Submitted:

04 August 2024

Posted:

06 August 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Systems Equilibration.

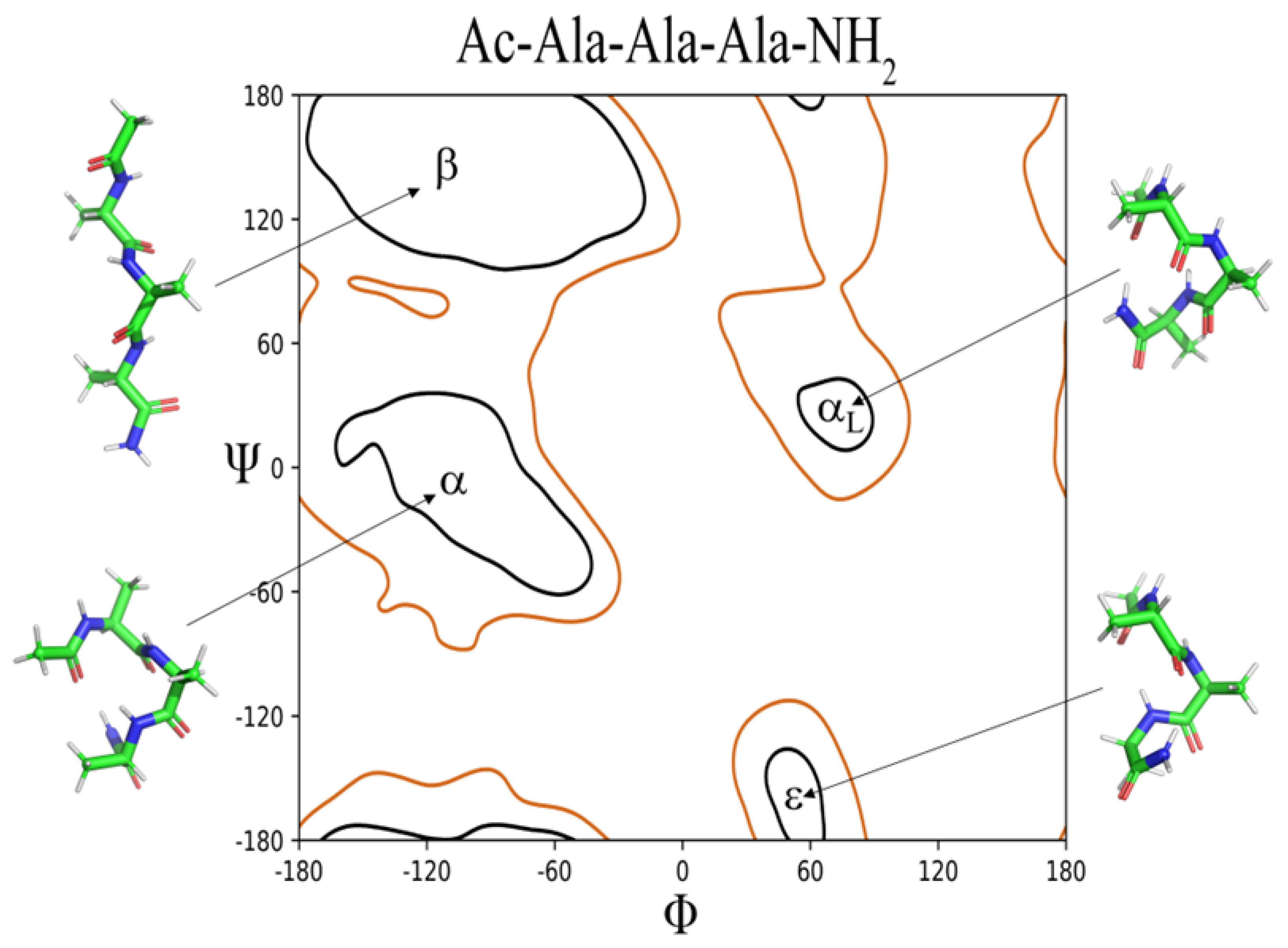

