1. Introduction

Maintaining an upright posture and balancing this posture during movement requires the use of different muscles and their neuromuscular control. Especially muscles of the lower extremities and the trunk are important in this context [

1,

2]. In various medical conditions, such as Parkinson's disease or multiple sclerosis, this so-called postural control is disturbed [

3,

4]. However, a connection with reduced postural control has been demonstrated not only in chronic diseases, but also, for example, in a lack of strength of the musculoskeletal system in connection with obesity [

5]. Trunk stability represents a performance-determining variable in elite sports [

6] and is considered a key component for the occurrence of chronic nonspecific back pain at the physiological level [

7,

8,

9]. Low Back Pain (LBP) is the most common musculoskeletal condition worldwide, in the minority of cases it can be attributed to a direct specific cause. The costs and burdens of the health problem are expected to continue increasing in the coming decades [

10,

11]. To counteract this development, the early identification of back pain risk patients is of general importance, as well as the use of effective primary preventive measures to avoid LBP. It has been shown that well-developed trunk stability is crucial for this purpose, both in elite sports and in the general population [

6,

12,

13]. Several clinical tests are available to identify a possible unstable trunk, but their validity is controversial [

10,

14]. A commonly used way to reflect the existing level of trunk stability is to measure postural control using stance stability measurements on a force plate [

12,

15]. Quantification of postural control is carried out using different measurement variables. One of these variables is the Center of Pressure (CoP), which can be defined as “the point at which the pressure of the body over the soles of the feet would be if it were concentrated in one spot” [

16]. The distance traveled by the CoP during a measurement allows conclusions about balance control or neuromuscular control. However, the acquisition of trunk stability in stance has several floor or ceiling effects as the CoP is significantly influenced by the performance of the lower extremity [

17,

18]. In addition, degenerative spinal disease can lead to an imbalance in spinal alignment and pathologic pelvic tilt, which also affect CoP [

19,

20]. A possible approach to eliminating interfering variables, such as the lower limb, and quantify trunk stability more accurately represents the recording of postural control in a seated position [

6,

21]. This diagnostic method has the advantage that a bias of the CoP due to physiological performance deficits of the lower extremities, or lower extremity injuries, could be excluded. Therefore, the aim of this work was to compare measurements of postural control in standing and seated position in comparison with back extension strength to find a possible alternative for acquisition trunk stability more precisely. A force plate was used to record the CoP and back extension was determined by a corresponding power machine. The two assessments, sitting and standing position, are comparable from a bio-mechanical perspective. Basically, both variants of the CoP track determination can be regarded as a single-inverted pendulum. The difference in track lengths between the variants represents a linear relationship. With approximately the same pendulum an-gle of the upper body, the shorter pendulum results in a shorter path over the force plate. Due to the larger support surface when sitting, it can be assumed that the angle of deflection in the hip joint is not greater than the angle of deflection in the standing position via the ankle joint [

22,

23]. See also

Figure 1.

The gold standard systems recording the CoP, due to their measurement accuracy, are the force plates of the manufacturers Kistler and Amti [

24,

25]. In this context, an alternative, much lighter and more compact measurement plate, a modified Wii® balance board, was used for validation during the current work. The balance board fulfils the requirements for valid and reliable recording of the CoP trajectory in a standing position [

26] and could also be used in a portable manner, allowing measurements to be taken in an elevated position to record postural control in a seated position.

2. Materials and Methods

In the cross-sectional study 66 subjects (34 female), between 19 and 58 years of age participated. The study received ethic approval and all participants gave their written informed consent. All examinations were carried out in a center certified by the German Olympic Sports Confederation. Volunteers were included only if they answered "no" to all questions of the "Entry Questionnaire for Health Risk Assessment for Athletes" of the German Society for Sports Medicine and Prevention, had no lower extremity injuries in the last 24 months, and reported neither acute nor other back pain within the last three months (PAR-Q-Fragebogen, DGSP) [

27]. Back pain was queried using Korff's Chronic Pain Grade Questionnaire [

28].

The CoP, recorded as the distance traveled by the center of pressure during the measurement in centimeters, of the subjects was measured in a standardized order in two different conditions. First, four trials were performed while standing on one leg, followed by two trials while sitting, both with eyes open.

The measurements were taken in a standing position with one leg. It can be assumed that a greater neuromuscular effort is required to maintain postural control in the one-legged stance compared to the two-legged stance. This should enable better comparability with the seated measurements and the trunk strength measurements in the statistical analysis. Although the lower extremity exerts a significant influence on the CoP deflection in the standing measurements, there is still comparability between the two measurement methods in the study [

44,

45,

46]. Nevertheless, a direct comparison between the two is neither feasible nor recommended, and is not a component of the study.

