Submitted:

06 August 2024

Posted:

06 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Neuroblastoma (NB)

1.2. Possible Extra-Genomic Therapeutic Approaches

1.3. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Instruments

2.2. BPPB Cytotoxicity Evaluation on NB Cells

2.2.1. Cell Culture Conditions

2.2.2. Treatments

2.2.3. Cell Viability Assay

2.2.4. Statistical Analyses

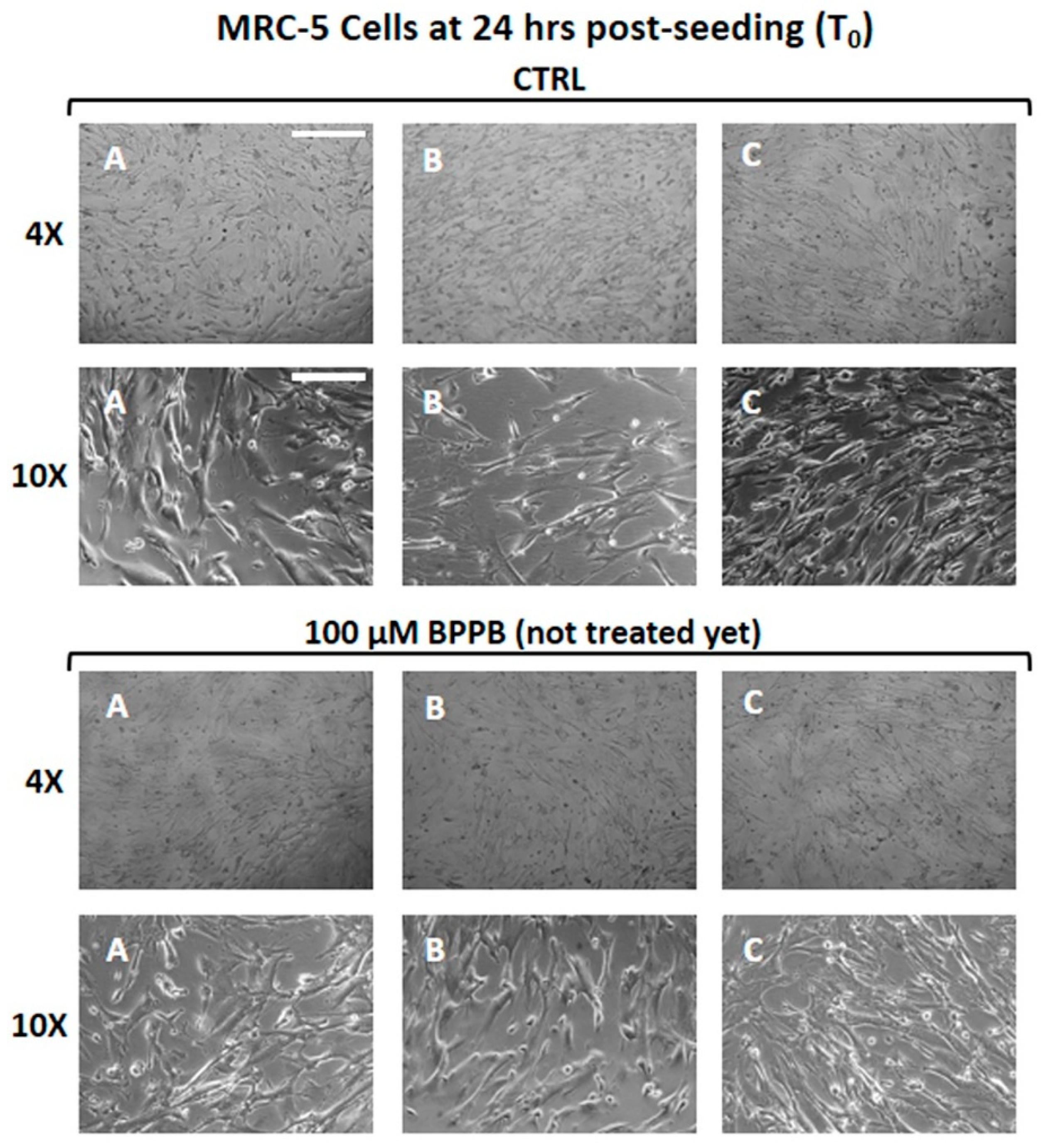

2.3. BPPB Cytotoxicity Evaluation on Human Lung Fibroblasts MRC-5

2.3.1. Cell Seeding Procedures and Treatments

2.3.2. Viability Test

2.4. Concentration-Dependent Cytotoxicity Experiments on Other Mammalian Cells

2.4.1. MTT Cytotoxicity Assay on Cos-7 and HepG2 Cells

2.4.2. LDH Cytotoxicity Assay on Cos-7 and HepG2 Cells

2.4.4. Statistics

2.5. Hemolytic Toxicity of BPPB Using Red Blood Cells (RBCs)

2.5.1. Hemolysis

3. Results and Discussion

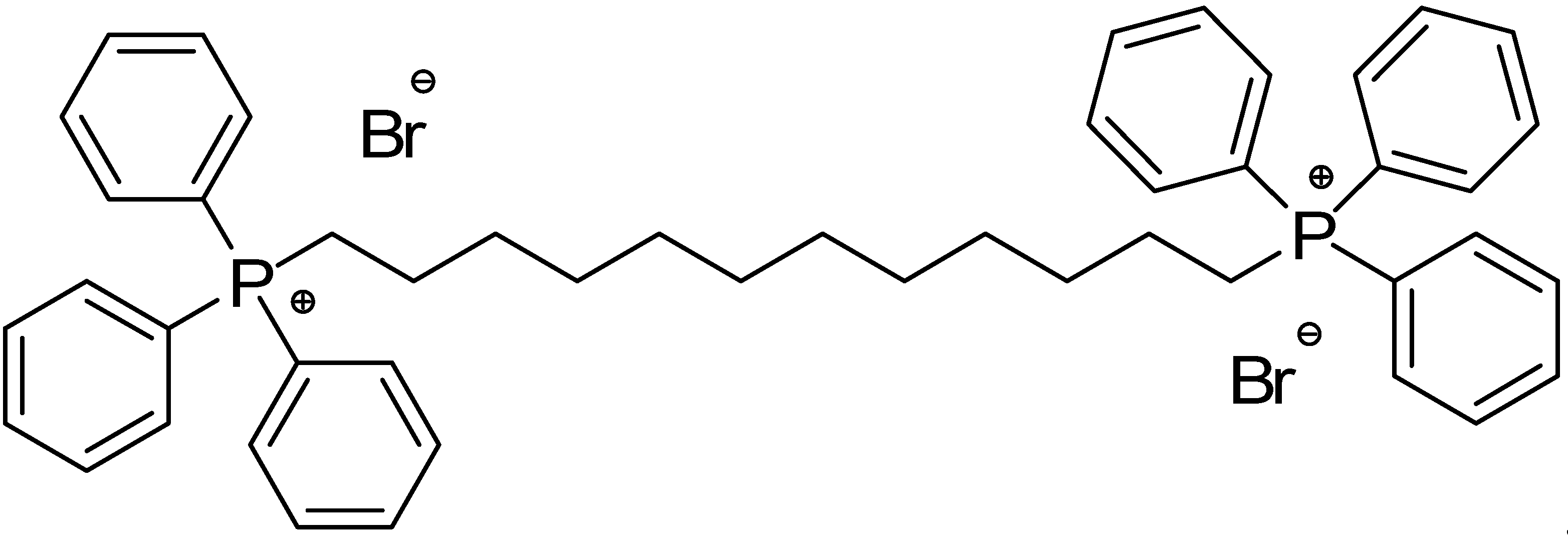

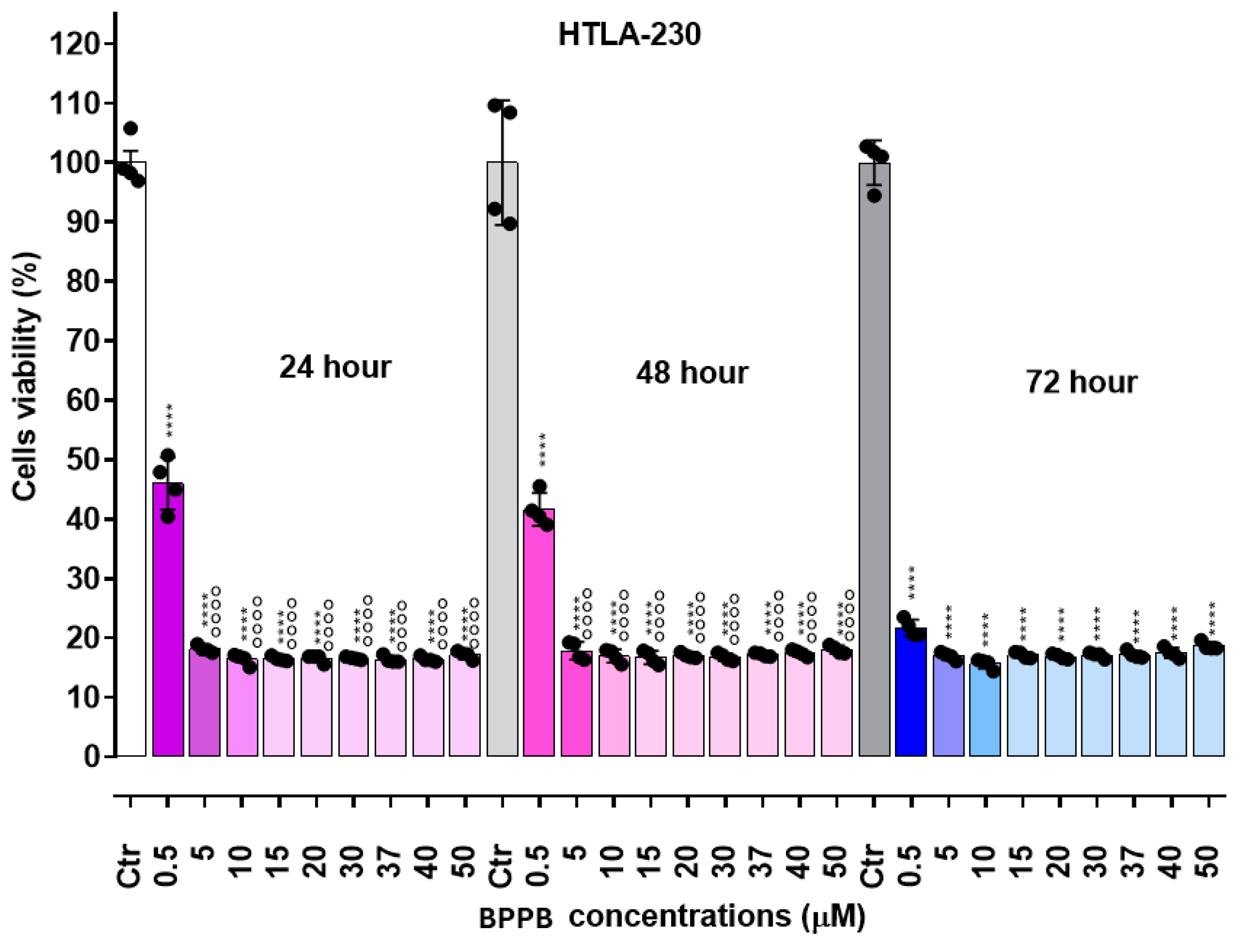

3.1. 1,1-(1,12-dodecanediyl)bis[1,1,1]-triphenylphosphonium di-Bromide (BPPB)

