Submitted:

07 August 2024

Posted:

08 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Diabetic neuropathy and its complications in the sole of the foot.

- The magnitude of the forces reaching the foot.

- The distance walked that triggers a state of tissue inflammation.

2. Materials and Methods

Protocol and identification of the problem

Research question

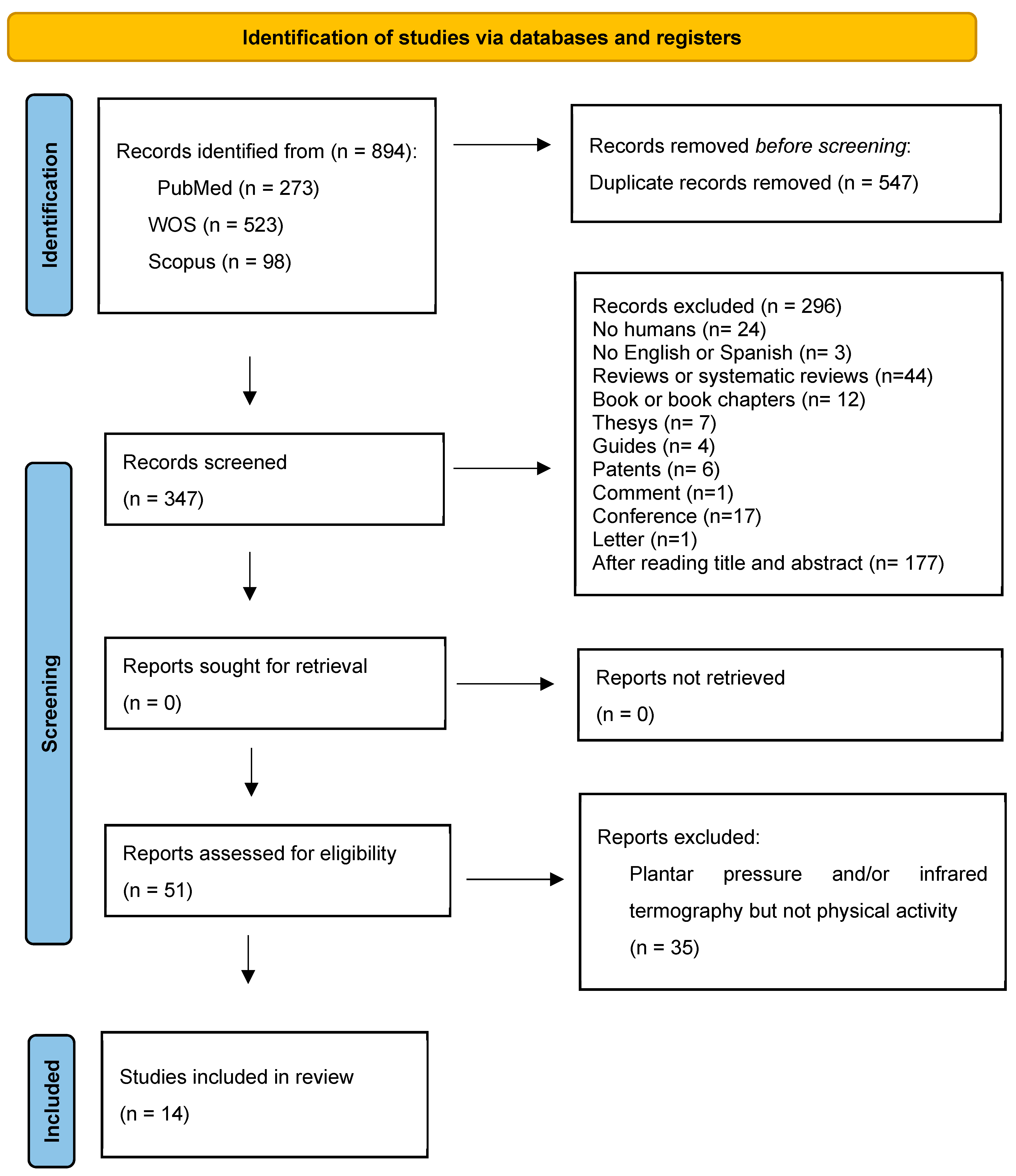

Data collection

Assessment of study methodology and quality

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boulton AJ, Vileikyte L, Ragnarson-Tennvall, G & Apelqvist J. The global burden of diabetic foot disease. Lancet. 2005, 366(9498): 1719-1724. [CrossRef]

