Submitted:

09 August 2024

Posted:

12 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

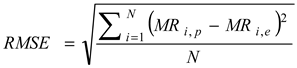

1. Introduction

- working pressure,

- the flow of supplied heat (in the case of contact heating - shelf temperature),

- safety pressure.

| Material | Sample preparation | Freeze-drying parameters | Ref. | ||

| Apple | slices 4 and 8 mm | T (condenser) = −48°C IR lamp (T = lack of data), Pressure = 13.3 Pa Material temperature control: no |

[20] | ||

| Apple | slices 5 mm | T shelf variable during the process: 20_45_55_50°C, T (condenser) = −40° Pressure= 100 Pa, Time 15 h Material temperature control: yes |

[21] | ||

| Apple | rectangular size 17 x 17 x 10 mm | T= 70°C°C and Pressure = 40-45 Pa (sublimation) T=90°C, Pressure = 30–35 Pa (desorption) Material temperature control: no |

[22] | ||

| Apple puree gel | cylinder with d= 13.5 mm, height of 13. 7 mm | T (shelf) = 20°C Pressure = 63 Pa, Time =24 h Material temperature control: no |

[23] | ||

| Banana | cylindrical shape with a d= 20 mm and thickness from 10 to 20 mm | Temperature of IR radiator range of 50–70°C Pressure =0.5 Pa Time =6 h Material temperature control: no |

[24] | ||

| Blackberries | Juice with carrier agents | T = –84°C (shelf or condenser T- not reported) Pressure: 4 Pa, Time: 48 h Material temperature control: no |

[25] | ||

| Carrot | 3-4 mm slices | T (shelf) = 30°C, T (condenser) = –60°C Pressure = 6 Pa, Time =n/a Material temperature control: no |

[26] | ||

| Carrot | cylinders of 4.5 mm diameter and 7. mm thickness | T (shelf) = 25°C Pressure = 60 Pa, Time =24 h Material temperature control: no |

[27] | ||

| Carrot and horseradish |

0.5 cm slices | Primary drying: T (shelf) = –35°C, Pressure = 50 Pa Secondary drying: Pressure = 4 Pa, T rising continually to +18°C Material temperature control: no |

[28] | ||

| Guava and papaya | 1x1x1 cm cubes | T (shelf) = 10°C Pressure = less than 613.2 Pa, Time =24h Material temperature control: no |

[29] | ||

| Model instant powder solution |

model spheres (d= 2 cm) with sucrose coating | Isotherm at T = (−7)°C (12 h) Isotherm at T =(−3)°C (12 h) Isothermal drying at T=−27°C ( 5 h) T ramp from −27°C to 20°C at 1°C/min T ramp from −70°C to 20°C at 4°C/h Isotherm at T =−60°C for 20 h T ramp from −60°C to 20°C at 4°C/h T ramp from(−60°C to −40°C at 0.5°C/h T ramp from −40°C to 20°C at 1.25°C/h Pressure 20 Pa Material temperature control: no |

[19] | ||

| Pineapple, cherry, guava, papaya, and mango | pulp, thickness of 1 cm | T = –30°C (shelf or condenser T-not reported), Pressure= 130 Pa, Time 12 h Material temperature control: yes |

[30] | ||

| Pumpkin, green bell pepper | samples of 2 x 2 cm | T = between–47 and –50°C (shelf or condenser T- not reported), Pressure= 0.67 Pa, Time 38 h Material temperature control: no |

[31] | ||

| Snack with apple or chokeberry pomace | 14 × 10 × 2.5 cm | T (shelf) = 30°C, Pressure = 63 Pa Time =48 h |

[32] | ||

| Strawberry | slices 5 or 10 mm, or whole fruits | T shelf (30, 40, 50, 60 and 70°C) T (condenser) = −92°C Vacuum level of less than 5 ml Time: 12 h in the case of slices and 24 and 48 h in the case of whole fruits Material temperature control: yes |

[33] | ||

| Vegetable soups | cylindrical container d= 20 cm, height=2 cm | T (shelf) = 20°C, T (condenser) = −55°C Pressure = 63 Pa, Time =24 h Material temperature control: no |

