Introduction

Currently, breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer fatalities among women, with a mortality rate of 1 in 39 in the US, making up 30% of all female cancer diagnoses [

1]. Breast cancer screening is critical for early detection, significantly improving treatment outcomes. Yet, Afghan refugees encounter unique obstacles in accessing these crucial services. Cultural beliefs around modesty and the requirement for female healthcare providers clash with the invasive nature of screenings like mammography [

2]. These cultural barriers, coupled with linguistic hurdles, create a significant disconnect between healthcare providers and Afghan refugees, making it challenging to convey the critical importance of early detection [

2]. Additionally, navigating the healthcare system in a new country can be daunting for refugees, who often struggle with language barriers, further complicating their access to necessary screening services [

3].

The logistical and economic challenges of accessing healthcare further compound the issue for Afghan refugees. Unfamiliarity with available breast cancer screening programs, combined with financial instability, forces many to prioritize immediate needs over preventive healthcare measures [

4]. Moreover, the fear of jeopardizing their legal status or facing deportation can deter individuals from seeking out healthcare services, including cancer screening. This situation underscores the urgent need for interventions sensitive to the cultural, economic, and systemic barriers this population faces [

4].

To bridge the gap in breast cancer screening rates among Afghan refugees, a comprehensive approach that includes cultural sensitivity and linguistic appropriateness is essential. Implementing policy changes, enhancing the cultural competence of healthcare providers, and introducing community-based educational initiatives can improve access to and the effectiveness of screening programs [

5]. Such measures not only serve the immediate health needs of Afghan women but also contribute to the broader goal of reducing breast cancer mortality through early detection. This approach reflects a commitment to an inclusive healthcare system that respects and responds to the diverse needs of all communities, ensuring that vulnerable groups such as refugees receive the care and support, they need [

5]. The current study aims to enlighten the challenges faced by Afghan refugees and suggest possible solutions to this healthcare challenge.