The order of monopedal stances (left leg, right leg) was randomized. The measuring time per condition was 60 seconds. A rest of one minute was taken between each individual measurement. Standardization was used to avoid any fatigue effects because of decreasing concentration or strength. If signs of increasing instability or loss of balance occurred before the end of this time, these were documented and during the processing of the results, the values were corrected by hand in addition to the auto evaluation.

The autocorrection checks the data records for illogical extreme values caused by brief losses of control. These are smoothed by a partial moving average. If the test person has left the plate during the measurement, the measurements are sorted out manually. After the auto-correction and the manual touch-up, the distance covered by the CoP during the one-minute measurement was obtained in centimeters. The stance position was standardized by means of optical markings on the force plate, which indicated the positioning of the foot. During the readings, the hands were supported at the sides in a standing position and the lifted leg was not allowed to rest on the standing leg. A visual marker was placed at four meters from the measuring position at a height of 1.7 meters. The subjects were asked to visually fix this point during the measurements. All measurement trials were performed barefoot. During the assessments in seated position, the subjects were sitting in an active upright position centered on the balance board. In addition, they were also asked to look at a marker located at a distance of four meters. During the trials the subjects crossed their hands in front of their chest. The legs had to be kept parallel. The height of the test position was adjustable so that the subjects' legs hung freely 50 centimeters above the floor. In addition, attention should be paid to an active upright upper body positioning as still as possible (among other things control of the musculus transversus abdominis) (

Figure 2).

Postural control was measured by means of a balance board, which is based on a technical advancement of a Nintendo Wii® balance board. The Wii® balance board is mechanically loadable up to 150kg. The sensors deliver with the used amplifier from 120kg in the saturation. Operation up to 110kg is no problem for this special arrangement. The Wii® balance board has 4 strain gauge sensors from the factory. The sensors are each designed as a full-measurement bridge. The analog signal processing consists of a differential amplifier and an output amplifier stage. The validation of the conversion was carried out as described in Koltermann et. al 2017 [

29]. The sampling rate was 1 kHz. For the conversion of the analog measurement data into a digital format a converter of the company National Instruments of the type NI USB 6001 with a sampling rate of 14 bit was used as recommended in Koltermann et. al 2022 [

30]. On the software side, the raw data was recorded using LabVIEW 2014 from National Instruments (Austin, Texas). The processing of the measured data from the balance board was done with LabVIEW 2014. Before the calculation of the CoP course, the raw data were filtered using Butterworth 3rd order low pass filter. For the entire cohort, a filter was applied according to the procedure described in [

31]. With this the cutoff frequency was determined. Subsequently, the CoP curves were determined. CoP fluctuation was calculated in the complete transverse plane

. The extension force was recorded concentrically over 10 isokinetic repetitions with a dynamometer (Ferstl GmbH, Hemau, Ger.). The zero point was set at 105° and the measuring speed at 60°/sec as the basic setting. A total of two tests were recorded, with a 60-second pause between them. The sitting position was automatically set for each participant using the associated programme (IsoMed 2000 Back Module from D&R Ferstl GmbH), ensuring that the back was firmly seated in the cushion and the feet were touching the floor plate. Additionally, a belt was placed around the abdomen. Using a corresponding program, the extension curve was registered and the average torque in Newton meters, the maximum torque in Newton meters and the total work in joules has been determined automatically. The extension force was then calculated from the average torque and body weight of the study participant.

Statistical Analysis

The agreement between the acquisition of CoP fluctuation in standing and in seated position on the balance board was assessed by mean difference plots [

32] and Spearman correlation coefficients. The displacement of the CoP was reproduced in centimeters for standing and seated position on the balance board. Therefore, the measurements of the CoP could be directly compared without any further transformation. Assuming a power of 95%, with 5% significance level and a permissible deviation of 1.5 times the expected standard deviation of the measurement methods, a minimum case number of 54 patients was set in advance [

33], determined with the software MedCalc from MedCalc Software Ltd (Ostend, Belgium) [

34]. In principle, expecting five percent background noise with this method, assuming that the error is normally distributed. Therefore, the authors specified in advance that a deviation of up to 10 % could be tolerated for the measurements to be considered consistent.

