Introduction

Infectious pathogens are persistent threats, causing the emergence or recurrence of fatal infections in different parts of the world. For instance, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic originated in China and has been associated with 6,817,478 deaths worldwide as of 4th February 2023 (WHO, 2020). During disease outbreaks, various public health preventive measures, including nose mask use and hand hygiene, were implementedto prevent or delay disease occurrence and reduce further transmission/exposure (Kisling & Das, 2022). Nose mask usage has been described as an effective protocol (Brooks & Butler, 2021; CDC, 2020), particularly in protecting the user's mouth and nose from splashes, droplets, and sprays that may include pathobionts (Amin, 2022).

However, reusing and prolonged use of a single mask has become common in many parts of the world(Chughtai et al., 2019), especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, which could result in mask contamination. Since COVID-19 spreads via droplets, the continuous and frequent use of a single mask may lead to the accumulation of respiratory pathogens and be a source of infection to the wearer. For instance, respiratory microbes, including Streptococcus, Pseudomonas and Aspergillus spp., were isolated from used nose masks by healthcare personnel (Gund et al., 2021). Also, metagenomic analysis of nose masks (healthy and chronic pulmonary diseased individuals) showed antimicrobial resistance genes (mefA, tetM and ermB) (Kennedy et al., 2018), indicating that respiratory droplets associated with nose mask usagecould facilitate the spread of AMR genes.

Nose mask usage is attributed to moisture retention due to an increase in temperature and could serve as a breeding ground to support the growth of respiratory microbes (Chughtai et al., 2019; Monalisa et al., 2017; Roberge et al., 2010). Prolonged mask use among healthcare workers has been linked to increased microbial load, resulting in skin microbiome dysbiosis and the selection of virulent and pathogenic microbes (Teo, 2021; Zhiqing et al., 2018). This presents a threat to public health, particularly while COVID-19 lingers. This might facilitate exposure to secondary infections, especially in immunocompromised individuals. Previous studies on the presence of respiratory microbes on nose masks have been well- studied in healthcare settings (Delanghe et al., 2021; Zhiqing et al., 2018). However, there is a paucity of data in the community settings; as a result, this study aimed to profile Streptococcus species from used masks during the COVID-19 era.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Sample Collection

This was a cross-sectional exploratory study aimed at identifying Streptococcus isolates from used nose masks. The study was conducted on 100 nose masks collected from students at the Department of Biochemistry, Cell and Molecular Biology (BCMB), University of Ghana. Participants consented to participate in this study. The nose masks were collected aseptically in a sterile Falcon tube and transported to the Molecular Biology Lab at BCMB for analysis. The Streptococcus pneumoniae strains, NCSP 0129 and NCSP 0130, with established antimicrobial profiles from AbiMosi Bacterial Culture Library, BCMB, University of Ghana, were used as controls.

Isolation and Presumptive Identification of Streptococcus

The nose masks were aseptically enriched in 25 ml LB broth and incubated (37 ºC for 24 h) with shaking at 225 rpm to dislodge the resident microbes. 10 µl of serially diluted broth culture were inoculated by spreading on 5% sheep Blood agar plates and incubated at 37 ºC for 18-24 h in 5% CO2 (Kebede et al., 2021). Probable Streptococcus isolates, based on the hemolytic properties, were Gram stained and subjected to a catalase and capsulation test. Briefly, A smear of bacterial culture was prepared on clean glass slides and allowed to dry. The smear was covered with Crystal violet (1%) for 2 min and washed with copper sulphate solution (20%). The slide was air-dried and examined microscopically at X100 (oil immersion) magnification to detect the presence or absence of capsules.

Streptococcus Genotyping and 16S rRNA gene Amplification

The DNA of presumptive streptococcal isolates were extracted using Quick-DNA Fungal/Bacterial Kits (Zymo Research). PCR was performed with a 2720 Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, USA, California) in a final volume of 25 µl; 12.5 µl of OneTaq 2X master, reverse and forward primers (0.5 µl each), nuclease-free water (9.5 µl) and template DNA (2 µl). The 16S rRNA and sodA gene were amplified using the same primer sets and conditions previously described (Chen et al., 2018; Marín et al., 2017). Also, resistance (tet(B), erm(B)) and virulence markers (pbp2b, pbp2b1, lytA, lytA1, ply1, cbpA, pavA) of the isolated Streptococcus species were determined using primer and PCR conditions. Amplified products were resolved on 1.5 % agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide and run at 100 V for 45 min AND visualized with Gel Doc™ imager (Amersham Imager 600, Tokyo, Japan). The 16S rRNA PCR amplicons were purified using a QIAquick kit, Sanger Sequenced (Eurofins Genomics, India), and sequenced data queried with NCBI BLASTed.