Materials and Methods

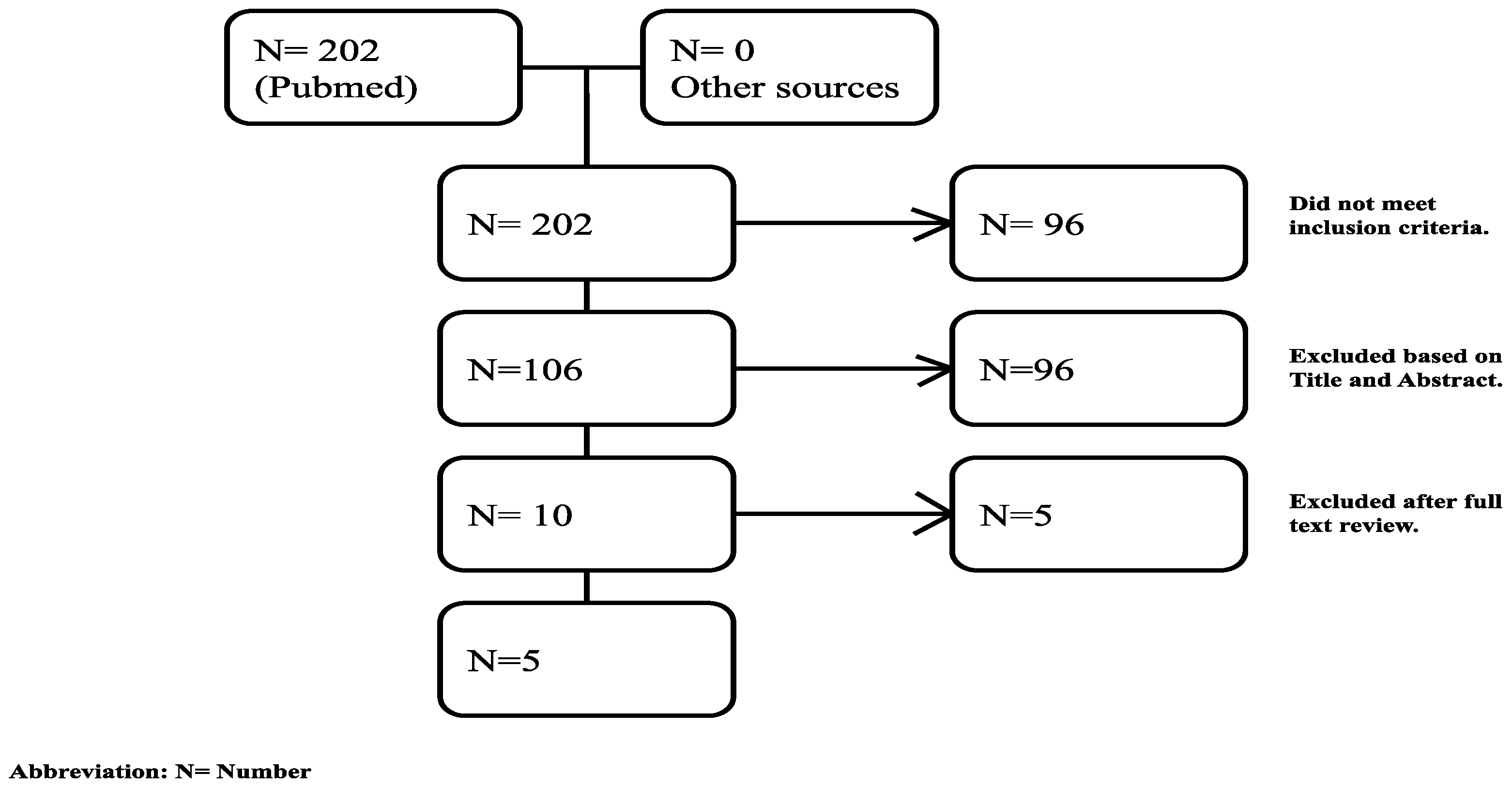

An extensive literature search was conducted using articles exclusively from PubMed dating from 1981 to 2021. Articles published in English were considered for review whereas those written in any other language were excluded. A variation of different keywords such as Afghan female, immigrant, refugee, breast, screening and barriers were used in addition to BOOLEAN operators to narrow search [

Figure 1].

The target population for this research encompasses Afghan female refugees who are at an age deemed appropriate for breast cancer screening according to prevailing medical guidelines. This focus was selected due to the unique challenges and barriers these demographic faces in accessing healthcare services, particularly in the context of preventive health measures like cancer screening.

Inclusion Criteria:

- -

From the review article we selected participants who had to be female refugees of Afghan nationality, reflecting the study’s aim to explore specific cultural, systemic, and access-related barriers within this community.

- -

The age group selected for this study aligns with the recommended age range for breast cancer screening as advised by leading health organizations, ensuring relevance to screening guidelines.

Exclusion Criteria:

- -

Studies or data that did not specifically mention Afghan refugees were excluded from the analysis. This criterion was applied to maintain the focus on the unique context and experiences of Afghan female refugees, distinguishing it from the broader refugee or migrant population experiences.

- -

Research focusing on other forms of cancer or health screenings was also excluded. This decision was made to narrow the study’s scope to breast cancer screening, given its significance as a leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women and the potential for early detection to significantly improve outcomes.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

The demographic analysis of participants from the studies conducted between 2013 and 2022 reveals a diverse range of participant engagement and study designs. The number of female participants varied significantly across the studies, with Kizilkaya

et al. (2022) reporting the highest participation at 430 individuals, followed by Shirazi et al. (2015) with 230 participants in a cluster-randomized design. Other studies, such as Siddiq et al. (2020) and Shirazi et al. (2013, 2015), focused on more qualitative approaches through semi-structured interviews with smaller sample sizes of 19 and 53 participants, respectively [

Table 1].

Identified Barriers to Breast Cancer Screening

Following highlighted several key factors that contribute to the low screening uptake were identified from the literature review.

- -

Breast Cancer Knowledge and Education Level

A fundamental barrier identified across the studies was a lack of breast cancer knowledge [

9,

11,

12,

13], encompassing symptoms, risk factors, and screening procedures. This issue was closely linked to the education level of the community (10-13), where limited educational backgrounds hindered their understanding and awareness of breast cancer [

Table 2]

- -

Cultural, Religious, and Language Barriers

Cultural and religious beliefs (10-12) also emerged as significant barriers, with concerns about modesty and privacy leading to a preference for female physicians. Language barriers (9-13) further complicated access to and understanding of health care services, as many in the Afghan community do not speak English as their primary language [

Table 2].

