What is known about this topic: Population screening for carrier state of sickle hemoglobin followed by genetic counselling is the most sustainable method for long term control of sickle cell disease.

What this paper adds to the topic: Current study proposes the population screening protocols for various life stages using currently available screening methods best suited for a resource limited setting.

1. Introduction

Hemoglobin S (Hb S) is genetically inherited, autosomal recessive variant of hemoglobin, characterized by sickle-shaped red blood cells. It is estimated that 300 000 infants are born annually across the globe with sickle variant of hemoglobin.[

1] Most of the individuals affected with Hb S live in Sub-Saharan Africa, India, the Mediterranean, and Middle East. The numbers are expected to rise exponentially if no preventive measures are placed among the population. A projection estimated that following current trends by 2050, every year approximately 4 million babies will join the global pool of Hb S affected population. [

2]

In many resources limited settings, the burden of sickle cell disease (SCD) is exacerbated by limited access to health care infrastructure, poor nutrition and high prevalence of infectious diseases like malaria, tuberculosis and HIV.[

3,

4] In these regions, nearly 80% of the babies born with SCD remain undiagnosed and less than half of them survive beyond 5 years of age. [

1] In presence of comprehensive healthcare management and universal new born screening practices more than 90% of the babies born with SCD are able to survive till adulthood. But such facilitates are available only in developed countries having only less than 1% of global share of SCD. [

1,

3] Ironically, these interventions associated with reduced morbidity and mortality of SCD along with improved life expectancy are largely inaccessible to the worst hit patients in low-income countries. [

1,

3,

4]