A Spearman correlation coefficient was obtained for the comparison between CoP fluctuation values (a) in standing and (b) in seated position. Further, a correlation analysis of measurements in standing and seated position and the corresponding extension force measurements in Nm/kg was carried out. Furthermore, we evaluated if the obtained CoP values in seated position could be used to discriminate between subjects with low or high extension force values. We used a mean split on the extension force values (mean 3.32 Nm/kg) and compared the mean values of CoP fluctuation using the Welch t-test. Reproducibility of individual measurements was tested using a two-tailed t-test (TOST) on the individual, raw CoP fluctuation values with an allowed discrepancy of 1 times the expected standard deviation (epsilon) and an alpha error of 10 per cent [

35]. Equivalence was tested using the package “EQUIVNONINF” [

36] for the statistical software R [

37]. Of 66 participants 23 subjects were measured twice at two time points T0 and T1, about 7 days apart, in seated position on the balance board.

3. Results

After verification of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 66 could be included in the study. Participants showed a mean age of 28.59 years (SD 7.8). They were relatively young with an age distribution of 19 to 58 years and a normal mean weight in cross section, but with a rather heterogeneous distribution of their BMI ranging from 15.7 kg/m2 to 43.1 kg/m2 (

Table 1).

In general, the CoP fluctuation in standing position is higher than the CoP fluctuation in seated position (

Table 2), which is consistent with previous study results [

21,

39].

When looking at the individual values in standing and sitting, it is noticeable that the ratio of the mean CoP fluctuation is approximately 2:1 (p < 0.001, t-test). A similar observation was already made by Vette et al. in the context of their evaluation [

38].

