1. Introduction

Aortic stenosis (AS) is a common valvular heart disease that disproportionately affects older individuals, with severe cases often necessitating surgical intervention to mitigate symptoms and prolong life [

1]. For patients with symptomatic severe AS, surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) has long been considered the gold standard treatment, offering substantial improvements in quality of life and long-term survival [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. However, the overall success of SAVR can be hindered by patient-prosthesis mismatch (PPM), a phenomenon that occurs when the implanted prosthetic valve is too small in relation to the patient's body size and hemodynamic requirements [

7,

8,

9].

PPM can lead to a range of adverse consequences, including elevated transvalvular gradients, reduced left ventricular mass regression, and increased cardiac workload [

10,

11]. These hemodynamic abnormalities have been linked to poorer clinical outcomes, such as higher rates of mortality, rehospitalization, and heart failure symptoms [

12,

13]. While the impact of PPM on hemodynamics and clinical endpoints has been extensively studied, its potential influence on hemostatic parameters, particularly the von Willebrand factor, remains largely unexplored.

VWF is a multimeric glycoprotein that plays a pivotal role in primary hemostasis by mediating platelet adhesion and aggregation at sites of vascular injury [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Abnormalities in von Willebrand factor levels and function are influenced by aortic stenosis, where they may have a contribution to the development of bleeding or thrombotic complications [

15,

16,

17,

19,

20,

21]. Given the complex interplay between hemodynamic factors and hemostatic pathways, it is plausible that PPM could modulate VWF dynamics in patients undergoing SAVR, potentially impacting their perioperative and long-term outcomes.

Despite the potential significance of this relationship, there is a paucity of data on the effects of PPM on postoperative VWF levels in SAVR patients. A better understanding of how PPM influences VWF dynamics could provide valuable insights into the hemostatic consequences of PPM and guide the development of tailored strategies for optimizing valve selection, perioperative management, and long-term follow-up in this high-risk population.

Von Willebrand factor deficiency may have an impact on the risk of thrombotic or hemorrhagic complications during surgical aortic valve replacement. In patients with severe aortic stenosis, the high shear stress leads to a loss of high molecular weight VWF multimers, which are crucial for platelet adhesion and aggregation. This acquired von Willebrand syndrome can result in an increased bleeding tendency, particularly from mucosal surfaces. Conversely, after valve replacement, the sudden normalization of shear stress can lead to a rapid increase in VWF levels, potentially increasing the risk of thrombotic events. The balance between these opposing risks is delicate and can be further complicated by factors such as cardiopulmonary bypass, which can independently affect VWF levels and platelet function.

To address this knowledge gap, the present prospective study aims to investigate the association between PPM and postoperative VWF levels in patients who undergo SAVR for severe aortic stenosis. Through investigating the relationship between PPM and von Willbrand factor leves, this study seeks to contribute to the growing body of evidence on the multifaceted impact of PPM and inform the development of personalized approaches for improving outcomes and minimizing complications in patients undergoing SAVR.

2. Materials and Methods

Patient Selection and Study Protocol

This prospective investigation recruited 31 patients consecutively diagnosed with severe aortic stenosis who subsequently underwent surgical aortic valve replacement. The study's inclusion criteria mandated the presence of severe AS, confirmed by echocardiographic evaluation, and the patient's suitability for SAVR.

The indication for surgical correction of aortic stenosis was based on established guidelines. Specifically, patients were considered for SAVR if they met the following criteria:

Symptomatic severe AS (aortic valve area < 1.0 cm², mean gradient > 40 mmHg, or peak aortic jet velocity > 4.0 m/s)

Asymptomatic severe AS with left ventricular ejection fraction < 50%

Severe AS undergoing cardiac surgery for other indications

Low-flow/low-grafient Sever AS, in symptomatic patient

Moderate AS undergoing cardiac surgery for other indications

Data Acquisition and Evaluation

A set of preoperative data was gathered for each patient, encompassing demographic information (age and gender), comorbid conditions (hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, valvular pathologies, and aortic disorders), echocardiographic measurements (aortic valve area and mean transvalvular pressure gradient), and relevant laboratory parameters (hemoglobin levels, platelet counts, and coagulation profiles). Records were maintained regarding intraoperative details, with a particular attention to the classification (bioprosthetic or mechanical) and physical specifications of the surgically implanted valve.

Echocardiographic Evaluation and Aortic Stenosis Grading

Transthoracic ultrasound imaging was employed to evaluate the extent of aortic valve narrowing. Upon patient entry, we measured the maximum blood flow speed, calculated the mean pressure gradient through the aortic valve, and determined the functional opening area of the valve. Established guidelines were employed to categorize the severity of aortic stenosis as mild, moderate, or severe [

10,

11].

