1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR), the ability of microorganisms to thrive in the face of antimicrobial agents [

1], has grown into a severe global health threat, projections suggesting that by 2050 about 10 million lives might be endangered by AMR [

2]. Agents for which AMR has been reported include practically all conventional antibiotics such as β-lactams [

3], fluoroquinolones [

4], rifamycins [

5], macrolides [

6], etc. Unfortunately, massive persistent misuse of antibiotics in both human and veterinary medicine keeps fueling AMR, a vicious circle that seems hard to interrupt unless innovative anti-infective therapies are soon brought into play.

In such a disquieting context, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) have been heralded as promising candidates due to their efficacy, broad spectrum and, especially, their mechanism of action-related low propensity to eliciting resistance compared to conventional antibiotics [

7]. These favorable outlooks have not yet translated in a plentiful AMP pipeline; to date only seven AMPs have received FDA approval, namely gramicidin D [

8], daptomycin [

9], colistin [

10], vancomycin [

11], oritavancin, dalbavancin, and telavancin [

12], with a few others such as plectasin [

13], Dermegen

® [

14] or MBI-226

® [

15] in various phases of clinical trials.

Part of the difficulties faced by AMPs aiming to reach the drug market have to do with limited stability due to easy degradation by proteases in biological fluids [

16]. This drawback, inherent to AMP composition of L-amino acids, can be at times successfully addressed by incorporating D- instead of protease-sensitive L-residues at selected locations [

17]. In fact, it is well established that enantiomer (all-D) forms of many AMPs are equipotent with the natural ones [

18]. The D-enantiomers are one case of topoisomerism, a term that refers to three-dimensionally distinct versions of a molecule with the same composition. In addition to the enantio (

e) form, the retro (

r, reverse sequence, L-amino acids) and the retroenantio (

re, reverse sequence, D-amino. acids) forms also fit the topoisomer description. Although the structural changes of a given peptide topoisomer are normally bound to translate into different biological effects, in the

re form a certain measure of topological similarity exists with the canonic form [

19,

20]: the side chains in both structures adopt superimposable orientations when the latter is plotted in horizontally flipped fashion (

Figure 1). Based on this spatial mimicry, various research efforts in recent years have sought to develop

re peptides with improved activity [

21].

In this work we focus on crotalicidin (Ctn), a 34-residue AMP from the venom of

Crotalus durissus terrifus, a South American pit viper [

24]. Ctn exhibits potent antimicrobial activity against clinical or laboratory strains, especially gram-negative ones. It is, however, slightly toxic towards eukaryotic cells, including cancer cells, which makes it a good anticancer peptide (ACP) candidate. Virtual Ctn dissection with elastase yields fragments Ctn[1-14] and Ctn[15-34]. While the former (KRFKKFFKKVKKSV) retains the α-helical conformation of Ctn, it loses both the anticancer and antimicrobial properties. In contrast, less structured Ctn[15-34] (KKRLKKIFKKPMVIGVTIPF) remains comparable to Ctn on both antimicrobial and anticancer terms, and exhibits minimal toxicity towards healthy eukaryotic cells. Notably, Ctn[15-34] half-life in human serum is an unusual 770 min, compared with 71 min for full-sequence Ctn [

24,

25,

26]. Mechanistically, both Ctn and its fragment Ctn[15-34] operate through a three-step pattern [

27]: (1) initial peptide recruitment to the bacterial membrane by electrostatic interactions, (2) accumulation on the membrane surface, and (3) membrane disruption and ensuing bacterial cell death.

In the light of these findings, we explored the topoisomer strategy, specifically the

re approach, on both peptides, testing them as AMPs and ACPs with promising outcomes. Additionally, stability studies demonstrated increased half-life time after 24 h for the

re versions [

21]. The next logical step after these encouraging results is that of the current work, where we explore the

in vivo potential of Ctn and Ctn[15-34] and their

re counterparts in a murine infection model with

Acinetobacter baumannii, a pathogen in the ESKAPE group [

28] and a top concern for the World Health Organization (WHO).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mice, Bacterial Strains and Other Material

Balb/c mice (9-12 weeks old, 15-28 g, male and female, were supplied by Charles River Laboratory; the study procedures were approved by the Animal and Human Experimentation Ethics Committee at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB, Barcelona, Spain). The animals were acclimated at least 5 days from arrival until the start of the experiment with a free diet and water provided.

A. baumannii strains (CECT 452, Valencia, Spain, ATCC 15308, Manassas, Va, USA) were from the Colección Española de Cultivos Tipo (CECT, Valencia, Spain). Porcine mucin was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA); Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany); AGAR from BD (Germiston South, South Africa); Lysogeny Broth (LB) from Nzytech (Lisbon, Portugal); and Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBS) from Cytiva (Fålhagen, Sweden).

The ELISA kit for TNF-α in human cells was Human TNF ELISA Kit II from BD Bioscience (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and that for TNF-α in mouse blood was Mouse TNF Alpha ELISA Development Kit (ABTS) from LSBio (Lynnwood, WA, USA). ABTS Liquid substrate solution, BSA, Tween-20 and ELISA plates (439454) were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA); Dulbecco’s PBS [x10] from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA, USA); and E.coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS) O111:B4 (O-LPS) was from Hycult Biotech (Uden, Netherlands).

2.2. Peptides

Ctn, Ctn

re, Ctn[15-34] and Ctn[15-34]

re (sequences shown in

Table 1) were produced by Fmoc solid phase synthesis as previously described [

21]. The purified end products were satisfactorily characterized by HPLC and mass spectrometry.

2.3. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

MIC was determined as described [

17]. Peptide stocks in water were serially diluted from 100 to 0.2 μM and added to polypropylene 96-well plates (Greiner, Frickenhausen, Germany). Fresh bacteria were incubated at 37 °C in MHB up to exponential growth and diluted to a final inoculum of 5 × 10

5 CFU/mL. BSA and acetic acid at 0.04% (w/v) and 0.002% (v/v) final concentration, respectively, were added to avoid peptide self-aggregation. Plates were incubated for 20–22 h at 37 °C. Each peptide was tested in duplicate. MIC values were defined as the lowest peptide concentration where bacterial growth was not detected.

