1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a catastrophic impact on society, healthcare systems, and the global economic system. It has brought about unprecedented changes to the modern world, significantly altering people’s perception of public health. This global event has exposed the weaknesses in our social structures and environmental systems, exposing the fragility of what we once considered a stable and developed society (Aral et al., 2022; Chu et al., 2021). In fact, the current pandemic is likely the first event of its kind since the 1918-1919 Spanish flu pandemic, and it can be compared to that event in terms of its profound consequences for society.

The high transmissibility of the SARS-CoV-2 virus has contributed to its rapid spread (Carabelli et al., 2023). However, the virus’s incidence, severity, and mortality rates vary significantly among different regions and countries. These disparities cannot be solely attributed to differences in healthcare systems or socioeconomic factors; some may stem from the disproportionate influence of certain environmental factors. Numerous analyses have examined the impact of various environmental factors, including air pollution, humidity, air temperature, dew point temperature, precipitation, wind speed, global radiation, and sunshine, on COVID-19 severity, morbidity, and mortality. Literature in this area has grown exponentially, with hundreds of studies now offering various results (see related reviews in (Anand et al., 2021; Anand et al., 2023; Barakat et al., 2020; Bart et al., 2023; Bayram et al., 2024; Bozack et al., 2022; Bourdrel et al., 2021; Bronte et al., 2023; Conticini et al., 2020; Culqui et al., 2022; D’Amico et al., 2022; Feng et al., 2024; Hernandez Carballo et al., 2022; Kang et al., 2021; Liang & Yuan, 2022; Mandal et al., 2022; Marchetti, et al., 2023; Marquès & Domingo, 2022; McClymont & Hu, 2021; Mejdoubi et al., 2020; Musonye et al., 2024; Perone, 2022; Prévost et al., 2021; Runkle et al., 2020; Taylor et al., 2022; To et al., 2021; Toczylowski et al., 2021; Tripathi et al., 2022; Xie & Zhu, 2020; Ishmatov, 2022; Ishmatov et al., 2022; Ishmatov et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2020; Wiemken et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2020a,b; Zorn et al., 2024)).

Adding to the confusion and complexity of understanding the pandemic are the disparities in the population-level impact of COVID-19. These disparities vary significantly across cities globally and among different population groups and areas within these cities and settlements (Alidadi et al., 2023; Benita et al., 2022; Champlin et al., 2023; Hernández et al., 2023; Moolla & Hiilamo, 2023; Naudé & Nagler, 2022; Jain et al., 2022; Zhuang et al., 2024).

Research indicates that older age and sex are important predictors of disease severity. Men have a significantly higher risk of severe disease progression and death from COVID-19 than women (Bartleson et al., 2021; Fortunato et al., 2021; Gold et al., 2020; O’Driscoll et al., 2021; Office for National Statistics, UK., 2020; Park, 2020; Statsenko et al., 2022; Tharakan et al., 2022; Taslem Mourosi et al., 2022; Ishmatov, 2020b; Lee, 2022).

Alarmingly, the mortality rate for COVID-19 among individuals over 75 years old is 80 times higher compared to younger age groups (Akbar & Gilroy, 2020; Metcalf et al., 2022; O’Driscoll et al., 2021). Generally, elderly individuals face a greater risk of lung damage and severe outcomes from respiratory virus infections like influenza (Pop-Vicas & Gravenstein, 2011).

Moreover, a growing body of literature has focused on the disproportionate risk of poor clinical outcomes among population subgroups: COVID-19 has had a disproportionate impact on racial and ethnic minorities compared to the White population in the same areas (Cojocaru et al., 2023; Gold et al., 2020; Lee, 2022; Luck et al., 2022; Mathur et al., 2021; Office for National Statistics, 2020; Xu et al., 2024). Studies conducted in the US clearly showed that older age groups, Hispanics, and other minorities had higher in-hospital death rates, longer hospital stays, and higher Hospital intensive care units (ICU) admission rates among COVID-19 patients (Aburto et al., 2022; Garcia et al., 2021; Lee, 2022).

Nguemeni Tiako & Browne (2023) showed that the interaction between race and age was significant among Black individuals aged 60 and older: an additional 708.5 deaths per 100,000 people compared to White individuals aged 60 and older. Black individuals had a higher mortality rate than White individuals. The impact was greater on Black males, and elderly Black individuals were particularly more vulnerable to COVID-19 in terms of mortality.

At the same time, Luck et al. (2022) found that while COVID-19 death rates in 2020 were highest in the Hispanic community, Black individuals experienced the largest increase in all-cause mortality between 2019 and 2020. This adverse trend in all-cause mortality within the Black population was primarily driven by significant increases in mortality from heart disease, diabetes, and external causes of death.

A report by the Office for National Statistics of the United Kingdom (Office for National Statistics, 2020) states that the probability of dying from coronavirus among infected Black people is approximately 4 times higher than in patients of European descent. People of Bangladeshi, Pakistani, Indian, and mixed nationalities also had a statistically significant increased risk of death from COVID-19 compared with white people. This is partly due to differences in the sociodemographic situation, but even after adjusting for this factor, the risk was 1.9 times higher. Similarly, men in the Bangladeshi and Pakistani ethnic groups were 1.8 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than white men; for women, this indicator was 1.6. Scientists are not yet ready to explain these results.

Several disparities have been partly attributed to a combination of physical, physiological, socio-economic factors, and behavioral elements (Anand et al., 2023; Bontempi, 2020; Bontempi & Coccia, 2021; Culqui et al., 2022; Gavenčiak et al., 2022; Mathur et al., 2021; Josey et al., 2023). Another possible explanation is biological inequality. For instance, the greater susceptibility to severe illness and increased mortality from COVID-19 among older individuals and males may be related to age-related changes in the immune system, which reduce the ability to mount a strong immune response against SARS-CoV-2. Additionally, the increasing prevalence of other health conditions with age can contribute to more severe COVID-19 cases, further complicating the understanding of the pandemic (O’Driscoll et al., 2021; Bartleson et al., 2021; Rydyznski Moderbacher et al., 2020).

The severity of COVID-19 is also associated with the human innate immune system (Schultze & Aschenbrenner, 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic has shown a male bias in mortality, consistent with other viral infections. Biological sex differences may affect susceptibility, pathogenesis, immune responses, and inflammation resolution (Scully et al., 2020). The study conducted by Takahashi et al. (2020), as underscored by Park (2020), showed significant differences in immune responses to early-stage SARS-CoV-2 infection between men and women. It implies that the immune landscapes in COVID-19 patients differ considerably between genders, potentially causing men to be more susceptible to the disease.

Overall, there are many hypotheses attempting to explain some patterns, but they cannot provide the full picture. This indicates a need for further research in this area. In our search for comprehensive explanations of the distinct health outcomes and disparities observed in the impacts of COVID-19, we find a promising lead in the hypothesis proposed in previous works (Ishmatov, 2020b; Ramasamy, 2021).

The Hypothesis

The hypothesis suggests that changes in nasal airway parameters—related to age, gender, and race—can lead to functional variations in the airways. This may render some individuals more vulnerable to environmental influences. Under certain conditions, these factors could significantly increase the respiratory system’s susceptibility to infectious agents, thereby raising the likelihood of severe conditions such as pneumonia and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).

The hypothesis pertains to the well-documented effects of cold and dry air on the respiratory tract’s epithelium, cellular immunity, and other protective mechanisms. Additionally, the impact of air pollutants on the respiratory system is well-studied in contemporary literature (see discussion below). It is recognized that significant interpersonal differences in the structure and functioning of the respiratory system can influence individuals’ ability to heat, moisturize, and filter inhaled air from aerosols, including air pollutants and infectious aerosols (Assanasen et al., 2001; Bennett and Zeman, 2005; Bennett et al., 1996; Churchill et al., 2004; Elad et al., 2008; Garcia et al., 2009; Hörschler, 2006; Hounam et al., 1969; Lindemann et al., 2008, 2009; Lizal et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2018; Maddux et al., 2016; Marks et al., 2019; Maréchal et al., 2023; Naftali et al., 2005; Naclerio et al., 2007; National Research Council (US) Panel on Dosimetric Assumptions Affecting the Application of Radon Risk Estimates, 1991; Noback et al., 2011; Rouadi et al., 1999; White et al., 2011, 2015; Wolf et al., 2004; Xi, 2014; Xi, 2015; Zaidi et al., 2017). Consequently, each person’s respiratory system may respond differently to external factors. This response is shaped not only by the intensity and duration of exposure to these factors but also by the unique characteristics of the individual’s respiratory system.

Thus, the central idea of the hypothesis is that external factors, such as air pollution, cold, or dry air, do not affect all people equally. This variation in influence can be explained not only by differences in living conditions and immune landscapes but also by variations in the characteristics of the nasal passages responsible for filtering, warming, and conditioning inhaled air.

(Aim)

This work aims to analyze existing data to evaluate how differences in nasal morphology related to age, gender, and race affect the respiratory system’s ability to protect against external influences. The focus is on understanding the implications for disparities in COVID-19 outcomes and mortality.

The investigation will proceed as follows:

1. Examining the effect of temperature and air pollution on the respiratory system.

2. Investigate changes in nasal morphology related to age, gender, and race that can influence air conditioning, filtration, and clearance in the respiratory tract, as well as defense mechanisms.

3. Analyze the relationship between nasal morphology and the influence of external factors, and how these aspects can be related to variations in COVID-19 outcomes.

2. Temperature, Humidity, and Air Pollution as Aggregated Influencing Factors

The human respiratory system, because of its unique physiology, is particularly vulnerable to environmental factors. It is more susceptible to air pollution, cold or dry air, viruses, and infectious agents than other organs and systems. This predisposition leads to a higher incidence of respiratory infections and specific diseases (Huang et al., 2023; Lei et al., 2022; Patz et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2012).

2.1. Air Temperature and Humidity

During the pandemic, numerous studies established a correlation between weather conditions, such as temperature and humidity, and the severity of COVID-19 outcomes (refer to related reviews in D’Amico et al., 2022; Faruk et al., 2023; Hossain et al., 2024; Liang & Yuan, 2022; Liu et al., 2022; Ma et al., 2020; Majumder & Ray, 2021; McClymont et al., 2021; Mecenas et al., 2020; Mejdoubi et al., 2020; Nichols et al., 2021; Runkle et al., 2020; To et al., 2021; Townsend et al., 2023; Tripathi et al., 2022; Wei et al., 2022; Wiemken et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2020b; Xie & Zhu, 2020).