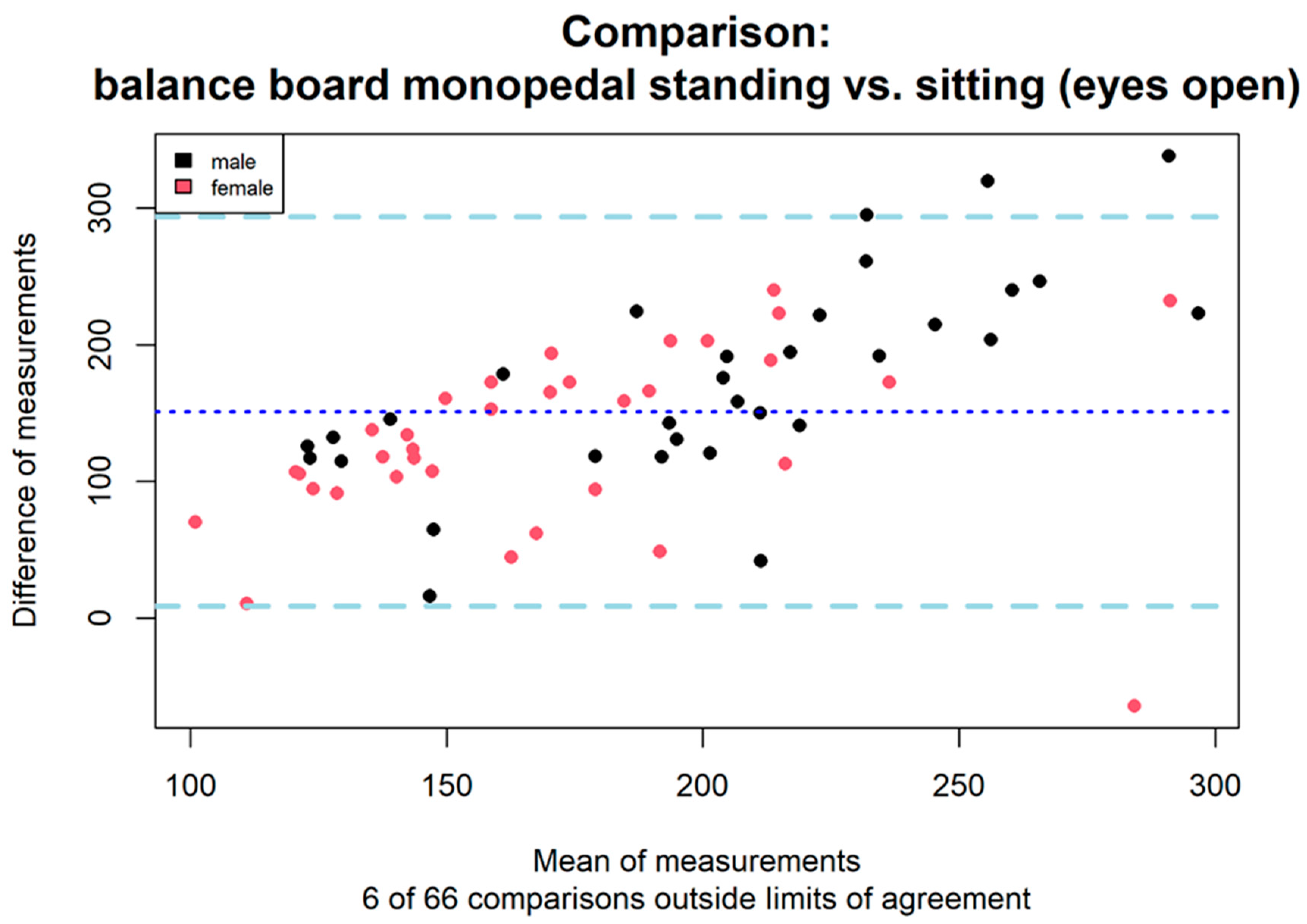

3.1. Comparison of Standing and Seated Position on the Balance Board

To compare measurements in standing and seated position on the balance board, we built mean-difference plots. Mean difference plots showed good agreement between the measurements of both instruments. The deviation was 9.1% between measurements in standing and seated position (

Figure 3). This value is below our predetermined allowed discrepancy of ten percent and thus measurements in standing and seated position showed good agreement. Furthermore, CoP fluctuation measurements in (a) standing and (b) seated position had a positive Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.47. Both CoP fluctuation measurement methods showed a comparable Spearman correlation to additionally obtained extension force measurements measured in Nm/kg (a: 0.24, b: 0.23). Although there was a low correlation between CoP fluctuation in seated position and extension force, this also applies to the CoP fluctuation values in standing position (standard measurement). Subjects with low or high extension force values (splitted by mean extension force value at 3.32 Nm/kg) measured in seated position showed a significant difference in mean values (Welch t-test - mean1: 100.8cm, sd1: 31.5cm, mean2: 122.2cm, sd2: 49.1cm, t = -2.06 (95%-CI -42.3/-0.6), p=0.044).