Antimicrobial Resistance Profiling

Streptococcus isolates were tested against 16 antibiotics listed in Ghana's National guideline for the standard treatment of bacterial infections (Darkwah et al., 2021). They include ceftriaxone (30 µg), doxycycline (30 µg), Azithromycin (15 µg), ciprofloxacin (5 µg), cefuroxime (30 µg), levofloxacin (5 µg), amoxiclav (10 µg), gentamicin (10 µg), trimethoprim (23.75 µg), tetracycline (30 µg), penicillin (10 µg), ampicillin (10 µg), cloxacillin (10 µg), amoxicillin (10 µg), erythromycin (15 µg), meropenem (10 µg). The AMR profiles were determined with Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion previously described (Christenson et al., 2018). Briefly, Mueller Hinton agar plates were seeded with MacFarland standardized culture of the strains, antibiotic discs were applied and incubated (37 ºC, 19–24 h). The zone of inhibition was measured (mm), and data was interpreted as resistant or susceptible using CLSI guidelines (CLSI, 2020; EUCAST, 2022). Also, the susceptibility of the Streptococcal isolates to three commonly used disinfectants/antiseptics: Dettol® (Reckitt Benckiser, Nigeria), So-Klin® (PT. Sayap Mas Utama, Indonesia) and bleach (Power Zone-Thick Perfumed Bleach, Tema-Accra), was determined as previously described (Wu et al., 2015). The disinfectant was diluted following the manufacturer's suggested (stock) concentration. 0.1 v/v, 0.01 v/v, and 0.001 v/v concentrations were prepared using sterile double distilled water. A 100 ul of each disinfectant and the isolates were incubated (37 ºC, 19–24 h) in a sterile 96-well microtiter plate alongside controls (White et al., 2021). Absorbance was measured with a microplate reader (Varioskan LUX) at 600 nm, and AMR profiles determined as previously indicated (CLSI, 2020; EUCAST, 2022).

Antibiotic Stress Assay and Gene Expression Analysis of Virulence Markers

Streptococcal isolates resistant to doxycycline (30 µg) and azithromycin (15 µg) were cultured in MHbroth at 3X azithromycin and doxycycline standard concentrations and incubated (72 h at 37 ºC, 225 rpm).Total RNA from the stressed and normal cells was extracted with ZymoResearch Quick-RNA Miniprep Kit as outlined by the manufacturer. RT-qPCR was used to determine the levels of virulence-associated with pbp2b, lytA, cbpA, and pavA in isolates with (exposure to azithromycin and doxycycline) and without stress.

The target genes are involved in the pathogenesis of pneumococcal infections and antibiotic resistance (Zhou et al., 2022). Reactions were performed with Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR System (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) using One-Step RT-qPCR Kit (Luna® Universal, New England Biolabs). Each RT-qPCR reaction was performed in a final volume of 20 µl; forward and reverse primers (0.8 µl), Luna Universal One-Step Reaction Mix (2X) (10 µl), 1 µl Luna WarmStart® RT Enzyme Mix (20X), 5.4 µl of nuclease-free water and 2 µl of template RNA (100 ng/µl). The cycling conditions include reverse transcription at 55 ºC for 10 min, an initial denaturation at 95 ºC for 1 min, followed by 40 cycles of 10 s denaturation at 95 ºC, and 1 min of extension at 60 ºC. The reaction was performed in a 96-well microplate, with housekeeping gene 16S rRNA as the endogenous control. The target gene's mRNA transcript levels were assessed as previously described (Hu et al., 2013). The Ct values of the endogenous control and target genes were normalized with the formula 2-ΔΔCT where ΔΔCT = ΔCT (a target sample) – ΔCT (a control sample) (Livak & Schmittgen, 2001; Rao et al., 2013). The resulting values were calculated as fold change and expressed as log2 fold change with mean ± SD.

Statistical Analysis

The Data from the study were assembled into MS Excel 2021 LTSC (version 2206), and data analysis was performed with SPSS 16.0 and GraphPad 6.0 software. AMR profiles were determined by descriptive statistics and presented as graphs.

Results

Phenotypic and Molecular Identification of Streptococcus Isolates

Twenty-three percent (23%) of the 100 samples analyzed had

Streptococcus isolates, 12% from the exterior and 11% from the interior. The isolates were presumptively identified with hemolytic activities on blood media, were capsulated, catalase-negative and paired cocci (

Table 1). All the isolates were positive for the

superoxide dismutase gene (sodA), and as confirmed by 16S rRNA gene-based Sanger sequencing, twenty were

