1. Introduction

Patients with osteoarthritis experience walking difficulty due to swelling, pain, or stiffness in the affected joints [

1]. This leads to decreased mobility, which is a cardiovascular (CV) risk factor [

2]. Kendzerska et al. [

2] concluded that increased attention to management of osteoarthritis with the aim of improving mobility may lead to a reduction in CV events. Patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and knee have a higher risk of mortality than does the general population [

3], and major risk factors reported by Nüesch et al. [

3] include pre-existing diabetes, cancer, CV disease (CVD), and gait disturbance. The authors concluded that management of patients with osteoarthritis and gait disturbance should focus not only on increasing physical activity but also on effective treatment of CV risk factors and comorbidities. Arteriosclerosis (AS) plays a main role in hemodynamic dysfunction characterized by excessive pulsation; i.e., CVD [

4]. Therefore, it is important to verify the progression of AS in patients with osteoarthritis. Although no studies to date have provided conclusive results, several systematic multicenter analyses have revealed correlations between AS and osteoarthritis [

5,

6,

7]. The cardio-ankle vascular index (CAVI) is a marker of arterial stiffness based on stiffness parameter β and was developed in 2004 [

8]. Measurement of the CAVI is simple and well-standardized, and its reproducibility and accuracy are acceptable [

4]. Thus, the CAVI is a promising diagnostic tool for evaluating arterial stiffness [

9]. In addition, a recent meta-analysis of the Asian population confirmed that the CAVI is an independent risk factor for CVD [

10].

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a reliable procedure for pain relief and functional improvement in patients with knee osteoarthritis [

11,

12,

13]. Comorbidities, rather than age, are responsible for the increase in postoperative morbidity after TKA, and preoperative risk assessment should be optimized to reduce complications [

14]. To the authors’ knowledge, however, preoperative evaluation of AS (one of the comorbidities in patients undergoing TKA) using the CAVI has not been performed. Preoperative assessment of the severity of AS in patients with osteoarthritis is beneficial to verify the correlations between AS and osteoarthritis and to take measures against AS during the TKA procedure and in the early postoperative period.

Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to evaluate the CAVI in patients with osteoarthritis before TKA and to identify influential factors. The clinical significance of this study is that it will clarify the correlation between knee osteoarthritis requiring TKA and the degree of preoperative AS while identifying those patients for whom AS interventions are necessary before TKA.

2. Materials and Methods

This prospective study was conducted at our institute from May 2011 to June 2022. Informed consent was obtained from all patients after a discussion of the study, which included a description of the protocol and possible CAVI measurement-related complications. The institutional review board approved the study before commencement. In total, 209 consecutive patients (251 knees) undergoing TKA were investigated. The preoperative diagnosis indicating TKA was osteoarthritis. Patients who had undergone revision arthroplasties or previous tibial osteotomies and patients with rheumatoid arthritis were excluded.

The following preoperative factors were analyzed: sex, age, body mass index (BMI), body weight (BW), blood cholesterol level, blood triglyceride level, smoking history, diabetes mellitus, hypertension (all of which have been previously reported to affect the CAVI [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]), body height, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade [

20], Kellgren–Lawrence (KL) classification [

21], Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) knee score [

22], and knee range of motion. The severity of knee osteoarthritis was radiographically scaled using the KL grading system as follows: very mild (grade I), mild (grade II), moderate (grade III), and severe (grade IV) [

21]. All TKAs were evaluated using the HSS knee score [

22], which is not a patient-derived score but a physician-derived score. The HSS knee score is divided into seven categories: pain, function, range of motion, muscle strength, flexion deformity, instability, and subtraction. The patients’ clinical backgrounds are summarized in

Table 1.