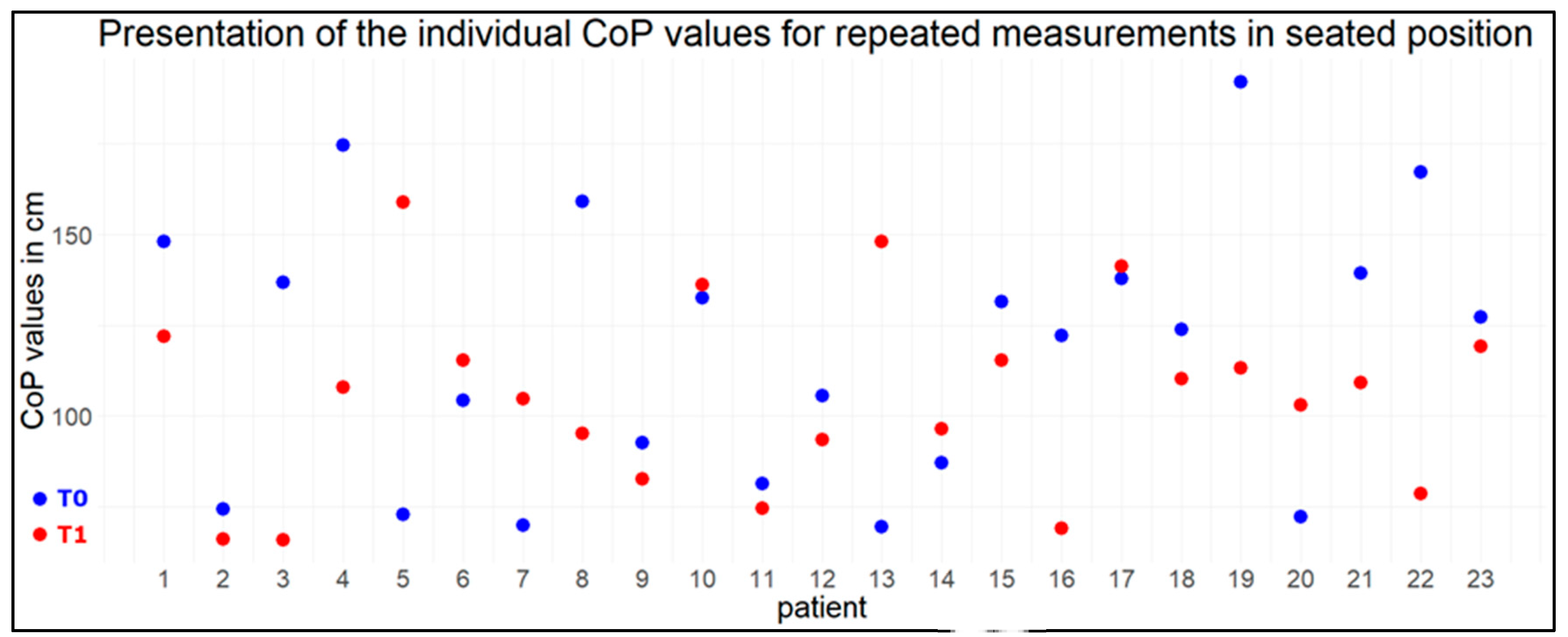

3.2. Reliability of the Measurements with the Balance Board

Equivalence of individual measurements could be demonstrated by TOST test on CoP fluctuation values for subjects in seated position (equivalence bound 58 cm, mean of the differences: 12.87 cm, P<0.001). The null hypothesis that there is an effect large enough to be considered interesting was rejected. Therefore, there is no reason to assume that the measurements at the two time points differ significantly from each other (see also

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

This study compared measurements of CoP fluctuation in standing and seated position on the balance board within healthy adults. Despite the additional stabilization problem in the frontal plane within the one-legged stance measurement, we were able to demonstrate good agreement between both measurement methods by mean-difference plots. Although different back extension forces act in seated position as compared to standing. Mean-Difference analysis showed a tolerated deviation of 9.1%. Subjects with low CoP fluctuation values in standing position had also low CoP fluctuation values measured in seated position and vice versa for high values. However, Spearman correlation was only moderate between both methods (correlation coefficient 0.47). Further, correlation of CoP fluctuation measurements from both methods were comparable in direction and magnitude to measurements of the extension force. CoP fluctuation measurements, obtained in seated position, showed a significant difference in mean values between subjects with low or high extension forces.

Against the background of maintaining an active lifestyle and avoiding immobility, the quantification of postural control, as well as the evaluation of the effect of certain exercises that affect the development of balance ability, are of particular importance, especially for elderly persons, stroke patients, patients with multiple sclerosis, patients LBP and oncological patients after chemotherapy [

3,

40,

41]. Therefore, it is necessary to have an alternative measurement method available, which also allows people with physical limitations to be examined in a safe, low-risk framework. Recording postural control in the seated position could certainly be an alternative to quantifying postural control in the standing position when patients are not physically able to perform the measurements in the standing position.

In addition, the measurement in sitting position enables the direct recording of neuromuscular control on the trunk. Postural adjustments via the ankle, knee and hip strategy can be avoided through this measurement procedure [

42]. This enables more precise detection of neuromuscular deficits in the trunk area during the diagnosis of back pain patients, allowing for more specific adaptation of training and therapy interventions. The interpretation of our results is similar to that of Vette et al., who also investigated standing and sitting in healthy subjects. In that study, 12 healthy young adults were asked to stand (with both feet) and sit on a force plate for 120 seconds, once with eyes closed and once with eyes opened [

38].

In this study, the CoP tracks in seated position were clearly below those in the standing position, as described. This can be explained, among other things, by the biomechanical fact that the smaller distance between the centre of mass in the sitting position and the measuring plate results in less body sway than in the standing position.

The coordination of the trunk, pelvis, and legs is a crucial factor influencing performance, particularly in athletes. The current literature indicates that good trunk stability is associated with a reduction in the risk of injury and an improvement in athletic performance [

47,

48,

49]. The recording of neuromuscular control in a seated position could assist in the identification of weaknesses in trunk control at an early stage or in the assessment of the outcome of trunk-specific interventions. Further studies are required to investigate this assumption.

Initial work [

6,

21,

39] showed, that there are indeed sport-specific profiles of postural control in standing and sitting positions. Barbado et al. [

6] point out, that these sport-specific adaptations are not detectable by non-specific tests.

Furthermore, there should be a critical examination of the implementation of the measurement in seated position. In addition, one could increase the demands on the seated method by having the test persons perform the measurements on an unstable surface, such as a hemisphere, for example, to be able to recognize deficits in neuromuscular control more obviously. Additionally, future work should investigate the effects of targeted trunk stability programs on measures of postural control in the seated position.