- Kumari MJSJ, Jagdish, S. How to prevent amputation in diabetic patients. Int J Nurs Educ. 2014, 6: 40-44.

- Volmer-Thole M, Lobmann R. Neuropathy and diabetic foot syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17 (6): 917. [CrossRef]

- Brand PW. Tenderizing the foot. Foot & Ankle International. 2003, 24(6):457-461. [CrossRef]

- Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Wunderlich RP, Tredwell J Boulton, AJ. Predictive value of foot pressure assessment as part of a population-based diabetes disease management program. Diabetes Care. 2003, 26 (4): 1069-1073. [CrossRef]

- Yavuz M. American Society of Biomechanics Clinical Biomechanics Award 2012: plantar shear stress distributions in diabetic patients with and without neuropathy. Clinical Biomechanics. 2014, 29 (2): 223-229. [CrossRef]

- Yavuz M, Botek G, Davis BL. Plantar shear stress distributions: Comparing actual and predicted frictional forces at the foot–ground interface. Journal of Biomechanics. 2007; 40 (13): 3045-3049. [CrossRef]

- Macdonald A, Petrova N, Ainarkar S, Allen J, Plassmann P, Whittam A, Bevans, J, Ring F, Kluwe B, Simpson R, Rogers L, Machin G & Edmonds M. Thermal symmetry of healthy feet: a precursor to a thermal study of diabetic feet prior to skin breakdown. Physiological measurement. 2016, 38 (1): 33-44. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Contreras D, Peregrina-Barreto H, Rangel-Magdaleno J, González-Bernal JA, & Altamirano-Robles L. A quantitative index for classification of plantar thermal changes in the diabetic foot. Infrared Physics & Technology. 2017, 81: 242-249. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong DG, Holtz-Neiderer K, Wendel C, Mohler MJ, Kimbriel HR, & Lavery LA. Skin temperature monitoring reduces the risk for diabetic foot ulceration in high-risk patients. Am J Med. 2007, 120 (12): 1042-1046. [CrossRef]

- Lung, CW, Wu, FL, Liao, F., Pu, F., Fan, Y., and Jan, YK. Emerging technologies for the prevention and management of diabetic foot ulcers. J Tissue Viability. 2020, 29 (2), 61-68. [CrossRef]

- Hall, M, Shurr, DG, Zimmerman, MB, & Saltzman, CL. Plantar foot surface temperatures with use of insoles. The Iowa orthopedic journal. 2004; 24,72-75. PMC1888418 341.

- Burnfield JM, Few CD, Mohamed OS, & Perry J. The influence of walking speed and footwear on plantar pressures in older adults. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2004, 19 (1): 78-84. [CrossRef]

- Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, Bossuyt, PM, Boutron, I., Hoffmann, TC, Mulrow, CD ... and Moher, D. PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guide for the publication of systematic reviews. Spanish Journal of Cardiology. 2021, 74 (9), 790-799. [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, AP, De Vet, HC, De Bie, RA, Kessels, AG, Boers, M, Bouter, LM, & Knipschild, PG. The Deplphilist: a criteria list for quality assessment of randomized clinical trials for conducting systematic reviews developed by Delphi consensus. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1998; 51 (12), 1235-1241. [CrossRef]

- Albanese, E.; Bütikofer, L.; Armijo-Olivo, S.; Ha, C.; Egger, M. Construct validity of the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) quality scale for randomized trials: Item response theory and factor analyses. Res. Synth. Methods. 2020, 11, 227–236. [CrossRef]

- Escala PEDro—PEDro. Available online: https://pedro.org.au/spanish/resources/pedro-scale/ (accessed on).