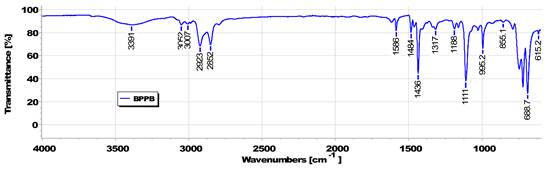

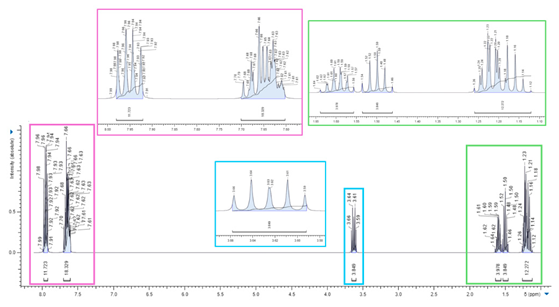

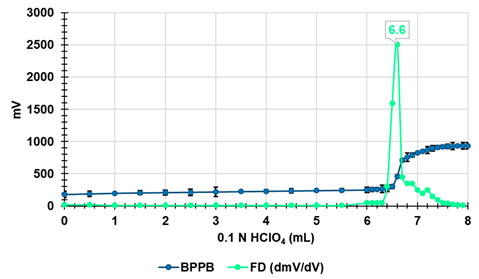

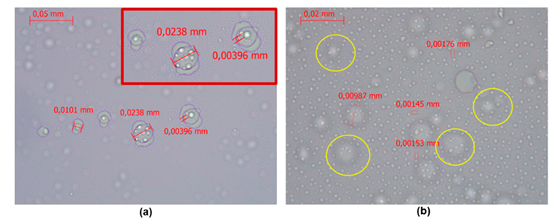

3.1.1. BPPB Characterization

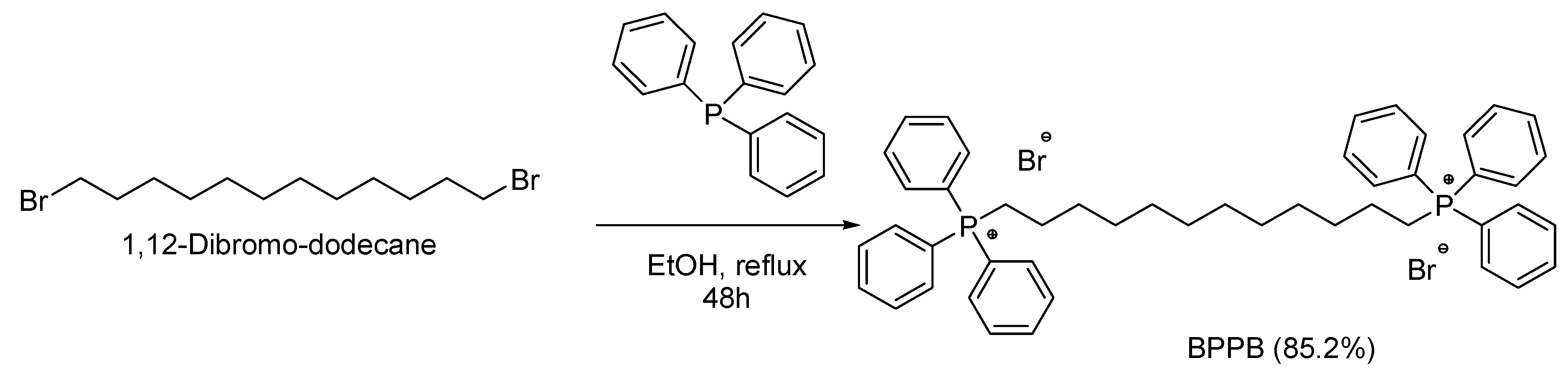

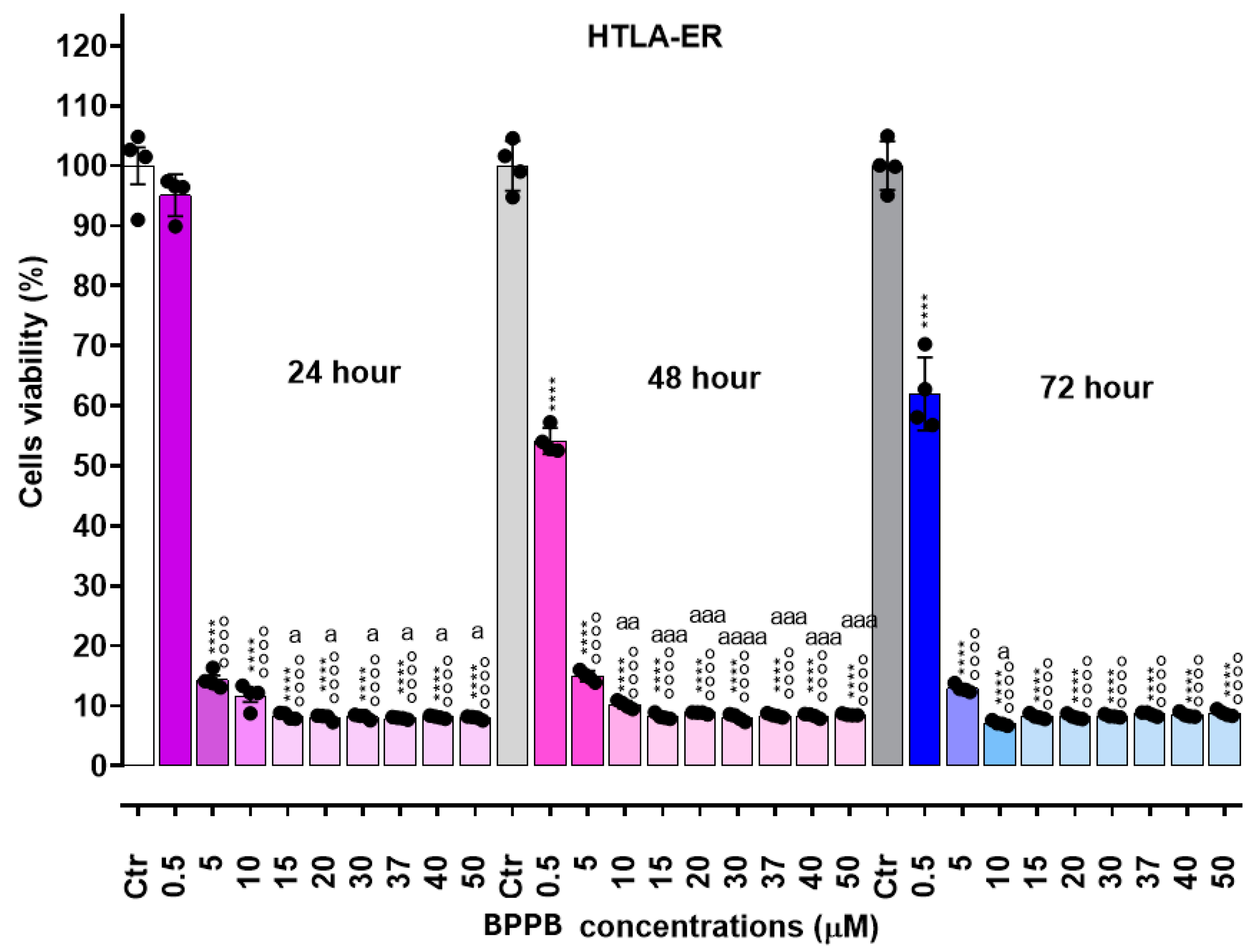

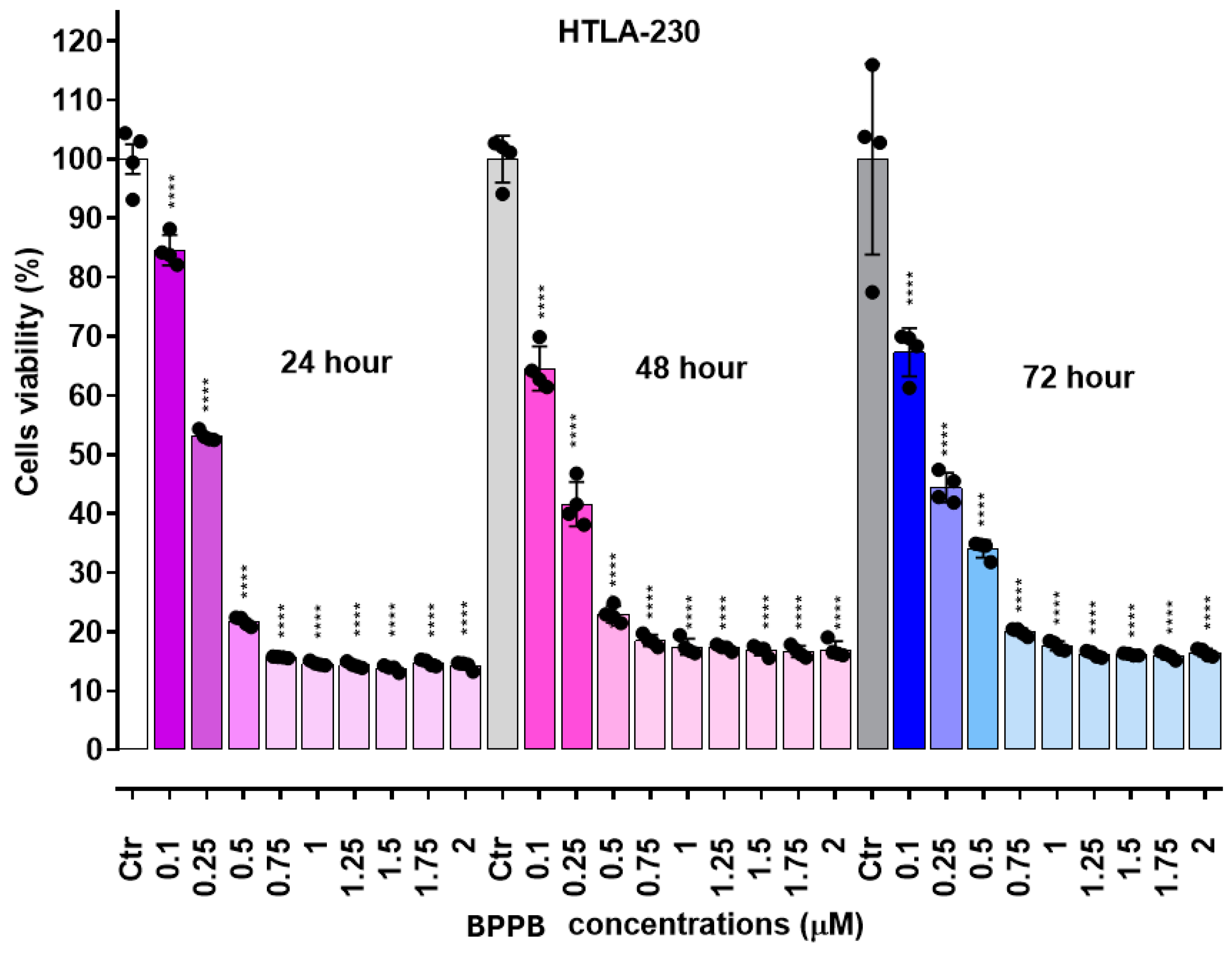

3.2. Concentration-and Time-Dependent Cytotoxic Effects of BPPB on Neuroblastoma (NB) Cells

3.2.1. Concentration-and Time-Dependent Cytotoxic Effects of BPPB on NB Cells

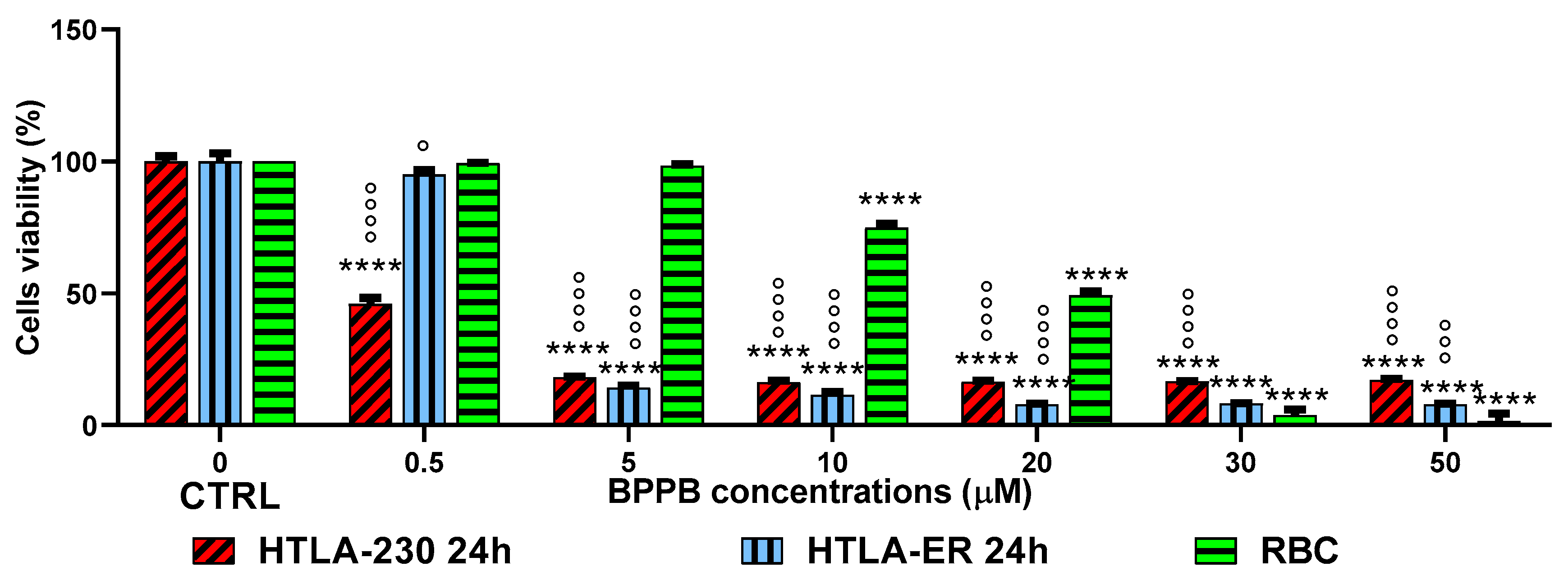

3.3. Evaluation of the Effects of BPPB on Different Not Tumoral Cells and Red Blood Cells

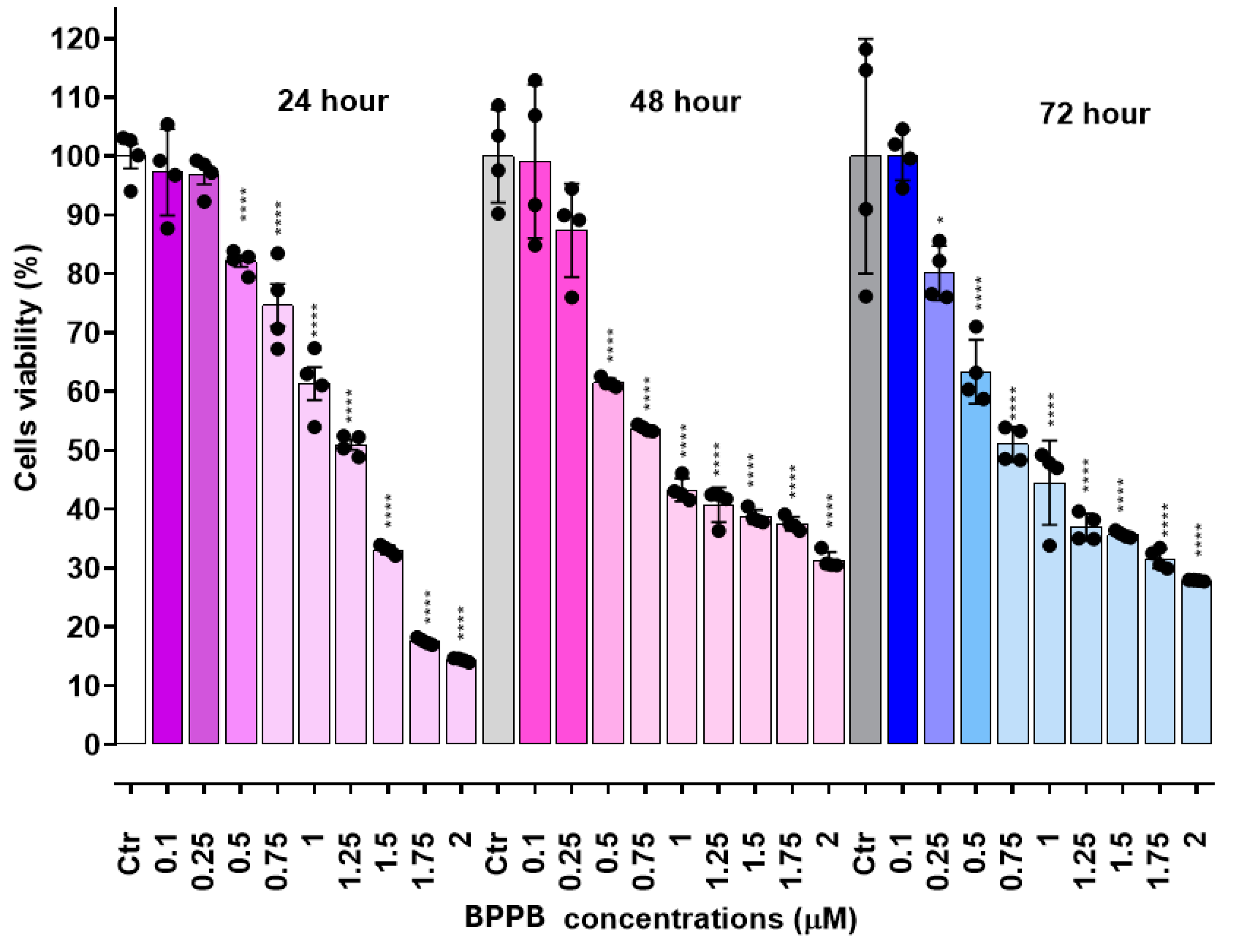

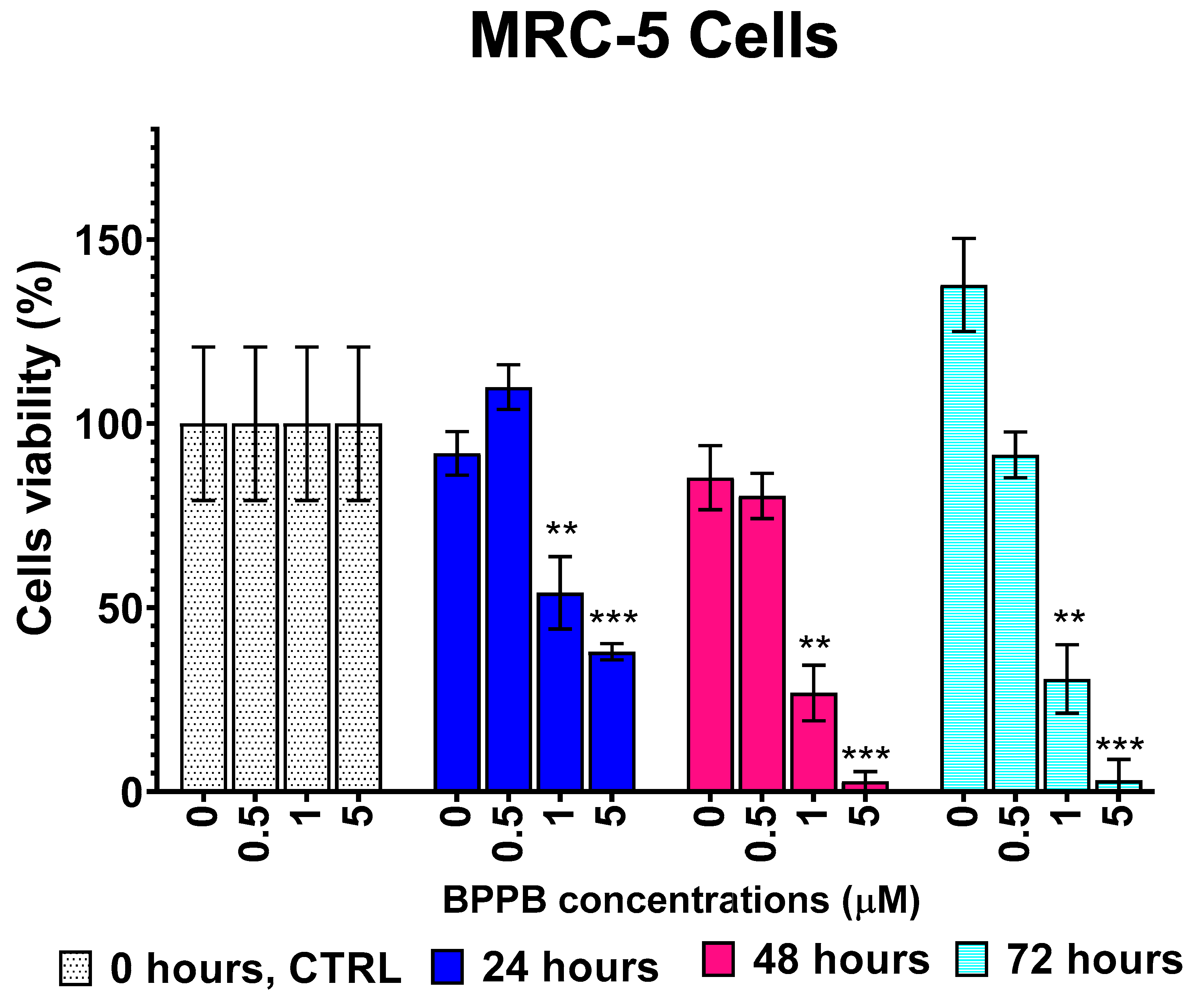