2.4. Tolerance in Mice

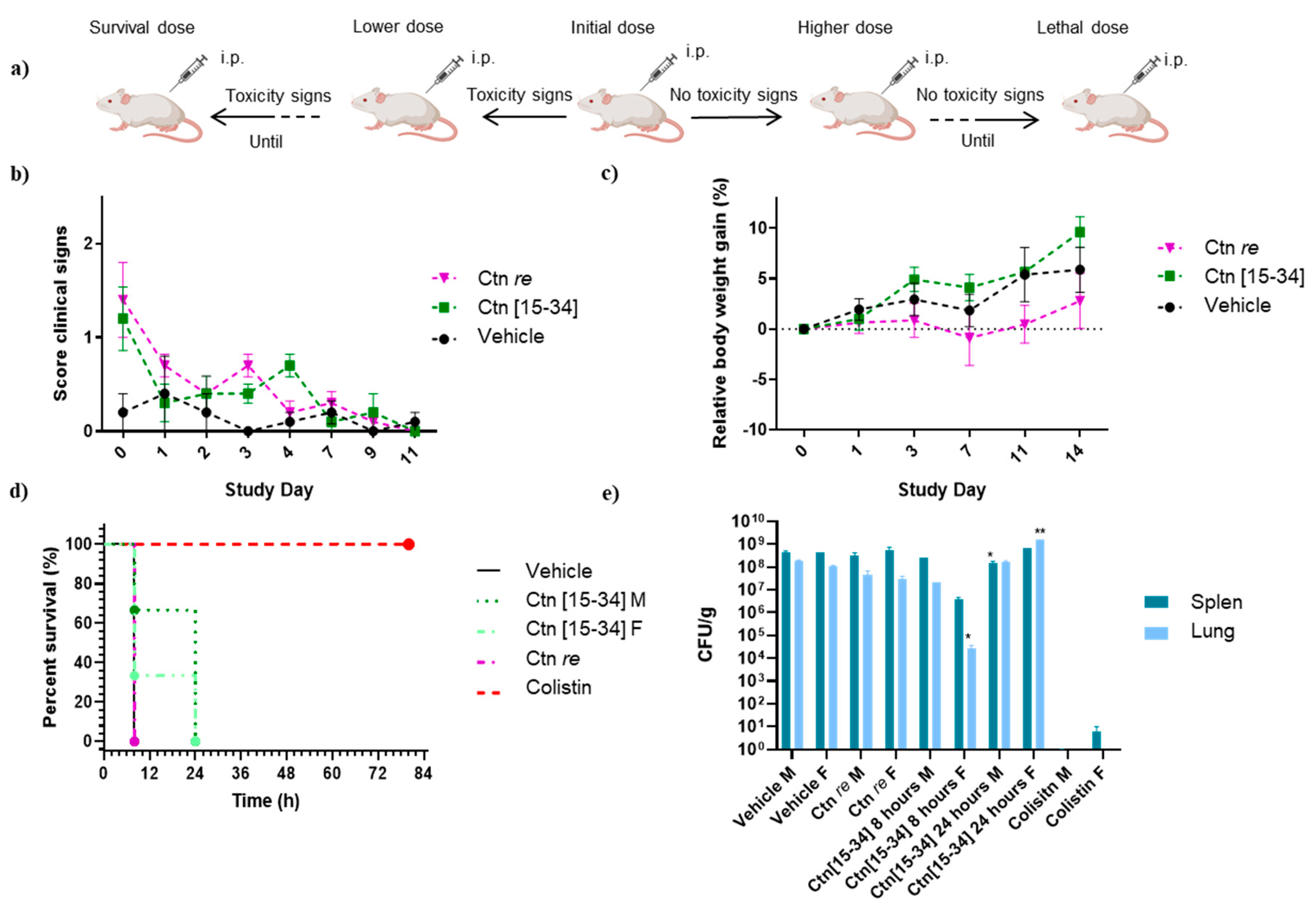

To determine the maximum lethal dose and appropriate doses for the main study, a sighting study (

Figure 2a) was first conducted. Peptides (Ctn[15-34], Ctn[15-34]

re and Ctn

re) were administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) at initial doses of 30 mg/kg for Ctn[15-34] and Ctn[15-34]

re and 3 mg/kg for Ctn

re. If no toxicity signs were observed, the dose was increased. If toxicity signs or death occurred, a lower dose was administered to another animal until an adequate dose was found. After the sighting study was completed, two main studies were performed.

Assay 1: Four randomly distributed groups of five female mice each were used for Ctn[15-34] (30 mg/kg) and Ctn re (3 mg/kg) and negative control (HBS). Ctn[15-34] re was not included due to spontaneous mortality in the sighting study even at low concentrations. The peptide was administered i.p. and mice were monitored twice on day 0, once-a-day until day 4, and then three times a week. The study lasted for 14 days, after which the animals were euthanized and a systematic necropsy was performed.