- Maluf, KS, Morley Jr, RE, Richter, EJ, Klaesner, JW, & Mueller, MJ. Monitoring in-shoe plantar pressures, temperature, and humidity: reliability and validity of measures from a portable device. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2001, 82 (8), 1119-1127. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, PN, Cooper, G., Weightman, A., Hodson-Tole, E., & Reeves, ND. Walking cadence affects rate of plantar foot temperature change but not final temperature in younger and older adults. Gait & Posture. 2017, 52, 272-279. [CrossRef]

- Li, P. L., Yick, K. L., Yip, J., & Ng, S. P. Influence of Upper Footwear Material Properties on Foot Skin Temperature, Humidity and Perceived Comfort of Older Individuals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022, 19(17), 10861.

- Nemati, H., & Naemi, R. An Analytical Model to Predict Foot Sole Temperature: Implications to Insole Design for Physical Activity in Sport and Exercise. Applied Sciences. 2022, 12(13), 370 6806.

- Niemann, U., Spiliopoulou, M., Malanowski, J., Kellersmann, J., Szczepanski, T., Klose, S., Dedonaki, E., Walter, I., Ming, A., and Mertens, P.R. Plantar temperatures in stance position: comparative study with healthy volunteers and diabetes patients diagnosed with sensoric neuropathy. EBioMedicine. 2020, 54, 102712. [CrossRef]

- Carbonell, L., Quesada, J. I. P., Retorta, P., Benimeli, M., De Anda, R. M. C. O., Palmer, R. S., ... & Macián-Romero, C. Thermographic quantitative variables for diabetic foot assessment: preliminary results. Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering: Imaging & Visualization. 2018, 7(5-6):1-7. [CrossRef]

- Di Benedetto, M., Huston, CW, Sharp, MW, and Jones, B. Regional hypothermia in response to minor injury. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 1996, 75 (4), 270-277.

- Di Benedetto, M., Yoshida, M., Sharp, M., & Jones, B. Foot evaluation by infrared imaging. Military medicine.2002, 167 (5), 384-392. [CrossRef]

- Yavuz M, Brem RW, Davis BL, Patel J, Osbourne A, Matassini MR, Wood DA, and Nwokolo IO. Temperature as a predictive tool for planting triaxial loading. Journal of Biomechanics. 2014, 47 (15), 3767-3770. [CrossRef]

- Priego Quesada, J. I. P., Gil-Calvo, M., Jimenez-Perez, I., Lucas-Cuevas, Á. G., & Pérez-Soriano,P. Relationship between foot eversion and thermographic foot skin temperature after running. Applied optics. 2017, 56(19), 5559-5565.

- Catalá-Vilaplana, I., García-Domínguez, E., Aparicio, I., Ortega-Benavent, N., Marzano Felisatti, J. M., & Sanchis-Sanchis, R. Effect of unstable sports footwear on acceleration impacts and plantar surface temperature during walking: a pilot study. Retos. 2023, 49, 1004-1010.

- Cuaderes, E., DeShea, L., & Lamb, W.L. Weight-Bearing Exercise and Foot Health in Native Americans. Care Management Journals. 2014, 15 (4), 184-195. DOI: 395 10.1891/15210987.15.4.184.

- Perren, S., Formosa, C., Camilleri, L., Chockalingam, N., & Gatt, A. The Thermo-Pressure Concept: A New Model in Diabetic Foot Risk Stratification. Applied Sciences. 2021, 11(16), 7473.