Inhaling cold air can reduce the temperature of respiratory epithelial cells, which could weaken the antiviral response and hinder mucociliary clearance, both vital in preventing respiratory infections (Clary-Meinesz et al., 1992; Tyrrell and Parsons, 1960; Salah et al., 1988; Eccles, 2002; Moriyama et al., 2020; Mourtzoukou and Falagas, 2007; Mäkinen et al., 2009). Foxman et al. (Iwasaki lab) (Foxman et al., 2015, 2016; Iwasaki et al., 2017) demonstrated how reduced temperature impairs the immune response in the respiratory cells of mice, showing that various strains of rhinoviruses replicated more efficiently at a lower temperature of 33 °C than at the normal lung temperature of 37 °C. Recently, Huang et al. (2023) explored the role of extracellular vesicles (EVs) derived from the nasal epithelium in innate Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3)-dependent antiviral immunity. They revealed how cold exposure impairs extracellular vesicle swarm-mediated nasal antiviral immunity.

It is well known that even among healthy individuals, prolonged exposure to cold air increases the number of inflammatory cells in the lungs (Larsson et al., 1998). The activity of macrophages, which drives innate immunity, is associated with temperature (Hardie et al., 1994; Hassan et al., 2020). In individuals with respiratory diseases, inhalation of cold air has been associated with respiratory symptoms and inhibition of lung function, epithelial injury, altered vasomotor control, bronchial hyper-responsiveness, hyperemia and hypertonicity of airway surface liquid (D’Amato et al., 2015; D’Amato et al., 2018; Scheerens et al., 2022). Regarding the hypothesis we accepted (see above), some aspects of the influence of cold air on the respiratory system from a biological and physiological point of view were also discussed in detail by Ramasamy (2021; 2022).

Moreover, exposure to environmental factors at or after symptom onset might contribute to dysregulated innate immunity (see related thorough reviews in (Moriyama et al., 2020; Prévost et al., 2021; Ramasamy, 2022; Hossain et al., 2024)). Recent studies (Hossain et al., 2024; Liang & Yuan, 2022; Ishmatov et al., 2024) have highlighted the crucial role of cold air exposure during the incubation period or when symptoms are mild. This exposure can significantly worsen the disease, leading to a higher risk of severe progression, increased hospitalizations, and deaths. Ishmatov et al. (2024) found that each short-term decrease/change in daily temperature by more than 3 °C led to an increase in the city-level hospitalization rate due to the disease’s worsening progression in infected individuals, with a 1—3 day delay. The study also observed an effect with a 7.6-day delay, potentially indicating an incubation period in high-risk patients, such as the elderly and individuals with comorbidities.

In other hand, inhaling dry air can lead to mucosal impairment, negatively affecting mucociliary clearance, innate antiviral defense, and tissue repair. The alteration of the mucous layer can disrupt epithelial junctions, increasing their permeability to pollutants, allergens, and viruses. As a result, this could lead to an increase in bacterial and viral growth (see related reviews in (Guarnieri et al., 2023; Lowen et al., 2007; Kudo et al., 2019; Moriyama et al., 2020; Randell and Boucher, 2006)). Dry conditions also affect the stability of SARS-CoV-2 in nasal mucus and sputum, with the virus having a longer half-life under low humidity conditions (21 °C/40% RH) (Matson et al., 2020).

Exposure to dry and/or cold air can weaken an individual’s resistance to respiratory infections, contributing to their increased prevalence during certain seasons. The widespread prevalence of SARS-CoV-2, like other seasonal respiratory viruses, is influenced by ambient temperature and humidity. These factors, associated with various seasonal respiratory infections such as influenza and coronaviruses, likely contribute to high morbidity and mortality rates (Christophi et al., 2021; Gavenčiak et al., 2022; Ishmatov, 2020a; Ishmatov, 2020b; Ishmatov et., 2024; Kaplin et al., 2021; Li et al., 2020; Li et al., 2022; Nichols et al., 2021; Ramasamy, 2021, 2022; Townsend et al., 2023; Wiemken et al., 2023; Xie & Zhu, 2020; Yuan et al., 2022).

* For reference, studies have revealed an association between respiratory infection seasonality in the Northern Hemisphere and cold seasons, as well as tropical countries and wet seasons. Consequently, two seasonal climate patterns for influenza seasonality are distinguished: “cold-dry” and “humid-rainy” (see related reviews in (Eccles, 2002; Lofgren et al., 2007; Lipsitch and Viboud, 2009; Tamerius et al., 2013; Martinez, 2018; Moriyama et al., 2020; Qi et al., 2022)). These well-established patterns suggest that an empirical climate-based model could provide some explanation for the diverse patterns of COVID-19, similar to those observed for seasonal influenza and other respiratory infections.

2.2. Air Pollution

Even before the pandemic, air pollution was a leading risk factor for worldwide mortality and morbidity, causing 4.5 million premature deaths globally each year (Lelieveld et al., 2019; Health Effects Institute, 2020). Now, COVID-19 has accentuated the importance of air pollution more than ever. Research has shown that air pollution significantly increases susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection, and it may intensify the severity and lethality of COVID-19 (refer to related reviews in (Anand et al., 2021; Barakat et al., 2020; Bayram et al., 2024; Bozack et al., 2022; Bourdrel et al., 2021; Bronte et al., 2023; Feng et al., 2024; Hernandez Carballo et al., 2022; Conticini et al., 2020; Ishmatov, 2020a; Ishmatov, 2020b; Ishmatov, 2022; Ishmatov et al., 2022; Marchetti, et al., 2023; Marquès & Domingo, 2022; Musonye et al., 2024; Perone, 2022; Taylor et al., 2022; Toczylowski et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020a; Zorn et al., 2024)).

Wu et al. (2020a) established a positive correlation between air pollution levels and COVID-19 case fatality rates at the onset of the pandemic. They found an 8% increase in the COVID-19 death rate with an increase of 1 μg/m3 in PM2.5 in the air. The correlation can be biologically explained by the fact that even brief exposure to certain air pollutants can weaken lung function, increasing susceptibility to infection in the respiratory epithelium. This susceptibility can lead to severe respiratory symptoms and a rise in SARS fatalities (Cui et al., 2003). This suggests that air pollution may have potential pathological effects on host defense factors and certain early immunological profiles in patients, as observed in (Beentjes et al., 2022; Lucas et al., 2020; Shears et al., 2020).

This mechanism is similar to the understanding of how diesel exhaust particles (DEP) exposure influences the risk of pneumococcal infection, as shown by a team of researchers led by Prof. Kadioglu (Shears et al., 2020). They found that inhaled DEPs enhance infection susceptibility in the lungs due to loss of control over pneumococcal colonization, increased inflammation, tissue damage, and systemic bacterial dissemination. Their research also revealed that DEP stimulates a pro-inflammatory environment within the lungs. Consequently, alveolar macrophages become overloaded with particulate matter (PM), substantially reducing their phagocytic ability. This reduction impairs bacterial clearance, resulting in higher bacterial loads in the lungs.

Moreover, a significant study by Ural et al. (2022) demonstrates that lifelong exposure to environmental pollutants can result in age-specific decline in lung-associated immune function, linked to the accumulation of inhaled carbon particulates in lung-associated lymph nodes (LNs). This accumulation, most noticeable in individuals aged 40 and above. These particulates are contained within specific macrophages, which display decreased activation, reduced phagocytic capacity, and altered cytokine production. Additionally, the structures of B cell follicles and lymphatic drainage in lung-associated LNs with particulates are disrupted, potentially affecting immune surveillance of the lung. The findings indicate that inhaled particulates have direct and cumulative impacts on innate and adaptive immune processes in the lymphoid organs responsible for monitoring the lungs and respiratory tract. This could partly account for the more severe outcomes of respiratory infections in older individuals compared to the younger population.

Overall, air pollution affects the human organism in various ways, both in the short-term and long-term (Bayram et al., 2024; Pryor et al., 2022; Ural et al., 2022; Zorn et al., 2024). Long-term exposure to atmospheric pollution can cause lasting changes to the immune system (Bayram et al., 2024; Tsai et al., 2019; Ural et al., 2022). As a result, individuals residing in areas with high pollution levels are more likely to develop chronic respiratory conditions and become susceptible to infectious agents. Even in young and healthy individuals, prolonged exposure to air pollution can lead to a chronic inflammatory response (Conticini et al., 2020).

It is widely recognized that air pollution impairs the first line of defense in the upper airways, specifically the cilia (Bayram et al., 2024; Cao et al., 2020). Acute short-term exposure to air pollutants can cause airflow limitation in both small and proximal airways, along with a reduction in neutrophil count (Wei et al., 2023). Human studies suggest, and in vitro studies confirm (see related review in (Bayram et al., 2024; Bourdrel et al., 2021; Beentjes et al., 2022; Pryor et al., 2022)), that air pollution increases the permeability of the mucous membrane, triggers oxidative stress, and generates active oxygen forms. It decreases antioxidant levels and surface-active antimicrobial proteins, impairs macrophage phagocytosis, and as a result, can diminish antimicrobial activity (Lakey et al., 2016). This is also achieved by suppressing antimicrobial proteins and peptides, such as saliva agglutinin and surfactant protein D, in the mucous membrane of the respiratory tract (Zhang et al., 2019).

Results suggest that pre-exposure to PM could alter the antiviral response of bronchial epithelial cells, exacerbating respiratory inflammation and increasing their susceptibility to viral infections, which is an important factor in the pathogenesis of various respiratory diseases (Chivé et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2023; Ural et al., 2022). Findings from Elbarbary et al. (2021) support this, showing that each 10 µg/m3 increase in PM10, PM2.5, PM1, and NO2 significantly contributes to systemic inflammation in elderly individuals.

Therefore, it’s evident that air pollution can significantly impact even a healthy respiratory system. This impact is amplified when combined with the effects of cold air, which inhibit the respiratory system’s protective mechanisms (as described in section 3.1). Moreover, as demonstrated by Ishmatov (2019; 2020a), inhaling cold or humid air can lead to vapor supersaturation and enhanced condensational growth within the airways. This significantly increases the deposition of inhaled PM and condensate on the walls of the respiratory tract, further intensifying the overall negative impact on the respiratory system.

Thus, exposure to air pollutants, cold, and dry air are significant factors that can facilitate an increase in the viral and bacterial load within the respiratory system.

3. The Nose as a Protective Barrier: General Principles

Having explored the impact of external factors on the respiratory system in the previous section, this section focuses on the general principles of the nose’s primary roles in warming, humidifying, and filtering the air to protect and maintain the respiratory system’s health.

3.1. Warming and Humidifying Air in the Nose

Research has demonstrated a considerable degree of variability in the nasal cavity’s capacity for warming and humidifying inhaled air, attributable to divergences in nasal morphology (Bennett and Zeman, 2005; Elad et al., 2008; Evteev et al., 2017; Garcia, 2009; Horschler et al., 2006; Lizal et al., 2020; Maddux et al., 2016; Naftali et al., 2005; Noback et al., 2011; Stansfield et al., 2021; Wen et al., 2008; White et al., 2011; Wolf et al., 2004; Zaidi et al., 2017).