Prosthetic Valve Characteristics and Patient-Prosthesis Mismatch Assessment

We obtained the effective orifice area (EOA) values for the implanted prosthetic aortic valves by consultating the manufacturer provided charts and existing literature (

Table 1) [

12,

13,

15]. We determined body surface area (BSA) for all patients using the Dubois formula. The calculated BSA was used to calculate the indexed EOA (EOAi) of the prosthesis and the indexed aortic valve area prior to the surgical intervention (SOAi).

The presence and extent of patient-prosthesis mismatch were evaluated based on the criteria put forth by Pibarot and Rahimtoola [

2,

15,

22]. The EOAi of the prosthetic valve was used to classify the severity of PPM into mild (EOAi > 0.85 cm²/m²), moderate (EOAi between 0.65 and 0.85 cm²/m²), and severe (EOAi < 0.65 cm²/m²) categories.

Table 1.

Standard values of EOA for the prosthesis in aortic position. Adapted from [

12,

13,

15,

18].

Table 1.

Standard values of EOA for the prosthesis in aortic position. Adapted from [

12,

13,

15,

18].

| Valve Diameter(mm) |

19 |

21 |

23 |

25 |

| Biological prosthesis |

|

|

|

|

| Medtronic HancockII |

N/A |

1.2 ± 0.2 |

1.3 ± 0.2 |

1.5 ± 0.2 |

| Carpentier-Edwards Perimount |

1.1 ± 0.3 |

1.3 ± 0.3 |

1.5 ± 0.4 |

1.8 ± 0.4 |

| Biocor (Epic) |

1.0 ± 0.3 |

1.3 ± 0.5 |

1.4 ± 0.5 |

1.9 ± 0.7 |

| Mechanical prosthesis |

|

|

|

|

| Carbomedics Standard and Top Hat |

1.0 ± 0.4 |

1.5 ± 0.3 |

1.7 ± 0.3 |

2.0 ± 0.4 |

Blood Sample Collection and von Willebrand Factor Analysis

Blood samples were obtained within a 24-hour window prior to surgery and on the seventh postoperative day. We analyzed blood components using specialized assays: clotting factor VIII serum levels were measured using reagents form Antibodies-online (Limerick, Pennsylvania), von Willebrand factor antigen levels were quantified with kits also sourced from Antibodies-online, and functional activity of von Willebrand factor in response to ristocetin was assessed usign HemosIL reagents (Bedford, Massachusetts).

Statistical Methodology

The normality of the data was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation and interquartile range, while categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Spearman's rank test (Spearman's Rho) was used to assess correlations between variables. For single-variable comparisons, we employed different statistical methods based on data characteristics. Continous variables were analyzed using either the Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney U-test, depending on distribution normality. For discrete or catecorical variables, we applied the chi-squared test to asses group differences. Multivariable analyses, including linear regression and analysis of variance (ANOVA), were performed to identify independent variables influencing continuous outcomes. Statistical significance was set at a p-value < 0.05. All statistical computations were carried out using a specialized software for data analysis and statistical modeling StataBE version 17.0 developed by StataCorp, headquartered in College Station, Texas).

Ethical Considerations

Our research methodology adhered to the ethical guidelines established in the Helsinki Declaration. The Institutional Review Board of the Cardiovascular Institute and University of Medicine “Victor Babes” in Timisoara evaluated and approved our study design (reference: 33/09 December 2019). Before enrollment, each prospective participant was fully informed about the study's purpose and procedures. We secured signed documentation from all subjects, confirming their voluntary participation and consenting to the utilization of their anonymized data in subsequent academic publications.

3. Results

Patient Characteristics and Baseline Data

Our study cohort comprised 31 individuals who received surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR). The demographic profile revealed a female predominance (54.84%) and mean age 66.8 years (SD ± 9.15), ranging from 46 to 79 years old.

All participants exhibited severe AS, as evidenced by a mean aortic valve area of 0.81±0.15 cm² and a mean pressure gradient of 52.24±13.79 mmHg. Mean diameter fo aortic annuli was 2.25±0.20 cm, while mean EF was 48.44±8%.

No significant correlations were found between demographic factors (age, gender, ethnicity) or comorbidities in perioperative changes in von Willebrand factor levels.

Table 2.

Cardiac ultrasound assesment.

Table 2.