[34] | ||

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

2.2. Freezing of Samples

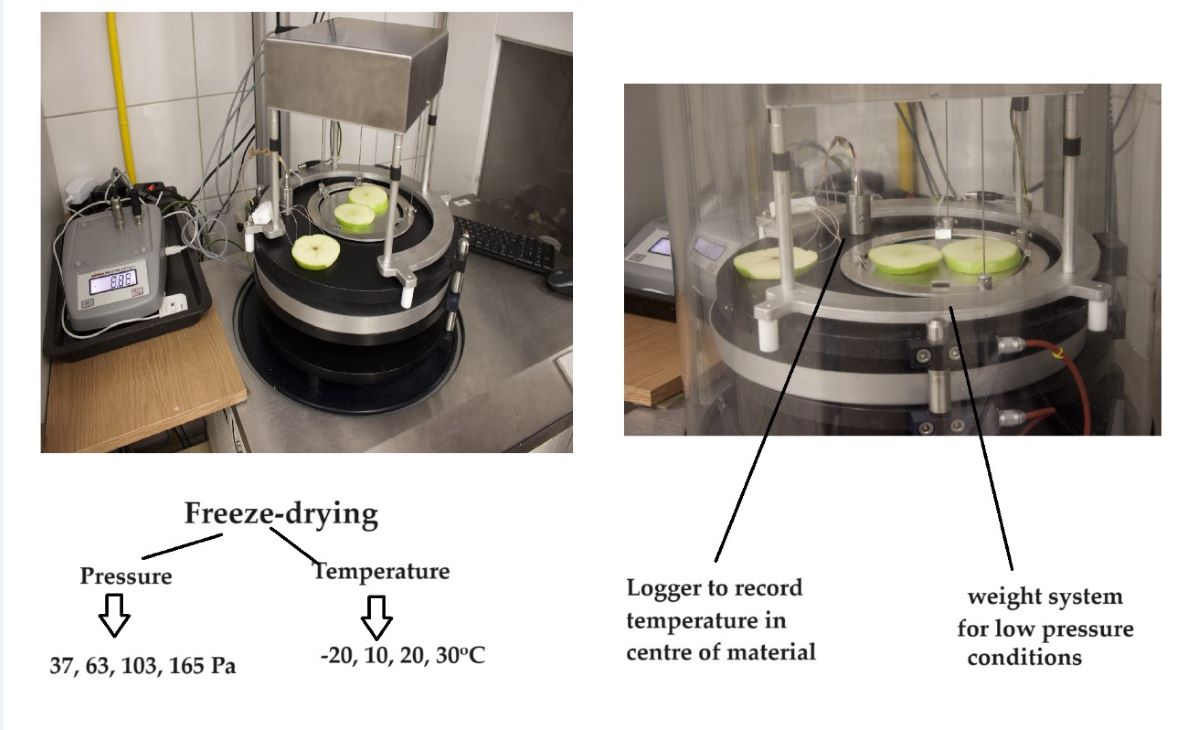

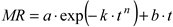

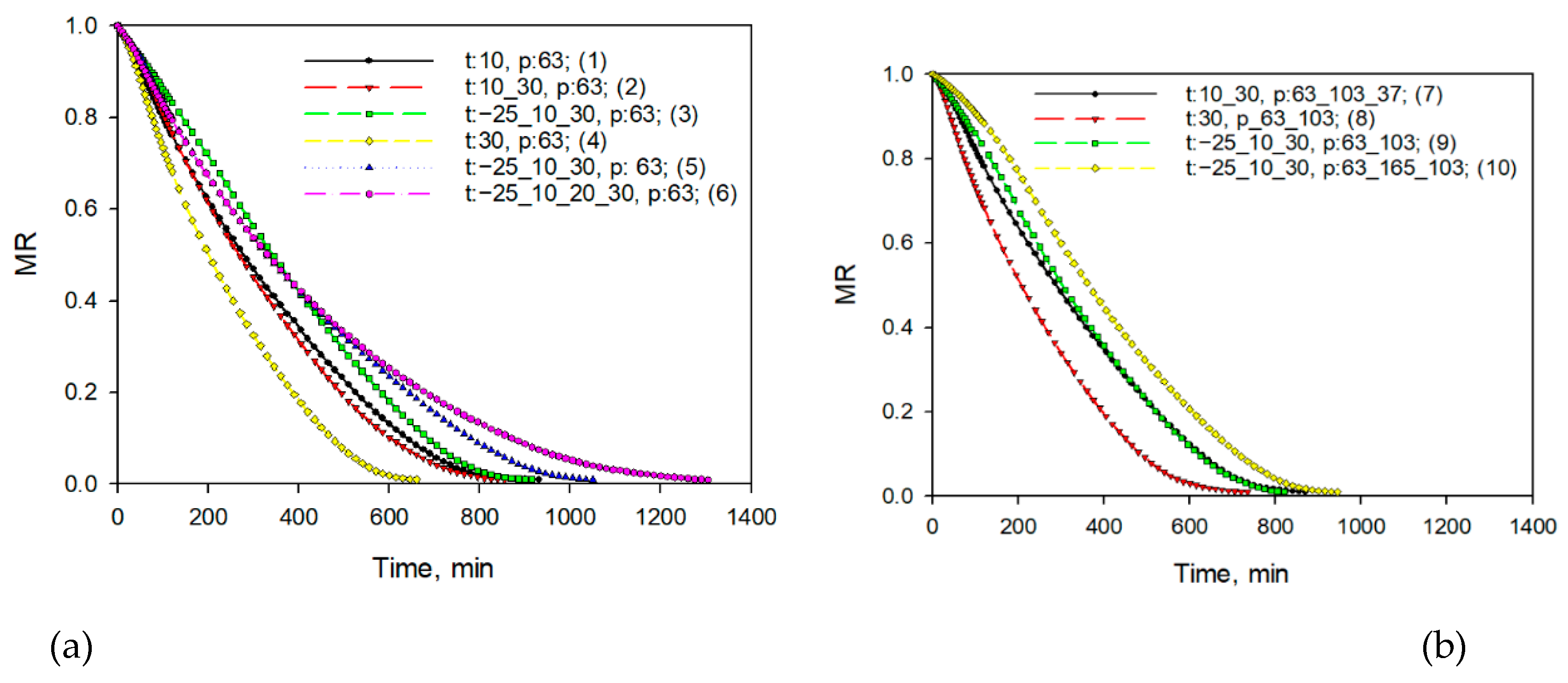

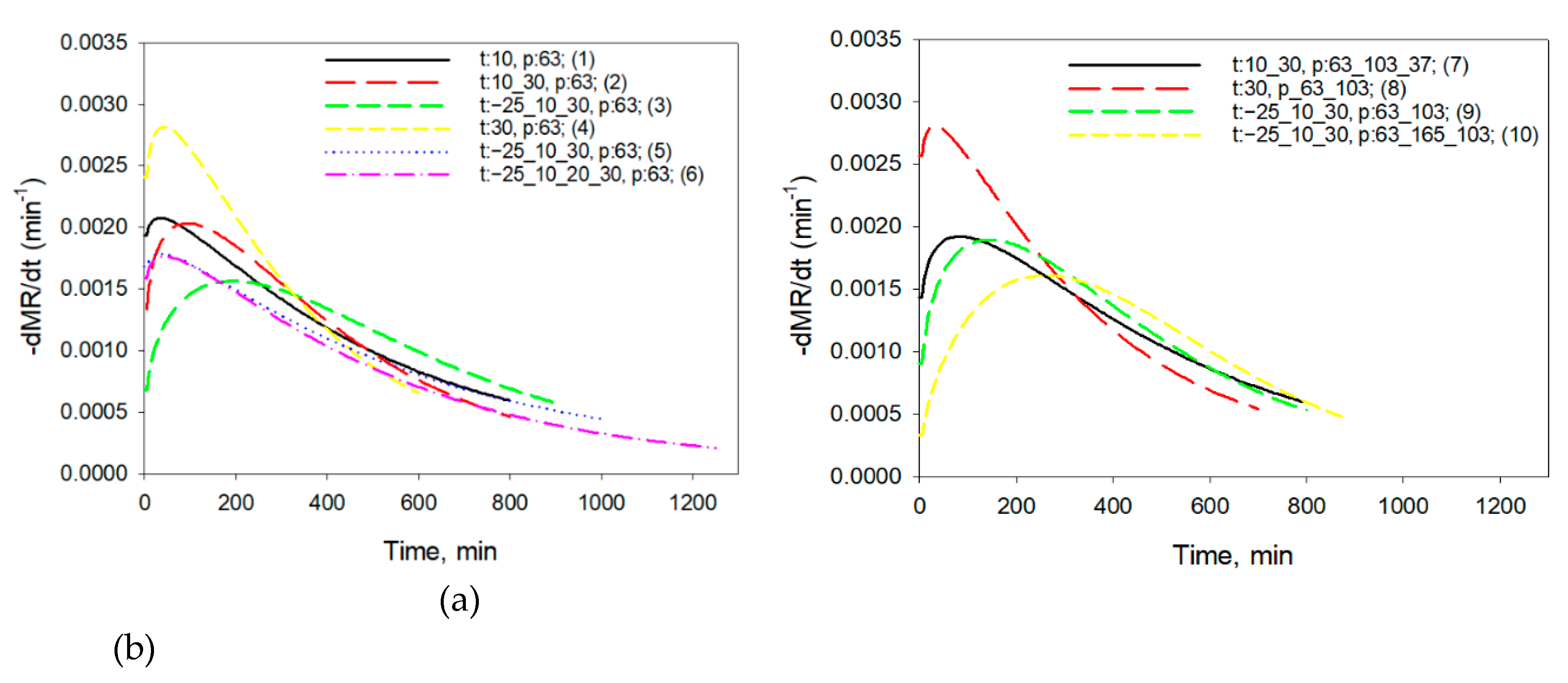

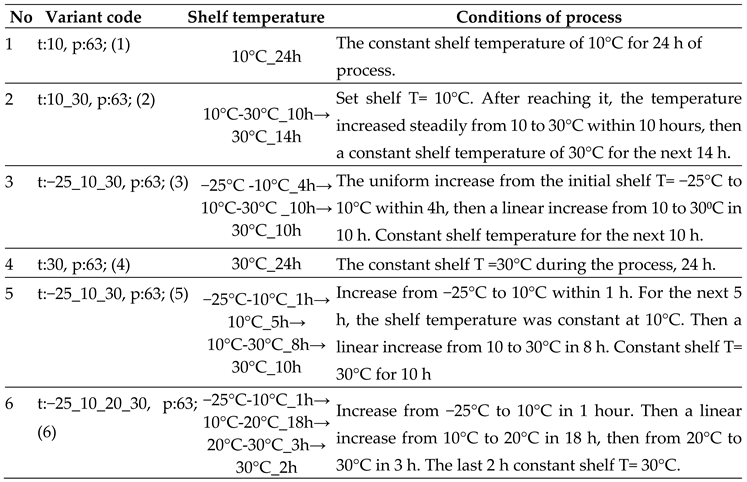

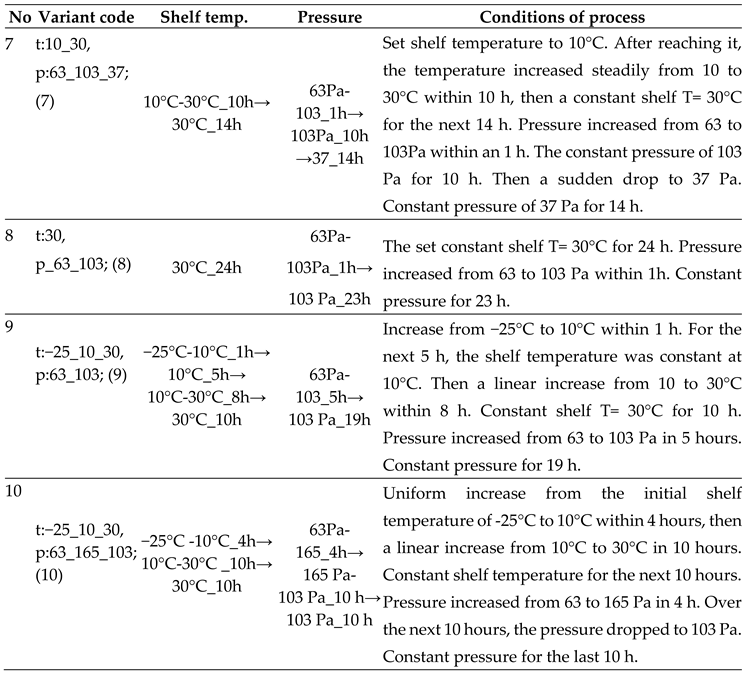

2.4. Kinetics of the Freeze-Drying at Different Process Parameters

2.5. Water Sorption Kinetics

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

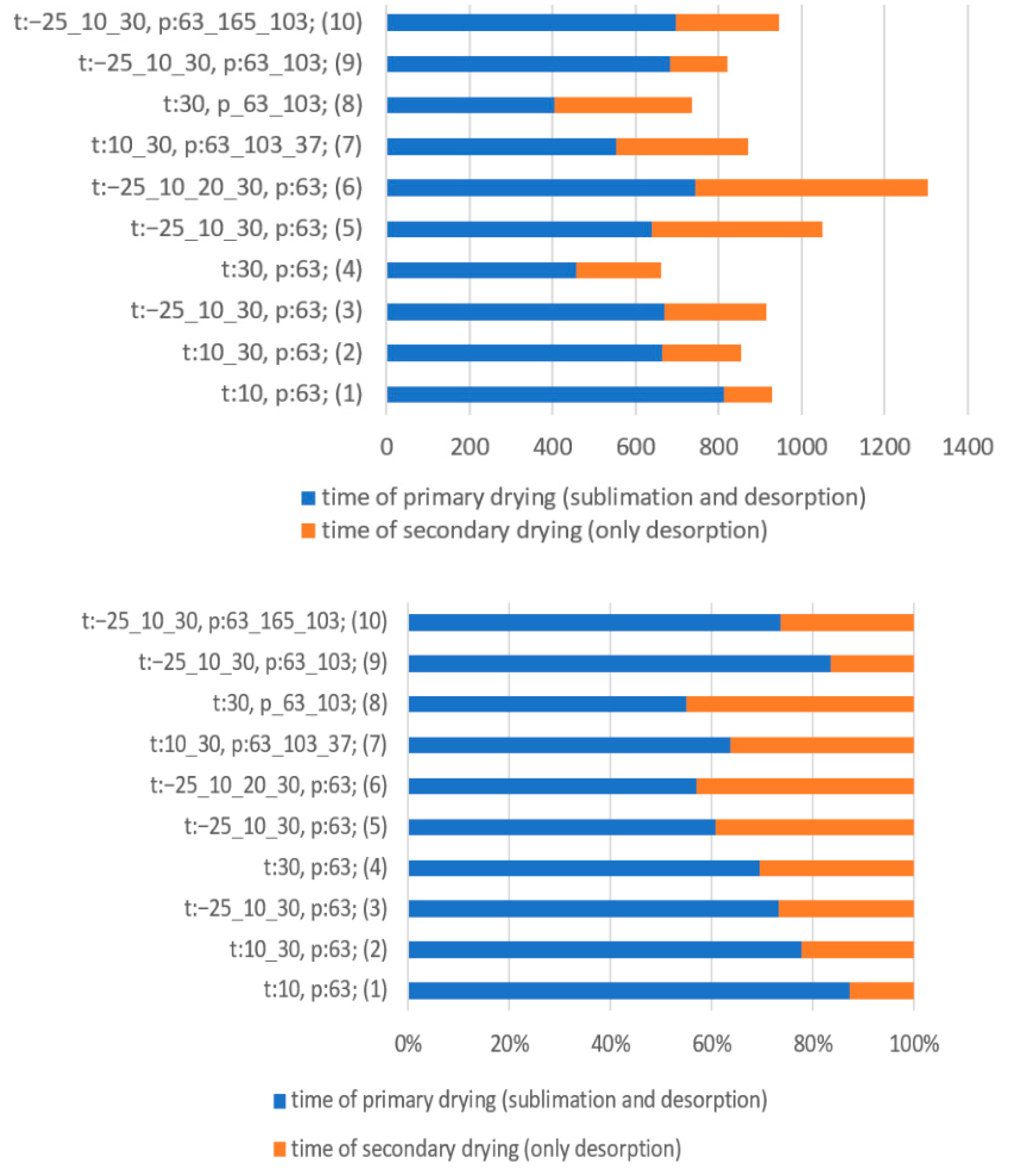

3.1. Freeze-Drying Kinetics of Apple Slices at Different Conditions of the Process

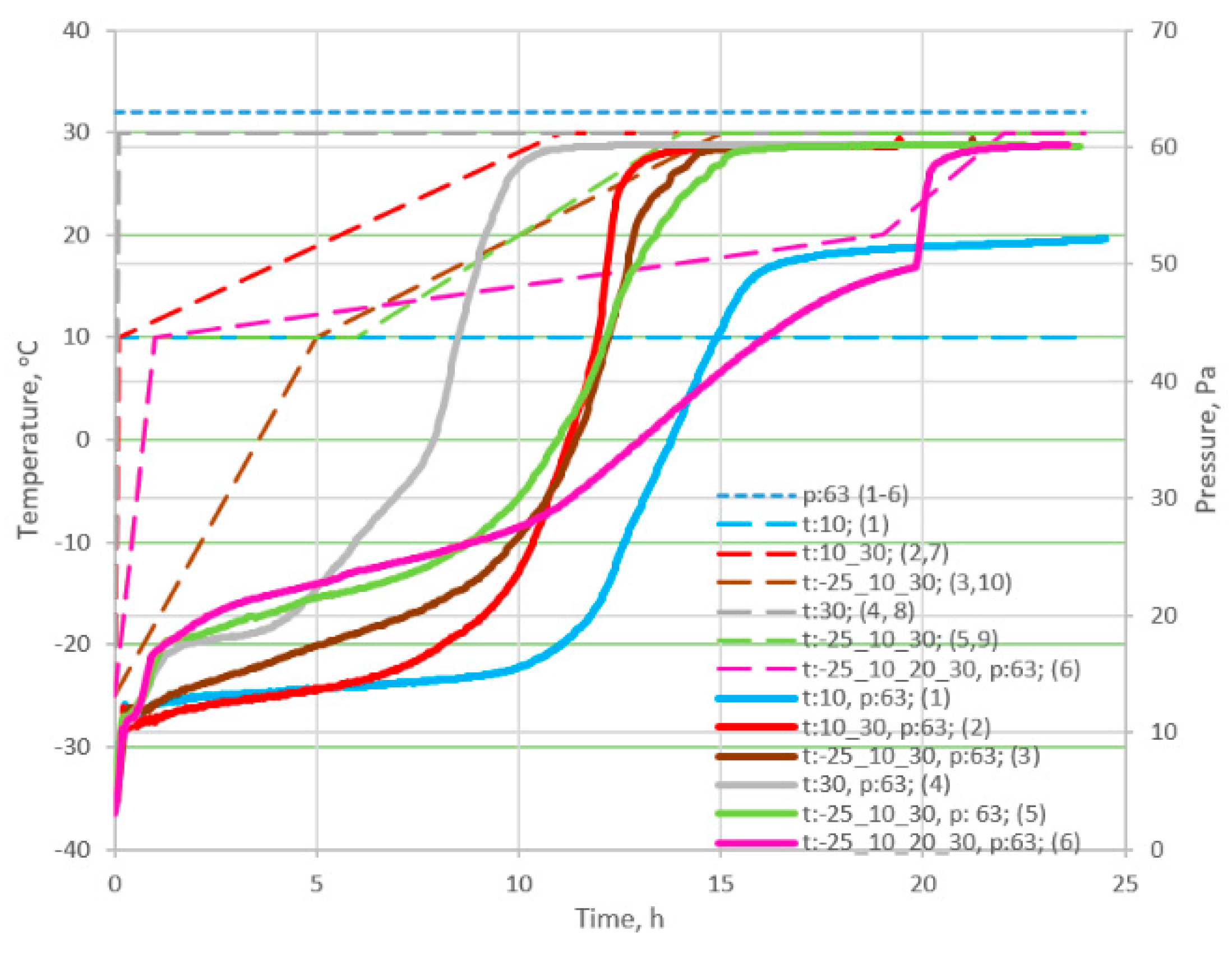

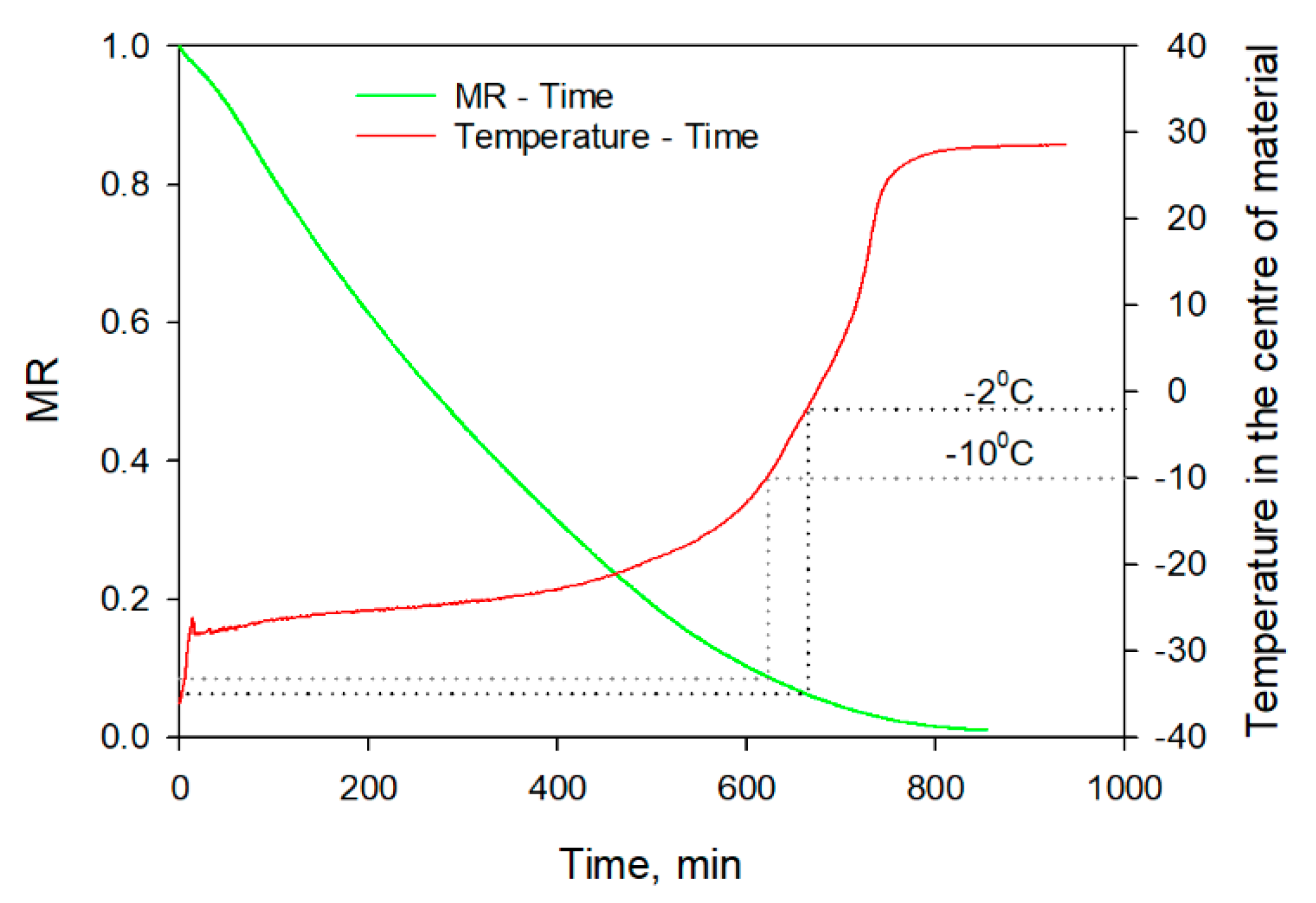