S. pneumoniae and three

S. pyogenes. Two of the three

S. pyogenes were isolated from the exterior of the masks

. Streptococcus pneumoniae and

S. pyogenes are of clinical relevance and have been implicated in severe human infections.

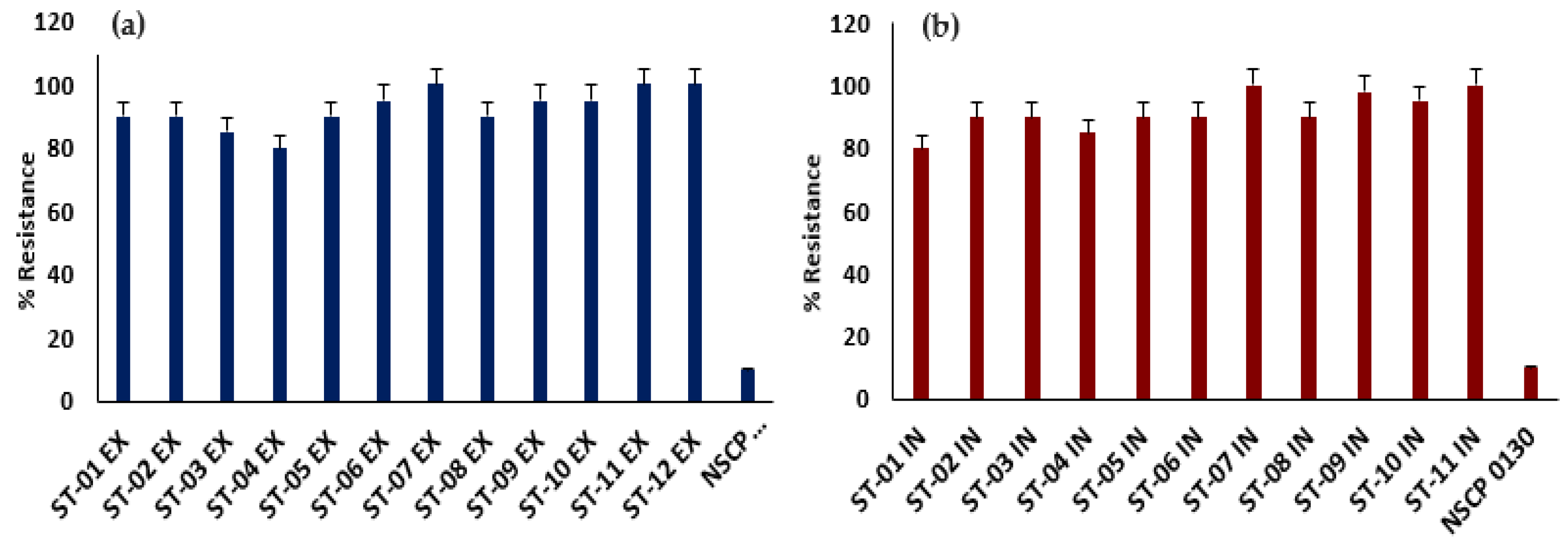

Highly and Multidrug Resistant Streptococcus spp. Are Resident on Nose Masks

All the streptococcal isolates were tested against 16 antibiotics of 8 classes. The

Streptococcus isolates showed high levels of AMR to all the antibiotics relative to the

S. pneumoniae controls. 90% of the isolates were resistant to all the antibiotics tested (

Table 1) and are MDR with 80-100% levels of AMR (

Figure 1). The MAR index of the

Streptococcus isolates, defined as the ratio of antibiotics tested to those resisted, ranged from 0.80 to 1.00, with an average of 0.93 (

Table 1). The

S. pyogenes from the exterior was 100%resistant to all the antibiotics, including meropenem. All the tested strains had MAR index greater than 0.2,

indicating they are potential pathogenic bacteria.

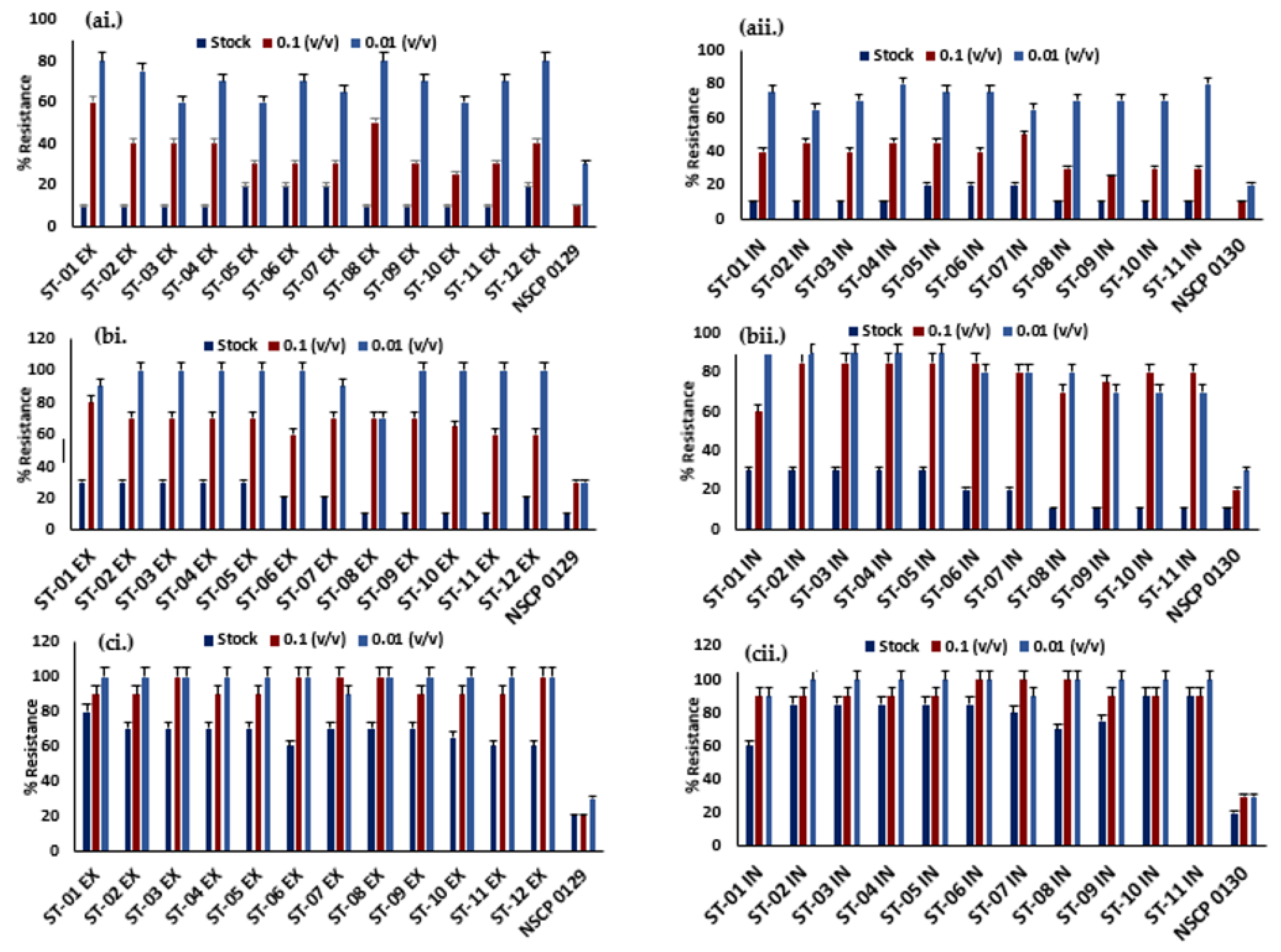

Ineffective Disinfectants Against Streptococcus spp.