Cardiac ultrasound assesment.

| Variable |

Mean |

Min |

Max |

| Ao. Anulus (cm) |

2.25 |

1.9 |

2.7 |

| Pmax (mmHg) |

80.35 |

16 |

134 |

| Pmed (mmHg) |

52.24 |

36 |

90 |

| Valve area (cm2) |

0.81 |

0.55 |

1.2 |

| Indexed valve area (cm2) |

0.43 |

0.28 |

0.58 |

| EF (%) |

48 |

25 |

55 |

| VTD (ml) |

109.87 |

70 |

215 |

Surgical Procedure and Prosthetic Valve Characteristics

The mean prosthesis size was 22.35 mm. The average cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) time and aortic cross-clamp time were 103.13 minutes [IQR: 78-110.5] and 62.35 minutes [IQR: 45-78.5], respectively. The mean intensive care unit stay was 4 days.

Bioprosthetic valves were implanted in 51.61% (n=16), while mechanical valves were used in 48.39% (n=15). The Carbomedics Top Hat was the most frequently utilized valve model (51.61%, n=16), followed by the Edwards Lifesciences CE Perimount (32.26%, n=10). The mean effective orifice area of the aortic prostheses was 1.52 cm² [IQR: 1.3-1.7], with a mean indexed EOA of 0.79 cm²/m² [IQR: 0.71-0.92].

Table 3.

Intraprocedural and postprocedural outcomes.

Table 3.

Intraprocedural and postprocedural outcomes.

| |

Mean |

Median |

Q1 |

Q3 |

| Prosthesis size |

22.35 |

23 |

21 |

23 |

| CBP time (min) |

103.13 |

94.5 |

78 |

110.5 |

| Cross-clamp time (min) |

62.35 |

57 |

45 |

78.5 |

| Drainage (ml) |

377.69 |

310 |

230 |

450 |

| Days ICU |

4 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

| Days postprocedural |

5.96 |

6 |

5 |

7 |

In our cohort postoperative bleeding was quantified within the first 24 hours following the procedure. The mean drainage was 377.69 ml [IQR: 230-450]. Notably, our analysis revealed a significant inverse relationship between preoperative von Willebrand factor antigen levels and postoperative drainage. Specifically, baseline vWF:Ag emerged as an independent negative predictor of bleeding volume.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of factors influencing bleeding.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of factors influencing bleeding.

| |

Coefficient |

95% CI |

p |

| Initial Von Willberand factor antigen levels |

-1.12 |

-2.09 - -0.14 |

0.02 |

| Initial factor VIII levels |

0.80 |

-0.38 - 1.98 |

0.17 |

Patient-Prosthesis Mismatch

PPM, defined as an indexed EOA < 0.85 cm²/m² BSA, was observed in 61.29% (n=19) of patients. We graded PPM into three categories: no/insignificant PPM(EOAi>0.85 cm

2/m

2), moderate PPM (EOAi 0.65-0.85 cm

2/m

2), and severe PPM (EOAi<0.65 cm

2/m

2(

Table 5).

Statistical analysis revealed no significant association between patient-prosthesis mismatch and postoperative levels of VWF antigen. Von Willebrand factor antigen concentrations demonstrated comparable distributions in both cohorts (285.43IU/dL [IQR:135.65-382.9] versus 293.30IU/dL [IQR:222.9-345.4], p=0.88). Similarly, von Willebrand factor activity exhibited no statistically meaningful difference (178.33% [IQR:119.2-130.9] versus 204.76% [IQR:115.8-399.2], p=0.56). Levels of Factor VIII remained consistent irrespective of prosthetic fit (100.38 IU/dL [IQR:75.3-111.5] versus 97.10 IU/dL [IQR:80.4-111.2], p=0.79).

Further analysis of PPM severity subgroups also showed no statistically significant differences in these parameters (

Table 6).

Anticoagulation and Thrombotic Events

Anticoagulation protocols were standardized for all patients. Preoperatively, patients on oral anticoagulants were bridged with low molecular weight heparin. Postoperatively, patients with mechanical valves were started on warfarin with a target INR of 2.5-3.5, while those with bioprosthetic valves received aspirin 75-100 mg daily unless otherwise indicated. No clinically significant thromboses were observed during the immediate postoperative period, despite the observed increase in von Willebrand factor levels. Long-term follow-up for thrombotic events was beyond the scope of this study.