- Jimenez, I., Gil, M., Salvador, R., de Anda, RMCO, Pérez, P., and Priego, JI. Footwear outsole temperature may be more related to plantar pressure during a prolonged run than foot temperature. Physiological Measurement. 2021, 42 (7), 074004. [CrossRef]

| PICO Format | |

| P (patient) | Healthy or diabetic subjects |

| I (intervention) | Measure plantar pressure and temperature and physical activity |

| C (control) | Healthy or diabetic patients |

| O (outcomes) | Changes in plantar temperature and pressure cause different plantar skin reactions during daily physical activity. |

| MeSH | Terms |

|---|---|

| Physical activity | Exercise |

| Diabetic foot | Diabetic foot |

| Plantar pressure | Plantar pressure |

| Plantar temperature | Plantar temperature |

| Plantar thermography | Plantar thermography |

| Inclusion and source | Random assignment | Hidden assignment | Baseline comparability | Blinded subjects | Blinded therapists | Blinded raters | Results above 85% | Analysis by “intention to treat” | Statiscal comparisons between groups | Measurement and variability data | Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maluf et al. 2001 [18] | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 |

| Reddy et al. 2017 [19] | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 |

| Li et al. 2022 [20] | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 |

| Nemati et al. 2022 [21] | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 |

| Niemann et al. 2020[22] | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 |

| Cabonell et al. 2019 [23] | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 |

| Di Benetto et al. 1996 [24] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 9 |

| Di Benedetto et al. 2002 [25] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 9 |

| Yavuz et al. 2014 [26] | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 |

| Priego Quesada et al 2017 [27] | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 |

| CataláVilaplana et al. 2023 [28] | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 |

| Cuaderes et al. 2014 [29] | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 |

| Perren et al. 2021 [30] | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 |

| Jimenez et al. 2021 [31] | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 |

| Author (year) | Aim | Participants/Methodology | Intervention | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maluf et al. [18] (2001) |

To validate a portable electronic device used to observe plantar pressures and temperatures, as well as the humidity of the foot inside shoes during prolonged activity. | 4 healthy participants wearing a shoe containing sensors for pressure, humidity and temperature. Inner level walkaway for pressure data; uncontrolled outdoor environment for step count data; closed environmental control chamber for humidity and temperature data. |

Data was collected during the following activities: sitting down and getting up from a chair, bending down to pick up a 6kg object from a shelf at a height above the shoulders, going downstairs, walking on a level concrete surface, hip strategy walks and a pivot walk | The combination of increased pressure, temperature and moisture inside the shoe could contribute to plantar tissue injury. Activity-related variations in foot pressure may help explain why the researchers were unable to identify people at risk of ulceration based on a predetermined pressure threshold. It is likely that the cumulative stress on the plantar tissues varied greatly between individuals, given the differences in the amount and type of activity they performed throughout the day. The environmental conditions within the shoe may modulate the response of the plantar tissues to mechanical stress. |

| Reddy et al. [19] (2017) | To examine the relationship between foot temperature and walking cadence and how this affects the vertical pressures exerted on the foot. | 18 healthy volunteers in 2 age groups (30-40 years and over 40 years). Personalised insoles in canvas shoes (mod. 246033 Slazenger) with temperature sensors (TMP35) directly in contact with the foot+ sock+ pressure system (F-Scan. Model 3000E. Telk scan Inc.) |

Temperature, pressure and acceleration data were recorded with the patient sitting for 10 minutes, standing for 15 minutes, walking for 45 minutes on a monitored treadmill (Ergo ELG 70, Woodway GmBH) and then sitting again for 20 minutes. Studies at 3 different cadences (80, 100 and 120 stpes/minute). |

Foot temperature increased 5ºC with walking in both age groups and was greater with increased walking cadence. The walking speed was found to be proportional to the increase in temperature; however, the final temperatures recorded after walking did not differ. A maximum plateau value was observed, above which the temperature of the foot did not rise. There was an inversely proportional correlation between foot temperature during walking and before exercise which was stronger in the older group. In both age groups, the increase in temperature did not correlate with the time integrals of the normal pressure exerted by the foot. |

| Li et al. [20] (2022) | To examine the effects of shoe upper materials on foot relative humidity and temperature in older individuals. To examine the influence of the thermal environment of footwear while engaged in sitting activities. |