2. Public Health Goal of Screening for SCD –

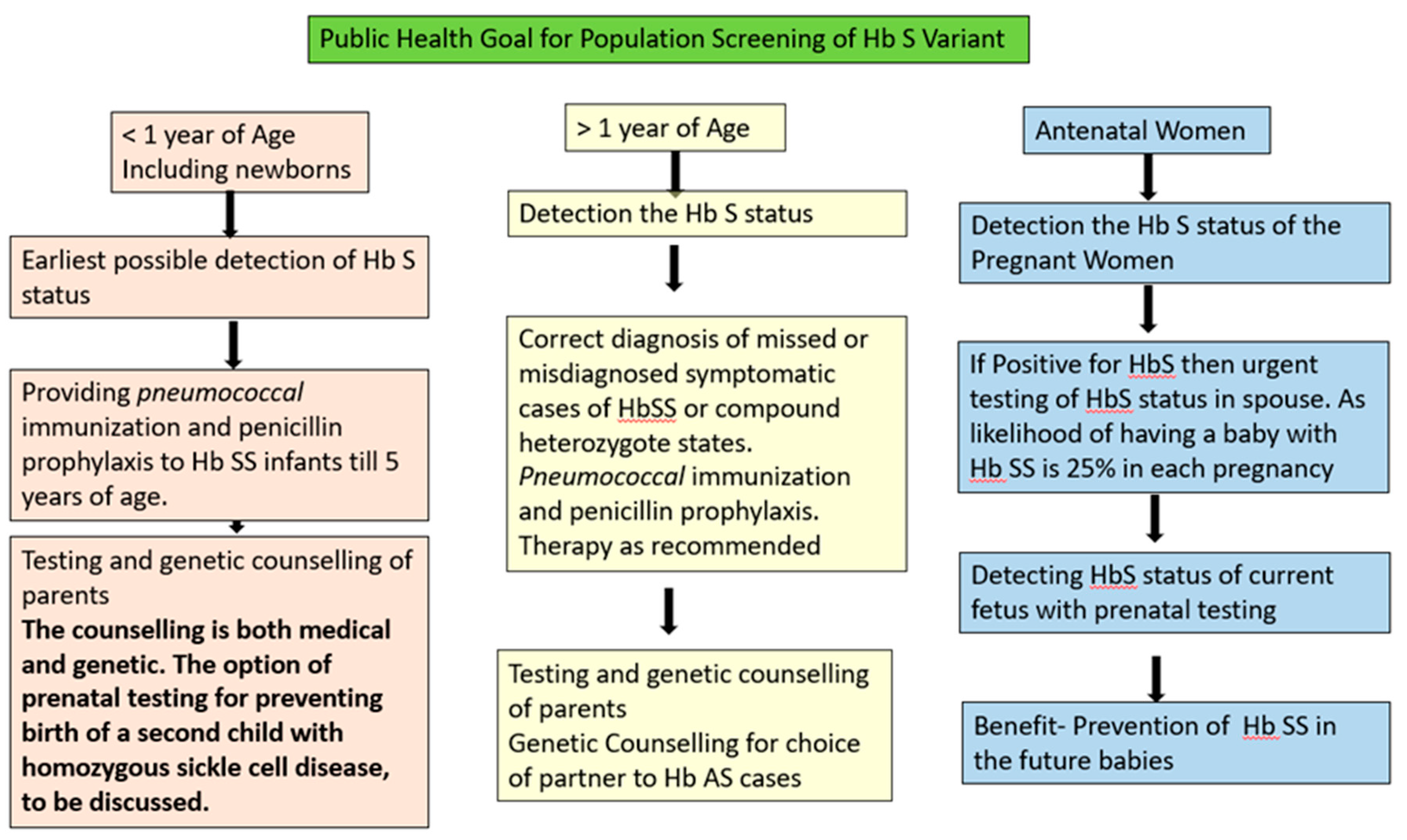

Population screening along with awareness generation regarding the genetic inheritance of Hb S is the recommended strategy for prevention of SCD at national level. The goals and methods of diagnosis for SCD vary with the target population. In general, there are three testing periods for Hb S Screening along the life course: newborn/infant, post-infancy till pre conceptional period and antenatal women.

Figure 1 shows the public health goals for screening of Hb S at various testing periods across the life course.

3. Available Technology and Their Challenges for Population Screening of Sickle Cell Disease

It is reported that new born screening practice paired with implementation of penicillin prophylaxis, pneumococcal vaccination and parental education significantly reduces overall morbidity and mortality. [

6,

7,

8,

9] Most commonly used technique for population screening of Hb S in low resource setting is solubility test, as it is low cost and easy to administer as well as interpret. However, the test suffers from low sensitivity thus giving high number of false positive and false negative results. Also, it does not differentiate between Hb S trait and disease.[

10,

11]

Another common test for identifying Hb S is sickling test using sodium metabisulfite to induce polymerization of sickle hemoglobin by reducing oxygen tension of sample and then identifying the consequent sickling of RBCs under a microscope. Even though it does not differentiate between sickle trait and disease, sickling remains widely used in resource-limited settings due to its low cost and very high specificity for detecting Hb S. [

12]

Confirmatory tests used for identifying Hb S are routine basic methods of protein chemistry that enable separation of Hb variants according to their protein structure or charge, including Hb electrophoresis, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), isoelectric focusing (IEF) or hemoglobin capillary zone electrophoresis (HbCZE). These methods are limited by the need for equipment and expertise to conduct as well as interpret the report, which add complexity and cost. Although these tests have high diagnostic accuracy for detecting Hb S, they also have their technical limitations. The response of two hemoglobin variants may be similar enough to prevent differentiation under the testing conditions of a given technology. For example, hemoglobin S co-migrates with other variant hemoglobins D, G, and Lepore on alkaline hemoglobin electrophoresis; hemoglobin E co-elutes with hemoglobin A2 on HPLC. Therefore, even though hemoglobin electrophoresis, IEF, and HPLC are highly sensitive for the diagnosis of Hb S, confirmation is still required with another methodology. Sickling test is used most frequently to confirm the presence of hemoglobin S. [

10,

13]

The employment of a low-cost, rapid, and accurate POC screening tools will bridge the gap in diagnosis. The most recent technological advancements for SCD screening focused towards overcoming concerns of cost, portability, as well as ease in conduct and interpretation of the test. We have identified two most promising technologies according to their operating principles, ease of conduct and interpretation for our Hb S screening protocol. (i) lateral flow immunoassays (ii) micro engineered electrophoresis.