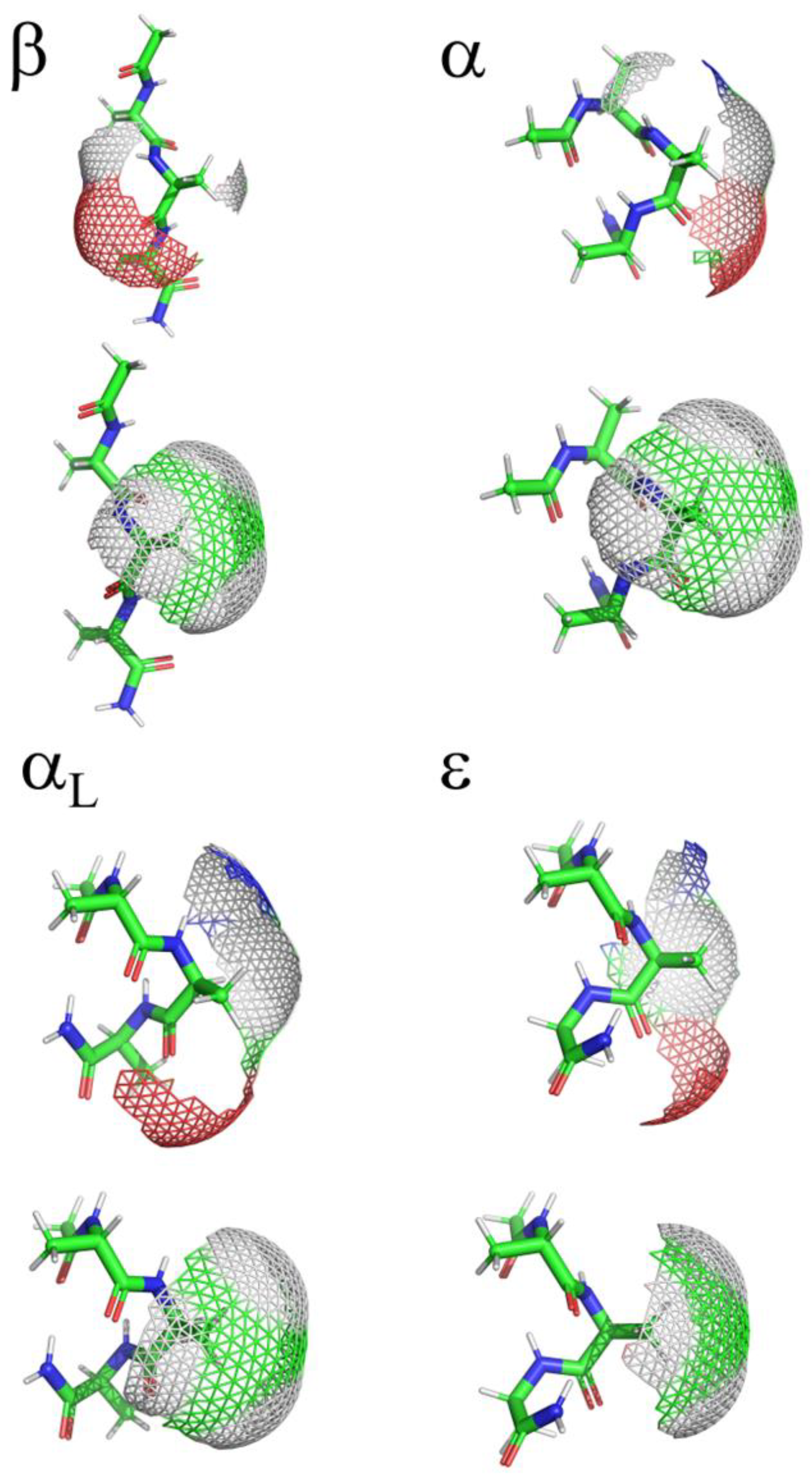

2.2. ϕ, ψ Space Analysis (β, α, αL, ε, and Contiguous Regions).

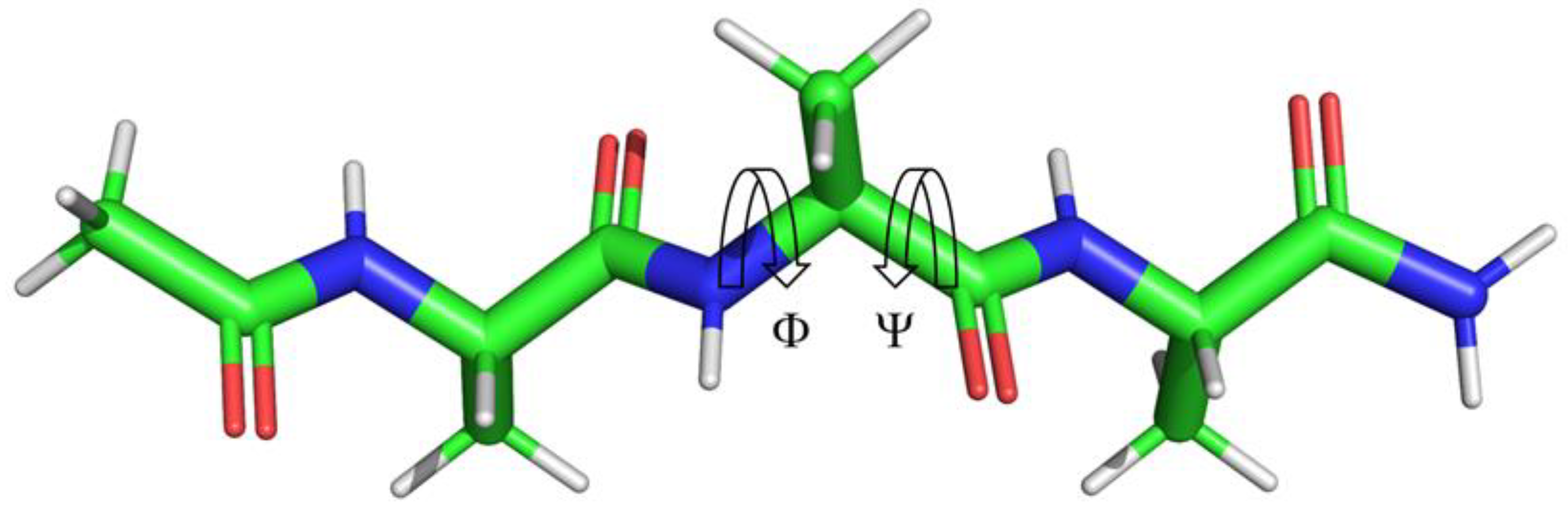

2.3. ϕ, ψ Dihedral Angle Analysis.