All the isolates displayed 30-80% levels of resistance to Dettol® at 0.1 and 0.01 (v/v), with 10% at the stock concentration relative to the controls (

Figure 2a). So Klin® has similar low percentage resistance (10%) to ST-08, ST-09, ST-10 and ST-11 strains from the exterior and interior. All the other strains showed 20-90% levels of resistance to So Klin® at all concentrations (

Figure 2b). The isolates survived in the presence of Bleach® as compared to other tested disinfectants with 60-100% relatively high levels of resistance at all concentrations (

Figure 2c). Overall, the disinfectants showed no effective activity against the

Streptococcus isolates relative to the controls, which increases the public health risks associated with rewash of nose masks to use.

Detection of Markers Associated with Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance

Primer-specific amplification of resistance markers associated with doxycycline (

tetB) and azithromycin (

ermB) was performed and 20 (90%) isolates were positive for the

tetB and 8 (35%) for the

ermB gene (

Table 2). Also, only eight isolates simultaneously tested positive for the

tetB and

ermB genes (

Table 2). These virulence markers

pbp2b1, lytA, lytA1, and

ply1 genes were detected in all 23 (100%) isolates. The

pbp2b and

cbpA genes were detected in 19 (80%) isolates, while 6 (26%) were positive for

pavA genes

. At least five virulence genes were present in all isolates, indicating their potential to cause disease.

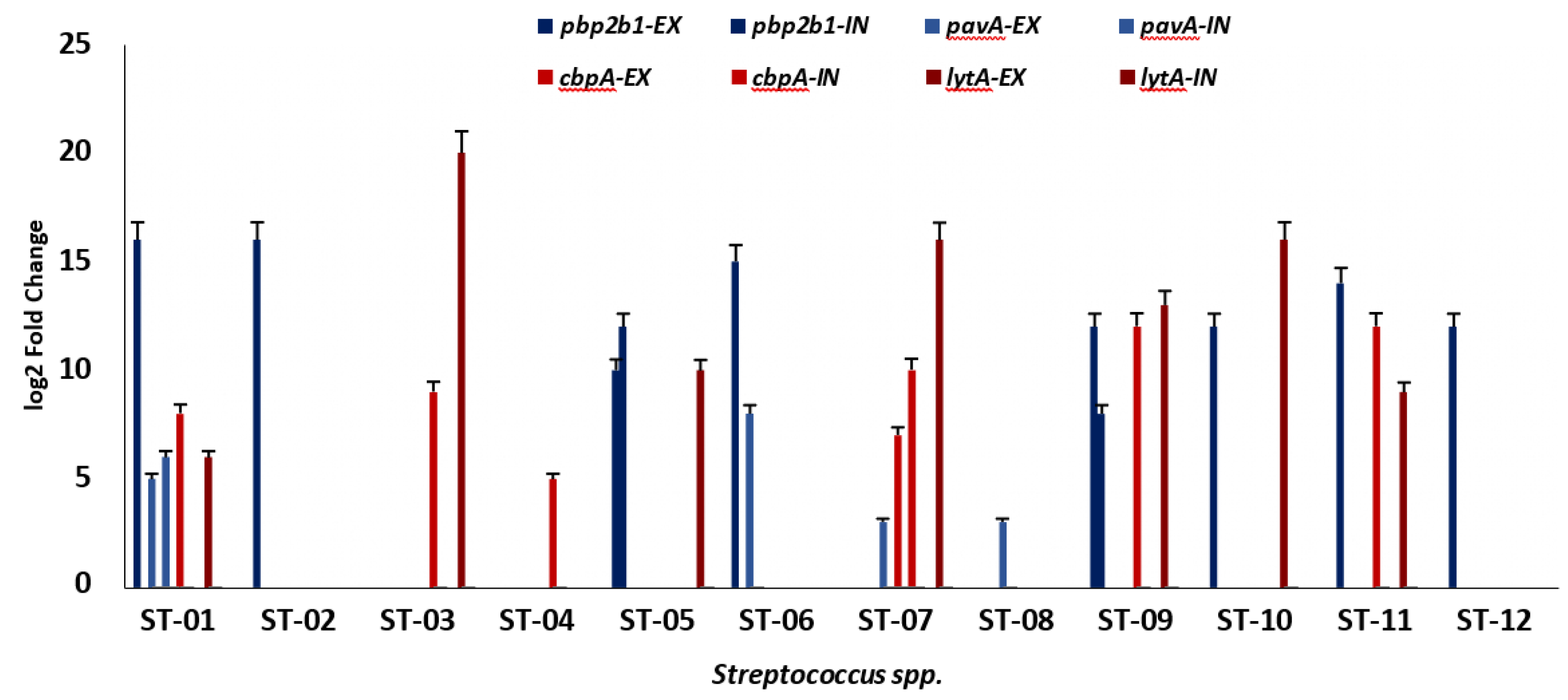

Virulence Markers Were Highly Expressed Under Antibiotic Stress

Transcriptional analysis of

pbp2b1, pavA cbpA, and

lytA virulence genes was performed after stress assays with 3X standard concentrations of azithromycin and doxycycline. The expression levels of each targeted gene were normalized with the reference gene,16S rRNA. The expression fold change was determined as log2 fold change relative to the control. At same the condition, there was variation in the fold change of the isolates. The

pbp2b1 gene (7.29 – 16.59 log2 fold change) was found to be highly expressed as compared to the

pavA gene (4.35 – 7.02 log2 fold change) in the presence of doxycycline (

Figure 3). Similarly, after azithromycin treatment, the

lytA gene (5.78 – 19.79 log2 fold change) displayed a higher expression fold change than the

cbpA genes (5.47 – 11.68 log2 fold change). Overall, all the target genes were upregulated as compared to the reference control after antibiotic treatment.