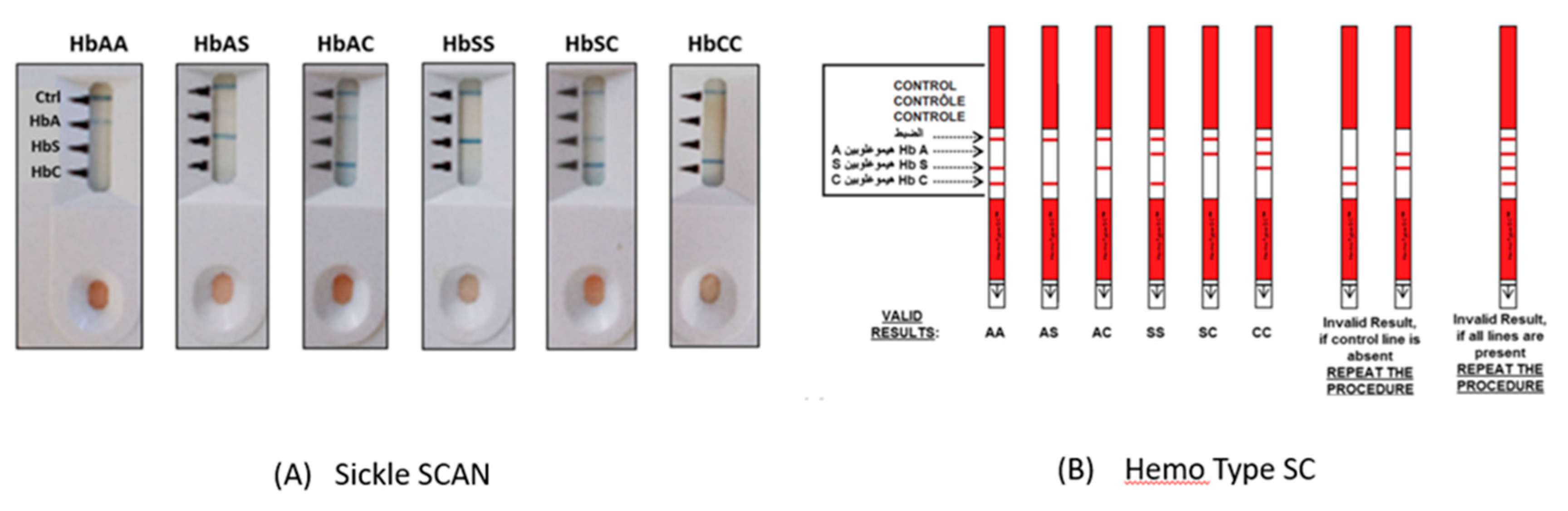

Lateral Flow Immunoassays - Lateral flow immunoassays are portable, low-cost, rapid, ready to use diagnostic tests which can be successfully applied in low resource settings. No special instruments or training is required for the conduct of these tests and results are available within minutes. These tests are ideal for POC diagnoses in areas without access to a specialized clinical laboratory. Two kits using lateral flow immunoassays are available (i) SickleSCAN (ii) HemoTypeSC

SickleSCAN - The test qualitatively detects hemoglobin S, hemoglobin C, and hemoglobin A using polyclonal antibodies on lateral flow chromatographic immunoassay. The hemoglobin variant binds with the corresponding antibody and produces lines for visual detection. The Sickle SCAN cartridge contains four detection bands: the control band, normal HbA, HbS band, and HbC band.[

14] The turnaround time for each test is about 10-15mins and the kits have been reported to be stable under storage conditions of 37

◦C for 30 days. The test’s accumulative sensitivity and specificity for Hb SS were reported to be 98.4% and 98.6%, respectively. A neonate sample with a high amount of Hb F was tested and demonstrated that the detection of Hb S or Hb C was not affected by the high concentration of Hb F. [

15,

16]

Thus, the test provides a qualitative read-out only, indicating the presence but not the quantity of HbA, HbS, or HbC. Although, Sickle SCAN assay requires a very small amount of blood collected by finger prick, but the user must perform an extra step diluting the blood in the supplied buffer solution before adding it to the device. [

17]

HemoTypeSC™ - —The HemoTypeSC™ assay incorporates monoclonal antibodies with greater specificity (< 0.1% cross reactivity with non-target hemoglobins) for Hb A, S, and C and ability to resolve and distinguish normal from common carrier and homozygous genotypes. Turnaround time for each test is about 15 minutes, after which the test strip is visually inspected for the presence or absence of a red-colored band at each of four test lines (Hb C, Hb S, Hb A and control). Presence of a Hb variant in the sample is indicated by the absence of a red band at the test line.

Figure 2 presents the possible results and interpretations of lateral flow immunoassay Sickle SCAN and Hemotype SC. The validation study conducted to access the diagnostic accuracy of Hemo Type SC reported that correct hemoglobin phenotype was identified in 100% of samples. Test accuracy was not affected by the amount of Hb F (0–94·8% of total Hb) or Hb A2 (0–5·6% of total Hb). [

18]

The assay neither requires a separate dilution step or any other equipment for the conduct of the test for detection of antigens nor does it require refrigeration for storage. A potential limitation when used in the field is the non-intuitive interpretation of the test results wherein the absence of a band indicates the presence of a hemoglobin. There is concern that widespread use of these devices in the hands of users that are not properly trained may result in significant problems in test interpretation, possibly identifying many as having sickle cell disease or missing those that are truly HbSS. [

17]

4. Micro-Engineered Electrophoresis/Gazelle

It is a portable microchip electrophoresis assay for detection and quantification of normal and variant hemoglobins. The assay is a miniaturized version of cellulose acetate electrophoresis, comprised of a micro-engineered plastic chip within a battery-powered electric field that separates various hemoglobin types based on charge. [

18] The pilot study for validation against standard electrophoresis and HPLC reported 89% sensitivity and 86% specificity for identification of Hb A, Hb S, Hb C/A2, and Hb F. However, latest studies have reported higher diagnostic accuracy (<95%).[