Limitations

Possible limitations regarding the measurement setup could be that the test subjects have positioned themselves too far in the front area or in the rear area of the measurement plate and thus the body's center of gravity is not centrally aligned. This could lead to a limited recording and falsification of the CoP fluctuations. Furthermore, it is conceivable that different leverage effects may occur due to the different thigh lengths of the test subjects. For example, long thighs could act as a compensating abutment of the body's center of gravity, so a calmer sitting position and thus a lower CoP fluctuation value could possibly not be due to good trunk stability but could result from better leverage conditions. Furthermore, it is unclear what effect active control of the musculus transversus abdominis has on the resulting CoP fluctuation value. All subjects were instructed to sit upright under control of the musculus transversus abdominis, but this could not be verified. This could also influence the CoP fluctuation value. Furthermore, based on the current measurement setup, it is not possible to verify whether the subjects gained upper body stability primarily by adopting a passive sitting position. In this case, the increased load on the capsular and ligamentous structures leads to a reduction in active neuromuscular holding work. It may be possible to quantify the proportion between passive and active stabilization work by evaluating different CoP frequency spectra [

43]. Further work on this is necessary.

5. Conclusions

Our analysis show that postural control measured in standing and seated position with the balance board is in good agreement to each other. Consequently, the assessment of neuromuscular control in a seated position represents an additional method for the quantification of neuromuscular control, which is not influenced by the lower extremities. This method can be employed for a diverse range of patients who are unable to be measured in a standing position due to impairments. Furthermore, a more precise recording of trunk stability, or the results of trunk-specific interventions, could be possible. This assumptions must be confirmed in future studies with different patient groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.F. and F.H..; methodology, P.F. and F.H. and T.D. ; software, J.J.K..; formal analysis, J.J.K. and T.D.; data curation, J.J.K and F.H. and T.D..; writing—original draft preparation, F.H. and P.F. and J.J.K and T.D.; writing—review and editing, A.C.D. and H.B.; visualization, F.H., and J.J.K. and T.D.; supervision, H.B. and A.C.D.; project administration, A.C.D and H.B.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee at TU Dresden (protocol code: BO-EK-74022021) on 25 March 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- K. Abelin-Genevois, “Sagittal balance of the spine,” Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res., vol. 107, no. 1, p. 102769, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Henry and S. Baudry, “Control of Movement: Age-related changes in leg proprioception: Implications for postural control,” J. Neurophysiol., vol. 122, no. 2, p. 525, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Comber, J. J. Sosnoff, R. Galvin, and S. Coote, “Postural control deficits in people with Multiple Sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Gait and Posture, vol. 61. Elsevier B.V., pp. 445–452, Mar. 01, 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. F. Moretto, F. B. Santinelli, T. Penedo, L. Mochizuki, N. M. Rinaldi, and F. A. Barbieri, “Prolonged Standing Task Affects Adaptability of Postural Control in People With Parkinson’s Disease,” Neurorehabil. Neural Repair, vol. 35, no. 1, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. A. Troebs, “Auswirkungen des langjährigen Lastkraftwagenfahrens auf die posturale Kontrolle.” Frankfurt am Main , 2017, Accessed: Dec. 16, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://d-nb.info/1161799664/34.

- D. Barbado, L. C. Barbado, J. L. L. Elvira, J. H. van Dieën, and F. J. Vera-Garcia, “Sports-related testing protocols are required to reveal trunk stability adaptations in high-level athletes,” Gait Posture, vol. 49, pp. 90–96, 2016.

- H. R. Mokhtarinia, M. A. Sanjari, M. Chehrehrazi, S. Kahrizi, and M. Parnianpour, “Trunk coordination in healthy and chronic nonspecific low back pain subjects during repetitive flexion-extension tasks: Effects of movement asymmetry, velocity and load,” Hum. Mov. Sci., vol. 45, pp. 182–192, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. B. Graham, L. Y. Oikawa, and G. B. Ross, “Comparing the local dynamic stability of trunk movements between varsity athletes with and without non-specific low back pain,” J. Biomech., vol. 47, no. 6, pp. 1459–1464, Apr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- C. Demoulin, J. M. Crielaard, and M. Vanderthommen, “Spinal muscle evaluation in healthy individuals and low-back-pain patients: A literature review,” Joint Bone Spine, vol. 74, no. 1. Joint Bone Spine, pp. 9–13, Jan. 2007. [CrossRef]

- B. J. Coulombe, K. E. Games, E. R. Neil, and L. E. Eberman, “Core stability exercise versus general exercise for chronic low back pain,” J. Athl. Train., vol. 52, no. 1, pp. 71–72, 2017.

- J. Hartvigsen et al., “What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention,” Lancet, vol. 391, no. 10137, pp. 2356–2367, 2018.