2.4. Hydrogen Bond Analysis.

2.5. Solvent Accessible Surface Area Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Materials and Methods

- Energy-minimized with 5000 steps of steepest descent with strong positional restraints to the heavy atoms of the peptide, 209.29 kJ/mol/nm with the initial coordinates as a reference.

- 1000 ps of constant volume and temperature (NVT) MD with a weakly coupled Berendsen thermostat with τ=0.5 ps, a 1 fs time-step and strong positional restraints to the heavy atoms of the peptide, 209.29 kJ/mol/nm with initial coordinates as a reference.[57]

- Energy-minimized with 5000 steps of steepest descent with medium positional restraints to the heavy atoms of the peptide, 83.72 kJ/mol/nm with the initial coordinates as a reference.

- Energy-minimized with 5000 steps of steepest descent with weak positional restraints to the heavy atoms of the peptide, 4.19 kJ/mol/nm with the initial coordinates as a reference.

- Energy-minimized with 5000 steps of steepest descent without any positional restraints to the peptide.

- 100 ps of constant pressure and temperature (NPT) MD with a weakly coupled Berendsen thermostat and barostat with τ=1.0 ps, 1 fs time-step and medium positional restraints to the heavy atoms of the peptide, 83.72 kJ/mol/nm with the final energy minimized conformation as a reference. Initial velocities will be assigned using a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. The hydrogen atoms are restrained by the SHAKE algorithm.[58]

- 100 ps of constant pressure and temperature (NPT) MD with a weakly coupled Berendsen thermostat and barostat with τ=1.0 ps, 1 fs time-step and medium positional restraints to the heavy atoms of the peptide, 20.93 kJ/mol/nm with the final energy minimized conformation as a reference. Initial velocities should be the final velocities from step 6. The hydrogen atoms are restrained by the SHAKE algorithm.

- 100 ps of constant pressure and temperature (NPT) MD with a weakly coupled Berendsen thermostat and barostat with τ=1.0 ps, 1 fs time-step and medium positional restraints to the heavy atoms of the peptide, 4.19 kJ/mol/nm with the final energy minimized conformation as a reference. Initial velocities should be the final velocities from step 7. The hydrogen atoms are restrained by the SHAKE algorithm.

- 100 ps of constant pressure and temperature (NPT) MD with a weakly coupled Berendsen thermostat and barostat with τ=1.0 ps, 2 fs time-step and without restraints to the heavy atoms of the peptide. Initial velocities should be the final velocities from step 8. The hydrogen atoms are restrained by the SHAKE algorithm.

| Category | Xaa | Xaai+1 | … | Xaak | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β, α, αL, or contig. | Oi | Oi+1 | … | Oi=k | Oi,Total |

| Other | Oj | Oj+1 | … | Oj=k | Oj,Total |

| Oi,j,Total |

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- wwPDB Consortium. Protein Data Bank: the single global archive for 3D macromolecular structure data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47 (D1), D520-D528.

- Klebl, D.P.; Aspinall, L.; Muench, S.P. Time resolved applications for Cryo-EM; approaches, challenges and future directions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2023, 83, 102696. [Google Scholar]

- Raviv, U.; Asor, R.; Shemesh, A.; Ginsburg, A.; Ben-Nun, T.; Schilt, Y.; Levartovsky, Y.; Ringel, I. Insight into structural biophysics from solution X-ray scattering. J Struct Biol. 2023, 215(4), 108029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hekstra, D.R. Emerging Time-Resolved X-Ray Diffraction Approaches for Protein Dynamics. Annu Rev Biophys. 2023, 9, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zadorozhnyi, R.; Gronenborn, A.M.; Polenova, T. Integrative approaches for characterizing protein dynamics: NMR, CryoEM, and computer simulations. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2023, 84, 102736. [Google Scholar]