19,

20]

The Gazelle device yields results in less than 15 minutes and the hemoglobin fractions displayed on the device can are quantified. The report generated is easily interpretable and can also be printed or shared via email for documentation. As with standard cellulose acetate electrophoresis, the potential limitation of the assay is the inability to distinguish co-migrating hemoglobins, such as Hb C and A2. There is limited evidence regarding its use among newborns, elevated levels of Hb F may mask the presence of very small amounts of other hemoglobins, such as Hb S and A. [

17]

5. Recommendation Screening Strategy

The screening tests for SCD have their respective limitations and the confirmatory tests are cost intensive as well as expertise intensive for their conduct and interpretation. Also, there are reports of pitfalls in the use of HPLC for diagnosing Hb S. Therefore, it is recommended to use two tests for the diagnosis Hb S. Hence in our recommendations for the screening protocol we have included the use of two screening tests. The use of two tests will enhance the overall diagnostic accuracy at the level of screening and limited number of people will be required to be taken for further testing and management.

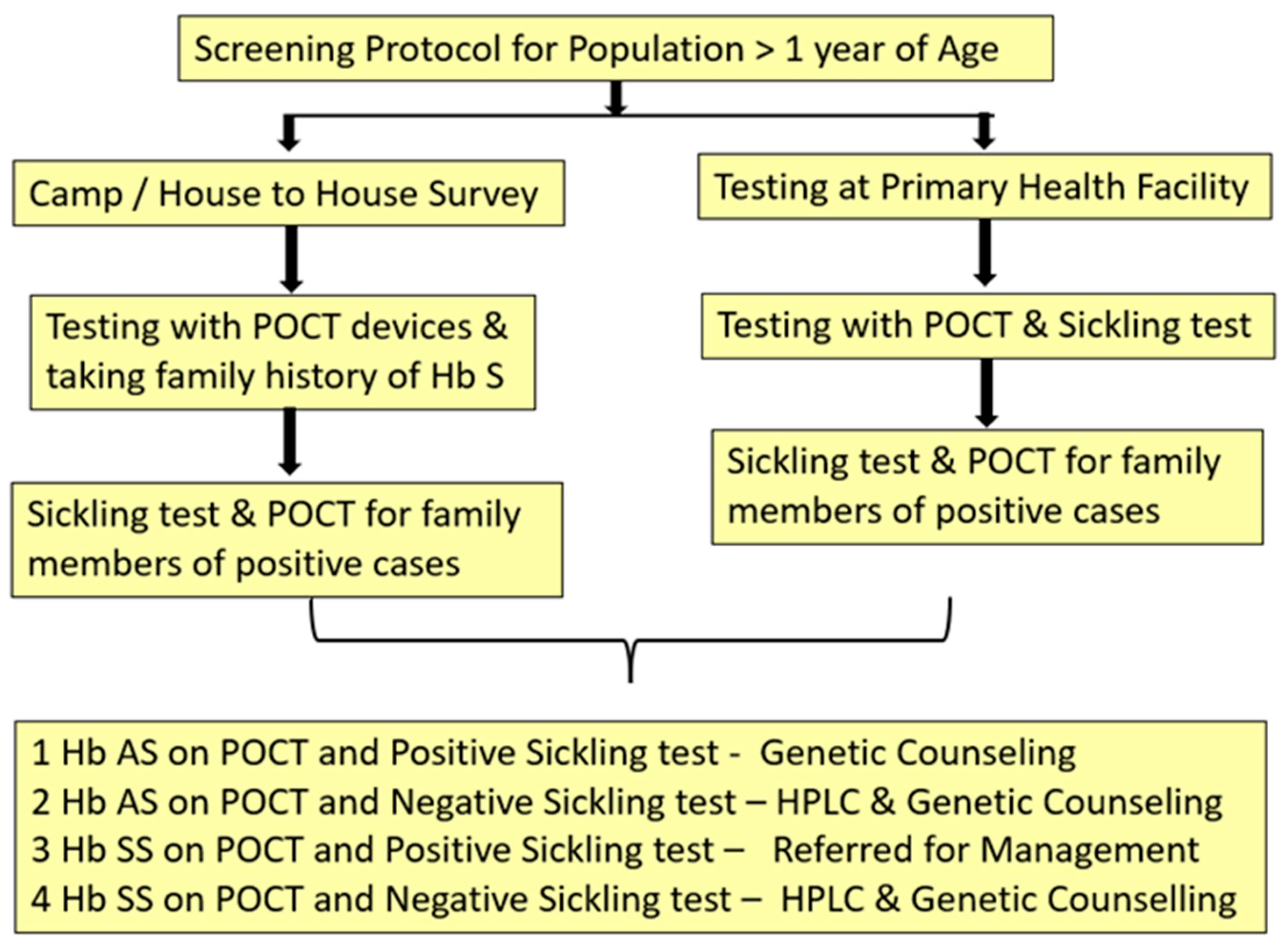

6. Screening Protocol for >1 Year of Age

Most of the patients with compound heterozygote states of Hb S as well as SCD requiring medical management become symptomatic by one year of age and even require blood transfusions, hence, are included in the health care system. However, the knowledge of Hb S status of asymptomatic population is imperative for prevention purpose.