A study by Li et al. (2023) involved an extensive cohort of over 6,000 individuals from diverse ancestries across Latin America. The findings of this study revealed a genetic inheritance from Neanderthals in humans, influencing nasal morphology. The gene linked to a taller nose structure could potentially be a consequence of natural selection as ancient human populations adapted to colder environments subsequent to migrations from Africa.

The nose, as a crucial air conditioning mechanism, has sparked discussions regarding the potential influence of climate on its evolutionary development. The extent and speed of modern human adaptation to varying climates are subjects of ongoing debate. Previous research suggests that the facial features of contemporary human populations may have been shaped by adaptation to cold and dry environments. Specifically, individuals from cold, dry climates are often observed to have narrower nasal cavities compared to those from warmer, humid regions (Evteev et al., 2017; Kelly et al., 2023; Li et al., 2023; Noback et al., 2011; Stansfield et al., 2021; Zaidi et al., 2017).

Narrow nasal cavities in cold-dry climates may facilitate better conditioning by increasing turbulence in the inspired air as it reaches the turbinates, thereby facilitating contact with the nasal mucosa (Elad et al., 2008; Kelly et al., 2023; Marks et al., 2019; Naftali et al., 2005; Zaidi et al., 2017).

Research by Maddux et al. (2016) showcased that crania from colder or drier regions typically exhibit internal nasal fossae that are longer, taller, and narrower, particularly at the superior end, in comparison to those from warmer and more humid climates. This finding supports the notion that local variations in internal nasal structure may reflect the necessity for efficient heat and moisture exchange through adjustments in the dimensions of the internal nasal airway.

The work of Marks et al. (2019) highlights ecogeographical disparities in human nasal cavity morphology that mirror climate-associated evolutionary adaptations for intra-nasal heat and moisture exchange. Their research demonstrates that individuals adapted to cold, dry conditions tend to possess nasal cavity structures that promote the interaction between inhaled air and the nasal mucosal membrane, enhancing air conditioning within the respiratory system. Conversely, individuals acclimatized to hot and humid environments exhibit nasal cavity characteristics that minimize contact between air and the mucous membrane, likely reducing airflow resistance and aiding in heat dissipation during exhalation.

According to the results of Lindemann et al. (2009), the volumes and cross-sectional areas of the nose significantly affect nasal conditioning. A healthy nasal cavity with smaller volumes and cross-sectional areas performs a more effective air conditioning function than an overly “wide” open nose, due to changes in the nature of airflow. Thus, it can be concluded that nasal airways with long and narrow channels are often considered better adapted for warming and humidifying the air.

3.2. Air Filtration and Aerosol Deposition in the Nose

The geometry of the nasal passage plays a crucial role in airflow dynamics, affecting not only air conditioning but also air filtration. There is considerable variability in nasal filtration between individuals, which can be attributed to differences in nasal anatomy and breathing patterns (Becquemin et al., 1991; Bennett & Zeman, 2005; Garcia et al., 2009; Golshahi & Hosseini, 2019; Horschler et al., 2006; Lizal et al., 2020).

In an experiment by Garcia et al. (2009), nasal filtration of 1—12 micron particles was measured in nasal replicas of five adults. A significant interindividual variability was observed in healthy individuals, with nasal filtration ranging from 40% to 90%. In contrast, a patient with atrophic rhinitis, characterized by an abnormally wide nose, exhibited poor nasal filtration, with only 15% of inhaled particles being filtered compared to 40-90% in healthy individuals.

Kesavanathan et al. (1998) and Kesavan et al. (2000) investigated the relationship between specific nasal characteristics and particle deposition in the adult nose. They found that nasal particle deposition efficiency for 2—6 micron particles increased with a decrease in the minimal cross-sectional area of the nasal passages and an increase in the ellipticity of the nostrils.a

Studies on Radon Dosimetry (Hounam et al., 1969; National Research Council (US) Panel on Dosimetric Assumptions Affecting the Application of Radon Risk Estimates, 1991) revealed that an increase in airflow resistance led to a higher proportion of inhaled particles being deposited in the nose. Lower nasal resistance was associated with decreased particle collection efficiency, resulting in enhanced particle penetration into the pulmonary airways and parenchyma. This reduced the nose’s effectiveness as a filter, potentially increasing the exposure of airways and alveoli to larger particles.

Various authors have introduced phenomenological modified-impaction parameters to assess nasal filtration capacity in order to reduce intersubject variability. These parameters are often related to nasal pressure drop or resistance measured through rhinomanometry, as well as the minimum cross-sectional area or characteristic diameter of the nasal geometry (refer to related review in (Garcia et al., 2009; Golshahi et al., 2019)).

It is reasonable to expect that a narrower and longer nasal canal would lead to a greater pressure drop, thereby enhancing filtration efficiency. This concept is grounded in fundamental physical principles. Furthermore, it is crucial to recognize that the conditions that facilitate improved nasal filtration also promote better warming and humidification of inhaled air, as discussed in the previous section.

4. Variations in Individual Nasal Abilities to Filter and Condition Air

Factors such as ethnicity, age, body size, and health status influence nasal anatomy and breathing rates, leading to variability in filtration and conditioning efficiency (Bennett & Zeman, 2005; Corey et al., 1998; Garcia et al., 2009; Golshahi & Hosseini, 2019; Keeler et al., 2016; Evteev et al., 2017; Noback et al., 2011; Stansfield et al., 2021; Zaidi et al., 2017; Maddux et al., 2016). This section focuses on how age, gender, and age-related nasal characteristics contribute to differences in filtration and conditioning abilities, possibly increasing vulnerability to severe COVID-19 outcomes and mortality.

4.1. Race-Related Nasal Morphology and Associated Functionality

As detailed in

Section 3.1, the unique structure of the nose likely evolved as an adaptation to different climates. People from colder regions tend to have narrower nasal cavities compared to those from warmer climates. This adaptation allows for more effective warming and humidifying of the air they breathe (Evteev et al., 2017; Li et al., 2023; Maddux et al., 2016; Noback et al., 2011; Stansfield et al., 2021; Zaidi et al., 2017).

Here we further discuss how the racially determined nasal structural features can affect the nose’s ability to filter air. A measure of nasal efficiency is proposed using parameters like nasal pressure drop, resistance, and the minimum cross-sectional area or characteristic diameter of nasal geometry (see discussion above).

For reference, Bennett & Zeman (2005) conducted a study that yielded important insights into nasal filtration efficiency among different racial groups. They found that African Americans have lower nasal efficiency for filtering fine particles compared to Caucasians. This lower efficiency was linked to lower nasal resistance and differences in nostril shape between the two groups. In their study, Bennett & Zeman measured the fractional deposition of 1—2 μm particles in a group of African American and Caucasian adults aged 18—31 years. They observed that under light exercise conditions, the nasal deposition efficiency for 1 and 2 μm particles was significantly lower in African Americans compared to Caucasians. The results showed that for 1 μm particles, the nasal deposition efficiency was 0.15 +/− 0.07 (SD) in African Americans versus 0.24 +/− 0.11 in Caucasians (p = 0.03), and for 2 μm particles, it was 0.29 +/− 0.13 in African Americans versus 0.44 +/− 0.11 in Caucasians (p = 0.006).

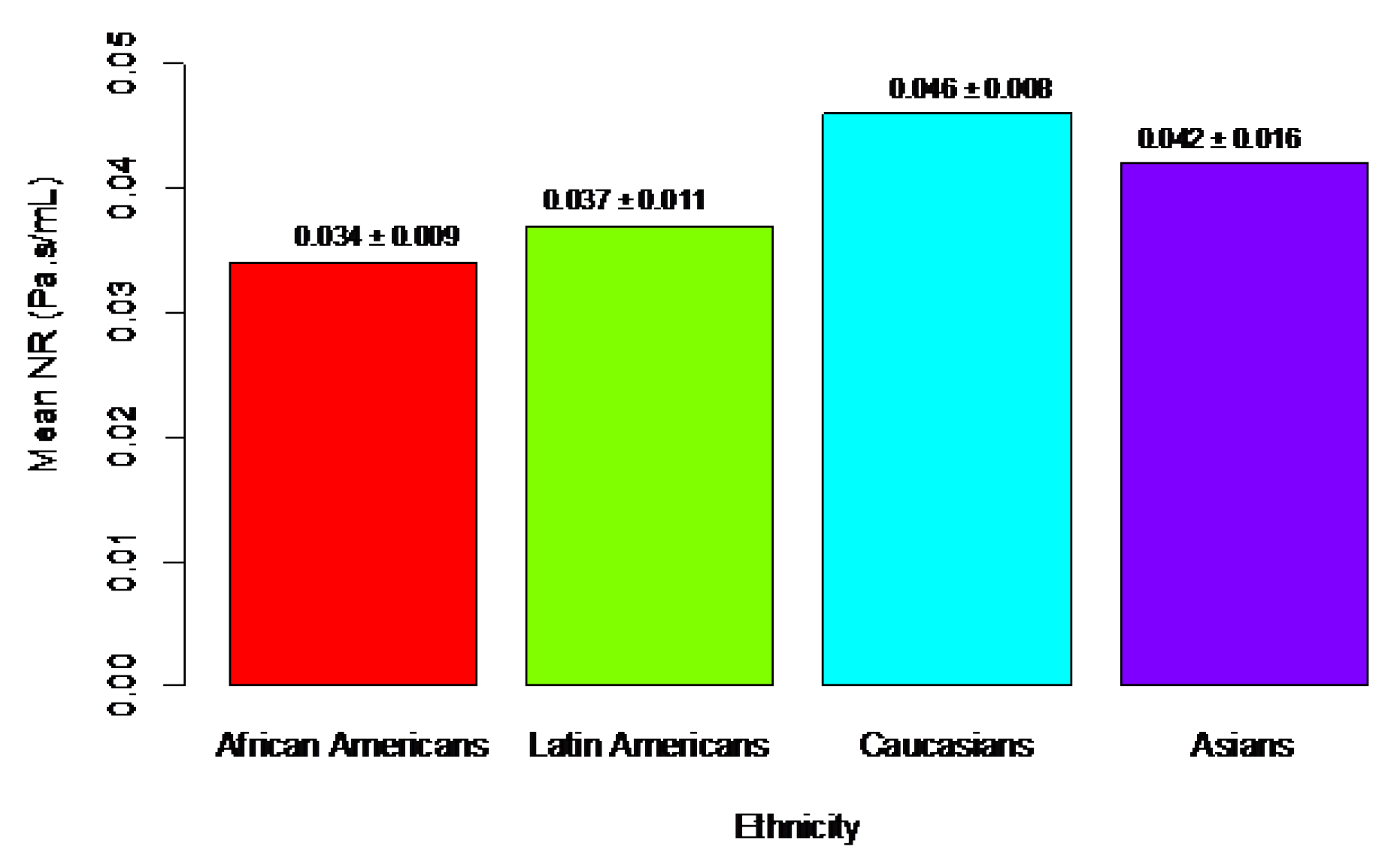

Corey et al. (1998) showed that the minimal cross-sectional area of the nasal passages is significantly larger in African Americans than in Caucasians. Keeler et al. (2016) confirmed that nasal resistance (NR) is related to ethnicity and can be associated with the nose’s ability to filter and condition air (see

Figure 1).