40 older people (25 female/ 15 male) walked and sat in 4 conditions: barefoot (group A), leather trainer shoes with an ethyl vinyl acetate sole (groups B), mesh trainer shoes with ethyl vinyl acetate sole (group C) and closed-toe trainer shoes with rubber sole (group D). Skin temperature was recorded with an infrared camera (FLIR T420bx, Systems, Inc., Wilsonville, OR, USA). |

After foot conditioning for 30 minutes while sitting, the participants performed 2 tests: 20 minutes in a sitting test and 30 minutes walking on a treadmill at 3mk/h. The average recovery time between these 2 tests was 15-30 minutes. Thermal images of the feet were taken both before and after each test. Three assessment scales measuring thermal comfort and perceived humidity were performed. |

Foot temperature increased during sitting with the greatest difference between the barefoot condition and the 3 shoes conditions being on the back of the toes (2,8ºC, 1,2ºC and 1,8ºC respectively) and on the heel (3,1ºC and 2,5ºC respectively). Compared to barefoot condition temperatures were higher for all the shoes conditions while walking with the highest temperature being registered in group D. The greatest difference between the barefoot and the 3 shoes condition was on the back of the toes (2.3ºC, 1.4ºC and 2.4ºC respectively). On the foot sole the temperature was higher for all shoe conditions at all the ROIs, except for group C. The greatest difference in average temperature between groups A and B (2.4ºC) was in the toes. Compared to the barefoot condition, groups C and D showed the greatest differences in the plantar arch (2ºC and 2.5ºC, respectively) While sitting, the relative humidity of the foot increased by the greatest amount on the foot sole in shod conditions (B and D) and on the back of the foot for shod condition B. During walking, the relative humidity tended to decrease with shoes, especially in condition C, in planar arch. On the back of the foot, it increased in B condition. Thus, foot sweating increased more in group B compared to C and D, both while walking and sitting. |

| Nemati et al. [21] (2022) | To develop a temperature-prediction model in the metatarsal area and plantar arch. To evaluate the accuracy of the model when predicting the temperature of the sole of the foot. |

Seven healthy adult males wearing running shoes without socks. Foot temperature was measured at several points every minute using thermocouples. |

Participants rested for 10 minutes and then ran for 30 minutes at 3, 6 and 9km/h respectively. | The maximum increase in plantar temperature was 6ºC, 8ºC and 11.5ºC for speeds of 3, 6 and 9 km/h, respectively. Cooling of the foot through seating as thermoregulatory mechanism was minimal at 3 km/h and appeared after 15 minutes in the plantar arch area at 9km/h and after 20 minutes at 6km/h. Sweating played a fundamental role in the thermal regulation of the plantar arch but was insignificant in the metatarsal area. |

| Niemann et al. [22] (2020) | To analyse the differences in plantar temperature changes during prolonged standing between healthy volunteers and diabetic patients with polyneuropathy. | 31 healthy volunteers and 30 diabetic with polyneuropathy volunteers. Insole with 8 pressure (TTForce A01) and temperature (NTC 805) sensors in shoes for diabetics. The environmental temperature inside the shoe was also recorded without contact with the foot. |