Figure 3 presents the recommended protocol for asymptomatic population > 1 year of age for screening of Hb S.

It is known from epidemiology that when two screening tests are used simultaneously together on a target population their effecting sensitivity is enhanced and when used sequentially one after the other their specificity increases. [

21]

At community level we recommend the use of any of the lateral flow immunoassay devices as they have shown high diagnostic accuracy for identifying sickle cell disease as well as trait. They are easy to operate and give results within minutes. Sickling test is recommended to all those positive for POCT device and both the tests are recommended for all the family members of individuals testing positive with POCT at first instance. Whereas, in facility-based testing either lateral flow immunoassay devices or micro engineered electrophoresis can be used .The conduct of micro electrophoresis requires some training for processing of the sample and also blood sample is to be taken for sickling test along with POCT test for screening.

The protocol enables us to identify the sickle status of an individual i.e. trait or disease as well get a confirmation of the same by sickling test. High end test for quantification of Hb S would be required only for Hb S homozygous cases before initiation of medical management.

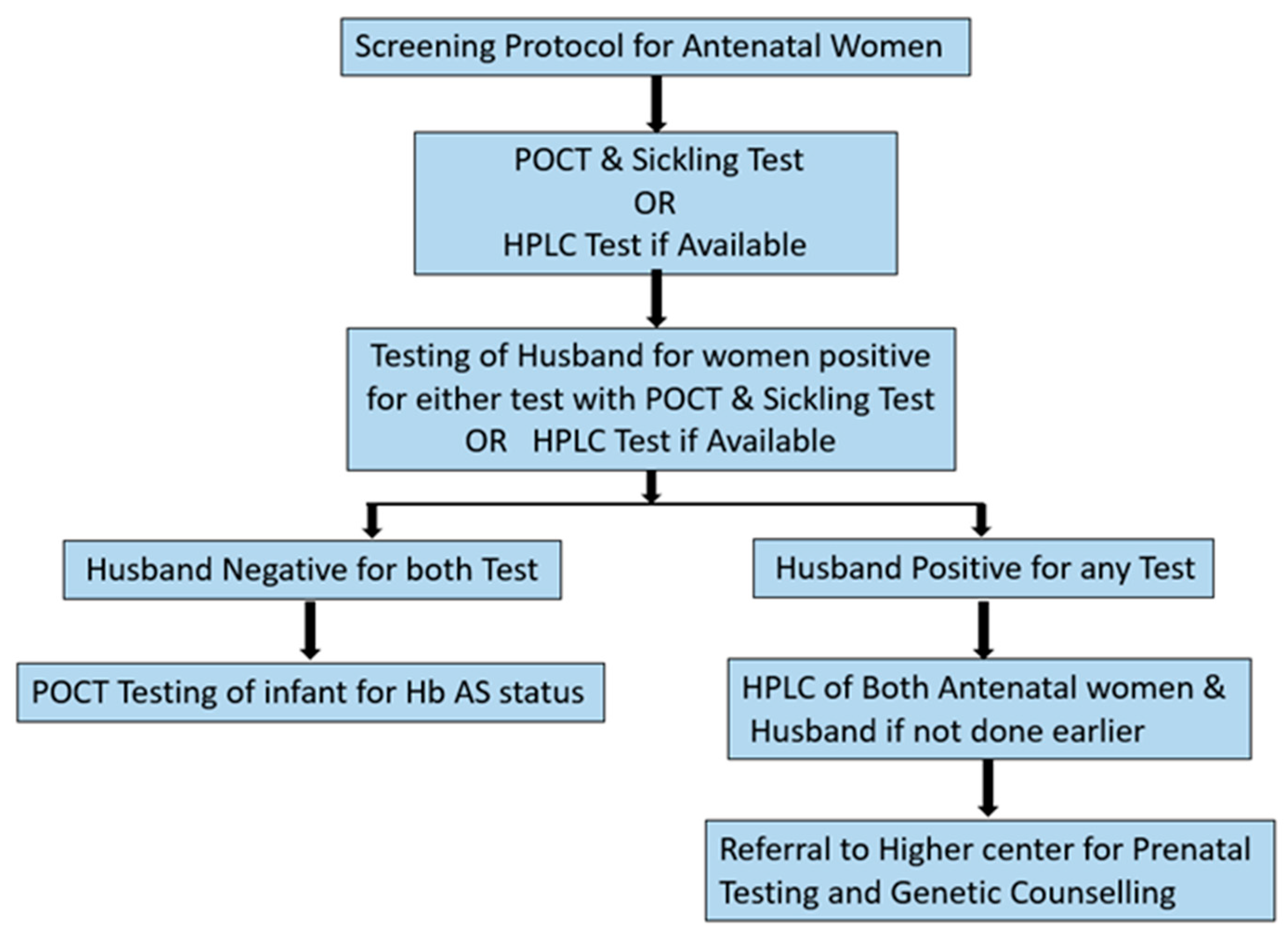

7. Ante Natal Screening for Sickle Cell Disease

Antenatal period is a window when we have an opportunity to detect and prevent the birth of a child with sickle cell as well as other hemoglobinopathy.

Figure 4 presents the protocol for asymptomatic antenatal women for screening of Hb S.

If available then HPLC is recommended at initial stage of pregnancy for all antenatal women to identify any existing hemoglobinopathy. Husbands of the women found positive for any hemoglobinopathy on HPLC to be taken up for testing. Prenatal testing is recommended at tertiary health care centers under expert supervision for positive couples along with genetic counselling.

In case of unavailability of HPLC, POCT along with sickling test are recommended initially for assessment of Hb S status. We recommend the use of micro electrophoresis for screening ante natal women at facility level, in case of non availability of HPLC. Micro electrophoresis co elutes Hb S an Hb D Punjab in the same window, this inherent draw back may be used to our advantage as the device will flag all the cases of Hb S as well as Hb D even at the cost of misdiagnosing them. The micro electrophoresis device is also able to detect Hb A2 as well as Hb E however, diagnostic accuracy for detection of theses variants is yet to be established by validation studies. We would be able to pick a wider spectrum of hemoglobinopathies among antenatal women flagged as positive even if the definitive diagnosis of phenotype requires confirmation. The spouses of all women tested positive for either POCT or sickling test should be taken up for testing urgently, followed by genetic counselling. Any antenatal women giving family history of hemoglobinopathy/ requirement of repeated blood transfusion or symptoms of hemoglobinopathy may be assessed clinically and investigated accordingly.