- Arthanari, H.; Takeuchi, K.; Dubey, A.; Wagner, G. Emerging solution NMR methods to illuminate the structural and dynamic properties of proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2019, 58, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceruso, M.A.; Amadei, A.; Di Nola, A. Mechanics and dynamics of B1 domain of protein G: role of packing and surfacce hydrophobic residues. Protein Sci. 1999, 8(1), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kmiecik, S.; Kolinski, A. Folding pathway of the B1 domain of Protein G explored by mulitiscale modeling. Biophys J. 2008, 94(3), 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moult, J.; Pedersen, J.T.; Judson, R.; Fidelis, K. A large-scale experiment to assess protein structure prediction methods. Proteins 1995, 23(3), ii–iV. [Google Scholar]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; Bridgland, A.; Meyer, C.; Kohl, S.A.A.; Ballard, A.J.; Cowie, A.; Romera-Paredes, B.; Nikolov, S.; Jain, R.; Adler, J.; Back, T.; Petersen, S.; Reiman, D.; Clancy, E.; Zielinski, M.; Steinegger, M.; Pacholska, M.; Berghammer, T.; Bodenstein, S.; Silver, D.; Vinyals, O.; Senior, A.W.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Kohli, P.; Hassabis, D. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596(7873), 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; Bodenstein, S.W.; Evans, D.A.; Hung, C.-C.; O’Neill, M.; Reiman, D.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Wu, Z.; Žemgulytė, A.; Arvaniti, E.; Beattie, C.; Bertolli, O.; Bridgland, A.; Cherepanov, A.; Congreve, M.; Cowen-Rivers, A.I.; Cowie, A.; Figurnov, M.; Fuchs, B.; Gladman, H.; Jain, R.; Khan, Y.A.; Low, C.M.R.; Perlin, K.; Potapenko, A.; Savy, P.; Singh, S.; Stecula, A.; Thillaisundaram, A.; Tong, C.; Yakneen, S.; Zhong, E.D.; Zielinski, M.; Žídek, A.; Bapst, V.; Kohli, P.; Jaderberg, M.; Hassabis, D.; Jumper, J.M. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630(8016), 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaytan, A.K.; Shaitan, K.V.; Khokhlov, A.R. Solvent accessible surface area of amino acid residues in globular proteins: correlation of apparent transfer free energies with experimental hydrophobicity scales. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10(5), 1224–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Richards, F.M. The interpretation of protein structures: estimation of static accessibility. J Mol Biol. 1971, 55, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, S.; Janin, J.; Lesk, A.M.; Chothia, C. Interior and surface of monomeric proteins. J Mol Biol. 1987, 196, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harpaz, Y.; Gerstein, M.; Chothia, C. Volume changes on protein folding. Structure 1994, 2(7), 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carugo, O. Amino acid composition and protein dimension. Protein Sci. 2008, 17(12), 2187–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielenkiewicz, P.; Saenger, W. Residue solvent accessibilities in the unfolded polypeptide chain. Biophys J. 1992, ‘63 (6), 1483-1486.

- Maple, J.R.; Dinur, U.; Hagler, A.T. Derivation of force fields for molecular mechanics and dynamics from ab initio energy surfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1988, 85(15), 5350–5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibragimova, G.T.; Wade, R.C. Importance of explicit salt ions for protein stability in molecular dynamics simulation. Biophys J. 1998, 74(11), 2906–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, M.Z.; Meyer, A.G.; Sydykova, D.K.; Spielman, S.J.; Wilke, C.O. Maximum Allowed Solvent Accessibilities of Residues in Proteins. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e80635. [Google Scholar]

- Topham, C.M.; Smith, J.C. Tri-peptide reference structures for the calculation of relative solvent accessible surface area in protein amino acid residues. CComput Biol Chem. 2015, 54, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Rauscher, S.; Nawrocki, G.; Ran, T.; Feig, M.; de Groot, B.L.; Grubmüller, H.; MacKerell, A.D.J. CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nature Methods 2017, 14(1), 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; van der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E.; Hess, B. http://www.gromacs.org, 2022. Gromacs. http://www.gromacs.org (accessed June 1, 2022).

- Essmann, U.; Perera, L.; Berkowitz, M.L.; Darden, T.; Lee, H.; Pedersen, L.G. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. Journal Chem Phys. 1995, 103(19), 8577–8593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennberg, C.L.; Murtola, T.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. Lennard-Jones Lattice Summation in Bilayer Simulations Has Critical Effects on Surface Tension and Lipid Properties. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 2013, 9(8), 3527–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovell, S.C.; Davis, I.W.; Arendall III, W.B.; de Bakker, P.I.W.; Word, J.M.; Prisant, M.G.; Richardson, J.S.; Richardson, D.C. Structure validation by Cα geometry: ϕ,ψ and Cβ deviation. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 2003, 50 (3), 437-450.

- Ho, B.K.; Brasseur, R. The Ramachandran plots of glycine and pre-proline. BMC Struct Biol. 2005, 5, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Elstner, M.; Hermans, J. Comparison of a QM/MM force field and molecular mechanics force fields in simulations of alanine and glycine “dipeptides” (Ace-Ala-Nme and Ace-Gly-Nme) in water in relation to the problem of modeling the unfolded peptide backbone in solution. Proteins. 2003, 50(3), 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craveur, P.; Joseph, A.P.; Poulain, P.; de Brevern, A.G.; Rebehmed, J. Cis-trans isomerization of omega dihedrals in proteins. Amino Acids 2013, 45(2), 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonezawa, Y.; Nakata, K.; Sakakura, K.; Takada, T.; Nakamura, H. Intra- and intermolecular interaction inducing pyramidalization on both sides of a proline dipeptide during isomerization: an ab initio QM/MM molecular dynamics simulation study in explicit water. J Am Chem Soc. 2009, 131(12), 4535–4540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, B.L. The Generalization of ‘Student’s’ Problem when Several Different Population Variances are Involved. Biometrika 1947, 34 (1/2), 28-35.