2.1. Measurement of CAVI

The CAVI was measured by the standardized method using a noninvasive blood pressure-independent device (VaSera VS-1 3000; Fukuda Denshi, Tokyo, Japan) [

23] at 1 day before surgery. The examination was performed in a room in which a standard temperature was maintained. In brief, CAVI measurements were performed in the supine position. Cuffs were applied bilaterally to the upper arms and lower legs superior to the ankles. Electrocardiogram electrodes and a microphone were placed on both wrists, both ankles, and the sternum. An electrocardiogram, blood pressure, and waveforms of the brachial and ankle arteries were measured (

Figure 1). The pulse wave velocity (PWV) was calculated by measuring the time between the closing sound of the aortic valve, the notch of the brachial pulse wave, and the ankle pulse wave. Using this value, the CAVI was calculated by the following equation: CAVI = 2ρ / (systolic blood pressure − diastolic blood pressure) × (ln systolic blood pressure / diastolic blood pressure) × PWV

2, where ρ = blood viscosity. The CAVI cut-off values of 8 and 9 were proposed by the Japan Society for Vascular Failure (<8, normal; 8 to <9, borderline; and ≥9, abnormal) [

24].

2.2. Reproducibility

To eliminate interobserver variability, all tests were performed by the same observer. Test–retest reliability was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficients, which were performed by the same observer on 30 patients at 1-month intervals. The intraclass correlation coefficient was calculated to be 0.788 (0.603–0.898).

2.3. Statistical analysis

Because data for certain variables did not pass the Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test or Shapiro–Wilk normality test, we used the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test and Spearman’s rank correlation test. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to examine factors related to the preoperative CAVI. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to investigate the association between the preoperative CAVI and each variable. The strength of the correlation of the rank coefficients was defined as strong (0.70–1.00), moderate (0.40–0.69), or weak (0.20–0.39). The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to determine differences in the CAVI between two groups. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to identify variables significantly associated with the preoperative CAVI. Multiple linear regression models were constructed by entering all variables shown in

Table 1, and variables significantly associated with the preoperative CAVI were selected using the stepwise selection method. In all tests, a p value of <0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 23 (IBM Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Values are expressed as median (25%, 75% percentile) (minimum–maximum).