- -

Socioeconomic Factors and Household Dynamics

Socioeconomic status was a critical barrier (9-13), with many individuals lacking insurance, access to health services, and transportation. Patriarchal household dynamics (9-10, 12-13) also played a role, where men often make healthcare decisions, potentially delaying or preventing women from seeking screening. Social isolation (10, 12, 13) limited women’s engagement with healthcare services, as they rarely leave their homes without accompaniment [

Table 2] .

Psychological factors, including the fear of cancer (9) and fatalistic beliefs (10, 12), were also significant. The fear of a cancer diagnosis, associated with death and societal shame, along with the belief that health outcomes are predetermined by divine will, deterred individuals from participating in screening programs [

Table 2].

Discussion

In recent years, the United States has seen a significant influx of Afghan refugees, with more than 97,000 individuals resettling across the country over the last two decades [

6,

7]. States like California, Texas, and Virginia have become vital destinations, hosting large communities of these new arrivals [

8]. This demographic transition shines a spotlight on the myriad challenges that Afghan refugees, particularly women, encounter when trying to access healthcare services in their new homeland. Among these challenges, breast cancer screening emerges as a critical area of concern, hindered by a complex interplay of cultural, linguistic, and educational barriers [

6,

7,

8].

The cultural norms and expectations within the Afghan community, especially regarding gender roles and modesty, significantly influence women’s health-seeking behaviors. Many Afghan women express discomfort with the idea of breast cancer screening, mainly due to the involvement of male physicians and a deeply ingrained sense of modesty [

9]. This discomfort is not merely a personal or isolated issue; it reflects broader cultural norms that prioritize privacy and modesty, making it difficult for women to seek and receive healthcare. Moreover, the misconception of mammography being a tool solely for diagnosing existing conditions rather than a preventive measure further discourages women from participating in screening programs [

9].

Furthermore, Siddeq

et al. identified a significant obstacle rooted in pre-migration experiences that shaped Afghan refugee women’s views on cancer and its screening processes [

9]. The scarcity of medical facilities in Afghanistan led these women to perceive mammography not as a preventive health measure but rather as a method solely for confirming the presence of cancer [

9]. This perspective is compounded by a lack of breast cancer education, leading to the belief that cancer can only be identified through visible signs and physical symptoms, such as lumps or discomfort. While recognizing symptoms is beneficial, this approach to cancer screening can be detrimental to women’s health, as the most effective screenings occur before symptoms manifest. Viewing mammography through a lens focused on confirmation rather than prevention fosters fear and anxiety among refugee women, deterring them from participating in regular screenings and potentially skipping vital follow-up appointments.

Similarly, like most of the other men’s dominant societies, In Afghan refugee communities, the prevailing norm that men control healthcare decisions significantly limits women’s access to crucial healthcare facilities, such as breast cancer screenings [

10]. This practice is deeply ingrained in both cultural and familial traditions. To effectively address this challenge, interventions need to be culturally considerate, focusing on educating men about the significance of women’s health and involving them in discussions about healthcare. Such strategies modify traditional perceptions and advocate for a more inclusive, collaborative approach to healthcare decisions. Doing so aims to improve healthcare access and outcomes for the entire community, emphasizing the importance of equitable and timely medical care [

10,

11,

12,

13].

The linguistic and educational hurdles faced by Afghan refugee women cannot be overstated. With high rates of illiteracy and limited English proficiency among this population, there needs to be more communication between healthcare providers and refugees [

10]. This gap affects the delivery of healthcare services and the understanding and trust in these services. The lack of education, particularly among women, exacerbates this issue, as it limits their ability to navigate the healthcare system, understand the importance of preventive care, and communicate effectively with healthcare professionals [

10,

11,

12,

13].

Addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted approach beyond traditional healthcare delivery models. Tailored educational programs sensitive to cultural norms and available in native languages can play a crucial role in bridging the communication gap. Such programs should aim to demystify the healthcare process, clarify the purpose and importance of breast cancer screening, and provide information that respects cultural sensitivities. Engaging community leaders and leveraging community networks can also enhance the effectiveness of these educational efforts, creating a more supportive environment for Afghan women to seek care.