Discussion

Streptococcus spp. is among the WHO 'Critical Priority Pathogen' (Tacconelli et al., 2018) that have been implicated in secondary infections associated with COVID-19 (Anton-Vazquez & Clivillé, 2021; Ferrando et al., 2021) and their presence on nose mask pose a serious biosafety risk (Gyapong et al., 2023). Streptococcus pnuemoniae is a commensal in the upper respiratory tract and benefits from its hosts (Morimura et al., 2021). It also colonize the airways as a result of the expression of surface adhesins, causing invasive pneumococcal infections and neonatal sepsis, especially in immunocompromised individuals (Brooks & Mias, 2018). Virulence-associated markers such as ply, lytA, and pavA were identified in the isolated Streptococcus spp. suggest they have the potential to cause life-threatening infections. The choline-binding protein A gene (CbpA) identified in the S. pneumoniae facilitates binding to the platelet-activating factor receptor (PAF-R) present in epithelial and endothelial cells(Novick et al., 2017). This binding activates the PAF-R recycling pathway, enhancing the transport of the bacteria to the host's basal membrane, leading to the development of invasive disease (Maestro & Sanz, 2016). The penicillin-binding protein genes (pbp2b, pbp2b1) have been established to reduce the reactivity of β-lactam antibiotics such as penicillin, thereby reducing its effectiveness (Zhou et al., 2022). About 26% of the streptococcal species had pneumococcal adherence and virulence A gene (PavA) which mediates binding to fibronectin and integrin (Pracht et al., 2005). It facilitates adherence to the host surface and plays a vital role during meningitis and sepsis infections (Weiser et al., 2018).

Also, the autolysin gene (lytA, lytA1) was identified in all the Streptococcus species (100%) and has been reported to produce toxins that may be implicated in biofilm formation and fratricide (killing of non-competent pneumococci or other species) (Sakai et al., 2013). It causes the shedding of the capsule during the cellular invasion and releases pro-inflammatory cell wall fragments (Weiser et al., 2018). Moreover, the pneumolysin gene (ply), a pore-forming toxin, is known to be pro-apoptotic and cytotoxic for a range of host cells (Nishimoto et al., 2020). It also depletes serum opsonic activity and activates the classical complement pathway, inhibiting cough, migration of white blood cells and bactericidal activity (Hu et al., 2015). Bacteria develop antibiotic resistance through various mechanisms, including biofilm formation (Banin et al., 2017). Infections caused by resistant bacteria cause treatment failure, prolong hospital stays and higher medical costs (Dadgostar, 2019). Similar to previous studies, the Streptococcus isolates displayed resistance within 80-100% to the tested sixteen conventional antibiotics (Delanghe et al., 2021; Kebede et al., 2021; Nightingale et al., 2022). Streptococcus pneumonia showed 100% levels of resistance to penicillin and ampicillin. Penicillin-resistant S. pneumonia (PRSP) is a high critical priority pathogen (Asokan et al., 2019). It has been associated with community-acquired pneumonia with high mortality rates, particularly in immunocompromised individuals and children below 2 years (Cillóniz et al., 2018). The penicillin-associated resistance genes (pbp2b and pb2b1) and its ability to undergo capsular switching make this pathogen difficult to control (Wyres et al., 2013). Also, S. pneumonia displayed resistance to azithromycin (60%) and doxycycline (100%), which are used as a part of the COVID-19 treatment regimen in Ghana. It is alarming as this pathogen co-infect COVID-19 patients and could worsen the disease outcomes (Anton-Vazquez & Clivillé, 2021; Ferrando et al., 2021). The multiple antibiotic resistance indices of the Streptococcus species suggest they are potential high-risk pathogens indicating that combination therapy might not effectively control them. The prevalence of resistant bacteria from masks is not frequently reported; however, they still pose health risks to the user. Disinfectants are frequently used in homes and during outbreaks like COVID-19 to prevent disease transmission (Isawumi et al., 2021); however their excessive use has been linked to the development of drug resistance (Chen et al., 2021). At the user-recommended concentrations, So Klin and Dettol showed a relative level of effectiveness against streptococcal species but exhibited resistance between 60-100% at the recommended concentration of Bleach. The resistance level observed in the streptococcal isolates to the Bleach has been associated with the Heat shock protein 33 (Hsp33), which protects bacterial proteins against bleach aggregation (Michigan, 2008). Also, the bleach composition, sodium hypochlorite, which denatures bacterial protein, has been linked to resistance, as the bacterial outer membrane prevents it from reaching its target site (Acsa et al., 2021).The washing of nose masks with these disinfectants, has been linked to reduced mask filtration and may expose the user to COVID-19 and other associated respiratory infections (Dewey et al., 2022).