Pressure and temperature data were recorded during 6 episodes of standing lasting 5, 10 and 20 minutes each and separated by 5-minutes periods of sitting. | The reduction in plantar temperature was significantly greater in the standing position compared to the seated position in both healthy and diabetic patients with polyneuropathy. However, the magnitude of the reduction in peak temperature did not differ between the two groups, reaching -1°C for a period of 20 minutes and decreasing further by a smaller magnitude throughout the test. Healthy volunteers felt discomfort in their feet during prolonged standing which forced them to carry out brief episodes of pressure relief. This was not the case in patients with diabetes and polyneuropathy. Transiently decreased plantar temperatures can cause injuries during prolonged episodes of standing. |

| Carbonell et al. [23] (2019) | To evaluate thermographic images after thermal and mechanical stress. | Thermal images of the feet of two groups of participants (diabetic patients and healthy controls) were recorded with a thermal imaging camera (FLIR E-60, Flir Systems Inc., Wilsonville, OR, USA) at a distance of one metre. The regions of interest (ROIs) evaluated were: big toe, forefoot, midfoot and rearfoot. |

Thermographic images were obtained before and after a 100 metres barefoot walk on a treadmill at a self-selected pace. Subsequently, a thermal stress (gel refrigerated at 0ºC) was applied to the soles of the feet, followed by thermographic video analysis of the basal thermal recovery rate over 10-minute period. |

A greater decrease in temperature was observed in all ROIs in the diabetic patients after mechanical stress when compared to the control group. The rearfoot and the forefoot presented the greatest temperature differences between the groups (-1ºC). The recovery of 90% of basal temperature after thermal stress was slower in diabetic patients. |

| Di Benedetto et al. [24] (1996) | To study regional hypothermia as a response to minor injuries. | 1000 new male army recruits aged 17 to 21 years, divided into four groups. Group 1 with unilateral stress fractures and regional hypothermia, group 2 with unilateral stress fractures without regional hypothermia, group 3 with bilateral stress fractures without hypothermia and group 4 (controls) without musculoskeletal discomfort. AGEMA 870 thermographs were performed. |

Infrared images were taken before and after training. If there was pain and suspected stress fracture a bone scan was performed. | The sensitivity of the thermograms for detect anomalies was high, but their specificity for basic diagnosis was low. Pain or injury to the lower extremities could cause an acute hypothermic response. Hypothermia was not observed in recruits in the absence of significant pain. Therapeutic or self-imposed immobilisation could lead to hypothermia. |

| Di Benedetto et al. [25] (2002) | Use thermography as a diagnostic tool in cases of stress fractures during military physical training. | New male army recruits aged 18 to 22 years, divided into 3 groups of 30 soldiers each one. Group 1 (stress fractured), group 2 (neuromuscular system problems, no fracture) and group 3 (controls). AGEMA 870 thermographs were performed using CATSE software. |

Infrared images were taken and plantar thermographs were analysed before start a basic training and were repeated whenever a subject presented a neuromusculoskeletal complaints. If a stress fracture was suspected a bone scan was performed. |

Temperature was on average 6°C higher for metatarsal stress fractures. Hot spots were observed even in the absence of negligible discomfort. Furthermore these hot spots did not reappear on subsequent thermograms as the feet became accustomed to new stress. The incidence of stress fractures, especially in the metatarsals, appeared in the third week as the intensity and training duration increased. The hot spots disappeared as the injuries healed. A correlation of 66% was observed between pain, bone scan results and the findings of thermograms. Soft tissue injuries appeared in areas that were warmer than those of the bone injuries. |

| Yavuz et al. [26] (2014) | To analyse the relationship between plantar triaxial loading and post-excersice plantar temperature increase. | 13 Healthy volunteers. Infrared camera (TiR2FT, Fluke Corporation, Everett, WA) used without contact. Custom made pressure shear plate. |

Participants walked on the shear plate at self-selected speeds using the two-stpes method while shear stress data were collected. They then walked barefoot on a treadmill at 3.2km/h for 10 minutes before returning to the shear plate to collect post-exercise shear stress data. Data from 4 trials were used in most cases. Pre- and post-exercise temperature data were recorded. |