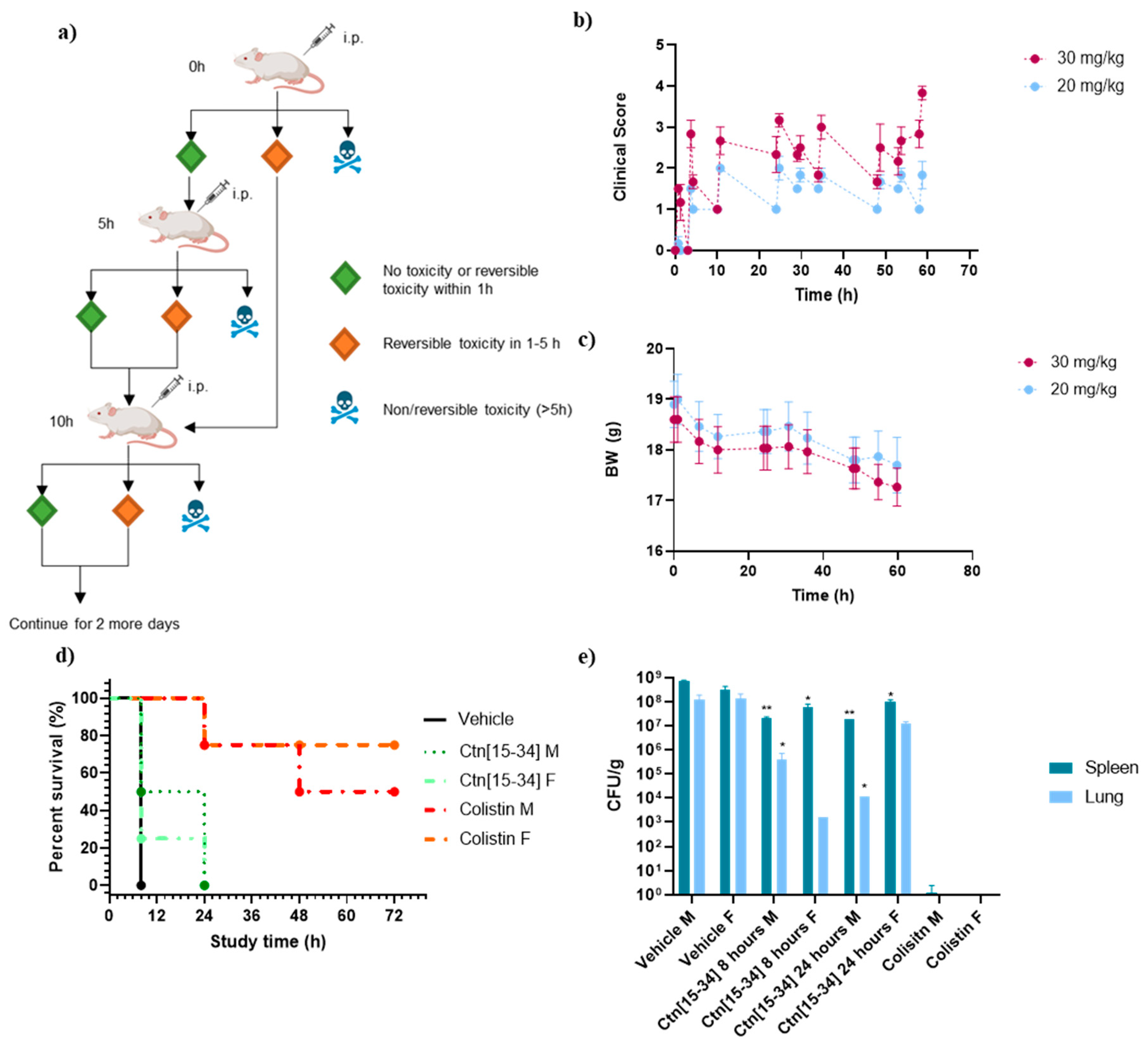

Assay 2: Two randomly distributed groups of six female mice each were given two different concentrations of Ctn[15-34] (30 and 20 mg/kg). The peptide was sequentially administered i.p. as shown in

Figure 3a. Each animal was treated with each dose three times a day for three days. The study was completed when an optimal dose was found that did not induce toxicity or result in very low or reversible toxicity.

2.5. Mouse Systemic Infection

A systemic infection model was established in mice as described before [

29]. Briefly, an aliquot from

A. baumannii stock in 15% glycerol at -80 ºC was taken to culture in 3 mL of LB overnight at 37 ºC and 250 rpm. After an OD600 reading to adjust bacterial concentration, the culture was diluted with an identical volume of 10% porcine mucin (an enhancer of bacterial infectivity [

30]) to a final 1x10

8 CFU/mL concentration. A 10mL/kg inoculation volume was used for each animal

2.6. Efficacy in Mouse Infection Model

Assay 1: 24 mice (12 male, 12 female) randomly distributed into four groups were infected i.p. as described above, then each group was treated with Ctn[15-34] (30 mg/kg), Ctn

re (3 mg/kg), colistin (10 mg/kg, positive control) or vehicle (HBS, negative control). Treatment (performed blindly) was applied 2 h after infection in a single i.p. dose. All animals were checked for clinical signs twice a day for three days as described in

Table S1. On day 2, animals were euthanized with a 200 mg/kg i.p. dose of pentobarbital.

Assay 2: 24 mice (12 male, 12 female) randomly distributed into six groups were infected i.p. as described above, then treated in duplicate groups with Ctn[15-34] (20 mg/kg), colistin (5 mg/kg, positive control) or vehicle (HBS, negative control). Treatment (performed blindly) was applied i.p. 2 h after infection and then every 4 h during day 0, and thrice daily for the next 2 days. All animals were checked for clinical signs twice a day for three days as described in

Table S1. On day 2, animals were euthanized with a 200 mg/kg i.p. dose of pentobarbital.

2.7. Evaluation of Body Weight and Clinical Symptoms

Body weight (BW, g) gain (%) was determined at different stages. In the tolerance assays, BW gain was recorded before inoculation and twice a week for 2 weeks. In the efficacy studies BW gain was likewise measured before inoculation and then twice a day.

Nine clinical parameters were assessed by a scoring system (see

Table S1). For each parameter a score from 0 to 3 in increasing severity was used. In the sighting (tolerance) study, the clinical score was measured at 10 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 7 h, 24 h and 48 h after peptide administration. In assays 1 and 2 of the tolerance study, scoring was done twice a week for 2 weeks. In the efficacy study, the clinical score was recorded every 2-3 h on day 0 and twice a day on days 1 and 2. An animal was euthanized if scoring 3 on any parameter, or if a combined score of 7 or above was reached.

2.8. Evaluation of Colony-Forming Units (CFU) in Mouse Tissues

CFUs in the spleen and lung of animals in the efficacy studies were counted after euthanasia. One lung and half of the spleen were extracted from each animal. Animals found dead overnight were excluded. The organs were weighed and homogenized in 1 mL of HBS. Subsequently, six serial 10-fold dilutions were prepared, each dilution seeded on a Petri dish with LB-agar and colonies counted after 16 h incubation at 37 ºC. Final CFU counts are expressed relative to organ weight (CFU/g).

2.9. Quantification of TNF-α in Mouse Sera by ELISA

In assay 2 of the efficacy study, blood was collected from each animal before euthanasia to assess TNF-α levels. The blood was centrifuged in heparinized tubes at 3200 rpm for 30 min and the supernatant was collected. A mouse TNF-α ELISA kit was used, following manufacturer’s instructions.

2.10. Stimulation of Human Mononuclear Cells (MNC) by LPS

The MNC stimulation assay by LPS R60 HL185 was based on a previous study [

31]. MNC were isolated from heparinized blood samples from healthy donors as described [

32]. The cells were resuspended in 1640 RPMI medium and adjusted to a concentration of 5 x 10

6 cells/mL. 200 μL (1x10

6) of MNC suspension was plated in each of a 96-well plate and then stimulated by incubation with either LPS alone or with a specified peptide/LPS ratio for 4.5 h at 37 ºC with 5% CO

2. Samples were collected and centrifuged and the supernatant was analyzed for human TNF-α using an ELISA kit.

2.11. Histopathology, Tissue Gram Stain and Hematoxylin and Eosin Stain

Following termination of the animals, the following organs were harvested and preserved: right lung, digestive system, pancreas, kidneys, liver, spleen, and brain. These organs were fixed in paraformaldehyde at 4 ºC for 24 h.