3. Results

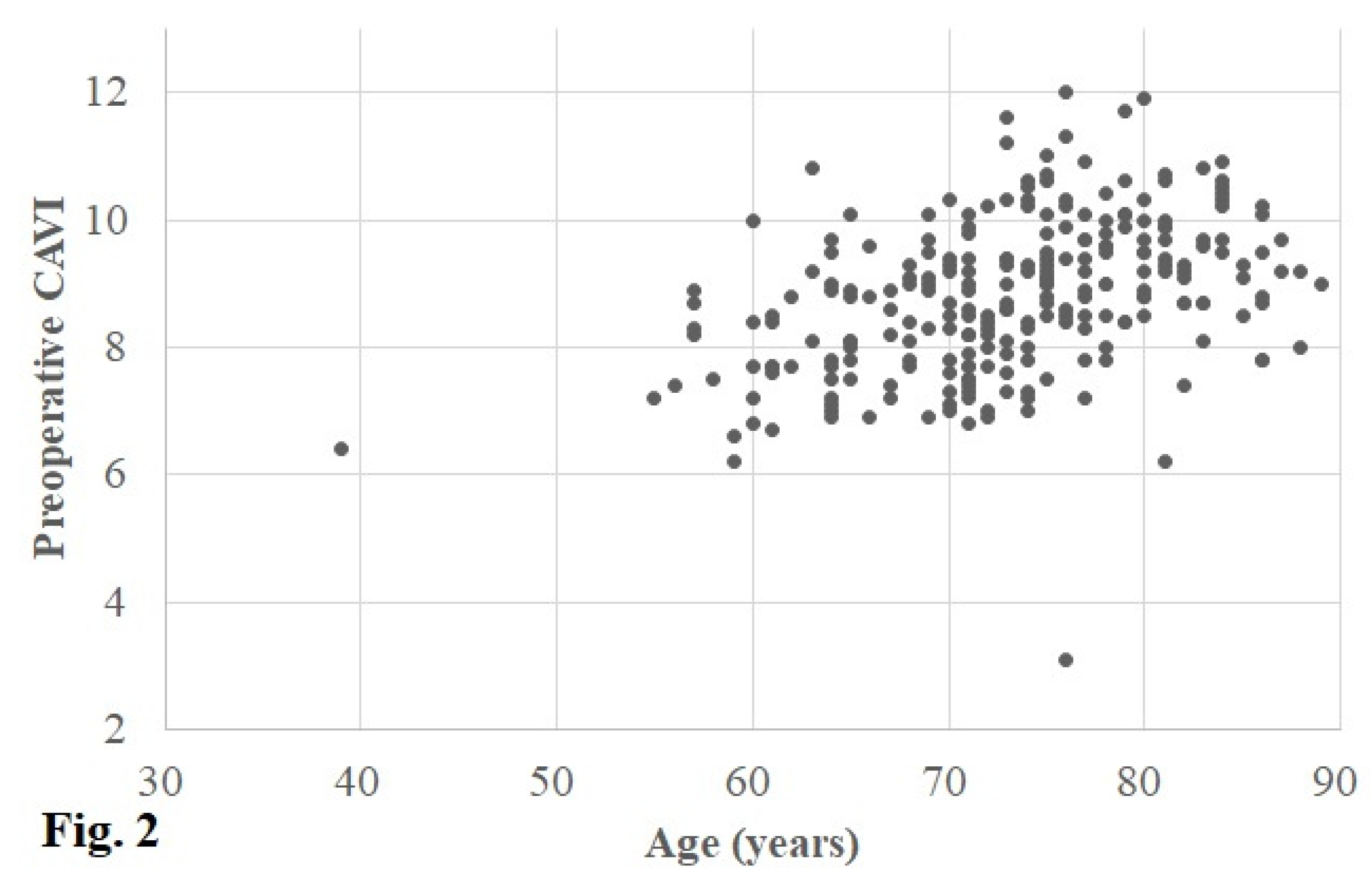

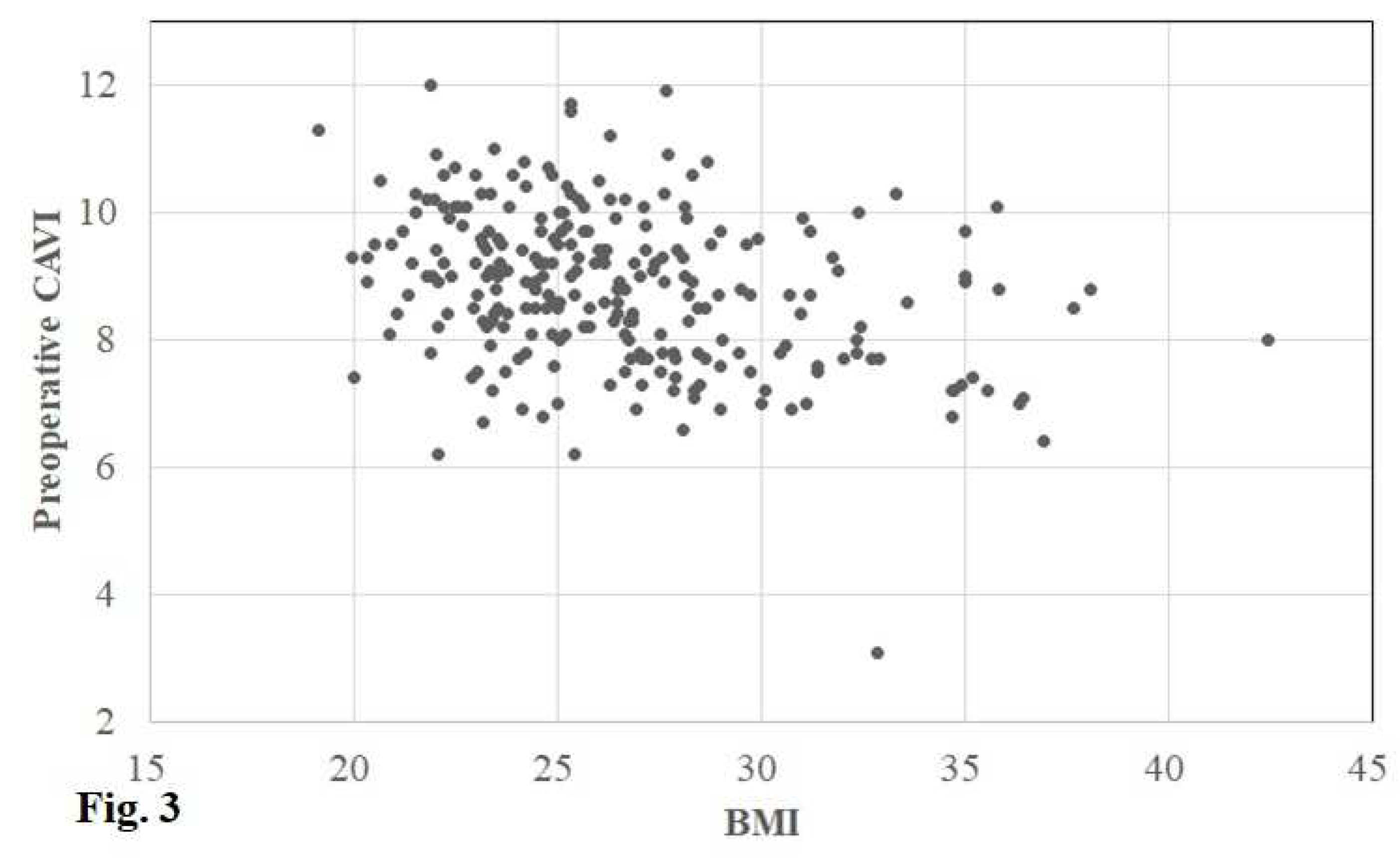

The preoperative CAVI in the operative and contralateral knee was 8.9 (8.0, 9.7) (3.1–12.0) and 8.9 (8.0, 9.7) (3.1–13.2), respectively. In accordance with the cut-off values of the CAVI, the CAVI was defined as normal in 62 (25%) knees, borderline in 71 (28%), and abnormal in 118 (47%) (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

According to the univariate analyses using Spearman’s correlation coefficient for continuous variables, there was a moderate positive correlation between age and the preoperative CAVI (r = 0.451, p < 0.001) (

Figure 2) and a weak negative correlation between BW/BMI and the CAVI (r = −0.306/−0.319, p < 0.001 / p < 0.001) (

Table 2) (

Figure 3). However, the other study variables (both continuous and discrete) showed no significant correlations (

Table 2,

Table 3).

Finally, based on the multivariate analyses using multiple linear regression analysis with stepwise variable selection, age and BMI were significantly correlated with the preoperative CAVI (β = 0.349, p < 0.001 and β = −0.235, p < 0.001, respectively) (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

This study produced two important findings. First, we found a positive correlation of the preoperative CAVI (or AS) with age and a negative correlation of the CAVI with BMI and BW. Second, there were no correlations between AS and factors previously reported to impact AS, such as sex [

15,

16,

17], hypertension [

15,

16,

17], diabetes mellitus [

15,

16], the triglyceride level [

17,

18], the cholesterol level [

16,

17], and smoking [

15,

19].

Shirai et al. [

23] reported that worsening of the CAVI with age occurs at a rate of 0.5 per decade in the Japanese general population according to the linear regression equation. If we calculate the CAVI using the same linear regression equation (5.43 + 0.053x age for men and CAVI = 5.34 + 0.049x age for women) in the general population, the equation performed separately for men and women in the present study would yield a CAVI of 9.5 for men because they were 76 years old and 8.9 for women because they were 73 years old. Thus, the median CAVI of 8.9 at the age of 74 years, including both men and women with end-stage osteoarthritis in this study, is comparable to that in the general population. Finally, the multivariate analysis showed that age was the strongest factor affecting AS in patients with osteoarthritis.