Specifically, the bar plot (

Figure 1) shows that the ethnicity with the lowest average NR is African Americans, followed by Latin Americans, Asians, and Caucasians, who had the highest mean NR. This corresponds with the data on nasal filtration. For comparison, data on fraction deposition in the nose for African American and Caucasian adults (Bennett & Zeman, 2005) are 0.15/0.24 = 0.625 (for 1 μm particles) and 0.29/0.44 = 0.659 (for 2 μm particles). The ratio of mean nasal resistance is 0.034/0.046 = 0.739, highlighting significant differences in nasal functions.

These findings highlight the importance of considering race-related nasal efficiencies as dosimetric factors when modeling and assessing particulate doses from human exposure to air pollutants. Understanding these differences can help develop strategies to mitigate the impact of air pollution on respiratory health in diverse populations.

It is important to note the study conducted by Maréchal et al. (2023) which analyzed 195 in vivo CT scans of adults from five different geographic regions: Chile, France, Cambodia, Russia, and South Africa. The findings revealed subtle yet statistically significant morphological differences among the five groups. Specifically, France and Russia exhibited the most similarities in terms of Nasal Airways (NAs) being longer, narrower, and protruding significantly in the supero-anterior region. Conversely, the Cambodian sample had distinctive characteristics with wider and shorter NAs. The Chilean group showed the most variation within its population, while the South African sample shared similarities with Cambodia but also had some overlap with France and Russia. Notably, the volume of the NAs varied significantly based on sex and age, being generally larger in males than in females and increasing with age.

Individuals with genetic traits from warm-humid climates often have relatively enlarged upper airways. This can lead to impaired intranasal air conditioning, issues with air filtration, and an increased destructive impact from dry and cold air on respiratory cells compared to those with genetic traits from cold climates. They’re also more prone to catch infectious aerosols and pollutants from the air, leading to precipitation in the lower airways. This could partly explain why, in the United States and the United Kingdom, Black populations and those originating from warm climates have a higher risk of death and hospitalization due to COVID-19 (Aburto et al., 2022; Aldridge et al., 2020; Cojocaru et al., 2023; Garcia et al., 2021; Garg et al., 2020; Gold et al., 2020; Lee, 2022; Luck et al., 2022; Mathur et al., 2021; Nguemeni Tiako & Browne, 2023; Office for National Statistics, 2020; Xu et al., 2024).

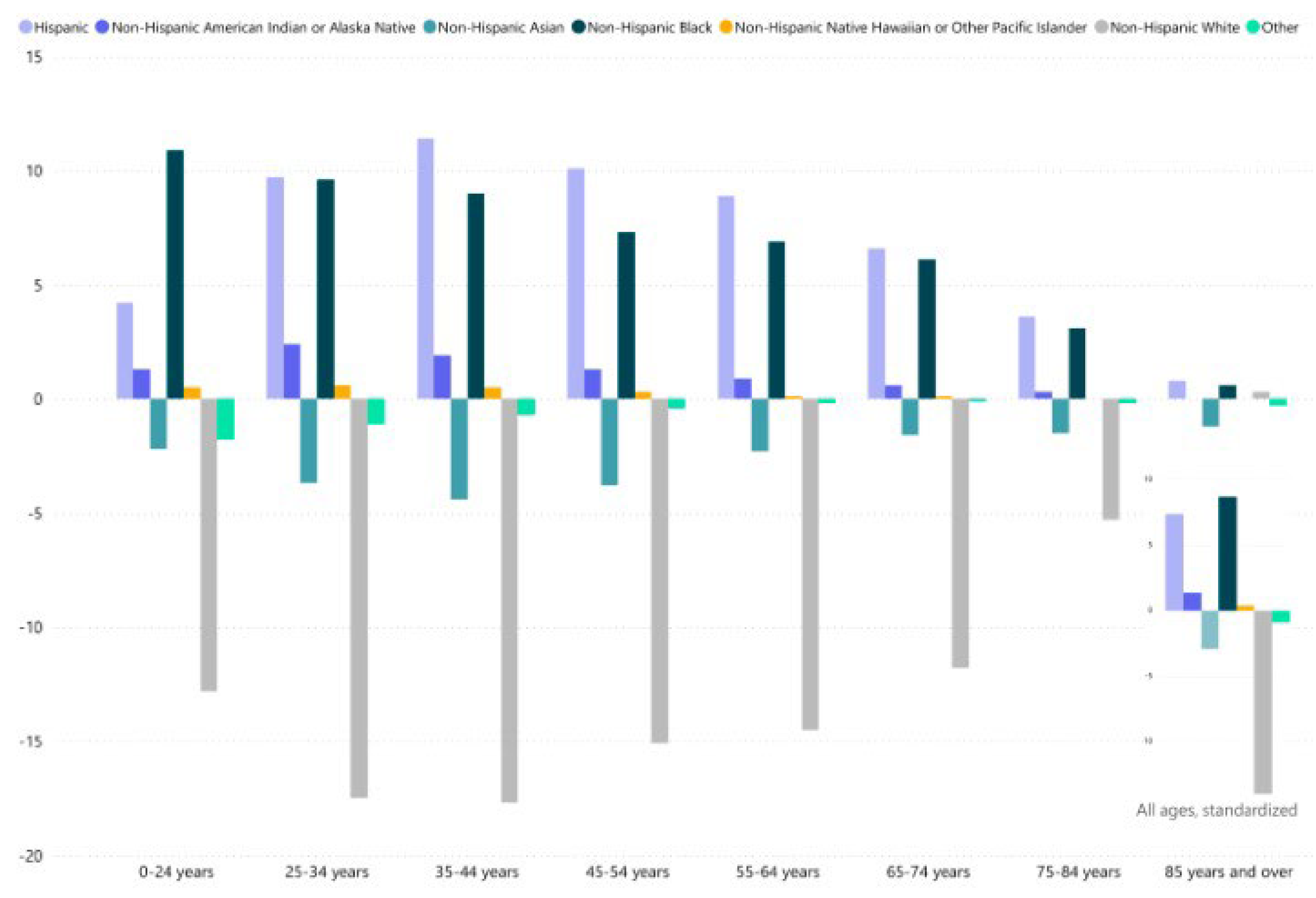

Important observations can be made by referring to the official statistics on Provisional Death Counts for COVID-19 from National Center for Health Statistics (US) for the entire period of the pandemic from 2020 to 2023 (

Figure 2).

Figure 2 shows the age variations between the percentage of COVID-19 deaths and the percentage of the unweighted population represented by each race. These diagrams illustrate whether certain racial groups have a higher or lower share of COVID-19 deaths compared to their distribution in the population, both across and within age groups.

Analyzing the data in

Figure 2 allows us to make the following observation about the risk of death from COVID-19: the highest risk is observed among Non-Hispanic Black individuals, followed closely by Hispanic individuals. Non-Hispanic Asians have a significantly lower risk of death, while Non-Hispanic Whites have the lowest risk of death from COVID-19.

A significant observation can be made by comparing the data from

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. There is a clear correlation between functional nasal morphology related to race and COVID-19 mortality: the ethnicity with the poorest nasal functions has the highest risk of death from COVID-19, and vice versa.

Another contributing factor is that, in addition to the impacts of COVID-19, there is a similar mortality pattern related to air pollution exposure. One piece of evidence supporting this comes from a recent study by Geldsetzer et al. (2024). This study showed that differences in mortality attributable to PM2.5 in the pre-pandemic period were consistently more pronounced between racial/ethnic groups than by education level, rural area, or social vulnerability index. Notably, the African American population had the highest proportion of deaths attributable to PM2.5 from 1990 to 2016. Over half of the age-adjusted mortality difference from all causes between African Americans and non-Hispanic whites was associated with PM2.5 from 2000 to 2011.

Furthermore, disproportionate exposure to air pollution worsens the burden on minoritized and low-income populations (Josey et al., 2023; Mork et al., 2024). In the US, racial disparities exist in exposure levels, with non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics facing higher exposure than whites (Bell & Ebisu, 2012). People in racially segregated communities are exposed to highly toxic particulate matter, with metal concentrations from human-made sources nearly ten times higher (Kodros et al., 2022).

Therefore, the complexity of the COVID-19 situation is heightened for individuals with pre-existing race-related nasal issues. These individuals not only face challenges such as nasal protection from dirty, cold, and dry air, but also experience disproportionate exposure to air pollution and suboptimal environmental conditions due to race- and social- related factors.

4.2. Sex-Related Nasal Morphology and Associated Functionality

Numerous studies have shown that men across various populations have larger nasal passages than women. These differences are typically attributed to men’s need to inhale a larger volume of air with each breath to adequately oxygenate their larger, muscular bodies (Churchill et al., 2004; Bastir et al., 2020; Kelly et al., 2023; Maréchal et al., 2023; Marks et al., 2019; Russel & Frank-Ito, 2023).

Bastir et al. (2020) demonstrated through a three-dimensional analysis of sexual dimorphism in the soft tissue morphology of the upper airways in a human population that the differences in 3D nasal airway morphology are consistent with the respiratory-energetics hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, males differ from females due to higher energetic demands. They concluded that structures related to air inflow and outflow show stronger signals than those relevant for air-conditioning. It is important to note that the ‘metabolic hypothesis’ primarily pertains to the cross-sectional size of the nasal passages (i.e., height and width dimensions), since the length of the nasal passages minimally restricts air intake in humans.

Kelly et al. (2023), based on computed tomography (CT) scans of 79 mixed-sex crania from an extreme cold-dry locale (Point Hope, Alaska), found a significant correlation between overall nasal size and Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) across and within sexes. Larger noses were predictably associated with higher metabolic demands. Their results suggest that climatic pressures on nasal passage breadths for heat and moisture transfers may necessitate compensatory changes in passage heights (and developmentally-linked lengths) to maintain sufficient air intake to meet metabolic requirements. However, it was observed that the correlations between BMR and overall nasal size were predominantly driven by nasal passage height and length dimensions, with the Arctic sample exhibiting minimal variation in nasal passage widths. Significant correlations were also identified between BMR and 3D nasal shape.

Despite metabolically mediated differences in nasal passage size, it is widely recognized that people living in the same climate should experience comparable levels of heat and humidity in inhaled air to maintain proper lung function and respiratory health (Bastir et al., 2020; Corey et al., 1998; Kelly et al., 2023). Marks et al. (2019) found significant morphological differences between regional samples from Arctic and equatorial populations, with no evidence of significant sexual dimorphism or an interaction effect between region and sex.