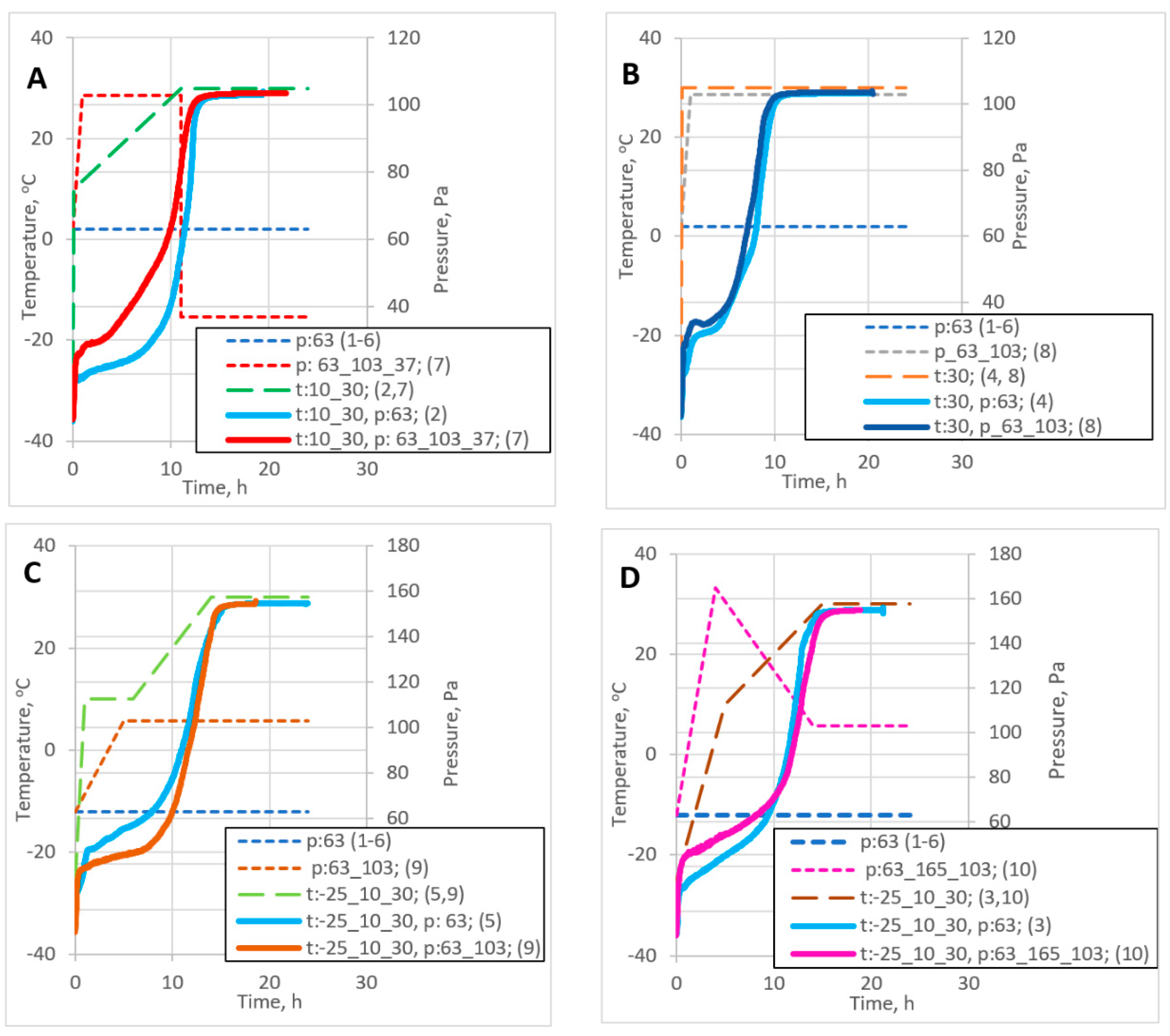

3.2. Effect of Changes in the Set Freeze-Drying Parameters on the Material Temperature

3.2.1. Effect of Changes in the Set Shelf Temperature

3.2.2. Effect of Changes in the Set Pressure

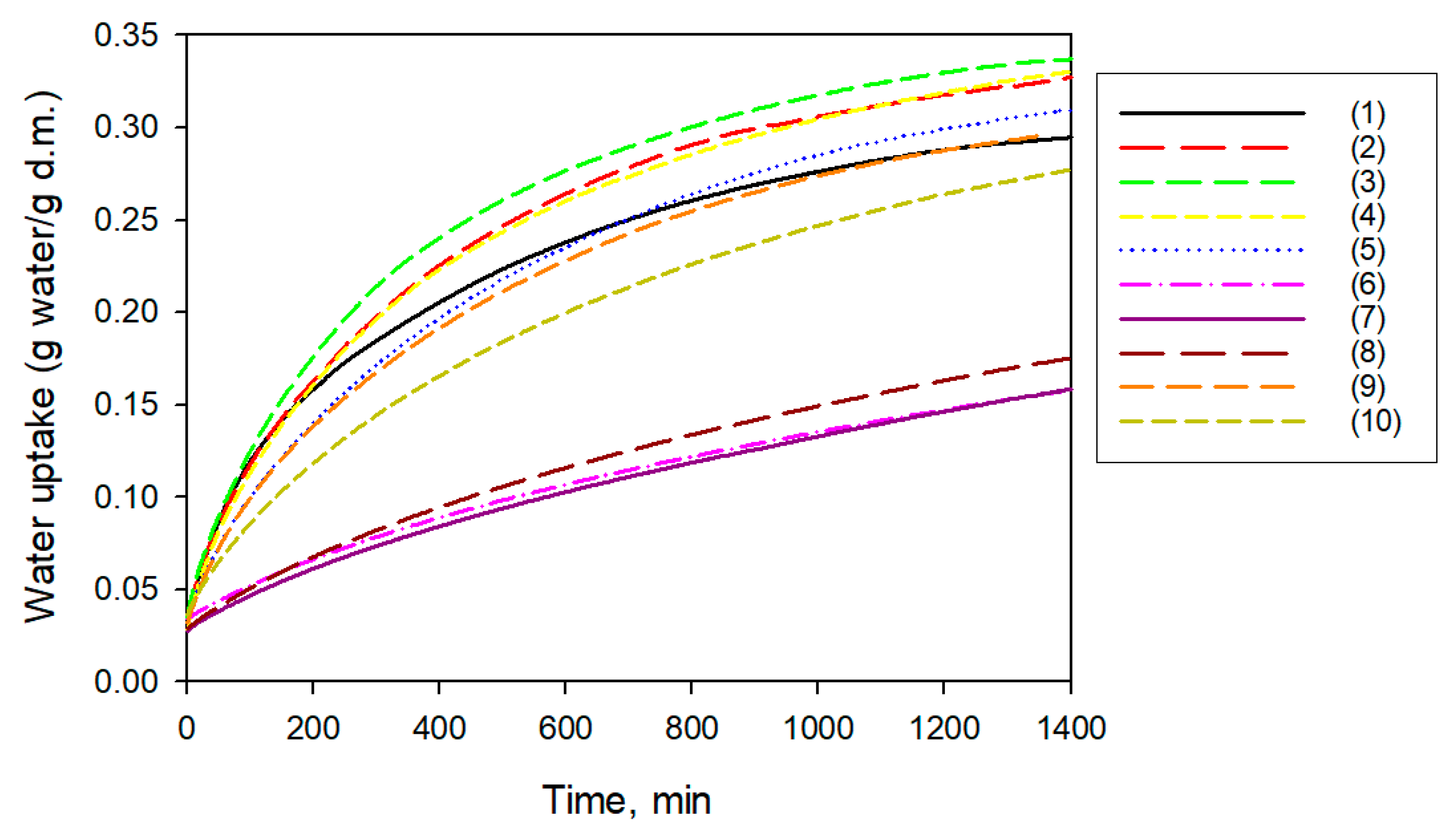

3.3. Sorption Kinetics of Freeze-Dried Apples

3.4. Critical Evaluation of Applied Parameters during Freeze-Drying

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nowak, D.; Jakubczyk, E. The freeze-drying of foods-the characteristic of the process course and the effect of its parameters on the physical properties of food materials. Foods 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.H.; Bi, J.F.; Laaksonen, T.; Laurén, P.; Yi, J.Y. Texture