Submitted:

08 August 2024

Posted:

08 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Isolates and Patients

2.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing and Phenotypic Tests for Detection of ESBLs, Plasmid-Mediated AmpC β-Lactamases and Carbapenemases

2.3. Molecular Detection of Resistance Genes

2.4. Detection of Resistance Genes by Inter-Array Kit CarbaResist

2.5. Conjugation

2.6. Characterization of Plasmids

2.7. String Test

2.8. Genotyping of the Isolates

3. Results

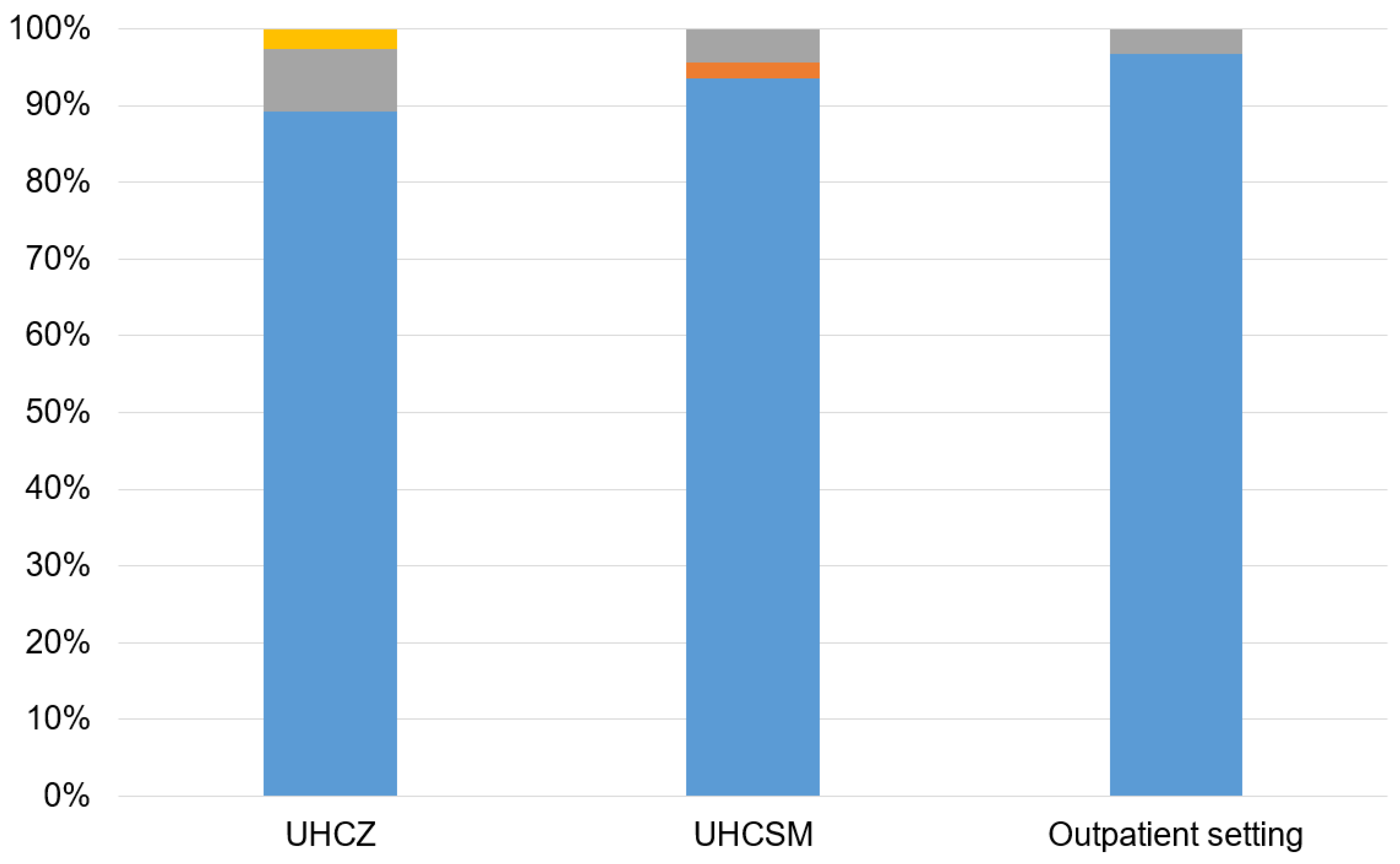

3.1. Bacterial Isolates and Patients

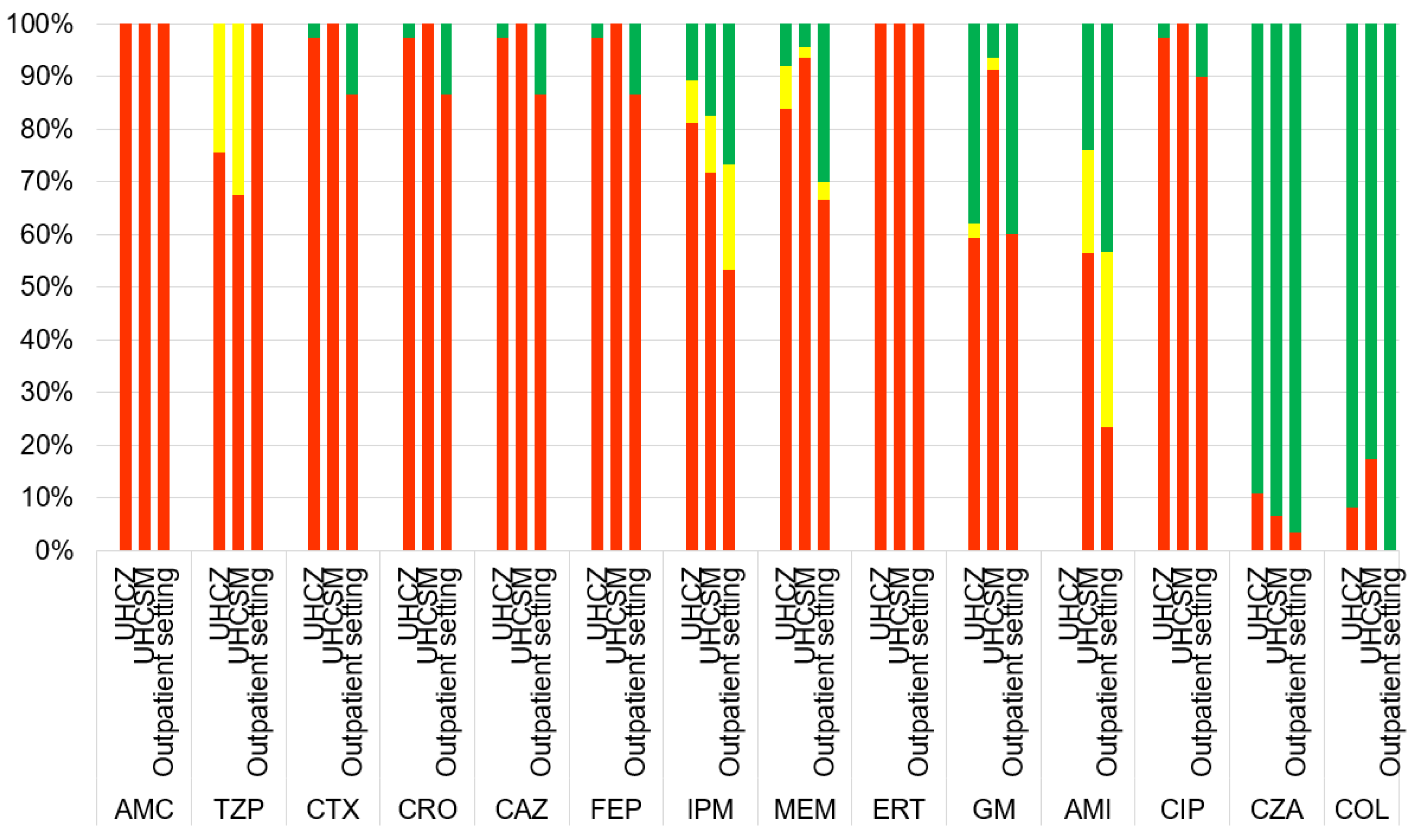

3.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Phenotypic Tests for β-Lactamases