Von Willebrand Factor

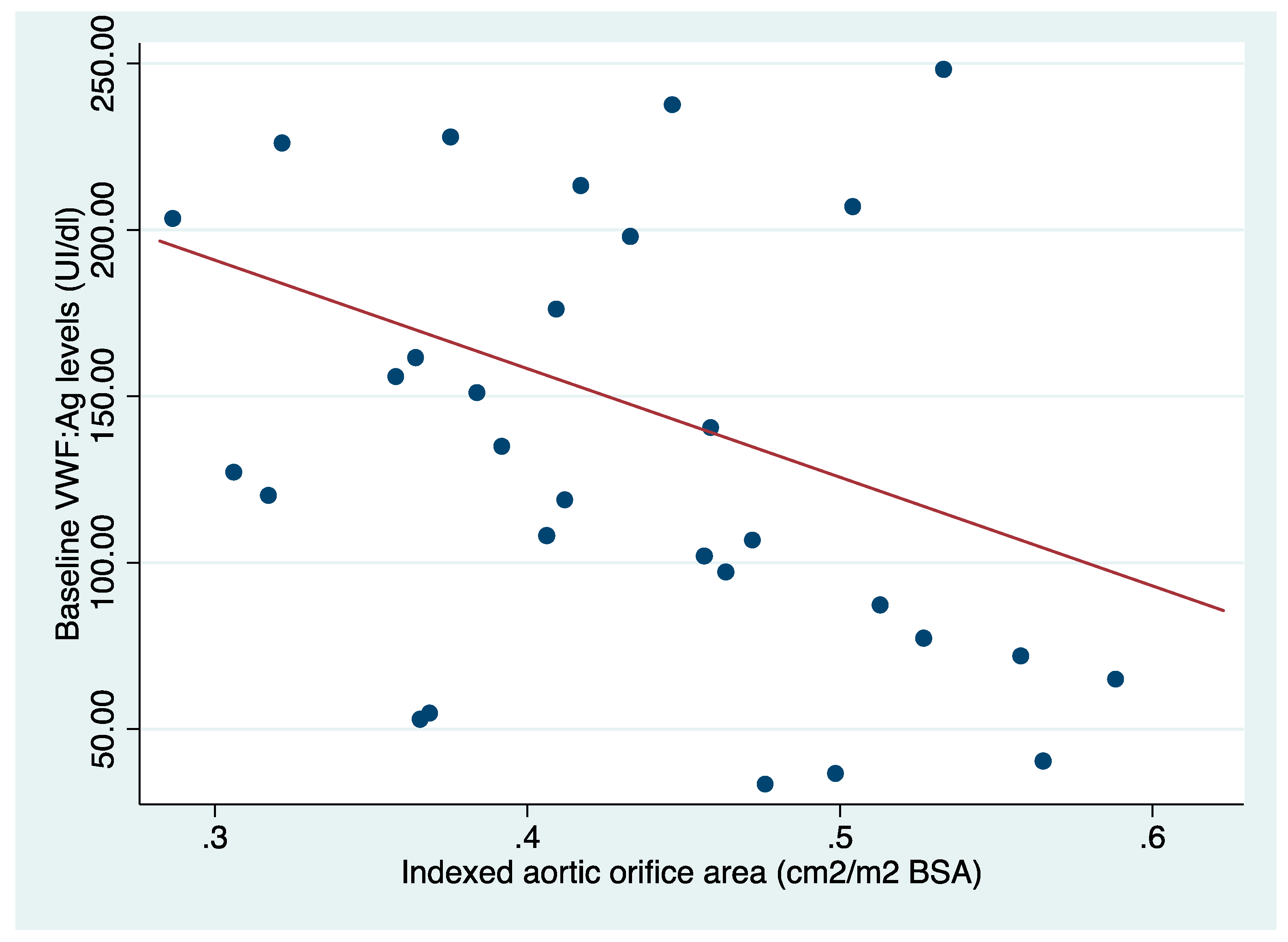

The mean preoperative VWF antigen (VWF:Ag) level was 131.37 ± 64.82 IU/dL [IQR: 77.3-198]. Preoperative VWF:Ag levels showed a significant inverse correlation with the SOAi (rho= -0.36, p <0.04). Post-surgical assessment revealed a marked elevation in von Willebrand factor antigen concentrations, with levels rising to 311.01 IU/dL [IQR: 172.2-387] (p<0.01). Notably, this increase demonstrated no significant correlation with the size-adjusted effective orifice area of the implanted valve prosthesis (Spearman's rho=-0.01, p=0.95).

VWF activity also increased significantly from 79.25% [IQR: 45.9-122] at baseline to 190.41% [IQR: 120-135.4] (p<0.01). However, no significant differences were observed in Factor VIII levels (95.3 IU/dL [IQR: 61.9-105.4] vs. 100.18 IU/dL [IQR: 79-111.2], p=0.21) or VWF:Ag/VWF:Activity ratio (0.66 [IQR: 0.43-0.78] vs. 0.75 [IQR: 0.38-0.79], p=0.33) following the procedure.

Figure 1.

Correlation between initial levels of von Willebrand factor antigen and indexed aortic valve area.

Figure 1.

Correlation between initial levels of von Willebrand factor antigen and indexed aortic valve area.