- Jeffrey, G.A. An introduction to hydrogen bonding; Oxford University Press: New York, 1997; p. 191,200. [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch, W.; Sander, C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 1983, 22(12), 2577–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bystrov, V.F.; Portnova, S.L.; Tsetlin, V.I.; Ivanov, V.T.; Ovchinnikov, Y.A. Conformational studies of peptide systems. The rotational states of the NH--CH fragment of alanine dipeptides by nuclear magnetic resonance. Tetrahedron 1969, 25 (3), 493-515.

- Milner-White, E.J. Situations of gamma-turns in proteins. Their relation to alpha-helices, beta-sheets and ligand binding sites. J Mol Biol 1990, 216 (2), 386-397.

- Shrake, A.; Rupley, J.A. Environment and exposure to solvent of protein atoms. Lysozyme and insulin. J Mol Biol. 1973, 79, 351–372. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, G.D.; Geselowitz, A.R.; Lesser, G.J.; Lee, R.M.; Zehfus, M.M. Hydrophobicity of amino acid residues in globular proteins. Science 1985, 229, 834–838. [Google Scholar]

- Chothia, C. The nature of the accessible and buried surfaces in proteins. J Mol Biol. 1976, 105, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, B.L. On the comparison of several mean values: an alternative approach. Biometrika. 1951, 38 (3-4), 330-336.

- Student. The Probable Error of a Mean. Biometrika 1908, 6(1), 1–25.

- Tsai, J.; Taylor, R.; Chothia, C.; Gerstein, M. The Packing Density in Proteins: Standard Radii and Volumes. J Mol Biol. 1999, 290, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLano, W. Schrödinger LLC. https://www.pymol.com/pymol.

- Best, R.B.; Zhu, X.; Shim, J.; Lopes, P.E.M.; Mittal, J.; Feig, M.; MacKerell, A.D.J. Optimization of the Additive CHARMM All-Atom Protein Force Field Targeting Improved Sampling of the Backbone ϕ, ψ and Side-Chain χ1 and χ2 Dihedral Angles. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012, 8(9), 3257–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackerell, A.D.J.; Feig, M.; Brooks, C.L.I. Extending the treatment of backbone energetics in protein force fields: Limitations of gas-phase quantum mechanics in reproducing protein conformational distributions in molecular dynamics simulations. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2004, 25(11), 0192–8651. [Google Scholar]

- MacKerell Jr., A. D.; Bashford, D.; Bellott, M.; Dunbrack Jr., R.L.; Evanseck, J.D.; Field, M.J.; Fischer, S.; Gao, J.; Guo, H.; Ha, S.; Joseph-McCarthy, D.; Kuchnir, L.; Kuczera, K.; Lau, F.T.K.; Mattos, C.; Michnick, S.; Ngo, T.; Nguyen, D.T.; Prodhom, B.; Reiher, W.E.; Roux, B.; Schlenkrich, M.; Smith, J.C.; Stote, R.; Straub, J.; Watanabe, M.; Wiórkiewicz-Kuczera, J.; Yin, D.; Karplus, M. All-Atom Empirical Potential for Molecular Modeling and Dynamics Studies of Proteins. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 1998, 102 (18), 3586-3616.

- Vanommeslaeghe, K.; Hatcher, E.; Acharya, C.; Kundu, S.; Zhong, S.; Shim, J.; Darian, E.; Guvench, O.; Lopes, P.; Vorobyov, I.; Mackerell, A.D.J. CHARMM general force field: A force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. J Comp Chem. 2010, 31(4), 671–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1-2, 19-25.

- Páll, S.; Abraham, M.J.; Kutzner, C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E.; Markidis, S.; Laure, E. Tackling Exascale Software Challenges in Molecular Dynamics Simulations with GROMACS. Solving Software Challenges for Exascale, Stockholm, 2015; pp 3-27.