The tissue processing proceeded through a stepwise procedure. Firstly, the tissues underwent a rinse with formalin for 1.5 h, followed by cleaning with distilled water for 5 min. Subsequently, they were dehydrated using a series of graded ethanol solutions: 80% ethanol for 1 h, 96% ethanol for two consecutive immersions lasting 1 h each, and finally, 100% ethanol for 2 consecutive immersions of 1 h each and an additional immersion for 1.5 h. Following dehydration, the tissues were submerged in xylene for two immersions, each lasting 1.5 h, before being placed in hot liquid paraffin for two consecutive immersions of 1 h each and an additional immersion of 2 h. The treated specimens were embedded in tissue cassettes using a TissueTek embedding console and allowed to cool until the paraffin solidified [

33,

34].

From each paraffin block, 4 mm sections were cut using a microtome (Leica) and mounted on slides. These slides underwent rehydration through a series of graded alcohols: 100% ethanol for 5 min, 85% ethanol for 5 min, 70% ethanol for 5 min, and distilled water. Following rehydration, a modified Gram stain was performed on the tissue, following the protocol described in [

35] (Basic fuchsin, Thermo Fischer; crystal violet solution, Lugol’s iodine solution, Merck). After drying, the sections were analyzed using a microscope (Leica DMR, Leica Biosystems, IL, United States).

Additionally, the samples were stained with hematoxylin at 10% in absolute ethanol (hematoxylin cryst., Sigma Aldrich) and eosin at 0.5% in distilled water (Eosin Y, Sigma Aldrich). Briefly, the samples were hydrated in H2O for 10 min and then stained for 5 min in hematoxylin. After two washes in H2O, the samples were introduced in 70% ethanol with 1% of hydrochloric acid for 30 s. The samples were washed again and stained with eosin for 5 min. Finally, the samples were dehydrated and mounted on gelatinized glass slides. Samples were visualized using a light microscope (Olympus BX51).

2.12. Statistical Analysis

ANOVA tests were performed for statistical comparison between groups. The ELISA linear curve was fitted by linear regression (

Figures S1 and S2)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Peptides

Given the promising results of the

re approach in previous studies [

36,

37,

38], we decided to perform a murine infection study of Ctn and Ctn[15-34], in both native and

re versions. From eight peptides in a previous study [

21], the last three in

Table 1 were selected for

in vivo experiments, based on MIC, cytotoxicity and protease stability considerations. The original Ctn was not included due to its low stability in human serum.

3.2. Treatment with Ctn[15-34] Reduces Bacterial Levels in Females, whereas Ctn re Does Not Improve the Survival Rate

A preliminary sighting study was conducted using the three peptides to establish an initial estimate of their maximum tolerance doses, based on the

in vitro findings from our previous study [

21]. This assessment involved i.p. injections, with the initial dosages set at 30 mg/kg for Ctn[15-34], and Ctn[15-34]

re, while Ctn

re started at 3 mg/kg. This dosage was determined by the cytotoxicity assays

in vitro (

Table 1); accordingly, for Ctn[15-34] and Ctn[15-34]

re, with the higher IC

50, the initial dose was 30 mg/kg. For Ctn

re, with an IC

50 10× lower than Ctn[15-34]

re, the initial dose was 3 mg/kg.

In the experiment involving Ctn[15-34] re, it became evident that the peptide was toxic: an animal died within 3 min at 30 mg/kg, within 6 min at 15 mg/kg, and after 33 min at 5 mg/kg. Consequently, Ctn[15-34] re was excluded from further in vivo studies while Ctn[15-34] and Ctn re were viable at the predicted dosages.

In the tolerance assay 1, the results from the sighting study were confirmed. Animals received single doses of 30 mg/kg for Ctn[15-34], and 3 mg/kg for Ctn

re. While exhibiting early clinical signs such as reduced motor activity, piloerection, and weight loss (see

Figure 2b), most animals showed improved clinical conditions in the following days, including similar BW evolution for Ctn[15-34] and Ctn

re (

Figure 2c).

The therapeutic effectiveness of Ctn[15-34] and Ctn

re, was evaluated in efficacy assay 1 using

A. baumannii as pathogen, with the 10

8 CFU/kg inoculum determined by Li

et al. [

29], supplemented with 5% porcine mucin to induce immunosuppression, and an i.p. peptide dose of 30 mg/kg for Ctn[15-34] and 3 mg/kg for Ctn

re. In the negative control group treated with HBS (vehicle), all animals exhibited severe clinical symptoms after 8 h while in the positive control group (colistin), a 100% survival rate was observed. Although the colistin-treated animals, a weight loss on the first day with subsequent recovery was found. There was also an initial slight increase in clinical scores, but the animals showed improvement later on.

Animals given Ctn

re behaved similar to the vehicle-treated group, being euthanized after 8 h due to clinical symptoms. In contrast, Ctn[15-34] showed higher survival rate that allowed to extend observation for 24 h (

Figure 2d). As shown in

Figure 2d and 2e, segregating into female (F) and male (M) categories allowed to observe some differences in toxicity and survival outcomes.

After both efficacy studies on

A. baumannii, left lung and spleen specimens were taken to determine infection levels by CFU (colony-forming units) counts. CFU/g values were in the 10

8-10

9 and 10

1-10

2 range, respectively, for the vehicle and the positive control (colistin) groups. Ctn

re scored similar to the vehicle-treated group, and so did Ctn[15-34] on male animals, but female mice showed a reduced bacterial count during an initial 8-h period, followed by a rise at 24 h (

Figure 2e).

3.3. Treatment with Ctn[15-34] Thrice a Day Lowers Bacterial Load But Does Not Improve Survival Rate

A second trial (efficacy study 2) was done after a new toxicological assay for Ctn[15-34] only (tolerance assay 2), where peptide was given thrice daily for 3 consecutive days, at 30 and 20 mg/kg. In both dosage groups, a 6-9% BW loss during the first 24 h (

Figure 3c) was observed, along with some toxicity signs (abdominal distension, resolving rapidly within 30 min; mucous faeces, piloerection, abnormal behaviour and hunched posture). For the second group these clinical signs were reversible and consistently lower than for the 30 mg/kg group (

Figure 3b), hence the lower dosage (20 mg/kg thrice daily for 3 days) was chosen.

In this study, animals given HBS had to be euthanized after 8 h due to the onset of clinical signs. Increased toxicity was also found with the thrice daily dose of colistin compared to the previous study, with severe clinical signs causing the termination of one male and one female animal at 24 h, and only 50% male and 75% female animals surviving at the endpoint (

Figure 3d).