Another finding of this study is that BW and BMI were negatively correlated with CAVI, suggesting that some muscle mass and fat are necessary for maintenance of the CAVI or prevention of its deterioration. Two previous studies support our results. Park et al. [

25] stated that low muscle mass is independently and significantly associated with an increased CAVI and should be considered when assessing the risk of atherosclerosis in asymptomatic patients. Nagayama et al. [

16] speculated that systemic accumulation of adipose tissue may itself lead to a linear reduction in arterial stiffness in non-obese and obese patients without metabolic disorders. The significant correlation of the BMI with the CAVI in the present study also suggests that proper muscle mass and moderate adipose tissue may have a positive effect on AS. Thus, the present study may suggest that the patient characteristic that warrants caution regarding AS during and immediately after TKA is a lean body habitus (low BMI) in patients of advanced age.

In the present analysis, the CAVI was not correlated with factors other than age, BW, and BMI, as previously reported [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. This result does not mean that preoperative complications and comorbidities do not impact the CAVI, but the fact that all patients in this study had an ASA of I or II suggests that their clinical condition had little impact on the CAVI or that they were successfully treated. This is a reasonable assumption given that a preoperative ASA score of ≥3 has been reported to be an independent risk factor for serious adverse events after TKA [

26]. The finding that less than half of the patients (47%) had a preoperative CAVI of ≥9.0 and were judged abnormal [

23] seems to corroborate the conclusion that preoperative comorbidities were not severe in this study.

Finally, there was no correlation between the preoperative CAVI and the degree of osteoarthritis by the KL classification [

21] or HSS knee score [

22], suggesting that increased pain and decreased walking ability in association with the severity of osteoarthritis may not play a major role in the progression of the CAVI or AS. However, considering previous reports of higher all-cause mortality in patients with osteoarthritis than in the general population [

3] and reports that the severity of osteoarthritis-related disability is associated with significantly increased all-cause mortality and serious CVD events [

27] (also demonstrating the association between osteoarthritis and comorbidities, including AS), osteoarthritis may play a supporting role in amplifying AS-aggravating factors such as diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

This study had three limitations. First, this study was conducted at a single institution; thus, the distribution of the patients was skewed, with a disproportionate number of men and women and only mild comorbidity in patients with ASA classifications of I and II. Future studies should analyze patients with various backgrounds at multiple centers. Second, the analysis was limited to Japanese patients. Interestingly, several studies have suggested differences in the mean CAVI among countries [

28,

29,

30]. Therefore, multinational studies should be performed to verify the validity of our results. Third, the HSS clinical scores, including activity assessment [

22], were evaluated prior to TKA surgery, but specific measures of activity, such as the number of steps, were not evaluated. Specific step counts are generally confirmed using pedometers. Despite these limitations, the main strength of this study is that it is the first report of AS evaluation using the CAVI with a focus on patients with osteoarthritis. Furthermore, the results of this study not only clarify the patient population that is likely to require AS countermeasures intraoperatively and immediately postoperatively, but the results also make it possible to confirm the spillover effects of TKA on AS if CAVI trends after TKA surgery are observed over the mid to long term.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study suggest that the patient characteristics that warrant special attention to AS intraoperatively and immediately postoperatively are a lean body habitus (low BMI) and advanced age. It is also possible that because the study population comprised patients with ASA scores of I and II, there were no morbidities severe enough to affect AS. To more practically evaluate the impact of end-stage osteoarthritis on AS, future studies based on the accumulation of preoperative CAVI data in patients with osteoarthritis who have various backgrounds, including patients with an ASA score of ≥III, are essential.