of freeze-dried intact and restructured fruits: Formation mechanisms and control technologies. Trends Food Sci. 2024, 143, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.; Piechucka, P.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Wiktor, A. Impact of material structure on the course of freezing and freeze-drying and on the properties of dried substance, as exemplified by celery. J Food Eng. 2016, 180, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waghmare, R.B.; Perumal, A.B.; Moses, J.A.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. 3.05 - Recent Developments in Freeze Drying of Foods: A comprehensive review. In Innovative Food Processing Technologies, Knoerzer, K., Muthukumarappan, K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2021; Volume 3, pp. 82–99. [Google Scholar]

- Morais, A.R.; Alencar, É.N.; Xavier Júnior, F.H.; Oliveira, C.M.; Marcelino, H.R.; Barratt, G.; Fessi, H.; Egito, E.S.T.; Elaissari, A. Freeze-drying of emulsified systems: A review. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 503, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assegehegn, G.; Brito-de la Fuente, E.; Franco, J.M.; Gallegos, C. The Importance of Understanding the Freezing Step and Its Impact on Freeze-Drying Process Performance. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 108, 1378–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.L.; Pikal, M.J. Design of freeze-drying processes for pharmaceuticals: Practical advice. Pharm. Res. 2004, 21, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assegehegn, G.; Brito-de la Fuente, E.; Franco, J.M.; Gallegos, C. Freeze-drying: A relevant unit operation in the manufacture of foods, nutritional products, and pharmaceuticals. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2020, 93, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pikal, M.J. Lyophilization. In Encyclopedia of Pharmaceutical Technology, Swarbrick, J., Boylan, J., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, USA, 2002; pp. 1299–1326. [Google Scholar]