Moreover, healthcare providers need to adopt culturally sensitive practices that acknowledge and respect the unique needs and concerns of Afghan refugee women. This includes providing female physicians with women’s health services, offering clear and detailed explanations of medical procedures, and ensuring privacy and respect during medical appointments. Additionally, the healthcare system must strive to reduce barriers to access, such as language obstacles and literacy issues, by offering translation services, visual aids, and other support mechanisms that cater to the needs of non-English speakers and those with limited education.

Conclusion

To effectively mitigate breast cancer risk among Afghan refugee women, addressing the complex barriers to screening access is paramount. Cultural, linguistic, educational, and socioeconomic challenges significantly impede their access to health services. These barriers can be encountered by implementing culturally sensitive healthcare practices, enhancing community engagement, and offering targeted educational programs. This approach improves access to essential screening for Afghan women and empowers them to make informed health decisions. Integrating such strategies into the U.S. healthcare system can significantly enhance responsiveness and inclusivity, improving health outcomes for diverse populations. Ultimately, this approach serves Afghan refugee women and strengthens the healthcare system’s capacity to achieve health equity across all communities.

Limitations

The primary limitation of our study is its exclusive reliance on PubMed for sourcing relevant articles, potentially overlooking pertinent studies available in other databases. Despite refining our search from 202 articles, there remains a risk of missing studies integral to our topic. Additionally, our focus on Afghan immigrant populations in California and Turkey limits the generalizability of our findings to Afghan refugees residing in different locales or to other refugee and immigrant groups.

References

- Ellington TD, Miller JW, Henley SJ, Wilson RJ, Wu M, Richardson LC. Trends in breast cancer incidence, by race, ethnicity, and age among women aged≥ 20 years—United States, 1999–2018. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2022 Jan 1;71(2):43.

- Key Statistics for Breast Cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/about/how-common-is-breast-cancer.html.

- Afghanistan Refugees: Facts & Crisis News. https://www.unrefugees.org/emergencies/afghanistan/.

- What’s the Status of Healthcare for Women in Afghanistan Under the Taliban? https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/healthcare-women-afghanistan-under-taliban/.

- Successfully reaching out to women in Afghanistan about cancer. https://www.uicc.org/news/successfully-reaching-out-women-afghanistan-about-cancer.

- Immigrants from Afghanistan A profile of foreign-born Afghans. https://cis.org/Report/Immigrants-Afghanistan.

- States That Have Welcomed the Most Refugees From Afghanistan. https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/articles/2021-09-14/afghan-refugee-resettlement-by-state.

- Afghan Immigrants in the United States. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/afghan-immigrants-united-states.

- Siddiq H, Pavlish C, Alemi Q, Mentes J, Lee E. Beyond resettlement: sociocultural factors influencing breast and colorectal cancer screening among Afghan refugee women. Journal of Cancer Education. 2020 Jul 7:1-0. [CrossRef]

- Shirazi M, Bloom J, Shirazi A, Popal R. Afghan immigrant women’s knowledge and behaviors around breast cancer screening. Psycho-Oncology. 2013 Aug;22(8):1705-17. [CrossRef]

- Kizilkaya MC, Kilic SS, Bozkurt MA, Sibic O, Ohri N, Faggen M, Warren L, Wong J, Punglia R, Bellon J, Haffty B. Breast cancer awareness among Afghan refugee women in Turkey. EClinicalMedicine. 2022 Jul 1;49:101459. [CrossRef]

- Shirazi M, Shirazi A, Bloom J. Developing a culturally competent faith-based framework to promote breast cancer screening among Afghan immigrant women. Journal of religion and health. 2015 Feb;54:153-9. [CrossRef]

- Shirazi M, Engelman KK, Mbah O, Shirazi A, Robbins I, Bowie J, Popal R, Wahwasuck A, Whalen-White D, Greiner A, Dobs A. Targeting and tailoring health communications in breast screening interventions. Progress in community health partnerships: research, education, and action. 2015;9(2):83-9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).