, 126, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapsalis, E.; Jaeger, N.; Hale, J. Disabled-by-Design: Effects of Inaccessible Urban Public Spaces on Users of Mobility Assistive Devices – a Systematic Review. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 2022, 0, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohebbi, V.; Dianat, I.; Castellucci, H.I. Psychometric Properties of the Iranian Version of the Wheelchair Seating Discomfort Assessment Tool (WcS-DAT) – Section II: A Revised Two-Dimensional Structure of Comfort and Discomfort to Improve Inclusive Design Practice. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 2023, 19, 1351–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, I.; Pinheiro, J.; Silveira, J.; Francisco, P.; Jutai, J.; Correia Martins, A. Psychosocial Impact of Powered Wheelchair, Users’ Satisfaction and Their Relation to Social Participation. Technologies 2019, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soetemans, J.K.; Jackson, L.M. The Influence of Accessibility on Perceptions of People with Disabilities. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies 2021, 10, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghzadeh, C. Disabled Push for a Better Life in Iran. BBC News 2015.

- EIDD European Institute for Design and Disability in Stockholm, EIDD Stockholm Declaration Of. Available online: https://dfaeurope.eu/what-is-dfa/dfa-documents/the-eidd-stockholm-declaration-2004/ (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- BCA Code on Accessibility in the Built Environment 2019.

- Andrade, C.C.; Devlin, A.S. Stress Reduction in the Hospital Room: Applying Ulrich’s Theory of Supportive Design. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2015, 41, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, A. Q & A: Reality Check. The Engineer 2020, 300, 30–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goold, S.D. Trust, Distrust and Trustworthiness. J Gen Intern Med 2002, 17, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cucuzzella, C.; Rasoulivalajoozi, M.; Farzamfar, G. Spatial Experience of Cancer Inpatients in the Oncology Wards: A Qualitative Study in Visual Design Aspects. European Journal of Oncology Nursing 2024, 102552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglass, T.; Calnan, M. Trust Matters for Doctors? Towards an Agenda for Research. Soc Theory Health 2016, 14, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Duarte, F.; Brown, P.; Mendes, A.M. Healthcare Professionals’ Trust in Patients: A Review of the Empirical and Theoretical Literatures. Sociology Compass 2020, 14, e12828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokdad, M.; Mebarki, B.; Bouabdellah, L.; Mokdad, I. Emotional Responses of the Disabled Towards Wheelchairs. In Proceedings of the Advances in Affective and Pleasurable Design; Chung, W., Shin, C.S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Jutai, J.; Day, H. Psychosocial Impact of Assistive Devices Scale (PIADS). Technology and Disability 2002, 14, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, K.; Wobbrock, J.O. Self-Conscious or Self-Confident? A Diary Study Conceptualizing the Social Accessibility of Assistive Technology. ACM Trans. Access. Comput. 2016, 8, 5:1–5:31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R.J.; Cooper, R.; Tether, B.; Murphy, E. Design, the Language of Innovation: A Review of the Design Studies Literature. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 2018, 4, 249–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, D.A. Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things; Basic Books, 2004; ISBN 978-0-465-05135-9.

- Shi, A.; Huo, F.; Hou, G. Effects of Design Aesthetics on the Perceived Value of a Product. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Interaction Design Foundation What Is Aesthetics? Available online: https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/aesthetics (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- dos Santos, A.D.P.; Ferrari, A.L.M.; Medola, F.O.; Sandnes, F.E. Aesthetics and the Perceived Stigma of Assistive Technology for Visual Impairment. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 2022, 17, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | The Iran-Iraq

War was referred to as the "Imposed War" and the "Holy

Defense" in Iran due to its perception as a defensive struggle against

aggression [46]. |

| Years of experiences | Interview time (Min) | Working experiences and profession category |

|---|---|---|

| *S=234, **A=18.14 (min-max:8-25) | S=840, A=70 (min-max:50-90) | Private clinic (N=4), health care centre (N=2), home visiting (N=1), state welfare organization (N=2) hospital (N=3), national medical committee of the Olympics (N=2). |

| Quote (Q) # | Perceived Financial Value: Assessing Worth. |

|---|---|

| Q1 | Most assistive devices are affordable…However, if an orthosis were to be individually prepared by an orthotist during rehabilitation, it will certainly be more expensive for clients than mass-produced ones. |

| Q2 | …The economic factor is important in prescribing a solution [suggesting an MA].... It should not impose a financial burden on the individual…. A suitable price of MAs greatly influences the decision to accept or reject the product. |

| Q3 | The complaint was that the price we paid did not correspond to the period of use... I [user] paid a fee, but after a month of use, it is not washable, nor are the parts replaceable. This is a common complaint. |

| Q4 | …It is not fair for clients to endure fatigue or face potential tragedies just for not affording an orthosis…. Eventually, they have no choice but to accept the basic and inexpensive models of MAs. |

| Q5 | In developing societies where there is economic fluctuation, the clients often say: You've never been in my shoes to understand the financial strain it puts on me…. |

| Q6 | …It is difficult to pay for something that you didn't need to pay for before [mobility]. They [clients] often compare their current situation to their past. |

| Q7 | Producers' recommendations for user-friendliness are often related to their profit motives rather than focusing on research on users, development, and improving clients' health…. |

| Q8 | In a society like Afghanistan [A neighbouring country of Iran], or impoverished cities within Iran, despite a weak economy and poverty, people sometimes address their needs with minimal resources, such as wooden handmade canes, which are locally crafted. |

| Quote (Q) # | Objective Enhancements: Optimizing Environments and MAs |

|---|---|

| Q13 | The whole city can be a ground for constant complaints from disabled individuals…. Despite employing fanciest architectural style, like the fancy stairs, the slope is so steep that the wheelchair may overturn. |