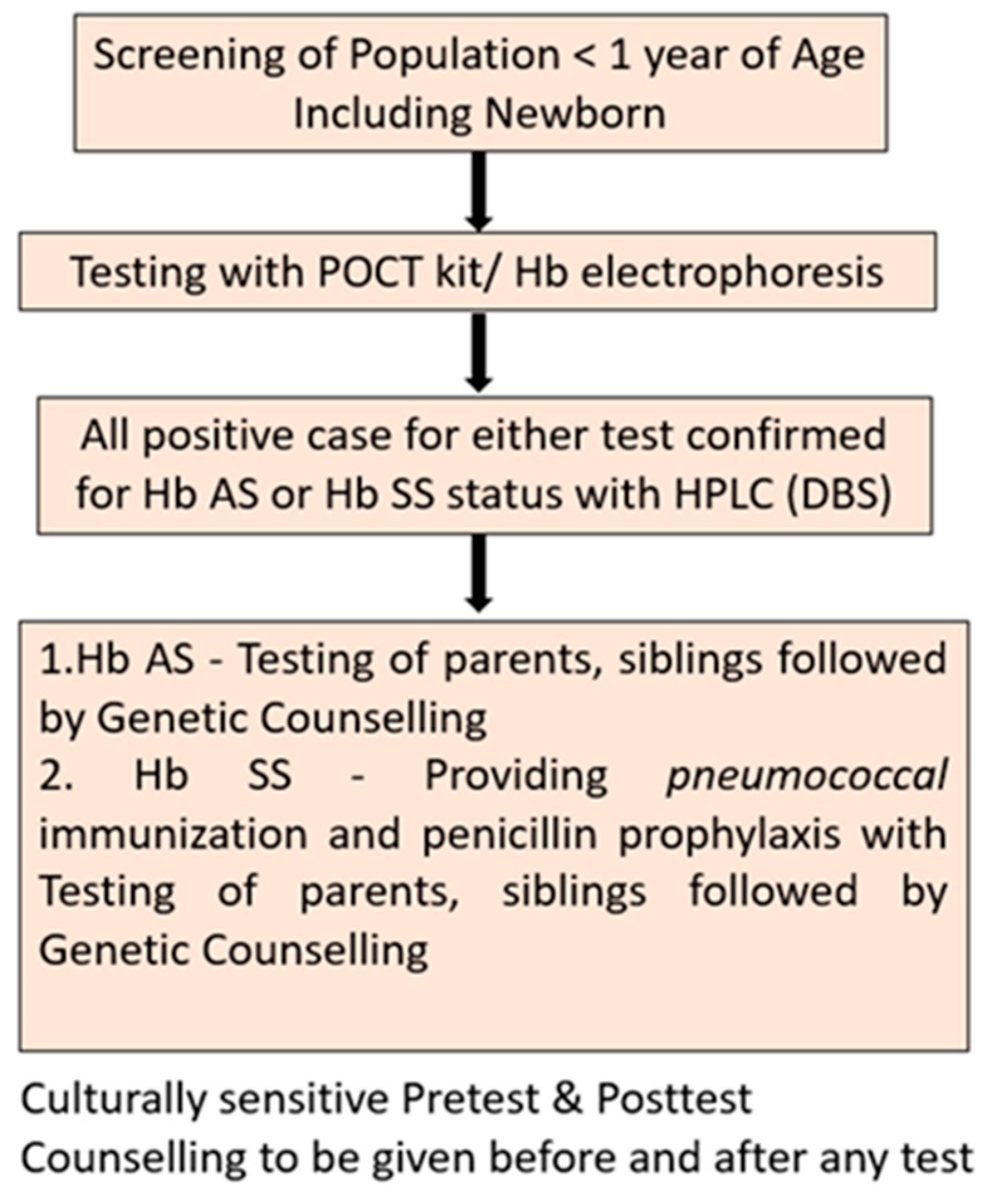

8. New Born Testing

High levels of Hb F at neonatal stage are known to interfere with identification of hemoglobin fractions in most of the diagnostics. However, early identification of Hb S and institution of penicillin prophylaxis and immunization reduces the mortality and increases life expectancy substantially.

Figure 5 presents the protocol recommended for screening of newborns and neonates for Hb S

. Lateral flow immunoassay devices have reported good diagnostic accuracy for newborn testing for Hb S, however, other POCT have not published any validation study among newborns. Sickling test though can be performed in newborns, needs special precautions. [

22] We have not recommended the same due to inadequate supportive evidence for use of sickling test for screening newborns.

9. Estimated Diagnostic Accuracy Achieved by the Suggested Protocol-

We have recommended sequential use of POCT and sickling test for screening at mass level. The reported sensitivity and specificity of both the lateral flow immunoassay devices are more than 95%. [

19,

20,

23]. Sickling test has reported 97% sensitivity and 99.9% specificity for identification of Hb S [

23]. Hence is used for verification of presence of Hb S for all cases testing positive on other tests.

Since the above mentioned studies were supervised by researchers, we may expect a slight drop in diagnostic accuracy when the same tests are rolled out at field and performed by grass root level health care workers. At the level of screening test sensitivity is prioritized as it defines the proportion of correctly identifies diseased cases as positive by the test. High sensitivity of a test also reduces the number of false negatives i.e. those who are disease but not picked up by the testing protocol. Assuming that the POCT devices and the sickling test are able to achieve a sensitivity of only 90% of sensitivity in field conditions. Even then, if we apply a protocol of simultaneous testing with both test after epidemiological calculations, we achieve a net sensitivity of 99% for a population. This is comparable to diagnostic accuracy of a gold stand being applied at population level.