3.3.1. Evaluation of the Concentration- and Time-Dependent Effects of BPPB on Human Lung Fibroblasts MRC-5

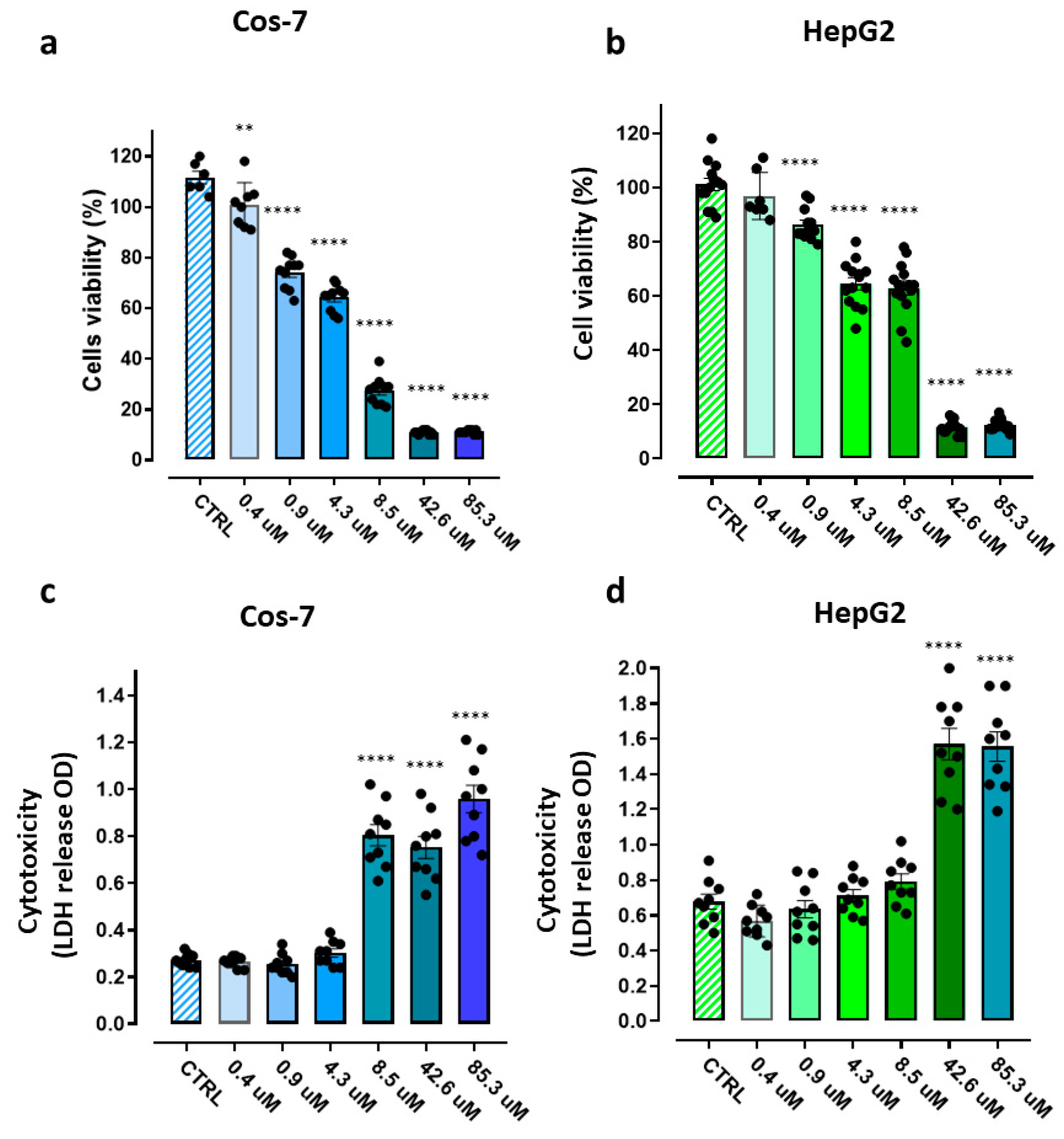

3.3.2. Assessment of the BPPB Concentration-Dependent Effects on Cos-7 and HepG2 Cells by MTT and LDH Essays

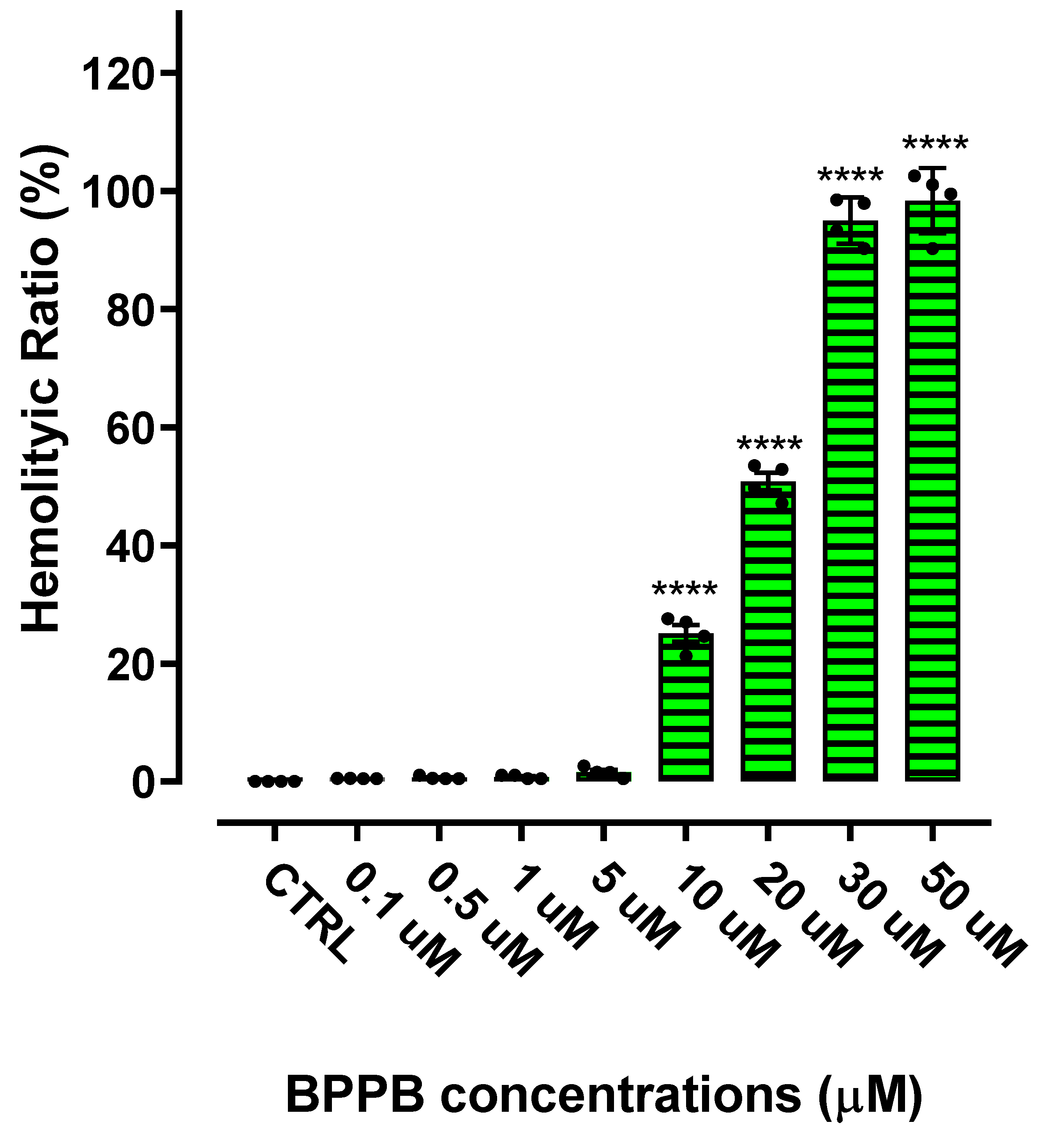

3.3.3. Hemolytic Toxicity of BPPB on Red Blood Cells (RBC)

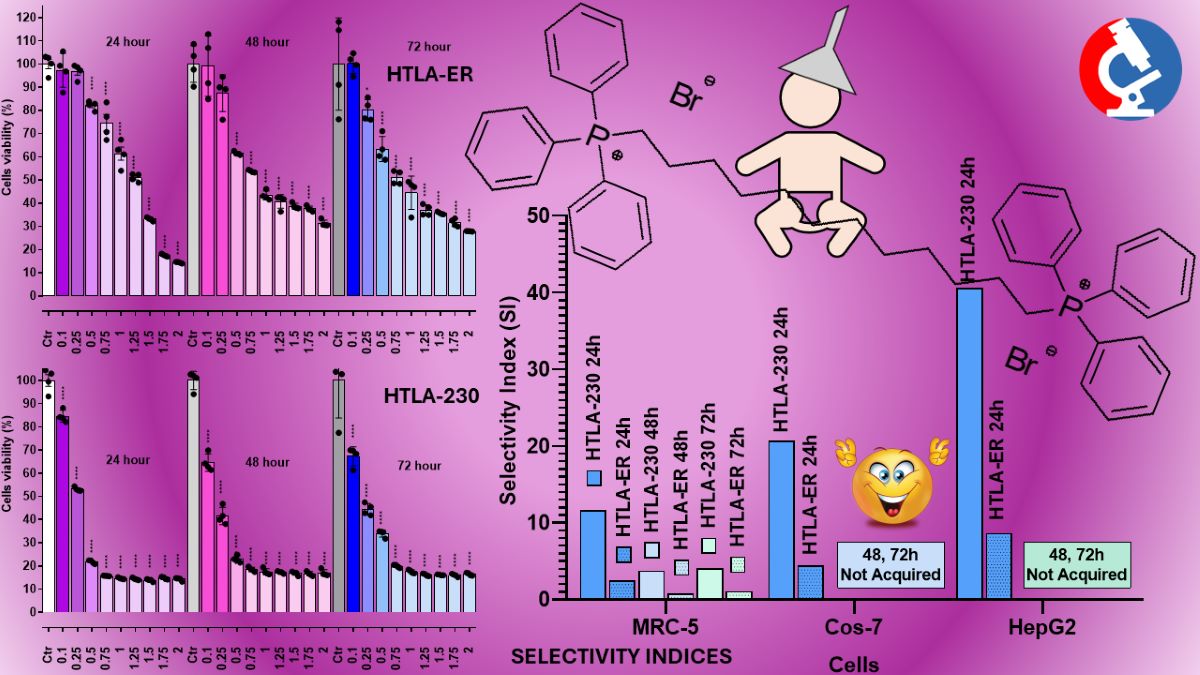

3.4. Selectivity Indices

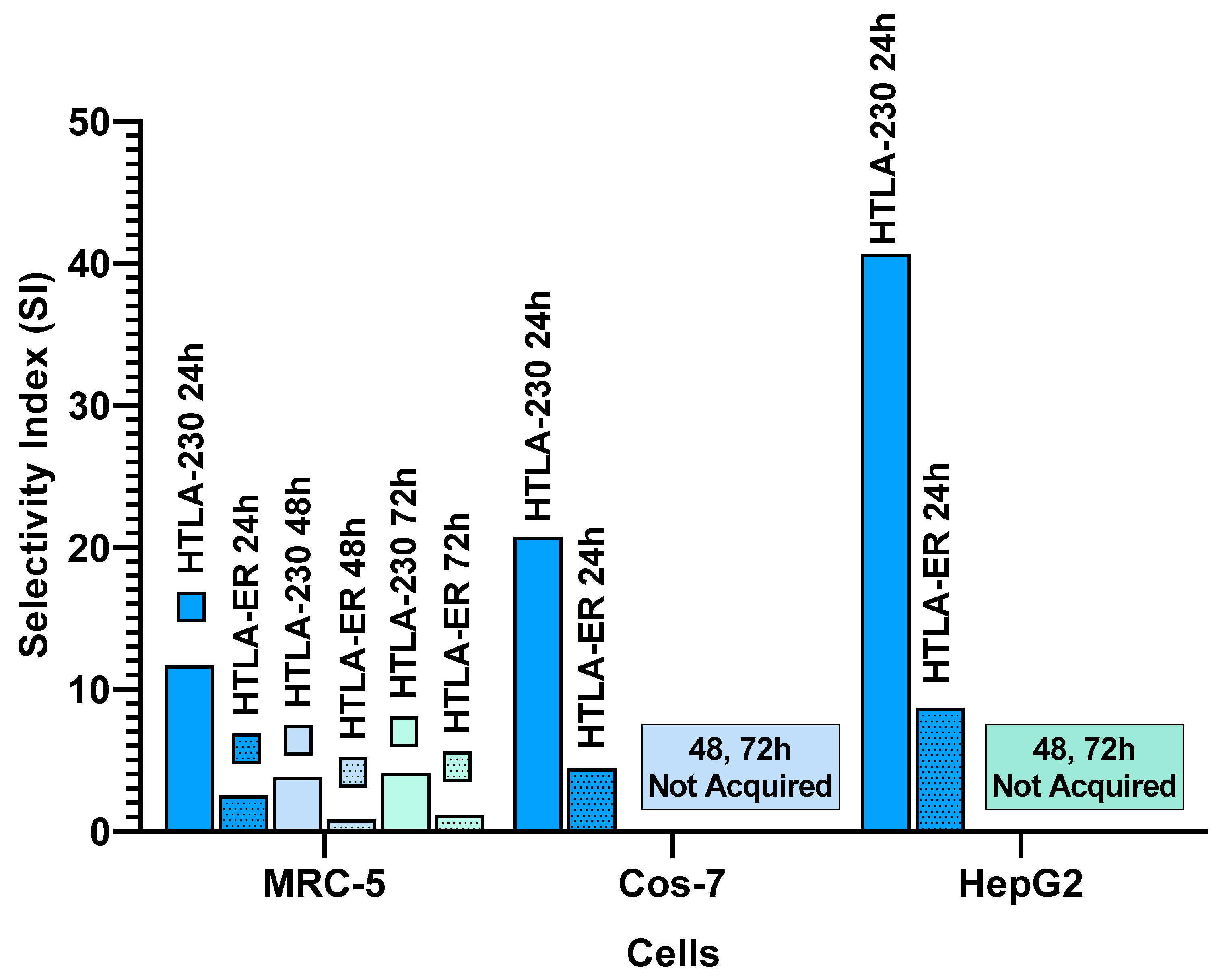

3.4.1. Selectivity Indices Towards MRC-5, Cos-7 and HepG2 Cells

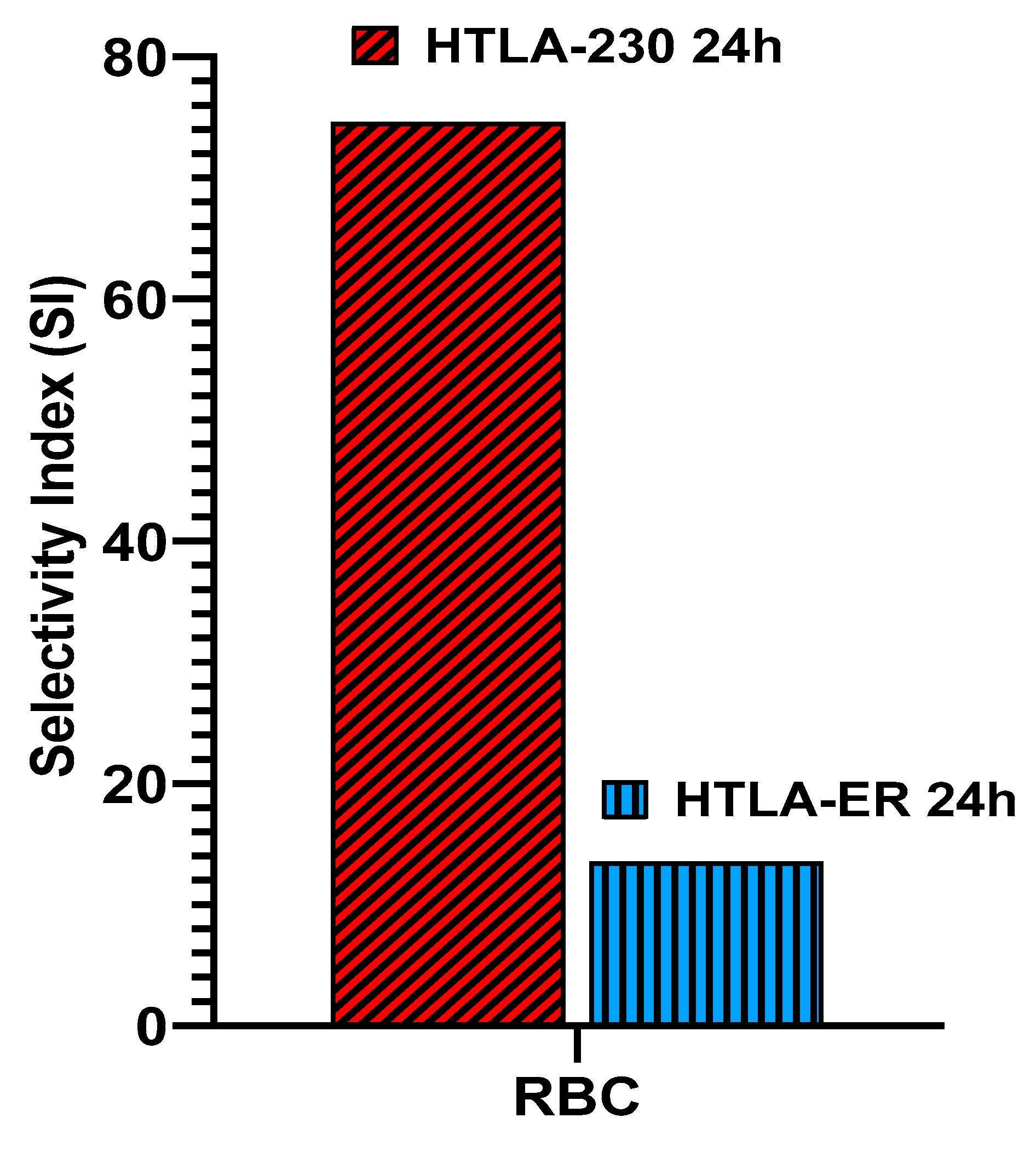

3.4.2. Selectivity Indices Towards RBCs

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cullinane, C.J.; Burchill, S.A.; Squire, J.A.; O’leary, J.J.; Lewis, I.J. Molecular Biology and Pathology of Paediatric Cancer; Oxford University PressNew York, NY, 2003; ISBN 9780192630797.