Bacterial pathogenicity has been associated with its virulence genes (Beceiro et al., 2013) (WHO, 2020). As such, the differential expression of virulence genes (pbp2b1, lytA, pavA, cbpA) in the isolated streptococcal species in response to antibiotic stress (azithromycin and doxycycline) was examined in this study. All the isolates showed high levels of expression relative to the control, suggesting that they are potentially pathogenic. Similar to previous studies, bacteria exposure to resistant antibiotics increased their virulence, especially during infections (Guillard et al., 2016). Three virulence markers investigated in this study, lytA, pavA, and cbpA, which were also upregulated, have been considered potential vaccine targets (Corsini et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2019). This indicates that they are highly conserved and may elicit protective immunity across streptococcal species.

Conclusions

This study emphasizes the need to assess mask usage, particularly in vulnerable populations. Also, to provide insights into how nose masks can harbor opportunistic pathogens and facilitate disease transmission. Additionally, the upregulation of virulence-associated markers indicated that Streptococcus pneumonia isolated from nose masks is of clinical relevance. The presence of azithromycin resistance markers in the Streptococcus isolates is of public health concern as it is used in COVID-19 treatment therapy. Therefore, AMR surveillance efforts must be intensified to fight AMR in Ghana and Africa. For instance, discouraging the inappropriate use of antibiotics and prioritizing prevention over treatment.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary images: Figure SA (Capsulation of the

Streptococcus isolates), Figure SB (Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR-amplified 16S rRNA and

sodA gene), Figure SC (Agarose gel electrophoresis of virulence and resistance markers) are available here

https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.23989959.v1.

Author Contributions

AI conceptualized the study. FG and AI designed the study, investigated, obtained, processed, analyzed and interpreted the data. FG and AI prepared the first draft of the manuscript. AI revised the draft for important intellectual content. All the authors approved the final draft of the manuscript for submission.

Funding

Francis Gyapong was supported by funds from a World Bank African Centre of Excellence grant (ACE02-WACCBIP) and a DELTAS Africa grant (DEL-15-007) to Gordon Awandare of the West African Centre for Cell Biology of Infectious Pathogens (WACCBIP).

Institutional Review Board

The study was conducted in accordance with approval from Ethics Committee for Basic and Applied Sciences, University of Ghana (ECBAS 078/20-21).

Informed Consent

No human samples were used in this study; however, Informed consent was obtained from all participants that donated their nose masks for analysis.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all the volunteers who participated in the study. Members of AMR Research Group (led by Abiola Isawumi), especially Molly Kukua Abban and Eunice Ampadubea Ayerakwa for technical supports.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare with co-authors or the funding body.

References

- Acsa, I., Lilly Caroline, B., Philip Njeru, N., & Lucy Wanjiru, N. (2021). Preliminary Study on Disinfectant Susceptibility/Resistance Profiles of Bacteria Isolated from Slaughtered Village Free-Range Chickens in Nairobi, Kenya. Int J Microbiol, 2021, 8877675. [CrossRef]

- Amin, P. (2022). Life after COVID-19: Future directions? In (pp. 211-226). 324 . [CrossRef]

- Anton-Vazquez, V., & Clivillé, R. (2021). Streptococcus pneumoniae coinfection in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, 40(6), 1353-1355. [CrossRef]

- Asokan, G. V., Ramadhan, T., Ahmed, E., & Sanad, H. (2019). WHO Global Priority Pathogens List: A Bibliometric Analysis of Medline-PubMed for Knowledge Mobilization to Infection Prevention and Control Practices in Bahrain. Oman Med J, 34(3), 184-193. [CrossRef]

- Banin, E., Hughes, D., & Kuipers, O. P. (2017). Editorial: Bacterial pathogens, antibiotics and antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 41(3), 450-452. [CrossRef]

- Beceiro, A., Tomás, M., & Bou, G. (2013). Antimicrobial resistance and virulence: a successful or deleterious association in the bacterial world? Clin Microbiol Rev, 26(2), 185-230. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J. T., & Butler, J. C. (2021). Effectiveness of Mask Wearing to Control Community Spread of SARS-CoV-2. JAMA, 325(10), 998-999. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, L. R. K., & Mias, G. I. (2018). Streptococcus pneumoniae's Virulence and Host Immunity: Aging, Diagnostics, and Prevention. Front Immunol, 9, 1366. [Record #449 is using a reference type undefined in this output style.]. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D., Wen, S., Feng, D., Xu, R., Liu, J., Peters, B. M., Su, D., Lin, Y., Yang, L., Xu, Z., & Shirtliff, M. E. (2018). Microbial virulence, molecular epidemiology and pathogenic factors of fluoroquinolone-resistant Haemophilus influenzae infections in Guangzhou, China. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials, 17(1), 41. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Guo, J., Jiang, Y., & Shao, Y. (2021). High concentration and high dose of disinfectants and antibiotics used during the COVID-19 pandemic threaten human health. Environmental Sciences Europe, 33(1), 11. [CrossRef]

- Christenson, J. C., Korgenski, E. K., & Relich, R. F. (2018). 286 - Laboratory Diagnosis of Infection Due to Bacteria, Fungi, Parasites, and Rickettsiae. In S. S. Long, C. G. Prober, & M. Fischer (Eds.), Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases (Fifth Edition) (pp. 1422-1434.e1423). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, A. A., Stelzer-Braid, S., Rawlinson, W., Pontivivo, G., Wang, Q., Pan, Y., Zhang, D., Zhang, Y., Li, L., & MacIntyre, C. R. (2019). Contamination by respiratory viruses on outer surface of medical masks used by hospital healthcare workers. BMC infectious diseases, 19(1), 491. [CrossRef]

- Cillóniz, C., Garcia-Vidal, C., Ceccato, A., & Torres, A. (2018). Antimicrobial Resistance Among Streptococcus pneumoniae. In I. W. Fong, D. Shlaes, & K. Drlica (Eds.), Antimicrobial Resistance in the 21st Century (pp. 13-38). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- CLSI. (2020). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (30th ed., Vol. CLSI supplement M100). Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. https://www.nih.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/CLSI-2020.pdf.