Authors’ contributions

YI contributed to the study conception and design, drafted the article, and ensured the accuracy of the data and analysis. HN, JS, and IT contributed to the study conception and design and to the analysis and interpretation of the data. HI, RI, KeI and KaI contributed to the data collection. ST provided statistical expertise and contributed to ensuring the accuracy of the data and analysis. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Informed Consent Statement

All patients provided informed consent.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shohei Yoshizawa RN for his contributions in gathering the data, and Edanz Group (

www.edanzediting.com/ac), for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest statement

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g., consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Ethical Review Committee Statement

Approval for this study was obtained from the Research Board of Healthcare Corporation Ashinokai, Gyoda, Saitama, Japan (ID number: 2022-6). All patients provided informed consent.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the local institutional review board approved this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- King, L.K.; Kendzerska, T.; Waugh, E.J.; Hawker, G.A. Impact of osteoarthritis on difficulty walking: A population-based study. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken). 2018, 70, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kendzerska, T.; Jüni, P.; King, L.K.; Croxford, R.; Stanaitis, I.; Hawker, G.A. The longitudinal relationship between hand, hip and knee osteoarthritis and cardiovascular events: a population-based cohort study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2017, 25, 1771–1780. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nüesch, E.; Dieppe, P.; Reichenbach, S.; Williams, S.; Iff, S.; Jüni, P. All cause and disease specific mortality in patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis: population based cohort study. BMJ 2011, 342, d1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, T.; Ito, H. Arterial stiffness in health and disease: The role of cardio-ankle vascular index. J. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bierma-Zeinstra, SMA. ; Waarsing, J.H. The role of atherosclerosis in osteoarthritis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2017, 31, 613–633. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, S.M.; Dawson, C.; Wang, Y.; Tonkin, A.M.; Chou, L.; Wluka, A.E.; Cicuttini, F.M. Vascular pathology and osteoarthritis: A systematic review. J. Rheumatol. 2020, 47, 748–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macêdo, M.B.; Santos, V.M.O.S.; Pereira, R.M.R.; Fuller, R. Association between osteoarthritis and atherosclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp. Gerontol. 2022, 161, 111734. [Google Scholar]

- Shirai, K.; Utino, J.; Otsuka, K.; Takata, M. A novel blood pressure-independent arterial wall stiffness parameter; cardio-ankle vascular index (CAVI). J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2006, 13, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namba, T.; Masaki, N.; Takase, B.; Adachi, T. Arterial stiffness assessed by cardio-ankle vascular index. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3664. [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita, K.; Ding, N.; Kim, E.D.; Budoff, M.; Chirinos, J.A.; Fernhall, B.; Hamburg, N.M.; Kario, K.; Miyoshi, T.; Tanaka, H.; et al. Cardio-ankle vascular index and cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective and cross-sectional studies. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2019, 21, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, G.S.; Liow, M.H.; Bin Abd Razak, H.R.; Tay, D.K.; Lo, N.N.; Yeo, S.J. Patient-reported outcomes, quality of life, and satisfaction rates in young patients aged 50 years or younger after total knee arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2017, 32, 419–425. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.H.; Park, J.W.; Jang, Y.S. Long-term (Up to 27 Years) prospective, randomized study of mobile-bearing and fixed-bearing total knee arthroplasties in patients <60 years of age with osteoarthritis. J. Arthroplast. 2021, 36, 1330–1335. [Google Scholar]

- Kremers, H.M.; Sierra, R.J.; Schleck, C.D.; Berry, D.J.; Cabanela, M.E.; Hanssen, A.D.; Pagnano, M.W.; Trousdale, R.T.; Lewallen, D.G. Comparative survivorship of different tibial designs in primary total knee arthroplasty. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2014, 96, e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreozzi, V.; Conteduca, F.; Iorio, R.; Di Stasio, E.; Mazza, D.; Drogo, P.; Annibaldi, A.; Ferretti, A. Comorbidities rather than age affect medium-term outcome in octogenarian patients after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2020, 28, 3142–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, Y.A.; Al-Shahrani, F.S.; Alanazi, S.S.; Alshammari, F.A.; Alkhudair, A.M.; Jatoi, N.A. The Association of blood glucose levels and arterial stiffness (Cardio-ankle vascular index) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cureus. 2021, 13, e20408. [Google Scholar]