Further the suggested protocol does not require highly trained health care workers for the conduct and interpretation of the tests. The POCT’s can be conducted by grassroot level health workers and sickling test requires only a microscope and laboratory technician with basic level of training. In some select case requiring family studies to arrive at a definitive diagnosis, POCT devices would gather better compliance due to portability and fast results.

10. Cost Effectiveness Implications by the Suggested Protocol-

For the purpose of prevention, it is imperative not just to know the presence of Hb S in a population but also to classify them as trait and disease. Targeted screening for sickle cell has been found to be more cost effective than no screening at all in place. However, as compared to targeted screening universal screening always identifies more infants with disease, prevents more deaths, and is cost-effective. [

24] Universal new born screening has also been found to be cost effective in terms of incremental cost per life year gained. [

25]

A recent review reported the sickling as well as POCT testing methods to be low cost (less than 1

$) as compared to the confirmatory tests. [

26] The suggested protocol minimises the use of cost intensive confirmatory tests as well as the dependency on highly trained manpower required for these tests.

It may be argued that the recommended protocols only emphasize on Hb S and may miss compound heterozygous states of Hb S and diagnose them as Hb S trait. We would like to reiterate that the recommended protocols are only for asymptomatic target population. The workup of a symptomatic patient may be taken up as per clinical discretion.

References

- Aygun B, Odame I. A global perspective on sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59(386):390. [CrossRef]

- Thein MS, Swee L. World Sickle Cell Day 2016: a time for appraisal. Indian J Med Res. 2016;143(6):678-681.