The following variables were calculated: maximum shear stress (PSS), maximum resultant stress (PRS) and maximum temperature increase (AT). There was a moderate linear relationship between PSS and AT. The post-exercise correlation between PSR and AT was strong (p=0.002). However, the location of the peak AT was unable to successfully predict the location of PSS in 23% of the volunteers. No statistically significant correlation was observed between AT and PRS. Furthermore, in 39% of subjects, AT coincided with the peak observed in the study. |

| Priego Quesada et al. [27] (2017) | To determine the relationship between the temperature of the sole of the foot (through infrared thermography) and foot eversion during running (through motion analysis). | 22 runners (17 men and 5 women) performed a pre-test and a main test on different days (1 week apart). Pre-test: 5-minute maximal effort run on a 400m track to determine their maximal aerobic speed (MAS). Main test: running on a treadmill with 1% incline (Technogym SpA, Gambettola, Italy). Participants warmed up for 10 minutes at 60% of their MAS and then run for 20 minutes at 80% of their MAS. Foot temperature was measured with a thermal imaging camera (FLIR E-60, Flir Systems Inc., Wilsonville, Oregon, USA) before and after the test and foot eversion was recorded throughout the test. ROIs: the rearfoot (defining length as 31% of the entire plantar surface of the foot), the medial and lateral ROIs (defined as 50% of the maximum foot width). |

Thermal images were taken of each participant at 3 time points: before, immediately after and 10 minutes after the running test. During running the participants wore only their running shoes (with no socks). |

There was a weak negative relationship between contact-time eversion values and rearfoot thermal symmetry measured immediately after running and a weak positive relationship with rearfoot thermal asymmetry at the final temperature. The maximum eversion values in the stance phase showed a weak negative relationship with foot thermal symmetry measured immediately after running and a weak positive relationship with foot thermal asymmetry at the final temperature. |

| Catalá-Vilaplana et al. [28] (2023) | To analyse how different types of sports footwear (traditional stable shoes vs. unstable shoes) affect the acceleration impacts on the tibia and forehead, as well as the variation in plantar surface temperature. | 6 athletes (4 female and 2 male) assessed on 2 days, 1 week apart. On the first day anthropometric variables (height and body weight) were recorded and the foot typology was characterised using the Foot Posture Index. On the second day, the treadmill walking test was conducted under two footwear conditions: stable shoes (Adidas Galaxy Elite Noir) and unstable shoes (Skechers Shape Ups.) Two triaxial accelerometers with a frequency of 420 Hz were used, one on the distal tibia of the dominant leg and another on the forehead (MMA7261QT, Freescale Semiconductor©, Munich, Germany). The surface temperature of the feet’s soles was measured with a thermal imaging camera (FLIR E60bx, Wilsonville, Oregon, USA). ROIs evaluated: forefoot, midfoot and rearfoot. |

Participants walked for 10 minutes with each type of footwear at a speed of 1.44 m/s, with a 2-hour period of rest between each test. The spatiotemporal and acceleration variables were obtained from the three 8-second recordings taking at minutes 2, 5 and 9 of each test. Thermal records were recorded at 3 different time points: pretest, post (immediately after the test) and post 5 (5 minutes after finishing the test). |

No statically significant differences were identified in any of the accelerometry variables. Significant differences were found in the thermographic images between the pretest and post5 time points, specifically in the midfoot area. |

| Cuaderes et al. [29] (2014) | To assess diabetic sensory neuropathy and the plantar characteristics of pressure and temperature, among others, in adults after performing moderate-intensity weight-bearing activities. | A convenience sample (n=148 diabetics; 57 female and 36 male Athletes and 28 female and 27 male non-athletes). Data on plantar skin hardness (using a hand-held durometer), pressure in the sports shoes (scan in-shoe pressure) and plantar temperature (using an infrared dermal thermometer) were recorded. |