- Wilson, L.M.K.; Draper, G.J. Neuroblastoma, Its Natural History and Prognosis: A Study of 487 Cases. BMJ 1974, 3, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paraboschi, I.; Privitera, L.; Kramer-Marek, G.; Anderson, J.; Giuliani, S. Novel Treatments and Technologies Applied to the Cure of Neuroblastoma. Children 2021, 8, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerges, A.; Canning, U. Neuroblastoma and Its Target Therapies: A Medicinal Chemistry Review. ChemMedChem 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.H.; Ghosh, B.; Rizvi, M.A.; Ali, M.; Kaur, L.; Mondal, A.C. Neural Crest Cells Development and Neuroblastoma Progression: Role of Wnt Signaling. J Cell Physiol 2023, 238, 306–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speleman, F.; Park, J.R.; Henderson, T.O. Neuroblastoma: A Tough Nut to Crack. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book 2016, e548–e557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, H.; Ikegaki, N. Neuroblastoma Pathology and Classification for Precision Prognosis and Therapy Stratification. In Neuroblastoma; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 1–22.

- Molecular Basis and Clinical Features of Neuroblastoma. JMA J 2021, 4. [CrossRef]

- Klebe, S.; Leigh, J.; Henderson, D.W.; Nurminen, M. Asbestos, Smoking and Lung Cancer: An Update. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 17, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strother, D.R.; London, W.B.; Schmidt, M. Lou; Brodeur, G.M.; Shimada, H.; Thorner, P.; Collins, M.H.; Tagge, E.; Adkins, S.; Reynolds, C.P.; et al. Outcome After Surgery Alone or With Restricted Use of Chemotherapy for Patients With Low-Risk Neuroblastoma: Results of Children’s Oncology Group Study P9641. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2012, 30, 1842–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inomistova, M.; Khranovska, N.; Skachkova, O. Role of Genetic and Epigenetic Alterations in Pathogenesis of Neuroblastoma. In Neuroblastoma; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 23–41.