- Nagayama, D.; Imamura, H.; Sato, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Ban, N.; Kawana, H.; Nagumo, A.; Shirai, K.; Tatsuno, I.; et al. Inverse relationship of cardioankle vascular index with BMI in healthy Japanese subjects: a cross-sectional study. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2016, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovska, I.; Kunzova, S.; Jakubik, J.; Hruskova, J.; Skladana, M.; Rivas-Serna, I.M.; Medina-Inojosa, J.R.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Vysoky, R.; Geda, Y.E.; et al. Associations between high triglycerides and arterial stiffness in a population-based sample: Kardiovize Brno 2030 study. Lipids Health Dis. 2020, 19, 170. [Google Scholar]

- Dobsak, P.; Soska, V.; Sochor, O.; Jarkovsky, J.; Novakova, M.; Homolka, M.; Soucek, M.; Palanova, P.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Shirai, K. Increased cardio-ankle vascular index in hyper-lipidemic patients without diabetes or hypertension. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2015, 22, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubozono, T.; Miyata, M.; Ueyama, K.; Hamasaki, S.; Kusano, K.; Kubozono, O.; Tei, C. Acute and chronic effects of smoking on arterial stiffness. Circ. J. 2011, 75, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. American Society of Anaesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System. Available online: http://www.asahq. org/resources/clinical-information/asa-physical-statusclassification-system (accessed on 24 March 2023).

- Kellgren, J.H; Lawrence, J.S. Radiographical assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1957, 16, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicea, J. Scoring systems and their validation for the arthritic knee. In Surgery of the Knee, 3rd ed.; Insall, J.N., Scott, W.N., Eds.; Churchill Livingstone: New York, NY, USA, 2001; Volume 2, pp. 1507–1515. [Google Scholar]

- Shirai, K.; Hiruta, N.; Song, M.; Kurosu, T.; Suzuki, J.; Tomaru, T.; Miyashita, Y.; Saiki, A.; Takahashi, M.; Suzuki, K.; et al. Cardioankle vascular index (CAVI) as a novel indicator of arterial stiffness: theory, evidence and perspectives. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2011, 18, 924–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A.; Tomiyama, H.; Maruhashi, T.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Miyoshi, T.; Kabutoya, T.; Kario, K.; Sugiyama, S. ; Munakata M, Ito, H. ; et al. Physiological diagnostic criteria for vascular failure. Hypertension 2018, 72, 1060–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.E.; Chung, G.E.; Lee, H.; Kim, M.J.; Choi, S.Y.; Lee, W.; Yoon, J.W. Significance of Low Muscle mass on arterial stiffness as measured by cardio-ankle vascular index. Front Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 857871. [Google Scholar]

- Bovonratwet, P.; Fu, MC.; Tyagi, V.; Gu, A.; Sculco, P.K.; Grauer, J.N. Is discharge within a day total knee arthroplasty safe in the octogenarian population? J. Arthroplast. 2019, 34, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawker, G.A.; Croxford, R.; Bierman, A.S.; Harvey, P.J.; Ravi, B.; Stanaitis, I.; Lipscombe, L.L. All-cause mortality and serious cardiovascular events in people with hip and knee osteoarthritis: a population based cohort study. PLoS. One 2014, 9, e91286. [Google Scholar]

- Uurtuya, S.; Taniguchi, N.; Kotani, K.; Yamada, T.; Kawano, M.; Khurelbaatar, N.; Itoh, K.; Lkhagvasuren, T. Comparative study of the cardio-ankle vascular index and ankle–brachial index between young Japanese and Mongolian subjects. Hypertens. Res. 2009, 32, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yingchoncharoen, T.; Sritara, P. Cardio-ankle vascular index in a Thai population. Pulse 2017, 4 (Suppl. 1), 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shirai, K.; Liu, J.; Lu, N.; Wang, M.; Zhao, H.; Xie, J.; Yu, X.; Fu, X.; Shi, H.; et al. Comparative study of cardio-ankle vascular index between Chinese and Japanese healthy subjects. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2014, 36, 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).