- Hess, B.; Kutzner, C.; van der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS 4: Algorithms for Highly Efficient, Load-Balanced, and Scalable Molecular Simulation. J Chem Theory Comput. 2008, 4(3), 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E.; Hess, B.; Groenhof, G.; Mark, A.E.; Berendsen, H.J.C. GROMACS: Fast, flexible, and free. J Comp Chem. 2005, 26(16), 1701–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindahl, E.; Hess, B.; van der Spoel, D. GROMACS 3.0: a package for molecular simulation and trajectory analysis. Molecular modeling annual 2001, 7(8), 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, H.J.C.; van der Spoel, D.; van Drunen, R. GROMACS: A message-passing parallel molecular dynamics implementation. Comput Phys Commun. 1995, 91(1), 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelkmar, P.; Larsson, P.; Cuendet, M.A.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. Implementation of the CHARMM Force Field in GROMACS: Analysis of Protein Stability Effects from Correction Maps, Virtual Interaction Sites, and Water Models; J Chem Theory Comput. 2010, 6(2), 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, D.R.; Brooks, B.R. A protocol for preparing explicitly solvated systems for stable molecular dynamics simulations. J Chem. Phys. 2020, 153(5), 054123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, W.G. Canonical dynamics: Equilibrium phase-space distributions. Physical Review A 1985, 31(3), 1695–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, W.G. Constant-pressure equations of motion. Physical Review A 1986, 34(3), 2499–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berendsen, H.J.C.; Postma, J.P.M.; van Gunsteren, W.F.; DiNola, A.; Haak, J.R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J Chem Phys. 1984, 81(8), 3684–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryckaert, J.-P.; Ciccotti, G.; Berendsen, H.J.C. Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J Comput Phys. 1977, 23(3), 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrinello, M.; Rahman, A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: A new molecular dynamics method. J Appl Phys. 1981, 52(12), 7182–7190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussi, G.; Donadio, D.; Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J Chem Phys. 2007, 126(1), 014101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, B.; Bekker, H.; Berendsen, H.J.C.; Fraaije, J.G.E.M. LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J Comput Chem. 1997, 18(12), 1463–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, B. P-LINCS: A Parallel Linear Constraint Solver for Molecular Simulation. J Chem Theory Comput. 2008, 4(1), 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andricioaei, I.; Karplus, M. On the calculation of entropy from covariance matrices of the atomic fluctuations. J Chem Phys. 2001, 115(14), 6289–6292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadei, A.; Ceruso, M.A.; Di Nola, A. On the convergence of the conformational coordinates basis set obtained by the essential dynamics analysis of proteins’ molecular dynamics simulations. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics 1999, 36 (4), 419-424.

- Hayward, S.; de Groot, B. l.; Kukol, A. Normal Modes and Essential Dynamics. In Molecular Modeling of Proteins; Humana Press: Totowa, 2008; Volume 443, pp. 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Python Software Foundation. Python.org. https://www.python.org (accessed August 15, 2023).

- R Core Team. The R project for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org (accessed Aug 14, 2023).

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. IEEE 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhaber, F.; Lijnzaad, P.; Argos, P.; Sander, C.; Scharf, M. The double cubic lattice method: Efficient approaches to numerical integration of surface area and volume and to dot surface contouring of molecular assemblies. J Comput Chem. 1995, 16(3), 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Word, J.M. All-atom small probe contact surface analysis: an information-rich description of molecular goodness-of-fit; PhD Thesis; Duke University: Durham, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Sander, J.; Xiaowei, X. A density-based algorithm for discovering clusters in large spatial databases with noise. 2nd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, Portland, 1996.

- Tan, P.N.; Steinbach, M.; Kumar, V. Cluster Analysis Basic Concepts and Algorithms. In Introduction to Data Mining, 2nd ed.; Pearson Addison Wesley: Boston, 2005; pp. 487–568. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, P.N.; Steinbach, M.; Kumar, V. Cluster Analysis Additional Issues and Algorithms. In Introduction to Data Mining, 2nd ed.; Pearson Addison Wesley: Boston, 2005; pp. 569–650. [Google Scholar]

- The Perl Foundation. Perl Website. https://www.perl.org (accessed August 30, 2023).

- Navidi, W. The Binomial Distribution. In Statistics for Engineers and Scientists; McGraw Hill: New York, New York, 2015; pp. 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, K. On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling. Philosophical Mag. 1900, 50, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marascuilo, L.A., M. M. Nonparametric post hoc comparisons for trend. Psychological Bulletin 1967, 67, 400–412. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Comparing multiple proportions: The Marascuillo procedure, 2012. NIST/SEMATECH e-Handbook of Statistical Methods. https://www.itl.nist.gov/div898/handbook/prc/section4/prc464.htm (accessed September 6, 2023).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. NIST/SEMATECH Engineering Statistics Handbook. https://www.itl.nist.gov/div898/handbook/eda/section3/eda35f.htm (accessed September 2 023).

- Mitternacht, S. FreeSASA: An open source C library for solvent accessible surface area calculations. F1000Research 2016, 5, 189–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; Kern, R.; Picus, M.; Hoyer, S.; van Kerkwijk, M.H.; Brett, M.; Haldane, A.; del Río, J.F.; Wiebe, M.; Peterson, P.; Gérard-Marchant, P.; Sheppard, K.; Reddy, T.; Weckesser, W.; Abbasi, H.; Gohlke, C.; Oliphant, T.E. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585(7825), 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallat, R. Pingouin: statistics in Python. The Journal of Open Source Software 2018, 3(31), 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A. The Correlation between Relatives on the Supposition of Mendelian Inheritance. Earth Environ Sci Trans R Soc Edinb. 1919, 52(2), 399–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A. On the “Probable Error” of a Coefficient of Correlation Deduced from a Small Sample. Metron 1921, 1, 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffé, H. A method for judging all contrasts in the analysis of variance. Biometrika 1953, 40 (1-2), 87-110.

- McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. 9th Python In Science Conference, 2010.