At baseline, patients with blood group O had significantly lower VWF activity levels compared to those with a non-O blood group (1.20 ± 0.57 vs. 2.48 ± 1.98, p=0.03). However, no significant differences were found in preoperative VWF:Ag levels (99.51 IU/dL [IQR: 56.2-137.4] vs. 142.45 IU/dL [IQR:87.3-207], p=0.09) or levels of factor VIII (76.4 IU/dL [IQR:55.5-91.3] vs. 101.87 IU/dL [IQR: 66.6-120.6], p=0.42) between the two groups. These differences in VWF activity disappeared one week after SAVR (2.38 [IQR: 1.04-3.37] vs. 2.08 [IQR: 1.27-2.60], p=0.48), and no significant differences were observed in postoperative VWF:Ag levels (393.25 IU/dL [IQR: 212.3-506] vs. 282.40 IU/dL [IQR: 167.8-318.4], p=0.13) or Factor VIII levels (94 IU/dL [IQR: 69.5-92.3] vs. 102.33 IU/dL [IQR: 83.8-113.2], p=0.56) between blood group O and non-O patients.

To assess the potential impact of cardiopulmonary bypass on VWF levels, we analyzed the relationship between CPB times and the increase in VWF:Ag levels. We found no significant correlation between CPB duration and the magnitude of VWF:Ag increase (Spearman's rho = 0.20, p = 0.28). These data suggest that the observed increase in VWF levels is likely primarily due to the normalization of shear stress following valve replacement, rather than being influenced by the cardiopulmonary bypass.

4. Discussion

Aortic stenosis is a well-known cause of acquired von Willebrand syndrome (AVWS), particularly type 2A, which is characterized by a deficiency in high-molecular-weight multimers (HMWM) of von Willebrand factor [

15,

16,

17,

18,

23]. The elevated shear stress caused by the narrowed valve orifice in AS leads to structural changes in the VWF molecule, making it more susceptible to proteolysis [

15,

16,

17,

18,

23]. As a result, patients with severe AS may experience a significant reduction in HMWM VWF levels, which can increase the risk of bleeding complications [

15,

16,

17,

18,

24]. In fact, studies have shown that individuals with severe AS may have up to a 50% decrease in HMWM VWF levels compared to healthy individuals [

15,

19].

The severity of AVWS in AS patients has been found to correlate with the degree of valve stenosis and the transvalvular pressure gradient [

18,

19,

25]. This highlights a crucial implication of high shear stress in HMWM of von Willebrand factor degradation .

Interestingly, systemic abnormalities in VWF have been linked to the pressure gradient across prosthetic valves following aortic valve replacement [

15]. This suggests that patients who develop PPM after SAVR may continue to experience elevated shear stress, even if the prosthetic valve is functioning properly. Consequently, PPM could potentially contribute to the persistence or recurrence of AVWS even after valve replacement surgery [

15,

18].

The VWF Dynamics after SAVR

We observed a significant increase in VWF antigen levels following SAVR, indicating an improvement in hemostatic function. The mean preoperative VWF level was low at 131.37 ± 64.82 IU/dL [IQR: 77.3-198], reflecting the hemostatic impairment caused by AS. After surgery, VWF levels increased to 311.01 UI/dl ± 176.77 IU/dL [IQR: 172.2-387], suggesting a significant improvement. The resulted data confirms other studies findings that removing the stenosis in the aortic valve will decrease the degradation of von Willebrand factor [

7,

8,

15,

18,

19].

Long CBP time, especially in associated procedures, could increase the risk of bleeding due to CPB-induced platelet dysfunction [

26]. Although this factor does not directly influence VWF levels, it highlights the complex nature of hemostasis management in patients undergoing SAVR.

Impact of Patient-Prosthesis Mismatch

Patient-prosthesis mismatch is a significant concern in aortic valve replacement procedures, as it can lead to suboptimal hemodynamics, increased shear stress on the prosthetic valve, and a higher risk of acquired von Willebrand factor deficiency [

27,

28,

29]. PPM occurs when the effective orifice area of the implanted valve is smaller than that of the native stenotic valve, a concept first introduced by Rahimtoola in 1978 [

27,

28,

29]. The prevalence of moderate PPM is estimated to range between 20% and 70%, while severe PPM occurs in 2% to 10% of cases [

30].

When selecting the optimal prosthesis size, the effective orifice area is considered a more reliable measure than the geometric orifice area [

2,

18]. Bioprosthetic valves typically have smaller diameters and EOAs compared to mechanical prostheses or stentless prostheses [

15,

18,

27,

31].

Our study of 31 patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement revealed a significant incidence of patient-prosthesis mismatch, affecting more than half of the cohort. This high prevalence of PPM can be attributed to a complex interplay of patient characteristics and surgical considerations.