Ctn[15-34], for its part, performed comparably to the previous study, with some difference in survival rates between male (all euthanized after 8 h) and female animals (50 % survival at 8 h, all euthanized by 24 h,

Figure 3d

The CFU/g counts in the lung and the spleen after the endpoint (

Figure 3e) shows a clear distinction between male and female animals treated with Ctn[15-34]. Although both groups had died by 24 h, bacterial counts at 8 h were lower in females than in males. Intriguingly, after 24 h this difference was reversed. Also worth noting was the finding that, in animals not surviving the thrice daily colistin dosage, bacterial presence in spleen or lungs was nearly negligible, suggesting death from causes other than the infection, most likely nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity [

39,

40].

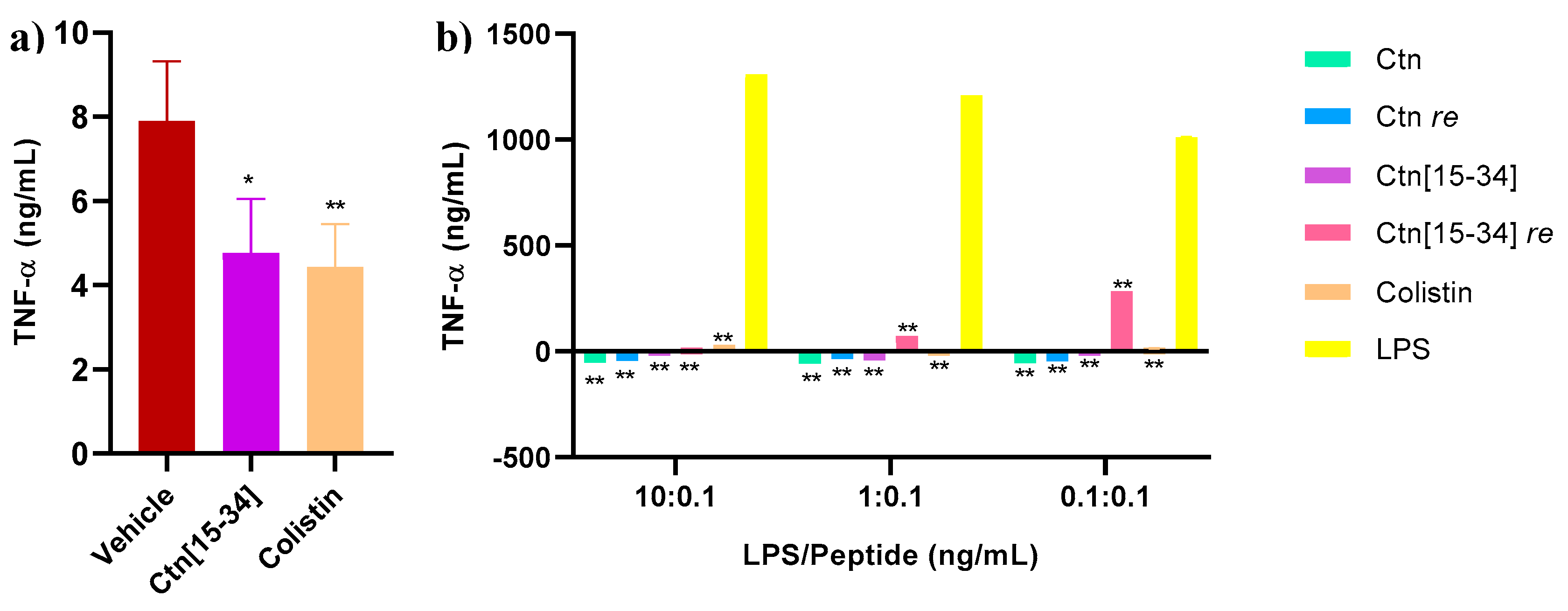

3.4. Ctn[15-34] Reduces Levels of TNF-α in Mice after 8 h and Ctn[15-34] re Increase TNF-α Levels in LPS-Stimulated Human MNC Cells

Blood0020samples were collected from each sacrificed animal in efficacy study 2 to measure TNF-α levels. Excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, is associated with septic shock, a critical factor contributing to mortality in Gram-negative infections [

29]. As depicted in

Figure 4, Ctn[15-34] effectively reduces TNF-α levels in mice to a degree comparable to colistin.

The anti-endotoxin activity of the four peptides (

Table 1), and colistin as positive control, was also assessed by measuring TNF-α levels in human MNC stimulated with different ratios of peptide/LPS. The results showed all peptides effectively reducing TNF-α levels compared to LPS alone. For Ctn[15-34]

re (

Figure 4b), particularly at LPS/peptide ratios of 0.1:0.1, TNF-α levels evidencing high inflammation and eventually a septic shock were found, compatible with the spontaneous deaths observed with this peptide.