Bastir et al. (2020), using a sample of men and women from Spain, provided some support for this claim. They showed that sex-based differences in nasal passage size were also accompanied by differences in shape, which the authors attributed to the need for men and women living in the same climate to have equal air conditioning capabilities.

On the other hand, research by Russel & Frank-Ito (2023) reveals differences in the normal anatomy and physiology of the nose between men and women among Caucasians. Women exhibited a higher heat flow (males: average = 158.5 W/m²; women: average = 191.8 W/m²). The data also showed that men have significantly larger nasal passages and lower total nasal resistance (NR) to airflow. This is supported by nasal airflow resistance measurements using rhinomanometry (Ren et al., 2018; Shah & Frank-Ito, 2022).

The data suggests that the nose’s ability to warm and moisten inhaled air should be similar in both men and women under the same climate conditions. However, the morphological and geometric differences, along with the differences in heat flow, suggest strong differences between men and women. Anatomical variations do influence nasal physiology, but the sex differences in physiology remain unclear. Drawing definite conclusions is challenging due to the lack of specific data on this subject.

(Doses)

The conditioning of the nose in both men and women is a topic of discussion, particularly regarding the potential impact of cold or dry air on the respiratory tract. The ability of the nose to filter air also raises questions. Notably, men consume more air than women, resulting in a higher dose of air pollutants under the same exposure conditions.

Bennett et al. (1996) showed the difference in the total volume of deposition in the lungs of inhaled 2 µm particles between men and women. This difference is due to the higher inhalation volumes observed in men. It’s important to note that these experiments were conducted through mouth-breathing, without involving the nose.

The study by Voliotis and Samara (2018) demonstrated that males received higher doses of submicron particles compared to females across all age groups. This is due to different physiological parameters, such as a higher functional residual capacity (FRC) and tidal volume (TV).

Furthermore, Wei et al. (2023) found that acute short-term exposure to air pollutants was linked to airflow limitation in both small and proximal airways, as well as a lower neutrophil count in adults from the general community in Shanghai, China. In a subgroup analysis, significant negative associations between the five pollutants and Small Airway Dysfunction (SAD) parameters were observed only in males, not in females. This suggests a disproportionate risk for the male population.

An important and impactful study by Ural et al. (2022) demonstrates that lifelong exposure to environmental pollutants leads to the accumulation of inhaled atmospheric particulate matter in lung-associated lymph nodes (LNs). This accumulation is most noticeable in individuals aged 40 and above and is higher in males than in females.

Large-scale research dedicated to “the global burden of lower respiratory infections and risk factors” (GBD 2019 LRI Collaborators, 2022) indirectly confirms these patterns and causal relationships. In 2019, there were an estimated 257 million lower respiratory infection (LRI) incidents in males and 232 million in females globally. LRIs accounted for 1.30 million male deaths and 1.20 million female deaths. The highest increase in LRI episodes and mortality was observed in men aged 70 and older from 1990 to 2019. Age-standardized incidence and mortality rates were greater in males than in females. A significant portion of infections and mortality is also linked to air pollution.

4.3. Age-Related Nasal Morphology and Associated Functionality

Age is the primary factor influencing intranasal volumes. For children under 17, the average dynamics of changes in intranasal spaces reflect the development of the respiratory system with age. The age range of 16–20 years marks the threshold when the geometric parameters of the respiratory system become similar to those of adults (Samolinski et al., 2007). Additionally, intranasal volumes are generally higher in men than in women, with a statistically significant increase in intranasal volume observed with age in both sexes (Golshahi & Hosseini, 2019; Maréchal et al., 2023).

Ganjaei et al. (2019) measured nasal volumes on computed tomography (CT) scans, dividing the subjects into two cohorts (18–34 and 80–99 years old). They found that older subjects have a global increase in intranasal volumes. Individual nasal cavity volumes increased by 17–75% with age (p < 0.05 for most volumes). Regression analysis of all scans revealed that age is the predominant variable influencing intranasal volume differences when controlling for sex and head size (p < 0.05).

Another study by Loftus et al. (2016) examined sixty-two CT scans and noted a progressive, relatively linear increase in intranasal volume with age: 20 to 30 years = 15.73 mL, 40 to 50 years = 17.30 mL, and 70 years and above = 18.38 mL. The mean intranasal volume for males was 19.07 mL, and for females, it was 15.23 mL, with no significant variation based on body mass index.

Additionally, Xu et al. (2019) demonstrated that nasal cavity volume significantly increased and nasal resistance decreased with age in 180 healthy Korean-speaking adult volunteers without nasal or voice-related complaints.

Therefore, based on the conclusions from the previous sections, the age-related increase in nasal volumes and decrease in nasal resistance in the elderly should lead to a decline in the nose’s ability to filter and condition inhaled air.

(Nasal Air Filtration)

While direct measurements and comparisons of nasal filtration abilities in elderly individuals are not readily available in the literature, there is clear evidence of significant changes in nasal filtration capacity across different age groups, from childhood to adulthood (Cheng et al., 1995; Golshahi & Hosseini, 2019; Zhou et al., 2013). These changes highlight general patterns in the nose’s filtration capacity, which are linked to the characteristics of nasal passages and the associated function of pressure drop in the nose.

The deposition of micrometer-sized particles, with aerodynamic diameters ranging from 0.5 to 5.3 μm, was measured in nasal models across three age groups using sinusoidal breathing patterns. For this size range and inhalation flow rates, the nasal deposition data suggests deposition fractions of up to 60%, 80%, and 90% for adults, children, and infants, respectively (Golshahi et al., 2011; Golshahi & Hosseini, 2019; Storey-Bishoff et al., 2008).

These findings indicate that the nose’s protective capacity diminishes with age due to changes in nasal morphology. Specifically, increases in nasal volume and decreases in nasal resistance among the elderly could lead to a further decline in the nose’s filtering ability.

(Nasal Air Conditioning)

The older population is known to experience atrophy of the nasal mucosa and loss of nasal structural integrity. These changes are thought to contribute to several clinical complaints, including rhinorrhea, dry mucus, and the paradoxical sensation of congestion (Pinto and Jeswani, 2010; Settipane and Kaliner, 2013; Ganjaei et al., 2019).

Age-related anatomical changes in the nose can directly affect its ability to condition air (Wolf et al., 2004). Studies have shown that endonasal changes in the elderly, such as a gradual increase in cavity volume presumably caused by mucous membrane atrophy, can reduce the efficiency of heat and vapor transfer (Kalmovich et al., 2005; Worley et al., 2019).

Lindemann et al. (2008) demonstrated that nasal complaints in elderly patients result from impaired intranasal air conditioning due to decreased heat and water exchange. The study included forty participants. In the study group (median age, 70 years; range, 61–84), the median end-inspiratory air temperature (°C)/absolute humidity (g/m³) values were 24.0 °C/13.8 g/m³ within the nasal valve region and 24.3 °C/14.7 g/m³ anterior to the head of the middle turbinate. In the control group (median age, 27 years; range, 20–40), the corresponding values were 27.0 °C/15.5 g/m³ and 26.7 °C/17.0 g/m³. The temperature and humidity values were significantly lower in the study group (P < 0.05). The minimum cross-sectional areas and volumes were significantly higher in the study group (P < 0.05).

Furthermore, the increase in nasal volumes and the area of the nasal cross-section in the elderly contribute to poorer air conditioning. As demonstrated by Lindemann et al. (2009), these volumes and areas significantly impact nasal conditioning. A healthy nasal cavity with smaller volumes and a cross-sectional area conducts air conditioning more effectively than a nasal cavity that is too “wide” open, due to alterations in airflow.

Thus, the relatively enlarged nasal cavities and involution atrophy of the nasal mucosa in the elderly can lead to impaired intranasal air conditioning, air filtration problems, and an increased destructive impact of dry, cold, and polluted air on the airways. Consequently, the elderly may be at an increased risk of both upper and lower respiratory tract infections, being more susceptible to infectious aerosols and pollutants that can accumulate in the lower airways. This increased vulnerability could explain why the elderly face a higher risk of severe disease progression and death.