3.3. Molecular Detection of Resistance Genes

3.4. Detection of Resistance Genes by Inter-Array Kit CarbaResist

3.5. Transfer of Resistance Determinants

3.6. Plasmid Characterization

3.7. String Test

3.8. Genotyping

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical permission

References

- Kurra, N.; Woodard, P.I.; Gandrakota, N.; Gandhi, H.; Polisetty, S.R.; Ang, S.P.; Patel, K.P.; Chitimalla, V.; Ali Baig, M.M.; Samudrala, G.O. Opportunistic Infections in COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus. 2022, 31, e23687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniadou, A.; Kontopidou, F.; Poulakou, G.; Koratzanis, E.; Galani, I.; Papadomichelakis, E.; Kopterides, P.; Souli, M.; Armaganidis, A.; Giamarellou, H. Colistin-resistant isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae emerging in intensive care unit patients: First report of a multiclonal cluster. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007, 59, 786–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, R.M.; Bachman, M.A. Colonization, Infection, and the Accessory Genome of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clegg, S.; Murphy, C.N. Epidemiology and Virulence of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microbiol Spectr. 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, B.; Xiao, X.; Zhout, X.; Zhang, I. Clinical and molecular characteristics of multi-clone carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent isolates in tertiary hospital in Bejing, China. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 37, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kliebe, C.; Nies, B.A.; Meyer, J.F.; Tolxdorff-Neutzling, R.M.; Wiedemann, B. Evolution of plasmid-coded resistance to broad-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985, 28, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterson, D.L.; Bonomo, R.A. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases: A clinical update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005, 18, 657–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacoby, G.A.; Munoz-Price, L.S. The new β-lactamases. N Engl J Med. 2005, 352, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossolini, G.M.; D’Andrea, M.M.; Mugnaioli, C. The spread of CTX-M-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Infect. Erratum in: Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008, (Suppl. 5), 21-24. 2008, 14 (Suppl. S1), 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, R. Growing group of extended-spectrum β-lactamases: The CTX-M enzymes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.B.; Park, C.H.; Kim, C.J.; Kim, E.C.; Jacoby, G.A.; Hooper, D.C. Prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants over a 9-year period. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedenic, B.; Zagar, Z. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae from Zagreb, Croatia. J Chemother. 1998, 10, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedenić, B.; Randegger, C.C.; Stobberingh, E.; Hächler, H. Molecular epidemiology of extended-spectrum β-lactamases from Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated in Zagreb, Croatia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001, 20, 505–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vranić-Ladavac, M.; Bosnjak, Z.; Beader, N.; Barisic, N.; Kalenic, S.; Bedenić, B. Clonal spread of CTX-M-15-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Croatian hospital. J Med Microbiol. 2010, 59, 1069–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacoby, G.A. AmpC β-lactamases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 22, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L.; Pitout, J.D.; Nordmann, P. Carbapenemases: Molecular diversity and clinical consequences. Future Microbiol. 2007, 2, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitout, J.D.D.; Peirano, G.; Kock, M.M.; Strydom, K.A.; Matsumura, Y. The Global Ascendency of OXA-48-Type Carbapenemases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019, 33, e00102-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albiger, B.; Glasner, C.; Struelens, M.J.; Grundmann, H.; Monnet, D.L. European Survey of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae (EuSCAPE) working group. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Europe: Assessment by national experts from 38 countries, May 2015. Euro Surveill. 