- Merivaara, A.; Zini, J.; Koivunotko, E.; Valkonen, S.; Korhonen, O.; Fernandes, F.M.; Yliperttula, M. Preservation of biomaterials and cells by freeze-drying: Change of paradigm. JCR 2021, 336, 480–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado, J.A.; Matas, A.J.; Posé, S. Fruit and vegetable texture: Role of their cell walls. In Reference Module in Food Science, Kırtıl, E., Öztop, H.M., Eds.; Elsevier Science,: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Haseley, P.; Oetjen, G.W. Freeze-Drying; Wiley-VCH: Veinheim, Germany, 2018; p. 421. [Google Scholar]

- Genin, N.; Rene, F. Influence of freezing rate and the ripeness state of fresh courgette on the quality of freeze-dried products and freeze-drying time. Journal of Food Engineering 1996, 29, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D. The innovative measurement system of the kinetic of freeze-drying and sorption properties of dried products as a tool for controlling and assessing the course of freeze-drying Warsaw University of Life Sciences Press Warsaw, Poland 2017.

- Nowak, D.; Jakubczyk, E. Effect of pulsed electric field pre-treatment and the freezing methods on the kinetics of the freeze-drying process of apple and its selected physical properties. Foods 2022, 11, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, B.R.; Howes, T. Implication of glass transition for the drying and stability of dried foods. J. Food Eng. 1999, 40, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstorebrov, I.; Eikevik, T.M.; Petrova, I.; Shokina, Y.; Bantle, M. Description of atmospheric freeze-drying process of organic apples using thermo-physical properties. In Proceedings of the 21st International Drying Symposium (IDS), Valencia, SPAIN, 2018, Sep 11-14; pp. 1703–1710.

- Hua, T.C.; Liu, B.L.; Zhang, H. Freeze-Drying of Pharmaceutical and Food Products. In Freeze-Drying of Pharmaceutical and Food Products; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science Technology and Nutrition; Elsevier Science Bv: Amsterdam, 2010; Volume 198, pp. 1–257. [Google Scholar]

- Gianfrancesco, A.; Smarrito-Menozzi, C.; Niederreiter, G.; Palzer, S. Developing supra-molecular structures during freeze-drying of food. Dry. Technol. 2012, 30, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, A.; Mahn, A.; Huenulaf, P. Drying of apple slices in atmospheric and vacuum freeze dryer. Dry. Technol. 2011, 29, 1076–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.L.; Zhang, M.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Sun, D.F.; Tan, G.W.; Tang, S. Studies on decreasing energy consumption for a freeze-drying process of apple slices. Dry. Technol. 2009, 27, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Guo, Y.M.; Zhang, D.G. Study of the effect of high-pulsed electric field treatment on vacuum freeze-drying of apples. Dry. Technol. 2011, 29, 1714–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, E.; Kamińska-Dwórznicka, A.; Ostrowska-Ligęza, E.; Górska, A.; Wirkowska-Wojdyła, M.; Mańko-Jurkowska, D.; Górska, A.; Bryś, J. Application of different compositions of apple puree gels and drying methods to fabricate snacks of modified structure, storage stability and hygroscopicity. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, M.; Chakraborty, R.; Bhattacharya, P. Optimization of intensification of freeze-drying rate of banana: Combined applications of IR radiation and cryogenic freezing. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2012, 48, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschinis, L.; Salvatori, D.M.; Sosa, N.; Schebor, C. Physical and functional properties of blackberry freeze- and spray-dried powders. Dry. Technol. 2014, 32, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regier, M.; Mayer-Miebach, E.; Behsnilian, D.; Neff, E.; Schuchmann, H.P. Influences of drying and storage of lycopene-rich carrots on the carotenoid content. Dry Technol. 2005, 23, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Bi, J.F.; Chen, Q.Q.; Wu, X.Y.; Li, X.; Qiao, Y.N. Quality improvement of freeze-dried carrots as affected by sugar-osmotic and hot-air pre-treatments. J Food Proc. Pres. 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikolya, L.; Tamás, A. Experimental study of root crops produced using hot air and freeze dehydration. Nonconventional Technologies Review, 2014; XVIII/, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Hawlader, M.N.A.; Perera, C.; Tian, M.; Yeo, K.L. Drying of guava and papaya: Impact of different drying methods. Dry Technol. 2006, 24, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, L.G.; Silveira, A.M.; Freire, J.T. Freeze-drying characteristics of tropical fruits. Dry. Technol. 2006, 24, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiné, R.P.F.; Barroca, M.J. Effect of drying treatments on texture and color of vegetables (pumpkin and green pepper). Food Bioproducts Proc. 2012, 90, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciurzyńska, A.; Popkowicz, P.; Galus, S.; Janowicz, M. Innovative freeze-dried snacks with sodium alginate and fruit pomace (only apple or only chokeberry) obtained within the framework of sustainable production. Molecules 2022, 27, 3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shishehgarha, F.; Makhlouf, J.; Ratti, C. Freeze-drying characteristics of strawberries. Dry. Technol. 2002, 20, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, E.; Jaskulska, A. The effect of freeze-drying on the properties of Polish vegetable soups. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, E.; Ostrowska-Ligęza, E.; Gondek, E. Moisture sorption characteristics and glass transition temperature of apple puree powder. Int. J Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 2515–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlloch-Tinoco, M.; Moraga, G.; Camacho, M.D.; Martínez-Navarrete, N. Combined drying technologies for high-quality kiwifruit powder production. Food Bioproc. Technol. 2013, 6, 3544–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igual, M.; Cebadera, L.; Cámara, R.M.; Agudelo, C.; Martínez-Navarrete, N.; Cámara, M. Novel ingredients based on grapefruit freeze-dried formulations: Nutritional and bioactive value. Foods 2019, 8, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calín-Sánchez, Á.; Kharaghani, A.; Lech, K.; Figiel, A.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A.; Tsotsas, E. Drying kinetics and microstructural and sensory properties of black chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) as affected by drying method. Food Bioproc. Technol. 2015, 8, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simal, S.; Femenia, A.; Garau, M.C.; Rosselló, C. Use of exponential, Page’s and diffusional models to simulate the drying kinetics of kiwi fruit. J. Food Eng. 2005, 66, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karathanos, V.T.; Belessiotis, V.G. Application of a thin-layer equation to drying data of fresh and semi-dried fruits. J. Agri. Eng. Res. 1999, 74, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzouz, S.; Guizani, A.; Jomaa, W.; Belghith, A. Moisture diffusivity and drying kinetic equation of convective drying of grapes. J. Food Eng. 2002, 55, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egas-Astudillo, L.A.; Martínez-Navarrete, N.; Camacho, M.M. Impact of biopolymers added to a grapefruit puree and freeze-drying shelf temperature on process time reduction and product quality. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2020, 120, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzykowski, A.; Dziki, D.; Rudy, S.; Polak, R.; Biernacka, B.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Janiszewska-Turak, E. Effect of air-drying and freeze-drying temperature on the process kinetics and physicochemical characteristics of white mulberry fruits (Morus alba L.). Processes 2023, 11, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikal, M.J.; Shah, S.; Roy, M.L.; Putman, R. The secondary drying stage of freeze drying: drying kinetics as a function of temperature and chamber pressure. Int. J. Pharm. 1990, 60, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasbullah, R.; Putra, N.S. Study on the vacuum pressure and drying time of freeze-drying method to maintain the quality of strawberry (Fragaria virginiana). J. Teknik Pertanian Lampung 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohori, R.; Yamashita, C. Effects of temperature ramp rate during the primary drying process on the properties of amorphous-based lyophilized cake, Part 1: Cake characterization, collapse temperature and drying behavior. J. Drug Deliv. Sci.Technol. 2017, 39, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Temperature, °C | Pressure, Pa | Temperature,°C | Pressure, Pa |