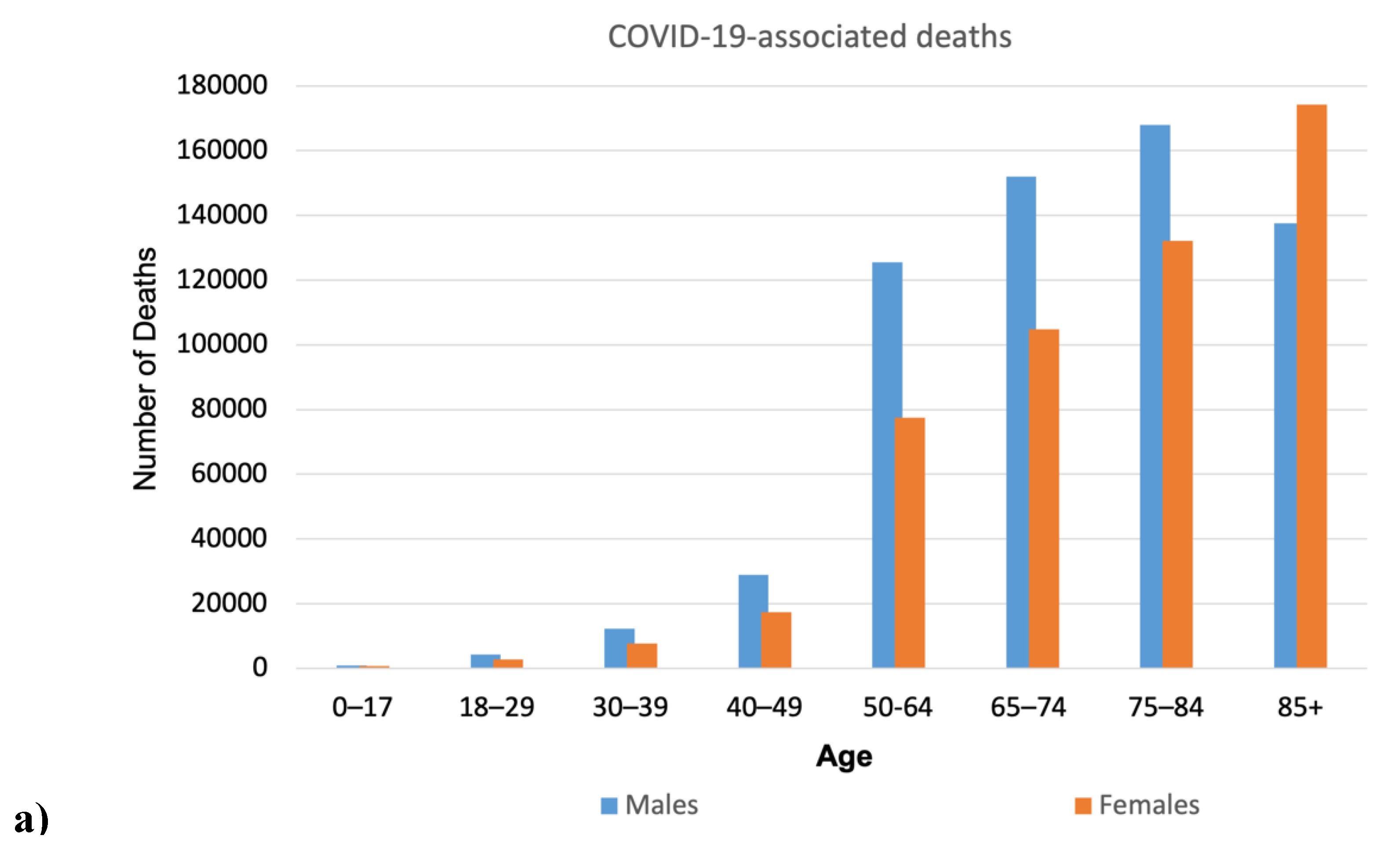

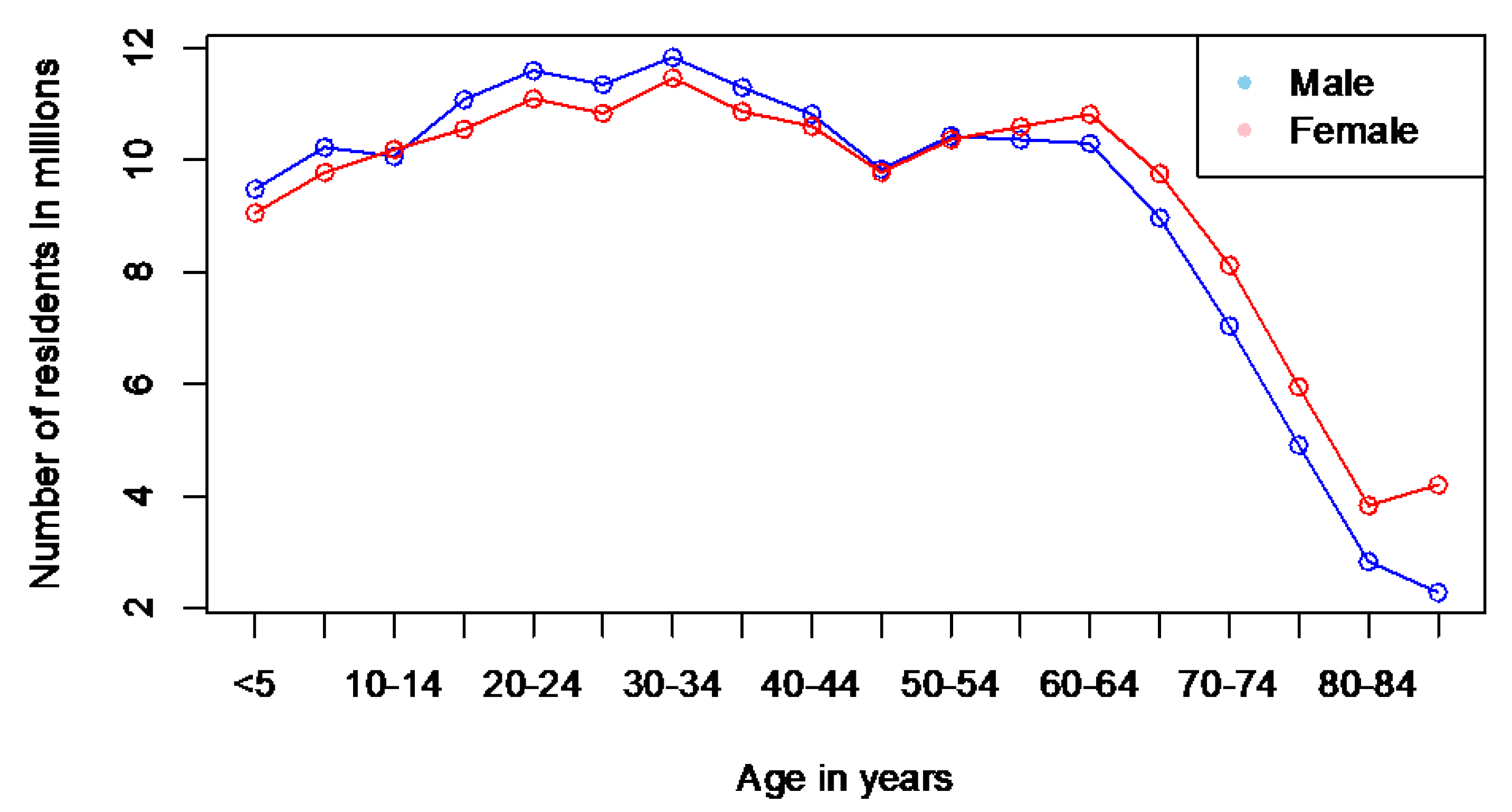

Figure 3 illustrates the differences in nasal volume across various age groups and genders. Additionally, it presents COVID-19 mortality data in the US during the pandemic from 2020 to 2023, divided by age and gender.

5. Summary and Discussion

The data in

Figure 3 illustrate the progressive enlargement of the nasal airway with age, showing a significant change in those over 50. This enlargement varies significantly between men and women. This increase correlates with the rise in COVID-19 related deaths in both sexes as they age. Furthermore, the age range of 16–20 years is when the geometric parameters of the respiratory system become similar to those of adults (Samolinski et al., 2007). Interestingly, the mortality rate begins to increase from the age of 18.

The observed relationships between nasal volumes and COVID-19 related deaths seem to be more correlative than causal, largely due to the various epidemic factors influencing the outcomes that must be considered. However, we cannot overlook that all identified changes in nasal morphology related to age and sex affect the nose’s ability to filter and condition air (refer to the discussion in previous sections). This, in turn, increases the burden on the respiratory system. In other words, based on the aforementioned arguments, we can expect that men’s noses are less efficient at filtering and conditioning air than women’s. Consequently, the burden on the respiratory system becomes greater, potentially explaining the observed differences. This coincides with the fact that COVID-19 mortality is higher in men than in women. Similarly, age-related changes in the nose are associated with a deterioration in nasal function and an increased burden on the respiratory system, resulting in increased mortality with age.

Thus, in addition to all other influencing factors, it is clear that age, gender, and racial changes in nasal morphology contribute to the burden of the disease. Furthermore, there is a direct mechanistic explanation related to the impact of cold, dry, dirty air, which is directly related to these changes in the nose.

5.1. Do Men with Wide Noses Have a Higher Mortality Rate from All Causes?

A surprising observation related to the resident population statistics of the United States, though not connected to COVID-19, can be made here.

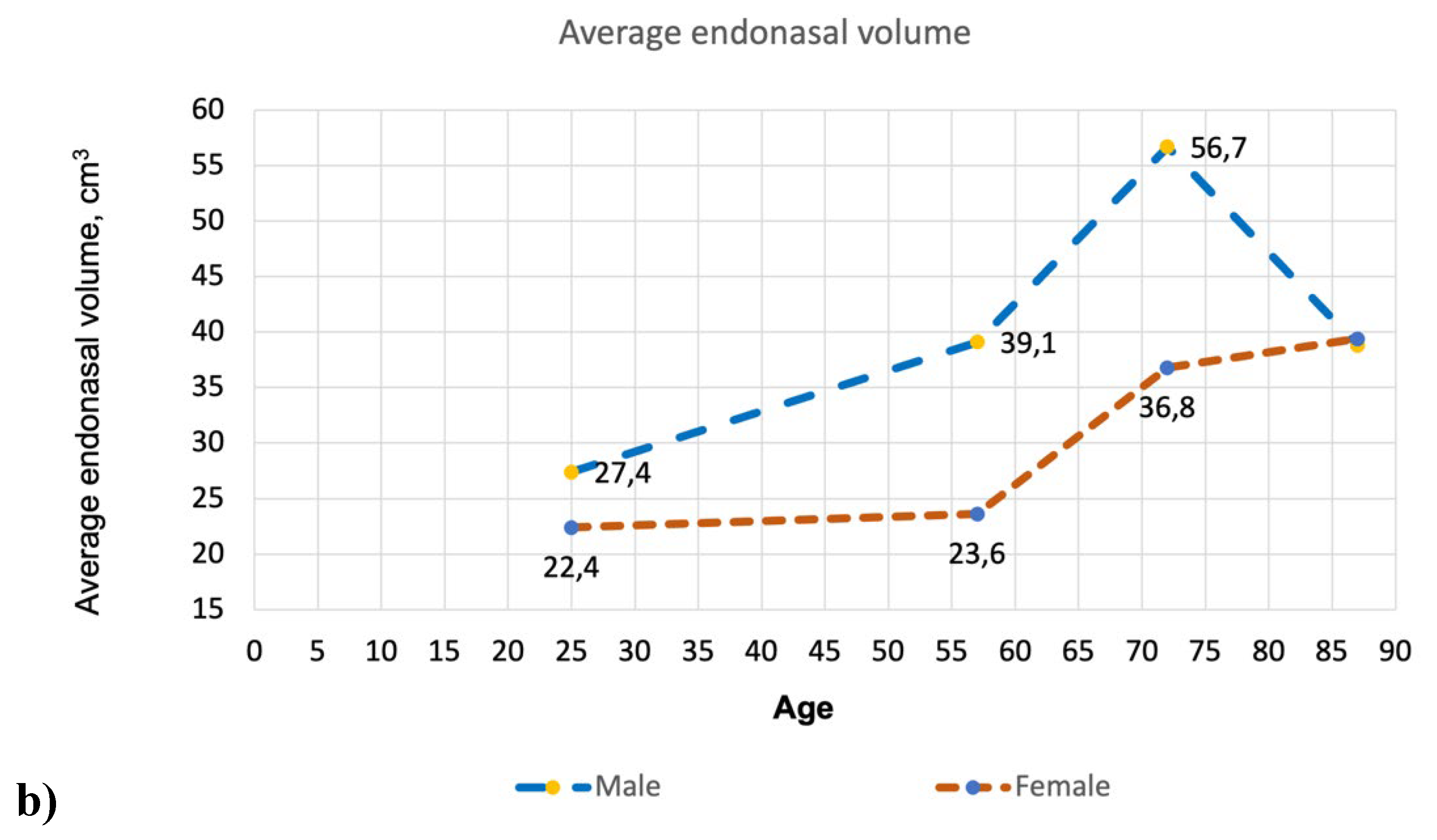

Figure 3b reveals a statistically significant increase in intranasal volume with age in both sexes, excluding the oldest male group. The intranasal volume in men over the age of 80 is significantly reduced and becomes comparable to the intranasal volume in women of the same age.