The group presented with distinctive anthropometric features that contributed to the challenge of achieving optimal prosthesis sizing. Averege height was 1.67±0.08 m, weighting 82.25±20.9 kg, with a calulates BSA of 1.90±0.24 m². Crucially, their aortic annulus had a mean diameter size of 2.25±0.20 cm, beeing insufficient related to their calculated BSA (

Table 7). This disparity between a small aortic root and high BSA complicated the prosthesis selection process.

To address the varied needs of our SAVR patients, we employed a range of prosthetic valves. Bioprosthetic options included the Hancock II (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and the Edwards Perimount (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA). The Hancock II, a porcine valve, was used in 23 mm and 25 mm sizes, offering effective orifice areas of 1.3 cm² and 1.5 cm², respectively. The Edwards Perimount, a bovine pericardial valve, was used in sizes 19-25mm , with EOAs spanning from 1.1-1.8 cm². For patients receiving mechanical valves, we utilized the Carbomedics Standard and Top Hat models (LivaNova, London, UK) in sizes 21-25mm, providing EOAs between 1.5-2.3 cm².

The selection of appropriate valve size involved a delicate balance between minimizing PPM and avoiding more extensive surgical procedures like aortic root enlargement, which could potentially increase perioperative risks. Our strategy prioritized the safety of the patient and clinical improvement, sometimes engaging a grade of patient-prosthesis mismatch when the alternative poses a greater risks.

Interestingly, our analysis revealed that PPM did not significantly impact postoperative von Willebrand factor levels, VWF activity, or factor VIII levels in the short term. Furher analysis of PPM severity subgroups(no/insignificant, moderate, severe) also showed no statistically significant differences in these parameters. This finding contradicts some previous studies [

7,

9,

15] that suggested a relationship between PPM and VWF dynamics. The discrepancy might be attributed to the immediate hemostatic benefits of aortic valve replacement overshadowing any potential short-term effects of PPM on these parameters.

To further explore the implications of PPM in our cohort, we conducted additional analyses. We stratified patients based on the severity of PPM and examined correlations between the degree of mismatch and various clinical outcomes.

Our findings underscore the complexity of managing PPM. While the short-term VWF levels appeared unaffected, the long-term implications of PPM on hemostatic function, valve durability, and overall clinical outcomes remain uncertain. This highlights the need for extended follow-up studies to elucidate the full impact of PPM over time.

This observation suggests that the hemostatic recovery process following SAVR may be robust enough to overcome both blood group-related variations in VWF levels and any potential influences of PPM. It's important to note that this finding contradicts some earlier hypotheses that PPM might interfere with the normalization of hemostatic parameters post-surgery.

Our analysis revealed that baseline VWF levels, rather than the presence or severity of PPM, served as an independent negative predictor of postoperative bleeding. Specifically, patients with higher preoperative VWF levels tended to experience less postoperative bleeding, irrespective of whether they developed PPM.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study provides insights into the impact of patient-prosthesis mismatch on von Willebrand factor dynamics in patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis. While we did not observe a significant association between PPM and postoperative VWF levels in the short term, it is crucial to acknowledge that the persistent high shear stress caused by PPM could potentially lead to the re-emergence of acquired von Willebrand syndrome over time. Future result of our long follow-up study of this patients is warranted to elucidate the long-term implications of PPM on hemostatic function and clinical outcomes.

6. Limitations

Our investigation into patient-prosthesis mismatch among the 31 surgical aortic valve replacement patients faced several constraints that warrant consideration when interpreting the results.

A primary limitation was the short-term nature of our follow-up. This restricted timeframe allowed us to capture only the immediate post-operative effects of PPM, potentially missing longer-term hemostatic and clinical implications. The acute post-surgical period may not fully reflect the ongoing impact of PPM on valve function, hemodynamics, and patient outcomes. Extended observation periods in future studies could reveal whether PPM leads to progressive changes in von Willebrand factor levels or clinical endpoints that were not apparent in our short-term analysis.