- Ware RE. Is sickle cell anemia a neglected tropical disease? Plos Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(5):e2120.

- Piel FB, Hay SI, Gupta S, et al. Global burden of sickle cell anaemia in children under five, 2010-2050: modelling based on demographics, excess mortality, and interventions. Plos Med. 2013;10:e1001484. [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, C. C. Prenatal and newborn screening for hemoglobinopathies. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 35, 297–305 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Ansong D, Akoto AO, Ocloo D, Ohene-Frempong K. Sickle cell disease: management options and challenges in developing countries. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2013; 5(1):e2013062. [CrossRef]

- Cober MP, Phelps SJ. Penicillin prophylaxis in children with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2010; 15(3):152–159. [CrossRef]

- McGann PT, Nero AC, Ware RE. Current management of sickle cell anemia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013; 3(8). [CrossRef]

- Mulumba LL, Wilson L. Sickle cell disease among children in Africa: An integrative literature review and global recommendations. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015; 3:56–64. [CrossRef]

- Tubman VN, Field JJ. Sickle solubility test to screen for sickle cell trait: what's the harm?. Hematol. 2015 Dec 5;2015(1):433-5.

- Hicks EJ, Griep JA, Nordschow CD. Comparison of results for three methods of hemoglobin S identification, Clin Chem, 1973, vol. 60 3(pg. 430-432). [CrossRef]

- Schneider RG, Alperin JB, Lehmann H. Sickling test: pitfalls in performance and interpretation, JAMA, 1967, vol. 202 5(pg. 419-421).

- Frömmel C. Newborn screening for sickle cell disease and other hemoglobinopathies: a short review on classical laboratory Methods—Isoelectric focusing, HPLC, and capillary electrophoresis. Int J Neo Scr. 2018 Dec 5;4(4):39. [CrossRef]

- Kanter, J.; Telen, M.J.; Hoppe, C.; Roberts, C.L.; Kim, J.S.; Yang, X. Validation of a novel point of care testing device for sickle cell disease. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 225. [CrossRef]

- Mcgann, P.T.; Schaefer, B.A.; Paniagua, M.; Howard, T.A.; Ware, R.E. Characteristics of a rapid, point-of-care lateral flow immunoassay for the diagnosis of sickle cell disease. Am. J. Hematol. 2016, 91, 205–210.

- Berg AO. Sickle cell disease: screening, diagnosis, management, and counselling in newborns and infants. The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1994; 7(2): 134–140.

- McGann PT, Hoppe C. The pressing need for point-of-care diagnostics for sickle cell disease: A review of current and future technologies. Blood . 2017 Sep 1;67:104-13. [CrossRef]

- Quinn, C.T.; Paniagua, M.C.; DiNello, R.K.; Panchal, A.; Geisberg, M. A rapid, inexpensive and disposable point-of-care blood test for sickle cell disease using novel, highly specific monoclonal antibodies. Br. J. Haematol. 2016, 175, 724–732.

- Hasan, M.N.; Fraiwan, A.; An, R.; Alapan, Y.; Ung, R.; Akkus, A.;et al. Paper-based microchip electrophoresis for point-of-care hemoglobin testing. Analyst 2020, 145, 2525–2542.

- Shrivas S, Patel M, Kumar R, Gwal A, Uikey R, Tiwari SK, Verma AK, Thota P, Das A, Bharti PK, Shanmugam R. Evaluation of microchip-based point-of-care device “Gazelle” for diagnosis of sickle cell disease in India. Frontiers in Medicine. 2021 Oct 13;8:639208. [CrossRef]

- Gordis L. Epidemiology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013 Nov 14.

- Schneider RG, Alperin JB, Lehmann H. Sickling tests: Pitfalls in performance and interpretation. JAMA. 1967 Oct 30;202(5):419-21.

- Hicks EJ, Griep JA, Nordschow CD. Comparison of results for three methods of hemoglobin S identification. Clin Chem. 1973 May 1;19(5):533-5. [CrossRef]

- Panepinto JA, Magid D, Rewers MJ, Lane PA. Universal versus targeted screening of infants for sickle cell disease: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Pediatr. 2000 Feb 1;136(2):201-8. [CrossRef]

- Castilla-Rodríguez I, Cela E, Vallejo-Torres L, Valcárcel-Nazco C, Dulín E, Espada M, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of newborn screening for sickle-cell disease in Spain. Exp Clin Immunogenet. 2016 Jun 2;4(6):567-75. [CrossRef]

- Alapan Y, Fraiwan A, Kucukal E, Hasan MN, Ung R, Kim M, et al. Emerging point-of-care technologies for sickle cell disease screening and monitoring. Expert review of medical devices. 2016 Dec 1;13(12):1073-93. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).