- Corsini, B., Aguinagalde, L., Ruiz, S., Domenech, M., & Yuste, J. (2021). Vaccination with LytA, LytC, or Pce of Streptococcus pneumoniae Protects against Sepsis by Inducing IgGs That Activate the Complement System. Vaccines (Basel), 9(2). [CrossRef]

- Dadgostar, P. (2019). Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications and Costs. Infect Drug Resist, 12, 373 3903-3910. [CrossRef]

- Darkwah, T. O., Afriyie, D. K., Sneddon, J., Cockburn, A., Opare-Addo, M. N. A., Tagoe, B., & Amponsah, S. K. (2021). Assessment of prescribing patterns of antibiotics using National Treatment Guidelines and World Health Organization prescribing indicators at the Ghana Police Hospital: a pilot study. Pan Afr Med J, 39, 222. [CrossRef]

- Delanghe, L., Cauwenberghs, E., Spacova, I., De Boeck, I., Van Beeck, W., Pepermans, K., Claes, I., Vandenheuvel, D., Verhoeven, V., & Lebeer, S. (2021). Cotton and Surgical Face Masks in Community Settings: Bacterial Contamination and Face Mask Hygiene. Front Med (Lausanne), 8, 732047. [CrossRef]

- Dewey, H. M., Jones, J. M., Keating, M. R., & Budhathoki-Uprety, J. (2022). Increased Use of Disinfectants During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Potential Impacts on Health and Safety. ACS Chemical Health & Safety, 29(1), 27-38. [Record #735 is using a reference type undefined in this output style.]. [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, M. L., Coghe, F., Scano, A., Carta, M. G., & Orru, G. (2021). Co-infection of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Respiratory Infections Caused by SARS-CoV-2. Biointerface Research in Applied Chemistry, 11(4), 12170-12177. [CrossRef]

- Guillard, T., Pons, S., Roux, D., Pier, G. B., & Skurnik, D. (2016). Antibiotic resistance and virulence: Understanding the link and its consequences for prophylaxis and therapy. BioEssays, 38(7), 682-693. [CrossRef]

- Gund, M., Isack, J., Hannig, M., Thieme-Ruffing, S., Gärtner, B., Boros, G., & Rupf, S. (2021). Contamination of surgical mask during aerosol-producing dental treatments. Clin Oral Investig, 25(5), 3173-3180. [CrossRef]

- Gyapong, F., Debra, E., Ofori, M., Ayerakwa, E., Abban, M., Mosi, L., & Isawumi, A. (2023). Multi-drug resistant microbes are resident on nose masks used as preventive protocols for COVID-19 in selected Ghanaian cohort [version 1; peer review: 1 not approved]. Wellcome Open Research, 8(250). [CrossRef]

- Hu, D. K., Liu, Y., Li, X. Y., & Qu, Y. (2015). In vitro expression of Streptococcus pneumoniae ply gene in human monocytes and pneumocytes. Eur J Med Res, 20(1), 52. [CrossRef]

- Hu, D. K., Wang, D. G., Liu, Y., Liu, C. B., Yu, L. H., Qu, Y., Luo, X. H., Yang, J. H., Yu, J., Zhang, J., & Li, X. Y. (2013). Roles of virulence genes (PsaA and CpsA) on the invasion of Streptococcus pneumoniae into blood system. Eur J Med Res, 18(1), 14. [CrossRef]

- Isawumi, A., Donkor, J., & Mosi, L. (2021). In vitro inhibitory effects of commercial antiseptics and disinfectants on foodborne and environmental bacterial strains [version 2; peer review: 1 approved, 1 approved with reservations]. Open Research Africa, 3(54). [CrossRef]

- Kebede, D., Admas, A., & Mekonnen, D. (2021). Prevalence and antibiotics susceptibility profiles of Streptococcus pyogenes among pediatric patients with acute pharyngitis at Felege Hiwot Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Microbiology, 21(1), 135. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M., Ramsheh, M. Y., Williams, C. M. L., Auty, J., Haldar, K., Abdulwhhab, M., Brightling, C. E., & Barer, M. R. (2018). Face mask sampling reveals antimicrobial resistance genes in exhaled aerosols from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and healthy volunteers. BMJ Open Respir Res, 5(1), e000321. [CrossRef]

- Kisling, L. A., & Das, J. M. (2022). Prevention Strategies. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537222/.

- Livak, K. J., & Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods, 25(4), 402-408. [CrossRef]

- Maestro, B., & Sanz, J. M. (2016). Choline Binding Proteins from Streptococcus pneumoniae: A Dual Role as Enzybiotics and Targets for the Design of New Antimicrobials. Antibiotics (Basel), 5(2). [CrossRef]

- Marín, M., Cercenado, E., Sánchez-Carrillo, C., Ruiz, A., Gómez González, Á., Rodríguez-Sánchez, B., & Bouza, E. (2017). Accurate Differentiation of Streptococcus pneumoniae from other Species within the Streptococcus mitis Group by Peak Analysis Using MALDI-TOF MS [Original Research]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 8. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00698.

- Michigan, U. (2008). How Household Bleach Kills Bacteria Retrieved January 16, 2023 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/11/081113140314.htm.