On the other hand, the COVID-19 mortality graph (

Figure 3a) reveals a notable trend: for men aged 80 and older, the mortality rates shift from an increase to a decrease, with numbers dropping significantly from 168,030 to 137,620. In contrast, mortality rates in women show a significant rise, marking the first instance in this age group where female mortality surpasses male mortality—reporting 137,620 male deaths compared to 174,243 female deaths. This clearly indicates a general disparity in average life expectancy between men and women—more women reach this age than men (see

Figure 4). The ratios of male and female groups by age up to 80 years are approximately the same, while the ratio in groups aged 85+ years is significantly different—there are 1.84 times more women than men.

Thus, considering all the above, the following preliminary hypothesis can be formulated:

Taking into account that fewer men survive compared to women over the age of 80 (excluding all causes of death except COVID-19), and that the endonasal volume in men at this age significantly reduces and becomes comparable to the endonasal volume in women, it suggests that men with relatively larger nasal cavities are more likely to die than men with narrower nasal cavities at this age (excluding all causes of death except COVID-19).

The data used for analyzing nose measurements in this study is admittedly limited, potentially providing an incomplete perspective. We relied on acoustic rhinometry data from 165 participants, sourced from the research conducted by Kalmovich et al. (2005). Unfortunately, more extensive data remains elusive, indicating that this area is under-researched and has many gaps.

Despite these limitations, we cannot overlook the significant reduction in nasal cavity volume observed in men aged 80 and older and its potential link to overall mortality. This finding necessitates further in-depth studies, emphasizing the need to expand our understanding of nose geometry and morphology.

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in the accumulation of extensive datasets from computed tomography in hospitals, as many patients underwent this procedure during this time. This data presents a valuable opportunity for studying the morphology and geometry of the respiratory tract and must be analyzed in future research. It paves the way for understanding how intersubject airway differences and external factors, such as air pollution, impact population health.

5.2. Puzzle Assembly

In previous sections, the analysis explored the relationship between external factors such as pollution, cold, and dry air and the epidemiology of COVID-19. It detailed the mechanisms that affect the respiratory system and the protective functions of the nose, emphasizing the significant interpersonal differences in nasal structures. Notably, key factors influencing nasal protection include the width, length, and volume of nasal passages, with age, gender, and genetic racial affiliation identified as primary elements contributing to these variations.

In this section, we provide a summary of the most critical aspects for conducting a final comparison and analysis. We highlight the key features of individual changes in the nose and outline their potential connections to COVID-19 and related mortality (see

Table 1).

As seen in

Table 1, there is a clear correlation between the nose’s ability to filter and condition air and the mortality associated with COVID-19—the worse the nose functions, the higher the mortality rate.

Considering age, the data suggests that elderly people’s noses perform their functions less effectively compared to those of adults and children. This correlates with the increased mortality rate from COVID-19 among the elderly. However, it is important to recognize that this is also complicated by age-related characteristics of the immune system and the cumulative effects of air pollution throughout one’s life (see sections 2.2 and 4.3).

Regarding gender, the data suggests that men have wider nasal passages, which, according to physical principles, should lead to poorer filtration and conditioning of air compared to women. However, there is no reliable research yet that could confirm or refute this (see section 4.2). This correlates with higher COVID-19 mortality rates in males compared to females (see

Figure 3). Additionally, general trends in the deposition of inhaled particles in the airways complicate the situation. Experiments involving mouth-breathing show that men receive larger doses of air pollution in the lungs than women due to higher inhalation volumes and physiological parameters like functional residual capacity and tidal volume (Bennett et al., 1996; Voliotis and Samara, 2018).

In terms of race, people genetically originating from warm regions have noses that perform their functions less effectively—they have wider nasal passages compared to individuals from moderate and cold latitudes. This is genetically and evolutionarily determined. The effectiveness of noses by racial characteristics in filtration and conditioning is directly proven in the literature and corresponds to physical principles and logic (see sections 3.1 and 4.1). This correlates with higher COVID-19 mortality rates in races genetically originating from warm regions compared to other races (see

Figure 2). Additionally, minoritized and low-income populations in the US face disproportionate exposure to air pollution, with racially segregated communities experiencing higher concentrations of toxic particulate matter from human-made sources (Bell & Ebisu, 2012; Josey et al., 2023; Kodros et al., 2022; Mork et al., 2024).

Thus, the results highlight a correlation between nasal function and COVID-19 mortality, noting that poorer nasal filtration and conditioning are linked to higher mortality rates. These identified connections would benefit from further comprehensive study.

6. limitations and Future Directions

One significant limitation of this study is that it focused solely on examining the morphological features of the nose without considering its connection to the respiratory system. While variations in nasal morphology were explored, it is essential to acknowledge the corresponding differences in the structure and geometry of the respiratory tract, which are influenced by individual factors such as gender and age-related variations. These variations play a crucial role in shaping airflow patterns and determining the deposition of particulate matter within the respiratory tract.

For instance, aging impacts the diameter of human bronchioles, leading to alterations and restrictions in airflow among elderly individuals (Kim et al., 2017; Niewoehner and Kleinerman, 1974). Niewoehner and Kleinerman (1974) highlighted how the diameter of smaller airways (bronchioles <2 mm) narrows with age, particularly in individuals over 40 years old, with a noticeable 10% decrease in bronchioles observed in the age group of 50 to 80. Similarly, Islam et al. (2021a, b) delved into the effects of aging on airway geometry, revealing that smaller airways exhibit a higher rate of particle deposition. This phenomenon leads to alterations in the distribution and accumulation of inhaled particles in the bronchiolar region of the elderly population.

A comparative analysis of particle deposition between different age groups, conducted by Buonanno et al. (2011) and Man et al. (2022), showed an increasing trend in submicron particle doses in the lungs from children to adults and the elderly. This phenomenon can be attributed to varying physiological factors such as upper airway characteristics, functional residual capacity (FRC), and tidal volume (TV) (Brozek, 1960). Notably, elderly individuals were found to have the highest total dose of submicron particles in the airways, irrespective of hygroscopicity. Additionally, Islam et al. (2021b) using anatomical models of individuals aged 50, 60, and 70, demonstrated an age-related increase in aerosol deposition efficiency, particularly concerning infectious aerosols like SARS-CoV-2.

Moreover, it is crucial to recognize that factors influencing the aging process of the lower respiratory tract also impact the aging of the nose, and vice versa. Age-related nasal dysfunction can impose an additional burden on the respiratory system, potentially contributing to lung-related issues. Conversely, the elderly population exhibits a decline in forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume (FEV), and perfusion in the lower respiratory tract. Since nasal airflow is influenced by changes in FVC or FEV, any age-related alterations can directly impact the efficiency of the nose (Edelstein, 1996).

Although our study has provided some insights into the complex relationship between nasal morphology, respiratory tract structure, and aging-related changes, there is a need for further research to delve deeper into these connections. Future investigations should focus on exploring the interactions between nasal and respiratory system dynamics as a whole across varied demographic profiles. This will help in expanding our knowledge of age-related respiratory changes and their potential implications.

(Compromised airways)

Another significant area of research focuses on the impact of changes acquired during an individual’s lifetime in nasal airways and the respiratory tract. Any deviations or disturbances in the functioning, physiology, and structure of the nasal airways can lead to a decline in protective properties and various functional issues in both the nose and the entire respiratory system.

These disturbances may arise from direct interventions such as surgery or trauma, as well as from various diseases including infections, asthma, COPD, allergies, and viruses. Additionally, natural causes linked to individual characteristics can contribute to these issues. It is essential to recognize that any factors disrupting or limiting the immunological activity of the nasal mucosa and respiratory tract can compromise protective mechanisms.

For instance, respiratory viruses like SARS-CoV-2 target cells responsible for mucus secretion and mucociliary clearance, thereby diminishing the functionality of the nose and respiratory system. This impairment hinders the system’s ability to filter and condition inhaled air, making it more vulnerable to external influences. Therefore, understanding the role of disparities in nasal morphology becomes crucial, especially when the respiratory system is compromised, such as during infections of the upper airway and nasal epithelial cells. In such situations, even minor external factors can have severe implications for disease progression (see the relevant review in Hossain et al., 2024; Liang & Yuan, 2022; Ishmatov et al., 2024).

Moreover, the structural and morphological characteristics of the respiratory system are influenced not only by age, gender, race, and other individual traits but also by the effects of respiratory viruses and pathogens. This interplay can significantly alter the impact of air pollutants and other environmental factors on the respiratory system, highlighting the necessity for comprehensive research in this area.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed significant global disparities, with factors such as cold and polluted air, older age, sex, and race playing crucial roles in disease severity. Nasal airway structures and their physiological functions significantly impact susceptibility to respiratory infections, including SARS-CoV-2. The nose’s defense mechanisms for the respiratory system are influenced by individual characteristics, along with race-, sex-, and age-related morphological variations. These factors affect nasal functions such as air conditioning and filtration, resulting in differences in respiratory protection.

Analysis suggests that individuals with genetically wider nasal cavities, typically found in populations from warmer climates, experience decreased filtration and air conditioning efficiency. This inefficiency can lead to increased susceptibility to respiratory infections, including COVID-19. Additionally, age-related changes in nasal morphology, such as increased nasal volume and involution atrophy of the mucosa, contribute to impaired air conditioning and filtration, elevating the risk of severe outcomes among the elderly.

Gender differences in nasal morphology further complicate the picture; men generally have larger nasal passages than women, which may correlate with poorer air conditioning and filtration. This difference could help explain the higher risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes observed in men. Notably, preliminary data suggests that men with smaller nasal passages may have longer lifespans compared to those with larger passages; however, this claim requires further validation.

Despite decades, and even centuries, of research, significant knowledge gaps regarding nasal functionalities remain. It is evident that further comprehensive research is necessary to bridge these gaps. Analyzing extensive amounts of raw data from medical scans and histories will enhance our understanding and inform future public health strategies. Such research will deepen our insights into the complex interplay of biological, environmental, and socioeconomic factors that influence COVID-19 outcomes.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. All current expenses were covered by the personal funds of the project leader (I.A.N.).

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to Prof. Larisa Gorina (TitSU) and David Williams from The Proof & Edit Company (UK) for their support and valuable tips at the beginning of the research. I also extend my thanks to ACS Authoring Services (American Chemical Society) for proofreading and editing the first draft of this text and for allowing me to use their services without charge during the pandemic period.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

All data and materials are included in this article.

Competing Interests

I report no competing interests.

Authors’ Contributions

All contributions were made by Alexander Ishmatov. The author wrote and read and approved the manuscript.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

Statement: During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used “Notion AI” and “ChatGPT—OpenAI” to check the text’s grammar and spelling. “RECRAFT.AI” (Recraft Inc.) and “Fusionbrain.ai” were partially used to create images for graphical highlights. After using these services, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the publication’s content.