- Vanommeslaeghe, K.; MacKerell, A.D.J. Automation of the CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) I: Bond Perception and Atom Typing. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 2012, 52(12), 3144–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanommeslaeghe, K.; Raman, E.P.; MacKerell, A.D.J. Automation of the CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) II: Assignment of Bonded Parameters and Partial Atomic Charges. J Chem Inform Mod. 2012, 52(12), 3155–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; He, X.; Vanommeslaeghe, K.; MacKerell, A.D.J. Extension of the CHARMM general force field to sulfonyl-containing compounds and its utility in biomolecular simulations. J Comp Chem. 2012, 33(31), 2451–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Vorobyov, I.; Allen, T.W. Potential of Mean Force and pKa Profile Calculation for a Lipid Membrane-Exposed Arginine Side Chain. J Phys Chem B. 2008, 112(32), 9574–9587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Vorobyov, I.; Mackerell, A.D.J. Is arginine charged in a membrane? Biophys J. 2008, 15(94), LL11–LL13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| ..Ac-Ala-Xaa-Ala-NH2 | β | α | αL | ε | Cont. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | ρ | ρ | ρ | r | |

| Gly | 0.4917 | 0.0430 | 0.0586 | 0.3596 | 0.0471 |

| Ala | 0.7636 | 0.1743 | 0.0104 | 0.0112 | 0.0405 |

| Val | 0.9086 | 0.0649 | 0.0103 | N/S | 0.0162 |

| Leu | 0.7395 | 0.2105 | 0.0148 | N/S | 0.0352 |

| Ile | 0.8868 | 0.0878 | 0.0094 | N/S | 0.0160 |

| Met | 0.7308 | 0.1987 | 0.0262 | N/S | 0.0443 |

| His:ND1 | 0.7088 | 0.1740 | 0.0672 | 0.0035 | 0.0465 |

| His:NE2 | 0.6600 | 0.1514 | 0.1219 | 0.0337 | 0.0330 |

| Phe | 0.8160 | 0.1096 | 0.0252 | 0.0094 | 0.0397 |

| Tyr | 0.7850 | 0.1441 | 0.0260 | 0.0067 | 0.0382 |

| Trp | 0.8425 | 0.1199 | 0.0057 | N/S | 0.0320 |

| Ser | 0.7517 | 0.1419 | 0.0320 | 0.0212 | 0.0533 |

| Thr | 0.8407 | 0.1198 | 0.0101 | N/S | 0.0294 |

| Cys:H | 0.7795 | 0.1359 | 0.0445 | N/S | 0.0402 |

| Asn | 0.6309 | 0.2149 | 0.1002 | 0.0248 | 0.0293 |

| Gln | 0.6964 | 0.2296 | 0.0338 | N/S | 0.0402 |

| Arg:NE | 0.7806 | 0.1493 | 0.0291 | N/S | 0.0410 |

| Arg:NH | 0.7415 | 0.1953 | 0.0242 | N/S | 0.0389 |

| Asp:H | 0.6281 | 0.2422 | 0.0806 | 0.0166 | 0.0325 |

| Glu:H | 0.7355 | 0.1981 | 0.0305 | N/S | 0.0359 |

| LysN | 0.7304 | 0.1751 | 0.0478 | 0.0056 | 0.0410 |

| Arg | 0.7781 | 0.1705 | 0.0147 | N/S | 0.0367 |

| His+ | 0.5942 | 0.2020 | 0.1073 | N/S | 0.0964 |

| Lys | 0.7530 | 0.1892 | 0.0180 | N/S | 0.0399 |

| Asp | 0.7675 | 0.1728 | 0.0209 | 0.0068 | 0.0320 |

| Glu | 0.8106 | 0.1506 | 0.0110 | N/S | 0.0278 |

| Cys- | 0.7757 | 0.2134 | N/S | N/S | 0.0109 |

| Tyr- | 0.8201 | 0.1228 | 0.0197 | N/S | 0.0374 |

| Cys-Cys | 0.7406 | 0.1690 | 0.0449 | N/S | 0.0455 |

| Pro:cis | 0.7859 | 0.2104 | N/S | N/S | 0.0037 |

| Pro:trans | 0.9204 | 0.0328 | N/S | N/S | 0.0469 |

| Ac-Ala-Xaa-Ala-NH2 | All | β | α | αL | ε | Cont. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SASA/nm2 | SASA/nm2 | SASA/nm2 | SASA/nm2 | SASA/nm2 | SASA/nm2 | |

| Gly | 0.788 ± 0.065 | 0.773 ± 0.049 | 0.899 ± 0.047 | 0.895 ± 0.050 | 0.776 ± 0.056 | 0.799 ± 0.083 |

| Ala | 1.093 ± 0.075 | 1.068 ± 0.0059 | 1.188 ± 0.053 | 1.182 ± 0.058 | 1.105 ± 0.058 | 1.111 ± 0.070 |

| Val | 1.523 ± 0.077 | 1.514 ± 0.070 | 1.643 ± 0.061 | 1.516 ± 0.060 | N/S | 1.585 ± 0.087 |

| Leu | 1.857 ± 0.087 | 1.829 ± 0.075 | 1.946 ± 0.060 | 1.940 ± 0.077 | N/S | 1.861 ± 0.090 |

| Ile | 1.749 ± 0.084 | 1.736 ± 0.075 | 1.873 ± 0.069 | 1.727 ± 0.072 | N/S | 1.790 ± 0.084 |