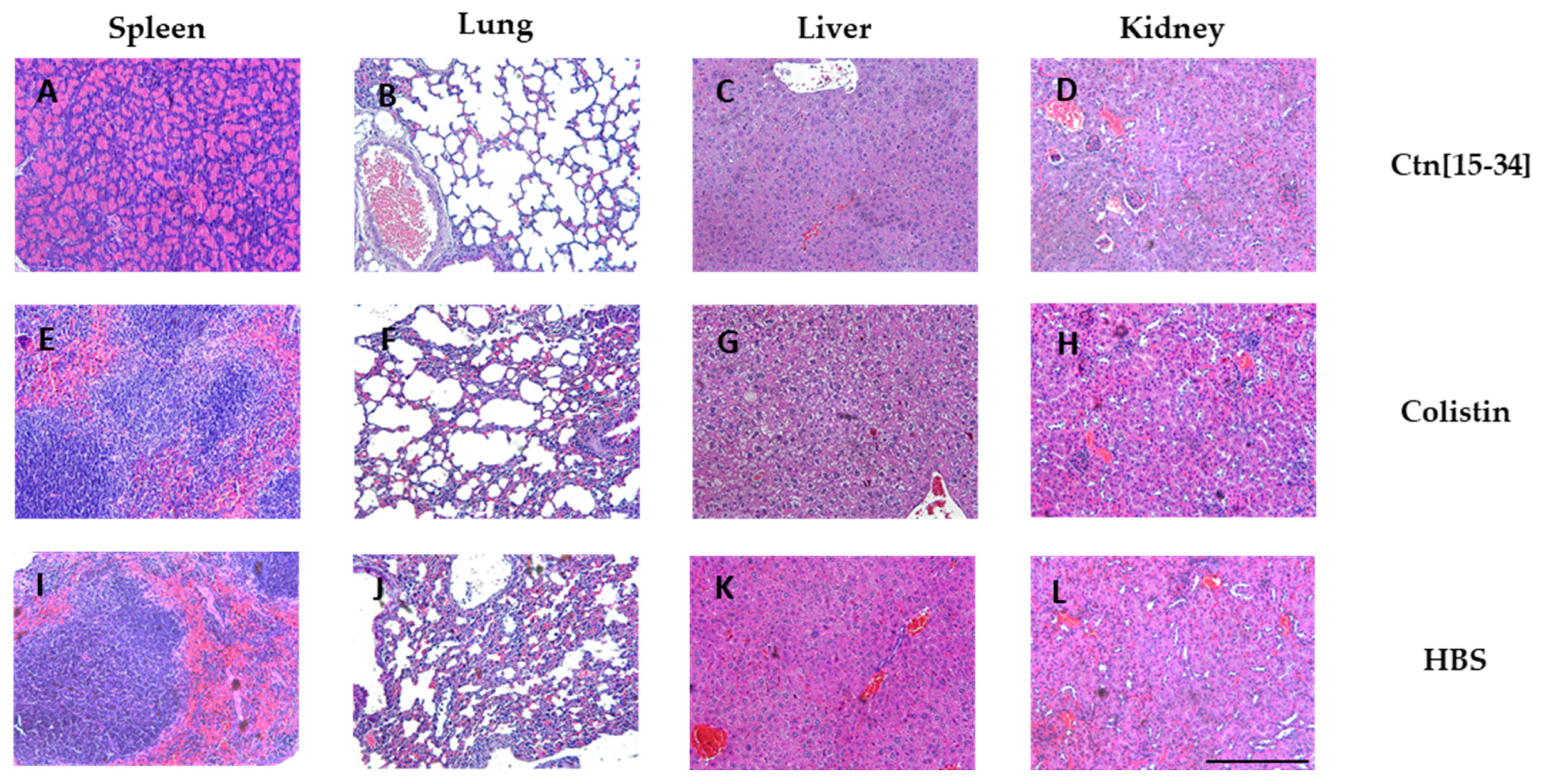

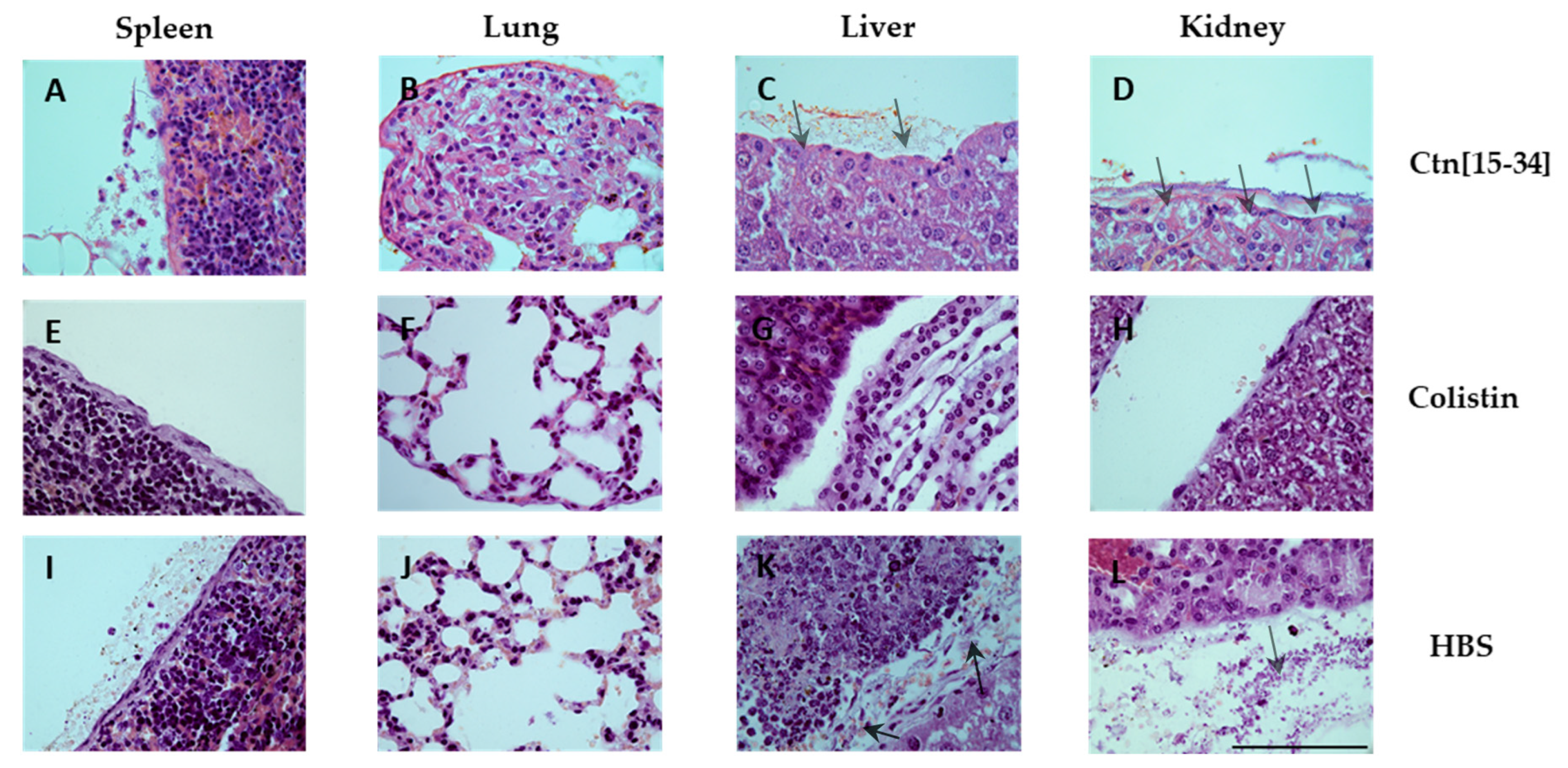

3.5. Organ Staining Consistent with Bacterial Levels at Each Treatment

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of spleen, lung, liver and kidney specimens was performed (

Figure 5). While no lesions compatible with the experimental infection were observed, apoptosis was noted in spleen lymphocytes of one animal each in the HBS (vehicle) and the Ctn[15-34] group.