- Matthay, K.K.; Maris, J.M.; Schleiermacher, G.; Nakagawara, A.; Mackall, C.L.; Diller, L.; Weiss, W.A. Neuroblastoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016, 2, 16078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, J.; Castañeda, A.; Flores, M.A.; Santa-María, V.; Garraus, M.; Gorostegui, M.; Simao, M.; Perez-Jaume, S.; Mañe, S. The Role of Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation in High-Risk Neuroblastoma Consolidated by Anti-GD2 Immunotherapy. Results of Two Consecutive Studies. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoopathi, P.; Mannangatti, P.; Emdad, L.; Das, S.K.; Fisher, P.B. The Quest to Develop an Effective Therapy for Neuroblastoma. J Cell Physiol 2021, 236, 7775–7791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brusnakov, M.; Golovchenko, O.; Velihina, Y.; Liavynets, O.; Zhirnov, V.; Brovarets, V. Evaluation of Anticancer Activity of 1,3-Oxazol-4-ylphosphonium Salts in Vitro. ChemMedChem 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dryden, M. Reactive Oxygen Species: A Novel Antimicrobial. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2018, 51, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfei, S.; Schito, G.C.; Schito, A.M.; Zuccari, G. ..Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)-Mediated Antibacterial Oxidative Therapies: Available Methods to Generate ROS and a Novel Option Proposal. IJMS, 2024; 2024051628. [Google Scholar]

- Dryden, M. Reactive Oxygen Therapy: A Novel Therapy in Soft Tissue Infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2017, 30, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Loenhout, J.; Peeters, M.; Bogaerts, A.; Smits, E.; Deben, C. Oxidative Stress-Inducing Anticancer Therapies: Taking a Closer Look at Their Immunomodulating Effects. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldea, I.; Giurgiu, L.; Teacoe, I.D.; Olteanu, D.E.; Olteanu, F.C.; Clichici, S.; Filip, G.A. Photodynamic Therapy in Melanoma - Where Do We Stand? Curr Med Chem 2019, 25, 5540–5563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, T.; Nishio, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Shimizu, T.; Li, X.-K.; Okita, H.; Kuroda, T. Photodynamic Therapy with 5-Aminolevulinic Acid: A New Diagnostic, Therapeutic, and Surgical Aid for Neuroblastoma. J Pediatr Surg 2022, 57, 1281–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Kataoka, H.; Mabuchi, M.; Sakuma, S.; Takahashi, S.; Tujii, R.; Akashi, H.; Ohi, H.; Yano, S.; Morita, A.; et al. Anticancer Effects of Novel Photodynamic Therapy with Glycoconjugated Chlorin for Gastric and Colon Cancer. Anticancer Res 2011, 31, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Liang, M.; Lei, Q.; Li, G.; Wu, S. The Current Status of Photodynamic Therapy in Cancer Treatment. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai, D.L.; Lee, J.; Nguyen, D.L.; Kim, Y.-P. Tailoring Photosensitive ROS for Advanced Photodynamic Therapy. Exp Mol Med 2021, 53, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.; Vidal, C.; Dey, S.; Zhang, L. Mitochondria Targeting as an Effective Strategy for Cancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Principle of Biology; 11 November.; 2021.

- Kulkarni, C.A.; Fink, B.D.; Gibbs, B.E.; Chheda, P.R.; Wu, M.; Sivitz, W.I.; Kerns, R.J. A Novel Triphenylphosphonium Carrier to Target Mitochondria without Uncoupling Oxidative Phosphorylation. J Med Chem 2021, 64, 662–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Feng, D.; Lv, J.; Cui, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L. Application Prospects of Triphenylphosphine-Based Mitochondria-Targeted Cancer Therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceccacci, F.; Sennato, S.; Rossi, E.; Proroga, R.; Sarti, S.; Diociaiuti, M.; Casciardi, S.; Mussi, V.; Ciogli, A.; Bordi, F.; et al. Aggregation Behaviour of Triphenylphosphonium Bolaamphiphiles. J Colloid Interface Sci 2018, 531, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severina, I.I.; Vyssokikh, M.Yu.; Pustovidko, A. V.; Simonyan, R.A.; Rokitskaya, T.I.; Skulachev, V.P. Effects of Lipophilic Dications on Planar Bilayer Phospholipid Membrane and Mitochondria. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 2007, 1767, 1164–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinovkin, R.A.; Zamyatnin, A.A. Mitochondria-Targeted Drugs. Curr Mol Pharmacol 2019, 12, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam-Vizi, V.; Chinopoulos, C. Bioenergetics and the Formation of Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2006, 27, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachowska, B.; Kazmierczak-Baranska, J.; Cieslak, M.; Nawrot, B.; Szczęsna, D.; Skalik, J.; Bałczewski, P. High Cytotoxic Activity of Phosphonium Salts and Their Complementary Selectivity towards HeLa and K562 Cancer Cells: Identification of Tri- n -butyl- n -hexadecylphosphonium Bromide as a Highly Potent Anti-HeLa Phosphonium Salt. ChemistryOpen 2012, 1, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuraje, N.; Bai, H.; Su, K. Bolaamphiphilic Molecules: Assembly and Applications. Prog Polym Sci 2013, 38, 302–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvana Alfei; Guendalina Zuccari; Francesca Bacchetti; Carola Torazza; Marco Milanese; Carlo Siciliano; Constantinos M. Athanassopoulos; Gabriella Piatti; Anna Maria Schito Synthesized Bis-Triphenyl Phosphonium-Based Nano Vesicles Have Potent and Selective Antibacterial Effects on Several Clinically Relevant Superbugs. Preprint, 2024; 2024070891. [CrossRef]

- Bacchetti, F.; Schito, A.M.; Milanese, M.; Castellaro, S.; Alfei, S. Anti Gram-Positive Bacteria Activity of Synthetic Quaternary Ammonium Lipid and Its Precursor Phosphonium Salt. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermolaev, V. V.; Arkhipova, D.M.; Miluykov, V.A.; Lyubina, A.P.; Amerhanova, S.K.; Kulik, N. V.; Voloshina, A.D.; Ananikov, V.P. Sterically Hindered Quaternary Phosphonium Salts (QPSs): Antimicrobial Activity and Hemolytic and Cytotoxic Properties. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 23, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukáč, M.; Pisárčik, M.; Garajová, M.; Mrva, M.; Dušeková, A.; Vrták, A.; Horáková, R.; Horváth, B.; Devínsky, F. Synthesis, Surface Activity, and Biological Activities of Phosphonium and Metronidazole Salts. J Surfactants Deterg 2020, 23, 1025–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasiyatullina, N.R.; Mironov, V.F.; Gumerova, S.K.; Voloshina, A.D.; Sapunova, A.S. Versatile Approach to Naphthoquinone Phosphonium Salts and Evaluation of Their Biological Activity. Mendeleev Communications 2019, 29, 435–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Q.; Lai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, R.; Zhang, W.; Ao, N.; Zhang, H. PEGylated Bis-Quaternary Triphenyl-Phosphonium Tosylate Allows for Balanced Antibacterial Activity and Cytotoxicity. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2020, 3, 6400–6407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Hu, W.; Lv, S.; Huang, J.; Huang, K. Synthesis of Aliphatic Symmetric Diphosphonium Salts and Bactericidal Activity of Selected Products. Chemistry Journal of Moldova 2017, 12, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Yuan, B.; Lv, S.; Liao, Q.; Huang, J. Synthesis, Characterization and Performance of a New Type of Alkylene Triphenyl Double Quaternary Phosphonium Salt. Journal of Materials Science and Chemical Engineering 2013, 01, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, K.L.; Murphy, E.L.; Majofodun, O.; Muñoz, L.D.; Williams, J.C.; Almeida, K.H. Arylphosphonium Salts Interact with DNA to Modulate Cytotoxicity. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis 2009, 673, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millard, M.; Pathania, D.; Shabaik, Y.; Taheri, L.; Deng, J.; Neamati, N. Preclinical Evaluation of Novel Triphenylphosphonium Salts with Broad-Spectrum Activity. PLoS One 2010, 5, e13131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Wu, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Lam, Y.; Ao, N. Antitumor Activity and Antitumor Mechanism of Triphenylphosphonium Chitosan against Liver Carcinoma. J Mater Res 2018, 33, 2586–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafa, K.K.; Hamzawy, M.A.; Mousa, S.A.; El-Sherbiny, I.M. Mitochondria-Targeted Alginate/Triphenylphosphonium-Grafted-Chitosan for Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. RSC Adv 2022, 12, 21690–21703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, G.E.; Alfei, S.; Caviglia, D.; Domenicotti, C.; Marengo, B. Antimicrobial Peptides and Cationic Nanoparticles: A Broad-Spectrum Weapon to Fight Multi-Drug Resistance Not Only in Bacteria. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 6108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenti, G.E.; Roveri, A.; Venerando, R.; Menichini, P.; Monti, P.; Tasso, B.; Traverso, N.; Domenicotti, C.; Marengo, B. PTC596-Induced BMI-1 Inhibition Fights Neuroblastoma Multidrug Resistance by Inducing Ferroptosis. Antioxidants 2023, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colla, R.; Izzotti, A.; De Ciucis, C.; Fenoglio, D.; Ravera, S.; Speciale, A.; Ricciarelli, R.; Furfaro, A.L.; Pulliero, A.; Passalacqua, M.; et al. Glutathione-Mediated Antioxidant Response and Aerobic Metabolism: Two Crucial Factors Involved in Determining the Multi-Drug Resistance of High-Risk Neuroblastoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 70715–70737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfei, S.; Marengo, B.; Domenicotti, C. Polyester-Based Dendrimer Nanoparticles Combined with Etoposide Have an Improved Cytotoxic and Pro-Oxidant Effect on Human Neuroblastoma Cells. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfei, S.; Marengo, B.; Zuccari, G.; Turrini, F.; Domenicotti, C. Dendrimer Nanodevices and Gallic Acid as Novel Strategies to Fight Chemoresistance in Neuroblastoma Cells. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berridge, M. V.; Herst, P.M.; Tan, A.S. Tetrazolium Dyes as Tools in Cell Biology: New Insights into Their Cellular Reduction. In; 2005; pp. 127–152.