- Monalisa, A., Padma, K., Manjunath, K., Hemavathy, E., & Varsha, D. (2017). Microbial contamination of the mouth masks used by post-graduate students in a private dental institution: An In-Vitro Study. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci, 16, 61-67. https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jdms/papers/Vol16-issue5/Version-4/N1605046167.pdf.

- Morimura, A., Hamaguchi, S., Akeda, Y., & Tomono, K. (2021). Mechanisms Underlying Pneumococcal Transmission and Factors Influencing Host-Pneumococcus Interaction: A Review [Review]. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 11. [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, M., Mody, M., Rickard, A., & Cassone, M. (2022). Bacterial contamination on used face masks in healthcare personnel. Antimicrobial Stewardship & Healthcare Epidemiology, 2(S1), s86-s87. [CrossRef]

- Nishimoto, A. T., Rosch, J. W., & Tuomanen, E. I. (2020). Pneumolysin: Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Target [Mini Review]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 11. [CrossRef]

- Novick, S., Shagan, M., Blau, K., Lifshitz, S., Givon-Lavi, N., Grossman, N., Bodner, L., Dagan, R., & Mizrachi Nebenzahl, Y. (2017). Adhesion and invasion of Streptococcus pneumoniae to primary and secondary respiratory epithelial cells. Mol Med Rep, 15(1), 65-74. [CrossRef]

- Pracht, D., Elm, C., Gerber, J., Bergmann, S., Rohde, M., Seiler, M., Kim, K. S., Jenkinson, H. F., Nau, R., & Hammerschmidt, S. (2005). PavA of Streptococcus pneumoniae modulates adherence, invasion, and meningeal inflammation. Infect Immun, 73(5), 2680-2689. [CrossRef]

- Rao, X., Huang, X., Zhou, Z., & Lin, X. (2013). An improvement of the 2ˆ(-delta delta CT) method for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction data analysis. Biostat Bioinforma Biomath, 3(3), 71-85. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4280562/.

- Roberge, R. J., Bayer, E., Powell, J. B., Coca, A., Roberge, M. R., & Benson, S. M. (2010). Effect of exhaled moisture on breathing resistance of N95 filtering facepiece respirators. Annals of occupational hygiene, 54(6), 671-677. [CrossRef]

- Sakai, F., Talekar, S. J., Lanata, C. F., Grijalva, C. G., Klugman, K. P., & Vidal, J. E. (2013). Expression of Streptococcus pneumoniae Virulence-Related Genes in the Nasopharynx of Healthy Children. PLoS One, 8(6), e67147. [CrossRef]

- Tacconelli, E., Carrara, E., Savoldi, A., Harbarth, S., Mendelson, M., Monnet, D. L., Pulcini, C., Kahlmeter, G., Kluytmans, J., Carmeli, Y., Ouellette, M., Outterson, K., Patel, J., Cavaleri, M., Cox, E. M., Houchens, C. R., Grayson, M. L., Hansen, P., Singh, N., Theuretzbacher, U., & Magrini, N. (2018). Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis, 18(3), 318-327 . [CrossRef]

- Teo, W. L. (2021). The "Maskne" microbiome - pathophysiology and therapeutics. Int J Dermatol, 477 60(7), 799-809. [CrossRef]

- Weiser, J. N., Ferreira, D. M., & Paton, J. C. (2018). Streptococcus pneumoniae: transmission, colonization and invasion. Nat Rev Microbiol, 16(6), 355-367. [CrossRef]

- White, J. K., Nielsen, J. L., Poulsen, J. S., & Madsen, A. M. (2021). Antifungal Resistance in Isolates of Aspergillus from a Pig Farm. Atmosphere, 12(7), 826. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4433/12/7/826.

- WHO. (2020). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (last cited: 04 February, 2023).

- Wu, G., Yang, Q., Long, M., Guo, L., Li, B., Meng, Y., Zhang, A., Wang, H., Liu, S., & Zou, L. (2015). Evaluation of agar dilution and broth microdilution methods to determine the disinfectant susceptibility. The Journal of Antibiotics, 68(11), 661-665. [CrossRef]

- Wyres, K. L., Lambertsen, L. M., Croucher, N. J., McGee, L., von Gottberg, A., Liñares, J., Jacobs, M. R., Kristinsson, K. G., Beall, B. W., Klugman, K. P., Parkhill, J., Hakenbeck, R., Bentley, S. D., & Brueggemann, A. B. (2013). Pneumococcal capsular switching: a historical perspective. J Infect Dis, 207(3), 439-449. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W., Pan, F., Wang, B., Wang, C., Sun, Y., Zhang, T., Shi, Y., & Zhang, H. (2019). Epidemiology Characteristics of Streptococcus pneumoniae From Children With Pneumonia in Shanghai: A Retrospective Study [Original Research]. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology, 9. [CrossRef]

- Zhiqing, L., Yongyun, C., Wenxiang, C., Mengning, Y., Yuanqing, M., Zhenan, Z., Haishan, W., Jie, Z., Kerong, D., Huiwu, L., Fengxiang, L., & Zanjing, Z. (2018). Surgical masks as source of bacterial contamination during operative procedures. J Orthop Translat, 14, 57-62. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M., Wang, L., Wang, Z., Kudinha, T., Wang, Y., Xu, Y., & Liu, Z. (2022). Molecular Characterization of Penicillin-Binding Protein2x, 2b and 1a of Streptococcus pneumoniae Causing Invasive Pneumococcal Diseases in China: A Multicenter Study [Original Research]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 13. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).