- L. F. C. Lemos, C. S. Teixeira, and C. B. Mota, “Low back pain and corporal balance of female brazilian selection canoeing flatwater athletes,” Brazilian J. Kinanthropometry Hum. Perform., vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 457–463, 2010.

- S. H. Jung, U. J. Hwang, S. H. Ahn, H. A. Kim, J. H. Kim, and O. Y. Kwon, “Lumbopelvic motor control function between patients with chronic low back pain and healthy controls: A useful distinguishing tool: The STROBE study,” Medicine (Baltimore)., vol. 99, no. 15, p. e19621, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Brumitt, J. W. Matheson, and E. P. Meira, “Core stabilization exercise prescription, part I: Current concepts in assessment and intervention.,” Sports Health, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 504–9, Nov. 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Oyarzo, C. R. Villagrán, R. E. Silvestre, P. Carpintero, and F. J. Berral, “Postural control and low back pain in elite athletes comparison of static balance in elite athletes with and without low back pain,” J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil., vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 141–146, 2014.

- Ruhe, R. Fejer, and B. Walker, “Center of pressure excursion as a measure of balance performance in patients with non-specific low back pain compared to healthy controls: A systematic review of the literature,” Eur. Spine J., vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 358–368, Mar. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Benaim, D. A. Pérennou, J. Villy, M. Rousseaux, and J. Y. Pelissier, “Validation of a standardized assessment of postural control in stroke patients: The Postural Assessment Scale for Stroke patients (PASS),” Stroke, vol. 30, no. 9, pp. 1862–1868, 1999. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Hale, J. Hertel, and L. C. Olmsted-Kramer, “The effect of a 4-week comprehensive rehabilitation program on postural control and lower extremity function in individuals with chronic ankle instability,” J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther., vol. 37, no. 6, pp. 303–311, 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Le Huec, A. Faundez, D. Dominguez, P. Hoffmeyer, and S. Aunoble, “Evidence showing the relationship between sagittal balance and clinical outcomes in surgical treatment of degenerative spinal diseases: A literature review,” Int. Orthop., vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 87–95, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Ferraris, H. Koller, O. Meier, and A. Hempfing, “Die Bedeutung der sagittalen Balance in der Wirbelsäulenchirurgie,” vol. 1, no. 12, pp. 502–508, 2012, Accessed: Mar. 31, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.mendeley.com/catalogue/7e5baa08-7c14-37b8-8d0a-41f0599afdf6/?utm_source=desktop&utm_medium=1.19.4&utm_campaign=open_catalog&userDocumentId=%7Bc8e23b8f-ae9e-3dfa-bfc4-e4e93cfdea2c%7D.

- M. Roerdink, P. Hlavackova, and N. Vuillerme, “Center-of-pressure regularity as a marker for attentional investment in postural control: A comparison between sitting and standing postures,” Hum. Mov. Sci., vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 203–212, Apr. 2011. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Winter, A. E. Patla, M. Ishac, and W. H. Gage, “Motor mechanisms of balance during quiet standing,” J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol., vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 49–56, 2003. [CrossRef]

- W. H. Gage, D. A. Winter, J. S. Frank, and A. L. Adkin, “Kinematic and kinetic validity of the inverted pendulum model in quiet standing,” Gait Posture, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 124–132, Apr. 2004. [CrossRef]

- L. Donath, R. Roth, L. Zahner, and O. Faude, “Testing single and double limb standing balance performance: Comparison of CoP path length evaluation between two devices,” Gait Posture, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 439–443, Jul. 2012. [CrossRef]

- L. Reinhardt et al., “Comparison of posturographic outcomes between two different devices,” J. Biomech., vol. 86, pp. 218–224, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Leach, M. Mancini, R. J. Peterka, T. L. Hayes, and F. B. Horak, “Validating and calibrating the Nintendo Wii balance board to derive reliable center of pressure measures,” Sensors (Switzerland), vol. 14, no. 10, pp. 18244–18267, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- “PAR-Q-Fragebogen.” https://daten2.verwaltungsportal.de/dateien/seitengenerator/leitlinie_vorsorgeuntersuchung_4.10.2007-anlage-1.pdf (accessed May 30, 2021).

- B. W. Klasen, D. Hallner, C. Schaub, R. Willburger, and M. Hasenbring, “Validation and reliability of the German version of the Chronic Pain Grade questionnaire in primary care back pain patients.,” Psychosoc. Med., vol. 1, p. Doc07, Oct. 2004, Accessed: May 30, 2021. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19742049.