A Gram stain was also conducted (

Figure 6) to assess bacterial load in each organ. The organs of untreated mice exhibited bacterial accumulation (

Figure 6, I, J, K, and L), indicating spread of infection to other organs. In contrast, organs treated with Ctn[15-34] (

Figure 6, A, B, C, and D) showed reduced bacterial accumulation, primarily in the tissue wall, suggesting partial efficacy though not complete elimination. As expected, organs of colistin-treated mice showed no evidence of bacterial survival (

Figure 6, E, F, G, and H).

3.6. Conclusions

The goal of this study was to assess to what extent the promising

in vitro prospects of peptides Ctn

re, Ctn[15-34] and Ctn[15-34]

re [

21] could be actualized

in vivo as a further step toward therapeutic application. The results obtained in this work are a sobering reminder that the gap between

in vivo and

in vitro studies can be at times frustratingly broad.

We have encountered low efficacy for Ctn re and Ctn[15-34], and an inflammatory response leading to spontaneous death for Ctn[15-34] re. These adverse outcomes, exceeding even low-key expectations from our side, preclude for the moment any further developments on these peptides.

The

in vivo failure of Ctn[15-34] as an AMP might be likely related to interactions with serum proteins such as AFM, ApoL1, ApoM, DBP, and CBG via its C-terminal hydrophobic tail [

26]. While beneficial in shielding the peptide from protease degradation, too extensive binding to serum proteins might limit the amount of peptide available for interaction with bacteria. Exploring the sensitive balance between peptide and serum proteins, and its impact on antibacterial action is a must for future AMP studies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.-A., D.A. and M.T; methodology, A.C.-A., J.L., E.C., R.B.-M.; validation, A.C.-A., D.A. and M.T.; formal analysis, A.C.-A., D.A. and M.T; investigation, A.C.-A., J.L., E.C. and R.B.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.-A., D.A. and M.T; writing—review and editing, A.C.-A., J.L., E.C., R.B.-M., D.A. and M.T.; funding acquisition, D.A. and M.T.; supervision, D.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Grants from MCIN, Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PID2020-113184RB-C22/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 to D.A. and PID2020-114627RB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 to M.T. were funded by MCIN/AEI; PDC2021-121544-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 to M.T. was funded by MCIN/AEI and European Union Next GenerationEU/ PRTR). Work at UPF was also funded by La Caixa Health Foundation (project HR17_00409 to DA) and by the MCIN “María de Maeztu” Program for Units of Excellence in R&D (CEX2018-000792-M) to the UPF Department of Medicine and Life Sciences at (MELIS-UPF).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committees of Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and Generalitat de Catalunya. Study code 10371 and date of approval 16/01/2019.

Acknowledgments

We thank SIAL (Serveis Integrats de l'Animal de Laboratori) from Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona for the organ staining and the in vivo studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Smith, W.P.J.; Wucher, B.R.; Nadell, C.D.; Foster, K.R. Bacterial Defences: Mechanisms, Evolution and Antimicrobial Resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 519–534. [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.J.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; Johnson, S.C.; Browne, A.J.; Chipeta, M.G.; Fell, F.; Hackett, S.; Haines-Woodhouse, G.; Kashef Hamadani, B.H.; Kumaran, E.A.P.; McManigal, B. et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [CrossRef]

- Lima, L.M.; Silva, B.N.M. da; Barbosa, G.; Barreiro, E.J. β-Lactam Antibiotics: An Overview from a Medicinal Chemistry Perspective. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 208, 112829. [CrossRef]

- Zhanel, G.G.; Ennis, K.; Vercaigne, L.; Walkty, A.; Gin, A.S.; Embil, J.; Smith, H.; Hoban, D.J. A Critical Review of the Fluoroquinolones: Focus on Respiratory Tract Infections. Drugs 2002, 62, 13–59.

- Rothstein, D.M. Rifamycins, Alone and in Combination. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a027011.

- Vázquez-Laslop, N.; Mankin, A.S. How Macrolide Antibiotics Work. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2018, 43, 668–684. [CrossRef]

- Lazzaro, B.P.; Zasloff, M.; Rolff, J. Antimicrobial Peptides: Application Informed by Evolution. Science, 2020, 368. [CrossRef]

- Tishler, M.; Stokes, J.L.; Trenner, N.R.; Conn, J.B. Some Properties of Gramicidin. J. Biol. Chem. 1941, 141, 197–206. [CrossRef]

- Heidary, M.; Khosravi, A.D.; Khoshnood, S.; Nasiri, M.J.; Soleimani, S.; Goudarzi, M. Daptomycin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1–11.

- Yahav, D.; Farbman, L.; Leibovici, L.; Paul, M. Colistin: New Lessons on an Old Antibiotic. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 18–29. [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, M.P. Vancomycin. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1991, 66, 1165–1170.

- Zhanel, G.G.; Calic, D.; Schweizer, F.; Zelenitsky, S.; Adam, H.; Lagac-Wiens, P.R.S.; Rubinstein, E.; Gin, A.S.; Hoban, D.J.; Karlowsky, J.A. New Lipoglycopeptides: A Comparative Review of Dalbavancin, Oritavancin and Telavancin. Drugs 2010, 70, 859–886.

- Mygind, P.H.; Fischer, R.L.; Schnorr, K.M.; Hansen, M.T.; Sönksen, C.P.; Ludvigsen, S.; Raventós, D.; Buskov, S.; Christensen, B.; De Maria, L.; Taboureau, O.; Yaver, D.; Elvig-Jørgensen, S.G.; Sørensen, M. V.; Christensen, B.E.; Kjærulff, S.; Frimodt-Moller, N.; Lehrer, R.I.; Zasloff, M. et al. Plectasin Is a Peptide Antibiotic with Therapeutic Potential from a Saprophytic Fungus. Nature 2005, 437, 975–980. [CrossRef]

- Paquette, D.W.; Simpson, D.M.; Friden, P.; Braman, V.; Williams, R.C. Safety and Clinical Effects of Topical Histatin Gels in Humans with Experimental Gingivitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2002, 29, 1051–1058. [CrossRef]

- “Business Review Editor” Micrologix Licenses Anti-Infective to Fujisawa. Pharma Deal. Rev. 2002, 2002.