- Kumar, P.; Nagarajan, A.; Uchil, P.D. Analysis of Cell Viability by the Lactate Dehydrogenase Assay. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2018, 2018, pdb.prot095497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrasekhar, B.; Gor, R.; Ramalingam, S.; Thiagarajan, A.; Sohn, H.; Madhavan, T. Repurposing FDA-Approved Compounds to Target JAK2 for Colon Cancer Treatment. Discover Oncology 2024, 15, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielonka, J.; Joseph, J.; Sikora, A.; Hardy, M.; Ouari, O.; Vasquez-Vivar, J.; Cheng, G.; Lopez, M.; Kalyanaraman, B. Mitochondria-Targeted Triphenylphosphonium-Based Compounds: Syntheses, Mechanisms of Action, and Therapeutic and Diagnostic Applications. Chem Rev 2017, 117, 10043–10120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanya, D.; Giuseppe, P.; Rita, C.A.; Annaluisa, M.; Stefania, S.M.; Francesca, G.; Vitale, D. V.; Anna, R.; Claudio, A.; Pasquale, L.; et al. Phosphonium Salt Displays Cytotoxic Effects Against Human Cancer Cell Lines. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2018, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfei, S.; Marengo, B.; Valenti, G.; Domenicotti, C. Synthesis of Polystyrene-Based Cationic Nanomaterials with Pro-Oxidant Cytotoxic Activity on Etoposide-Resistant Neuroblastoma Cells. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, G.E.; Marengo, B.; Milanese, M.; Zuccari, G.; Brullo, C.; Domenicotti, C.; Alfei, S. Imidazo-Pyrazole-Loaded Palmitic Acid and Polystyrene-Based Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization and Antiproliferative Activity on Chemo-Resistant Human Neuroblastoma Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 15027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfei, S.; Zuccari, G.; Caviglia, D.; Brullo, C. Synthesis and Characterization of Pyrazole-Enriched Cationic Nanoparticles as New Promising Antibacterial Agent by Mutual Cooperation. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuccari, G.; Zorzoli, A.; Marimpietri, D.; Brullo, C.; Alfei, S. Pyrazole-Enriched Cationic Nanoparticles Induced Early- and Late-Stage Apoptosis in Neuroblastoma Cells at Sub-Micromolar Concentrations. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, B.; Cagide, F.; Fernandes, C.; Borges, A.; Borges, F.; Simões, M. Efficacy of Novel Quaternary Ammonium and Phosphonium Salts Differing in Cation Type and Alkyl Chain Length against Antibiotic-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 25, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Na, T.; Wang, L.; Gao, Q.; Yin, W.; Wang, J.; Yuan, B.-Z. Human Diploid MRC-5 Cells Exhibit Several Critical Properties of Human Umbilical Cord-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Vaccine 2014, 32, 6820–6827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, J.; Chen, S.; Ning, B.; Tolleson, W.H.; Guo, L. Development of HepG2-Derived Cells Expressing Cytochrome P450s for Assessing Metabolism-Associated Drug-Induced Liver Toxicity. Chem Biol Interact 2016, 255, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donato, M.T.; Tolosa, L.; Gómez-Lechón, M.J. Culture and Functional Characterization of Human Hepatoma HepG2 Cells. Methods Mol Biol 2015, 1250, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolosa, L.; Gómez-Lechón, M.J.; López, S.; Guzmán, C.; Castell, J. V; Donato, M.T.; Jover, R. Human Upcyte Hepatocytes: Characterization of the Hepatic Phenotype and Evaluation for Acute and Long-Term Hepatotoxicity Routine Testing. Toxicol Sci 2016, 152, 214–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Sena, T.; Moro, E.; Moreno-Torres, M.; Quintás, G.; Hengstler, J.; Castell, J. V. Metabolomics-Based Strategy to Assess Drug Hepatotoxicity and Uncover the Mechanisms of Hepatotoxicity Involved. Arch Toxicol 2023, 97, 1723–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzumanian, V.A.; Kiseleva, O.I.; Poverennaya, E. V. The Curious Case of the HepG2 Cell Line: 40 Years of Expertise. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 13135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzywik, J.; Mozga, W.; Aminpour, M.; Janczak, J.; Maj, E.; Wietrzyk, J.; Tuszyński, J.A.; Huczyński, A. Synthesis, Antiproliferative Activity and Molecular Docking Studies of Novel Doubly Modified Colchicine Amides and Sulfonamides as Anticancer Agents. Molecules 2020, 25, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, W.; Zhou, B. Hepatocyte Generation in Liver Homeostasis, Repair, and Regeneration. Cell Regeneration 2022, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellerbrand, C. Role of Fibroblast Growth Factors and Their Receptors in Liver Fibrosis and Repair. Curr Pathobiol Rep 2015, 3, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Analysis | BTTB NPs |

| ATR-FTIR [cm−1] |

|

|

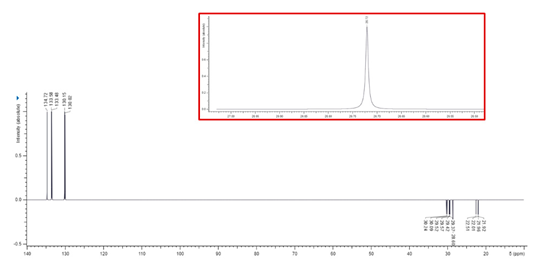

1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) |

|

|

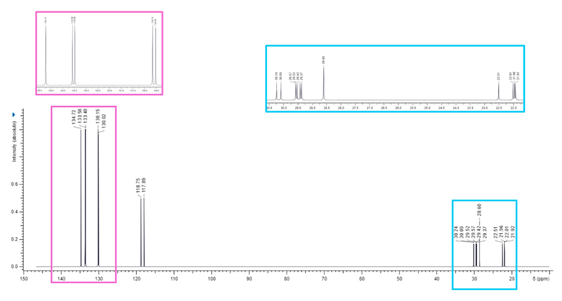

13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) |

|

|

13C NMR DEPT 135 (100 MHz, CDCl3) 31P NMR (red square) (162 MHz, CDCl3) |

|

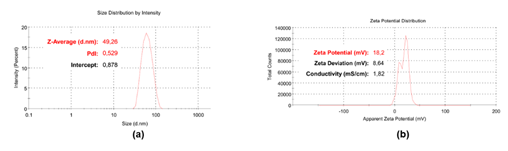

| Z-Ave (nm) and PDI (a) ζ-p (mV) (b) |

|

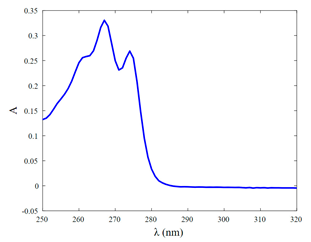

| UV-Vis Spectrum |  |

| IC50 COS-7 cell (µg/mL) * IC50 HepG2 cell (µg/mL) * |

5.76 ± 0.95 11.31 ± 1.54 |

| MICs Gram-positive (µg/mL) MICs Gram-negative (µg/mL) |

0.25-0.50 1.00-32.00 |

| SIs Gram-positive ** SIs Gram-negative ** |

23-46 0.4-11.3 |

| Potentiometric Titration # |  |

| Optical Microscopy Captured with a 40 × objective (a) Captured with a 100 × objective (b) |

|

| Exposure time (hours) | IC50 HTLA-230 (µM) | IC50 HTLA-ER (µM) |

| 24 | 0.7378 ± 0.5459 | 1.8510 ± 0.3920 |

| 48 | 0.5900 ± 0.4453 | 0.7316 ± 0.1586 |

| 72 | 0.2033 ± 0.1781 | 0.8919 ± 0.1666 |

| Exposure time (hours) | IC50 HTLA-230 (µM) | IC50 HTLA-ER (µM) |

| 24 | 0.2375 ± 0.0322 | 1.1120 ± 0.2380 |

| 48 | 0.1962 ± 0.0211 | 0.9298 ± 0.0956 |

| 72 | 0.2281 ± 0.0176 | 0.8334 ± 0.0685 |

| Exposure time (hours) | IC50 MRC-5 (µM) |

| 24 | 2.7740 ± 2.6655 |

| 48 | 0.7395 ± 0.5716 |

| 72 | 0.9277 ± 0.8956 |

| Immortalized Cells | IC50 24 hours (µM) |

| Cos-7 * | 4.9100 ± 0.8100 |

| HepG2 ** | 9.6400 ± 1.3100 |

| Cells | Time of exposure | ||

| 24 hours | 48 hours | 72 hours | |

| MRC-5 * | 11.68 | 3.77 | 4.07 |

| Cos-7 * | 20.72 | N.R. | N.R. |

| HepG2 * | 40.63 | N.R. | N.R. |

| MRC-5 ** | 2.49 | 0.80 | 1.11 |

| Cos-7 ** | 4.42 | N.R. | N.R. |

| HepG2 ** | 8.68 | N.R. | N.R. |

| Cells | IC50 µM | SI |

| RBCs * | 14.92 ± 10.80 | N.A. |

| RBCs ** | ||

| HTLA-230 *** | 0.2375 ± 0.0322 | 74.60 |

| HTLA-ER *** | 1.1120 ± 0.2380 | 13.56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).