- J. J. Koltermann, M. Gerber, H. Beck, and M. Beck, “Validation of the HUMAC Balance System in Comparison with Conventional Force Plates,” Technol. 2017, Vol. 5, Page 44, vol. 5, no. 3, p. 44, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Koltermann and M. Gerber, “Quantification of the Dependence of the Measurement Error on the Quantization of the A/D Converter for Center of Pressure Measurements,” Biomech. 2022, Vol. 2, Pages 309-318, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 309–318, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Koltermann, M. Gerber, H. Beck, and M. Beck, “Validation of Different Filters for Center of Pressure Measurements by a Cross-Section Study,” Technologies, vol. 7, no. 4, p. 68, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Bland and D. G. Altman, “Measuring agreement in method comparison studies,” Stat. Methods Med. Res., vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 135–160, Apr. 1999. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Lu, W. H. Zhong, Y. X. Liu, H. Z. Miao, Y. C. Li, and M. H. Ji, “Sample Size for Assessing Agreement between Two Methods of Measurement by Bland-Altman Method,” Int. J. Biostat., vol. 12, no. 2, Nov. 2016. [CrossRef]

- “MedCalc statistical software - free trial available.” https://www.medcalc.org/ (accessed Mar. 27, 2022).

- D. Lakens, “Equivalence Tests: A Practical Primer for t Tests, Correlations, and Meta-Analyses,” Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci., vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 355–362, May 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Wellek and P. Z. Maintainer, “Package ‘EQUIVNONINF’ Type Package Title Testing for Equivalence and Noninferiority,” 2017.

- “R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing,” Accessed: Dec. 31, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.gnu.org/copyleft/gpl.html.

- H. Vette, K. Masani, V. Sin, and M. R. Popovic, “Posturographic measures in healthy young adults during quiet sitting in comparison with quiet standing,” Med. Eng. Phys., vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 32–38, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- N. Vuillerme and V. Nougier, “Attentional demand for regulating postural sway: The effect of expertise in gymnastics,” Brain Res. Bull., vol. 63, no. 2, pp. 161–165, Mar. 2004. [CrossRef]

- U. Bahcaci and I. Demirbuken, “Effects of chemotherapy process on postural balance control in patients with breast cancer,” Indian J. Cancer, vol. 56, no. 1, pp. 50–53, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Müller et al., “Out of balance – Postural control in cancer patients before and after neurotoxic chemotherapy,” Gait Posture, vol. 77, pp. 156–163, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. W. Mok, S. G. Brauer, and P. W. Hodges, “Hip strategy for balance control in quiet standing is reduced in people with low back pain.,” Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976)., vol. 29, no. 6, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Bizid R, Jully JL, Gonzalez G, François Y, Dupui P, Paillard T. Effects of fatigue induced by neuromuscular electrical stimulation on postural control. J Sci Med Sport. 2009;12(1):60-66. [CrossRef]

- N. Genthon, N. Vuillerme, J. P. Monnet, C. Petit, and P. Rougier, “Biomechanical assessment of the sitting posture maintenance in patients with stroke,” Clin. Biomech., vol. 22, no. 9, pp. 1024–1029, Nov. 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. Grangeon, C. Gauthier, C. Duclos, J. F. Lemay, and D. Gagnon, “Unsupported eyes closed sitting and quiet standing share postural control strategies in healthy individuals,” Motor Control, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 10–24, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Rogério de Oliveira M, Fabrin LF, Wilson de Oliveira Gil A; et al., “Acute effect of core stability and sensory-motor exercises on postural control during sitting and standing positions in young adults,” J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2021 Oct:28:98-103. [CrossRef]

- G. O. Glofcheskie and S. H. M. Brown, “Athletic background is related to superior trunk proprioceptive ability, postural control, and neuromuscular responses to sudden perturbations,” Hum. Mov. Sci., vol. 52, pp. 74–83, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Imai, K. Kaneoka, Y. Okubo, and H. Shiraki, “EFFECTS OF TWO TYPES OF TRUNK EXERCISES ON BALANCE AND ATHLETIC PERFORMANCE IN YOUTH SOCCER PLAYERS,” Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther., vol. 9, no. 1, p. 47, Feb. 2014, Accessed: May 01, 2024. [Online]. Available: /pmc/articles/PMC3924608/.

- E. Zemková and L. Zapletalová, “The Role of Neuromuscular Control of Postural and Core Stability in Functional Movement and Athlete Performance,” Front. Physiol., vol. 13, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).