- Chen, C.H.; Lu, T.K. Development and Challenges of Antimicrobial Peptides for Therapeutic Applications. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 24. [CrossRef]

- Hamamoto, K.; Kida, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shimizu, T.; Kuwano, K. Antimicrobial Activity and Stability to Proteolysis of Small Linear Cationic Peptides with D-Amino Acid Substitutions. Microbiol. Immunol. 2002, 46, 741–749. [CrossRef]

- Wade, D.; Boman, A.; Wåhlint, B.; Drain, C.M.; Andreu, D.; Boman, H.G.; Merrifield, R.B. All-D Amino Acid-Containing Channel-Forming Antibiotic Peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 4761–4765. [CrossRef]

- Merrifield, R.B.; Juvvadi, P.; Andreu, D.; Ubach, J.; Boman, A.; Boman, H.G. Retro and Retroenantio Analogs of Cecropin-Melittin Hybrids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1995, 92, 3449–3453. [CrossRef]

- Carrera-Aubesart, A.; Gallo, M.; Defaus, S.; Todorovski, T.; Andreu, D. Topoisomeric Membrane-Active Peptides: A Review of the Last Two Decades. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2451. [CrossRef]

- Carrera-Aubesart, A.; Defaus, S.; Pérez-Peinado, C.; Sandín, D.; Torrent, M.; Jiménez, M.Á.; Andreu, D. Examining Topoisomers of a Snake-Venom-Derived Peptide for Improved Antimicrobial and Antitumoral Properties. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2110. [CrossRef]

- Vunnam, S.; Juvvadi, P.; Rotondi, K.S.; Merrifield, R.B. Synthesis and Study of Normal, Enantio, Retro, and Retroenantio Isomers of Cecropin A-Melittin Hybrids, Their End Group Effects and Selective Enzyme Inactivation. J. Pept. Res. 1998, 51, 38–44. [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.2r3pre.

- Falcao, C.B.; Pérez-Peinado, C.; De La Torre, B.G.; Mayol, X.; Zamora-Carreras, H.; Jiménez, M.Á.; Rádis-Baptista, G.; Andreu, D. Structural Dissection of Crotalicidin, a Rattlesnake Venom Cathelicidin, Retrieves a Fragment with Antimicrobial and Antitumor Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 8553–8563. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Peinado, C.; Dias, S.A.; Mendonça, D.A.; Castanho, M.A.R.B.; Veiga, A.S.; Andreu, D. Structural Determinants Conferring Unusual Long Life in Human Serum to Rattlesnake-derived Antimicrobial Peptide Ctn[15-34]. J. Pept. Sci. 2019, 25, e3195. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Peinado, C.; Defaus, S.; Sans-Comerma, L.; Valle, J.; Andreu, D. Decoding the Human Serum Interactome of Snake-Derived Antimicrobial Peptide Ctn[15-34]: Toward an Explanation for Unusually Long Half-Life. J. Proteomics 2019, 204. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Peinado, C.; Dias, S.A.; Domingues, M.M.; Benfield, A.H.; Freire, J.M.; Rádis-Baptista, G.; Gaspar, D.; Castanho, M.A.R.B.; Craik, D.J.; Henriques, S.T.; Veiga, A.S.; Andreu, D. Mechanisms of Bacterial Membrane Permeabilization by Crotalicidin (Ctn) and Its Fragment Ctn(15–34), Antimicrobial Peptides from Rattlesnake Venom. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 1536–1549.

- De Oliveira, D.M.P.; Forde, B.M.; Kidd, T.J.; Harris, P.N.A.; Schembri, M.A.; Beatson, S.A.; Paterson, D.L.; Walker, M.J. Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 33, e00181-19. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Prats-Ejarque, G.; Torrent, M.; Andreu, D.; Brandenburg, K.; Fernández-Millán, P.; Boix, E. In Vivo Evaluation of ECP Peptide Analogues for the Treatment of Acinetobacter Baumannii Infection. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 386. [CrossRef]

- McConnell, M.J.; Actis, L.; Pachón, J. Acinetobacter Baumannii: Human Infections, Factors Contributing to Pathogenesis and Animal Models. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 130–155. [CrossRef]

- Gutsmann, T.; Razquin-Olazarán, I.; Kowalski, I.; Kaconis, Y.; Howe, J.; Bartels, R.; Hornef, M.; Schürholz, T.; Rössle, M.; Sanchez-Gómez, S.; Moriyon, I.; De Tejada, G.M.; Brandenburg, K. New Antiseptic Peptides to Protect against Endotoxin-Mediated Shock. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 3817–3824. [CrossRef]

- Jürgens, G.; Müller, M.; Koch, M.H.J.; Brandenburg, K. Interaction of Hemoglobin with Enterobacterial Lipopolysaccharide and Lipid A. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001, 268, 4233–4242. [CrossRef]

- Bratthauer, G.L. Processing of Tissue Specimens. In Immunocytochemical Methods and Protocols. Methods in Molecular BiologyTM; Javois, L.C., Ed.; Humana Press, 1999; Vol. 115, pp. 77–84.

- Fowler, C.B.; Cunningham, R.E.; O’Leary, T.J.; Mason, J.T. ‘Tissue Surrogates’’ as a Model for Archival Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Tissues.’ Lab. Investig. 2007, 87, 836–846. [CrossRef]

- Young, D.G. The Gram Stain in Tissue: Increasing the Clarity and Contrast Between Gram-Negative Bacteria and Other Cell Components. J. Histotechnol. 2013, 26, 37–39. [CrossRef]

- Gallo, M.; Moreno, E.; Defaus, S.; Ortega-Alvaro, A.; Gonzalez, A.; Robledo, P.; Cavaco, M.; Neves, V.; Castanho, M.A.R.B.; Casadó, V.; Pardo, L.; Maldonado, R.; Andreu, D. Orally Active Peptide Vector Allows Using Cannabis to Fight Pain While Avoiding Side Effects. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 6937–6948. [CrossRef]

- Prades, R.; Oller-Salvia, B.; Schwarzmaier, S.M.; Selva, J.; Moros, M.; Balbi, M.; Grazú, V.; De La Fuente, J.M.; Egea, G.; Plesnila, N.; Teixidó, M.; Giralt, E. Applying the Retro-Enantio Approach To Obtain a Peptide Capable of Overcoming the Blood–Brain Barrier. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 3967–3972. [CrossRef]

- Bukchin, A.; Sanchez-Navarro, M.; Carrera, A.; Teixidó, M.; Carcaboso, A.M.; Giralt, E.; Sosnik, A. Amphiphilic Polymeric Nanoparticles Modified with a Retro-Enantio Peptide Shuttle Target the Brain of Mice. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 7679–7693. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Brunel, J.M.; Dubus, J.C.; Reynaud-Gaubert, M.; Rolain, J.M. Colistin: An Update on the Antibiotic of the 21st Century. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2012, 10, 917–934. [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Kasiakou, S.K. Toxicity of Polymyxins: A Systematic Review of the Evidence from Old and Recent Studies. Crit. Care 2006, 10, 1–13. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).