2015, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poirel, L.; Heritier, C.; Tolun, V.; Nordmann, P. Emergence of oxacillinases-mediated resistance to imipenem in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazik, H.; Aydin, S.; Albayrak, R.; Bilgi, E.A.; Yildiz, I.; Kuvat, N.; Kelesoglu, F.M.; Kelesoglu, F.M.; Pakaştiçali, N.; Yilmaz, F.; et al. Detection and spread of OXA-48-producing Klebsiella oxytoca isolates in Istanbul, Turkey. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2014, 5, 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Carrer, A.; Poirel, L.; Eraksoy, H.; Cagatay, A.; Badur, S.; Nordmann, P. Spread of OXA-48-positive carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in Istanbul, Turkey. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 2950–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuzon, G.; Quanich, J.; Gondret, R.; Naas, T.; Nordmann, P. Outbreak of OXA-48 positive carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in France. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 2420–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeifer, Y.; Schlatterrer, K.; Engelmann, E.; Schiller, R.A.; Frangenberg, H.D.; Holfelder, M.; Witte, W.; Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. Emergence of OXA-48-type carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in German Hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 2125–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poirel, L.; Naas, T.; Nordmann, P. Diversity, epidemiology, and genetics of class D β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.R.; Lee, J.H.; Park, K.S.; Kim, Y.B.; Jeong, B.C.; Lee, S.H. Global Dissemination of Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: Epidemiology, Genetic Context, Treatment Options, and Detection Methods. Front Microbiol. 2016, 7, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubert, D.; Naas, T.; Héritier, C.; Poirel, L.; Nordmann, P. Functional characterization of IS1999, an IS4 family element involved in mobilization and expression of β-lactam resistance genes. J Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 6506–6514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzariol, A.; Bošnjak, Z.; Ballarini, P.; Budimir, A.; Bedenić, B.; Kalenić, S.; Cornaglia, G. NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, Croatia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012, 18, 532–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedenić, B.; Mazzariol, A.; Plečko, V.; Bošnjak, Z.; Barl, P.; Vraneš, J.; Cornaglia, G. First report of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Croatia. J Chemother. 2012, 24, 237–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zujić-Atalić, V.; Bedenić, B.; Kocsis, E.; Mazzariol, A.; Sardelić, S.; Barišić, M.; Plečko, V.; Bošnjak, Z.; Mijač, M.; Jajić, I.; et al. Diversity of carbapenemases in clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae in Croatia-the resu,lts of the multicenter study. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2014, 20, O894–O903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedenić, B.; Sardelić, S.; Luxner, J.; Bošnjak, Z.; Varda-Brkić, D.; Lukić-Grlić, A.; Mareković, I.; Frančula-Zaninović, S.; Krilanović, M.; Šijak, D.; et al. Molecular characterization of class B carbapenemases in advanced stage of dissemination and emergence of class D carbapenemases in Enterobacteriaceae from Croatia. Infect Genetic Evol. 2016, 43, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedenić, B.; Slade, M.; Žele-Starčević, L.; Sardelić, S.; Vranić-Ladavac, M.; Benčić, A.; Zujić Atalić, V.; Bogdan, M.; Bubonja-Šonje, M.; Tomić-Paradžik, M.; et al. Epidemic spread of OXA-48 β-lactamase in Croatia. J Med Microbiol. 2018, 67, 1031–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelić, M.; Škrlin, J.; Bejuk, D.; Košćak, I.; Butić, I.; Gužvinec, M.; Tambić-Andrašević, A. Characterization of Isolates Associated with Emergence of OXA-48-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Croatia. Microb Drug Resist. 2018, 24, 973–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuto, S.; Bedenić, B.; Likić, S.; Kibel, S.; Anušić, M.; Tičić, V.; Zarfel, G.; Grisold, A.; Barišić, I.; Vraneš, J. Diffusion of OXA-48 carbapenemase among urinary isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae in non-hospitalized elderly patients. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robicsek, A.; Jacoby, G.A.; Hooper, D.C. The worldwide emergence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006, 6, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carattoli, A.; Seiffert, S.N.; Schwendener, S.; Perreten, V.; Endimiani, A. Differentiation of IncL and IncM plasmids associated with the spread of clinically relevant antimicrobial resistance. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannateli, A.; Giani, T.; D’Andrea, M.M.; Di Pilato, V.; Arena, F.; Conte, V.; Tryfinopoulou, K.; Vatopoulos, A.; Rossolini, G.M.; COLGRIT Study Group. MgrB inactivation is a common mechanism of colistin resistance in KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae of clinical origin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 5696–5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Onofrio, V.; Conzemius, R.; Varda-Brkić, D.; Bogdan, M.; Grisold, A.; Gyssens, I.C.; Barišić, I. Epidemiology of colistin-resistant, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter baumannii in Croatia. Infect Genet Evol. 2020, 81, 104263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, F.; Li, S.; Wang, R.; Wang, H. High Prevalence of Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection in China: Geographic Distribution, Clinical Characteristics, and Antimicrobial Resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 6115–6120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, D.; Dong, N.; Zheng, Z.; Lin, D.; Huang, M.; Wang, L.; Chan, E.W.; Shu, L.; Yu, J.; Zhang, R.; et al. A fatal outbreak of ST11 carbapenem-resistant hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Chinese hospital: A molecular epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018, 18, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 12. 2022. Available online: http://www.eucast.org (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Clinical Laboratory Standard Institution. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 28th ed.; Approved Standard M100-S22; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Magiorakos, A.P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2002, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarlier, V.; Nicolas, M.H.; Fournier, G.; Philippon, A. Extended broad-spectrum beta-lactamases conferring transferable resistance to newer beta-lactam agents in Enterobacteriaceae: Hospital prevalence and susceptibility patterns. Rev Infect Dis. 1988, 10, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krilanović, M.; Tomić-Paradžik, M.; Meštrović, T.; Beader, N.; Herljević, Z.; Conzemius, R.; Barišić, I.; Vraneš, J.; Elveđi-Gašparović, V.; Bedenić, B.E. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases and plasmid diversity in urinary isolates of Escherichia coli in Croatia: A nation-wide, multicentric, retrospective study. Folia Microbiol (Praha). 2020, 65, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, J.A.; Moland, E.S.; Thomson, K.S. AmpC disk test for detection of plasmid-mediated AmpC beta-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae lacking chromosomal AmpC β-lactamases. J Clin Microbiol. 2005, 43, 3110–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amjad, A.; Mirza, I.; Abbasi, S.; Farwa, U.; Malik, N.; Zia, F. Modified Hodge test: A simple and effective test for detection of carbapenemase production. Iran J Microbiol. 2011, 3, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Lim, Y.S.; Yong, D.; Yum, J.H.; Chong, Y. Evaluation of the Hodge test and the imipenem-EDTA-double-disk synergy test for differentiating metallo-β-lactamase-producing isolates of Pseudomonas spp. and Acinetobacter spp. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 4623–4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Zwaluw, K.; De Haan, A.; Pluister, G.N.; Bootsma, H.J.; de Neeling, A.J. The Carbapenem Inactivation Method (CIM), a simple and low-cost alternative for the carba NP test to assess phenotypic carbapenemase activity in Gram-negative rods. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, J.W.; Chibabhai, V. Evaluation of the RESIST-4 O.K.N.V immunochromatographic lateral flow assay for the rapid detection of OXA-48, KPC, NDM and VIM carbapenemases from cultured isolates. Access Microbiol. 2019, 1, e000031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlet, G.; Brami, G.; Decre, D.; Flippo, A.; Gaillot, O.; Lagrange, P.H.; Philippon, A. Molecular characterization by PCR restriction fragment polymorphism of TEM β-lactamases. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1995, 134, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nüesch-Inderbinen, M.T.; Hächler, H.; Kayser, F.H. Detection of genes coding for extended-spectrum SHV β-lactamases in clinical isolates by a molecular genetic method, and comparison with the E test. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1996, 15, 398–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, N.; Ward, M.E.; Kaufmann, M.E.; Turton, J.; Fagan, E.J.; James, D.; Johnson, A.P.; Pike, R.; Warner, M.; Cheasty, T.; et al. Community and hospital spread of Escherichia coli producing CTX-M extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the UK. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004, 54, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, N.; Fagan, E.J.; Ellington, M.J. Multiplex PCR for rapid detection of genes encoding CTX-M extended-spectrum β-lactamases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 57, 154–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Perez, F.J.; Hanson, N.D. Detection of plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamase genes in clinical isolates by using multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 2153–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L.; Walsh, T.R.; Cuveiller, V.; Nordman, P. Multiplex PCR for detection of acquired carbapenemases genes. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 70, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.; Walsh, T.R.; Yi, L.X.; Zhang, R.; Spencer, J.; Tian, G.; Dong, B.; Huang, X.; Yu, L.F.; et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: A microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016, 16, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianni, T.; Conte, V.; Di Pilato, V.; Aschbacher, R.; Weber, C.; Rossolini, G.M.L. Escherichia coli from Italy producing OXA-48 carbapenemase encoded by a novel Tn1999 Transposon derivative. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 2211–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladin, M.; Cao, V.T.B.; Lambert, T.; Donay, J.L.; Hermann, J.; Ould-Hocine, L. Diversity of CTX-M β-lactamases and their promoter regions from Enterobacteriaceae isolated in three Parisian hospitals. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2002, 209, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwell, L.P.; Falkow, S. The characterization of R plasmids and the detection of plasmid-specified genes. In Antibiotics in Laboratory Medicine, 2nd ed.; Lorian, V., Ed.; Williams and Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1986; pp. 683–721. [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli, A.; Bertini, A.; Villa, L.; Falbo, V.; Hopkins, K.L.; Threfall, E.J. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J Microbiol Methods. 2005, 63, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diancourt, L.; Passet, V.; Verhoef, J.; Grimont, P.A.; Brisse, S. Multilocus sequence typing of Klebsiella pneumoniae nosocomial isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2005, 43, 4178–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livermore, D.M.; Walsh, T.R.; Toleman, M.; Woodford, N. Balkan NDM-1: Escape or transplant? Lancet Infect Dis. 2011, 11, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedenić, B.; Luxner, J.; Car, H.; Sardelić, S.; Bogdan, M.; Varda-Brkić, D.; Šuto, S.; Grisold, A.; Beader, N.; Zarfel, G. Emergence and Spread of Enterobacterales with Multiple Carbapenemases after COVID-19 Pandemic. Pathogens. 2023, 12, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopotsa, K.; Osei Sekyere, J.; Mbelle, N.M. Plasmid evolution in carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: A review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2019, 1457, 61–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedenić, B.; Sardelić, S.; Bogdanić, M.; Zarfel, G.; Beader, N.; Šuto, S.; Krilanović, M.; Vraneš, J. Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) in urinary infection isolates. Arch Microbiol 2021, 4, 1825–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, C.; Chang, Y.F.; Chen, W.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, F.; Zhang, L. blaNDM-5 carried by a hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae with sequence type 29. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019, 8, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achille, G.; Nunzi, I.; Fioriti, S.; Cirioni, O.; Brescini, L.; Giacometti, A.; Teodori, L.; Brenciani, A.; Giovanetti, E.; Mingoia, M.; et al. Clonal dissemination of Klebsiella pneumoniae carrying blaOXA-48 gene in, a central Italy hospital. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2024, 18, S2213–S7165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedenić, B.; Bratić, V.; Mihaljević, S.; Lukić, A.; Vidović, K.; Reiner, K.; Schöenthaler, S.; Barišić, I.; Zarfel, G.; Grisold, A. Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria in a COVID-19 Hospital in Zagreb. Pathogens 2023, 12, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | UHCZ | UHCSM | Community isolates |