The modest sample size of 31 patients, while providing valuable insights, limits the statistical power and generalizability of our findings. This constraint may have obscured subtle associations between PPM and VWF levels or clinical outcomes. Larger cohorts would enable more robust subgroup analyses, potentially uncovering PPM effects that vary based on factors such as prosthesis type, size, or patient characteristics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.G. and H.F..; methodology, A.E.G., H.F., A.A.,; software, H.F., A.E.G..; validation, A.E.G., H.F., A.A.; formal analysis, A.A.,H.F.; investigation, A.E.G., H.F..; resources, A.A., H.F.; data curation, A.E.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.E.G., H.F.; writing—review and editing, A.E.G, H.F., A.A.,; visualization, A.E.G., H.F.; supervision, H.F., A.A; project administration, A.E.G.; funding acquisition, U.M.F.V.B.T.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Part of the necessary reagent for this study were funded by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Victor Babes” Timisoara. The APC was funded by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Victor Babes” Timisoara.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Our research methodology adhered to the ethical guidelines established in the Helsinki Declaration. The Institutional Review Board of the Cardiovascular Institute and University of Medicine “Victor Babes” in Timisoara evaluated and approved our study design (reference: 33/09 December 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Before enrollment, each prospective participant was fully informed about the study's purpose and procedures. We secured signed documentation from all subjects, confirming their voluntary participation and consenting to the utilization of their anonymized data in subsequent academic publications.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Baumgartner, H.; Walther, T. Aortic Stenosis. In The ESC Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine; Baumgartner, H., Camm, A.J., Lüscher, T.F., Maurer, G., Serruys, P.W., Eds.; Oxford University Press, 2018; p. 0 ISBN 978-0-19-878490-6.

- Muneretto, C.; Bisleri, G.; Negri, A.; Manfredi, J. The Concept of Patient-Prosthesis Mismatch. J Heart Valve Dis 2004, 13, 5.

- Chan, J.; Dimagli, A.; Fudulu, D.P.; Sinha, S.; Narayan, P.; Dong, T.; Angelini, G.D. Trend and Early Outcomes in Isolated Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in the United Kingdom. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 9, 1077279. [CrossRef]

- De La Morena-Barrio, M.E.; Corral, J.; López-García, C.; Jiménez-Díaz, V.A.; Miñano, A.; Juan-Salvadores, P.; Esteve-Pastor, M.A.; Baz-Alonso, J.A.; Rubio, A.M.; Sarabia-Tirado, F.; et al. Contact Pathway in Surgical and Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 887664. [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zheng, J.; Chen, L.; Li, R.; Ma, L.; Ni, Y.; Zhao, H. Impact of Prosthesis–Patient Mismatch on Short-Term Outcomes after Aortic Valve Replacement: A Retrospective Analysis in East China. J Cardiothorac Surg 2017, 12, 42. [CrossRef]

- Živković, I.; Vuković, P.; Krasić, S.; Milutinović, A.; Milić, D.; Milojević, P. MINIMALLY INVASIVE AORTIC VALVE REPLACEMENT VS AORTIC VALVE REPLACEMENT THROUGH MEDIAL STERNOTOMY: PROSPECTIVE RANDOMIZED STUDY. AMM 2019, 58, 97–102. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Tobe, S.; Kawata, M.; Yamaguchi, M. Acquired and Reversible von Willebrand Disease With High Shear Stress Aortic Valve Stenosis. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 2006, 81, 490–494. [CrossRef]

- Vincentelli, A.; Susen, S.; Le Tourneau, T.; Six, I.; Fabre, O.; Juthier, F.; Bauters, A.; Decoene, C.; Goudemand, J.; Prat, A.; et al. Acquired von Willebrand Syndrome in Aortic Stenosis. N Engl J Med 2003, 349, 343–349. [CrossRef]

- Blackshear, J.L.; McRee, C.W.; Safford, R.E.; Pollak, P.M.; Stark, M.E.; Thomas, C.S.; Rivera, C.E.; Wysokinska, E.M.; Chen, D. Von Willebrand Factor Abnormalities and Heyde Syndrome in Dysfunctional Heart Valve Prostheses. JAMA Cardiology 2016, 1, 198. [CrossRef]

- Messika-Zeitoun, D.; Lloyd’, ’Guy Aortic Valve Stenosis: Evaluation and Management of Patients with Discordant Gra. European Society of Cardiology 2018, 15, 8.

- Manzo, R.; Ilardi, F.; Nappa, D.; Mariani, A.; Angellotti, D.; Immobile Molaro, M.; Sgherzi, G.; Castiello, D.; Simonetti, F.; Santoro, C.; et al. Echocardiographic Evaluation of Aortic Stenosis: A Comprehensive Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2527. [CrossRef]

- Lancellotti, P.; Pibarot, P.; Chambers, J.; Edvardsen, T.; Delgado, V.; Dulgheru, R.; Pepi, M.; Cosyns, B.; Dweck, M.R.; Garbi, M.; et al. Recommendations for the Imaging Assessment of Prosthetic Heart Valves: A Report from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging Endorsed by the Chinese Society of Echocardiography, the Inter-American Society of Echocardiography, and the Brazilian Department of Cardiovascular Imaging †. European Heart Journal – Cardiovascular Imaging 2016, 17, 589–590. [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.T.; Leipsic, J.; Douglas, P.S.; Jaber, W.A.; Weissman, N.J.; Pibarot, P.; Blanke, P.; Oh, J.K. Comprehensive Echocardiographic Assessment of Normal Transcatheter Valve Function. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2019, 12, 25–34. [CrossRef]