| Q14 | …Being mindful of the environment for people with disabilities shows respect for their needs.... When users [MA users] see this effort, it boosts their self-confidence. But in places where nothing is set up for disabilities, everything seems to treat them (MA users) like a burden, leading to feelings of shame and helplessness that are seen on their faces. |

| Q15 | Their [clients] reaction is anger and finally yield and ask for help…. Our [physiotherapists] approach is moderating dissatisfaction or justifying shortcomings. |

| Q16 | In terms of anthropometry, there is limited variation in the sizing of these products [MAs] within our country [Iran]. Sizes are typically limited to small, medium, and large…. |

| Q17 | Ergonomics and environmental adaptation are important…. However, equipment from other countries may not always be suitable for the new environment [Iran]. |

| Q18 | It is very important to use a material that reduces the weight of the MAs. |

| Q19 | One of the factors is the lightness of the material…. The material used must be lightweight yet strong enough to carry the muscles and skeleton of the body. |

| Q20 | We need to have some devices [MAs] that show a sense of trust and functionality for a long time. …The feeling of relying on such device gives [to MA users] a peace of mind. |

| Q21 |

Sometimes the users complain about the long-time seating and lack of suitable structure of conventional wheelchairs with a sturdy material.…To reduce pressure, they add sponge foam padding. They complain so much that some refuse to use the product. They insist, asking if there's another way [for recovery]. |

| Q22 | Technology can have a significant impact, ranging from 20% to 40%. Especially for those who resist using MA [wheelchair]. |

| Q23 | The beauty of assistive products can influence MA users’ preference by 30-40%, which is significant for us [physiotherapists]. This is especially true for children and young people, where appearance matters a lot. |

| Q24 | Embellishments can motivate them to accept continued use over time. It may also affect their social interpretation…In my opinion, the best colors are vibrant and warm colors. There should be color variations and users' subconscious should like the color. The design of the work and clinic space should motivate people and do not remind them of their troubles. …We have to bring something into the clients' eyes that has a good effect on the patient's emotions. …The sense of touch is very important, for example, the roughness of the seat, and the coldness of the material should be taken into considerations. |

| Quote (Q) # | Subjective Aspects: Trustworthiness, Support, and Hope |

|---|---|

| Q25 | Sometimes they are unsure if relying on these devices will provide adequate support for movement. For example, they ask, "Is this device robust enough to carry me? |

| Q26 | …It [lack of trust to MAs] is rooted in their self-confidence. ...Timid individuals often try to hunch over and walk slowly and take great care. It is rooted in fear and anxiety. …Mental and psychological factors are very effective [in perception of the disability]. |

| Q27 | In an unsuitable environment, MAs can be perceived as an insult [for users], leading to feelings of shame and helplessness, like the sense of fear and shame after falling downstairs |

| Q28 | Once they are disappointed, they state it [MAs] is useless and consider it as a burden. That is why they may consider the MAs as an excessive gadget…. |

| Q29 | They are very open and receptive to the treatment process and respond: I will use whatever assistive device [MAs] you [physiotherapist] recommend. ...They continuously check their progressof rehabilitation. ...A trusting relationship with their doctor enhances clients' levels of hope. Sometimes clients trust their physiotherapists even more than their religious assumptions. |

| Q30 | Sometimes clients get nervous and depressed…they are upset with their own families and do not like to get help from them. They say: don't bother me. If the depression is severe and persistent, the patient may even contemplate suicide…. Without hope, they gradually face challenges and may engage in risky behaviors. |

| Q31 | Sometimes clients feel they have become a burden on their family. …For example, I have a client who feels embarrassed and ashamed when his wife and family bring him to physiotherapy. |

| Q32 | Regarding social participation, they feel shy and don't want to use assistive devices in public. |

| Q33 | Depression is a significant social challenge for them [clients]... If they believe they won't recover or regain a normal life, it leads to feelings of despair. ...When clients seem to have lost hope, they may refuse to cooperate with their physiotherapist. |

| Quote (Q) # | Contextual Factors: Interpretations and Representations |

|---|---|

| Q34 | They sigh. They believe that this [mobility disability] is a form of retribution and punishment for their past actions…. |

| Q35 | …Social, accessibility, and work environment issues, along with cultural differences, appearance [MAs] and clothing styles can affect the fit and perception of MAs, potentially exacerbating the patient's [clients] condition and reproducing the meaning of "I am a patient."… This interpretation [being dis/abled] may differ between rural areas, where disability is more associated with negative stereotypes, and the larger urban society. |

| Q36 |

Being socially perceived as a hero is different from being a fugitive or accused. Being [socially] accepted as someone whose fingers were cut off [according to religious law] for theft and someone whose finger is injured like Hans Brinker [Refers to Mary Mapes Dodge's novel about a boy who saves Amsterdam by plugging a dike leak with his finger] is very different. ...For instance, someone disabled due to an unsafe car or road often blames society and views themselves as a victim. …Owning a crutch or wheelchair from wartime, even if it's no longer necessary, serves as a heroic symbol for the individual–embodying qualities of courage, selflessness, and determination…. |

| Q37 | Products [MAs] should be designed to confer prestige rather than limitations…. |

| Q38 | …They [Clients] believe they're alone in their illness, unaware that others require assistance too…However, we can encourage them to persevere by offering support and empathy. |

| Q39 | [User] are most reluctant to use these devices due to societal negative attitudes and pity…. |

| Q40 | …The decline in individual independence, especially in social and financial areas, significantly affects clients' likelihood to use MAs. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).