| Number of isolates | 37 | 46 | 30 |

| Number of ESBL positive isolates | 91.9% (34/37) | 93.5% (43/46) | 83.3% (25/30) |

| Number of AmpC positive isolates | 0.0% (0/37) | 0.0% (0/46) | 0.0% (0/30) |

| HODGE test | 73.0% (27/37) | 76.1% (35/46) | 100.0% (30/30) |

| CIM test | 86.4% (32/37) | 76.1% (35/46) | 100.0% (30/30) |

| AMC -R | 100.0% (37/37) | 100.0% (46/46) | 100.0% (30/30) |

| TZP-R | 100.0% (37/37) | 67.4% (31/46) | 100.0% (30/30) |

| CXM-R | 97.3% (36/37) | 100.0% (46/46) | 86.7% (26/30) |

| CAZ-R | 97.3% (36/37) | 100.0% (46/46) | 86.7% (26/30) |

| CTX-R | 97.3% (36/37) | 100.0% (46/46) | 86.7% (26/30) |

| CRO-R | 97.3% (36/37) | 100.0% (46/46) | 86.7% (26/30) |

| FEP-R | 97.3% (36/37) | 100.0% (46/46) | 86.7% (26/30) |

| IMI-R | 75.7% (28/37) | 71.7% (33/46) | 53.3% (16/30) |

| MEM-R | 78.4% (29/37) | 93.5% (43/46) | 66.7% (20/30) |

| ERT-R | 100.0% (37/37) | 100.0% (46/46) | 100.0% (30/30) |

| GM-R | 62.1% (23/37) | 89.1% (41/46) | 56.7% (17/30) |

| AMI-R | 32.4% (12/37) | 56.5% (26/46) | 16.7% (5/30) |

| CIP-R | 94.6% (35/37) | 100.0% (46/46) | 80.0% (24/30) |

| COL-R | 8.1% (3/37) | 15.2% (7/46) | 0.0% (0/30) |

| CZA-R | 8.1% (3/37) | 17.4% (8/46) | 0.0% (0/30) |

| blaCTX-M | 91.9% (34/37) | 93.4% (43/46) | 83.3% (25/30) |

| blaTEM | 5.4% (2/37) | 15.2% (7/46) | 0.0% (0/30) |

| blaoxa-48 | 91.9% (34/37) | 93.4% (43/46) | 96.7% (29/30) |

| blaKPC | 0.0% (0/37) | 2.2% (1/46) | 0.0% (0/30) |

| BlaNDM | 10.8% (4/37) | 4.3% (2/46) | 3.3% (1/30) |

| String test | 2.7% (1/37) | 4.3% (2/46) | 0.0% (0/30) |

| Inc L plasmid | 48.6% (18/37) | 43.5% (20/46) | 33.3% (10/30) |

| IncY plasmid | 2.7% (1/37) | 8.7% (4/46) | 0.0% (0/30) |

| IncW plasmid | 5.4% (2/37) | 17.4% (8/46) | 0.0% (0/30) |

| IncP plasmid | 0.0% (0/37) | 2.2% (1/46) | 0.0% (0/30) |

| Isolate and protocol number | Centre | β-lactam | AG | SUL | THR | efflux |

|

K. pneumoniae 36 (47168) |

UHCSM |

blaCTX-M-15 blaSHV blaOXA-1 blaOXA-48 |

aac(6’)-Ib | dfrA14 | oqxA, oqxB | |

|

K. pneumoniae 38 (39118) |

UHCSM |

blaCTX-M-15 blaSHV bla0XA-48 |

aac(6’)-Ib | dfrA14 | oqxA, oqxB | |

|

K. pneumoniae 39 (23199) |

UHCSM |

blaCTX-M-15 blaSHV blaOXA-1 blaOXA-48 |

aac(6’)-Ib | dfrA14 | oqxA, oqxB | |

|

K. pneumoniae 40 (152854) |

UHCZ |

blaCTX-M-15 blaSHV blaOXA-1 blaNDM |

aac(6’)-Ib aphA |

sul1 | oqxA, |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).