| Met | 1.895 ± 0.117 | 1.864 ± 0.108 | 1.990 ± 0.087 | 2.006 ± 0.096 | N/S | 1.913 ± 0.107 |

| His:ND1 | 1.898 ± 0.100 | 1.864 ± 0.086 | 1.992 ± 0.071 | 2.003 ± 0.075 | 1.890 ± 0.069 | 1.901 ± 0.096 |

| His:NE2 | 1.902 ± 0.101 | 1.867 ± 0.087 | 1.973 ± 0.087 | 2.003 ± 0.079 | 1.887 ± 0.071 | 1.914 ± 0.099 |

| Phe | 2.116 ± 0.099 | 2.097 ± 0.087 | 2.225 ± 0.090 | 2.240 ± 0.086 | 2.094 ± 0.070 | 2.140 ± 0.105 |

| Tyr | 2.258 ± 0.101 | 2.233 ± 0.087 | 2.368 ± 0.087 | 2.384 ± 0.083 | 2.243 ± 0.069 | 2.284 ± 0.102 |

| Trp | 2.513 ± 0.108 | 2.491 ± 0.093 | 2.655 ± 0.099 | 2.486 ± 0.069 | N/S | 2.555 ± 0.108 |

| Ser | 1.209 ± 0.075 | 1.187 ± 0.063 | 1.298 ± 0.055 | 1.299 ± 0.062 | 1.211 ± 0.060 | 1.224 ± 0.074 |

| Thr | 1.415 ± 0.081 | 1.397 ± 0.068 | 1.532 ± 0.059 | 1.401 ± 0.061 | N/S | 1.454 ± 0.088 |

| Cys:H | 1.360 ± 0.080 | 1.338 ± 0.067 | 1.456 ± 0.062 | 1.445 ± 0.072 | N/S | 1.370 ± 0.081 |

| Asn | 1.584 ± 0.085 | 1.549 ± 0.072 | 1.654 ± 0.063 | 1.656 ± 0.068 | 1.551 ± 0.064 | 1.600 ± 0.084 |

| Gln | 1.800 ± 0.105 | 1.767 ± 0.095 | 1.884 ± 0.076 | 1.902 ± 0.089 | N/S | 1.808 ± 0.106 |

| Arg:NE | 2.419 ± 0.128 | 2.392 ± 0.120 | 2.523 ± 0.102 | 2.552 ± 0.100 | N/S | 2.449 ± 0.125 |

| Arg:NH | 2.421 ± 0.124 | 2.394 ± 0.116 | 2.508 ± 0.104 | 2.524 ± 0.102 | N/S | 2.434 ± 0.120 |

| Asp:H | 1.516 ± 0.090 | 1.476 ± 0.075 | 1.590 ± 0.060 | 1.603 ± 0.067 | 1.496 ± 0.068 | 1.537 ± 0.082 |

| Glu:H | 1.810 ± 0.092 | 1.786 ± 0.083 | 1.888 ± 0.077 | 1.890 ± 0.080 | N/S | 1.820 ± 0.092 |

| LysN | 2.092 ± 0.112 | 2.065 ± 0.103 | 2.182 ± 0.092 | 2.194 ± 0.091 | 2.085 ± 0.091 | 2.116 ± 0.107 |

| Arg | 2.409 ± 0.125 | 2.386 ± 0.119 | 2.503 ± 0.105 | 2.499 ± 0.112 | N/S | 2.425 ± 0.123 |

| His+ | 1.879 ± 0.108 | 1.845 ± 0.092 | 1.928 ± 0.106 | 1.985 ± 0.086 | N/S | 1.872 ± 0.111 |

| Lys | 2.127 ± 0.106 | 2.100 ± 0.096 | 2.217 ± 0.087 | 2.232 ± 0.090 | N/S | 2.144 ± 0.104 |

| Asp | 1.480 ± 0.079 | 1.455 ± 0.063 | 1.574 ± 0.065 | 1.575 ± 0.057 | 1.477 ± 0.055 | 1.502 ± 0.079 |

| Glu | 1.774 ± 0.084 | 1.753 ± 0.072 | 1.871 ± 0.069 | 1.878 ± 0.064 | N/S | 1.807 ± 0.084 |

| Cys- | 1.375 ± 0.082 | 1.350 ± 0.065 | 1.469 ± 0.067 | N/S | N/S | 1.379 ± 0.083 |

| Tyr- | 2.205 ± 0.109 | 2.181 ± 0.097 | 2.320 ± 0.094 | 2.358 ± 0.065 | N/S | 2.255 ± 0.093 |

| Cys-Cys | 0.753 ± 0.141 | 0.735 ± 0.134 | 0.796 ± 0.145 | 0.819 ± 0.148 | N/S | 0.761 ± 0.135 |

| Pro:cis | 1.476 ± 0.060 | 1.461 ± 0.055 | 1.533 ± 0.040 | N/S | N/S | 1.482 ± 0.090 |

| Pro:trans | 1.415 ± 0.056 | 1.407 ± 0.047 | 1.534 ± 0.043 | N/S | N/S | 1.489 ± 0.074 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).