- Peyvandi, F.; Garagiola, I.; Baronciani, L. Role of von Willebrand Factor in the Haemostasis. Blood Transfusion 2011, s3–s8. [CrossRef]

- Grigorescu, A.E.; Anghel, A.; Buriman, D.G.; Feier, H. Acquired Von Willebrand Factor Deficiency at Patient-Prosthesis Mismatch after AVR Procedure—A Narrative Review. Medicina 2023, 59, 954. [CrossRef]

- Vučić, M.; Veličković, S.; Lilić, B. BLEEDING ASSESSMENT TOOLS. AMM 2023, 62, 117–126. [CrossRef]

- Milić, D.; Lazarević, M.; Golubović, M.; Perić, V.; Kamenov, A.; Stojiljković, V.; Stošić, M.; Živić, S.; Milić, I.; Spasić, D. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF IMPEDANCE AGGREGOMETRY IN CARDIAC SURGERY. AMM 2024, 63, 05–13. [CrossRef]

- Grigorescu, A.E.; Anghel, A.; Koch, C.; Horhat, F.G.; Savescu, D.; Feier, H. Von Willebrand Factor Dynamics in Patients with Aortic Stenosis Undergoing Surgical and Transcatheter Valve Replacement. Life 2024, 14, 934. [CrossRef]

- Frank, R.D.; Lanzmich, R.; Haager, P.K.; Budde, U. Severe Aortic Valve Stenosis: Sustained Cure of Acquired von Willebrand Syndrome After Surgical Valve Replacement. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2017, 23, 229–234. [CrossRef]

- Casonato, A.; Galletta, E.; Cella, G.; Barbon, G.; Daidone, V. Acquired von Willebrand Syndrome Hiding Inherited von Willebrand Disease Can Explain Severe Bleeding in Patients With Aortic Stenosis. ATVB 2020, 40, 2187–2194. [CrossRef]

- Bańka, P.; Wybraniec, M.; Bochenek, T.; Gruchlik, B.; Burchacka, A.; Swinarew, A.; Mizia-Stec, K. Influence of Aortic Valve Stenosis and Wall Shear Stress on Platelets Function. JCM 2023, 12, 6301. [CrossRef]

- Pibarot, P.; Magne, J.; Leipsic, J.; Côté, N.; Blanke, P.; Thourani, V.H.; Hahn, R. Imaging for Predicting and Assessing Prosthesis-Patient Mismatch After Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2019, 12, 149–162. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health, N.H.L. and B.I. The Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Management of von Willebrand Disease; 2007; p. 126;

- Hillegass, W.B.; Limdi, N.A. Valvular Heart Disease and Acquired Type 2A von Willebrand Syndrome: The “Hemostatic” Waring Blender Syndrome. JAMA Cardiology 2016, 1, 205–206. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, T.; Horiuchi, H.; Imai, M.; Tada, T.; Shiomi, H.; Kuroda, M.; Nishimura, S.; Takahashi, Y.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Tsujimura, A.; et al. Unexpectedly High Prevalence of Acquired von Willebrand Syndrome in Patients with Severe Aortic Stenosis as Evaluated with a Novel Large Multimer Index. J Atheroscler Thromb 2015, 22, 1115–1123. [CrossRef]

- Lazarević, M.; Milić, D.; Golubović, M.; Kostić, T.; Djordjević, M. MONITORING OF HEMOSTASIS DISORDERS IN CARDIAC SURGERY. AMM 2019, 58, 141–151. [CrossRef]

- Pibarot, P. Prosthesis-Patient Mismatch: Definition, Clinical Impact, and Prevention. Heart 2006, 92, 1022–1029. [CrossRef]

- Rahimtoola, S.H. The Problem of Valve Prosthesis-Patient Mismatch. Circulation 1978, 58, 20–24. [CrossRef]

- Taggart, D.P. Prosthesis Patient Mismatch in Aortic Valve Replacement: Possible but Pertinent?The Opinions Expressed in This Article Are Not Necessarily Those of the Editors of the European Heart Journal or of the European Society of Cardiology. European Heart Journal 2006, 27, 644–646. [CrossRef]

- Pibarot, P.; Dumesnil, J.G. Prosthetic Heart Valves: Selection of the Optimal Prosthesis and Long-Term Management. Circulation 2009, 119, 1034–1048. [CrossRef]

- Bonderman, D.; Graf, A.; Kammerlander, A.A.; Kocher, A.; Laufer, G.; Lang, I.M.; Mascherbauer, J. Factors Determining Patient-Prosthesis Mismatch after Aortic Valve Replacement – A Prospective Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e81940. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).