| 0 | 610.0 | -40 | 12.4 |

| -4 | 437.0 | -44 | 8.1 |

| -8 | 310.0 | -48 | 5.0 |

| -12 | 217.0 | -52 | 3.0 |

| -16 | 151.0 | -60 | 1.06 |

| -20 | 124.0 | -64 | 0.61 |

| -24 | 70.0 | -68 | 0.34 |

| -28 | 46.7 | -72 | 0.18 |

| -32 | 30.7 | -76 | 0.10 |

| -36 | 20.2 | -80 | 0.05 |

|

|

| Variants | a | 10−5 x b | 10−3 x k | n | R2 | RMSE |

| t:10, p:63; (1) | 1.005 (0.002)* | −190.0 (0.9) | 1.4 (0.1) | 1.069 (0.012) | 0.9994 | 0.0043 |

| t:10_30, p:63; (2) | 0.996 (0.002) | −12.7 (0.7) | 0.7 (0.0) | 1.214 (0.011) | 0.9995 | 0.0044 |

| t:−25_10_30, p:63; (3) | 0.984 (0.002) | −18.0 (0.9) | 0.2 (0.0) | 1.350 (0.014) | 0.9992 | 0.0042 |

| t:30, p:63; (4) | 1.009 (0.003) | −18.0 (1.0) | 1.6 (0.1) | 1.125 (0.013) | 0.9995 | 0.0044 |

| t:−25_10_30, p:63; (5) | 1.010 (0.002) | −15.0 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.0) | 1.059 (0.010) | 0.9994 | 0.0044 |

| t:−25_10_20_30, p:63; (6) | 1.002 (0.001) | −5.7 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.0) | 1.080 (0.005) | 0.9991 | 0.0010 |

| t:10_30, p:63_103_37; (7) | 1.007 (0.002) | −19.0 (1.0) | 0.8 (0.0) | 1.160 (0.015) | 0.9997 | 0.0051 |

| t:30, p_63_103; (8) | 1.009 (0.003) | −19.5 (1.3) | 1.9 (0.1) | 1.089 (0.015) | 0.9991 | 0.0053 |

| t:−25_10_30, p:63_103; (9) | 0.998 (0.002) | −14.1 (0.7) | 0.3 (0.0) | 1.330 (0.012) | 0.9991 | 0.0045 |

| t:−25_10_30, p:63_165_103; (10) | 0.996 (0.001) | −9.8 (0.4) | 0.06 (0.0) | 1.560 (0.008) | 0.9993 | 0.0010 |

| Drying time, min | Water content, g water/ g d.m.−. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variants | at−10°C in a centre of material |

at−2°C in a centre of material |

at−10°C in a centre of material |

at−2°C in a centre of material |

| t:10, p:63; (1) | 756 | 812 | 0.195 | 0.100 |

| t:10_30, p:63; (2) | 620 | 664 | 0.550 | 0.394 |

| t:−25_10_30, p:63; (3) | 590 | 670 | 1.101 | 0.620 |

| t:30, p:63; (4) | 356 | 458 | 1.401 | 0.701 |

| t:−25_10_30, p:63; (5) | 524 | 638 | 1.809 | 1.211 |

| t:−25_10_20_30, p:63; (6) | 530 | 744 | 1.661 | 0.891 |

| t:10_30, p:63_103_37; (7) | 420 | 554 | 1.681 | 0.874 |

| t:30, p_63_103; (8) | 346 | 404 | 1.428 | 0.998 |

| t:−25_10_30, p:63_103; (9) | 624 | 684 | 0.477 | 0.258 |

| t:−25_10_30, p:63_165_103; (10) | 566 | 696 | 1.232 | 0.594 |

| Variants | Drying time, min | Moisture content, % |

| t:10, p:63; (1) | 930 ± 4a* | 3.46 ± 0.02a |

| t:10_30, p:63; (2) | 855 ± 3b | 3.26 ± 0.06b |

| t:−25_10_30, p:63; (3) | 915 ± 3c | 3.26 ± 0.02b |

| t:30, p:63; (4) | 660 ± 2d | 2.74 ± 0.01c |

| t:−25_10_30, p:63; (5) | 1050 ± 5e | 3.31± 0.08b |

| t:−25_10_20_30, p:63; (6) | 1305 ± 3f | 3.29± 0.21ab |

| t:10_30, p:63_103_37; (7) | 870 ± 4g | 2.74 ± 0.03c |

| t:30, p_63_103; (8) | 735 ± 3h | 2.77 ± 0.08c |

| t:−25_10_30, p:63_103; (9) | 820 ± 4i | 3.13 ± 0.08b |

| t:−25_10_30, p:63_165_103; (10) | 945 ± 3j | 3.55 ± 0.18a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).