The volunteers walked 9.14 m at self-selected speed. Temperature and plantar pressure data were recorded after the test. | Athletes, especially women, had higher plantar pressure. The data indicated that the values were higher, particularly in the right midfoot locations (exercisers 1.79±0.65; non-exercisers 1.61±0.51, p = 0.03) and the region of the fourth and fifth toes of the left foot (exercisers 2.41±1.51; non-exercisers 1.93±1.13, p = 0.02). A comparison of the mean values for the two groups revealed that the left fourth metatarsal head exhibited a lower mean for the exercisers (2.64±0.90) than for the non-exercisers (3.04±1.47). A greater temperature gradient was observed in the plantar surface of the first metatarsal head in the athletes (exercisers 1.66±1.31 and non-exercisers 1.20±1.20, p = 0.02). The only significant linear relationship between weight-bearing physical activity and plantar pressure was identified at the second metatarsal of the right head (r = .237, p = .02) and at the third metatarsal of the head (r = .264, p = .01). |

| Perren et al. [30] (2021) | To ascertain whether there was a correlation between pressure and the temperature in different regions of the foot in different categories of participants after 15-minute’s walk. | 4 groups of 12 individuals (a total of 42 males and 6 females) as follows: healthy patients (Group A), patients with diabetes (Group B), diabetics with peripheral arterial disease (Group C) and diabetics with neuropathy (Group D). A Tekscan high resolution (HR) treadmill (Tekscan, Boston, MA, USA) was employed to collect plantar pressure data. ROIs were evaluated: the hallux, 1st metatarsophalangeal joint (MPJ), 2nd-4th MPJ, 5th MPJ and heel. Thermal imaging was conducted using a thermal camera (T630C FLIR, Wilsonville, OR, USA). ROIs evaluated: hallux, medial, central and lateral forefoot and heel. |

The results from 3 pressure test were recorded for each participant while they were walking at their preferred speed. Subsequently, the participants lay in a supine position on the examination table for a period of 15 minutes. After they walked for 15 minutes on a treadmill. One minute after stopping walking, thermograms were obtained of the plantar surface of the feet. |

In the initial statistical test the 4 groups were divided into 2 merged groups: a healthy cohort (groups A and B) and a complication cohort (groups C and D). In the groups with complication, there was a positive correlation between temperature and pressure in the hallux 2nd -5th MPJs, and heel ROIs. This correlation was exclusive to the 5th MPJ in the healthy group. In the second statistical test, the 2 groups were divided into healthy cohort (group A) and a diabetes cohort (groups B, C and D). There was a positive correlation between temperature and pressure for all the ROIs in the diabetes group, whereas in the healthy group, this correlation was evident only for the 2nd-5th MPJs. In individuals without complications (groups A and B) there was a tendency for pressure areas to become warmer, although this was less significant than in individuals with complications (groups C and D). |

| Jiménez et al. [31] (2021) | To determine correlation between plantar pressures during prolonged running and plantar temperature, either in the sole of the foot or the sole of the shoe. | 30 recreational runners (15 males and 15 females) were recruited to perform a 30-minute running test on a treadmill (Excite Run 900, Technogym Spa, Gambetta, Italy). Thermpgraphic images were obtained of the sole of the feet and the sole of the shoes using an infrared camera (Flir E60bx, Flir Systems Inc., Oregon. USA) at two time points: 1 minute before the test and immediately after. Dynamic plantar pressure was measured at 200 Hz after the test using an F-Scan® in-shoe pressure measurement system (v.50, Tekscan Inc., Massachusetts, USA). |

Participants ran on a treadmill for a total of 6 minutes, followed by 30 minutes of treadmill running with a 1% slope to simulate the duration and intensity of regular training. Two thermographic images were taken of the soles of the dominant feet and soles of the sports shoes in a sitting position. The first image was taken one minute before the 30-minutes test and the second one minute afterwards. Dynamic plantar pressure was measured at the end of the trial. |

A moderate correlation was observed between plantar pressure and plantar temperature, both in the soles of the feet and in the soles of the shoes, especially in the forefoot regions. The correlation between plantar pressure and plantar temperature was greater in the soles of the shoes than in the soles of the feet. The temperature of the shoe soles was observed to be lower in the female participants than the male participants after running. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).