Abbreviations

AH—Absolute Humidity;

RH—Relative Humidity;

BMR—Basal Metabolic Rate

COPD—Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

COVID-19—Coronavirus Disease 2019

DEP—Diesel Exhaust Particles

EV—Extracellular Vesicle

FEV—Forced Expiratory Volume

FRC—Functional Residual Capacity

FVC—Forced Vital Capacity

ICU—Intensive Care Unit

LN—Lymph Node

LRI—Lower Respiratory Infection

NA—Nasal Airway

NR—Nasal Resistance

PM—Particulate Matter

PM1—Particulate Matter with an aerodynamic diameter less than 1 micrometer

PM10—Particulate Matter with an aerodynamic diameter less than 10 micrometers

PM2.5—Particulate Matter with an aerodynamic diameter less than 2.5 micrometers

SARS—Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome

SARS-CoV-2—Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2

TLR3—Toll-like Receptor 3

TV—Tidal Volume

UK—United Kingdom;

U.S.—United States;

References

- Aburto, J. M., Tilstra, A. M., Floridi, G., & Dowd, J. B. (2022). Significant impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on race/ethnic differences in US mortality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 119(35), e2205813119. [CrossRef]

- Akbar, A. N., & Gilroy, D. W. (2020). Aging immunity may exacerbate COVID-19. Science (New York, N.Y.), 369(6501), 256–257. [CrossRef]

- Aldridge, R. W., Lewer, D., Katikireddi, S. V., Mathur, R., Pathak, N., Burns, R., Fragaszy, E. B., Johnson, A. M., Devakumar, D., Abubakar, I., & Hayward, A. (2020). Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic groups in England are at increased risk of death from COVID-19: indirect standardisation of NHS mortality data. Wellcome open research, 5, 88. [CrossRef]

- Alidadi, M., Sharifi, A., & Murakami, D. (2023). Tokyo’s COVID-19: An urban perspective on factors influencing infection rates in a global city. Sustainable cities and society, 97, 104743. [CrossRef]

- Anand, U., Adelodun, B., Pivato, A., Suresh, S., Indari, O., Jakhmola, S., Jha, C. H., Jha, P. K., Tripathi, V., Di Maria, F. (2021). A review of the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater and airborne particulates and its use for virus spreading surveillance, Environ. Res,V. 196, 2021, 110929, . [CrossRef]

- Anand, U., Pal, T., Zanoletti, A., Sundaramurthy, S., Varjani, S., Rajapaksha, A. U., Barceló, D., & Bontempi, E. (2023). The spread of the omicron variant: Identification of knowledge gaps, virus diffusion modelling, and future research needs. Environmental research, 225, 115612. [CrossRef]

- Aral, N., & Bakir, H. (2022). Spatiotemporal Analysis of Covid-19 in Turkey. Sustainable cities and society, 76, 103421. [CrossRef]

- Assanasen, P., Baroody, F. M., Naureckas, E., Solway, J., & Naclerio, R. M. (2001). The nasal passage of subjects with asthma has a decreased ability to warm and humidify inspired air. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 164(9), 1640–1646. [CrossRef]

- Barakat, T., Muylkens, B., & Su, B. L. (2020). Is Particulate Matter of Air Pollution a Vector of Covid-19 Pandemic? Matter, 3(4), 977–980. [CrossRef]

- Bart, A.A., Strebkova, E.A., Yakovlev, S.V., Ishmatov, A.N. (2023). Assessment of the relationship between adverse weather conditions, Black Sky regime, and COVID-19 morbidity in Tomsk in 2022,” Proc. SPIE 12780, 29th International Symposium on Atmospheric and Ocean Optics: Atmospheric Physics, 127806G (17 October 2023); doi: 10.1117/12.2690936.

- Bartleson, J. M., Radenkovic, D., Covarrubias, A. J., Furman, D., Winer, D. A., & Verdin, E. (2021). SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19 and the Ageing Immune System. Nature aging, 1(9), 769–782. [CrossRef]

- Bastir, M., Megía, I., Torres-Tamayo, N., García-Martínez, D., Piqueras, F. M., & Burgos, M. (2020). Three-dimensional analysis of sexual dimorphism in the soft tissue morphology of the upper airways in a human population. American journal of physical anthropology, 171(1), 65–75. [CrossRef]

- Bayram, H., Konyalilar, N., Elci, M. A., Rajabi, H., Tuşe Aksoy, G., Mortazavi, D., Kayalar, Ö., Dikensoy, Ö., Taborda-Barata, L., & Viegi, G. (2024). Issue 4-Impact of air pollution on COVID-19 mortality and morbidity: An epidemiological and mechanistic review. Pulmonology, S2531-0437(24)00051-5. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Becquemin, M. H., Swift, D. L., Bouchikhi, A., Roy, M., & Teillac, A. (1991). Particle deposition and resistance in the noses of adults and children. The European respiratory journal, 4(6), 694–702. PMID: 1889496.

- Beentjes, D., Shears, R. K., French, N., Neill, D. R., & Kadioglu, A. (2022). Mechanistic Insights into the Impact of Air Pollution on Pneumococcal Pathogenesis and Transmission. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 206(9), 1070–1080. [CrossRef]

- Bell, M. L., & Ebisu, K. (2012). Environmental inequality in exposures to airborne particulate matter components in the United States. Environmental health perspectives, 120(12), 1699–1704. [CrossRef]

- Benita, F., Rebollar-Ruelas, L., & Gaytán-Alfaro, E. D. (2022). What have we learned about socioeconomic inequalities in the spread of COVID-19? A systematic review. Sustainable cities and society, 86, 104158. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W. D., Zeman, K. L., & Kim, C. (1996). Variability of fine particle deposition in healthy adults: effect of age and gender. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 153(5), 1641–1647. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W. D., & Zeman, K. L. (2005). Effect of Race on Fine Particle Deposition for Oral and Nasal Breathing. Inhalation Toxicology, 17(12), 641–648. [CrossRef]

- Bontempi E. (2020). Commercial exchanges instead of air pollution as possible origin of COVID-19 initial diffusion phase in Italy: More efforts are necessary to address interdisciplinary research. Environmental research, 188, 109775. [CrossRef]

- Bontempi, E., & Coccia, M. (2021). International trade as critical parameter of COVID-19 spread that outclasses demographic, economic, environmental, and pollution factors. Environmental research, 201, 111514. [CrossRef]

- Bourdrel, T., Annesi-Maesano, I., Alahmad, B., Maesano, C. N., & Bind, M. A. (2021). The impact of outdoor air pollution on COVID-19: a review of evidence from in vitro, animal, and human studies. Eur Respir Rev, 30(159), 200242. [CrossRef]

- Bozack, A., Pierre, S., DeFelice, N., Colicino, E., Jack, D., Chillrud, S. N., Rundle, A., Astua, A., Quinn, J. W., McGuinn, L., Yang, Q., Johnson, K., Masci, J., Lukban, L., Maru, D., & Lee, A. G. (2022). Long-Term Air Pollution Exposure and COVID-19 Mortality: A Patient-Level Analysis from New York City. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 205(6), 651–662. [CrossRef]

- Bronte, O., García-García, F., Lee, D. J., Urrutia, I., Uranga, A., Nieves, M., Martínez-Minaya, J., Quintana, J. M., Arostegui, I., Zalacain, R., Ruiz-Iturriaga, L. A., Serrano, L., Menéndez, R., Méndez, R., Torres, A., Cilloniz, C., España, P. P., & COVID-19 & Air Pollution Working Group (2023). Impact of outdoor air pollution on severity and mortality in COVID-19 pneumonia. The Science of the total environment, 894, 164877. [CrossRef]

- Brozek J. (1960). Age differences in residual lung volume and vital capacity of normal individuals. J Gerontol. 15:155-160. [CrossRef]

- Buonanno, G., Giovinco, G., Morawska, L., & Stabile, L. (2011). Tracheobronchial and alveolar dose of submicrometer particles for different population age groups in Italy. Atmospheric Environment, 45(34), 6216-6224. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y., Chen, M., Dong, D., Xie, S., Liu, M., 2020. Environmental pollutants damage airway epithelial cell cilia: implications for the prevention of obstructive lung diseases. Thorac Cancer 11 (3), 505e510. [CrossRef]

- Carabelli, A. M., Peacock, T. P., Thorne, L. G., Harvey, W. T., Hughes, J., COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium, Peacock, S. J., Barclay, W. S., de Silva, T. I., Towers, G. J., & Robertson, D. L. (2023). SARS-CoV-2 variant biology: immune escape, transmission and fitness. Nature reviews. Microbiology, 21(3), 162–177. [CrossRef]

- Champlin, C., Sirenko, M., & Comes, T. (2023). Measuring social resilience in cities: An exploratory spatio-temporal analysis of activity routines in urban spaces during Covid-19. Cities, 135, 104220. [CrossRef]

- Chivé, C., Martίn-Faivre, L., Eon-Bertho, A., Alwardini, C., Degrouard, J., Albinet, A., Noyalet, G., Chevaillier, S., Maisonneuve, F., Sallenave, J. M., Devineau, S., Michoud, V., Garcia-Verdugo, I., & Baeza-Squiban, A. (2024). Exposure to PM2.5modulate the pro-inflammatory and interferon responses against influenza virus infection in a human 3D bronchial epithelium model. Environmental pollution (Barking, Essex: 1987), 348, 123781. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.S., Smith, S. M., Yeh, H.C., Kim, D.B., Cheng, K.H., Swift. D. L. (1995). Deposition of Ultrafine Aerosols and Thoron Progeny in Replicas of Nasal Airways of Young Children, Aerosol Sci Technol, 23:4, 541-552. [CrossRef]

- Christophi, C. A., Sotos-Prieto, M., Lan, F. Y., Delgado-Velandia, M., Efthymiou, V., Gaviola, G. C., Hadjivasilis, A., Hsu, Y. T., Kyprianou, A., Lidoriki, I., Wei, C. F., Rodriguez-Artalejo, F., & Kales, S. N. (2021). Ambient temperature and subsequent COVID-19 mortality in the OECD countries and individual United States. Scientific reports, 11(1), 8710. [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z., Cheng, M., & Song, M. (2021). What determines urban resilience against COVID-19: City size or governance capacity?. Sustainable cities and society, 75, 103304. [CrossRef]

- Churchill, S. E., Shackelford, L. L., Georgi, J. N., Black, M. T. (2004). Morphological variation and airflow dynamics in the human nose. Am J Hum Biol.;16: 625–638. pmid:15495233. [CrossRef]

- Clary-Meinesz, C. F., Cosson, J., Huitorel, P., & Blaive, B. (1992). Temperature effect on the ciliary beat frequency of human nasal and tracheal ciliated cells. Biology of the cell, 76(3), 335–338. [CrossRef]

- Conticini, E., Frediani, B., Caro, D. (2020). Can atmospheric pollution be considered a co-factor in extremely high level of SARS-CoV-2 lethality in Northern Italy? Environmental Pollution, 114465. [CrossRef]